Introduction

Gliomas represent a serious clinical disease, with

high malignancy, common recurrence and poor prognosis. According to

statistics, in 2015, the prevalence of gliomas accounts for 4–5% in

the world (1,2). At present, the standard treatment is to

remove the tumor to the maximum extent using radiotherapy and

chemotherapy (3,4), but the 5-year survival rate is <5%

worldwide (5). Glioblastoma (GBM) is

one of the most malignant, recurrent and invasive tumor types, and

is classified as grade 4 according to the World Health Organization

nervous system tumor classification system (6). GBM is insidious and invasive, and its

clinical symptoms appear relatively late (7). Microsurgical resection, postoperative

chemotherapy and radiotherapy are the primary techniques to treat

GBM (7). Due to limitations of the

anatomical structure, highly invasive growth and high radiation

resistance, no marked positive effect on the overall prognosis of

patients has been achieved, despite numerous advances in treatment

methods in recent years (7). Novel

treatment strategies and drug research and development have become

increasingly urgent as this problem remains to be solved (8,9).

With the rapid development of high-throughput

sequencing and bioinformatics in recent years, some key biomarkers

and signaling pathways in the development of GBM have been

identified, providing a theoretical basis for the study of

GBM-targeting drugs (10). The

PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway is a key regulator of numerous

cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis,

migration and invasion (11). It is

one of the most commonly altered signal transduction networks in

human cancer (11). The PI3K family

of lipid kinases is a key component of this signaling pathway, and

therefore PI3K has become a research hotspot for targeted drugs

(12).

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is composed of

three main acting molecules, namely PI3K, PKB/Akt and mTOR, and it

is a central regulatory mechanism that can promote the growth and

proliferation of tumor cells and inhibit autophagy (13). Neuroceroid lipofuscins (NCLs) are a

common cause of neurodegeneration in children (14). The sixth known NCL gene is CLN5,

which is predicted to encode a novel protein with two putative

transmembrane domains (15). The

CLN5 protein is a 407-amino acid, highly glycosylated protein with

unknown functions. It is localized to lysosomes through the

mannose-6-phosphate receptor pathway and other signaling pathways

(16). Pathogenic mutations result

in its retention in the ER/Golgi matrix (17). Lysosomes can effectively control

autophagy (18). Recently,

researchers examined the association between mTORC1 activation and

lysosomal localization through CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of lysosomal

localization-associated protein components, revealing that limbic

lysosomes could facilitate the activation of the mTORC1, mTORC2 and

Akt signaling pathways (19).

Therefore, the current study speculated that CLN5 may serve a role

in GBM. In the present study, the effect of CLN5 on GBM was

investigated at the molecular level.

Materials and methods

Agents

Antibodies against CDK4 (cat. no. 11026-1-AP;

1:1,000), CDK6 (cat. no. 14052-1-AP; 1:1,000), Akt (cat. no.

10176-2-AP; 1:1,000), mTOR (cat. no. 20657-1-AP; 1:1,000), GAPDH

(cat. no. 10494-1-AP; 1:1,000) and HRP-conjugated sheep

anti-rabbit/mouse (ES-0005, 1:5,000) were ordered from the

ProteinTech Group, Inc. Antibodies against CLN5 (cat. no. ab170899;

1:1,000), Bcl-2 (cat. no. ab32124; 1:1,000), Bax (cat. no. ab32503;

1:1,000), phosphorylated (p)-Akt (cat. no. ab38449; 1:1,000),

cyclin D1 (cat. no. ab134175; 1:1,000), pro-caspase-9 (cat. no.

ab138412; 1:1,000), activated-caspase-9 (cat. no. ab219590;

1:1,000), and p-mTOR (cat. no. ab109268; 1:1,000) were ordered from

Abcam.

Gene expression profiling interactive

analysis (GEPIA)

The expression of CLN5 and overall survival were

analyzed using GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), which include data from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (http://www.tcga.org/) and the Genotype-Tissue

Expression (http://commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx/) databases. For the

analysis of gene expression, Log2(Transcripts Per

Million + 1) was use for log-scale. The cut-off of |Log2

fold-change| was 1 and P<0.01 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. The log-rank test, also known

as Mantel-Cox test, was used for the analysis of overall

survival.

Cell lines and cell culture

U251 and U87MG (glioblastoma of unknown origin) cell

lines were purchased from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection

of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China and

authenticated via STR profiling. The cells were cultured in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS (both from Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and penicillin (100

U/ml) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The cells were

washed with PBS 3 times at the logarithmic growth stage, then

digested with 0.25% trypsin for 3–4 min and seeded in a 6-well

plate for subsequent experiments.

Transfection

Transfection was performed according to the

instructions for the Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The complete culture medium was

replaced 2 h before transfection. The small interfering (si)-CLN5

(OriGene Technologies, Inc.) sequence was 5′-CCTTATTGTCAAGCTAAGT-3′

and the negative control (NC) siRNA (OriGene Technologies, Inc.)

sequence was 5′-GGCUGUAUGAGCACCGUUATT-3′. A total of 5 µl liposome

was dissolved into 125 µl serum-free and antibiotic-free medium,

then mixed gently and left at room temperature for 5 min.

Additionally, 5 µl si-CLN5 (50 nM) was dissolved into 125 µl

serum-free and antibiotic-free medium, mixed gently and left at

room temperature for 5 min. The liposome solution was mixed with

the si-CLN5 solution for 30 min. The cells were washed twice with

PBS. The mixture was added into the cells of each well (1×105

cells/well), gently mixed and cultured in the incubator. The cells

were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, then the complete culture medium

was replaced with fresh complete medium, and subsequent experiments

were performed after 24 h of continuous culture.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR detection

The Ultrapure RNA kit (CoWin Biosciences) was used

to extract the total RNA from cells. After reverse transcription at

85°C for 5 min using the Reverse Transcription Reaction kit (CoWin

Biosciences), real-time fluorescence qPCR was used to detect the

expression levels of CLN5. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec,

60°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 30 min. The primers are listed as

follows: CLN5 forward, 5′-CAAGCGCTTTGACTTCCGTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCAAACCATGTCTCTGCCCC-3′; β-actin forward,

5′-CCCGAGCCGTGTTTCCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTCCCAGTTGGTGACGATGC-3′.

Time PCR system was performed using Super TaqMan Mixture (CoWin

Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. β-actin

was used as an internal control. The results were calculated using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (20).

Western blotting

For the immunoblot analysis, the NC and the

experimental groups underwent inference for 24 h, then the 6-well

plate was placed on ice. RIPA lysis buffer (supplemented with a

protease inhibitor; both from CoWin Biosciences) was used to

extract total protein, and the protein concentration was determined

using a BCA assay (CoWin Biosciences). A total of 20 µg

protein/lane was separated via 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and the proteins

were then transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with 5%

skimmed milk for 1 h at 37°C. The membrane was incubated with the

aforementioned primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed 3 times

(5 min each) with TBS-Tween-20 (0.05%; v/v) and then incubated with

the respective secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature.

ECL (EMD Millipore) was used to visualize the protein bands after

the membrane was washed. Quantity One 4.6 software (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) was used to calculate the gray value.

Cell proliferation and viability

assays

Proliferation was assessed using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology, Co., Ltd.)

and colony formation assays. According to the manufacturer's

protocol, after 24 h of transfection, the cells were digested and

counted, and 2,000 cells/well were seeded in a 96-well plate. The

cells were then cultured in an incubator at 37°C for 1 h. A total

of 10 µl CCK-8 reagent was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h

before detection. Every 24 h, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm

by a microplate reader.

For colony formation assays, cells were seeded into

a 6-cm plate after transfection and incubated for 2 weeks at 37°C.

Subsequently, cells were fixed with methanol for 15 min at room

temperature and stained with Giemsa for 20 min at room temperature.

Colonies with >10 cells were counted in 5 random fields.

Transwell assay for invasion

detection

Invasion was evaluated using Transwell chambers (EMD

Millipore). Matrigel® (cat. no. 356234, BD Biosciences)

was diluted in serum-free medium at the ratio of 1:6, and 100 µl

was added into the upper chamber, then incubated at 37°C for 4–6 h.

After transfection for 24 h, 5×104 cells in 500 µl

serum-free medium were added to the upper chamber, and 500 µl

complete medium was added to the lower chamber. After overnight

incubation at 37°C, a cotton swab was used to wipe off the

remaining cells in the upper chamber. After washing with PBS, cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature

and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at 37°C, then

counted under the fluorescence microscope (magnification,

×100).

Cell migration assay

The migration of U251 and U87MG cells was detected

via scratch assay. After digestion, 5×104 cells/well

were seeded in a 6-well plate in 500 µl serum-free medium, and

cells were cultured until confluency overnight at 37°C. The cells

were scratched and cell migration was recorded every 24 h under the

fluorescence microscope (×40 magnification). The results were

processed using ImageJ version 1.8.0 software (National Institutes

of Health), and the cell migratory ability was assessed based on

the extent of the area of cell migration between the control group

and the experimental group.

Gelatinase spectrum

Gelatinase spectrum was used to detect MMP-2

expression. After transfection, the NC and experimental groups were

incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and were then washed with serum-free

DMEM 3 times and cultured for 24 h at 37°C. The supernatant was

collected via centrifugation in 5,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, diluted

with serum-free DMEM without mercaptoethanol and added into each

well of the vertical electrophoresis tank. The samples were

separated using 10% SDS-PAGE (0.5 mg/ml gelatin). After

electrophoresis, the gel was dyed with 0.25% Coomassie Blue R-250

at room temperature for 4 h and decolorized with decolorizing

liquid (10% acetic acid) at room temperature for 1 h. Following

this process, the gel was imaged using a camera (Olympus

Corporation). The gray value was analyzed using Quantity One 4.6

software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Cell apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

via flow cytometry

After 24 h of transfection, the cells were

serum-starved for 24 h and then digested with trypsin for 3–4 min

at 4°C without EDTA. Subsequently, they were collected into a

centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C and

resuspended in pre-cooled PBS at 4°C. After centrifugation, the

cell density was adjusted by adding 1X binding buffer to obtain

1–5×106 cells/ml. A total of 100 µl cell suspension and

5 µl Annexin-V/FITC (Beijing 4A Biotech Co., Ltd.) were added into

a 5-ml flow tube, incubated at room temperature in the dark for 5

min according to the manufacturer's protocol, and then 10 µl PI at

37°C for 5 min and 400 µl PBS were added to the mixture before flow

cytometry detection. FlowJo version 10.6.2 software (FlowJo LLC)

was used to analyze and process the flow cytometry (FACSCanto II;

BD Biosciences) results.

For cell cycle detection, ice-cold ethanol was used

to fix the cells for >24 h at 4°C. Subsequently, the procedure

for cell cycle detection was similar to the aforementioned

apoptosis detection. PI was used for single-staining at 37°C for 5

min and 400 µl PBS was added. FlowJo software was used to analyze

and process the flow cytometry results.

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software

(SPSS, Inc.). The comparison between two groups was performed using

unpaired Student's t-test. Results were expressed as the mean ± SD.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

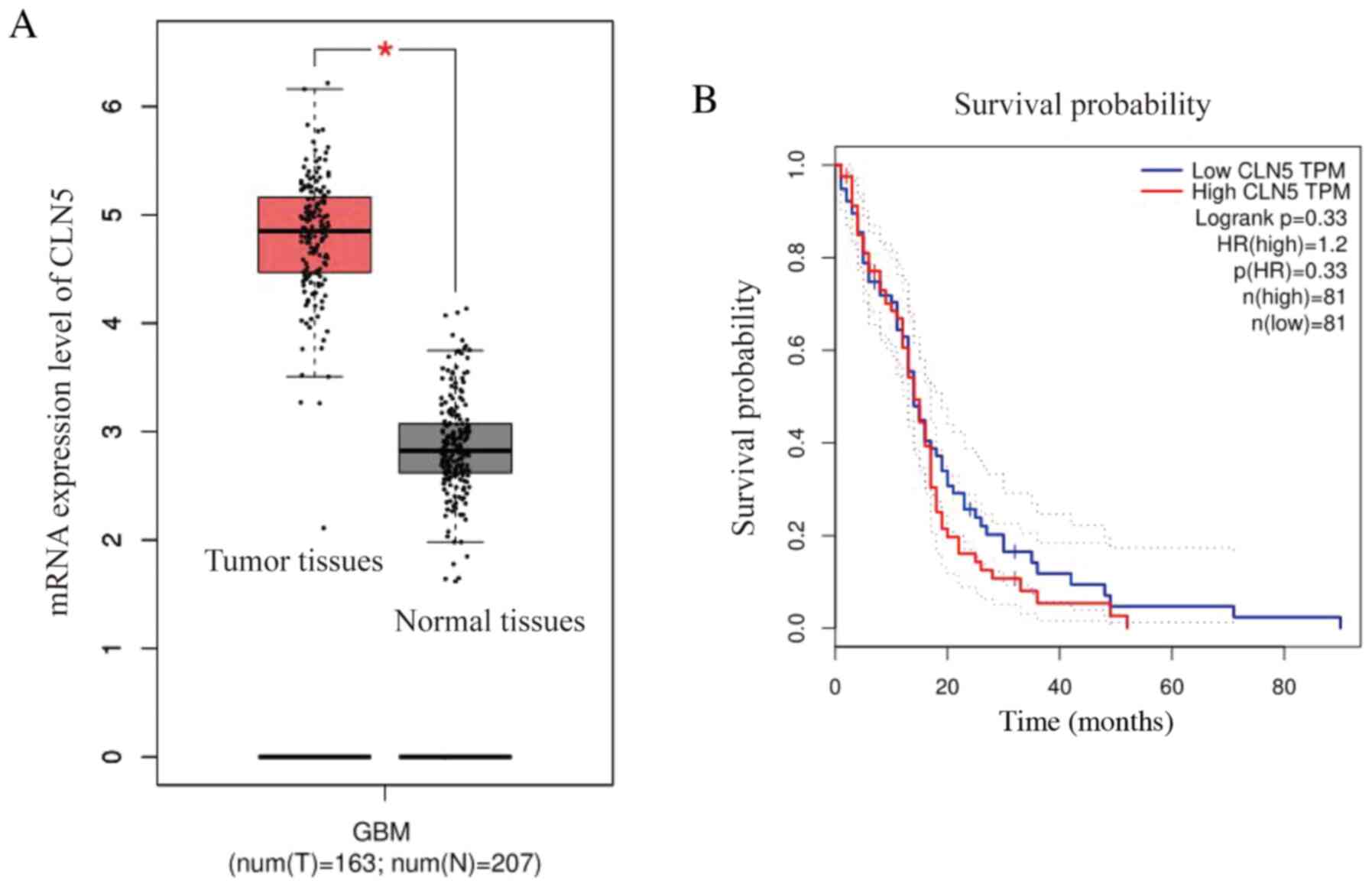

CLN5 expression is upregulated in

GBM

In order to study the association between CLN5

expression and GBM, GEPIA was used to extract RNA sequences from

The Cancer Genome Atlas and the Genotype-Tissue Expression

databases, in order to further understand the function of this gene

(21). The expression levels of CLN5

in GBM tissues were significantly higher compared with those in

normal tissues, indicating that CLN5 expression was upregulated in

GBM (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the

prognostic survival curve revealed that the overall survival rate

of patients with GBM with high CLN5 expression was lower than that

of patients with low CLN5 expression; however, there was no

significant effect of CLN5 expression on survival (Fig. 1B).

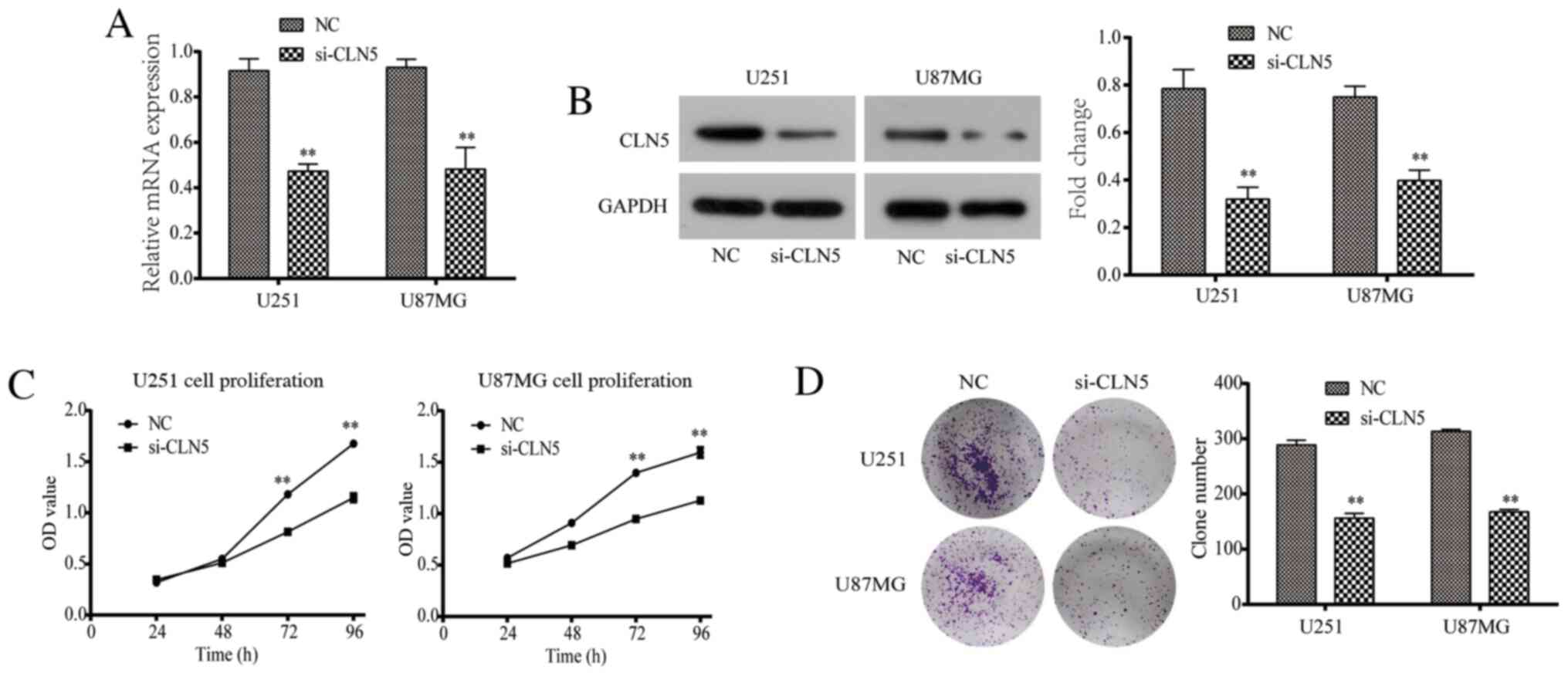

Knockdown of CLN5 decreases the

proliferation of GBM cells in vitro

RT-qPCR and western blotting were used to evaluate

the efficiency of CLN5-knockdown. The results revealed that CLN5

mRNA and protein expression levels in the si-CLN5 group were

significantly decreased in both U251 and U87MG cells compared with

those in the NC group (Fig. 2A and

B).

The CCK-8 assay was performed to detect the

proliferation of U251 and U87MG cells. The data revealed that after

72 and 96 h of culture, the proliferative ability of the si-CLN5

group was significantly decreased compared with that of the NC

group (P<0.05; Fig. 2C). In

addition, the colony assay demonstrated that the colony formation

ability of the si-CLN5 group was significantly lower than that of

the NC group (P<0.05; Fig. 2D).

Therefore, CLN5-knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferation

of GBM cells in vitro.

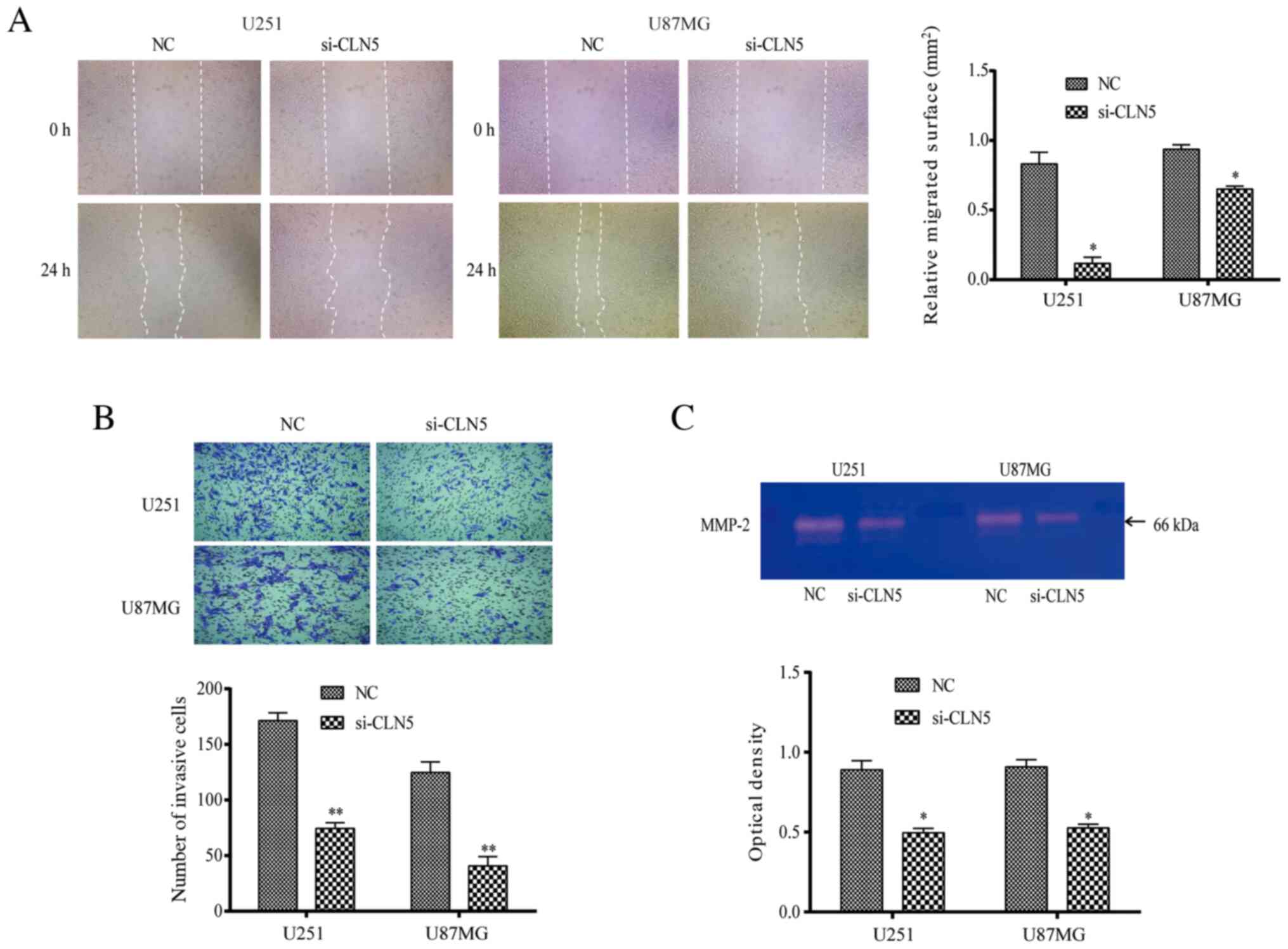

CLN5-knockdown inhibits the migration

and invasion of GBM cells

The migration of U251 and U87MG cells was detected

using the scratch test. The results revealed that the healing area

of the si-CLN5 group was decreased compared with that of the NC

group in both cell lines (P<0.05; Fig. 3A), indicating that migration of the

si-CLN5 group was inhibited. Transwell assays were performed to

evaluate the cell invasive ability. The invasive ability of the

si-CLN5 group was significantly decreased compared with that of the

NC group in both U251 and U87MG cells (P<0.05; Fig. 3B). Additionally, gelatinase spectrum

was performed to investigate MMP-2 expression, which is an

important factor affecting cell migration and invasion. MMP-2

expression in the si-CLN5 group was significantly lower than that

in the NC group (P<0.05; Fig.

3C). Therefore, the results revealed that CLN5-knockdown

inhibited the migration and invasion of GBM cells.

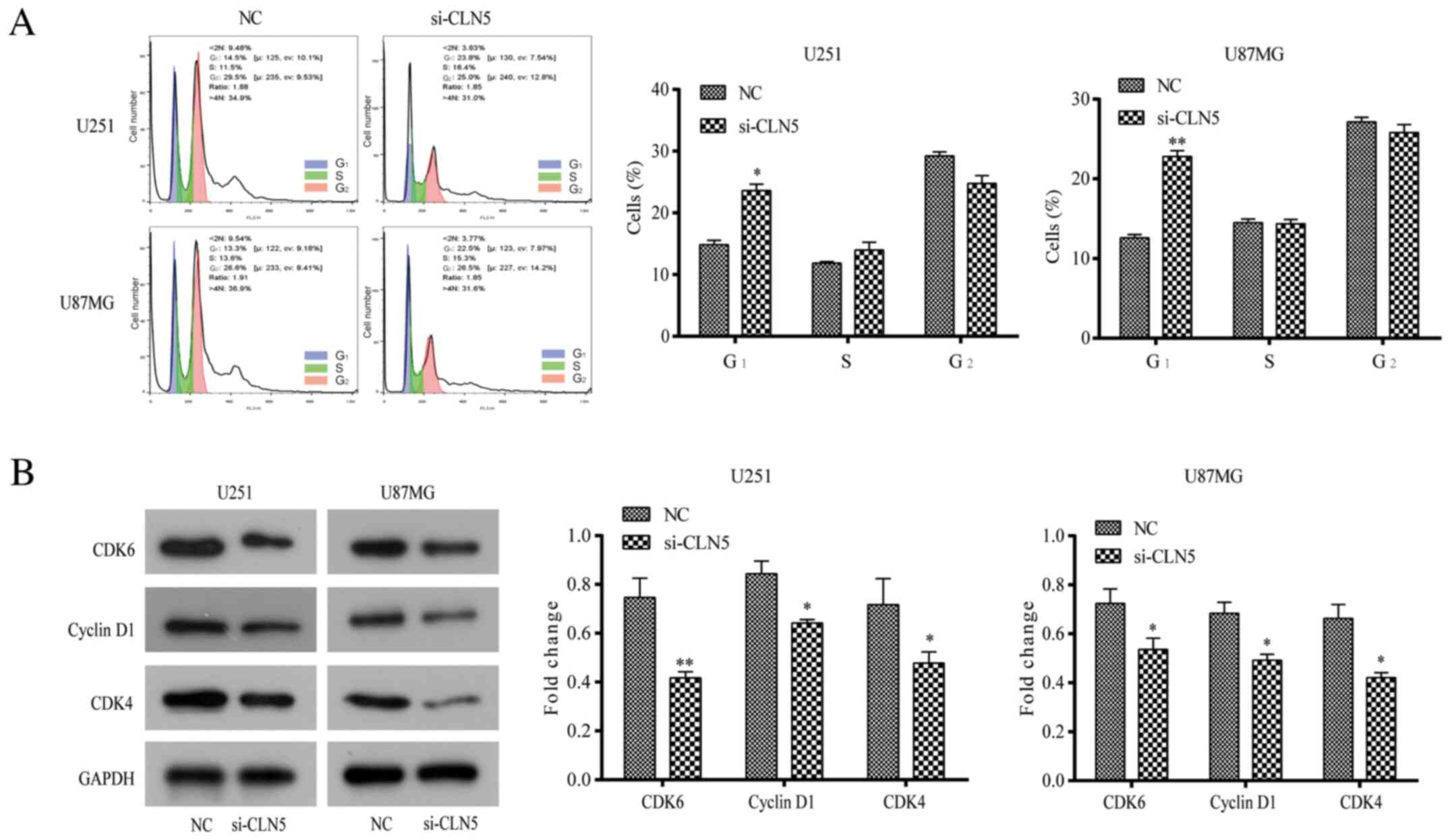

Depletion of CLN5 induces G1-phase

arrest in GBM cells

The cell cycle distribution of GBM CLN5-knockdown

cells was studied to determine the effect of CLN5 on the cell

cycle. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the number of cells in

G1 phase transfected with si-CLN5 was significantly higher than

that of NC cells (P<0.05), while there was no significant

difference between S-phase and G2-phase cells (Fig. 4A). To further explore the regulatory

mechanism of G1-phase arrest, the expression levels of

cycle-associated molecules such as cyclin D1, CDK4 and CDK6, were

analyzed. Compared with NC cells, the expression levels of these

proteins in the si-CLN5 group were significantly decreased

(P<0.05; Fig. 4B), suggesting

that CLN5-knockdown may inhibit the proliferation of GBM cells by

blocking the G1 phase of the cell cycle.

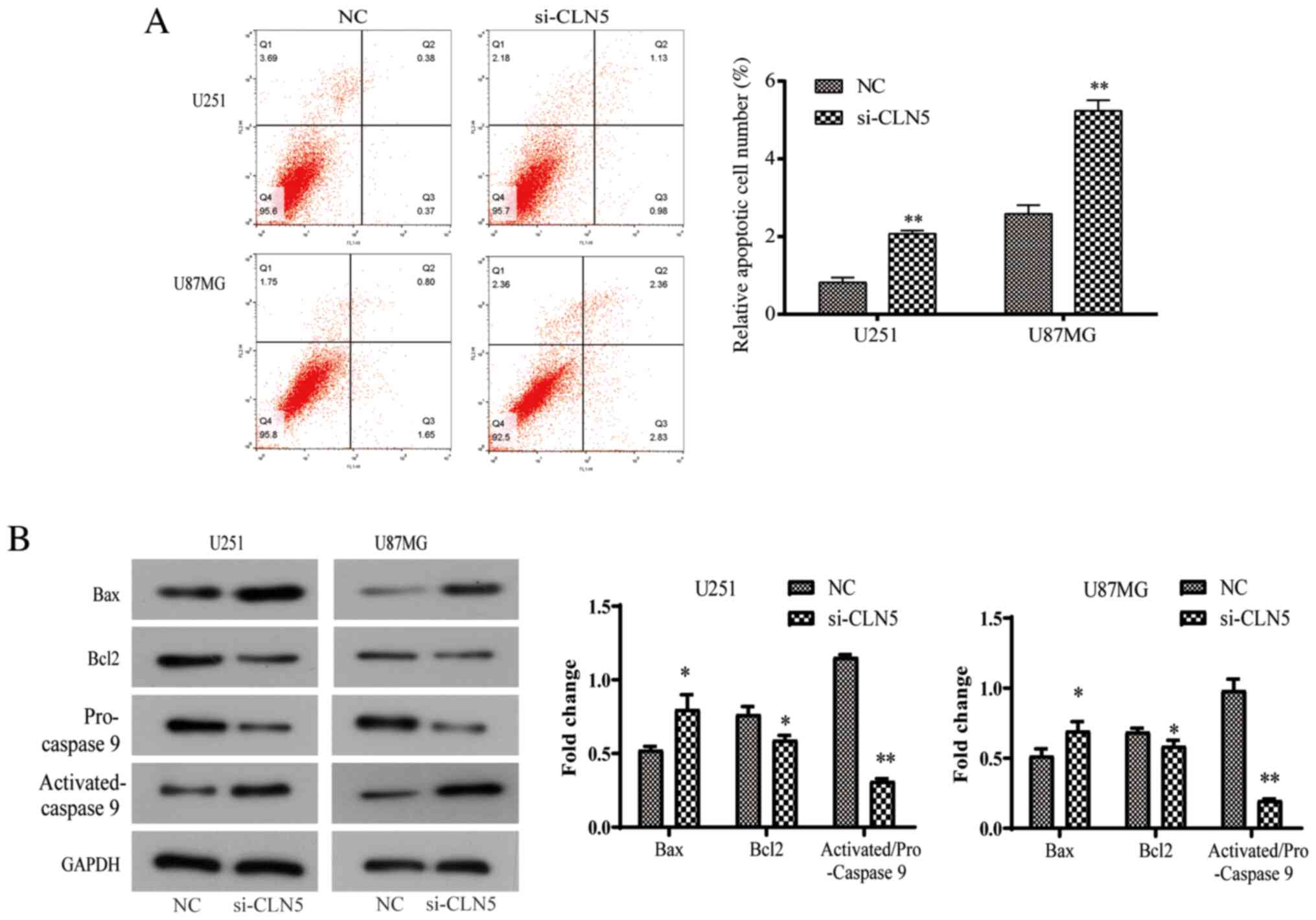

CLN5-knockdown promotes the apoptosis

of GBM cells

Due to the abnormal rate of cell proliferation and

irregular cell cycle, the present study further investigated the

potential mechanism of the effect of CLN5 on the life cycle of GBM

cells. Apoptosis is an important regulator of cell proliferation.

Flow cytometry was used to detect apoptosis after Annexin V-FITC

and PI double-staining. The results revealed that the apoptosis

rate increased significantly after si-CLN5 transfection (P<0.05;

Fig. 5A). In addition, changes in

the protein expression levels of Bcl-2, activated-caspase-9 and Bax

were investigated, which are closely involved in the process of

apoptosis. In the si-CLN5 group, the expression levels of Bax and

activated-caspase-9 were increased, while Bcl-2 expression was

decreased, indicating that CLN5-knockdown increased the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio (Fig. 5B). In conclusion, the

present results revealed that CLN5 may be an important factor in

the regulation of apoptosis in GBM cells.

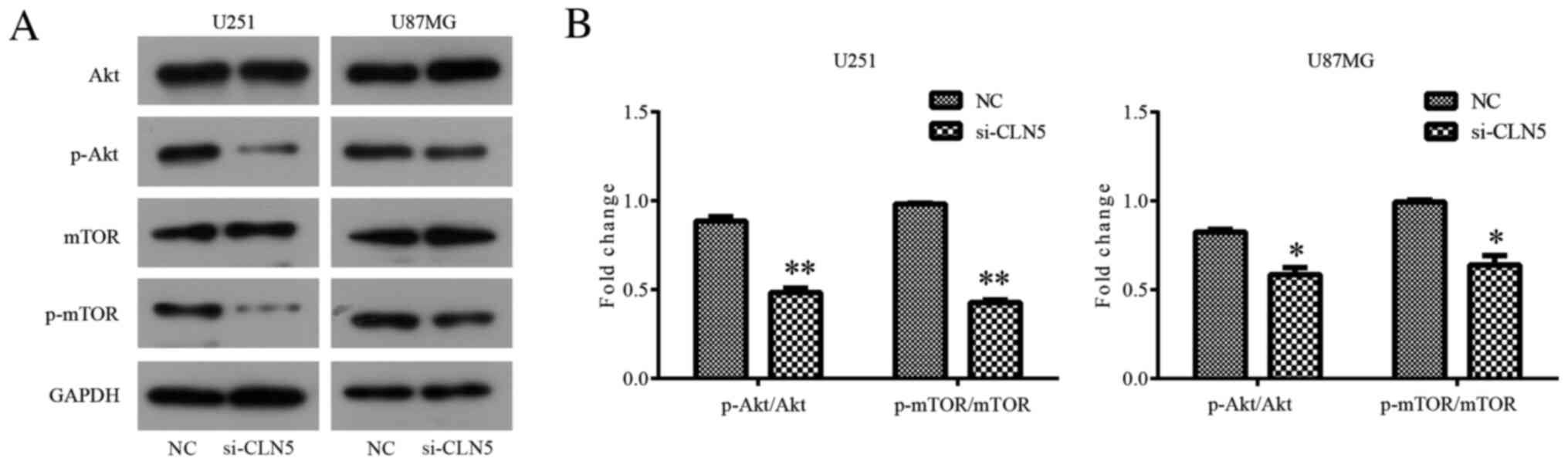

Knockdown of CLN5 inhibits the

Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in GBM cells

In order to further explore the mechanism of the

effect of CLN5 on GBM, western blotting was used to detect the

changes in the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway after CLN5-knockdown. The

results revealed that there was no significant change in total Akt

expression in si-CLN5 cells compared with in the NC group; however,

CLN5-knockdown significantly decreased the levels of p-Akt in both

U251 (P<0.01) and U87MG (P<0.05) cells (Fig. 6). Therefore, it was suggested that

CLN5-knockdown inhibited the activation of the Akt signaling

pathway in GBM. In addition, changes in the mTOR signaling pathway

were analyzed. The inhibitory effect of CLN5-knockdown on the mTOR

signaling pathway was similar to that in the Akt signaling pathway,

with significantly decreased levels of p-mTOR in the si-CLN5 group

compared with in the NC group (P<0.01 in U251 and P<0.05 in

U87MG; Fig. 6). The present results

suggested that CLN5 may affect the development of GBM by regulating

the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway.

Discussion

GBM is one of the most lethal types of cancer in

humans due to its high malignancy, strong invasion and poor

prognosis (22). The CLN5 protein is

a 407 amino acid-long glycosylated protein with unknown functions.

The present study detected CLN5 upregulation in GBM tissues using

GEPIA; therefore, the association between the CLN5 gene and GBM

cells was further investigated. The results revealed that

CLN5-knockdown effectively inhibited the proliferation and invasion

of GBM cells, and promoted apoptosis.

At first, CCK-8 and clone formation assays were used

to investigate cell proliferation. It was revealed that

CLN5-knockdown effectively inhibited the proliferation of GBM cells

in vitro. Subsequently, the cell migratory and invasive

abilities were tested, and the results demonstrated that migration

and invasion decreased significantly after CLN5-knockdown. In the

process of tumor migration and invasion, one of the most important

factors is the degradation of the basement membrane and

extracellular matrix (23). MMP-2 is

a type of multi-matrix metalloproteinase that is involved in the

migration and invasion of tumors via the degradation of the

extracellular matrix; it is widely involved in numerous

pathological processes of tumor development (24) and serves an important role in cancer

cells (25). The present results

revealed that MMP-2 expression decreased significantly after si-RNA

transfection, indicating that CLN5-knockdown may regulate MMP-2

expression and inhibit cell invasion and migration.

In order to further study the role of CLN5 in cell

proliferation and apoptosis, the association between CLN5 and the

Akt/mTOR signaling pathway was investigated. Cyclins are a family

of proteins related to chromosome condensation and mitotic spindle

involved in the regulation of the cell cycle (26,27). The

results of flow cytometry and western blotting revealed that

si-CLN5 downregulated the expression levels of cyclin D1, CDK4 and

CDK6, blocked the cell cycle at the G1-phase and induced early

apoptosis. In addition, si-CLN5 upregulated the expression levels

of Bax and downregulated Bcl-2 expression, which may trigger

mitochondrial apoptosis (28).

Furthermore, western blotting was used to detect molecules in the

Akt/mTOR signaling pathways, and CLN5-knockdown inhibited the

activation of the Akt and mTOR signaling pathways in GBM by

decreasing the levels of p-Akt and p-mTOR. However, the antitumor

effect of CLN5 has not been verified in mouse models. The mechanism

of CLN5 upregulation in glioma and the specific downstream target

of CLN5 remain unclear. In the future, further research is required

to clarify the regulatory mechanism of CLN5 in human GBM cells.

In conclusion, the present analysis revealed that

CLN5-knockdown inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis in

human GBM cells by potentially inhibiting the Akt and mTOR

signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JX and YL mainly performed the experiments. JX

analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. HZ contributed to

analyzing the data and modifying the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee

WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW and Kleihues P: The 2007

WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta

Neuropathol. 114:97–109. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, Sminia P

and van den Bent MJ: Clinical features, mechanisms, and management

of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 9:453–461.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Davis FG, Freels S, Grutsch J, Barlas S

and Brem S: Survival rates in patients with primary malignant brain

tumors stratified by patient age and tumor histological type: An

analysis based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

(SEER) data, 1973–1991. J Neurosurg. 88:1–10. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Penas-Prado M and Gilbert MR: Molecularly

targeted therapies for malignant gliomas: Advances and challenges.

Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 7:641–661. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tachon G, Masliantsev K, Rivet P,

Petropoulos C, Godet J, Milin S, Wager M, Guichet PO and

Karayan-Tapon L: Prognostic significance of MEOX2 in gliomas. Mod

Pathol. 32:774–786. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Komori T, Sasaki H and Yoshida K: Revised

WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system:

Summary of the revision and perspective. No Shinkei Geka.

44:625–635. 2016.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wolf A, Agnihotri S and Guha A: Erratum:

Targeting metabolic remodeling in glioblastoma multiforme.

Oncotarget. 9:348552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Khosla D: Concurrent therapy to enhance

radiotherapeutic outcomes in glioblastoma. Ann Transl Med.

4:542016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ohgaki H and Kleihues P: Genetic pathways

to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 170:1445–1453.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xu P, Yang J, Liu J, Yang X, Liao J, Yuan

F, Xu Y, Liu B and Chen Q: Identification of glioblastoma gene

prognosis modules based on weighted gene co-expression network

analysis. BMC Med Genomics. 11:962018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gao XF, He HQ, Zhu XB, Xie SL and Cao Y:

lncRNA SNHG20 promotes tumorigenesis and cancer stemness in

glioblastoma via activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway.

Neoplasma. 66:532–542. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hudson K, Hancox UJ, Trigwell C, McEwen R,

Polanska UM, Nikolaou M, Morentin Gutierrez P, Avivar-Valderas A,

Delpuech O, Dudley P, et al: Intermittent high dose scheduling of

AZD8835, a novel selective inhibitor of PI3Kα and PI3Kδ,

demonstrates treatment strategies for PIK3CA-dependent breast

cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 15:877–889. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yu JZ, Ying Y, Liu Y, Sun CB, Dai C, Zhao

S, Tian SZ, Peng J, Han NP, Yuan JL, et al: Antifibrotic action of

Yifei Sanjie formula enhanced autophagy via PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling

pathway in mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis. Biomed Pharmacother.

118:1092932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mitchison HM and Mole SE:

Neurodegenerative disease: The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses

(Batten disease). Curr Opin Neurol. 14:795–803. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Savukoski M, Klockars T, Holmberg V,

Santavuori P and Peltonen L: CLN5, a novel gene encoding a putative

transmembrane protein mutated in Finnish variant late infantile

neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Nat Genet. 19:286–288. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vesa J, Chin MH, Oelgeschläger K,

Isosomppi J, DellAngelica EC, Jalanko A and Peltonen L: Neuronal

Ceroid Lipofuscinoses Are Connected at Molecular Level: Interaction

of CLN5 Protein with CLN2 and CLN3. Mol Biol Cell. 13:2410–2420.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lebrun AH, Storch S, Rüschendorf F,

Schmiedt ML, Kyttälä A, Mole SE, Kitzmüller C, Saar K, Mewasingh

LD, Boda V, et al: Retention of lysosomal protein CLN5 in the

endoplasmic reticulum causes neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in

Asian sibship. Hum Mutat. 30:E651–E61. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bouhamdani N, Comeau D, Cormier K and

Turcotte S: STF-62247 accumulates in lysosomes and blocks late

stages of autophagy to selectively target von

Hippel-Lindau-inactivated cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physio.

316:C605–C620. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jia R and Bonifacino JS: Lysosome

positioning influences mTORC2 and AKT signaling. Mol Cell.

75:26–38.e3. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Ge G, Li C and Zhang

Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W98–W102.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bahadur S, Sahu AK, Baghel P and Saha S:

Current promising treatment strategy for glioblastoma multiform: A

review. Oncol Rev. 13:417:2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yilmaz M, Christofori G and Lehembre F:

Distinct mechanisms of tumor invasion and metastasis. Trends Mol

Med. 13:535–541. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schrump DS, Chen A and Consoli U:

Inhibition of lung cancer proliferation by antisense cyclin D.

Cancer Gene The. 3:131–135. 1996.

|

|

25

|

Stewart CJ and Crook ML: CD147 (EMMPRIN)

and matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in uterine endometrioid

adenocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 207:30–36. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hoshyar R, Bathaie SZ and Sadeghizadeh M:

Crocin Triggers the apoptosis through increasing the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio and caspase activation in human gastric adenocarcinoma, AGS,

cells. DNA Cell Biol. 32:50–57. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Viallard JF, Lacombe F, Belloc F,

Pellegrin JL and Reiffers J: Molecular mechanisms controlling the

cell cycle: Fundamental aspects and implications for oncology.

Cancer Radiother. 5:109–129. 2001.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang HL, Kuo YH, Tsai CT, Huang YT, Chen

SC, Chang HW, Lin E, Lin WH and Hseu YC: Anti-metastatic activities

of Antrodia camphorata against human breast cancer cells

mediated through suppression of the MAPK signaling pathway. Food

Chem Toxicol. 49:290–298. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|