Introduction

Male breast cancer is a rare disease accounting for

<1% of all diagnosed breast cases (1). The only ethnic group with a higher than

average incidence of male breast cancer is Jewish men, regardless

of their residence (2). A previous

study determined a strong family predisposition for the disease,

with an odds ratio of 3.3 (3). It is

recognized that breast cancer (BRCA) mutations may be

detected in a significant portion of male breast cancer cases

(primarily BRCA2) and the National Comprehensive Cancer

Network guidelines recommend genetic testing for such patients

(4). It has been suggested that male

breast cancer is associated with a poorer prognosis compared with

females, largely due to delays in diagnosis, lack of clinical care

pathways and associated comorbidities due to the advanced age of

patients (5). A recent comparative

analysis of menopausal status in female patients with breast cancer

concluded poorer outcomes for male patients with breast cancer

compared with postmenopausal females and similar outcomes to

premenopausal female patients with breast cancer (6). Recommendations for treatment in males

are extrapolated from extensive evidence in women. Due to lack of

breast tissue, simple mastectomy is commonly the preferred surgical

procedure. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is feasible and is being

performed more frequently in cases of male breast cancer. Given the

absence of terminal lobules in the male breast, the disease is

typically of a ductal type and hormone receptor-positive. Human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positivity is rare, with

a recent large multinational study reporting that this

characteristic was observed in <5% of cases (7). In the same study, a trend of improvement

in overall survival (OS) was also observed over time in men with

breast cancer (7).

The aim of the present study was to examine the

clinical and pathological characteristics, treatment patterns and

outcomes of a series of male patients with breast cancer, who were

consecutively treated at a single institution from January 1995 to

December 2015.

Patients and methods

Patients

The current study retrospectively reviewed medical

records of all male patients diagnosed with breast cancer over the

last 20 years from January 1995 to December 2015 at the Oncology

Department, Faculty Hospital Trenčín (Trenčín, Slovakia), which

serves a population of >600,000 inhabitants. All 21 cases

identified in this time period were included in the present study.

Individual patient records were reviewed and the relevant data was

obtained, including stage at presentation [based on the 7th edition

of the Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) classification system] (8), histological classification and tumor

biomarkers, and details regarding treatment and follow-up. The

study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty Hospital

Trenčín.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc

15.2 software (www.medcalc.org). The patients'

characteristics were summarized using the median (range) for

continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical

variables. Survival analysis was used only for patients treated

with curative intent. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to

calculate OS rate from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of

last follow-up or mortality, and disease-free survival (DFS) was

calculated from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of

progression or mortality.

Results

Patient clinicopathological

characteristics

All 21 male patients were diagnosed with invasive

breast cancer during the study period, which was <1% of the

number of female cases diagnosed at the same time. The median age

was 65.6 years (range, 51–86) and the majority of patients were

over 60 years at diagnosis (71%). As presented in Table I, the primary tumors in 8 patients

were staged as pT1, whilst 6 patients were staged as pT2 and 7 as

pT4. No patients presented with pT3 or Tis primary tumors. Axillary

lymph node involvement was present in 11 patients (52%) and 1

patient presented with metastatic disease (cytologically verified

malignant pleural effusion) at the time of diagnosis. According to

the TNM staging system (8), 6

patients were diagnosed with stage I disease, while 8 patients were

stage II, 6 patients stage III and 1 patient stage IV. With regards

to histological subtypes, invasive ductal cancer (invasive

carcinomas of no special type) was present in 19 patients and

invasive lobular cancer was present in 2 patients. Hormone receptor

status was examined in 18 patients, of which 15 (83%) were estrogen

receptor (ER)-positive and 13 (72%) were progesterone receptor

(PR)-positive. Only 1 out of 11 patients examined for HER2 status

was positive (9%). Only 2 patients were triple

(ER/PR/HER2)-negative. A total of 12 patients had grade 2 disease,

while 5 patients had grade 1 and 4 had grade 3. BRCA testing

was not performed on the majority of patients as reimbursement for

male breast cancer was not in place until recent years. All 6

patients analyzed had normal karyotypes without any BRCA

mutations.

| Table I.Clinicopathological variables of male

patients with invasive breast cancer. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological variables of male

patients with invasive breast cancer.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|

| Tumor size |

| pT1 | 8 (38) |

| pT2 | 6 (29) |

| pT3 | 0(0) |

| pT4 | 7 (33) |

| Nodal status |

| N0 | 10 (48) |

| N+ | 11 (52) |

| Metastases |

| Yes | 1 (5) |

| No | 20 (95) |

| Grade |

| 1 | 5

(24) |

| 2 | 12 (57) |

| 3 | 4

(19) |

| Histology |

| Ductal

carcinoma in situ | 0 (0) |

| Invasive

ductal carcinoma | 19 (90) |

| Invasive

lobular carcinoma | 2

(10) |

| Estrogen

receptor |

|

Positive | 15 (83) |

|

Negative | 3

(17) |

| N/A | 3 (−) |

| Progesterone

receptor |

|

Positive | 13 (72) |

|

Negative | 5

(28) |

| N/A | 3 (−) |

| HER2 |

|

Positive | 1

(9) |

|

Negative | 10

(91) |

| N/A | 10 (−) |

Treatment regimens

As presented in Table

II, a total of 20 patients underwent primary surgical treatment

(simple mastectomy) for localized breast cancer. The axilla was

surgically staged in all 20 patients undergoing primary surgical

treatment; axillary lymph node dissection was performed in 19

patients and sentinel node biopsy was performed in 1 patient.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 9 patients. Indications

for adjuvant systemic treatment were extrapolated from breast

cancer in women. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy [adriamycin and

cyclophosphamide, or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), adriamycin and

cyclophosphamide] was administered to 5 patients, sequential

chemotherapy based on anthracycline and taxane/trastuzumab was

administered to 1 patient and cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and

5-FU was given to 3 patients (who had been diagnosed >10 years

previously). Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to 12 patients,

with a total dose of 50 Gy (25 fractions over 5 weeks) with/without

additional boosts to the tumor bed. Finally, 12 patients were

treated with 5-year-long adjuvant hormonal treatment, consisting of

9 patients who were administered tamoxifen alone and 3 patients who

underwent sequential hormonal therapy consisting of tamoxifen and

aromatase inhibitor. One HER2-positive patient was administered

adjuvant trastuzumab concurrently with adjuvant taxane treatment.

Adjuvant trastuzumab was continued for 1 year. Progression to stage

IV occurred in 3 patients, who were initially stage II or III,

following curative treatment. All of these patients were treated

with palliative chemotherapy (anthracycline-based, taxane-based or

capecitabine-based) and 2 also received additional hormonal therapy

(tamoxifen). Palliative radiotherapy was delivered to 1 patient for

skeletal metastases. One patient with initially metastatic disease

to the pleura was treated with palliative chemotherapy

(anthracycline-based) followed by tamoxifen, and upon progression

was treated with taxane and aromatase inhibitors, in addition to

luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist.

| Table II.Treatment details of male patients

with invasive breast cancer. |

Table II.

Treatment details of male patients

with invasive breast cancer.

| Treatment | n (%) |

|---|

| Surgery (n=21) |

|

Mastectomy | 20

(95) |

| Wide

local excision | 0

(0) |

| No breast

surgery | 1

(5) |

| Axillary

lymph node dissection | 19

(90) |

| Sentinel

lymph node biopsy | 1

(5) |

| No

surgery in axilla | 1

(5) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy

(n=20) |

| Yes | 12 (60) |

| No | 8

(40) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy

(n=20) |

| Yes | 9

(45) |

|

Anthracyclin-based | 5

(56) |

|

Antracyclin

followed by taxane/trastuzumab | 1

(11) |

|

CMF | 3

(33) |

| No | 3

(55) |

| Adjuvant hormonal

therapy (n=14) |

| Yes | 12 (86) |

|

Tamoxifen | 9

(75) |

|

Aromatase

inhibitors | 0 (0) |

|

Tamoxifen followed

by aromatase inhibitors | 3

(25) |

| No | 2

(14) |

Patient outcomes

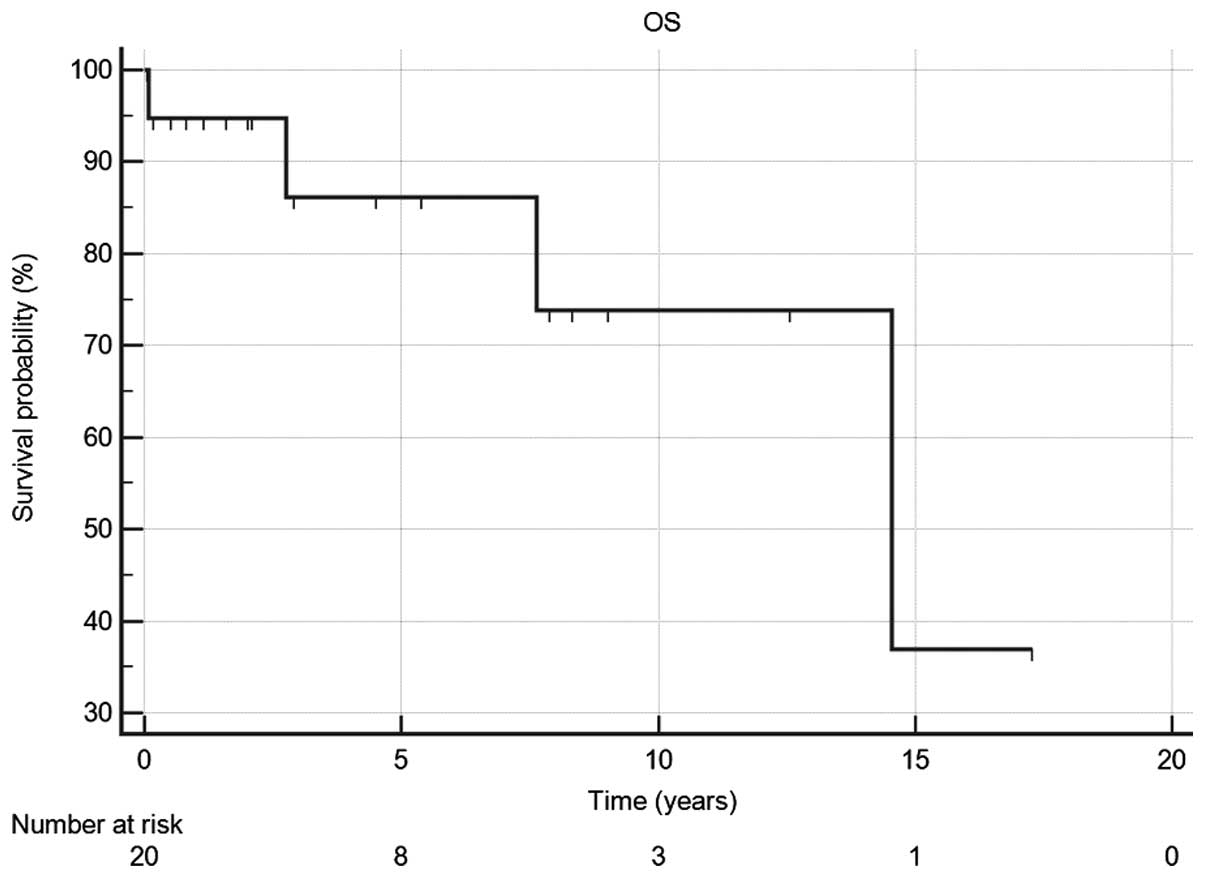

A total of 4 patients succumbed during the median

follow-up period of 4.5 years. Two patients succumbed due to

progression of the disease and the cause of mortality regarding the

other two patients is unknown. The 5- and 10-year OS rates were 87

and 74%, respectively (Fig. 1). The

estimated median DFS for the same population was 9.5 years (95% CI,

6.2–14.6) and 5-year DFS rate was 86%.

Discussion

Male patients with breast cancer tend to present

later in life than females and the incidence of male breast cancer,

although much lower than in females, is rising (1). Incidence of male breast cancer in

Slovakia is ~0.8% of all female breast cancer cases, which is

similar to that of Western Europe (9). Furthermore, 83% of the patients in the

current study were hormone receptor-positive, while only 9% of

patients were HER2-positive, which is in line with a recent

retrospective study by Cardoso et al (7). Given this fact, the luminal A molecular

subtype was predominantly observed in 58% of patients in the same

study (7). Additional comparative

biomarker studies of matched cohorts confirm a higher predominance

of ER-positivity and luminal A subtypes in men (10). This knowledge is important for

practicing oncologists, as all newly diagnosed males with breast

cancer with negative hormonal status should undergo a thorough

pathological review so that the opportunity for hormonal treatment

is not missed. The present study observed only 2 cases of lobular

carcinoma, which is a similar number reported by a previous

population-based study (11).

Surgical treatment of male breast cancer usually includes

mastectomy, as cosmetic outcomes are typically less important than

in women. Experience with sentinel lymph node biopsy in men is

gaining wider acceptance among breast surgeons and is a recommended

method of axillary staging of early cancer in women. The rarity of

male breast cancer precludes prospective studies that may

potentially guide the development of optimal treatment regimens.

The decisions made regarding treatment in the present study were

based on general guidelines for breast cancer in women, as

recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology (12). Limitations of the current study

include the small number of patients diagnosed and treated over

several years for a relatively rare disease. The majority of

patients with positive axillary lymph nodes and/or pT4 primary

tumor stage received adjuvant chemotherapy and chest-wall

radiotherapy. All but 2 patients with ER-positive tumors received

hormone treatment, initially with tamoxifen. One patient without

hormonal treatment arrived from another institution and the other

is currently finishing adjuvant chemotherapy. Tamoxifen remains the

standard hormonal treatment in adjuvant and metastatic settings for

male breast cancer (13). Hormonal

treatment is preferred in palliative setting as outcomes are

comparable with chemotherapy with less toxicity in women (14). The present study incorporated hormonal

manipulation in the treatment strategies for all eligible

palliative male breast cancer patients and there was no requirement

for rapid tumor response.

Incorporation of aromatase inhibitors, a standard

treatment approach in women, remains a contentious issue in male

breast cancer. Aromatase, an estrogen synthetase, is a key enzyme

in estrogen synthesis, which is expressed not only in the gonads

and peripheral tissues (including fat and bone), but also

intratumorally (15). In men, 60% of

circulating estradiol (E2) is produced by the testes either

directly or by conversion from testicular androgens (16). The remaining portion is derived from

the conversion of adrenal androgens (16). Thus, the production of testicular and

adrenal androgens, together with activity of aromatase enzyme,

determine plasma estrogen concentration in men. LHRH agonists (also

known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) are used in

premenopausal women with breast cancer to reduce the production of

ovarian estrogen and in castrate-sensitive prostate cancer in

males. LHRH administration yields reduction of testosterone and

estrogen produced by the testes (17). Combination with aromatase inhibitors

may further block estrogen production via aromatization.

Prospective and retrospective measurements of plasma E2,

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and testosterone in men treated

with only aromatase inhibitors have been reported (18,19), with

results demonstrating that E2 levels decreased with treatment, but

testosterone and FSH levels increased. These measurements confirmed

a positive feedback loop between increasing FSH and testosterone.

As testosterone is a substrate for aromatase, further E2

suppression may be achieved with LHRH analogs. A recent pooled

analysis of 105 male breast cancer cases demonstrated the

effectiveness of the aforementioned strategy (a 3-fold increase in

clinical benefit rate) (20), and in

a smaller analysis of 60 patients, a survival benefit was observed

following use of the combination strategy (21). However, a phase II trial investigating

this further was closed prematurely due to poor accrual (22). As this preclinical data suggests that

complete hormonal suppression with aromatase inhibitors in men is

not possible, they are (as monotherapy) not considered standard

treatment in male breast cancer. All in all, tamoxifen continues to

be administered as a standard adjuvant treatment in cases of male

breast cancer, but dual treatment with LHRH agonists (or

orchiectomy) and aromatase inhibitors is gaining ground in

metastatic male breast cancer (23).

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for high-risk female patients

with breast cancer, and by extrapolation, its effectiveness is

assumed to apply to the treatment of males with the disease. In the

present study, out of 14 patients with stage II or III disease, 5

patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy due to advanced age,

patient or physician choice, and comorbidities. The 5- (87%) and

10-year (74%) OS rates and the 5-year DFS rate estimated in the

current study are consistent with previously published studies

(13,24–26).

Due to the rarity of male breast cancer and largely

anecdotal evidence from case reports, the International Male Breast

Cancer Program was created under auspices of the European

Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the

Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium. In this program, a

prospective cohort study analyzing a collection of DNA and tumor

samples is planned. This program aims to advance the treatment of

male breast cancer in a similar manner to how therapies have

progressed for women with the disease. Male breast cancer is a rare

disease and there are no prospective studies to inform current

practice. As the disease has numerous similarities to breast cancer

in women, treatment strategies are extrapolated from female breast

cancer. Over the last 20 years, significant progress has been made

in physician detection, investigation and treatment of male breast

cancer. The encouraging results of the present study may give

patients and professionals confidence in future treatment of the

disease, which was once considered to have a grave prognosis.

In conclusion, the present study analyzed patients

with breast cancer, who had been diagnosed over the last 20 years

at the Oncology Department, Faculty Hospital Trenčín. In line with

the published literature, the majority of patients presented with

invasive ductal carcinoma with positive hormone receptors. HER2

positivity was rare. In order to improve knowledge regarding the

treatment of patients with this rare cancer, the cases reviewed in

the present study should be entered into a prospectively maintained

international database. In addition, clinical trials designed for

this patient population are required. Alternatively, patients with

male breast cancer may benefit from being enrolled into selected

clinical trials originally designed for women, where extensive

networks of clinical research units already successfully

collaborate.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

DFS

|

disease-free survival

|

|

ER

|

estrogen receptor

|

|

PR

|

progesterone receptor

|

|

HER2

|

human epidermal growth factor receptor

2

|

|

E2

|

estradiol

|

|

LHRH

|

luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone

agonist

|

|

FSH

|

follicle-stimulating hormone

|

References

|

1

|

Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J and Rosenberg

PS: Male breast cancer: A population-based comparison with female

breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 28:232–239. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mabuchi K, Bross DS and Kessler II: Risk

factors for male breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 74:371–375.

1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ewertz M, Holmberg L, Tretli S, Pedersen

BV and Kristensen A: Risk factors for male breast cancer-a

case-control study from Scandinavia. Acta Oncol. 40:467–471. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

NCCN: Genetic/Familial High-Risk

Assessment: Breast and Ovarian Cancer. 2015.http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdfAccessed.

January 1–2016

|

|

5

|

Müller AC, Gani C, Rehm HM, Eckert F,

Bamberg M, Hehr T and Weinmann M: Are there biologic differences

between male and female breast cancer explaining inferior outcome

of men despite equal stage and treatment?! Strahlenther Onkol.

188:782–787. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yu XF, Yang HJ, Yu Y, Zou DH and Miao LL:

A prognostic analysis of male breast cancer (MBC) compared with

post-menopausal female breast cancer (FBC). PLoS One.

10:e01366702015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cardoso F, Bartlett J and Slaets L:

Abstract S6-05: Characterization of male breast cancer: First

results of the EORTC10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male BC

Program. Cancer Res. 75:S6–05. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK and Wittekind

C: The TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (7th).

Wiley-Blackwell. Geneva: 2009.

|

|

9

|

Diba CS: Cancer incidence in the Slovak

Republic. National Health Information Center. Bratislava:

2009.http://www.nczisk.sk/Documents/publikacie/analyticke/incidencia_zhubnych_nadorov_2009.pdfAccessed.

January 2–2016

|

|

10

|

Shaaban AM, Ball GR, Brannan RA, Cserni G,

Di Benedetto A, Dent J, Fulford L, Honarpisheh H, Jordan L, Jones

JL, et al: A comparative biomarker study of 514 matched cases of

male and female breast cancer reveals gender-specific biological

differences. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 133:949–958. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Leone JP, Leone J, Zwenger AO, Iturbe J,

Vallejo CT and Leone BA: Prognostic significance of tumor subtypes

in male breast cancer: A population-based study. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 152:601–609. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S,

Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rutgers E, Zackrisson S and Cardoso

F: ESMO Guidelines Committee: Primary breast cancer: ESMO clinical

practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann

Oncol. 26(Suppl 5): v8–v30. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bradley KL, Tyldesley S, Speers CH, Woods

R and Villa D: Contemporary systemic therapy for male breast

cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 14:31–39. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Partridge AH, Rumble RB, Carey LA, Come

SE, Davidson NE, Di Leo A, Gralow J, Hortobagyi GN, Moy B, Yee D,

et al: Chemotherapy and targeted therapy for women with human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (or unknown) advanced

breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical

Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 32:3307–3329. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sasano H and Harada N: Intratumoral

aromatase in human breast, endometrial and ovarian malignancies.

Endocr Rev. 19:593–607. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

de Ronde W and de Jong FH: Aromatase

inhibitors in men: Effects and therapeutic options. Reprod Biol

Endocrinol. 9:932011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nordman IC and Dalley DN: Breast cancer in

men: Should aromatase inhibitors become first-line hormonal

treatment? Breast J. 14:562–569. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Doyen J, Italiano A, Largillier R, Ferrero

JM, Fontana X and Thyss A: Aromatase inhibition in male breast

cancer patients: Biological and clinical implications. Ann Oncol.

21:1243–1245. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bighin C, Lunardi G, Del Mastro L, Marroni

P, Taveggia P, Levaggi A, Giraudi S and Pronzato P: Estrone

sulphate, FSH and testosterone levels in two male breast cancer

patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Oncologist.

15:1270–1272. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Azim HA Jr,

Chrysikos D, Dimopoulos MA and Psaltopoulou T: Aromatase inhibitors

in male breast cancer: A pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

151:141–147. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Clinical trials: S0511, goserelin and

anastrozole in treating men with recurrent or metastatic breast

cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00217659Accessed.

January 25–2016

|

|

22

|

Di Lauro L, Pizzuti L, Barba M, Sergi D,

Sperduti I, Mottolese M, Amoreo CA, Belli F, Vici P, Speirs V, et

al: Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in metastatic

male breast cancer: Results from a pooled analysis. J Hematol

Oncol. 8:532015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, Giordano

S, Domchek S, Anderson WF, Bartlett JM, Gelmon K, Nahleh Z, Bergh

J, et al: Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: Summary

and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 28:2114–2122. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

de Ieso PB, Potter AE, Le H, Luke C and

Gowda RV: Male breast cancer: A 30-year experience in south

Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 8:187–193. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Iorfida M, Bagnardi V, Rotmensz N, Munzone

E, Bonanni B, Viale G, Pruneri G, Mazza M, Cardillo A, Veronesi P,

et al: Outcome of male breast cancer: A matched single-institution

series. Clin Breast Cancer. 14:371–377. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Masci G, Caruso M, Caruso F, Salvini P,

Carnaghi C, Giordano L, Miserocchi V, Losurdo A, Zuradelli M,

Torrisi R, et al: Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical

characteristics in male breast cancer: A retrospective case series.

Oncologist. 20:586–592. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|