Introduction

The AT-rich interacting domain-containing protein 1A

(ARID1A) is a crucial subunit of the switch/sucrose non-fermentable

(SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex (1). It contains an AT-rich interaction

domain (ARID) responsible for binding to DNA (2) and features multiple LXXLL motifs in

the C-terminal region, known to facilitate interactions with

nuclear hormone receptors (3).

ARID1A helps direct SWI/SNF complexes to specific chromatin targets

by interacting with other transcriptional regulatory factors and

enhancing the affinity for binding to these sites, thereby altering

chromatin accessibility for several nuclear factors (4). ARID1A serves essential roles in

chromatin remodeling, chromosome organization, transcriptional and

epigenetic regulation (5,6).

ARID1A is a tumor suppressor gene that has been

reported to undergo mutations in several types of cancer (7–9). These

mutations in ARID1A include missense or truncating mutations, as

well as in-frame insertions or deletions (indels), which contribute

to the loss of protein function (8,9).

Previous studies have demonstrated the participation of ARID1A in

several biological processes involved in carcinogenesis and tumor

progression, such as cell cycle control, modulation of the immune

response and regulation of several signaling pathways (10,11).

ARID1A mutations are found in 3.6–66.7% of

colorectal cancer (CRC) cases, and they are thought to be caused by

mismatch defects (1,12). Previous studies have reported the

prognostic and tumor suppressive roles of ARID1A in CRC.

Immunohistochemical analyses have revealed a relatively high

incidence of ARID1A protein loss (25.8%) in primary CRC tumors.

Loss of ARID1A protein expression is associated with

clinicopathological characteristics, including advanced

tumor-node-metastasis stage, distant metastasis, poor pathological

differentiation and worse overall survival in patients with CRC

(13,14). Additionally, ARID1A expression is

associated with immune cell infiltration and immunotherapeutic

response in patients with CRC (15). ARID1A knockdown enhances the

proliferation, migration, invasion and chemoresistance of CRC cells

(16,17). Furthermore, ARID1A has been reported

to promote the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process by

regulating the expression of vimentin and E-cadherin (18,19).

However, the precise molecular mechanisms through which ARID1A

regulates CRC carcinogenesis and progression are not yet fully

understood.

Proteomics is a powerful tool that enables the

comprehensive analysis of global protein changes in biological

samples. It has been widely used in cancer research to unravel the

molecular mechanisms of diseases and facilitate the discovery of

biomarkers and therapeutic targets (20,21).

In the present study, a comparative proteomic analysis of

ARID1A-overexpressing colon cancer cells and empty vector control

cells was performed. Subsequently, bioinformatics analysis was

performed to gain novel insights into the molecular mechanisms

through which ARID1A is involved in CRC carcinogenesis and

progression. Moreover, the potential role of ARID1A in the

regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway was assessed using western

blotting.

Materials and methods

Establishment of ARID1A-overexpressing

SW48 cells

The pLenti-puro (cat. no. 39481; Addgene, Inc.) and

pLenti-puro-ARID1A (cat. no. 39478; Addgene, Inc.) were donated by

Professor Ie-Ming Shih from John Hopkins University (22). The plasmid vectors were cloned into

One Shot™ Stbl3™ Chemically Competent E.coli (cat. no. C737303;

Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and extracted using

the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen GmbH). Vector sizes were

confirmed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized using

RedSafe™ (Intron Biotechnology, Inc.). SW48 and 293T cells were

purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Both cells

were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and

penicillin/streptomycin (100 mg/ml; Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified

chamber. Using a second-generation lentivirus system, 293T cell

transfection was performed using Lipofectamine® 3000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 16 h at 37°C. For

each transfection, 1.5 µg of either the pLenti-puro-ARID1A or

pLenti-puro plasmid, 1 µg of packaging plasmid (psPAX2; cat. no.

12260; Addgene, Inc.), and 1 µg of envelope plasmid (pCMV–VSV-G;

cat. no. 8454; Addgene, Inc.) (23)

were used. The viral supernatants were harvested 48 h

post-transfection, centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min, and filtered

through 0.45-µm pore size membrane filters. Lentivirus at a

multiplicity of infection value of 5 was used to transduce SW48

cells with an 8-mg/ml polybrene reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA). After 24 h of transduction, the medium was replaced with a

selection medium (culture medium supplemented with puromycin at a

final concentration of 500 ng/ml; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) to establish stable ARID1A-overexpressing cells.

The stable cells were maintained in the selection medium (500 ng/ml

puromycin).

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Abcam) and

protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein from each

sample (20 µg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto

a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated with 5%

skimmed milk in PBS at 25°C for 1 h. Subsequently, it was incubated

with rabbit polyclonal anti-ARID1A (1:1,000; cat. no. HPA005456;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), rabbit monoclonal anti-c-Myc (1:1,000;

cat. no. 5605; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal

anti-T cell factor (TCF)1/7 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2203; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-cyclin D1 (1:1,000; cat.

no. 2978; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit polyclonal

anti-zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3; 1:1,000; cat. no. DF14289;

Affinity Biosciences), or mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (1:5,000;

cat. no. ab8245; Abcam) antibodies at 4°C overnight. Following

three washes with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), the

membrane was further incubated with corresponding horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000; cat. no.

65-6120; dilution, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or

anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. ab205719; Abcam) antibodies at

25°C for 1 h. Following three additional washes with PBS-T,

immunoreactive bands were visualized using Clarity™ Western ECL

Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and imaged using the

ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

intensity of immunoreactive bands was assessed using Image Lab

software (version 5.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). GAPDH was used

as a loading control. The band intensity of the target protein was

normalized to the corresponding loading control, and the relative

value was subjected to statistical analysis.

Sample preparation for shotgun

proteomics

The cells were placed in a 6-well plate at a density

of 200,000 cells per well and cultured in a complete growth medium

(DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.5 µg/ml puromycin) for 48 h

at 37°C. Following two washes with PBS, the cells were lysed with

0.5% SDS for effective extraction of both membrane-bound and

cytoplasmic proteins. Subsequent precipitation with acetone was

performed to remove contaminants and concentrate the proteins. The

lysate was mixed with 2 volumes of cold acetone (−20°C) and left to

incubate at −20°C for 12 h. Centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min

at 4°C was used to collect protein precipitates. The resulting

pellets were air-dried and stored at −20°C until they were used for

subsequent proteomic analysis. The protein concentration was

determined using the Lowry assay with BSA as a standard protein

(24). Protein samples (5 µg) were

subjected to in-solution digestion. The samples were dissolved in

10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, disulfide bonds were reduced using 5 mM

dithiothreitol in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 60°C for 1 h, and

sulfhydryl groups were alkylated using 15 mM iodoacetamide in 10 mM

ammonium bicarbonate at room temperature for 45 min in the dark.

Sequencing grade porcine trypsin (at a 1:20 ratio) was used to

digest the protein sample for 16 h at 37°C. The resulting tryptic

peptides were dried using a speed vacuum concentrator and

reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for nano-liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

LC/MS-MS

The LC/MS-MS method was selected to achieve high

sensitivity and resolution for peptide separation and

identification. Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis was

chosen due to its ability to provide a comprehensive and

reproducible analysis of protein expression levels in complex

biological samples without the need for expensive labeling reagents

and intricate sample preparation (25,26).

The tryptic peptide samples were prepared for injection into the

UltiMate™ 3000 Nano/Capillary LC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) coupled to a ZenoTOF 7600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX). Briefly,

1 µl peptide digests underwent enrichment on a µ-Precolumn (300 µm

i.d. × 5 mm) containing Acclaim™ PepMap™ 100 C18 HPLC column (5 µm;

100 A; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, separation

occurred on a 75 µm I.D. × 15 cm Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column (2

µm, 100Å; nanoViper; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The C18

column was maintained in a thermostatted column oven set to 60°C.

Solvents A and B containing 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1%

formic acid in 80% acetonitrile, respectively, were supplied to the

analytical column. A gradient of 5–55% solvent B was used to elute

the peptides at a constant flow rate of 0.30 µl/min over a period

of 30 min. The ZenoTOF 7600 system consistently used specific

source and gas settings throughout all acquisitions. These settings

included maintaining ion source gas 1 at 8 psi, curtain gas at 35

psi, CAD gas at 7 psi, a source temperature of 200°C, positive

polarity and a spray voltage set to 3,300 V. The top 50 precursor

ions with the highest abundance from the survey MS1 were chosen.

MS2 spectra were collected in the 100-1,800 m/z range with a 50

msec accumulation time, used the Zeno trap. LC-MS analysis of each

sample was performed in triplicate.

MS data analysis

Protein in individual samples was quantified using

MaxQuant 2.2.0.0 (27), using the

andromeda search engine to match MS/MS spectra with the UniProt

Homo sapiens database (https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000005640)

(27). Label-free quantitation was

performed using standard settings, including parameters such as

maximum of two miss cleavages, a mass tolerance of 0.6 daltons for

main search, trypsin as the digesting enzyme, carbamidomethylation

of cysteine as a fixed modification, and the oxidation of

methionine and acetylation of the protein N-terminus as variable

modifications. Protein identification required peptides with ≥7

amino acids and one unique peptide. Identified proteins with ≥2

peptides, including one unique peptide, were considered for further

data analysis. Protein false discovery rate was maintained at 1%,

determined using reversed search sequences. The maximal number of

modifications per peptide was set to 5. The Homo sapiens

proteome from UniProt served as the search FASTA file, whilst

potential contaminants listed in the contaminants.fasta file

provided by MaxQuant were automatically included to the search

space. The resulting MaxQuantProteinGroups.txt file was imported

into Perseus version 1.6.6.0 (28),

and contaminants unrelated to any UPS1 protein were eliminated from

the dataset. The three maximum intensities for each identified

protein were used for statistical comparisons using an unpaired

t-test with P<0.05 considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. The log2 ratios of the

ARID1A-overexpressing sample and the control sample were

calculated. Any intensity value of 0 was set to 0.001 to prevent

division by 0. Differentially altered proteins between the

ARID1A-overexpressing sample and the control sample were identified

using a threshold of P<0.05 and a log2 ratio of ≥ 2

or ≤-2.

Bioinformatics analysis

The Database for Annotation, Visualization and

Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp) online tool

(version v2023q4) (29,30) was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO)

and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analyses on differentially altered proteins. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant enrichment.

Bubble plot visualization of the enrichment results was performed

using the GraphBio online tool (http://www.graphbio1.com/en/) (31). Interaction network analysis of

altered proteins enriched in the Wnt signaling pathway was

performed using GeneMANIA version 3.6.0 (https://genemania.org/) (32) with parameters set as follows:

Organism ‘Homo sapiens (human)’ and network weighting

‘Biological process based’. Survival analysis and expression

correlation of ARID1A with ZNRF3 were analyzed using The Cancer

Genome Atlas-colon adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD) dataset (33) using the Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis 2 database (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) with default parameters

(34).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 8.0.1 (Dotmatics) was used

for statistical analysis. An unpaired t-test was used to compare

two datasets. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Establishment of ARID1A-overexpressing

SW48 cells

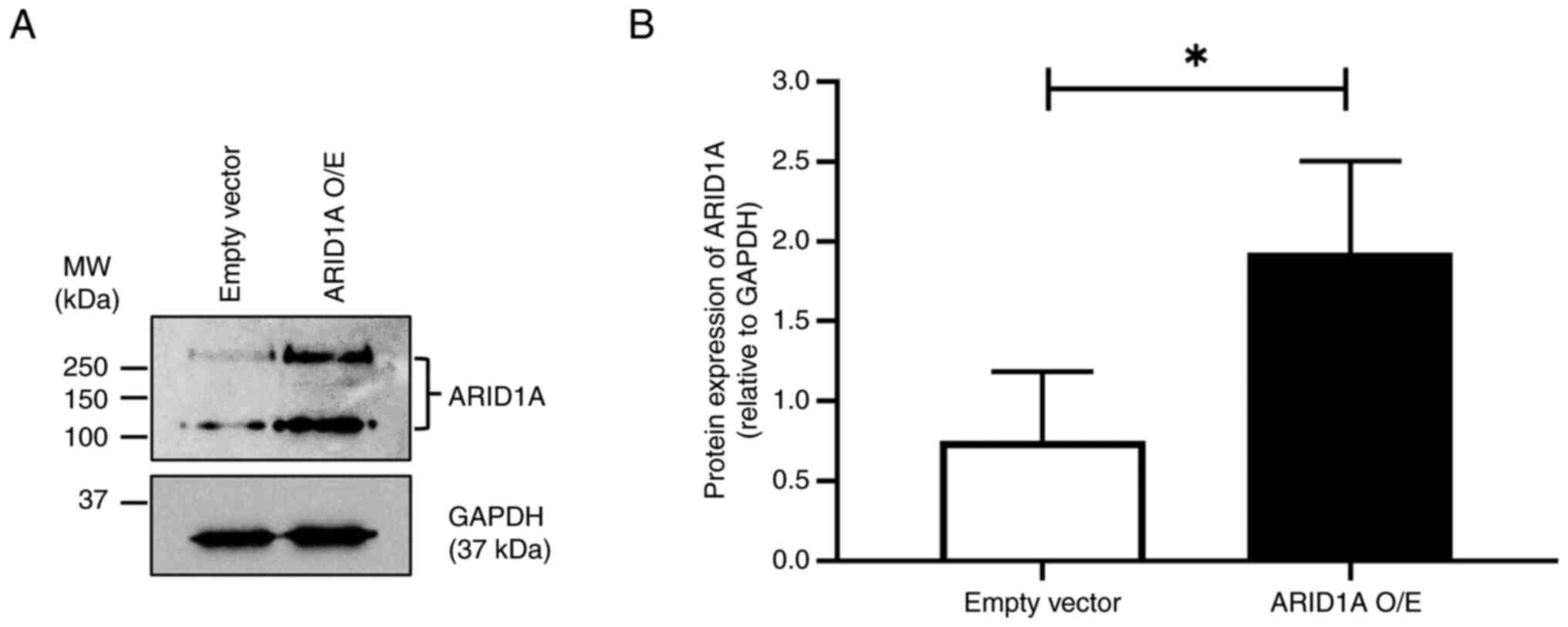

Following selection with puromycin, the level of

ARID1A protein in the empty vector control and

ARID1A-overexpressing cells was determined by western blotting. The

results demonstrated that the ARID1A protein level was

significantly higher in ARID1A-overexpressing cells compared with

the empty vector control, confirming the successful overexpression

of ARID1A in the cells (Fig.

1).

Proteomic analysis of altered proteins

in ARID1A- overexpressing cells

Proteomic analysis was performed to identify a set

of proteins differentially expressed following ARID1A

overexpression. Protein samples derived from ARID1A-overexpressing

and empty vector control cells were subjected to label-free

quantitative analysis by LC-MS/MS. The proteomic analysis

identified a total of 705 differentially altered proteins,

including 310 significantly increased proteins (P<0.05;

log2 ratio of ≥2) and 395 significantly decreased

proteins (P<0.05; log2 ratio of ≤-2) in the

ARID1A-overexpressing cells compared with the empty vector control

cells. Detailed information on differentially altered proteins is

presented in Table SI.

Functional enrichment analysis of

differentially altered proteins

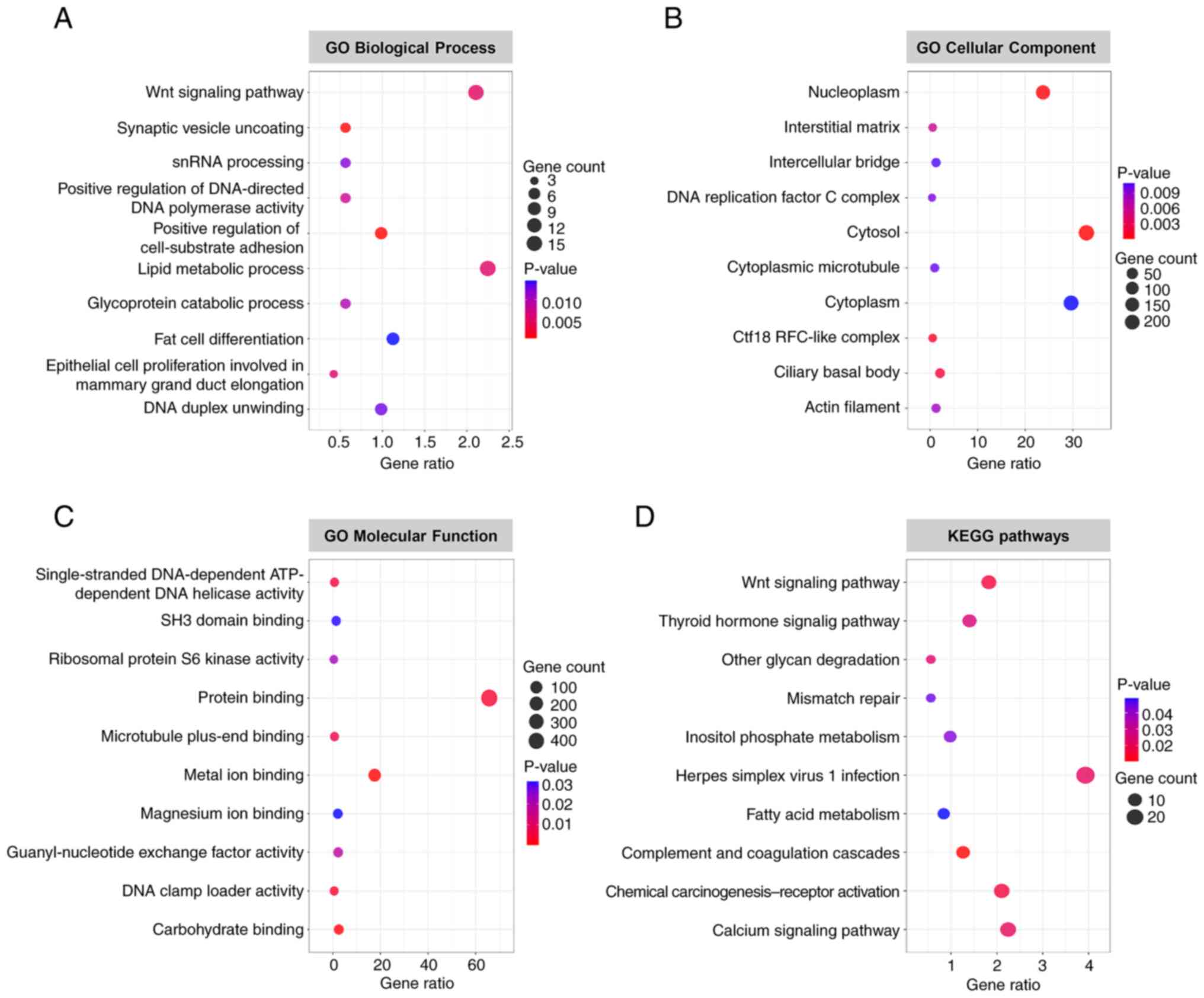

To assess the potential functions of ARID1A in colon

cancer cells, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were

performed on the differentially altered proteins. The results from

DAVID revealed that differentially altered proteins in

ARID1A-overexpressing cells were significantly enriched in several

biological processes, including the ‘Wnt signaling pathway’, ‘lipid

metabolic process’, and ‘fat cell differentiation’ (Fig. 2A). The majority of these altered

proteins were located in the ‘cytosol’, ‘cytoplasm’ and

‘nucleoplasm’ (Fig. 2B). This

analysis also identified several significantly enriched GO terms

for molecular function, such as ‘protein binding’, ‘metal ion

binding’ and ‘carbohydrate binding’ (Fig. 2C). KEGG pathway analysis indicated

that these altered proteins were enriched in several pathways,

including ‘herpes simplex virus 1 infection’, ‘calcium signaling

pathway’, ‘chemical carcinogenesis-receptor activation’ and ‘Wnt

signaling pathway’ (Fig. 2D).

Detailed information on significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG

pathways is summarized in Table

SII.

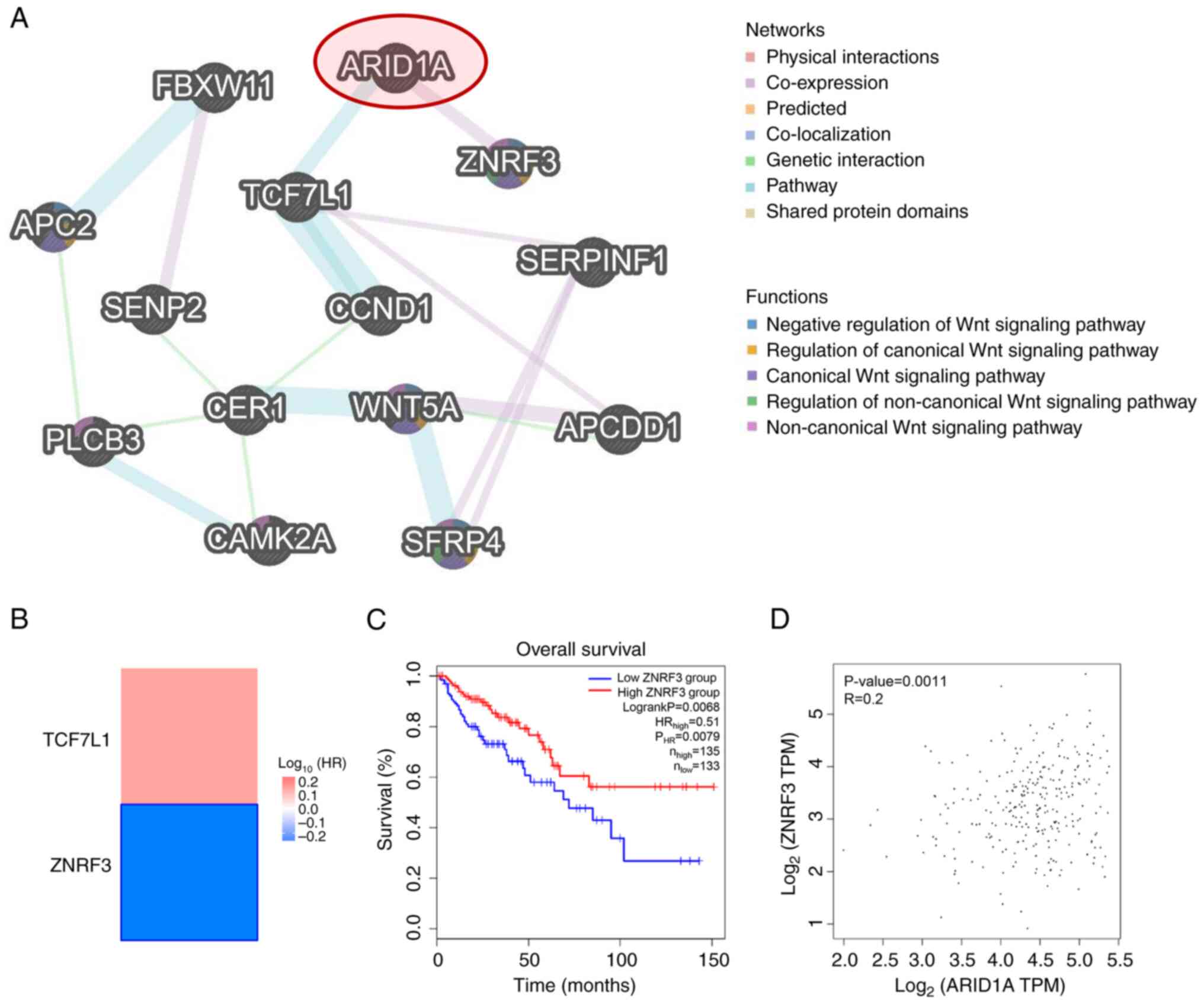

Involvement of ARID1A and altered

proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway

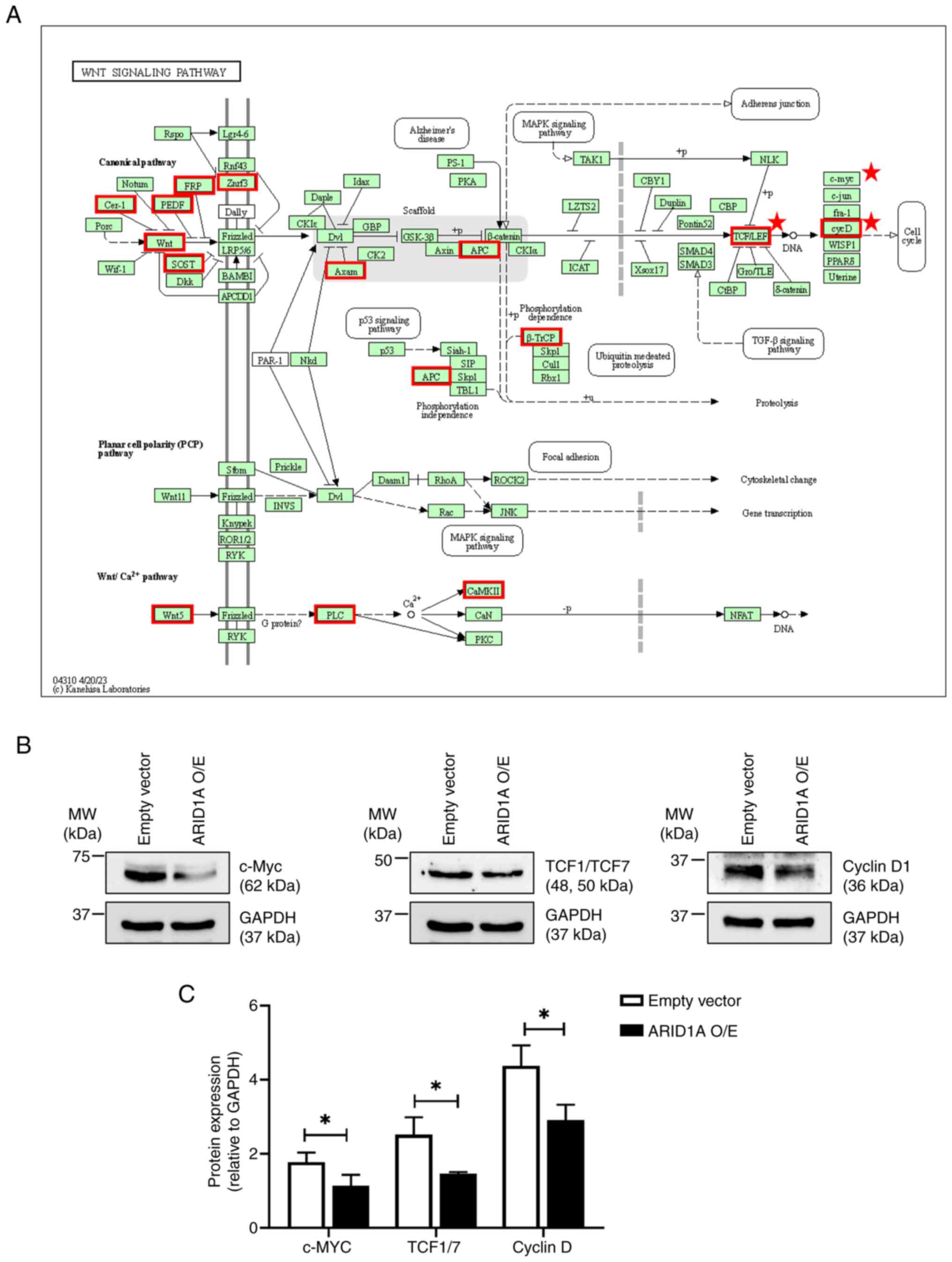

Functional enrichment analysis revealed the

potential involvement of ARID1A in the Wnt signaling pathway

(Fig. 3A). To assess this finding,

the protein levels of Wnt-target genes, including c-Myc, TCF1/TCF7

and cyclin D1 were compared between the ARID1A-overexpressing cells

and the empty vector control cells. The western blotting results

demonstrated that ARID1A overexpression resulted in significant

decreases of these Wnt-target genes compared with the empty vector

control cells, suggesting a potential regulatory role of ARID1A in

the Wnt signaling pathway (Fig. 3B and

C).

Relationship between ARID1A and

altered proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway

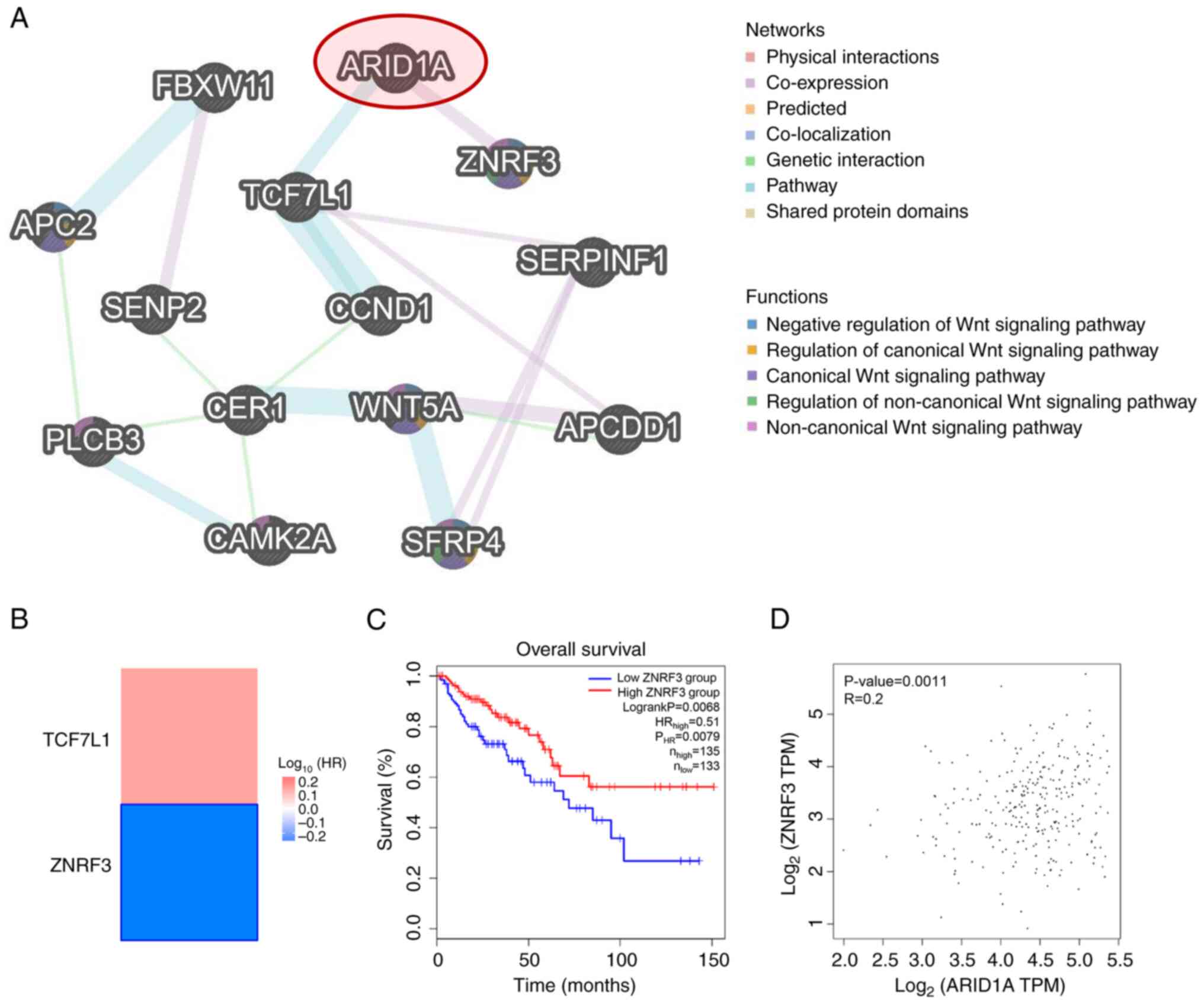

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the

roles of ARID1A in the aforementioned pathway, an interaction

network was constructed using GeneMANIA to assess the relationships

between ARID1A and the altered proteins involved in the Wnt

signaling pathway. The results demonstrated that these proteins

interact with each other mainly through ‘Physical interactions’

(77.64%), ‘Co-expression’ (8.01%) and ‘Predicted’ interactions

(5.37%). Notably, ARID1A was demonstrated to directly interact with

transcription factor 7 like 1 (TCF7L1) and ZNRF3 through ‘Pathway’

and ‘Co-expression’, respectively (Fig.

4A). Further analyses using the TCGA-COAD public dataset

revealed that only ZNRF3, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling

pathway (35), had prognostic

significance (Fig. 4B). Moreover,

patients with COAD with a low ZNRF3 expression demonstrated

significantly worse overall survival compared with those with a

high expression (Fig. 4C). ZNRF3

expression was also significantly correlated with ARID1A expression

in the database (Fig. 4D). These

findings highlight the potential relationship between ARID1A and

ZNRF3 in CRC carcinogenesis and progression.

| Figure 4.Association between ARID1A and

altered proteins involved in the Wnt signaling pathway. (A)

Interaction network of ARID1A and altered proteins involved in the

Wnt signaling pathway constructed using GeneMANIA. (B) Heatmap of

the HR of TCF7L1 and ZNRF3 for the overall survival of patients

with COAD, created using GEPIA2. The framed block indicates a

significant prognostic value. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for overall

survival of patients with COAD with different levels of ZNRF3

expression, plotted using GEPIA2. (D) Correlation between the

expression of ARID1A and ZNRF3 in COAD, analyzed using GEPIA2.

ARID1A, AT-rich interacting domain-containing protein 1A; TCF7L1,

transcription factor 7 like 1; ZNRF3, zinc and ring finger 3; COAD,

colon adenocarcinoma; GEPIA2, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis 2; HR, hazard ratio; TPM, transcripts per million. |

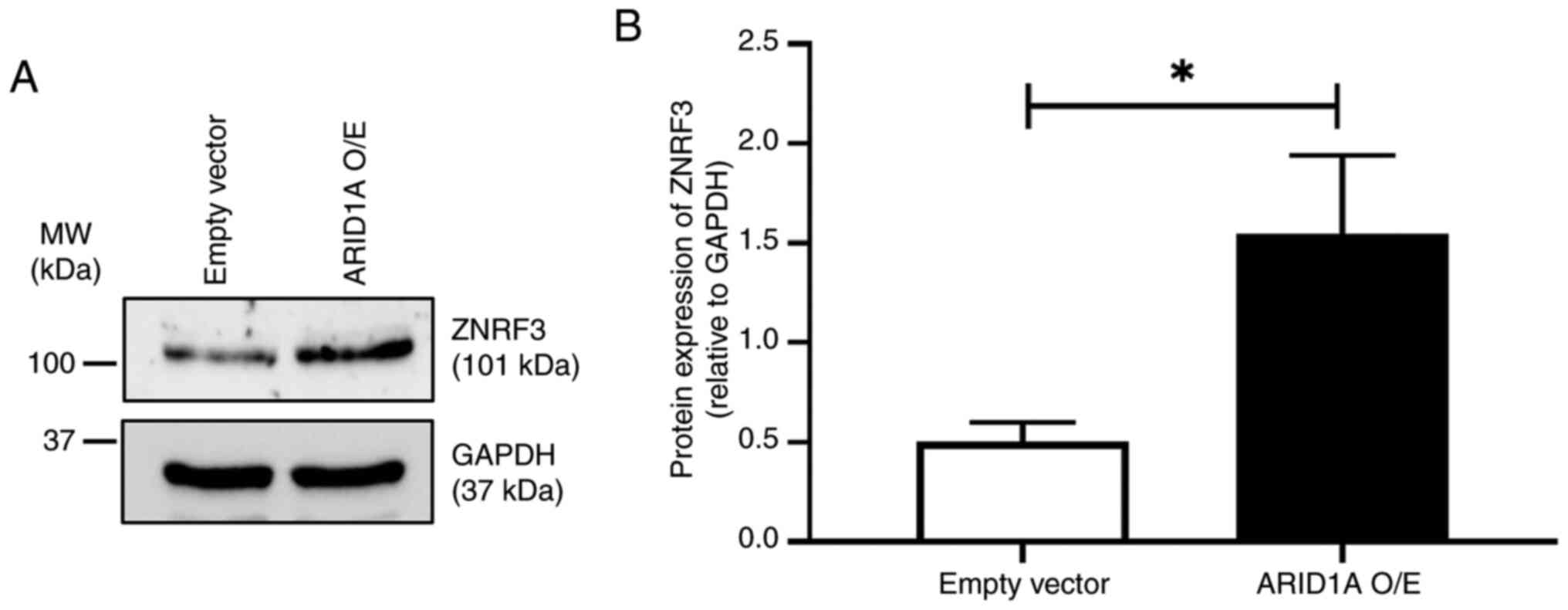

Expression of ZNRF3 protein in

ARID1A-overexpressing cells

Finally, the relationship between ARID1A and ZNRF3

was evaluated in the cells using western blotting. The results

revealed that ARID1A-overexpressing cells had a significantly

higher level of ZNRF3 protein expression compared with the empty

vector control, suggesting a positive regulatory axis between these

proteins (Fig. 5).

Discussion

ARID1A is an essential component of the SWI/SNF

chromatin remodeling complex, which serves a crucial role in

modulating the structure and accessibility of DNA (18). The diverse functions of ARID1A have

been extensively documented in previous studies. These functions

include chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation (5), oncogenic and tumor suppressor activity

(36), microsatellite instability

and immune checkpoint blockade (37), cell proliferation and

differentiation (38), and

epigenetic regulation (6). However,

the specific functions of ARID1A can vary depending on the cell

type and the cellular context (5,6,36–38).

Thus, an understanding of its precise function in a specific cancer

type is necessary.

In the present study, ARID1A-overexpressing SW48

cells were successfully established using lentivirus transduction.

Furthermore, western blotting demonstrated two immunoreactive bands

of ARID1A. ARID1A has a theoretical molecular weight of ~242 kDa

(UniProt accession no. O14497), corresponding to the upper band

detected at 250 kDa in the present study; however, several studies

have reported multiple bands of ARID1A using western blotting

(11,39,40).

Therefore, it appears that the multiple bands detected represent

ARID1A and possibly its degraded forms.

Previous studies have reported that ARID1A knockdown

promotes carcinogenic behaviors (16–18),

whilst its overexpression reverses such effects in CRC cells

(19). These findings underscored

the tumor suppressive role of ARID1A in CRC cells. Consequently,

the present study primarily focused on elucidating its underlying

mechanisms. Through proteomic analysis, 705 proteins that were

differentially altered in ARID1A-overexpressing cells compared with

empty vector control cells were identified. Functional enrichment

analysis revealed a significant enrichment of these altered

proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway, suggesting a potential

functional association between ARID1A and this pathway.

Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis was

chosen for the present study due to its cost-effectiveness and

ability to provide comprehensive protein expression profiles

without intricate sample preparation; however, it has limitations

such as susceptibility to technical variability and lower

sensitivity compared to labeled methods (25,26),

potentially missing low-abundance proteins. To address these issues

in future studies, rigorous sample preparation, use of internal

standards, and validation with complementary techniques such as

targeted proteomics or western blotting are recommended. Advances

in instrumentation and software are expected to further enhance the

reliability and accuracy of label-free proteomics (25,26).

The Wnt signaling pathway has been extensively

studied and is known to serve a crucial role in several cellular

processes associated with cancer, including cell proliferation,

apoptosis and EMT (41). A previous

study reported that the loss of ARID1A inhibited canonical

WNT/β-catenin activity in human gastric cancer organoid lines

(42). Downregulation of ARID1A and

the Notch/Wnt signaling pathway-related genes have also been

reported in gynecological tumors (43). In addition, ARID1A deletion in the

intestines of mice in a previous study led to a decrease in the

expression of target genes associated with the Wnt signaling

pathway, such as achaete-scute family bHLH transcription factor 2,

SRY-box transcription factor 9, axin 2, transcription factor 4, and

hes family bHLH transcription factor 1 (44). The data of the present study

demonstrated that ARID1A overexpression resulted in a decreased

expression of the Wnt-target genes in the cells. These findings

suggest that ARID1A may exert its tumor suppressive activity by

regulating the Wnt signaling pathway in CRC cells. However, the

expression of WNT/β-catenin signaling components, such as β-catenin

and its phosphorylated form, adenomatous polyposis coli, or

serine/threonine kinase GSK-3 and its phosphorylated form, were not

assessed in the present study. Clarifying the involvement of these

key markers in future studies would be essential to validate the

proposed relationship between ARID1A and the Wnt signaling pathway

in CRC.

Through proteomic analysis, a significant increase

of cyclin D1 in ARID1A-overexpressing cells was identified in the

present study; however, its decreased level was detected by western

blotting. Whilst this specific discrepancy in cyclin D1 levels

between LC-MS/MS and western blotting has not been reported before,

such discrepancies between these techniques are common in proteomic

studies (45–48). For instance, in a study by Pino

et al (47), discrepancies

between proteomic and western blot results were observed for

several proteins, which the authors attributed to differences in

sample preparation and detection techniques. Similarly, Zhang et

al (48) reported discrepancies

between 2D-difference gel electrophoresis and western blotting for

acyl-coA thioesterase 2. The study attributed these differences to

the low expression levels and issues with antibody specificity.

LC-MS/MS and western blotting differ in sample preparation,

detection methods and quantification approaches. LC-MS/MS

quantifies protein levels using retention time, mass-to-charge

ratio and ion intensities, whereas western blotting uses antibodies

to detect specific proteins (25,26).

The most likely explanation for this discrepancy is that cyclin D1

expression is influenced by post-translational modifications (PTMs)

and isoforms. Cyclin D1 is a key regulator in cell cycle control

and exists in two major isoforms (cyclin D1a and b) along with

other truncating variants and PTMs (49,50).

Aberrant expressions of cyclin D1 isoforms and variants are

involved in the pathogenesis of cancer (49,50).

Therefore, it is plausible that the observed increase in protein

abundance by LC-MS/MS may include specific isoforms or PTMs that

were not semi-quantified by western blotting. The observed

discrepancy in the present study may indicate a potential

alteration of cyclin D1 isoforms and PTMs induced by ARID1A

overexpression.

Among the altered proteins associated with the Wnt

signaling pathway, ARID1A was revealed to directly interact with

TCF7L1 and ZNRF3 in the present study; however, only the expression

of ZNRF3 had a significant prognostic impact on the overall

survival of patients with COAD. ZNRF3 is a transmembrane E3

ubiquitin ligase that acts as a negative regulator of the Wnt

signaling pathway (35). A previous

study reported an association between ZNRF3 expression and survival

outcomes in patients with CRC, with ZNRF3 overexpression promoting

the apoptosis and inhibiting the proliferation of CRC cells

(51). In the present study,

proteomic analysis identified a significant increase in ZNRF3

levels in ARID1A-overexpressing cells. Interaction network analysis

revealed a potential interaction with ARID1A through co-expression.

The TCGA-COAD dataset demonstrated a positive correlation between

ARID1A and ZNRF3 expression, further confirmed by western blotting.

Hence, these findings suggest that the interaction between ARID1A

with ZNRF3 may contribute to the carcinogenesis and progression of

CRC. However, the present study did not confirm the physical

interaction between these two proteins by co-immunoprecipitation or

double immunofluorescence staining experiments. Further studies are

needed to validate these interactions.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has

reported a direct relationship between ARID1A and ZNRF3. A proposed

mechanism for how ARID1A overexpression may result in increased

ZNRF3 expression is through transcriptional regulation. ARID1A

functions as a transcriptional regulator, modulating chromatin

accessibility and transcription factor binding (4). It is possible that ARID1A could

directly bind or interact with transcriptional co-factors or

chromatin remodelers at the ZNRF3 promoter, leading to enhanced

transcription and an increase in ZNRF3 mRNA levels. Alternatively,

ARID1A may interact with other proteins that stabilize ZNRF3 mRNA

or prevent its degradation, leading to increased ZNRF3 protein

levels. Further experimental studies are needed to elucidate the

precise molecular mechanisms underlying this interaction.

Whilst the present study provides insights into the

role of ARID1A in colon cancer and its potential interactions with

the Wnt signaling pathway, several limitations should be

acknowledged. First, the study primarily focused on ARID1A

overexpression and its effects on protein expression profiles in

one colon cancer cell line (SW48). Further studies in CRC cells

with different molecular characteristics are warranted to validate

the present findings across a broader spectrum. Additionally, the

lack of physiological assays, such as proliferation, migration,

invasion, apoptosis and cell cycle progression, is a limitation.

These assays are crucial to comprehensively understand the

functional consequences of ARID1A overexpression and its

relationship with the Wnt signaling pathway in CRC carcinogenesis

and metastasis. Experiments involving genetic manipulation or

inhibitor treatment specific to Wnt signaling molecules are also

necessary to obtain a deeper understanding. Furthermore, the

observed discrepancy between proteomic and western blot analyses

regarding cyclin D1 expression needs to be validated by different

experimental approaches. Finally, further investigations are

required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the regulatory

axis between ARID1A and ZNRF3 in CRC.

In conclusion, a set of 705 differentially altered

proteins were identified in ARID1A-overexpressing cells compared

with control cells. These altered proteins were mainly involved in

the Wnt signaling pathway. Bioinformatics analyses also highlighted

a potential functional interaction between ARID1A and ZNRF3 in CRC

carcinogenesis and progression. A better understanding of the role

of ARID1A in CRC would help in the development of targeted

therapies and diagnostic approaches for CRC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research received funding support from the National

Science, Research and Innovation Fund via the Program Management

Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research

and Innovation (grant no. B05F640168).

Availability of data and materials

The raw mass-spectrometric data generated in the

present study may be found in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via

the jPOST repository (https://repository.jpostdb.org) (52) under accession numbers PXD052413 in

the ProteomeXchange and JPST003117 in the jPOST repository, or at

the following URLs: https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD052413

and https://repository.jpostdb.org/entry/JPST003117,

respectively. The other data generated in the current study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SA and KS contributed to the conception and design

of the study, performed experiments, data analysis and

visualization, and were major contributors to the writing of the

manuscript. SW, AM and AR performed experiments and data analysis.

SR performed the proteomic analysis. NS contributed to the

conception and design of the study, data analysis, supervision,

funding acquisition and manuscript editing. SA and NS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhao S, Wu W, Jiang Z, Tang F, Ding L, Xu

W and Ruan L: Roles of ARID1A variations in colorectal cancer: A

collaborative review. Mol Med. 28:422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wilsker D, Probst L, Wain HM, Maltais L,

Tucker PW and Moran E: Nomenclature of the ARID family of

DNA-binding proteins. Genomics. 86:242–251. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang X, Nagl NG, Wilsker D, Van Scoy M,

Pacchione S, Yaciuk P, Dallas PB and Moran E: Two related ARID

family proteins are alternative subunits of human SWI/SNF

complexes. Biochem J. 383:319–325. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu RC, Wang TL and Shih IeM: The emerging

roles of ARID1A in tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther. 15:655–664.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu X, Li Z, Wang Z, Liu F, Zhang L, Ke J,

Xu X, Zhang Y, Yuan Y, Wei T, et al: Chromatin remodeling induced

by ARID1A loss in lung cancer promotes glycolysis and confers JQ1

vulnerability. Cancer Res. 82:791–804. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wilson MR, Reske JJ, Holladay J, Neupane

S, Ngo J, Cuthrell N, Wegener M, Rhodes M, Adams M, Sheridan R, et

al: ARID1A mutations promote P300-dependent endometrial invasion

through super-enhancer hyperacetylation. Cell Rep. 33:1083662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang T, Chen X, Su C, Ren S and Zhou C:

Pan-cancer analysis of ARID1A alterations as biomarkers for

immunotherapy outcomes. J Cancer. 11:776–780. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fontana B, Gallerani G, Salamon I, Pace I,

Roncarati R and Ferracin M: ARID1A in cancer: Friend or foe? Front

Oncol. 13:11362482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guan B, Gao M, Wu CH, Wang TL and Shih

IeM: Functional analysis of in-frame indel ARID1A mutations reveals

new regulatory mechanisms of its tumor suppressor functions.

Neoplasia. 14:986–993. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mullen J, Kato S, Sicklick JK and Kurzrock

R: Targeting ARID1A mutations in cancer. Cancer Treat Rev.

100:1022872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Somsuan K, Peerapen P, Boonmark W,

Plumworasawat S, Samol R, Sakulsak N and Thongboonkerd V:

ARID1A knockdown triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and carcinogenesis features of renal cells: Role in renal cell

carcinoma. FASEB J. 33:12226–12239. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xu S and Tang C: The role of ARID1A

in tumors: Tumor initiation or tumor suppression? Front Oncol.

11:7451872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wei XL, Wang DS, Xi SY, Wu WJ, Chen DL,

Zeng ZL, Wang RY, Huang YX, Jin Y, Wang F, et al: Clinicopathologic

and prognostic relevance of ARID1A protein loss in colorectal

cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 20:18404–18412. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ye J, Zhou Y, Weiser MR, Gönen M, Zhang L,

Samdani T, Bacares R, DeLair D, Ivelja S, Vakiani E, et al:

Immunohistochemical detection of ARID1A in colorectal carcinoma:

Loss of staining is associated with sporadic microsatellite

unstable tumors with medullary histology and high TNM stage. Hum

Pathol. 45:2430–2436. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Guan X, Cui L, Ruan Y, Fang L, Dang T,

Zhang Y and Liu C: Heterogeneous expression of ARID1A in colorectal

cancer indicates distinguish immune landscape and efficacy of

immunotherapy. Discov Oncol. 15:922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xie C, Fu L, Han Y, Li Q and Wang E:

Decreased ARID1A expression facilitates cell proliferation and

inhibits 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in colorectal carcinoma.

Tumour Biol. 35:7921–7927. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Peerapen P, Sueksakit K, Boonmark W,

Yoodee S and Thongboonkerd V: ARID1A knockdown enhances

carcinogenesis features and aggressiveness of Caco-2 colon cancer

cells: An in vitro cellular mechanism study. J Cancer. 13:373–384.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Baldi S, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Safi M, Khamgan

H, Wu H, Zhang M, Qian Y, Gao Y, Shopit A, et al: ARID1A

downregulation promotes cell proliferation and migration of colon

cancer via VIM activation and CDH1 suppression. J Cell Mol Med.

26:5984–5997. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Erfani M, Zamani M, Hosseini SY,

Mostafavi-Pour Z, Shafiee SM, Saeidnia M and Mokarram P: ARID1A

regulates E-cadherin expression in colorectal cancer cells: A

promising candidate therapeutic target. Mol Biol Rep. 48:6749–6756.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kwon YW, Jo HS, Bae S, Seo Y, Song P, Song

M and Yoon JH: Application of proteomics in cancer: Recent trends

and approaches for biomarkers discovery. Front Med (Lausanne).

8:7473332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Aluksanasuwan S, Somsuan K, Ngoenkam J,

Chiangjong W, Rongjumnong A, Morchang A, Chutipongtanate S and

Pongcharoen S: Knockdown of heat shock protein family D member 1

(HSPD1) in lung cancer cell altered secretome profile and

cancer-associated fibroblast induction. Biochimica Biophys Acta Mol

Cell Res. 1871:1197362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Guan B, Wang TL and Shih IeM: ARID1A, a

factor that promotes formation of SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin

remodeling, is a tumor suppressor in gynecologic cancers. Cancer

Res. 71:6718–6727. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Stewart SA, Dykxhoorn DM, Palliser D,

Mizuno H, Yu EY, An DS, Sabatini DM, Chen IS, Hahn WC, Sharp PA, et

al: Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary

cells. RNA. 9:493–501. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL and

Randall RJ: Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J

Biol Chem. 193:265–275. 1951. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhu W, Smith JW and Huang CM: Mass

spectrometry-based label-free quantitative proteomics. J Biomed

Biotechnol. 2010:8405182010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Neilson KA, Ali NA, Muralidharan S,

Mirzaei M, Mariani M, Assadourian G, Lee A, van Sluyter SC and

Haynes PA: Less label, more free: Approaches in label-free

quantitative mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 11:535–553. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tyanova S, Temu T and Cox J: The MaxQuant

computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun

proteomics. Nat Protoc. 11:2301–2319. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tyanova S, Temu T, Sinitcyn P, Carlson A,

Hein MY, Geiger T, Mann M and Cox J: The perseus computational

platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat

Methods. 13:731–740. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang da W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID

bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 4:44–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Huang da W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive

functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res.

37:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhao T and Wang Z: GraphBio: A shiny web

app to easily perform popular visualization analysis for omics

data. Front Genet. 13:9573172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O,

Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT,

et al: The GeneMANIA prediction server: Biological network

integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function.

Nucleic Acids Res(Web Server issue). 38:W214–W220. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA,

Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C and Stuart JM: The cancer genome

atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 10:1113–1120. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W556–W560. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange

DE, van de Wetering M, van Es JH, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Maurice MM

and Clevers H: Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase

that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 488:665–669.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sun X, Wang SC, Wei Y, Luo X, Jia Y, Li L,

Gopal P, Zhu M, Nassour I, Chuang JC, et al: Arid1a has

context-dependent oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions in liver

cancer. Cancer Cell. 32:574–589.e6. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Shen J, Ju Z, Zhao W, Wang L, Peng Y, Ge

Z, Nagel ZD, Zou J, Wang C, Kapoor P, et al: ARID1A deficiency

promotes mutability and potentiates therapeutic antitumor immunity

unleashed by immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Med. 24:556–562. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu X, Dai SK, Liu PP and Liu CM: Arid1a

regulates neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation and

differentiation during cortical development. Cell Prolif.

54:e131242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yoodee S, Peerapen P, Plumworasawat S and

Thongboonkerd V: ARID1A knockdown in human endothelial cells

directly induces angiogenesis by regulating angiopoietin-2

secretion and endothelial cell activity. Int J Biol Macromol.

180:1–13. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yoodee S, Peerapen P, Plumworasawat S,

Malaitad T and Thongboonkerd V: Identification and characterization

of ARID1A-interacting proteins in renal tubular cells and their

molecular regulation of angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 21:8622023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhao H, Ming T, Tang S, Ren S, Yang H, Liu

M, Tao Q and Xu H: Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer: Pathogenic

role and therapeutic target. Mol Cancer. 21:1442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lo YH, Kolahi KS, Du Y, Chang CY,

Krokhotin A, Nair A, Sobba WD, Karlsson K, Jones SJ, Longacre TA,

et al: A CRISPR/Cas9-engineered ARID1A-deficient human

gastric cancer organoid model reveals essential and nonessential

modes of oncogenic transformation. Cancer Discov. 11:1562–1581.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Vaicekauskaitė I, Dabkevičienė D, Šimienė

J, Žilovič D, Čiurlienė R, Jarmalaitė S and Sabaliauskaitė R:

ARID1A, NOTCH and WNT signature in gynaecological tumours.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:58542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hiramatsu Y, Fukuda A, Ogawa S, Goto N,

Ikuta K, Tsuda M, Matsumoto Y, Kimura Y, Yoshioka T, Takada Y, et

al: Arid1a is essential for intestinal stem cells through Sox9

regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:1704–1713. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Heunis T, Lamoliatte F, Marín-Rubio JL,

Dannoura A and Trost M: Technical report: Targeted proteomic

analysis reveals enrichment of atypical ubiquitin chains in

contractile murine tissues. J Proteomics. 229:1039632020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hong X, Wang T, Du J, Hong Y, Yang CP,

Xiao W, Li Y, Wang M, Sun H and Deng ZH: ITRAQ-based quantitative

proteomic analysis reveals that VPS35 promotes the expression of

MCM2-7 genes in HeLa cells. Sci Rep. 12:97002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Pino JMV, Nishiduka ES, da Luz MHM, Silva

VF, Antunes HKM, Tashima AK, Guedes PLR, de Souza AAL and Lee KS:

Iron-deficient diet induces distinct protein profile related to

energy metabolism in the striatum and hippocampus of adult rats.

Nutr Neurosci. 25:207–218. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang X, Morikawa K, Mori Y, Zong C, Zhang

L, Garner E, Huang C, Wu W, Chang J, Nagashima D, et al: Proteomic

analysis of liver proteins of mice exposed to 1,2-dichloropropane.

Arch Toxicol. 94:2691–2705. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Van Dross R, Browning PJ and Pelling JC:

Do truncated cyclins contribute to aberrant cyclin expression in

cancer? Cell Cycle. 5:472–477. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wang J, Su W, Zhang T, Zhang S, Lei H, Ma

F, Shi M, Shi W, Xie X and Di C: Aberrant cyclin D1 splicing in

cancer: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell

Death Dis. 14:2442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yu N, Zhu H, Tao Y, Huang Y, Song X, Zhou

Y, Li Y, Pei Q, Tan Q and Pei H: Association between prognostic

survival of human colorectal carcinoma and ZNRF3 expression. Onco

Targets Ther. 9:6679–6687. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Okuda S, Watanabe Y, Moriya Y, Kawano S,

Yamamoto T, Matsumoto M, Takami T, Kobayashi D, Araki N, Yoshizawa

AC, et al: jPOSTrepo: An international standard data repository for

proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:D1107–D1111. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|