Introduction

Liposarcoma is a rare malignant tumor originating

from adipocytes, accounting for 15–20% of soft tissue sarcomas

(1). The differences among its

subtypes primarily depend on immunohistochemical characteristics,

cell morphology, and genetic variations. According to the 2020

World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone

Tumors (2), liposarcoma can be

divided into well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipomatous

tumor), dedifferentiated liposarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma,

pleomorphic liposarcoma, and myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma, with

well-differentiated liposarcoma being the most common type. Each

subtype exhibits significant differences in clinical presentation,

biological characteristics, and drug sensitivity (3,4).

Esophageal liposarcomas are exceedingly rare, constituting only

1.2–1.5% of gastrointestinal liposarcomas (5). Studies indicate that minimally

invasive procedures, such as transoral and thoracoscopic

techniques, are the preferred surgical methods for treating

esophageal liposarcomas. However, challenges such as risk of

bleeding and high recurrence rates remain for complex giant

esophageal liposarcomas (6,7). Surgical resection is essential for

managing giant, well-differentiated liposarcomas of the esophagus;

however, no standardized protocol exists for selecting the surgical

approach.

Given the rarity of esophageal liposarcomas and the

complexity of their treatment, evaluating the effectiveness of

different surgical methods holds clinical significance. By

discussing the surgical approaches for two cases of giant,

well-differentiated esophageal liposarcoma, through

multidisciplinary collaboration, leveraging the strengths of both

endoscopic techniques and surgical interventions, complete tumor

excision was achieved and both patients demonstrated favorable

postoperative recovery. This article aims to provide additional

treatment options and shared experiences to enhance patient

prognosis and quality of life.

Case report

Both patients were admitted due to dysphagia.

Patient 1 was a 62-year-old male who reported ‘dysphagia for 1

month, which worsened 1 week previously’. One month prior to

admission to an external Hospital in May 2024, the patient

underwent laryngoscopy and was diagnosed with pharyngitis. The

condition showed slight improvement following anti-inflammatory

treatment. However, 1 week before admission to the Affiliated

Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (Guiyang, China) in June

2024, the patient's dysphagia worsened, accompanied by difficulty

eating. Of note, the patient was able to expel the tumor from the

esophagus through the mouth and swallow it back into the body. The

patient had a history of varicose vein surgery in both lower limbs

and a 10-year smoking history (20 cigarettes per day, quit 1 month

ago). Upon admission, physical examination revealed a mass in the

esophagus that could partially be vomited out. Chest computed

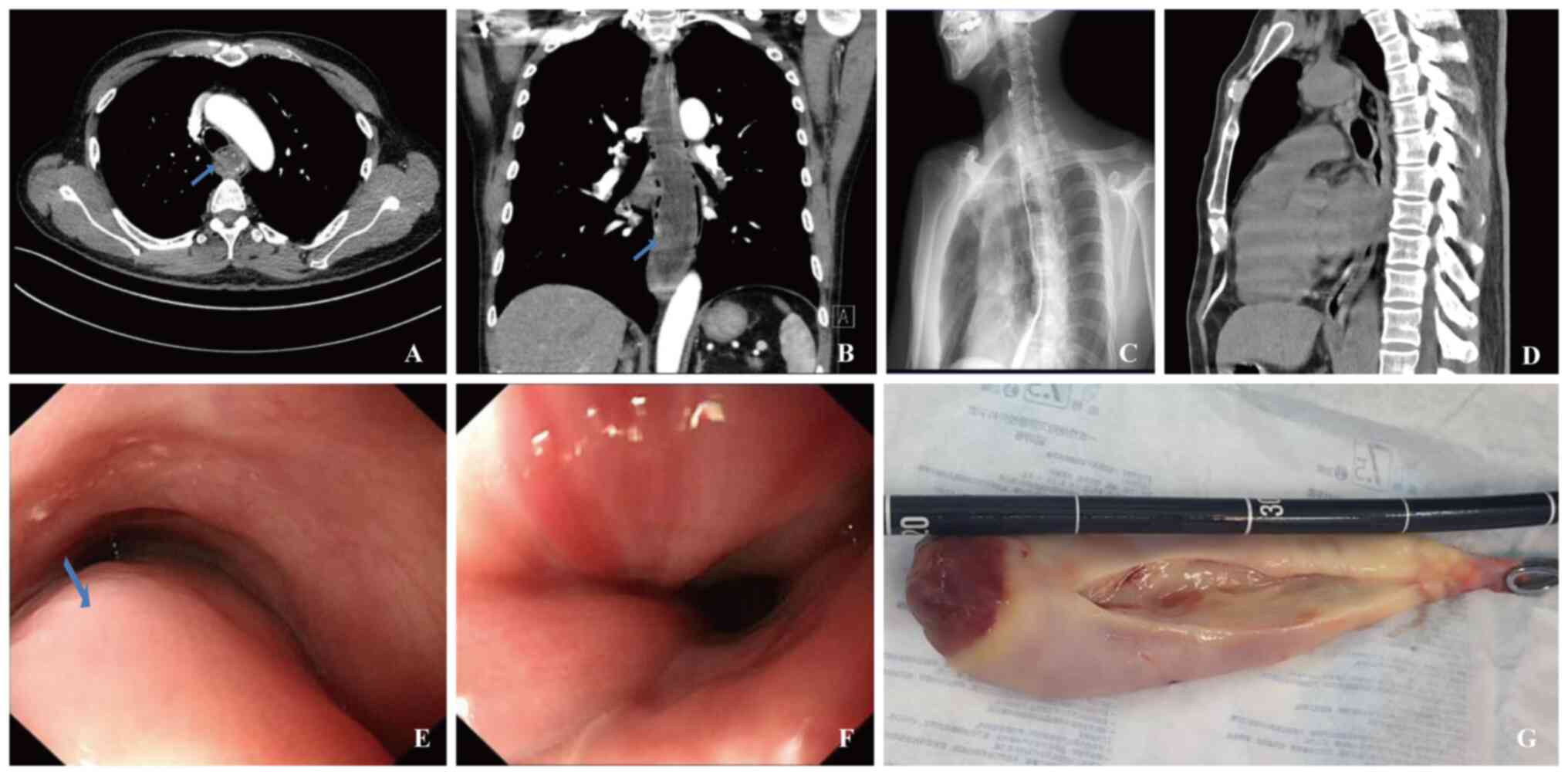

tomography (CT; Fig. 1A and B)

revealed esophageal dilation, with a mass-like lesion exhibiting

increased cystic density and no obvious enhancement on the

enhancement scan. The area near the gastroesophageal junction

displayed uneven enhancement, with no fat density components

observed. The esophageal tumor measured ~23 cm in length, with its

base located in the upper segment of the esophagus, parallel to the

level of the T1 vertebra. In addition, multiple lymph node

calcifications were visible in both lung hila and the mediastinum.

Gastroscopy revealed a giant submucosal lesion with expanded blood

vessels and inflammatory exudate (Fig.

1E and F).

Patient 2 was a 41-year-old male who presented to

the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (Guiyang,

China) in August 2024 due to ‘dysphagia and recurrent fever for 1

month’. The patient experienced swallowing discomfort of unknown

causes, with a maximum body temperature of 38.8°C. Self-medication

with anti-inflammatory drugs provided no significant improvement

and the patient had lost 4 kg in weight over the past month. The

patient had a 20-year smoking history (20 cigarettes per day) and

occasionally consumed alcohol, with no other significant health

issues. Physical examination revealed no remarkable findings.

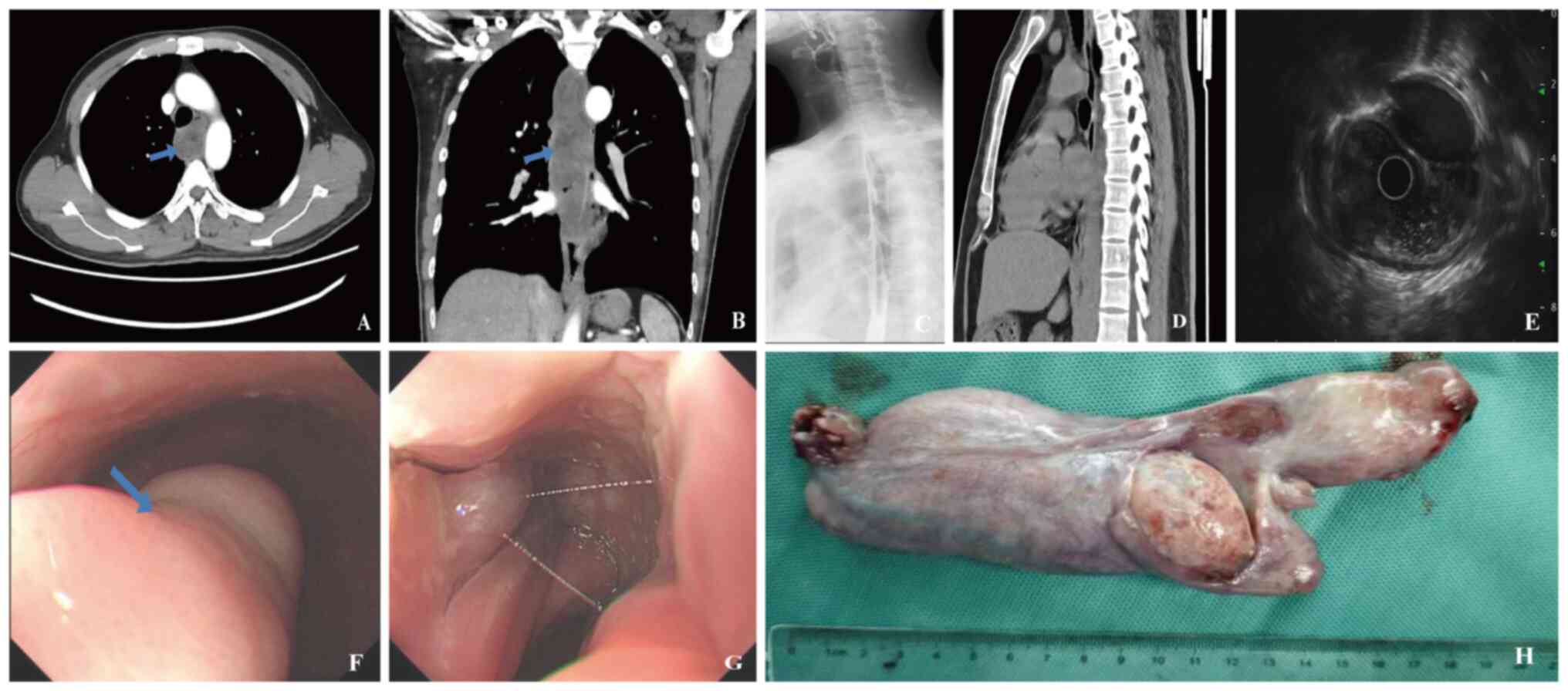

Enhanced chest CT (Fig. 2A and B)

revealed a large strip-like lesion in the esophagus, exhibiting

mixed density comprising both solid and fatty components. The

lesion measured 3.1×6.1×20.2 cm. The mediastinal lymph nodes

appeared normal and the CT also demonstrated prominent vessels

surrounding the tumor. Endoscopic examination (Fig. 2F and G) provided a more direct and

clearer view, revealing a strip-like elevation from the upper

segment of the esophagus (16 cm from the incisors) to the lower

segment (35 cm from the incisors). The upper segment lesion showed

congestion and superficial ulceration, with localized gray-blue

blood vessels. Endoscopic ultrasound examination indicated that the

elevation originated from the third layer and presented as a mixed

echogenic mass (Fig. 2E). In order

to clarify the diagnosis before surgery, two patients underwent a

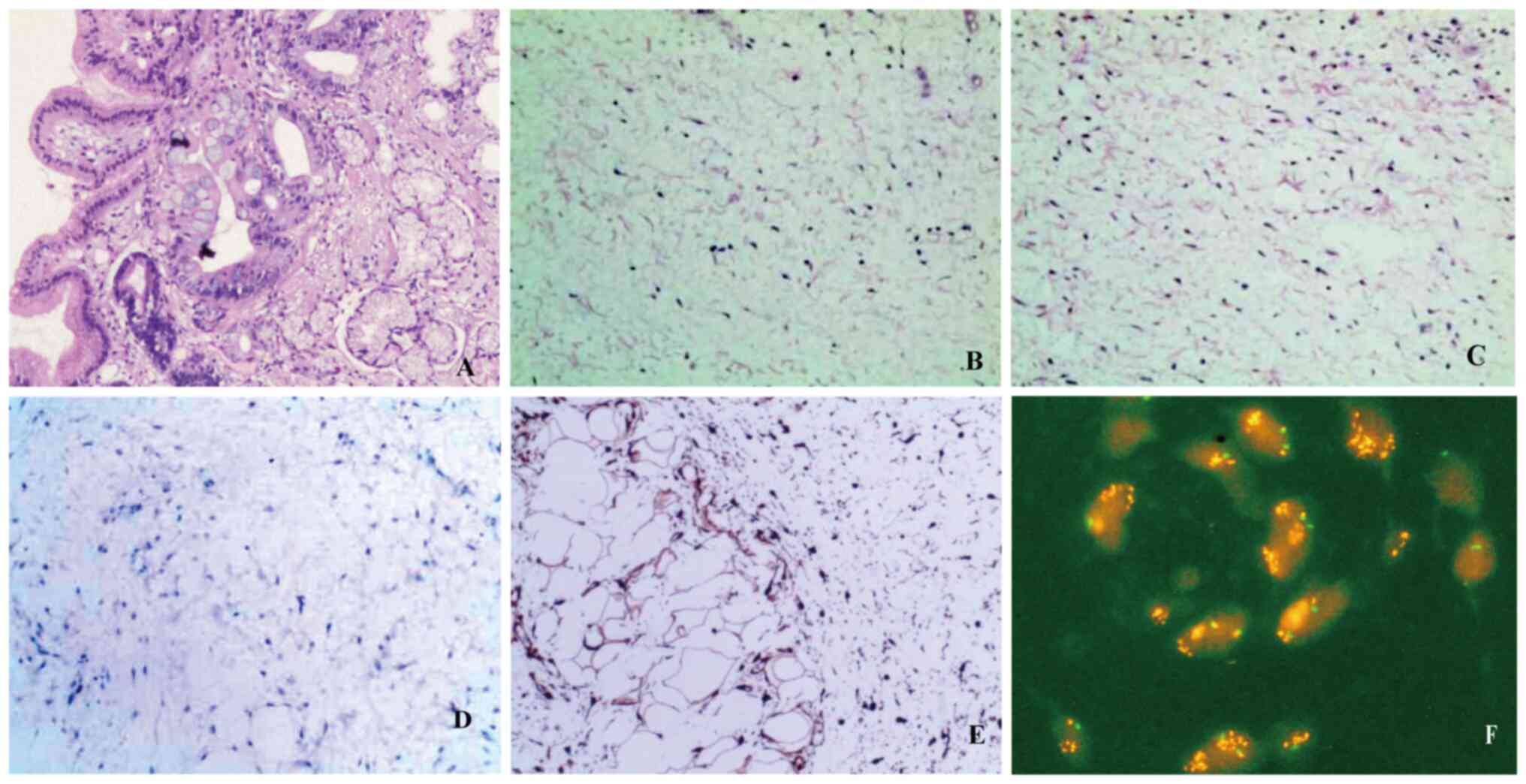

biopsy. The biopsy results of Patient 1 showed inflammatory exudate

and necrosis (Fig. 3A); the biopsy

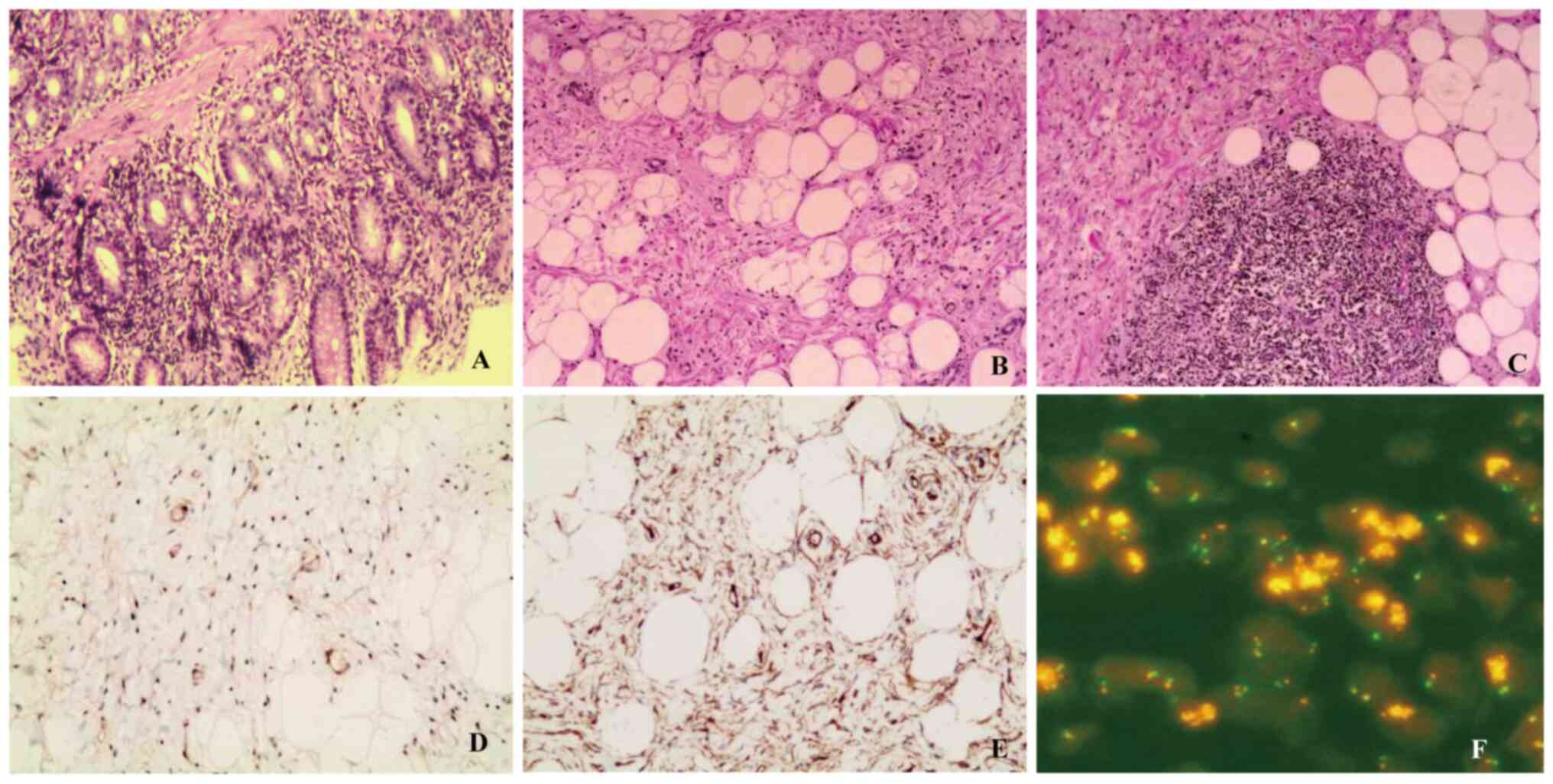

results of Patient 2 exhibited moderate chronic inflammation,

erosion, and lymphoid tissue hyperplasia forming follicles

(Fig. 4A). Both were initially

diagnosed as benign esophageal tumors.

In the surgical management, both patients were

considered to have benign esophageal tumors located in the mucosal

layer. After discussions among experts from the endoscopy center

and thoracic surgery, endoscopic tumor removal was prioritized. In

case the endoscopic procedure could not be completed, the thoracic

surgery team was prepared to perform open resection via a cervical

approach. Both patients ultimately underwent endoscopic tumor

removal. Patient 1 underwent surgery on the third day after

admission, during which a large, strap-like lesion was found on the

left esophageal wall, ~38 cm from the incisors, occupying about

two-thirds of the esophagus. The tumor measured 22×4×4 cm (Fig. 1G) and was successfully removed

endoscopically. Patient 2 underwent surgery on the fifth day after

admission, during which a giant sessile tumor was found, extending

16 to 36 cm from the incisors, with its base located in the neck,

lobulated and occupying two-thirds of the esophagus. The tumor

measured 20×6×3 cm (Fig. 2H) and

exhibited a soft consistency, with two prominent blood vessels

(~0.4 cm in diameter) visible on the surface.

Both procedures followed a similar approach.

Attempts to use a snare and harmonic scalpel were unsuccessful, so

hemostatic forceps were employed to coagulate visible blood vessels

at the tumor's base. The lesion was dissected using a disposable

endoscopic scalpel starting from the mucosa and extending to the

submucosal layer, revealing white fibrous tissue and large blood

vessels. After electrocautery, the tumor was carefully extracted

until significant resistance was encountered at the entrance of the

esophagus; repeated attempts to change angles only resulted in

partial tumor extraction, prompting the use of oval and tongue

forceps to drag the tumor out of the oral cavity. Postoperative

pathology confirmed well-differentiated liposarcoma of the

esophagus. In Patient 1, the esophageal lesion presented as a

mucosal ulcer, with spindle-like cells and vascular proliferation

observed beneath the ulcer, and certain areas showing mucinous

degeneration (Fig. 3B and C).

Immunohistochemical results showed negative Cytokeratin (CK), with

positive Vimentin (Vim), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (P16;

Fig. 3E), CDK4 and CD34 and

negative mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2; Fig. 3D), SRY-box transcription factor 10

(Sox10), desmin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), caldesmon, melanocyte

antigen (Melan-A), human melanoma black 45 (HMB45), CD117 and

discovered on GIST-1 (DOG-1); Ki-67 antigen (Ki-67) was ~3%

positive. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

(Fig. 3F) analysis indicated

positive amplification of the MDM2 gene (12q15). In Patient

2, there was significant proliferation of fibrofatty tissue in the

submucosal layer of the esophageal lesion, forming fat lobules of

varying sizes, accompanied by thick-walled blood vessels and focal

lymphoid tissue hyperplasia (Fig. 4B

and C). Immunohistochemical results showed atypical cells

positive for Vim, S100, CD34, desmin, P16 (Fig. 4E), MDM2 (Fig. 4D) and CDK4 and negative for SMA,

caldesmon, DOG-1 and CD117; and Ki-67 was ~5% positive (primary

antibody details may be viewed in Table SI). FISH analysis (Fig. 4F) indicated positive amplification

of the MDM2 gene (for detailed pathological methods, please

refer to Data S1). Following

endoscopic surgical resection, neither patient experienced

significant discomfort or complications. On the first postoperative

day, imaging (Figs. 1C and 2D) confirmed a normal esophageal lumen. A

follow-up chest CT 1 month after surgery showed that the esophageal

lumen remained unobstructed, suggesting a good prognosis (Figs. 1D and 2E).

Discussion

The incidence of esophageal liposarcomas is low,

with most cases originating from the mucosal layer; mesenchymal

tumors account for only 5% (8). The

two cases reported in the present study were both

well-differentiated liposarcomas, characterized by slow growth and

low metastatic potential but with a risk of local recurrence and

resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (9). Research indicates that the development

of well-differentiated liposarcomas is associated with repeated

amplification of chromosome 12, which provides an important

direction for targeted therapy (10). Related studies indicate that

esophageal liposarcomas predominantly occur in males, with an

average onset age of 58.4 years (range, 38–73 years). The tumor

typically extends from the cervical segment to the thoracic

segment. However, its nonspecific clinical manifestations pose

challenges for accurate diagnosis (11–14).

In the present study, in the context of esophageal

liposarcoma, preoperative chest enhanced CT and esophagogastroscopy

were particularly important. These two diagnostic methods not only

provided a clear delineation of the tumor and surrounding

structures but also effectively assessed the tumors' vascular

supply. Chest enhanced CT has a unique advantage in visualizing the

vessels around the tumor; the use of contrast agents allows for

effective differentiation between the tumor and adjacent tissues,

as well as clarifying the blood supply status at the tumor margins.

This imaging technique provided crucial information for evaluating

the tumors' vascularity. By contrast, endoscopic examination offers

a more direct and clearer observational perspective. Through

endoscopy, physicians can view the detailed structures of the tumor

and its surrounding vessels in real-time, enabling direct

assessment and, when necessary, performing biopsies or other

interventions to obtain comprehensive diagnostic information.

Typically, preoperative endoscopy reveals a pedunculated tumor that

could easily be mistaken for a benign lesion, with a definitive

diagnosis relying on postoperative pathological analysis. The

occurrence of high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma is closely

related to the amplification of the 12q13-15 chromosomal region,

while the immunohistochemical triad of MDM2, CDK4 and p16 serves as

its core diagnostic markers (15).

MDM2 gene amplification testing is considered the most

reliable method for distinguishing well-differentiated liposarcomas

from benign lipomas (16).

Currently, there is no standardized treatment

protocol for esophageal liposarcomas and surgical resection remains

the primary treatment. Achieving a negative margin during complete

resection is essential for a curative outcome and for effectively

relieving tumor-induced obstruction. Surgical approaches vary and

include total esophagectomy, subtotal esophagectomy and minimally

invasive techniques. The choice of surgical approach typically

depends on tumor location and size, with options including

transcervical, thoracoscopic or endoscopic access routes.

Historically, open surgery has been the gold standard (6,17–19).

However, with advancements in minimally invasive techniques, these

procedures have become the preferred treatment due to their

benefits, including reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital

stays and faster recovery. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

has emerged as a promising, less invasive alternative, particularly

for smaller tumors with a stalk and no involvement of large blood

vessels. A recent study reported successful endoscopic resection of

well-differentiated esophageal liposarcomas, including a tumor

measuring 8.3×4.2×2.3 cm, demonstrating the feasibility of ESD

(20). In cases where the tumor

volume is large and complete endoscopic resection is not possible,

or if large blood vessels are involved, cervical incision for

resection is a viable option.

The present study reported two cases of giant

esophageal tumors, each exceeding 20 cm in length and 4 cm in

diameter. Gastroscopy findings revealed visible expanded blood

vessels on the surface, with one tumor exhibiting a lobulated

appearance, complicating endoscopic removal. After

multidisciplinary discussions among thoracic surgery and endoscopy

experts, both tumors were presumed to be benign based on

gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound results. As their stalks were

located in the cervical region and confined to the mucosal layer

without muscular invasion, endoscopic resection was considered

feasible. However, given the large tumor sizes and vascular

involvement, the risk of bleeding was high, and limited working

space during endoscopy increased the potential for incomplete

resection and recurrence. Therefore, thoracic surgery support was

necessary to manage potential complications. Following informed

consent from the patients and their families, a multidisciplinary

surgical approach was adopted. Under general anesthesia with

tracheal intubation, the endoscopy team performed ESD, while the

thoracic surgery team provided standby support for rapid

intervention in case of significant bleeding or other complications

beyond endoscopic management. This collaborative approach ensured

patient safety while minimizing surgical trauma. Ultimately, both

tumors were successfully removed endoscopically without

complications and both patients had favorable postoperative

outcomes without requiring any lymph node clearance or adjuvant

therapy.

The insights from this report are as follows: When

patients present with swallowing difficulties, a chest CT scan

should be considered, and if necessary, endoscopy should be

performed to prevent excessive tumor growth and associated

treatment challenges. Prior to endoscopic resection of esophageal

liposarcomas, it is crucial to determine tumor malignancy and stalk

location to determine whether esophageal resection is necessary.

Ensuring that the tumor is confined to the mucosal layer without

muscular invasion helps minimize the risk of esophageal perforation

(21). For large tumors or cases

with significant vascular involvement, procedures should be

conducted under general anesthesia in an operating room equipped

for emergency open surgery if needed in order to handle unexpected

situations and ensure surgical safety. The surgeon should have

extensive experience and blood vessels should be pre-coagulated to

minimize intraoperative bleeding during tumor resection.

Superficial excision should be avoided to prevent recurrence, while

overly deep excision could increase the risk of esophageal

perforation (22). Large tumors may

be difficult to extract through the oropharynx, so it is

recommended to use sterile surgical forceps guided by an endoscope

to grasp the tumor through the oral cavity, ensuring the safety and

effectiveness of the procedure. Postoperatively, patients should

refrain from eating for 3 days and receive jejunal or parenteral

nutrition (23). Follow-up imaging,

including chest CT or upper gastrointestinal studies, should be

conducted promptly to monitor for esophageal fistulas. A follow-up

chest CT or endoscopy is recommended 6 months to 1 year

post-surgery to detect any potential local recurrence (24).

In conclusion, for giant and complex

well-differentiated liposarcomas of the esophagus, endoscopic

surgery combined with multidisciplinary collaboration is a safe and

effective treatment strategy. This approach enables complete tumor

removal while minimizing surgical trauma and ensuring favorable

patient outcomes. Future studies should continue to accumulate case

data to refine treatment strategies, improve endoscopic surgery

success rates and strengthen clinical evidence. In addition,

further exploration of minimally invasive techniques in esophageal

tumor management will be crucial for enhancing patient prognosis

and quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JM was responsible for the conceptualization of the

study and wrote the manuscript. LL collected data and organized

images. XD participated in the conception and design of the study,

was responsible for data analysis and interpretation and guided the

revision of the content. JM, LL and XD confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript..

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Both patients have provided written informed consent

regarding the publication of this case report and related

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability, and subsequently, the authors

revised and edited the content produced by the AI tools as

necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of

the present manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

ESD

|

endoscopic submucosal dissection

|

|

FISH

|

fluorescence in situ hybridization

|

|

P16

|

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

2A

|

|

Vim

|

Vimentin

|

|

CK4

|

cytokeratin 4

|

|

MDM2

|

mouse double minute 2 homolog

|

|

S100

|

S100 calcium-binding protein

|

|

Sox10

|

SRY-box transcription factor 10

|

|

SMA

|

smooth muscle actin

|

|

Melan-A

|

melanocyte antigen

|

|

HMB45

|

human melanoma black 45

|

|

DOG-1

|

discovered on GIST-1

|

|

Ki-67

|

Ki-67 antigen

|

|

P53

|

tumor protein P53

|

References

|

1

|

Ducimetière F, Lurkin A, Ranchère-Vince D,

Decouvelaere AV, Péoc'h M, Istier L, Chalabreysse P, Muller C,

Alberti L, Bringuier PP, et al: Incidence of sarcoma histotypes and

molecular subtypes in a prospective epidemiological study with

central pathology review and molecular testing. PLoS One.

6:e202942011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Anderson WJ and Doyle LA: Updates from the

2020 world health organization classification of soft tissue and

bone tumours. Histopathology. 78:644–657. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Resag A, Toffanin G, Benešová I, Müller L,

Potkrajcic V, Ozaniak A, Lischke R, Bartunkova J, Rosato A, Jöhrens

K, et al: The immune contexture of liposarcoma and its clinical

implications. Cancers (Basel). 14:45782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Somaiah N and Tap W: MDM2-p53 in

liposarcoma: The need for targeted therapies with novel mechanisms

of action. Cancer Treat Rev. 122:1026682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Thway K: Well-differentiated liposarcoma

and dedifferentiated liposarcoma: An updated review. Semin Diagn

Pathol. 36:112–121. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ferrari D, Bernardi D, Siboni S, Lazzari

V, Asti E and Bonavina L: Esophageal lipoma and liposarcoma: A

systematic review. World J Surg. 45:225–234. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ng YA, Lee J, Zheng XJ, Nagaputra JC, Tan

SH and Wong SA: Giant pedunculated oesophageal liposarcomas: A

review of literature and resection techniques. Int J Surg Case Rep.

64:113–119. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Temes R, Quinn P, Davis M, Endara S,

Follis F, Pett S and Wernly J: Endoscopic resection of esophageal

liposarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 116:365–367. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Goldblum JR, Folpe AL and Weiss SW:

Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 7th ed. Elsevier;

Philadelphia: 2020

|

|

10

|

Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH and Jones RL:

Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol.

36:151–159. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Valiuddin HM, Barbetta A, Mungo B,

Montgomery EA and Molena D: Esophageal liposarcoma:

Well-differentiated rhabdomyomatous type. World J Gastrointest

Oncol. 8:835–839. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lin ZC, Chang XZ, Huang XF, Zhang CL, Yu

GS, Wu SY, Ye M and He JX: Giant liposarcoma of the esophagus: A

case report. World J Gastroenterol. 21:9827–9832. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Graham RP, Yasir S, Fritchie KJ, Reid MD,

Greipp PT and Folpe AL: Polypoid fibroadipose tumors of the

esophagus: ‘Giant fibrovascular polyp’ or liposarcoma? A

clinicopathological and molecular cytogenetic study of 13 cases.

Mod Pathol. 31:337–342. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Caceres M, Steeb G, Wilks SM and Garrett

HE Jr: Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and

hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 81:393–396. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kiełbowski K, Ruszel N, Skrzyniarz SA,

Wojtyś ME, Becht R, Ptaszyński K, Gajić D and Wójcik J:

Clinicopathological features of intrathoracic liposarcoma-A

systematic review with an illustrative case. J Clin Med.

11:73532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen C, He X, Jing WY, Qiu Y, Chen M, Luo

TY, Liu XY, Chen HJ, Zhang HY and Bu H: Diagnostic value of MDM2

RNA in situ hybridization in atypical lipomatous

tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma and dedifferentiated

liposarcoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 51:190–195.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Takiguchi G, Nakamura T, Otowa Y, Tomono

A, Kanaji S, Oshikiri T, Suzuki S, Ishida T and Kakeji Y:

Successful resection of giant esophageal liposarcoma by endoscopic

submucosal dissection combined with surgical retrieval: A case

report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2:902016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ye YW, Liao MY, Mou ZM, Shi XX and Xie YC:

Thoracoscopic resection of a huge esophageal dedifferentiated

liposarcoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 8:1698–1704. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bernardi D, Ferrari D, Siboni S, Porta M,

Bruni B and Bonavina L: Minimally invasive approach to esophageal

lipoma. J Surg Case Rep. 2020:rjaa1232020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lee MJ, Lee MW, Joo DC, Hong SM, Baek DH,

Lee BE, Kim GH and Song GA: Effective endoscopic submucosal

dissection of a huge esophageal liposarcoma: A case report. Korean

J Gastroenterol. 83:243–246. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ogami T, Bozanich N, Richter JE and

Velanovich V: Giant esophageal liposarcoma. J Gastrointest Surg.

22:368–370. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rodríguez Pérez A, Pérez Serrano N, García

Tejero A, Escudero Nalda B and Gil Albarellos R: Giant esophageal

liposarcoma in asymptomatic young patient. Cir Esp (Engl Ed).

96:381–383. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fontes F, Fernandes D, Almeida A, Sá I and

Dinis-Ribeiro M: Patient-reported outcomes after surgical,

endoscopic, or radiological techniques for nutritional support in

esophageal cancer patients: A systematic review. Curr Oncol.

31:6171–6190. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Cooke D,

Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Farjah F, Gerdes H, et al:

Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, Version 2.2023,

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc

Netw. 21:393–422. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|