Introduction

Distant metastases upon presentation of small cell

lung cancer (SCLC) is a frequent clinical problem. Clinically,

treatment for extensive disease (ED)-SCLC consists of systemic

chemotherapy and radiotherapy for symptomatic metastatic sites. It

is generally accepted that the life expectancy of SCLC patients

depends on the extent of disease and the response to chemotherapy.

Performance status (PS), gender, disease extent and response to

chemotherapy have been evaluated as prognostic factors (1). Foster et al revealed that the

number of metastatic sites was also a prognostic factor in ED-SCLC

patients, regardless of the location of the metastatic site

(2). The four most common sites of

metastasis in SCLC at the time of diagnosis appear to be the liver,

bone, brain and lung, with involvement of these sites identified in

SCLC patients with newly diagnosed metastatic disease. Using the

database of SCLC patients, we examined whether specific organ

metastasis at the time of presentation had prognostic significance

in SCLC patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed 251 patients who were

diagnosed with SCLC in our divisions at the University of Tsukuba

and the Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital between January 1999 and

May 2010. This retrospective study conformed to the Ethical

Guidelines for Clinical Studies issued by the Ministry of Health,

Labor and Welfare of Japan. Analysis of the medical records of the

lung cancer patients was approved by the ethics committee of the

University of Tsukuba Hospital, Ibaraki, Japan. The diagnosis of

SCLC was confirmed in all patients using pathological and/or

cytological specimens. Pathological diagnosis of SCLC was defined

by the WHO classification (3).

Prior to treatments, a staging procedure was conducted for all

patients using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) of the head, bone scintigraphy and ultrasonography

and/or CT of the abdomen. Patients were staged according to the

staging system of the Veterans Administration Lung Cancer Study

Group into one of two categories; limited-stage disease (LD) or

extensive-stage disease (ED) (4,5).

Patients with LD-SCLC had metastatic disease restricted to the

ipsilateral hemithorax within a single radiation port, while

patients with ED-SCLC had widespread metastatic disease (4,5).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance between the two groups

was determined using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Chi-square

test. Logistic regression analysis was applied in order to examine

the significance of the seven variables, including liver, bone,

brain, lung, extrathoracic lymph node and adrenal metastasis as

well as pleural and/or pericardial fluid, for poor PS and

unfavorable response to chemotherapy. The Kaplan-Meier method was

used to assess the survival curves and the log-rank test was used

to evaluate the statistically significant differences between the

two groups. The length of survival was defined in months as the

interval from the date of initial therapy or supportive care until

the date of mortality or last follow-up. Cox’s proportional hazards

model was used to study the effects of clinicopathological factors

on survival (6). All statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS version 10.1 for Windows (SPSS,

Chicago, IL, USA) and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

The diagnosis of all 251 SCLC patients was

pathologically and/or cytologically confirmed. The characteristics

of these patients are shown in Table

I. Among the 251 SCLC patients, 222 (88.4%) were male and 29

were female. The mean age was 71 years (range, 41–86 years). A

total of 73 (29.1%) patients had pleural and/or pericardial fluids

and among the 152 (60.6%) patients that had distant metastasis, 51

(20.3%), 46 (18.3%), 39 (15.5%), 25 (10.0%) and 15 (6.0%) patients

also had liver, bone, brain, lung and adrenal gland metastasis,

respectively.

| Table I.Characteristics of 251 patients with

SCLC. |

Table I.

Characteristics of 251 patients with

SCLC.

| Patient

characteristics | No. of patients

(%) |

|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 71 |

| Range | 41–86 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 222 (88.4) |

| Female | 29 (11.6) |

| Distant

metastasis | |

| Present | 152 (60.6) |

| Absent | 99 (39.4) |

| Clinical stage | |

| Limited | 78 |

| Extensive | 125 |

| Metastatic

site | |

| Pleural and/or

pericardial fluids | 73 (29.1) |

| Liver | 51 (20.3) |

| Bone | 46 (18.3) |

| Brain | 39 (15.5) |

| Lung | 25 (10.0) |

| Adrenal

gland | 15 (6.0) |

| Extrathoracic

lymph node | 15 (6.0) |

| Pancreas | 3 (1.2) |

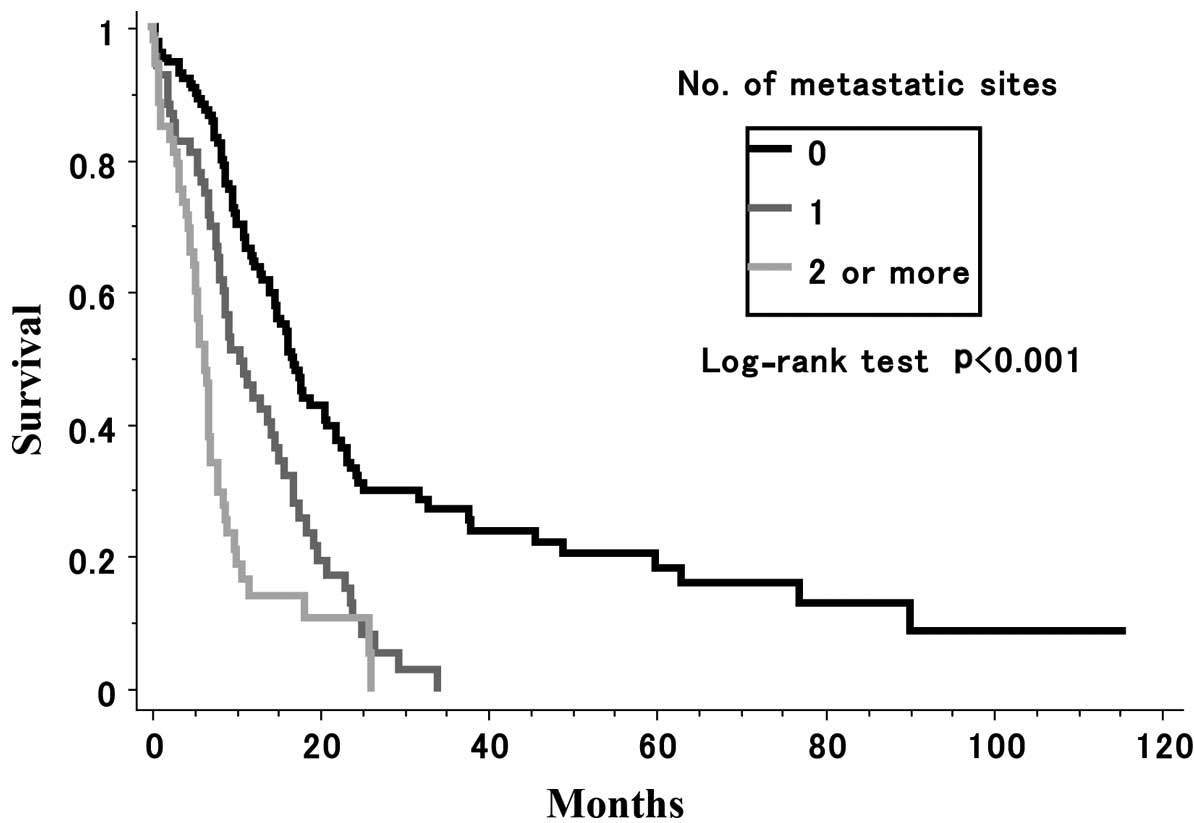

Number of metastatic sites infuences

survival rate

A total of 69 patients had one metastatic site, 28

had two, 20 had three, four had four and one had five (data not

shown). A statistically significant difference was observed in the

survival rate among patients without metastasis, those with one

metastatic site and those with two or more metastatic sites

(P=0.0001) (Fig. 1).

A total of 16 patients had sole liver metastasis,

while 35 patients had liver metastasis accompanied by metastasis in

another site. Additionally, 12, 22, and six patients had sole bone,

brain, and lung metastasis, respectively. A total of 34, 17 and 19

patients had bone, brain and lung metastasis accompanied by

metastasis in another site, respectively. A statistically

significant difference was observed in the one-year survival

between the patients with sole liver metastasis and those without

metastasis (P=0.0009). Similar results were observed between those

with sole bone (P=0.0013), brain (P=0.0163) and lung (P=0.169)

metastasis, and those without metastasis, respectively (Table II).

| Table II.Metastatic sites and comparison of

the one-year survival between patients with sole specific organ

metastasis and patients without metastasis. |

Table II.

Metastatic sites and comparison of

the one-year survival between patients with sole specific organ

metastasis and patients without metastasis.

| Metastatic

site | One-year survival

(%) | No. of patients

with sole metastatic sites | P-value |

|---|

| None | 54.3 | | |

| Liver | 18.8 | 16 | 0.0009 |

| Bone | 25.0 | 12 | 0.0013 |

| Brain | 40.9 | 22 | 0.0163 |

| Lung | 33.4 | 6 | 0.0169 |

Metastasis affects response to

chemotherapy

According to logistic regression analysis, liver

metastasis, brain metastasis and pleural and/or pericardial fluid

are correlated with a poor PS of 2–3 (Table III). A logistic regression analysis

also demonstrated that liver and brain metastasis are risk factors

of unfavorable response to chemotherapy (stable disease and

progressive disease; Table IV).

| Table III.Logistic regression analysis for the

factors of a poor PS (PS 2–3). |

Table III.

Logistic regression analysis for the

factors of a poor PS (PS 2–3).

| Independent

factor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Liver | 2.311 | 1.107–4.823 | 0.0256 |

| Bone | 1.505 | 0.683–3.313 | 0.3103 |

| Brain | 2.634 | 1.244–5.579 | 0.0114 |

| Lung | 0.819 | 0.310–2.164 | 0.6887 |

| Adrenal gland | 1.330 | 0.401–4.409 | 0.6404 |

| Extra-thoracic

lymph node | 1.096 | 0.355–3.377 | 0.8737 |

| Pleural and/or

pericardial fluid | 3.066 | 1.660–5.663 | 0.0003 |

| Table IV.Logistic regression analysis for the

factors of an unfavorable response to chemotherapy (stable disease

and progressive disease). |

Table IV.

Logistic regression analysis for the

factors of an unfavorable response to chemotherapy (stable disease

and progressive disease).

| Independent

factor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Liver | 5.304 | 2.201–12.785 | 0.0002 |

| Bone | 0.528 | 0.178–1.563 | 0.2484 |

| Brain | 2.695 | 1.073–6.769 | 0.0348 |

| Lung | 1.571 | 0.508–4.856 | 0.4329 |

| Adrenal gland | 2.885 | 0.734–11.388 | 0.1291 |

| Extrathoracic lymph

node | 1.339 | 0.369–4.859 | 0.6568 |

| Pleural and/or

pericardial fluid | 1.535 | 0.721–3.270 | 0.2664 |

Multivariate analysis

In a multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional

hazards model, presence of liver metastasis (P=0.0001), bone

metastasis (P=0.0401), brain metastasis (P=0.0177) and pleural

and/or pericardial fluids (P=0.0020) were unfavorable prognostic

factors. However, lung (P=0.7028), adrenal gland (P=0.2405) and

extrathoracic lymph node metastasis (P=0.0672) were not

statistically significant prognostic factors (Table V).

| Table V.Multivariate analysis of prognostic

factors in patients with SCLC. |

Table V.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic

factors in patients with SCLC.

| Factor | Multivariate

analysis (Cox’s proportional hazards model)

|

|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Liver | 0.414 | 0.273–0.627 | 0.0001 |

| Bone | 0.643 | 0.422–0.980 | 0.0401 |

| Brain | 0.608 | 0.403–0.917 | 0.0177 |

| Lung | 0.903 | 0.534–1.527 | 0.7028 |

| Adrenal gland | 0.689 | 0.369–1.284 | 0.2405 |

| Extrathoracic lymph

node | 0.586 | 0.331–1.039 | 0.0672 |

| Pleural and/or

pericardial fluid | 0.608 | 0.443–0.833 | 0.0020 |

Discussion

The incidence of distant metastasis at the time of

initial diagnosis of SCLC in this study was 60.6%, and the most

common metastatic sites were the liver, bone, brain, lung and

adrenal glands. In this study, we examined whether specific organ

metastasis at the time of presentation had prognostic significance

in SCLC patients. For decades, the prognostic significance of bone

marrow involvement in SCLC patients has been reported (7,8).

Thereafter, several studies indicated that patients with multiple

metastatic sites had a significantly poor survival rate (9–11). Our

results revealed that there was a significant difference in

survival among patients without metastasis compared to those with

one metastatic site and those with two or more metastatic sites.

These results were consistent with previous studies (9–11). In

these studies, the site of involvement did not appear to have an

impact on survival (2,9); however, other researchers have

identified that specific organ metastasis is related to poor

prognosis (12–14). Bremnes et al reported that

liver and brain metastasis were independent prognostic factors in

ED-SCLC (12). Mohan et al

also revealed that brain metastasis was a significant predictor of

survival (13). In a study of 116

SCLC patients, Arinc et al indicated that bone metastasis

was one of the significant prognostic factors in univariate

analysis, but was not identified as a prognostic factor in

multivariate analysis (14). In the

present study, univariate analysis revealed that patients with sole

organ metastasis in the liver, bone, brain and lung had a poorer

prognosis compared to those without metastasis. However, in

multivariate analysis, liver, bone and brain metastasis were

unfavorable prognostic factors, while lung metastasis was not. In

our logistic regression analysis, the presence of liver metastasis,

brain metastasis and pleural and/or pericardial fluid demonstrated

a statistically significant correlation with poor PS. Liver

metastasis and brain metastasis also correlated with an unfavorable

response to chemotherapy. Therefore, these results indicate that

liver metastasis, brain metastasis and pleural and/or pericardial

fluid have certain associations with poor prognosis.

Nussbaum et al identified that multiple brain

metastases were common in patients with SCLC (15). Activity of daily living (ADL) may be

low in a number of patients with brain metastases, and may also

deteriorate in patients with bone metastases due to pain and

fracture. The discontinuation of chemotherapy due to the

deterioration of ADL in these patients has a certain correlation

with poor survival. With regard to liver metastasis, the majority

of SCLC patients had multiple nodules in our previous study

(16). SCLC may cause biliary tract

obstruction by metastasizing to lymph nodes in the porta hepatis or

hepatic parenchyma (17,18). The administration of chemotherapy

may be complicated by metastasis of the liver in the activation or

metabolism of several cytotoxic drugs commonly used in the

treatment of SCLC. Lung metastatic lesions usually respond well to

chemotherapy, and these lesions rarely cause complications unless

hemoptysis and respiratory tract obstruction develop. Further

studies are required to confirm the impact of metastasis of these

organs as observed in the present study.

Recently, Ignatius Ou and Zell reported the

applicability of the proposed International Association for the

Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) staging for SCLC, in comparison with

the current Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) 6th Tumor

Node Metastasis (TNM) edition (19). They concluded that patients with

pleural and/or pericardial effusion had a poorer prognosis compared

to those with metastatic disease (19). In the UICC TNM 7th edition, patients

with pleural effusion have an intermediate prognosis between LD-

and EL-SCLC (20). Our present

study also confirmed that patients with pleural and/or pericardial

effusion had a poorer prognosis compared to those without.

Despite these significant findings, this study has

limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design of the study meant

that it was complicated by lead time and length time biases.

Secondly, there was a lack of information with regard to the

development of distant metastases in the patients’ clinical

courses. Regardless of these limitations, we recognize that our

findings have certain clinical importance for the management of

future SCLC patients of unselected groups.

In conclusion, the therapeutic approach for treating

SCLC patients with distant metastases is complicated, as our

results suggest that existing liver, bone and brain metastasis

adversely affects the outcome of the disease. When deciding whether

or not to offer an intensive therapy, which may increase

treatment-related mortality, the patient’s medical condition,

including coexistence of such metastases, should be taken into

consideration, although favorable results have been reported in a

number of these patients.

References

|

1.

|

R FerraldeschiS BakaB JyotiC Faivre-FinnN

ThatcherP LoriganModern management of small-cell lung

cancerDrugs6721352152200710.2165/00003495-200767150-0000317927281

|

|

2.

|

NR FosterSJ MandrekarSE SchildPrognostic

factors differ by tumor stage for small cell lung cancer: a pooled

analysis of North Central Cancer Treatment Group

trialsCancer11527212731200910.1002/cncr.2431419402175

|

|

3.

|

W TravisE BrambillaH Muller-HermelinkC

HarrisTumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heartPathology and

Genetics World Health Organisation Classification of TumoursIARC

PressLyon2004

|

|

4.

|

M ZelenKeynote address on biostatistics

and data retrievalCancer Chemother Rep 34314219734580860

|

|

5.

|

FA ShepherdRJ GinsbergR HaddadImportance

of clinical staging in limited small-cell lung cancer: a valuable

system to separate prognostic subgroups. The University of Toronto

Lung Oncology GroupJ Clin Oncol111592159719938393098

|

|

6.

|

DR CoxRegression models and life tablesJ

Roy Statist Soc Ser B Metho341872201972

|

|

7.

|

WR BezwodaD LewisN LiviniBone marrow

involvement in anaplastic small cell lung cancer. Diagnosis,

hematologic features, and prognostic

implicationsCancer5817621765198610.1002/1097-0142(19861015)58:8%3C1762::AID-CNCR2820580830%3E3.0.CO;2-V3019512

|

|

8.

|

J ZychZ PolowiecE WiatrA BroniekE

Rowinska-ZakrzewskaThe prognostic significance of bone marrow

metastases in small cell lung cancer patientsLung

Cancer10239245199310.1016/0169-5002(93)90184-Y8075969

|

|

9.

|

F TasA AydinerE TopuzH CamlicaP SaipY

EralpFactors influencing the distribution of metastases and

survival in extensive disease small cell lung cancerActa

Oncol3810111015199910.1080/02841869943227510665754

|

|

10.

|

J LiCH DaiP ChenSurvival and prognostic

factors in small cell lung cancerMed

Oncol277381201010.1007/s12032-009-9174-319214813

|

|

11.

|

M TamuraH UeokaK KiuraPrognostic factors

of small-cell lung cancer in Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group

TrialsActa Med Okayama5210511119989588226

|

|

12.

|

RM BremnesS SundstromU AasebøS KaasaR

HatlevollS AamdalNorweigian Lung Cancer Study GroupThe value of

prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer: results from a

randomised multicenter study with minimum 5 year follow-upLung

Cancer39303313200312609569

|

|

13.

|

A MohanA GoyalP SinghSurvival in small

cell lung cancer in India: prognostic utility of clinical features,

laboratory parameters and response to treatmentIndian J

Cancer436774200610.4103/0019-509X.2588716790943

|

|

14.

|

S ArincU GonlugurO DevranPrognostic

factors in patients with small cell lung carcinomaMed

Oncol27237241201010.1007/s12032-009-9198-819399653

|

|

15.

|

ES NussbaumHR DjalilianKH ChoWA HallBrain

metastases. Histology, multiplicity, surgery, and

survivalCancer7817811988199610.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961015)78:8%3C1781::AID-CNCR19%3E3.0.CO;2-U8859192

|

|

16.

|

K KagohashiH SatohH IshikawaM OhtsukaK

SekizawaLiver metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis of lung

cancerMed Oncol202528200310.1385/MO:20:1:2512665681

|

|

17.

|

M ObaraH SatohYT YamashitaMetastatic small

cell lung cancer causing biliary obstructionMed

Oncol15292294199810.1007/BF027872179951697

|

|

18.

|

R OgawaT KodamaK KurishimaK KagohashiH

SatohPortal vein tumor thrombus of liver metastasis from lung

cancerActa Medica (Hradec Kralove)52163166200920369711

|

|

19.

|

SH Ignatius OuJA ZellThe applicability of

the proposed IASLC staging revisions to small cell lung cancer

(SCLC) with comparison to the current UICC 6th TNM EditionJ Thorac

Oncol4300310200919156001

|

|

20.

|

FA ShepherdJ CrowleyP Van HoutteThe

International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer lung cancer

staging project: proposals regarding the clinical staging of small

cell lung cancer in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the tumor,

node, metastasis classification for lung cancerJ Thorac

Oncol210671077200710.1097/JTO.0b013e31815bdc0d

|