Introduction

Lung cancer is recognized as one of the most

thrombogenic cancer types, wherein venous thromboembolism (VTE)

occurs in up to 14% of patients (1). The risk of VTE is particularly high in

patients with advanced stages of lung cancer, such as those with

adenocarcinoma, which has been associated with a higher incidence

of thrombotic events compared with other histological types of lung

cancer, such as squamous cell carcinoma or small cell lung cancer

(1). The mechanisms underlying the

increased risk of thrombogenesis include immobilization, the

presence of central venous catheters and the direct activation of

the coagulation system by cancer cells, which release procoagulant

factors that stimulate platelet activation and coagulation

pathways. Following vascular endothelial disruption, factor XII

initiates the intrinsic coagulation pathway through contact

activation with subendothelial collagen, thereby mediating

hemostasis in deep tissue injuries. Concurrently, tissue factor

(TF) exposure upon vascular rupture triggers the extrinsic pathway,

enabling rapid thrombin generation via TF-factor VIIa complex

formation. These two pathways synergistically regulate hemostasis

and thrombosis through distinct yet complementary mechanism

(2,3). Chemotherapy, a common treatment for

lung cancer, further exacerbates the risk of thrombosis.

Chemotherapy agents, such as cisplatin, carboplatin, gemcitabine

and paclitaxel, have been demonstrated to elevate procoagulant

activity in endothelial cells and other blood components such as

fibrinogen, antithrombin III and tissue factor pathway inhibitor.

The increase in procoagulant activity is primarily mediated through

mechanisms that involve TF expression and disulfide bond formation,

which contributes to a hypercoagulable state in patients with lung

cancer (4). Furthermore, the

presence of central venous catheters, which are often used for

chemotherapy administration, further increases the risk of

thrombosis. A previous study indicated that patients with lung

cancer who had peripherally inserted central catheters experienced

a high incidence of upper extremity venous thrombosis, particularly

when treated with certain chemotherapeutic agents such as etoposide

(5). The use of antiangiogenic

agents, including bevacizumab, sorafenib, apatinib and

amilorotinib, and immunotherapy has also been linked to an

increased risk of thromboembolic events (2,3). In a

previous study, which included 605 patients diagnosed with

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the presence of EGFR mutations

was associated with varying risks of VTE. Specifically, patients

with EGFR wild-type status had a higher risk of developing VTE

compared with patients with EGFR mutations. The probability of

developing VTE was 8.3% in patients with EGFR mutations after 1

year, compared with 13.2% in patients without EGFR mutations. After

2 years, the probabilities of developing VTE differed significantly

(9.7 and 15.5%, respectively; P=0.047) (6). Furthermore, another study highlighted

that the mutation of EGFR was associated with a decreased risk of

VTE. In a cohort of 310 patients with lung adenocarcinoma, patients

with EGFR mutations had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.46 for VTE, which

suggested a protective effect against thrombosis compared with

patients with wild-type EGFR with lung adenocarcinoma (7). This finding indicated that the

presence of the EGFR-L858R mutation may not only be a driver of

tumorigenesis but could also serve a role in modulating the risk of

thrombotic events. Splenic infarction, a rare but clinically

significant thromboembolic event, arises from the occlusion of the

splenic artery or the splenic artery branches by emboli or thrombi.

With an incidence of 0.016% in hospital admissions, VTE

predominantly results from cardiogenic embolism (62.5%), most

notably atrial fibrillation (1).

Secondary etiologies include autoimmune disorders (12.5%),

infections (12.5%) and hematologic malignancies (6%) (8). Clinically, sudden-onset left upper

quadrant abdominal pain (84% of cases) constitutes the classic

presentation, although asymptomatic cases (≤16%) and atypical

manifestations such as fever and nausea may occur (9). Diagnostic delays are common due to

nonspecific symptoms. The prognosis remains favorable with timely

intervention (10,11). The median hospitalization duration

is 6.5 days, and anticoagulation therapy is initiated in most cases

to mitigate thromboembolic risks and promote recovery (12).

The clinical implications of multiple-site

thrombosis in patients with lung cancer are notable (13,14).

Patients with VTE often experience longer hospital stays, higher

rates of inpatient mortality and increased healthcare costs

compared with patients without VTE. Furthermore, the presence of

thrombosis can complicate cancer treatment, as anticoagulation

therapy may increase the risk of bleeding, particularly in patients

undergoing chemotherapy or surgery (15). The present case illustrated the

complex thrombotic evolution in EGFR-driven NSCLC, which emphasizes

the need for precision anticoagulation strategies.

Case report

Case summary

A 37-year-old man was admitted to the First People's

Hospital of Suining (Suining, China) in December 2024, due to ‘pain

and discomfort in the left upper abdomen for >3 days’.

Furthermore, the patient reported persistent chest tightness

accompanied by myocardial discomfort over a 2-week duration.

Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen, fullness in the left

intercostal space, pronounced tenderness in the left upper quadrant

and palpable enlargement of the spleen, accompanied by significant

rebound tenderness in the spleen area. In November 2024, the

patient developed chest pain, exertional dyspnea and fatigue. An

enhanced CT of the abdomen indicated a filling defect and

low-density shadow in the pancreatic body segment of the splenic

artery, with portions of the splenic parenchyma demonstrating no

enhancement, which raised suspicion for splenic artery embolism and

splenic infarction. Upon admission, empiric antimicrobial

prophylaxis with intravenous cefuroxime (4.5 g/day; treatment

duration, 1 week) was initiated to mitigate infectious

complications of splenic infarction. Simultaneous therapeutic

anticoagulation with subcutaneous enoxaparin sodium (8,000 IU every

12 h; treatment duration, 3 weeks) targeted thromboembolic

pathophysiology. The patient was discharged from hospital in

December 2024 and followed up until May 2025, and the splenic

infarction in the patient had not progressed and had gradually

healed spontaneously.

Past medical history

The patient was admitted to the First People's

Hospital of Suining in October 2024 due to pleural effusion. Lung

adenocarcinoma cells were identified in the exfoliated cells from

the pleural effusion, which led to a diagnosis of a malignant tumor

in the upper lobe of the left lung, classified as adenocarcinoma

T3N2M1a at IVA stage (16)

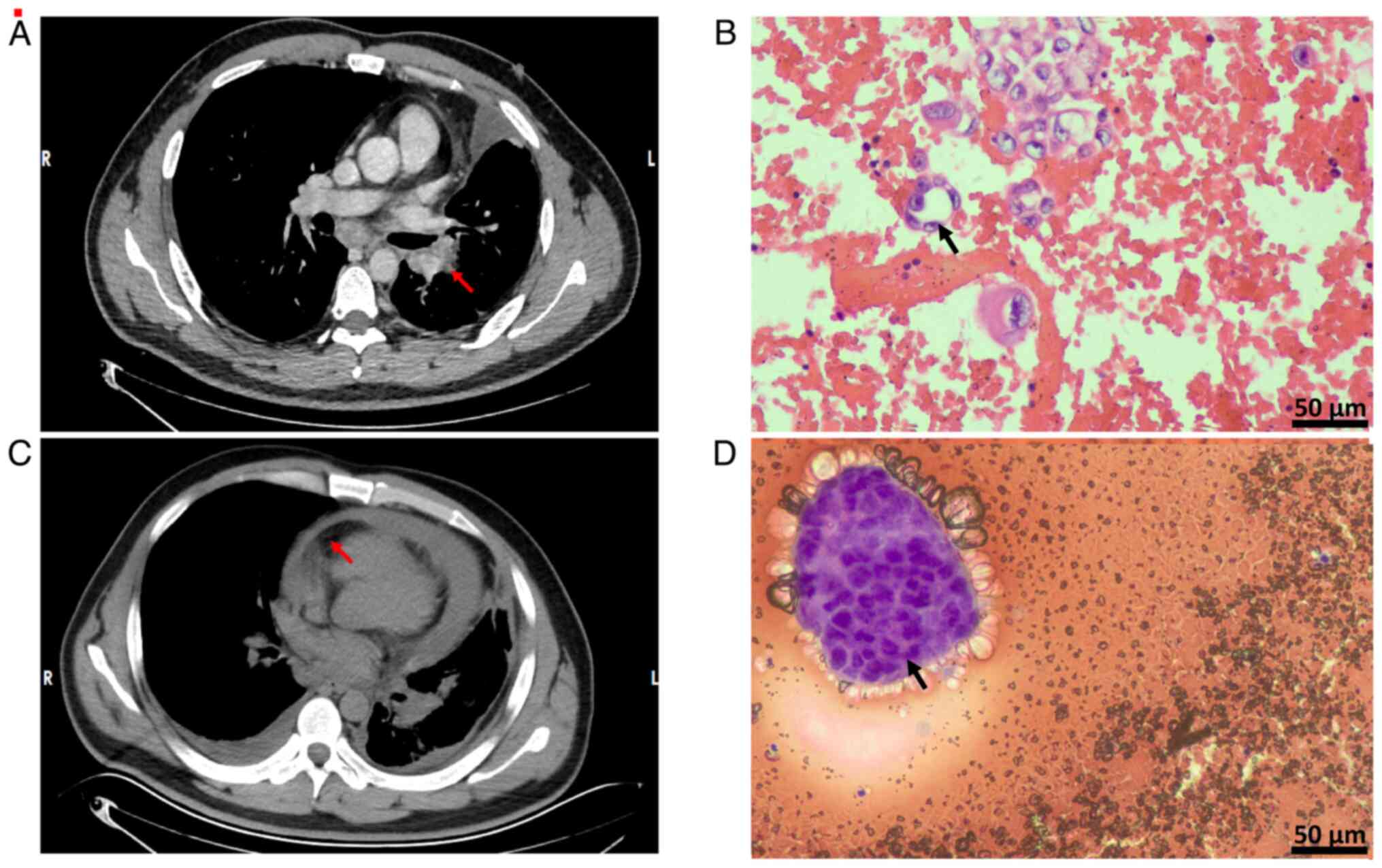

(Fig. 1A and B). On admission,

according to the Khorana scoring scale (17), the VTE score of the patient was

classified as low-risk. Additionally, malignant pericardial

effusion (MPE) was diagnosed at the First People's Hospital of

Suining in October 2024 (Fig. 1C and

D), which prompted the performance of pericardiocentesis and

catheter drainage. A week before presentation in December 2024,

color ultrasound examinations of the lower extremity veins and the

internal jugular vein demonstrated thrombosis in the popliteal

vein, posterior tibial vein, peroneal vein and right internal

jugular vein. Following discharge, the patient was prescribed

rivaroxaban at a dose of 10 mg twice daily for anticoagulation for

3 months, with dose and frequency adjusted based on lower extremity

venous ultrasound review.

Genetic findings

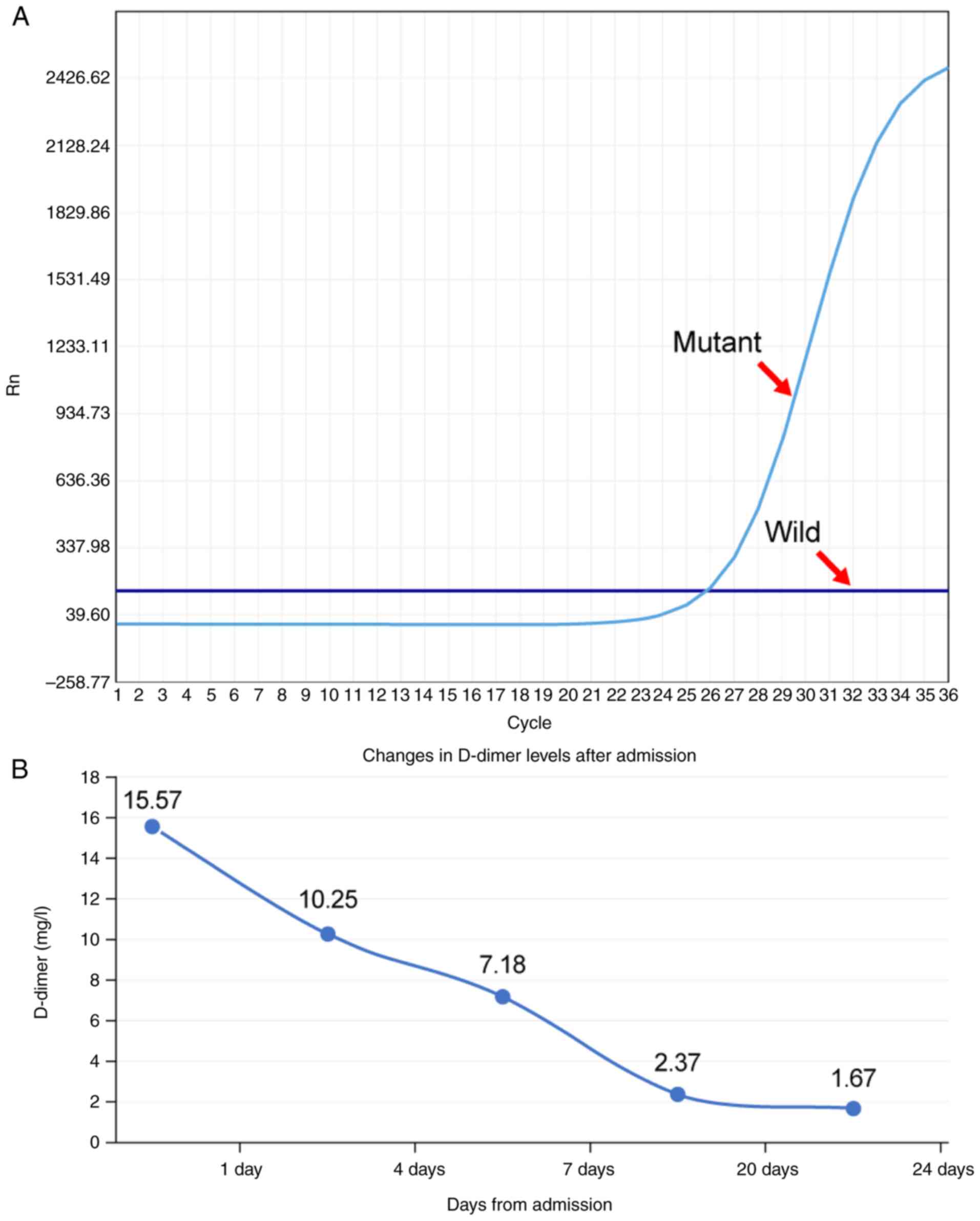

The amplification refractory mutation

system-polymerase chain reaction analysis (experiments were carried

out by the Pathology Laboratory of Suining Central Hospital,

Suining, China; data were obtained from medical records) confirmed

a heterozygous activating mutation at exon 21 of the EGFR gene

(c.2573T>G, p.Leu858Arg), which corresponded to the canonical

L858R substitution (Fig. 2A). The

target EGFR gene primer sequences were as follows: Forward,

5′-GCCAGGAACGTACTGGTGAA-3′and reverse,

5′-CCTTCTGCATGGTATTCTTTCTCTTC-3′.

Laboratory test results

Laboratory test results of routine blood tests on

admission are shown in Table I.

| Table I.Laboratory test findings on admission

of the patient. |

Table I.

Laboratory test findings on admission

of the patient.

| Blood

parameters | Value | Normal range |

|---|

| WBC,

×109/l | 4.79 | 4.0–10.0 |

| Neutrophil, % | 63.8 | 50-70 |

| Lymphocyte, % | 19.7 | 20-40 |

| Monocyte, % | 12.9 | 3-8 |

| Eosinophil, % | 3.5 | 1-4 |

| Basophil, % | 0.1 | 0.5–1 |

| RBC,

×1012/l | 4.36 | 3.5–5.5 |

| HGB, g/l | 134 | 120-160 |

| PLT,

×109/l | 168 | 100-300 |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.85 | 0.56–1.7 |

| TC, mmol/l | 5.24 | <5.2 |

| Na, mmol/l | 138.2 | 135-145 |

| K, mmol/l | 4.36 | 3.5–5.0 |

| CL, mmol/l | 103.4 | 96-108 |

| TP, g/l | 73.6 | 60-80 |

| ALB, g/l | 42.1 | 35-55 |

| AKP, U/l | 134 | 45-125 |

| AST, U/l | 24 | 10-40 |

| ALT, U/l | 37 | 10-40 |

| CK-MB, ng/ml | 2.2 | <5 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 82 | <100 |

| TNT-HS, ng/ml | 0.007 | <0.1 |

| D-dimer, mg/l | 15.57 | <0.5 |

| Fibrinogen,

g/l | 6.01 | 2-4 |

| PT, sec | 17.9 | 11-14 |

| APTT, sec | 47.4 | 25-37 |

| FDP, µg/ml | 74.73 | <5 |

| R, min | 3.5 | 5-10 |

| K, min | 2.2 | 1-3 |

| MA, mm | 44.5 | 50-70 |

| CI | −0.7 | −3-+3 |

| EPL, % | 0 | <15 |

| Solidification

angle, ° | 63.6 | 53-72 |

| pCO2,

mmHg | 34 | 35-45 |

| pO2,

mmHg | 99 | 80-100 |

| PROGRP, pg/ml | 29.7 | <63 |

| NSE, ng/ml | 15.9 | <16.3 |

| CYFRA21-1,

ng/ml | 12.1 | <3.3 |

| mSCC, ng/ml | 1.14 | <5 |

| CEA, ng/ml | 1.23 | <1.5 |

| PT-INR | 1.1 | 0.8–1.2 |

| PA, g/l | 3.2 | 1.5–2.5 |

Changes in D-dimer levels

Numerous studies have established that D-dimer

levels serve as an independent risk predictor for VTE in various

cancer types such as kidney, breast, rectal and ovarian cancer

(18–20). In the present study, the D-dimer

levels of the patient were dynamically monitored by detecting the

D-dimer levels in the serum. When the patient presented with

multiple thrombosis sites, the D-dimer levels (15.57 mg/l) were

increased compared with the normal range (<0.5 mg/l) (Fig. 2B). Following anticoagulation

treatment, the D-dimer levels gradually returned to normal levels

(<0.5 mg/l).

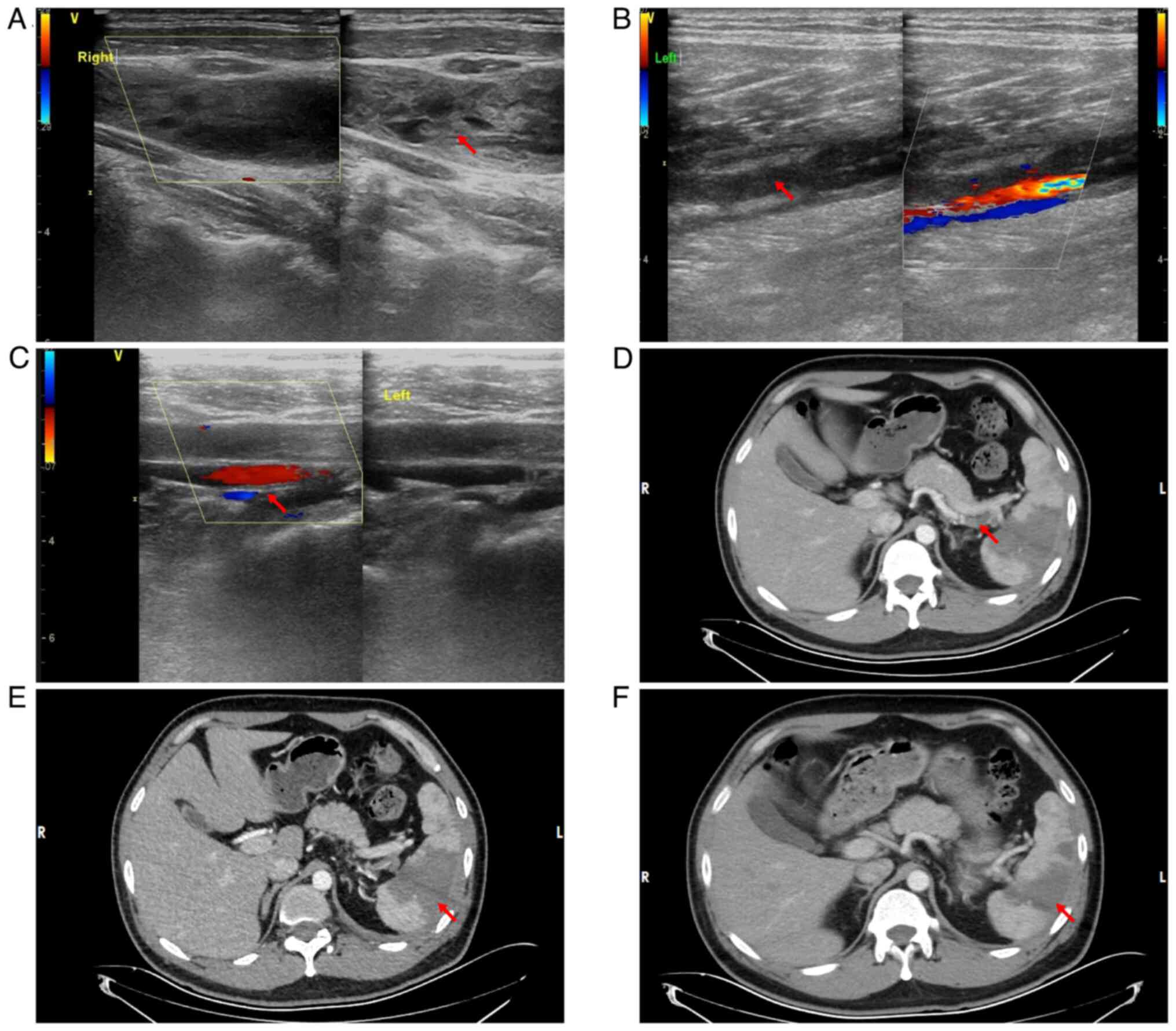

Imaging findings

Complementary vascular ultrasonography (December

2023) demonstrated extensive thromboembolic disease: Acute

thrombosis included the distal left superficial femoral vein,

popliteal vein, right internal jugular vein and bilateral posterior

tibial/peroneal veins, with venostasis evident in the remaining

lower extremity vasculature. Cervical venous evaluation identified

aneurysmal dilatation of the right internal jugular vein containing

intraluminal thrombus (Fig. 3A-C).

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT demonstrated a filling defect and

hypodense intraluminal shadow within the splenic artery distal to

the pancreatic body segment (Fig.

3D). Concomitant absence of parenchymal enhancement in a

portion of the spleen confirmed the diagnosis of splenic artery

embolism with resultant splenic infarction (Fig. 3E).

VTE score

The patient received anticoagulant treatment prior

to admission. According to the ‘Guidelines for the Quality

Evaluation and Management of VTE Prevention and Treatment in

Hospitals (2022 Edition)’ (17),

the patient did not require a VTE score assessment.

Pathological examination

Cytopathological analysis of left pleural

effusion

Malignant tumor cells were identified via left

bloody pleural effusion analysis.

H&E staining and

immunohistochemistry

Histological analysis was performed on tissue

sections fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature

for 24 h. The tissue was processed, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Sections were stained with

hematoxylin and eosin for 5 min at room temperature, following

standard protocols. The slides were examined using a light

microscope (Leica DM3000; Leica Microsystems GmbH) at a

magnification of ×400. After H&E staining, the following

results were observed: Tumor cells were found in the pleural fluid,

with an enlarged nucleoplasm ratio, deviated nuclei, pronounced

nucleoli and sparse vacuolated cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemistry (data were

obtained from medical records and are not shown) showed the

following: Transcriptional intermediary factor 1 (+); NapsinA (+);

P40 (−); cytokeratin 5/6 (−); cytokeratin (+); calretinin

mesothelium (+); desmin mesothelium (+); Wilms' tumor protein 1

(−); and Ki67-positive rate, ~10%.

Pericardial effusion analysis

Adenocarcinoma was identified via pericardial

effusion analysis.

H&E staining and

immunohistochemistry

Histological analysis was performed on tissue

sections fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature

for 24 h. The tissue was processed, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Sections were stained with

hematoxylin and eosin for 5 min at room temperature, following

standard protocols. The slides were examined using a light

microscope (Leica DM3000; Leica Microsystems GmbH) at a

magnification of ×400. After H&E staining, the following

results were observed: Tumor cells were found in the pericardial

effusion cell block, the tumor cells were arranged in an

adenoidal/papillary pattern with deeply stained, enlarged nuclei

with prominent nucleoli and cytoplasm containing mucus vacuoles

(Fig. 1D). Immunohistochemistry

(data were obtained from medical records and are not shown)

revealed the following: Cytokeratin 7 (+); thyroid transcription

factor 1 (weak +); NapsinA (+); p40 (−); and Wilms' tumor protein

(−).

Treatment method

Following the diagnosis of a malignant tumor in the

upper lobe of the left lung (adenocarcinoma; T3N2M1a and IVA

stage), the patient received regular chemotherapy at the First

People's Hospital of Suining. The chemotherapy regimen consisted of

carboplatin (0.7 g) and pemetrexed (1.0 g), which were administered

intravenously (21 days for one cycle, and 6 cycles of continuous

chemotherapy). Concurrently, based on the genetic test results

(Fig. 2A) of the patient, targeted

therapy was initiated with the third-generation tyrosine kinase

inhibitor (TKI) osimertinib (80 mg; oral once a day; long-term

maintenance therapy). Subsequently, after the patient was diagnosed

with thrombosis affecting the popliteal vein, posterior tibial

vein, peroneal vein and right intravenous vein, the patient was

prescribed rivaroxaban (10 mg twice daily; duration, 3 weeks) for

anticoagulation. Upon diagnosis of splenic artery thrombosis with

infarction, a dual therapeutic strategy was implemented: i)

Anti-infective prophylaxis, cefuroxime (4.5 g/dose every 8 h;

duration, 1 week), was empirically administered intravenously,

which targeted the encapsulated organisms [the encapsulated

microorganisms in splenic abscesses after splenic infarction are

predominantly gram-positive (staphylococci and streptococci) and

anaerobic (anaplastic bacilli and clostridia), with gram-negative

(salmonella and Escherichia coli) and fungal

(Candida) bacteria being the next most common (21)] associated with post-infarction

splenic abscess formation; and ii) weight-adjusted therapeutic

enoxaparin (8,000 IU subcutaneously every 12 h; duration, 3 months)

was initiated for anticoagulation to prevent thrombus propagation,

following International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis

guidelines for splanchnic vein thrombosis (22). After discharge, the patient

continued with rivaroxaban (15 mg twice daily) to maintain

anticoagulation, and based on the condition of the patient,

permanent maintenance anticoagulation was chosen.

Post-treatment results

The left lower abdominal pain in the patient was

markedly reduced, the splenic infarction did not progress further

and there was no secondary splenic abscess.

Abdominal CT

Contrast-enhanced abdominal imaging demonstrated

persistent non-enhancement of splenic parenchyma consistent with

established infarction. Comparative volumetric analysis indicated

interval reduction (23.4%) in the infarcted volume compared with

the baseline (December 2024; Fig. 3D

and E), which suggested partial splenic reperfusion (Fig. 3F).

Ultrasound of neck veins

Color Doppler ultrasonography identified a

persistent non-occlusive thrombus within the right internal jugular

vein (data not shown), unchanged from prior examinations (Fig. 3A).

Lower extremity vasculature

Color Doppler ultrasonography identified residual

thrombosis in the left popliteal vein and segmental branches of the

posterior tibial/peroneal veins (data not shown), indicative of

chronic thromboembolic remodeling.

Follow-up results

Following discharge, the patient remained

asymptomatic with complete resolution of abdominal pain. Serial

monitoring demonstrated progressive regression of multi-territory

thromboembolic events, with no clinical or radiographic evidence of

new thrombus formation. The last follow-up was in May 2025, and the

follow-up was conducted every 2 weeks in the form of outpatient

follow-up, and changes in the condition of the patient were

clarified by reviewing the CT of the chest and ultrasound of the

veins of the lower limbs and neck at 1-month intervals.

Discussion

Patients with lung cancer are particularly

susceptible to multi-site thrombosis due to a combination of

factors that create a hypercoagulable state (23–25).

Multi-site thrombosis is characterized by an increased tendency for

blood clot formation, which can result in thromboembolic events in

both the venous and arterial systems. A primary reason for this

heightened risk is the presence of procoagulant factors associated

with malignancy (26,27). Cancer cells, including those from

lung cancer, can express various procoagulant substances such as

TF, cancer procoagulant and heparanase. These factors serve a key

role in the activation of the coagulation cascade, which leads to

increased thrombin generation and subsequent clot formation

(3,28). Additionally, tumor cells can secrete

inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and

interleukin-1β, which further stimulate the coagulation process and

promote thrombosis. The presence of a tumor can disrupt normal

blood flow, which leads to stasis, while chemotherapy and other

cancer treatments may cause damage to the vascular endothelium and

thereby increase the risk of clot formation. The hypercoagulable

state observed in patients with cancer is also influenced by the

inflammatory response associated with malignancy. Inflammation can

lead to alterations in the balance between procoagulant and

anticoagulant factors, which shifts the equilibrium towards

increased clotting (29–31). This phenomenon is particularly

relevant in lung cancer, where the inflammatory environment created

by the tumor can heighten the risk of thromboembolic events

(3,32). Additionally, elderly patients with

lung cancer may have comorbid conditions, such as chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease or cardiovascular disease, which can

further elevate the risk of thrombosis (32,33).

The interplay of these factors leads to a markedly increased

incidence of VTE among patients with lung cancer, where previous

studies (24,27) have shown that patients with lung

cancer are four to seven times more likely to develop VTE than the

general population (34). In

summary, the elevated risk of multi-site thrombosis in patients

with lung cancer is multifactorial and arises from the direct

effects of tumor biology, the influence of cancer treatments and

the presence of comorbid conditions. According to the Khorana

scoring scale (17), which assesses

the risk of VTE in patients with cancer, the current patient was

classified as low risk on admission. The current case highlighted

limitations of the Khorana risk assessment model in the prediction

of VTE among patients with cancer. Despite being classified as low

risk using this validated scoring system, the patient developed

multi-site thrombosis, which highlighted the insufficient

sensitivity of the model in certain clinical scenarios. This

finding emphasizes the urgent need for the development of a novel

VTE risk stratification tool that incorporates dynamic variables,

including tumor histology (such as the association between lung

cancer and hypercoagulability), treatment heterogeneity and

biomarkers that reflect individual thrombotic potential. Further

research is warranted to enhance predictive accuracy for high-risk

populations such as patients with lung cancer, who exhibit high

thrombotic event rates. Vigilant thromboprophylaxis monitoring is

advised for patients with cancer, including patients stratified as

low-risk, due to the life-threatening consequences of VTE.

The L858R mutation results in the continuous

activation of EGFR, which in turn activates several downstream

signaling pathways. These include the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways (35,36).

The Ras pathway is particularly important as it regulates cell

proliferation, survival and migration, which are key processes in

cancer progression and metastasis (35,36).

The activation of these pathways can lead to increased expression

of pro-coagulant factors, which contribute to a hypercoagulable

state.

Previous studies have suggested that the interaction

between EGFR signaling and coagulation pathways can influence

cancer progression. For example, the activation of EGFR can lead to

the upregulation of ligands that promote TF expression and thereby

enhance the pro-coagulant state in tumors (37,38).

The crosstalk is particularly relevant in the context of KRAS

mutations, where both mutations (KRAS and EGFR) can synergistically

promote tumor growth and thrombosis (39). The presence of the EGFR-L858R

mutation in patients with NSCLC may be associated with an increased

risk of thromboembolic events. This association is particularly

important for clinicians to consider when managing patients with

the EGFR-L858R mutation, as the hypercoagulable state can

complicate treatment and increase the risk of adverse outcomes.

However, a previous study, which included 310 patients diagnosed

with lung adenocarcinoma, reported that patients with EGFR

mutations had a HR of 0.46 (95% CI, 0.23–0.94) for VTE, which

suggests a protective effect against thrombosis compared with

patients with wild-type EGFR. Additionally, treatment with TKIs

further reduced the risk of VTE, with an HR of 0.42 (95% CI,

0.29–0.79) when compared with other treatment strategies that did

not include TKIs. This finding suggested that the presence of the

EGFR mutation was associated with a lower incidence of thrombosis

and the therapeutic approach using TKIs may enhance this protective

effect (7). The current patient was

diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma in October 2024, following the

identification of lung adenocarcinoma cells in pleural effusion via

immunohistochemistry. The patient exhibited pleural and lymph node

metastases, which indicated advanced lung cancer. Subsequent

genetic testing demonstrated the presence of the EGFR-L858R

mutation, which prompted the initiation of targeted therapy with

the TKI osimertinib. However, in October 2024, chest CT indicated

tumor progression and the emergence of pericardial metastasis,

which led to the conclusion that single-agent targeted therapy had

failed. Consequently, the treatment plan was modified to include a

combination of chemotherapy (carboplatin and pemetrexed) and

targeted therapy (osimertinib). At this juncture, a venous color

Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs had already detected

thrombosis, and rivaroxaban (10 mg twice daily) was prescribed for

anticoagulation. The anticoagulation strategy proved ineffective,

as novel thrombosis was identified when the patient was admitted to

the First People's Hospital of Suining in November 2024. The role

of the EGFR-L858R mutation in thrombosis among patients with lung

cancer remains unclear. A previous study has suggested that the

EGFR-L858R mutation may reduce the incidence of thrombotic events,

while other studies have indicated an increased incidence

associated with the EGFR-L858R mutation (40). Based on the observations in the

current patient, we hypothesized that the EGFR-L858R mutation may

exert a protective effect in thrombosis among patients with lung

cancer. Notably, the patient did not experience thrombosis prior to

the initiation of treatment with TKI inhibitors; however, following

the commencement of TKI therapy, venous thrombosis developed in the

lower extremities, despite treatment with anticoagulants. This

phenomenon may arise from two potential factors: Firstly, the

condition of the patient progressed during treatment, which led to

pericardial metastasis and notable pericardial effusion. This

prolonged state likely impaired systemic circulation, which

resulted in slowed blood flow and increased coagulability.

Secondly, the treatment approach for the patient was modified

following the development of pericardial effusion. The patient was

transitioned to a regimen that included chemotherapy (carboplatin

and pemetrexed) combined with targeted therapy (osimertinib).

Previous studies have indicated that platinum-based antitumor

agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin and lopatin may

elevate the risk of VTE in patients with lung cancer, particularly

with regard to catheter-related thrombosis (41,42).

In summary, the antithrombotic effect of the EGFR-L858R mutation

appears to be counteracted by TKI-induced endothelial dysfunction

and pharmacokinetic disturbances. Based on the observations from

the present case, it is necessary to revise current guidelines

(17) to include the following: i)

EGFR mutation status in VTE risk models; ii) TKI-specific

anticoagulation algorithms; and iii) protocolized cytokine

monitoring during metastasis.

MPE markedly impacts hemodynamics and coagulation

properties in patients with lung cancer. The presence of MPE can

lead to alterations in blood flow dynamics due to the accumulation

of fluid in the pericardial space, which can compress the heart and

impede its ability to pump effectively (43–45).

This condition can result in cardiac tamponade, where the pressure

from the fluid prevents the heart chambers from filling properly,

which leads to reduced cardiac output and compromised blood flow to

vital organs (46). In terms of

coagulation properties, patients with lung cancer and MPE often

exhibit a hypercoagulable state. A hypercoagulable state is

characterized by changes in plasma fibrin clot properties, which

can include increased clot density and altered permeability

(47–49). A single study has reported that

patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy exhibited higher

levels of D-dimer, a marker of fibrin degradation, which indicated

increased fibrinolytic activity (50). Additionally, chemotherapy has been

associated with changes in clot structure, such as increased clot

permeability and prolonged clot lysis time, which can contribute to

thromboembolic complications (51).

The presence of MPE can also influence the activity of TF, which is

a key initiator of the coagulation cascade. In patients with lung

cancer, the activity of microparticle-associated TF can be altered,

which leads to an imbalance between coagulation activation and

fibrinolytic potential. This imbalance may predispose patients to

VTE, which is notably more common in patients with lung cancer

compared with the general population (52). The hypercoagulable state is further

exacerbated by the presence of tumor-derived factors that promote

clot formation and inhibit fibrinolysis, which contributes to the

overall risk of thrombotic events in patients with lung cancer

(53). In November 2024, the

patient developed chest pain, exertional dyspnea and fatigue.

Pericardiocentesis and catheter drainage were performed following

detection of a notable amount of pericardial effusion via chest CT.

Lung adenocarcinoma cells were identified in the pericardial

effusion. The pericardial metastasis of the patient resulted in a

substantial accumulation of pericardial effusion. This process was

gradual and continuous, which markedly impacted the systemic

circulation of the patient, and exacerbated the hypercoagulable

state commonly associated with lung cancer. Consequently, the

process led to thrombosis in multiple locations, particularly

arterial thrombosis, including splenic artery thrombosis. Although

pericardiocentesis and catheter drainage were performed to

alleviate the cardiac tamponade in the patient, the effects on the

circulatory state are unlikely to improve in the short term.

In some cases, patients with lung cancer undergoing

chemotherapy may experience acute complications such as splenic

infarction due to embolic events, which can be precipitated by the

underlying malignancy and the treatment (54). Furthermore, the anatomical and

physiological characteristics of the spleen, along with the

vascular supply, can make it susceptible to thrombotic events. The

spleen is typically well-protected from non-hematological

metastasis and splenic artery thrombosis is a rare occurrence

(21,55). However, when splenic artery

thrombosis does occur, it is often part of a broader pattern of

vascular complications associated with malignancies, including lung

cancer (56). In summary, lung

cancer can cause splenic artery thrombosis primarily through the

induction of a hypercoagulable state, either due to the malignancy

itself or as a consequence of chemotherapy. This can lead to

thrombus formation in the splenic artery, which results in

complications such as splenic infarction. The splenic artery, which

is a singular vessel, is particularly susceptible to

thromboembolism, which can result in splenic infarction (10). The current patient experienced

splenic artery thromboembolism and subsequent splenic infarction, a

clinical occurrence that is extremely rare. Notably, splenic artery

thromboembolism and splenic infarction occurred despite

anticoagulation therapy. To the best of our knowledge, there is a

lack of pertinent research reports on this phenomenon, which

necessitates further research on the underlying causes. The causes

of this phenomenon were analyzed and summarized as follows: i)

Hypercoagulable state: Lung cancer may influence the coagulation

status of patients through various mechanisms, which leads to a

persistent hypercoagulable state; ii) cardiac embolism resulting

from pericardial effusion: The patient had a notable history of

MPE, which severely compromised blood circulation and contributed

to thrombosis formation at multiple sites, including the splenic

artery; and iii) treatment modalities: TKIs and platinum-based

chemotherapy agents can elevate the risk of thrombosis in patients

with lung cancer. Additionally, the use of deep vein

catheterization for chemotherapy may lead to catheter-related

thrombosis, as evidenced by the current patient undergoing internal

jugular vein catheterization for chemotherapy. Subsequent cervical

venous color ultrasound revealed thrombosis in the internal jugular

vein.

Venous thrombosis was identified in the lower

extremity and jugular veins in December 2024 via color ultrasound.

In response, anticoagulation with rivaroxaban at a dosage of 10 mg

twice a day was initiated; however, new thrombotic sites continued

to emerge. Following an adjustment of the anticoagulant dosage to

15 mg rivaroxaban twice a day, marked dissolution and disappearance

of the thrombus were observed, with no further occurrences of

thrombosis. This observation led to the conclusion that the initial

anticoagulant dosage was insufficient. Additionally, as the

anticoagulant dosage was modified, the D-dimer levels of the

patient gradually decreased to normal levels, which indicated a

positive association between D-dimer levels and thrombosis, as well

as a potential predictive value regarding anticoagulant efficacy.

Nonetheless, further research is necessary to substantiate the

findings of the present case report.

It is extremely rare for patients with lung

adenocarcinoma and EGFR-L858R mutations to develop multiple

thromboses that lead to splenic infarction. This phenomenon may be

associated with hypercoagulability, cardiac tamponade and genetic

mutations inherent to patients with lung cancer, exacerbated by

factors such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and insufficient

anticoagulation dosing. The present case highlights the complex

interplay between oncogenic drivers and hemostatic regulation. The

authors propose three clinical practice modifications: i) Mandatory

thrombophilia screening for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC

initiating TKIs; ii) implementation of quantitative anti-factor Xa

monitoring for patients with direct oral anticoagulants-treated

cancer; and iii) development of EGFR mutation-specific VTE risk

assessment tools. Further research is warranted to explore the role

of PI3K inhibitors in mitigating TKI-associated thrombosis while

preserving antitumor efficacy.

The present case underscored the paradoxical

thrombotic risk in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC undergoing

targeted therapy, highlighted the insufficiency of the Khorana

score in molecularly defined cohorts, and established visceral

thrombosis screening as a critical component of care in EGFR-mutant

patients with pericardial effusion. It mandates revision of VTE

risk stratification frameworks to incorporate oncogenic driver

status, treatment-specific factors and dynamic biomarkers, while

advocating for intensified anticoagulation protocols in this

high-risk subgroup.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Suining Health Science

and Technology Project (grant no. 24CJDFB38).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YM, MW, HZ and XW conributed to the conception and

design of the study. QW and ZW performed the acquisition, analysis

and interpretation of data. QW and ZW confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient to

publish the present case report findings and process medical

records.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ruiz-Artacho P, Lecumberri R,

Trujillo-Santos J, Font C, Lopez-Nunez JJ, Peris ML, Pedroche CD,

Lobo JL, Jimenez LL, Reyes RL, et al: Cancer histology and natural

history of patients with lung cancer and venous thromboembolism.

Cancers (Basel). 14:41272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hojbjerg JA, Bentsen KK, Vinholt PJ,

Hansen O, Jeppesen SS and Hvas AM: Increased in vivo thrombin

generation in patients with localized non-small cell lung cancer

unfit for surgery. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost.

29:107602962311528972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lobo FT, Alves R, Judas T and Delerue MF:

Marantic endocarditis and paraneoplastic pulmonary embolism. BMJ

Case Rep. 2017:bcr20172202172017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lysov Z, Swystun LL, Kuruvilla S, Arnold A

and Liaw PC: Lung cancer chemotherapy agents increase procoagulant

activity via protein disulfide isomerase-dependent tissue factor

decryption. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 26:36–45. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu B, Zhang J, Tang S, Hou J and Ma M:

Comparison of two types of catheters through femoral vein

catheterization in patients with lung cancer undergoing

chemotherapy: A retrospective study. J Vasc Access. 19:651–657.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dou F, Li H, Zhu M, Liang L and Zhang Y,

Yi J and Zhang Y: Association between oncogenic status and risk of

venous thromboembolism in patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

Respir Res. 19:882018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Davidsson E, Murgia N, Ortiz-Villalon C,

Wiklundh E, Skold M, Kolbeck KG and Ferrara G: Mutational status

predicts the risk of thromboembolic events in lung adenocarcinoma.

Multidiscip Respir Med. 12:162017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schattner A, Adi M, Kitroser E and

Klepfish A: Acute splenic infarction at an academic general

hospital over 10 years. Medicine (Baltimore). 94:e13632015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abdallah A, Kaur V, Mahmoud F and Motwani

P: Image diagnosis: Splenic infarction associated with oral

contraceptive pills in a healthy young woman. Perm J. 21:16–071.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

He YA, Wang DX, Lin LJ and Zheng CQ:

Report of a case of splenic infarction and review of the

literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 29:239–240. 2020.

|

|

11

|

Yin X, He T, Hu H, Sun J and Xu Y: Report

of a case of splenic arteriovenous embolism resulting in necrosis

of the stomach, spleen and pancreatic body tail. Chin J Mod

Operative Surg. 28:434–435. 2024.(In Chinese).

|

|

12

|

Brett AS, Azizzadeh N, Miller EM, Collins

RJ, Seegars MB and Marcus MA: Assessment of clinical conditions

associated with splenic infarction in adult patients. JAMA Intern

Med. 180:1125–1128. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fang Q, Tang M, Chang X, He M, Liu Y and

Yin S: Construction and assessment of a Nomogram model for lung

cancer patients with concurrent deep vein thrombosis. Chinese

Journal of New Clinical Medicine. 17:1019–1025. 2024.(In

Chinese).

|

|

14

|

Square F, Fu XG and Li YB: Deep vein

thrombosis in the lower limbs of elderly lung cancer patients and

its influencing factors. J Pract Cancer. 39:612–614. 2024.

|

|

15

|

Di W, Xu H, Ling C and Xue T: Early

identification of lung cancer patients with venous thromboembolism:

Development and validation of a risk prediction model. Thromb J.

21:952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang X and Zhi X: Introduction to the 8th

edition of the TNM Classification of the Internatinoal Association

for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC). Chin J Tharac Surg. 3:70–76.

2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Writing Expert Group National Expert

Committee on Capacity Building Project for Prevention and Treatment

of Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis: Quality Evaluation

and Management Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Venous

Thromboembolism in Hospitals (2022 Edition). Natl Med J China.

102:3338–3348. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

18

|

Li J, Yan S, Zhang X, Xiang M, Zhang C, Gu

L, Wei X, You C, Chen S, Zeng D and Jiang J: Circulating D-dimers

increase the risk of mortality and venous thromboembolism in

patients with lung cancer: A systematic analysis combined with

external validation. Front Med (Lausanne). 9:8539412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sanfilippo KM, Fiala MA, Feinberg D,

Tathireddy H, Girard T, Vij R, Di Paola J and Gage BF: D-dimer

predicts venous thromboembolism in multiple myeloma: A nested

case-control study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 7:1022352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yamanaka Y, Sawai Y and Nomura S:

Platelet-derived microparticles are an important biomarker in

patients with cancer-associated thrombosis. Int J Gen Med.

12:491–497. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lin C, Xu XQ, He SD and Hong T: Clinical

analysis of 21 cases of splenic infarction. J Chin Acad Med Sci.

36:321–323. 2014.

|

|

22

|

Levy JH, Shaw JR, Castellucci LA, Connors

JM, Douketis J, Lindhoff-Last E, Rocca B, Samama CM, Siegal D and

Weitz JI: Reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: Guidance from the

SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 22:2889–2899. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cao L, Duan Z, Zhang T, Yuan R and Wang G:

Progress of Study on Malignant Tumors and Thrombogenesis. Progress

in Modern Biomedicine. 16:2187–2190. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

24

|

Wei R: Risk factors and treatment analysis

of combined venous thromboembolism in lung cancer chemotherapy

patients. J Clin Med. 4:15085–15086. 2017.(In Chinese).

|

|

25

|

Khorana AA, Mackman N, Falanga A, Pabinger

I, Noble S, Ageno W, Moik F and Lee AYY: Cancer-associated venous

thromboembolism. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 8:112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cheng Y, Cai X and Liu JW: Malignant

tumours and thrombosis. J Clin Oncol. 15:376–379. 2010.

|

|

27

|

Wang D, Xiong W and Han F: Advances in the

pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism associated with lung cancer.

Chinese Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care. 22:135–141.

2023.(In Chinese).

|

|

28

|

Zhang M, Wu S and Hu C: Do lung cancer

patients require routine anticoagulation treatment? A

meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 48:3000605198969192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Syrigos K, Grapsa D, Sangare R,

Evmorfiadis I, Larsen AK, Van Dreden P, Boura P, Charpidou A,

Kotteas E, Sergentanis TN, et al: Prospective assessment of

clinical risk factors and biomarkers of hypercoagulability for the

identification of patients with lung adenocarcinoma at risk for

cancer-associated thrombosis: The observational ROADMAP-CAT study.

Oncologist. 23:1372–1381. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tang L, Liu XQ, Chen J, Bai Y, Li J, Zhang

YD and Liu QX: Reducing the incidence of postoperative venous

thromboembolism in patients with lung cancer. China Health Quality

Management. 28:66–70. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

31

|

Hao EE and Jia Q: Correlation between

coagulation function and tumour metastatic recurrence in non-small

cell lung cancer patients. Thromb Haemost. 28:967–969. 2022.

|

|

32

|

Cukic V and Ustamujic A: Lung cancer and

pulmonary thromboembolism. Mater Sociomed. 27:351–353. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Takemoto T, Soh J, Ohara S, Fujino T, Koga

T, Nishino M, Hamada A, Chiba M, Shimoji M, Suda K, et al: The

prevalence and risk factors associated with preoperative deep

venous thrombosis in lung cancer surgery. Surg Today. 51:1480–1487.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Meikle CK, Meisler AJ, Bird CM, Jeffries

JA, Azeem N, Garg P, Crawford EL, Kelly CA, Gao TZ, Wuescher LM, et

al: Platelet-T cell aggregates in lung cancer patients:

Implications for thrombosis. PLoS One. 15:e02369662020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Minnelli C, Cianfruglia L, Laudadio E,

Mobbili G, Galeazzi R and Armeni T: Effect of

epigallocatechin-3-Gallate on EGFR signaling and migration in

non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 22:118332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Saryeddine L, Zibara K, Kassem N, Badran B

and El-Zein N: EGF-induced VEGF exerts a PI3K-dependent positive

feedback on ERK and AKT through VEGFR2 in hematological in vitro

models. PLoS One. 11:e01658762016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hamza MS and Mousa SA: Cancer-Associated

thrombosis: Risk factors, molecular mechanisms, future management.

Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 26:10760296209542822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Akinbo DB and Ajayi OI: Thrombotic

pathogenesis and laboratory diagnosis in cancer patients, an

update. Int J Gen Med. 16:259–272. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xiao M, Pang C, Xiang S, Zhao Y, Wu X, Li

M, Du F, Chen Y, Wang F, Wen Q, et al: Comprehensive

characterization of B7 family members in NSCLC and identification

of its regulatory network. Sci Rep. 13:43112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Durica SS: Venous thromboembolism in the

cancer patient. Curr Opin Hematol. 4:306–311. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen P, Wan G and Zhu B: Incidence and

risk factors of symptomatic thrombosis related to peripherally

inserted central catheter in patients with lung cancer. J Adv Nurs.

77:1284–1292. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Feng Y, Fu Y, Xiang Q, Xie L, Yu C and Li

J: Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene promoter 4G/5G

polymorphism and risks of peripherally inserted central

catheter-related venous thrombosis in patients with lung cancer: A

prospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 29:6431–6439. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gao S, Sun S and Song J: Recent advances

in the pathogenesis and treatment of malignant pericardial

effusion. China Research Hospitals. 12:62–67. 2025.(In

Chinese).

|

|

44

|

Hu YX, Jiang Y, Yan J and Liu JL:

Treatment and prognosis of lung cancer with malignant pericardial

effusion in emergency setting. Acad J Sec Mil Med Univ. 30:583–585.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Suwanwongse K and Shabarek N: Atrial

flutter as an initial presentation of malignant pericardial

effusion caused by lung cancer. Cureus. 12:e117122020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Dequanter D, Lothaire P, Berghmans T and

Sculier JP: Severe pericardial effusion in patients with concurrent

malignancy: A retrospective analysis of prognostic factors

influencing survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 15:3268–3271. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Sundar R, Soong R, Cho B, Brahmer JR and

Soo RA: Immunotherapy in the treatment of non-small cell lung

cancer. Lung Cancer. 85:101–109. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Vakamudi S, Ho N and Cremer PC:

Pericardial effusions: Causes, diagnosis, and management. Prog

Cardiovasc Dis. 59:380–388. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Qiu J, Xu L, Zeng X, Wu Z, Wang Y, Wang Y,

Yang J, Wu H, Xie Y, Liang F, et al: NUSAP1 promotes the metastasis

of breast cancer cells via the AMPK/PPARgamma signaling pathway.

Ann Transl Med. 9:16892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hu ZG, Hu K, Li WX and Zeng FJ: Prognostic

factors and nomogram for cancer-specific death in non small cell

lung cancer with malignant pericardial effusion. PLoS One.

14:e02170072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Goel K, Ateeli H, Ampel NM and L'Heureux

D: Patient with small cell lung carcinoma and suspected right upper

lobe abscess presenting with a purulent pericardial effusion. Am J

Case Rep. 17:523–528. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chiruvella V, Ullah A, Elhelf I, Patel N

and Karim NA: Would the addition of immunotherapy impact the

prognosis of patients with malignant pericardial effusion? Front

Oncol. 12:8711322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Krolczyk G, Zabczyk M, Czyzewicz G, Plens

K, Prior S, Butenas S and Undas A: Altered fibrin clot properties

in advanced lung cancer: Impact of chemotherapy. J Thorac Dis.

10:6863–6872. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Koyama N, Tomoda K, Matsuda M, Fujita Y,

Yamamoto Y, Hontsu S, Tasaki M, Yoshikawa M and Kimura H: Acute

bilateral renal and splenic infarctions occurring during

chemotherapy for lung cancer. Intern Med. 55:3635–3639. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang YL and Fan XZ: A case of splenic

infarction initiated by upper abdominal pain. Clinical Focus.

29:209–210. 2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

56

|

Grant-Freemantle MC, Bass GA, Butt WT and

Gillis AE: Splenectomy for isolated splenic metastasis from primary

lung adenocarcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 13:e2332562020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|