Introduction

Renal carcinoma (RC) is responsible for

approximately 90% of all kidney cancers in adults (1). RC is classified into several

histological cell types based on the genetic, histological and

clinical phenotypes; clear cells, granular cells, mixture cells and

undifferentiated cells (2–4). The cancer cells are resistant to

radiation, chemical and hormone therapies in RC patients and cannot

be treated without surgery (5,6).

Therefore, it is essential to identify more efficient

chemotherapeutic agents for RC treatment.

Dapagliflozin is a new type 2 diabetes drug that

decreases blood glucose levels by inhibition of sodium/glucose

cotransporter (SGLT2) in the kidney (7–9). It

has been reported that empagliflozin, a SGLT2 inhibitor, mediates

apoptosis through inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling molecule

expression and migration by activating adenosine

monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) in cervical cancer

(10). Previous studies

demonstrate that dapagliflozin exerts anti-proliferative and

anti-tumor activity in human kidney and breast tumor cells through

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, tumor growth inhibition or

AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways (11,12).

Moreover, dapagliflozin reduces tumor volume and activates

caspase-3, beclin-1 and JNK in solid Ehrlich carcinoma mice

(13). Nevertheless, the mechanism

underlying dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis has not been presented

in human RC.

The cellular Fas-associated death domain-like

interleukin-1-converting enzyme-inhibitory protein (cFLIP) is an

important apoptosis-regulatory protein associated with apoptosis

(14). cFLIP has

cFLIPL, cFLIPS and cFLIPR isoforms

(15). Each of these isoforms has

different effects on apoptotic pathways through different

mechanisms (16–19). Overexpression of cFLIP suppresses

death ligand-mediated cell death and confers resistance to

chemotherapeutic agents (20).

Constant cFLIP mRNA levels and cFLIP protein stability decrease the

sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs in the cFLIP-overexpressing

bladder and colorectal cancers (21–23).

Hence, modulation of cFLIP, an anti-apoptotic protein, plays a key

role in elucidating the mechanism of chemopreventive–mediated

apoptosis.

In the present investigation, we showed that

dapagliflozin mediated apoptosis in human RC Caki-1 cells by

caspase-dependent pathway via the downregulation of

cFLIPL and an increase in cFLIPS

instability.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and materials

Caki-1 cells were purchased from American Type

Culture Collection (HTB-46) and maintained in DMEM (LM 001–05;

WelGene) with 10% FBS (S001-07; WelGene) and 1% anti-biotic

anti-mycotic (AA) solution (LS 203-01; WelGene). HK-2 cells were

obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (22190) and maintained in

RPMI1640 medium (LM 011-01; WelGene) supplemented with 10% FBS and

1% AA solution. The cells were maintained at 37°C under 5%

CO2 condition. z-VAD-fmk (627610) was obtained from

Calbiochem. Dapagliflozin (SC-364481), N-acetylcysteine (NAC;

A7250) and cycloheximide (CHX; C1988) were obtained from

Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell viability assay

2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)–2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide

(XTT) assays were analyzed using the Welcount Cell Viability Assay

Kit (TR055-01; WelGene). Caki-1 and HK-2 cells were seeded

(0.2×105 cells/well) into three 96-well plates

containing DMEM or RPMI1640 with 10% FBS. Cells were expose to 0,

20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 µM of dapagliflozin for 24 h and then

cultivated with XTT reagent for 2–3 h at room temperature. The

density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo

LabSystems) at 450/690 nm.

FACS analysis

0.4×106 cells were suspended in 100 µl of

cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 70011044; Thermo Fisher

Scientific) and 200 µl of 95% ethanol (1.00983.1011; Merck) was

mixed, and the sample was while vortexing. The cells were

cultivated for 3 h at 4°C, washed twice with cold PBS, and

resuspended in 250 µl of 1.12% sodium citrate buffer (pH 8.4) with

12.5 µg of RNase A (R4875; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The cells

were cultivated for 30 min at 37°C, mixed with 250 µl of 50 µg/ml

propidium iodide (PI; P4170; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 20 min

at 37°C. Cells were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting

(FACS) using CytoFLEX (B53000; Beckman Coulter).

Western blotting

The total cell lysates were prepared by resuspending

0.45×106 cells in 20–50 µl of RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM

Tris buffer, 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaF; 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton

X-100, 100 µM Na3VO4, pH 7.6) Total lysates

was quantified using a BCA kit (#23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific)

according to the manufacturer's protocols. The proteins (30–70 µg)

were isolated using 10 or 12% SDS-PAGE gels and electrotransferred

onto NC membranes (GE Healthcare). Target proteins were identified

using the respective antibodies and Immobilon Western

Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate Solution (WBKLS0100; Millipore) and

visualized by Davinch-Chemi (CAS-400SM; Davinch-K). Anti-PARP

antibody (1:1,000; #9542) and anti-Bax (1:1,000; #2772) were obtain

from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-caspase-3 (1:3,000;

ADI-AAP-113) and anti-FLIP (1:700; ALX-804-961-0100) were purchased

from Enzo Life Sciences. Anti-Bcl-2 (1:700; sc-7832), anti-Bcl-xL

(1:1,000, sc-634), anti-Mcl-1 (1:1,000; sc-12756), anti-cIAP1

(1:1,000; sc-7943), anti-cIAP2 (1:1,000; sc-517317) and

anti-β-actin antibody (1:5,000; sc-47778) were supplied by Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, and anti-XIAP (1:10,000; 610717) antibody was

obtained from BD Biosciences.

Annexin V/PI double staining

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Annexin V

apoptosis detection kit I (556547; BD Biosciences) was used to

determine cell death type. The cells were washed twice with cold

PBS, and then cell pellets resuspended in 1X binding buffer. This

suspended cells (100 µl) were stained with 5 µl of FITC-conjugated

Annexin V and then 5 µl PI. The cells were incubated for 15 min at

room temperature in the dark. After adding 400 µl of 1X binding

buffer to each tube, the cells were analyzed using CytoFLEX

(Beckman Coulter).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

The levels of cFLIPL and

cFLIPS mRNA was confirmed using RT-PCR. Total RNA was

isolated using Easy-Blue reagent (17061; iNtRON Biotechnology).

cDNA was prepared using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (18057018;

Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's

protocols. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The primers used

to target genes of cFLIPL, cFLIPS and GAPDH:

for cFLIPL, 5′-CGGACTATAGAGTGCTGATGG-3′ (forward) and

5′-GATTATCAGGCAGATTCCTAG-3′ (reverse); cFLIPS,

5′-TAAGCTGTCTGTCGGGGACT-3′ (forward) and

5′-AGATCAGGACAATGGGCATAG-3′ (reverse); GAPDH,

5′-AGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTG-3′ (forward) and

5′-GTGATGGCATGGACTGTGGT-3′ (reverse). The amplified PCR products

were separated by electrophoresing on a 1.5% agarose gel with 0.1%

ETBR, and the DNA bands were detected by an ultraviolet light gel

doc (WGD30; DAIHAN).

Stable transfection

Caki-1 cells were seeded onto 6-well culture plates

(0.25×106 cells/well) and cultivated overnight at 37°C.

Cells were transfected with the pcDNA 3.1-cFLIPL, pcDNA

3.1-cFLIPS or control pcDNA 3.1 plasmid vectors using

LipofectAMINE2000® (11668-019; Thermo Fisher Scientific)

in Opti-MEM medium (31985-070; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 48

h of transfection, the transfected cells were selected using

culture medium containing 800 µg/ml G418 (10131-035; Thermo Fisher

Scientific). The cells were then exposed to dapagliflozin for 24 h

and analyzed for cFLIPL and cFLIPS protein

expression using western blotting. After 2 or 3 weeks, to rule out

the possibility of clonal differences between the generated stable

cell lines, pooled Caki-1/pcDNA 3.1, Caki-1/cFLIPL and

Caki-1/cFLIPS clones were analyzed for cFLIPL

and cFLIPS protein expression using western

blotting.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were performed three independent

experiments. One-way ANOVA and post hoc comparisons (Scheffe) and

two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test (Tukey's HSD) were used

when comparing the situations. Statistical Package for Social

Sciences 27.0 (IBM SPSS Inc.) was utilized for the data analysis.

The data were expressed as the mean ± SD, and P-values <0.05

were considered significant.

Results

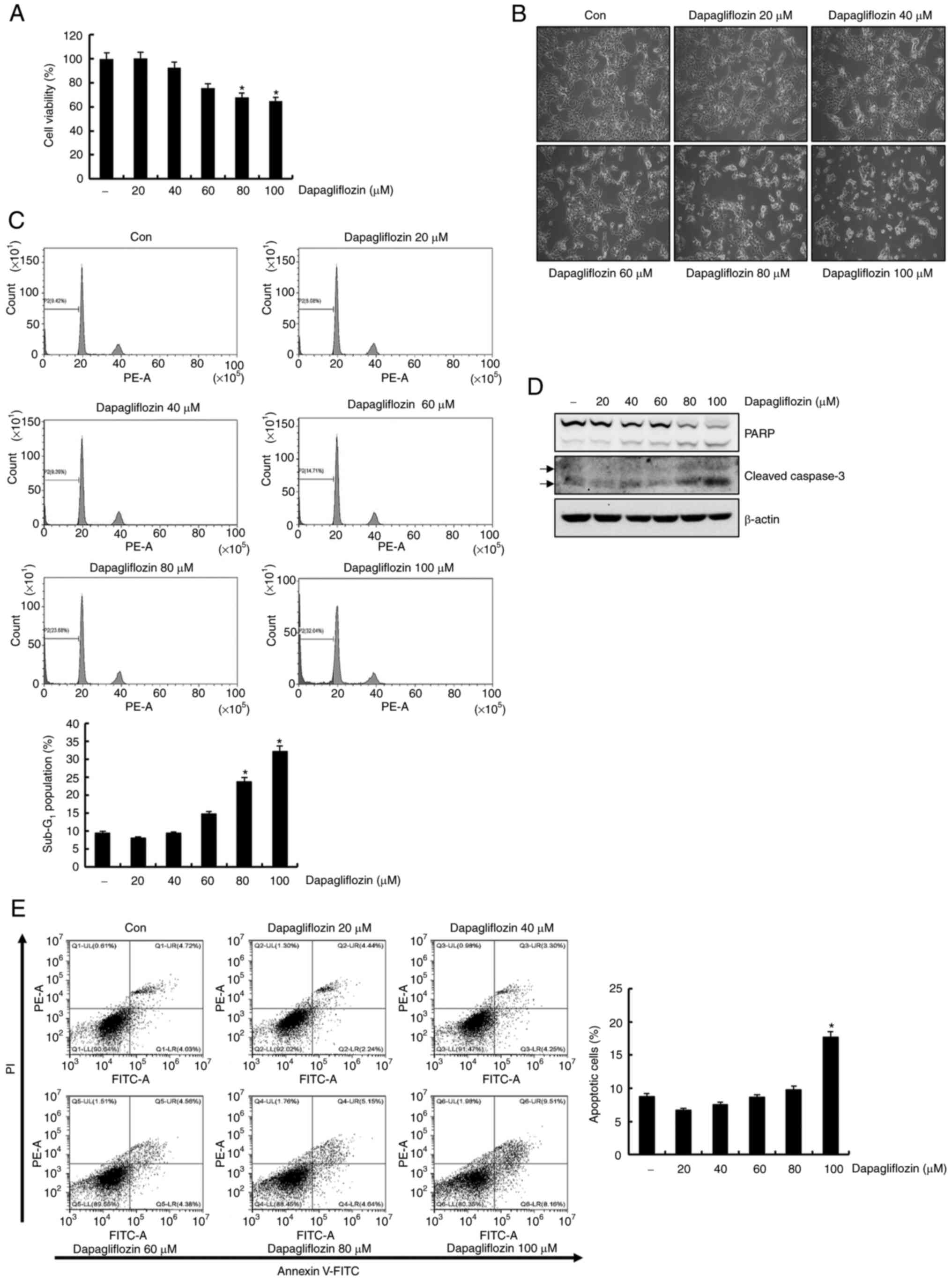

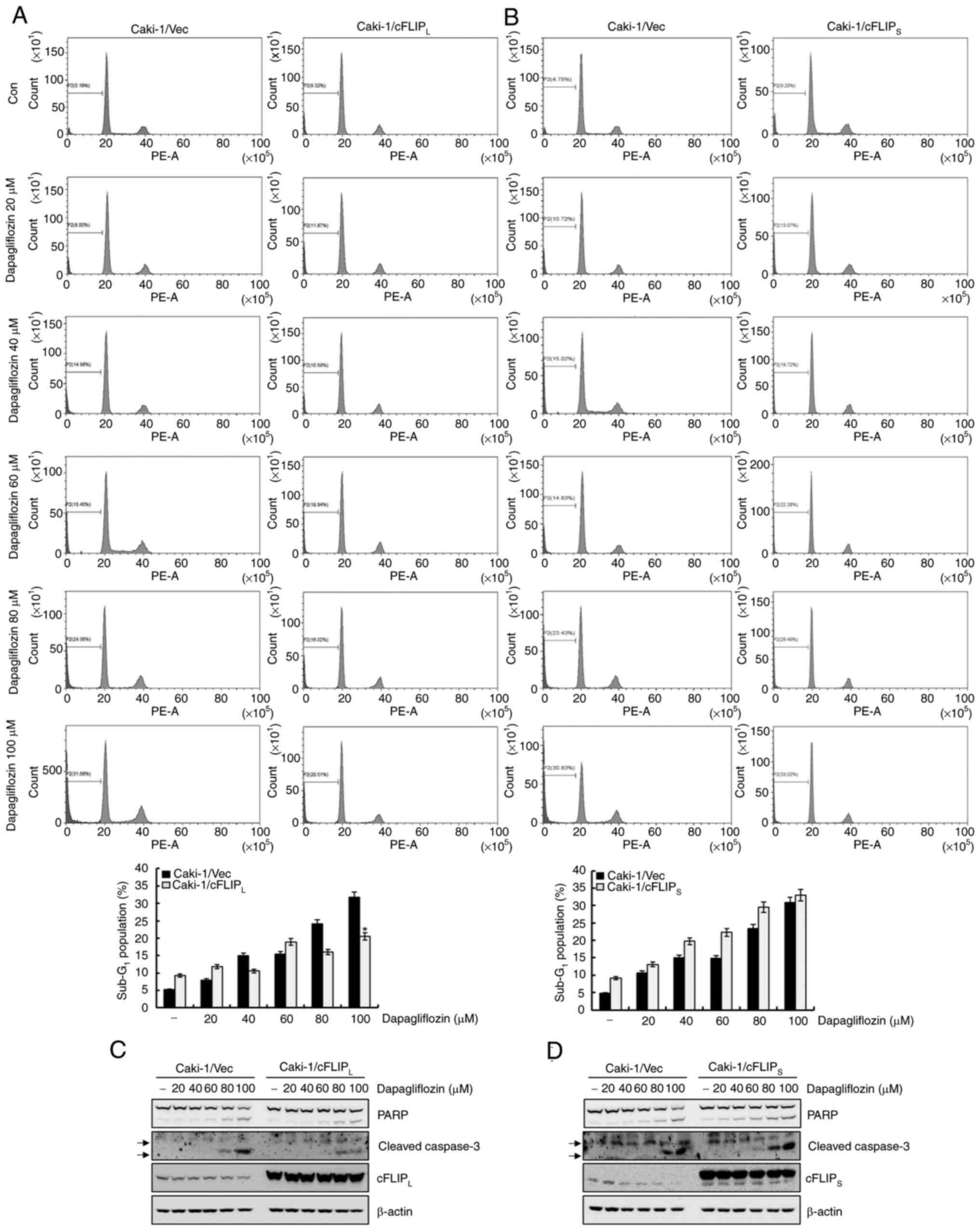

Dapagliflozin decreases cell viability

and induces apoptosis in Caki-1 cells

The anti-cancer effect of dapagliflozin on RC Caki-1

cells, the cells was investigated by treating the cells with 0, 20,

40, 60, 80 and 100 µM of dapagliflozin. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment of Caki-1 cells with

dapagliflozin showed a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability.

High concentrations (80 and 100 µM) dapagliflozin induced the

rounded cells of considerable number in Caki-1 cells under light

microscopy (Fig. 1B). We then

performed flow cytometry analysis of the dapagliflozin-treated

Caki-1 cells. Dapagliflozin treatment for 24 h significantly

increased the sub-G1 fraction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Exposure to dapagliflozin

increased the expression levels of cleavage form of PARP and

caspase-3 in Caki-1 cells (Fig.

1D). To determine cell death type induced by dapagliflozin, we

analyzed FITC-conjugated Annexin V/PI staining using flow

cytometry. Treatment with 100 µM of dapagliflozin increased Annexin

V/PI positive cells (Fig. 1E).

These observations supported that dapagliflozin induces apoptosis

in Caki-1 cells.

| Figure 1.Dapagliflozin induces apoptosis in

Caki-1 cells. (A) Cells were treated with dapagliflozin for 24 h.

Subsequently, cell viability was analyzed using a

2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide

assay kit. (B) Caki-1 cells were treated with dapagliflozin for 24

h and morphological findings were observed under a light microscope

at a magnification of ×200. (C) Caki-1 cells were exposed to

dapagliflozin for 24 h. The Sub-G1 fraction was measured

via flow cytometry. The FACS data are indicated in the upper panel.

The percentage of the sub-G1 population is shown in the

lower panel. (D) Cells were treated with varying concentrations of

dapagliflozin for 24 h. PARP, cleaved caspase-3 and β-actin protein

expression was examined by western blotting. β-actin was used as

the protein loading control. Cleaved caspase-3 is indicated by

arrows. (E) Caki cells were treated with dapagliflozin for 24 h.

The type of cell death, which is apoptosis or necrosis, was

confirmed via flow cytometry after FITC-conjugated Annexin V/PI

staining. The percentage of cells in each quadrant (Q1-UL, necrotic

cells; Q1-UR, late apoptotic cells; Q1-LL, live cells; Q1-LR, early

apoptotic cells) is indicated (left panel). The percentage of

apoptotic cells is shown in the right panel. Data were acquired in

three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± SD (n=3).

*P<0.05 compared with non-treated cells. Con, dapagliflozin 0

µM; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. |

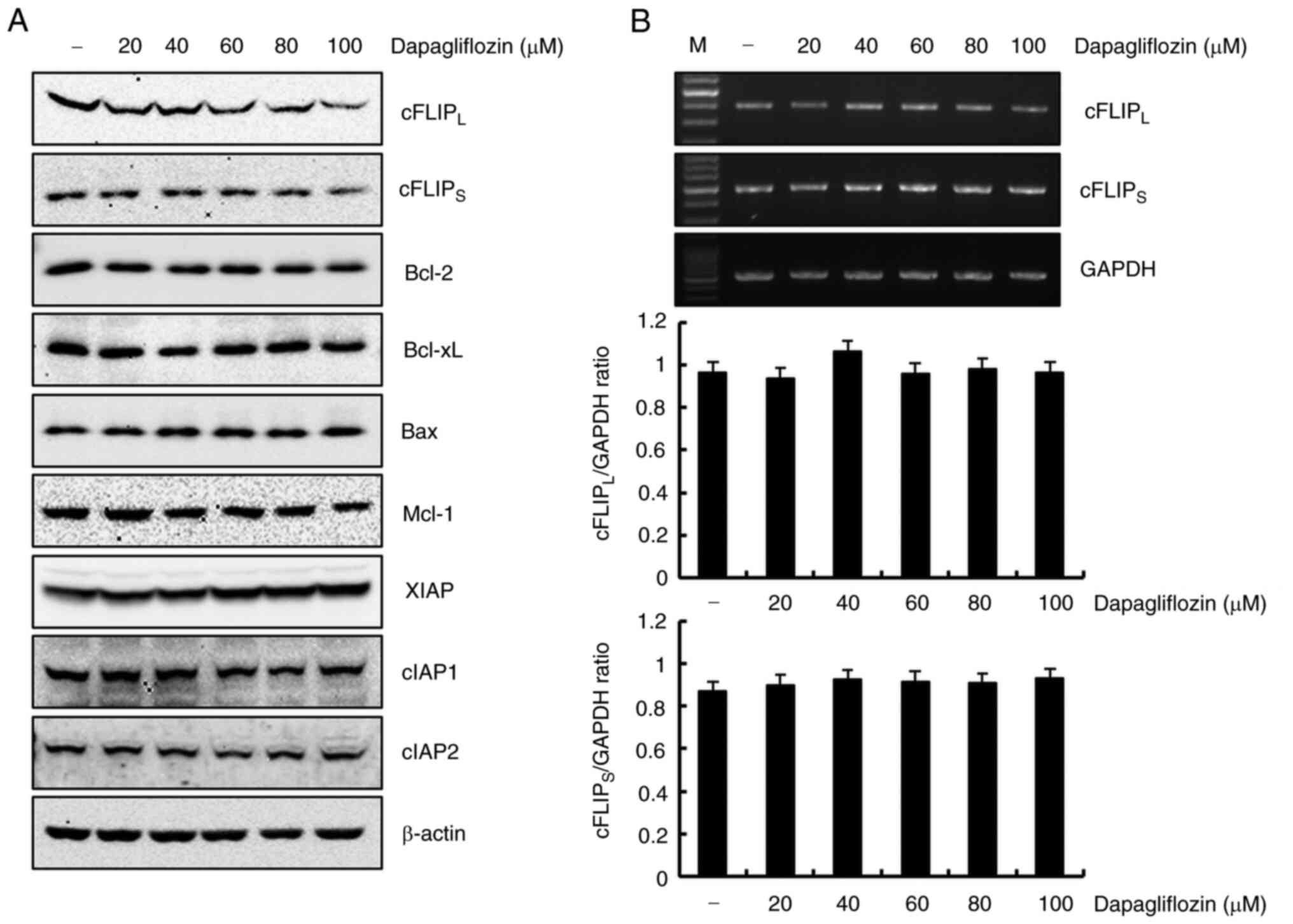

Dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis

reduces cFLIPL and cFLIPS expression

levels

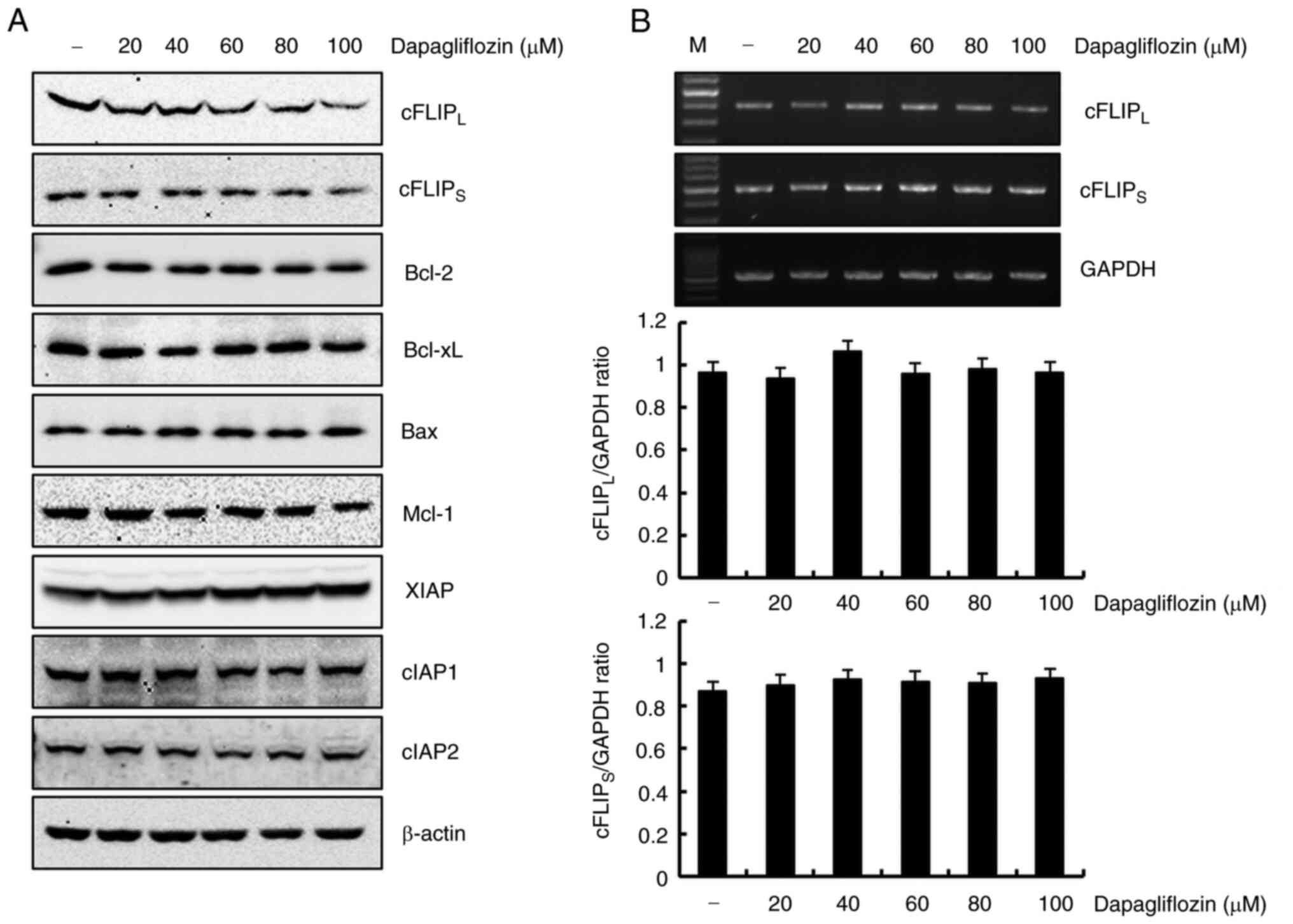

The detailed molecular mechanism associated with

dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis was studied by treating Caki-1

cells with dapagliflozin and analyzing the expression levels of

apoptotic regulatory proteins using western blotting. As shown in

Fig. 2A, cFLIPL and

cFLIPS protein expressions markedly reduced in

dapagliflozin-treated Caki-1 cells. However, protein expression

levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bax, Mcl-1, XIAP, cIAP1 and cIAP2 did not

change in response to dapagliflozin treatment. These results

demonstrated that dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis suppressed the

expression of cFLIPL and cFLIPS in Caki-1

cells. To determine whether the dapagliflozin-mediated

cFLIPL and cFLIPS reduction in protein

expression was regulated at the transcriptional level, we confirmed

RT-PCR. Exposure Caki-1 cells to dapagliflozin had no effect on

cFLIPL or cFLIPS expression at the

transcriptional level (Fig. 2B).

Therefore, dapagliflozin-mediated downregulation of

cFLIPL and cFLIPS expression levels is

modulated at the post-transcriptional level.

| Figure 2.Dapagliflozin inhibits

cFLIPL and cFLIPS protein expression in

Caki-1 cells. (A) Cells were treated with various concentrations of

dapagliflozin. At 24 h after treatment, protein expression levels

of cFLIPL, cFLIPS, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bax, Mcl-1,

XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2 and β-actin were analyzed using western

blotting. β-actin served as the protein loading control. (B) Caki-1

cells were treated with different concentrations dapagliflozin.

After 24 h, the levels of cFLIPL, cFLIPS and

GAPDH mRNA (upper panel) were determined using RT-PCR. GAPDH was

used as a loading control. The density of cFLIPL,

cFLIPS and GAPDH was analyzed using ImageJ software.

Data obtained from RT-PCR of cFLIPL, cFLIPS

and GAPDH were used to evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin on the

cFLIPL/GAPDH ratio (middle panel) and

cFLIPS/GAPDH ratio (lower panel). Data were acquired in

three independent experiments. PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase;

cFLIP, cellular Fas-associated death domain-like

interleukin-1-converting enzyme-inhibitory protein Mcl-1, myeloid

cell leukemia-1; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein;

cIAP, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein; RT-PCR, reverse

transcription PCR; M, marker of RT-PCR. |

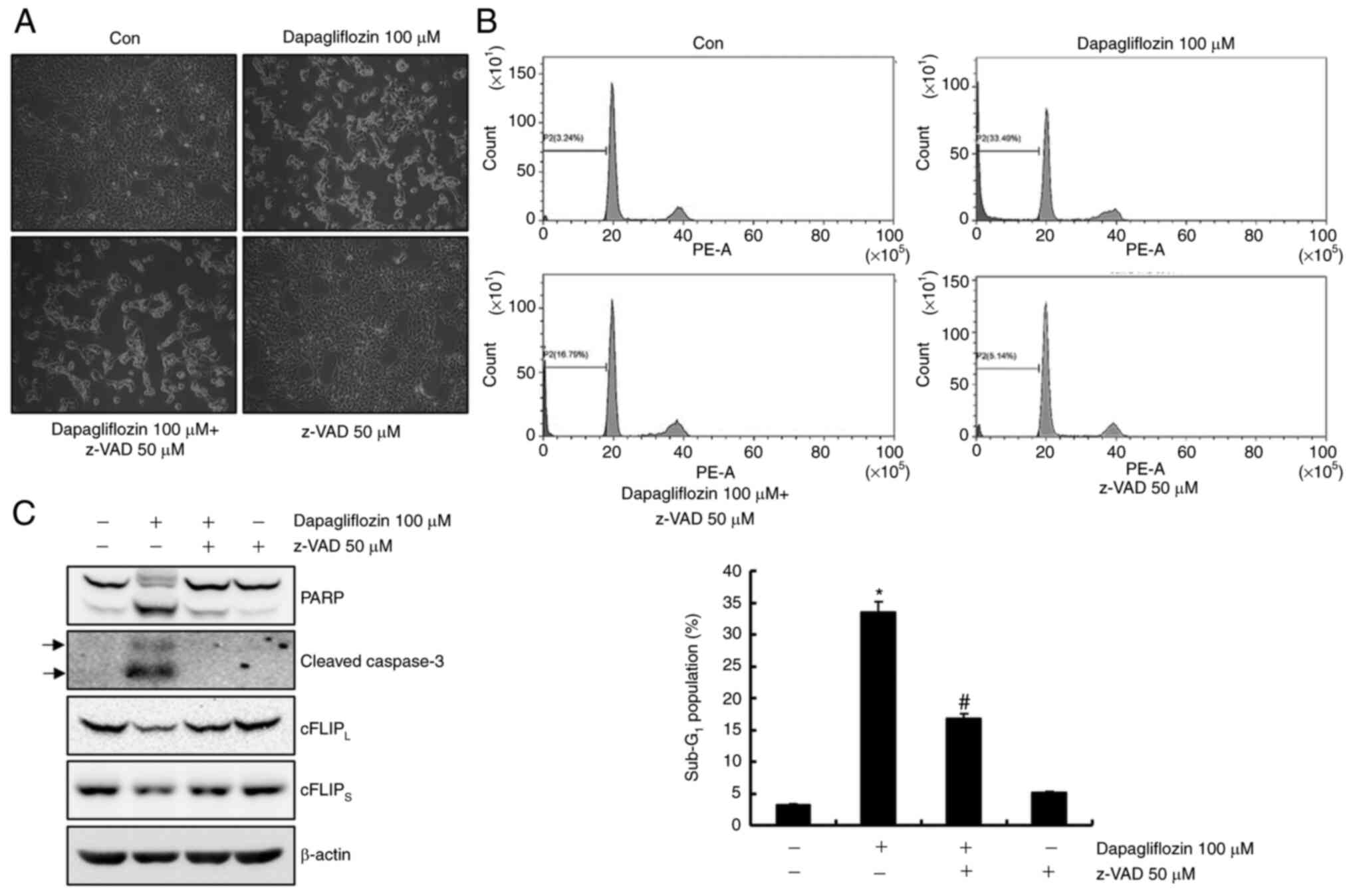

Dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is

inhibited via a caspase signaling pathway

To identify whether activation of the caspase

signaling pathway plays an important role in dapagliflozin-mediated

apoptosis, Caki-1 cells were pretreatment with a pan-caspase

inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk. As shown in Fig,

3A and B, pretreatment with z-VAD-fmk inhibited

dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. Moreover, pretreatment of Caki-1

cells with z-VAD-fmk prevented the cleavage forms of PARP and

caspase-3 and restored the cFLIPL and cFLIPS

expressions levels (Fig. 3C).

These findings suggest that dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis is

modulated by a caspase signaling pathway through cFLIPL

and cFLIPS downregulation in Caki-1 cells.

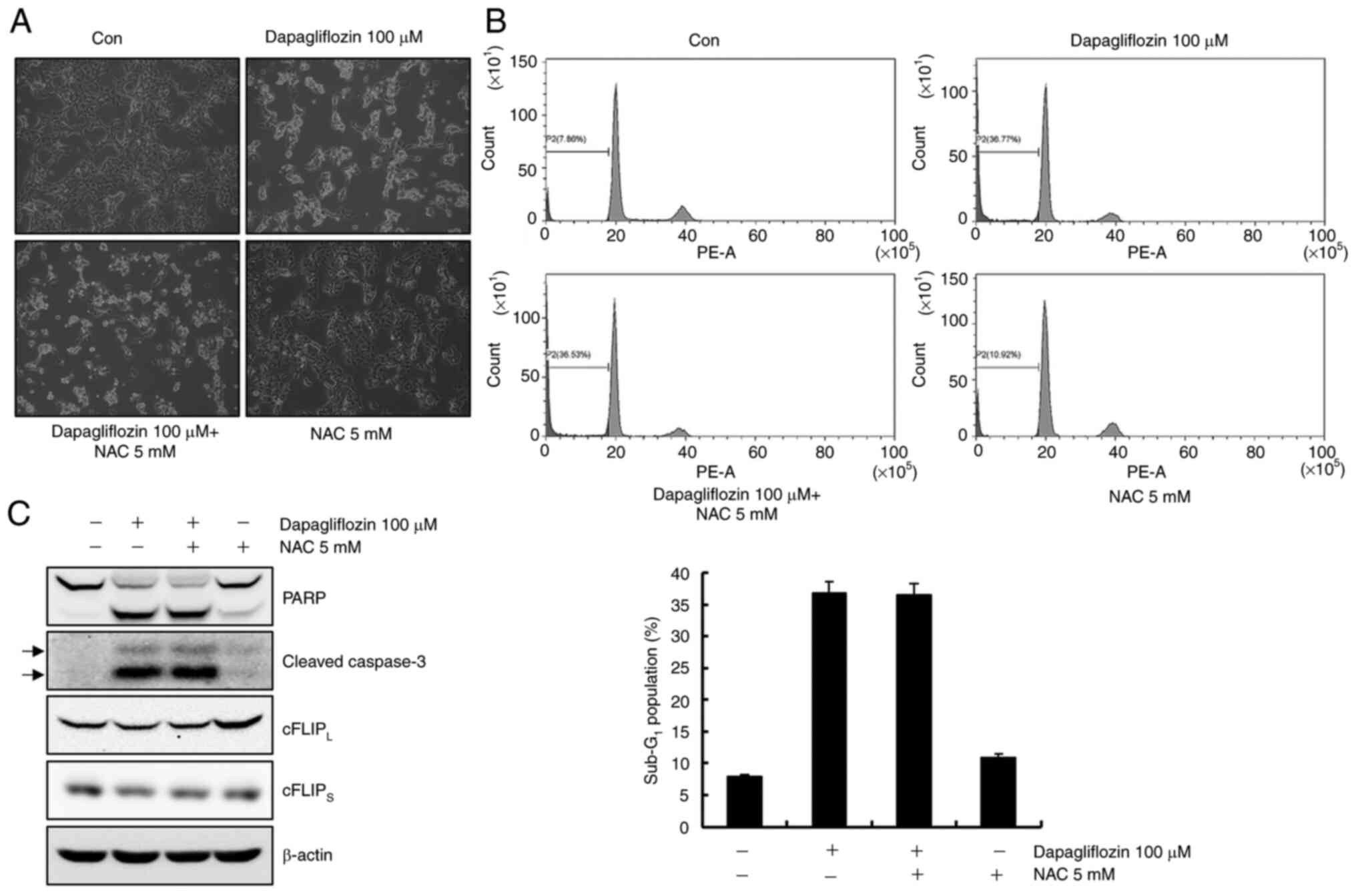

Dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is

not involved in reactive oxygen species (ROS)

ROS causes apoptosis by modulating the expression

levels of cFLIP (24). Caki-1

cells were pretreated with the ROS scavenger, NAC, for 1 h and then

cultivated with dapagliflozin for 24 h to investigate whether ROS

plays a key role in dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis. As shown in

Fig. 4A and B, pretreatment with

NAC did not prevent dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. Furthermore,

NAC failed to prevent PARP cleavage and caspase activation and did

not restore cFLIPL and cFLIPS expression

levels in dapagliflozin-treated cells (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that ROS

generation is not affected by dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis.

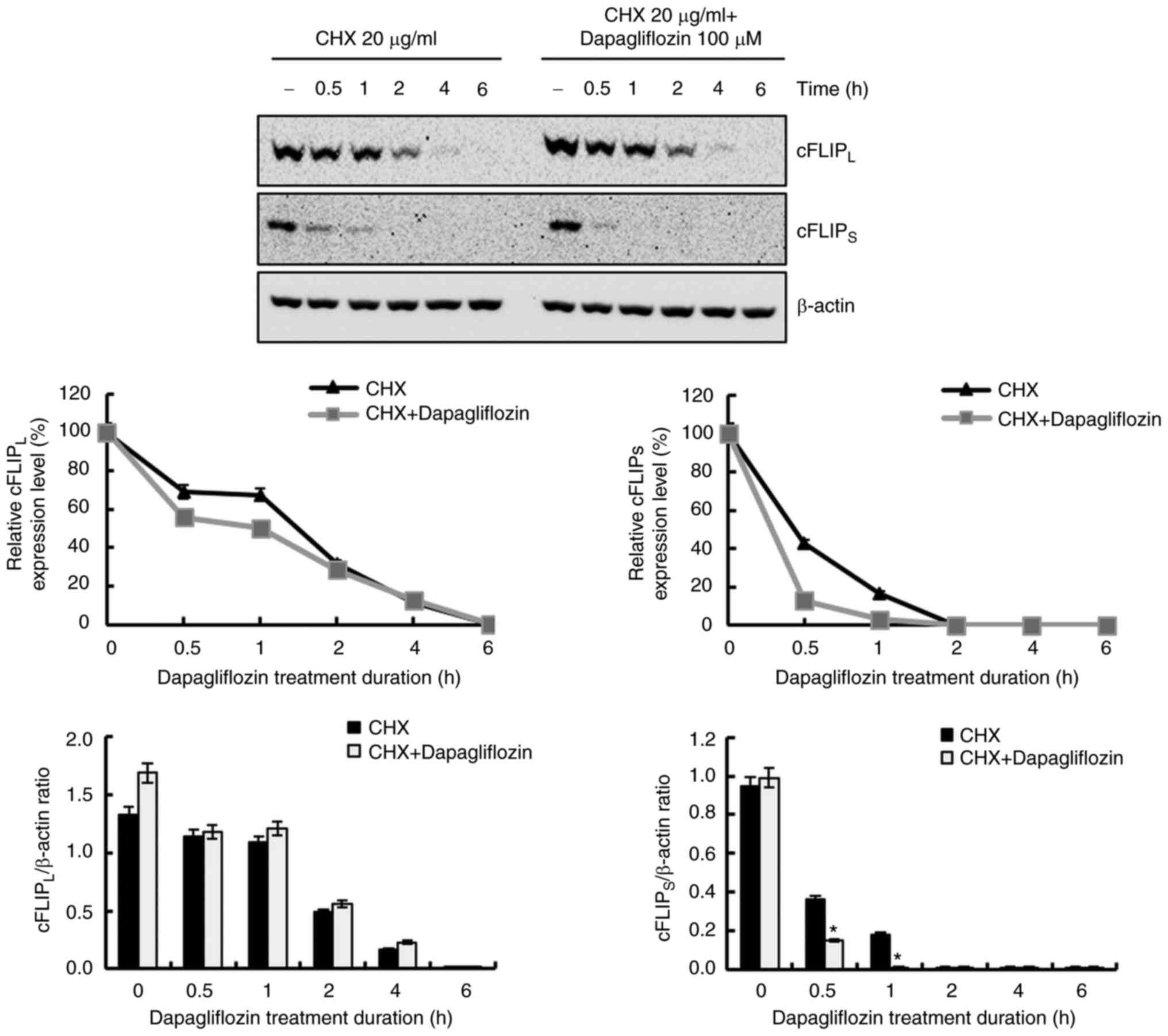

Dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is

partially recovered through cFLIPL downregulation

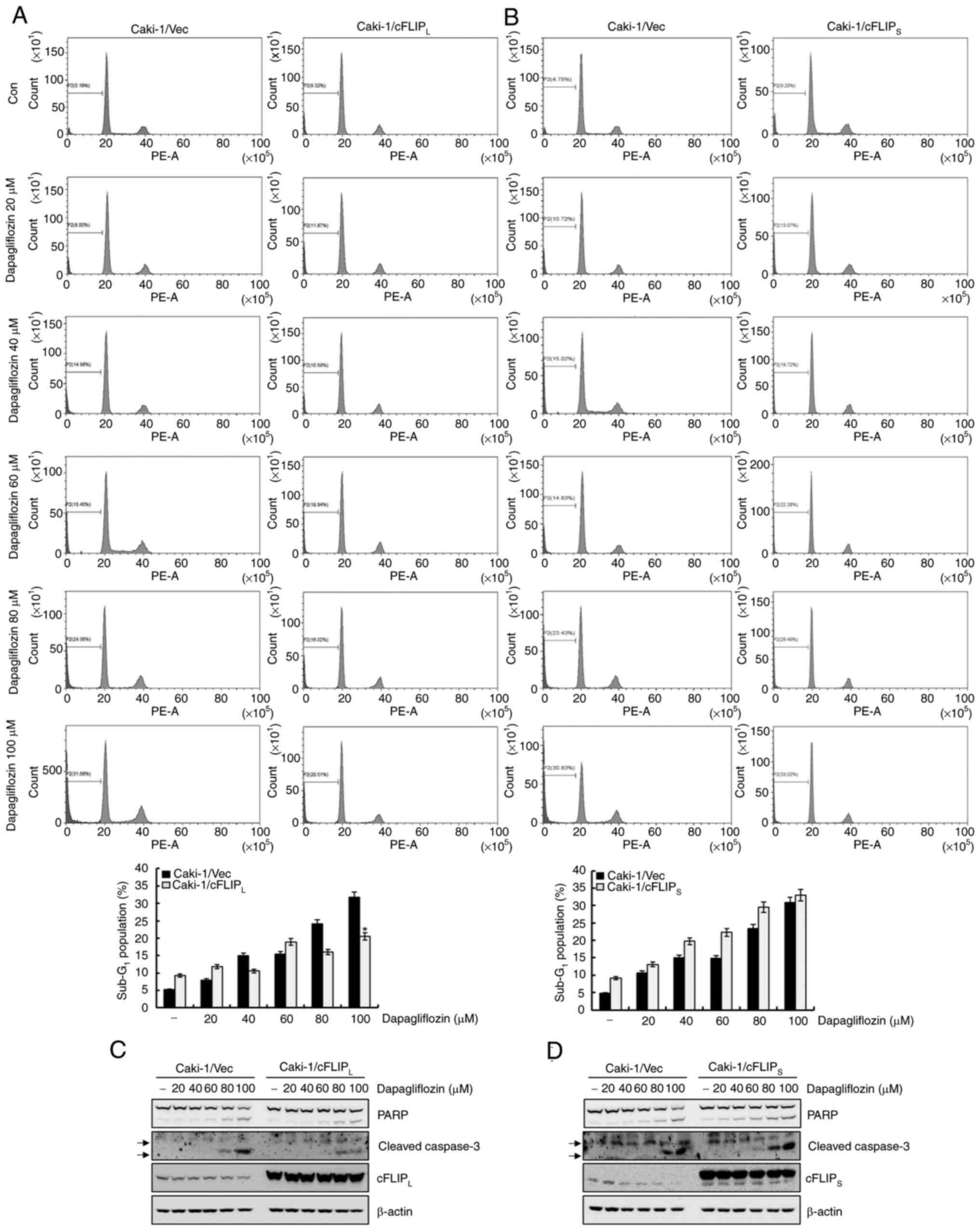

To determine whether the downregulation of

cFLIPL and cFLIPS plays an important role in

dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis in Caki-1 cells, cFLIPL-

and cFLIPS-overexpressing cells were exposed to

dapagliflozin. As shown in Fig.

5A, treatment with dapagliflozin considerably caused apoptosis

in Caki-1/vector cells, whereas overexpression of cFLIPL

partially inhibited dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. In contrast,

the overexpression of cFLIPS did not prevent

dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis (Fig.

5B). The expression of cleavage forms of PARP and caspase-3

induced by dapagliflozin treatment was partially blocked by the

overexpression of cFLIPL (Fig. 5C). However, treatment with

dapagliflozin in Caki-1/cFLIPS cells did not affect the

cleavage forms of PARP and caspase-3 expression levels (Fig. 5D). These results reveal that the

downregulation of cFLIPL contributes to

dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. In addition, dapagliflozin may

mediate apoptosis in Caki-1/vector cells and even in

cFLIPS-overexpressed cells.

| Figure 5.Downregulation of cFLIPL

contributes to dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. (A and B)

Caki-1/Vec, Caki-1/cFLIPL and Caki-1/cFLIPS

cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of

dapagliflozin. The apoptosis levels were determined based on the

sub-G1 fraction using flow cytometry. The FACS data are

indicated in the upper panels. The percentage of the

sub-G1 population is shown in the lower panels. (C)

Caki-1/vector and Caki-1/cFLIPL cells were treated with

the indicated concentrations of dapagliflozin. After 24 h, the

protein expression levels of PARP, cleaved caspase-3,

cFLIPL and β-actin were analyzed by western blotting.

(D) Caki-1/vector and Caki-1/cFLIPS cells were treated

with dapagliflozin for 24 h. Protein expression levels of PARP,

cleaved caspase-3, cFLIPS and β-actin were detected

using western blotting. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Cleaved caspase-3 is indicated by arrows. Data were acquired in

three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=3). *P<0.05 compared with dapagliflozin-treated Caki-1/Vec

cells. Vec, vector; Con, dapagliflozin 0 µM; PARP, poly

(ADP-ribose) polymerase; cFLIP, cellular Fas-associated death

domain-like interleukin-1-converting enzyme-inhibitory protein. |

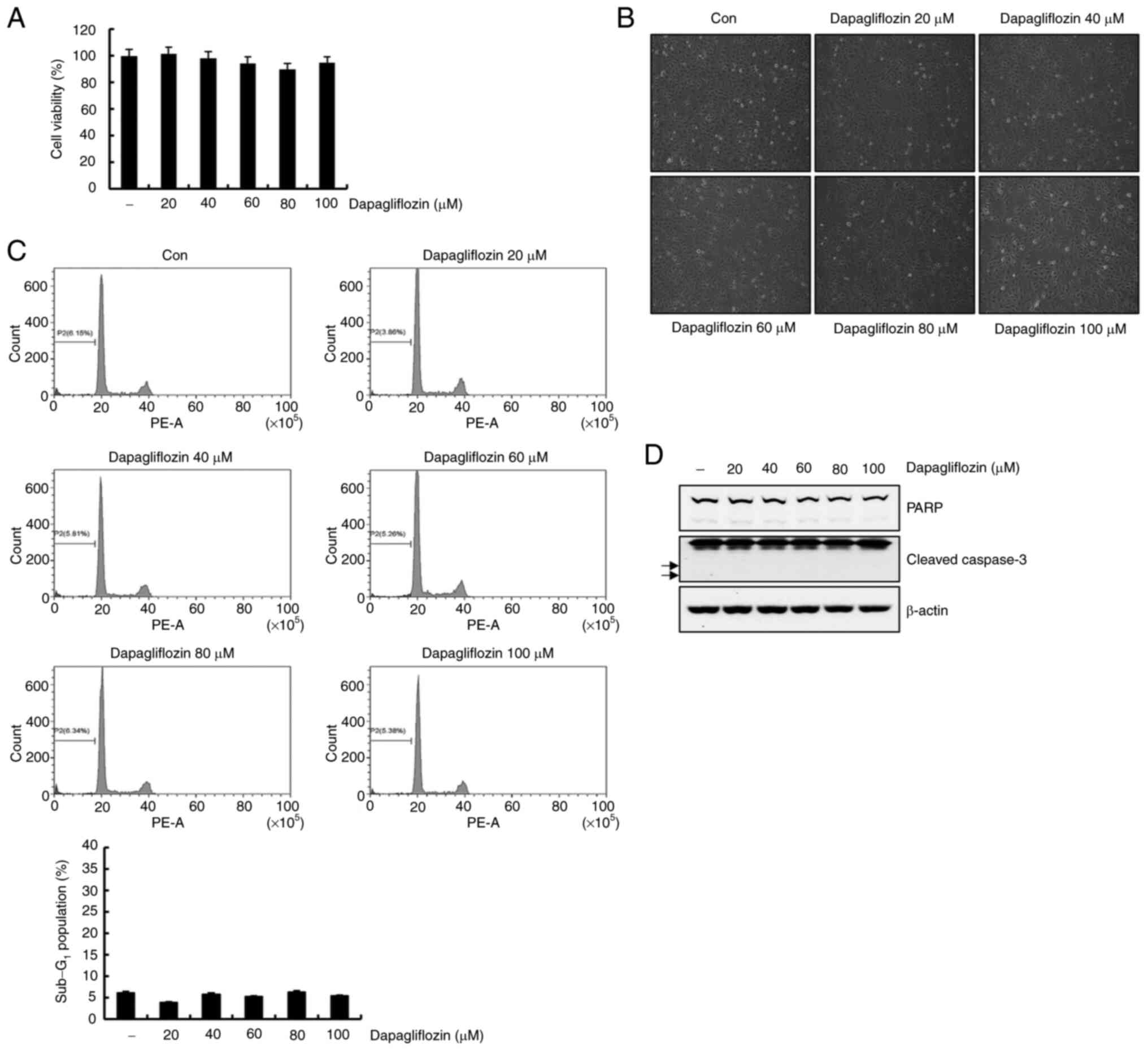

Dapagliflozin reduces the expression

level of cFLIPS ascribed by the increase in protein

instability

To further investigate the molecular mechanism

underlying the reduction of cFLIPL and cFLIPS

expression levels in dapagliflozin-treated cells, we studied

protein stability assays of cFLIPL and

cFLIPS. Treatment with dapagliflozin did not affect

cFLIPL or cFLIPS expression at the

transcriptional level (Fig. 2B).

After pretreating Caki-1 cells with CHX for 1 h, the cells were

treated with dapagliflozin for varying lengths of time; degradation

of the cFLIPS was promoted by dapagliflozin treatment,

but not by cFLIPL (Fig.

6). These findings indicate that the degradation of

cFLIPS protein is facilitated by dapagliflozin treatment

and that dapagliflozin treatment induces cFLIPS protein

instability.

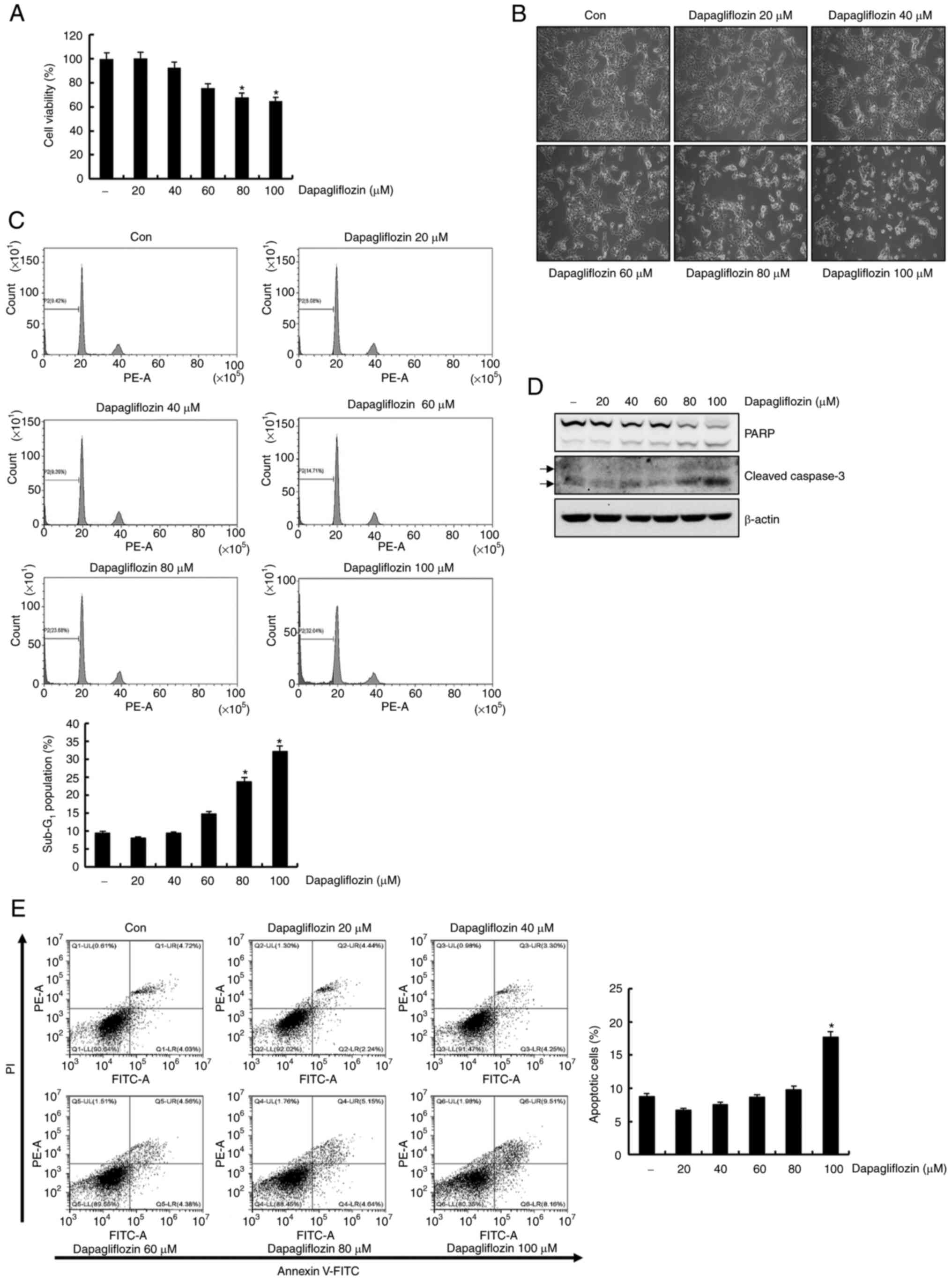

Dapagliflozin does not affect cell

death in normal human kidney HK-2 cells

We examined the effect of dapagliflozin on normal

human kidney HK-2 cells. Dapagliflozin had no effects on cell

viability and morphology (Fig. 7A and

B). Then, flow cytometry analysis of the dapagliflozin-treated

HK-2 cells was conducted. Sub-G1 population was not affected by

dapagliflozin treatment (Fig. 7C).

Additionally, protein bands of cleavage form of PARP and caspase-3

were not detected in response to dapagliflozin treatment (Fig. 7D). These data indicate that

dapagliflozin did not affect cell death in HK-2 cells.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that dapagliflozin

exerts potential anti-tumor effects on human RC Caki-1 cells.

Dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is caused by caspase signaling

pathways in Caki-1 cells. Furthermore, the detailed molecular

mechanism in dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis is associated with

caspase-mediated degradation of cFLIPL and increase of

cFLIPS instability.

Previous studies have reported that dapagliflozin

exerts anti-proliferative and anti-tumor effect (11,12).

Consistent with previous studies, our study showed that

dapagliflozin treatment significantly increased the sub-G1 fraction

in a dose-dependent manner and increased the levels of cleavage

forms of PARP and caspase-3. Annexin V/PI positive cells were

detected. These findings reveal that dapagliflozin induces

apoptosis in Caki-1 cells.

Apoptosis refers to programmed cell death related

with caspase activation (25–27).

The caspase activation is determined by the regulation of anti-

and/or pro-apoptotic proteins (28) Dapagliflozin-mediated downregulation

of cFLIPL and cFLIPS was caused by their

increased degradation, whereas protein expression levels of Bcl-2,

Bcl-xL, Bax, Mcl-1, XIAP, cIAP1 and cIAP2 were no changed. These

data indicate that dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis decreases the

expression levels of cFLIPL and cFLIPS.

cFLIP is a regulator of the apoptotic signaling

pathway and is expressed in various cancer cell lines (15,29).

Previous studies have demonstrated that cFLIP expression levels are

modulated at the proteasome-mediated post-translational level

(30,31). In this study, dapagliflozin

treatment did not alter cFLIPL and cFLIPS

mRNA levels. The findings suggest that the dapagliflozin-mediated

reduction in the cFLIPL and cFLIPS expression

levels is modulated at the post-translational level.

Caspase activation regulates apoptosis-regulatory

proteins (32,33). Previous studies have shown that

dapagliflozin does not affect caspase activation in colon cancer

cell lines (34). Contrary to

these studies, the present study showed that pretreatment with

z-VAD-fmk inhibited sub-G1 cell accumulation, cleavage forms of

PARP and caspase-3, and restored the cFLIPL and

cFLIPS expression levels. These results suggested that

dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis might be modulated by the caspase

signaling pathway through the downregulation of cFLIPL

and cFLIPS in Caki-1 cells.

Previous investigations have shown that

overexpression of cFLIP modulates apoptosis in several cancer cell

lines (35–37). In the present study, overexpression

of cFLIPL partially inhibited dapagliflozin-induced

apoptosis, while the overexpression of cFLIPS failed to

inhibit dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis. These data indicate that

dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is blocked in

cFLIPL-overexpressing cells, implying that

dapagliflozin-induced apoptosis occurs by the downregulation of

cFLIPL.

It has been reported that the downregulation of

cFLIPS is occurred by the increase in protein

instability during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced

apoptosis in human colon tumor cells (38). In the present study, reduction of

cFLIPS expression was ascribed by the increased protein

instability of cFLIPS in dapagliflozin-treated cells.

This demonstrated that dapagliflozin facilitated the degradation of

the cFLIPS, leading to increase instability of

cFLIPS.

ROS is an important apoptosis regulator in human

cancer cells (39,40). Previous studies reported that ROS

regulates cFLIP expression and increases apoptosis (41,42).

In the present study, pretreatment with of Caki-1 cells did not

inhibit dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis. These data suggest that

dapagliflozin-mediated apoptosis is independent of ROS generation.

However, recent studies have shown that dapagliflozin decreases ROS

production (43–45). Consistent with the present study,

dapagliflozin appears to be a feasible option for reducing ROS

production.

Interestingly, dapagliflozin suppresses ER

stress-induced apoptosis in normal HK-2 cells (46). In contrast, dapagliflozin did not

affect cell death in HK-2 cells in this study.

Taken together, our data indicates that

dapagliflozin–induced apoptosis is modulated by caspase signaling

pathways through the downregulation of cFLIPL and an

increase in cFLIPS protein instability in Caki-1 cells.

In conclusion, dapagliflozin is a potential chemotherapeutic agent

against human renal cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program

through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by

the Ministry of Education (grant no. 2020R1I1A1A01068857).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

JYK conceived and designed the experiments. JHJ

performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data. TJL, EGS

and IHS conducted data analyses for light microscopy, Annexin V/PI

staining and RT-PCR. JHJ drafted and wrote the manuscript. JYK

revised the manuscript accordingly. JHJ provided the funding. JHJ

and JYK confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Low G, Huang G, Fu W, Moloo Z and Girgis

S: Review of renal cell carcinoma and its common subtypes in

radiology. World J Radiol. 8:484–500. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ray RP, Mahapatra RS, Khullar S, Pal DK

and Kundu AK: Clinical characteristics of renal cell carcinoma:

Five years review from a tertiary hospital in Eastern India. Indian

J Cancer. 53:114–117. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jonasch E, Gao J and Rathmell WK: Renal

cell carcinoma. BMJ. 349:g47972014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cohen HT and McGovern FJ: Renal-cell

carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 353:2477–2490. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rabinovitch RA, Zelefsky MJ, Gaynor JJ and

Fuks Z: Patterns of failure following surgical resection of renal

cell carcinoma: Implications for adjuvant local and systemic

therapy. J Clin Oncol. 12:206–212. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang X, Zhang H and Chen X: Drug

resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug

Resist. 2:141–160. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bakris GL, Fonseca VA, Sharma K and Wright

EM: Renal sodium-glucose transport: Role in diabetes mellitus and

potential clinical implications. Kidney Int. 75:1272–1277. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mosley JF II, Smith L, Everton E and

Fellner C: Sodium-glucose linked transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors

in the management of type-2 diabetes: A drug class overview. P T.

40:451–462. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gnudi L, Coward RJM and Long DA: Diabetic

nephropathy: Perspective on novel molecular mechanisms. Trends

Endocrinol Metab. 27:820–830. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xie Z, Wang F, Lin L, Duan S, Liu X, Li X,

Li T, Xue M, Cheng Y, Ren H and Zhu Y: An SGLT2 inhibitor modulates

SHH expression by activating AMPK to inhibit the migration and

induce the apoptosis of cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett.

495:200–210. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kuang H, Liao L, Chen H, Kang Q, Shu X and

Wang Y: Therapeutic effect of sodium glucose Co-transporter 2

inhibitor dapagliflozin on renal cell carcinoma. Med Sci Monit.

23:3737–3745. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou J, Zhu J, Yu SJ, Ma HL, Chen J, Ding

XF, Chen G, Liang Y and Zhang Q: Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2

(SGLT-2) inhibition reduces glucose uptake to induce breast cancer

cell growth arrest through AMPK/mTOR pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

132:1108212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kabel AM, Arab HH and Elmaaboud MA: Effect

of dapagliflozin and/or L-arginine on solid tumor model in mice:

The interaction between nitric oxide, transforming growth

factor-beta 1, autophagy, and apoptosis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol.

35:968–978. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shirley S and Micheau O: Targeting c-FLIP

in cancer. Cancer Lett. 332:141–150. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ivanisenko NV, Seyrek K, Hillert-Richter

LK, König C, Espe J, Bose K and Lavrik IN: Regulation of extrinsic

apoptotic signaling by c-FLIP: Towards targeting cancer networks.

Trends Cancer. 8:190–209. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

He MX and He YW: A role for c-FLIP(L) in

the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis in T

lymphocytes. Cell Death Differ. 20:188–197. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bagnoli M, Canevari S and Mezzanzanica D:

Cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) signalling: A key

regulator of receptor-mediated apoptosis in physiologic context and

in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 42:210–213. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kataoka T: The caspase-8 modulator c-FLIP.

Crit Rev Immunol. 25:31–58. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Smyth P, Sessler T, Scott CJ and Longley

DB: FLIP(L): The pseudo-caspase. FEBS J. 287:4246–4260. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Poukkula M, Kaunisto A, Hietakangas V,

Denessiouk K, Katajamäki T, Johnson MS, Sistonen L and Eriksson JE:

Rapid turnover of c-FLIPshort is determined by its unique

C-terminal tail. J Biol Chem. 280:27345–27355. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Korkolopoulou P, Goudopoulou A, Voutsinas

G, Thomas-Tsagli E, Kapralos P, Patsouris E and Saetta AA: c-FLIP

expression in bladder urothelial carcinomas: Its role in resistance

to Fas-mediated apoptosis and clinicopathologic correlations.

Urology. 63:1198–1204. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ullenhag GJ, Mukherjee A, Watson NF,

Al-Attar AH, Scholefield JH and Durrant LG: Overexpression of FLIPL

is an independent marker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

patients. Clin Cancer Res. 13:5070–5075. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ryu BK, Lee MG, Chi SG, Kim YW and Park

JH: Increased expression of cFLIP(L) in colonic adenocarcinoma. J

Pathol. 194:15–19. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Azad N and Iyer AKV: Reactive oxygen

species and apoptosis. Systems biology of free radicals and

antioxidants. Laher I: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin,

Heidelberg: pp. 113–135. 2014, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jan R and Chaudhry GE: Understanding

apoptosis and apoptotic pathways targeted cancer therapeutics. Adv

Pharm Bull. 9:205–218. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Plati J, Bucur O and Khosravi-Far R:

Apoptotic cell signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Integr

Biol (Camb). 3:279–296. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Plati J, Bucur O and Khosravi-Far R:

Dysregulation of apoptotic signaling in cancer: Molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Biochem.

104:1124–1149. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Goldar S, Khaniani MS, Derakhshan SM and

Baradaran B: Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer

development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 16:2129–2144.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Longley DB, Wilson TR, McEwan M, Allen WL,

McDermott U, Galligan L and Johnston PG: c-FLIP inhibits

chemotherapy–induced colorectal cancer cell death. Oncogene.

25:838–848. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Safa AR, Day TW and Wu CH: Cellular

FLICE-like inhibitory protein (C-FLIP): A novel target for cancer

therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 8:37–46. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Oztürk S, Schleich K and Lavrik IN:

Cellular FLICE-like inhibitory proteins (c-FLIPs): Fine-tuners of

life and death decisions. Exp Cell Res. 318:1324–1331. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kiraz Y, Adan A, Yandim MK and Baran Y:

Major apoptotic mechanisms and genes involved in apoptosis. Tumour

Biol. 37:8471–8486. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pfeffer CM and Singh ATK: Apoptosis: A

target for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 19:4482018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Saito T, Okada S, Yamada E, Shimoda Y,

Osaki A, Tagaya Y, Shibusawa R, Okada J and Yamada M: Effect of

dapagliflozin on colon cancer cell [Rapid Communication]. Endocr J.

62:1133–1137. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu X, Yue P, Schönthal AH, Khuri FR and

Sun SY: Cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein down-regulation

contributes to celecoxib-induced apoptosis in human lung cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 66:11115–11119. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen S, Liu X, Yue P, Schönthal AH, Khuri

FR and Sun SY: CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous

protein-dependent death receptor 5 induction and

ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein

down-regulation contribute to enhancement of tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by

dimethyl-celecoxib in human non small-cell lung cancer cells. Mol

Pharmacol. 72:1269–1279. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin Y, Liu X, Yue P, Benbrook DM, Berlin

KD, Khuri FR and Sun SY: Involvement of c-FLIP and survivin

down-regulation in flexible heteroarotinoid-induced apoptosis and

enhancement of TRAIL-initiated apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Mol

Cancer Ther. 7:3556–3565. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mora-Molina R, Stöhr D, Rehm M and

López-Rivas A: cFLIP downregulation is an early event required for

endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell

Death Dis. 13:1112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yodkeeree S, Sung B, Limtrakul P and

Aggarwal BB: Zerumbone enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the

induction of death receptors in human colon cancer cells: Evidence

for an essential role of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res.

69:6581–6589. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sheikh BY, Sarker MMR, Kamarudin MNA and

Mohan G: Antiproliferative and apoptosis inducing effects of citral

via p53 and ROS-induced mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in human

colorectal HCT116 and HT29 cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother.

96:834–846. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kanayama A and Miyamoto Y: Apoptosis

triggered by phagocytosis-related oxidative stress through FLIPS

down-regulation and JNK activation. J Leukoc Biol. 82:1344–1352.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Nitobe J, Yamaguchi S, Okuyama M, Nozaki

N, Sata M, Miyamoto T, Takeishi Y, Kubota I and Tomoike H: Reactive

oxygen species regulate FLICE inhibitory protein (FLIP) and

susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis in cardiac myocytes.

Cardiovasc Res. 57:119–128. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Uthman L, Homayr A, Juni RP, Spin EL,

Kerindongo R, Boomsma M, Hollmann MW, Preckel B, Koolwijk P, van

Hinsbergh VWM, et al: Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin reduce ROS

generation and restore NO bioavailability in tumor necrosis factor

α-stimulated human coronary arterial endothelial cells. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 53:865–886. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hu Y, Xu Q, Li H, Meng Z, Hao M, Ma X, Lin

W and Kuang H: Dapagliflozin reduces apoptosis of diabetic retina

and human retinal microvascular endothelial cells through

ERK1/2/cPLA2/AA/ROS pathway independent of hypoglycemic. Front

Pharmacol. 13:8278962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Leng W, Wu M, Pan H, Lei X, Chen L, Wu Q,

Ouyang X and Liang Z: The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin attenuates

the activity of ROS-NLRP3 inflammasome axis in steatohepatitis with

diabetes mellitus. Ann Transl Med. 7:4292019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Shibusawa R, Yamada E, Okada S, Nakajima

Y, Bastie CC, Maeshima A, Kaira K and Yamada M: Dapagliflozin

rescues endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cell death. Sci Rep.

9:98872019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|