Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is classified as a

tumor-related disease characterized by clonal expansion of

hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow. The global incidence

is 1–2 cases per 100,000 adults, representing 15% of newly

diagnosed leukemia cases in adults (1). Notably, ~50% of patients with CML lack

typical symptoms in the early stage and are often incidentally

discovered through routine physical examinations or blood tests.

Bone marrow biopsy is the gold standard for confirming hyperplasia

of bone marrow cells and abnormal maturation of the myeloid cell

line. Molecular diagnosis relies on the detection of the BCR-ABL1

fusion gene, which can be identified through the translocation of

chromosomes t(9;22)(q34;q11) using fluorescence in situ

hybridization (FISH) or quantitative PCR (2).

It is noteworthy that 5–10% of cases negative for

the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome require further verification of

BCR-ABL1 mutations through next-generation sequencing (3). Over 95% of CML cases are linked to the

Ph chromosome, whereas ~5% display variant Ph chromosomes

characterized by complex translocations (4). These chromosomal rearrangements lead

to the fusion of the 3′ end of the ABL1 gene on chromosome 9 with

the 5′ end of the BCR gene on chromosome 22, resulting in the

BCR-ABL1 fusion gene (5). For

numerous years, traditional karyotyping has served as the primary

diagnostic approach for identifying t(9;22)(q34; q11.2); however,

this method possesses significant limitations, potentially leading

to the oversight of BCR-ABL1 rearrangements in ~5% of patients with

CML. Over 95% of CML cases exhibit BCR-ABL1 e13a2 or e14a2 fusion

transcripts at the time of diagnosis. Approximately 1% of patients

possess a breakpoint between exons 1 and 2 of the BCR gene,

resulting in the production of the e1a2 transcript (6).

The prognosis of CML has significantly improved with

the application of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), with the

5-year survival rate increasing from 50 to >90% (7). However, ~9% of patients may progress

to blast crisis or accelerated phase, leading to a sharp reduction

in survival. Regular assessment of hematological, cytogenetic and

molecular indicators is necessary to monitor treatment response

(8). Therefore, individualized

treatment and lifelong monitoring are crucial for optimizing the

management of CML.

The current report presents a case of a patient with

CML who tested negative for both reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and

cytogenetic analysis during the initial diagnostic phase.

Subsequent FISH revealed a concealed insertion of the ABL1 gene

into the BCR gene on chromosome 22. The e13a3 BCR-ABL1 fusion

transcript was subsequently validated via DNA sequencing employing

alternative primer sets. The patient received a diagnosis of CML

with the e13a3 atypical fusion gene and underwent treatment with

nilotinib.

Case report

In September 2021, a 39-year-old male patient was

referred to the Department of Hematology, (Shandong Provincial

Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan,

China) after abnormal blood parameters were identified during a

routine health examination. The patient had exhibited splenomegaly

for 3 years. A CT scan of the abdomen conducted upon admission

verified the existence of splenomegaly. Laboratory analyses

indicated a white blood cell count of 95.94×109/l

(reference range,3.5–9.5×109/l), a hemoglobin

concentration of 97 g/l (reference range, 130–175 g/l) and a

platelet count of 929×109/l (reference range,

125–350×109/l). The absolute neutrophil count was

73.49×109/l (reference range, 1.8–6.3×109/l).

Analysis of the peripheral blood smear revealed notable

leukocytosis, comprising ~1% blasts (reference range, 0–1%), 1%

promyelocytes (reference range, 1.0–2.2%), 23% myelocytes and

metamyelocytes (reference range, 4.5–8.5%), and 16% basophils

(reference range, 0–0.5%). Platelets were often observed in a

scattered arrangement. The analysis of the bone marrow smear

indicated active hematopoietic proliferation, exhibiting a

granulocyte-to-erythrocyte ratio of 11.19:1.00. Granulopoiesis was

markedly heightened, characterized by an augmented ratio of

neutrophilic myelocytes and metamyelocytes. Prominent nucleoli were

identified in 74% of cells, a significant number of which displayed

excessive granulation. The levels of eosinophils and basophils were

elevated. The neutrophil alkaline phosphatase (NAP) score was 8

(The NAP activity test employs the Fast Blue B staining method.

Under an oil immersion microscope, 100 mature neutrophils are

observed, and cytoplasmic granules are scored from 0 to 4 based on

staining intensity and density: 0 points, no granules; 1 point,

<25% of cytoplasm lightly stained; 2 points, 25–50% moderately

stained; 3 points, 50–75% deeply stained; 4 points: >75% densely

and deeply stained; the individual scores are summed to yield a

total score ranging from 0 to 400. The normal reference range is

30–130 points), indicating a significant likelihood of CML. Flow

cytometry of the bone marrow demonstrated an increased percentage

of granulocytes at early, intermediate, and late maturation stages.

Myelocytes comprised 83.0% of nucleated cells and exhibited

expression levels of CD33, CD64, CD13 and CD15, alongside partial

expression of CD10, CD11b and CD16, indicative of the chronic phase

of CML.

Molecular analysis (9) for the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene

(p190/p210/p230) yielded negative results, as did tests for JAK2

V617F, CALR exon 9 and MPL exon 10 mutations. Subsequent analysis

of atypical BCR-ABL1 fusion transcripts revealed a positive result

for the e13a3 fusion variant. Chromosomal karyotype analysis

verified the existence of t(9;22)(q34; q11.2). Following these

findings, the patient received a diagnosis of chronic-phase CML

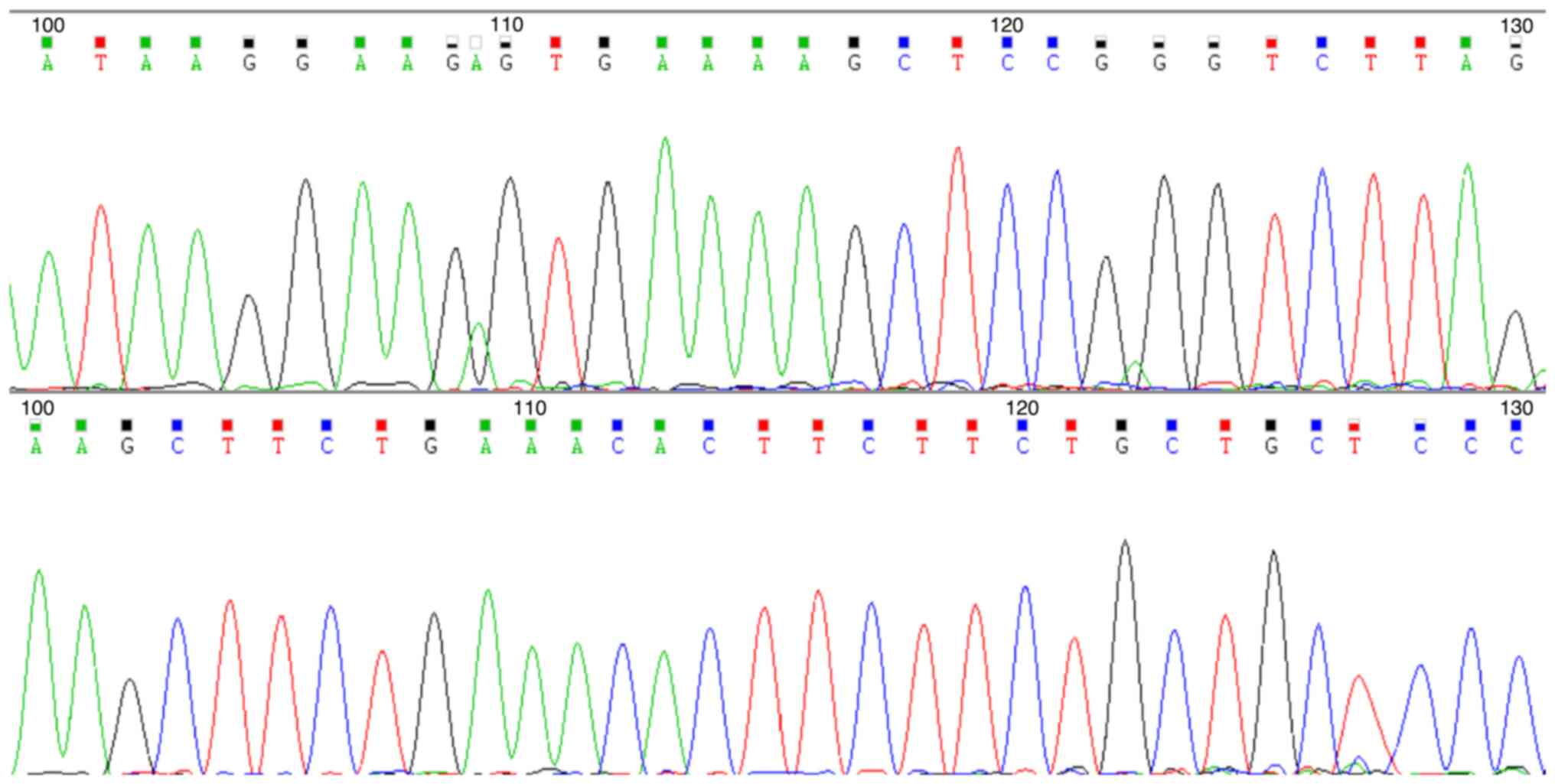

(e13a3 type) (Fig. 1). To elucidate

the characteristics of the fusion gene, RT-PCR was used to amplify

the BCR/ABL e13a3 sequence. The amplified product was subjected to

Sanger sequencing to confirm the precise breakpoint of the e13a3

fusion transcript. RNA was extracted from cells using the Lab-Aid

896 Blood Total RNA Kit (Xiamen Zeesan Biotech Co., Ltd.). RT was

performed using the LF Enzyme 03 Reverse Transcription Kit (Xiamen

Zeesan Biotech Co., Ltd.) under the following thermal conditions:

37°C for 15 min (cDNA synthesis) and 85°C for 5 sec (reverse

transcriptase inactivation). The BCR:ABL1 fusion gene was amplified

using the following five primers: ABL-3 reverse,

CCATTGTGATTATAGCCTAAGACCCGGAG; BCR-1 forward,

CTCCAGCGAGGAGGACTTCTCCT; BCR-6 forward,

CCTGAGAGCCAGAAGCAACAAAGATGCC; BCR-12 forward,

AGAACATCCGGGAGCAGCAGAAGAA; and BCR-19 forward,

ACTGAAGGCAGCCTTCGACGTC.

The reaction was performed with the following

thermal profile: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed

by 39 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 63°C

for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 30 sec, with a final extension

at 72°C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by holding at 4°C.

Amplified products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis.

The reaction system consisted of 1 µl each of forward and reverse

primers, 3 µl of cDNA template, 10 µl of PCR Mix, and ddH2O to make

up the total volume to 20 µl. After purification of the amplified

products, sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye

Terminator v3.1 sequencing kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

and sequence analysis was ultimately completed with the 3130×l

Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Treatment

commenced with nilotinib at a dosage of 300 mg administered twice

daily. After 6 months of consistent therapy, the atypical BCR-ABL1

fusion gene became undetectable, and the patient proceeded with

regular monthly follow-up. At 2 years post-therapy initiation, the

patient exhibited skin induration in the limbs, diagnosed as

cutaneous amyloidosis, attributed to a drug-related adverse effect

of nilotinib. The treatment with the TKI was sustained as the

patient could endure the condition. The patient remains in profound

molecular remission as of the last check-up inn June 2024.

Discussion

The BCR-ABL1 fusion gene serves as a critical

molecular marker in CML, with the e13a2 (b2a2) and e14a2 (b3a2)

transcripts representing >95% of all instances. Nonetheless,

infrequent BCR-ABL1 transcripts, specifically e13a3 (b2a3) and

e14a3 (b3a3), are observed in a minor fraction of patients, with an

occurrence rate of 0.1–0.3% (10,11).

In a substantial cohort study involving 2,331 patients with CML,

only 4 cases (0.1%) exhibited e13a3 or e14a3 transcripts (12). Despite infrequency of occurrence,

recent evidence indicates that the e13a3 transcript may impart

distinct clinical and molecular attributes. The e13a3 transcript is

produced by the direct fusion of exon e13 (b2) of the BCR gene with

exon a3 of the ABL1 gene, resulting in the exclusion of exon a2 of

ABL1 (13). This exon encodes the

SH3 domain, which is essential for the negative regulation of

BCR-ABL1 kinase activity, suggesting that the e13a3 transcript may

modify BCR-ABL1-mediated signaling pathways (14). The absence of the SH3 domain may

impact downstream signaling, including the STAT5 pathway, thereby

affecting the proliferative characteristics of leukemic cells

(15). However, the specific

biological implications of this structural modification require

additional examination.

In terms of clinical manifestations, patients

possessing the e13a3 transcript may display unique characteristics.

An increased basophil count at initial presentation has been

documented in certain cases (16).

Moreover, these patients typically exhibit a positive response to

TKI, frequently attaining molecular responses more swiftly, with

some achieving deep molecular remission (DMR) (17). In a study of 33 patients with CML

with uncommon BCR-ABL1 transcripts, all 4 e13a3 cases attained a

minimum 1-log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts within 3 months,

and 50% achieved undetectable transcript levels within 2 years

(18).

At present, RT-PCR is the established molecular

method for identifying prevalent CML-associated transcripts,

chiefly e13a2 and e14a2. Nonetheless, the lack of the ABL1 a2 exon

in e13a3 may result in conventional RT-PCR assays failing to detect

this variant, thereby producing false-negative outcomes (12). A report indicated that a patient

with CML initially tested negative for BCR-ABL1 via RT-PCR.

However, FISH later identified BCR-ABL1 gene rearrangement, which

was subsequently corroborated by Sanger sequencing that confirmed

the presence of the e13a3 transcript (13). This highlights the inadequacy of

depending exclusively on RT-PCR in these instances. FISH is an

essential adjunctive diagnostic method for identifying BCR-ABL1

rearrangements in cases of negative RT-PCR results (16), whereas Sanger sequencing can

accurately delineate the atypical transcript (17). Therefore, when CML is clinically

suspected but RT-PCR results are negative, the incorporation of

FISH and Sanger sequencing is advised to reduce the risk of

misdiagnosis or overlooked diagnosis. In recent years,

next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as an alternative to

traditional PCR, providing the ability to detect rare transcripts

such as e13a3 and facilitating dynamic monitoring of molecular

responses (18). Therefore, for

patients possessing the e13a3 transcript, refining RT-PCR primer

design to focus on the a3 exon, alongside FISH, Sanger sequencing

and NGS, can significantly improve diagnostic sensitivity and

specificity.

While data on e13a3 patients is scarce, current

studies indicate that this transcript may affect TKI response,

molecular remission rates and treatment-free remission (TFR)

outcomes following TKI cessation (19). The specific BCR-ABL1 transcript

variant influences the rate and magnitude of molecular responses

elicited by TKIs. Patients with the e13a2 transcript demonstrate a

protracted molecular remission and diminished optimal response

rates at 12 months during imatinib therapy in contrast to those

with e14a2 (11). The e13a3

transcript, which omits the ABL1 a2 exon, may similarly undermine

the structural integrity of the BCR-ABL1 protein and its

interaction with TKIs, potentially resulting in a protracted

molecular remission compared to e13a2 or e14a2 instances.

Second-generation TKIs (2G TKIs), such as nilotinib and dasatinib,

typically elicit more profound and rapid molecular responses

compared to imatinib. Patients with the e14a2 transcript attain

molecular remission more swiftly under 2G TKI therapy compared with

those with the e13a2 variant (19).

Despite the limited clinical data on e13a3, its structural

similarity to e13a2 implies that patients with e13a3 may exhibit

inadequate responses to imatinib, rendering 2G TKIs a more suitable

treatment option. The transcript type affects both the initial

response to TKI and the long-term disease-free survival (DFS) and

overall survival (OS). Patients with the e14a2 transcript exhibit

elevated rates of attaining stable DMR and sustaining TFR following

TKI cessation in comparison to those with e13a2 (11). The long-term prognostic implications

of e13a3 remain ambiguous. However, its molecular characteristics

and response patterns indicate that DFS and OS may resemble those

of e13a2 patients, potentially exhibiting slower molecular

remission and reduced TFR maintenance, while not significantly

impacting OS (20).

Adverse events linked to TKI therapy are essential

factors influencing long-term outcomes. Nilotinib is associated

with an increased occurrence of cutaneous adverse reactions,

including keratosis pilaris, which, while generally mild, may

impact treatment adherence (20).

In addition, certain patients may necessitate dose modifications or

therapeutic transitions owing to TKI-associated toxicities, which

could indirectly affect molecular remission and prognosis.

In CML, 1–2% of patients with CML possess atypical

BCR-ABL1 transcripts, such as e13a3, e14a3, e1a2 and e19a2

(21). These uncommon transcripts

influence diagnostic accuracy, treatment response, precision in

minimal residual disease monitoring, and long-term prognosis

(22). Standardized quantitative

PCR assays predominantly focus on e13a2 and e14a2, which diminishes

detection sensitivity for rare transcripts, potentially leading to

an underestimation of relapse risk (23). A current therapeutic objective in

CML management is to enable TFR after the successful cessation of

TKI treatment. The viability of TFR in patients with atypical

transcripts remains predominantly uncertain. Research indicates

that e14a2 patients are more likely to sustain TFR than e13a2

patients; however, information regarding e13a3 cases is limited

(11). Generally, patients with

e14a2 typically show more pronounced DMR, resulting in elevated TFR

success rates, while individuals with e13a2 or atypical transcripts

generally experience suboptimal TFR maintenance (24). Considering the structural attributes

of the e13a3 BCR-ABL1 fusion protein, there may be a diminished

likelihood of maintaining TFR following the cessation of treatment

(19). Patients contemplating TFR

should undergo a meticulous evaluation of molecular response

kinetics. Significantly, 2G TKIs may enhance the durability of

treatment-free remission in comparison to imatinib. Nilotinib is

associated with an increased probability of maintaining

treatment-free remission after cessation, likely attributable to

its capacity to elicit more rapid and significant molecular

responses (19). Patients attaining

Molecular Response (MR)4.5 (25) or

more profound responses through prolonged nilotinib or dasatinib

treatment may demonstrate improved TFR outcomes. Nonetheless,

patients exhibiting atypical transcripts such as e1a2 have shown

elevated rates of treatment discontinuation failure, indicating

that TFR strategies may be inappropriate for this subgroup

(26). In e13a3 patients, the early

achievement of MR4 (BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ≤0.01%) or more profound

responses may improve TFR success. However, additional research is

required to validate this hypothesis. Future research should

concentrate on clarifying remission patterns, determining optimal

TKI regimens, and developing discontinuation strategies for e13a3

patients to refine treatment protocols, enhance quality of life and

improve disease management (24).

The diagnosis and management of the present study's

rare patient with e13a3 BCR-ABL1 CML highlights the complexities

and strategic considerations involved in treating atypical

transcript cases. The patient's diagnosis was initially overlooked

by routine RT-PCR and was subsequently validated through Sanger

sequencing. To enhance molecular diagnostics, RT-PCR protocols must

be refined to identify atypical transcripts such as e13a3 and

integrated with FISH and NGS to improve diagnostic sensitivity and

specificity. The present patient attained complete cytogenetic

remission within 6 months on a 2G TKI (nilotinib), indicating that

e13a3 patients may exhibit favorable early responses to TKIs. The

emergence of drug-related adverse events, such as skin sclerosis,

underscores the necessity for rigorous safety monitoring during TKI

therapy in patients with atypical BCR-ABL1 transcripts.

Consequently, management must prioritize disease remission and

proactive surveillance of treatment-related toxicities,

facilitating personalized therapeutic modifications to enhance

adherence and tolerance.

The transition of treatment objectives for CML from

prolonged medication use to TFR renders the prognosis for achieving

TFR in patients with atypical BCR-ABL1 transcripts markedly

uncertain. This case illustrates that patients with e13a3

transcripts can attain rapid DMR during TKI therapy, indicating the

viability of pursuing TFR with rigorous molecular surveillance.

However, it is essential to underscore that the results of this

single-case study possess inherent limitations regarding

generalization. The emergence of drug-related adverse reactions,

such as skin hardening, in this patient highlights the potential

intricacies of safety profiles during prolonged TKI administration

in atypical transcript carriers.

The present report offers clinical insights into TKI

efficacy in e13a3 CML, yet the molecular mechanisms influencing

signaling dynamics have not been fully elucidated. Structural

analyses reveal that the e13a3 transcript truncates the SH3 domain

of ABL1, which typically suppresses kinase activity via allosteric

interactions with the SH1 domain (27). The lack of SH3 disrupts the SH3-SH2

complex, destabilizing the kinase's inactive conformation. The

absence of SH3 residues critical for its inhibitory role (such as

Tyr-89 and Tyr-134) leads to persistent kinase activation (12). This structural modification also

hinders the binding of allosteric inhibitors such as asciminib to

the myristoyl pocket, thereby facilitating resistance. Conversely,

ATP-competitive TKIs retain efficacy as their interaction with the

active kinase conformation remains unaltered (28). Kinase assays and molecular dynamics

simulations elucidate that SH3 truncation affects the spatial

configuration of the ATP-binding cleft and modifies the allosteric

signaling network (26), accounting

for the varied TKI resistance profiles in BCR-ABL1

leukemogenesis.

The present single-case report lacks the statistical

power to establish definitive clinical correlations, and the

observed outcomes may not represent the wider population of

patients with atypical transcripts. Consequently, clinical

management should implement a dual-faceted strategy: Pursuing

molecular responses via personalized TKI regimens while remaining

alert to the onset of treatment-related toxicities, thereby

facilitating prompt dose adjustments or therapeutic shifts to

enhance adherence and efficacy. In summary, the long-term

management of patients with e13a3 BCR-ABL1 CML requires the

incorporation of accurate molecular diagnostics, customized

therapeutic approaches and vigilant monitoring for adverse events.

Future multicenter collaborative studies and systematic reviews

that consolidate data from analogous rare cases are essential to

substantiate these preliminary findings and to formulate

evidence-based clinical guidelines. Until such data are accessible,

clinicians should regard the current findings as

hypothesis-generating and exercise prudence when extrapolating

these results to other instances involving atypical

transcripts.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work was supported by a grant from the Taishan Youth Scholar

Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. tsqn201812140).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XZ and NS confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. XZ designed the study. ML performed the acquisition, analysis

and interpretation of data. NS performed the analysis and

interpretation of data, and contributed to manuscript drafting and

critical revisions of the intellectual content. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

publication, authorizing the use of their imaging, pathological and

clinical data for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Arzoun H, Srinivasan M, Thangaraj SR,

Thomas SS and Mohammed L: The progression of chronic myeloid

leukemia to myeloid sarcoma: A systematic review. Cureus.

14:e210772022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tsuchiya K, Tabe Y, Ai T, Ohkawa T, Usui

K, Yuri M, Misawa S, Morishita S, Takaku T, Kakimoto A, et al:

Eprobe mediated RT-qPCR for the detection of leukemia-associated

fusion genes. PLoS One. 13:e02024292018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Luatti S, Baldazzi C, Marzocchi G, Ameli

G, Bochicchio MT, Soverini S, Castagnetti F, Tiribelli M, Gugliotta

G, Martinelli G, et al: Cryptic BCR-ABL fusion gene as variant

rearrangement in chronic myeloid leukemia: Molecular cytogenetic

characterization and influence on TKIs therapy. Oncotarget.

8:29906–29913. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Abdulmawjood B, Costa B, Roma-Rodrigues C,

Baptista PV and Fernandes AR: Genetic biomarkers in chronic myeloid

leukemia: What have we learned so far? Int J Mol Sci. 22:125162021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Soverini S, Mancini M, Bavaro L, Cavo M

and Martinelli G: Chronic myeloid leukemia: The paradigm of

targeting oncogenic tyrosine kinase signaling and counteracting

resistance for successful cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 17:492018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Abdullah MA, Amer A, Nawaz Z, Abdullah AS,

Al-Sabbagh A, Kohla S, Nashwan AJ and Yassin MA: An uncommon case

of chronic myeloid leukemia with variant cytogenetic. Acta Biomed.

89:28–32. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Al-Bayati AMS, Al-Bayti AAH and Husain VI:

A short review about chronic myeloid leukemia. J Life Bio Sci Res.

4:15–19. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Iqbal Z, Absar M, Akhtar T, Aleem A,

Jameel A, Basit S, Ullah A, Afzal S, Ramzan K, Rasool M, et al:

Integrated genomic analysis identifies ANKRD36 gene as a novel and

common biomarker of disease progression in chronic myeloid

leukemia. Biology (Basel). 10:11822021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Burmeister T and Reinhardt R: A multiplex

PCR for improved detection of typical and atypical BCR-ABL fusion

transcripts. Leuk Res. 32:579–585. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xue M, Wang Q, Huo L, Wen L, Yang X, Wu Q,

Pan J, Cen J, Ruan C, Wu D and Chen S: Clinical characteristics and

prognostic significance of chronic myeloid leukemia with rare

BCR-ABL1 transcripts. Leuk Lymphoma. 60:3051–3057. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Molica M, Abruzzese E and Breccia M:

Prognostic significance of transcript-Type BCR-ABL1 in chronic

myeloid leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 12:e20200622020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Schäfer V, White HE, Gerrard G, Möbius S,

Saussele S, Franke GN, Mahon FX, Talmaci R, Colomer D, Soverini S,

et al: Assessment of individual molecular response in chronic

myeloid leukemia patients with atypical BCR-ABL1 fusion

transcripts: Recommendations by the EUTOS cooperative network. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 147:3081–3089. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jean J, Sukhanova M, Dittmann D, Gao J and

Jennings LJ: A novel BCR::ABL1 variant detected with multiple

testing modalities. Case Rep Hematol. 2024:84862672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Crampe M, Kearney L, O'Brien D, Bacon CL,

O'Shea D and Langabeer SE: Molecular monitoring in adult

philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with

the variant e13a3 BCR-ABL1 fusion. Case Rep Hematol.

2019:96350702019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hu LH, Pu LF, Yang DD, Zhang C, Wang HP,

Ding YY, Li MM, Zhai ZM and Xiong S: How to detect the rare BCR-ABL

(e14a3) transcript: A case report and literature review. Oncol

Lett. 14:5619–5623. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li Y, Zhang Y, Meng X, Chen S, Wang T,

Zhang L and Ma X: Chronic myeloid leukemia with two rare fusion

gene transcripts of atypical BCR::ABL: A case report and literature

review. Medicine (Baltimore). 103:e367282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pecciarini L, Brunetto E, Grassini G, De

Pascali V, Ogliari FR, Talarico A, Marra G, Magliacane G, Redegalli

M, Arrigoni G, et al: Gene fusion detection in NSCLC routine

clinical practice: Targeted-NGS or FISH? Cells. 12:11352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lee T, Clarke JM, Jain D, Ramalingam S and

Vashistha V: Precision treatment for metastatic non-small cell lung

cancer: A conceptual overview. Cleve Clin J Med. 88:117–127. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Su YJ, Kuo MC, Chen TY, Wang MC, Yang Y,

Ma MC, Lin TL, Lin TH, Chang H, Teng CJ, et al: Comparison of

molecular responses and outcomes between BCR::ABL1 e14a2 and e13a2

transcripts in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Sci. 113:3518–3527.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Leong WMS and Aw CWD: Nilotinib-induced

keratosis pilaris. Case Rep Dermatol. 8:91–96. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cross NCP, Ernst T, Branford S, Cayuela

JM, Deininger M, Fabarius A, Kim DDH, Machova Polakova K, Radich

JP, Hehlmann R, et al: European LeukemiaNet laboratory

recommendations for the diagnosis and management of chronic myeloid

leukemia. Leukemia. 37:2150–2167. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kearney L, Crampe M and Langabeer SE:

Frequency and spectrum of atypical BCR-ABL1 transcripts in chronic

myeloid leukemia. Exp Oncol. 42:78–79. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lee SE, Choi SY, Kim SH, Song HY, Yoo HL,

Lee MY, Kang KH, Hwang HJ, Jang EJ and Kim DW: BCR-ABL1 transcripts

(MR4.5) at post-transplant 3 months as an early

predictor for long-term outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia.

Korean J Intern Med. 32:125–136. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pai HL, Liu CY and Yeh MH:

Scleroderma-like lesions in a patient undergoing combined

pembrolizumab and routine chemotherapy: A case report and

literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 60:10922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang YN, Chu WY, Chen JS, Yeh YH and Cheng

CN: Long-term outcomes of chronic myeloid leukemia in children and

adolescents-real world data from a single-institute in Taiwan. J

Formos Med Assoc. S0929-6646(25)00014-2. 2025.(Epub ahead of

print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lang F, Wunderle L, Pfeifer H, Schnittger

S, Bug G and Ottmann OG: Dasatinib and azacitidine followed by

haploidentical stem cell transplant for chronic myeloid leukemia

with evolving myelodysplasia: A case report and review of treatment

options. Am J Case Rep. 18:1099–1109. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Leske IB and Hantschel O: The e13a3 (b2a3)

and e14a3 (b3a3) BCR::ABL1 isoforms are resistant to asciminib.

Leukemia. 38:2041–2045. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hijiya N and Mauro MJ: Asciminib in the

treatment of philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid

leukemia: Focus on patient selection and outcomes. Cancer Manag

Res. 15:873–891. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|