Introduction

According to recent Global Cancer Observatory data,

cervical cancer ranked third in terms of prevalence among women,

with an estimated 661,021 newly diagnosed cases and 348,189 deaths

globally in 2022 (1). Cervical

cancer rates remain significantly high in nations lacking

population-based cervical cancer screening initiatives and

contribute substantially to cancer-related deaths and morbidity

(2).

The staging of cervical cancer has traditionally

been performed at the clinical level. However, since the

introduction of the 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics (FIGO) staging criteria, surgical and radiological

evaluations have been incorporated into the process (3–5).

Surgical and radiological data provide key information that can

influence treatment (5). According

to the FIGO criteria, stage IB1 disease involves an invasive

carcinoma that invades the stroma to a depth of >5 mm and is ≤2

cm in its greatest dimension, stage IB2 disease involves an

invasive carcinoma that is >2 cm but ≤4 cm in its greatest

dimension and stage IB3 disease involves an invasive carcinoma that

is >4 cm in its greatest dimension (5). Patients diagnosed with stage IB2

cervical cancer typically undergo radical hysterectomy and pelvic

with or without paraaortic lymphadenectomy as standard treatment.

This surgical procedure involves the excision of a substantial

quantity of vaginal tissue, extending up to the upper half, along

with parametrial tissue (6).

Adjuvant therapy is administered in accordance with

the presence of histopathological risk factors (7). Lymph node involvement, positive

surgical margins and parametrial invasion are considered to be

significant risk factors for tumour recurrence (8). It is generally accepted that adjuvant

therapy should be part of the standard care provided to patients

who have these risk factors (8–10).

Nevertheless, there is ongoing debate regarding the

‘intermediate-risk’ factors. Intermediate-risk factors were

established as tumour dimensions of 2–3.99 cm associated with

lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), deep stromal invasion or

tumour dimensions of ≥4 cm (11).

It is currently unknown whether radical surgery alone or combined

with adjuvant (chemo)radiation is a more effective treatment for

FIGO 2018 stage IB2 cervical cancer (7,9,11,12).

In a previous study, patients with FIGO 2018 stage IB2 who

underwent radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy had an 83.3%

5-year overall survival (OS) rate (13). In addition, in patients with FIGO

2018 stage IB2-IIA2 cervical cancer with intermediate-risk factors,

radical surgery alone achieved similar disease-free survival (DFS)

and OS rates as combining radical surgery with adjuvant

(chemo)radiotherapy (14).

The FIGO 2018 staging system currently lacks

sufficient data to accurately predict the overall oncological

outcomes for patients with stage IB2 cancer, particularly those who

have undergone radical surgery. The aim of the present study was to

examine the effect of intermediate-risk factors on the oncological

prognosis of patients with stage FIGO 2018 IB2 cervical cancer who

did not receive adjuvant therapy.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

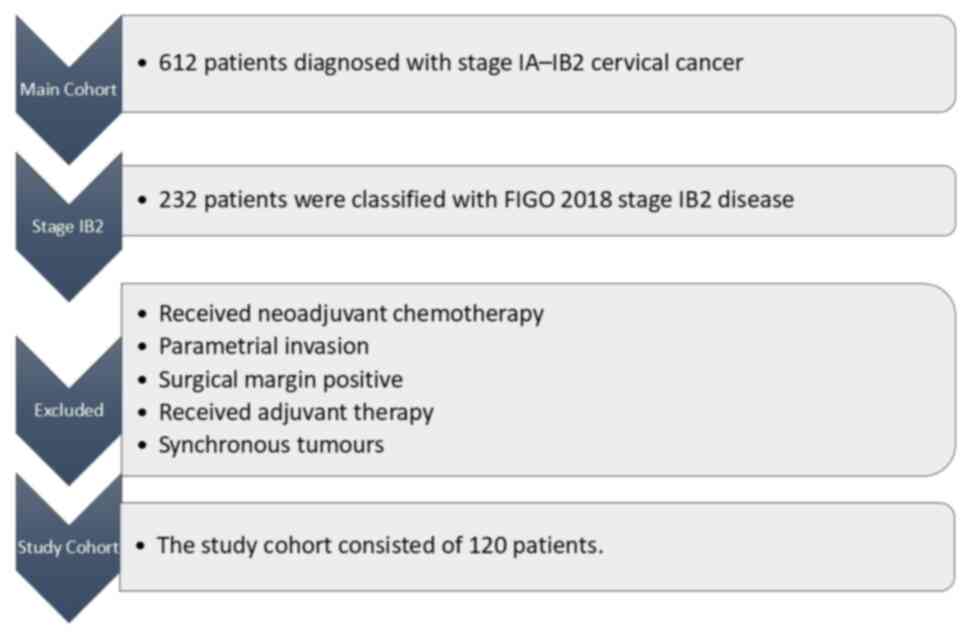

The present multicentric retrospective study

enrolled 612 patients diagnosed with early-stage cervical cancer at

seven tertiary gynaecological oncology centres between 1993 and

2023. The seven gynaecological oncology centres were Ankara Bilkent

City Hospital (Ankara, Turkiye), Ankara Etlik City Hospital

(Ankara, Turkiye), Antalya Training and Research Hospital (Antalya,

Turkiye), Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women's Health Training and Research

Hospital (Ankara, Turkiye), Hacettepe University (Ankara, Turkiye),

Istinye University (Istanbul, Turkiye) and Bahcesehir University

(Istanbul, Turkiye). A total of 232 patients were classified with

FIGO 2018 stage IB2 disease. Patients other than those with FIGO

2018 stage IB2 disease, received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical

margin positive, who had parametrial invasion, received adjuvant

external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy, received adjuvant

chemoradiotherapy, received adjuvant chemotherapy and had

synchronous tumours were excluded from the present study. The

present study cohort consisted of 120 patients who had undergone

radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy (Fig. 1). The clinicopathological data of

the patients were acquired from their patient files or the

hospital's electronic database. Ethical approval in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from the Institutional

Review Board of Ankara Bilkent City Hospital (approval no.

E2-23-4600; Ankara, Turkiye). Approval was obtained from all

institutions participating in the study. All patients provided

informed consent for the institution to utilise their clinical

data. Gynaecological oncologists were the main professionals

responsible for conducting the surgical procedures.

Tumour specimen analysis

The specimens obtained during the surgical

procedures were examined by gynaecological pathologists. The tumour

size was taken as the maximum diameter of the tumour listed in the

final pathology report. The depth of cervical stromal invasion was

not determined. Tumours that infiltrated >50% of the full

thickness of the cervical stroma are referred to here as showing

‘deep cervical stromal invasion’. LVSI was defined by the presence

of tumour cells or clusters attached to the walls of blood or

lymphatic vessels, as observed using haematoxylin and eosin

staining of pathological sections that included both the tumour and

surrounding healthy tissue. The presence of surgical border

involvement as an indicator of tumour positivity was deemed

acceptable when the tumour was detected within a 5 mm margin of the

pathological specimen. The detection of tumours in other areas of

the vaginal region was referred to as microscopic vaginal

involvement. Uterine invasion was characterised by the extension of

the disease into the endometrium and/or myometrium, beyond the

internal cervical ostium. The histopathological evaluations were

performed following the criteria set by the World Health

Organization in 2014 (15).

Statistical analysis

SPSS statistical software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc.)

was used for the statistical analyses. DFS was calculated as the

time between the surgical procedure and the identification of

disease recurrence or the date of the most recent follow-up. OS was

defined as the time between the initial surgical procedure and

subsequent follow-up visits or death due to the disease. The

Kaplan-Meier method was utilised to determine the survival curves,

and the curves were compared utilising the log-rank test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

The present study involved 120 patients with a

median age of 50 years (range, 26–76 years). The median tumour size

was 30 mm (range, 21–40 mm) and the median lymph node removal count

was 45 (range, 14–113). In terms of the tumour types found, 89

(74.2%) patients had squamous cell cancer, 18 (15.0%) had

adenocarcinoma, 2 (1.7%) had a mixed type tumour consisting of

squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma and 11 (9.1%) had other

types of tumours (adenosquamous cancer and glassy cell cancer). All

patients presented with negative surgical border involvement. LVSI

was found in 43 (35.8%) patients, while microscopic vaginal

involvement was present in 5 (4.2%) patients. Deep cervical stromal

invasion was found in 68 (56.7%) patients. Uterine invasion was

present in 7 (5.8%) patients. The present study cohort

characteristics are shown in Table

I.

| Table I.Characteristics of present study group

(n=120). |

Table I.

Characteristics of present study group

(n=120).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|

| Age at initial

diagnosis, years |

|

| Mean ±

SD | 50.9±10.6 |

| Median,

(range) | 50 (26–76) |

| Tumor size, mm |

|

| Mean ±

SD | 31.3±5.5 |

| Median,

(range) | 30 (21–40) |

| No. of removed lymph

nodes |

|

| Mean ±

SD | 47±18.6 |

| Median,

(range) | 45 (14–113) |

| Tumor

typea, n (%) |

|

|

Squamous cell cancer | 89 (74.2) |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 18 (15.0) |

| Mixed

typeb | 2 (1.7) |

|

Othersc | 11 (9.1) |

| Microscopic vaginal

involvement, n (%) |

|

|

Negative | 115 (95.8) |

|

Positive | 5 (4.2) |

| Lymphovascular

space invasion, n (%) |

|

|

Negative | 69 (57.5) |

|

Positive | 43 (35.8) |

| Not

reported | 8 (6.7) |

| Depth of cervical

stromal invasion, n (%) |

|

|

≤50% | 48 (40.0) |

|

>50% | 68 (56.7) |

| Not

reported | 4 (3.3) |

| Uterine invasion, n

(%) |

|

|

Negative | 112 (93.3) |

|

Positive | 7 (5.8) |

| Not

reported | 1 (0.8) |

| Ovarian

transposition, n (%) |

|

| Not

performed | 88 (73.3) |

|

Performedd | 32 (26.7) |

| Ovarian metastasis,

n (%) |

|

|

Negativee | 91 (75.8) |

|

Positive | 0 (0.0) |

The duration of patient follow-up varied from 1 to

246 months and the median was 36 months. Recurrence was observed

between 9–42 months in 6 patients (5%; Table II). In 3 (50%) of the patients with

recurrence, the disease was located at pelvic sites and in the

other 3 (50%) patients, the disease was located at extra-pelvic

with or without pelvic sites. Of the 6 patients with recurrence, 1

patient (0.8%) succumbed to the disease. The 3-year OS rate was 99%

and the 3-year DFS rate was 94%. Overall, 1 patient had microscopic

vaginal involvement. LVSI was observed in 4 patients. All patients

with recurrence had deep cervical stromal invasion.

| Table II.Features of 6 patients with

recurrence. |

Table II.

Features of 6 patients with

recurrence.

| Patient no. | Age, years | Tumor type | Tumor size, mm | Microscopic vaginal

involvement | Cervical stromal

invasion, % | Spread of

endometrium | Over

transposition | Lymphovascular

space invasion | Recurrence time,

months | Recurrence

site | Succumbed to

disease |

|---|

| 1 | 76 | SCC | 22 | + | >50 | - | - | - | 42 | Pelvic | No |

| 2 | 42 | SCC | 30 | - | >50 | - | + | + | 14 |

Extra-pelvica | Yes |

| 3 | 70 | SCC | 35 | - | >50 | - | - | + | 9 |

Extra-pelvicb | No |

| 4 | 41 | SCC | 40 | - | >50 | - | + | + | 12 | Pelvic | No |

| 5 | 41 | SCC | 40 | - | >50 | - | + | - | 28 |

Extra-pelvicc | No |

| 6 | 58 | AC | 40 | - | >50 | + | - | + | 15 | Pelvic | No |

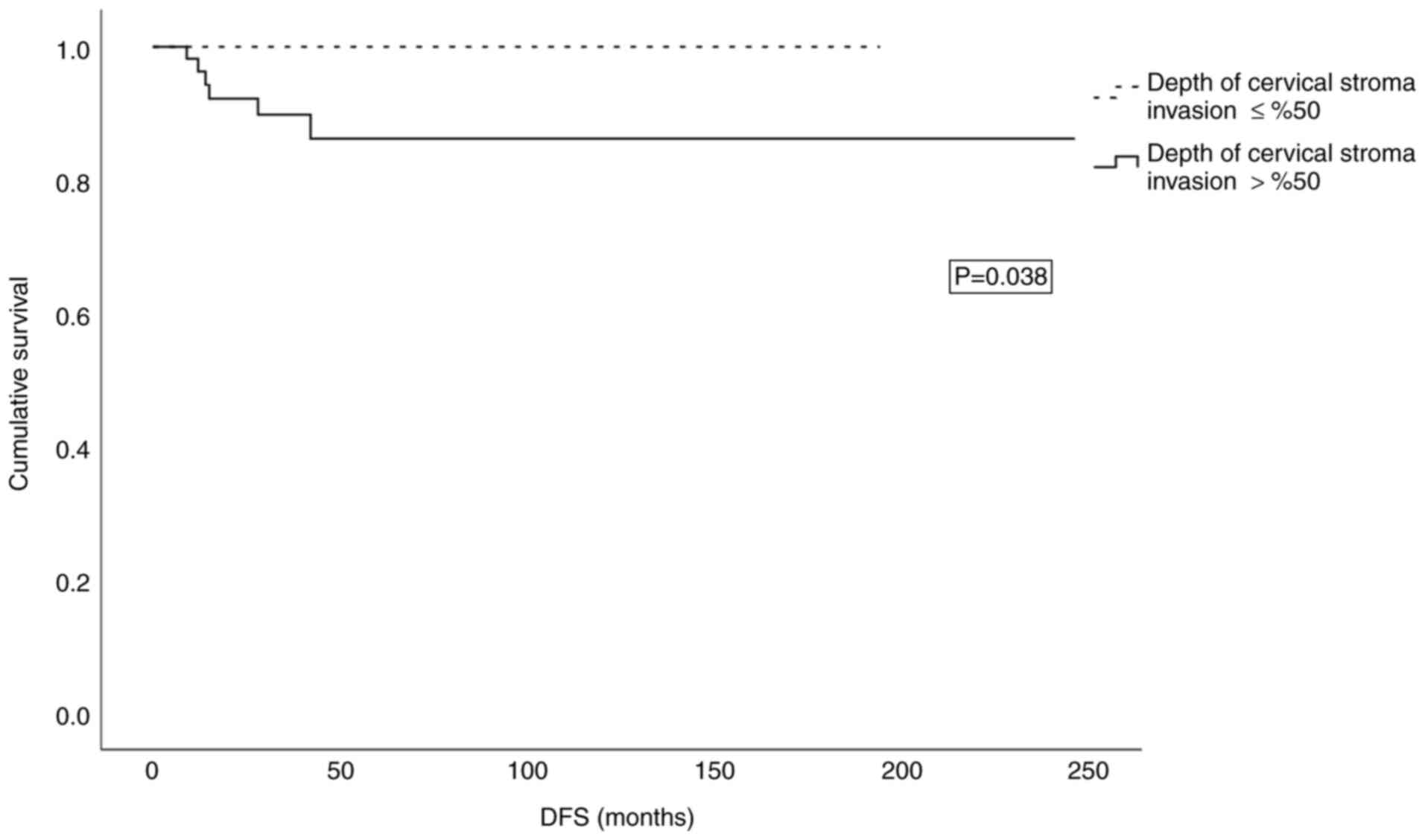

The patient and clinicopathological factors analysed

in relation to 3-year DFS are shown in Table III. Patient age, histopathology,

tumour size, vaginal metastasis, uterine invasion, LVSI, number of

total lymph nodes removed and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were

not statistically significantly associated with 3-year DFS. In the

present study, deep cervical stromal invasion was determined as

>50% of stromal invasion. Deep cervical stromal invasion was

significantly associated with 3-year DFS (P=0.038; Fig. 2).

| Table III.Factors related to 3-year DFS in the

study cohort (n=120). |

Table III.

Factors related to 3-year DFS in the

study cohort (n=120).

| Factors | 3-year DFS, % | P-value |

|---|

| Median age,

years |

| 0.967 |

|

≤50 | 93 |

|

|

>50 | 95 |

|

|

Histopathologya |

| 0.825 |

|

Squamous cell | 94 |

|

|

Non-squamous cell cancer | 94 |

|

| Median tumor size,

mm |

| 0.169 |

|

≤30 | 98 |

|

|

>30 | 88 |

|

| Vaginal

metastasis |

| 0.122 |

|

Negative | 94 |

|

|

Positive | 67 |

|

| Uterine

invasion |

| 0.096 |

|

Negative | 95 |

|

|

Positive | 67 |

|

| Lymphovascular

space invasion |

| 0.141 |

|

Negative | 98 |

|

|

Positive | 88 |

|

| Depth of cervical

stromal invasion, % |

| 0.038 |

|

≤50 | 100 |

|

|

>50 | 90 |

|

| Median no. of total

lymph nodes removed |

| 0.200 |

|

≤45 | 91 |

|

|

>45 | 96 |

|

| Bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy |

| 0.132 |

| Not

performed | 85 |

|

|

Performed | 97 |

|

Discussion

The survival of patients with cervical carcinoma is

influenced by several prognostic factors: Stage, tumour volume,

depth of cervical stromal invasion, LVSI, lymph node involvement,

parametrium involvement and surgical margin involvement (11,16).

The present study involved 120 patients with FIGO 2018 stage IB2

cervical cancer who did not have any high-risk prognostic factors

and did not receive any adjuvant treatment. For the present patient

group, the mean duration of follow-up was 36 months, the 3-year DFS

rate was 94% and the recurrence rate was 5%. Deep cervical stromal

invasion was present in 56.7% of the patients and was found to be

statistically significantly related to DFS in this group.

It is recommended that patients with early-stage

cervical cancer who have had primary surgery and whose risk of

disease recurrence is established by the final pathology report

receive adjuvant treatment (17).

Patients are considered to be at high-risk of recurrence when the

pathological findings show that the parametrium is microscopically

involved, there is involvement of the pelvic lymph nodes and the

surgical margins are positive (17). For patients at intermediate-risk,

the Sedlis criteria are employed to classify the disease (11). A comprehensive retrospective

analysis of 861 patients with intermediate-risk stage IB1-IIA2

disease reported that there were no substantial disparities in DFS

and disease-specific survival between groups that received adjuvant

therapy and a group that did not receive adjuvant therapy (18). In a previous study with 765 patients

with intermediate-risk FIGO 2018 stage IB disease, adjuvant

radiotherapy with or without ± chemotherapy administered after

radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy did not provide a

survival advantage (19).

Kissel et al (20) conducted a study with 145 patients

with FIGO 2018 IB2 cervical cancer who had undergone radical

hysterectomy with lymph node staging and found that the 5-year DFS

rate for these patients was 74.4%. It was also found that the risk

of recurrence increased when the depth of stromal invasion was

>10 mm. In the present study, the 3-year DFS rate was 94% and

the presence of deep cervical stromal invasion was significantly

associated with DFS. Deep cervical stromal invasion was present in

all cases of recurrence. The present study group did not include

high-risk patients; thus, the present study differs from Kissel

et al (20) study in terms

of DFS. Chen et al (21)

included 4,065 patients with 2018 FIGO stages IB1, IB2 and IIA1

cervical cancer in their study. The authors found deep cervical

stromal invasion was an independent prognostic factor for DFS. This

study included patients with stage IB1, IB2 and IIA1 cervical

cancer, but the present study included only patients with stage

IB2. By contrast, DFS was determined by deep cervical stromal

invasion, which was similar to the present research. Zhu et

al (22) included 3,298

patients with cervical cancer undergoing radical hysterectomy. It

found, similar to the present study, that DFS was independently

associated with the deep cervical stromal invasion; the authors

also demonstrated that postoperative radiotherapy is an independent

prognostic factor for DFS (22).

Their findings indicated that extra-pelvic recurrence occurred in

the majority of patients exhibiting full-thickness cervical stromal

invasion following radical surgery. Postoperative radiotherapy in

patients with full-thickness cervical stromal invasion may reduce

recurrence and enhance survival, which suggests that this

population may be suitable for adjuvant radiation therapy (22). The depth of cervical stromal

invasion correlated with survival and was proportional to

postoperative adjuvant therapy (23–25).

Li et al (26) conducted a

study comparing the DFS of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and

adjuvant radiation in patients with deep cervical stromal invasion.

Their findings indicated that patients demonstrated worse responses

to chemotherapy compared with that radiotherapy, and those with

full-thickness invasion had an increased risk of recurrence. Moon

et al (27) found that

postoperative radiotherapy may improve DFS in patients with FIGO

IB-IIA cervical carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion compared

with no adjuvant treatment.

In terms of the location at which cervix cancer

recurs, significant variation has been observed. In a previous

study that only included patients with FIGO 2018 stage IB2 cervical

cancer, recurrence occurred in 14.4% of the patients; 33% of the

recurrences were in the central pelvic area, 33% were nodal and 33%

were distant metastases (20). In

another study conducted with 274 patients with FIGO 2018 stage

IB2-IIA2 cervical cancer, 67.4% of the patients had recurrences in

the pelvic region and 14% of the patients had a recurrence in

another location (14). In the

present study, 5% of the patients experienced recurrence, and half

of those had recurrence at extra-pelvic with or without pelvic

sites.

The main limitation of the present study was its

retrospective design. Cervical cancer has been classified as a

human papillomavirus-based disease since 2020 (28). Since the present study was

retrospective, this new classification was not used and a central

pathological review was not conducted. The factors that determined

the DFS could not be evaluated in a multivariate analysis, as there

were only 6 patients with recurrence. The present study's

advantages are its multicentre design and the sample size of

participants. Gynaecological oncologists performed all the surgical

procedures and specialised gynaecological pathologists evaluated

all the surgical specimens.

In conclusion, patients with FIGO 2018 stage IB2

disease who did not receive adjuvant therapy were found to have a

3-year DFS rate of 94%. Deep cervical stromal invasion was found to

be associated with recurrence. Therefore, the presence of deep

cervical stromal invasion may be a significant indicator of the

need for adjuvant therapy in these patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions but may

be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AAT designed the study, drafted the manuscript and

interpreted the data. OO, OA, AA, AK and VE acquired the data. FK,

BE, FC and HEKY performed formal data analysis. OA and OO confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. CC, DY, CK and IS interpreted

the data. GKC, NB, DB and IU were responsible for the design of the

study. TTo, VK, AK, TTa, OMT, YU, and NO interpreted the data and

reviewed the study critically for important intellectual content.

TTu analyzed and interpreted the data, critically reviewing it for

important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study approved from Ankara Bilkent City

Hospital institutional review board (approval no. E2-23-4600;

Ankara, Turkiye). Approval was obtained from all institutions

participating in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Dr. Abdurrahman Alp Tokalioglu

(ORCID:0000-0002-1776-2744), Dr. Okan Oktar

(ORCID:0000-0002-9696-7886), Dr. Okan Aytekin

(ORCID:0000-0002-6430-4607), Dr. Aysun Alci

(ORCID:0000-0002-7912-7375), Dr. Alper Kahraman

(ORCID:0000-0002-1689-2782), Dr. Volkan Ege

(ORCID:0000-0002-4056-9037), Dr. Fatih Kilic (ORCID:

0000-0002-7333-4883), Dr. Burak Ersak (ORCID: 0000-0003-3301-062X),

Dr. Fatih Celik (ORCID: 0000-0002-9523-180X), Dr. Hande Esra Koca

Yildirim (ORCID: 0000-0002-3715-9424), Dr. Caner Cakir (ORCID:

0000-0003-2559-9104), Dr. Dilek Yuksel (ORCID:

0000-0002-2366-8412), Dr. Cigdem Kilic (ORCID:

0000-0002-4433-8068), Dr. Ilker Selcuk (ORCID:

0000-0003-0499-5722), Dr. Gunsu Kimyon Comert (ORCID:

0000-0003-0178-4196), Professor Nurettin Boran (ORCID:

0000-0002-0367-5551), Dr. Derman Basaran (ORCID:

0000-0002-2689-1417), Professor Isin Ureyen (ORCID:

0000-0002-3491-4682), Professor Tayfun Toptas (ORCID:

0000-0002-6706-6915), Professor Vakkas Korkmaz (ORCID:

0000-0001-8895-6864) Professor Alper Karalok (ORCID:

0000-0002-0059-8773), Professor Tolga Tasci (ORCID:

0000-0001-8645-4385), Professor Ozlem Moraloglu Tekin (ORCID:

0000-0001-8167-3837), Professor Yaprak Ustun (ORCID:

0000-0002-1011-3848), Professor Nejat Ozgul (ORCID:

0000-0002-4257-9431), Professor Taner Turan (ORCID:

0000-0001-8120-1143).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN and

Sankaranarayanan R: Cancer of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynecol

Obstet. 143:22–36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Benedet J, Pecorelli S, Ngan H and Hacker

N: Staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines for

gynaecological cancers. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 70:207–312. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pecorelli S, Zigliani L and Odicino F:

Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol

Obstet. 105:107–108. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Querleu D, Cibula D and Abu-Rustum NR:

2017 update on the Querleu-Morrow classification of radical

hysterectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 24:3406–3412. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cibula D, Pötter R, Planchamp F,

Avall-Lundqvist E, Fischerova D, Haie-Meder C, Köhler C, Landoni F,

Lax S, Lindegaard JC, et al: The European Society of Gynaecological

Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European

Society of Pathology guidelines for the management of patients with

cervical cancer. Virchows Arch. 472:919–936. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Peters III WA, Liu P, Barrett II RJ, Stock

RJ, Monk BJ, Berek JS, Souhami L, Grigsby P, Gordon W Jr and

Alberts DS: Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy

compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy

after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the

cervix. J Clin Oncol. 18:1606–1613. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dostalek L, Åvall-Lundqvist E, Creutzberg

CL, Kurdiani D, Ponce J, Dostalkova I and Cibula D: ESGO survey on

current practice in the management of cervical cancer. Int J

Gynecol Cancer. 28:1226–1231. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Monk BJ, Wang J, Im S, Stock RJ, Peters WA

III, Liu PY, Barrett RJ II, Berek JS, Souhami L, Grigsby PW, et al:

Rethinking the use of radiation and chemotherapy after radical

hysterectomy: A clinical-pathologic analysis of a gynecologic

oncology Group/Southwest oncology Group/Radiation therapy oncology

group trial. Gynecol Oncol. 96:721–728. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS,

Muderspach LI and Zaino RJ: A randomized trial of pelvic radiation

therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage

IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic

lymphadenectomy: A gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol.

73:177–183. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cibula D: Early-stage

intermediate-risk-the group with the most heterogenous management

among patients with cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

32:1227–1228. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wright JD, Matsuo K, Huang Y, Tergas AI,

Hou JY, Khoury-Collado F, St Clair CM, Ananth CV, Neugut AI and

Hershman DL: Prognostic performance of the 2018 International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics cervical cancer staging

guidelines. Obstet Gynecol. 134:49–57. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cibula D, Akilli H, Jarkovsky J, van

Lonkhuijzen L, Scambia G, Meydanli MM, Ortiz DI, Falconer H,

Abu-Rustum NR, Odetto D, et al: Role of adjuvant therapy in

intermediate-risk cervical cancer patients-Subanalyses of the SCCAN

study. Gynecol Oncol. 170:195–202. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML and Herrington CS:

WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. 4th

Edition. IARC Publications; Lyon: 2014

|

|

16

|

Rotman M, Sedlis A, Piedmonte MR, Bundy B,

Lentz SS, Muderspach LI and Zaino RJ: A phase III randomized trial

of postoperative pelvic irradiation in Stage IB cervical carcinoma

with poor prognostic features: Follow-up of a gynecologic oncology

group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 65:169–176. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Peters WA III, Liu P, Barrett II RJ, Stock

RJ, Monk BJ, Berek JS, Souhami L, Grigsby P, Gordon W Jr and

Alberts DS: Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy

compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy

after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the

cervix. J Clin Oncol. 18:1606–1613. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cao L, Wen H, Feng Z, Han X, Zhu J and Wu

X: Role of adjuvant therapy after radical hysterectomy in

intermediate-risk, early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 31:52–58. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nasioudis D, Latif NA, Giuntoli II RL,

Haggerty AF, Cory L, Kim SH, Morgan MA and Ko EM: Role of adjuvant

radiation therapy after radical hysterectomy in patients with stage

IB cervical carcinoma and intermediate risk factors. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 31:829–834. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kissel M, Balaya V, Guani B, Magaud L,

Mathevet P and Lécuru F; SENTICOL group, : Impact of preoperative

brachytherapy followed by radical hysterectomy in stage IB2 (FIGO

2018) cervical cancer: An analysis of SENTICOL I–II trials. Gynecol

Oncol. 170:309–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen X, Duan H, Liu P, Lin L, Ni Y, Li D,

Dai E, Zhan X, Li P, Huo Z, et al: Development and validation of a

prognostic nomogram for 2018 FIGO stages IB1, IB2, and IIA1

cervical cancer: A large multicenter study. Ann Transl Med.

10:1212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhu J, Cao L, Wen H, Bi R, Wu X and Ke G:

The clinical and prognostic implication of deep stromal invasion in

cervical cancer patients undergoing radical hysterectomy. J Cancer.

11:7368–7377. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim SI, Cho JH, Seol A, Kim YI, Lee M, Kim

HS, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH and Song YS: Comparison of survival

outcomes between minimally invasive surgery and conventional open

surgery for radical hysterectomy as primary treatment in patients

with stage IB1-IIA2 cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 153:3–12. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ryu S, Kim M, Nam B, Lee TS, Song ES, Park

CY, Kim JW, Kim YB and Ryu HS: Intermediate-risk grouping of

cervical cancer patients treated with radical hysterectomy: A

Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Br J Cancer. 110:278–285.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Takeshima N, Umayahara K, Fujiwara K,

Hirai Y, Takizawa K and Hasumi K: Treatment results of adjuvant

chemotherapy after radical hysterectomy for intermediate-and

high-risk stage IB-IIA cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 103:618–622.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li L, Song X, Liu R, Li N, Zhang Y, Cheng

Y, Chao H and Wang L: Chemotherapy versus radiotherapy for FIGO

stages IB1 and IIA1 cervical carcinoma patients with postoperative

isolated deep stromal invasion: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer.

16:4032016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Moon SH, Wu HG, Ha SW, Lee HP, Kang SB,

Song YS, Park NH, Kim JW, Park IA and Kim BH: Isolated

full-thickness cervical stromal invasion warrants post-hysterectomy

pelvic radiotherapy in FIGO stages IB-IIA uterine cervical

carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 104:152–157. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Herrington CS: WHO Classification of

Tumours Female Genital Tumours. IARC Publications; Lyon: 2020

|