Introduction

Despite significant improvements in colorectal

cancer (CRC) treatment, especially in countries with long-standing

screening programs (1), CRC is

still the third most frequently diagnosed oncologic disease,

ranking second among causes of cancer-related mortality (2,3). A

further rise in CRC incidence is predicted. The burden of CRC is

attributed to increasing early-onset CRC, ageing of the population

and a lifestyle shift toward a Western diet combined with low

physical activity (3,4).

Interestingly, the age-standardized incidence of CRC

is consistently higher in males compared to females, including CRC

cases with early onset (5). CRC is

more often diagnosed in the proximal colon in women, whereas distal

anatomical CRC sites are detected more often in males (6–8). The

most pronounced difference is observed in the incidence of rectal

cancer, which is in 75% of cases diagnosed in males (2,3,9).

Among the possible reasons for this phenomenon are

an unfavourable diet, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking and low

physical activity (10). These

factors influence CRC progression differently depending on the sex

of the patient and tumour localisation (11–13).

Although sex hormones have been implicated in the

generation of differences in CRC prevalence between males and

females, their precise role has not been completely elucidated

(7,8,14). In

particular, it is assumed that the most potent oestrogen,

17β-oestradiol (E2), influences CRC progression (8,15,16).

E2 signalling is mediated predominantly by two types

of nuclear receptors, ESR1 and ESR2, and the G protein-coupled

membrane receptor Gper1 (previous symbols GPER, GPR30) (15). Among the ligands of ESR1, ESR2 and

Gper1 are, in addition to oestrogens, tamoxifen, raloxifene,

bisphenols, dioxins, phthalates, quercetin, genistein, resveratrol

and others (17,18). The ligands mentioned above can

usually activate both nuclear and membrane-bound receptors,

although their affinity can differ (19). Gper1 has a lower affinity for E2

than ESR1 and ESR2 (20). Direct

binding of E2 to Gper1 was even questioned recently (21,22).

However, there is substantial in vivo and in vitro

evidence that Gper1 is involved in E2-mediated regulation (23). Recently, the binding of E2 to Gper1

was confirmed, and aldosterone was also proposed as a Gper1 agonist

(24).

Nuclear E2 receptors exert most of their effects via

transcriptional gene regulation. ESR1 and ESR2 activate thousands

of genes overlapping by 30% via a specific DNA sequence called

oestrogen response element (ERE) (25).

Compared to nuclear E2 receptors, Gper1 affects

intracellular processes much faster thanks to the prompt activation

of several intracellular signalling pathways. Signalling mediated

by Gper1 includes an increase in cAMP synthesis and consequent

activation of protein kinase A, Src-like nonreceptor tyrosine

kinase (Src) and sphingosine kinase (SphK). Src and SphK can

contribute to the activation of epidermal growth factor receptors

(EGFR). Gper1 signalling can also lead to activation of protein

kinase C and calcium mobilisation (17). Among Gper1-driven regulatory

pathways also belongs Gper1/HIFα activation of NOTCH and consequent

induction of VEGF transcription (26) and some others (18). Tissue-specific distribution and/or

changes in the tissue-specific distribution of E2 receptors in

disease can influence E2 signalling and facilitate its oncostatic

or tumour suppressor effects (17,18,25).

Epidemiological studies of patients using hormone

response therapy (HRT) implicated protective role of E2 in respect

to CRC incidence. It was shown that oestrogen/progestin HRT is

negatively associated with the risk of CRC (27). Similarly, the incidence of CRC in

postmenopausal women exposed to E2 HRT was lower compared to women

of the same age without HRT (28).

Other studies later strengthened the evidence of E2′s protective

role regarding CRC incidence (15,16,29,30).

It is of interest that patients with high levels of endogenous

circulating E2 (31) and those

exposed to E2 therapy whilst diagnosed with CRC demonstrated a

worse disease prognosis (32). On

the other hand, Mori et al (33) did not confirm the association of

high circulating E2 levels with increased incidence and/or

prognosis of CRC in postmenopausal women.

Most of the beneficial effects of E2 for patients

are attributed to ESR2 (15,34–37),

which is far more abundant in the gastrointestinal tract compared

to ESR1 (38–40). The beneficial E2 effect mediated via

ESR2 receptors was proven with the use of several in vivo

experimental models. Apcmin/+mice bearing a mutation in

the Apc gene are prone to developing multiple intestinal

tumours. Ovariectomy (OVX) significantly increased the number of

adenomas detected in the gut compared to control, and this effect

was reversed by E2 administration. E2 treatment was also

accompanied by an increase in ESR2 expression in the intestine

(41). ESR2 deficiency in

Apcmin/+ mice was associated with a higher adenoma

number compared to control (42).

The protective role of E2 executed via ESR2 was also demonstrated

in OVX mice where tumorigenesis was induced by azoxymethane (AOM)

(43), by combined treatment of AOM

and dextran sulphate sodium (44,45)

and in immunodeficient mice implanted with SW480 cells

overexpressing ESR2 (46).

Interestingly, the expression of Gper1 mRNA exceeds

that of ESR2 in healthy gut tissue (40,47).

Similarly, it is the predominant E2 receptor in several colorectal

cell lines (48). Despite that, the

role of the membrane receptor Gper1 in E2-mediated effects on

cancer progression has not been completely elucidated.

The tumour suppressor as well as the oncogenic role

of Gper1 has been demonstrated for several types of tissues.

Perhaps the most promising results were achieved in melanoma

treatment. However, in most cancer types, including CRC, the role

of Gper1 remains inconclusive (17,49,50).

It was shown that G-1, an agonist of Gper1, inhibits

the upregulation of JUN oncogene expression in HT29 cells (48). G-1 administered at a concentration

of 1 µM significantly inhibited the proliferation of HCT-116 and

SW480 cells, increased the number of cells in the G2/M phase and

stimulated apoptosis. The decrease in cell viability induced by G-1

was prevented by the administration of the ROS scavenger NAC.

Growth of tumour xenografts in nude mice was inhibited by G-1

administration (51).

On the other hand, Gper1 silencing prevented

chromosomal instability induced by diethylstilbestrol and the

occurrence of supernumerary centrosomes in HCT116 and control CCD

841 CoN cell lines. In these cell lines, Gper1 activation led to

the presence of multipolar mitotic spindles, an increased number of

cells with lagging chromosomes and aneuploidy. Interestingly,

manipulation of Gper1 levels did not influence the rate of

proliferation and cell cycle distribution under in vitro

conditions (52). The oncogenic

role of Gper1 was confirmed in HT-29 cells as Gper1 silencing

prevented an E2-induced decrease in ATM. Under normoxic conditions,

Gper1 activation caused down regulation of VEGF while the opposite

effect was observed in a hypoxic microenvironment and prevented by

Gper1 silencing. Under hypoxic conditions, Gper1 mediated an

E2-induced increase in HT-29 and DLD1 cell migration (53). E2 and its agonist G-1, via Gper1,

induced the expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN), which can

promote CRC progression. FASN upregulation is executed by the

epidermal growth factor receptor EGFR/ERK/AP1 pathway (54). Oncogenic properties of Gper1 were

demonstrated in the CRC cell lines COLO205 and SW480 as the Gper1

antagonist G15 was able to reverse the effect of the E2-related

endocrine disruptor nonylphenol, which induced proliferation, the

expression of cyclin D1, c-myc and ERK1/2. Administration of G15

also inhibited the growth of colon carcinoma xenografts in mice

(55). Disagreement in the results

of performed studies can be partly related to different

concentrations of G-1 used in experiments. In addition to

experimental designs, the biological context seems to be of special

importance in effects mediated by Gper1 (17,34,48,52,53).

In human studies, the results are also inconclusive.

Up- as well as down-regulated Gper1 expression in CRC tissue was

indicated (17), e.g. a strong

trend toward increased Gper1 levels in CRC cancer tissue compared

to adjacent tissue was reported by Gilligan et al (56) while down-regulated expression of

Gper1 was reported by Liu et al (51). High expression of Gper1 was

associated with better survival compared to low expression

(51); by contrast, low expression

of Gper1 was associated with better survival compared to high

expression (56). High expression

of Gper1 was also associated with worse survival by Bustos et

al (53) and Abancens et

al (48) but only in females in

stages 3–4 of CRC. Worse survival of CRC patients exhibiting high

expression of Gper1 is indicated by the Human Protein Atlas

(47).

As there is evidence suggesting that manipulation of

E2 signalling could be effective in clinical use, several agonists

and antagonists of nuclear and Gper1 receptors have been developed,

and some of them have been clinically tested (18,25,57).

The most promising results were obtained in the clinical study

NCT04130516 evaluating the effects of Gper1 agonist LNS8801 that

proved beneficial effects of Gper1 signalling in patients diagnosed

with cutaneous (58) and uveal

(59) melanoma. However, it was

implied that G-1 can cause effects independent of Gper1 signalling

(60–65). Interestingly, several clinically

approved antagonists of nuclear E2 receptors also act as Gper1

agonists (18).

CRC is among the most frequently diagnosed oncologic

diseases worldwide. To facilitate novel CRC treatment strategies,

we focused on Gper1 functioning in CRC tumours to define the

conditions under which Gper1 upregulation could be beneficial for

patients.

Despite ongoing clinical trials aimed at the

manipulation of Gper1 signalling in solid cancers, the involvement

of Gper1 in the generation of sex-dependent CRC incidence is

largely unknown. Similarly, the biological context that determines

the effect of Gper1 has not been described sufficiently. Therefore,

the present study is aimed to analyse the abundance of Gper1 in

healthy and tumour tissues of males and females diagnosed with CRC

according to disease stage and survival. Mutation in p53 has been

identified in more than 50% of CRC patients and at a higher

frequency in males compared to females (66). Therefore, using the CRC cell lines

LoVo and DLD1, which differ in p53 functionality (67), we tested the hypothesis that the

effects of Gper1 depend on the presence of wild-type p53.

Materials and methods

Tumour and adjacent tissues were obtained in

cooperation with the First Surgery Department, University Hospital,

Comenius University, Bratislava. The study included patients who

had to undergo surgery for CRC treatment (for details see Table SI) and agreed to sign an informed

consent. Patients were not subjected to any CRC treatment before

surgery and during hospitalization were exposed to a standard

hospital practice with lights on from 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Surgery was performed in the morning hours (before noon). Adjacent

tissues were collected ≥10 cm proximally and ≥2 cm distally from

the tumour. After tissue excision, samples were promptly frozen in

liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until analysis. The

experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Comenius University in Bratislava (ECH 19001).

To extract mRNA from tissues and cells, RNAzol RT

(Molecular Research Centre) was used as described previously

(40). One microgram of RNA

template from tissues and 0.02 µg from cells was used to synthesize

cDNA with the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System and random

hexamers (Promega), according to the manufacturer's

instructions.

To analyse gene expression, the QuantiTect SYBR

Green kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used. Real-time PCR was performed

with the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

The PCR conditions were activation of hot start polymerase at 95°C

for 15 min followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 15 sec, 53°C for 30

sec and 72°C for 30 sec. As a last step of PCR, samples were

subjected to melting curve analysis. The sequences of primers for

the amplification of particular genes are provided in Table SII. The expression of nuclear

u6 mRNA was used for normalisation.

The human colorectal carcinoma cell lines DLD1 and

LoVo obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were

used to reveal how gper1 silencing influences cell migration

and metabolism. DLD1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 GlutaMax

medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and LoVo cells were

incubated in F-12K medium (Bioconcept). Both cell lines were

supplemented with 2% or 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Biosera)

depending on the experiment; 2% FBS supplementation was used for

the scratch assay while 10% FBS was used for the MTS test. The

culture medium also contained penicillin (50 U/ml) (Gibco),

streptomycin (50 µl/ml) (Gibco, USA) and ampicillin (50 µg/ml)

(Oasis-lab). All experiments were performed in a biological

Celculture® Incubator CCL-050B-8 (Esco Medical) with a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. The

cells were cultured in 96-well plates coated with 1% sterile

gelatine.

To test the effect of gper1 silencing,

DharmaFECT 1 reagent was used to transfect cells with siGENOME

Human Gper1siRNA-SMART pool or siGENOME non-targeting siRNA Pool #2

(Horizon) at a concentration of 100 nM.

The effect of siGper1 on wound healing was

determined by scratch assay performed when the cell culture reached

a confluence of 80–90% with the use of a 10-ul sterile tip. Images

were taken immediately after scratch and later as indicated in the

figure legends with the use of an inverted fluorescence microscope

NIB-100F (Nanjing Jiangnan Novel Optics Co., Ltd.) and BEL Capture

3.2 software (BEL Engineering s.r.l.). Wound closure was evaluated

with ImageJ software (68).

The rate of metabolism was measured by MTS test

according to the manufacturer's instructions (CellTiter 96 AQueous

Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega) employing a modified tetrazolium

compound to produce water-soluble formazan. The absorbance was

measured at 490 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Epoch, Agilent

Technologies, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate Gper1 mRNA expression in human samples,

the cohort was split into three groups according to TNM

classification. Group 1 included distant metastasis-free patients

without nodal involvement (T1-4N0M0), group 2 consisted of patients

with nodal involvement and without distant metastases (T3-4N1-2M0)

and the 3rd group was composed of patients with distant

metastases (T3-4N0-2M1). Gene expression between three groups was

compared by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

To compare E2 receptor expression between two

groups, a Student's paired t-test was used. ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to compare the

expression of three types of oestrogen receptors (ESR1, ESR2 and

Gper1) in human tissues and cells.

To analyse Gper1 mRNA expression with respect to

overall survival, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve and a log-rank test

were performed. Values were split according to the median; high

expression > median, low expression ≤ median. The starting point

for the log-rank test was the day of the surgery. The association

of Gper1 and VEGFA mRNA expression was analysed by correlation

analysis.

Data are provided as mean ± standard error of the

mean (SEM) in relative units (r.u.). The threshold for significance

for all statistical tests was set at P<0.05. Statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software,

Inc.).

Results

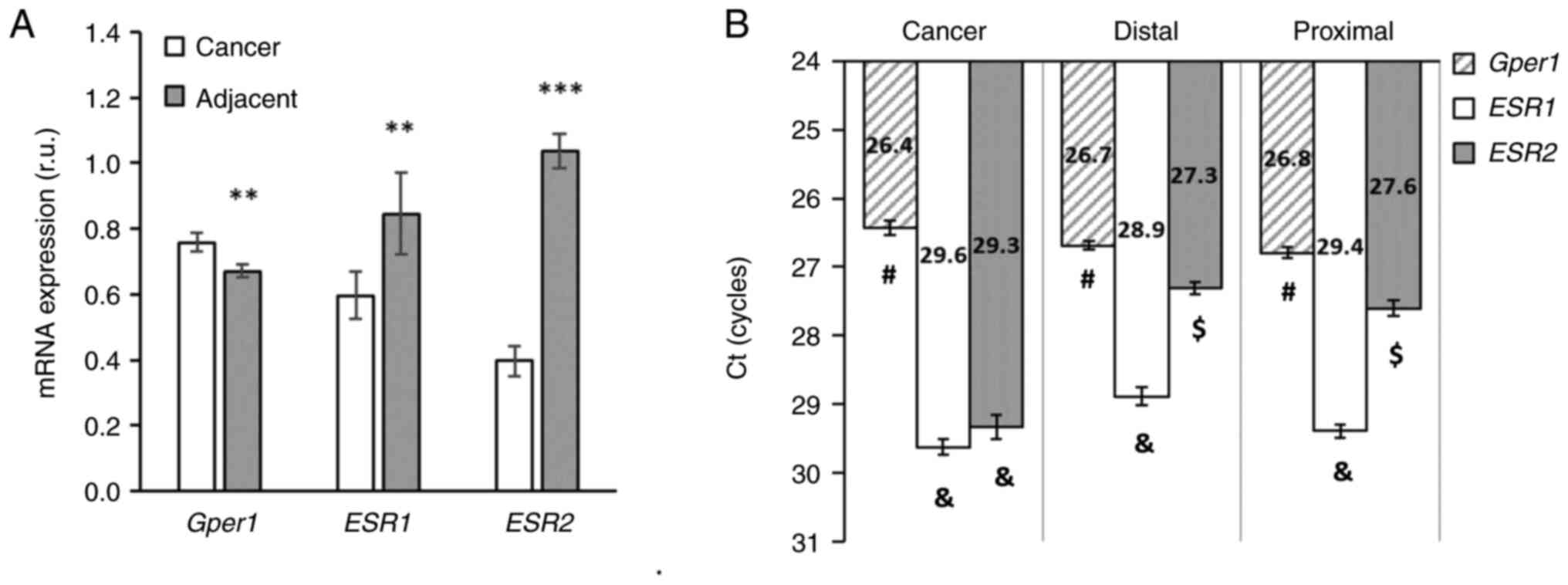

E2 receptors show robust differences in expression

between colorectal tumours and adjacent tissues. In tumour tissue,

the expression of gper1 was higher compared to adjacent

tissue, whereas the opposite pattern was observed in levels of

nuclear E2 receptors. The expression of esr1 and esr2

was significantly lower in cancer tissue compared to adjacent

tissues (Fig. 1A). The expression

of gper1 was higher in cancer tissue compared to adjacent

distal and proximal tissues (Fig.

1B). Comparison of the absolute level of expression based on

the threshold value of the PCR revealed that gper1 is far

most abundant in cancer as well as in the adjacent tissues compared

to esr1 and esr2 mRNA levels (Fig. 1B).

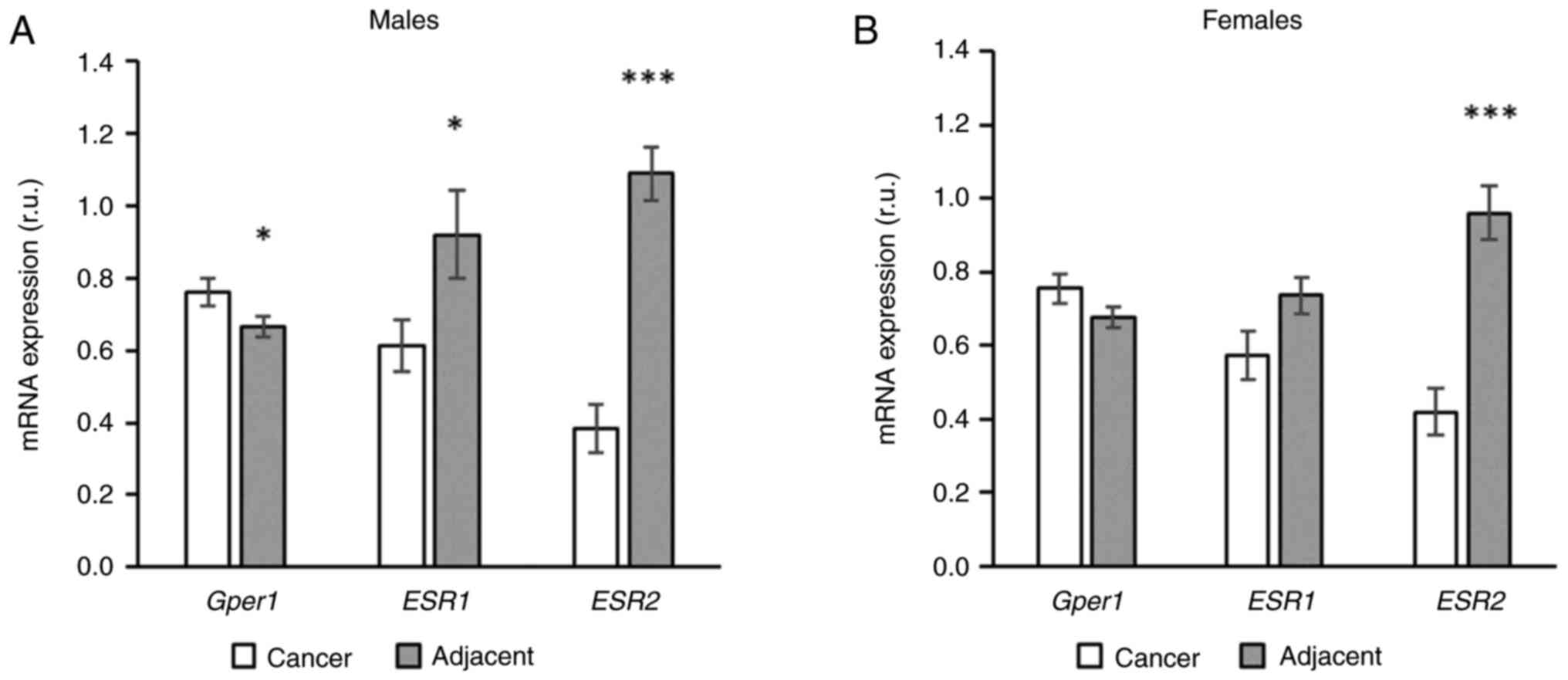

The expression of gper1 was higher in cancer

tissue compared to adjacent tissue in males, but in females this

pattern was observed only as a non-significant trend (Fig. 2). The expression of esr1 was

higher in the adjacent compared to cancer tissue and this

difference, again, achieved a level of significance only in males

(Fig. 2). The most robust

difference in expression between cancer and adjacent tissue was

observed in the expression of esr2. Unlike other receptors,

this pattern was present in both sexes (Fig. 2).

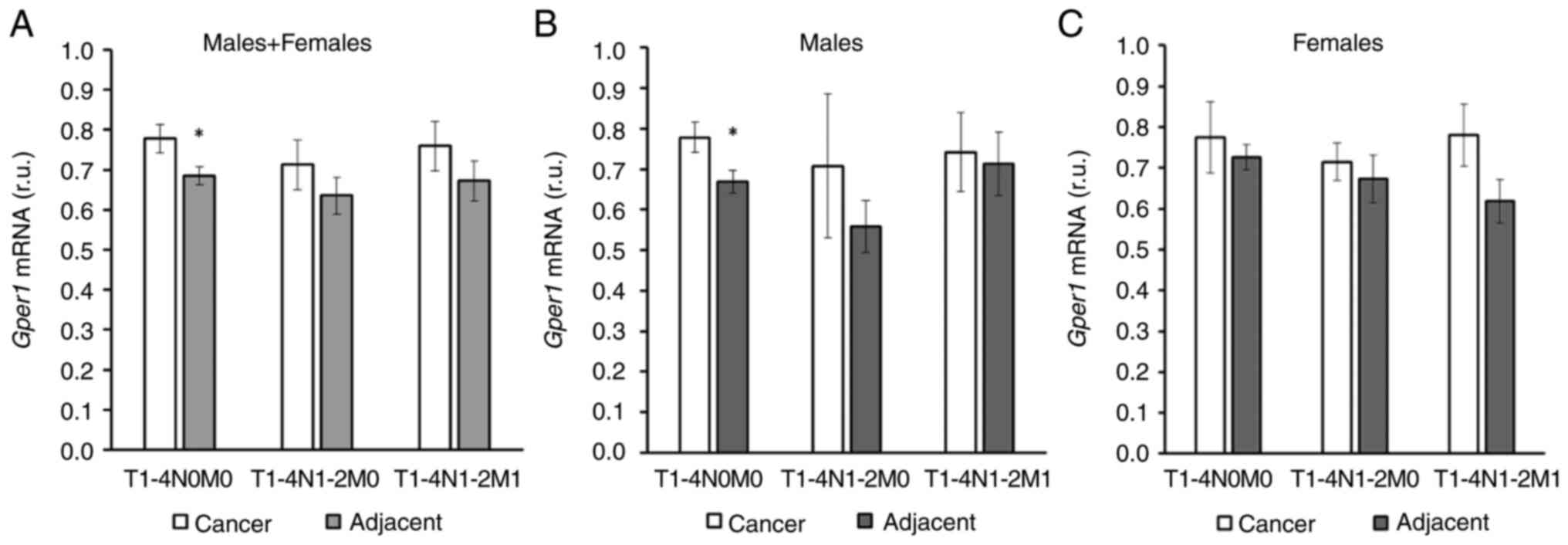

In the whole cohort an increase in gper1

expression in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissue was

observed in patients without nodal involvement and distal

metastases (Fig. 3A). However, when

the cohort was split into male and female patients, this difference

was observed only in males (Fig. 3B and

C). gper1 expression did not differ between cancer and

adjacent tissues in more advanced stages of disease (Fig. 3).

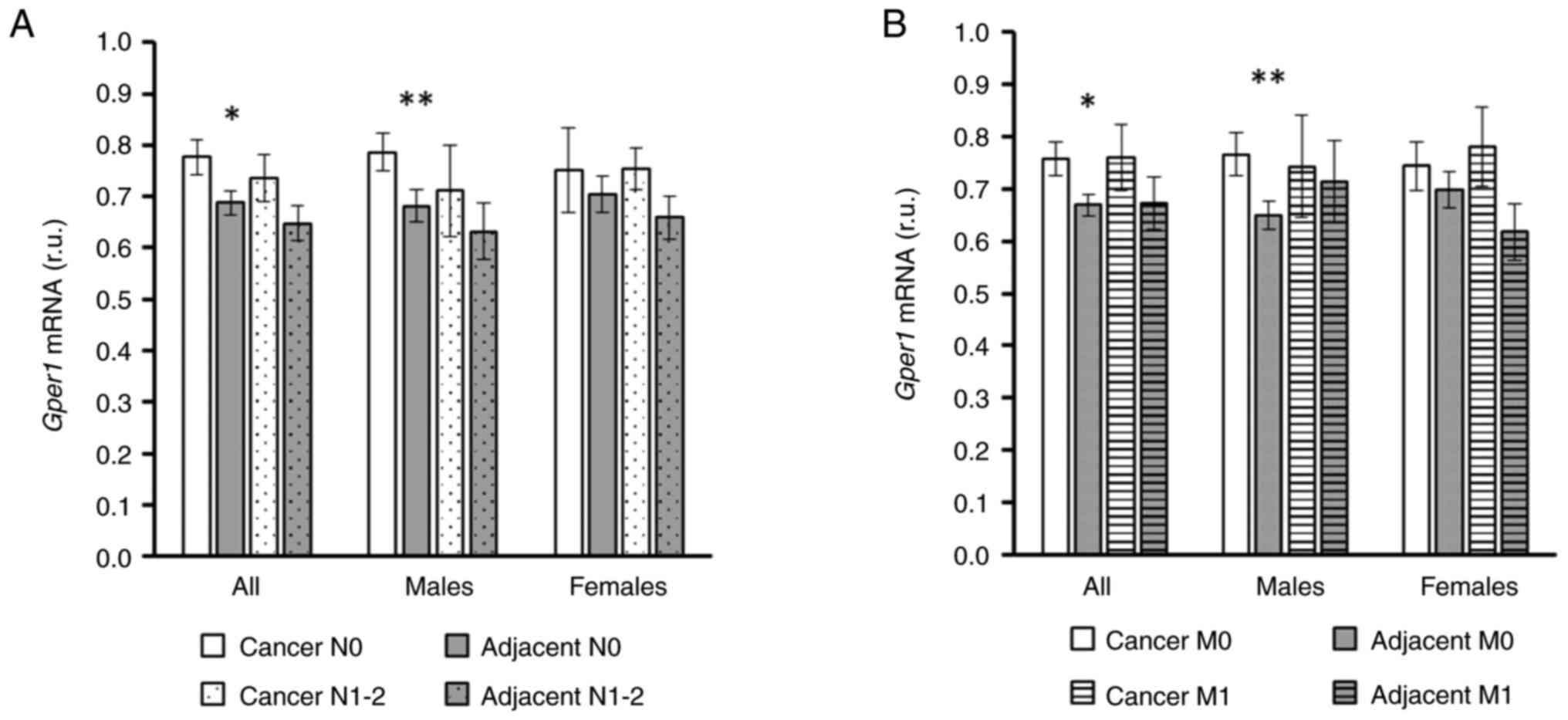

When the cohort was split according to nodal

involvement only (without considering TNM staging as a whole) the

sex-dependent difference in gper1 expression became even

more pronounced, and there was a highly significant increase in

gper1 expression in cancer tissue compared to adjacent

tissue in males without nodal involvement (Fig. 4A). Similarly, male patients without

distant metastases displayed a pronounced increase in gper1

expression in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissue that was

not observed in females (Fig.

4B).

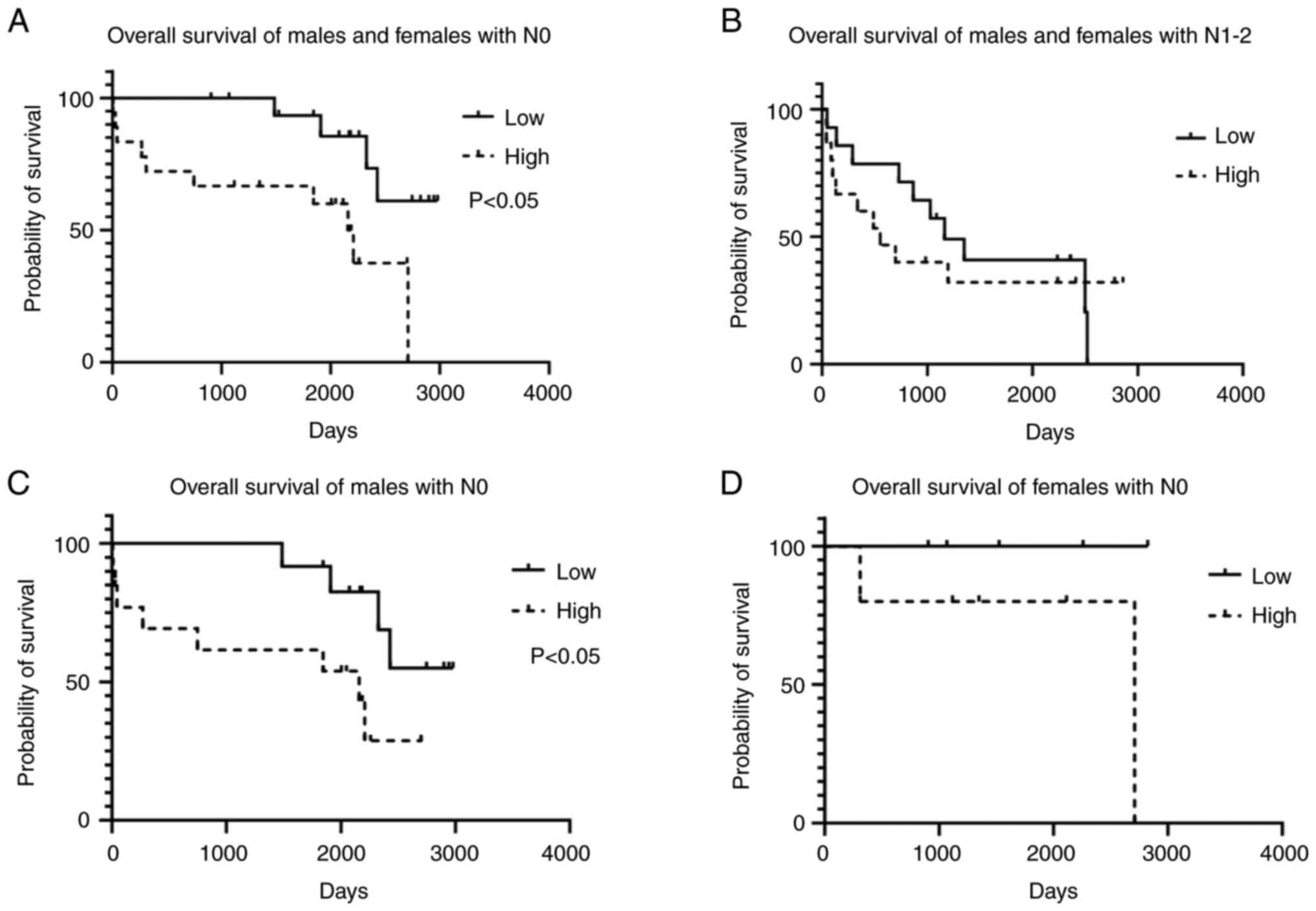

In accordance with the sex-dependent expression of

gper1 in CRC patients, the association of overall survival

and gper1 expression exerted a sex-dependent pattern. In the

whole cohort, better survival was correlated with low gper1

expression in patients without nodal involvement (Fig. 5A) but not in patients in higher

stages of disease (Fig. 5B). When

the cohort was split according to sex, a log-rank test revealed

that gper1 association with survival was generated by the

male subcohort (Fig. 5C). In

females the correlation between survival and gper1

expression did not reach significance (Fig. 5D).

In human samples from our cohort, the expression of

gper1 significantly correlated with the mRNA expression of

VEGFA in cancer tissue. This relationship was not observed in

proximal and distal adjacent tissues (Fig. S1).

Transfection of siRNA targeting gper1

expression successfully inhibited Gper1 mRNA expression in DLD1 as

well as LoVo cells compared to control (Fig. S2A and B, respectively).

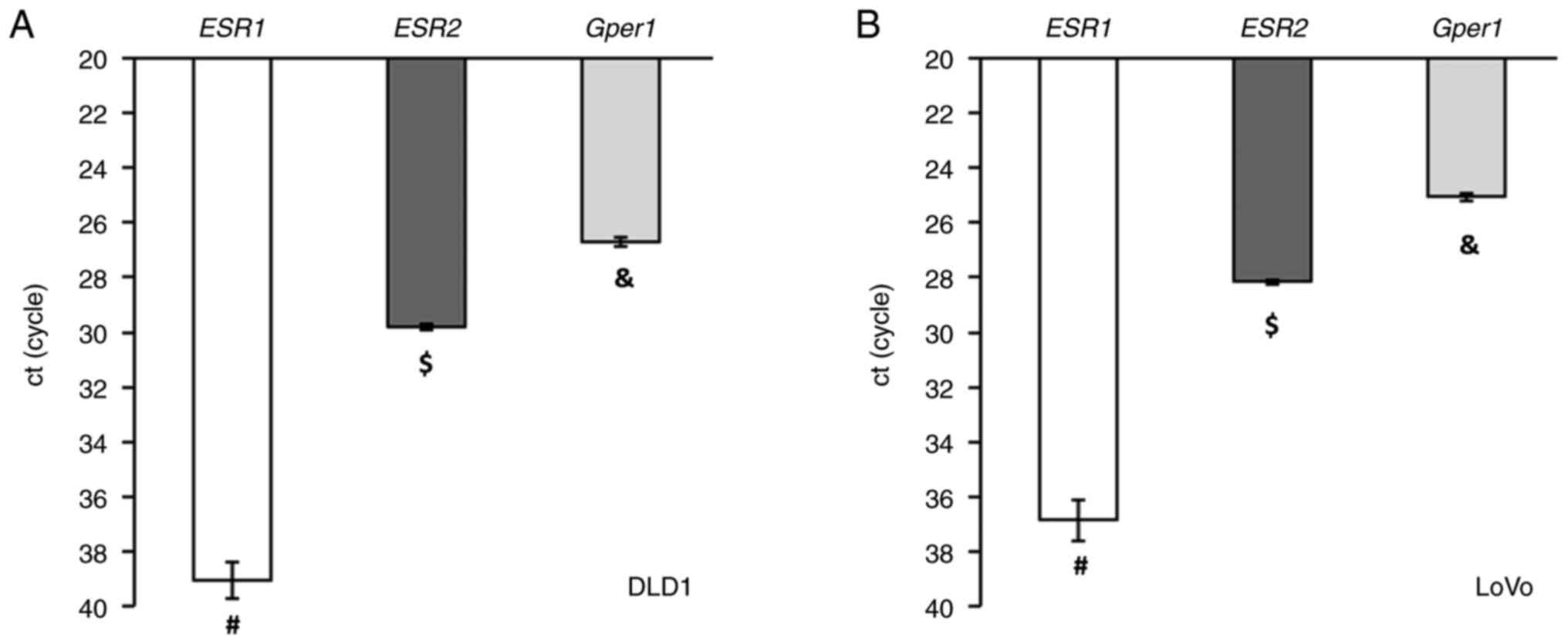

The distribution of E2 receptors in CRC cell lines

LoVo and DLD1 resembled that of human cancer tissue. The expression

of the membrane gper1 receptor was much higher compared to

mRNA levels of nuclear E2 receptors, and the expression of ESR1

mRNA was nearly undetectable (Fig.

6).

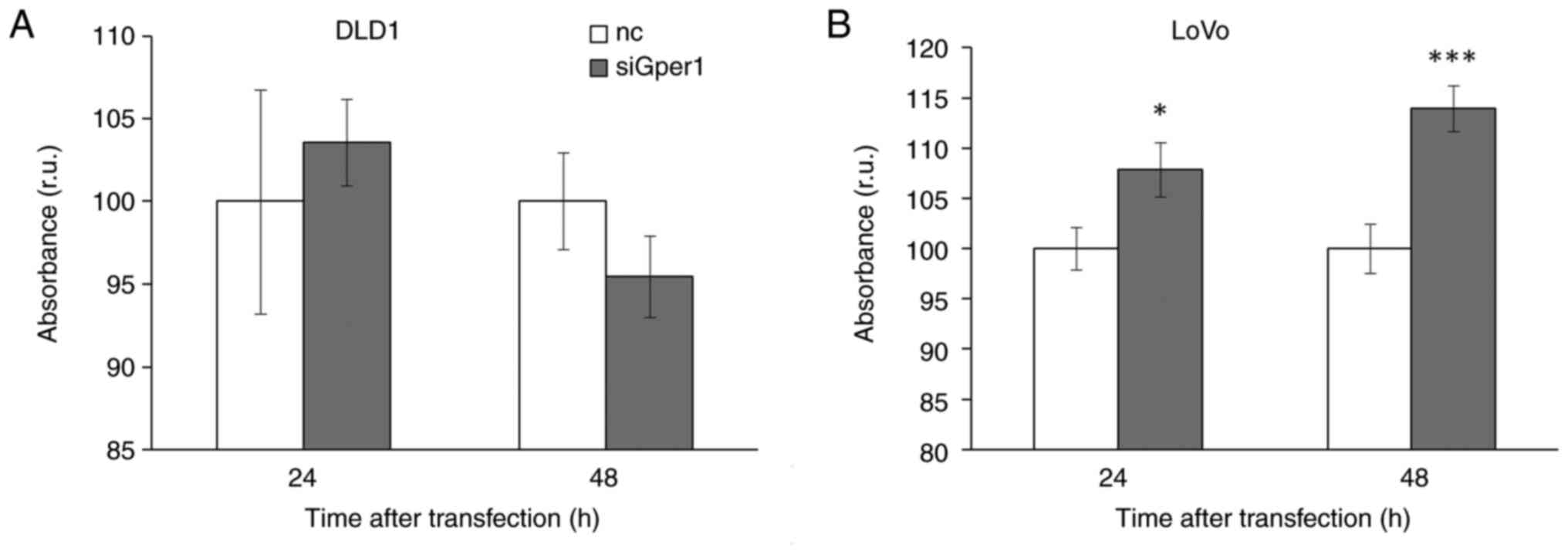

Silencing of gper1 expression significantly

stimulated metabolism in LoVo cells in a time-dependent manner that

implicates the tumour-suppressor capacity of Gper1. In DLD1 cells

we did not observe this effect (Fig.

7).

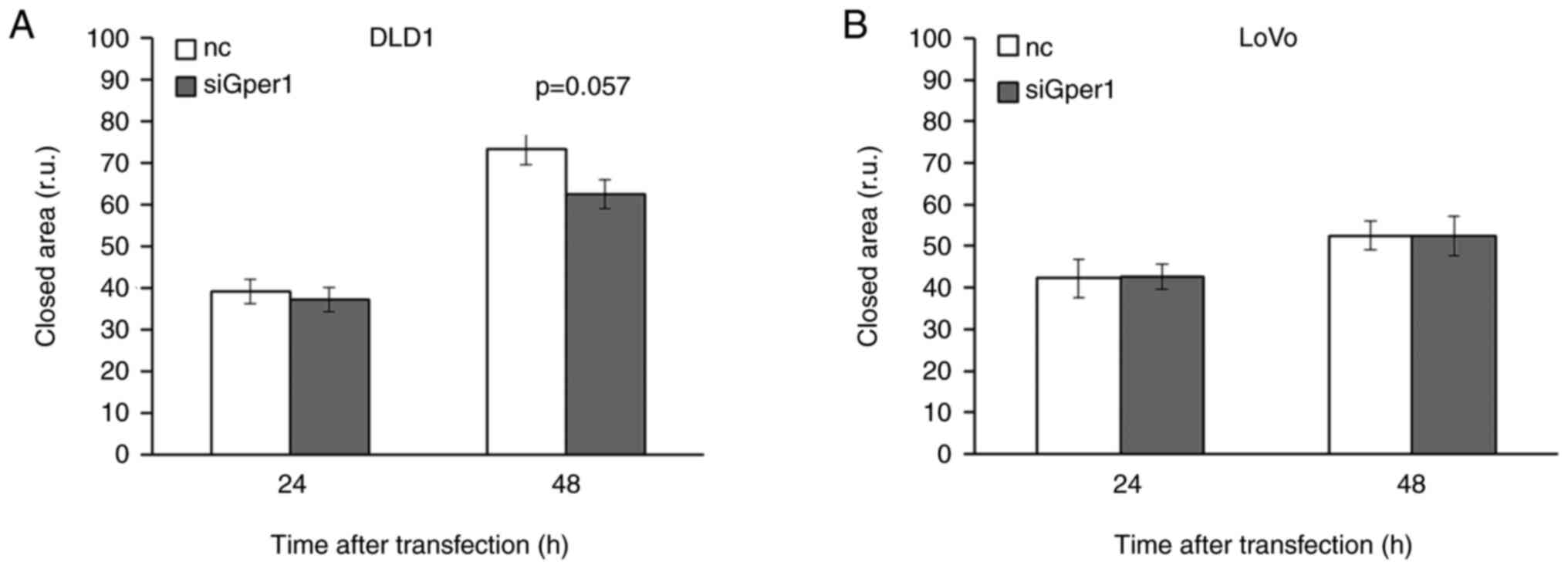

Evaluation by the scratch test demonstrated a

time-dependent decrease in wound closure in DLD1 cells with

silenced Gper1 expression compared to control. Whereas 24h after

Gper1 silencing there was no effect on the rate of wound closure,

48 h after transfection the width of the closed area was different

between control and transfected cells with P=0.057 (Fig. 8A). Inhibition of wound healing by

Gper1 silencing implicates the oncogenic potential of Gper1 in DLD1

cells.

Unlike in DLD1 cells, the administration of siRNA

interfering with Gper1 expression did not influence the rate of

wound closure in LoVo cells (Fig.

8B).

The expression of p53 mRNA did not differ

significantly between DLD1 and LoVo cells. However, as DLD1 cells

generate a mutated form of the p53 protein, expression of

p53-inducible gene p21 was significantly lover in DLD1 cells

compared to LoVo cells (Fig.

S3).

The expression of gper1 and tp53

showed a significant correlation in males (A) but not in females

(B) undergoing surgery for CRC treatment (Fig. S4) (TCGA, Colorectal Adenocarcinoma,

Nature 2012).

Discussion

The relative ratio of E2 receptors in CRC tissue

undergoes remodelling. While the expression of nuclear E2 receptors

decreases in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissue, the

opposite pattern is observed in Gper1 mRNA expression. Therefore,

Gper1 is by far the most abundant E2 receptor in the CRC tumour

followed by the ESR2 and very low ESR1 mRNA expression. The

increase in gper1 expression in tumours is most pronounced

in males in the lower stages of disease. A higher expression of

Gper1 mRNA was associated with worse survival in the whole cohort

and in males without metastases in nodes. This dependency was not

detected in males with nodal involvement and females. We suppose

that sex-dependent differences in E2 receptor expression can

contribute to sex-dependent features of CRC progression.

In accordance with our data, Gilligan et al

(56) showed an increase in Gper1

expression in CRC tissue compared to adjacent tissue. Several

factors can induce an increase in Gper1 mRNA levels in cancer

tissue. Firstly, Gper1 belongs to HIF-1 targeted genes that are

expressed in response to hypoxia (69). The stimulatory effect of hypoxia on

Gper1 mRNA expression was also demonstrated in the colon cancer

cell line HT-29 and the rectal cancer cell line C80 (53). The oncogenic role of Gper1 was

implicated as it was demonstrated that Gper1 cooperated with HIF-1α

in the activation of VEGF expression in hypoxia (26,70).

In line with this finding, we detected a positive correlation

between Gper1 and VEGFA mRNA expression in cancer but not in the

adjacent tissues.

We observed a decrease in ESR2 mRNA expression in

CRC tumours compared to proximal and distal parts of the gut, which

is consistent with previous studies (71–77)

that reported lower ESR2 expression in CRC tissue compared to

adjacent tissues at the protein and mRNA levels.

According to our results, the expression of ESR1

mRNA is lower in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissues, and

this difference is more pronounced in males than in females.

Previously, a decrease was observed in ESR1 expression in

colorectal cancer tissue, which was attributed to CpG island

methylation (78). No significant

differences between cancer and adjacent tissue have also been

reported (38). According to Jiang

et al (79), the expression

of the dominant ESR1 isoform does not differ in its mRNA levels

between tumour and matched normal tissues. However, the ER-α46

isoform that shares most of its sequence with the dominant isoform

was down-regulated in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissue. On

the other hand, an increase in esr1 mRNA in cancer compared

to adjacent healthy tissue has been reported lately (80). Although data referring to ESR1

expression in CRC seem to be inconclusive, there is a consensus on

the decrease in nuclear ESR2 and increase in Gper1 expression in

cancer compared to adjacent tissue.

The expression of all three types of receptors in

one set of samples has rarely been studied. There is a strong

evidence that the expression of ESR2 in the gut is more abundant

compared to that of ESR1 (71,76,81).

The assumption that ESR2 is the predominant form of the E2 receptor

in the gut can, to some extent, be caused by later identification

of the Gper1 receptor compared to nuclear E2 receptors (82). Previously, it has been shown that

the expression of Gper1 mRNA is more abundant compared to that of

both ESR1 and ESR2 in the rat colon (40). According to datasets available from

the Human Protein Atlas, the expression of E2 receptors is

Gper1>ESR2>>ESR1 (47),

which is in line with Harvey and Harvey (83).

The density of E2 receptors changes in CRC tumour

tissue. In CRC the abundance of E2 receptors shows the pattern

Gper1>>ESR2>ESR1. The order of E2 receptor density in the

healthy colon is similar, but there is an abrupt decrease in ESR2

and an increase in Gper1 expression in the tumour compared to the

healthy gut. Changes in the abundance of E2 receptors in CRC are

more pronounced in males than in females.

As CRC occurs to a lesser extent in females compared

to males (83), and sex-dependent

differences in nuclear E2 receptor expression have been revealed

(72,74–76,84),

female sex hormones were suggested to be involved in the regulation

of CRC progression (85).

Beneficial effects of E2 mediated via ESR2 receptors have been

convincingly demonstrated (76,86);

however, contradictory reports are available concerning the role of

Gper1 in CRC progression (34,53,56,83).

Similarly, little is known about sex-related differences in Gper1

expression, although they have been implied (70,83).

According to our results, there are more pronounced differences in

Gper1 expression in cancer tissue compared to adjacent tissue in

males than in females. This difference is noticeable mainly in

males without nodal metastases.

In our cohort poor survival correlated with high

Gper1 mRNA expression more significantly in males without nodal

involvement than in males in higher stages of disease or females.

These results are in accordance with Gilligan et al

(56), who reported an association

of worse survival in patients with high Gper1 expression.

Information about the correlation in males and females separately

was not provided. Bustos et al (53) reported sex-dependent differences in

relapse-free survival and Gper1 expression; however, as we do not

have data allowing this type of analysis, a comparison was not

possible. Our results are in accordance with the Human Protein

Atlas (47), according to which

there is a stronger association between Gper1 and survival in males

compared to females and worse survival in patients with high Gper1

expression. The association reaches significance only in males in

stage I–II and not in patients with higher stages of disease.

Interestingly, when the survival of males and females together are

correlated with Gper1 expression, the association does not reach

significance, which also implicates a sex-specific dichotomy in

regulation.

There are reports implicating Gper1 as a tumour

suppressor in pancreatic cancer, melanoma and adrenocortical cancer

and as a tumour promoter in glioblastoma and endometrial and

ovarian cancers, whereas in the case of lung, prostate, breast and

colorectal cancers, information about the regulatory impact of

Gper1 is inconclusive (17,18,34,87,88).

Gper1-mediated effects are dependent on the biological context. Our

results imply that intracellular conditions are vital for the

interpretation of Gper1 signalling, even at the level of one type

of solid cancer.

Gper1 is known to induce signalisation mediated via

the EGFR receptor with tyrosine kinase activity (17,89,90). A

deregulated EGFR pathway has been associated with the progression

of many types of cancer, including CRC (91,92).

Therefore, several tyrosine kinase inhibitors and EFGR antibodies

have been developed and introduced into clinical practice (92). Inhibition of EGFR signalling was

shown to benefit patients diagnosed with CRC, and the EFGR

monoclonal antibodies Cetuximab and Panitumumab are now routinely

used to treat this type of cancer (93). In vitro studies elucidated

the molecular mechanisms of cancer inhibition caused by EFGR

repression in several cancer cell lines, including DLD1 (94–97).

Gper1 signalling mediated via the Gs-coupled cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway

has also been shown to promote cell proliferation (98). Therefore, as Gper1 is known to

induce both EGFR- and cAMP-mediated regulation and is reciprocally

involved in VEGFA release, presumably, an oncogenic role of Gper1

might be expected in CRC.

However, signalling mediated by Gper1 is highly

complex. The same group that discovered the connection between

Gper1 and EGFR two years later revealed that Gper1 inhibits EGFR

signalling via the cAMP/PKA pathway by Raf-1 inactivation (89). To further elucidate the ambiguous

effects of Gper1 on CRC progression, we investigated the effect of

Gper1 silencing in CRC cell lines LoVo and DLD1.

According to our results, the distribution of E2

receptors in the CRC cell lines DLD1 and LoVo resembles that

observed in human tissues: the highest mRNA expression is that of

gper1, and the expression of ESR1 is nearly undetectable.

Gper1 silencing in the DLD1 cell line, which expresses mutated

tp53, inhibited the wound closure, implicating the oncogenic

potential of Gper1. By contrast, the decrease in Gper1 availability

caused an increase in the metabolic rate in LoVo cells that

preserved p53 functionality (99).

The p53 protein, encoded by the gene tp53, is

a well-known tumour suppressor that inhibits cell cycle progression

and initiates DNA repair and/or apoptosis and autophagy, in

response to DNA damage, hypoxia, nutrition deficiency, oxidative

stress and some hormones. Cell cycle inhibition is executed by

induction of p21 expression. p21 inhibits the activity of several

types of cyclin/CDK complexes that release repression of

retinoblastoma protein (RB). As cyclin/CDK complexes are

inactivated by p21 and cannot phosphorylate RB, hypophosphorylated

RB inhibits E2F-induced transcription, which is necessary for cell

proliferation (100,101).

The p53 protein is frequently mutated in many types

of cancer, including CRC. According to TCGA, more than 50% of CRC

patients carry a mutated form of tp53. The presence of a

mutated form of p53 is accompanied by worse survival than that of

wild-type tp53. Interestingly, tp53 mutations are

more frequent in males compared to females, which may also

contribute to the higher CRC incidence in males compared to females

(66).

We hypothesize that the signalling pathway

downstream of p53 influences the outcome of Gper1 signalling.

Previously, it was shown that Gper1 expression in the

triple-negative breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468,

which express a mutated form of tp53, had been induced by

γ-radiation, whereas in MCF-7 cells expressing wild-type

tp53, the opposite pattern was observed. Therefore, a tumour

suppressor role dependent on p53 was attributed to Gper1 (102). Our results agree with this

statement as Gper1 was associated with oncostatic functions in LoVo

but not in DLD1 cell lines. Previously, the oncogenic potential of

Gper1 has been described in the CRC cell lines HT-29, DLD1, COLO205

and SW480 (53,55) carrying mutations in the tp53

gene (66,103–106).

Although there are reports implicating a functional

relationship between p53 and oestradiol, the exact mechanism has

either not been completely elucidated or, more likely, comprises

several ways by which E2 and p53 signalling interfere (107). These interferences can differ in a

tissue-dependent manner, e.g. E2 administration decreases p53

expression in lung cancer cells by induction of methyltransferase 1

expression, which increases methylation of the tp53 promoter

(108). On the other hand, a

protective role of E2 in non-malignant colonocytes executed via

p53-mediated regulation has been implicated (109).

The effects of E2 on p53 expression have been

previously investigated mainly with respect to the effects of ERα

on breast cancer progression. ERα interacts with tp53 and

influences its expression. Most of studies report an increase in

tp53 expression in response to ERα binding (107,110–113). On the other hand, there are also

results implicating ERα-induced suppression of p53-regulated gene

expression (114,115). However, in DLD1 cells, ESR1

expression is nearly undetectable; therefore, we do not suppose

that a substantial increase in p53 expression can be induced via

ERα. The results are inconclusive with respect to ERβ signalling

and p53 expression. Although induction of p53 activity in response

to ERβ activation has been reported (107,113), a stimulatory effect of ERβ

interacting with the tp53 promoter on tp53 expression

has not been detected (111).

In silico analysis showed a positive

correlation between Gper1 and tp53 expression in CRC tissues

of males (TCGA) (116). The E2

receptor ligands bisphenol A (117) and G-1 (102,118,119) have also been shown to induce

tp53 expression. Silencing of Gper1 caused a decrease in

tp53 expression in uveal melanoma cell lines (88). The exact mechanism of how Gper1

executes its effect on p53 transcription is unknown. A cAMP

response element (CREB) was identified in the human tp53

gene (120,121) and CREB binding protein plays a key

role in p53 activation (122).

However, whether Gper1 executes its stimulatory effect on

tp53 expression via this region remains to be

elucidated.

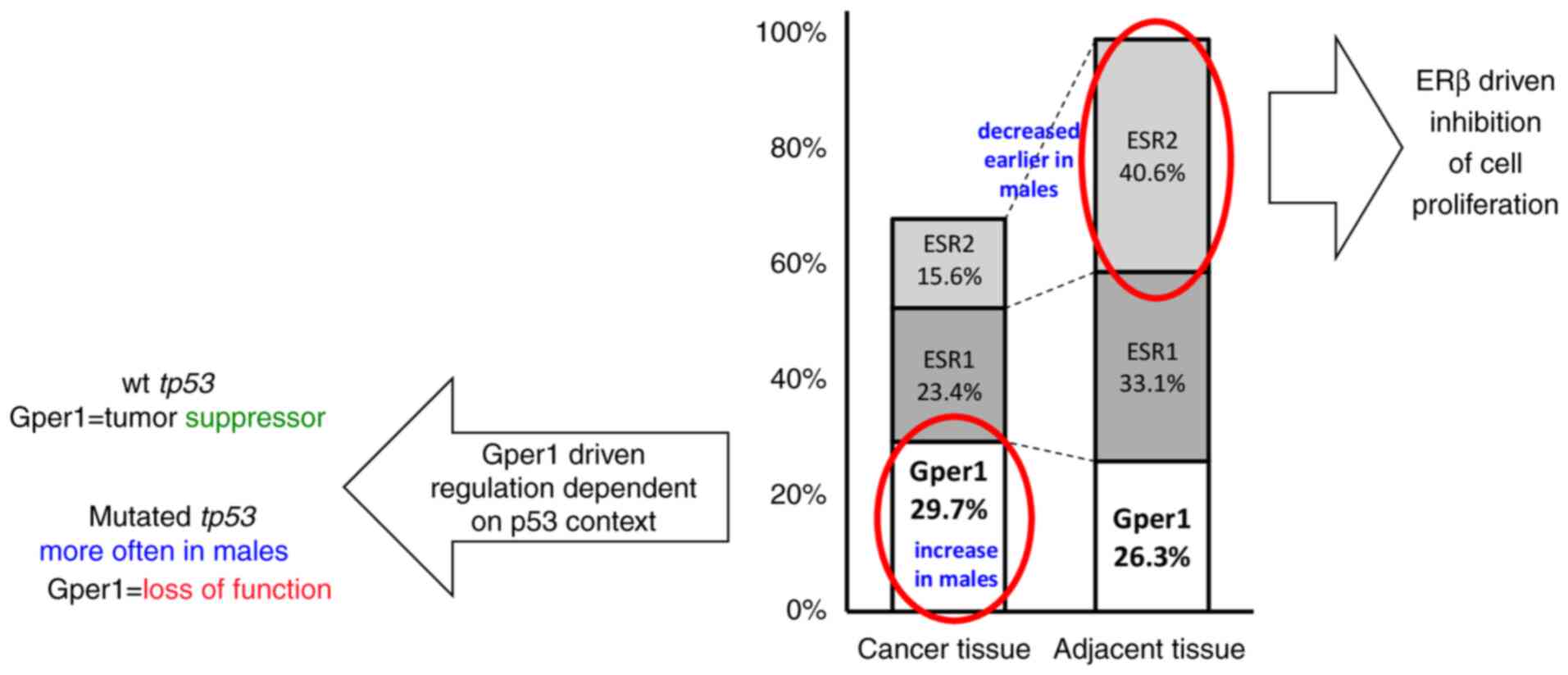

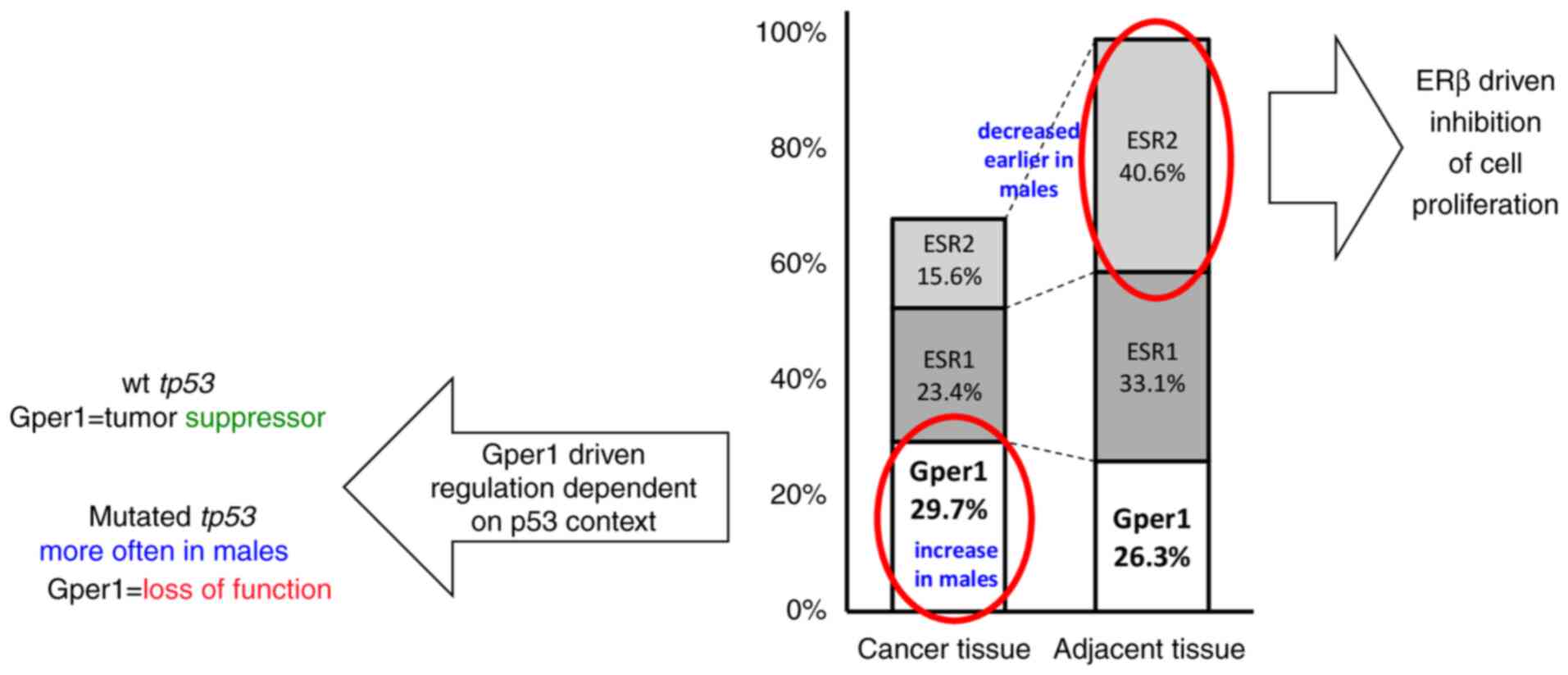

To conclude, the expression of E2 receptors in

healthy tissue follows the descending order

Gper1>ESR2>>ESR1 with nearly undetectable expression of

ESR1 mRNA. In CRC patients the ratio of receptors changes more in

males than in females; the expression of Gper1 mRNA increases while

the expression of ESR2 and ESR1 decreases, resulting in the

descending order Gper1>>ESR2>ESR1. Therefore, under

conditions of cancer progression, most E2 signalling is mediated

via the membrane E2 receptor Gper1. High expression of Gper1 is

associated with worse survival in males without nodal involvement

in comparison with other subcohorts (Fig. 9).

| Figure 9.Possible mechanism of how Gper1

signalling contributes to sex-dependent differences in CRC. In

cancer tissue, the expression of ESR2, which inhibits CRC

progression, decreases in the earlier stages of disease in males

compared to females (74). E2

signalling is further modulated by an increase in Gper1 expression

in cancer tissue in males in the early stages of disease, which is

not observed in females. Therefore, in the CRC tumour

Gper1-mediated regulation strongly influences how E2 signalling

will be interpreted by the cell. Gper1 demonstrates an oncostatic

effect in the LoVo cell line carrying wild-type tp53, which

is not observed in DLD1 cells with mutated tp53. It was

concluded that Gper1 functioning is dependent on the p53

intracellular context. As the mutated form of the gene is more

frequent in males compared to females, and the two most important

gut receptors, Gper1 and ESR2, show a sex-dependent pattern of

expression, we suppose that sex-dependent interpretation of E2

signalling and the availability of a functional p53 pathway

contribute cooperatively to the differences in CRC progression

observed between sexes. ESR, oestrogen receptor; Gper1, G

protein-coupled oestrogen receptor 1; E2, 17β-oestradiol; CRC,

colorectal cancer; wt, wild-type. |

The relative expression of E2 receptors in DLD1 and

LoVo cells is similar to that observed in human CRC tumours. In

LoVo cells with wild-type tp53, a tumour suppressor effect

of Gper1 was observed. This effect was not detected in DLD1 cells

with the mutated form of tp53. We suppose that Gper1

activates the EFGR/RAS oncogenic pathway as well as the p53

pathway. In case the p53 pathway is not functional, the oncogenic

potential of Gper1 overwhelms its tumour suppressor effects. As the

frequency of tp53 mutations as well as changes in Gper1

expression are more robust in males compared to females, we suppose

that these effects can contribute to sex-dependent differences in

CRC incidence.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Soňa Olejarova

(Department of Animal Physiology and Ethology, Faculty of Natural

Sciences, Comenius University in Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovak

Republic) for help with laboratory analyses.

Funding

The research was supported by projects APVV-16-0209 and

APVV-20-0241 provided by The Slovak Research and Development Agency

and project VEGA 1/0455/23 provided by grant agency of the Ministry

of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak

Republic.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets are available from the corresponding

author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

IH and RR designed and administered the human

study. IH and RR confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. RR

obtained samples and organized their transport to the laboratory.

IH performed analysis of human samples. IH and DV performed cell

culture experiments. IH performed in silico analysis,

interpreted results, wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures.

IH, RR and DV reviewed and revised the manuscript for the

scientific content. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The design of the study describing the sampling of

human tissues was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Comenius

University in Bratislava (approval no. ECH 19001). All patients

included in the study agreed to sign an informed consent. The

manuscript does not contain experiments using animals or embryonic

cells.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Professor Iveta Herichová, ORCID:

0000-0002-0475-0461.

References

|

1

|

Cardoso R, Guo F, Heisser T, Hackl M, Ihle

P, De Schutter H, Van Damme N, Valerianova Z, Atanasov T, Májek O,

et al: Colorectal cancer incidence, mortality, and stage

distribution in European countries in the colorectal cancer

screening era: An international population-based study. Lancet

Oncol. 22:1002–1013. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:7–33. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xi Y and Xu P: Global colorectal cancer

burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol.

14:1011742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Murphy N, Ward HA, Jenab M, Rothwell JA,

Boutron-Ruault MC, Carbonnel F, Kvaskoff M, Kaaks R, Kühn T, Boeing

H, et al: Heterogeneity of colorectal cancer risk factors by

anatomical subsite in 10 european countries: Amultinational cohort

study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:1323–1331.e6. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gausman V, Dornblaser D, Anand S, Hayes

RB, O'Connell K, Du M and Liang PS: Risk factors associated with

early-onset colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

18:2752–2759.e2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jacobs ET, Thompson PA and Martínez ME:

Diet, gender, and colorectal neoplasia. J Clin Gastroenterol.

41:731–746. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Quirt JS, Nanji S, Wei X, Flemming JA and

Booth CM: Is there a sex effect in colon cancer? Disease

characteristics, management, and outcomes in routine clinical

practice. Curr Oncol. 24:e15–e23. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lopes-Ramos CM, Quackenbush J and DeMeo

DL: Genome-wide sex and gender differences in cancer. Front Oncol.

10:5977882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Høydahl Ø, Edna TH, Xanthoulis A, Lydersen

S and Endreseth BH: Long-term trends in colorectal cancer:

Incidence, localization, and presentation. BMC Cancer. 20:10772020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Johnson CM, Wei C, Ensor JE, Smolenski DJ,

Amos CI, Levin B and Berry DA: Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer

risk factors. Cancer Causes Control. 24:1207–1222. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Murphy N, Ward HA, Jenab M, Rothwell JA,

Boutron-Ruault MC, Carbonnel F, Kvaskoff M, Kaaks R, Kühn T, Boeing

H, et al: Heterogeneity of colorectal cancer risk factors by

anatomical subsite in 10 European countries: A multinational cohort

study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:1323–1331.e6. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Murphy N, Moreno V, Hughes DJ, Vodicka L,

Vodicka P, Aglago EK, Gunter MJ and Jenab M: Lifestyle and dietary

environmental factors in colorectal cancer susceptibility. Mol

Aspects Med. 69:2–9. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wele P, Wu X and Shi H: Sex-dependent

differences in colorectal cancer: With a focus on obesity. Cells.

11:36882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Barzi A, Lenz AM, Labonte MJ and Lenz HJ:

Molecular pathways: Estrogen pathway in colorectal cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 19:5842–5848. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nie X, Xie R and Tuo B: Effects of

estrogen on the gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 63:583–596.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Labadie JD, Harrison TA, Banbury B, Amtay

EL, Bernd S, Brenner H, Buchanan DD, Campbell PT, Cao Y, Chan AT,

et al: Postmenopausal hormone therapy and colorectal cancer risk by

molecularly defined subtypes and tumor location. JNCI Cancer

Spectr. 4:pkaa0422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Qiu YA, Xiong J and Yu T: Role of G

Protein-coupled estrogen receptor in digestive system carcinomas: A

minireview. Onco Targets Ther. 14:2611–2622. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Prossnitz ER and Barton M: The G

protein-coupled oestrogen receptor GPER in health and disease: An

update. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 19:407–424. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews

J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Ström A, Treuter E, Warner M and

Gustafsson JA: Estrogen receptors: How do they signal and what are

their targets. Physiol Rev. 87:905–931. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fuentes N and Silveyra P: Estrogen

receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol.

116:135–170. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Otto C, Rohde-Schulz B, Schwarz G, Fuchs

I, Klewer M, Brittain D, Langer G, Bader B, Prelle K, Nubbemeyer R

and Fritzemeier KH: G protein-coupled receptor 30 localizes to the

endoplasmic reticulum and is not activated by estradiol.

Endocrinology. 149:4846–4856. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ahmadian Elmi M, Motamed N and Picard D:

Proteomic analyses of the G Protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER1

reveal constitutive links to endoplasmic reticulum, glycosylation,

trafficking, and calcium signaling. Cells. 12:25712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Lange CA and Levin ER:

Membrane-initiated estrogen, androgen, and progesterone receptor

signaling in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 43:720–742. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ding Q, Chorazyczewski J, Gros R, Motulsky

HJ, Limbird LE and Feldman RD: Correlation of functional and

radioligand binding characteristics of GPER ligands confirming

aldosterone as a GPER agonist. Pharmacol Res Perspect.

10:e009952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Leitman DC, Paruthiyil S, Vivar OI,

Saunier EF, Herber CB, Cohen I, Tagliaferri M and Speed TP:

Regulation of specific target genes and biological responses by

estrogen receptor subtype agonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol.

10:629–636. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

De Francesco EM, Lappano R, Santolla MF,

Marsico S, Caruso A and Maggiolini M: HIF-1α/GPER signaling

mediates the expression of VEGF induced by hypoxia in breast cancer

associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Breast Cancer Res. 15:R642013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rennert G, Rennert HS, Pinchev M, Lavie O

and Gruber SB: Use of hormone replacement therapy and the risk of

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:4542–4547. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Johnson JR, Lacey JV Jr, Lazovich D,

Geller MA, Schairer C, Schatzkin A and Flood A: Menopausal hormone

therapy and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev. 18:196–203. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Symer MM, Wong NZ, Abelson JS, Milsom JW

and Yeo HL: Hormone replacement therapy and colorectal cancer

incidence and mortality in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and

ovarian cancer screening trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer.

17:e281–e288. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jang YC, Huang HL and Leung CY:

Association of hormone replacement therapy with mortality in

colorectal cancer survivor: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMC Cancer. 19:11992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hang D, He X, Kværner AS, Chan AT, Wu K,

Ogino S, Hu Z, Shen H, Giovannucci EL and Song M: Plasma sex

hormones and risk of conventional and serrated precursors of

colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. BMC Med. 19:182021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Foster PA: Oestrogen and colorectal

cancer: Mechanisms and controversies. Int J Colorectal Dis.

28:737–749. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mori N, Keski-Rahkonen P, Gicquiau A,

Rinaldi S, Dimou N, Harlid S, Harbs J, Van Guelpen B, Aune D, Cross

AJ, et al: Endogenous circulating sex hormone concentrations and

colon cancer risk in postmenopausal women: A prospective study and

meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 5:pkab0842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Das PK, Saha J, Pillai S, Lam AK, Gopalan

V and Islam F: Implications of estrogen and its receptors in

colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 12:4367–4379. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mal R, Magner A, David J, Datta J,

Vallabhaneni M, Kassem M, Manouchehri J, Willingham N, Stover D,

Vandeusen J, et al: Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ): A ligand

activated tumor suppressor. Front Oncol. 10:5873862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mahbub AA, Aslam A, Elzubier ME, El-Boshy

M, Abdelghany AH, Ahmad J, Idris S, Almaimani R, Alsaegh A,

El-Readi MZ, et al: Enhanced anti-cancer effects of oestrogen and

progesterone co-therapy against colorectal cancer in males. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:9418342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Refaat B, Aslam A, Idris S, Almalki AH,

Alkhaldi MY, Asiri HA, Almaimani RA, Mujalli A, Minshawi F, Alamri

SA, et al: Profiling estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors

in colorectal cancer in relation to gender, menopausal status,

clinical stage, and tumour sidedness. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11872592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Campbell-Thompson M, Lynch IJ and Bhardwaj

B: Expression of estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes and ERbeta

isoforms in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 61:632–640. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Maingi JW, Tang S, Liu S, Ngenya W and Bao

E: Targeting estrogen receptors in colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep.

47:4087–4091. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Herichová I, Jendrisková S, Pidíková P,

Kršková L, Olexová L, Morová M, Stebelová K and Štefánik P: Effect

of 17β-estradiol on the daily pattern of ACE2, ADAM17, TMPRSS2 and

estradiol receptor transcription in the lungs and colon of male

rats. PLoS One. 17:e02706092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Weyant MJ, Carothers AM, Mahmoud NN,

Bradlow HL, Remotti H, Bilinski RT and Bertagnolli MM: Reciprocal

expression of ERalpha and ERbeta is associated with

estrogen-mediated modulation of intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer

Res. 61:2547–2551. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Giroux V, Lemay F, Bernatchez G,

Robitaille Y and Carrier JC: Estrogen receptor beta deficiency

enhances small intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice. Int J

Cancer. 123:303–311. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Weige CC, Allred KF and Allred CD:

Estradiol alters cell growth in nonmalignant colonocytes and

reduces the formation of preneoplastic lesions in the colon. Cancer

Res. 69:9118–9124. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Song CH, Kim N, Lee SM, Nam RH, Choi SI,

Kang SR, Shin E, Lee DH, Lee HN and Surh YJ: Effects of

17β-estradiol on colorectal cancer development after

azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium treatment of ovariectomized

mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 164:139–151. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Son HJ, Sohn SH, Kim N, Lee HN, Lee SM,

Nam RH, Park JH, Song CH, Shin E, Na HY, et al: Effect of estradiol

in an Azoxymethane/Dextran sulfate Sodium-treated mouse model of

colorectal cancer: Implication for sex difference in colorectal

cancer development. Cancer Res Treat. 51:632–648. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hartman J, Edvardsson K, Lindberg K, Zhao

C, Williams C, Ström A and Gustafsson JA: Tumor repressive

functions of estrogen receptor beta in SW480 colon cancer cells.

Cancer Res. 69:6100–6106. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM,

Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C,

Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al: Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the

human proteome. Science. 347:12604192015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Abancens M, Harvey BJ and McBryan J: GPER

agonist G1 prevents Wnt-induced JUN upregulation in HT29 colorectal

cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 23:125812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Muller C, Chaney MF, Cohen JV, Garyantes

T, Lin JJ, LoRusso P, Mita AC, Mita MM, Natale C, Orloff MM, et al:

Phase 1b study of the novel first-in-class G protein-coupled

estrogen receptor (GPER) agonist, LNS8801, in combination with

pembrolizumab in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor

(ICI)-relapsed and refractory solid malignancies and dose

escalation update. J Clinical Oncol. 40 (16_suppl):S2574. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Hall KA and Filardo EJ: The G

Protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER): A critical therapeutic

target for cancer. Cells. 12:24602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liu Q, Chen Z, Jiang G, Zhou Y, Yang X,

Huang H, Liu H, Du J and Wang H: Epigenetic down regulation of G

protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) functions as a tumor

suppressor in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 16:872017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Bühler M, Fahrländer J, Sauter A, Becker

M, Wistorf E, Steinfath M and Stolz A: GPER1 links estrogens to

centrosome amplification and chromosomal instability in human colon

cells. Life Sci Alliance. 6:e2022014992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Bustos V, Nolan ÁM, Nijhuis A, Harvey H,

Parker A, Poulsom R, McBryan J, Thomas W, Silver A and Harvey BJ:

GPER mediates differential effects of estrogen on colon cancer cell

proliferation and migration under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Oncotarget. 8:84258–84275. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Santolla MF, Lappano R, De Marco P, Pupo

M, Vivacqua A, Sisci D, Abonante S, Iacopetta D, Cappello AR, Dolce

V, et al: G protein-coupled estrogen receptor mediates the

up-regulation of fatty acid synthase induced by 17β-estradiol in

cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. J Biol Chem.

287:43234–43245. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Xie M, Liang JL, Huang HD, Wang MJ, Zhang

T and Yang XF: Low doses of nonylphenol promote growth of colon

cancer cells through activation of ERK1/2 via G Protein-coupled

receptor 30. Cancer Res Treat. 51:1620–1631. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Gilligan LC, Rahman HP, Hewitt AM, Sitch

AJ, Gondal A, Arvaniti A, Taylor AE, Read ML, Morton DG and Foster

PA: Estrogen activation by steroid sulfatase increases colorectal

cancer proliferation via GPER. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

102:4435–4447. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Rouhimoghadam M, Lu AS, Salem AK and

Filardo EJ: Therapeutic perspectives on the modulation of G-protein

coupled estrogen receptor, GPER, Function. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 11:5912172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Rodon J, Chaney M, Cohen J, Garyantes TK,

Ishizuka J, Lin JJ, Lorusso P, Mita A, Mita M, Muller C, et al: The

effect of LNS8801 in combination with pembrolizumab in patients

with treatment-refractory cutaneous melanoma. J Immuno Ther Cancer.

11 (Suppl 1):A6272023.

|

|

59

|

Shoushtari AN, Chaney MF, Cohen JV,

Garyantes T, Lin JJ, Ishizuka JJ, Mita AC, Mita MM, Muller C,

Natale C, et al: The effect of LNS8801 alone and in combination

with pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. J

Clin Oncol. 41 (16_Suppl):S9543. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Holm A, Grände PO, Ludueña RF, Olde B,

Prasad V, Leeb-Lundberg LM and Nilsson BO: The G protein-coupled

oestrogen receptor 1 agonist G-1 disrupts endothelial cell

microtubule structure in a receptor-independent manner. Mol Cell

Biochem. 366:239–249. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang C, Lv X, Jiang C and Davis JS: The

putative G-protein coupled estrogen receptor agonist G-1 suppresses

proliferation of ovarian and breast cancer cells in a

GPER-independent manner. Am J Transl Res. 4:390–402.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Gui Y, Shi Z, Wang Z, Li JJ, Xu C, Tian R,

Song X, Walsh MP, Li D, Gao J, et al: The GPER agonist G-1 induces

mitotic arrest and apoptosis in human vascular smooth muscle cells

independent of GPER. J Cell Physiol. 230:885–895. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Mori T, Ito F, Matsushima H, Takaoka O,

Tanaka Y, Koshiba A, Kusuki I and Kitawaki J: G protein-coupled

estrogen receptor 1 agonist G-1 induces cell cycle arrest in the

mitotic phase, leading to apoptosis in endometriosis. Fertil

Steril. 103:1228–1235.e1. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Lv X, He C, Huang C, Hua G, Wang Z,

Remmenga SW, Rodabough KJ, Karpf AR, Dong J, Davis JS, et al: G-1

Inhibits breast cancer cell growth via targeting Colchicine-binding

site of tubulin to interfere with microtubule assembly. Mol Cancer

Ther. 16:1080–1091. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Torres-López L, Olivas-Aguirre M,

Villatoro-Gómez K and Dobrovinskaya O: The G-protein-coupled

estrogen receptor agonist G-1 inhibits proliferation and causes

apoptosis in leukemia cell lines of T lineage. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:8114792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Haupt S, Caramia F, Herschtal A, Soussi T,

Lozano G, Chen H, Liang H, Speed TP and Haupt Y: Identification of

cancer sex-disparity in the functional integrity of p53 and its X

chromosome network. Nat Commun. 10:53852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu Y and Bodmer WF: Analysis of P53

mutations and their expression in 56 colorectal cancer cell lines.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:976–981. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Schneider CA, Rasband WS and Eliceiri KW:

NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods.

9:671–675. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Recchia AG, De Francesco EM, Vivacqua A,

Sisci D, Panno ML, Andò S and Maggiolini M: The G protein-coupled

receptor 30 is up-regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha

(HIF-1alpha) in breast cancer cells and cardiomyocytes. J Biol

Chem. 286:10773–10782. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Jacenik D, Beswick EJ, Krajewska WM and

Prossnitz ER: G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in colon

function, immune regulation and carcinogenesis. World J

Gastroenterol. 25:4092–4104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Foley EF, Jazaeri AA, Shupnik MA, Jazaeri

O and Rice LW: Selective loss of estrogen receptor beta in

malignant human colon. Cancer Res. 60:245–248. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Jassam N, Bell SM, Speirs V and Quirke P:

Loss of expression of oestrogen receptor beta in colon cancer and

its association with Dukes' staging. Oncol Rep. 14:17–21.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Mostafaie N, Kállay E, Sauerzapf E, Bonner

E, Kriwanek S, Cross HS, Huber KR and Krugluger W: Correlated

downregulation of estrogen receptor beta and the circadian clock

gene Per1 in human colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 48:642–647.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Herichova I, Reis R, Hasakova K, Vician M

and Zeman M: Sex-dependent regulation of estrogen receptor beta in

human colorectal cancer tissue and its relationship with clock

genes and VEGF-A expression. Physiol Res. 68 (Suppl 3):S297–S305.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hasakova K, Vician M, Reis R, Zeman M and

Herichova I: Sex-dependent correlation between survival and

expression of genes related to the circadian oscillator in patients

with colorectal cancer. Chronobiol Int. 35:1423–1434. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Williams C, DiLeo A, Niv Y and Gustafsson

JÅ: Estrogen receptor beta as target for colorectal cancer

prevention. Cancer Lett. 372:48–56. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ya G, Wang H, Ma Y, Hu A, Ma Y, Hu J and

Yu Y: Serum miR-129 functions as a biomarker for colorectal cancer

by targeting estrogen receptor (ER) β. Pharmazie. 72:107–112.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Issa JP, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, Hamilton

SR, Davidson NE and Baylin SB: Methylation of the oestrogen

receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat

Genet. 7:536–540. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jiang H, Teng R, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang H,

Wang Z, Cao J and Teng L: Transcriptional analysis of estrogen

receptor alpha variant mRNAs in colorectal cancers and their

matched normal colorectal tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

112:20–24. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Topi G, Ghatak S, Satapathy SR, Ehrnström

R, Lydrup ML and Sjölander A: Combined estrogen alpha and beta

receptor expression has a prognostic significance for colorectal

cancer patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 9:7396202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Kennelly R, Kavanagh DO, Hogan AM and

Winter DC: Oestrogen and the colon: Potential mechanisms for cancer

prevention. Lancet Oncol. 94:385–391. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Barton M, Filardo EJ, Lolait SJ, Thomas P,

Maggiolini M and Prossnitz ER: Twenty years of the G

protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER: Historical and personal

perspectives. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 176:4–15. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Harvey BJ and Harvey HM: Sex differences

in colon cancer: Genomic and nongenomic signalling of oestrogen.

Genes (Basel). 14:22252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Nüssler NC, Reinbacher K, Shanny N,

Schirmeier A, Glanemann M, Neuhaus P, Nussler AK and Kirschner M:

Sex-specific differences in the expression levels of estrogen

receptor subtypes in colorectal cancer. Gend Med. 5:209–217. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Deli T, Orosz M and Jakab A: Hormone

replacement therapy in cancer survivors-review of the literature.

Pathol Oncol Res. 26:63–78. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Topi G, Satapathy SR, Dash P, Fred Mehrabi

S, Ehrnström R, Olsson R, Lydrup ML and Sjölander A:

Tumour-suppressive effect of oestrogen receptor β in colorectal

cancer patients, colon cancer cells, and a zebrafish model. J

Pathol. 251:297–309. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Tirado-Garibay AC, Falcón-Ruiz EA,

Ochoa-Zarzosa A and López-Meza JE: GPER: An estrogen receptor key

in metastasis and tumoral microenvironments. Int J Mol Sc.

24:149932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Ambrosini G, Natale CA, Musi E, Garyantes

T and Schwartz GK: The GPER agonist LNS8801 induces mitotic arrest

and apoptosis in uveal melanoma cells. Cancer Res Commun.

3:540–547. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI and

Frackelton AR Jr: Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2

requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs

via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor

through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol. 14:1649–1660. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Hsu LH, Chu NM, Lin YF and Kao SH:

G-Protein coupled estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:3062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Rubin Grandis J, Melhem MF, Gooding WE,

Day R, Holst VA, Wagener MM, Drenning SD and Tweardy DJ: Levels of

TGF-alpha and EGFR protein in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

and patient survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 90:824–832. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Uribe ML, Marrocco I and Yarden Y: EGFR in

cancer: Signaling mechanisms, drugs, and acquired resistance.

Cancers (Basel). 13:27482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Janani B, Vijayakumar M, Priya K, Kim JH,

Prabakaran DS, Shahid M, Al-Ghamdi S, Alsaidan M, Othman Bahakim N,

Hassan Abdelzaher M and Ramesh T: EGFR-based targeted therapy for

colorectal cancer-promises and challenges. Vaccines (Basel).

10:4992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Giannopoulou E, Antonacopoulou A, Floratou

K, Papavassiliou AG and Kalofonos HP: Dual targeting of EGFR and

HER-2 in colon cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

63:973–981. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Yuan HH, Han Y, Bian WX, Liu L and Bai YX:

The effect of monoclonal antibody cetuximab (C225) in combination

with tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (ZD1839) on colon cancer

cell lines. Pathology. 44:547–551. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Palumbo I, Piattoni S, Valentini V, Marini

V, Contavalli P, Calzuola M, Vecchio FM, Cecchini D, Falzetti F and

Aristei C: Gefitinib enhances the effects of combined radiotherapy

and 5-fluorouracil in a colorectal cancer cell line. Int J

Colorectal Dis. 29:31–41. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Chen X, Liu Y, Yang HW, Zhou S, Cheng C,

Zheng MW, Zhong L, Fu XY, Pan YL, Ma S, et al: SKLB-287, a novel

oral multikinase inhibitor of EGFR and VEGFR2, exhibits potent

antitumor activity in LoVo colorectal tumor model. Neoplasma.

61:514–22. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chuang SC, Chen CH, Chou YS, Ho ML and

Chang JK: G Protein-coupled estrogen receptor mediates cell

proliferation through the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway in murine bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 21:64902020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Berg KCG, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA,

Johannessen B, Bruun J, Danielsen SA, Bjørnslett M, Meza-Zepeda LA,

Eknæs M, Lind GE, et al: Multi-omics of 34 colorectal cancer cell

lines-a resource for biomedical studies. Mol Cancer. 16:1162017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Moulder DE, Hatoum D, Tay E, Lin Y and

McGowan EM: The roles of p53 in mitochondrial dynamics and cancer

metabolism: The pendulum between survival and death in breast

cancer? Cancers (Basel). 10:1892018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Engeland K: Cell cycle regulation:

P53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death Differ. 29:946–960. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Weißenborn C, Ignatov T, Ochel HJ, Costa

SD, Zenclussen AC, Ignatova Z and Ignatov A: GPER functions as a

tumor suppressor in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J Cancer

Res Clin Oncol. 140:713–23. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Rochette PJ, Bastien N, Lavoie J, Guérin

SL and Drouin R: SW480, a p53 double-mutant cell line retains

proficiency for some p53 functions. J Mol Biol. 352:44–57. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Berglind H, Pawitan Y, Kato S, Ishioka C

and Soussi T: Analysis of p53 mutation status in human cancer cell

lines: A paradigm for cell line cross-contamination. Cancer Biol

Ther. 7:699–708. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Hassin O, Nataraj NB, Shreberk-Shaked M,

Aylon Y, Yaeger R, Fontemaggi G, Mukherjee S, Maddalena M, Avioz A,

Iancu O, et al: Different hotspot p53 mutants exert distinct

phenotypes and predict outcome of colorectal cancer patients. Nat

Commun. 13:28002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Leroy B, Girard L, Hollestelle A, Minna

JD, Gazdar AF and Soussi T: Analysis of TP53 mutation status in

human cancer cell lines: A reassessment. Hum Mutat. 35:756–765.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Berger C, Qian Y and Chen X: The

p53-estrogen receptor loop in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 13:1229–1240.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Chen YC, Young MJ, Chang HP, Liu CY, Lee

CC, Tseng YL, Wang YC, Chang WC and Hung JJ: Estradiol-mediated

inhibition of DNMT1 decreases p53 expression to induce

M2-macrophage polarization in lung cancer progression. Oncogenesis.

11:252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Weige CC, Allred KF, Armstrong CM and

Allred CD: P53 mediates estradiol induced activation of apoptosis

and DNA repair in non-malignant colonocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol

Biol. 128:113–120. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Qin C, Nguyen T, Stewart J, Samudio I,

Burghardt R and Safe S: Estrogen up-regulation of p53 gene

expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is mediated by calmodulin

kinase IV-dependent activation of a nuclear factor

kappaB/CCAAT-binding transcription factor-1 complex. Mol

Endocrinol. 16:1793–809. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Berger CE, Qian Y, Liu G, Chen H and Chen

X: p53, a target of estrogen receptor (ER) α, modulates DNA

damage-induced growth suppression in ER-positive breast cancer

cells. J Biol Chem. 287:30117–30127. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Swetzig WM, Wang J and Das GM: Estrogen

receptor alpha (ERα/ESR1) mediates the p53-independent

overexpression of MDM4/MDMX and MDM2 in human breast cancer.

Oncotarget. 7:16049–16069. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Mancini F, Giorgini L, Teveroni E,

Pontecorvi A and Moretti F: Role of sex in the therapeutic

targeting of p53 circuitry. Front Oncol. 11:6989462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Konduri SD, Medisetty R, Liu W,

Kaipparettu BA, Srivastava P, Brauch H, Fritz P, Swetzig WM,

Gardner AE, Khan SA, et al: Mechanisms of estrogen receptor

antagonism toward p53 and its implications in breast cancer

therapeutic response and stem cell regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 107:15081–6. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Lu W and Katzenellenbogen BS: Estrogen

receptor-β modulation of the ERα-p53 loop regulating gene

expression, proliferation, and apoptosis in breast cancer. Horm

Cancer. 8:230–242. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE,

Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et

al: The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring

multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2:401–404.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Bilancio A, Bontempo P, Di Donato M, Conte

M, Giovannelli P, Altucci L, Migliaccio A and Castoria G: Bisphenol

A induces cell cycle arrest in primary and prostate cancer cells

through EGFR/ERK/p53 signaling pathway activation. Oncotarget.

8:115620–115631. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Wei W, Chen ZJ, Zhang KS, Yang XL, Wu YM,

Chen XH, Huang HB, Liu HL, Cai SH, Du J, et al: The activation of G

protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) inhibits proliferation of

estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells in vitro and in

vivo. Cell Death Dis. 5:e14282014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Morelli E, Hunter ZR, Fulciniti M, Gullà

A, Perrotta ID, Zuccalà V, Federico C, Juli G, Manzoni M, Ronchetti

D, et al: Therapeutic activation of G protein-coupled estrogen

receptor 1 in Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. Exp Hematol Onco.

11:542022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Giebler HA, Lemasson I and Nyborg JK: p53

recruitment of CREB binding protein mediated through phosphorylated

CREB: A novel pathway of tumor suppressor regulation. Mol Cell

Biol. 20:4849–4858. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Okoshi R, Ando K, Suenaga Y, Sang M, Kubo

N, Kizaki H, Nakagawara A and Ozaki T: Transcriptional regulation

of tumor suppressor p53 by cAMP-responsive element-binding

protein/AMP-activated protein kinase complex in response to glucose

deprivation. Genes Cells. 14:1429–1440. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Lee CW, Ferreon JC, Ferreon AC, Arai M and

Wright PE: Graded enhancement of p53 binding to CREB-binding

protein (CBP) by multisite phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:19290–19295. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|