Introduction

MPE is a rare benign variant of ependymoma that

occurs most commonly in the cauda equina and filum terminale of the

spinal cord (1,2). The majority of patients with MPEs are

young adults and only a limited number of MPEs have been reported

in elderly patients. MPEs are considered to represent grade I

tumors characterized by slow growth. The tumor is often intradural,

although local invasion and distant metastases are occasionally

observed (3,4). The typical histopathological features

of MPEs have been well described, whereas reports of hyaline

changes and low cellular variants are rarely published. The current

study presents an unusual case of MPE with marked hyaline

degeneration in an elderly male. The clinicopathological

observations of the case are described and analyzed. Written

informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case report

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

A 72-year-old male presented with a 10-month history

of lower back pain and dysesthesia at the lower abdominal level.

The pain was of sudden onset with radiation to the legs. Weakness

in the legs was also reported and the clinical signs were worsened

by sitting. There was no history of trauma. The patient showed

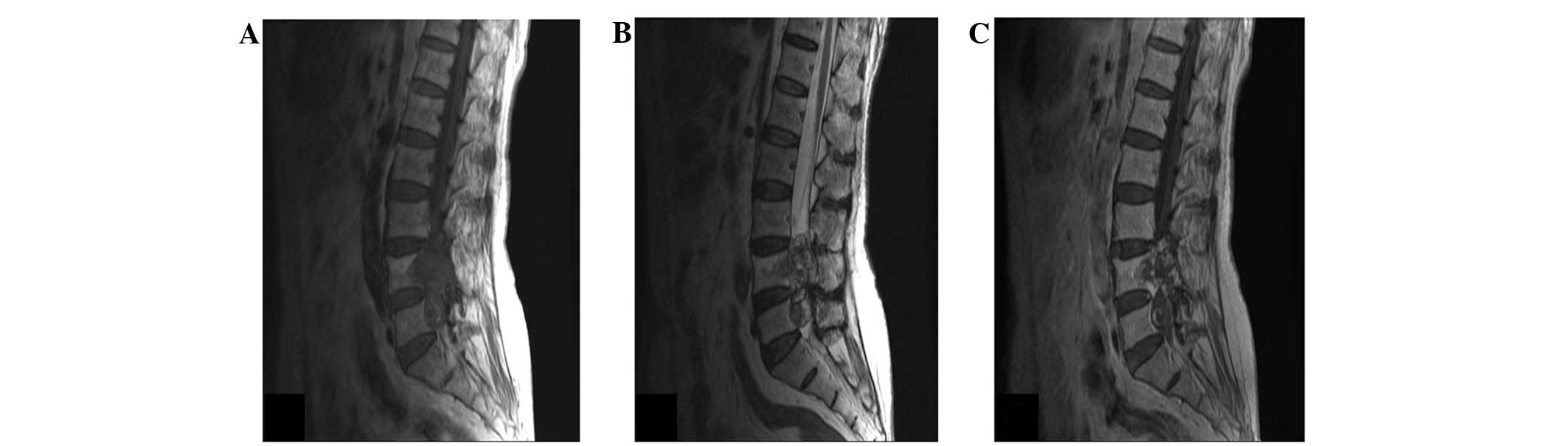

intermittent claudication after walking 200 m. Magnetic resonance

imaging revealed a mass involving the L4 and L5 vertebrae with

local bone destruction. The mass was hypointense on T1-weighted

images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images and enhanced

heterogeneously on post-contrast T1-weighted images (Fig. 1A–C). A total resection was performed

and the patient’s post-operative course was uneventful. No

subsequent adjuvant therapy was deemed necessary.

Pathological analysis

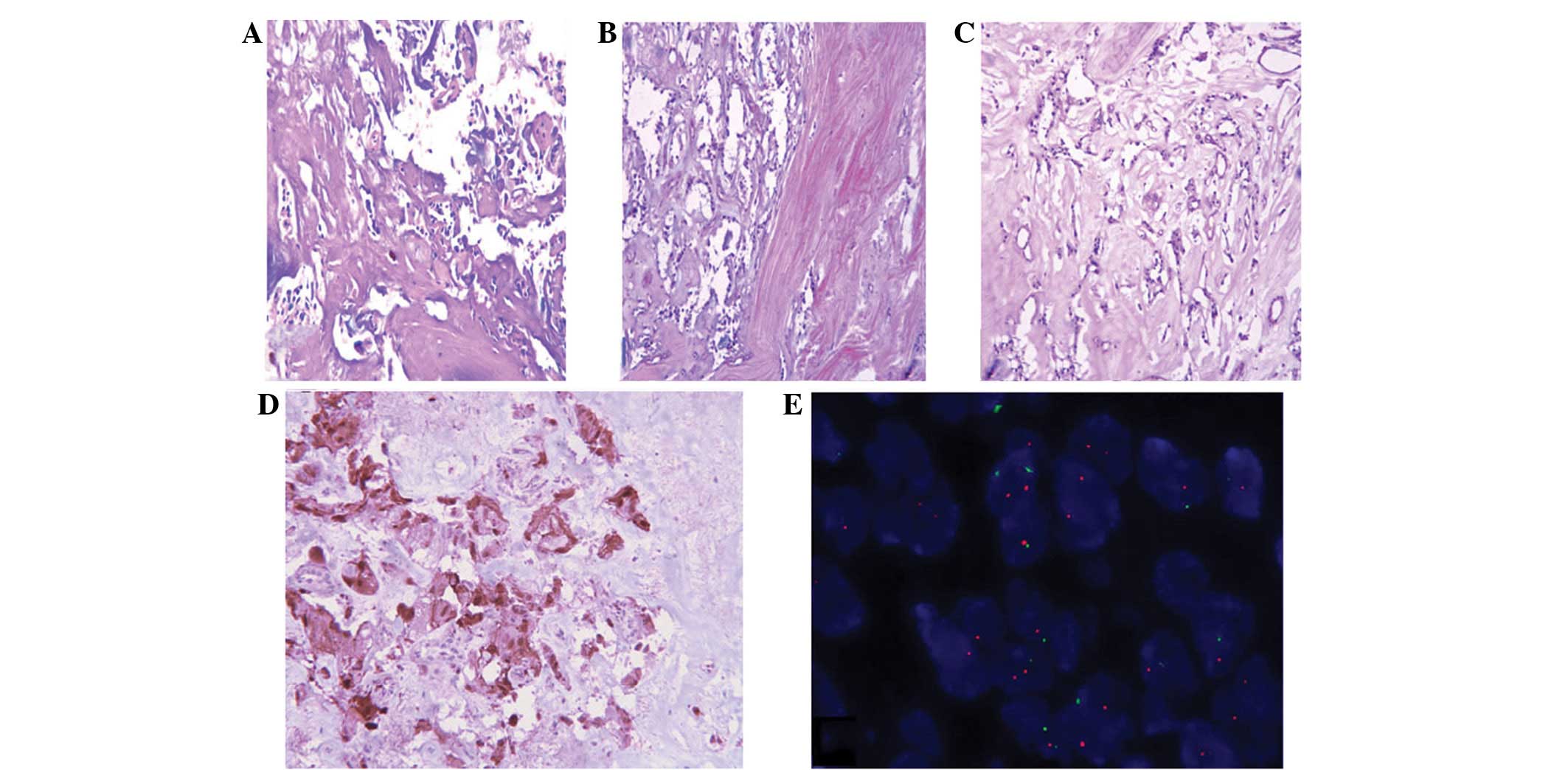

Microscopically, the tumor largely consisted of

areas with low cellularity. In less cellular areas, marked hyaline

changes were observed in the blood vascular walls and stroma

(Fig. 2A). In other areas, the

tumor showed pseudopapillary or reticular patterning formed by

cuboidal cells on a hyaline background (Fig. 2B and C). Mitotic figures and

necrosis were absent. The tumor cells showed marked positivity for

glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Fig. 2D) and S-100 proteins, whereas the

cells were negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA),

cytokeratins (CK) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The

Ki-67 labeling index was ∼3%. Since EGFR may be a predictor of

relapse in MPE (5), the EGFR gene

was analyzed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. No

amplification of the EGFR gene was observed (Fig. 2E). The results of pathological and

immunohistochemical studies were consistent with the ependymal

nature of neoplastic cells.

Discussion

MPE is a benign variant of ependymoma that has a

peak incidence between the third and fifth decades of life. It

generally occurs in the filum terminale, but has also been

identified in extra-spinal locations, including subcutaneous tissue

and the brain (6,7). Clinical symptoms are directly

associated with the mass location of the tumor. Histologically, it

is typically characterized by papillae formed by the arrangement of

cuboidal to columnar cells surrounding a central core, which

contains blood vessels and myxoid change. The genesis of the

stromal myxoid changes are indicative of an inundation of the

plasma proteins generally located within blood vessels (8). In the current case, the pronounced

deposition of hyaline materials was distributed among the tumor

cells and within the blood vessel walls. Lim et al (9) previously hypothesized that the

‘proteinaceous’ deposits and hyaline vascular change were a result

of increased vascular permeability that led to inundation of plasma

proteins surrounding extravascular spaces. MPEs are generally

slow-growing, therefore, the chronic long-standing anoxic

conditions may lead to various regressive changes and necrosis. An

additional explanation for the stromal change is the complicated

structure of the conus medullaris and filum terminale, as this

region is composed of an admixture of connective tissue, nerve

fibers and neuroglia. It may be possible that these unique

structural features result from the anatomical relationships of the

MPE (10). Certain studies have

indicated that, in specific circumstances, MPE cells produce basal

lamina material, particularly in regions where ependymal cells are

opposed to connective tissue (11,12).

In the present case, tumor cells showed marked cytoplasmic staining

for GFAP and S-100 protein, whereas immunoreactivity for CK, EMA,

chromogranin, EGFR and synaptophysin were all negative. In

addition, marked hyaline deposits were identified around the tumor

cells, and pseudopapillary patterns or ependymal rosettes were

rare. Therefore, in cases such as these, it is important to rule

out the possibility of schwannomas, chordomas and metastatic

mucinous adenocarcinomas. Spinal schwannomas appear on the myelin

sheath of the spine and represent between one-quarter to one-third

of all spinal tumors. Diagnostic features include a fibrous capsule

and Antoni A and Antoni B areas. Similar to in MPEs, hyaline

vessels and stroma are common in schwannomas and S100 is markedly

expressed. However, GFAP is negative. It is extremely important to

differentiate between a schwannoma and MPE prior to surgery, as an

MPE has the potential to disseminate through the cerebrospinal

fluid throughout the neuraxis and must be removed completely. The

most common differential diagnosis at this location is that of a

chordoma. The tumor cells are large with characteristic

physaliferous cytoplasm, and the immunocytochemistry of CK is

positive (13). Metastatic mucinous

adenocarcinomas show epithelial cords and groups with an acinar

arrangement. The cancer cells are more pleomorphic and are CK- and

EMA-positive. An analysis using electron microscopy is extremely

important for forming a differential diagnosis. Specific

ultrastructural features, including microvilli, cilia, desmosomal

attachments and cytoplasmic filaments, are indicative of a

diagnosis of MPE (14,15).

In conclusion, specific regressive changes are

observed in MPE and marked hyaline degeneration may lead to an

acellular growth pattern, therefore, it is important to rule out

the possibility of other tumors. The best curative treatment lies

in a complete surgical resection, and long-term follow-up of the

whole neuraxis must be performed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr

Wanchun Li (Department of Pathology, Nanjing Jinling Hospital) for

gathering clinical information from medical records and Dr Ozgur

Sahin (Department of Molecular and Cellular Oncology, The

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) for linguistic

assistance.

References

|

1.

|

Bagley CA, Kothbauer KF, Wilson S,

Bookland MJ, Epstein FJ and Jallo GI: Resection of myxopapillary

ependymomas in children. J Neurosurg. 106(4 Suppl): 261–267.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Nakamura M, Ishii K, Watanabe K, et al:

Long-term surgical outcomes for myxopapillary ependymomas of the

cauda equina. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 34:E756–E760. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Kulesza P, Tihan T and Ali SZ:

Myxopapillary ependymoma: cytomorphologic characteristics and

differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 26:247–250. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Zacharoulis S, Ji L, Pollack IF, et al:

Metastatic ependymoma: a multi-institutional retrospective analysis

of prognostic factors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 50:231–235. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Verma A, Zhou H, Chin S, Bruggers C,

Kestle J and Khatua S: EGFR as a predictor of relapse in

myxopapillary ependymoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 59:746–748. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Tseng YC, Hsu HL, Jung SM and Chen CJ:

Primary intracranial myxopapillary ependymomas: report of two cases

and review of the literature. Acta Radiol. 45:344–347. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Lee KJ, Min BW, Seo HJ and Cho CH:

Subcutaneous sacrococcygeal myxopapillary ependymoma in asian

female: a case report. J Clin Med Res. 4:61–63. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Sato H, Ohmura K, Mizushima M, Ito J and

Kuyama H: Myxopapillary ependymoma of the lateral ventricle. A

study on the mechanism of its stromal myxoid change. Acta Pathol

Jpn. 33:1017–1025. 1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Lim SC and Jang SJ: Myxopapillary

ependymoma of the fourth ventricle. Clin Neurol Neurosurg.

108:211–214. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Rawlinson DG, Herman MM and Rubinstein LJ:

The fine structure of a myxopapillary ependymoma of the filum

terminale. Acta Neuropathol. 25:1–13. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Miller C: The ultrastructure of the conus

medullaris and filum terminale. J Comp Neurol. 132:547–566. 1968.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Matyja E, Naganska E, Zabek M and Koziara

H: Myxopapillary ependymoma of the lateral ventricle with local

recurrences: histopathological and ultrastructural analysis of a

case. Folia Neuropathol. 41:51–57. 2003.

|

|

13.

|

Estrozi B, Queiroga E, Bacchi CE, et al:

Myxopapillary ependymoma of the posterior mediastinum. Ann Diagn

Pathol. 10:283–287. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Stern JB and Helwig EB: Ultrastructure of

subcutaneous sacrococcygeal myxopapillary ependymoma. Arch Pathol

Lab Med. 105:524–526. 1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Kindblom LG, Lodding P, Hagmar B and

Stenman G: Metastasizing myxopapillary ependymoma of the

sacrococcygeal region. A clinico-pathologic, light- and

electronmicroscopic, immunohistochemical, tissue culture, and

cytogenetic analysis of a case. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand

A. 94:79–90. 1986.

|