Introduction

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma is an

uncommon and highly aggressive form of primitive extranodal

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 3% of all brain tumors.

Its incidence has increased in recent decades, accounting for

0.47/100,000 people, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1.7, with

the highest rates observed in patients over 60 (1). The main known risk factor for PCNSL is

immunodeficiency, whether primary or acquired, due to HIV infection

or organ transplants (2–4). The most frequent histological subtype

of PCNSL is Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma, which comprises 95% of

cases (5). PCNSL has been reported

to occur in brain parenchyma, spinal cord, meninges, and ocular

tissues, although the most common site is supratentorial (5). Distinctive topographic features

include the involvement of the midline structures, such as the

corpus callosum and fornix, and locations adjacent to cerebrospinal

fluid spaces, in contact with the ependymal surface (5). Infratentorial locations in the

brainstem and cerebellum or involvement of cranial nerves are

uncommon (5). This site variability

may explain the pleomorphic symptoms, with headache and seizures

being the most common (6). Cerebral

stereotaxic biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis,

although it should be performed without prior corticosteroid

treatment, which can promote lymphocellular necrosis and compromise

accurate diagnosis (5–7). The usual morphological features

include large necrotic areas with evidence of neoplastic

lymphocytes invading the surrounding parenchyma. This proliferation

consists of pleomorphic and atypical B lymphoid cells with large

round nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and many mitoses (8). Additionally, mixed reactive

inflammatory cells, including T lymphocytes, are found among

B-cells (9). The angiocentric

growth pattern, with vessels surrounded by neoplastic lymphocytes,

can be a significant morphological feature (8,10).

Using Hans' algorithm, two main immunohistochemical subtypes can be

identified: Germinal and Non-Germinal Centre B-cell (11). Specifically, the GCB subtype

exhibits immunoreactivity for CD10 and BCL-6, while Non-GCB can be

further subdivided into Activated B-Cell (ABC) with

immunoreactivity for MUM1 and an unclassified subtype (11). The GCB subtype has a reportedly

better clinical outcome compared to Non-GCB (11). The neuroradiological key points for

diagnosing PCNSL include evidence of solid, sometimes multiple,

supratentorial masses with low Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC)

on diffusion-weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) sequences

and homogeneous enhancement after Gadolinium-diethylenetriamine

pentaacetic acid (DTPA) administration. In immunocompromised

patients, the MRI pattern is less specific, often revealing

intralesional hemorrhage or necrosis with ring-like enhancement

after Gadolinium administration (12). This retrospective multidisciplinary

study aims to analyze a cohort of 23 patients affected by

PCNSL-DLBCL, comparing their clinical, pathological, and

neuroradiological features and evaluating the potential effects of

these variables on OS.

Materials and methods

Patients and tumor specimens

Clinical and pathological data from 23 patients

diagnosed with PCNSL-DLBCL between January 2012 and November 2024

were obtained through neurosurgical procedures and collected from

the Department of Human Pathology of Adult and Developmental Age,

Section of Pathological Anatomy, University of Messina, A.O.U.

Gaetano Martino (Messina, Italy). The analysis was performed

according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration

of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). Before the surgical

procedures, all patients provided written, anonymized, and informed

consent. Pathology reports and medical records were thoroughly

reviewed. Patients' initials and other personal identifiers were

removed from all images. The Institutional Review Board of the

University Hospital of Messina (Messina, Italy) approved this study

vide protocol no. 47/19 of May 2, 2019. Data collected included age

at diagnosis, gender, and site of disease, classified as

supratentorial or infratentorial. MRI images of the aforementioned

patients were collected from the Department of Biomedical, Dental,

Morphological, and Functional Imaging Sciences, Section of

Neuroradiology, University of Messina, A.O.U. Gaetano Martino

(Messina, Italy), including T1 and T2 weighted images, Late

Gadolinium Enhancement (LGE) imaging, and Diffusion-weighted

Imaging (DWI), considering the ADC as a surrogate for neoplastic

cellularity and the mean Ki-67 value of enhancement as an

expression of blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage. After surgical

procedures, all patients underwent radio-chemotherapy with four

cycles of methotrexate, cytarabine, rituximab, and prednisolone;

additionally, complementary whole-brain radiotherapy (30–36 Gy) was

performed.

Immunohistochemical analysis

All tumor specimens were fixed in 10%

neutral-buffered-formalin at room temperature for 24 h and

paraffin-embedded. Five-micron-thick sections were obtained from

corresponding tissue blocks for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

routine staining. Parallel sections from the same tissue blocks

were cut for immunohistochemical procedures; slides were

deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated, and treated with 3% hydrogen

peroxide for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase; they were then

washed in deionized water thrice (10 min each time). Sections were

incubated with normal sheep serum to prevent nonspecific adherence

of serum proteins for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter,

sections were again washed with deionized water and incubated for

30 min at 37°C with the working dilution suggested by the ROCHE

manufacturer for each commercially obtained monoclonal antibody.

The following monoclonal antibodies against CD20 (L26), PAX5

(SP34), CD79a (SP18), GFAP (EP672Y), BCL-2 (124), Ki-67 (MIB 1),

CD10 (SP67), BCL-6 (GI191E/A8), and MUM1 (EP190) were used.

Subsequently, sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline

solution (PBS) at pH 7.2–7.4 and incubated with corresponding

secondary antibodies (1:300; Abcam, code no. ab7064) for 20 min at

room temperature, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled

secondary antibody for 30 min and developed with diaminobenzidine

tetrahydrochloride, counterstained with hematoxylin using the ULTRA

Staining system (Ventana Medical Systems). Negative controls were

obtained by omitting the specific antisera and substituting PBS for

the primary antibody. The immunohistochemical staining for each

sample was independently scored by two pathologists, who were

blinded to patient outcomes and clinical findings, using a Zeiss

Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH) at 40× objective

magnification. Staining for CD10, BCL-6, and MUM-1 was considered

positive when >30% of cells were positively stained; staining

for BCL-2 was considered positive when >50% of cells were

positively stained. Ki-67 expression was evaluated as high when the

percentage of positive neoplastic cells was >50%, counting at

least 1,000 cells.

Immunophenotype classification

Two main subtypes of PCNSL-DLBCL were identified

through the combined expression of CD10, BCL-6, and MUM-1. All

CD10+ tumor phenotypes were classified as the GCB subgroup. Samples

with CD10-BCL-6+ MUM-1+ and CD10-BCL-6-MUM-1+ profiles were

considered Non-GCB subtypes.

MRI protocol

All MRI examinations were performed in the clinical

routine using a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (Ingenia Philips Healthcare,

Best, The Netherlands). The MRI protocol included: axial DWI

single-shot spin-echo (SE) echo planar sequence (repetition

time (TR)/echo time (TE): 3000/85 ms, flip angle (FA): 90°, SL:

71.6 mm, slice thickness (ST): 5 mm, field of view (FOV): 230 mm).

Diffusion-sensitizing gradients were applied sequentially in the x,

y, and z directions with b factors of 0 and 1,000 s/mm2.

ADCs were automatically calculated by the MR scanner and displayed

as corresponding ADC maps: axial SE T1-weighted sequence

(TR: 633 ms, TE: 15 ms, FA: 69°, SL: 71 mm, ST: 5.50 mm); axial

fast SE (FSE) T2-weighted sequence (TR: 4848 ms, TE: 100 ms,

FA: 90°, SL: 71.60 mm, ST: 5 mm); 3D fluid-attenuated inversion

recovery (FLAIR-3D) sequence (TR: 5200 ms, TE: 305 ms, FA: 90°,

SL: 21.44 mm); postcontrast 3D T1-weighted gradient-echo (GE)

sequence (TR/TE: 25/4.58 ms, FA: 30°, 1-mm section thickness,

and 230 mm FOV). A standard dose (0.1 mmol/kg body weight) of

gadoteric acid (Gd-DOTA, Dotarem; Laboratoire Guerbet,

Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) was injected intravenously.

Image analysis

All images were available in digital format. Image

analysis was performed on a Philips Portal Viewer. T2 and ADC maps

were co-registered with the post-contrast T1-weighted 3D-gradient

echo sequence. Image analysis was conducted by two independent

neuroradiologists, who drew a circular Region-of-Interest (ROI)

within the tumor, avoiding regions suspected of intralesional

hemorrhage or necrosis. Three sets of data were collected,

including ADC, T2 signal, and enhancement evaluation. A

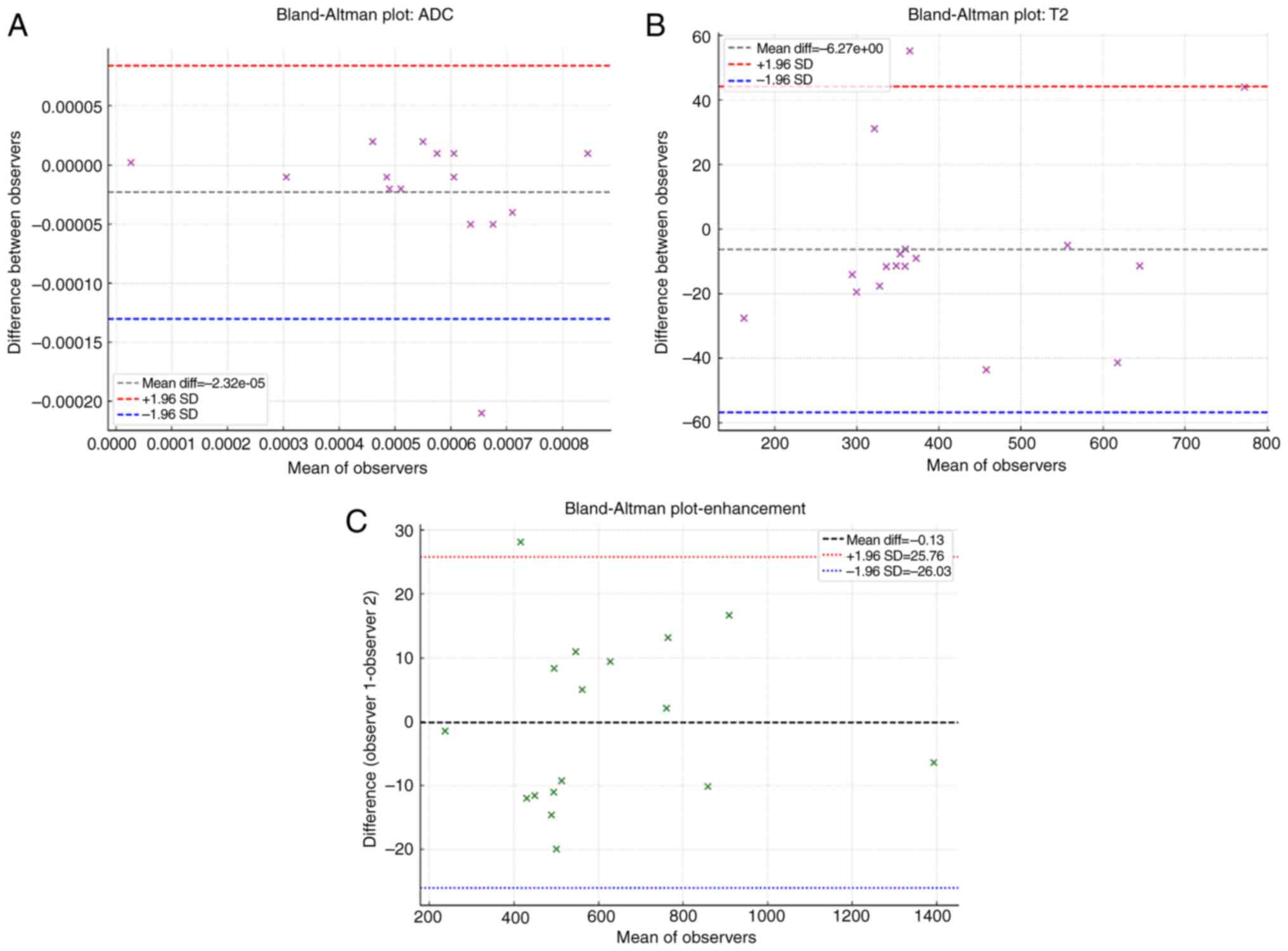

Bland-Altman plot was used to assess agreement between the two

observers (Fig. 1). Good

inter-observer agreement was demonstrated for all MRI parameters:

ADC (Fig. 1A), T2 signal (Fig. 1B), and enhancement (Fig. 1C).

Statistical analysis

The association between the immunohistochemical

profile of tumors, clinicopathological (age, sex, and site of

disease), and neuroradiological features was subjected to

univariate analysis with Fisher's exact test. Multivariate analysis

was performed using the Cox regression model to study the

independent effects of variables on OS, defined as the time from

diagnosis to death. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated.

All statistical evaluations were performed using MedCalc version

10.2.0.0 (MedCalc Software). Results were considered statistically

significant when P<0.05.

Results

Histology and immunohistochemical

results

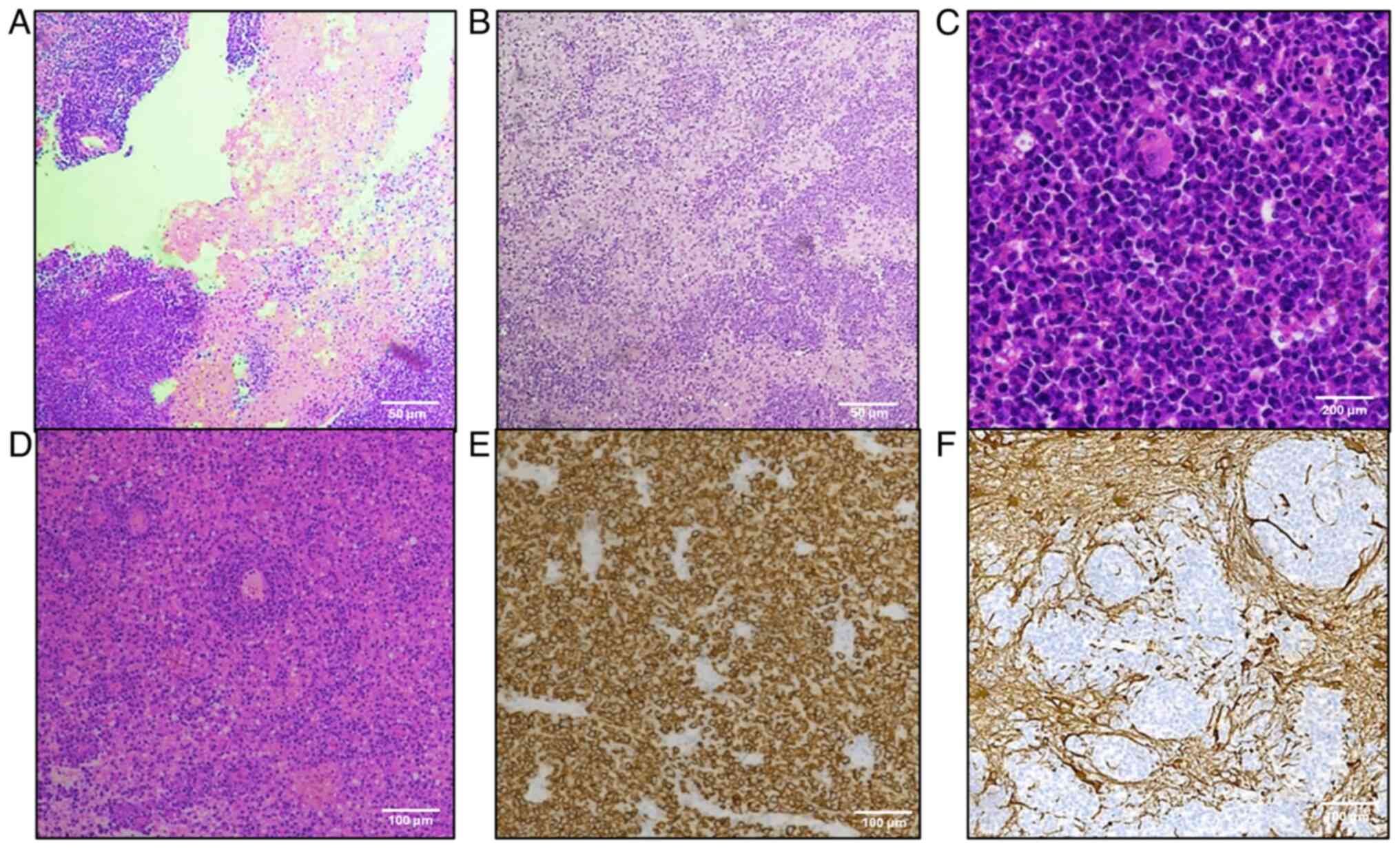

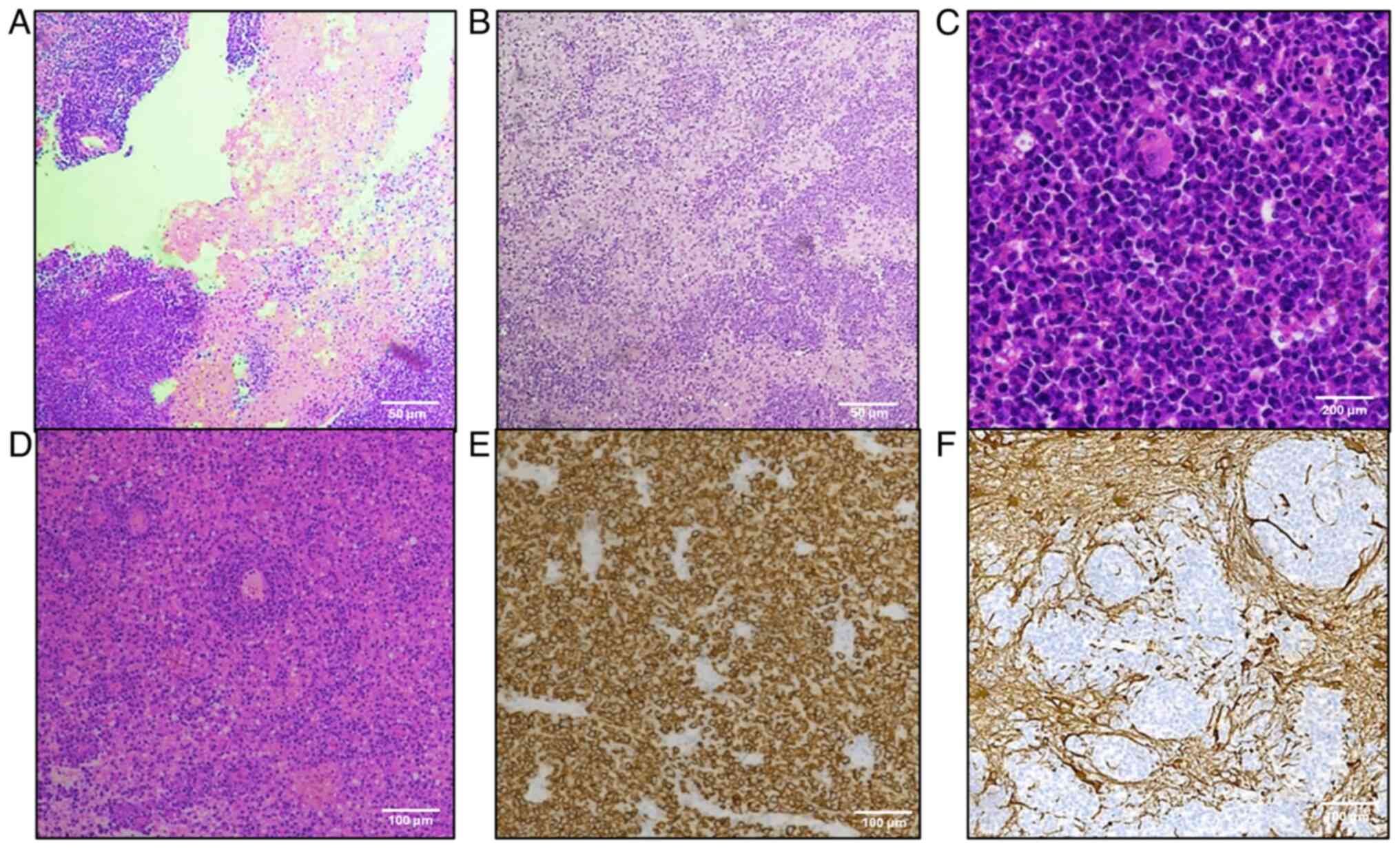

All cases exhibited typical morphological features

of PCNSL-DLBCL in hematoxylin and eosin sections (Fig. 2). B-cell markers (CD20, PAX5, and

CD79a) demonstrated cell membrane staining in all specimens.

Twenty-one out of 23 cases indicated nuclear BCL-2

immunoreactivity. Lymphoid clusters were GFAP negative, with

infiltration of GFAP-positive adjacent nervous tissue. In 17 out of

23 specimens, nuclear immunoreactivity for c-Myc was documented in

>40% of tumor cells. According to Hans' algorithm, 6 samples

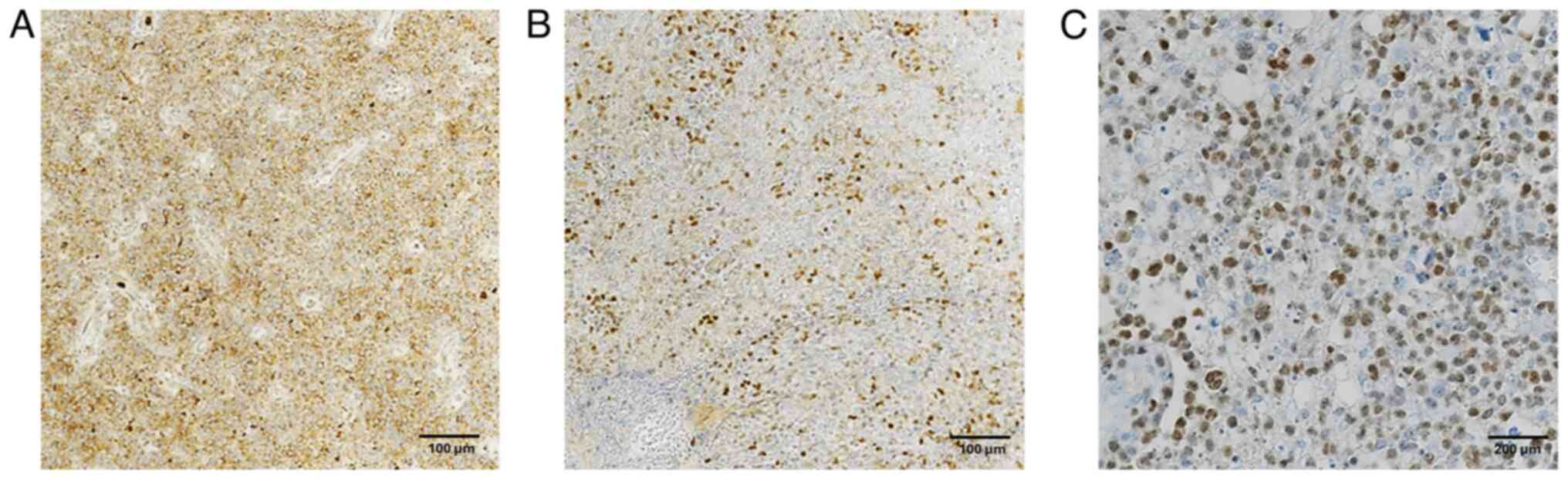

(26%) were classified as GC: 4 (67%) were CD10+ BCL-6+ MUM-1+; 2

(33%) were CD10+ BCL-6+ MUM-1-. Seventeen tumors (74%) were

classified as Non-GCB: 16 (94%) were CD10-BCL-6+ MUM-1+; 1 (6%) was

MUM-1+ only (Fig. 3).

| Figure 2.Primitive diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: Histologic and immunohistochemical features. (A) Large

areas of geographical necrosis (hematoxylin and eosin staining;

magnification, ×100; scale bar, 50 µm). (B) Clusters of tumor cells

invading brain parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin staining;

magnification, ×100; scale bar, 50 µm). (C) Atypical B cells with

big, round, vesicular nuclei and numerous mitoses (hematoxylin and

eosin staining; magnification, ×400; scale bar, 200 µm). (D)

Angiocentric pattern of growth (hematoxylin and eosin staining;

magnification, ×100; scale bar, 100 µm). (E) Diffuse cell membrane

CD20-positivity (Mayer's hemalum nuclear counterstain;

magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm). (F) GFAP− tumor

cells invading GFAP+ brain parenchyma (Mayer's hemalum

nuclear counterstain; magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm).

GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein. |

Clinicopathological and

neuroradiological features

Of the total of 23 patients, 20 (87%) were ≥60, and

3 (13%) were <60, with a median age of 66 and a mean age of

65.7; 8 patients (35%) were male and 15 (65%) female.

Supratentorial disease was documented in 18 cases (78%), and

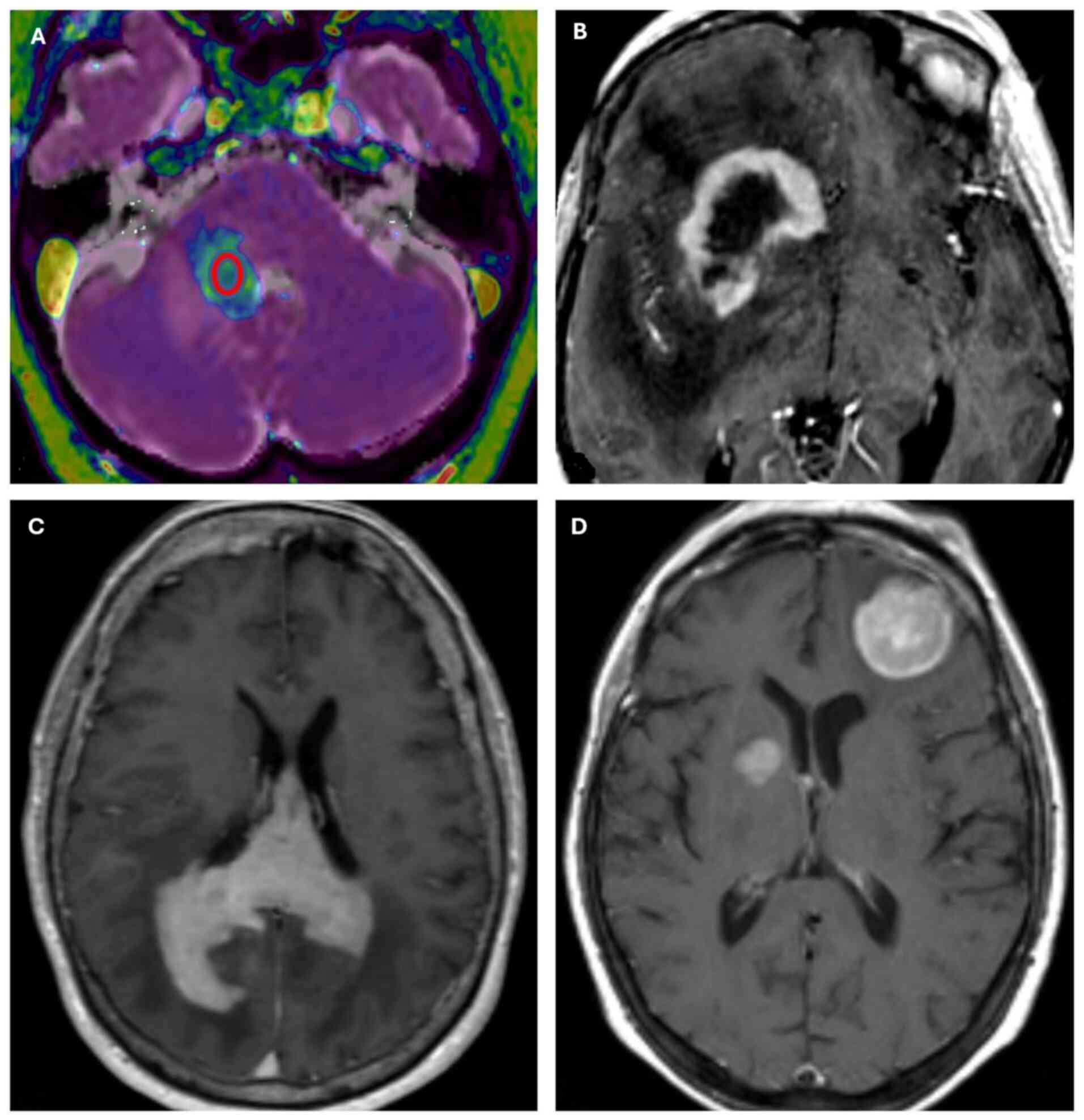

infratentorial disease in 5 cases (22%) (Table I). Regarding neuroradiological

features, MRI images showed homogeneous enhancement in 21 out of 23

cases and ring enhancement in 2 out of 23 patients, which can be

considered an expression of central tumor necrosis. Fourteen out of

18 supratentorial cases revealed invasion of the corpus callosum

and other median line structures, while infratentorial cases did

not exhibit this feature. Multifocal disease was indicated in 14

out of 23 cases and unifocal disease in 9 out of 23 cases (Fig. 4). The mean ADC value was

0.53×10−3 mm2/s, with a standard deviation of

0.18×10−3 mm2/s. The mean enhancement value

was 613.75, with a standard deviation of 264.66. Two subgroups were

identified based on age: those ≥60 included 4 GCB cases (20%) and

16 Non-GCB cases (80%), with a mean Ki-67 value >80%; the second

subgroup included 2 GCB cases and 1 Non-GCB case, with a mean Ki-67

value of 57%. The mean Ki-67 value was 82.5% in male patients and

71% in female patients.

| Table I.Clinical and pathological

characteristics of patients with primitive diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. |

Table I.

Clinical and pathological

characteristics of patients with primitive diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma.

| Characteristics | All patients

(n=23) | GCB | Non-GCB |

|---|

| Mean age, years

(range) | 65.7 (44–77) | 65.2 (57–75) | 65.9 (44–77) |

| Median age,

years | 66 | 65 | 66 |

| Age, n (%) |

|

|

|

| ≥60

years | 20 (87) | 4 (20) | 16 (80) |

| <60

years | 3 (13) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Male | 8 (35) | 2 (25) | 6 (75) |

|

Female | 15 (65) | 4 (27) | 11 (73) |

| Site of disease, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

Supratentorial | 18 (78) | 3 (17) | 15 (83) |

|

Infratentorial | 5 (22) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Number of lesions,

n (%) |

|

|

|

| 1 | 9 (39) | 1 (11) | 8 (89) |

| ≥2 | 14 (61) | 6 (43) | 8 (57) |

Statistical analysis

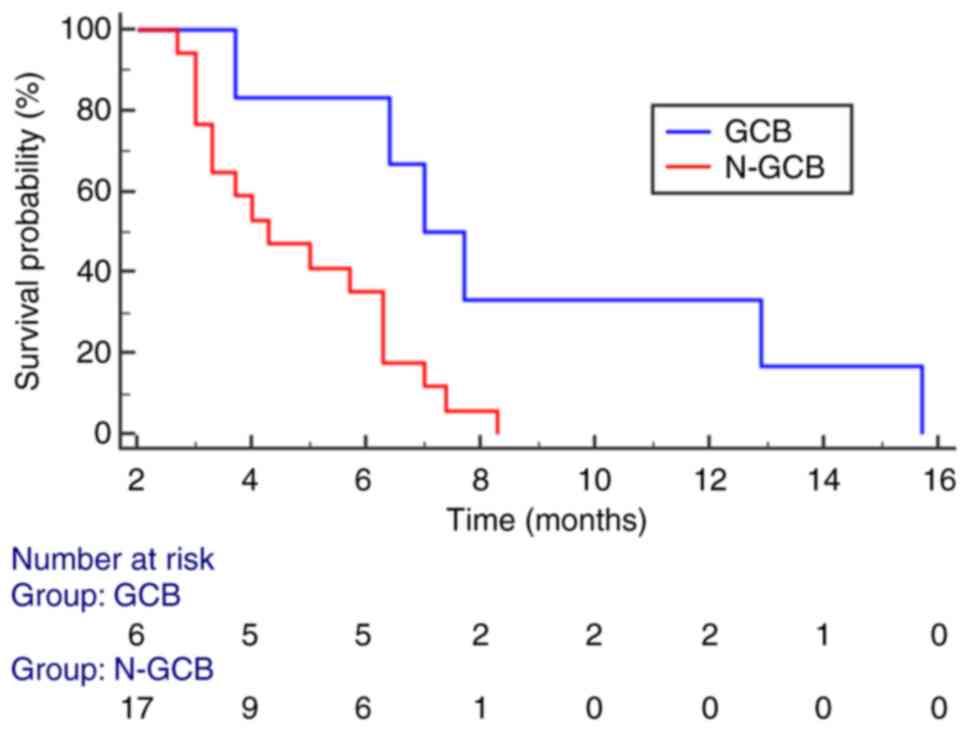

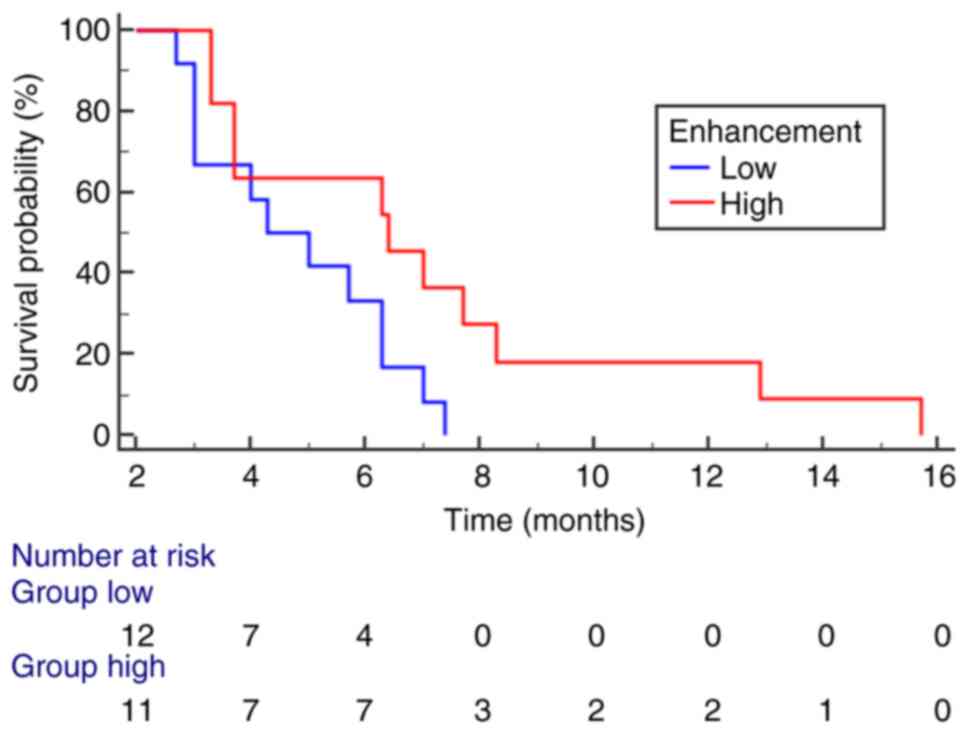

Univariate analysis revealed significant statistical

associations between the following variables: site of disease and

number of lesions (P=0.04), site of disease and immunohistochemical

(IHC) subtype (P=0.03), gender and ADC (P=0.02), and IHC subtype

and mean value of enhancement (P=0.008) (Table II, Table III, Table IV, Table V). In multivariate analysis, IHC

subtype (P=0.0158) (Fig. 5) and

mean value of enhancement (P=0.0391) (Fig. 6) emerged as independent variables;

comparing survival curves for GCB vs. Non-GCB and low vs. high

enhancement revealed significant differences in OS. Additionally, a

trend toward statistical significance was observed for c-Myc

(P=0.0648).

| Table II.Univariate analysis concerning site

and number of lesions in patients with primitive diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma. |

Table II.

Univariate analysis concerning site

and number of lesions in patients with primitive diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma.

|

|

| Number of

lesions |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Site of

disease | No. | Multifocal, n

(n=14) | Unifocal, n

(n=9) | P-value |

|---|

| Supratentorial | 18 | 13 | 5 | 0.04 |

| Infratentorial | 5 | 1 | 4 |

|

| Table III.Univariate analysis concerning site

and histological subtype in patients with primitive diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma. |

Table III.

Univariate analysis concerning site

and histological subtype in patients with primitive diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma.

|

|

| Subtype |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Site of

disease | No. | GCB, n (n=6) | Non-GCB, n

(n=17) | P-value |

|---|

| Supratentorial | 18 | 3 | 15 | 0.03 |

| Infratentorial | 5 | 3 | 2 |

|

| Table IV.Univariate analysis concerning sex

and ADC in patients with primitive diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. |

Table IV.

Univariate analysis concerning sex

and ADC in patients with primitive diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma.

|

|

| ADC |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Sex | No. |

>0.53×10−3

mm2/sec, n (n=12) |

<0.53×10−3

mm2/sec, n (n=11) | P-value |

|---|

| Male | 8 | 7 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Female | 15 | 5 | 10 |

|

| Table V.Univariate analysis concerning

histological subtype and MRI enhancement in patients with primitive

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. |

Table V.

Univariate analysis concerning

histological subtype and MRI enhancement in patients with primitive

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

|

|

| Mean value of

enhancement |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| IHC subtype | No. | >613.75, n

(n=8) | <613.75, n

(n=15) | P-value |

|---|

| GCB | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0.008 |

| Non-GCB | 17 | 3 | 14 |

|

Discussion

PCNSL is reportedly an uncommon extranodal lymphoma

with a poor prognosis (1,2). In the present study, we analyzed a

cohort of PCNSL-DLBCL patients, documenting a higher incidence in

those aged ≥60, consistent with existing literature (5). We also confirmed the highest

occurrence of the disease in supratentorial sites, as found

elsewhere too (13,14). Interestingly, our cohort showed a

higher number of affected female patients than males (13,15).

Notably, concerning the growth fraction in PCNSL-DLBCL, the mean

Ki-67 value appeared slightly reduced in the female subgroup

(Ki-67=71%) compared to male patients (Ki-67=82.5%). However, a

higher mean value (>80%) was observed in patients aged ≥60

compared to those <60 (Ki-67 mean value=57%), highlighting

higher proliferation rates in older patients (≥60), supporting the

potential prognostic significance of age, as indicated by the IELSG

main prognostic clinical score (16–18).

Additionally, high Ki-67 expression may predict poor prognosis in

PCNSL, as Ki-67 >90% has been associated with shorter OS

(15).

Our data regarding the prevalence of specific

PCNSL-DLBCL phenotypes revealed more Non-GCB cases, with the

majority expressing MUM1. Non-GCB cases represented the majority in

our cohort (17/23), while GCB cases were only 6/23, aligning with

literature data (13,15). Unfortunately, the Non-GCB subtype is

associated with a worse prognosis, as it carries additional

unfavorable prognostic factors, such as age ≥60 and mean Ki-67

value >80%; conversely, the GCB subtype is associated with a

better prognosis, influenced by younger age (<60) and reduced

Ki-67 value (57%). It is well established that Gadolinium-based

contrast agents leak from blood vessels into brain tissue due to

increased vascular permeability caused by tumor-induced breakdown

of the BBB (19). We therefore

hypothesize that the GCB subtype of PCNS-DLBCL may exhibit a

greater tendency to induce alterations in the capillary bed at the

lesion site, resulting in significant alterations in the BBB and

consequently, in a marked degree of contrast enhancement on MRI

examination. However, in the neuroradiological evaluation of PCNSL,

DWI and ADC maps are essential tools, as they provide crucial

information about tumor microstructure. Specifically, DWI sequences

measure the movement of water molecules in biological tissues,

enabling surrogate assessment of tissue characteristics in both

normal and pathological conditions (20). In highly cellular tumors, for

instance, the movement of water molecules is restricted; thus,

hypercellular tumors such as PCNSL typically exhibit low ADC values

(21). Further, PCNSL shows lower

ADC values than tumors such as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM),

metastases, demyelinating lesions, and infections (21). Although GBM may present solid areas

with restricted diffusion, it exhibits variable cellularity and may

show areas of necrosis or cysts, resulting in greater water

diffusion and higher ADC values. Consequently, ADC values in GBM

tend to be less homogeneous and higher than in PCNSL (21). Previous studies have indicated a

cut-off ADC value of 0.69×10−3 mm2/s

(21) that can help distinguish

lymphoma from glioblastoma with high sensitivity and specificity.

In our case series, all patients had brain lesions with low ADC

values (mean ADC value 0.53×10−3 mm2/s, with

a standard deviation of 0.18×10−3 mm2/s),

with no significant difference between GCB and Non-GCB groups.

Further, we were unable to identify a statistically significant

inverse correlation between lesional ADC values and cellular growth

fraction measured by Ki-67, confirming findings reported elsewhere

(22–24). ADC/cellularity correlation varies

across different tumor types: strong in neoplasms such as gliomas,

ovarian or lung cancer, moderate in epithelial neoplasms, and weak

in lymphomas (25). Therefore, the

low ADC values observed in lymphomas may be attributable not solely

to tumor hypercellularity but to other histopathological features,

such as reduced extracellular matrix, stroma/parenchyma ratio,

and/or microvessel density (25).

Univariate statistical analysis revealed a significant association

between the site of PCNSL-DLBCL and the number of lesions (P=0.04),

indicating that supratentorial localization is related to

multifocality and infratentorial disease to unifocal sites.

Additionally, a relationship between this parameter and the IHC

subtype emerged (P=0.03), with the supratentorial disease being

linked to the Non-GCB subtype and infratentorial disease with the

GCB subtype. Other notable correlations were documented,

particularly between the IHC subtype and the degree of contrast

enhancement (P=0.008), with the GCB subtype demonstrating

significantly increased contrast enhancement than the Non-GCB

group. Nevertheless, previous studies have attempted to examine the

prognostic role of key immunohistochemical markers such as CD10,

BCL-6, MUM-1, and BCL-2, along with clinical parameters (age,

gender, and the number of lesions), although discordant results

have emerged, possibly due to limited cohorts, differing methods of

immunohistochemical analysis, and different treatment (15,26).

Multivariate analysis and comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival

curves indicated that IHC subtype and contrast enhancement on MRI

examination were the most significant parameters influencing OS.

Specifically, GCB cases exhibited a better prognosis, with a longer

OS (16 months), while Non-GCB cases had a worse prognosis with a

shorter OS (8 months). Further, cases with higher MRI enhancement

values, corresponding to the GCB subtype, had longer survival than

cases with lower enhancement values, which aligned with the Non-GCB

subtype. Therefore, more adequate treatment adjustments should be

based on imaging too, suggesting different strategies regarding

immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T

cells; thus, immediate therapeutic applicability should be

hypothesized for more aggressive Non-GCB cases.

Finally, the association of morphological and

neuroradiological characteristics in PCNSL-DLBCL may provide a

significant prognostic tool to better define patients' OS,

advocating for a multidisciplinary approach in brain lymphoid

neoplasms. This desirable setting may prevent conflicting data

reported in the literature that exclusively refer to morphological

parameters such as immunophenotype and Ki67 value (15,27).

In conclusion, we assert that PCNSL is characterized by specific

clinicopathological and neuroradiological features (older age,

supratentorial site, Non-GCB immunoprofile, and MRI enhancement);

however, the limited sample size of the present cohort may

introduce bias into the investigation, necessitating further

multicentric studies to corroborate our results. Although the small

cohort analyzed and the single-center retrospective nature of the

study may influence statistics, introducing selection bias and

limiting generalizability, particularly for some subgroups (e.g.,

age/sex), the reduced interpretability of data may arise from

non-significant ADC-Ki67 correlation, rendering potential

confounders less prominent (e.g., tumor microenvironment

heterogeneity, cellular density).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

IR, CP, FG, AI and GT developed the study design and

drafted the manuscript. IR, CP, SCS, VF, MM and AG were involved in

data acquisition and interpretation. AI, FG and GT reviewed the

manuscript. AG, FG and GT confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to

participate

The analysis was conducted according to the Good

Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (1975,

revised in 2013). Before surgical procedures, all patients provided

written, anonymized and informed consent. Pathology reports and

medical records were thoroughly reviewed. Patient initials and

other personal identifiers were removed from all images. The

Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Messina

(Messina, Italy) approved the present study (approval no. N. 47/19;

May 2, 2019).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients for the publication of their data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu Y, Yao Q and Zhang F: Diagnosis,

prognosis and treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma

in the elderly population (Review). Int J Oncol. 58:371–387. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shao L, Xu C, Wu H, Jamal M, Pan S, Li S,

Chen F, Yu D, Liu K and Wei Y: Recent progress on primary central

nervous system lymphoma-From bench to bedside. Front Oncol.

11:6898432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ferreri AJM, Calimeri T, Cwynarski K,

Dietrich J, Grommes C, Hoang-Xuan K, Hu LS, Illerhaus G, Nayak L,

Ponzoni M and Batchelor TT: Primary central nervous system

lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 9:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

D'Angelo CR: Diagnostic, pathologic, and

therapeutic considerations for primary CNS lymphoma. JCO Oncol

Pract. 20:195–202. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Green K, Munakomi S and Hogg JP: Central

nervous system lymphoma. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island

(FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024

|

|

6

|

Schaff LR and Grommes C: Primary central

nervous system lymphoma. Blood. 140:971–979. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Koning ME, Hof JJ, Jansen C, Doorduijn

JK, Bromberg JEC and van der Meulen M: Primary central nervous

system lymphoma. J Neurol. 271:2906–2913. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lebrun L, Allard-Demoustiez S and Salmon

I: Pathology and new insights in central nervous system lymphomas.

Curr Opin Oncol. 35:347–356. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jin Q, Jiang H, Han Y, Zhang L, Li C,

Zhang Y, Chai Y, Zeng P, Yue L and Wu C: Tumor microenvironment in

primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). Cancer Biol Ther.

25:24251312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bödör C, Alpár D, Marosvári D, Galik B,

Rajnai H, Bátai B, Nagy Á, Kajtár B, Burján A, Deák B, et al:

Molecular subtypes and genomic profile of primary central nervous

system lymphoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 79:176–183. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hans CP: Confirmation of the molecular

classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by

immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 103:275–282.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Joshi A, Deshpande S and Bayaskar M:

Primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: Appearances on

conventional and advanced imaging with review of literature. J

Radiol Case Rep. 16:1–17. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Radotra BD, Parkhi M, Chatterjee D, Yadav

BS, Ballari NR, Prakash G and Gupta SK: Clinicopathological

features of primary central nervous system diffuse large B cell

lymphoma: Experience from a tertiary center in North India. Surg

Neurol Int. 11:4242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ribas GA, de Mori LH, Freddi TAL, Oliveira

LDS, de Souza SR and Corrêa DG: Primary central nervous system

lymphoma: Imaging features and differential diagnosis. Neuroradiol

J. 37:705–722. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Wang Y and Liu Y, Liu Z, Cui Q, Ji

N, Sun S, Wang B, Wang Y, Sun X and Liu Y: Immunohistochemical

profile and prognostic significance in primary central nervous

system lymphoma: Analysis of 89 cases. Oncol Lett. 14:5505–5512.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Puligundla CK, Bala S, Karnam AK, Gundeti

S, Paul TR, Uppin MS and Maddali LS: Clinicopathological features

and outcomes in primary central nervous system lymphoma: A 10-year

experience. Indian J Med Paediatric Oncol. 38:478–482. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Du KX, Shen HR, Pan BH, Luthuli S, Wang L,

Liang JH, Li Y, Yin H, Li JY, Wu JZ and Xu W: Prognostic value of

POD18 combined with improved IELSG in primary central nervous

system lymphoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 26:720–731. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yokogami K, Azuma M, Takeshima H and Hirai

T: Lymphomas of the central nervous system. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1405:527–543. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Provenzale JM, Mukundan S and Dewhirst M:

The role of blood-brain barrier permeability in brain tumor imaging

and therapeutics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 185:763–767. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

White NS, McDonald CR, Farid N, Kuperman

JM, Kesari S and Dale AM: Improved conspicuity and delineation of

high-grade primary and metastatic brain tumors using ‘restriction

spectrum imaging’: Quantitative comparison with high B-value DWI

and ADC. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 34:958–964. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ahn SJ, Shin HJ, Chang JH and Lee SK:

Differentiation between primary cerebral lymphoma and glioblastoma

using the apparent diffusion coefficient: Comparison of three

different ROI methods. PLoS One. 9:e1129482014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen J, Xia J, Zhou YC, Xia LM, Zhu WZ,

Zou ML, Feng DY and Wang CY: Correlation between magnetic resonance

diffusion-weighted imaging and cell density in astrocytoma.

Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 27:309–311. 2005.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Guo AC, Cummings TJ, Dash RC and

Provenzale JM: Lymphomas and high-grade astrocytomas: Comparison of

water diffusibility and histologic characteristics. Radiology.

224:177–183. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schob S, Meyer J, Gawlitza M,

Frydrychowicz C, Müller W, Preuss M, Bure L, Quäschling U, Hoffmann

KT and Surov A: Diffusion-weighted MRI reflects proliferative

activity in primary CNS lymphoma. PLoS One. 11:e01613862016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Surov A, Meyer HJ and Wienke A:

Correlation between apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and

cellularity is different in several tumors: A meta-analysis.

Oncotarget. 8:59492–59499. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Morales-Martinez A, Nichelli L,

Hernandez-Verdin I, Houillier C, Alentorn A and Hoang-Xuan K:

Prognostic factors in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr

Opin Oncol. 34:676–684. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Momota H, Narita Y, Maeshima AM, Miyakita

Y, Shinomiya A, Maruyama T, Muragaki Y and Shibui S: Prognostic

value of immunohistochemical profile and response to high-dose

methotrexate therapy in primary CNS lymphoma. J Neurooncol.

98:341–348. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|