Introduction

Liposarcoma (LPS) is one of the most common types of

soft tissue sarcoma (1–3). Among its four subtypes,

well-differentiated LPS (WDLPS) and dedifferentiated LPS (DDLPS)

share similar genomic changes, notably the amplification of the

12q13-15 chromosomal region, where mouse double minute 2 homolog

(MDM2) is the primary oncogene. WDLPS rarely metastasizes and can

remain stable for several years. By contrast, DDLPS is a highly

aggressive disease characterized by frequent local recurrence and

distant metastasis (4). Wide

surgical excision with curative intent is the preferred treatment

for localized disease. However, for advanced DDLPS, despite

recommended first-line chemotherapy with doxorubicin (5) and second-line options including

eribulin or trabectedin (6–8), treatment outcomes remain poor.

Ferroptosis is a form of cell death characterized by

the oxidative modification of phospholipid membranes, resulting in

the accumulation of lipid-based reactive oxygen species (ROS)

(9–11). Cysteine metabolism is crucial in the

regulation of ferroptosis (9–11). The

cystine-glutamate antiporter (xCT), composed of solute carrier

family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and SLC3A2, facilitates the uptake of

cystine from the extracellular environment. Once imported, cystine

is reduced to cysteine, a key component of the tripeptide

glutathione. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) requires glutathione

as a cofactor to reduce lipid peroxidation and prevent ferroptosis

(12,13). Inactivation of GPX4, either through

cystine deprivation by the xCT inhibitor erastin or direct

inhibition by the GPX4 inhibitor Ras-selective lethal small

molecule 3 (RSL3), leads to the accumulation of lipid-based ROS and

ultimately ferroptotic cell death (13,14).

Few studies have explored the role of ferroptosis in

LPS, a tumor originating from adipocytic differentiation. Tumor

protein p53 (TP53), a well-known tumor suppressor mutated in nearly

half of all cancers (15), plays a

key role in regulating ferroptosis through multiple, sometimes

paradoxical, pathways. These include suppressing SLC7A11 expression

to promote ferroptosis (16);

upregulating 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

(HMGCR), which produces molecules with anti-ferroptotic properties

(17); and inhibiting

dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP4)-dependent lipid peroxidation, thereby

reducing ferroptosis (18). MDM2,

the key oncogene in DDLPS (19),

and its homolog MDM4 (20)

negatively regulate TP53 (21–24),

potentially influencing ferroptotic death through both

TP53-dependent and TP53-independent mechanisms (25). These findings suggest that exploring

the ferroptosis pathway may lead to the discovery of novel

therapeutic strategies, with MDM2 playing a critical role in the

regulation of ferroptosis in DDLPS.

In the present study, an investigation of the

expression of genes involved in the ferroptosis pathway in DDLPS

was performed via bioinformatics, to identify differentially

expressed ferroptosis-related genes. Additionally, the sensitivity

of DDLPS cell lines to the ferroptosis-inducing agents erastin and

RSL3 was investigated. The effects of nutlin-3, an MDM2 inhibitor,

as a co- or pre-treatment with erastin or RSL3 were also

investigated, and the effect of TP53 knockdown (KD) was

explored.

Materials and methods

Exploration of ferroptosis-related

gene expression regulated by the MDM2-TP53 pathway through

bioinformatics analysis

Bioinformatics analysis was performed as previously

described (26). Microarray data

from the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 and Affymetrix Human

Genome U133A platforms were obtained from the National Center for

Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). The datasets

comprised DDLPS samples from GSE21050 (U133 Plus 2.0) (27) and GSE30929 (U133A) (28), WDLPS samples from GSE20559 (U133

Plus 2.0) (29) and GSE30929

(U133A) (28), and adipose tissue

samples from GSE41168 (U133 Plus 2.0) (30) and GSE35710 (U133A) (31). The gene expression data were

normalized using dChip (32,33).

Specific genes associated with ferroptosis were selected, and their

expression levels were expressed as Z-scores following Z-score

transformation.

Cell lines and reagents

DDLPS cell lines LPS853 and NDDLS-1, provided by Dr

Fletcher JA (Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital,

Boston, MA 02115, USA) and Dr Ariizumi (Division of Orthopedic

Surgery, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental

Sciences, Niigata City, Niigata 951-8510, Japan), respectively,

were used as in vitro models to test the efficacy of various

agents. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 Medium (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum

(Corning, Inc.) and Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The

xCT inhibitor erastin (CAS no. 571203-78-6; Cayman Chemical

Company), GPX4 inhibitor RSL3 (CAS no. 1219810-16-8; Cayman

Chemical Company) and HMGCR inhibitors lovastatin (S2061; Selleck

Chemicals) and simvastatin (S1792; Selleck Chemicals) were

evaluated for their ferroptosis-inducing effects. Nutlin-3a (S8059;

Selleck Chemicals) was used as an MDM2 antagonist; this is the

active enantiomer of nutlin-3, and for simplicity is referred to as

nutlin-3 throughout the manuscript. Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1; CAS no.

347174-05-4; Cayman Chemical Company) was used to inhibit

ferroptosis. The antibodies used for immunoblotting were as

follows: p53 (cat. no. 2527S; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), MDM2 (cat. no. 86934S; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), SLC7A11 (cat. no. A13685; 1:1,000; ABclonal Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), GPX4 (cat. no. A1933; 1:1,000; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

SLC3A2/CD98hc (cat. no. A3658; 1:1,000; ABclonal Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), 4EBP1 (cat. no. 9644; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-4EBP1 (cat. no. 9459; 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), p70S6 (cat. no. 9202; 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), p-p70S6 (cat. no. 9205; 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) and β-actin (cat. no. ab6276; 1:1,000;

Abcam).

Lipid peroxidation assay

The DDLPS cell lines (2.5×105 cells/well)

were seeded in six-well plates and incubated at 37°C with different

concentrations of test agents for specific durations. For single

agent treatment, cells were treated with erastin (12 µM for

NDDLS-1, 20 µM for LPS853), RSL3 (0.2 µM for both), lovastatin (18

µM for both), or simvastatin (18 µM for both) for 24 h. For

combination with Fer-1, cells were treated with erastin (8 µM for

LPS853, 20 µM for NDDLS-1), or RSL3 (0.05 µM for both), and

combined with Fer-1 (4, 6, or 8 µM), with co-treatment of erastin

and Fer-1 for 48 h and RSL3 and Fer-1 for 4 h. For combination with

nutlin-3, cells were treated with erastin (8 or 16 µM for LPS853,

12 or 20 µM for NDDLS-1), or RSL3 (0.2 or 0.4 µM for both), and

combined with nutlin-3 (10 µM for both). Co-treatment with erastin

and nutlin-3 or RSL3 and nutlin-3 was performed for 24 h, whereas

in the sequential treatment, cells were first exposed to nutlin-3

for 24 h, followed by treatment with either erastin or RSL3 for an

additional 24 h. After treatment, cells were incubated with 2 µM

BODIPY 581/591 C11 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at

37°C. After this, the cells were collected, resuspended in 500 µl

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and analyzed using a BD FACSCanto™

II flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences) (34). Data were analyzed using FlowJo

software (version 7.6; FlowJo LLC). The experiment was performed in

triplicate.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were plated in 96-well

plates at a concentration of 5,000 cells in 100 µl/well. The

following day, different concentrations of the test agents were

added to individual wells and incubated at 37°C for the appropriate

duration. The treatment conditions were as follows: for single

agent treatment, Erastin (4, 8, 12, 16, 20 µM), RSL3 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5

µM), lovastatin (6, 12, 18, 24, 30 µM), or simvastatin (6, 12, 18,

24, 30 µM) was used for 24-h treatment; for combination with Fer-1,

Erastin (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 µM) or RSL3 (0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05

µM) were combined with Fer-1 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 µM) for 48-h treatment;

for combination with nutlin-3, Erastin (3, 6, 9, 12, 15 µM) or RSL3

(0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05 µM) were combined with nutlin-3 (4,

8, 12, 16, 20 µM). Co-treatment with erastin and nutlin-3 or RSL3

and nutlin-3 was performed for 24 h, whereas in the sequential

treatment, cells were first exposed to nutlin-3 for 24 h, followed

by treatment with either erastin or RSL3 for an additional 24 h.

After incubation, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well,

followed by incubation for 1.5–2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was

measured for each well using a microplate reader. The combination

index (CI) for two-drug combinations was calculated using CalcuSyn

software (Biosoft), where CI <1, CI=1 and CI >1 indicate

synergism, additivity and antagonism, respectively. All experiments

were performed in triplicate (35).

Apoptosis assessment

Apoptosis was assessed as previously described

(26). Specifically, for single

agent treatment, cells (1×105 cells/well) were treated

with erastin (2, 4, 6, 8 µM for LPS853, 3, 6, 9, 12 µM for NDDLS-1)

or RSL3 (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 µM for both), with LPS853 cells exposed

to erastin for 24 h, NDDLS-1 cells exposed to erastin for 48 h, and

both cell lines treated with RSL3 for 24 h. For combination with

nutlin-3, cells (1×105 cells/well) were treated with

erastin (10 µM), or RSL3 (0.4 µM), and combined with nutlin-3 (10

µM). Co-treatment with erastin and nutlin-3 or RSL3 and nutlin-3

was performed for 24 h, whereas in the sequential treatment, cells

were first exposed to nutlin-3 for 24 h, followed by treatment with

either erastin or RSL3 for an additional 24 h. After treatment,

cells were washed with 1X PBS and resuspended in 100 µl staining

solution containing annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and

propidium iodide in HEPES buffer (BD Pharmingen). The cells were

incubated at room temperature for 15 min, then diluted in 1X

annexin V-binding buffer (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed by flow

cytometry with a BD FACSCanto II system, BD FACSDiva Software

v8.0.2 operating software (all BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (version

7.6; FlowJo LLC) analysis software. The experiment was performed in

triplicate.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described

(36). Cells were treated with

erastin (8 µM), RSL3 (0.2 µM), or nutlin-3 (12 µM), either as

single agent or various combinations, for 24 h. After treatment,

cultured monolayer cells were rinsed with PBS and lysed using RIPA

Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

cell suspensions were then incubated at 4°C for 30 min, followed by

centrifugation at 15,974 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Total protein

concentrations were measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Proteins (50 µg per lane) were

separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride (PVDF) membranes (PerkinElmer, Inc.). The membranes were

blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Bionovas Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 30 min. Primary antibodies were

incubated at 4°C overnight, while secondary antibodies were

incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Primary and secondary

antibodies were prepared in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The

secondary antibodies, Anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. 7074S) and

Anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 7076S), were diluted at 1:4,500 and

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. The immunoreactive

bands were visualized using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP

Substrate (MilliporeSigma) and a UVP ChemStudio PLUS Touch Western

Blot Imaging System (Analytik Jena AG). Densitometric analysis was

performed using ImageJ software (version 1.51, National Institutes

of Health).

Cystine uptake assay

Cystine uptake was measured using a Cystine Uptake

Assay Kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Cells (1×104 cells/well)

were seeded in a black 96-well plate for 24 h. The medium was then

replaced and cells were treated with single agent erastin (40 µM)

or nutlin-3 (10 µM) or combination for the time period specified by

the manufacturer. After treatment, the culture medium was

aspirated, and the cells were washed three times with serum-free

RPMI 1640 prior to incubation in serum-free RPMI 1640 for 5 min at

37°C. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Cystine Analog

Solution (selenocystine) from the kit in serum-free RPMI 1640 for

30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence

microplate reader with an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an

emission wavelength of 535 nm.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated

knockdown (KD) of TP53

The TP53 KD experiment was conducted using the

ON-TARGETplus system (Horizon Discovery, Ltd.). Cells

(1×106) were first treated with DharmaFECT 1

Transfection Reagent (cat. no. T-2001-03; GE Healthcare Dharmacon,

Inc.; ON-TARGETplus system) and subsequently transfected with

ON-TARGETplus Human TP53 (cat. no. 7157) siRNA-SMARTpool (cat. no.

L-003329-00-0005) target sequences: GAAAUUUGCGUGUGGAGUA,

GUGCAGCUGUGGGUUGAUU, GCAGUCAGAUCCUAGCGUC and GGAGAAUAUUUCACCCUUC;

20 µM) or the ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Pool (cat. no.

D-001810-10-20; GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Inc.) target sequences:

UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA, UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUGA, UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCUGA, and

UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA; 20 µM as a negative control. However, the

sense and antisense strand sequences were not provided for either

siRNA. Following transfection, cells were incubated at 37°C for 48

h.

The KD efficiency of TP53 was confirmed by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). RNA extraction was

performed using the LabPrep™ RNA Plus Mini Kit (LabPrep). RT was

carried out using the HiScript™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit

(Bionovas Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following primers: TP53

forward, 5′-GCCATCTACAAGCAGTCACAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCATCCAAATACTCCACACGC-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-GCCAAGGTCATCCATGACAACT-3′ and reverse,

5′-GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTT-3′. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 36 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec

and 55°C for 60 sec. Amplification and analysis were performed

using the QuantStudio3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Gene copy numbers were calculated

according to the 2−ΔΔCq method (37).

Statistical analysis

Differences in the expression of genes among the

DDLPS, WDLPS and adipose tissues were analyzed using the

Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn's post hoc test for pairwise

comparisons. In the cell-based experiments, differences between two

groups were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test and among

multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was

conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS

Inc.).

Results

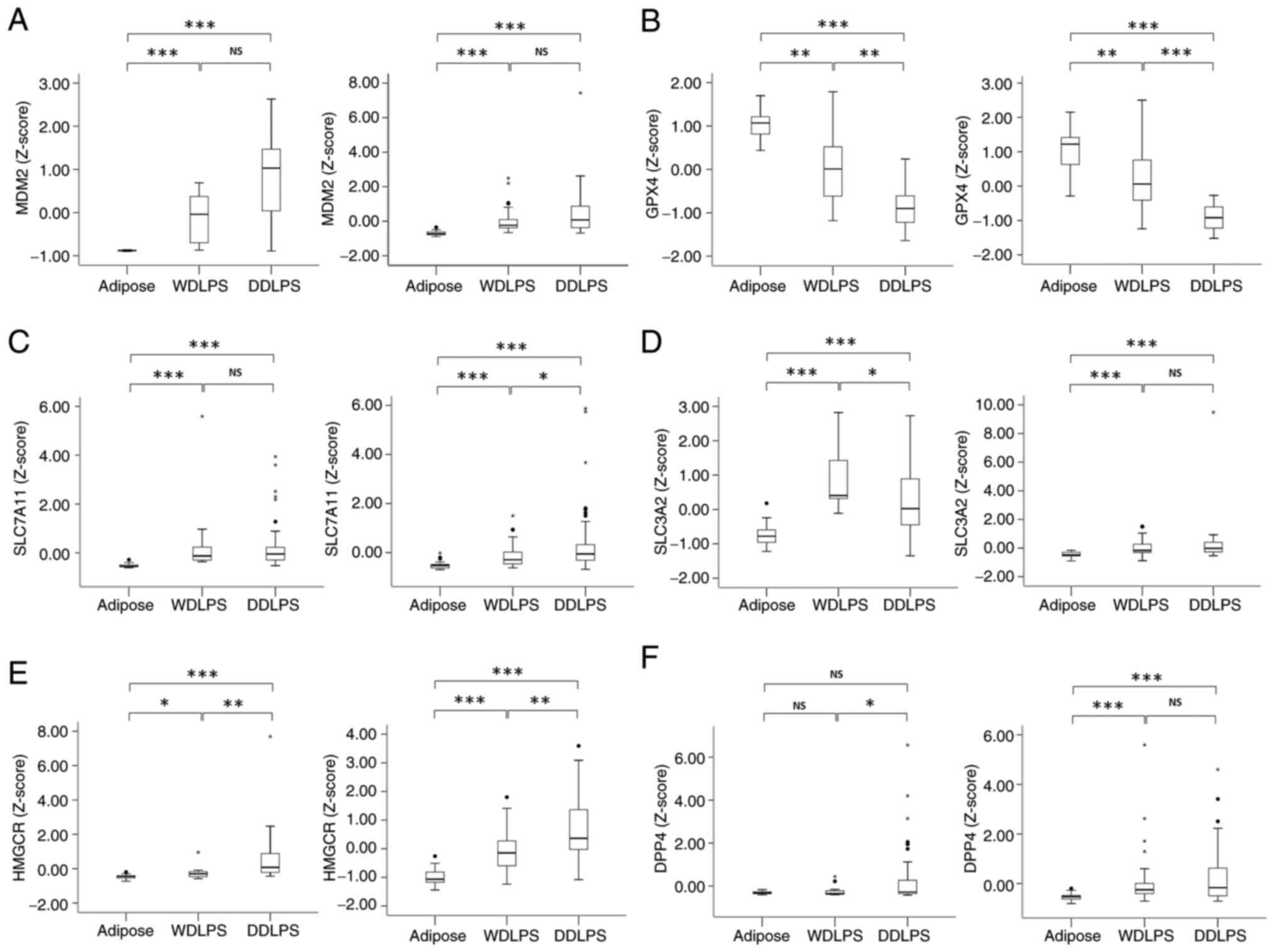

Ferroptosis-related genes regulated by

the MDM2-TP53 pathway are differentially expressed in DDLPS

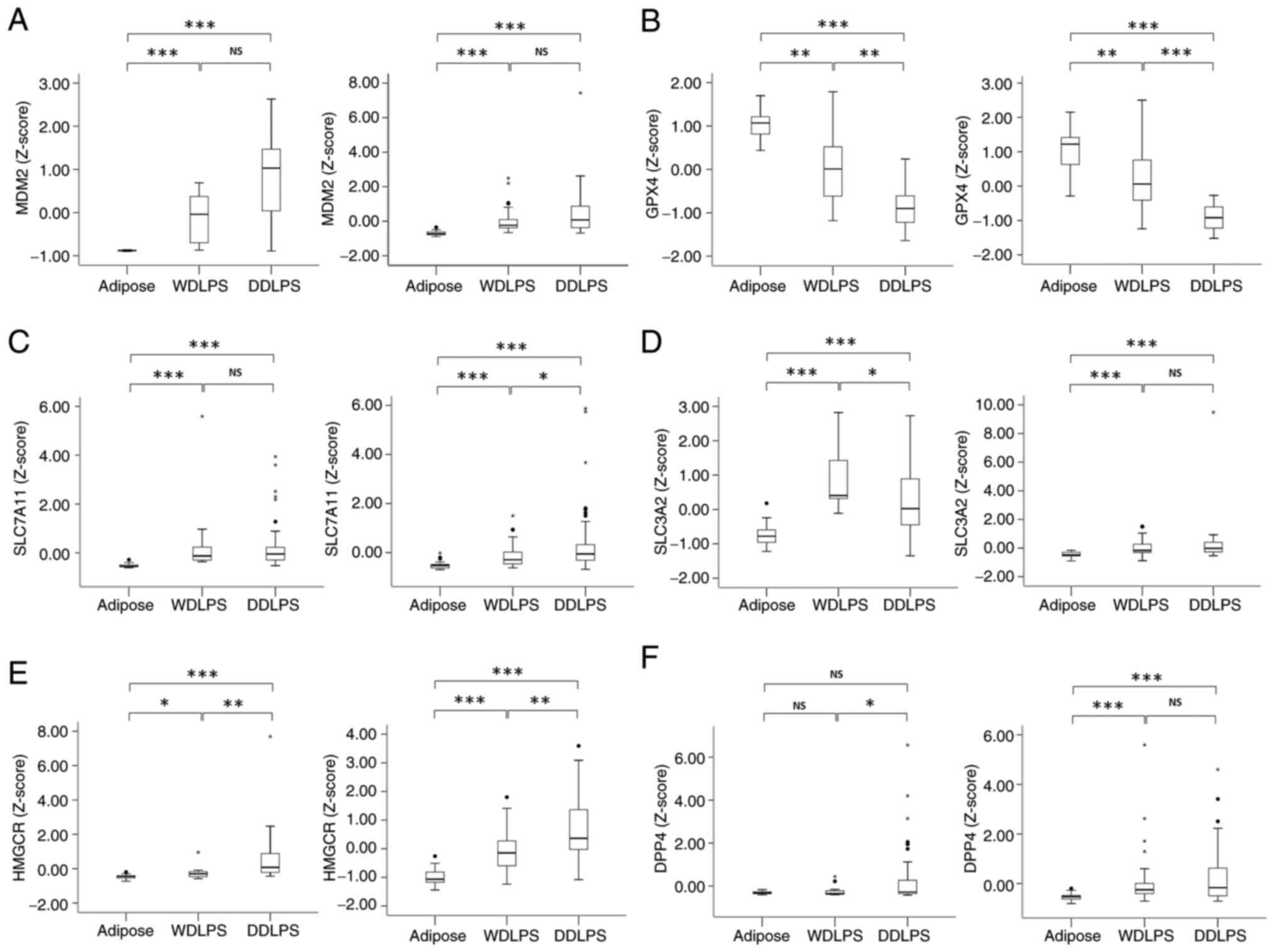

Publicly available data were analyzed to identify

potential differences in the expression of ferroptosis-related

genes regulated by the MDM2-TP53 pathway. The expression levels of

MDM2 were significantly upregulated in WDLPS and DDLPS compared

with those in adipose tissue (Fig.

1A). By contrast, the GPX4 expression levels in DDLPS were

significantly lower than those in both adipose tissue and WDLPS

(Fig. 1B), which may contribute to

a pro-ferroptosis phenotype. The expression levels of HMGCR

observed in DDLPS were higher compared with those in adipose tissue

and WDLPS (Fig. 1E), potentially

contributing to an anti-ferroptosis effect. The expression levels

of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 were higher in both types of LPS compared

with those in adipose tissue. However, the differential expression

of DPP4 in adipose tissue, WDLPS and DDLPS was inconsistent between

the two platforms (Fig. 1C, D and

F).

| Figure 1.Comparison of the expression levels

of six ferroptosis-related genes among adipose, WDLPS and DDLPS

tissues. Expression levels of (A) MDM2, (B) GPX4, (C) SLC7A11, (D)

SLC3A2, (E) HMGCR and (F) DPP4. In each panel, data in the left

graph are from GSE21050, GSE20559 and GSE41168 (U133 Plus 2.0) and

data in the right graph are from GSE30929 and GSE35710 (U133A).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 as indicated. Differences

in levels among the different tissue types were analyzed using

Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc test. NS, not

significant; WDLPS, well-differentiated liposarcoma; DDLPS,

dedifferentiated liposarcoma; MDM2, mouse double minute 2 homolog;

GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7

member 11; SLC3A2, solute carrier family 3 member 2; HMGCR,

3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase; DPP4, dipeptidyl

peptidase-4. |

DDLPS cell lines show variable

sensitivity to ferroptosis-inducing agents

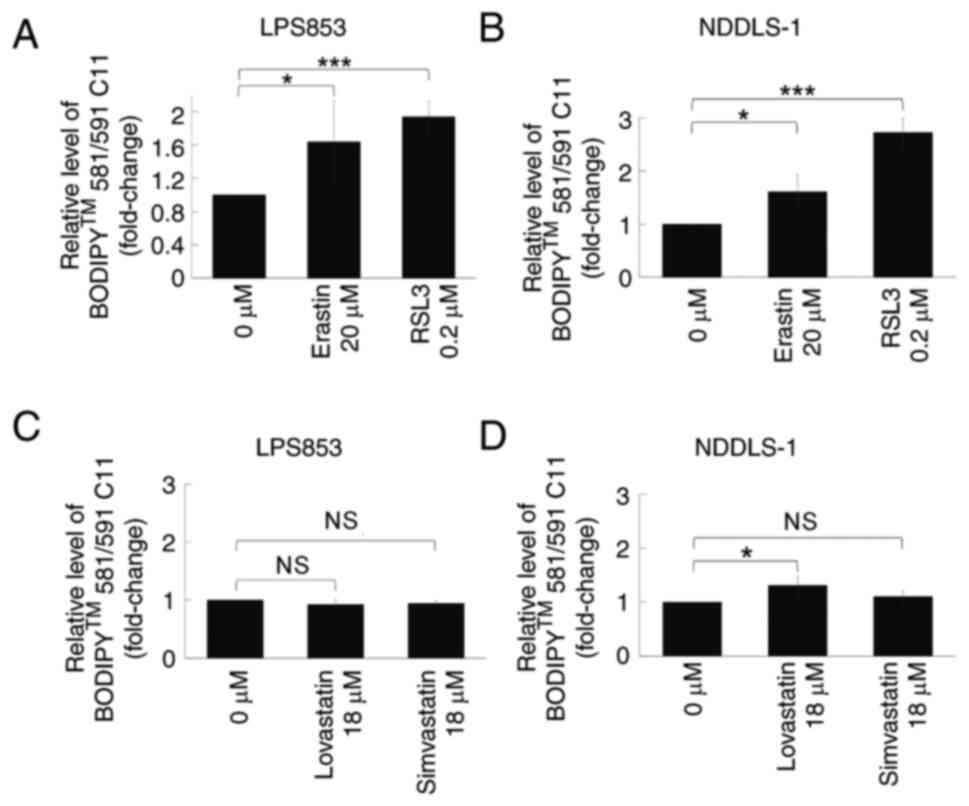

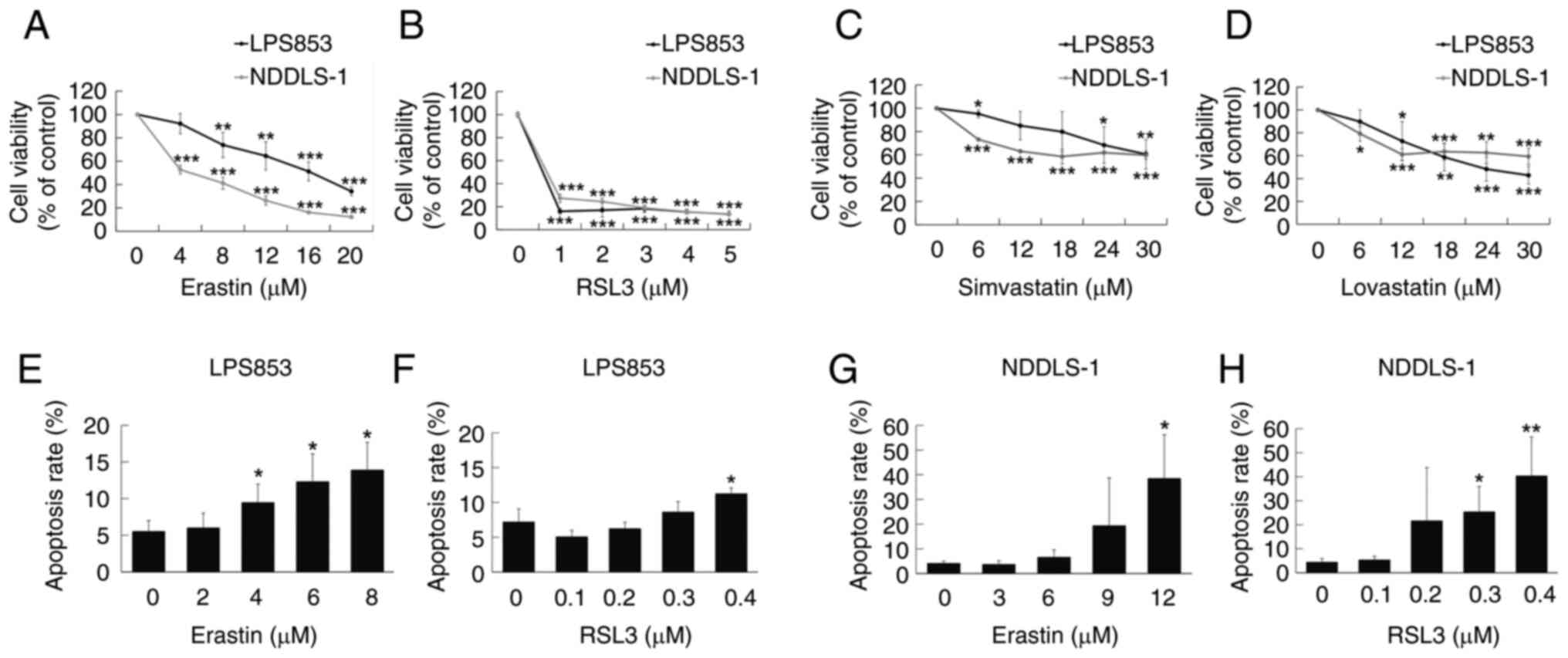

The potential lipid peroxidation effects of

ferroptosis-inducing agents on two DDLPS cell lines were evaluated.

Both erastin and RSL3 treatment significantly increased lipid

peroxidation levels in both cell lines compared with those in

untreated cells, as demonstrated by flow cytometry (Figs. 2 and S1). However, regarding the two statins

with HMGCR inhibitory activity, only lovastatin exhibited a

significant effect, inducing an increase in lipid peroxidation

levels in NDDLS-1 cells only. The cytotoxic effects of these four

agents were then assessed in the two cell lines. Erastin and RSL3

exerted significant cytotoxic effects on both DDLPS cell lines at

relatively low doses (Fig. 3A and

B). Lovastatin and simvastatin also showed significant,

although less potent, efficacy against the two DDLPS cell lines

(Fig. 3C and D). In addition,

erastin (Figs. 3E and G, S2A and C) and RSL3 (Figs. 3F and H, S2B and D) induced apoptosis in both DDLPS

cell lines. On the basis of these results, only erastin and RSL3

were used in subsequent experiments.

Erastin and RSL3 exert cytotoxic

effects primarily through ferroptosis

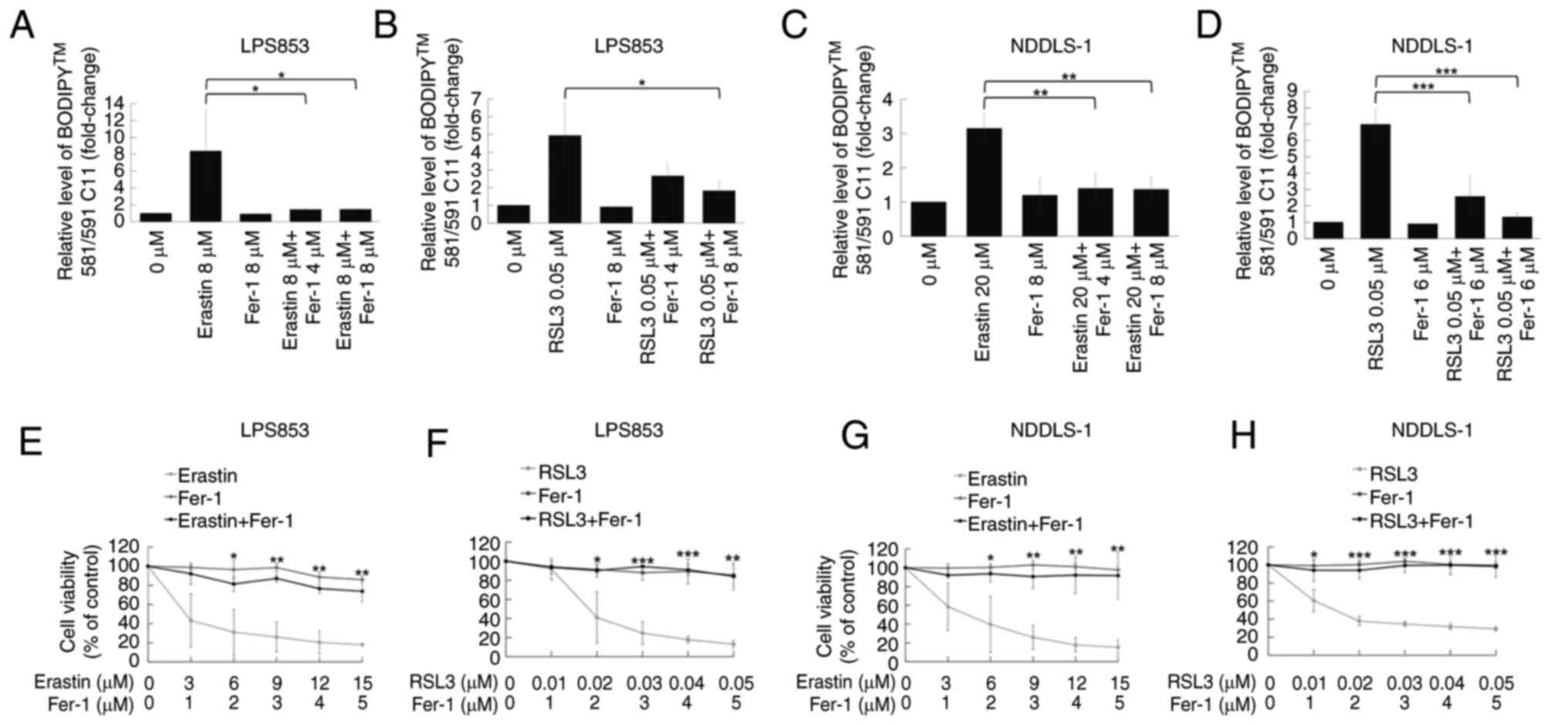

Further analysis was performed to determine whether

ferroptosis is the primary mechanism underlying the cytotoxic

effects of erastin and RSL3. The ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1

partially diminished the lipid peroxidation induced by erastin or

RSL3 in the LPS853 and NDDLS-1 cell lines (Figs. 4A-D and S3). Furthermore, CCK-8 assay results

revealed that Fer-1 attenuated the cytotoxic effects of both

erastin and RSL3 in both DDLPS cell lines (Fig. 4E-H). These results indicate that

both erastin and RSL3 exert their cytotoxic effects at least in

part via the induction of ferroptosis.

Treatment sequence is crucial for the

synergy of nutlin-3 with erastin but not RSL3 in ferroptosis

induction and cytotoxicity

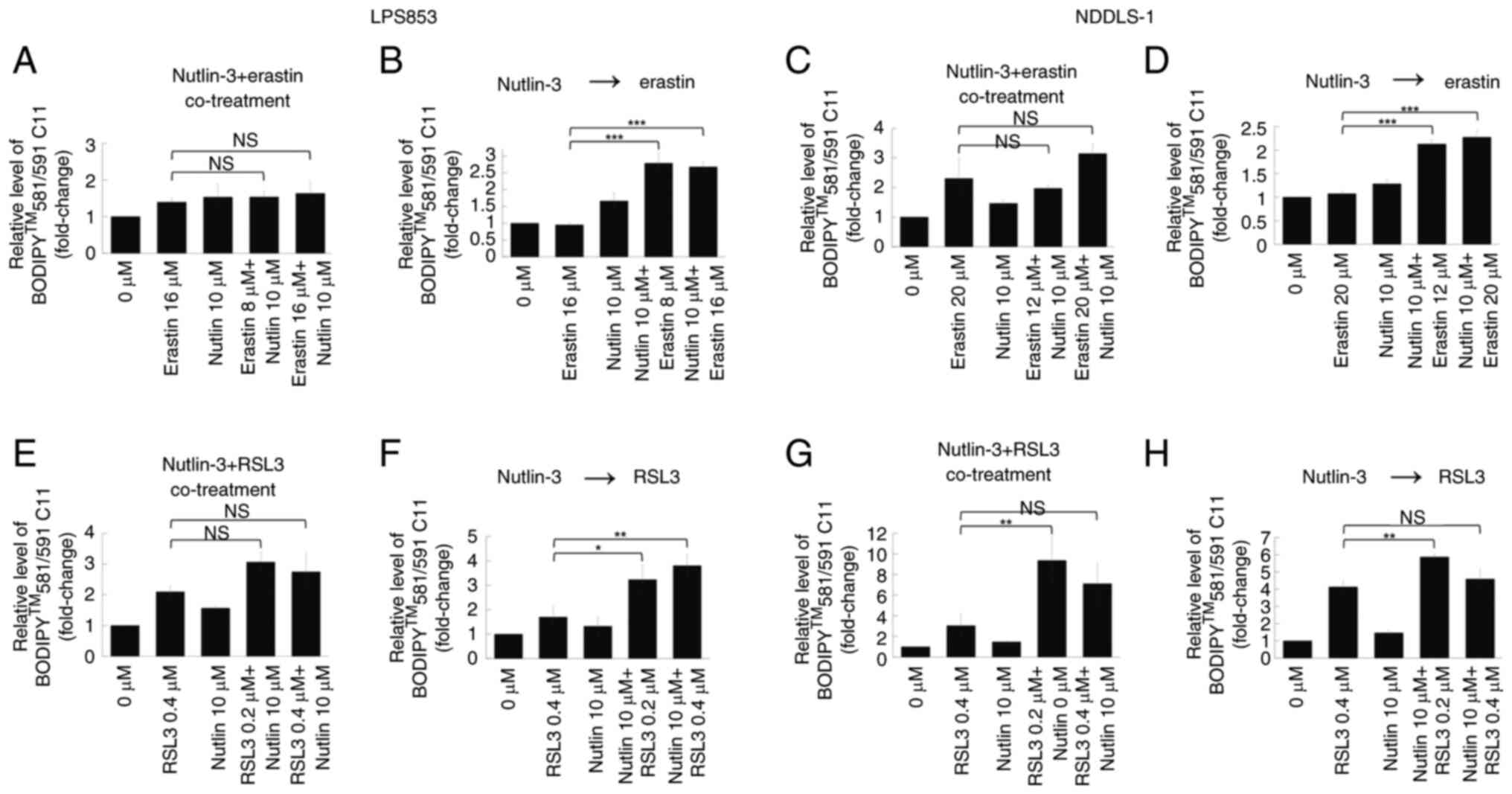

The potential synergistic effects of combining

nutlin-3 with erastin or RSL3 were evaluated. First, their effects

on lipid peroxidation were tested. Co-treatment with nutlin-3 and

erastin (Figs. 5A and C, S4A and C) did not significantly alter the

extent of lipid peroxidation compared with that induced by erastin

alone in either DDLPS cell line. However, pre-treatment with

nutlin-3 for 24 h significantly increased the lipid

peroxidation-inducing effects of erastin in both DDLPS cell lines

(Figs. 5B and D, S4B and D). By contrast, whether nutlin-3

and RSL3 were co-administered or applied sequentially did not

clearly impact the lipid peroxidation-inducing effects in either

DDLPS cell line (Figs. 5E-H and

S4E-H).

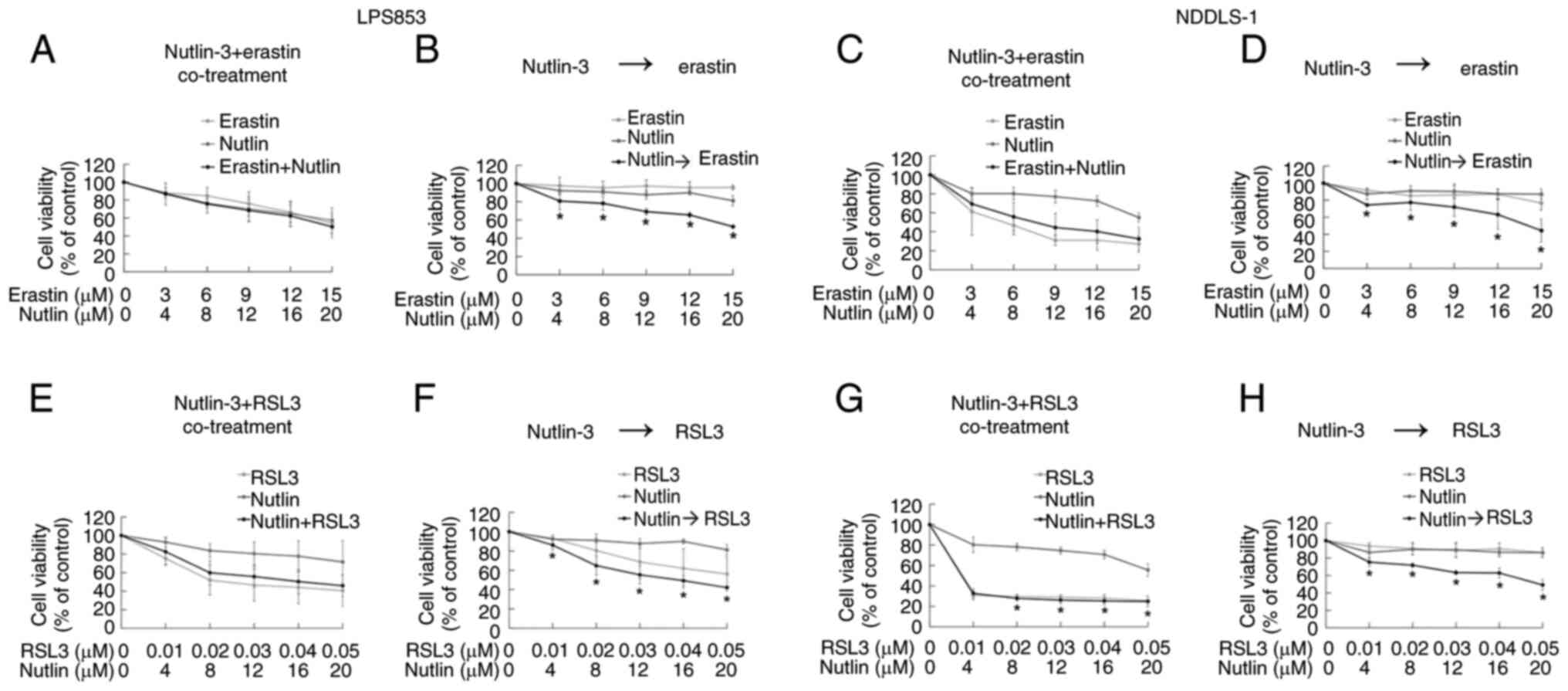

The synergistic cytotoxic effects of nutlin-3

combined with erastin or RSL3 were evaluated using the CCK-8 assay.

Co-treatment with nutlin-3 and erastin did not exhibit a

significant synergy in cytotoxicity (Fig. 6A and C). However, a 24-h

pre-treatment with nutlin-3 followed by treatment with erastin

synergistically induced cytotoxicity in both DDLPS cell lines

(Fig. 6B and D). For nutlin-3

combined with RSL3, the treatment sequence affected the synergy of

the cytotoxicity in LPS853 cells (Fig.

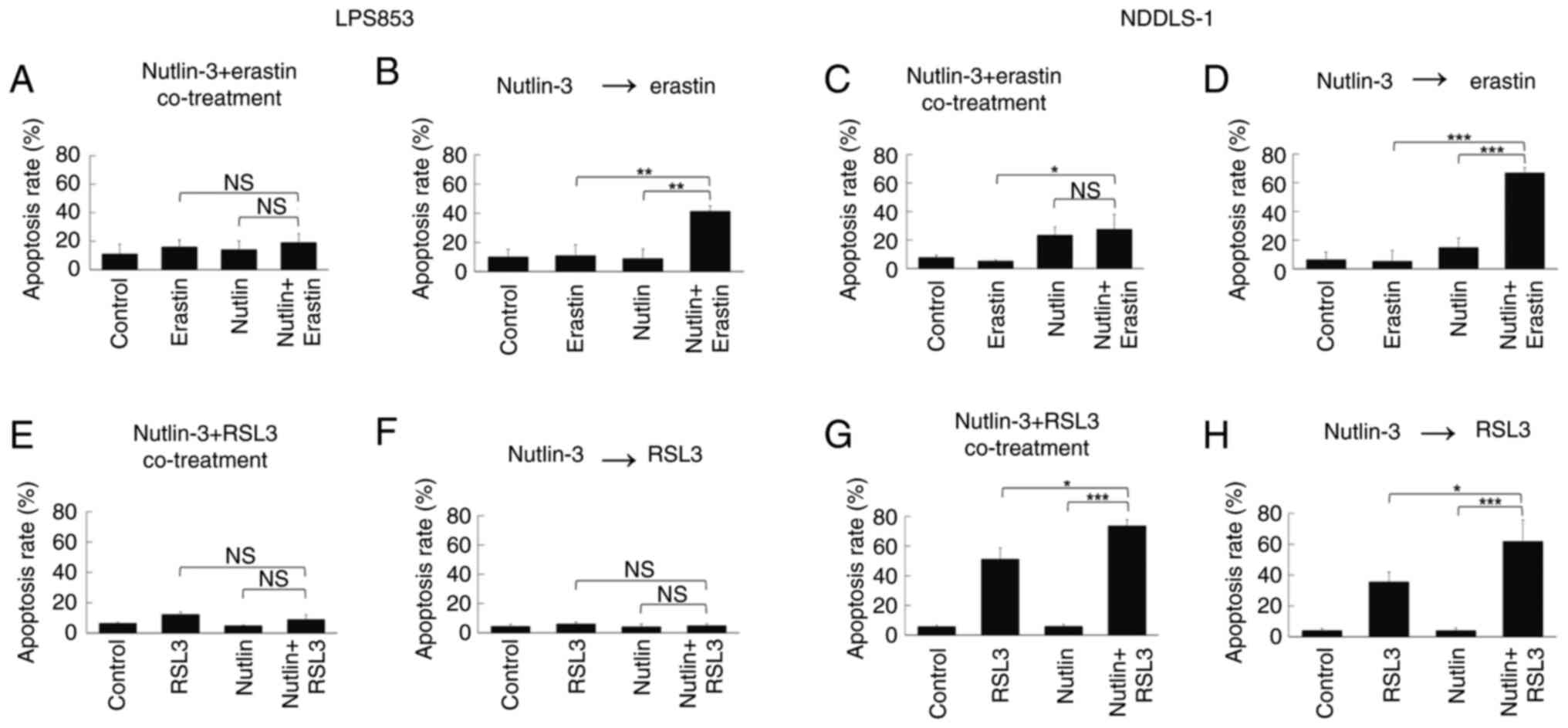

6E and F) but not in NDDSL-1 cells (Fig. 6G and H). Similarly, in the apoptosis

assay, the apoptosis-inducing effects of nutlin-3 and erastin

varied according to the treatment sequence (Figs. 7A-D, S5A and B, S6A and B), whereas those of nutlin-3 and

RSL3 did not (Figs. 7E-H, S5C and D, S6C and D). These findings indicate that

nutlin-3 pre-treatment significantly enhances the

ferroptosis-inducing and cytotoxic effects of erastin but not those

of RSL3.

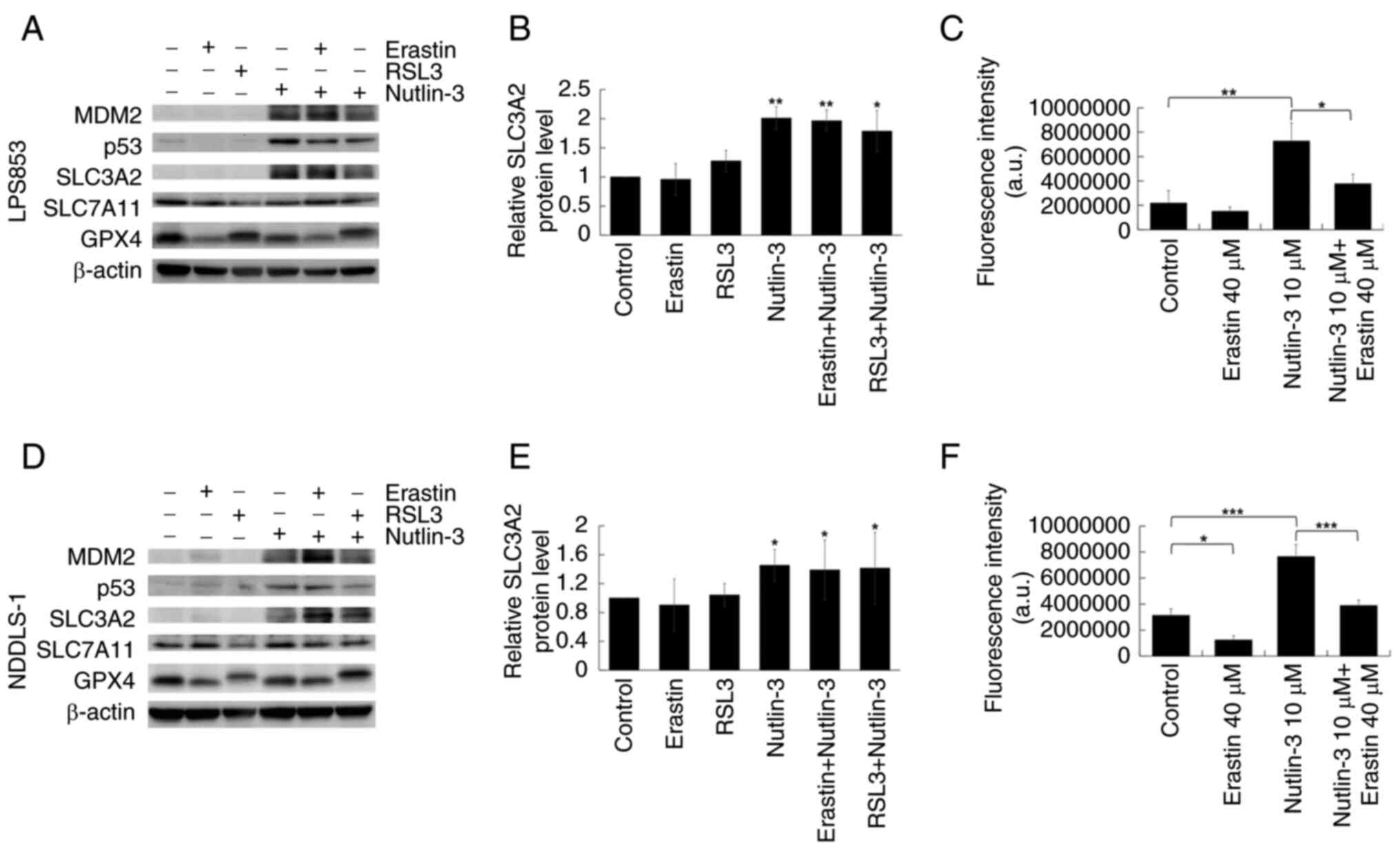

Nutlin-3-induced upregulation of

SLC3A2 and cystine uptake in DDLPS cell lines is suppressed by

erastin

As shown in Fig. 8A and

D, nutlin-3 treatment increased the expression of MDM2 and

TP53. This is consistent with previous studies which have shown

that nutlin-3 disrupts the interaction between MDM2 and TP53,

prevents their ubiquitination and leads to increased expression of

both proteins (38–40). Nutlin-3 treatment also increased the

expression of SLC3A2 (Fig. 8B and

E), while its effects on SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression were

inconsistent between the two cell lines. In the cystine uptake

assay, nutlin-3 treatment significantly increased the uptake of a

selenocystine fluorescent probe, and this effect was significantly

suppressed by erastin (Fig. 8C and

F). This suggests that nutlin-3 treatment increased the

expression of SLC3A2 in DDLPS, leading to enhanced cystine uptake

and greater sensitivity to erastin. This may explain why nutlin-3

pre-treatment synergistically promoted the cytotoxic effects of

erastin but not those of RSL3.

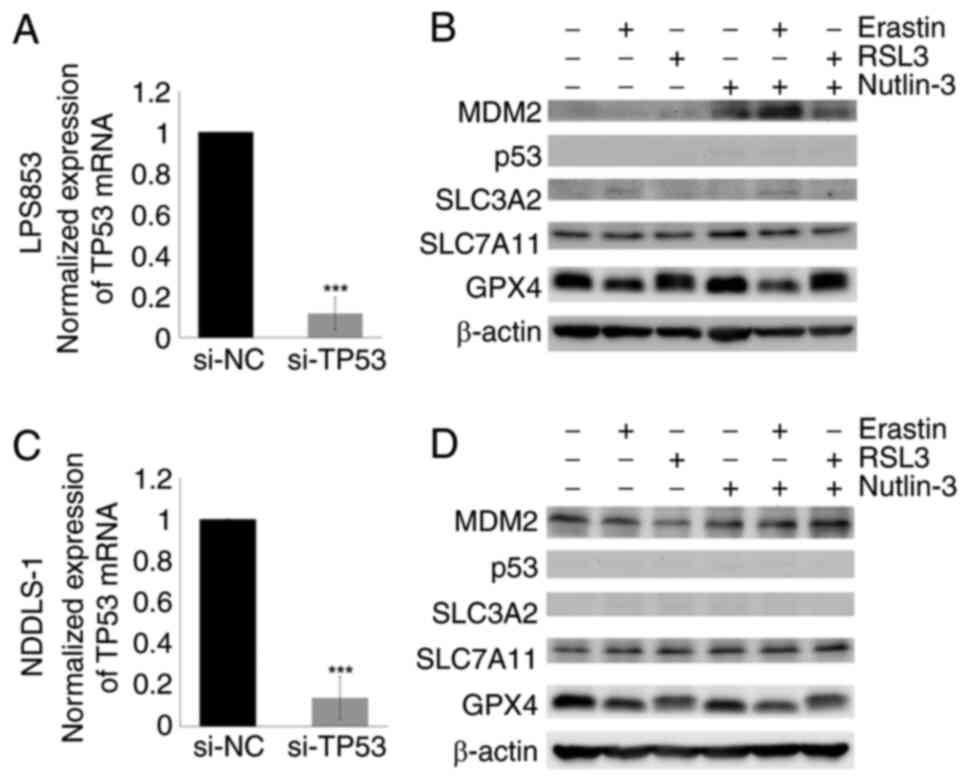

Nutlin-3-induced SLC3A2 upregulation

is abolished by TP53 KD

The mechanism by which nutlin-3 induces SLC3A2

upregulation was investigated. Given the role of TP53 in the

regulation of SLC3A2 expression, TP53 KD experiments were

performed. As shown in Fig. 9, the

nutlin-3-induced SLC3A2 upregulation previously observed in the

untransfected DDLPS cell lines was abolished by TP53 KD. This

result highlights the critical role of TP53 in nutlin-3-induced

SLC3A2 upregulation.

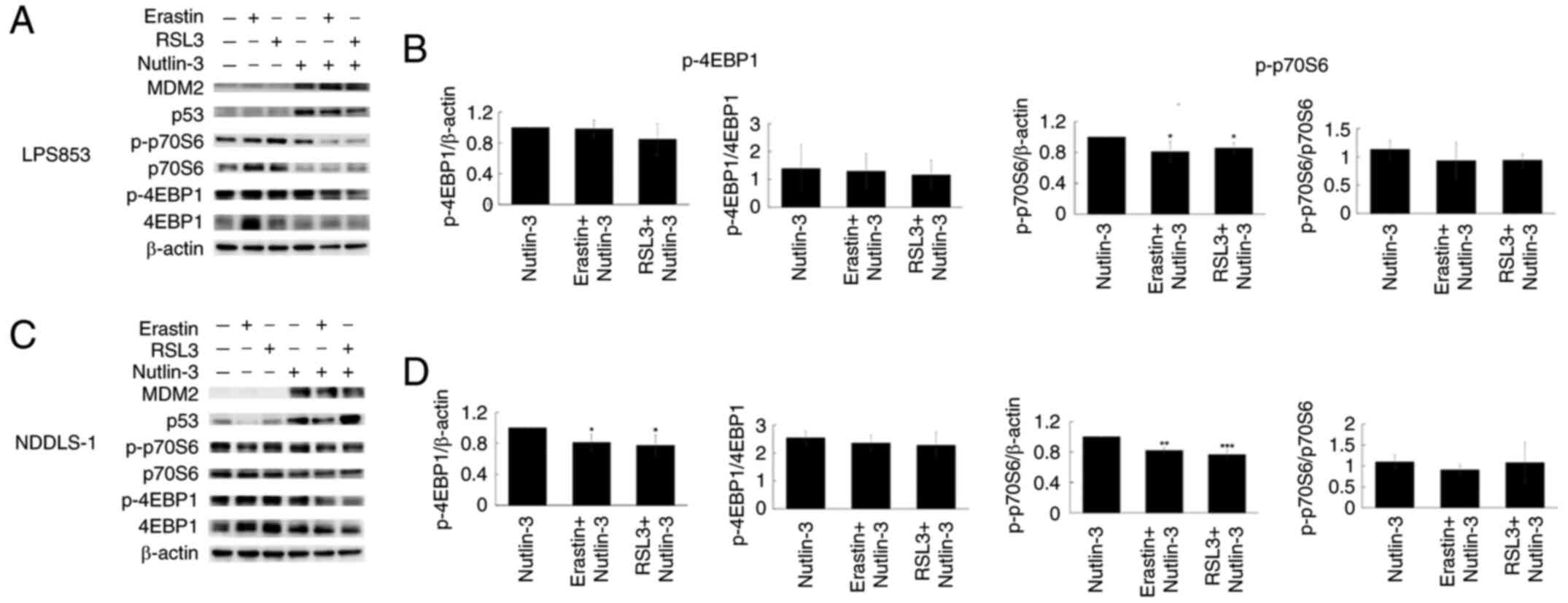

Combination of nutlin-3 with erastin

or RSL3 suppresses the mTOR pathway

Notably, the present study found that the

combination of nutlin-3 with either erastin or RSL3 can increase

apoptosis. The mTOR pathway has been reported to play a role in the

regulation of ferroptosis (41–43).

In addition, inhibition of mTOR pathway is known to induce

apoptosis (44–46). Therefore, the involvement of this

pathway was assessed via the evaluation of the mTOR downstream

effectors eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding

protein 1 (4EBP1) and p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6) in

DDLPS cells using western blotting. As shown in Fig. 10, the combination of nutlin-3 with

erastin or RSL3 suppressed the absolute p-4EBP1 levels in NDDLS-1

cells and p-p70S6 levels in both cell lines. However, these

treatment combinations had no significant effect on the

p-4EBP1/4EBP1 and p-p70S6/p70S6 ratios. This suppression of the

mTOR pathway may contribute to the apoptosis-inducing effects

observed with these combinations, but more studies are needed for

clarity.

Discussion

In the present study, bioinformatics analysis

identified that several ferroptosis-related genes are

differentially expressed in DDLPS. Additionally, in vitro

experiments demonstrated that two DDLPS cell lines were sensitive

to ferroptosis-inducing agents, particularly erastin and RSL3.

Furthermore, treatment of the cells with nutlin-3, an MDM2

inhibitor, followed by erastin, resulted in increased

ferroptosis-inducing and cytotoxic effects. Nutlin-3 also

upregulated the expression of SLC3A2 in the DDLPS cell lines, which

increased cystine uptake, and erastin attenuated these effects.

TP53 KD diminished the effect of nutlin-3 on SLC3A2, indicating

that TP53 contributes to SLC3A2 upregulation. Combining nutlin-3

with either of these ferroptosis-inducing agents reduced the

absolute p-4EBP1 levels in NDDLS-1 cells and p-p70S6 levels in both

cell lines, without significantly affecting the p-4EBP1/4EBP1 and

p-p70S6/p70S6 ratios. This suggests a potential role of the mTOR

pathway in the pro-apoptotic effect of these combinations, which

warrants further investigation.

MDM2 and CDK4 are oncogenes located in the 12q13-15

amplified chromosomal regions in both WDLPS and DDLPS (47). CDK4 phosphorylates Rb, promoting

cell cycle progression (48), while

MDM2 suppresses the function of TP53 by downregulating its

expression, exporting it from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and

cooperating with MDM4 to induce TP53 polyubiquitination and

subsequent degradation (20–24).

CDK4/6 inhibitors have shown efficacy in hormone receptor-positive

breast cancer (49–51), and several MDM2 inhibitors have been

developed, with some advancing to clinical trials (52–58).

However, CDK4/6 inhibitors (59,60)

and MDM2 inhibitors (52–58) have demonstrated only limited

activity in WDLPS/DDLPS.

Ferroptosis, a form of necrotic cell death

characterized by the oxidative modification of phospholipid

membranes through an iron-dependent mechanism (9), has been identified as a potential

mechanism of action for various anticancer treatments across

multiple cancers (61–65), including sarcomas (66). MDM2, a key oncogene in DDLPS

(19), negatively regulates TP53

(20), which itself is a critical

regulator of ferroptosis (16–18).

Therefore, the investigation of ferroptosis regulation in DDLPS may

lead to the identification of new therapeutic strategies for this

deadly disease.

GPX4, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 are three key regulators of

ferroptosis resistance. GPX4 dependency has been identified as a

unique characteristic of therapy-resistant cancer (67). In the present study, the

bioinformatics analysis of publicly available revealed that the

expression level of GPX4 in DDLPS is significantly lower compared

with that in adipose tissue and WDLPS. In vitro experiments

revealed that DDLPS cells are highly sensitive to RSL3 and erastin,

indicating a susceptibility to ferroptosis. Conversely, SLC7A11 and

SLC3A2, two components of xCT, were found to be more highly

expressed in LPS than in benign tissue. The upregulation of SLC7A11

may be partially due to the downregulation of TP53 by MDM2 in WDLPS

and DDLPS. The mechanism by which TP53 mediates SLC3A2 expression

is complex; previous studies have shown that SLC3A2 is upregulated

by mutant, but not wild-type, TP53 (68,69).

Therefore, further exploration of the regulatory mechanisms of

ferroptosis in DDLPS is warranted.

Given that MDM2 is a well-known oncogene in DDLPS,

the potential synergistic effect of nutlin-3, a MDM2 inhibitor,

with erastin and RSL3 was explored. The treatment sequence was

identified as a critical determinant of the efficacy of erastin.

Co-treatment with nutlin-3 did not markedly affect the

lipid-peroxidation-inducing and cytotoxic effects of erastin.

However, treatment with nutlin-3 for 24 h prior to treatment with

erastin significantly augmented the induction of lipid-peroxidation

and cytotoxicity of erastin in both DDLPS cell lines. This effect

of nutlin-3 was not observed with RSL3. These findings suggest that

nutlin-3 may sensitize DDLPS cell lines to erastin, potentially by

modulating the expression of ferroptosis-related genes underlying

its effects.

Immunoblotting revealed that nutlin-3 upregulated

SLC3A2 expression in both DDLPS cell lines. Subsequently, nutlin-3

was shown to increase cystine uptake in an erastin-suppressible

manner, which may be attributed to SLC3A2 upregulation.

Additionally, the nutlin-3-induced expression of SLC3A2 was

abolished by TP53 KD. These findings suggest that nutlin-3

treatment induces TP53-mediated SLC3A2 upregulation, leading to

increased cystine uptake and erastin sensitivity in DDLPS.

Notably, SLC7A11 expression levels remained largely

unchanged after nutlin-3 treatment. TP53, a key suppressor of

SLC7A11, is expected to decrease the levels of SLC7A11 when TP53

function is restored (16), as

nutlin-3 dissociates MDM2 from TP53, thereby preventing the

degradation of TP53 by ubiquitination (38–40).

However, as MDM2 is also released and is known to upregulate

SLC7A11 (70,71), the enhancing effect of MDM2 on

SLC7A11 expression may be counterbalanced by the suppressive effect

of restored TP53.

The present study found that treatment with nutlin-3

prior to treatment with erastin or RSL3 increased lipid

peroxidation, a hallmark of ferroptosis, and apoptosis. Nutlin-3

alone is known to induce apoptosis via cell cycle arrest or the

restoration of TP53 function (72–74).

mTOR is crucial in different types of programmed cell death

(75), including apoptosis

(44–46) and ferroptosis (41–43).

In the present study, combining nutlin-3 with either erastin or

RSL3 reduced the absolute levels of phosphorylated proteins in the

mTOR pathway but not the phosphorylated/total protein ratios,

suggesting the potential role of the mTOR pathway in the apoptosis

induction of these combinations. Further investigations are needed

to confirm this finding.

The present bioinformatics analysis revealed that

HMGCR expression is upregulated in LPS. However, lovastatin and

simvastatin, two inhibitors of HMGCR, showed minimal effects on

lipid peroxidation and only modest cytotoxicity against the two

DDLPS cell lines, suggesting that the HMGCR pathway may not play a

major role in the regulation of ferroptosis in DDLPS. DPP4

expression was also found to be upregulated in LPS, likely due to

TP53 downregulation in WDLPS and DDLPS (18). DPP4 is an exoprotease that is

expressed by different cell types and plays a role in plasma

membrane-associated lipid peroxidation (18). However, previous studies have shown

that its role in cancer is primarily restricted to the tumor

microenvironment (76). Therefore,

these two genes were not pursued further in the present study.

In summary, the present study showed that several

ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in DDLPS.

Additionally, in vitro experiments demonstrated that DDLPS

cell lines are highly sensitive to the lipid peroxidation-inducing

and cytotoxic effects of erastin and RSL3. Furthermore,

pre-treatment with nutlin-3 significantly increased the efficacy of

erastin in DDLPS cell lines, potentially via the TP53-mediated

upregulation of SLC3A2, resulting in increased cystine uptake and

vulnerability to ferroptosis. Suppression of the mTOR pathway may

contribute to the apoptosis-inducing effects observed with the

nutlin-3-containing combinations. This mechanism may contribute to

resistance to MDM2 inhibitors in DDLPS. These findings provide

valuable insights into the potential development of novel

treatments for DDLPS. In future studies, it is planned to examine

the combined effect of MDM2 inhibitors and ferroptosis-inducing

agents in greater detail, and to explore the underlying mechanisms

in an in vivo model.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was jointly supported by grants from the National

Science and Technology Council (grant nos. MOST 110-2314-B-075-070

and MOST 111-2314-B-075-022), and Taipei Veterans General Hospital

(grant nos. V110D56-002-MY2-1, V110D56-002-MY2-2, V110C-208,

V112C-093 and V113C-116). This study was also supported by the

Taiwan Clinical Oncology Research Foundation, Melissa Lee Cancer

Foundation (grant no. MLCF_V114_A11403), and the Chong Hin Loon

Memorial Cancer and Biotherapy Research Center of National Yang

Ming Chiao Tung University.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CCY, PCHC, TCC and JAF were responsible for the

design and conception of the study. MHY, CHY and YCL were

responsible for data acquisition. SCC, WCW, PKW, CMC and JYW were

responsible for data interpretation. CCY was responsible for

writing the original draft of the manuscript. PCHC and JAF reviewed

and edited the manuscript. CHY and YCL edited the figures. TCC and

MHY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was deemed as being exempt from ethical

review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taipei Veterans

General Hospital (IRB no. 2021-07-003AE).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence (AI) tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary,

taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of the

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Hung GY, Yen CC, Horng JL, Liu CY, Chen

WM, Chen TH and Liu CL: Incidences of primary soft tissue sarcoma

diagnosed on extremities and trunk wall: A population-based study

in taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 94:e16962015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hung GY, Horng JL, Chen PC, Lin LY, Chen

JY, Chuang PH, Chao TC and Yen CC: Incidence of soft tissue sarcoma

in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based study (2007–2013). Cancer

Epidemiol. 60:185–192. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ducimetiere F, Lurkin A, Ranchere-Vince D,

Decouvelaere AV, Peoc'h M, Istier L, Chalabreysse P, Muller C,

Alberti L, Bringuier PP, et al: Incidence of sarcoma histotypes and

molecular subtypes in a prospective epidemiological study with

central pathology review and molecular testing. PLoS One.

6:e202942011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH and Jones RL:

Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol.

36:151–159. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Seddon B, Strauss SJ, Whelan J, Leahy M,

Woll PJ, Cowie F, Rothermundt C, Wood Z, Benson C, Ali N, et al:

Gemcitabine and docetaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line

treatment in previously untreated advanced unresectable or

metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas (GeDDiS): A randomised controlled

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:1397–1410. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Schoffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG, Italiano

A, Gelderblom H, Choy E, Grignani G, Camargo V, Bauer S, Rha SY, et

al: Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with

advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: A randomised, open-label,

multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 387:1629–1637. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Demetri GD, Schoffski P, Grignani G, Blay

JY, Maki RG, Van Tine BA, Alcindor T, Jones RL, D'Adamo DR, Guo M

and Chawla S: Activity of eribulin in patients with advanced

liposarcoma demonstrated in a subgroup analysis from a randomized

phase III study of eribulin versus dacarbazine. J Clin Oncol.

35:3433–3439. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL,

Hensley ML, Schuetze SM, Staddon A, Milhem M, Elias A, Ganjoo K,

Tawbi H, et al: Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine

for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of

conventional chemotherapy: Results of a phase III randomized

multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 34:786–793. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Conrad M, Angeli JP, Vandenabeele P and

Stockwell BR: Regulated necrosis: Disease relevance and therapeutic

opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 15:348–366. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun

X, Kang R and Tang D: Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death

Differ. 23:369–379. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascon S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ingold I, Berndt C, Schmitt S, Doll S,

Poschmann G, Buday K, Roveri A, Peng X, Porto Freitas F, Seibt T,

et al: Selenium utilization by GPX4 is required to prevent

hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell. 172:409–422. e4212018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cheok CF, Verma CS, Baselga J and Lane DP:

Translating p53 into the clinic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 8:25–37. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T,

Hibshoosh H, Baer R and Gu W: Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated

activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 520:57–62. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Moon SH, Huang CH, Houlihan SL, Regunath

K, Freed-Pastor WA, Morris JP, Tschaharganeh DF, Kastenhuber ER,

Barsotti AM, Culp-Hill R, et al: p53 represses the mevalonate

pathway to mediate tumor suppression. Cell. 176:564–580. e5192019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xie Y, Zhu S, Song X, Sun X, Fan Y, Liu J,

Zhong M, Yuan H, Zhang L, Billiar TR, et al: The tumor suppressor

p53 limits ferroptosis by blocking DPP4 activity. Cell Rep.

20:1692–1704. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dei Tos AP, Doglioni C, Piccinin S, Sciot

R, Furlanetto A, Boiocchi M, Dal CP, Maestro R, Fletcher CD and

Tallini G: Coordinated expression and amplification of the MDM2,

CDK4, and HMGI-C genes in atypical lipomatous tumours. J Pathol.

190:531–536. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Karni-Schmidt O, Lokshin M and Prives C:

The roles of MDM2 and MDMX in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 11:617–644.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Leslie PL and Zhang Y: MDM2 oligomers:

Antagonizers of the guardian of the genome. Oncogene. 35:6157–6165.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hock AK and Vousden KH: The role of

ubiquitin modification in the regulation of p53. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1843:137–149. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

do Patrocinio AB, Rodrigues V and Guidi

Magalhaes L: P53: Stability from the ubiquitin-proteasome system

and specific 26S proteasome inhibitors. ACS Omega. 7:3836–3843.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bang S, Kaur S and Kurokawa M: Regulation

of the p53 family proteins by the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:2612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Venkatesh D, O'Brien NA, Zandkarimi F,

Tong DR, Stokes ME, Dunn DE, Kengmana ES, Aron AT, Klein AM, Csuka

JM, et al: MDM2 and MDMX promote ferroptosis by PPARalpha-mediated

lipid remodeling. Genes Dev. 34:526–543. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yen CC, Chen LT, Li CF, Chen SC, Chua WY,

Lin YC, Yen CH, Chen YC, Yang MH, Chao Y and Fletcher JA:

Identification of phenothiazine as an ETV1targeting agent in

gastrointestinal stromal tumors using the connectivity map. Int J

Oncol. 55:536–546. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chibon F, Lagarde P, Salas S, Perot G,

Brouste V, Tirode F, Lucchesi C, de Reynies A, Kauffmann A, Bui B,

et al: Validated prediction of clinical outcome in sarcomas and

multiple types of cancer on the basis of a gene expression

signature related to genome complexity. Nat Med. 16:781–787. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gobble RM, Qin LX, Brill ER, Angeles CV,

Ugras S, O'Connor RB, Moraco NH, Decarolis PL, Antonescu C and

Singer S: Expression profiling of liposarcoma yields a multigene

predictor of patient outcome and identifies genes that contribute

to liposarcomagenesis. Cancer Res. 71:2697–2705. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Doyle KR, Mitchell MA, Roberts CL, James

S, Johnson JE, Zhou Y, von Mehren M, Lev D, Kipling D and Broccoli

D: Validating a gene expression signature proposed to differentiate

liposarcomas that use different telomere maintenance mechanisms.

Oncogene. 31:265–266; author reply 267–268. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yoshino J, Conte C, Fontana L,

Mittendorfer B, Imai S, Schechtman KB, Gu C, Kunz I, Rossi Fanelli

F, Patterson BW and Klein S: Resveratrol supplementation does not

improve metabolic function in nonobese women with normal glucose

tolerance. Cell Metab. 16:658–664. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nookaew I, Svensson PA, Jacobson P, Jernas

M, Taube M, Larsson I, Andersson-Assarsson JC, Sjostrom L, Froguel

P, Walley A, et al: Adipose tissue resting energy expenditure and

expression of genes involved in mitochondrial function are higher

in women than in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98:E370–E378. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li C and Wong WH: Model-based analysis of

oligonucleotide arrays: Model validation, design issues and

standard error application. Genome Biol. 2:RESEARCH00322001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li C and Wong WH: Model-based analysis of

oligonucleotide arrays: Expression index computation and outlier

detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:31–36. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yoshida Y, Shimakawa S, Itoh N and Niki E:

Action of DCFH and BODIPY as a probe for radical oxidation in

hydrophilic and lipophilic domain. Free Radic Res. 37:861–872.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chou TC and Talalay P: Quantitative

analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of

multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 22:27–55.

1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chou YS, Yen CC, Chen WM, Lin YC, Wen YS,

Ke WT, Wang JY, Liu CY, Yang MH, Chen TH and Liu CL: Cytotoxic

mechanism of PLK1 inhibitor GSK461364 against osteosarcoma: Mitotic

arrest, apoptosis, cellular senescence, and synergistic effect with

paclitaxel. Int J Oncol. 48:1187–1194. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D,

Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, Kong N, Kammlott U, Lukacs C, Klein C, et

al: In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule

antagonists of MDM2. Science. 303:844–848. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tovar C, Rosinski J, Filipovic Z, Higgins

B, Kolinsky K, Hilton H, Zhao X, Vu BT, Qing W, Packman K, et al:

Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in

cancer: Implications for therapy. Proc NatI Acad Sci USA.

103:1888–1893. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Henze J, Muhlenberg T, Simon S, Grabellus

F, Rubin B, Taeger G, Schuler M, Treckmann J, Debiec-Rychter M,

Taguchi T, et al: p53 modulation as a therapeutic strategy in

gastrointestinal stromal tumors. PLoS One. 7:e377762012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shi Z, Naowarojna N, Pan Z and Zou Y:

Multifaceted mechanisms mediating cystine starvation-induced

ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 12:47922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang Z, Zong H, Liu W, Lin W, Sun A, Ding

Z, Chen X, Wan X, Liu Y, Hu Z, et al: Augmented ERO1alpha upon

mTORC1 activation induces ferroptosis resistance and tumor

progression via upregulation of SLC7A11. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

43:1122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yin J, Chen J, Hong JH, Huang Y, Xiao R,

Liu S, Deng P, Sun Y, Chai KXY, Zeng X, et al: 4EBP1-mediated

SLC7A11 protein synthesis restrains ferroptosis triggered by MEK

inhibitors in advanced ovarian cancer. JCI Insight. 9:e1778572024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Han J, Wang L, Lv H, Liu J, Dong Y, Shi L

and Ji Q: EphA2 inhibits SRA01/04 cells apoptosis by suppressing

autophagy via activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 711:1090242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang J, Pi C and Wang G: Inhibition of

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by apigenin induces apoptosis and autophagy

in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomed Pharmacother.

103:699–707. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li W, Li D, Ma Q, Chen Y, Hu Z, Bai Y and

Xie L: Targeted inhibition of mTOR by BML-275 induces

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in prostate cancer.

Eur J Pharmacol. 957:1760352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Fletcher CD: The evolving classification

of soft tissue tumours-An update based on the new 2013 WHO

classification. Histopathology. 64:2–11. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sherr CJ, Beach D and Shapiro GI:

Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From discovery to therapy. Cancer Discov.

6:353–367. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, Jones S, Im

SA, Gelmon K, Harbeck N, Lipatov ON, Walshe JM, Moulder S, et al:

Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med.

375:1925–1936. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, Yap

YS, Sonke GS, Paluch-Shimon S, Campone M, Petrakova K, Blackwell

KL, Winer EP, et al: Updated results from MONALEESA-2, a phase III

trial of first-line ribociclib plus letrozole versus placebo plus

letrozole in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced

breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 29:1541–1547. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, Sohn J,

Paluch-Shimon S, Huober J, Park IH, Tredan O, Chen SC, Manso L, et

al: MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast

cancer. J Clin Oncol. 35:3638–3646. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang S, Zhao Y, Aguilar A, Bernard D and

Yang CY: Targeting the MDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction for new

cancer therapy: Progress and challenges. Cold Spring Harb Perspect

Med. 7:a0262452017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kocik J, Machula M, Wisniewska A, Surmiak

E, Holak TA and Skalniak L: Helping the released guardian: Drug

combinations for supporting the anticancer activity of HDM2 (MDM2)

antagonists. Cancers (Basel). 11:10142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Fang Y, Liao G and Yu B: Small-molecule

MDM2/X inhibitors and PROTAC degraders for cancer therapy: Advances

and perspectives. Acta Pharm Sin B. 10:1253–1278. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhao Y, Aguilar A, Bernard D and Wang S:

Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 protein-protein

interaction (MDM2 Inhibitors) in clinical trials for cancer

treatment. J Med Chem. 58:1038–1052. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

LoRusso P, Yamamoto N, Patel MR, Laurie

SA, Bauer TM, Geng J, Davenport T, Teufel M, Li J, Lahmar M and

Gounder MM: The MDM2-p53 Antagonist brigimadlin (BI 907828) in

patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors: Results of a

phase Ia, first-in-human, dose-escalation study. Cancer Discov.

13:1802–1813. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ray-Coquard I, Blay JY, Italiano A, Le

Cesne A, Penel N, Zhi J, Heil F, Rueger R, Graves B, Ding M, et al:

Effect of the MDM2 antagonist RG7112 on the P53 pathway in patients

with MDM2-amplified, well-differentiated or dedifferentiated

liposarcoma: An exploratory proof-of-mechanism study. Lancet Oncol.

13:1133–1140. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Gounder MM, Bauer TM, Schwartz GK, Weise

AM, LoRusso P, Kumar P, Tao B, Hong Y, Patel P, Lu Y, et al: A

first-in-human Phase I study of milademetan, an MDM2 inhibitor, in

patients with advanced liposarcoma, solid tumors, or lymphomas. J

Clin Oncol. 41:1714–1724. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Assi T, Kattan J, Rassy E, Nassereddine H,

Farhat F, Honore C, Le Cesne A, Adam J and Mir O: Targeting CDK4

(cyclin-dependent kinase) amplification in liposarcoma: A

comprehensive review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 153:1030292020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Dickson MA, Schwartz GK, Keohan ML,

D'Angelo SP, Gounder MM, Chi P, Antonescu CR, Landa J, Qin LX,

Crago AM, et al: Progression-free survival among patients with

well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma treated with

CDK4 inhibitor palbociclib: A phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol.

2:937–940. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Guo J, Xu B, Han Q, Zhou H, Xia Y, Gong C,

Dai X, Li Z and Wu G: Ferroptosis: A novel anti-tumor action for

cisplatin. Cancer Res Treat. 50:445–460. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ma S, Henson ES, Chen Y and Gibson SB:

Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment

of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 7:e23072016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Trujillo-Alonso V, Pratt EC, Zong H,

Lara-Martinez A, Kaittanis C, Rabie MO, Longo V, Becker MW, Roboz

GJ, Grimm J and Guzman ML: FDA-approved ferumoxytol displays

anti-leukaemia efficacy against cells with low ferroportin levels.

Nat Nanotechnol. 14:616–622. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yamaguchi Y, Kasukabe T and Kumakura S:

Piperlongumine rapidly induces the death of human pancreatic cancer

cells mainly through the induction of ferroptosis. Int J Oncol.

52:1011–1022. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Brashears CB, Prudner BC, Rathore R,

Caldwell KE, Dehner CA, Buchanan JL, Lange SES, Poulin N, Sehn JK,

Roszik J, et al: Malic enzyme 1 absence in synovial sarcoma shifts

antioxidant system dependence and increases sensitivity to

ferroptosis induction with ACXT-3102. Clin Cancer Res.

28:3573–3589. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Dhruv HD, Gill S,

Eichhoff OM, Seashore-Ludlow B, Kaffenberger SD, Eaton JK, Shimada

K, Aguirre AJ, et al: Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of

cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature. 547:453–457.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Mello SS, Valente LJ, Raj N, Seoane JA,

Flowers BM, McClendon J, Bieging-Rolett KT, Lee J, Ivanochko D,

Kozak MM, et al: A p53 super-tumor suppressor reveals a tumor

suppressive p53-ptpn14-yap axis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell.

32:460–473. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Tombari C, Zannini A, Bertolio R, Pedretti

S, Audano M, Triboli L, Cancila V, Vacca D, Caputo M, Donzelli S,

et al: Mutant p53 sustains serine-glycine synthesis and essential

amino acids intake promoting breast cancer growth. Nat Commun.

14:67772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Fujihara KM, Corrales Benitez M, Cabalag

CS, Zhang BZ, Ko HS, Liu DS, Simpson KJ, Haupt Y, Lipton L, Haupt

S, et al: SLC7A11 Is a superior determinant of APR-246

(Eprenetapopt) response than TP53 mutation status. Mol Cancer Ther.

20:1858–1867. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Riscal R, Schrepfer E, Arena G, Cisse MY,

Bellvert F, Heuillet M, Rambow F, Bonneil E, Sabourdy F, Vincent C,

et al: Chromatin-bound MDM2 regulates serine metabolism and redox

homeostasis independently of p53. Mol Cell. 62:890–902. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Villalonga-Planells R, Coll-Mulet L,

Martinez-Soler F, Castano E, Acebes JJ, Gimenez-Bonafe P, Gil J and

Tortosa A: Activation of p53 by nutlin-3a induces apoptosis and

cellular senescence in human glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One.

6:e185882011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Miyachi M, Kakazu N, Yagyu S, Katsumi Y,

Tsubai-Shimizu S, Kikuchi K, Tsuchiya K, Iehara T and Hosoi H:

Restoration of p53 pathway by nutlin-3 induces cell cycle arrest

and apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res.

15:4077–4084. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Manfe V, Biskup E, Johansen P, Kamstrup

MR, Krejsgaard TF, Morling N, Wulf HC and Gniadecki R: MDM2

inhibitor nutlin-3a induces apoptosis and senescence in cutaneous

T-cell lymphoma: role of p53. J Invest Dermatol. 132:1487–1496.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xie Y, Lei X, Zhao G, Guo R and Cui N:

mTOR in programmed cell death and its therapeutic implications.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 71–72. 66–81. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Cordero OJ: CD26 and cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 14:51942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|