Introduction

Gastrinoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumor with an

incidence of approximately one to three cases per year for every

1,000,000 individuals (1). At

present, ~50–60% of gastrinoma cases are malignant (2) and a five-year survival rate of

patients with metastatic gastrinoma is possible for 20–40% of these

cases (3). To the best of our

knowledge, 90% of gastrinomas are located in the gastrinoma

triangle comprising the duodenum (60–80%) and the pancreas

(10–40%), or in the adjacent lymph nodes (1). The first common signs of gastrinoma

include secretory diarrhea, peptic telephium, severe esophagitis

and hypercalcemia (4). Ectopia and

asymptomatic gastrinoma are rarely reported in the literature. In

the current study, a rare case report of gastrinoma is presented

and the underlying clinical and pathological factors that may have

resulted in the misdiagnosis are investigated. The aim of the

present study was to focus the attention of clinicians on this type

of cancer by providing preliminary clinical experience in order to

improve its diagnosis and treatment.

Case report

On December 15, 2006, a 39-year-old female was

admitted to the Anhui Provincial Hospital (Anhui, China) following

the observation of a pancreatic body and a tail lesion in an annual

periodic health examination. The patient had not experienced any

discomfort and was hemodynamically stable. A benign abdominal

examination was conducted and all of the blood and biochemical

parameters were within their respective reference ranges. The

family and personal medical histories were unremarkable. Written

informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of

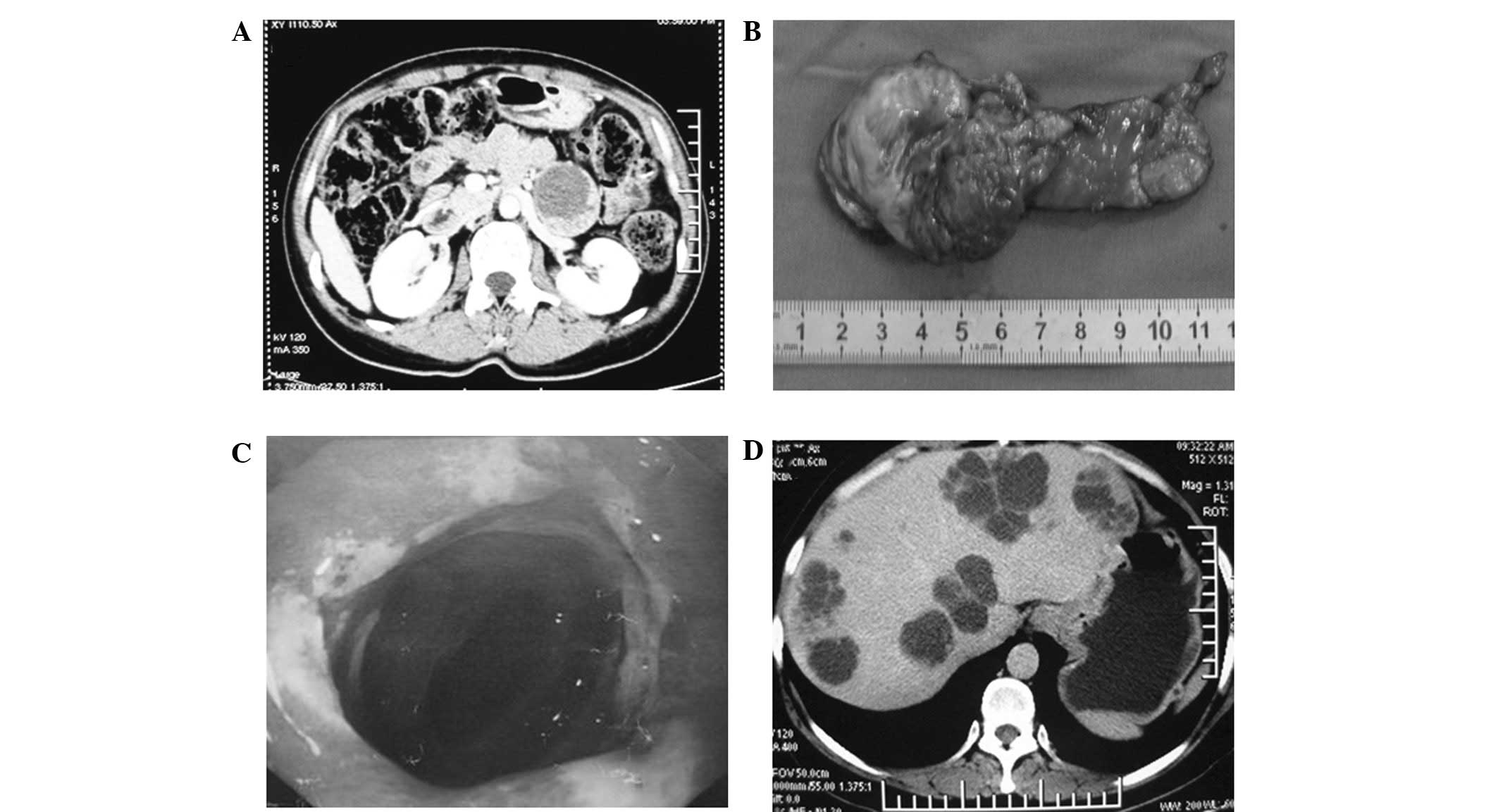

the present study and any accompanying images. Enhanced computed

tomography (CT) revealed a cystic mass in the pancreatic body and

tail (Fig. 1A). Considering these

observations, the patient was diagnosed with pancreatic body and

tail space-occupying lesions. The patient also underwent a distal

pancreatectomy (Fig. 1B). A solid

pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPTP) was suspected as a

result of postoperative pathology (World Health Organisation, 2010

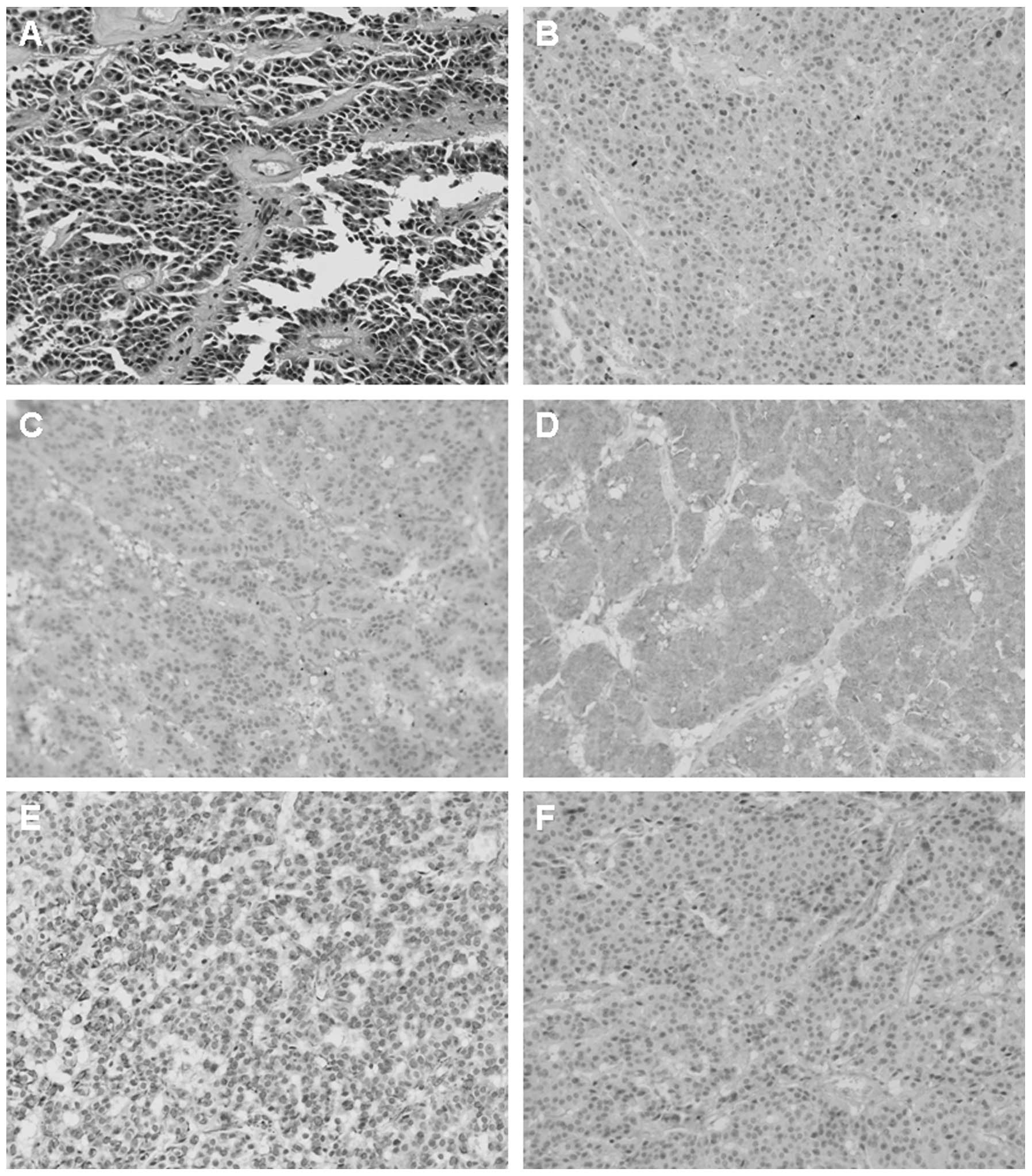

guideline: Low malignant potential) (5). Immunohistochemistry results indicated

that the tumor cells were positive for α1-antichymotrypsin,

synaptophysin (Syn), vimentin and neuron-specific enolase (Fig. 2). In the following year, the patient

remained well and no apparent symptoms occurred. However, the

patient was referred to the Anhui Provincial Hospital after

presenting with stomachache in December 2008. After 24 months of

follow-up, a gastroscopy revealed a duodenal bulbar ulcer and

hemorrhagic gastric body inflammation (Fig. 1C). B-scan ultrasonography of the

abdomen also revealed a low-density liver lesion (size, 1 cm). The

patient was diagnosed with a peptic ulcer (active stage) and was

administered proton pump inhibitor (PPIs; including omeprazole)

treatment. Following the second hospitalization, the condition and

ulcer symptoms of the patient improved during the follow-up period.

Although the ulcer healed, an additional gastroscopy in June 2009

showed gastrointestinal erosion. B-scan ultrasonography revealed

that multiple, small low-density liver lesions in the left lobe of

the liver. The patient was continuously treated with the PPI

(omeprazole). However, the patient rejected further treatment, as

the low-density liver lesion was asymptomatic. In October 2010, a

gastroscopy demonstrated the presence of an ulcer that was

affecting the stomach and duodenum. Although the PPI was

continuously administered, the patient exhibited symptoms,

including belching and acidic reflux. Enhanced CT scans of the

abdomen revealed multiple round lesions located in the left and

right lobes of the liver (Fig. 1D).

Positron emission tomography-CT showed pancreatic malignant lesions

and multiple metastatic neoplasia of the liver. A gastrinoma with

liver metastasis was suspected on the basis of the patient’s

medical history. The serum gastrin level of the patient (237.97

pg/ml) was abnormal (normal, <100 pg/ml). A new biopsy specimen

from the pancreatic body and tail mass (obtained at the Zhongshan

Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China) indicated a

neuroendocrine carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining for gastrin,

chromogranin (CgA) and Ki-67 was positive. Gastrinoma of the

pancreatic body and tail with liver metastases was confirmed. The

patient subsequently received treatment with octreotide acetate (20

mg/month) and sunitinib (37.5 mg/day), which had a poor effect.

Finally, a liver transplant was successfully performed for the

patient on June 1, 2011. The patient currently maintains a good

overall condition.

Discussion

The current study presents a rare case of a female

patient with malignant pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with

liver metastases, who was initially misdiagnosed with SPTP. The

potential underlying clinical and pathological factors that may

have led to misdiagnosis are analyzed and listed in the present

study.

First, the majority of gastrinomas are located in

the gastrinoma triangle (comprising of the duodenum and the

pancreas) or in the adjacent lymph nodes (1), whereas the present case of gastrinoma

occurred in an unusual location, the pancreatic body and tail,

which is outside the typical triangle. Therefore, the location

complicated the diagnosis.

Secondly, it is known that gastrohelcosis and

diarrhea are common first signs of a gastrinoma, particularly in

non-functioning cases, while SPTP are generally characterized in

young females with no clinical symptoms prior to the onset of the

illness, negative tumor markers and without a history of peptic

ulcers (6). Combined with the

clinical data of the patient, it is particularly difficult to

initially differentiate between gastrinomas and SPTP. This was

another significant cause of erroneous diagnosis during the early

stage of the disease in the present case.

Thirdly, pathological assessment is the most

reliable diagnostic basis and considered to be the gold standard.

However, it is worth noting that the characteristics of hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E) staining with gastrinoma and solid

pseudopapillary tumors are similar and may be confused, even when

specific typical immunohistochemical indicators, such as Syn or CgA

(7), are observed. Interstitial

hyaline degeneration and false papillary structure are the two

microscopically characterized changes of SPTP and corresponding

changes are observed in the pathological section when performing

H&E staining. Therefore, combined with the clinical data and

experiences of the patient, our pathologists were confident in the

initial diagnosis of SPTP. However, whether pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors can be diagnosed with any certainty when the

abovementioned immunohistochemical indicators are positive remains

a controversial issue. The associated literatures on this issue

were reviewed and certain studies found that specific SPTP patients

were misdiagnosed with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors even though

expression of Syn and CgA was positive (7–11).

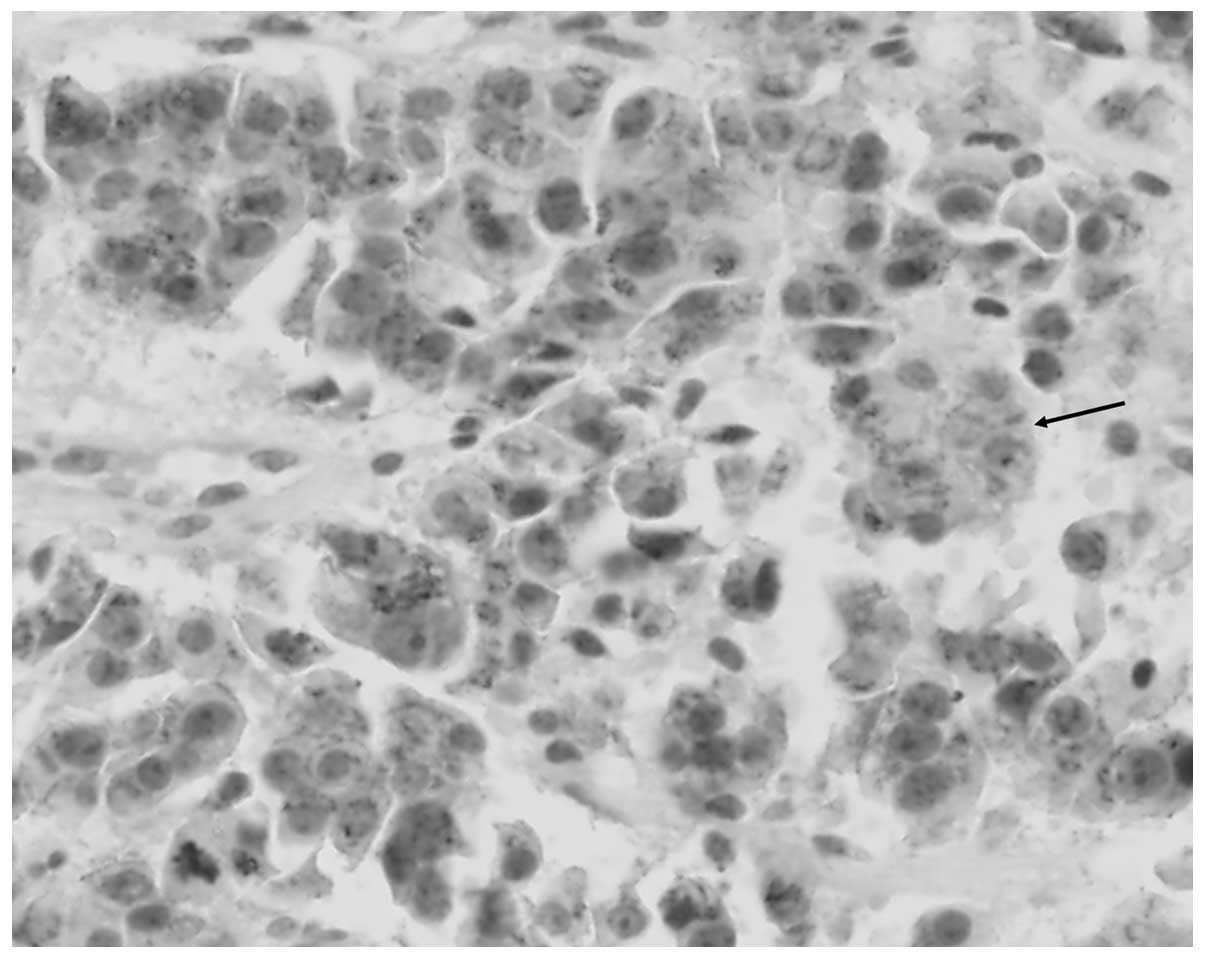

Thus, the classic index is not completely reliable, however, the

studies also found that E-cadherin and β-catenin were potentially

effective in the differential diagnosis of the two diseases.

Therefore, in the present study the immunostaining of β-catenin was

conducted, which supplemented our results and were consistent with

previous studies (Fig. 3). However,

this conclusion requires support from large-scale clinical

trials.

Finally and most significantly, a monism, rather

than pluralism, approach is required to diagnose the disease. The

patient in the present case experienced intractable recurrent

peptic ulcers and multiple low-density liver lesions developed

continuously during the postoperative follow-up period. If

clinicians are able to connect these novel conditions with previous

surgical history, it may allow a correct revised diagnosis to be

obtained promptly following surgery.

Therefore, a serious misdiagnosis emphasizes the

requirement for a more accurate differential diagnosis of such a

rare case of a disease without a typical clinical manifestation.

The aim of the present study was to focus the attention of

clinicians on this disease in order to improve its diagnosis and

treatment to a certain extent.

In conclusion, pancreatic gastrinoma should be

carefully differentiated from SPTP during diagnosis. Immunostaining

of E-cadherin and β-catenin may be necessary to aid with the

differential diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81172364 and

81201906).

References

|

1

|

Jensen RT, Niederle B, Mitry E, et al;

Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor

Society. Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology.

84:173–182. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pachera S, Yokoyama Y, Nishio H, et al: A

rare surgical case of multiple liver resections for recurrent liver

metastases from pancreatic gastrinoma: liver and vena cava

resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 16:692–698. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yamaguchi M, Yamada Y, Hosokawa Y, et al:

Long-term suppressive effect of octreotide on progression of

metastatic gastrinoma with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1:

seven-year follow up. Intern Med. 49:1557–1563. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al:

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Clinical presentation in 261 patients.

Medicine (Baltimore). 79:379–411. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bosman FT, Cameiro F, Hruban RH and Theise

ND: WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive system. 4th

edition. IARC Press; Lyon: 2010

|

|

6

|

Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, Sipos B,

Lüttges J, Kremer B and Klöppel G: Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas

and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases

and a classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 445:168–178. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu BA, Li ZM, Su ZS and She XL:

Pathological differential diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary

neoplasm and endocrine tumors of the pancreas. World J

Gastroenterol. 16:1025–1030. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tanaka Y, Kato K, Notohara K, et al:

Frequent beta-catenin mutation and cytoplasmic/nuclear accumulation

in pancreatic solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm. Cancer Res.

61:8401–8404. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim MJ, Jang SJ and Yu E: Loss of

E-cadherin and cytoplasmic-nuclear expression of beta-catenin are

the most useful immunoprofiles in the diagnosis of

solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Hum Pathol.

39:251–258. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Abraham SC, Klimstra DS, Wilentz RE, et

al: Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas are genetically

distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and almost always

harbor beta-catenin mutations. Am J Pathol. 160:1361–1369. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tanaka Y, Notohara K, Kato K, et al:

Usefulness of beta-catenin immunostaining for the differential

diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Am J

Surg Pathol. 26:818–820. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|