Forkhead box K2 (FOXK2), a central transcriptional

regulator of embryonic development and cell homeostasis, was

initially recognized as an essential member of the FOX family.

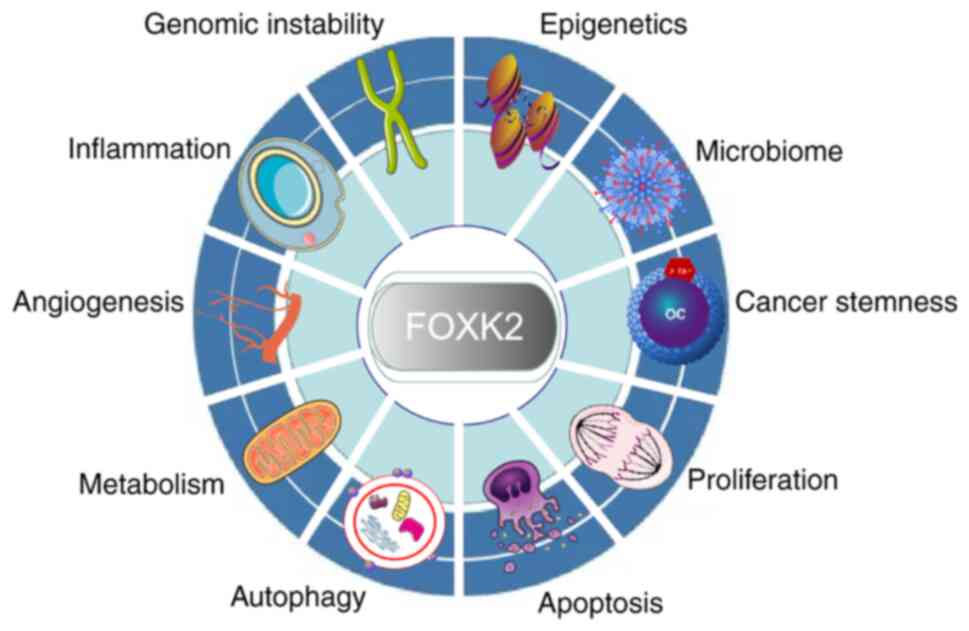

Since its identification, evidence available has shown that FOXK2

mediates a diverse range of biological processes, such as cancer

genetics and biology (1–4). However, the biological functions of

FOXK2, especially functional redundancy and non-functional

redundancy, remain largely unexplored. Functional redundancy is a

property of transcription factors (TFs) that allows one TF to

compensate for another due to their protein sequence homology, or

the shared molecular chaperone (5–7).

Non-functional redundancy of TFs serves a more important role in

the cell fate conversions. Thus, loss of FOXK2 function or the

absence of gain-of-function, directly and indirectly, affect

tumorigenesis. Over the past 30 years, the hallmarks of cancer are

defined as the collection of acquired biological capabilities

during the multistep development of human tumors (8–10).

It is well known that TFs are actively involved in the acquisition

of biological capabilities in human tumors. As, to date, there is

neither commercially available FOXK2 inhibitors/drugs nor

convincing clinical trials of its use as a therapeutic target, the

present review outlined the broad roles and possible mediating

mechanisms of FOXK2 in carcinogenesis. Finally, it highlighted that

the functional redundancy and non-functional redundancy of FOXK2

maps to tumor pathogenesis. This relationship may influence the

direction of future FOXK2 research in tumorigenesis.

FOXKs are members of an evolutionarily conserved TF

family that share a forkhead DNA-binding domain with their binding

partners. The binding occurs at a conserved core sequence

(TTGTTTAC) and mediates various chromatin events (11–14).

For example, FOXK2 recognizes and binds to a purine-rich motif in

the long terminal repeats of the human immunodeficiency virus and

is identified as an interleukin-enhancing factor-binding factor

(ILF). This behavior was demonstrated in a study of genes encoding

cytokines (15).

The role of alternative splicing in cancer is

multifaceted and the activity of tumor suppressors and oncogenes is

altered by alternative splicing (20,21).

These changes are preferentially found in cancer cells and often

manifest at the protein level as structural changes (22), removal of phosphorylation sites

(23), or changes in subcellular

localization (24). As with most

human genes, FOXK2 mRNA undergoes some degree of alternative

splicing (25) and three isomers

have been identified. The three isomers, termed ILF-1, ILF-2 and

ILF-3, encode proteins with lengths of 655, 609 and 323 amino

acids, respectively. The GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) labels them as

FOX protein K2 isoforms X1, X2 and X3.

Structurally, all three proteins contain a signature

proline-rich FHA domain. However, in contrast to ILF-1 and ILF-2,

which contain a complete forkhead domain (FKH), ILF-3 contains a

partially missing FKH (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Although the

significance of the complete FKH domain existence or absence is

unclear, ILF-3 does lose the majority of potential phosphorylation

sites in the COG5025 (GenBank, Ser180 to Gln577) region (26). There is evidence that alternative

splicing alters protein phosphorylation, thereby limiting the

effect of the kinase cascade signal (27–30).

However, there is still a lack of research data on FOXK2

alternative splicing. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by

sequencing (ChIP-seq) allows analysis of chromatin binding to TF

and this particular technique may help answer a number of open

questions about FOXK2 functions. The function of FOXK2 proteins is

also closely related to their dynamic allocation in different

subcellular structures. Therefore, understanding this new aspect

and studying the regulatory mechanism help to elucidate its dynamic

transcriptional role in mRNA expression of target genes. This

understanding is critical to evaluating how it promotes health and

disease (28,31).

The NLS is a motif that allows for active nuclear

import of large proteins. However, the nuclear translocation of

certain proteins does not appear to be dependent on the NLS of

FOXK2. For example, FOXK2 mediates Disheveled (DVL) nuclear

translocation according to its FHA and adjacent region (residue

Arg129-Pro171) (32). Thus, there

is no credible evidence to support the effect of NLS on FOXK2

functionality.

Over the past decade, the unexpected functional

redundancies and non-functional redundancies of FOXK2 have become

increasingly attractive prospects for researchers to explore. There

is growing evidence that FOXK2 serves a vital role in various

biological processes, especially in cancer cells, including in

proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis

and metabolic reprogramming.

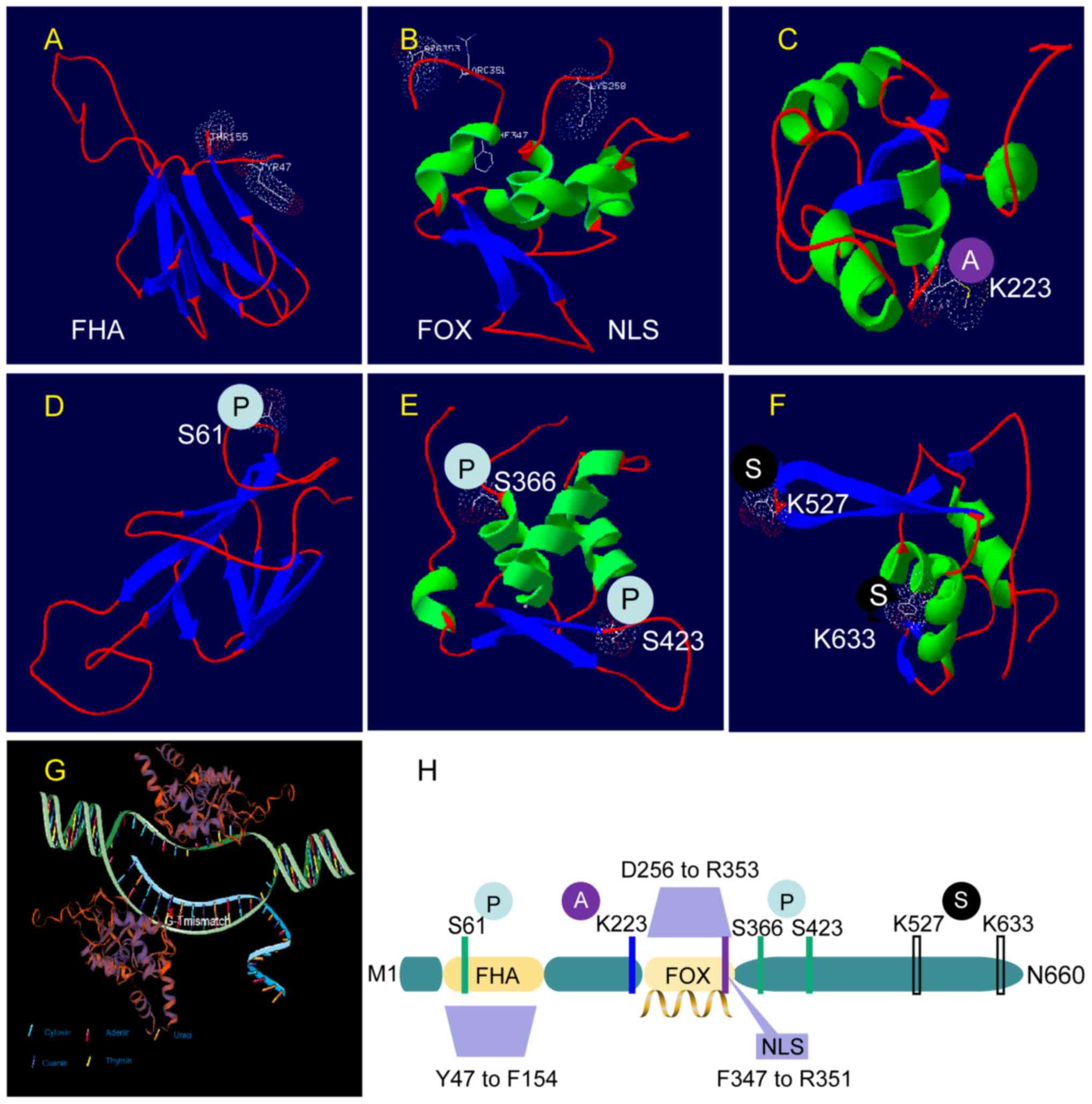

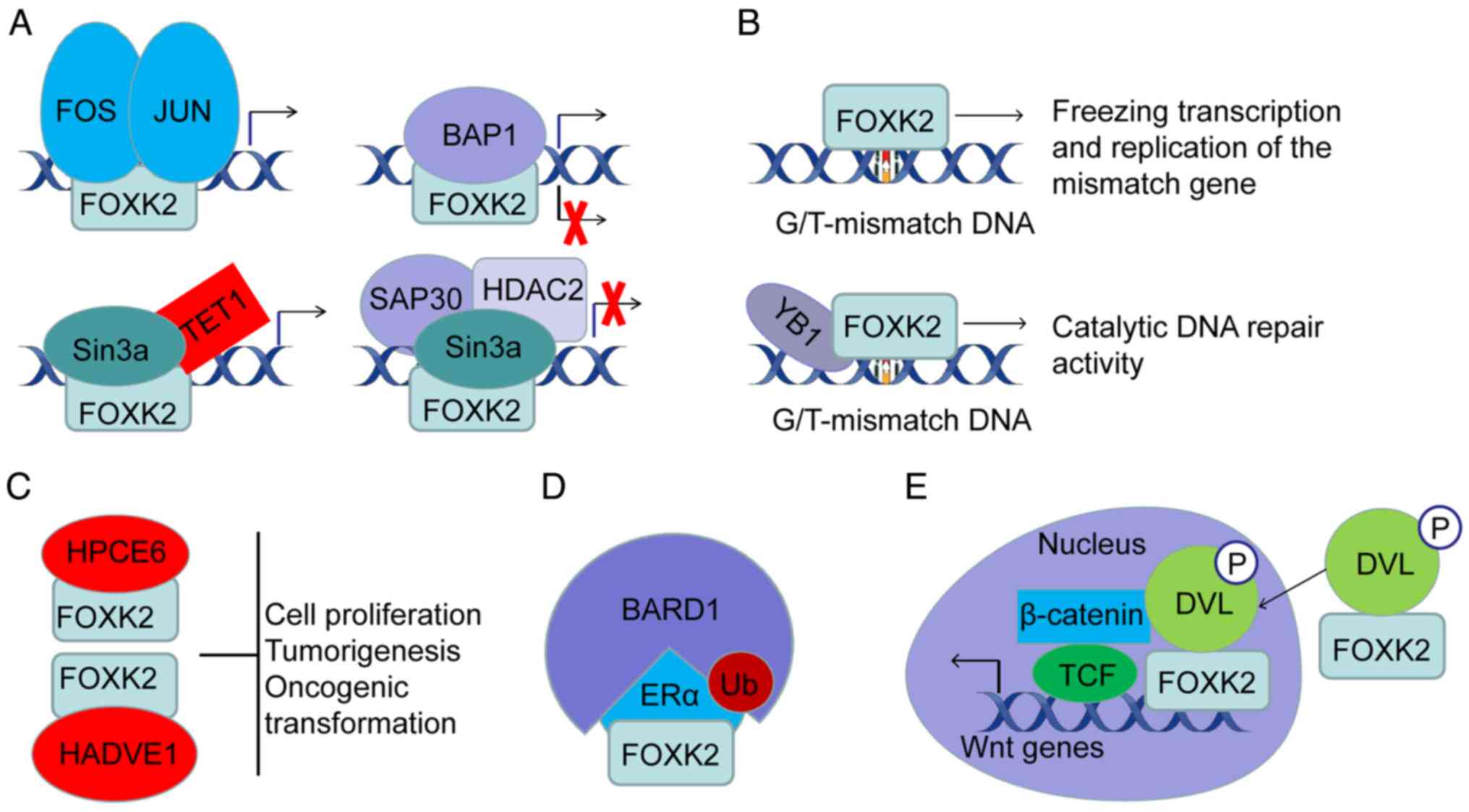

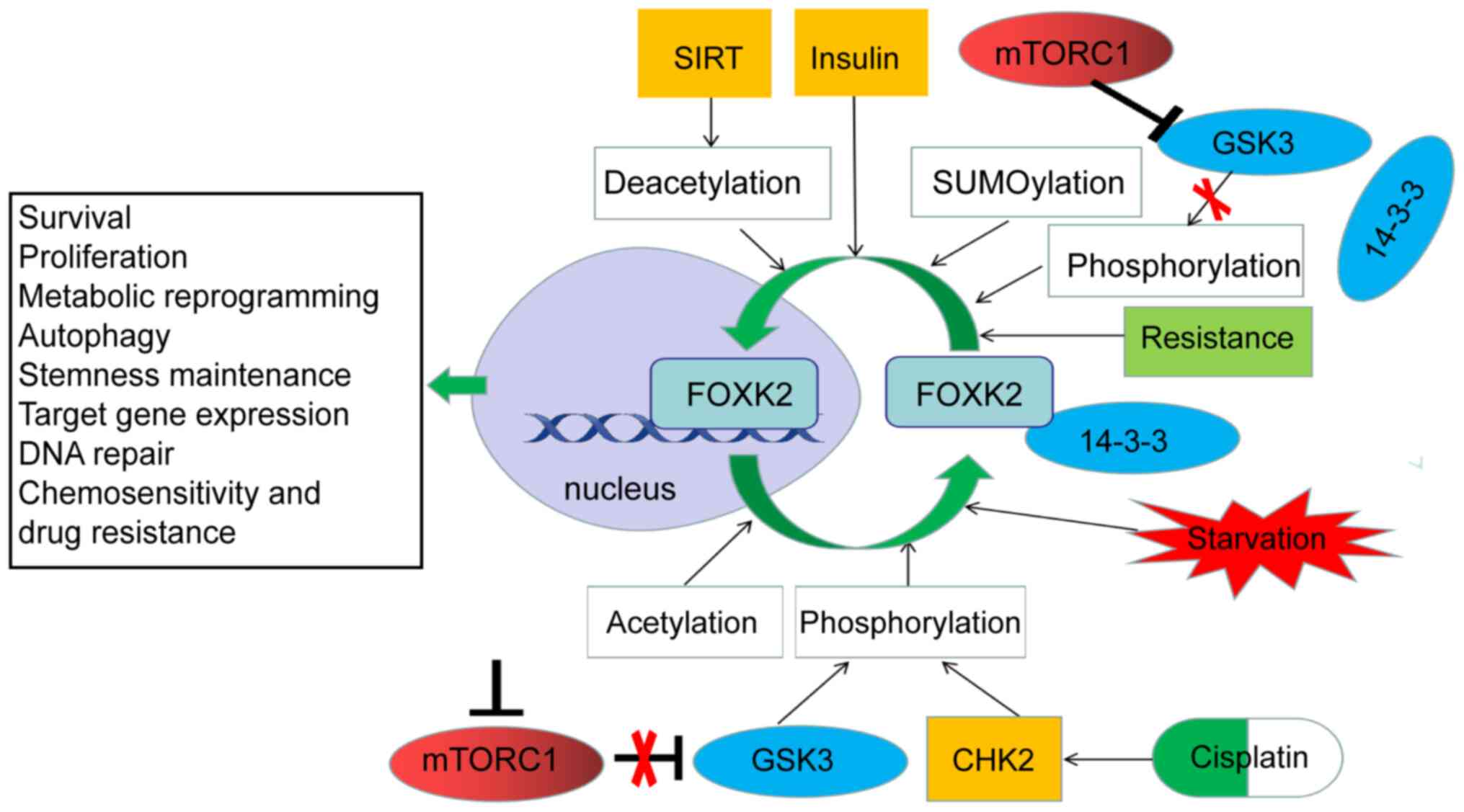

The regulation of FOXK2 activity has been

extensively studied. In addition to regulation of mRNA expression,

post-translational modifications (PTMs; Fig. 1), non-coding RNA (ncRNAs) and

protein interactions also serve important roles in the loss or gain

of FOXKs functions (4,33) (Fig.

2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). PTMs affect the stability of

transcriptionally active proteins. PTMs also control how these

proteins interact with other molecules and serve different roles in

various developmental processes in both internal and external

settings, whether favorable or unfavorable (34–39).

The most common PTMs are glycosylation modification,

phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination,

sulphuration and reduction/oxidation (redox) modifications

(40). Notably, epigenetic

mechanisms including DNA cytosine modifications, histone

modifications and regulation by ncRNAs are prominent epigenetic

regulatory elements (41,42).

DNA methylation is an evolutionarily ancient

epigenetic modification that regulates FOXKs at the transcriptional

level (43,44). These epigenetic modifications are

closely associated with the aging process and regulate the

transcriptional profile of DNA fragments by packaging them

(43,44).

A considerable body of evidence suggests that ~1% of

the human genome is methylated and methylated markers of gene

promoter regions control gene expression (45–47).

In addition, DNA methylation has been implicated in mediating

transcriptional silencing, although the particular molecular

pathways are not fully understood (48). Transcriptional silencing serves a

vital role in critical biological processes such as replication,

division, development survival, aging, genomic imprinting and

embryonic development as facultative chromatin, especially in

cancer development (49–54).

Several studies have demonstrated a preference for

methylated markers for genomic site selection (55–57).

Methyl groups are attached to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) throughout the

genome, typically between cytosine and guanine (CpG) or within CpG

islands polymerized by CpGs (55).

This finding was further exemplified in a global causal analysis

involving firefighters exposed to various environmental hazards. As

expected, this controlled analysis revealed differential

methylation loci in FOXK2. Three CpG loci in FOXK2

were shown to be located in CpG islands and they exhibited reduced

methylation (56).

FOXK2 is an effector of DNA methylation. FOXK2

methylation is a meaningful indicator of fertility. High levels of

FOXK2 methylation are closely associated with male infertility

(58). Furthermore, FOXK2

hypomethylation induced by dioxin exposure can also negatively

affect male reproductive health (59).

The effect of FOXK2 methylation can also be observed

in the following examples of interaction with a range of

environmental factors. A recent study analyzed genome-wide DNA

methylation profiles of white blood cells. It found that FOXK2

hypermethylation levels were strongly associated with smoking

levels and also varied across racial/ethnic groups (60). Notably, hypermethylation can be

observed in patients with severe psychophysiological trauma

(61) and arsenic toxicity in

vivo (62). The potential

implication of this meaningful evidence is that FOXK2 methylation

levels are associated with physiological stresses caused by

environmental exposure. However, there is a lack of research on the

relationship between changes in FOXK2 methylation levels and

psychological stress and toxic transformation.

There is also considerable interest towards

understanding the effects of certain lifestyle factors on FOXK2

methylation modification. In CpG islands of adipose tissue,

methyltransferase nicotinamide n-methyltransferase (NNMT) levels

are influenced by diet and exercise. FOXK2 methylation levels are

inversely correlated with NNMT (57), further supporting the link between

environment and methylation levels.

Abnormal increases in methylation are associated

with the inactivation of tumor related genes (63,64).

A study examining genome-wide DNA methylation profiles of

fibromatoid-like fibroma tumors involving FOXK2 showed that

hypermethylation reduced FOXK2 mRNA expression (65).

Additionally, FOXK2 has also been identified as a

dynamic reader of DNA methylation, mediating the interaction of

methylated binding domain (MBD) deficient transcription factors

with methylated DNA (66,67). Several specific homologous

framework proteins and proteins with wing-like helix domains,

including FOXK2, can recognize methylated CpG (mCpG) (66,68,69).

FOXK2 has been shown to bind methylated DNA 5mC and the oxidative

derivative 5-formylcytosine to recruit relevant functional proteins

in mouse embryonic stem cells (66,67).

Although FOXK2 can be used for MBD screening and serves an

important role in coordinating transcriptional replication and DNA

repair, it is not clear how a number of MBD-deficient TFs might be

recruited by FOXK2 (70).

The dynamic regulation of phosphorylation is

undoubtedly the most common and well-studied PTM (71,72).

Phosphorylation with rapid and reversible properties profoundly

modulates a wide range of proteins at a relatively small dynamic

cost, controlling the balance between phosphorylation and

dephosphorylation events (73,74).

The unique FHA domain of FOXK2 makes it an

‘intelligent’ sensor in complex networks related to cell signal

cascades. It contributes to genomic stability, cell growth

maintenance, cell cycle regulation and signal transduction

(75). These functions have been

partially validated in yeast. The yeast FOX proteins Fkh1 and Fkh2

(homologs of human FOXK1 and FOXK2 proteins) are phosphorylated by

Cdc28p, the primary cycle-dependent kinase in yeast, in a cell

cycle-dependent manner (76,77).

Changes in Fkh2 activity can affect pseudomycelia growth through

transcriptional regulation of genes involved in M-phase transition

(76). The cyclin-dependent kinase

1 (CDK1) phosphorylates FOXK2 at Ser368 and Ser423 in the COG5025

domain. The phosphorylation fluctuates periodically and reaches its

peak in the M phase (26). In

human osteosarcoma cells, CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of FOXK2

(S368/S423) negatively regulates its stability and inhibitory

activity and thus inhibits tumor cell apoptosis (26).

Additionally, phosphorylation exerts a regulatory

effect by modulating the subcellular localization and translocation

of FOX family members and also regulates their interaction with

chaperone proteins (78–80), such as 14-3-3, a hub-protein of

complex network of protein-protein interaction that has several

hundred identified protein interaction partners and is therefore

involved in cellular processes and diseases (81). A recent study on autophagy showed

that ataxia-telangiectasia mutation (ATM) mediates phosphorylation

of checkpoint kinase 2 protein (CHK2) at Thr68 after DNA damage,

which is critical for binding to the FHA domain of FOXK. This

binding enables FOXK1 and FOXK2 to be phosphorylated by CHK2 at

Ser130 and Ser61, respectively. Then, the phosphorylated FOXK

protein is captured in the cytoplasm by 14-3-3γ and this affects

the transcription of autophagy-related (ATG) genes (1). Phosphorylation-induced subcellular

localization affecting cell metabolic reprogramming has also been

demonstrated. By blocking mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and then

eliminating its inhibitory effect on glycogen synthase kinase 3,

both FOXK1 phosphorylation and its interactions with 14-3-3 ε are

increased, resulting in reduced expression of multiple genes

involved in glycolysis related pathways (2). However, whether all 14-3-3 subtypes

or some of them indiscriminately trap FOXK2 remains unclear.

Nutrition-related signals such as insulin and amino acids activate

mTORC1 to induce protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)-mediated

dephosphorylation of the FOXK1 (82). This effect reduces the production

of insulin-induced C-C chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) (83). FOXK1 and FOXK2, like their FOXO

subfamily partners, are downstream targets of insulin action

(82). However, unlike FOXO1,

insulin stimulation directs the translocation of FOXK proteins from

the cytoplasm to the nucleus in an AKT-mTOR pathway-dependent

manner (84). This translocation

controls the expression of genes involved in regulating

mitochondrial β-oxidation and biogenesis in the nucleus (85). Descriptions of FOXK2 translocation

between nucleus and cytoplasm are helpful in understanding the

functions of FOXK2 in signal transduction and gene expression

regulation, but studies on this shuttle mechanism are scarce.

It is important to note that although some studies

only investigated FOXK1, the results have practical reference

significance for FOXK2 due to their high degree of similarities in

the domain and protein sequence, with amino acid homology

approaching 50% (86,87). Furthermore, studies on the

clustering of FOXK1 and FOXK2 samples support the hypothesis of

functional overlap of FOXKs. For example, one study found that

single and double knockdowns of FOXK1/FOXK2 upregulated the

expression of apoptosis-related genes and downregulated the

expression of genes related to cell cycle and lipid metabolism

(84). Additionally, FOXK1 and

FOXK2 have a significant positive effect on the regulation of

glycolysis, as they share a common regulatory substrate preference

(glucose and fatty acid) and can upregulate the expression of

enzymes required in glycolysis, which in turn regulate lactic acid

production (88).

In addition to the examples mentioned above, in

FOXK1 knock-out (KO) cells, several genes that participate in

hormone biosynthesis, monoamine transport regulation, hematopoietic

stem cell differentiation and integrin activation are

downregulated. This gene regulatory profile is similar to that of

FOXK2 KO cells, suggesting functional similarities between FOXK1

and FOXK2 in regulatory targets (89). However, the extent to which they

cause physiological or pathological overlap, as well as

non-redundant functions, remain to be elucidated.

Several studies have shown that FOX-protein

stability, DNA binding activity and interactions with chaperones

are also regulated by SUMOylation (90–94).

These regulatory activities are well represented in breast cancer

cells, where FOXK2 SUMOylation serves a key role in mediating

chemical sensitivity and resistance to paclitaxel. Paclitaxel

treatment of breast cancer cells requires the SUMOylation of FOXK2

at the K527 and K633 sites for their cytotoxic function. The

SUMOylation of FOXK2 significantly increased its binding to the

FOXO3 promoter, leading to upregulation of FOXO3 mRNA and

protein levels. Conversely, FOXK2 accumulates in the nucleus of

paclitaxel-resistant breast cancer cells, but recruitment to

endogenous FOXO3 promotors is impaired (95). FOXK2 does this by dynamically

regulating subcellular localization and binding to target genes

such as tumor suppressor FOXO3. However, the more detailed

regulatory mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

The mechanisms of ubiquitination have been

extensively studied. Ubiquitination primarily consists of

mono-ubiquitination and polyubiquitination and it regulates a

diverse range of physiological and pathological activities

(96,97). Ubiquitination and deubiquitination

events of substrate proteins have significant effects on several

aspects of cell life, such as cell cycle regulation, apoptosis,

receptor downregulation and gene transcription (98–100). The ubiquitin-proteasome system

include ubiquitin ligases (E1, E2 and E3), proteasomes and

deubiquitination enzymes (DUBs) (96,97).

The unique roles that these proteasomes and enzymes serve in tumor

inhibition and tumor inhibition pathways are well documented, such

as in tumor metabolism regulation, immune tumor microenvironment

(TME) regulation and cancer stem cell maintenance (101).

The PcG-repressive (PR)-DUB complex catalyzes the

deubiquitination of H2A at lysine 119 (102). Although several models for the

PR-DUB complex's inhibitory function have been reported, how it

mediates gene inhibition is still not fully understood (103–106). FOXK1 and FOXK2 are considered to

be indispensable components of three mammalian PR-DUB complexes,

including breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1)

associated protein-1 (BAP1, homolog of human Calypso), host cell

factor C1 (HCFC1) and additional sex combs-like proteins (103). Notably, BAP1 DUB has been

reported to function as a FOXK2 chaperone in human cells in a FOXK2

FHA-dependent manner (107).

Furthermore, BAP1 functions as an important tumor suppressor

protein in several different tumor types and can deubiquitinate

histone H2A to regulate transcription (108–110). In the absence of BAP1, FOXK2

fails to recruit BAP1, losing the ability to inhibit oncogenesis by

directing BAP1 to its target gene (111). The relationships between the

various components of the PR-DUB complex have been extensively

studied. However, the link between FOXK2 and enzymes responsible

for regulating protein O-GlcNAc modification, including OGT and

glycoside enzyme (O-Glcnase, OGA), has not been adequately

studied.

Acetylation is involved in almost all cellular

biological processes, including cancer. FOXK2 can affect the

acetylation of proteins of interest and the transcription of target

genes. A study of the FOXK proteins in hunger-induced atrophy and

initiation of autophagy found that FOXK1 and FOXK2 restrict the

acetylation of the target genomic protein H4 and the expression of

essential autophagy genes. FOXK1 and FOXK2 achieve this restriction

by recruiting the suppressor-interacting 3A (Sin3a) histone

deacetylation enzyme (HDAC) complex (85). There is also evidence that FOXK2,

as a transcription inhibitor, can interact with proteins in the

Sin3a HDAC co-inhibitory complex in human cells (105). Despite growing evidence of

non-histone acetylation affecting a range of cellular processes

(112,113), the regulatory role of lysine

acetylation in cancer cells remains to be elucidated. Lysine

residue in FOXK2 can also be modified by acetylation. The

acetylation levels at the K223 site in FOXK2 are directly related

to the sensitivity of tumor cells to cisplatin. In cancer cells,

cisplatin can enhance the acetylation of FOXK2 K223, reduce the

nuclear distribution of FOXK2, significantly downregulate the

expression of cell-cycle-related genes and significantly upregulate

the expression of apoptosis-related genes. FOXK2 K223

hyperacetylation can even promote mitotic catastrophe (114). However, in cisplatin-treated

cancer cells, the silencing of information regulator 2-related

enzyme 1 reduces the effect of deacetylation of FOXK2 K233 on cell

apoptosis (114). This finding

has far-reaching implications for understanding chemical

sensitivity and drug resistance in cancer and warrants further

in-depth studies in the future.

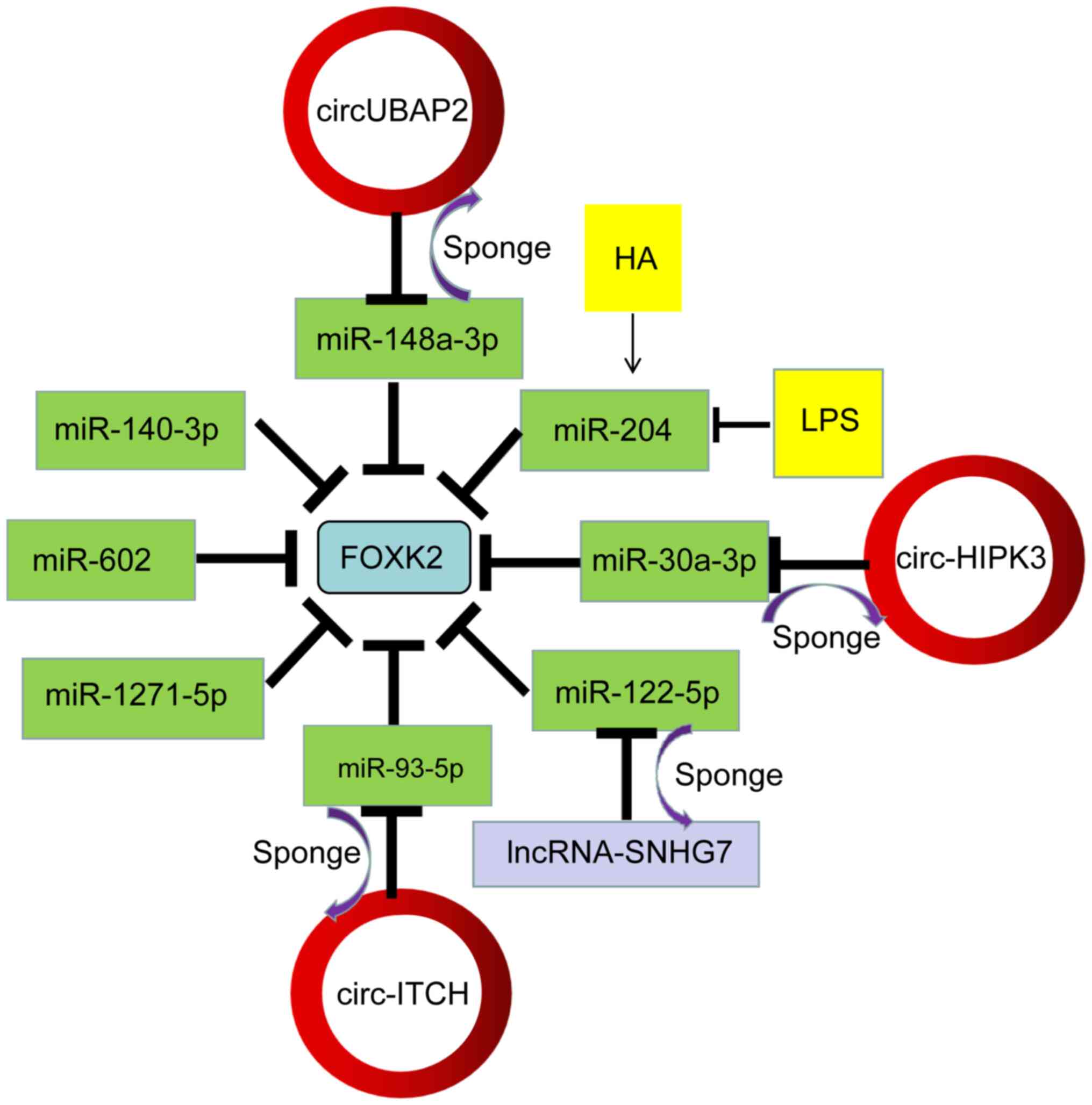

Thanks to rapid advances in sequencing technologies,

several unique ncRNA sequences have been identified. MicroRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs), circular RNAs (circRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs)

control numerous molecular targets, mediate cellular processes and

determine cell fate (115,116).

ncRNAs are RNA molecules lacking protein-coding

regions responsible for regulating gene expression at the

transcriptional or post-transcriptional level (117–120). These functional regulators link

relevant genes into regulatory networks, with some ncRNAs, such as

miRNAs and lncRNAs, possibly regulating the mRNAs of several target

genes. Moreover, the mRNA of a specific gene can be regulated by

multiple miRNAs (121,122). Notably, some ncRNA crosstalk

imparts robustness to biological processes, supporting their role

as crucial regulators. The noise of these complex interactions can

profoundly impact cell fate, especially in cancer (121,123).

miRNAs are endogenous and abundant. They are RNA

sequences that are ~22 nucleotides long and can be associated with

the corresponding miRNA response elements (124,125). These miRNAs, composed of 18–25

nucleotides, bind with other proteins to form RNA-induced silencing

complexes that target the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of mRNA.

This function regulates the translation of mRNAs involved in

biological processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis,

differentiation and transformation (126–129). In a study involving granulosa

cells (GC), miR-204, a downstream regulator of the phospho-inositol

3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, directly targets FOXK2

and results in promoting GC proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis

(130). In hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC), FOXK2 is a direct target of miR-1271, which

negatively regulates FOXK2 at the mRNA and protein levels (131). A study assessing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation in non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) confirmed that the FOXK2 3′-UTR site

(position 40–47) (GUGCCAA) is directly targeted and negatively

regulated by miR-1271 (132).

Notably, miRNAs that regulate FOXK2 are affected by

epigenetic and environmental changes. In various esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) studies (133,134), hypomethylation of the miR-602

promoter induced expression and negatively regulated the target

gene FOXK2. It regulated the cell cycle by promoting the

proliferation and metastasis of ESCC in vitro and in

vivo. Notably, reduced FOXK2 expression significantly

accelerated the biological pathway mediated by miR-602

overexpression (134).

Some metabolic substrates and drugs also induce

miRNA expression. Under high glucose conditions, the expression of

miR-140-3p in endothelial cells (ECs) was significantly decreased.

The low level of miR-140-3p lost the inhibitory effect on the

expression of FOXK2, thereby enhancing the angiogenic function of

ECs (135). In hirsutanol A

(HA)-pretreated A549 cells, upregulation of miR-204 directly

targets FOXK2, promoting cell viability by reducing apoptosis and

inhibiting the release of inflammatory factors by attenuating NF-κB

activation (136).

circRNAs possess a continuous loop of at least a few

hundred nucleotides and a covalently closed loop, resulting in a

higher degree of stability compared with most linear RNAs (137,138). Ashwal-Fluss et al showed

that circRNAs are produced through co-transcription and competition

with conventional splicing (139). Several circRNAs are closely

associated with tumor development and progression; however, the

details of their regulatory mechanisms remain inconclusive

(140–142). Intriguingly, two studies

conducted in 2013 showed that two circRNAs, CDR1-as (also known as

CIRS-7) and sex-determining region Y (Sry), act as sponges for

miRNAs that regulate transcription of specific miRNAs (143,144). That circRNAs act as sponges for

miRNAs to influence the transcription of target genes is now widely

accepted (145,146).

Circ-ITCH has been reported to significantly affect

several biological characteristics of tumors by acting as a tumor

suppressor (147,148). Knockdown of circ-ITCH expression

in human cervical cancer (CC) tissues and cell lines attenuated the

inhibitory effects of circ-ITCH on the malignancy of CC cells

(149). The presence of a

circ-ITCH/miR-93-5p/FOXK2 axis was further explored in that study;

miR-93-5p has been shown to function as a tumor promoter in several

types of cancer (150–152) and it is significantly upregulated

in CC tissues and cell lines (153). The researchers confirmed that

circ-ITCH could directly bind to miR-93-5p using bioinformatics

tools and this was confirmed using a luciferase reporter assay.

FOXK2 expression was significantly downregulated in CC tissues. The

study also confirmed that FOXK2 was a target of miR-93-5p using

TargetScan and this was verified using a luciferase reporter assay.

miR-93-5p mimics significantly inhibit FOXK2 expression in HeLa

cells and FOXK2 knockdown significantly reduced FOXK2 expression in

HeLa cells transfected with a miR-93-5p inhibitor (153). In summary, circ-ITCH achieves its

tumor-suppressive activity by sponging miR-93-5p to regulate FOXK2

expression and its role as a tumor suppressor in several types of

cancer is well established and reviewed elsewhere (154).

Another example of a circRNA acting as a sponge can

be found in clear cell kidney cells (ccRCC). The novel circRNA

UBAP2 acts as a miRNA sponge to regulate miR-148a-3p, which itself

affects FOXK2 mRNA and protein levels and influences ccRCC cell

proliferation, migration and invasion (155). In addition, a study on pulmonary

fibrosis showed that circHIPK3 enhances FOXK2 expression by

sponging miR-30A-3p, thereby promoting fibroblast activation

proliferation and glycolysis (156).

lncRNAs are transcripts that do not encode proteins

and are often >200 nucleotides (157,158). lncRNAs are presently hypothesized

to serve vital roles in several cellular processes, including cell

cycle regulation (159),

differentiation (160–162), metabolism (163) and various diseases (164,165). One study has shown that certain

lncRNAs are involved in cancer progression through the adsorption

of miRNAs via sponging (166).

lncRNAs can also regulate FOXK2 expression. Emerging evidence

suggests that lncRNA tumor protein 53 target gene 1

(TP53TG1), enriched in CC, sponges the FOXK2-targeting

miR-33a-5p and thus increases FOXK2 expression. This increase in

FOXK2 expression promotes related protein activity, activates the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and increases tumor biological

activity (167). It has been

reported that TP53TG1 functions as an oncogene in several

types of cancer (168,169) and miR-33A-5P can function as a

tumor suppressor gene in several other types of cancer (170–172). Similarly, lncRNA small nucleolar

RNA host gene 7 (SNHG7) also functions as an oncogene to

promote HCC tumor growth in vivo via a miR-122-5p/FOXK2

axis. In addition, lncRNA SNHG7 abrogated the negative regulation

on FOXK2 through the sponging of miR-122-5p and promoted the

occurrence and development of liver cancer (173). The mechanism of FOXK2 as a

repressor and activator of gene transcription remains to be further

studied.

A number of molecules have been shown to interact

with FOXK2, which interacts with other transcription factors and

active proteins as a key to carrying out its regulatory functions.

Protein kinases are one of the most common partners that interact

with FOXK2. Their interactions are involved in a variety of

cellular functions, including metabolism (84,88),

autophagy (1), cell cycle

regulation (26), cell

proliferation and survival (174)

and changes in subcellular localization (2). FOXK2 binds to oncoproteins; Qian

et al (175) reported that

the sex-determining region Y box 9 (SOX9) oncoprotein directly

binds to the FOXK2 promoter, significantly upregulating its mRNA

expression levels. FOXK2 also interacts with activating and

inhibiting proteins. For example, FOXK2 efficiently recruits

activating protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factors to chromatin and

binds to them, contributing to AP-1-dependent gene expression

changes (176). In addition,

FOXK1 and FOXK2 can recruit the Sin3a HDAC complex to inhibit the

expression of essential autophagy genes (87). Notably, FOXK2 appears to recruit

Sin3a HDAC complex and BAP1 impartially. The mechanism of this

differential recruitment is unclear and further studies are

necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the

differing epigenetic modification preferences of local chromatin.

FOXK2 functions well with proteins exhibiting similar functions.

For example, methyl-CpG binding domain proteins (MBD6) and FOXK2

are prime candidates for MBD proteins and DNA methyl-dissociation

reading. However, MBD6 is recruited to laser-induced DNA damage

sites in a manner independent of its MBD domain and interacts with

PR-DUB (69,70,177,178).

An excellent example of FOX interfamily interactions

is the dynamic occupancy model of FOXK2 and FOXO3a for shared

binding modes. The two genes dynamically correlate and isolate

rather than directly competing to control their FOXO-dependent gene

expression functions (179).

One study demonstrated that FOXK1 and FOXK2 interact

with the c-terminal region of the adenovirus (HAdV) protein E1A,

inhibiting HAdV E1A-induced proliferation and transformation in

cells (180). DVL2, an adaptor

protein of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, serves an important role in the

development of colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CRC) by

linking the inflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway to the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (181). FOXK2 associates with DVL2 and

migrates to the nucleus to positively regulate the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (181). The PDZ

domain of DVL2 and a four-amino acid motif named IVLT are necessary

when binding to the FHA domain on FOXK2 and its adjacent region

(residue ~129-171) (32).

Scaffold proteins are high-order complexes that bind

at least two protein partners together, specifically recruiting

signaling proteins, within the delicate tissue framework to achieve

temporal and spatial control of specific pathways (182–185). For example, a breast cancer study

showed that FOXK2 interacts with BRCA1 as a scaffold protein for

BReast-CAncer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1)/BRCA1-associated RING

domain protein 1 (BARD1) and estrogen receptor α (ERα), resulting

in enhanced degradation of ERα and ultimately reduced

transcriptional activity (186).

Proteins typically do not function as single modules

in the biological processes of living cells. Instead, they function

with other proteins in dynamic networks, interacting with numerous

biologically active substances. For example, in a recent study of

tumor-derived morphological mutations, BAP1 was isolated from

wild-type ASXL1 mutants whose C-terminus was truncated and whose

regulation of target genes was lost through the ASXL1-BAP1-FOXK1/K2

axis (89). This example

demonstrates that numerous proteins can interact amongst themselves

in tandem within intricate complexes. Furthermore, their

interactions occasionally span multiple complexes, giving

fascinating and elaborate protein-protein relationships.

In conclusion, FOXK2 regulates target genes through

a combination of multiple transcription factors. FOXK2 and

chaperone proteins form various complexes and the specific

interactions between FOXK2 and each component of the complex lead

to the diversity of its regulatory functions. However, the

mechanisms by which FOXK2 interacts with other transcription

factors and active factors are not well understood. The current

studies neither reveal how FOXK2 selects for preferred interacting

partner nor address the biological significance or evolutionary

advantages of this selection.

In cancer, FOXK2 functions as a gatekeeper of DNA

repair and mutation prevention. Studies have shown that genes

mediating the DNA repair process are inextricably linked to

potential mutations in cancer (187–189). Furthermore, FOX proteins regulate

several aspects of cell biology by inducing the transcription of

target genes (190,191). The ability of FOXK2 to regulate

fundamental biological processes is evident in cell proliferation

(132,174), DNA repair (192), apoptosis (193) and regulation of cell metabolism

(84,88) (Fig.

5). Indeed, there is growing evidence that FOXK2 is closely

related to the development of tumors, but it may also serve

opposing roles based on the specific type of tumor. Several studies

have reported that FOXK2 expression is low in breast cancer

(186,194), NSCLC (132), glioma (195) and ccRCC (193). Its role as a tumor suppressor

gene is not evident. Conversely, the increase in FOXK2 expression

is closely related to the occurrence and development of tumors.

Other studies have found that FOXK2 expression is upregulated in

papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (196), anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC)

(197), CRC (198) and HCC tissues (131). These conflicting findings suggest

that tumor-specificity may determine the role of FOXK2 and dictate

its function as an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene in

tumorigenesis and progression. However, general rules cannot be

extrapolated from current data and these results are far from

helping the understanding of the general regulatory pattern of

FOXK2.

Enabling hallmarks are the precise molecular and

cellular mechanisms that allow for the evolution of

tumor-initiating cells to develop and acquire core signature

capabilities, typically during tumor development and malignant

progression. In addition, enabling hallmarks assist in the linkage

of cancer marker phenotypes to the TME and explains various aspects

relevant to cancer (9,10). These enabling features are present

across all stages of cancer progression.

Genomic instability in cancer cells has been

considered the primary hallmark, resulting in random mutations and

chromosomal rearrangement (9,10,199,200). It has been reported that a

patient with West syndrome, a severe intellectual disability and

malformation, was identified as partial tetrasomy 17q25.3 and the

breakpoint of chromosome 17q25.3 rearrangement was located in the

FOXK2 (3). Certain mutated

genotypes confer advantages in subclonal selection and growth in

the local tissue environment (201). A roster of alterations in

conditions of genomic instability have been suggested for DNA

damage prevention, DNA repair system activation, DNA repair

defects, centrosomes and telomerase (202).

Genomic stability is a prerequisite for high

fidelity DNA and thus DNA is subject to precise and complex control

mechanisms (9,10). Throughout the cell cycle of a

normal cell, the integrity of the genome is protected by

checkpoints (9,10). An abnormal number of chromosomes

during cancer development indicates the failure of one or more cell

cycle checkpoints (203). It is

well established that CHK2 functions as an effector kinase of the

ATM-CHk2-p53 pathway in DNA damage repair and its phosphorylation

activity is critical for the DNA double-stranded break (DSB)

response (204,205). A transcriptional control study of

autophagy showed that Ser61 within FOXK2 is phosphorylated by CHK2,

which inhibits apoptosis of cancer cells via DNA damage (1).

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is vital in ensuring

replication fidelity and maintaining genomic stability and is

critical in the prevention of mutations (206). MMR defects that lead to a high

mutational burden were exemplified in a study of breast cancer

(207). Researchers have modeled

the initiation of MMR (208).

FOXK2, as a novel G/T mismatch-specific binding protein, may sense

G/T mismatches and recruit BAP1 to trigger the DNA repair mechanism

(192,209). The phosphorylation of BAP1 and

its catalytic activity are necessary prerequisites for its repair

function (209). Mechanistically,

FOXK2 may act as a DNA-binding protein that binds to the distorted

conformation of DNA resulting from mismatches, facilitating the

recruitment of other repair proteins (210). In response to laser

micro-irradiation, MBD6 was recruited to laser-induced DNA damage

sites independently of PR-DUB. It was also found that FOXK2/PR-DUB

and MBD6 share a genome target gene subset (69). A study of yeast FOX proteins showed

that lexa-FHA fusion proteins bind to chromatin, induced by DSBs,

and subsequently recruit donors in an FHA-domain-dependent manner

(211). Importantly, the presence

or absence of the N-terminal coding region (139–459 bp) of the FHA

domain determines whether FOXK2 binds specifically to the G/T

mismatch. This specific binding either recruits DNA repair proteins

such as YB-1 to form complexes that initiate DNA mismatch repair,

or freezes transcription and replication of mismatched genes

leading to cell death (192).

Together, these findings suggest that FOXK2 serves an important

role in the regulatory mechanisms of DNA repair.

Loss of telomere protection can lead to a telomere

crisis, a widespread state of genomic instability that can amplify

or drive aging-related cancer development (212,213). Conversely, telomerase activation

provides an opportunity to eliminate the telomere crisis, leading

to the formation of cancer clones with genomic rearrangements

(212,213). Although the relationship between

FOXK2 and telomeres or telomerase has not been studied in-depth,

studies have implicated FOXK1 in cellular telomere fusion (33,214).

Epigenetic effects serve a significant role in

regulating the interactions between genomes and the environment and

this has attracted considerable research interest (215). These epigenetic effects may also

influence gene expression patterns and drive cancer development

(64,216,217). Non-mutational epigenetic

regulation of gene expression was initially interpreted, a decade

ago, as a powerful mechanism that mediates development and

differentiation (218,219). This concept has received

increased attention in recent years regarding its significance in

cancer biology (10,220,221). It has been shown that crucial

regulatory elements constitute a set of epigenetic regulations

(44). The emerging field of

epitranscriptomics, involving modifications of mRNAs and lncRNAs as

well as newly identified DNA cytosine modifications, is a key

mechanism of epigenetic regulation promoting cancer progression

(222). As described earlier,

epigenetic modification of FOXK2 mediates several chromatin events

critical in the multi-step process of cancer development. The

present review highlighted a possible link between environmental

exposure to cancer risk and epigenetic modifications of DNA. One

study focusing on differences in DNA methylation amongst ethnic

firefighters showed that FOXK2 hypomethylation partly explains the

differences in epigenetic susceptibility to cancer risk associated

with toxic exposure between ethnic groups (56). Chemical exposure, including but not

limited to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, may lead to

differential methylation of FOXK2 CpG sites across ethnic groups

(56). Other suitable examples are

the hypermethylation of leukocytes caused by smoking, which is

positively correlated with smoking level (60). Certain lifestyles, such as exercise

and bariatric surgery, reduce NNMT expression and lead to increased

levels of FOXK2 methylation (57).

However, the relationship between more environmental factors,

lifestyle and psychological stress and FOXK2 methylation has not

been well explored. In addition, few studies have been published on

the regulatory mechanism of FOXK2 methylation and its effect on

downstream target genes.

The link between chronic inflammation and the

development and progression of cancer has been long established

(223,224). Inflammatory mediators and cell

effectors promote tumor development by changing the local TME. The

altered microenvironment disrupts the immune response and

contributes to the proliferation and survival of malignant cells

(224). Inflammation in the TME

is mainly characterized by the accumulation of innate and adaptive

immune cells (223,225), both of which promote tumor

progression (226,227). However, the association of these

immune cells with FOXK2 has not been fully studied. Encouragingly,

a study of early immune networks suggested that FOXK2 is involved

in immune regulation in early life (the 1st, 2nd, 3rd trimester of

gestations, birth, newborn and infant periods) (228). Other studies have also shown that

FOXK2 affects the activation of T lymphocytes and serves a role in

the development of immune networks (229,230). NF-κB is a TF involved in the

inflammation and immune response cellular pathways (231) and it has been shown to be

involved in tumorigenesis (232,233). FOXK2 expression is positively

regulated by NF-κB. For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF)

promotes FOXK2 expression through the NF-κB pathway (198). Alterations in TME caused by

cellular inflammation can also induce DNA damage, which in turn

assists tumor cells to acquire a variety of biological abilities

(227,234,235). As previously described, FOXK2

functions as a G/T mismatch-specific binding protein that initiates

DNA damage repair or freezes transcription and replication of

mismatched genes. However, this function in cancer is still poorly

characterized. Together, these studies suggest that the immune

networks are closely related to FOXK2 and serves a crucial role in

oncogenesis. Studies have shown that the adaptive immune system can

promote tumor suppressor gene inactivation (224,236); however, whether FOXK2 is involved

in this regulation is unknown.

The relationship between the microbiome and human

cancer is complex and contested and the relationships are well

described elsewhere (237,238).

Recently, polymorphic variations in an organism's microbial

community have been suggested as constituting a uniquely

advantageous trait for acquiring signature abilities (10). This view is becoming increasingly

compelling. Since human HAdVs were first isolated from an adenoid

tissue nearly 70 years ago (239), the ability of specific categories

of viruses to induce tumor growth has been demonstrated in

different mammalian models (240,241). The possible role of HAdVs in

malignant diseases in humans has been continuously explored, but

their role in human cancer remains unclear (242). One study found that the binding

and interaction of the c-terminal region of the viral E1A protein

with FOXK2 is essential for suppressing HAdV-mediated tumor

formation in vivo and in vitro (180). Furthermore, HAdV E1A protein

interaction with FOXK1 and FOXK2 is dependent on the levels of

phosphorylated E1A.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is another interesting

virus in relation to FOXK2. The E6 protein of HPV 21/14 exerts its

antitumor effects by targeting FOXK1 and FOXK2 in tandem with a

conserved Thr-Ser motif (180).

In addition, the interaction of the E6 protein with FOXK1 and FOXK2

in epithelial cells may drive viral infection replication and

differentiation rather than transformation (180). However, the relationship between

FOXK2 and more viruses has not received sufficient attention.

The most fundamental characteristic of cancer cells

is their ability to maintain chronic proliferation. The degree of

proliferation is directly related to the development and

progression of cancer (9). During

development, growth factor signaling pathways induce proliferation,

migration, differentiation and death in select populations of cells

to ensure adherence to programmed organ sizes and functions. The

expression of cycle-related proteins and signaling pathways in

cancer cells is often altered, resulting in oncogenic activation of

growth factor signals or inhibition of cell death, leading to

pathological proliferation and tumor growth. These shared signaling

pathways primarily include hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1),

CDKs, NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R)

and estrogen receptor signaling (201).

Different studies have assessed the effects of

FOXK2 on the signaling pathways aforementioned. FOXK2 knockdown

induces non-neoplastic immortal cell death, proliferation and

survival as FOXK2 deletion leads to increased expression of p53

up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and NOXA (174).

The transcription factor HIF-1 structurally acts as

a heterodimer and regulates inducible genes that respond to changes

in oxygen levels (243,244). Nuclear localization of this

molecule in conditions of low oxygen concentrations induces

transcription of several genes responsible for tumor invasiveness

(245). The network crosstalk

between FOXK2 and HIF-1 is complex. FOXK2 interacts with ASXL1, a

vital component of PR-DUB, to regulate HIF-1α and STAT3 signaling

pathways (89).

PI3Ks are a family of lipid kinases initially

hypothesized to be involved in the transformational ability of

viral oncoproteins. Subsequent studies found that PI3Ks were

involved in regulating various cellular processes, including cell

proliferation and differentiation (131,250). The effects of FOXK2 and PI3Ks are

multi-dimensional. In certain clinical samples, such as patients

who only received surgery without preoperative chemotherapy or

radiotherapy, FOXK2 is negatively regulated by miR-1271-5p and

exerts carcinogenic activity by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway in HCC cells (131).

TP53TG1 promotes the occurrence and development of CC by regulating

miR-33A-5P targeting FOXK2 (167). FOXK2, as a downstream regulator

of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, promotes GC proliferation

and inhibits apoptosis (130).

CDKs are serine/threonine kinases that rely on a

cyclin regulatory subunit to initiate cell division and

transcription, particularly in cancer progression (251). FOX TFs, including FOXKs, control

cellular processes during physiological development and in the

development and progression of cancer (190,252,253). Furthermore, in prokaryotes and

metazoans, a fundamental process controlled by FOX TFs is cell

cycle progression (76,254–257). In addition to regulating the

transcription of target genes in the cell cycle, FOX TFs are

regulated by cyclically regulated kinases. There are extensive and

complex links between cell cycle-regulated kinases and the FOX

transcription factor family (257). Studies involving the regulatory

function of FKH2 (a homolog of human FOXKs) on the cell cycle

support the link between cycle-regulated kinase and the FOX protein

(76,77).

Furthermore, another study identified FOXK2 as a

target of the CDK-cyclin complex in human cells and found that

FOXK2 levels are cell cycle-dependent, reaching a maximum

concentration during the M-phase (26). This study also found that FOXK2

mRNA levels did not change significantly during the cell cycle,

suggesting that FOXK2 is regulated via PTMs. Notably, endogenous

FOXK2 stably translocates to the nucleus of most asynchronously

growing U2OS cells (26), while

the subcellular localization of other FOX TFs varies with the stage

of the cell cycle (257,258). FOXK2 relocalization away from the

DNA during mitosis (26) also

differs from the persistent association of FOXK1 with DNA (259). However, the significance of this

small change in nuclear localization has not been thoroughly

studied.

Cancer stem cells are the source of tumor cells,

granting them the ability to achieve a state of cell immortality.

Recent research has shown that FOXK2, a highly expressed stem

cell-specific TF in ovarian cancer, binds to an intron regulatory

element of the sensor ERN1. This binding triggers an unfolded

protein response that directly upregulates inositol-requiring

enzyme 1α (IRE1α, ERN1 gene) expression. In addition, it

results in the X-box-binding selective active splicing of protein 1

(XBP1) and activation of stemness-related pathways (264). However, there is still a lack of

broader studies on the effect of FOXK2 on cancer stem cell stemness

and little is known about the regulatory mechanism of FOXK2

upstream regulatory signals in the maintenance of stemness.

High-throughput sequencing has proved to be an

invaluable tool in cancer research. The ability to avoid

anti-growth signals and the loss of tumor suppressor factors leads

cancer cells to exhibit disorderly and uncontrolled growth, which

is widely accepted as a hallmark of cancer (9,265).

Several tumor suppressor genes function together to determine cell

fate (265). In addition to BAP1,

BRCA1 and DVL as aforementioned, the relationship between FOXKs and

other tumor-related factors is discussed in the present review.

Phosphatase and TENsin Homolog (PTEN) is a phosphatase that

dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-triphosphate (PIP3) to PIP2

(266–268). PTEN is a well-known tumor

suppressor gene involved in several types of cancer, negatively

regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (266). However, loss-of-function

mutations of PTEN are often found in tumors (269). Through ChIP and dual luciferin

reporter assays, FOXK1 was shown to directly bind to the miR-32

promoter. It was also shown to positively regulate the expression

of miR-32 and transmembrane protein 245 gene (TMEM245). In CRC,

FOXK1 was shown to inhibit the expression of PTEN through

transcriptional regulation of TMEM245/miR-32, thereby enhancing the

proliferation, migration and invasion of CRC cells and reducing the

apoptosis of CRC cells (270).

Another study further demonstrated the existence of a core promoter

region in the −320 to −1 bp range of the 5′ flanks of the

TMEM245/miR-32 gene and inhibitory regulatory elements in the-606

to −320 bp range (271).

FOXK2 also interacts with other tumor suppressor

proteins. For example, after S-phase DNA damage, FOXK1-53BP1

interaction is dependent on ATM/CHK2, which reduces the correlation

between 53BP1 and its downstream factors RIF1 and PTIP (214). In addition, FOXK2 interacts with

the transcriptional co-suppressor complex NCoR/SMRT Sin3a NuRD and

REST/CoREST to exert its anti-tumor role. As a result, FOXK2

inhibits genes such as HIF-1β and EZH2 and modulates several

signaling pathways, including the hypoxia response (194).

Maintenance of the balance of pro-apoptotic and

anti-apoptotic proteins is crucial in determining cell apoptosis

development. The struggle between apoptosis and anti-apoptosis is

present in all stages of cancer, from precancerous lesions to tumor

formation. The deregulation of apoptosis is associated with the

development and progression of cancer through unmoderated cell

proliferation and cancer resistance to drug therapy (272). Therefore, the ability to evade

apoptosis is considered a defining cancer hallmark (9). Among the several anti-apoptotic

pathways, the overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins is the

primary strategy cancer cells use to avoid apoptosis (201). The role of the Bcl-2 family

members in apoptosis is well established. The Bcl-2 homologous (BH)

domain is the structural basis for interaction among its members

and drives pro-apoptotic or anti-apoptotic functions (273,274).

One study found that knockdown of FOXK2 led to

reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis in mouse NIH3T3

fibroblasts and mouse breast cancer NMuMG cells (174). After FOXK2 gene KO, expression of

the pro-apoptotic proteins PUMA and NOXA was significantly

upregulated (174) and PUMA and

NOXA are members of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family (275). A positive association between

FOXK2 and increased phospho-AKT levels has been shown (131). Additional studies have

demonstrated that AKT is phosphorylated by PDK1 on one or two

specific sites, which is necessary for its full catalytic activity.

Activated AKT inactivates the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins

such as Bcl-2 and FOXO TFs, positively affecting cell survival

(276,277). Although there is evidence

suggesting that FOXK2 exerts an anti-apoptotic role, research on

the effects of FOXK2 on cell proliferation and survival is limited.

Thus, further studies are required to understand the function and

mechanism underlying the anti-apoptotic effects of FOXK2 are

required.

Angiogenesis, defined as the growth of new

capillaries from existing blood vessels, involves endothelial cell

migration, invasion and duct formation. Angiogenesis is essential

for dividing cells and this is especially true for tumor cells, as

the new vessels provide oxygen and nutrients to maintain cell

division (278,279). The activation of angiogenesis can

result from the imbalance between pro-angiogenic and

anti-angiogenic molecules (280,281). Of all the angiogenic factors, the

most influential are VEGF, EGF and platelet-derived growth factor

(PDGF) (282). VEGFA exerts an

angiogenic effect by binding to VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 and its

co-receptors neuropilin-1 and neuropil-2 (NRP-1 and NRP-2)

(283,284). In addition, VEGFA regulates

endothelial cell survival and enhances the mobilization of bone

marrow-derived endothelial precursor cells (285,286). VEGFA/VEGFR-2 signaling is widely

considered the most important angiogenic mechanism.

It has previously been reported that VEGFA

expression is increased in ATC following apatinib treatment

(287). Furthermore, the ChIP

dual-luciferase reporter system and functional assays confirm that

FOXK2 promotes ATC angiogenesis by inducing VEGFA transcription

(197). When VEGFR-2 is blocked,

VEGFA then binds to VEGFR-1, promoting angiogenesis by activating

ERK, PI3K/AKT and P38/MAPK signaling in human umbilical vein

endothelial cells, which compensates for VEGFR2 blockage (197,288). Notably, VEGFA binding to VEGFR-1

can promote FOXK2-mediated VEGFA transcription and angiogenesis

through a positive feedback loop (197).

In a diabetes mellitus mouse model and in human

ECs, miR-140-3p transcription inhibits FOXK2 signaling, promoting

key angiogenic steps, including EC proliferation, cell migration

and endovascular formation (135). Conversely, FOXK1 inhibits

angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFA transcription (289). However, the controversial works

aforementioned also leave a number of unanswered questions. The key

to solve these problems is to further study the regulatory

mechanism of FOXK2 and angiogenesis related metabolic

remodeling.

Tumor cells are especially adept at adapting to the

environment and extracting energy. Their ability to increase

glucose uptake and lactic acid production (the Warburg effect) is

an excellent example of the evolution of substrate metabolic fate

(290). This well-evolved

flexibility is necessary to ensure enhanced biomass synthesis while

maintaining redox equilibrium and cellular homeostasis (291,292). These properties reflect a balance

between the availability of growth-signaling chemical nutrients,

the subsequent adaptive metabolic remodeling and the everyday needs

of the cell (293).

A study showed that FOXK1 and FOXK2, experimentally

associated with nutritional stress, may function as regulators to

induce aerobic glycolysis reprogramming (88). Mechanistically, FOXK1 and FOXK2

induce aerobic glycolysis by upregulating hexokinase 2 (HK2),

phosphofructokinase, pyruvate kinase (PK) and lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH). These enzymes are associated with glucose metabolism and

regulate the flow of glycolysis (88,294). Further studies have shown that an

increase in pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinases 1 and 4 activity

prevents the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA in the

mitochondria and pyruvate is instead reduced to lactic acid

(88,290,294).

Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) is an

α-inhibitory protein. TXNIP modulates glucose homeostasis through

strong negative regulation of glucose uptake and aerobic glycolysis

(295,296). FOXK1/FOXK2 can directly bind to

the TXNIP promoter to exert an influence on aerobic glycolysis

(89). It is also found that

structurally and functionally deficient PR-DUB complexes, including

the absence of FOXK1/FOXK2, significantly reduce TXNIP protein

levels, resulting in increased glucose uptake and increased

intracellular lactic acid and ATP levels (89).

The FOXK transcription factor regulates glucose

consumption by altering its own subcellular localization and

affecting HIF-1α gene expression through a process regulated by

mTOR (2,87). PDH can be hyper-phosphorylated by

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs), which are upregulated by

HIF-1α, resulting in its inactivation. This inactivation inhibits

the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and increases lactic acid

production (290). Additionally,

HIF1α regulates several major glycolytic proteins, including the

glycolytic enzymes HK2, phosphoglycerate kinase 1, LDHA and PKM2

(297,298).

The present review examined the most influential

roles of FOXK2 in cancer development. It highlighted the complexity

of the function of FOXK2 and gave an outlook on what has to be

investigated in future work. In addition, it described the current

understanding of FOXK2 and its global capabilities, providing

context for explaining how FOXK2 functions in cancer, both

individually and as a part of numerous complex systems. The

extensive expression of FOXK2 and inherent structural

characteristics distinguish it from ~1,600 other human TFs

(304).

FOXK2 functions in several different contexts by

cooperating with other active molecules. The suggestion that TFs

work together to achieve their function is widely accepted

(305,306). The properties of FOXK2 and other

members of the FOX family determine its precise function in

biology. For example, there are also binding differences between

FOXK2 and other members of the FOX family among functionally

specific target genes partly influenced by the flanking region

(179,307). Theoretical and practical

observations show that synergistic binding and co-regulation are

the primary synergistic modes of TFs, which help bioactive

molecules bind to DNA, influencing chromatin accessibility and

downstream gene transcription (308). However, specific modes of action

of FOXK2 expression in different time and space under physiological

and pathological conditions have not been clearly demonstrated and

general principles cannot be inferred from the current study.

FOXK2 mediates several functionally significant

chromatin events. This suggests that DNA-mediated cooperative

binding is crucial for the function of TFs (309). TFs that can bind to target sites

on nucleosome DNA are known as pioneer factors (310,311). These pioneer TFs are responsible

for opening chromatin or changing the conformation of the

nucleosome by initiating nucleosome displacement (312–314). The above are necessary

prerequisites for recruiting other bioactive substances and other

TFs (315). These pioneer TFs

control cell fate by locally opening chromatin to initiate

transcription (316,317). Its stability is partly influenced

by steric hindrance (318) and

nucleosome affinity for active chromatin remodeling (319). Members of the FOX family have

been shown to function as pioneer factors as they can bind to

nucleosome DNA and open chromatin, thereby exposing DNA binding

modes allowing it to bind to other TFs and subsequently regulate

gene expression (320,321). Based on this evidence and the

regulation of chromatin events by FOXK2 described above, FOXK2 may

be considered a pioneer factor. Unraveling local chromatin regions

without the help of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factors

(322,323) is a valuable characteristic for

consideration of FOXK2 as a pioneer candidate.

Protein-protein interactions are regulatory

mechanisms for TFs that are well understood. Studies using

single-molecule imaging confirm that when multiple TFs bind with

DNA at consistently spaced intervals with a consistent orientation,

the binding sites are occupied for longer periods of time,

conferring additional stability (324,325). FOXK2 has been shown to form

complexes with several proteins to perform different functions.

According to its nature, eukaryotic gene expression regulation can

be divided into instantaneous (reversible) (326,327) and development (irreversible)

regulation (328,329). Instantaneous regulation

determines the fate of metabolic substrates and hormonal

fluctuations in enzyme activity. It also dictates the substrate or

hormonal concentrations at different stages of the cell cycle.

Development regulation influences overall eukaryotic cell

differentiation, growth and development processes. The present

review provides an overview of the contribution of FOXK2 to

transient and developmental regulation and highlights the role of

epigenetic modifications in controlling chromatin accessibility and

protein interactions.

The present review also discussed the multifaceted

role of FOXK2 in cancer. FOXK2 is involved in the pathogenesis of

numerous types of cancer. Whether FOXK2 functions as an oncoprotein

or tumor suppressor appears to be closely related to its partners

and its spatio-temporal properties and is thus tumor-specific. A

human cancer genome survey elucidated several salient features of

oncogenes involving the types of sequence alterations identified,

oncogenic mutations in cancer classes and protein domains encoded

by cancer genes (330). Indeed,

proteins encoded by cancer genes typically regulate cell

proliferation, differentiation and death. A functional review of

FOXK2 also supports the hypothesis of FOXK2 as an oncogene.

However, the genes that have been reported with precise causal

associations with tumorigenesis have been identified and initially

reported based on sufficient genetic evidence. Mutated genes that

provide cancer cells a growth advantage are highly suitable

candidates for oncogenes. Genes with translocations or copy number

alterations supported by convincing genetic data are another group

of candidates. Genes whose expression levels are altered only in

cancer cells are not suitable oncogene candidates, lacking any

mutations in DNA that cannot be conclusively linked to

tumorigenesis. However, FOXK2 mutations have not been reported

previously to the best of the authors' knowledge. Based on the

evidence, the biological regulatory functions of FOXK2, such as the

regulation of glucose metabolism and autophagy, may be used as

hijacking tools by tumor cells to enable unlimited proliferation

and survival of tumor cells. Of course, these assumptions are

contested and unproven. In the absence of more extensive research,

one should be cautious about making conclusive claims. However,

what is certain is that FOXK2 is vital in the development and

progression of cancer. In the foreseeable future, in-depth studies

targeting the regulatory features of FOXK2 may reveal its role in

tumorigenesis.

Although a similar review was published in 2019

regarding FOXK2 and its roles in cancer (4), the present review has updated the

recent findings about FOXK2 by a number publications since then.

First, it detailed the nomenclature and structural differences of

the three isoforms of FOXK2 and suggested that alternative splicing

of FOXK2 may be related to the role of kinase cascade signaling.

Second, for the regulatory mechanism of FOXK2, it considered both

its roles as a regulator and being regulated, with systematically

and clearly description in terms of gene level, post-translational

modification and protein interaction. Third, it summarized the

roles of FOXK2 as pioneer factor, G/T mismatch DNA-binding protein,

virus-binding protein, scaffold protein and transfer vector and

proposed that FOXK2 can be a candidate as a pioneer factor. Fourth,

it used the widely accepted concept of cancer hallmarks to describe

the broad role of FOXK2 in tumorigenesis in detail. Fifth, it took

a cautious attitude toward the definition of FOXK2 as an oncogene

or a tumor suppressor. FOXK2 may act as a hijacked molecular to

achieve its spatiotemporal and tumor-specific functions. Finally,

it objectively noted the shortcomings of current studies and the

directions for future research on FOXK2 in the hope that the

present review will provide useful information for researchers

working in this field.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Shandong Provincial

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. ZR2020KC016 and

ZR2020QH096); and the Weifang Science and Technology Bureau (grant

no. 2020YQFK013).

Not applicable.

ZhaoW and XL developed the idea, and wrote and

revised the manuscript. ZhanW and ZH supervised the study and

contributed to critical reading and revising of the manuscript. All

the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Chen Y, Wu J, Liang G, Geng G, Zhao F, Yin

P, Nowsheen S, Wu C, Li Y, Li L, et al: CHK2-FOXK axis promotes

transcriptional control of autophagy programs. Sci Adv.

6:eaax58192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He L, Gomes AP, Wang X, Yoon SO, Lee G,

Nagiec MJ, Cho S, Chavez A, Islam T, Yu Y, et al: mTORC1 promotes

metabolic reprogramming by the suppression of GSK3-dependent Foxk1

phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 70:949–960.e4. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hackmann K, Stadler A, Schallner J, Franke

K, Gerlach EM, Schrock E, Rump A, Fauth C, Tinschert S and Oexle K:

Severe intellectual disability, west syndrome, Dandy-Walker

malformation, and syndactyly in a patient with partial tetrasomy

17q25.3. Am J Med Genet A. 161A:3144–3149. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nestal de Moraes G, Carneiro LD, Maia RC,

Lam EW and Sharrocks AD: FOXK2 transcription factor and its

emerging roles in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 11:3932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gitter A, Siegfried Z, Klutstein M, Fornes

O, Oliva B, Simon I and Bar-Joseph Z: Backup in gene regulatory

networks explains differences between binding and knockout results.

Mol Syst Biol. 5:2762009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dai Z, Dai X, Xiang Q and Feng J:

Robustness of transcriptional regulatory program influences gene

expression variability. BMC Genomics. 10:5732009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu WS and Lai FJ: Functional redundancy of

transcription factors explains why most binding targets of a

transcription factor are not affected when the transcription factor

is knocked out. BMC Syst Biol. 9 (Suppl 6):S22015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: The hallmarks

of cancer. Cell. 100:57–70. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kaestner KH, Knochel W and Martinez DE:

Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription

factors. Genes Dev. 14:142–146. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lam EW, Brosens JJ, Gomes AR and Koo CY:

Forkhead box proteins: Tuning forks for transcriptional harmony.

Nat Rev Cancer. 13:482–495. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu Y, Ao X, Ding W, Ponnusamy M, Wu W,

Hao X, Yu W, Wang Y, Li P and Wang J: Critical role of FOXO3a in

carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer. 17:1042018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nakagawa S, Gisselbrecht SS, Rogers JM,

Hartl DL and Bulyk ML: DNA-binding specificity changes in the

evolution of forkhead transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 110:12349–12354. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li C, Lai CF, Sigman DS and Gaynor RB:

Cloning of a cellular factor, interleukin binding factor, that

binds to NFAT-like motifs in the human immunodeficiency virus long

terminal repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 88:7739–7743. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang JT and Lee V: Identification and

characterization of a novel human FOXK1 gene in silico. Int

J Oncol. 25:751–757. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mahajan A, Yuan C, Lee H, Chen ES, Wu PY

and Tsai MD: Structure and function of the

phosphothreonine-specific FHA domain. Sci Signal. 1:re122008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Durocher D and Jackson SP: The FHA domain.

FEBS Lett. 513:58–66. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Reinhardt HC and Yaffe MB:

Phospho-Ser/Thr-binding domains: Navigating the cell cycle and DNA

damage response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:563–580. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kalnina Z, Zayakin P, Silina K and Linē A:

Alterations of pre-mRNA splicing in cancer. Genes Chromosomes

Cancer. 42:342–357. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Roy M, Xu Q and Lee C: Evidence that

public database records for many cancer-associated genes reflect a

splice form found in tumors and lack normal splice forms. Nucleic

Acids Res. 33:5026–5033. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M,

Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D and Harper SJ: VEGF165b,

an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor,

is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res.

62:4123–4131. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hu Y, Fang C and Xu Y: The effect of

isoforms of the cell polarity protein, human ASIP, on the cell

cycle and Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis in human hepatoma cells. Cell

Mol Life Sci. 62:1974–1983. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang L, Duke L, Zhang PS, Arlinghaus RB,

Symmans WF, Sahin A, Mendez R and Dai JL: Alternative splicing

disrupts a nuclear localization signal in spleen tyrosine kinase

that is required for invasion suppression in breast cancer. Cancer

Res. 63:4724–4730. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Nirula A, Moore DJ and Gaynor RB:

Constitutive binding of the transcription factor interleukin-2

(IL-2) enhancer binding factor to the IL-2 promoter. J Biol Chem.

272:7736–7745. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Marais A, Ji Z, Child ES, Krause E, Mann

DJ and Sharrocks AD: Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the

forkhead transcription factor FOXK2 by CDK·cyclin complexes. J Biol

Chem. 285:35728–35739. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ and

Blencowe BJ: Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in

the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet.

40:1413–1415. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li C, Lusis AJ, Sparkes R, Nirula A and

Gaynor R: Characterization and chromosomal mapping of the gene

encoding the cellular DNA binding protein ILF. Genomics.

13:665–671. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I,

Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP and Burge CB: Alternative

isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature.

456:470–476. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Merkin J, Russell C, Chen P and Burge CB:

Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in mammalian

tissues. Science. 338:1593–1599. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Climente-González H, Porta-Pardo E, Godzik

A and Eyras E: The functional impact of alternative splicing in

cancer. Cell Rep. 20:2215–2226. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang W, Li X, Lee M, Jun S, Aziz KE, Feng

L, Tran MK, Li N, McCrea PD, Park JI and Chen J: FOXKs promote

Wnt/β-catenin signaling by translocating DVL into the nucleus. Dev

Cell. 32:707–718. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu Y, Ding W, Ge H, Ponnusamy M, Wang Q,

Hao X, Wu W, Zhang Y, Yu W, Ao X and Wang J: FOXK transcription

factors: Regulation and critical role in cancer. Cancer Lett.

458:1–12. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Giardina B, Messana I, Scatena R and

Castagnola M: The multiple functions of hemoglobin. Crit Rev

Biochem Mol Biol. 30:165–196. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Arbez N, Ratovitski T, Roby E, Chighladze

E, Stewart JC, Ren M, Wang X, Lavery DJ and Ross CA:

Post-translational modifications clustering within proteolytic