Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) constitutes the

predominant subtype of lung cancer (LC), comprising ~40% of all LC

cases (1,2). The treatment of LUAD is tailored to

the stage and severity of the disease, typically involving a

combination of approaches such as surgery, radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy (3). Despite these diverse treatment

strategies, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of patients with

LUAD remains low, at ~15%, and few patients achieve complete

remission (4,5). Accordingly, exploring the molecular

basis of LUAD and seeking novel biomolecules for therapeutic

purposes is a priority.

RNA helicases are essential regulators of several

aspects of RNA metabolism, including transcription, RNA splicing,

transport, storage, degradation, ribosome biogenesis and

translation (6–8). By modulating the expression levels of

oncogenes, RNA helicases contribute to tumorigenesis and

advancement (9). Additionally, they

are implicated in several pathological processes, such as

neurological disorders, viral infections and aging (10). Among these, the DEAD-box (DDX)

family stands out as a key group of human RNA helicases (11), with increasing evidence supporting

their involvement in human tumorigenesis. Specifically, DDX46,

located on chromosome 5q31.1, is a member of the DDX family. During

pre-mRNA splicing and in the assembly of the spliceosome, DDX46

functions as a component of the 17S U2 small nuclear

ribonucleoprotein complex (12).

Moreover, studies using zebrafish models have demonstrated that

DDX46 is crucial for the multilineage differentiation of

hematopoietic stem cells, as well as for the development of the

digestive organs and the brain (9).

Previous research has also reported that DDX46 is notably

overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, where its

silencing inhibits the Akt/IκBα/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby

inducing apoptosis (13). In

osteosarcoma, DDX46 knockdown reduces tumor cell proliferation,

migration and invasion (14).

Furthermore, heightened expression of DDX46 has been reported in

gastric cancer, where it is activated via the Akt/GSK/β-catenin

pathway, promoting cancer cell proliferation and invasion (15). However, the relationship between

DDX46 expression and LUAD progression remains unclear, and further

investigation is needed to elucidate its potential role in

LUAD.

The present study aimed to systematically assess the

expression, pathological roles and the molecular basis of DDX46 in

LUAD. To achieve this, a synergistic approach was employed that

integrated bioinformatics analysis with experimental

techniques.

Materials and methods

Public databases

The gene expression and clinical data from 535 LUAD

samples (Table SI) and 59 normal

lung tissue samples (16) were

obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (www.portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Data processing was

performed using R (version 3.6.3, The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing; http://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-3/R-3.6.3.tar.gz/)

and Strawberry Perl (version 5.40.0.1; http://strawberryperl.com/).

Tissue specimens

A total of 20 pairs of fresh LUAD samples with their

corresponding adjacent tissues, as well as 263 paraffin-embedded

LUAD tissue blocks, were collected from the Affiliated Hospital of

Nantong University (Nantong, China) between January 2012 and

December 2015. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

pathologically diagnosed with LUAD; ii) no history of other

malignant tumors; iii) sufficient samples available from the first

visit for immunohistochemical analysis; iv) no prior anticancer

treatment before surgery. Patients who did not meet the

aforementioned criteria were not included in the present study.

Tissue microarrays were carefully prepared by integrating the

paraffin blocks with LUAD samples. The clinicopathological

characteristics of the patients from which the samples were

collected encompassed age, sex, smoking history, tumor

differentiation, clinical stage, tumor stage (T), lymph node

metastasis stage (N) and distant metastasis stage (M), along with

survival duration and outcome. Prior to surgery, all patients

provided written informed consent, confirming their clear

understanding of the risks and benefits associated with the

procedure. The study protocol and data collection were approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong

University (approval no. 2022-L078).

Western blot analysis

Protein extraction was performed using RIPA buffer

(cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), followed by

the measurement of total protein concentration in the samples. The

total protein concentration in the samples was measured using a

bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (cat. no. P0010; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), following the manufacturer's

instructions. This method ensures accurate quantification of

protein content before proceeding with western blot analysis. For

western blot analysis, equal amounts of total protein (20 µg/lane)

were mixed with appropriate volumes of 5X SDS-PAGE loading buffer

to ensure uniform loading volume across all lanes. Proteins were

separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and were then transferred onto a

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked

with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 at

room temperature for 1 h to prevent non-specific binding. For

antibody incubation, the PVDF membrane was then incubated overnight

at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-DDX46 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab72083; Abcam), anti-adenomatous polyposis coli (APC;

1:1,000, cat. no. ab40778; Abcam), anti-β-catenin (1:5,000; cat.

no. 51067-2-AP, Proteintech Group, Inc.) and anti-β-actin (1:4,000;

cat. no. 20536-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Subsequently, the

membrane was incubated with a HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

secondary antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h. Protein signals were visualized

using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (cat. no.

180-5001; Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). Densitometric

analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53;

National Institutes of Health).

Tissue chips immunohistochemical

staining and analysis

The. LUAD and adjacent tissue sections were fixed in

10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h,

embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm. For

immunohistochemical staining and analysis of tissue chips, antigen

retrieval was performed using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 98°C for

20 min, followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

and rehydration through a descending ethanol series (100, 95, 85

and 75%). Subsequently, the sections were incubated with 3%

hydrogen peroxide for 20 min to inhibit endogenous peroxidase

activity, followed by blocking with 5% normal rabbit serum (cat.

no. ab7487; Abcam) at room temperature for 30 min. The sections

were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-DDX46 antibodies

(1:200; cat. no. ab72083; Abcam), followed by incubation with an

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500

dilution; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h to

enable signal detection. DDX46 staining was primarily localized in

the nucleus of the cells. Immunohistochemical staining was

evaluated and scored following the methodology described in our

previous study (17).

Cell culture

The present study employed the following cell lines:

BEAS-2B, PC-9, H1299, A549 and H1975, which were purchased from The

Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of

Sciences. BEAS-2B and A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium (cat. no. 11965092; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), whereas PC-9, H1299, and H1975 cells were

cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium

(cat. no. 11875093; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) The

medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

10099141; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) to prevent bacterial contamination. Cells were

maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2.

Lentiviral transfection

Pre-packaged lentiviruses containing DDX46 short

hairpin RNA (shRNA) and negative control (NC) shRNA were purchased

from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. and were used directly for cell

infection according to the manufacturer's instructions. The shRNAs

were cloned into a GV248 plasmid backbone

(U6-MCS-Ubiquitin-EGFP-IRES-puromycin). The following sequences

were used: DDX46-shRNA#1,

5′-GATCCGCAGAAATCACCAGGCTCATACTCGAGTATGAGCCTGGTGATTTCTGCTTTTTG-3′

and

5′-AATTCAAAAAGCAGAAATCACCAGGCTCATACTCGAGTATGAGCCTGGTGATTTCTGCG-3′;

DDX46-shRNA#2,

5′-GATCCCCTGTGCTGGTCTATGATGTACTCGAGTACATCATAGACCAGCACAGGTTTTTG-3′

and

5′-AATTCAAAAACCTGTGCTGGTCTATGATGTACTCGAGTACATCATAGACCAGCACAGGG-3′;

and NC-shRNA, 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ and

5′-AAGAGGCTTGCACAGTGCA-3′. According to the manufacturer's

instructions, PC-9 and H1299 cells were infected with concentrated

lentiviruses containing either NC-shRNA or DDX46-shRNA at a

multiplicity of infection of 40 in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium

supplemented with 8 µg/ml polybrene. After 24 h, the supernatant

was replaced with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS. After 72 h

of infection, the cells were selected with puromycin at a

concentration of 2 µg/ml for 3 days, and were maintained in medium

containing 1 µg/ml puromycin for subsequent experiments. The

efficiency of NC-shRNA or DDX46-shRNA in infected cells was

assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (RT-qPCR).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay

After transfecting NC-shRNA and DDX46-shRNA into

LUAD cells (PC-9 and H1299) for 48 h, the cells were collected,

resuspended and seeded at a concentration of 1×103

cells/well in a 96-well plate. The plate was subsequently incubated

at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24–96 h. Following the

incubation period, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. C0042; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was added to each well, and the plate

was incubated for an additional 2.5 h to allow the reagent to react

with the viable cells. Microplate readers were used to measure the

absorbance (optical density) of each well at 450 nm, and cell

viability was calculated from the absorbance value.

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

assay

After transfecting NC-shRNA and DDX46-shRNA for 48

h, H1299 and PC-9 cells (4×104 cells/well) were seeded

in a 24-well plate and incubated with EdU solution (cat. no.

C0075S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 2 h. Following

fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature,

cells were permeabilized for 15 min with 0.3% Triton X-100. The

cells were then incubated in the dark for 30 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Hoechst for

10 min at room temperature (Beyotime Biotechnology of

Biotechnology) and examined under a fluorescence microscope to

record the results.

Colony formation assay

Cells transfected with sh-NC and sh-DDX46 were

separately seeded at a density of 1,000 cells/well in a 6-well

plate and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 weeks.

Once colonies had formed, at room temperature the cells were fixed

with formaldehyde for 20 min and then stained with 0.5% crystal

violet solution for 10 min. Colonies were defined as cell clusters

containing ≥50 cells, indicating proliferation from a single cell.

Stained colonies were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.53) with

the Colony Counter plugin.

Detection of cell cycle

LUAD cells transfected with sh-NC and sh-DDX46 were

trypsinized, fixed with 70% ethanol at −20°C, cultured for 24 h,

washed with pre-chilled PBS at 4°C, and then incubated with 500 µl

PI/RNAse solution (cat. no. 550825; BD Biosciences) for 30 min at

37°C in the dark. Cell cycle analysis was performed using a BD

FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed using

FlowJo v10.8 (BD Biosciences).

Wound healing assay

A wound was created by scratching the sh-NC- and

sh-DDX46-transfected cells in 6×-well plates using a 100-µl pipette

tip. After scratching, the cells were washed with PBS to remove

debris and then cultured in serum-free medium to minimize

proliferation during the assay. A microscope was used to observe

the healing progress at 0, 24 and 48 h and the wound healing area

percentage was determined using Image J software (version 1.53). At

the start of the study, cells on either side of the wound were at

100% confluence. Microscopic images were captured using an Olympus

IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Transwell assay

Cell migration was evaluated using Transwell

chambers (Corning, Inc.) with an 8-µm pore size. Initially, sh-NC-

and sh-DDX46-transfected cells were suspended in incomplete medium

and then seeded at a density of 2×104 cells/well in the

upper Transwell chamber. The lower chamber was filled with

RPMI-1640 and 10% FBS, and the cell culture was incubated at 37°C

with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After the cells migrated through

the chamber membrane, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet

solution for 10 min. Subsequently, cell images were captured using

an Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope, and the number of

cells in the lower chamber was counted.

RT-qPCR

LUAD cells transfected with sh-NC and sh-DDX46 were

lysed with TRIzol™ reagent (cat. no. 15596026CN; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), following the manufacturer's

instructions. Chloroform, isopropanol and 75% ethanol were then

added to the cells, and the total RNA was extracted. A PCR machine

(Applied Biosystems 2720 Thermal Cycler; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) was used to run at the following conditions to obtain cDNA

using RT (cat. no. R222-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.): 42°C for 1 h

and 70°C for 10 min. SYBR Green (SYBR™ Green Master Mix;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for qPCR detection and the

qPCR thermocycling conditions included an initial denaturation step

at 95°C for 2–3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10–15 sec

and 60°C for 30 sec with fluorescence detection. Melt curve

analysis was performed at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min and a

gradual increase to 95°C (0.1°C/sec) with continuous fluorescence

acquisition. The forward and reverse sequences used were as

follows: DDX46 forward, 5′-AAGCTCTTGAATTGTCAGGGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCCTTACCAGAGAACCCACT-3′; and β-actin forward,

5′-AGTTGCGTTACACCCTTTCTTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCTGTCACCTTCACCGTTCC-3′. The 2−ΔΔCq method was used

for relative quantification of gene expression, with normalization

to β-actin as the internal reference gene (18).

TUNEL assay

The apoptotic rate of LUAD cells transfected with

sh-NC and sh-DDX46 was assessed using TUNEL staining. The control

and DDX46 knockdown groups were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for

30 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.3%

Triton X-100 for 5 min. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with

TUNEL detection solution at 37°C for 60 min in the dark. Subsequent

Hoechst staining for 15 min at room temperature facilitated cell

imaging using a fluorescence microscope. The mounting medium used

for fluorescence microscopy was Fluoromount-G™ (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 10 random fields per sample were

observed to ensure statistical reliability.

Single-cell analysis of DDX46

The Tumor Immune Single-cell Hub (TISCH; www.tisch.comp-generations.org/home/)

is a comprehensive database designed to facilitate several

single-cell analyses, containing nearly 190 samples (19). The present study specifically

focused on the distribution of DDX46 across different cell

subpopulations in LUAD; therefore, single-cell RNA sequencing data

was downloaded from the GSE117570 dataset (20) within the TISCH database to assess

DDX46 expression levels across different cell types. The expression

levels of DDX46 were quantified and visualized using scatter and

violin plots.

Immune infiltration analysis

Utilizing CIBERSORT (version 1.0; http://cibersort.stanford.edu/), an analysis was

performed to assess the correlation between DDX46 and

tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs), evaluating the connection

between DDX46 expression levels and the prevalence of eight

distinct types of TIICs (21). To

analyze the correlation between DDX46 expression and immune

checkpoints and chemokines, gene expression levels were extracted

for seven immune checkpoints and 40 chemokines. Spearman

correlation analysis was performed and correlation heatmaps were

generated using the reshape2 (version 1.4.4; http://cran.r-project.org/package=reshape2),

corrplot (version 0.95; http://cran.r-project.org/package=corrplot), boot

(version 1.3–28.1; http://cran.r-project.org/package=boot), and ggplot2

packages (version 3.5.1; http://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2) in R

(version 4.1.3; http://www.r-project.org/).

Enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis and the functional annotation of

genes was performed using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

website (www.software.broadinstitute:gsea/index.jsp). GSEA

is a widely utilized method for gene enrichment analysis that

assesses the enrichment levels of predefined gene sets within

specific biological processes, signaling pathways or diseases by

evaluating their correlation with these processes (22). GSEA enrichment analysis was

performed to annotate the sample genetics with Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp/). The screening criteria were as

follows: P<0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05.

Drug sensitivity analysis of

DDX46

The largest public pharmacogenomics resource, the

Cancer Drug Sensitivity Genomics website (www.cancerrxgene.org/), provided the anticancer drug

dataset used in the present study (23). To assess the association between

IC50 values of diverse anticancer drugs and DDX46

expression groups, the oncoPredict package 1.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/oncoPredict/index.html)

was used. Subsequently, statistical analysis of drug sensitivity

within these groups was performed using the R package ‘pRRophetic’

0.5 (https://github.com/paulgeeleher/pRRophetic) to assess

differences in drug response levels among patients in different

risk groups.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

or mean ± standard error of the mean for continuous variables,

whereas categorical variables are presented as percentages or

frequencies. Three independent biological replicates (n=3) were

performed for in vitro experiments. Paired t-tests were used

to compare normal and malignant tissues from the same patient,

whilst unpaired t-tests were employed for comparisons between two

independent groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was

performed to compare ≥3 groups. Dunnett's multiple comparison test

was subsequently applied to compare each experimental group with

the control, whilst controlling for the familywise error rate,

provided the ANOVA result revealed significant differences

(P<0.05). The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to

evaluate the relationship between lung cancer prognosis and DDX46

expression levels, comparing both low and high expression groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26

(IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 10 (Dotmatics).

Results

Increased expression of DDX46 in LUAD

samples

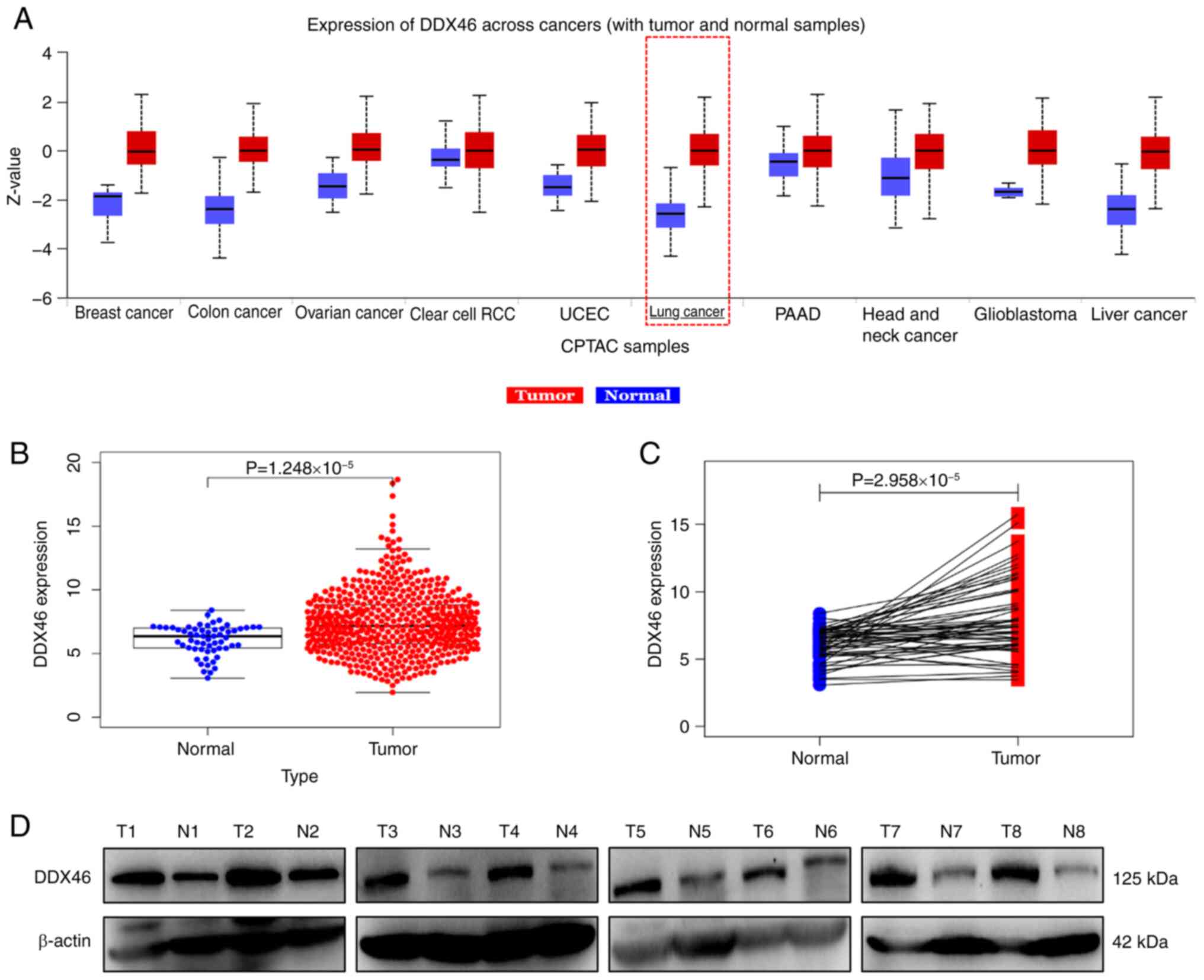

At the proteome level, DDX46 was demonstrated to be

significantly overexpressed in several tumor tissues, including

lung cancer, compared with that in normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Specifically in LUAD, DDX46

expression was revealed to be significantly higher in LUAD tissues

compared with that in normal lung tissues (Fig. 1B and C). Furthermore, western blot

analysis of eight LUAD samples and matched normal lung tissues

further demonstrated a marked increase in DDX46 protein levels in

LUAD tissues (Fig. 1D).

Association between DDX46 expression

and clinicopathological characteristics, along with the prognosis

of patients with LUAD

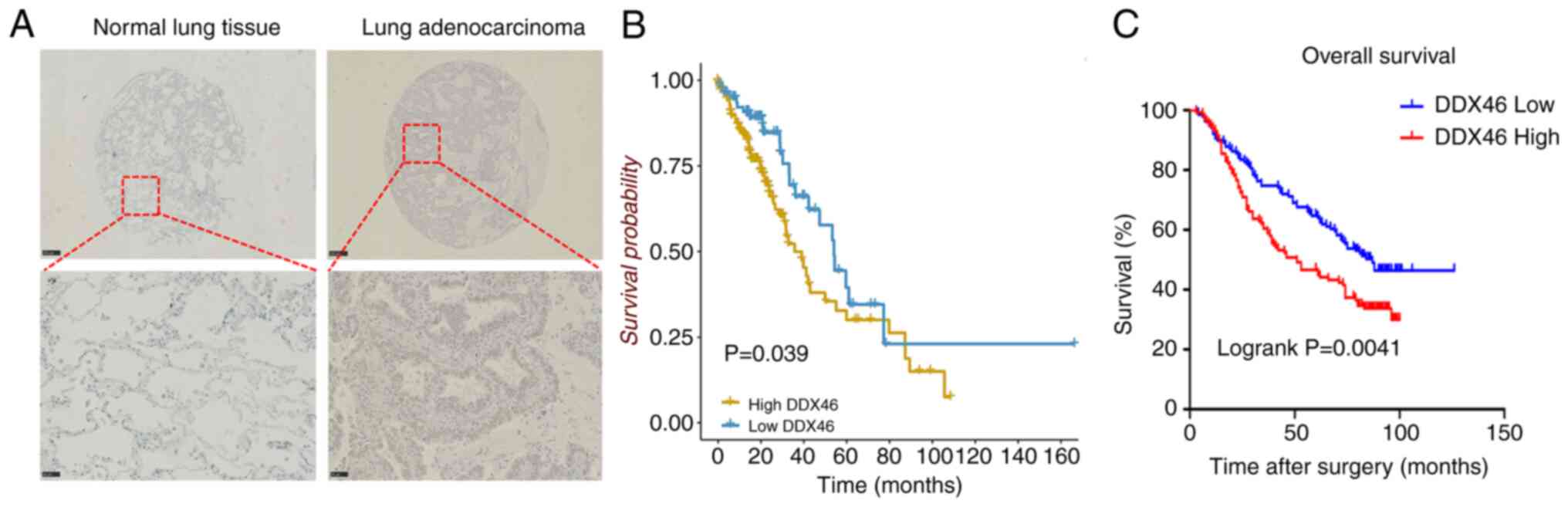

To assess the relationship between DDX46 expression

and clinicopathological characteristics, as well as patient

prognosis in LUAD, immunohistochemical staining was performed on

263 LUAD samples. The results revealed that DDX46 was predominantly

localized in the nucleus and had notably higher expression levels

in LUAD tissues than in adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 2A). Moreover, DDX46 expression was

significantly associated with stage (P=0.007) and T classification

(P=0.036), whilst no statistically significant associations were

demonstrated for age, sex, smoking history, differentiation degree

or N classification (all P>0.05) (Table I).

| Table I.Association between DEAD-box 46

expression and pathological parameters of lung adenocarcinoma. |

Table I.

Association between DEAD-box 46

expression and pathological parameters of lung adenocarcinoma.

|

|

| DDX46 expression,

n |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinical

parameter | Total, n | Low | High | P-value |

|---|

| Age |

|

|

| 0.403 |

| ≤60

years | 108 | 60 | 48 |

|

| >60

years | 155 | 78 | 77 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.210 |

|

Male | 160 | 79 | 81 |

|

|

Female | 103 | 59 | 44 |

|

| Smoking |

|

|

| 0.548 |

|

Nonsmoker | 212 | 113 | 99 |

|

|

Smoker | 51 | 25 | 26 |

|

| Stage |

|

|

| 0.007a |

| I +

II | 189 | 109 | 80 |

|

| III +

IV | 74 | 29 | 45 |

|

| Differentiated

degree |

|

|

| 0.871 |

| I +

II | 186 | 97 | 89 |

|

|

III | 77 | 41 | 36 |

|

| T

classification |

|

|

| 0.036b |

| 1 +

2 | 236 | 129 | 107 |

|

| 3 +

4 | 27 | 9 | 18 |

|

| N

classification |

|

|

|

|

| N0 | 149 | 84 | 65 | 0.147 |

| N1 +

N2 | 114 | 54 | 60 |

|

Kaplan-Meier analysis of data from the TCGA database

indicated that patients exhibiting high DDX46 expression

experienced significantly worse OS than those with low DDX46

expression (P=0.039; Fig. 2B).

Further analysis on tissue chips corroborated this finding,

revealing a significant negative association between DDX46

expression and OS in patients with LUAD (P=0.0041; Fig. 2C). Moreover, DDX46 expression was

demonstrated to be a significant independent prognostic factor in

LUAD (Table II). High DDX46

expression was significantly associated with a worse prognosis,

with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.068 in univariate analysis (P=0.004)

and 1.056 in multivariate analysis (P=0.022), underscoring its

prognostic impact even when controlling for other variables.

Although tumor stage was also revealed to be a significant

independent prognostic factor (univariate HR=1.321; P=0.001 and

multivariate HR=1.567; P=0.009), the consistent association of

DDX46 with survival points to its unique role as a potential

standalone prognostic biomarker for LUAD.

| Table II.Univariable and multivariable Cox

regression analyses. |

Table II.

Univariable and multivariable Cox

regression analyses.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathologic

parameter | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 1.017

(1.000–1.035) | 0.055 | 1.017

(0.999–1.035) | 0.062 |

| Stage | 1.321

(1.112–1.563) | 0.001a | 1.567

(1.121–2.191) | 0.009b |

| T

classification | 1.240

(1.043–1.475) | 0.015c | 1.012

(0.813–1.259) | 0.916 |

| N

classification | 1.166

(0.960–1.416) | 0.122 | 0.782

(0.564–1.085) | 0.142 |

| M

classification | 1.139

(0.503–2.580) | 0.754 | 0.528

(0.208–1.338) | 0.178 |

| DDX46

expression | 1.068

(1.02–1.117) | 0.004b | 1.056

(1.008–1.108) | 0.022c |

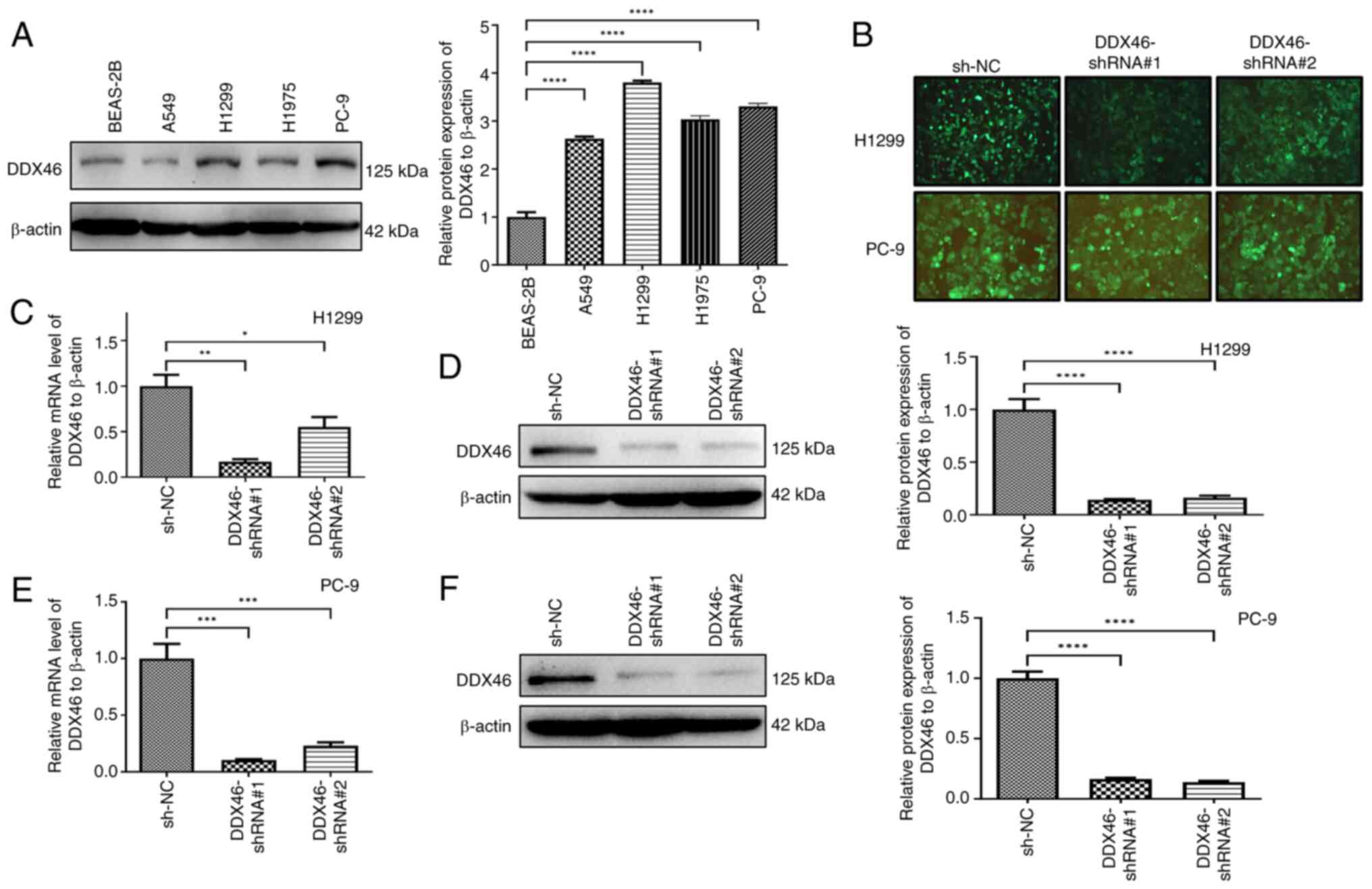

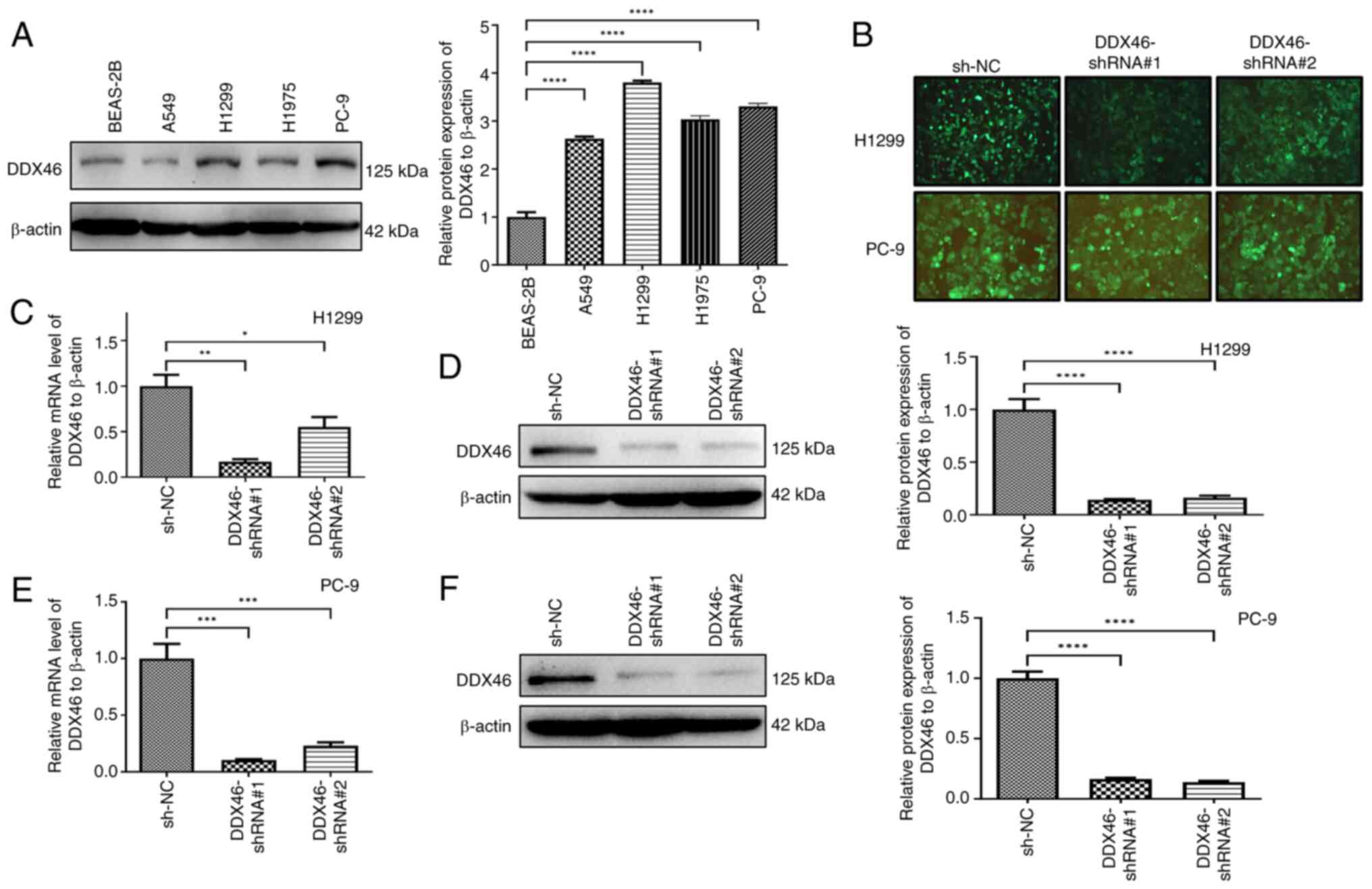

H1299 and PC-9 cells transfected with

lentivirus to knockdown DDX46 expression

Initially, the expression of DDX46 was assessed in

human normal lung epithelial BEAS-2B cells and LUAD cell lines,

including PC-9, H1299, H1975 and A549. DDX46 expression was

demonstrated to be significantly higher in PC-9, H1299, A549 and

H1975 cells compared with that in BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 3A). Based on these findings, H1299

and PC-9 cells were selected for transfection with lentiviral

vectors, including shNC, shDDX46#1 and shDDX46#2, and observation

of the fluorescence signal intensity confirmed successful viral

transfection (Fig. 3B). Subsequent

RT-qPCR and western blot analyses revealed a significant reduction

in DDX46 mRNA and protein levels in H1299 cells, in comparison with

the negative controls (Fig. 3C and

D). Similarly, DDX46 RNA and protein levels were significantly

decreased in PC-9 cells, in comparison with the negative controls

(Fig. 3E and F).

| Figure 3.Expression of DDX46 in several cell

lines and the effect of silencing DDX46 in vitro. (A) DDX46

protein levels in BEAS-2B, A549, H1975, H1299 and PC-9 cell lines.

(B) The knockdown DDX46 lentiviral vector was transfected into

H1299 and PC-9 cells, with the intensity of the green fluorescence

signal serves as an indicator of the efficiency of the

corresponding lentivirus transfection (magnification, ×200). The

effect of silencing DDX46 in H1299 cells was assessed using (C)

RT-qPCR and (D) western blotting, and the effect of silencing DDX46

in PC-9 cells was evaluated using (E) RT-qPCR and (F) western

blotting. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001.

DDX46, DEAD-box 4; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

ns, no significance; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin

RNA. |

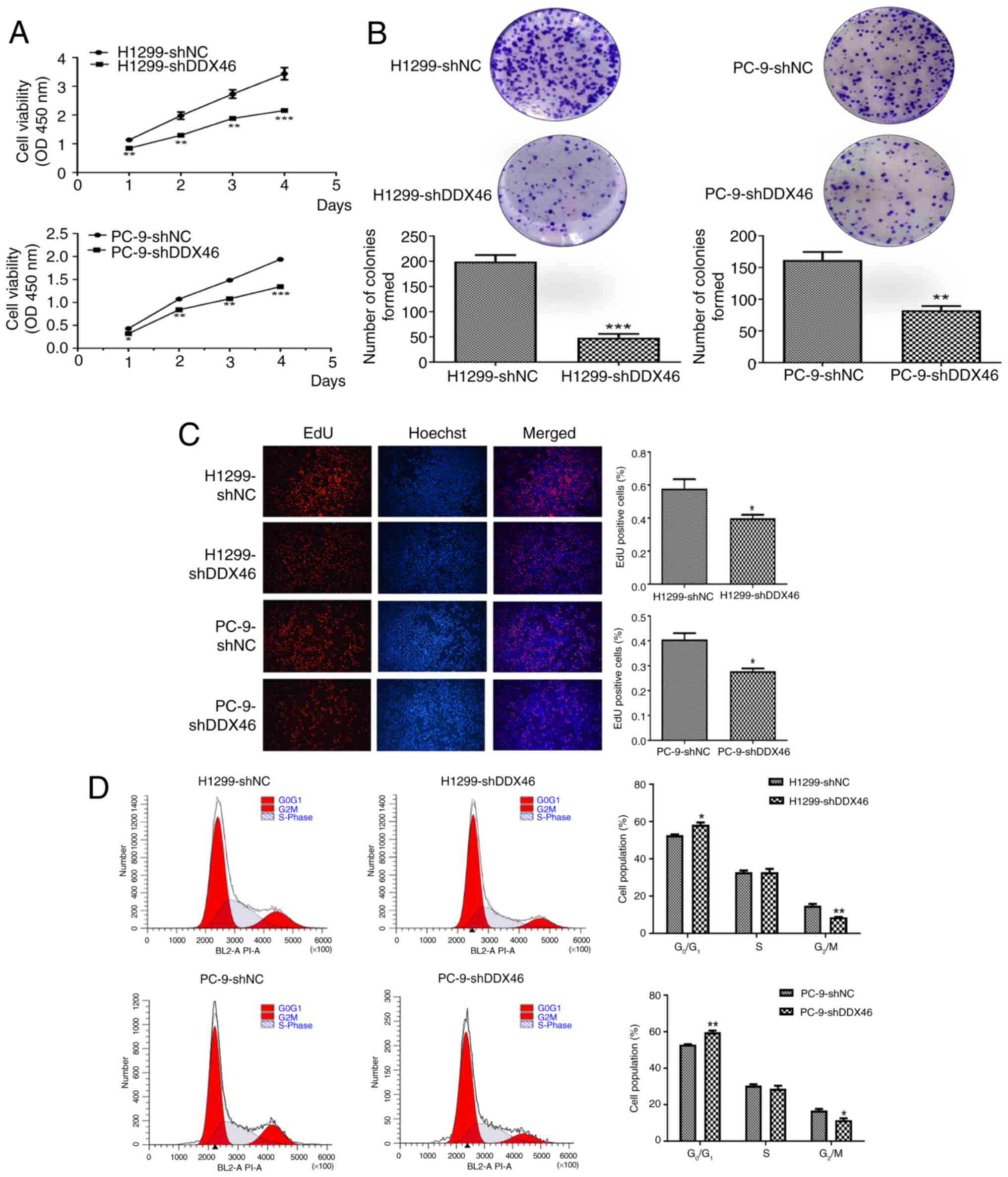

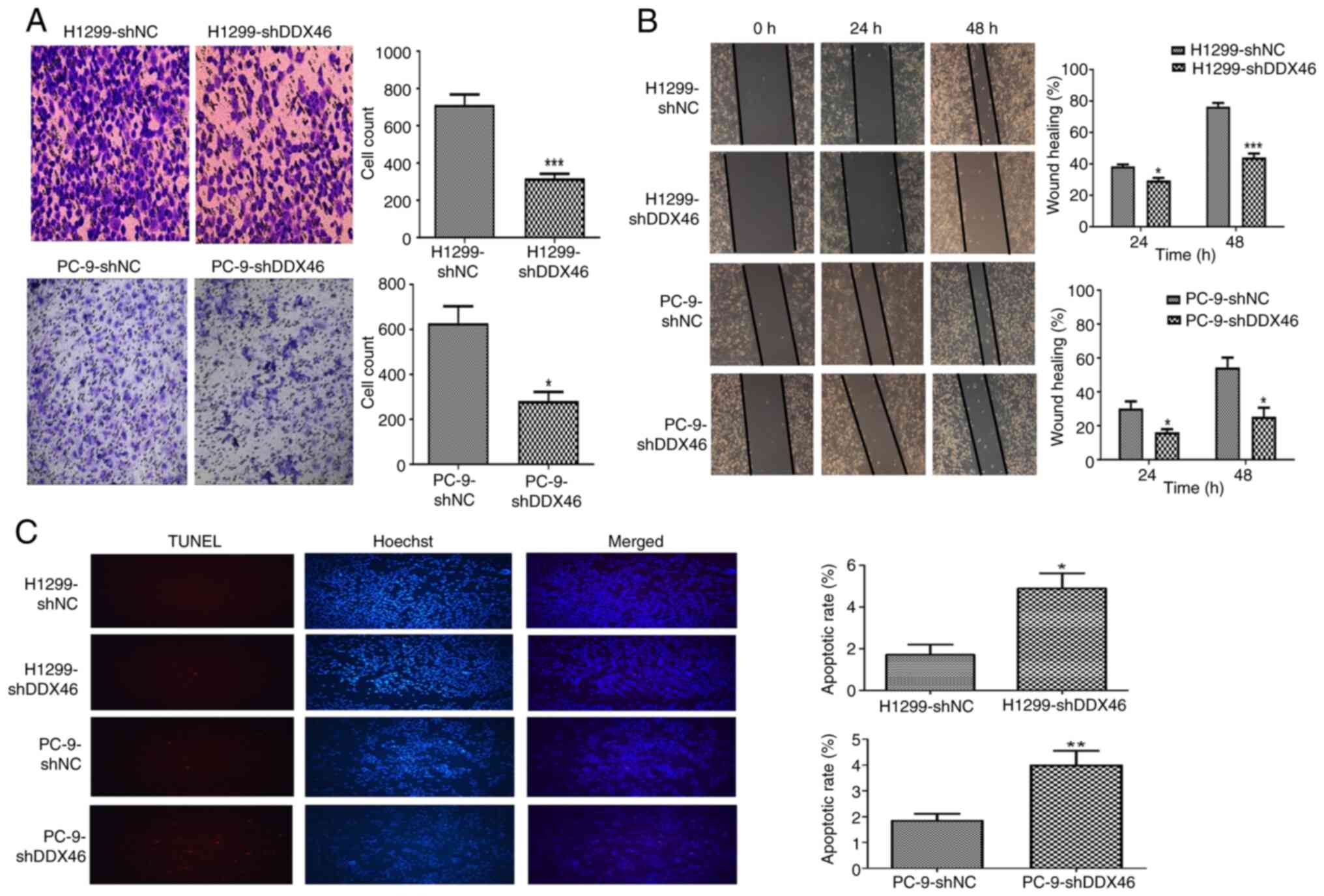

DDX46 knockdown inhibits the

proliferation potential of LUAD cells

CCK-8 assays, colony formation analyses and EdU

experiments indicated a significantly lower proliferation activity

in the shDDX46 group compared with that in the NC group (Fig. 4A-C). Subsequently, flow cytometric

analysis of the cell cycle showed that knocking down the DDX46 gene

led to an increase in the proportion of G0/G1

phase cells and a decrease in G2/M phase cells,

indicating a cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1

phase (Fig. 4D).

Knockdown of DDX46 expression

suppresses the migration of LUAD cells

To assess the role of DDX46 in the migration of LUAD

cells, Transwell and wound healing assays were performed using

H1299 and PC-9 cells. The Transwell assay demonstrated a

significant reduction in the number of both DDX46-knockdown H1299

and PC-9 cells migrating through the polycarbonate membrane,

compared with in the control group (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the wound healing

assay revealed significantly reduced wound closure in H1299 and

PC-9 cells with DDX46 knockdown compared with in the control group

(Fig. 5B). Altogether, these

findings imply that knockdown of DDX46 expression attenuates the

migration of H1299 and PC-9 cells.

Knockdown of DDX46 expression promotes

apoptosis in LUAD cells

TUNEL staining was used to evaluate the impact of

DDX46 knockdown on the apoptosis of LUAD cells. The results

revealed that, relative to the control group, DDX46 knockdown was

associated with a significant increase in the rate of apoptosis in

both H1299 and PC-9 cells (Fig.

5C).

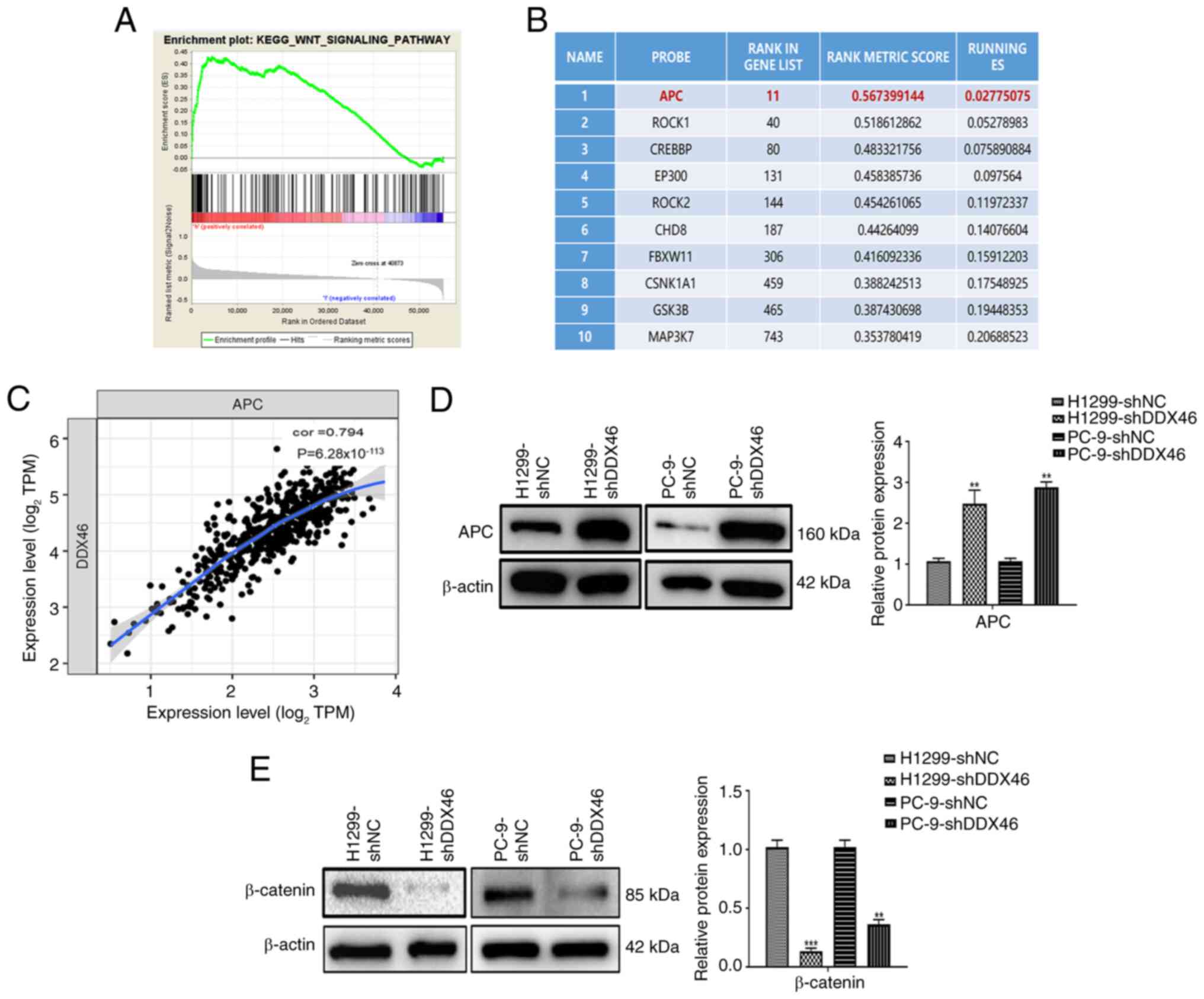

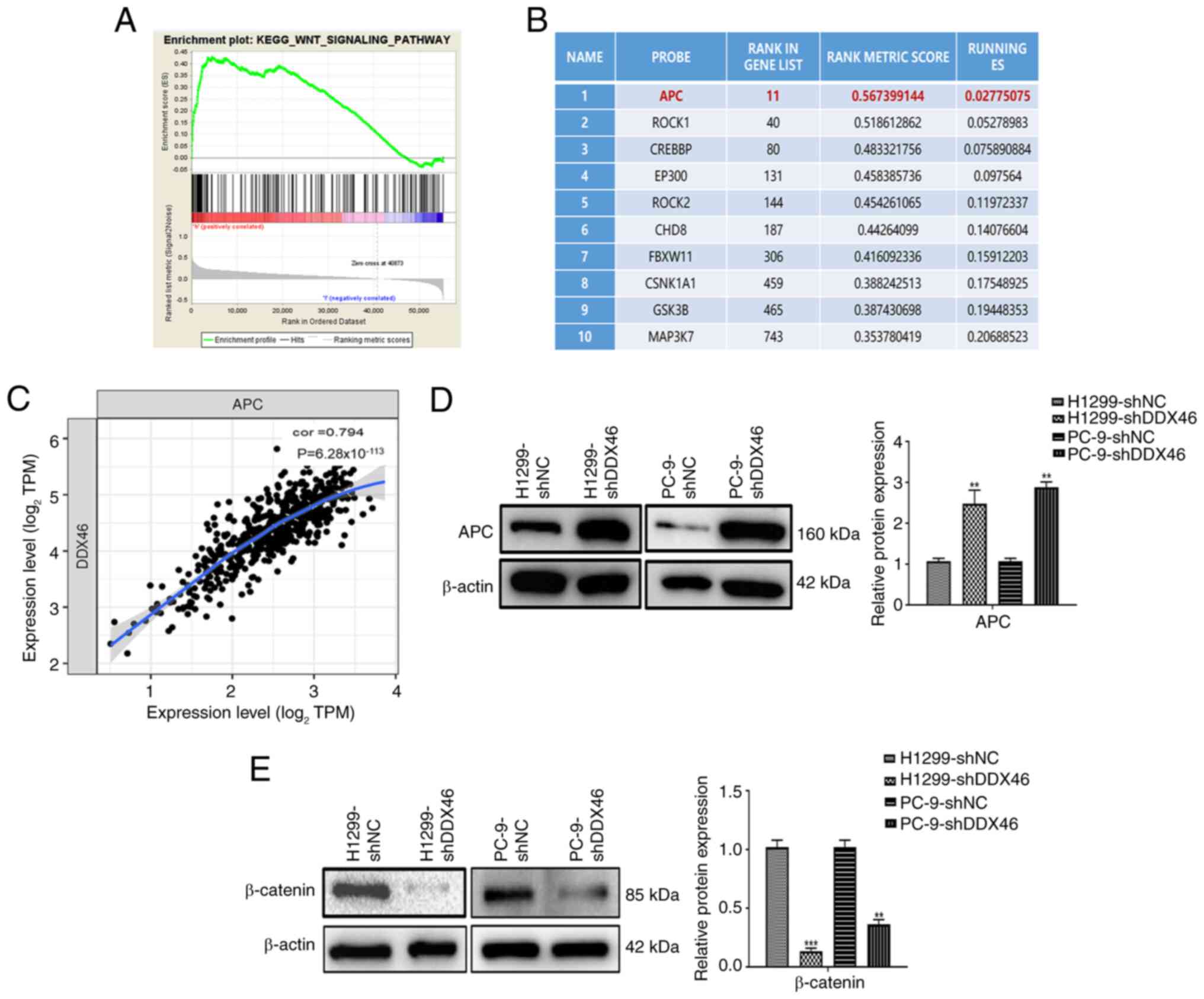

DDX46 regulates the Wnt signaling

pathway in LUAD cells

To further elucidate the potential mechanism of the

DDX46 gene in LUAD samples, TCGA-LUAD data was subjected to GSEA

analysis. In addition, KEGG pathway annotation was performed using

the data (Table SII). The

screening criteria were as follows: P<0.05 and FDR <0.05. The

KEGG analysis results indicate that DDX46 is closely associated

with the Wnt signaling pathway in LUAD (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, a list was compiled

of the top 10 genes enriched in the Wnt signaling pathway by DDX46

(Fig. 6B). The analysis of the

correlation between DDX46 and the top 10 genes in LUAD indicated

that the gene with the strongest correlation was APC, with a

correlation coefficient of 0.794 and a P-value of

6.28×10−113 (Fig. 6C).

Furthermore, through western Blot analysis, it was further

demonstrated that the expression of APC protein significantly

increased whilst the expression of β-catenin protein significantly

decreased in H1299 and PC-9 cells with DDX46 knockdown, in

comparison with control cells (Fig. 6D

and E). These results suggest that DDX46 is closely associated

with the Wnt signaling pathway and may regulate the malignant

progression LUAD through this pathway.

| Figure 6.DDX46 regulates the Wnt signaling

pathway in LUAD cells. (A) DDX46 is closely associated with the Wnt

signaling pathway in LUAD. (B) Top 10 genes enriched in the Wnt

signaling pathway by DDX46. (C) Correlation analysis between DDX46

and APC in LUAD. In (D) H1299 and (E) PC-9 cells, western blot

analysis revealed that APC protein expression increased after

sh-DDX46 treatment, whilst β-catenin protein expression decreased,

in comparison with sh-NC cells. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. DDX46,

DEAD-box 4; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; APC, adenomatous polyposis

coli; sh, short hairpin; NC, negative control; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TPM, transcripts per million;

cor, correlation coefficient; ES, enrichment score. |

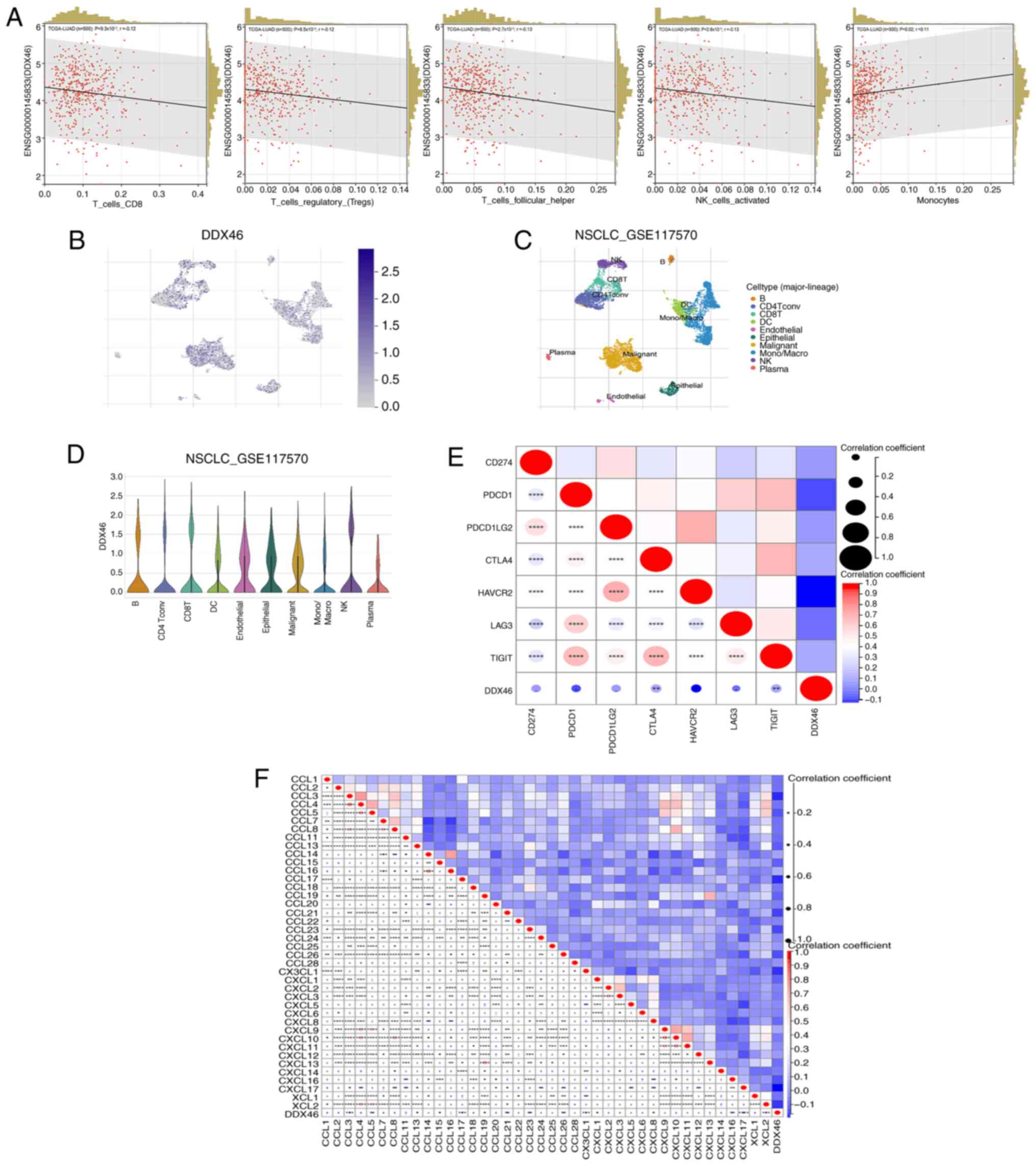

Association of DDX46 expression with

immune infiltration

Analysis of the correlation between DDX46 and 8

major immune cells in LUAD revealed that DDX46 expression is

significantly negatively correlated with CD8 T cells

(P=9.3×10−3; r=−0.12), regulatory T cells

(P=8.5×10−3; r=−0.12), follicular T cells

(P=2.7×10−3; r=−0.13) and natural killer (NK) cells

(P=2.6×10−3; r=−0.12), whilst it is significantly

positively correlated with monocytes (P=0.02; r=0.11) (Fig. 7A). However, no correlation between

the expression of DDX46 and B cells, CD4 T cells or macrophages was

identified (Fig. S1). Furthermore,

the GSE117570 dataset was used to determine the dominant cell types

associated with DDX46 gene expression. The results demonstrated

that the DDX46 gene is highly expressed in T cells, NK cells and

monocyte subsets within the non-small cell LC microenvironment

(Fig. 7B-D). Further correlation

analysis between DDX46 expression and several immune checkpoints

revealed that DDX46 is negatively correlated with cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), Hepatitis A virus

cellular receptor 2 (HAVCR2) and T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and

ITIM domains (TIGIT) (Fig. 7E).

Additionally, the relationship between DDX46 and several chemokines

was analyzed. DDX46 was correlated with the expression of several

chemokines, including CCL3, CCL5, CCL13, CCL15, CCL17, CCL19,

CCL21, CCL23, CCL26, CX3CL1, CXCL1, CXCL8, CXCL16, CXCL17 and XCL2

(Fig. 7F). The correlation data

between DDX46 and immune checkpoints and chemokines is presented in

Tables SIII and SIV.

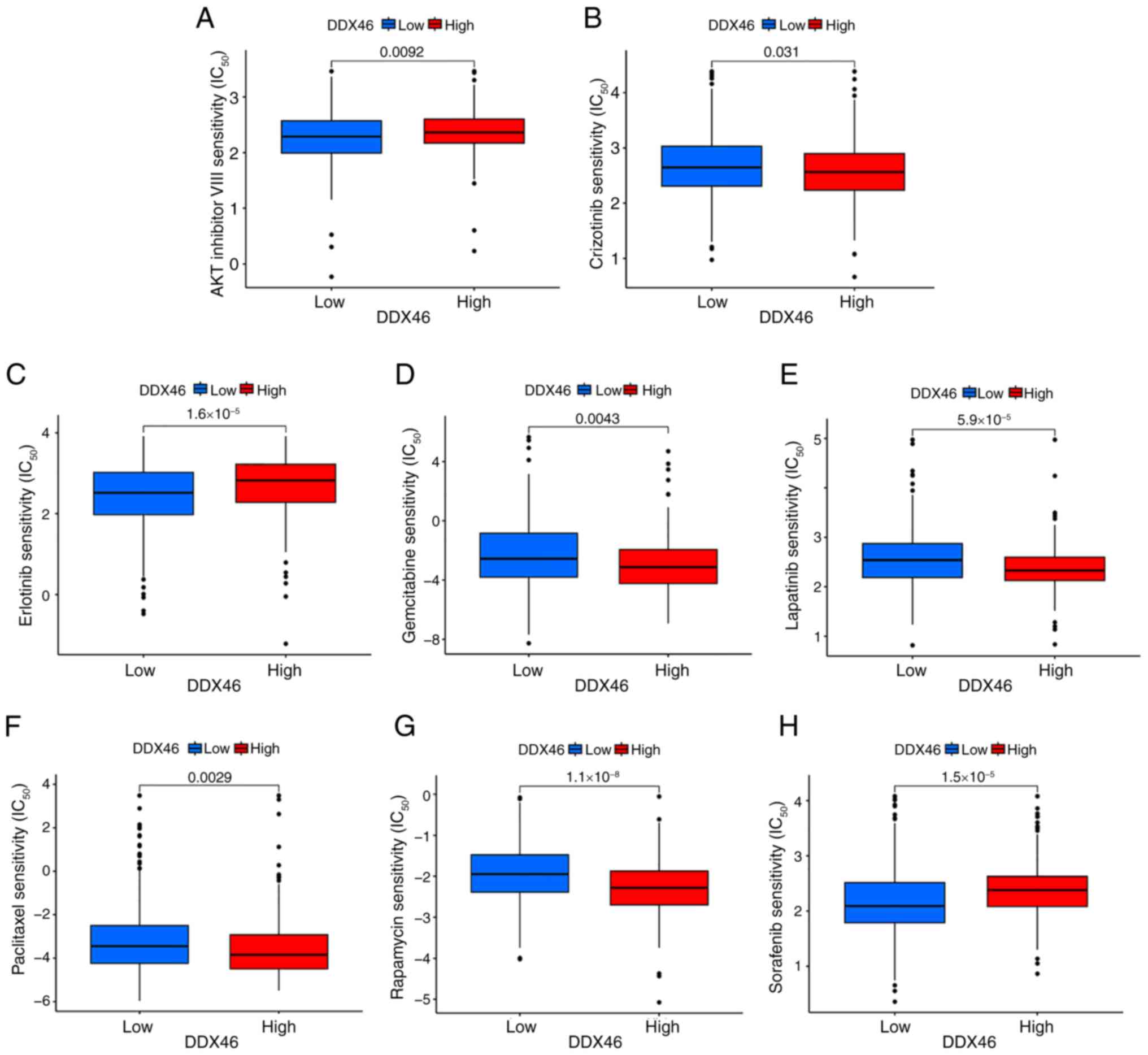

Analysis of DDX46 drug

susceptibility

The association between DDX46 gene expression and

the IC50 of commonly administered drugs in LUAD was

assessed to ascertain whether the DDX46 gene is suitable for the

personalized treatment of patients with LUAD. These commonly used

drugs for LUAD treatment include AKT inhibitors, paclitaxel,

crizotinib, erlotinib, gemcitabine, lapatinib, rapamycin and

sorafenib. The findings revealed that patients with LUAD with low

DDX46 expression demonstrated significantly increased sensitivity

to some drugs (crizotinib, gemcitabine, lapatinib, paclitaxel and

rapamycin), in comparison with those with high DDX46 expression.

However, high expression of DDX46 may be associated with increased

sensitivity to treatment with AKT inhibitors, erlotinib and

sorafenib, potentially due to its impact on key cellular survival

and proliferation pathways (Fig.

8).

Discussion

The oncogenic role of DDX46 has been reported in

several malignancies, including gastric cancer, colorectal cancer,

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and breast cancer (13,24,25).

However, the specific biological function of DDX46 in LUAD

progression and its relationship with immune infiltration and drug

sensitivity remain poorly understood. The results of the present

study demonstrated a significant upregulation of DDX46 in LUAD,

which was associated with a poor prognosis. In LUAD cells, aberrant

expression of DDX46 affected cell proliferation, invasion and

migration. Bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation

suggested that DDX46 may regulate the Wnt signaling pathway.

Additionally, further bioinformatics analysis revealed that DDX46

is strongly linked to immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoints,

chemokines and drug sensitivity.

Research has shown that the overexpression of DDX46

in human breast cancer is related to elevated histological grade

and lymph node metastasis (25). In

a parallel study on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a notable

elevation in DDX46 expression was observed in both cancer cells and

tissues (13). Additionally,

colorectal cancer tissues have been reported to exhibit heightened

focal nuclear DDX46 staining compared with adjacent normal tissues

(24). Admoni-Elisha et al

(26) reported an association

correlation elevated DDX46 expression in patients with chronic

lymphocytic leukemia and reduced OS. In the present research, the

high expression of DDX46 in both LUAD tissues and cell lines was

initially demonstrated, revealing its association with a poor

prognosis. The findings suggest that DDX46 could serve as a

valuable biomarker for stratifying patients with LUAD based on

risk. By identifying patients with high DDX46 expression,

clinicians could improve the prediction of those at higher risk of

disease progression and poor outcomes. Functionally, abnormal

expression of DDX46 contributes to enhanced proliferation,

migration, invasion and suppressed apoptosis of esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer cells and cutaneous squamous cell

carcinoma in vitro and in vivo experiments (27). Additionally, in A549 cells, the

interaction between structural maintenance of chromosomes 4 and the

DDX46 gene was reported to impede cell M-phase progression, thereby

inhibiting cell proliferation and invasion (28). The findings of the study align with

the documented role of DDX46 in enhancing tumor cell proliferation,

invasion and migration.

Prior research has reported that DDX46 influences

the proliferation and migration of glioblastoma, gastric cancer and

preeclampsia through the MAPK-p38, Akt/glycogen synthase

kinase-3β/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways (15,29,30).

In the mechanism, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that

DDX46 is strongly associated with the Wnt signaling pathway in

LUAD. Correlation analysis also revealed that DDX46 has a high

correlation coefficient with APC, in LUAD, reaching 0.794 with a

P-value of 6.28×10−113. APC serves a critical

suppressive role in the Wnt signaling pathway, and the interaction

between APC and β-catenin is crucial for cell signaling,

proliferation and fate determination. In cancer development,

mutations in APC lead to the abnormal activation of β-catenin, a

process that serves a critical role in tumorigenesis (31–34).

In the present study, western blot analysis further demonstrated

that, in H1299 and PC-9 cells with DDX46 knockdown, the expression

of APC protein increased whilst the expression of β-catenin protein

decreased. These findings offer fresh perspectives into the

downstream regulatory mechanisms of DDX46 in tumor progression.

The present study revealed a strong association

between DDX46 and diverse immune cells, immune checkpoints and

chemokines. Immune cells and chemokines within the tumor immune

microenvironment are pivotal in the pathogenesis of diverse tumors

(35), with the degree of immune

cell infiltration markedly impacting the prognosis of patients with

solid tumors (36,37). Research has also reported that

chemokines are involved in the circulation, homing, retention and

activation of immune active cells (38,39).

Notably, the findings of the present study indicate an inverse

relationship between DDX46 expression and T cells, NK cells and

immune checkpoints, CTLA4, HAVCR2 and TIGIT, suggesting a potential

role for DDX46 in immune evasion. This mechanism could contribute

to the progression of LUAD.

In the analysis of drug sensitivity associated with

DDX46, it was revealed that DDX46 expression is associated with the

sensitivity of cancer cells to several drugs, including AKT

inhibitors, paclitaxel, crizotinib, erlotinib, gemcitabine,

lapatinib, rapamycin and sorafenib. Numerous studies have reported

that the DDX helicase family proteins, in addition to their

critical roles in RNA biology, can stimulate and bind to several

protein kinases (40). This

provides a theoretical basis for the influence of DDX46 expression

on the sensitivity to multiple protein kinase inhibitors. AKT

inhibitors are a class of targeted antitumor drugs that inhibit the

AKT protein kinase (41). Previous

studies have reported that knockdown of DDX46 can notably reduce

the phosphorylation levels of AKT, thereby decreasing its kinase

activity (14,15). Erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase

inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),

inhibits tumor cell proliferation, survival and migration by

blocking EGFR signaling pathways such as the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways (42). A

study on preeclampsia also revealed that suppressing DDX46 inhibits

trophoblast proliferation and migration through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway (30).

Furthermore, a study on human colorectal cancer reported that the

expression of DDX46 is associated with the apoptosis of tumor cells

(24). One of the mechanisms of

action of sorafenib is its ability to reduce the expression of

anti-apoptotic proteins through multiple pathways, thereby

promoting apoptosis (43). In

summary, the impact of DDX46 expression on drug sensitivity or

resistance in cancer cells is multifaceted, depending on the

interplay between the mechanism of action of each drug and the

cellular processes regulated by DDX46.

However, the present study has certain limitations.

Although bioinformatics provides valuable insights and preliminary

correlations, there is a lack of experimental validation to clarify

the association between DDX46 and the Wnt signaling pathway.

Similarly, the absence of in vivo experiments limits the

ability to confirm the biological and mechanistic roles of DDX46 in

LUAD. Future research should incorporate experiments targeting the

Wnt signaling pathway and utilize animal models to validate the

role of DDX46, establishing causal relationships with LUAD

progression and immune regulation.

In conclusion, elevated DDX46 levels in patients

LUAD may serve as a strong prognostic indicator and assist in

diagnosis. Furthermore, high DDX46 expression promotes cell

proliferation and survival in LUAD, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target for diagnosis and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82273422), the Nantong Basic

Research Plan Project (grant no. MS2023067), the 2022 Nantong Basic

Science Research and Social Livelihood Science and Technology Plan

Project (grant no. MS22022111), the Research Project on

Cutting-Edge Tumor Support Therapy (grant no. cphcf-2022-206), the

Jiangsu Provincial Research Hospital (grant nos. YJXYY202204-YSC01

and YJXYY202204-YSB01) and the Key Project of Nantong's 14th Five

Year Plan Science and Education Strengthening Health Project,

Oncology Clinical Medical Center (grant no. NTYXZX18).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TB and MZ designed the study; TW, QZ and JZ

performed the experiments; TW analyzed the data; TB and MZ wrote

the paper and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data; YL and

WS designed the work, drafted the manuscript and contributed to its

revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University

(approval no. 2022-L078). The data were anonymous and the

requirement for informed consent was waived.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DDX46

|

DEAD-box 46

|

|

LC

|

lung cancer

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

TISCH

|

Tumor Immune Single Cell Hub

|

|

TIICs

|

tumor-infiltrating immune cells

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

GSEA

|

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

APC

|

adenomatous polyposis coli

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

References

|

1

|

Collisson EA, Campbell JD, Brooks AN,

Berger AH, Lee W, Chmielecki J, Beer DG, Cope L, Creighton CJ,

Danilova L, et al: Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung

adenocarcinoma: The cancer genome atlas research network. Nature.

511:543–550. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chen P, Liu Y, Wen Y and Zhou C: Non-small

cell lung cancer in China. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:937–970. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zulfiqar B, Farooq A, Kanwal S and Asghar

K: Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for lung cancer: Current

status and future perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 13:10351712022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D and Boshoff C:

The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature.

553:446–454. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Denisenko TV, Budkevich IN and Zhivotovsky

B: Cell death-based treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death

Dis. 9:1172018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hooper C and Hilliker A: Packing them up

and dusting them off: RNA helicases and mRNA storage. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1829:824–834. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Linder P and Jankowsky E: From unwinding

to clamping-the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 12:505–516. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Owttrim GW: RNA helicases: Diverse roles

in prokaryotic response to abiotic stress. RNA Biol. 10:96–110.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Robert F and Pelletier J: Perturbations of

RNA helicases in cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 4:333–349.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Steimer L and Klostermeier D: RNA

helicases in infection and disease. RNA Biol. 9:751–771. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Abdelhaleem M, Maltais L and Wain H: The

human DDX and DHX gene families of putative RNA helicases.

Genomics. 81:618–622. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Will CL, Urlaub H, Achsel T, Gentzel M,

Wilm M and Lührmann R: Characterization of novel SF3b and 17S U2

snRNP proteins, including a human Prp5p homologue and an SF3b

DEAD-box protein. EMBO J. 21:4978–4988. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li B, Li YM, He WT, Chen H, Zhu HW, Liu T,

Zhang JH, Song TN and Zhou YL: Knockdown of DDX46 inhibits

proliferation and induces apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 36:223–230. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jiang F, Zhang D, Li G and Wang X:

Knockdown of DDX46 inhibits the invasion and tumorigenesis in

osteosarcoma cells. Oncol Res. 25:417–25. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen L, Xu M, Zhong W, Hu Y and Wang G:

Knockdown of DDX46 suppresses the proliferation and invasion of

gastric cancer through inactivating Akt/GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway.

Exp Cell Res. 399:1124482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang Z, Jensen MA and Zenklusen JC: A

practical guide to the cancer genome atlas (TCGA). Methods Mol

Biol. 1418:111–141. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zheng M, Liu J, Bian T, Liu L, Sun H, Zhou

H, Zhao C, Yang Z, Shi J and Liu Y: Correlation between prognostic

indicator AHNAK2 and immune infiltrates in lung adenocarcinoma. Int

Immunopharmacol. 90:1071342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sun D, Wang J, Han Y, Dong X, Ge J, Zheng

R, Shi X, Wang B, Li Z, Ren P, et al: TISCH: A comprehensive web

resource enabling interactive single-cell transcriptome

visualization of tumor microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(D1):

D1420–D1430. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lei Y, Zhou B, Meng X, Liang M, Song W,

Liang Y, Gao Y and Wang M: A risk score model based on lipid

metabolism-related genes could predict response to immunotherapy

and prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma: A multi-dataset study and

cytological validation. Discov Oncol. 14:1882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ru B, Wong CN, Tong Y, Zhong JY, Zhong

SSW, Wu WC, Chu KC, Wong CY, Lau CY, Chen I, et al: TISIDB: An

integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions.

Bioinformatics. 35:4200–4202. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Komuro H, Shinohara S, Fukushima Y,

Demachi-Okamura A, Muraoka D, Masago K, Matsui T, Sugita Y,

Takahashi Y, Nishida R, et al: Single-cell sequencing on

CD8+ TILs revealed the nature of exhausted T cells

recognizing neoantigen and cancer/testis antigen in non-small cell

lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0071802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ,

Lightfoot H, Forbes S, Bindal N, Beare D, Smith JA, Thompson IR, et

al: Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC): A resource for

therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res.

41((Database Issue)): D955–D961. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li M, Ma Y, Huang P, Du A, Yang X, Zhang

S, Xing C, Liu F and Cao J: Lentiviral DDX46 knockdown inhibits

growth and induces apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells.

Gene. 560:237–244. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ma Z, Song J, Hua Y, Wang Y, Cao W, Wang H

and Hou L: The role of DDX46 in breast cancer proliferation and

invasiveness: A potential therapeutic target. Cell Biol Int.

47:283–291. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Admoni-Elisha L, Nakdimon I, Shteinfer A,

Prezma T, Arif T, Arbel N, Melkov A, Zelichov O, Levi I and

Shoshan-Barmatz V: Novel biomarker proteins in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia: Impact on diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. PLoS One.

11:e01485002016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lin Q, Jin HJ, Zhang D and Gao L: DDX46

silencing inhibits cell proliferation by activating apoptosis and

autophagy in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Med Rep.

22:4236–4242. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang C, Kuang M, Li M, Feng L, Zhang K

and Cheng S: SMC4, which is essentially involved in lung

development, is associated with lung adenocarcinoma progression.

Sci Rep. 6:345082016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ma J, Gao Z and Liu X: DDX46 accelerates

the proliferation of glioblastoma by activating the MAPK-p38

signaling. J BUON. 26:2084–2089. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

You X, Cui H, Yu N and Li Q: Knockdown of

DDX46 inhibits trophoblast cell proliferation and migration through

the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in preeclampsia. Open Life Sci.

15:400–408. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Disoma C, Zhou Y, Li S, Peng J and Xia Z:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer: Is therapeutic

targeting even possible? Biochimie. 195:39–53. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wan C, Mahara S, Sun C, Doan A, Chua HK,

Xu D, Bian J, Li Y, Zhu D, Sooraj D, et al: Genome-scale

CRISPR-Cas9 screen of Wnt/β-catenin signaling identifies

therapeutic targets for colorectal cancer. Sci Adv. 7:eabf25672021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhan T, Rindtorff N and Boutros M: Wnt

signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 36:1461–1473. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hankey W, Frankel WL and Groden J:

Functions of the APC tumor suppressor protein dependent and

independent of canonical WNT signaling: Implications for

therapeutic targeting. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 37:159–172. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Bai R, Yin P, Xing Z, Wu S, Zhang W, Ma X,

Gan X, Liang Y, Zang Q, Lei H, et al: Investigation of GPR143 as a

promising novel marker for the progression of skin cutaneous

melanoma through bioinformatic analyses and cell experiments.

Apoptosis. 29:372–392. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, Iwasaki

M, Kosuge T, Kanai Y and Hiraoka N: Immune cell infiltration as an

indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br J

Cancer. 108:914–923. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Schneider K, Marbaix E, Bouzin C, Hamoir

M, Mahy P, Bol V and Gregoire V: Immune cell infiltration in head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma and patient outcome: A

retrospective study. Acta Oncol. 57:1165–1172. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Franciszkiewicz K, Boissonnas A, Boutet M,

Combadiere C and Mami-Chouaib F: Role of chemokines and chemokine

receptors in shaping the effector phase of the antitumor immune

response. Cancer Res. 72:6325–6332. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Koizumi K, Hojo S, Akashi T, Yasumoto K

and Saiki I: Chemokine receptors in cancer metastasis and cancer

cell-derived chemokines in host immune response. Cancer Sci.

98:1652–1658. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hirth A, Fatti E, Netz E, Acebron SP,

Papageorgiou D, Švorinić A, Cruciat CM, Karaulanov E, Gopanenko A,

Zhu T, et al: DEAD box RNA helicases are pervasive protein kinase

interactors and activators. Genome Res. 34:952–966. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shariati M and Meric-Bernstam F: Targeting

AKT for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 28:977–988.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wu SG and Shih JY: Management of acquired

resistance to EGFR TKI-targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell

lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 17:382018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wu CH, Lin KH, Fu BS, Hsu FT, Tsai JJ,

Weng MC and Pan PJ: Sorafenib induces apoptosis and inhibits

NF-κB-mediated anti-apoptotic and metastatic potential in

osteosarcoma cells. Anticancer Res. 41:1251–1259. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|