Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most common

type of ovarian malignancy. It accounts for 85–90% of all malignant

ovarian tumors, with a higher incidence in middle-aged and elderly

women worldwide (1). Based on

histological differentiation, EOCs are classified into serous,

mucinous and endometrioid carcinoma subtypes. The histological

origins of these tumors are diverse, with high-grade serous ovarian

carcinoma (HGSOC) believed to arise from serous tubal

intraepithelial carcinoma before implantation on the ovarian

surface. It represents the most prevalent histological subtype of

EOC, constituting >70% of cases (1). HGSOC that develops on the ovaries or

fallopian tubes lack anatomical barriers, allowing tumor cells to

disseminate freely within the internal organs of the body (2). Once detached from the primary tumor,

these cells may colonize the retroperitoneum or abdominal cavity,

rapidly forming secondary tumor nodules (3,4). The

present report describes a case of HGSOC presenting as a

retroperitoneal tumor. This is a manifestation that, whilst not

uncommon, presents notable diagnostic and therapeutic challenges

due to its nonspecific symptoms and the anatomical complexity of

the retroperitoneal space.

Case report

A 73-year-old woman presented to the Department of

Urology of The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical

University (Nanning, China) in January 2024 with a 2-week history

of right lower abdominal pain. The pain was described as paroxysmal

colic, progressively worsening over time and the patient required

painkillers for sleep. A physical examination revealed no notable

renal tenderness or obvious abdominal mass. The medical history of

the patient included uncontrolled hypertension and the obstetric

history revealed three children, no miscarriages and menopause at

50 years old.

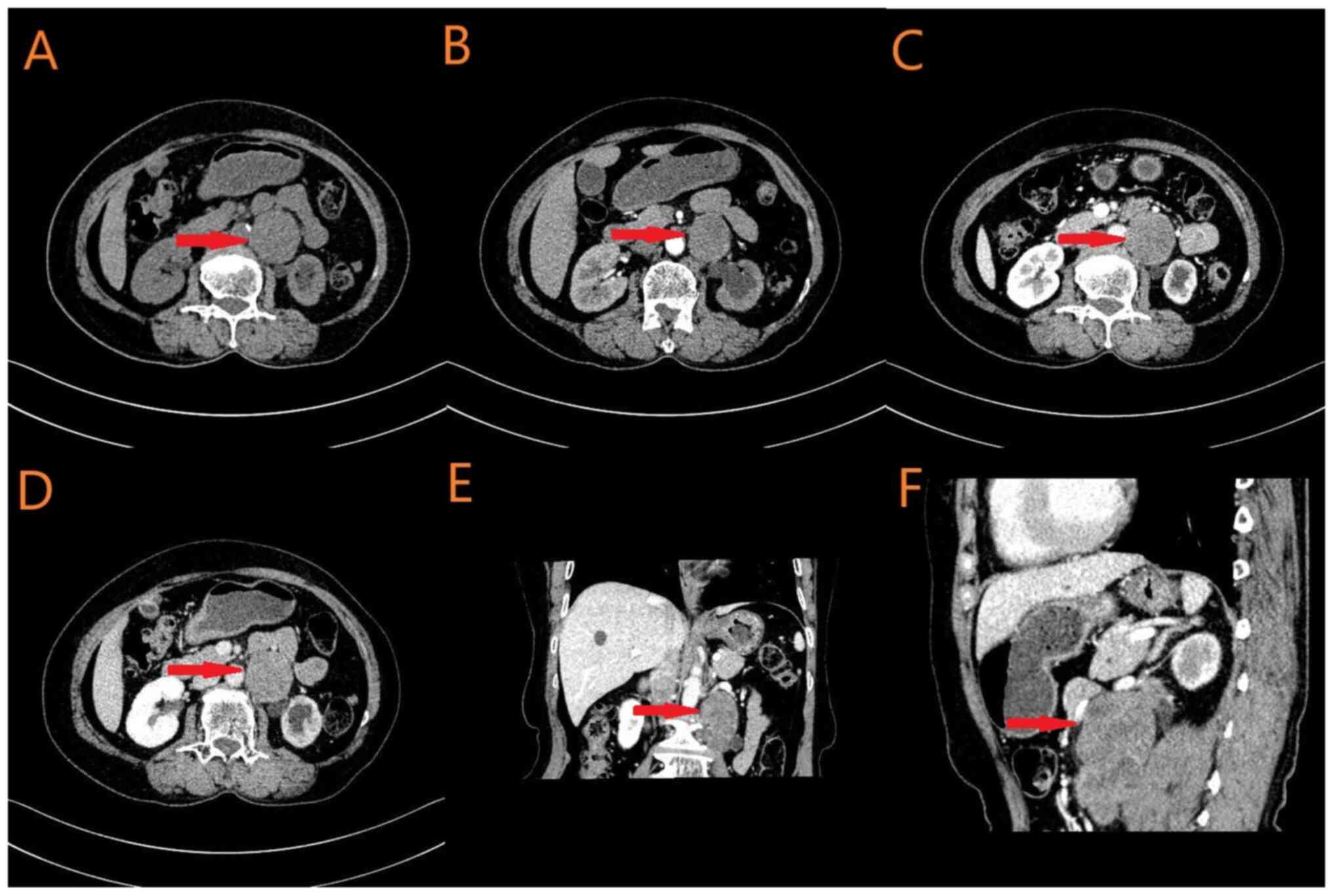

Abdominal CT revealed a 4.2×4.0×8.2 cm mass in the

left posterior abdominal cavity, suspected to be a malignant tumor

involving the left psoas major muscle and left ureter, with

para-aortic lymph node metastasis (Fig.

1). The serum Cancer Antigen 125(CA125 level was mildly

elevated at 39.7 U/ml (normal range, <35 U/ml), while other

tumor markers remained within normal limits, such as cancer antigen

199 (CA199) and CA242. Preoperative renal function tests indicated

renal insufficiency, with a serum creatinine level of 102 µmol/l

(normal range, 50–98 µmol/l). Additionally, adrenal function

abnormalities were noted, with norepinephrine levels elevated at

5,942.7 pmol/l (normal range, 615-3,240 pmol/l). Abdominal

sonography detected a solid mass in the left retroabdominal cavity

(data not shown), whilst renal emission CT (ECT) revealed a notably

reduced left glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 2.38 ml/min

(normal range, 50–60 ml/min).

Following symptomatic management, including blood

pressure control and analgesia, the patient was evaluated for

surgical intervention. The selected surgical plan included a

laparoscopic retroperitoneal mass resection, left ureteral stent

placement, and if necessary, a left nephrectomy.

Intraoperatively, the left upper ureter was revealed

to be notably narrowed, precluding the successful placement of a

5-mm circumference double-J ureteral stent. Consequently, a left

ureteroscopy was performed, and an external ureteral stent (5 mm in

circumference) was inserted as a ureteral marker. Laparoscopic

exploration revealed a retroperitoneal tumor located inferior to

the left kidney, adherent to the lower pole of the kidney and the

left renal vein, with the invasion of the left psoas major muscle

and left upper ureter. Given the proximity of the tumor to the left

kidney and ureter, and the likelihood of direct invasion, an open

surgical approach was recommended. Following an intraoperative

discussion with the family of the patient, an open left

retroperitoneal tumor resection, left nephrectomy and partial left

ureteral resection were performed to achieve radical tumor

removal.

The surgery was successful, and the patient

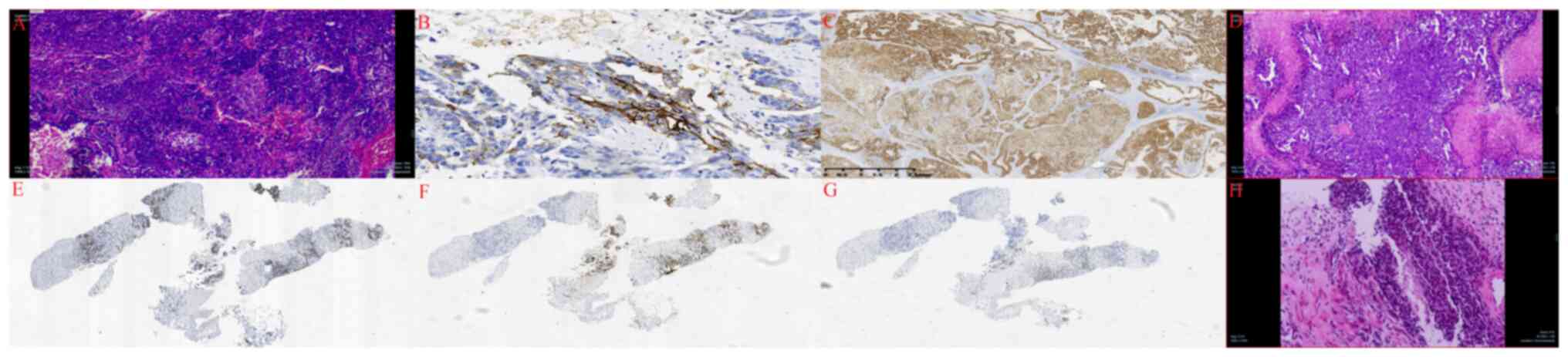

recovered well postoperatively. The pathology report revealed the

following: i) The retroperitoneal mass was identified as a poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma with immunohistochemical markers

suggestive of ovarian origin (Fig.

2A). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated positive CA125

(Fig. 2B) and paired box-8 (PAX-8)

results (Fig. 2C); ii) the tumor

had infiltrated the outer membrane, basal layer and lamina propria

of the ureter; however, the urothelium remained unaffected; iii) no

tumor infiltration was observed in the left renal parenchyma or

perirenal fat (data not shown). For hematoxylin and eosin staining,

tissues were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin at room

temperature for ≥24 h, sectioned at 3–5 µm thickness and stained

with hematoxylin (room temperature for 5–10 min) and eosin (room

temperature for 1–3 min). Slides were observed under a light

microscope. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded tissues

(fixed as aforementioned) were embedded in paraffin and sectioned

at 3–5 µm). Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer

(pH 6.0) at 120°C for 2 min using an autoclave or 95°C for 15 min

using a microwave. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using

3% H2O2. Sections were blocked with 5–10%

Normal Goat Serum (Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 30

min. Primary antibodies were added to the samples and incubated at

4°C overnight or 37°C for 1–2 h. HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies were added to samples and incubated at room temperature

for 30 min, followed by DAB chromogen detection.

Given the suspected ovarian origin, further

gynecological examinations were performed post-surgery.

Gynecological sonography revealed a left adnexal hypoechoic mass,

suspected to be metastatic, along with a right adnexal cyst (data

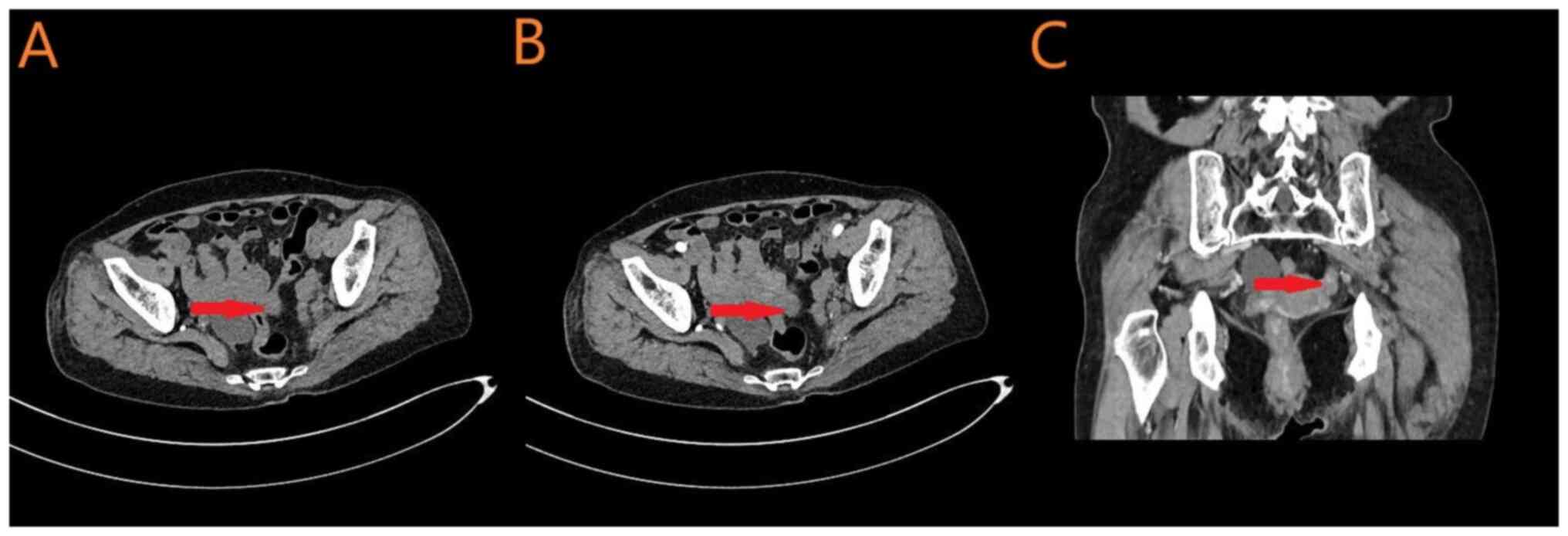

not shown). Furthermore, a pelvic CT (Fig. 3) identified the following: i) A

space-occupying lesion in the left adnexal region and peritoneum,

raising suspicion of malignancy; and ii) A cystic mass in the right

adnexal region, suggesting a benign cystic lesion. Additionally,

PET/CT identified soft tissue metastasis in the left rectouterine

pouch following the retroperitoneal malignant tumor resection (data

not shown). A left adnexal mass of unknown nature prompted a needle

biopsy, which confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with

immunohistochemical features consistent with HGSOC origin (Fig. 2D). The immunohistochemical markers,

CA125 (Fig. 2E), PAX-8 (Fig. 2F) and Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1;

Fig. 2G), were positive.

Based on the aforementioned findings, the patient

was diagnosed with left ovarian HGSOC and poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma in the retroperitoneal space. Following surgical

resection of the retroperitoneal tumor, the patient recovered well

and was transferred to the Department of Gynecology in March 2024

for further management of the left ovarian malignancy. During

hospitalization, the patient underwent a laparoscopic radical

procedure for ovarian cancer, which included a total hysterectomy,

bilateral adnexa, greater omentum, resection of masses in the

Douglas fossa and cecal surface, and pelvic lymph node dissection.

Postoperative histopathology confirmed HGSOC of the left fallopian

tube (Fig. 2H) with tumor invasion

extending through the entire layer of the fallopian tube and into

local mesangial fiber tissue. Metastatic fibrovascular tissue was

identified in the rectouterine pouch mass. However, no metastatic

involvement was detected in the appendages, pelvic lymph nodes,

intestinal wall masses or right-sided omental tissue (data not

shown).

The patient recovered well after surgery and was

treated with postoperative chemotherapy consisting of intravenous

paclitaxel (210 mg/m2) and intravenous carboplatin (360

mg/m2; TC regimen). To date, the patient has completed

six cycles of TC chemotherapy and two cycles of bevacizumab

maintenance therapy. The TC chemotherapy regimen followed a 3-week

cycle. After chemotherapy, bevacizumab maintenance therapy was

administered in 3-week cycles via intravenous injection at a dose

of 15 mg/kg. After completion of the aforementioned treatments, the

following surveillance protocol was recommended: Quarterly

follow-up visits for the first 2 years post-surgery, semiannual

evaluations from the years 3–5 and annual assessments thereafter.

Surveillance components included gynecological examination, blood

tests, pelvic ultrasound and either PET-CT or tumor-specific CT.

Currently, the patient remains in good health and is

self-sufficient without discomfort.

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is a significant public health

concern. According to the World Health Organization, there are

~225,500 new cases and 140,200 deaths annually, making it the

seventh most common cancer globally. HGSOC accounts for ~90% of

these cases (5,6).

HGSOC is associated with a high mortality rate.

According to the American Cancer Society, the overall 5-year

survival rate for HGSOC across all stages is ~44%, which decreases

to ~25% in advanced-stage cases. The majority of patients are

diagnosed only after metastasis, with only ~13% diagnosed at an

early stage (7). This presents a

critical challenge in ensuring timely treatment and improving

survival outcomes.

In most tumors, metastatic dissemination requires

cells to typically undergo a series of cellular transformations by

crossing the basement membrane, migrating and invading the

vasculature, surviving in circulation and extravasating before

forming a mass in a distant organ or tissue. However, HGSOC

primarily originates from the fallopian tube epithelium, which

lacks a physical anatomical barrier to prevent its spread. As a

result, it disseminates mainly through direct peritoneal extension

rather than through the blood or lymph. Consequently, its symptoms

are often non-specific and predominantly gastrointestinal due to

tumor burden in the abdominal cavity or retroperitoneal space.

Patients frequently present with abdominal pain, distension,

nausea, constipation, anorexia, diarrhea and acid reflux,

complicating early diagnosis and delaying treatment (1).

Currently, histopathological examination remains the

gold standard for diagnosing HGSOC, whereas imaging serves

primarily as a screening tool. Key imaging features of HGSOC

include complex pelvic or peritoneal masses rich in blood vessels,

though these findings are nonspecific (6). Identifying the precise origin of the

tumor is often challenging, leading to frequent misdiagnoses and

delayed treatment. In cases involving retroperitoneal tumors,

comprehensive abdominal and pelvic imaging is essential to exclude

tumors originating from other organs, facilitating earlier and more

accurate diagnosis and treatment of HGSOC (8,9).

Clinical evidence from laboratory tests also serves

a critical role in diagnosing HGSOC. CA125, a glycoprotein derived

from embryonic coelomic epithelium, is absent in normal ovary

tissue but frequently expressed in serous tumors. Elevated CA125

levels are observed in ~90% of patients with advanced HGSOC, often

reaching 500–1,000 U/ml (10).

However, in early-stage HGSOC, only ~50% of patients exhibit

elevated CA125 levels, limiting its use as an early diagnostic

marker. Furthermore, CA125 lacks specificity as elevated levels are

also seen in menopausal women, and in conditions such as

endometriosis, pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. These

limitations restrict its effectiveness as a screening tool for

early-stage HGSOC (11). A total of

two large-scale screening studies, the UKCTOCS trial in the UK

(12) and the PLCO trial in the US

(13), investigated the combined

use of CA125 and gynecological ultrasound for early detection.

Although these studies detected more cases of ovarian cancer, most

patients were diagnosed at an advanced stage, and screening did not

markedly improve overall survival (OS). Consequently, the American

Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against

using CA125 for routine early detection, citing the high risk of

false positives, increased patient anxiety and stress, and

unnecessary healthcare costs (13).

Despite its limitations in early diagnosis, CA125 serves as a

valuable biomarker for monitoring treatment response and disease

recurrence in HGSOC. In patients with advanced ovarian cancer, a

decrease in serum CA125 levels following treatment is associated

with a favorable prognosis and treatment efficacy (14). Additionally, recurrent HGSOC is

often asymptomatic, and CA125 monitoring is the primary method for

detecting relapse. A CA125 level that exceeds twice the upper limit

of normal is commonly used as a threshold for diagnosing recurrence

(15). Therefore, whilst CA125 is

not a reliable marker for early detection, it serves a crucial role

in predicting chemotherapy response and assessing the likelihood of

tumor recurrence in HGSOC (16).

In immunohistochemistry (IHC), CA125 exhibits

specific expression patterns that make it useful for the auxiliary

diagnosis, classification and differential diagnosis of HGSOC.

Strong CA125 expression is observed in 80–90% of HGSOC cases, with

diffuse staining of the cell membrane and cytoplasm. In the present

case, the pathological examination of retroperitoneal tumors,

ovarian biopsy tissues and ovarian cancer lesions demonstrated

positive or strongly positive CA125 expression. CA125 can be used

to distinguish primary ovarian cancer from metastatic cancers of

gastrointestinal or breast origin, as these tumors typically lack

CA125 expression in IHC. However, CA125 alone lacks sufficient

specificity for a definitive diagnosis of HGSOC. When necessary, it

should be used in combination with other immune markers, such as

WT1 and PAX-8, along with morphological assessment, to improve the

diagnostic accuracy of HGSOC (17).

Most patients with HGSOC are diagnosed at an

advanced stage, limiting the effectiveness of radical surgery to a

small subset of stage I patients, where the tumor remains confined

to the ovary or fallopian tube. Due to the proximity of tumors to

adjacent organs, even when surgical separation is technically

feasible, concerns about tumor invasion into surrounding tissues

pose significant challenges for surgeons. Therefore, cytoreductive

surgery remains the primary surgical approach for HGSOC and is

crucial for improving patient prognosis (6). Complete tumor resection is associated

with improved long-term outcomes and certain patients may achieve

clinical remission with chemotherapy. Standard cytoreductive

surgery involves the removal of all visible tumors, reproductive

organs and adjacent tissues such as the cecum, sigmoid colon and

greater omentum. Lymph node resection is performed based on nodal

involvement, with the primary aim of achieving optimal

cytoreduction, defined as residual tumor <1 cm in diameter

(5). In the present case,

preoperative renal ECT revealed a left GFR of 2.38 ml/min,

indicating severe functional impairment of the left kidney and

ureter due to tumor infiltration affecting both renal function and

urinary drainage. During the attempt to place a left ureteral

internal stent intraoperatively, complete luminal obstruction was

encountered at an undetermined level of the left ureter, which

precluded passage of a 5-mm circumference stent. Consequently,

ureteral dimensions were not estimated based on the stenotic

segment and smaller-caliber internal stents were not used.

Ultimately, an external ureteral stent (5-mm circumference) was

placed at a non-stenotic portion of the left ureter for anatomical

marking. Notably, external stent placement was not the initial

approach due to its inherent risk of dislodgement. Upon initiating

retroperitoneal tumor resection, surgical findings confirmed the

preoperative assessment: The retroperitoneal tumor demonstrated

complete encasement of the left kidney and proximal ureter,

rendering safe dissection impossible whilst ensuring tumor-free

margins. Therefore, an en bloc resection of the retroperitoneal

mass was performed with the involved left kidney and proximal

ureter. This complete cytoreductive procedure provided optimal

oncological management, markedly improving the prognostic outlook

of the patient.

Following successful cytoreductive surgery, most

patients with HGSOC undergo adjuvant chemotherapy, except for a

small number of stage I patients who may not require further

treatment (5). The standard

chemotherapy regimen, consisting of six consecutive cycles of

paclitaxel plus carboplatin, has remained the standard treatment

for ovarian cancer for the past two decades (18). For patients unable to undergo

surgery or with extensive metastases, neoadjuvant chemotherapy

(NACT) is a viable alternative. This approach typically consists of

three cycles of chemotherapy before surgery, followed by

cytoreductive surgery and an additional three cycles

postoperatively. A total of two randomized trials have reported

that NACT is a non-inferior option to surgery followed by

chemotherapy in terms of both progression-free survival (PFS) and

OS (19,20). Furthermore, advances in

immunotherapy and targeted therapies have expanded treatment

options for HGSOC. WT1 functions as a tumor suppressor protein and

its inactivation has been implicated in the development of

urogenital or renal embryonic tumors (21). SELLAS Life Sciences Group has

performed clinical trials using a WT1-targeted vaccine for the

treatment of ovarian cancer, malignant pleural mesothelioma and

several hematologic and solid tumors (21). The WT1 vaccine is administered in

combination with an adjuvant and an immune modulator,

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, to enhance the

immune response. Early-stage clinical trials in acute myelogenous

leukemia and mesothelioma have reported promising improvements in

both PFS and OS (22). P16, another

tumor suppressor gene, is implicated in HGSOC pathogenesis.

Anti-aging therapy or tumor immunization vaccines targeting P16 may

serve a potential role in treating HGSOC, as aging and the abnormal

retinoblastoma pathway contribute to P16 overexpression (23). Additionally, the formation of

malignant tumors can result from accumulated genetic mutations in

breast cancer (BRCA)1 or BRCA2. Patients with BRCA1- or

BRCA2-positive HGSOC are more responsive to poly-ADP ribose

polymerase inhibitors, which have shown efficacy in inhibiting

tumor recurrence and progression (24).

A total of ~70% of patients with ovarian cancer

initially respond well to platinum-based chemotherapy, with ≥50%

showing no residual cancer on imaging and serum markers at 5 months

post-treatment. However, recurrence rates are >80%, emphasizing

the necessity for long-term follow-up and continuous monitoring

(2). Based on clinical experience

and the 2023 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines

(25), the authors of the present

study recommend the following follow-up protocol: Imaging and

tumor-marker assessments every 3 months for the first 2 years

post-chemotherapy, every 6 months from years 3–5, and then an

annual evaluation thereafter. High-risk patients with HGSOC,

particularly those with retroperitoneal metastasis, should receive

individualized treatment plans and close follow-up, with active

symptom monitoring to promote early detection, diagnosis and timely

treatment.

In conclusion, the present study assessed the

mechanisms through which HGSOC metastasizes to the retroperitoneal

space. It also discussed the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

strategies through a case initially diagnosed as a retroperitoneal

tumor. The findings suggest that retroperitoneal metastasis of

HGSOC may be more common in clinical practice than previously

recognized. However, most patients with HGSOC are diagnosed at an

advanced stage, often presenting with non-specific symptoms.

Therefore, it is recommended that patients presenting with

nonspecific symptoms of retroperitoneal tumor undergo timely

abdominal and pelvic imaging and tumor marker tests to rule out

metastases from other primary sites. Elevated serum CA125 levels

may suggest an ovarian tumor. If other primary lesions are

confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including biopsy should be

implemented to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal treatment

planning, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PH and WP conceived and designed the study. HM

provided administrative support. PH and WP supplied study materials

and patient data. PH and JY collected and assembled the data. PH

and WP confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. HM and JY made

substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work,

and data acquisition and interpretation. JY and WP drafted and

revised the work for important intellectual content. PH and HM

approved the final version to be published and agreed to be

accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring proper resolution

of integrity-related issues. The authors are accountable for all

aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was

approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical

University ethics board (approval no. 2024-E275-01).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient to publish the present report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lisio MA, Fu L, Goyeneche A, Gao ZH and

Telleria C: High-grade serous ovarian cancer: Basic sciences,

clinical and therapeutic standpoints. Int J Mol Sci. 20:9522019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bast RC Jr, Hennessy B and Mills GB: The

biology of ovarian cancer: New opportunities for translation. Nat

Rev Cancer. 9:415–428. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lengyel E: Ovarian cancer development and

metastasis. Am J Pathol. 177:1053–1064. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser

S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D and Bray F: Cancer

incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major

patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 136:E359–E386. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Matulonis UA, Sood AK, Fallowfield L,

Howitt BE, Sehouli J and Karlan BY: Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 2:160612016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS and

Young RH: WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive

Organs. 4th edition. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014

|

|

7

|

Ohman AW, Hasan N and Dinulescu DM:

Advances in tumor screening, imaging, and avatar technologies for

high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Front Oncol. 4:3222014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

National Cancer Institute Surveillance,

Epidemiology and End Results Program, . Cancer Stat Facts: Ovarian

Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.htmlMay

26–2018

|

|

9

|

Gilbert L, Basso O, Sampalis J, Karp I,

Martins C, Feng J, Piedimonte S, Quintal L, Ramanakumar AV,

Takefman J, et al: Assessment of symptomatic women for early

diagnosis of ovarian cancer: Results from the prospective DOvE

pilot project. Lancet Oncol. 13:285–291. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Narod S: Can advanced-stage ovarian cancer

be cured? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 13:255–261. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

The American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, . Five Things Physicians and Patients Should

Question. Choosing Wisely; 2013

|

|

12

|

Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, Ryan

A, Burnell M, Sharma A, Lewis S, Davies S, Philpott S, Lopes A, et

al: Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound

screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected

cancers: Results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative

Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol.

10:327–340. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, Johnson CC,

Lamerato L, Isaacs C, Reding DJ, Greenlee RT, Yokochi LA, Kessel B,

et al: Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: The

prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 305:2295–2302. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

van Altena AM, Kolwijck E, Spanjer MJ,

Hendriks JC, Massuger LF and de Hullu JA: CA125 nadir concentration

is an independent predictor of tumor recurrence in patients with

ovarian cancer: A population-based study. Gynecol Oncol.

119:265–269. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC and

Ledermann JA: Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 384:1376–1388. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Piatek S, Panek G, Lewandowski Z, Piatek

D, Kosinski P and Bidzinski M: Nadir CA-125 has prognostic value

for recurrence, but not for survival in patients with ovarian

cancer. Sci Rep. 11:181902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bates M, Mohamed BM, Lewis F, O'Toole S

and O'Leary JJ: Biomarkers in high grade serous ovarian cancer.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1879:1892242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Markman M: Optimizing primary chemotherapy

in ovarian cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 17:957–968. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, Kristensen

GB, Ehlen T, Johnson N, Verheijen RH, van der Burg ME, Lacave AJ,

Panici PB, et al: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in

stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 363:943–953. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, Jayson GC,

Kitchener H, Lopes T, Luesley D, Perren T, Bannoo S, Mascarenhas M,

et al: Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly

diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): An open-label,

randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 386:249–257.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Denkert C, Loibl S, Müller B, Eidtmann H,

Schmitt W, Eiermann W, Gerber B, Tesch H, Hilfrich J, Huober J, et

al: Ki67 levels as predictive and prognostic parameters in

pretherapeutic breast cancer core biopsies: A translational

investigation in the neoadjuvant GeparTrio trial. Ann Oncol.

24:2786–2793. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Qi X, Zhang F, Wu H, Liu J, Zong B, Xu C

and Jiang J: Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) expression and prognosis in solid

cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep.

5:89242015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Reuschenbach M, Rafiyan M, Karbach J,

Pauligk C, Faulstich F, Sauer M, Prigge ES, Kloor M, Al-Batran S,

Kaufmann AM, et al: Phase I/IIa study of therapeutic p16INK4a

vaccination in patients with HPV-associated cancers. J Clin Oncol.

32:3092–3097. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rice JC, Ozcelik H, Maxeiner P, Andrulis I

and Futscher BW: Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is associated

with decreased BRCA1 mRNA levels in clinical breast cancer

specimens. Carcinogenesis. 21:1761–1765. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, . Ovarian Cancer,

version 1.2023. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2023,

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1453February

15–2025

|