Introduction

Among gynecological malignancies, ovarian cancer

(OV) exhibits the highest mortality rate and constitutes a

significant hazard to the health of female patients (1). Specifically, there were 21,750 new OV

cases and 13,940 deaths from OV in the United States in 2020

(2), and there were 57,090 new

cases of OV and 39,306 deaths from OV in China in 2022 (3). Due to its deep pelvic location, lack

of typical symptoms and lack of early screening tools,

approximately two-thirds of patients have progressed to the

advanced stage of disease at diagnosis, increasing the difficulty

of treatment (4,5). Patients with stage I/II OV have a

10-year survival rate of 29–75%, whereas the 10-year survival rate

drops to 6.9–22% for those with stage III–IV OV (6). Furthermore, >70% of patients with

OV relapse within 2–3 years (7,8).

At present, the treatment of OV is multidisciplinary

and comprehensive, which includes surgery, chemotherapy, targeted

therapy and other therapeutic methods (5,9).

However, the clinical effectiveness of these treatments is often

compromised by drug resistance, cancer recurrence and immune escape

(4,9). Consequently, there is an urgent need

to identify novel molecular targets to improve the assessment of

the progression of OV and enhance the available therapies.

Long non-coding (lnc)RNA refers to a category of RNA

molecules whose transcript length is >200 nt (10). Due to the lack of conservative open

reading frames, most lncRNAs are incapable of direct translation

into proteins (11–13). However, lncRNA can recruit

chromatin-remodeling complexes to regulate chromosome structure and

modification (for instance, DNA methylation and histone

modification), thus affecting gene expression levels (14,15).

Chen and An (16) reported that the

expression of lncRNA activated by TGF-β (ATB) is elevated in OV

tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues, and it is linked to

unfavorable outcomes. Furthermore, ATB facilitated the

proliferation, invasion and migration of OV cells by mediating

histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation through binding to enhancer of

zeste homolog 2 (16). lncRNAs also

possess the capacity to regulate the transcription of target genes

through interacting with transcriptional regulatory molecules

(17–19). Moreover, lncRNA can bind RNA binding

protein (RBP) to participate in alternative splicing, mRNA

metabolism and transport (17,18,20).

Gordon et al (21) reported

that high metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

(MALAT1) expression is associated with increased stage, recurrence

and decreased survival in OV, and that MALAT1 promotes OV

progression by promoting the expression of RNA binding fox-1

homolog 2 and inhibiting preferential splicing of the pro-apoptotic

isoform of kinesin family member 1b. Furthermore, lncRNA can

function as a micro (mi)RNA sponge that reduces the activity of

miRNA, thus enhancing the expression level of target genes

(22). Zhou et al (23) reported that the expression levels of

lncRNA isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 antisense RNA 1 (IDH1-AS1) are

lower in epithelial OV cells than in normal ovarian epithelial

cells, and IDH1-AS1 expression indicates a favorable prognosis.

Additionally, IDH1-AS1 serves as a sponge for miR-518c-5p to

suppress the proliferation of epithelial OV cells by targeting RNA

binding motif protein 47 (23). In

conclusion, lncRNAs serve a vital role in the progression of

malignant tumors.

Regulated cell death (RCD) is a mode of cell death

based on precise signaling networks and molecular mechanisms, and

includes apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis

(24,25). Recently, Tsvetkov et al

(26) reported a new

copper-dependent RCD, termed cuproptosis. Excess intracellular

copper can interact with lipid-acylated proteins, which triggers

irregular clustering of lipid-acylated proteins and depletion of

iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, ultimately culminating in cuproptosis

(26). In addition, elesclomol (a

potent copper ionophore) combined with copper can induce

cuproptosis, whilst tetrathiopolybdate (a copper chelator) can

inhibit cuproptosis, and cells with higher acylated protein level

are more sensitive to cuproptosis (26). Ferrodoxin 1 functions as a vital

positive regulator in cuproptosis, and other genes have also been

identified as being closely related to cuproptosis (26–29).

For instance, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) can be

activated by intracellular copper, which can lead to cell death,

whilst tetrathiopolybdate can inhibit NLRP3 activation (27). Furthermore, certain studies have

reported that certain lncRNAs can regulate cuproptosis-related

genes and are thereby considered novel potential targets in

cuproptosis (30–33). For instance, LINC00996 has been

identified as the key cuproptosis-related lncRNA in lung and

bladder cancer (32,33). An in-depth study of cuproptosis

could provide the ideal risk model and an accurate biomarker for

malignant tumors; however, the function and underlying regulatory

pathways of cuproptosis in OV are still poorly studied.

Therefore, the present study aimed to construct a

prognostic risk model based on lncRNAs associated with cuproptosis

in OV and to explore the regulatory mechanism of LINC00996 in

cuproptosis in OV.

Materials and methods

Data collection and processing

The present study accessed the RNA sequencing

(RNA-seq) data and clinical records of patients with OV from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-OV dataset (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). The RNA-seq data was

in fragments per Kilobase per Million format. The clinical records

obtained included the age, stage, grade, survival status and

survival time of the patients. A total of 378 patients with OV with

complete data were randomly allocated to two groups, a training set

(n=189) and a validation set (n=189), based on

‘createDataPartition’ package

(rdocumentation.org/packages/caret/versions/6.0–94/topics/createDataPartition)

in R programming (version 4.1.1). ‘createDataPartition’ uses the

following basic syntax: createDataPartition (y, p=0.5, list=FALSE,

…), with y representing the vector of outcomes and prepresenting

percentage of data to use in the training set. The remaining data

formed the validation set.

Identification of cuproptosis-related

lncRNAs

Using the keywords ‘cuproptosis,’ ‘copper’ and

‘regulated cell death’ to search the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science

(webofscience.com/) databases, articles related to cuproptosis were

screened. Subsequently, by carefully reading the relevant articles,

the cuproptosis-related genes and their functions were summarized.

In addition, relevant reviews were consulted to identify other

cuproptosis-related genes and their functions. Finally, 15

cuproptosis-related genes were obtained from previous studies

(26–29). ENSEMBL (Release 111) (ensembl.org)

was used to extract lncRNAs from the RNA-seq data. Subsequently,

using the ‘limma’ packages (version 3.48.3) in R programming

(version 4.1.1) and the Wilcoxon rank sum test, the Pearson

correlation coefficients between lncRNA and cuproptosis-related

genes were calculated.. The cut-off criteria included correlation

coefficient (r) of >0.4 or <-0.4) and P<0.001. Additional

notes that correlation coefficient |r| <0.4 indicated a weak

correlation, 0.4 ~ 0.7 indicated a moderate correlation, and

>0.7 indicated a strong correlation. Finally, a Sankey diagram

was drawn based on the ‘dplyr (version 1.0.7)’, ‘ggplot2 (version

3.4.0)’ and ‘ggalluvial (version 0.12.3)’ packages in R programming

(version 4.1.1).

Construction of the risk model

There was no discernible difference in the clinical

characteristics between the training and the validation sets.

Univariate Cox regression was performed to identify

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs associated with overall survival (OS)

in the training set. Among these lncRNAs, the risk model was

constructed using least absolute shrinkage selection operator

(LASSO) regression analysis and multivariate Cox regression. The

risk score was calculated as follows: Risk score =

∑nk=1 coef(lncRNAk) ×

expr(lncRNAk), where coef(lncRNA) represents the link

between the lncRNA and the survival of the patient with OV, and

expr(lncRNA) represents the expression level of the lncRNA. The

analysis was performed using R programming (version 4.1.1).

Identification of the prognostic

signature

Patients with a risk score >1 were considered

high-risk, while those with a risk score ≤1 were considered

low-risk, and the survival status and immune function in the low-

and high-risk groups were analyzed. Univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analysis were performed to identify independent

predictors. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were then produced to

compare the difference in the survival rate between the low- and

high-risk groups using the ‘survival (version 3.4.0)’ and

‘survminer (version 0.4.9)’ packages. Furthermore, receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves, calibration curves, C-index

and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed. The analysis

was carried out by R programming (version 4.1.1).

Cell culture

OVCAR3 cells were acquired from the American Type

Culture Collection and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial

Institute-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; both Gibco,

Thermo Fisher Scientific Corporation). The cells were incubated in

an environment that mimicked physiological conditions, with an

atmosphere containing 5% CO2 to maintain an optimal pH

level and ensure proper gas exchange, while being maintained at a

constant temperature of 37°C.

Transfection of small interference

(si)RNA

The LINC00996 siRNA (siLINC00996) and control siRNA

(siControl) were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. When

the cell density reached 60–75%, the transfection solution was

configured as follows: Solution A, 250 µl OPTI-MEM (Gibco, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 5 µl Lipo3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific Corporation); and solution B, 250 µl OPTI-MEM

with 50 nM siRNA (Genepharma Corporation), which were both

incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, solutions A

and B were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 20 min.

Then, the medium was removed from a 6-well plate containing OVCAR3

cells, and 1500 µl serum-free medium and 500 µl mixed solution was

added at room temperature. Finally, After incubation for 12 h, it

was replaced with fresh medium and further cultured in an incubator

with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 h. The sequences of the siRNAs used were

as follows: siLINC00996-1, 5′-GCUGUGUGAAAGGGUUUAATT-3′ and

5′-UUAAACCCUUUCACACAGCTT-3′; siLINC00996-2,

5′-CCGGCCUUAUUGUUUCUAUTT-3′ and 5′-AUAGAAACAAUAAGGCCGGTT-3′; and

siControl, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′.

Extraction of RNA and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

analysis

Extraction of total RNA from OVCAR3 cells was

performed using the RNA Extraction Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT was performed to

convert RNA into cDNA with HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix

(Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. RNA expression was measured by ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR

Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) with ABI ViiA™ 7 real-time

fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument equipped with ViiATM7

system. Thermocycling conditions are as follows: Pre-denaturation

at 95°C for 3 min, then 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 95°C

for 15 sec as 1 cycle for 40 cycles. The relative gene expression

was calculated by 2−∆∆Cq method with GAPDH as the

control (34). The primers (Tsingke

Corporation) used were as follows: LINC00996 forward,

5′-CTCTGCCACATCGTTCGGTTC-3′ and reverse

5′-CTTCTTACGCTGCCAACTGCTAA-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′.

Cell proliferation and migration

assay

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was performed to

measure proliferative ability. OVCAR3 cells were cultured in a

96-well plate. After adding CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 1 h, the absorbance was measured at 490 nm based

on microplate reader.

A Transwell assay was the performed to evaluate

migration ability. A cell suspension including 2×10^5 cells without

FBS was added to the upper chamber and medium with 20% FBS was

added to the lower chamber of the Transwell plate. The cells were

incubated at 37°C for 24 h. When the cells passed through the

membrane, 4% paraformaldehyde and crystal violet were added to the

upper chamber for 15 min at room temperature. The results were

observed under an inverted optical microscope (Shanghai Optical

Instrument Factory) and counted using ImageJ 1.8.0 software

(National Institutes of Health).

Sensitivity to cuproptosis

Elesclomol can facilitate the transport of

Cu2+ into cells. After entering the cells,

Cu2+ directly binds to lipoylated enzymes and prompts

the aggregation of lipoylated proteins and the dissipation of Fe-S

cluster proteins, leading to proteotoxic stress and ultimately

cuproptosis (26). Therefore,

cuproptosis was induced by adding elesclomol-CuCl2

(Medchemexpress Corporation; 1×10−9 M to 10−4

M into the medium of OVCAR3 cells in a 5% CO2 incubator

at 37°C for 4 h. CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was added for 1 h to measure the number of living

cells and thus assess the sensitivity of cells to cuproptosis, in

which the absorbance was measured at 490 nm based on microplate

reader.

Prediction of RBPs and target

mRNA

The RBPs that can interact with LINC00996 were

predicted using the ENCORI database (https://rnasysu.com/encori/). The filtering condition

was CLIP Data ≥1 (results were supported by at least one

cross-linking immunoprecipitation. Based on ENCORI, the target

mRNAs of the aforementioned RBPs were predicted. Because of the

large number of predicted target mRNAs, we set more stringent

filtering criteria as follows: CLIP Data was ≥4 and the number of

pan-cancer was ≥10, which meant the results were supported by ≥4

cross-linking immunoprecipitation and were validated in at least 10

cancer types. In addition, expression of target lncRNA in ovarian

cancer patients was analyzed using the Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis (GEPIA; gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), and locations

of target lncRNA are predicted by lncLocator

(csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/lncLocator/).

Prediction of miRNA and target

mRNA

The miRNAs that can interact with LINC00996 were

identified using DIANA Tools (http://diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/DianaTools/index.php).

Furthermore, ENCORI was used to predict the target genes of the

aforementioned miRNAs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R

programming (version 4.1.1) (https://www.r-project.org/about.html) and GraphPad

Prism 9 (version 9.0.0; Dotmatics). Statistical differences for

three-group comparisons were determined using one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test. The CCK-8 assay data were analyzed two-way

ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. All P-values were two-sided and

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Identification of cuproptosis-related

lncRNAs with prognostic significance

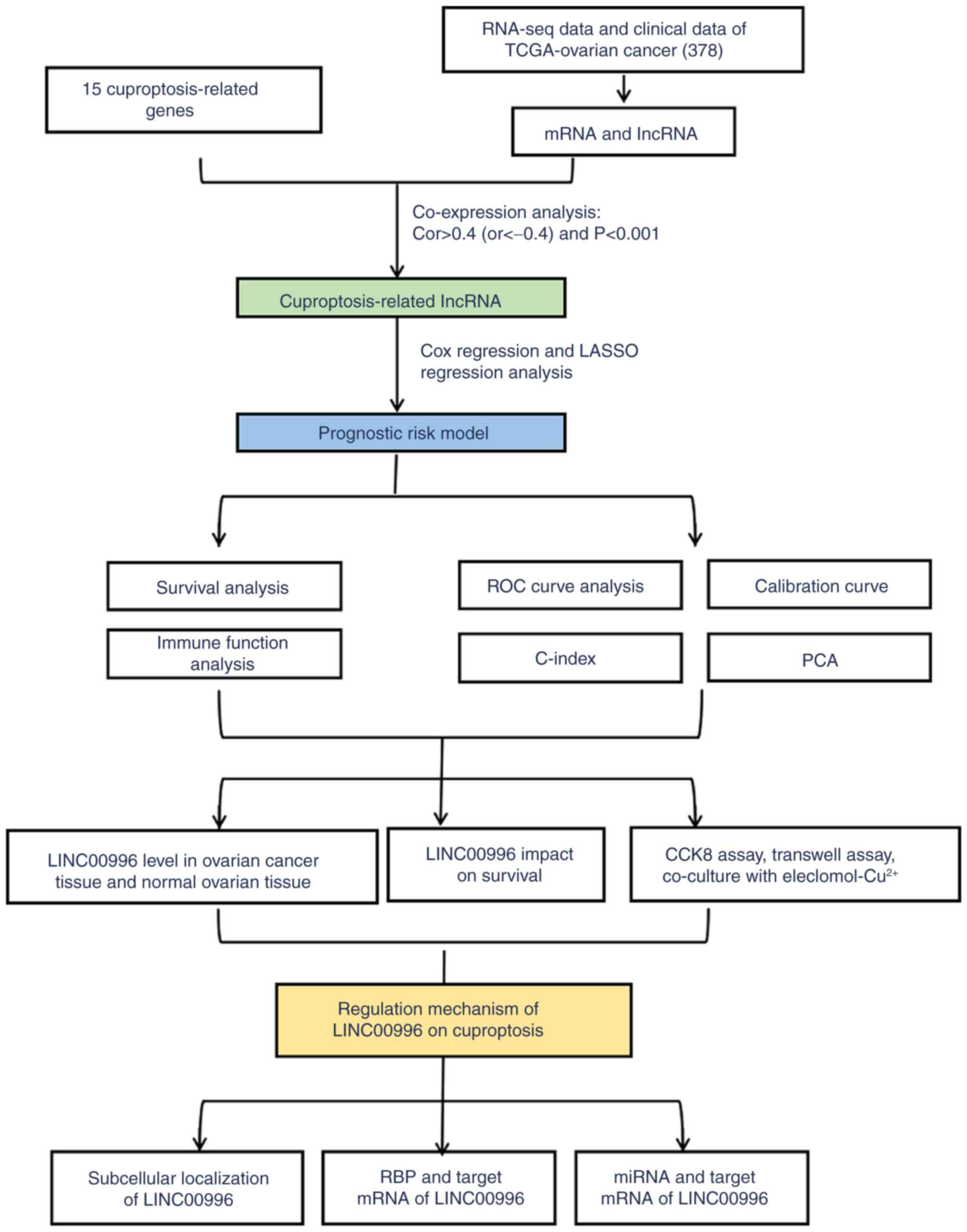

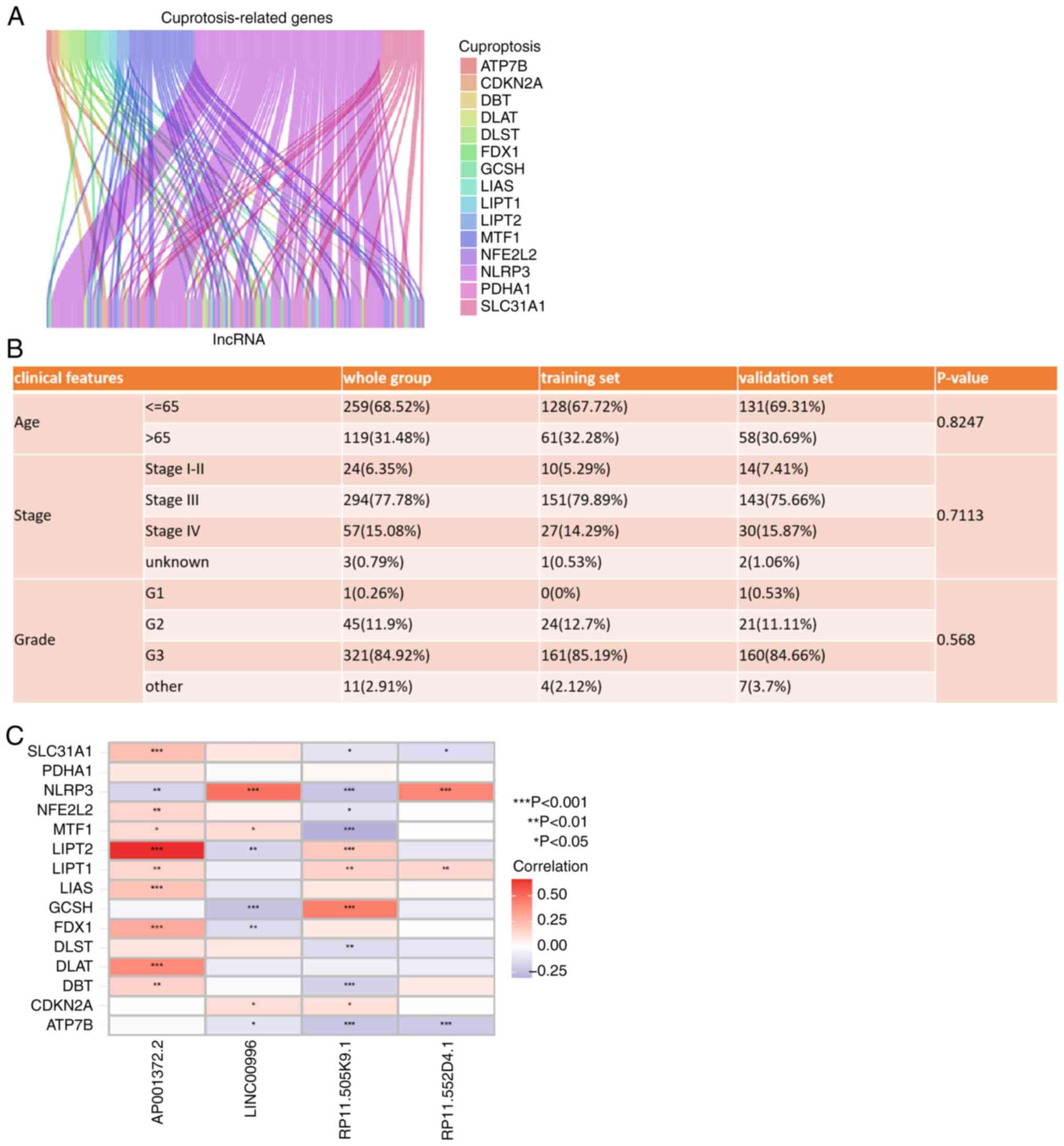

The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Based on previous articles and

reviews related to cuproptosis, 15 cuproptosis-related genes were

identified (Table SI) (26–29).

Subsequently, 14,831 lncRNAs were obtained from TCGA-OV cohort

through the ENSEMBL database. Pearson correlation analysis was

performed to assess the correlation between cuproptosis-related

genes and lncRNAs based on the ‘limma (version 3.48.3)’ packages

and the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The criteria for

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs were r>0.4 (or <-0.4) and

P<0.001. Finally, 140 lncRNAs were identified as

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs (Fig.

2A). The RNA-seq data and clinical records of 378 patients with

OV were collected from TCGA-OV dataset. These patients with OV were

randomly divided into a training set (n=189) and a validation set

(n=189), both of which had similar clinical characteristics

(Fig. 2B). Univariate Cox

regression analysis was performed to identify the

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs with prognostic significance in the

training set. Among these lncRNAs, a risk model was constructed

using LASSO regression and multivariate Cox regression. The risk

model was calculated as the following formula: Risk = (0.687927022

× RP11-552D4.1) - (0.659783022 × AP001372.2) - (0.652465319 ×

RP11-505K9.1) - (1.627006889 × LINC00996). Among the lncRNAs

identified, RP11-552D4.1 was found to be a risk factor, while

AP001372.2, RP11-505K9.1 and LINC00996 were protective factors. The

correlation between these 4 lncRNAs and the identified

cuproptosis-related genes is shown in Fig. 2C. LINC00996 with the highest

correlation coefficient in the risk model is significantly

positively correlated with NLRP3 (P<0.001).

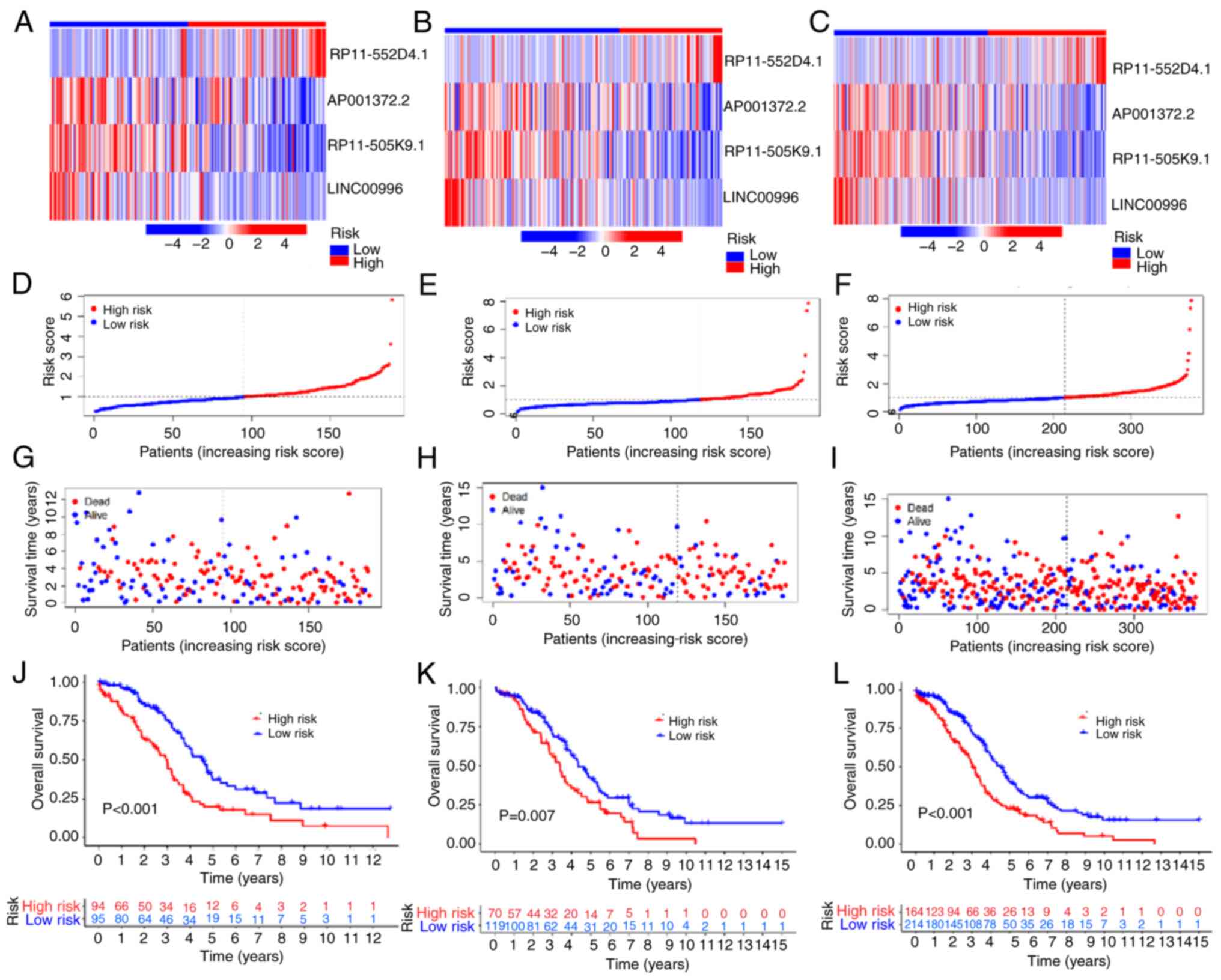

Predictive ability of the risk

model

The expression of 4 lncRNAs (RP11.552D4.1,

AP001372.2, RP11.505K9.1 and LINC00996) in the training set,

validation set and whole group are shown using heat maps in

Fig. 3A-C. Patients with a risk

score of >1 were considered high-risk, while those with a risk

score of ≤1 were considered low-risk. (Fig. 3D-F). Compared with the low-risk

group, more deaths were observed in the high-risk group (Fig. 3G-I) in the training and validation

set and whole group. Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrated that

the prognosis of patients with OV in the low-risk group was

superior compared with the high-risk group (training set,

P<0.001; validation set, P=0.007; whole group, P<0.001;

Fig. 3J-L). These results suggested

that the risk model is reliable in predicting the prognosis of

patients with OV.

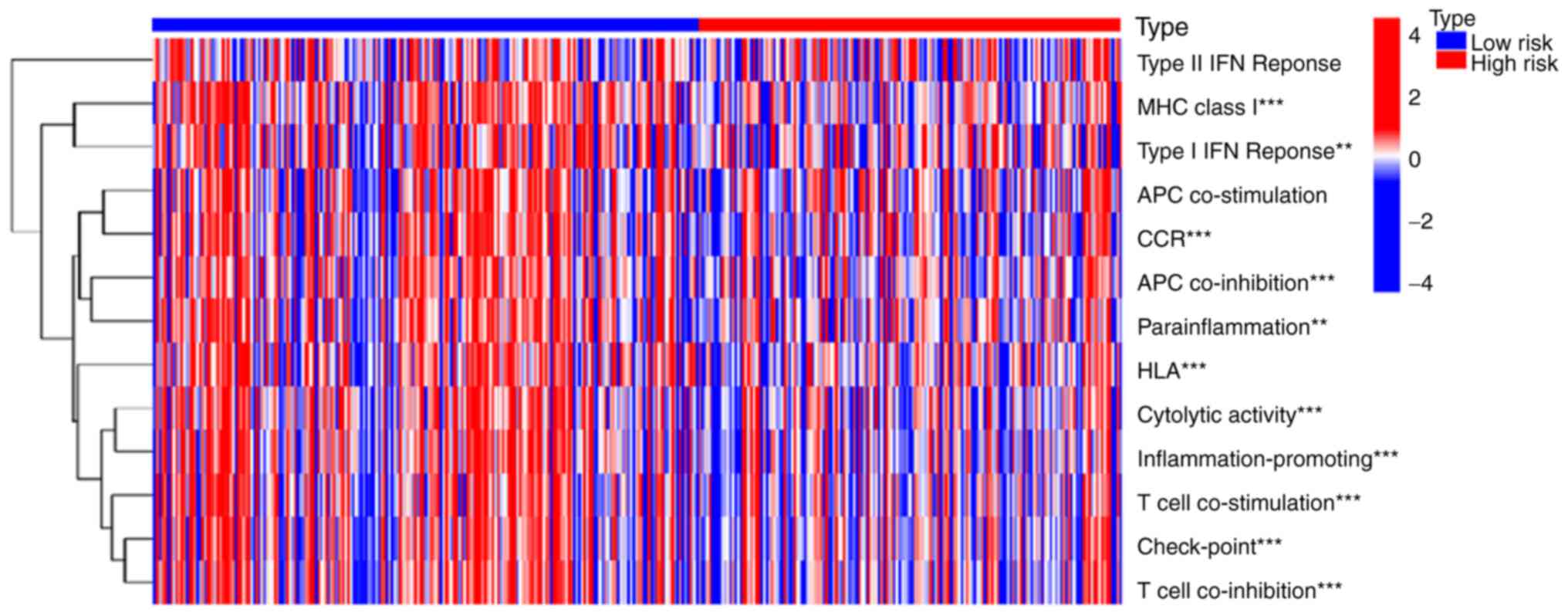

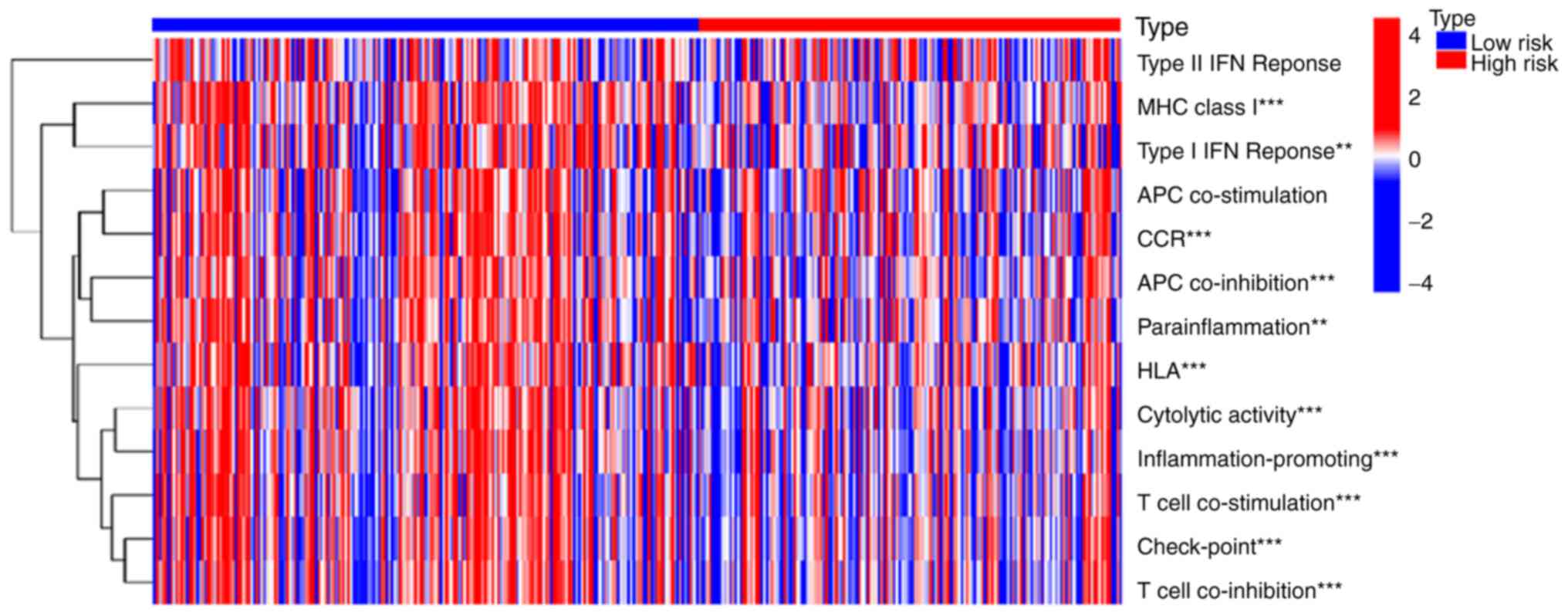

Immune function analysis of the risk

model

There is an association between cuproptosis and

immune function (35). Excessive

intracellular copper can lead to cuproptosis, which subsequently

triggers immunogenic cell death and activates antitumor immune

responses, thereby reprogramming the immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment (35,36). Moreover, cuproptosis-inducing drugs

can markedly inhibit tumor growth and hold promising prospects for

broad clinical application (35,36).

Recent research has developed nanomedicines that can induce

cuproptosis, which can notably inhibit tumor growth and promote

immune responses, and in combination with programmed cell death 1

immunotherapy, they can markedly enhance antitumor efficacy

(37). Thus, a thorough

investigation into the association between cuproptosis and immune

function holds promise for refining immunotherapy and enhancing

antitumor efficacy in OV.

Based on immune function analysis, the generated

heat map demonstrated that the high- and low-risk groups differed

significantly in their immune functions (Fig. 4). The high-risk group had poorer

immune functions in major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-class-I,

type I interferon (IFN) response, chemokine receptor (CCR),

antigen-presenting cell (APC) co-inhibition, parainflammation,

human leukocyte antigen (HLA), cytolytic activity,

inflammation-promoting, T cell co-stimulation, check-point and T

cell co-inhibition. Therefore, the changes in immune function in

the high-risk group may result in the progression of patients with

OV.

| Figure 4.Immune function analysis of the risk

model. The results showed that the high-risk group had poorer

immune functions in MHC-class-I, type I IFN response, CCR, APC

co-inhibition, parainflammation, HLA, cytolytic activity,

inflammation-promoting, T cell co-stimulation, check-point and T

cell co-inhibition. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. MHC, major

histocompatibility complex; IFN, interferon; CCR, chemokine

receptor; APC, antigen-presenting cell; HLA, human leukocyte

antigen. All the original data came from TCGA-OV cohort. |

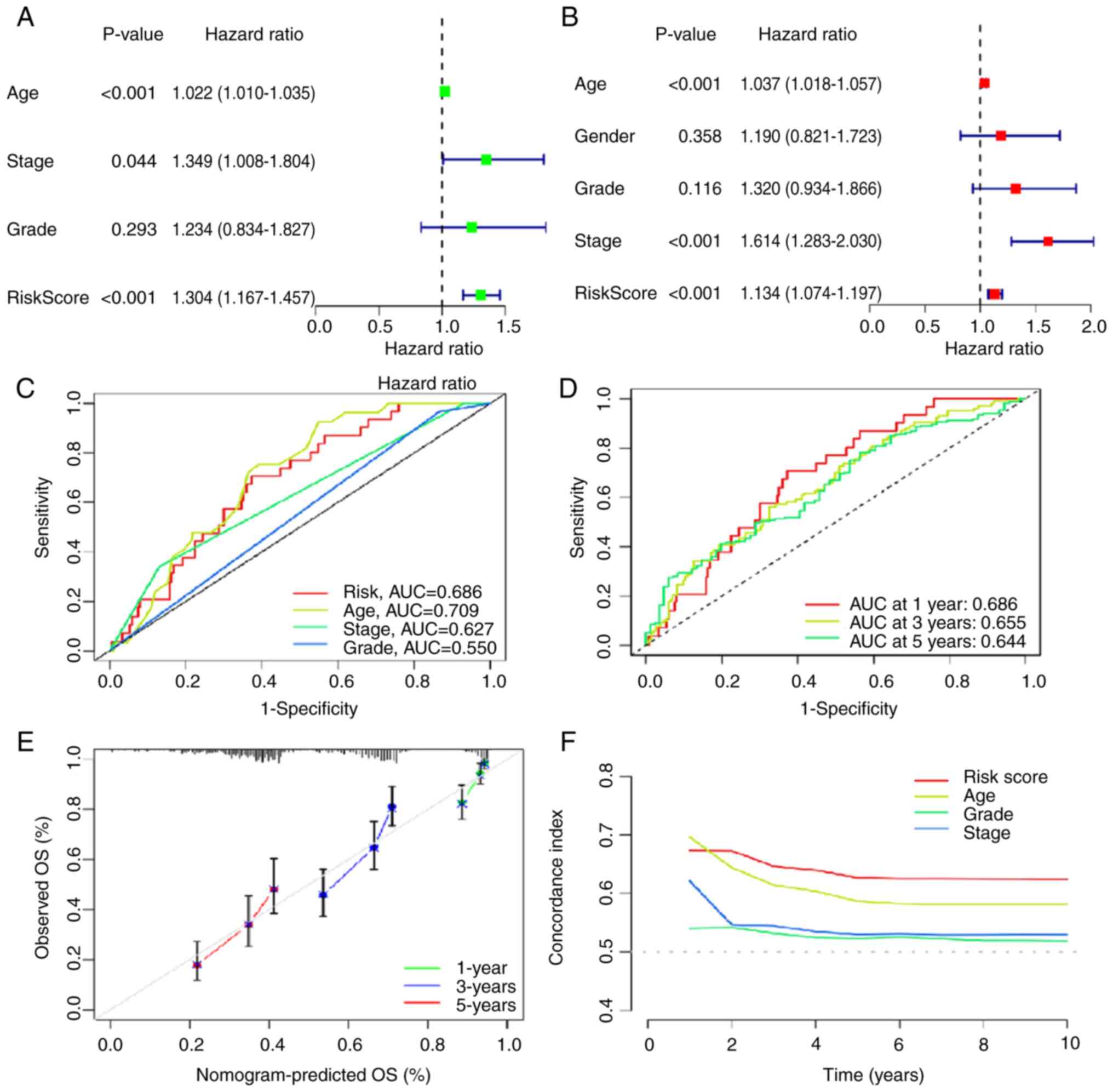

Clinical significance of the risk

model

Using univariate and multivariate Cox regression,

the risk model was identified as an independent prognostic risk

factor in OV (Fig. 5A and B).

Additionally, the area under curve (AUC) of the ROC was calculated,

which measured the prediction accuracy of the risk model. The

closer the AUC value was to 1, the better the differentiation of

the risk model and the higher the prediction accuracy of the risk

model. As shown in Fig. 5C, the AUC

of the risk model was 0.686, which demonstrated good

differentiation and prediction accuracy. Moreover, the prognostic

predictions of the risk model displayed good predictive performance

for OS in patients with OV (1-year, AUC=0.686; 3-year, AUC=0.655;

and 5-year, AUC=0.644; Fig. 5D).

The calibration curve for 1-, 3- and 5-year OS also showed reliable

predictive ability of the risk model (Fig. 5E) and the C-index of the risk model

outranked that of other factors (Fig.

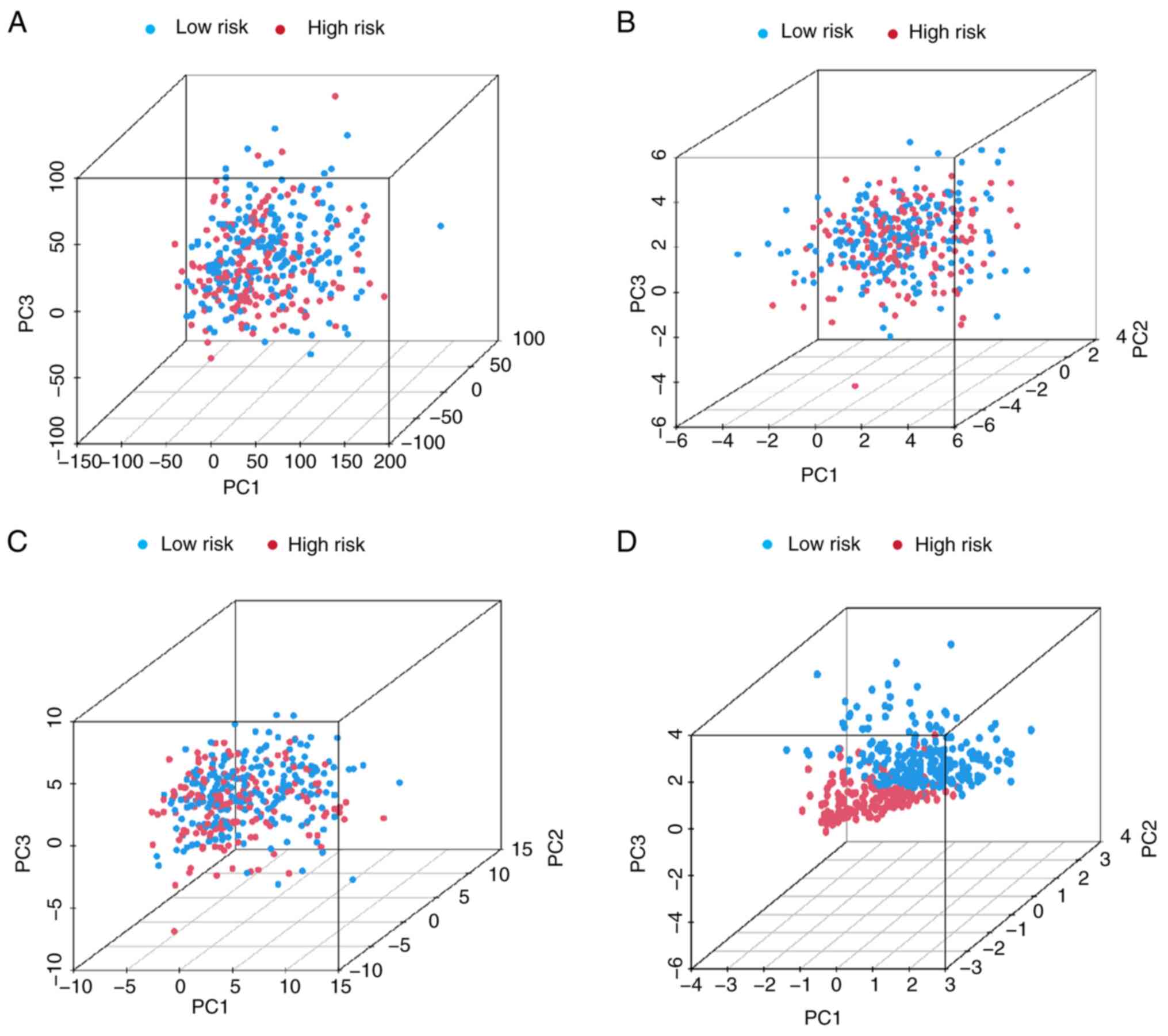

5F). Furthermore, PCA was performed based on all genes

(Fig. 6A), the cuproptosis-related

gene set (Fig. 6B), the

cuproptosis-related lncRNA set (Fig.

6C) and the risk model (Fig.

6D). There were markedly different distribution of the high-

and low-risk groups in the PCA based on the risk model, suggesting

that the risk model may serve as a promising biomarker for risk

stratification. In summary, the risk model could accurately predict

prognosis and has notable clinical value.

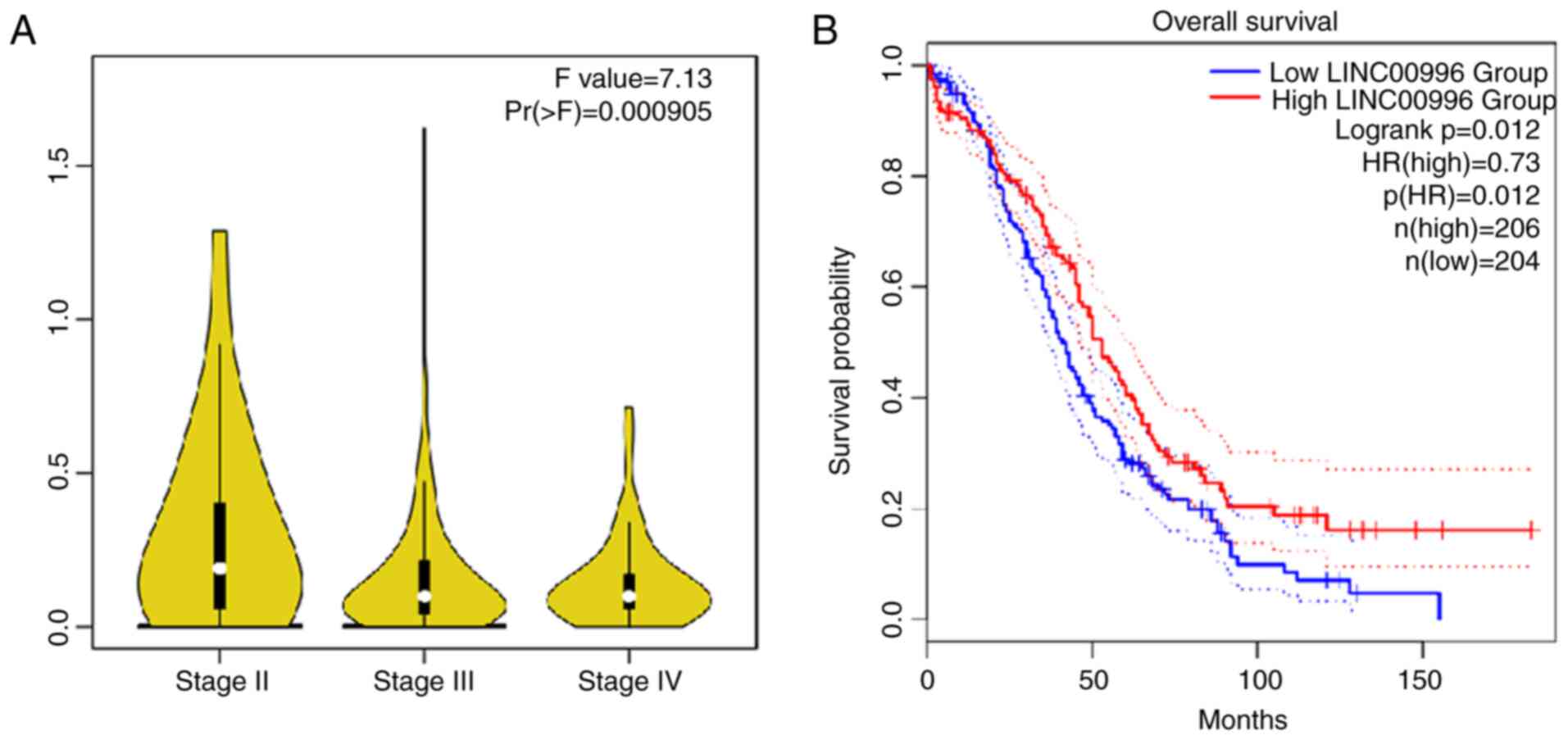

Effect of LINC00996 in patients with

OV

In the risk model, the correlation coefficient of

LINC00996 was the highest compared with the other lncRNAs,

indicating that it may serve a crucial role in cuproptosis in OV.

Certain studies have reported the function of LINC00996 in several

malignant tumors, such as colorectal cancer and lung

adenocarcinoma, yet its potential role and importance in OV remain

incompletely understood (38,39).

Furthermore, data from GEPIA suggested that the LINC00996

expression level is lower in patients with OV with a higher

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage

compared with those with a lower FIGO stage (40) (Fig.

7A). Kaplan-Meier survival curves also demonstrated that the

lower the expression of LINC00996, the lower the survival rate of

patients with OV (Fig. 7B). These

results suggest that LINC00996 may serve an inhibitory role in

OV.

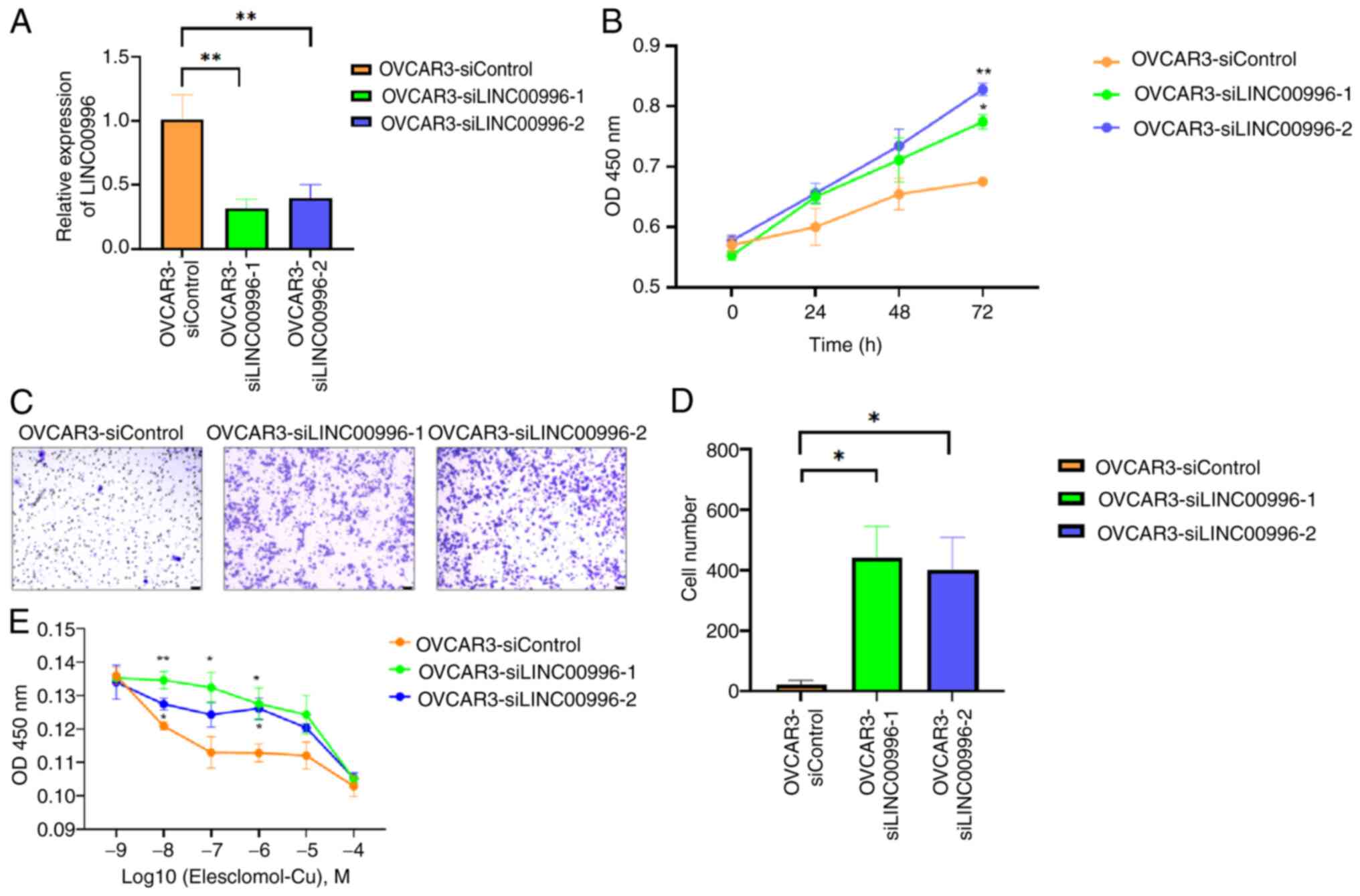

Effect of LINC00996 on the biological

behavior of OV cells

After transfecting siLINC00996-1 and siLINC00.996-2

into OVCAR3 cells to knockdown LINC00996 expression, the role of

LINC00996 in OV cells was further explored (Fig. 8A). The results of the CCK-8 assay

revealed that knockdown of LINC00996 improved the proliferative

ability of OV cells (Fig. 8B).

Moreover, the results of the Transwell assay demonstrated that the

knockdown of LINC00996 enhanced the migration ability of OV cells

(Fig. 8C and D). Elesclomol

facilitates the intracellular translocation of Cu2+,

thereby inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and triggering

cuproptosis (26). After culturing

the cells with different concentrations of

elesclomol-Cu2+ solution (ranging from 10−9

to 10−4 mol/l), a CCK-8 assay was performed to assess

the sensitivity of the cells to cuproptosis. The results suggested

that the knockdown of LINC00996 reduced the sensitivity of OV cells

to cuproptosis (Fig. 8E).

Regulatory mechanism of LINC00996

binding to ELAV-like RNA binding protein 1 (ELAVL1) in

cuproptosis

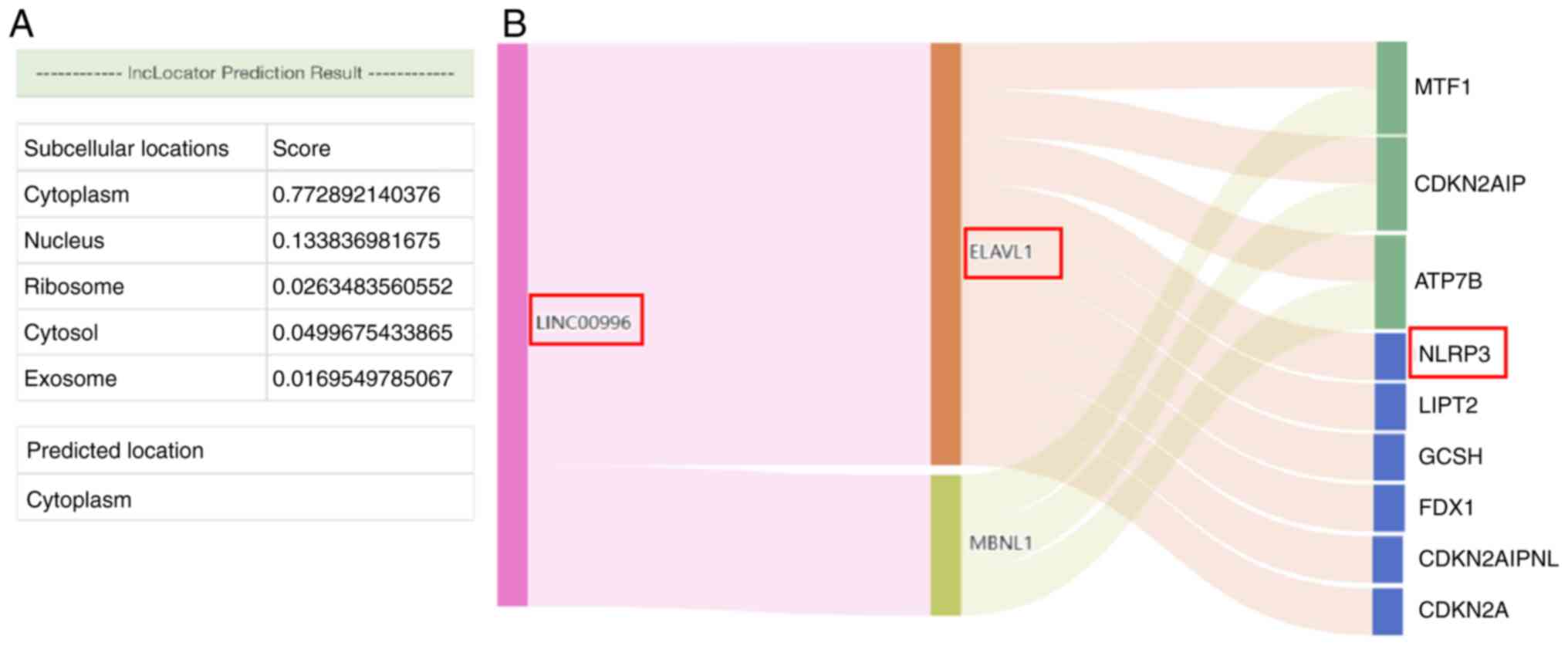

Based on the results from lncLocator, LINC00996 was

determined to be primarily located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 9A). This subcellular localization

suggested that LINC00996 may bind to RBPs or act as an miRNA

sponge. According to the correlation between LINC00996 and genes

associated with cuproptosis, LINC00996 was significantly positively

correlated with NLRP3 (P<0.001) (Fig. 2C). Moreover, to predict the RBPs

that can bind to LINC00996 as well as the target mRNAs, stringent

filtering conditions were set in ENCORI. RBPs interacting with

LINC00996 were predicted using ENCORI, filtered by CLIP Data ≥1.

The results showed that ELAVL1 and muscleblind-like splicing

regulator 1 may bind to LINC00996. Subsequently, the target mRNAs

of the aforementioned two RBPs were predicted, filtered by CLIP

Data ≥4 and pan-cancer count ≥10. The results suggested that ELAVL1

could interact with NLRP3 mRNA (Fig.

9B).

Regulatory mechanism of LINC00996 as

an miRNA sponge in cuproptosis

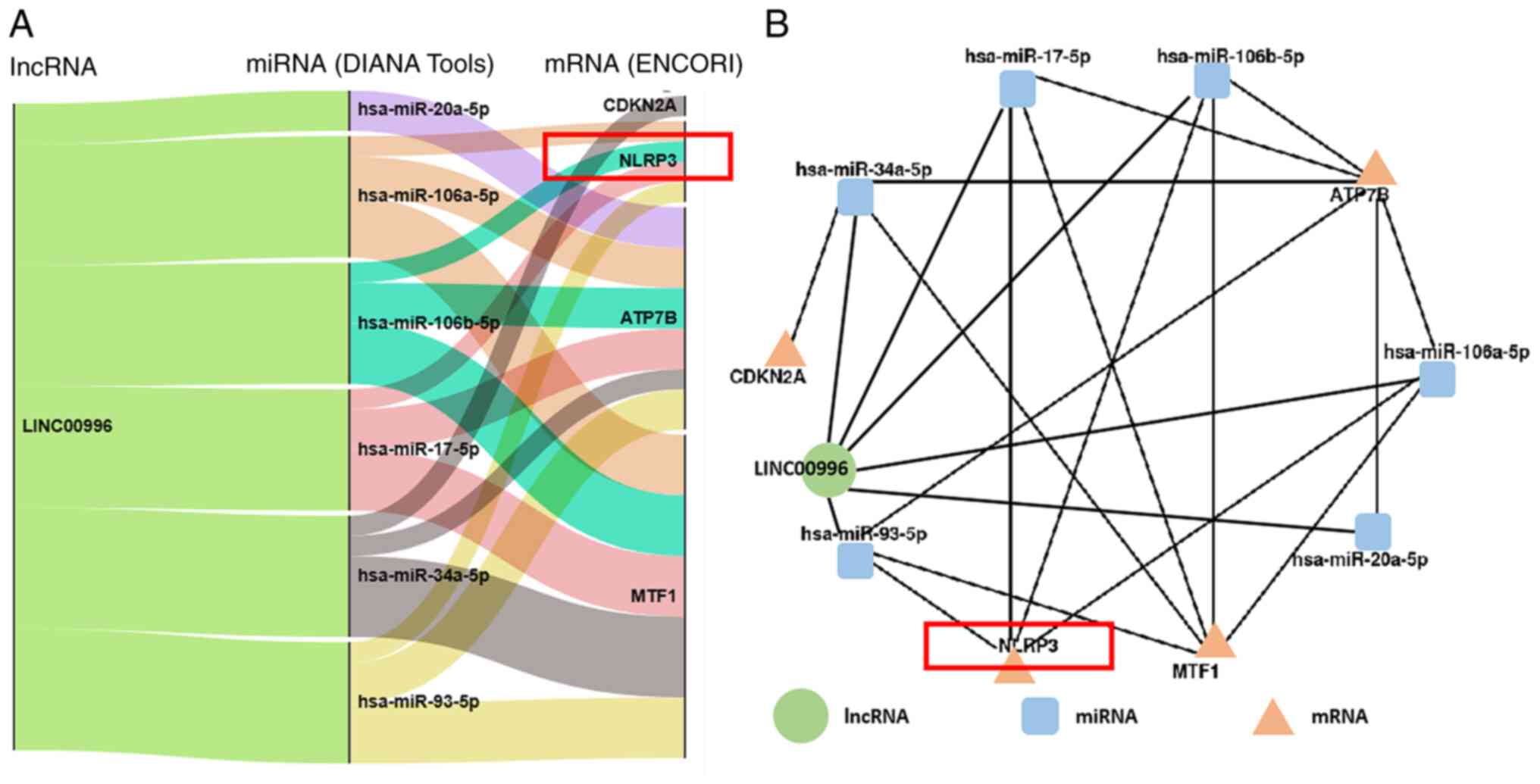

Previous studies have suggested that miRNA recognize

and bind to target mRNA, typically promoting mRNA degradation or

inhibiting its translation. Additionally, lncRNAs can bind to

specific miRNAs and modulate the expression levels of the target

mRNAs, thereby forming a regulatory network consisting of

lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA (22). In the

present study, the miRNAs that interact with LINC00996 were

predicted utilizing the DIANA tools. The findings revealed that

hsa-miR-20a-5p, hsa-miR-106a-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p, hsa-miR-17-5p,

hsa-miR-34a-5p and hsa-miR-93-5p could interact with LINC00996.

Based on ENCORI, the target mRNAs of these 6 miRNAs were then

predicted (Fig. 10A).

Consequently, a comprehensive lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network

pertinent to cuproptosis was constructed (Fig. 10B). Notably, among the

aforementioned 6 miRNAs, hsa-miR-106a-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p,

hsa-miR-17-5p and hsa-miR-93-5p may act on NLRP3 mRNA. This

comprehensive lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network will be further

verified in subsequent studies.

Discussion

In the present study, after analyzing the TCGA-OV

cohort, a prognostic risk model based on cuproptosis-associated

lncRNAs was constructed. Survival analysis, ROC curves, calibration

curves, C-index and PCA demonstrated the reliability of the

constructed risk model. The potential mechanism of LINC00996 in the

aforementioned risk model was then predicted using ENCORI and DIANA

tools. The prognostic risk model can divide patients with OV into

high- and low-risk groups. Furthermore, the immune function

analysis demonstrated that MHC-class-I, type I IFN response, CCR,

APC co-inhibition, parainflammation, HLA, cytolytic activity,

inflammation-promoting, T cell co-stimulation, check-point and T

cell co-inhibition were improved in the low-risk group (41–45).

MHC-class-I can present intracellular peptides, which are

recognized by CD8+ T cells, thus inducing an antitumor

immune response (41–43). The findings of the present study

suggested that the low-risk group had a more optimal immune

function in MHC-class-I, indicating that the improved prognosis in

the low-risk group may be associated with the antitumor immune

response induced by MHC-class-I. However, the effect of different

immune functions between groups on the prognosis of patients with

OV needs further analysis and experimental verification.

Excess intracellular copper can interact with lipid

acylated proteins, and this process triggers irregular clustering

of lipid-acylated proteins and depletion of Fe-S clusters,

ultimately culminating in cuproptosis (26,46).

However, the role of cuproptosis in tumor progression and its

regulatory mechanism are poorly understood. The present study

constructed a prognostic risk model of lncRNAs associated with

cuproptosis and demonstrated that patients with OV in low-risk

group had an improved prognosis. We hypothesized that patients with

OV in the low-risk group would be more sensitive to cuproptosis

than those in the high-risk group. Cuproptosis provides new

perspectives on the treatment approach of OV, and the induction of

cuproptosis may be an emerging treatment option. Moreover, O'Day

et al (47) reported that

combination therapy of elesclomol and paclitaxel could markedly

increase the survival rate of patients with stage IV metastatic

melanoma. In the present study, after culturing with

elesclomol-Cu2+, the sensitivity of OV cells to

cuproptosis was positively associated with the level of LINC00996.

Therefore, LINC00996 could be a new prognostic biomarker for OV,

and the induction of cuproptosis may be a potent treatment for

patients with OV.

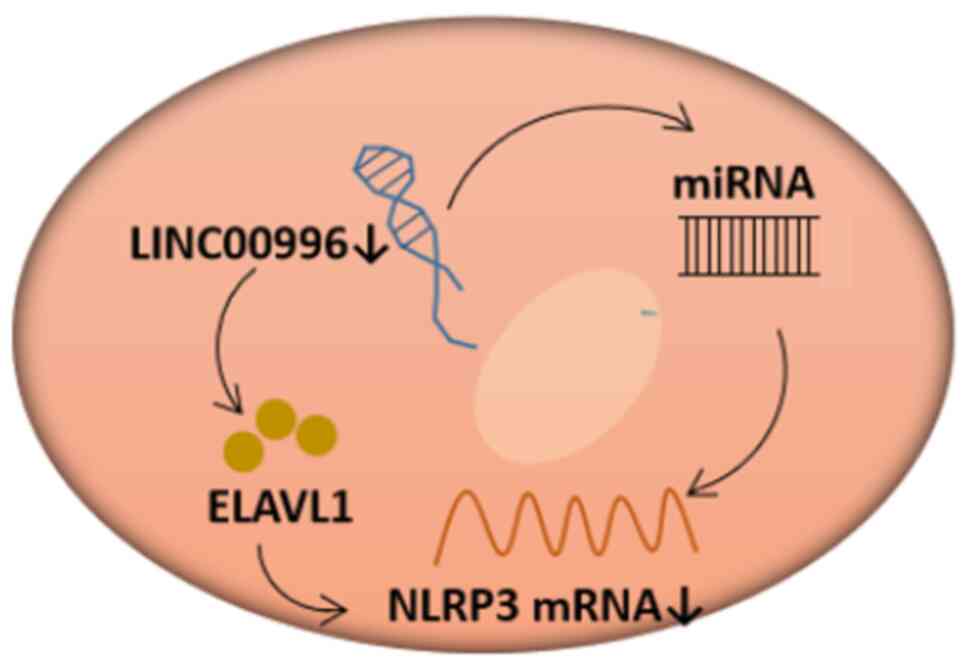

The key lncRNA of the prognostic risk model in the

present study was LINC00996, which was significantly positively

correlated with the cuproptosis-related gene, NLRP3. According to

previous reports, lncRNAs that are located in the nucleus can

regulate chromatin structure and histone modifications and affect

gene transcription, while lncRNAs that are localized in the

cytoplasm can regulate mRNA translation and degradation (48,49).

LINC00996 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm, suggesting that

LINC00996 regulates cuproptosis in OV through binding RBPs or

acting as an miRNA sponge (Fig.

11). Data from ENCORI suggested that the RBP, ELAVL1, can bind

to LINC00996. ELAVL1 can increase mRNA stability and serves a vital

role in tumor progression (50,51).

Additionally, NLRP3 was the target mRNA of ELAVL1 based on ENCORI.

ELAVL1 can bind to adenine and uridine-rich stability elements to

improve mRNA stability (52–55).

Liu et al (56) reported

that in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes and human

umbilical vein endothelial cells, the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling

of ELAVL1 is initiated and ELAVL1 expression is notably elevated in

the cytoplasm, which increases the stability of NLRP3 mRNA and

promotes NLRP3 expression, after TNF-α and calreticulin dual

stimulation. Furthermore, in high glucose-treated cardiomyocytes

and in human diabetic hearts, Jeyabal et al (57) also reported that ELAVL1 knockdown

reduced the expression level of NLRP3. Therefore, we hypothesized

that LINC00996 can increase the stability of NLRP3 mRNA by binding

to ELAVL1 in OV cells, thereby regulating sensitivity to

cuproptosis. The present study found that LINC00996, as a sponge,

can bind to hsa-miR-20a-5p, hsa-miR-106a-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p,

hsa-miR-17-5p, hsa-miR-34a-5p and hsa-miR-93-5p. Among these miRNA,

hsa-miR-106a-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p, hsa-miR-17-5p and hsa-miR-93-5p

can act on NLRP3 mRNA.

The present study has the following limitations:

First, it used a dataset of 378 patients with OV from TCGA to

explore a cuproptosis-related risk model, but further validation of

the risk model in cohorts from other institutions is needed to

ensure broader applicability. Second, while preliminary validation

was performed using cell experiments, further in vitro and

in vivo experiments are required to verify the interactions

and regulatory mechanisms.

In conclusion, the present study constructed a

prognostic risk model based on lncRNAs associated with cuproptosis

in OV and explored the regulatory mechanism of LINC00996 in

cuproptosis. The results provide new perspectives to assess the

role of cuproptosis in OV; however, more validation experiments are

required to further explore this role.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang

Province (grant no. LQ23H160033), Zhejiang Medical and Health

Science and Technology program (grant no. 2024KY116) and Key

R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2022C03013).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

BC and HW proposed the conception and implementation

of the study. BC and SY were responsible for data download and the

interpretation of data. BC was a major contributor in the

preparation of the manuscript. BC and HW performed the final

proofreading. BC, SY and HW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding SA, Fedewa

SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA and Jemal A:

Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:145–164.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S,

Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N and Chen W: Cancer statistics in China

and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin

Med J (Engl). 135:584–590. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chen S, Tang Y, Li Y, Huang M, Ma X, Wang

L, Wu Y, Wang Y, Fan W and Hou S: Design and application of prodrug

fluorescent probes for the detection of ovarian cancer cells and

release of anticancer drug. Biosens Bioelectron. 236:1154012023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li T, Wang X, Qin S, Chen B, Yi M and Zhou

J: Targeting PARP for the optimal immunotherapy efficiency in

gynecologic malignancies. Biomed Pharmacother. 162:1147122023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kahn R, Filippova O, Gordhandas S, An A,

Straubhar AM, Zivanovic O, Gardner GJ, O'Cearbhaill RE, Tew WP,

Grisham RN, et al: Ten-year conditional probability of survival for

patients with ovarian cancer: A new metric tailored to long-term

survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 169:85–90. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Singh N, Jayraj AS, Sarkar A, Mohan T,

Shukla A and Ghatage P: Pharmacotherapeutic treatment options for

recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother.

24:49–64. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J,

Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, Carey MS, Beale P,

Cervantes A, Kurzeder C, et al: A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in

ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 365:2484–2496. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bi R, Chen L, Huang M, Qiao Z, Li Z, Fan G

and Wang Y: Emerging strategies to overcome PARP inhibitors'

resistance in ovarian cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1879:1892212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ponting CP, Oliver PL and Reik W:

Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 136:629–641.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao J, Sun J, Shuai SC, Zhao Q and Shuai

J: Predicting potential interactions between lncRNAs and proteins

via combined graph auto-encoder methods. Brief Bioinform.

24:bbac5272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tang Y, Cheung BB, Atmadibrata B, Marshall

GM, Dinger ME, Liu PY and Liu T: The regulatory role of long

noncoding RNAs in cancer. Cancer Lett. 391:12–19. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yao ZT, Yang YM, Sun MM, He Y, Liao L,

Chen KS and Li B: New insights into the interplay between long

non-coding RNAs and RNA-binding proteins in cancer. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 42:117–140. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhou HL, Luo G, Wise JA and Lou H:

Regulation of alternative splicing by local histone modifications:

Potential roles for RNA-guided mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res.

42:701–713. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings

HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al: Long

non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer

metastasis. Nature. 464:1071–1076. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen XJ and An N: Long noncoding RNA ATB

promotes ovarian cancer tumorigenesis by mediating histone H3

lysine 27 trimethylation through binding to EZH2. J Cell Mol Med.

25:37–46. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL and Huarte M:

Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological

functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:96–118. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Quinn JJ and Chang HY: Unique features of

long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet.

17:47–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu SS, Li JS, Xue M, Wu WJ, Li X and Chen

W: LncRNA UCA1 participates in De Novo synthesis of guanine

nucleotides in bladder cancer by recruiting TWIST1 to increase

IMPDH1/2. Int J Biol Sci. 19:2599–2612. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Haas R, Ganem NS, Keshet A, Orlov A,

Fishman A and Lamm AT: A-to-I RNA editing affects lncRNAs

expression after heat shock. Genes (Basel). 9:6272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gordon MA, Babbs B, Cochrane DR, Bitler BG

and Richer JK: The long non-coding RNA MALAT1 promotes ovarian

cancer progression by regulating RBFOX2-mediated alternative

splicing. Mol Carcinog. 58:196–205. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ma B, Wang S, Wu W, Shan P, Chen Y, Meng

J, Xing L, Yun J, Hao L, Wang X, et al: Mechanisms of

circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA interactions and applications in disease and

drug research. Biomed Pharmacother. 162:1146722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhou J, Xu Y, Wang L, Cong Y, Huang K, Pan

X, Liu G, Li W, Dai C, Xu P and Jia X: LncRNA IDH1-AS1

sponges miR-518c-5p to suppress proliferation of epithelial ovarian

cancer cell by targeting RMB47. J Biomed Res. 38:51–65. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kalkavan H, Rühl S, Shaw JJP and Green DR:

Non-lethal outcomes of engaging regulated cell death pathways in

cancer. Nat Cancer. 6:795–806. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Deigendesch N, Zychlinsky A and Meissner

F: Copper regulates the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol.

200:1607–1617. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J

and Chen X: Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy.

Autophagy. 19:2175–2195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu S, Ge J, Chu Y, Cai S, Wu J, Gong A

and Zhang J: Identification of hub cuproptosis related genes and

immune cell infiltration characteristics in periodontitis. Front

Immunol. 14:11646672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun M, Zhan N, Yang Z, Zhang X, Zhang J,

Peng L, Luo Y, Lin L, Lou Y, You D, et al: Cuproptosis-related

lncRNA JPX regulates malignant cell behavior and epithelial-immune

interaction in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma via

miR-193b-3p/PLAU axis. Int J Oral Sci. 16:632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhou G, Chen C, Wu H, Lin J, Liu H, Tao Y

and Huang B: LncRNA AP000842.3 triggers the malignant progression

of prostate cancer by regulating cuproptosis related gene NFAT5.

Technol Cancer Res Treat. 23:153303382412555852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bai Y, Zhang Q, Liu F and Quan J: A novel

cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature predicts the prognosis and

immune landscape in bladder cancer. Front Immunol. 13:10274492022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Huang H, Chen G, Zhang Z, Wu G, Zhang Z,

Yu A, Wang J, Quan C, Li Y and Zhou M: Deciphering the role of

cuproptosis-related lncRNAs in shaping the lung cancer immune

microenvironment: A comprehensive prognostic model. J Cell Mol Med.

28:e185192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu H, Lu X, Hu Y, Baatarbolat J, Zhang Z,

Liang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Lv H and Jin X: Biomimic nanodrugs

overcome tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment to enhance

cuproptosis/chemodynamic-induced cancer immunotherapy. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24111222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Guan M, Cheng K, Xie XT, Li Y, Ma MW,

Zhang B, Chen S, Chen W, Liu B, Fan JX and Zhao YD: Regulating

copper homeostasis of tumor cells to promote cuproptosis for

enhancing breast cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 15:100602024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lu X, Chen X, Lin C, Yi Y, Zhao S, Zhu B,

Deng W, Wang X, Xie Z, Rao S, et al: Elesclomol loaded copper oxide

nanoplatform triggers cuproptosis to enhance antitumor

immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23099842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shen Z, Li X, Hu Z, Yang Y, Yang Z, Li S,

Zhou Y, Ma J, Li H, Liu X, et al: Linc00996 is a favorable

prognostic factor in LUAD: Results from bioinformatics analysis and

experimental validation. Front Genet. 13:9329732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ge H, Yan Y, Wu D, Huang Y and Tian F:

Potential role of LINC00996 in colorectal cancer: a study based on

data mining and bioinformatics. Onco Targets Ther. 11:4845–4855.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, Kumar L and

Friedlander M: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum:

2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 155 (Suppl):61–85. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kawase K, Kawashima S, Nagasaki J, Inozume

T, Tanji E, Kawazu M, Hanazawa T and Togashi Y: High expression of

MHC class I overcomes cancer immunotherapy resistance due to IFNγ

signaling pathway defects. Cancer Immunol Res. 11:895–908. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hiltner T, Szörenyi N, Kohlruss M,

Hapfelmeier A, Herz AL, Slotta-Huspenina J, Jesinghaus M, Novotny

A, Lange S, Ott K, et al: Significant tumor regression after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer, but poor survival of

the patient? Role of MHC class I alterations. Cancers (Basel).

15:7712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Colbert JD, Cruz FM, Baer CE and Rock KL:

Tetraspanin-5-mediated MHC class I clustering is required for

optimal CD8 T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

119:e21221881192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Luda KM, Longo J, Kitchen-Goosen SM,

Duimstra LR, Ma EH, Watson MJ, Oswald BM, Fu Z, Madaj Z, Kupai A,

et al: Ketolysis drives CD8+ T cell effector function through

effects on histone acetylation. Immunity. 56:2021–2035.e8. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Stanifer ML, Guo C, Doldan P and Boulant

S: Importance of type I and III interferons at respiratory and

intestinal barrier surfaces. Front Immunol. 11:6086452020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

O'Day S, Gonzalez R, Lawson D, Weber R,

Hutchins L, Anderson C, Haddad J, Kong S, Williams A and Jacobson

E: Phase II, randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of weekly

elesclomol plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone for stage IV

metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 27:5452–5458. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Guo CJ, Ma XK, Xing YH, Zheng CC, Xu YF,

Shan L, Zhang J, Wang S, Wang Y, Carmichael GG, et al: Distinct

processing of lncRNAs contributes to non-conserved functions in

stem cells. Cell. 181:621–636.e22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang Q, Li G, Ma X, Liu L, Liu J, Yin Y,

Li H, Chen Y, Zhang X, Zhang L, et al: LncRNA TINCR impairs the

efficacy of immunotherapy against breast cancer by recruiting DNMT1

and downregulating MiR-199a-5p via the STAT1-TINCR-USP20-PD-L1

axis. Cell Death Dis. 14:762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Priyanka P, Sharma M, Das S and Saxena S:

The lncRNA HMS recruits RNA-binding protein HuR to stabilize the

3′-UTR of HOXC10 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 297:1009972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Latorre E, Carelli S, Raimondi I,

D'Agostino V, Castiglioni I, Zucal C, Moro G, Luciani A, Ghilardi

G, Monti E, et al: The ribonucleic complex HuR-MALAT1 represses

CD133 expression and suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition

in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 76:2626–2636. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Brennan CM and Steitz JA: HuR and mRNA

stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 58:266–277. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Fu XD: RNA editing: New roles in feedback

and feedforward control. Cell Res. 33:495–496. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Hildebrandt RP, Moss KR, Janusz-Kaminska

A, Knudson LA, Denes LT, Saxena T, Boggupalli DP, Li Z, Lin K,

Bassell GJ, et al: Muscleblind-like proteins use modular domains to

localize RNAs by riding kinesins and docking to membranes. Nat

Commun. 14:34272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

González ÀL, Fernández-Remacha D, Borrell

JI, Teixidó J and Estrada-Tejedor R: Cognate RNA-binding modes by

the alternative-splicing regulator MBNL1 inferred from molecular

dynamics. Int J Mol Sci. 23:161472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu Y, Wei W, Wang Y, Wan C, Bai Y, Sun X,

Ma J and Zheng F: TNF-α/calreticulin dual signaling induced NLRP3

inflammasome activation associated with HuR nucleocytoplasmic

shuttling in rheumatoid arthritis. Inflamm Res. 68:597–611. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Jeyabal P, Thandavarayan RA, Joladarashi

D, Suresh Babu S, Krishnamurthy S, Bhimaraj A, Youker KA, Kishore R

and Krishnamurthy P: MicroRNA-9 inhibits hyperglycemia-induced

pyroptosis in human ventricular cardiomyocytes by targeting ELAVL1.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 471:423–429. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|