Introduction

Prostate, lung and colorectal cancer account for

~42% of all cancer types in men, and prostate cancer (PCa) accounts

for almost one in five newly diagnosed cancer cases in the United

States (1). In the United States,

PCa is the most common cancer in men, and PCa-specific mortality

ranks second, after that of lung cancer (2). Although four well-established risk

factors have been identified, namely increased age, ethnicity,

obesity and family history, other potential factors that determine

the risk of developing PCa are not well known (3,4).

Histologically, most cases of PCa are classified as acinar

adenocarcinoma and have a poor prognosis (5).

There is increasing awareness that cancer metastasis

plays an important role in the survival of PCa patients. Treatment

decisions for PCa patients differ according to both patient- and

disease-related factors. Radical prostatectomy (RP) is the standard

treatment for clinically localized PCa, and it provides adequate

local control in organ-confined disease (6). Traditionally, RP is discouraged in

patients with advanced disease, owing to the increased complication

rate and treatment-related morbidity (7). In recent years, it has been suggested

that prostatectomy may provide a benefit for metastatic PCa

patients (8); however, for advanced

disease with site-specific metastasis of the bone, brain, liver or

lung, there is insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of

prostatectomy, particularly RP which includes including total

prostatectomy and cystoprostatectomy.

To the best of our knowledge, analyses of the

prognostic value of organ-specific metastasis based on large

population-based data for PCa are lacking. Thus, in the present

study, the data pertaining to metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma

patients registered in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End

Results (SEER) database was reviewed, and the prognostic outcomes

were analyzed to assess the efficacy of prostatectomy among

patients with bone metastasis only.

Materials and methods

Data collection/selection and

description of participants

The SEER-18 Regs Research Data released in November

2017 was retrieved using the SEER*Stat software version 8.3.5

(https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/software/) (National

Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health, USA). Detailed

information about distant metastatic sites was updated to 2013 and

was not available before the year 2010. Therefore, the current

study was restricted to patients registered between January 2010

and December 2013. The survival data of PCa patients was monitored

until December 2017. In order to identify patients with metastatic

prostate adenocarcinoma, cases were included with the primary site

stated as ‘Prostate’ and the following codes: ICD-O-3 Hist/behave,

malignant=‘8140/3: Adenocarcinoma, NOS’. Patients with stage I, II

and III PCa according to the 7th AJCC prostate cancer

classification criteria were excluded (9). Cases with unknown race data, unknown

marital status data, unknown survival data and unknown specific

metastatic site data were excluded. Only data from patients with

single primary PCa were extracted. Extracted data included the

following: Marital status at diagnosis, age at diagnosis, sex, race

(white, black or other), grade, TNM stage according to the AJCC

(7th edition, 2010), RX Summ-Surg Prim Site (surgical information

of primary cancer site), radiation sequence with surgery, CS mets

at DX-bone (bone metastases since 2010), CS mets at DX-brain (brain

metastases since 2010), CS mets at DX-liver (liver metastases since

2010), CS mets at DX-lung (lung metastases since 2010),

cancer-specific factor 1 (serum PSA levels), survival and vital

status record (10). At present,

systemic therapy data are not available in the SEER database.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients with unclear

derived M stage according to the AJCC (7th edition); ii) patients

with unclear RX Summ-Surg Prim Site (1998+); iii) patients

classified as clinical stage I/II or III prostate adenocarcinoma

according to the AJCC 7th edition.

Study variables

Patient characteristics were extracted from the SEER

database, including marital status, race, age at diagnosis, TNM

stage at diagnosis, primary tumor site, grade, surgery condition,

radiotherapy condition, bone metastasis, brain metastasis, liver

metastasis and lung metastasis. According to the AJCC 7th edition

criteria of TNM stage and clinical stage of prostate cancer, PCa

patients with T4, N0, M0 any T stage, N1, M0, and any T stage, any

N stage, M1 were classified as stage IV patients.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, the χ2 test was

used to compare the clinicopathological characteristics among cases

with and without bone metastasis. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to

build survival curves and log-rank testing was employed for the

comparison of long-term survival outcomes. The Cox proportional

hazards regression model was employed to perform univariate and

multivariate analyses of the hazard ratios with corresponding 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) of the study variates. Associations

between marital status, age at diagnosis, race, histological grade

and TNM stage at diagnosis were examined by binary logistic

regression. A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. All statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS software 20.0 (IBM

Corporation).

Results

Incidence of different metastatic

sites among stage IV PCa patients

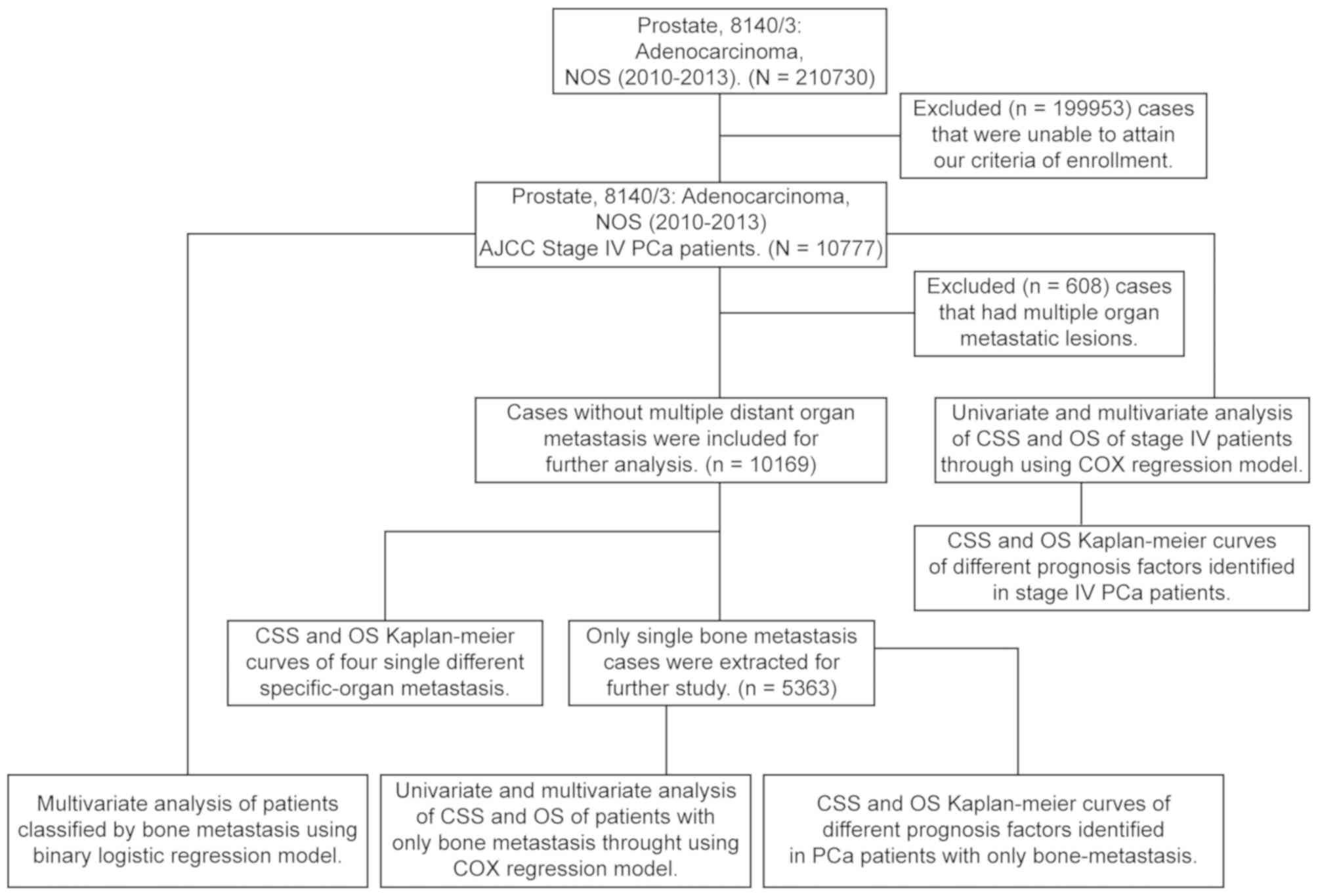

The selection criteria are shown in Fig. 1. Among 210,730 cases identified in

the SEER database, a total of 10,777 patients with stage IV

prostatic adenocarcinoma between January 2010 and December 2013

were included in the present study.

Table I summarizes

the distribution of different clinical characteristics of PCa

patients. The majority of patients (n=5,963, 55.33%) presented with

bone metastasis, followed by lung (n=512, 4.75%), liver (n=280,

2.60%) and brain (n=83, 0.77%) metastasis. Prostatectomy (RP,

including total prostatectomy and cystoprostatectomy) was performed

in 2,981 (27.66%) patients, and 1,085 (10.07%) patients received

radiation therapy. There were 4,258 (39.51%) patients with lymph

node metastasis.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of patients

with stage IV prostate adenocarcinoma (n=10,777) in the present

study. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of patients

with stage IV prostate adenocarcinoma (n=10,777) in the present

study.

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

<50 | 426 | 3.95 |

| ≥50 | 10,351 | 96.05 |

| Race |

|

|

|

White | 8,179 | 75.89 |

|

Black | 1,929 | 17.90 |

|

Othersa | 669 | 6.21 |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

Married | 6,941 | 64.41 |

|

Single/unmarried | 3,836 | 35.59 |

| Grade |

|

|

| I | 21 | 0.19 |

| II | 488 | 4.83 |

| III | 8,216 | 76.24 |

| IV | 81 | 0.75 |

|

Unknown | 1,971 | 18.29 |

| Bone

metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes | 5,963 | 55.33 |

| No | 4,814 | 44.67 |

| Brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes | 83 | 0.77 |

| No | 10,694 | 99.23 |

| Liver

metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes | 280 | 2.60 |

| No | 10,497 | 97.40 |

| Lung

metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes | 512 | 4.75 |

| No | 10,265 | 95.25 |

| Lymph node

metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes | 4,258 | 39.51 |

| No | 5,250 | 48.71 |

|

Unknown | 1,269 | 11.78 |

| Radiation

therapy |

|

|

|

Yes | 1,085 | 10.07 |

| No | 9,692 | 89.93 |

| Prostatectomy |

|

|

|

Yes | 2,981 | 27.66 |

| No | 7,761 | 72.01 |

|

Unknown | 35 | 0.32 |

Identification of statistically

significant variates with regard to survival outcomes in patients

with stage IV PCa

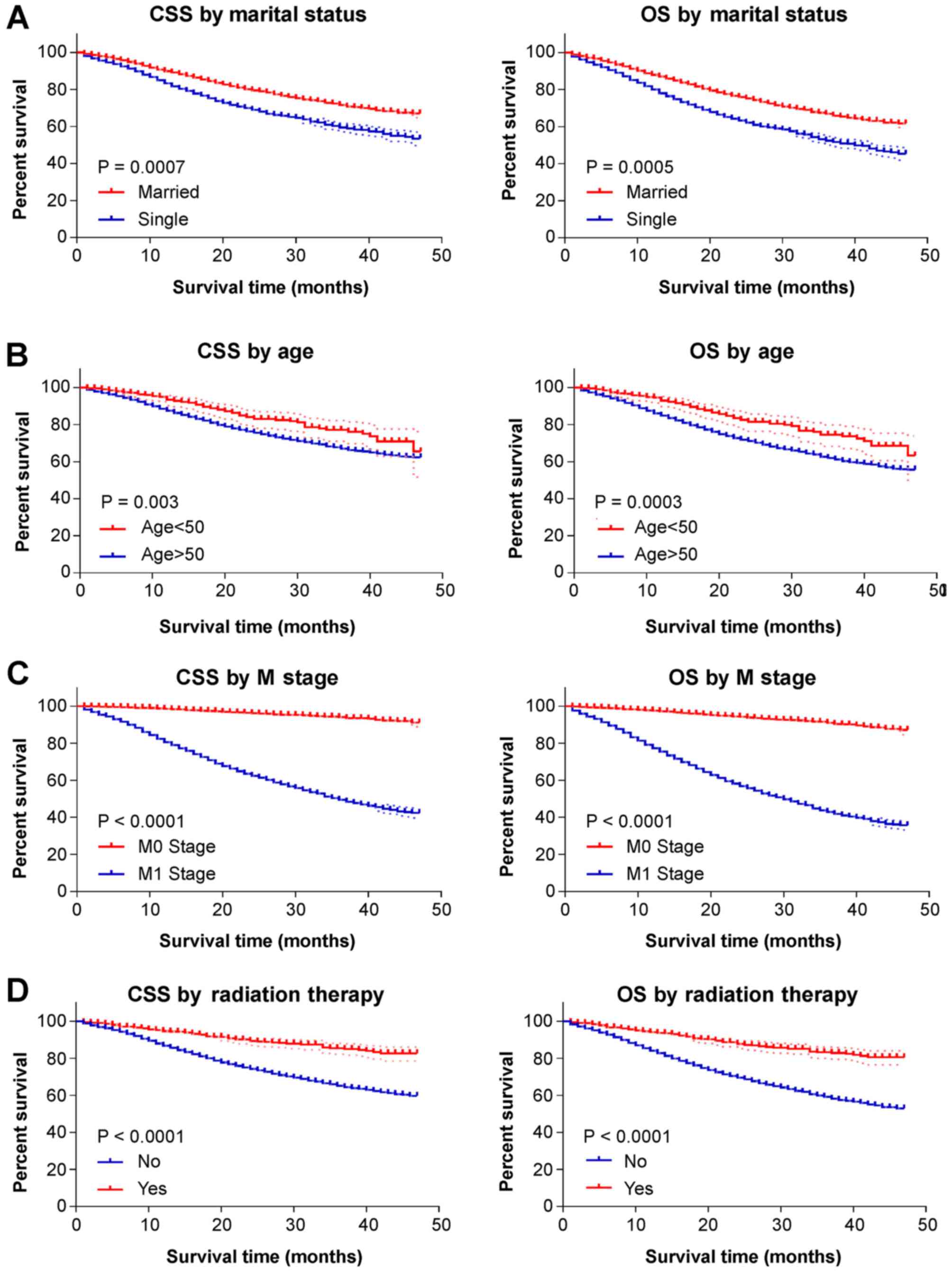

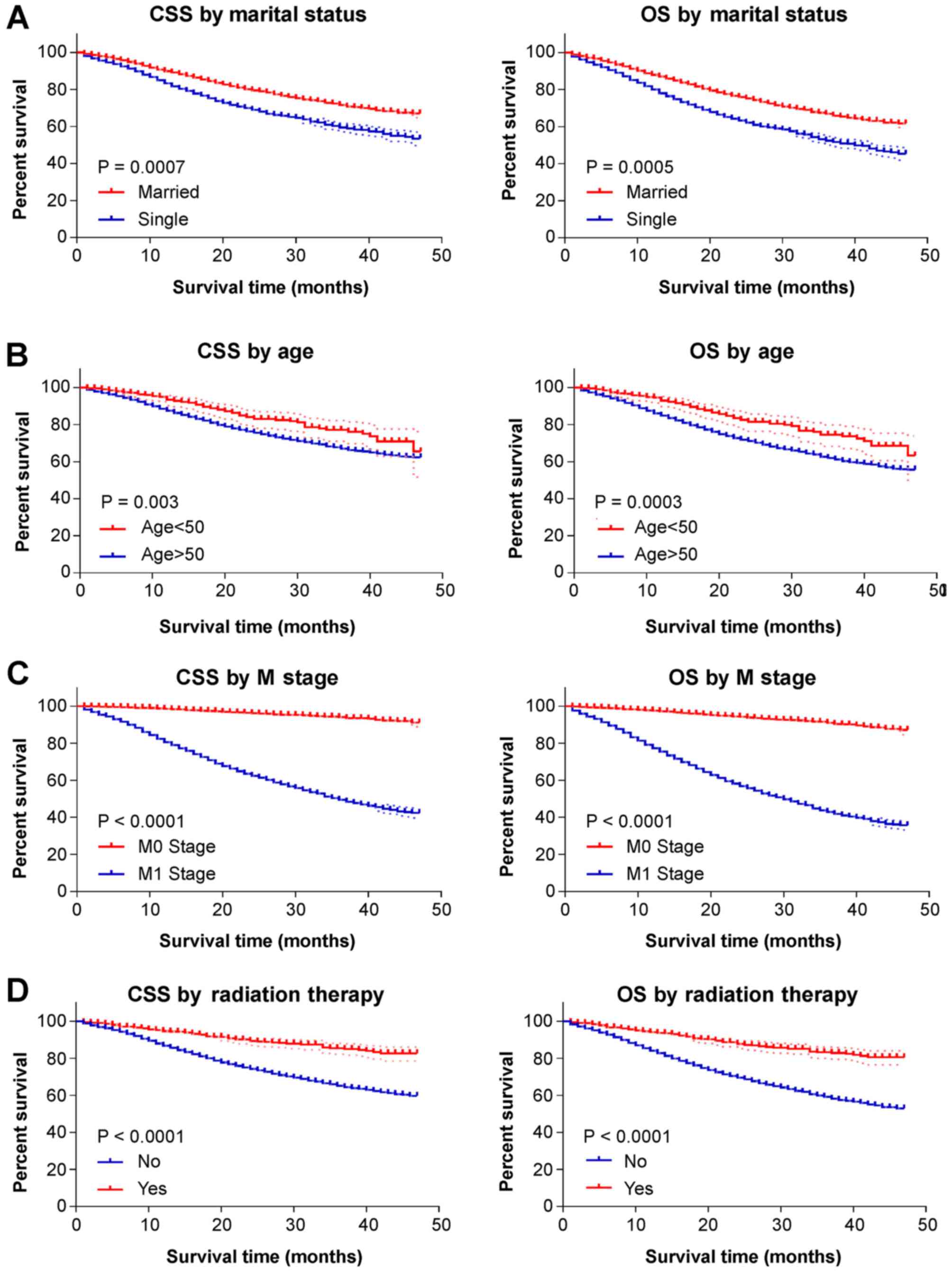

Several variates were identified by univariate and

multivariate analysis of cancer specific-survival (CSS) and overall

survival (OS) in PCa patients using Cox hazards regression models.

Single/unmarried status, age ≥50 years, black race, M1 stage, bone

metastasis, liver metastasis and lung metastasis were associated

with worse CSS and OS. Races classified as ‘other’ (American

Indian/Alaska native and Asian/Pacific Islander), radiation therapy

and prostatectomy were associated with better CSS and OS (Tables II and III). Based on multivariate Cox regression

analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with

poor OS and/or CSS: Single/unmarried status [hazard ratios (HRs),

1.164 (CSS) and 1.211 (OS), P<0.001], age ≥50 years [HRs, 1.309

(CSS), P=0.034 and 1.421 (OS), P=0.003], black race vs. white race;

[HR, 1.151 (CSS), P=0.009], M1 stage [HRs, 3.096 (CSS) and 2.419

(OS), P<0.001] and PSA level >20 ng/ml [HR, 1.27 (OS),

P=0.035]. On the other hand, ‘other’ race (American Indian/Alaska

native and Asian/Pacific Islander) was a significant predictor of

better CSS and OS (vs. white race; HRs, 0.750, P=0.005 and 0.774,

P=0.004, respectively), as was prostatectomy (HR, 0.147 and 0.143,

respectively, P<0.001). Radiation therapy was a significant

predictor of better OS only (HR, 0.756, P=0.003) (Table III). Next, Kaplan-Meier survival

analysis was performed to calculate the differences in OS and CSS

by the variates identified through multivariate Cox hazards

regression analysis (Fig. 2). The

3-year CSS rate of patients who received prostatectomy was 97.3%,

compared with 54.3% in patients who did not undergo prostatectomy

(P<0.0001). The 3-year OS rate of patients who received

prostatectomy was 96.0%, whereas that of patients who did not was

only 47.4% (P<0.001) (Fig. 2E).

Married status, age <50 years and radiation therapy also led to

higher 3-year CSS and OS rates (Fig. 2A,

B and D). By contrast, M1 stage, bone metastasis, liver

metastasis, lung metastasis and black race were associated with

reduced survival in stage IV PCa patients (Fig. 2C and F-I).

| Figure 2.Kaplan-Meier curves for CSS and OS by

different study variates. (A-D) The dotted lines reveal the 95%

confidence interval of each points on the Kaplan-Meier curve. The

marital status ‘single’ includes divorced, single (never married),

separated and widowed. Prostatectomy includes: Radical

prostatectomy, NOS; total prostatectomy, NOS; excised prostate,

prostatic capsule, ejaculatory ducts, seminal vesicle and including

a narrow cuff of bladder neck; Prostatectomy, NOS. CSS,

cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival; NOS, not otherwise

specified. Kaplan-Meier curves for CSS and OS by different study

variates. (E-I) The dotted lines reveal the 95% confidence interval

of each points on the Kaplan-Meier curve. The marital status

‘single’ includes divorced, single (never married), separated and

widowed. Prostatectomy includes: Radical prostatectomy, NOS; total

prostatectomy, NOS; excised prostate, prostatic capsule,

ejaculatory ducts, seminal vesicle and including a narrow cuff of

bladder neck; Prostatectomy, NOS. CSS, cancer-specific survival;

OS, overall survival; NOS, not otherwise specified. |

| Table II.Univariate analysis of CSS and OS in

10,777 patients with advanced prostate cancer. |

Table II.

Univariate analysis of CSS and OS in

10,777 patients with advanced prostate cancer.

|

| CSS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Single | <0.001 | 1.608 | 1.479 | 1.748 | <0.001 | 1.647 | 1.528 | 1.776 |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<50 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

≥50 | <0.001 | 1.620 | 1.263 | 2.077 | <0.001 | 1.775 | 1.404 | 2.243 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Black | 0.016 | 1.137 | 1.024 | 1.262 | 0.003 | 1.152 | 1.048 | 1.265 |

|

Othera | 0.005 | 0.754 | 0.618 | 0.920 | 0.01 | 0.795 | 0.667 | 0.947 |

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well

differentiated |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Moderately differentiated | 0.168 | 0.440 | 0.136 | 1.416 | 0.006 | 0.305 | 0.132 | 0.707 |

| Poorly

differentiated | 0.934 | 0.953 | 0.307 | 2.961 | 0.198 | 0.591 | 0.265 | 1.316 |

|

Undifferentiated | 0.144 | 2.418 | 0.740 | 7.897 | 0.486 | 1.360 | 0.573 | 3.228 |

| Tumor stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| T1 | <0.001 | 0.434 | 0.274 | 0.686 | 0.004 | 0.519 | 0.332 | 0.811 |

| T2 | <0.001 | 0.411 | 0.26 | 0.648 | 0.002 | 0.488 | 0.313 | 0.761 |

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.152 | 0.095 | 0.244 | <0.001 | 0.175 | 0.111 | 0.276 |

| T4 | <0.001 | 0.272 | 0.172 | 0.430 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.205 | 0.501 |

| Node stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| N1 | <0.001 | 0.627 | 0.569 | 0.692 | 0.340 | 0.956 | 0.872 | 1.048 |

| Metastasis

stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| M0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| M1 | <0.001 | 11.147 | 9.472 | 13.121 | <0.001 | 2.419 | 1.979 | 2.957 |

| Radiation

therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | <0.001 | 0.361 | 0.297 | 0.439 | <0.001 | 0.337 | 0.281 | 0.405 |

| Prostatectomy

surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | <0.001 | 0.041 | 0.031 | 0.055 | <0.001 | 0.049 | 0.038 | 0.0620 |

| PSA level,

ng/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤20 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

>20 | 0.056 | 1.241 | 0.994 | 1.569 | 0.019 | 1.271 | 1.032 | 1.565 |

| Distant lymph node

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.627 | 0.569 | 0.692 | <0.001 | 0.61 | 0.558 | 0.666 |

| Bone

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.167 | 0.149 | 0.188 | <0.001 | 0.192 | 0.173 | 0.212 |

| Brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.303 | 0.223 | 0.413 | <0.001 | 0.327 | 0.245 | 0.437 |

| Liver

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.233 | 0.197 | 0.276 | <0.001 | 0.256 | 0.219 | 0.300 |

| Lung

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.360 | 0.312 | 0.416 | <0.001 | 0.384 | 0.336 | 0.438 |

| Table III.Multivariate analysis of CSS and OS

in 10,777 patients with advanced prostate cancer. |

Table III.

Multivariate analysis of CSS and OS

in 10,777 patients with advanced prostate cancer.

|

| CSS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Single | <0.001 | 1.164 | 1.069 | 1.269 | <0.001 | 1.211 | 1.121 | 1.309 |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<50 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

≥50 | 0.034 | 1.309 | 1.021 | 1.682 | 0.003 | 1.421 | 1.124 | 1.798 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Black | 0.009 | 1.151 | 1.024 | 1.262 | 0.527 | 0.971 | 0.881 | 1.067 |

|

Othera | 0.005 | 0.750 | 0.618 | 0.921 | 0.004 | 0.774 | 0.649 | 0.922 |

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well

differentiated |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Moderately differentiated | 0.146 | 0.419 | 0.111 | 1.352 | 0.004 | 0.296 | 0.128 | 0.685 |

| Poor

differentiated | 0.653 | 0.771 | 0.248 | 2.397 | 0.084 | 0.493 | 0.221 | 1.101 |

|

Undifferentiated | 0.477 | 1.537 | 0.470 | 5.031 | 0.801 | 0.895 | 0.376 | 2.127 |

| Tumor stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| T1 | 0.065 | 0.643 | 0.402 | 1.028 | 0.266 | 0.773 | 0.491 | 1.217 |

| T2 | 0.072 | 0.653 | 0.410 | 1.039 | 0.279 | 0.780 | 0.497 | 1.224 |

| T3 | 0.071 | 0.641 | 0.396 | 1.037 | 0.179 | 0.727 | 0.456 | 1.158 |

| T4 | 0.742 | 1.081 | 0.678 | 1.725 | 0.358 | 1.236 | 0.786 | 1.944 |

| Node stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| N1 | 0.950 | 1.003 | 0.906 | 1.111 | 0.340 | 0.956 | 0.872 | 1.048 |

| Metastasis

stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| M0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| M1 | <0.001 | 3.096 | 2.443 | 3.923 | <0.001 | 2.419 | 1.979 | 2.957 |

| Radiation

therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 0.066 | 0.829 | 0.679 | 1.012 | 0.003 | 0.756 | 0.628 | 0.911 |

| Prostatectomy

surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | <0.001 | 0.147 | 0.105 | 0.206 | <0.001 | 0.143 | 0.108 | 0.189 |

| PSA level,

ng/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤20 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

>20 | 0.069 | 1.236 | 0.984 | 1.553 | 0.035 | 1.251 | 1.016 | 1.541 |

| Distant lymph node

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | 0.722 | 1.019 | 0.92 | 1.128 | 0.384 | 0.96 | 0.875 | 1.053 |

| Bone

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.739 | 0.633 | 0.863 | <0.001 | 0.775 | 0.674 | 0.891 |

| Brain

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | 0.115 | 0.774 | 0.562 | 1.064 | 0.102 | 0.779 | 0.579 | 1.049 |

| Liver

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.472 | 0.396 | 0.563 | <0.001 | 0.501 | 0.424 | 0.589 |

| Lung

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| No | <0.001 | 0.776 | 0.667 | 0.902 | 0.001 | 0.794 | 0.691 | 0.912 |

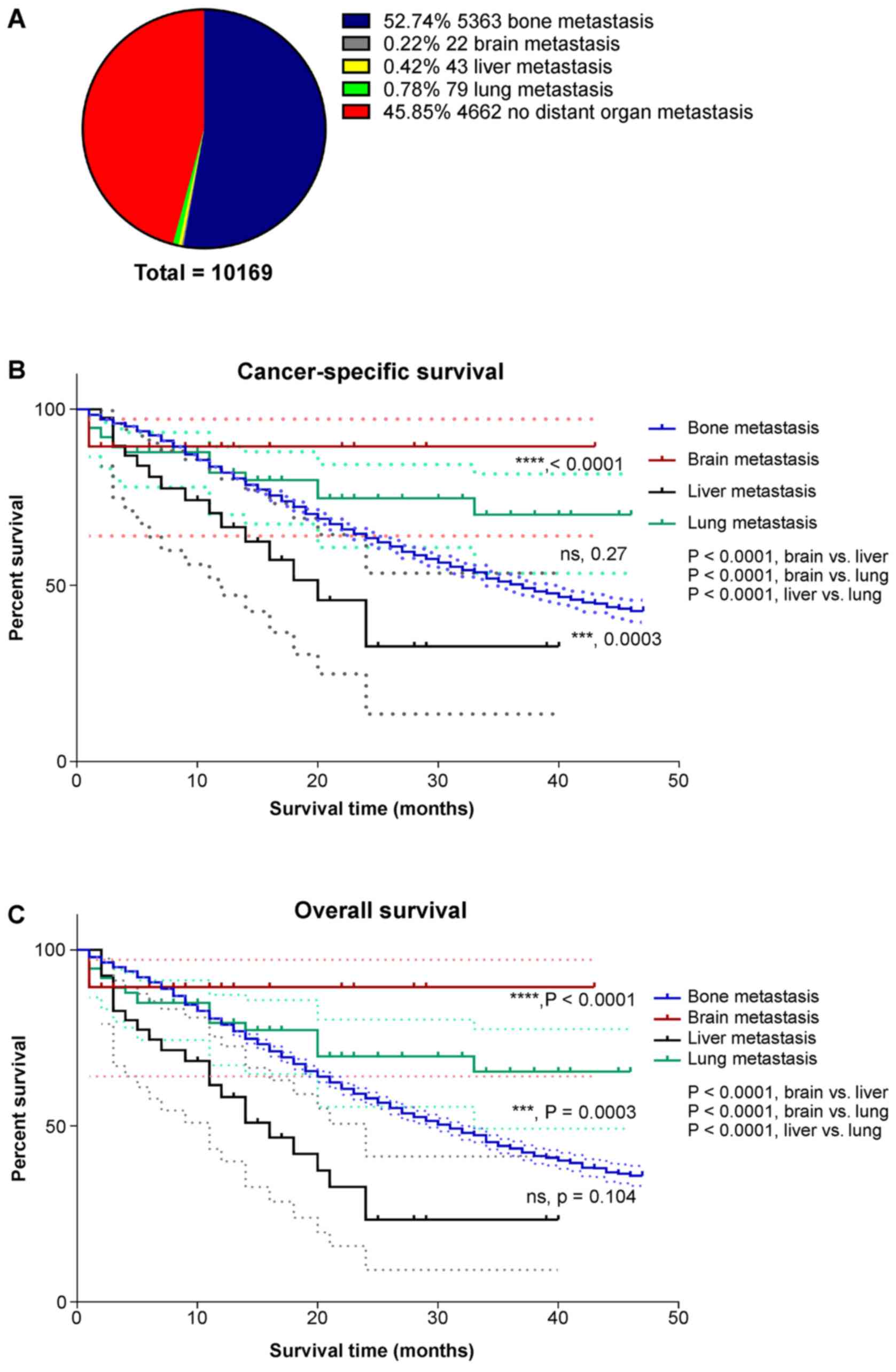

Impact of site-specific metastasis on

survival outcomes

As it was found that metastasis to different organs

may induce different survival outcomes in stage IV PCa patients,

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to compare OS in

advanced PCa patients with metastasis to the bone, brain, liver and

lung. A total of 608 patients with metastatic lesions in multiple

organs were excluded, and 10,169 patients were included in the

analysis. Of these patients, 52.74% had bone metastasis, 0.22% had

brain metastasis, 0.42% had liver metastasis, and 0.78% had lung

metastasis (Fig. 3A). It was

demonstrated that PCa patients with only liver metastasis had the

worst 3-year CSS and OS rates (31.9 and 22.8%, respectively). The

3-year CSS and OS rates of patients with only bone metastasis were

49.6 and 41.6%, respectively. Patients with only lung metastasis

(3-year CSS and OS, 79.9 and 63.7%) had improved OS compared with

those with only bone or liver metastasis (Fig. 3B and C).

Identification of risk factors for

bone metastasis in patients with stage IV PCa

As the present results indicated that stage IV PCa

was most prone to distant metastasis to the bone, multivariate

binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk

factors of bone metastasis in 10,777 patients with advanced PCa.

The results suggested that single/unmarried status, black race, NX

stage and grade IV (undifferentiated adenocarcinoma) were risk

factors for bone metastasis. T3 and T4 stage patients, as well as

N1 stage patients, were less likely to have bone metastasis

(Table IV).

| Table IV.Multivariate binary logistic

regression analysis of patient characteristics classified by bone

metastasis at diagnosis (n=10,777). |

Table IV.

Multivariate binary logistic

regression analysis of patient characteristics classified by bone

metastasis at diagnosis (n=10,777).

|

| Bone

metastasis |

| Multivariate

analysis |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | No | Yes | Pearson

χ2 P-value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Total patients | 4,814 (44.7) | 5,963 (55.3) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Marital status |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

Married | 3,457 (49.8) | 3,484 (50.2) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

Single | 1,357 (35.4) | 2,479 (64.6) |

| 1.671 | 1.505 | 1.856 | <0.001 |

| Age, years |

|

| 0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

<50 | 224 (52.6) | 202 (47.4) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

≥50 | 4,590 (44.3) | 5761 (55.7) |

| 1.044 | 0.818 | 1.334 | 0.729 |

| Race |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

White | 3,783 (46.3) | 4396 (53.7) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

Black | 735 (38.1) | 1194 (61.9) |

| 1.155 | 1.013 | 1.317 | 0.032 |

|

Othera | 296 (44.2) | 373 (55.8) |

| 1.093 | 0.893 | 1.338 | 0.387 |

| Grade |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| Well

differentiated | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

Moderately differentiated | 306 (62.7) | 182 (37.3) |

| 0.488 | 0.168 | 1.411 | 0.907 |

| Poorly

differentiated | 4,122 (50.2) | 4094 (49.8) |

| 1.064 | 0.376 | 3.01 | 0.581 |

|

Undifferentiated | 32 (39.5) | 49 (60.5) |

| 1.391 | 1.01 | 8.26 | 0.048 |

|

Unknown | 344 (17.5) | 1627 (82.5) |

| 4.301 | 1.812 | 10.204 | <0.001 |

| Tumor stage |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| T0 | 10 (18.9) | 43 (81.1) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

| T1 | 422 (21.4) | 1,550 (78.6) |

| 1.11 | 0.523 | 2.357 | 0.758 |

| T2 | 750 (29.4) | 1,804 (70.6) |

| 0.815 | 0.385 | 1.723 | 0.59 |

| T3 | 1,445 (72.5) | 548 (27.5) |

| 0.211 | 0.1 | 0.448 | <0.001 |

| T4 | 1,996 (73.9) | 705 (26.1) |

| 0.069 | 0.033 | 0.146 | <0.001 |

| TX | 191 (12.7) | 1313 (87.3) |

| 1.499 | 0.790 | 3.233 | 0.192 |

| Node stage |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| N0 | 1,817 (34.6) | 3,433 (65.4) |

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

| N1 | 2,868 (67.4) | 1,390 (32.6) |

| 0.166 | 0.148 | 0.186 | <0.001 |

| NX | 129 (10.2) | 1,140 (89.8) |

| 2.342 | 1.882 | 2.914 | <0.001 |

Identification of ‘risk’ factors and

‘protective’ factors for CSS and OS in patients with advanced PCa

with only bone metastasis

Univariate and multivariate COX hazards regression

analyses were conducted in 5,363 patients with stage IV PCa with

only bone metastasis to identify the contribution of different

variates to CSS and OS. According to the results, single/unmarried

status was deemed as risk factor for CSS and OS; age ≥50 years was

deemed as risk factor for OS (Tables

V and VI). On the other hand,

‘other’ race (American Indian/Alaska native and Asian/Pacific

Islander), T1 stage, T3 stage and prostatectomy were regarded as

‘protective’ factors in stage IV patients with only bone

metastasis, moreover, T2 stage was additionally regarded as a

‘protective’ factor for CSS in stage IV PCa patients but not OS

(Tables V and VI).

| Table V.Univariate COX analysis of CSS and OS

in patients with advanced prostate cancer and only bone

metastasis. |

Table V.

Univariate COX analysis of CSS and OS

in patients with advanced prostate cancer and only bone

metastasis.

|

| CSS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Single | <0.001 | 1.244 | 1.128 | 1.373 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.182 | 1.410 |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<50 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

≥50 | 0.089 | 1.277 | 0.963 | 1.692 | 0.016 | 1.386 | 1.062 | 1.808 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Black | 0.779 | 1.018 | 0.901 | 1.15 | 0.551 | 1.034 | 0.926 | 1.155 |

|

Othersa | 0.001 | 0.675 | 0.532 | 0.856 | 0.003 | 0.731 | 0.593 | 0.9 |

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well

differentiated |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Moderately differentiated | 0.228 | 0.410 | 0.096 | 1.746 | 0.027 | 0.310 | 0.110 | 0.876 |

| Poorly

differentiated | 0.889 | 1.103 | 0.276 | 4.419 | 0.427 | 0.672 | 0.252 | 1.793 |

|

Undifferentiated | 0.465 | 1.727 | 0.399 | 7.477 | 0.878 | 0.918 | 0.311 | 2.714 |

| Tumor stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| T1 | <0.001 | 0.332 | 0.194 | 0.566 | <0.001 | 0.393 | 0.235 | 0.657 |

| T2 | <0.001 | 0.374 | 0.219 | 0.636 | 0.002 |

| 0.262 | 0.730 |

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.320 | 0.184 | 0.556 | <0.001 | 0.357 | 0.210 | 0.608 |

| T4 | 0.052 | 0.585 | 0.341 | 1.004 | 0.076 |

| 0.371 | 1.051 |

| Node stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| N1 | 0.004 | 1.196 | 1.059 | 1.351 | 0.086 | 1.103 | 0.986 | 1.234 |

| Radiation

therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 0.918 | 0.987 | 0.772 | 1.263 | 0.725 | 0.960 | 0.765 | 1.204 |

| Prostatectomy

surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | <0.001 | 0.216 | 0.103 | 0.454 | <0.001 | 0.255 | 0.137 | 0.475 |

| Table VI.Multivariate COX analysis of CSS and

OS in patients with stage IV prostate cancer with only bone

metastasis. |

Table VI.

Multivariate COX analysis of CSS and

OS in patients with stage IV prostate cancer with only bone

metastasis.

|

| CSS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Single | 0.002 | 1.172 | 1.058 | 1.293 | <0.001 | 1.221 | 1.114 | 1.336 |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<50 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

≥50 | 0.104 | 1.265 | 0.953 | 1.678 | 0.025 | 1.357 | 1.039 | 1.772 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Black | 0.909 | 0.993 | 0.877 | 1.124 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.893 | 1.118 |

|

Othera | 0.002 | 0.685 | 0.540 | 0.869 | 0.006 | 0.746 | 0.605 | 0.919 |

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well

differentiated |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Moderately differentiated | 0.171 | 0.363 | 0.085 | 1.546 | 0.016 | 0.279 | 0.099 | 0.791 |

| Poorly

differentiated | 0.933 | 0.942 | 0.235 | 3.781 | 0.295 | 0.591 | 0.221 | 1.581 |

|

Undifferentiated | 0.599 | 1.483 | 0.342 | 6.438 | 0.736 | 0.829 | 0.280 | 2.459 |

| T stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| T1 | 0.011 | 0.495 | 0.287 | 0.854 | 0.044 | 0.584 | 0.346 | 0.986 |

| T2 | 0.019 | 0.523 | 0.305 | 0.897 | 0.063 | 0.611 | 0.363 | 1.027 |

| T3 | 0.011 | 0.480 | 0.273 | 0.844 | 0.025 | 0.539 | 0.314 | 0.926 |

| T4 | 0.349 | 0.771 | 0.445 | 1.331 | 0.493 | 0.831 | 0.491 | 1.409 |

| N stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

| N1 | 0.099 | 1.111 | 0.98 | 1.258 | 0.498 | 1.041 | 0.928 | 1.167 |

| Radiation

therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 0.641 | 0.942 | 0.735 | 1.209 | 0.484 | 0.922 | 0.733 | 1.159 |

| Prostatectomy

surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

| 1.000 |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 0.001 | 0.291 | 0.138 | 0.614 | 0.001 | 0.346 | 0.185 | 0.648 |

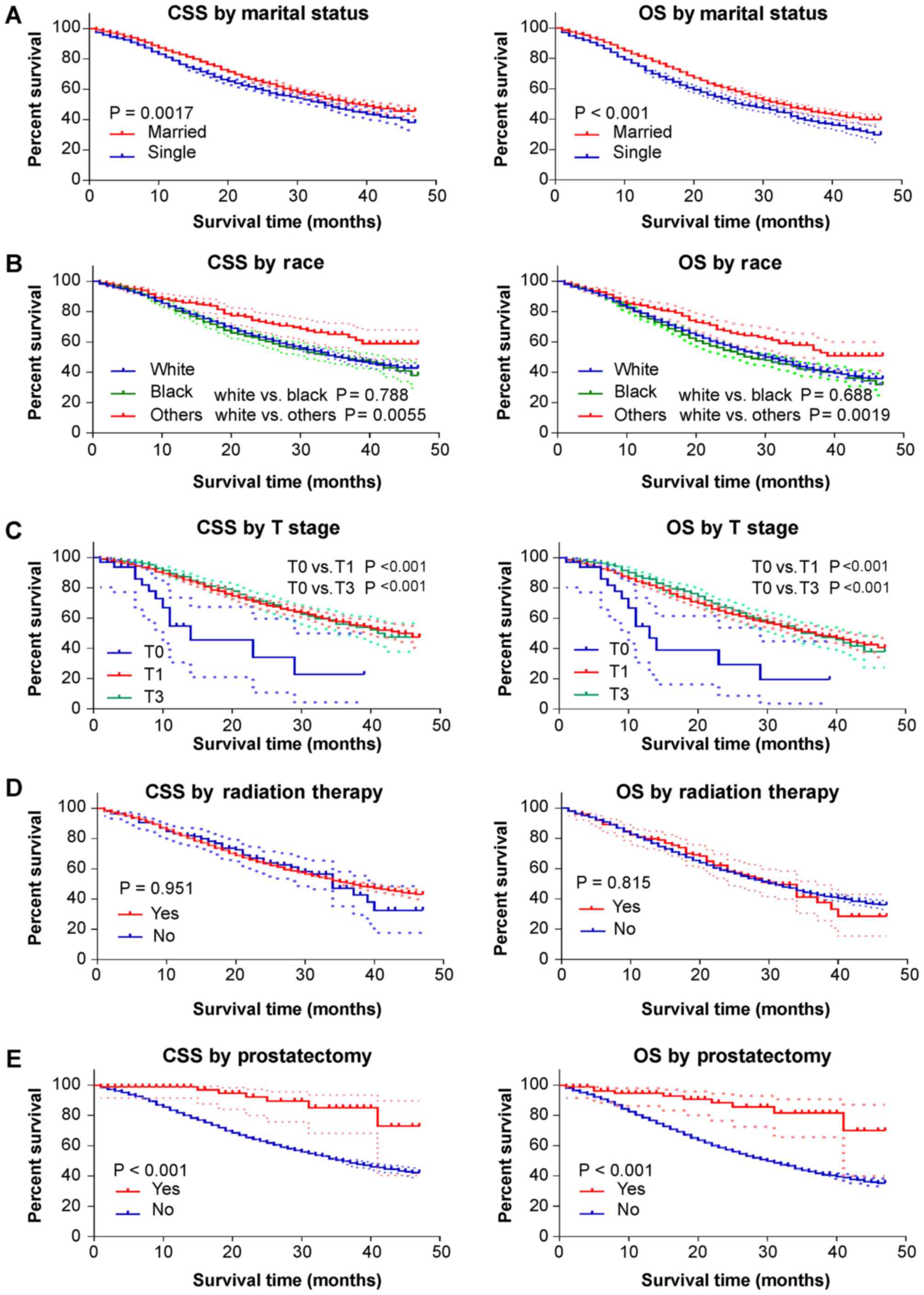

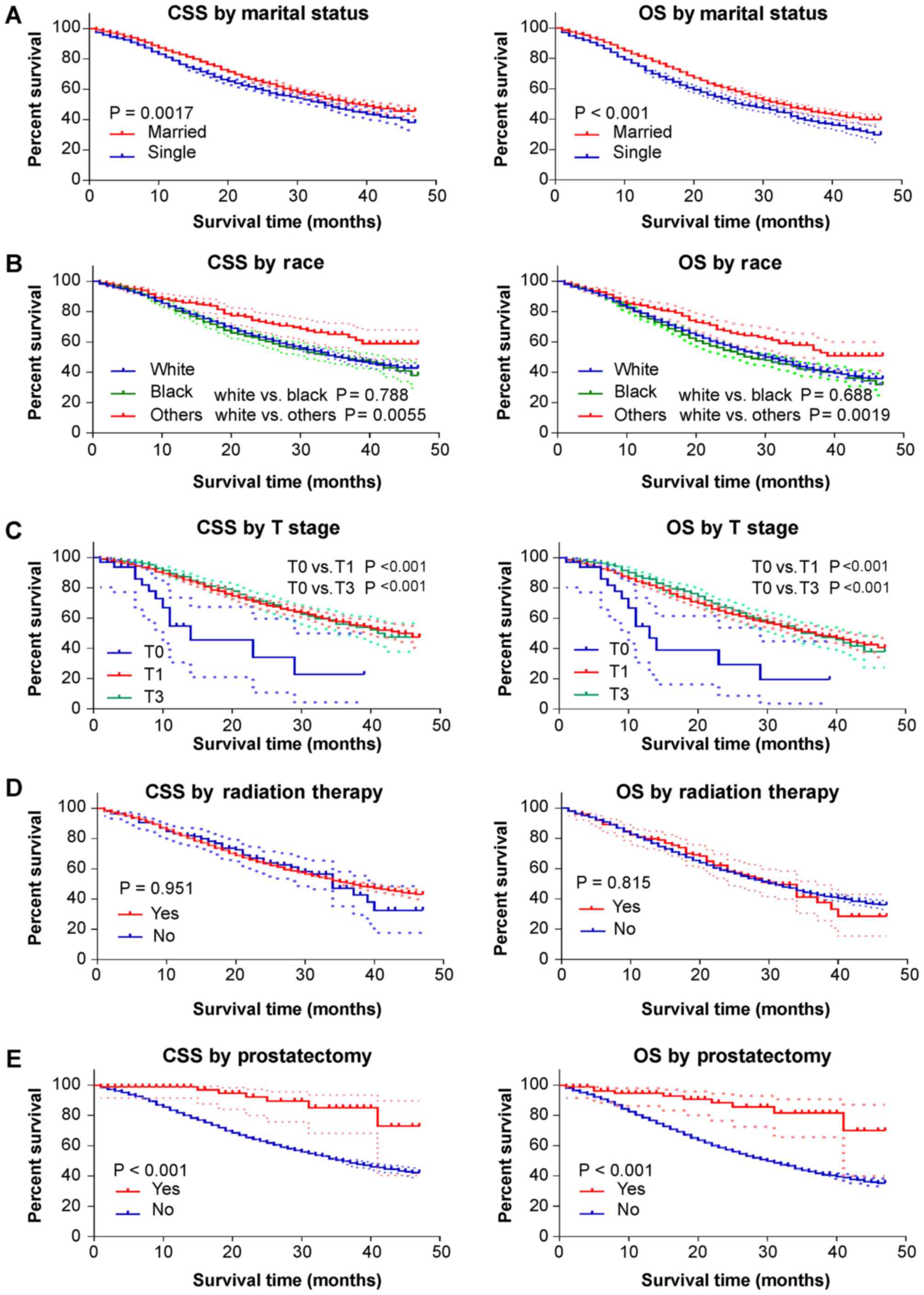

Prostatectomy is effective in

improving survival outcomes in patients with advanced PCa with only

bone metastasis

Kaplan-Meier analysis was conducted using

significant factors from Cox regression analysis to determine their

impact on survival in patients with stage IV PCa with only bone

metastasis. According to the results, married patients had better

3-year survival rates than single/unmarried patients (CSS, 51.9 vs.

46.2%; OS, 45.6 vs. 38.5%; Fig. 4A).

‘Other’ race patients (American Indian/Alaska native and

Asian/Pacific Islander) also had better CSS and OS than white

patients (Fig. 4B). T1 and T3 stage

patients had better CSS and OS than T0 stage patients, although

this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 4C). Radiation therapy did not

significantly improve patient's survival (Fig. 4D). Moreover, it was found that

prostatectomy could potently improve the 3-year CSS and OS rates

(vs. no prostatectomy; CSS, 85.1 vs. 49.0%; OS, 81.5 vs. 42.1%;

Fig. 4E). The HR of CSS in patients

with T2 stage bone metastases was 0.523; suggesting that patients

with stage T2 cancer had improved specific survival outcomes

compared with T0 patients (Table

VI). However, as the effect of T2 stage did not significantly

affect OS, it is possible that T2 stage would be a protective

factor for survival outcomes in single bone metastasis PCa

patients.

| Figure 4.Kaplan-Meier curves for CSS and OS by

different study variates. The dotted lines indicate the 95%

confidence interval of each point on the Kaplan-Meier curve. The

marital status ‘single’ includes divorced, single (never married),

separated and widowed. ‘Others’ race includes American

Indian/Alaska native and Asian/Pacific Islander. Prostatectomy

includes: Radical prostatectomy, NOS; total prostatectomy, NOS;

Excised prostate, prostatic capsule, ejaculatory ducts, seminal

vesicle and including a narrow cuff of bladder neck; Prostatectomy,

NOS. NOS, no other specification; CSS, cancer-specific survival;

OS, overall survival. |

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were: i)

Prostate adenocarcinoma patients with only liver metastasis had

worse prognostic outcomes than those with only bone or only lung

metastasis; ii) prostatectomy potently improved the CSS and OS of

stage IV PCa patients with only bone metastasis; and iii) unmarried

status, age ≥50 years, M1 stage, bone metastasis, liver metastasis

and lung metastasis were risk factors for survival in patients with

stage IV PCa.

The Cox regression model is widely used in survival

analysis with censoring data and different covariates (11). When analyzing survival data of the

patients, the HR generated by Cox regression model represents the

probability of death at a particular time. The Kaplan-Meier curve

can efficiently use all data, including the censored data, to

estimate the time-to-event curve. Comparisons of different groups

is assessed by log-rank test, which is able to estimate the

long-term prognosis of patients (11). Therefore, survival analysis of stage

IV PCa patients and single bone metastasis advanced PCa patients

was performed using the Cox regression model and Kaplan-Meier

analysis methods.

Using COX regression models, M1 stage, bone

metastasis, liver metastasis and lung metastasis were first

identified to be significantly associated with impaired CSS and OS

(Tables II and III) among stage IV PCa patients.

Radiation therapy and prostatectomy were also identified to be

effective therapeutic methods to improve patient CSS and OS in

advanced PCa.

The bone was revealed to be the most common

metastatic site for stage IV PCa, and patients with bone metastases

had significantly impaired CSS and OS rates. Therefore, it was

necessary to find risk factors that were associated with bone

metastasis in stage IV PCa. Multivariate binary logistic regression

analysis suggested that single/unmarried patients, black patients

and patients with grade IV (undifferentiated adenocarcinoma) were

more likely to have bone metastasis (Table VI). However, T3 stage, T4 stage and

N1 stage were ‘protective’ factors. One possible explanation for

this result is that certain groups of patients were included that

were diagnosed as having stage IV PCa according to the AJCC 7th

edition, but did not have metastatic disease: Patients with i) any

T stage, N1, M0; ii) T4,any N stage, M0; and iii) T3, N1, M0.

As bone metastasis may potently impair survival

outcomes for patients with stage IV PCa, finding effective

treatment methods to improve the CSS and OS of patients with bone

metastasis is necessary. Historically, RP has not been recommended

for patients with advanced PCa presumed to have extra-prostatic

disease; instead, patients with advanced PCa were counseled to

undergo radiation therapy or hormonal therapy (12). However, local resection of the

primary site for metastatic solid tumors has been demonstrated to

be helpful in various cancer types, including metastatic renal cell

carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer and

metastatic breast cancer (13–21).

Culp et al (8) demonstrated

that metastatic PCa patients undergoing definitive local treatment

had higher 5-year OS and CSS rates than those not undergoing local

therapy. For patients with PCa, there is still no consensus about

the benefit of primary site surgery in the presence of metastatic

disease. The current findings demonstrate that, for patients with

bone metastasis, prostatectomy may significantly improve both CSS

and OS (Fig. 4). Although radiation

therapy provided obvious improvements in both CSS and OS in stage

IV PCa patients (Fig. 2), the

present results indicated that there was no significant improvement

in CSS and OS with the administration of radiation therapy to

patients with only bone metastasis (Fig.

4).

Mechanisms underlying the survival benefit of

primary tumor resection remain unknown. According to the

‘self-seeding’ hypothesis, cancer cells may seed distant sites, as

well as the primary tumor site (22,23).

Eliminating the primary source of the metastatic tumor cells by

removing the prostate may reduce the number of circulating tumor

cells (24). Therefore, it is

reasonable to believe that prostatectomy may be beneficial for

patients with metastatic PCa.

Cooperberg et al (25) showed that PCa patients aged ≥50 years

may show higher CAPRA scores (the CAPRA score was developed using

the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor

registry data) (26), implying that

older age increases the risk of metastasis in PCa patients.

Similarly, in the present study, it was demonstrated that age ≥50

years was a risk factor for both CSS and OS in patients with only

bone metastasis (Tables V and

VI). The current study also

revealed that patients with grade IV PCa (undifferentiated) had a

higher risk of bone metastases than grade I patients (Table IV). Moreover, Brawley et al

(27) suggested that mortality rates

for patients with PCa are higher for black Americans than for white

Americans. The findings of the current study also suggested that

black patients with stage IV PCa had worse CSS and OS compared with

white patients (Fig. 2). A recent

study by Guo et al (28)

suggested that liver, lung or brain metastasis resulted in a poorer

prognosis in prostate cancer patients diagnosed with bone

metastasis (28). By contrast, the

present study assessed the effects of four specific single

metastasis sites on the survival of patients with advanced PCa.

Moreover, prostatectomy was identified as an effective treatment

for PCa patients with single bone metastases instead of radiation

therapy.

Analysis of the association between disease

prognosis and metastatic site may help in optimizing disease

management and devising systemic therapy strategies for PCa. The

current findings suggested that patients with only liver metastasis

had worse CSS and OS rates compared with those with only bone or

liver metastasis (Fig. 3).

The following limitations of the present study

should be considered. First, information about smoking, obesity,

Gleason scores and other risk factors for PCa were not registered

in the SEER database. The current analysis only evaluated

prostatectomy (RP; total prostatectomy and cystoprostatectomy were

included) for metastatic PCa patients, but specific surgical

information was not included (e.g., the use of laparoscopic or

robotic-assisted surgeries). Resection of metastatic lesions can

also affect the survival outcomes of patients with metastatic PCa,

but such information cannot be retrieved from the SEER database. In

addition, information on androgen deprivation therapy and

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, are not included. The dataset used was

representative only of the United States, so the applicability of

the results to a wider population is uncertain. As the current

study was based on patient data from 2010-2013, 5-year survival

rate, which is deemed as an effective indicator for predicting the

long-term prognosis of patients, was not available. Instead, 3-year

survival rate was used as an indicator to estimate the prognosis of

patients with advanced PCa. Studies based on updated SEER PCa data

that include >5 years of records of ‘specific site metastases’

can provide 5 year-survival rate, as a long-term prognosis

indicator, to further validate the current results. Although the

prognosis of PCa patients can be changed with improvements of

treatment, we still hypothesize that prostatectomy is beneficial

for prognosis outcomes of patients with stage IV PCa.

In conclusion, based on the results of SEER

analysis, patients with advanced prostatic adenocarcinoma with only

liver metastasis have worse outcomes than those with only bone or

lung metastasis. Despite the limitations of the SEER database, the

current results suggest that prostatectomy confers a survival

advantage in PCa patients with only bone metastasis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported in part by funding from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81772183

and 5177030177).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the

current study are available in the SEER repository (https://seer.cancer.gov/).

Authors' contributions

YD, RB and CW designed the study. YD and ZZ

extracted the data. ZZ, BX, SL and WAR assisted with the data

processing and statistical analysis. YD and WAR wrote the article.

CW funded the study. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:7–30. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yamada Y, Naruse K, Nakamura K, Taki T,

Tobiume M, Zennami K, Nishikawa G, Itoh Y, Muramatsu Y, Nanaura H,

et al: Investigation of risk factors for prostate cancer patients

with bone metastasis based on clinical data. Exp Ther Med.

1:635–639. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau

S, Mason M, Matveev V, Mottet N, Schmid HP, van der Kwast T, Wiegel

T, et al: EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: Screening,

diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol.

59:61–71. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang L, Drake BF and Colditz GA: Obesity

and other cancers. J Clin Oncol. 34:4231–4237. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Humphrey PA: Histopathology of prostate

cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 7:a0304112017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Filén F, Ruutu

M, Garmo H, Busch C, Nordling S, Häggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell

S, et al: Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in

localized prostate cancer: The Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4

randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 100:1144–1154. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Veeratterapillay R, Goonewardene SS,

Barclay J, Persad R and Bach C: Radical prostatectomy for locally

advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl.

99:259–264. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Culp SH, Schellhammer PF and Williams MB:

Might men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer benefit from

definitive treatment of the primary tumor? A SEER-based study. Eur

Urol. 65:1058–1066. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Stephen B, David R, Carolyn C and April G:

AJCC cancer staging manual seventh edition. Am Joint Committee

Cancer. 2010, https://cancerstaging.org/references-tools/deskreferences/Pages/default.aspxAugust

29–2017

|

|

10

|

Adamo M, Dickie L and Ruhl J: SEER program

coding and staging manual 2016. National Cancer Institute;

Bethesda, MD 20850-9765, U.S.: Department of Health and Human

Services National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute, .

2016, https://seer.cancer.gov/tools/codingmanuals/historical.htmlAugust

29–2017

|

|

11

|

Fisher LD and Lin DY: Time-dependent

covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu

Rev Public Health. 20:145–157. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Freedland SJ, Partin AW, Humphreys EB,

Mangold LA and Walsh PC: Radical prostatectomy for clinical stage

T3a disease. Cancer. 109:1273–1278. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B,

Lee JL, Knox JJ, Bjarnason GA, Pal SK, Kollmannsberger CK, Yuasa T,

et al: Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous

metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Results from the

international metastatic renal cell carcinoma database consortium.

Eur Urol. 66:704–710. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Keutgen XM, Nilubol N, Glanville J,

Sadowski SM, Liewehr DJ, Venzon DJ, Steinberg SM and Kebebew E:

Resection of primary tumor site is associated with prolonged

survival in metastatic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors. Surgery. 159:311–318. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hüttner FJ, Schneider L, Tarantino I,

Warschkow R, Schmied BM, Hackert T, Diener MK, Büchler MW and

Ulrich A: Palliative resection of the primary tumor in 442

metastasized neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: A

population-based, propensity score-matched survival analysis.

Langenbecks Arch Surg. 400:715–723. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Abdel-Rahman O: Role of liver-directed

local tumor therapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma

with extrahepatic metastases: A SEER database analysis. Expert Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11:183–189. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Abou-Alfa GK and Venook AP: The impact of

new data in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

Curr Oncol Rep. 10:199–205. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Oweira H, Petrausch U, Helbling D, Schmidt

J, Mannhart M, Mehrabi A, Schöb O, Giryes A, Decker M and

Abdel-Rahman O: Prognostic value of site-specific metastases in

pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A surveillance epidemiology and end

results database analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 23:1872–1880.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shien T, Nakamura K, Shibata T, Kinoshita

T, Aogi K, Fujisawa T, Masuda N, Inoue K, Fukuda H and Iwata H: A

randomized controlled trial comparing primary tumour resection plus

systemic therapy with systemic therapy alone in metastatic breast

cancer (PRIM-BC): Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1017. Jpn

J Clin Oncol. 42:970–973. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ruiterkamp J, Voogd AC, Tjan-Heijnen VC,

Bosscha K, van der Linden YM, Rutgers EJ, Boven E, van der Sangen

MJ and Ernst MF; Dutch Breast Cancer Trialists' Group (BOOG), :

SUBMIT: Systemic therapy with or without up front surgery of the

primary tumor in breast cancer patients with distant metastases at

initial presentation. BMC Surg. 12:52012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fields RC, Jeffe DB, Trinkaus K, Zhang Q,

Arthur C, Aft R, Dietz JR, Eberlein TJ, Gillanders WE and

Margenthaler JA: Surgical resection of the primary tumor is

associated with increased long-term survival in patients with stage

IV breast cancer after controlling for site of metastasis. Ann Surg

Oncol. 14:3345–3351. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Comen E, Norton L and Massagué J: Clinical

implications of cancer self-seeding. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 8:369–377.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Norton L: Cancer stem cells, self-seeding,

and decremented exponential growth: Theoretical and clinical

implications. Breast Dis. 29:27–36. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Resel Folkersma L, San José Manso L,

Galante Romo I, Moreno Sierra J and Olivier Gómez C: Prognostic

significance of circulating tumor cell count in patients with

metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Urology.

80:1328–1332. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Cooperberg MR, Broering JM and Carroll PR:

Risk assessment for prostate cancer metastasis and mortality at the

time of diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 101:878–887. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cook MM, Rosenberg PS, McCarty FA, Wu M,

King J, Eheman C and Anderson WF: Racial disparities in prostate

cancer incidence rates by census division in the United States,

1999–2008. Prostate. 75:758–763. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Brawley OW, Jani AB and Master V: Prostate

cancer and race. Curr Probl Cancer. 31:211–225. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Guo X, Zhang C, Guo Q, Xu Y, Feng G, Li L,

Han X, Lu F, Ma Y, Wang X and Wang G: The homogeneous and

heterogeneous risk factors for the morbidity and prognosis of bone

metastasis in patients with prostate cancer. Cancer Manag Res.

10:1639–1646. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|