Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is an autosomal

dominant condition resulting from mutations in the NF2 gene located

on chromosome 22, and it is marked by the presence of multiple

neurological tumors (1). The main

manifestations of NF2 include the presence of bilateral vestibular

schwannomas (also known as bilateral acoustic neuromas),

meningiomas, spinal tumors and various neoplasms affecting both the

central and peripheral nervous systems. These may result in hearing

loss, balance issues, headaches, facial nerve paralysis, impaired

vision and various neurological symptoms (2,3).

The management of NF2 generally requires a

comprehensive strategy, which encompasses the surgical removal of

tumors, radiation treatment, medication-based therapies and

supportive rehabilitation services. The surgical resection method

is frequently employed to remove tumors that are accessible;

however, it entails certain risks, particularly when dealing with

tumors located in sensitive areas. Radiation therapy is effective

in managing tumor growth; however, it can also lead to negative

side effects. At present, there are limited effective treatments

for NF2 available. The effectiveness of pharmaceutical agents in

addressing NF2-associated tumors is constrained, thus surgical

intervention continues to be the primary approach for managing NF2

progression (4,5). For individuals with NF2 who are unable

or opt against surgical intervention, pharmacological treatments

play a vital role in disease management. Currently, there are no

specific medications that demonstrate high efficacy in the

treatment of tumors associated with NF2.

NF2 is linked to various intracellular signaling

pathways, including Hippo, protein kinase A, PI3K/AKT, Rac/p21

activated kinases/JNK, WNT/β-catenin, receptor tyrosine kinase,

Ras, MAPK, Yes-associated protein, p21-activated kinase, CD44 and

Rac/Rho (6,7). Inactivation of NF2 leads to the

activation of these cellular pathways, which are crucial in the

pathological development of NF2-associated tumors. Focusing on

these pathways may prove beneficial in the treatment of the tumors

(8). Protein tyrosine kinase

inhibitors have demonstrated the ability to decelerate tumor growth

and prolong progression-free survival in clinical trials (9,10). The

potential of these inhibitors as a treatment for NF2 tumors

warrants further investigation. Brigatinib represents an advanced

class of tyrosine kinase inhibitors that has received approval for

the treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase/ROS proto-oncogene 1

(ALK/ROS1)-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It

effectively inhibits ALK and ROS1 fusion proteins, obstructing

downstream pro-survival pathways including MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT.

This combined approach effectively diminishes tumor growth and

spread, particularly in individuals with central nervous system

involvement (11,12). In NF2, the absence of the Merlin

protein resulting from mutations in the NF2 gene causes the

hyperactivation of various tyrosine kinases, such as focal adhesion

kinase 1 (FAK1) and Ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2). The activity

of these kinases is a significant factor in the proliferation of

schwannomas and meningiomas. A preclinical study showed that

brigatinib inhibits FAK1 and EphA2 activity without relying on

ALK/ROS1, leading to a reduction in NF2-deficient tumors in mouse

models (13). This multi-targeted

approach highlights brigatinib as a compelling candidate for tumors

associated with NF2. Currently, there is a limited number of

clinical studies validating its short-term efficacy for NF2. The

present study assessed the immediate efficacy of brigatinib for

NF2, with the goal of introducing a novel therapeutic option for

the condition.

Patients and methods

Study design

Twelve patients with NF2 were retrospectively

identified from the hospital medical information database at The

First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing,

China), covering the period from June 2021 to April 2024. Inclusion

criteria included age ≥6 years, clinical diagnosis of NF2.

Exclusion criteria included medical conditions incompatible with

brigatinib, and tumors not amenable to volumetric MRI analysis. The

present study adhered to the STROBE guidelines (https://www.strobe-statement.org/). All 12

patients received medical consultation and treatment at the First

Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China).

Their surgical histories involved multiple medical centers,

including the First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital

(Beijing, China), Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University

(Beijing, China), Beijing Tiantan Hospital (Beijing, China) and

Huashan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University (Shanghai,

China).

The hypothesis of the present study posits that

brigatinib will lead to a substantial reduction in meningioma

volume and delay disease progression. The primary outcome measure

of this study was the change in meningioma after vs. before

treatment. Secondary outcomes included changes in patients'

hearing, emotional state, pain level and the occurrence of adverse

events.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were defined as patient age >6

years, a clinical diagnosis of NF2 between the ages of 14 and 16

years (14–16) and no prior treatment with tyrosine

kinase inhibitors. Individuals were excluded from the study if they

met any of the following criteria: Prior treatment with tyrosine

kinase inhibitors, surgical procedures necessitated by tumor

progression during the trial, medical conditions that are not

compatible with brigatinib treatment and tumors that are not

amenable to measurement via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Brigatinib was administered for the treatment of NSCLC at a dosage

of 180 mg once daily, following a 7-day lead-in period at 90 mg

once daily (17). To ensure safety

and tolerability in evaluating the potential effects of brigatinib

on NF2, a dose of 90 mg was chosen for the intervention.

Participants received a daily dosage of 90 mg of brigatinib,

provided by Takeda Pharma. Written informed consent was obtained

from the patient's parents or guardians to allow the patient to

receive the treatment.

Variables

The primary outcome was change in meningioma volume

and secondary outcomes included changes in the size of vestibular

schwannomas, as well as hearing, emotional state and pain, measured

before and after treatment. The change in the maximum diameter of

meningiomas on MRI was employed to assess disease progression,

following the RECIST criteria (18). Disease progression was defined as a

≥20% increase in the maximum meningioma diameter on MRI. Patients

without progression by the end of follow-up (censored data) were

those who either completed the 12-month follow-up without meeting

the progression criteria or were lost to follow-up. The time from

starting medication to disease progression was assessed and

patients were divided into two age groups (<18 and ≥18 years) to

compare progression times. Secondary endpoints included changes in

the volume of vestibular schwannomas, changes in hearing, emotional

state and pain. Adverse effects during the study were also observed

and recorded.

Data sources and data measurement

Brain MRIs were performed at baseline, as well as 6

and 12 months during treatment. For scans, sagittal and coronal

positions were used and scanning sequences Spin Echo (SE), Fast SE

(FSE) and Fast Recovery FSE for multi-angle T1-weighted imaging

(T1WI) and T2WI imaging were measured. The MRI scans included

post-contrast images of the internal auditory canal and the entire

brain. The physician selected the largest meningioma and vestibular

schwannoma to assess tumor volume. The measurements in the MRI

examination were carried out by two board-certified

neuroradiologists with >8 years of work experience and these two

neuroradiologists received training before the study was launched.

The tumor's maximum diameter was measured in the coronal plane (a),

axial plane (b) and sagittal plane (c) using the Siemens Picture

Archiving and Communication System (version 4.5; Siemens

Healthineers), with the tumor volume calculated as a × b × c.

Hearing levels were assessed using pure-tone

audiometry (PTA) for air conduction thresholds. Initially, patients

were guided into the auditory evaluation chamber to ensure a

tranquil testing setting for accurate results. Using standard

headphones, audiologists gradually increased the sound volume until

the participants could hear it and then decreased it until they

could no longer hear it. This meticulous procedure allowed accurate

recording of the minimum sound thresholds at which participants

could hear different frequencies. PTA was measured at the

frequencies 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 and 8.0 kHz in each ear and

the average of the thresholds at four frequencies was used to

assess hearing loss (19).

Quantitative variables

The patients' emotional state was assessed using the

Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) (20). A total score of 150 indicated a poor

emotional state. The SCL-90 is a widely used psychological

appraisal instrument to assess an individual's psychological

well-being and emotional disposition. This measure includes 90

items that explore various psychological symptoms and emotions,

including but not limited to anxiety, depression, hostility,

obsession and fear. Participants rate each item based on their

experiences over the past month, providing a detailed view of their

psychological landscape.

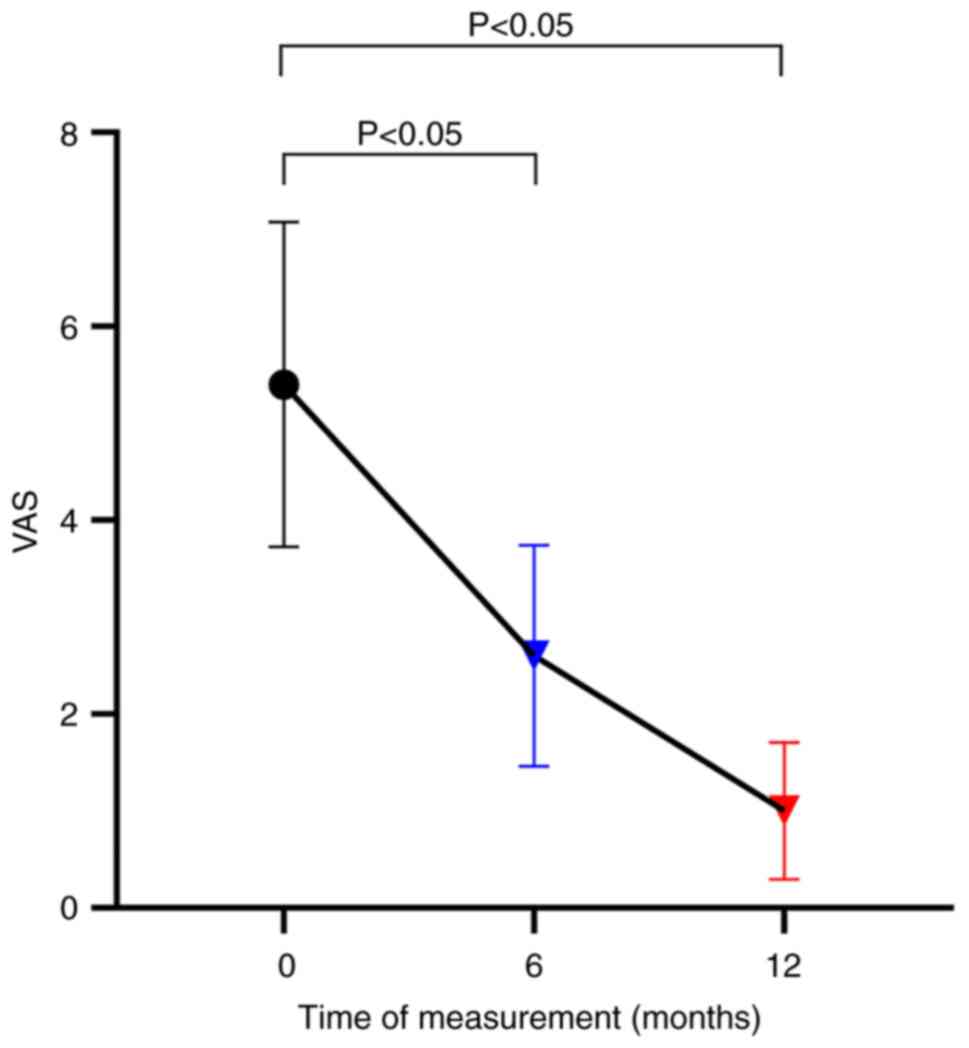

A visual analog scale (VAS) was used to measure the

patient's pain levels (21). The

VAS is a common tool for assessing the intensity of pain or other

attributes based on individual experiences. The VAS consists of a

line of adjustable length, with numerical values at each end

representing diametrically opposed sensations, denoted as 0 and 10.

Patients indicate their pain levels along this continuum to create

a gradient of ratings. Types and severity of adverse reactions are

carefully recorded. Regular follow-ups were conducted through

outpatient clinics or by phone for 12 months.

Research studies assessed patients' overall health

status and functional capacity using the Eastern Cooperative

Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score (22).

The hearing levels, pain and emotional states of the

patients were evaluated by the same two board-certified

neuroradiologists who conducted the MRI imaging assessment.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software

(version 25.0; IBM Corp.) and the R programming language (version

4.3.2; The R Project for Statistical Computing; www.r-project.org). Continuous variables were

expressed using means and standard deviations and categorical data

were presented as counts and percentages. Repeated-measures ANOVA

was used to compare the changes over time (pre- and

post-medication). The normality of the data distribution was tested

using the Shapiro-Wilk test before conducting the analysis.

Non-parametric tests, like the Friedman non-parametric

repeated-measures ANOVA test, were used to compare the change

before and after the medication if the data didn't follow a normal

distribution assumption. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to

visualize time-to-progression differences between age groups, as

previously described in studies analyzing tumor growth dynamics

(17). For the comparison of the

time to disease progression between patients aged <18 and ≥18

years, the log-rank test was initially used. However, considering

the potential issue of survival curves crossing, an alternative

analysis using the Fleming-Harrington test family was also

conducted. Categorical variables were compared with Fisher's exact

test. In this study, multiple hypotheses were tested. To address

the potential increase in Type I error probability, the Bonferroni

correction method was applied for the post-hoc tests. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 12 participants were enrolled with a

median age of 22 years (range, 14–32 years) and a median body mass

index of 21.02 kg/m2 (range, 17.6–26.8

kg/m2). The cohort included nine men (75%) and three

women (25%). The median follow-up time was 20.58 months (range,

12–40 months) (Table I). A total of

nine participants had previous surgeries. The median time from

diagnosis to receiving brigatinib was 13 months (range, 3–30

months). All participants had bilateral vestibular nerve

schwannomas and spinal meningiomas; nine participants had cranial

meningiomas and seven participants had subcutaneous tumors. The

number of participants reporting hearing loss, pain, impaired motor

function, visual impairment and poor emotional states was,

respectively, 10, 5, 6, 7 and 6 (Table

I).

| Table I.Demographics and clinical

characteristics of participants at baseline. |

Table I.

Demographics and clinical

characteristics of participants at baseline.

| Participant

no. | Age, years | Sex | BMI,

kg/m2 | Previous surgical

excision | Time before

brigatinib, years | Follow-up time,

months | Type of

tumora |

Symptomsb |

|---|

| 1 | 30 | Male | 23.1 | Yes | 20 | 24 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| 2 | 32 | Male | 19.4 | Yes | 30 | 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 | 14 | Female | 17.8 | Yes | 13 | 16 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 5 |

| 4 | 19 | Male | 22.7 | Yes | 3 | 38 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| 5 | 26 | Female | 20.4 | Yes | 21 | 18 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| 6 | 32 | Male | 22.3 | Yes | 17 | 24 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| 7 | 17 | Male | 20.1 | No | 3 | 13 | 1, 3 |

|

| 8 | 15 | Male | 19.1 | No | 3 | 12 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2 |

| 9 | 30 | Male | 17.6 | Yes | 10 | 13 | 1, 3 | 1, 2 |

| 10 | 15 | Male | 24.2 | Yes | 12 | 40 | 1, 3, 4 | 3, 4 |

| 11 | 14 | Female | 18.7 | No | 10 | 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1, 3 |

| 12 | 20 | Male | 26.8 | Yes | 14 | 12 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1, 3, 4 |

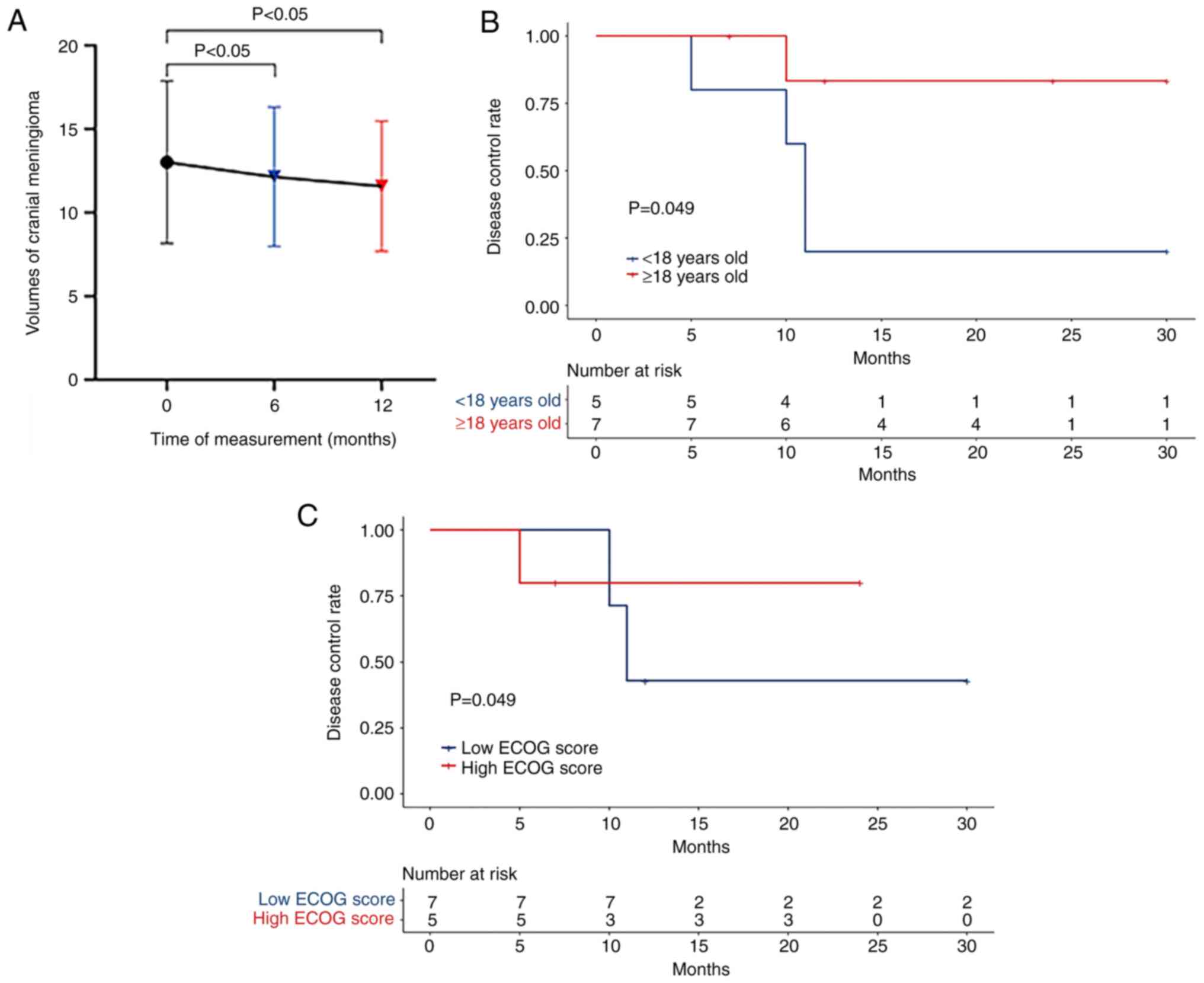

Tumor size

The average size of the meningioma in the brain was

13.00±4.86 mm3 at the start, 12.14±4.12 mm3

at 6 months and 11.58±3.89 mm3 at 12 months, indicating

a significant decrease (P<0.05; Fig.

1A). The time to disease progression was significantly

different between patients aged <18 years and those aged ≥18

years (P=0.049; Fig. 1B), but there

was no significant difference between patients with a low ECOG

score (<2) and high ECOG score (>2) (P>0.05 according to

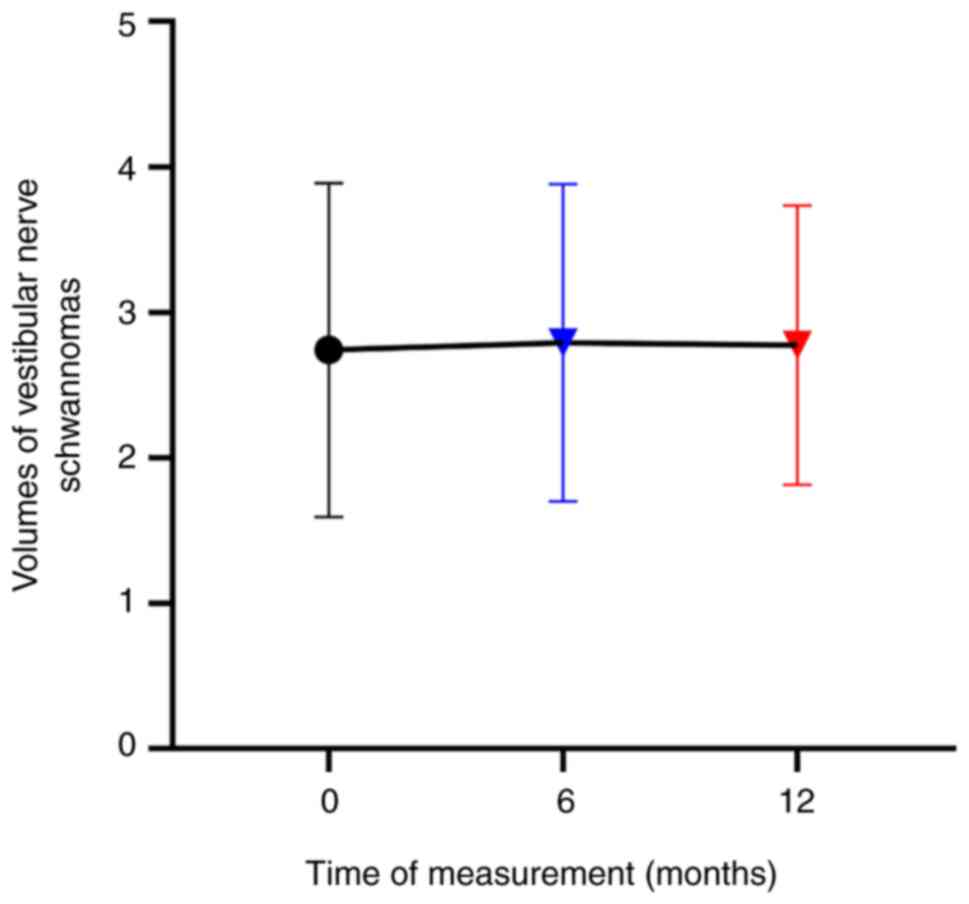

the log-rank test) (Fig. 1C). By

contrast, the volume of vestibular nerve schwannomas showed little

change during drug treatment (Fig.

2).

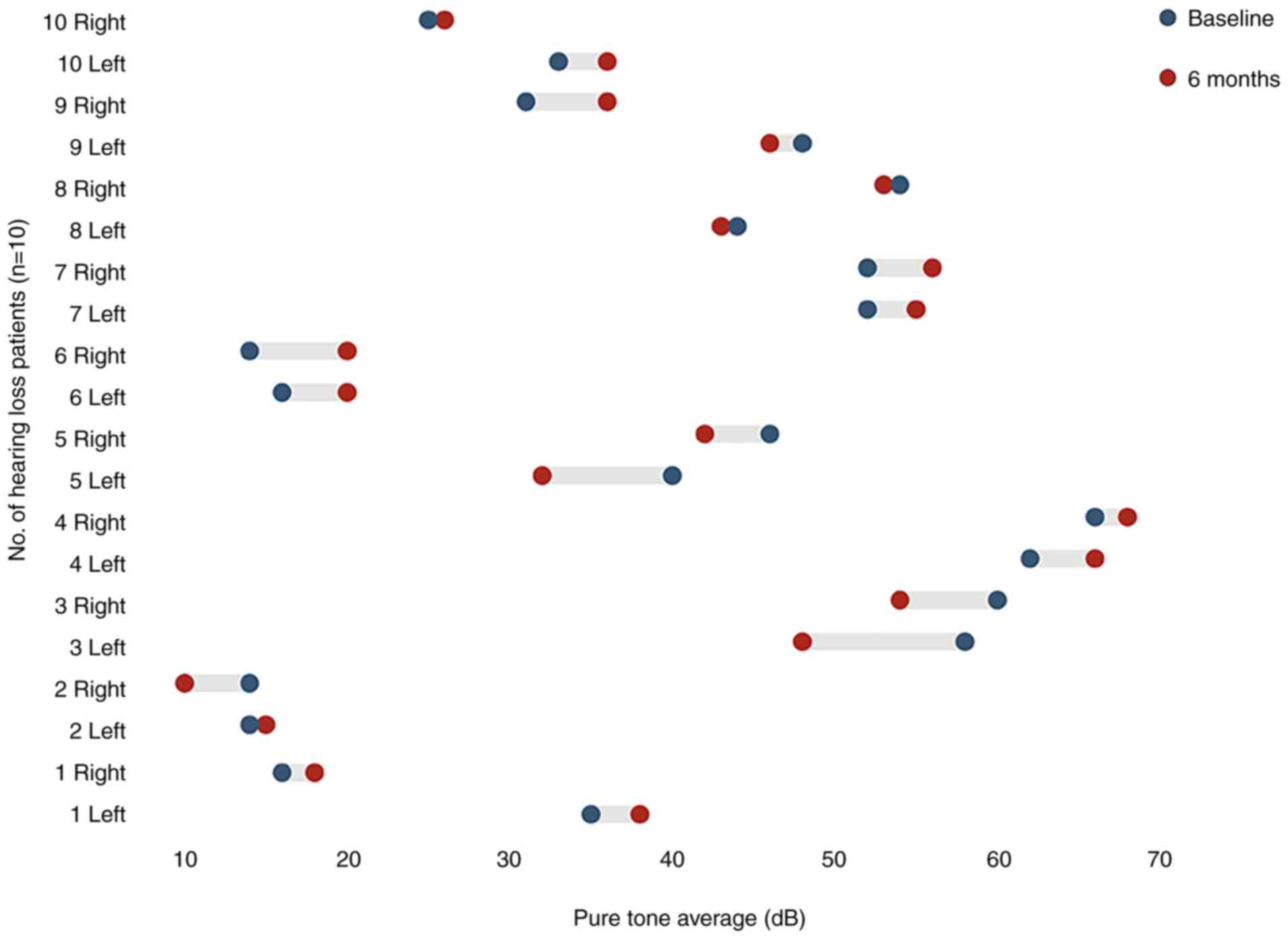

Hearing function, emotional state and

pain

Median PTA thresholds of participants who had

hearing loss (n=10) were 39.90±15.34 dB (left ear) and 38.30±19.37

dB (right ear). After 12 months of treatment, the thresholds were

40.2±16.19 dB (left ear) and 37.80±20.10 dB (right ear). Hearing

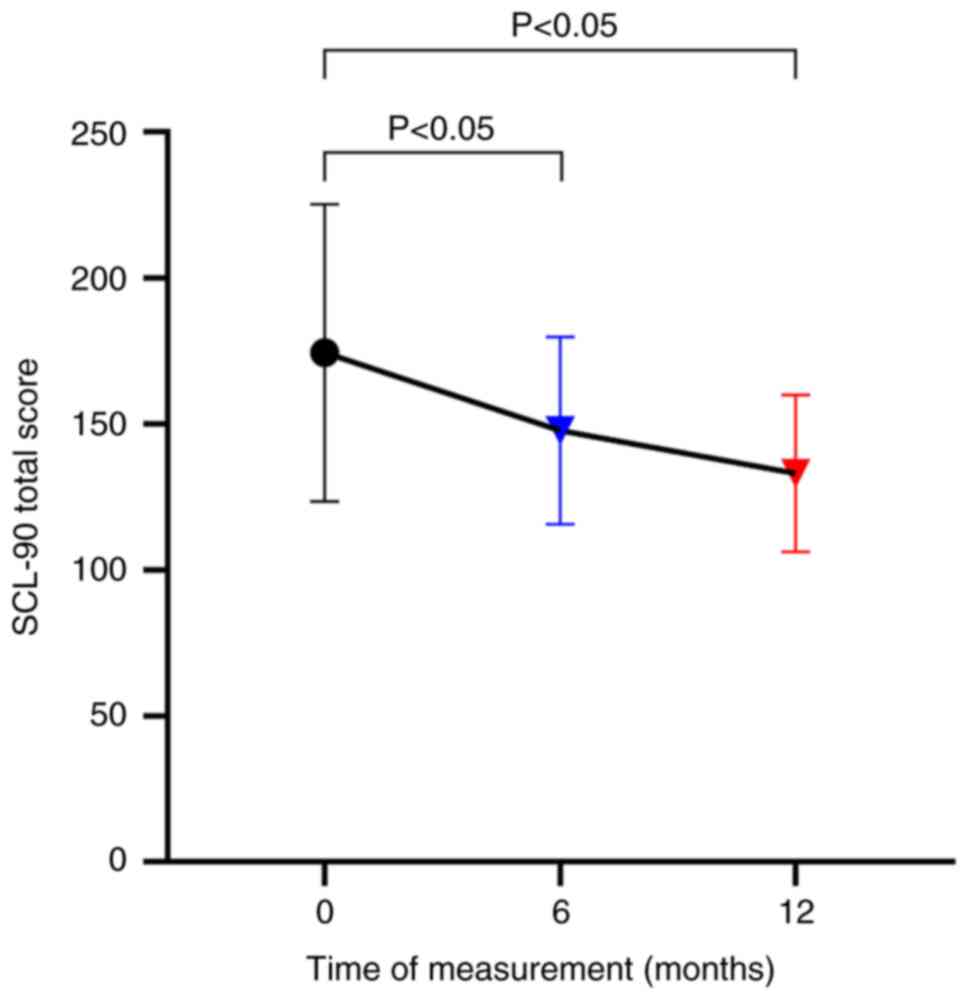

did not significantly improve (P>0.05; Fig. 3). The VAS (Fig. 4) and SCL-90 (Fig. 5) scores were significantly lower at

6 and 12 months compared to the baseline (P<0.05).

Safety

At the 6 months, 17 adverse events were reported:

Hypertension (n=1), diarrhea (n=5), liver dysfunction (n=1),

arrhythmia (n=1), skin rash (n=4) and fatigue (n=5). At 12 months,

19 adverse events were reported: Hypertension (n=2), diarrhea

(n=4), liver dysfunction (n=1), arrhythmia (n=2), skin rash (n=5)

and fatigue (n=5) (Table II).

| Table II.Adverse events occurring in patients

receiving brigatinib. |

Table II.

Adverse events occurring in patients

receiving brigatinib.

| Adverse Event | Total no. of events

(n=36) | 6 months

(n=17) | 12 months

(n=19) |

|---|

| Hypertension | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Diarrhoea | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Liver

dysfunction | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Arrhythmia | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Skin rash | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Fatigue | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Discussion

NF2 is marked by the presence of numerous tumors

within the nervous system that progressively deteriorate over time.

Even though tumors may be classified as histologically benign, they

can lead to significant complications, including hearing and vision

loss, motor function impairment, paralysis, pain and epilepsy,

which are substantial contributors to mortality and disability

(23). Bilateral vestibular

schwannomas are the most prevalent tumors associated with NF2,

occurring in ~90% of cases. Furthermore, it is observed that 45–58%

of individuals with NF2 present with intracranial meningiomas,

while 20% exhibit spinal meningiomas. Meningiomas frequently

present as multiple benign tumors that exert pressure on

surrounding brain tissue and cranial nerves, potentially leading to

seizures and cerebral edema (24).

To date, no effective treatment for NF2 has been

established. Surgery and stereotactic radiosurgery are employed in

the management of tumors; however, their effectiveness is typically

limited to short-term relief. The long-term outlook for patients

continues to be unfavorable (25).

Currently, there is no medication authorized for the treatment of

NF2 tumors. Investigations indicate that bevacizumab, a vascular

endothelial growth inhibitor, has the potential to impede the

growth of NF2-induced acoustic neuromas and may lead to some

enhancement in hearing (26–29).

However, the impact on meningiomas and cutaneous neurofibromas

remains ambiguous.

Chang et al (13) discovered that cells from NF2-related

meningioma and schwannoma do not exhibit ALK expression. In

contrast to NSCLC, where ALK inhibition is applied, brigatinib

demonstrates the ability to inhibit multiple tyrosine kinases, such

as EphA2 and FAK1. Brigatinib has demonstrated the ability to

inhibit the activity of NF2 gene knockout cells and decrease the

volume of meningioma and schwannoma in mice, suggesting its

potential as a treatment for NF2 tumors (13). Building upon the foundation

established by Chang et al (13), the present investigation involved a

follow-up of 12 patients receiving oral therapy with brigatinib.

While brigatinib is mainly focused on targeting tyrosine kinases in

NSCLC, emerging evidence indicates its possible application in NF2.

A phase II trial indicated a 25% tumor response rate and a 35%

improvement in hearing among patients with NF2 receiving brigatinib

at a dosage of 180 mg daily (30).

However, the effectiveness regarding the meningioma volume and

non-auditory symptoms is still uncertain, necessitating additional

research. The present investigation built upon previous findings by

showcasing its efficacy against meningiomas, underscoring a wider

scope of therapeutic possibilities.

NF2 represents an autosomal dominant genetic

disorder resulting from mutations in the NF2 gene. The gene is

responsible for encoding and expressing the Merlin protein in

vivo, predominantly located in Schwann cells, meningeal cells,

lens fiber cells and nerve cells (30). Merlin plays a crucial role in

inhibiting cell proliferation through the regulation of cell-cell

adhesion. Consequently, the loss of Merlin due to mutations in the

NF2 gene results in tumor growth. Merlin engages with various

intracellular signaling pathways, such as receptor tyrosine

kinases. Certain tyrosine kinase inhibitors have shown efficacy in

NF2-deficient mice (31),

indicating that these inhibitors may represent a viable treatment

option for NF2.

Brigatinib demonstrates inhibitory effects on

several receptor tyrosine kinases, such as ALK, ROS1, insulin-like

growth factor-1 receptor and EGFR. However, there is a lack of

studies regarding its application in the treatment of NF2. The

study by Plotkin et al (30)

evaluated the efficacy and safety of brigatinib in the treatment of

NF2-related schwannomatosis. Their results showed that with

brigatinib, significant radiological responses were achieved in

multiple types of tumors. Of the target tumors, 10% (95% CI, 3–24%)

showed shrinkage and 23% (95% CI, 16–30%) of all tumors showed a

response. In addition, ~35% (95% CI, 20–53%) of patients

experienced improved hearing and there was a reduction in

self-reported pain severity. This present study involved the

observation and evaluation of brigatinib's short-term effectiveness

in treating NF2, revealing its potential to reduce the volume of

meningioma. Meningiomas present a range of histological features

and genetic irregularities. Research shows that between 45 and 58%

of individuals with NF2 present with intracranial meningiomas,

while ~20% exhibit spinal meningiomas (32). NF2-related meningiomas predominantly

arise in the supratentorial areas, encompassing the frontal,

parietal and temporal lobes, along with the cerebral falx. The MRI

scans conducted on the patients in this study revealed the presence

of meningiomas in the conventional cranial regions. The mean volume

decreased from baseline. Although the volume change was not

significant, the patient's pain and emotional state improved

significantly. Younger patients (aged <18 years) exhibited a

shorter disease progression time in comparison to their older

counterparts (≥18 years). This may be associated with accelerated

tumor growth in younger individuals (15).

NF2 may lead to peripheral neuropathy, ophthalmic

abnormalities and cutaneous lesions. Patients with NF2 frequently

present with cutaneous lesions; however, these lesions are

generally less pronounced compared to those seen in patients with

NF1. Schwannomas cause significant pain in individuals with NF2.

While the precise mechanisms underlying NF2-related pain remain

incompletely understood, it is suggested that this pain may be

linked to tumor activation and/or the sensitization of primary

sensory afferents through several pathways, such as mechanical

compression of nerves, direct cell-cell signaling and the release

of secretory factors (33).

Currently, surgical resection is recognized as the most effective

and safe approach for addressing pain associated with NF2

peripheral nerve schwannoma (34).

Nonetheless, pain associated with schwannomas frequently continues

after tumor removal and does not seem to have a direct relationship

with the size of the tumor. This indicates that pain could arise

from factors beyond nerve compression (35).

The present investigation evaluated the short-term

effectiveness of brigatinib in the treatment of NF2. An important

advantage of brigatinib is its ability to enhance patients' pain

management and emotional well-being. Follow-up feedback revealed

notable pain relief within 24 h of initiating brigatinib treatment.

Brigatinib primarily focuses on tumor cells by engaging multiple

pathways to impede their growth and dissemination, particularly in

the context of NSCLC. This investigation indicates that brigatinib

may also alleviate tumor-associated pain symptoms through a

reduction in tumor burden. Furthermore, brigatinib has the

potential to offer swift pain relief via additional mechanisms,

warranting further exploration.

The findings suggest that blocking tyrosine kinase

activity may serve as an effective strategy for managing NF2

symptoms and enhancing clinical outcomes. This facilitates further

investigation into tyrosine kinase inhibitors as a possible

treatment for NF2. Nonetheless, there was no observed enhancement

in acoustic neuroma and hearing, likely attributable to the

challenges of addressing all symptoms in patients with NF2 with a

singular pharmacological intervention.

The majority of individuals diagnosed with

vestibular schwannomas demonstrate a reduction in Merlin

expression. Investigations into the associated cellular pathways

triggered by the loss of Merlin have examined these as possible

therapeutic targets for addressing vestibular schwannomas. Merlin's

interaction with ErbB2 facilitates the activation of downstream

MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (36). Activation of ErbB receptors occurs

in both sporadic and NF2-related vestibular schwannomas, with EGF

expression showing an increase in NF2-related cases. This indicates

the potential effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors in the treatment of

NF2-related vestibular schwannomas. Clinical studies indicate that

the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib does not have a significant impact on

hearing or tumor size in patients with progressive vestibular

schwannoma (37).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target EGFR/ErbB2

show variable efficacy in reducing tumor size and enhancing hearing

in NF2-related vestibular schwannomas, presenting challenges in

their role as effective treatment options. The levels of VEGF and

its receptors are increased in schwannomas, showing an association

with tumor growth and volume. VEGF inhibitors, such as bevacizumab,

have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in vestibular schwannomas,

notably enhancing hearing and decreasing tumor size. Nonetheless,

the administration of bevacizumab poses several challenges, such as

the requirement for regular parenteral delivery, potential side

effects, noticeable drug resistance and the possibility of rebound

tumor progression (38). Numerous

investigations into the use of bevacizumab for vestibular

schwannomas depend on brief follow-up periods and are deficient in

long-term findings. Brigatinib engages in distinct pathways

compared to those that have demonstrated efficacy in reducing tumor

size and enhancing hearing in NF2-related vestibular schwannomas.

This may clarify the absence of observed improvements in acoustic

schwannoma size or hearing in the present study. Besides, the study

by Plotkin et al (30)

observed a certain degree of hearing improvement, but in the

present study, there was no significant improvement in the volume

of acoustic neuroma or the average hearing threshold (P>0.05).

This difference may be, to a certain extent, attributed to the

variation in sample size.

The small cohort of patients with NF2 and the

elevated expense of brigatinib constrained the sample size of the

present study, complicating the evaluation of brigatinib's impact

on spinal tumors in NF2. This may clarify the absence of progress

in vestibular schwannomas and auditory function. In the interim,

additional clinical observation is required to assess the long-term

efficacy of brigatinib in the treatment of NF2.

The main adverse effects noted during the trial

included fatigue, skin rash and diarrhea, none of which resulted in

the cessation of the medication. No significant adverse reactions

were observed; however, one patient experienced severe anemia.

Given the patient's history of anemia, which showed improvement

following treatment, anemia may not be associated with brigatinib.

No instances of anemia were reported in other studies involving

brigatinib (39,40).

Of note, the present study has several limitations.

NF2 exhibits a wide range of clinical manifestations that differ

significantly from one individual to another, complicating the

development of a universal treatment that can effectively address

all patient symptoms. Tailored approaches that involve

collaboration across various disciplines could prove to be a

promising strategy in the management of NF2. In addition, further

clinical drug studies are essential to generate evidence and

explore new therapeutic possibilities for NF2. The limited sample

size (n=12) restricts the statistical power of the findings.

Although selection bias was minimized by continuously enrolling all

eligible patients, as this study was based on a retrospective

dataset, selection bias may still exist. Certain patients may not

have been included in the study due to milder or more severe

conditions, which may result in the sample of the present study not

fully representing the entire NF2 patient population. It is

essential to validate these findings through larger, multicenter

trials. Although both the log-rank test and Cox model indicated a

significant relationship between age and progression risk, it is

essential to interpret these findings with caution and validate

them in larger cohorts.

In conclusion, the present findings indicate that

brigatinib has a notable impact on reducing meningioma volume in

individuals with NF2, while also enhancing their emotional health

and relieving pain. Nonetheless, the effect on vestibular

schwannoma volume and hearing thresholds is not significant.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZL and WY were involved in the conception and design

of the study and analyzed data. FJ and ZX collected the data and

helped with the data analysis. ML and SJ helped with the data

analysis, drafted and proofread the manuscript, performed final

editing and are guarantors of the study. ML and SJ confirm the

authenticity of the raw data. All authors have checked and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and approved by the Institutional

Review Board (IRB) of The First Medical Center of Chinese PLA

General Hospital (Beijing, China; IRB approval no. S2021-409-01).

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and

written parental consent was secured for minors, consistent with

ethical guidelines for pediatric research.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rouleau GA, Merel P, Lutchman M, Sanson M,

Zucman J, Marineau C, Hoang-Xuan K, Demczuk S, Desmaze C,

Plougastel B, et al: Alteration in a new gene encoding a putative

membrane-organizing protein causes neuro-fibromatosis type 2.

Nature. 363:515–521. 1993. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Asthagiri AR, Parry DM, Butman JA, Kim HJ,

Tsilou ET, Zhuang Z and Lonser RR: Neurofibromatosis type 2.

Lancet. 373:1974–1986. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Slattery WH: Neurofibromatosis type 2.

Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 48:443–460. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Evans DG, Baser ME, O'Reilly B, Rowe J,

Gleeson M, Saeed S, King A, Huson SM, Kerr R, Thomas N, et al:

Management of the patient and family with neurofibromatosis 2: A

consensus conference statement. Br J Neurosurg. 19:5–12. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Plotkin SR, Messiaen L, Legius E, Pancza

P, Avery RA, Blakeley JO, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Ferner R, Fisher

MJ, Friedman JM, et al: Updated diagnostic criteria and

nomenclature for neurofibromatosis type 2 and schwannomatosis: An

international consensus recommendation. Genet Med. 24:1967–1977.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Okada T, You L and Giancotti FG: Shedding

light on Merlin's wizardry. Trends Cell Biol. 17:222–229. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang N, Bai H, David KK, Dong J, Zheng Y,

Cai J, Giovannini M, Liu P, Anders RA and Pan D: The Merlin/NF2

tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate

tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 19:27–38. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Apra C, Peyre M and Kalamarides M: Current

treatment options for meningioma. Expert Rev Neurother. 18:241–249.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Angus SP, Oblinger JL, Stuhlmiller TJ,

DeSouza PA, Beauchamp RL, Witt L, Chen X, Jordan JT, Gilbert TSK,

Stemmer-Rachamimov A, et al: EPH receptor signaling as a novel

therapeutic target in NF2-deficient meningioma. Neuro Oncol.

20:1185–1196. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mohanty A, Pharaon RR, Nam A, Salgia S,

Kulkarni P and Massarelli E: FAK-targeted and combination therapies

for the treatment of cancer: An overview of phase I and II clinical

trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 29:399–409. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Markham A: Brigatinib: First global

approval. Drugs. 77:1131–1135. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hoy SM: Brigatinib: A review in

ALK-inhibitor Naïve advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. Drugs. 81:267–275.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chang LS, Oblinger JL, Smith AE, Ferrer M,

Angus SP, Hawley E, Petrilli AM, Beauchamp RL, Riecken LB, Erdin S,

et al: Brigatinib causes tumor shrinkage in both NF2-deficient

meningioma and schwannoma through inhibition of multiple tyrosine

kinases but not ALK. PLoS One. 16:e02520482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, Pikus

A, Kaiser-Kupfer MI and Eldridge R: NIH conference.

Neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis

2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update. Ann Intern

Med. 113:39–52. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Evans DG, Huson SM, Donnai D, Neary W,

Blair V, Newton V and Harris R: A clinical study of type 2

neurofibromatosis. Q J Med. 84:603–618. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Baser ME, Friedman JM, Wallace AJ, Ramsden

RT, Joe H and Evans DGR: Evaluation of clinical diagnostic criteria

for neurofibromatosis 2. Neurology. 59:1759–1765. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han

JY, Hochmair MJ, Lee KH, Delmonte A, Garcia Campelo MR, Kim DW, et

al: Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK inhibitor-naive advanced

ALK-positive NSCLC: Final results of phase 3 ALTA-1L trial. J

Thorac Oncol. 16:2091–2108. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Walia A, Tuia J and Prasad V:

Progression-free survival, disease-free survival and other

composite end points in oncology: Improved reporting is needed. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 20:885–895. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Carl AC, Hohman MH and Cornejo J:

Audiology pure tone evaluation. [2023 Mar 1]. StatPearls [Internet]

Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025

|

|

20

|

Kostaras P, Martinaki S, Asimopoulos C,

Maltezou M and Papageorgiou C: The use of the symptom checklist

90-R in exploring the factor structure of mental disorders and the

neglected fact of comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 294:1135222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McCormack HM, Horne DJ and Sheather S:

Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: A critical review.

Psychol Med. 18:1007–1019. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Azam F, Latif MF, Farooq A, Tirmazy SH,

AlShahrani S, Bashir S and Bukhari N: Performance status assessment

by using ECOG (eastern cooperative oncology group) score for cancer

patients by oncology healthcare professionals. Case Rep Oncol.

12:728–736. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Grossen A, Gavula T, Chrusciel D, Evans A,

McNall-Knapp R, Taylor A, Fossey B, Brakefield M, Carter C,

Schwartz N, et al: Multidisciplinary neurocutaneous syndrome

clinics: A systematic review and institutional experience.

Neurosurg Focus. 52:E22022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mautner VF, Lindenau M, Baser ME, Hazim W,

Tatagiba M, Haase W, Samii M, Wais R and Pulst SM: The neuroimaging

and clinical spectrum of neurofibromatosis 2. Neurosurgery.

38:880–886. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Coy S, Rashid R, Stemmer-Rachamimov A and

Santagata S: An update on the CNS manifestations of

neurofibromatosis type 2. Acta Neuropathol. 139:643–665. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Blakeley JO, Ye X, Duda DG, Halpin CF,

Bergner AL, Muzikansky A, Merker VL, Gerstner ER, Fayad LM, Ahlawat

S, et al: Efficacy and biomarker study of bevacizumab for hearing

loss resulting from neurofibromatosis type 2-associated vestibular

schwannomas. J Clin Oncol. 34:1669–1675. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lu VM, Ravindran K, Graffeo CS, Perry A,

Van Gompel JJ, Daniels DJ and Link MJ: Efficacy and safety of

bevacizumab for vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. J

Neurooncol. 144:239–248. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tamura R, Fujioka M, Morimoto Y, Ohara K,

Kosugi K, Oishi Y, Sato M, Ueda R, Fujiwara H, Hikichi T, et al: A

VEGF receptor vaccine demonstrates preliminary efficacy in

neurofibromatosis type 2. Nat Commun. 10:57582019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Plotkin SR, Allen J, Dhall G, Campian JL,

Clapp DW, Fisher MJ, Jain RK, Tonsgard J, Ullrich NJ, Thomas C, et

al: Multicenter, prospective, phase II study of maintenance

bevacizumab for children and adults with NF2-related

schwannomatosis and progressive vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol.

25:1498–1506. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Plotkin SR, Yohay KH, Nghiemphu PL, Dinh

CT, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Merker VL, Bakker A, Fell G, Trippa L and

Blakeley JO; INTUITT-NF2 Consortium, : Brigatinib in NF2-related

schwannomatosis with progressive tumors. N Engl J Med.

390:2284–2294. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

den Bakker MA, Vissers KJ, Molijn AC, Kros

JM, Zwarthoff EC and van der Kwast TH: Expression of the

neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in human tissues. J Histochem

Cytochem. 47:1471–1480. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Paldor I, Abbadi S, Bonne N, Ye X,

Rodriguez FJ, Rowshanshad D, Itzoe M, Vigilar V, Giovannini M, Brem

H, et al: The efficacy of lapatinib and nilotinib in combination

with radiation therapy in a model of NF2 associated peripheral

schwannoma. J Neurooncol. 135:47–56. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Coy S, Rashid R, Stemmer-Rachamimov A and

Santagata S: Correction to: An update on the CNS manifestations of

neurofibromatosis type 2. Acta Neuropathol. 139:6672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kukutla P, Ahmed SG, DuBreuil DM,

Abdelnabi A, Cetinbas M, Fulci G, Aldikacti B, Stemmer-Rachamimov

A, Plotkin SR, Wainger B, et al: Transcriptomic signature of

painful human neurofibromatosis type 2 schwannomas. Ann Clin Transl

Neurol. 8:1508–1514. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Peyre M, Tran S, Parfait B, Bernat I,

Bielle F and Kalamarides M: Surgical management of peripheral nerve

pathology in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Neurosurgery.

92:317–328. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mohammed N, Hung YC, Xu Z, Chytka T,

Liscak R, Tripathi M, Arsanious D, Cifarelli CP, Perez Caceres M,

Mathieu D, et al: Neurofibromatosis type 2-associated meningiomas:

An international multicenter study of outcomes after Gamma Knife

stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurosurg. 136:109–114. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fernandez-Valle C, Tang Y, Ricard J,

Rodenas-Ruano A, Taylor A, Hackler E, Biggerstaff J and Iacovelli

J: Paxillin binds schwannomin and regulates its density-dependent

localization and effect on cell morphology. Nat Genet. 31:354–562.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Plotkin SR, Halpin C, McKenna MJ, Loeffler

JS, Batchelor TT and Barker FG II: Erlotinib for progressive

vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis 2 patients. Otol

Neurotol. 31:1135–1143. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tamura R, Tanaka T, Miyake K, Yoshida K

and Sasaki H: Bevacizumab for malignant gliomas: Current

indications, mechanisms of action and resistance, and markers of

response. Brain Tumor Pathol. 34:62–77. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JC, Han

JY, Lee JS, Hochmair MJ, Li JY, Chang GC, Lee KH, et al: Brigatinib

versus crizotinib in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N

Engl J Med. 379:2027–2039. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|