Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an aggressive cancer

marked by the rapid growth of immature myeloid cells, which

disrupts normal blood cell production (1). Despite advancements in treatments such

as chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation (2), the lack of understanding of the tumor

microenvironment (TME) has hindered the effectiveness of

immunotherapies. The TME includes tumor cells, immune cells,

fibroblasts, blood vessels and cytokines, all interacting to

influence tumor progression. Immunotherapy aims to boost antitumor

responses whilst reducing immunosuppressive effects (3). In leukemia, the bone marrow is the

primary site for leukemia stem cells, with secondary lymphoid

organs also part of the TME. Current therapies such as checkpoint

inhibitors combined with chemotherapy and hypomethylating agents,

show promise. Further research into the immune microenvironment of

AML is essential to develop more effective immunotherapies

(4).

Unlike in solid tumors, the AML TME is primarily in

the bone marrow, with unique anatomical, cellular and metabolic

features. It includes hematopoietic stem/progenitor, stromal,

endothelial and immune regulatory cells, but lacks tumor-associated

fibroblasts and persistent antigenic stimulation typical of solid

tumors (5). The AML TME is highly

immunosuppressive, marked by increased regulatory T cells (Tregs),

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and exhausted T cells,

which limit immune responses (6).

Leukemia cells remodel the TME by altering C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand 12 (CXCL12) expression in stromal cells, suppressing normal

hematopoiesis and promoting their survival (7). The metabolic profile, hypoxia and

immune composition of AML differ from solid tumors, further

reducing immunotherapy efficacy (8). Recent studies have highlighted that

AML TME characteristics are associated with disease progression and

serve as a key factor for patient risk stratification (9,10).

Therefore, understanding AML-specific TME structure and function is

crucial for optimizing immunotherapy strategies.

Furthermore, T cells are crucial in antitumor

immunity, especially CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes

(CTLs), which kill tumor cells via granzyme B, perforin and

interferon-γ (IFN-γ), improving prognosis (6). Helper T cells (Th) 1, 2 and 17 also

serve roles: Th1 enhances CTL activity through IFN-γ and IL-2; Th2

recruits eosinophils and macrophages; and Th17 can have pro or

antitumor effects (11).

Conversely, Tregs suppress effector T cells (Teffs), often

associated with poor prognosis (12). In numerous cancers, Tregs are more

abundant in tumor tissues than in adjacent healthy tissues. Their

presence in the TME inhibits effector T cell function, promoting

disease progression and poor outcomes, as observed in colorectal

cancer (11).

Cells require nutrients for normal function, and

immune cells rely on nutrient uptake to regulate their activities

(13). T cell activation drives

metabolic shifts, boosting glycolysis to meet energy needs for

proliferation. Unlike cancer cells, which experience dysregulated

metabolism, T cells respond normally to these changes (14). Lipid and amino acid metabolism are

also crucial; lipid biosynthesis affects mTOR, a key regulator of

metabolic reprogramming (15),

whilst amino acid availability, particularly L-arginine, influences

T cell survival and adaptability (16). In the TME, tumor cells compete with

T cells for essential nutrients such as glucose, glutamine and

arginine, impairing T cell function and promoting tumor

progression. Through the Warburg effect, tumor cells outcompete T

cells for glucose, whilst programmed death-1 (PD-1) expression

further inhibits glycolysis. Fatty acid accumulation disrupts

mitochondrial function, driving T cell exhaustion. Tumor cells also

deplete arginine and glutamine, reducing their availability for T

cells. Other immune cells, such as dendritic cells, MDSCs and

tumor-associated macrophages, overexpress enzymes such as arginase

and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), depleting essential amino

acids and altering T cell activation and differentiation. The

accumulation of immunosuppressive Tregs further exacerbates T cell

exhaustion (17).

The AML TME is marked by high glucose metabolism and

lactic acid (LA) accumulation, creating an acidic environment that

suppresses T cell function (18).

Neutralizing acidity with sodium bicarbonate (NaBi) has been

reported to enhance CD8+ T cell immunotherapy efficacy

(19). The fms-related tyrosine

kinase 3-internal tandem duplication mutation increases glycolytic

activity, contributing to chemotherapy resistance and impaired T

cell function (20). Elevated

glucose metabolism in AML cells further drives chemoresistance.

Excessive glucose consumption and high LA levels in AML cells

inhibit T cell function, weakening antitumor immunity (21,22).

Lipid metabolism also serves a key role in tumor progression

(23), immune evasion and drug

resistance (24). Dysregulated

lipid metabolism alters the balance between Tregs and Teffs in the

TME (13).

Additionally, recent studies have highlighted the

critical role of T-cell metabolic reprogramming in the AML TME. The

abnormal metabolic features of the AML microenvironment, such as

high LA levels, hypoxia and nutrient competition, directly suppress

T cell effector functions and drive exhaustion by altering

metabolic pathways such as glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation

(FAO) (25–27). These factors notably contribute to

immunotherapy failure. The present review assesses the molecular

mechanisms of T cell metabolic reprogramming in the AML TME,

focusing on the way metabolic imbalances impair T cell

functionality. It also explores potential strategies for combining

metabolic interventions with immunotherapy. By synthesizing current

research, the current review aims to provide a theoretical

foundation for developing novel AML therapies based on metabolic

regulation.

Factors in the TME that influence T cell

metabolism in AML

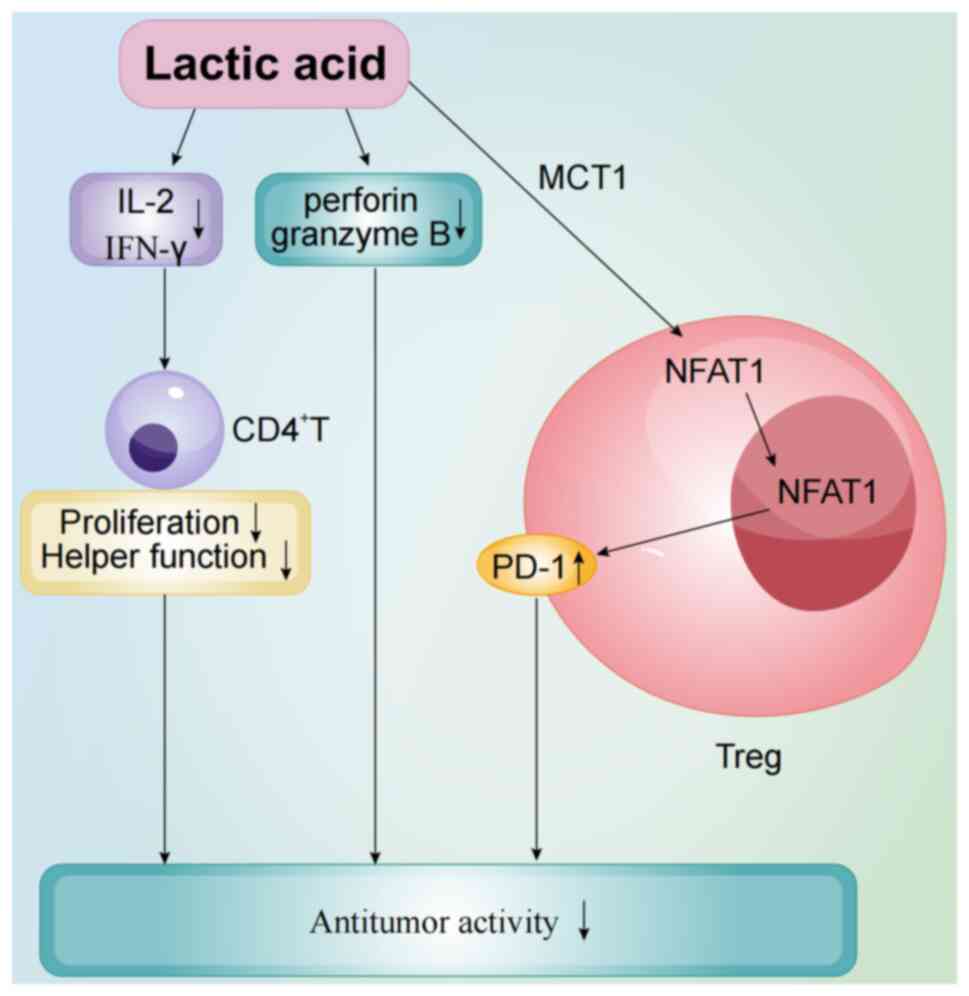

High levels of LA

A defining feature of the AML TME is the production

of excessive LA, creating a highly acidic environment (18). A study reported that LA inhibits T

cell growth and proliferation, and its accumulation in the TME

disrupts LA efflux from T cells, impairing their metabolism,

function and antitumor immunity (28). Additionally, LA downregulates

perforin and granzyme B, which are essential for T cell-mediated

tumor cell killing and proliferation (29,30).

Dichloroacetic acid (DCA) targets pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

(PDK), an enzyme that drives glucose metabolism toward glycolysis

instead of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in tumor cells. By

inhibiting PDK, DCA offers a potential strategy to modulate glucose

metabolism in the AML TME (31).

DCA can inhibit the shift toward glycolysis, reducing LA levels and

notably enhancing T cell proliferation, and cytokine production and

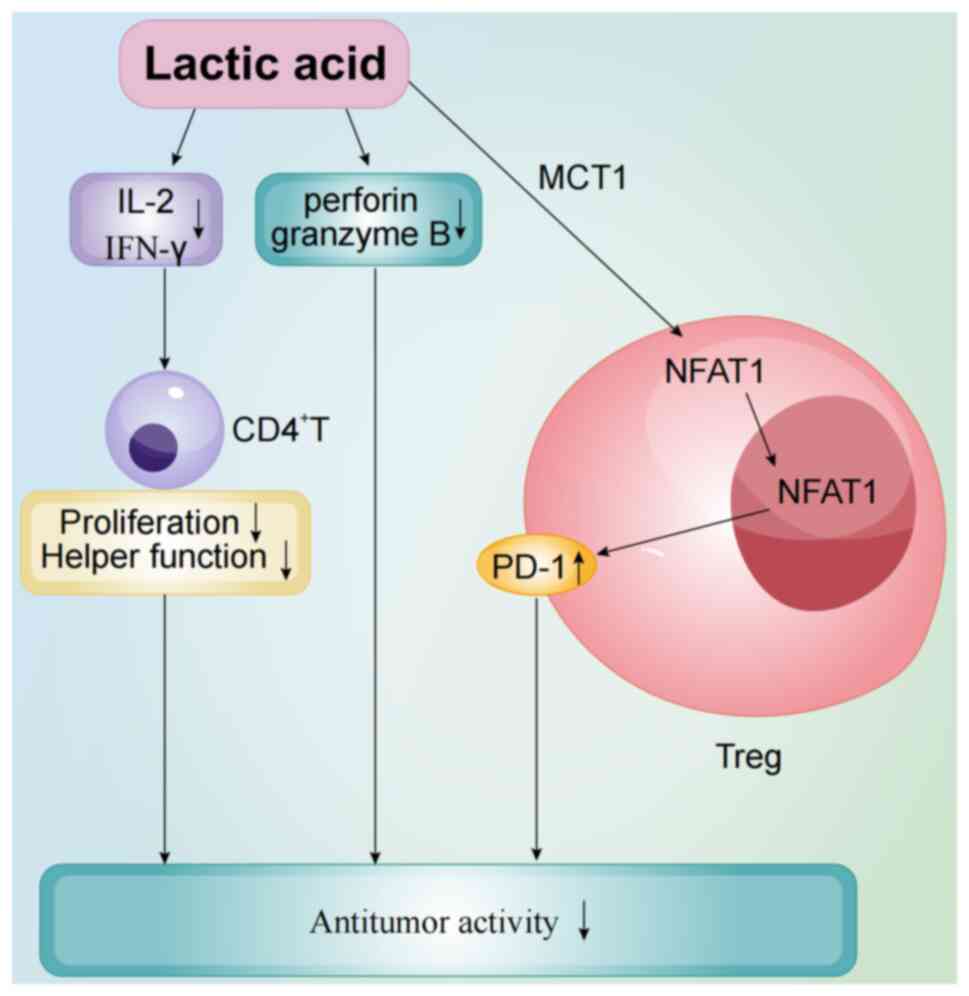

function whilst decreasing apoptosis (32). Tregs use monocarboxylate transporter

1 to uptake LA, which activates signaling pathways that promote

nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 translocation to the nucleus,

upregulating PD-1 expression (Fig.

1) (33). Therefore, high LA

levels increase PD-1 expression in Tregs, amplifying their

immunosuppressive effects. Additionally, LA accumulation and the

resulting acidic pH in the TME inhibit CD4+ T cell

activity, particularly the secretion of key cytokines such as IL-2

and IFN-γ. These cytokines are crucial for immune responses, and

their reduction weakens CD4+ T cell proliferation and

helper function, further promoting immunosuppression (34). In summary, high LA levels in the AML

TME are a major contributor to T cell dysfunction, impairing

antitumor immunity through metabolic disruption, cytotoxic

inhibition and induction of exhaustion.

| Figure 1.Acute myeloid leukemia tumor

microenvironment is characterized by high lactic acid levels, which

create an acidic milieu that impairs T cell function. Lactic acid

inhibits perforin and granzyme B, essential for T cell-mediated

tumor cell killing, and reduces the secretion of cytokines such as

IL-2 and IFN-γ, critical for CD4+ T cell proliferation.

Lactic acid accumulation in Tregs is facilitated by MCT1,

activating NFAT1 signaling and upregulating PD-1, enhancing

Treg-mediated immunosuppression. IFN-γ, interferon-γ; Treg,

regulatory T cell; MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter 1; NFAT1,

nuclear factor of activated T cells 1; PD-1, programmed

death-1. |

Hypoxia

Hypoxia is a defining feature of the bone marrow

TME, markedly impacting AML cell growth, metabolic reprogramming

and immune interactions. Studies have reported that patients with

higher hypoxia risk scores tend to have shorter overall survival

rates, linking hypoxia to poor prognosis in AML. Elevated hypoxia

risk scores are also strongly associated with disease progression

and the immunosuppressive TME (35,36).

Under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is

activated and directly upregulates programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) expression. High PD-L1 levels bind to PD-1 on T cells,

inhibiting their activation and signaling, further suppressing

antitumor immunity (37).

Nutrition competition

AML tumor cells and immune cells compete for

essential nutrients such as glucose and amino acids, which are

vital for both rapid tumor growth and normal immune function. Tumor

cells, with their high metabolic demands, prioritize the uptake of

glucose, glutamine and other substrates for energy and

biosynthesis, depriving immune cells of these resources. For

instance, AML cells depend on glutamine for OXPHOS, and the

inhibition of glutaminase-1 has been reported to suppress AML

development in mouse models (38).

Glutamine is also critical for T cell activation, proliferation and

cytokine production (39).

Glutamine deficiency in the TME promotes the generation of Tregs,

further exacerbating immunosuppression (40). Glutamine deficiency not only

restricts effector T cell proliferation and function, but also

supports the metabolic adaptation of Tregs, enhancing their

immunosuppressive activity. Studies have highlighted the antisense

non-coding RNA at the INK4 locus (ANRIL) as a key regulator of

glucose metabolism in AML, where it is notably upregulated. ANRIL

modulates glucose metabolism via the AMP-activated protein kinase

(AMPK)/ sirtuin 1 pathway, promoting AML cell survival. Its

knockdown reduces glucose uptake and inhibits AML cell maintenance

(41,42). Under oxygen-sufficient conditions,

AML cells rely heavily on glucose as their primary metabolic

substrate, rapidly converting it to LA through glycolysis to meet

energy demands (43). A study by

Cunningham and Kohno (44) using

18FDG labeling in 124 patients reported consistently high glucose

uptake in AML bone marrow, highlighting the glucose dependence of

AML cells. This excessive glucose consumption by AML cells

suppresses T cell activation, induces exhaustion and drives

leukemia progression.

Chemokines and cytokines

The AML TME shapes T cell metabolism and function by

secreting chemokines and cytokines, influencing tumor progression

(45,46). Studies have reported that chemokines

such as chemokine CCL3 and CXCL12 in the AML microenvironment

promote Treg accumulation, which competitively inhibits Teffs and

indirectly affects their metabolic activity (47,48).

Whilst research does not directly address whether chemokines

regulate T cell metabolic pathways, it highlights the potential of

blocking Treg migration to delay disease progression. Inhibiting

these chemokines has been reported to slow AML progression in mouse

models (45).

Accumulation of other metabolic waste

products

Potassium ions (K+), abundant in

intracellular fluid, are essential electrolytes that regulate

immune cell function and several cellular processes (49,50).

Tumor cell necrosis releases large amounts of K+ into

the extracellular fluid of the TME. Elevated extracellular

K+ concentrations impair T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated

Akt-mTOR phosphorylation, hindering effector T cell activation and

function (51). Conversely, higher

K+ levels can enhance T cell stemness, maintaining their

undifferentiated state (52). This

indicates that K+ dynamics in the TME influence both

immediate T cell effector functions and their long-term survival

and potential. However, research on the role of K+ in

the AML TME remains limited.

Changes in T cell metabolic pathways in the

AML microenvironment

Glycolysis and OXPHOS

Before antigen exposure, naive T cells remain in a

quiescent state maintained by IL-7. As they do not require clonal

expansion or high cytokine production, their reliance on anabolic

pathways for DNA, protein and molecule synthesis is minimal.

Instead, they generate ATP primarily through mitochondrial OXPHOS

(53). By contrast, tumor cells

undergo a notable metabolic shift, favoring glycolysis over OXPHOS

despite its lower ATP yield. This adaptation supports their rapid

proliferation and survival by quickly meeting energy and metabolic

intermediate demands (54). Tregs

derived from CD4+ T cells serve a dual role: They

maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmune diseases;

however, during AML progression, they suppress CTL activity,

weakening antitumor immunity and promoting immune evasion (55). Studies have reported that AML blasts

promote T cell differentiation into a Treg phenotype by expressing

inducible T cell co-stimulator ligand, markedly expanding the Treg

population (56,57). At the AML disease site, Tregs

suppress CTL activity, limiting their proliferation and hindering

the expansion of adoptively transferred CTLs in vivo. This

suppression weakens CTL-mediated antitumor effects, further

compromising immune responses against AML (58). Research indicates that mTOR and

glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) regulate CD4+ T cell

activation by influencing glycolysis. Increased glycolysis in

CD4+ T cells enhances their activation, proliferation

and survival whilst promoting effector T cell differentiation and

inhibiting Treg development, which suppresses immune responses

(59). Similarly, the

differentiation of CD8+ T cells from naive to effector

states requires upregulated glucose metabolism as glycolysis

provides the energy needed for their immune effector functions

(60). In mouse CD8+ T

cells, branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) accumulation boosts glucose

transporter 1 (GLUT1) levels via a forkhead box protein

O1-dependent mechanism, enhancing glycolysis and OXPHOS to

strengthen antitumor immunity. BCAA supplementation also improves

the efficacy of PD-1 immunotherapy in tumors (61). Thus, increased glycolysis serves a

crucial role in enhancing antitumor immune responses.

In AML, leukemia cells rely heavily on glycolysis

(Warburg effect) for energy, resulting in the accumulation of

glycolytic byproducts such as methylglyoxal. These reactive

compounds react non-enzymatically with proteins, lipids and DNA,

forming advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) (62). AGEs bind to the receptor for AGEs

(RAGE), activating signaling pathways such as NF-κB, MAPK and

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, which drive pro-inflammatory

and pro-survival responses, influencing cellular functions and

disease progression (63,64). AGE-RAGE signaling promotes the

proliferation of AML cell lines, such as HL60 and HEL, by

inhibiting apoptosis and autophagy, enhancing cancer cell survival

and invasiveness. This mechanism contributes to the progression of

several tumors, including AML (64). Consequently, the AGE-RAGE axis

represents both a hallmark of AML metabolic reprogramming and a

potential diagnostic and therapeutic target.

FAO

Fatty acid uptake and metabolism are essential for

AML cell proliferation, providing energy and metabolic

intermediates whilst inhibiting apoptosis and conferring resistance

to cytotoxic drugs. AML cells thus depend on fatty acid metabolism

for survival (65). Lipid

metabolism also serves a key role in T cell metabolic

reprogramming, supporting membrane expansion through the production

of phospholipids and cholesterol. Naive CD8+ T cells in

the lymphatic system primarily rely on FAO for energy (66). The differentiation of Teffs compared

with memory T cells depends on the strength of signals from

co-stimulatory molecules, cytokines and antigen presentation

(67). Strong stimulation leads to

the generation of short-lived terminally differentiated effector

cells, whilst weaker stimulation promotes the differentiation of

memory precursor cells, which further transform into long-lived

memory cells, providing protection against re-infection (68). Certain memory T cells also arise

from Teffs that survive apoptosis at the end of an immune response

(69). In the AML TME, memory T

cells exhibit markedly reduced metabolic adaptability and

persistence. Research indicates that these cells fail to sustain

critical metabolic pathways such as FAO and mitochondrial OXPHOS

resulting in energy deficiency that compromises their survival and

long-term effector function (6,70). AML

cells exacerbate this dysfunction by competing for essential

nutrients such as glucose and glutamine, further suppressing T cell

metabolism. Prolonged nutrient deprivation not only impairs memory

T cell function, but also promotes their exhaustion, characterized

by upregulated expression of exhaustion markers such as PD-1 and

thymocyte selection-associated high mobility group box protein, and

diminished cytotoxic capacity (56,71).

Notably, memory T cells also serve a role in modulating the

response of hematological malignancies to PD-1 blockade therapy

(72). Studies have reported that

TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) influences CD8+

memory T cells through lipid metabolism regulation. Mice with T

cell-specific TRAF6 deficiency exhibit strong effector T cell

responses but fail to form memory T cells effectively (73,74).

IL-15 regulates mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity and

oxidative metabolism by modulating mitochondrial biogenesis and the

key enzyme carnitine O-palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1)a. CPT1a is

critical for the rate-limiting step in mitochondrial FAO (75). Enhancing FAO through AMPK activation

or mTOR inhibition can notably increase memory T cell numbers

(73,76). These findings emphasize the pivotal

role of lipid metabolism in T cell metabolic reprogramming.

Amino acid metabolism

Studies have reported that amino acids regulate

immune responses by influencing T cell activation, cytokine

production and other immune functions (77). Glutamine, the most abundant amino

acid in serum, is vital for maintaining metabolic balance and cell

function. Its absence in culture medium markedly impairs naive T

cell activation, proliferation and cytokine production (39). In the hypoxic TME, glutamine acts as

a primary carbon source, supporting the energy and metabolic needs

of tumor cells (78). Amino acids

and their metabolites are essential in regulating both tumor and

immune cell proliferation within the TME. For instance, glutamine

and its metabolic pathways are crucial for tumor cell glycolysis.

Using glutamine antagonists can effectively inhibit glycolysis in

tumor cells, suppressing their growth and enhancing the antitumor

immune response by altering the immunosuppressive TME, thereby

overcoming immune evasion (79).

Besides glutamine, the metabolism of arginine and tryptophan also

serves a pivotal role in immune regulation within the TME. Studies

have reported that monocytes, under macrophage-stimulating factor

influence, rapidly degrade tryptophan through increased IDO

activity, thereby suppressing T cell proliferation. This mechanism

aids tumor cells and macrophages in immune evasion. Furthermore,

extracellular arginine availability in the TME directly influences

T cell function and antitumor responses (80,81).

Arginine deprivation leads T cells to initiate autophagy,

downregulate the CD3ζ chain and ultimately undergo apoptosis. In

AML, this effect is more pronounced, as AML blasts express and

secrete arginase II, a key enzyme for arginine metabolism, whilst

arginase I is typically low and only detectable under specific

conditions. This metabolic regulation further impairs T cell

function, aiding AML cells in evading immune surveillance (70). These findings highlight the crucial

association between amino acid metabolism in the TME and T

cell-mediated antitumor immunity.

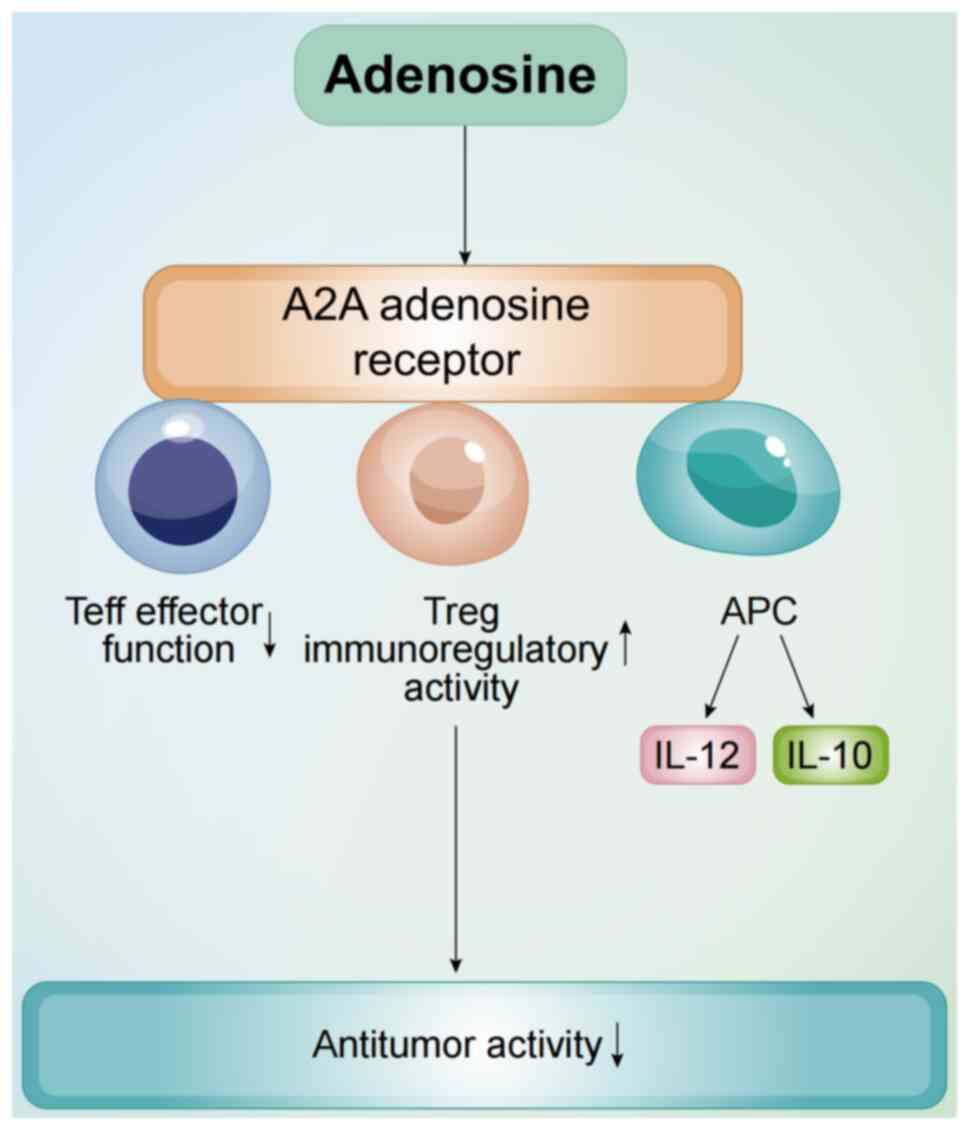

Nucleotide metabolism

Nucleotides, as essential components of genetic

material, are critical for highly proliferating cells, particularly

purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. Consequently, nucleotide

metabolism presents a potential target for cancer therapy (82,83).

Drugs such as methotrexate, which target nucleotide metabolism,

have been reported to be effective in treating acute lymphoblastic

leukemia (ALL). However, non-specific targeting of nucleotide

metabolism can inhibit normal cell processes, leading to severe

side effects (84,85). In the AML TME, high concentrations

of adenosine act as an immunosuppressive metabolite. Elevated

adenosine levels suppress T cell activity by inhibiting activation,

proliferation and cytokine secretion through adenosine receptor

binding such as A2A receptors (56). The A2A adenosine receptor signaling

pathway markedly inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation, activation

and cytokine production. Additionally, this pathway activates

immunosuppressive cells, such as Tregs and MDSCs, further impairing

effector immune cell function (86). Activation of A2A receptors not only

suppresses effector T cell activity, but also enhances Treg cell

immunoregulatory function by upregulating key molecules and

metabolic pathways, thus promoting immune suppression (Fig. 2) (87). Furthermore, studies have reported

that LA treatment reduces nucleotide abundance in T cells,

impairing proliferation and cell cycle activity. LA also disrupts

several metabolic pathways, including amino acid biosynthesis and

pyrimidine metabolism. NaBi itself can serve as a substrate for

multiple carboxylase reactions such as pyrimidine metabolism

(88,89). The application of NaBi can reverse

these changes, pyrimidine metabolism increased in T cells rescued

with NaBi (19).

Signaling pathways of T cell metabolic

remodeling in AML TME

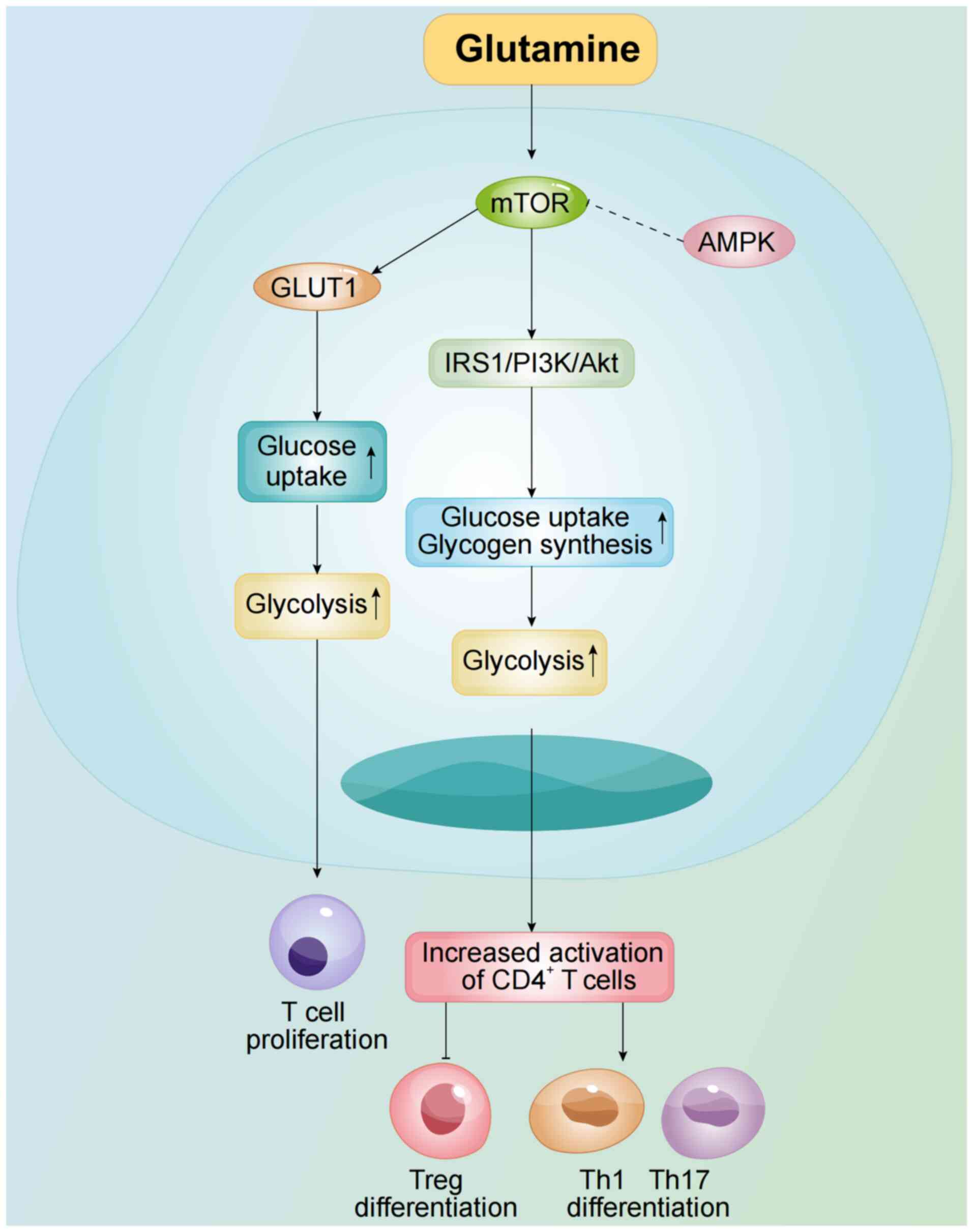

mTOR signaling pathway

mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase, serves a pivotal

role in several cellular processes, including metabolism

regulation. It is a key regulator of cell metabolism and serves as

the catalytic subunit of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes. mTORC1

supports effector T cell function by promoting glycolysis and

protein synthesis, whilst mTORC2 regulates T cell differentiation

and survival through the cytoskeleton and lipid metabolism

(90). mTOR enhances glucose uptake

and glycogen synthesis by modulating the insulin receptor substrate

1 (IRS1)/PI3K/Akt pathway, thereby boosting glycolysis. Inhibition

of mTOR activation or its downregulation in CD4+ T cells

reduce glycolysis, impairing their activation (31). mTOR activation also increases GLUT1

expression, promoting T cell proliferation and cytokine production

(Fig. 3) (91). Additionally, mTOR is a crucial

regulator of memory CD8+ T cell differentiation, with

the mTOR-specific inhibitor rapamycin, an immunosuppressive drug,

demonstrating an immunostimulatory effect on memory CD8+

T cells (87).

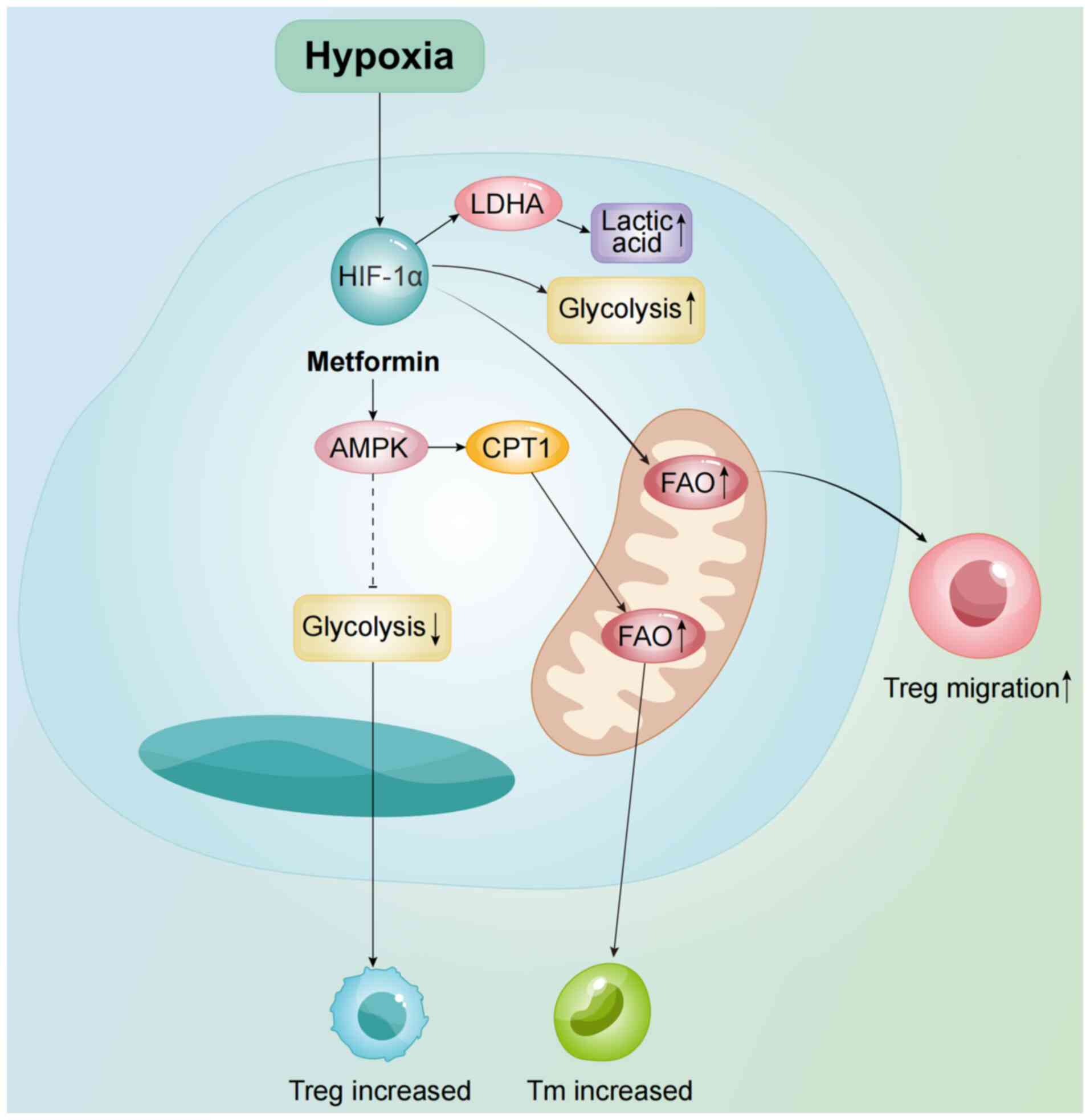

AMPK signaling pathway

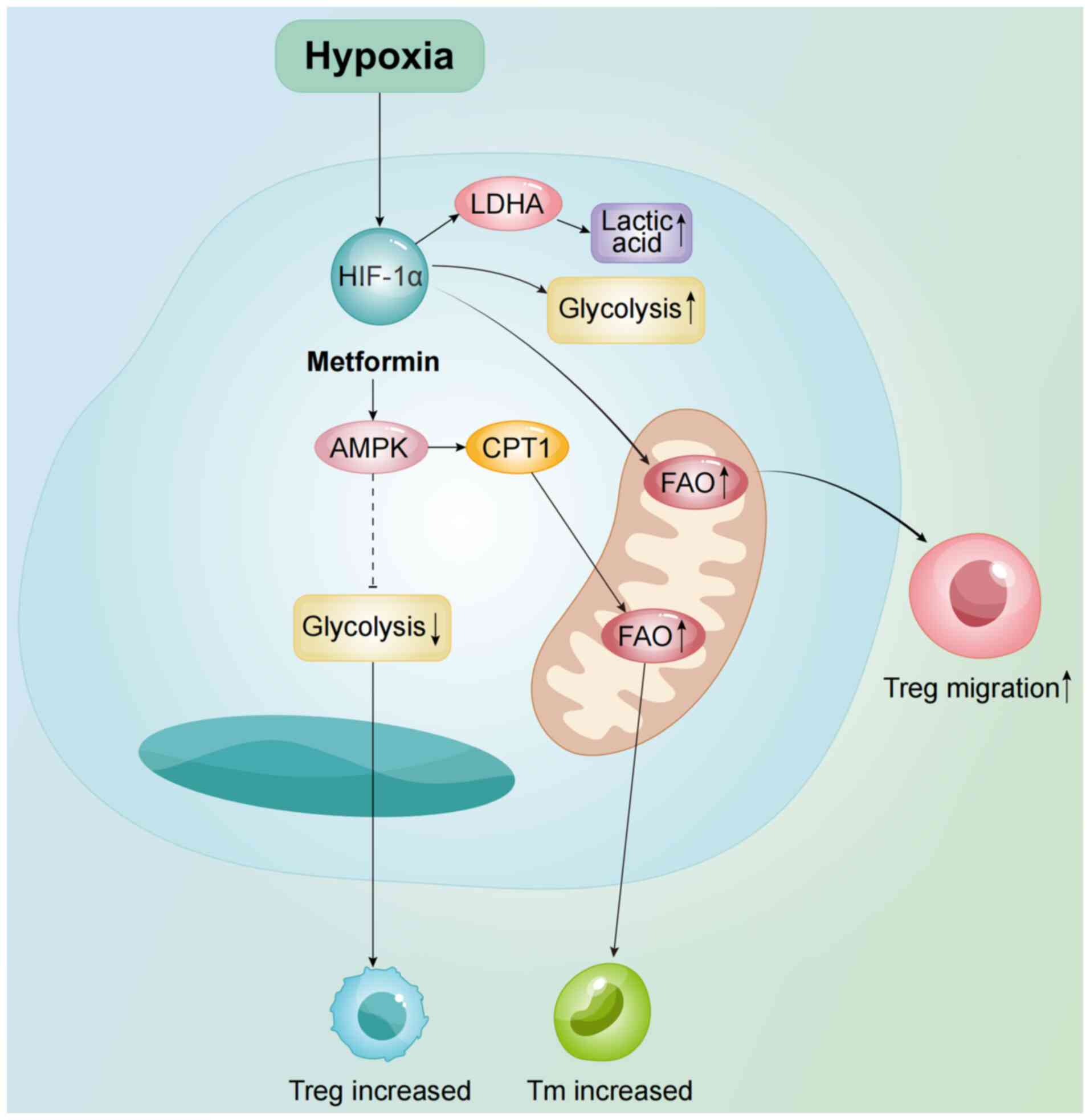

In the AML TME, AMPK, as a key energy sensor, serves

a crucial role in regulating the metabolic state of immune cells,

enabling them to effectively maintain their activity and function.

It also serves an important role in T cell metabolic reprogramming.

A previous study reported that AMPK signaling promotes lipid

metabolism to generate functional memory CD8+ T cells

(92). Furthermore, as an upstream

inhibitor of mTOR activity, AMPK can inhibit mTOR through the AMPK

activator metformin, which helps reduce glycolysis in T cells

(Fig. 4). This, in turn, promotes

the generation of Tregs by suppressing Th1 and Th17 cells (93). Metformin also activates AMPK and

inhibits the proliferation of AML cell lines and primary AML cells

(94). However, future research

needs to further explore the specific molecular mechanisms of AMPK

activation and its potential for clinical translation.

| Figure 4.As an mTOR inhibitor, AMPK suppresses

mTOR activity via metformin, reducing glycolysis and promoting Treg

generation whilst suppressing Th1/Th17 differentiation. AMPK also

upregulates CPT1, enhancing FAO and supporting T cell metabolic

reprogramming. Additionally, HIF-1α promotes Treg migration by

upregulating glycolysis and FAO. AMPK, AMP-activated protein

kinase; Th, Helper T cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; CPT1, carnitine

O-palmitoyl transferase 1; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α;

LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; Tm,

memory T cell. |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor (PPAR) family of transcription factors

The PPAR family includes PPARα, PPARδ and PPARγ. The

nuclear receptor PPARγ serves an essential role in adipogenesis,

immune responses and the metabolism of lipids and carbohydrates.

Fatty acids can also act as ligands for PPARγ (95,96).

Study have reported that in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),

high doses of glucocorticoids induce the activation of PPARα and

downstream FAO, leading to drug resistance (97). Moreover, it has been reported that

activation of PPAR promotes the proliferation of CD8+ T

cells, increasing the number of functional Teffs. The activation of

the PPAR pathway can also rescue PD-1 blockade-induced T cell

apoptosis by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl2,

baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3 and apoptosis inhibitor 5.

Additionally, PPAR activation can reprogram CTL energy metabolism

and overcome the reduction in the number of functional Teffs

associated with PD-1 blockade by reducing apoptosis or increasing

proliferation (98). Therefore,

targeting the PPAR signaling pathway, such as by using PPAR

agonists, may serve as a potential therapeutic target for AML.

HIF-1α and hypoxic response

HIF-1α is a central transcription factor in hypoxic

cells and a hallmark of TME. It is also a downstream target of

GLUT-1 (99). It facilitates Treg

migration by promoting glycolysis and FAO. Elevated glucose uptake

by cancer cells stabilizes HIF-1α, thereby suppressing antitumor

immunity (100,101). Moreover, HIF-1α-driven

transcription enhances glycolysis in T cells, supporting Th17

differentiation whilst inhibiting Tregs (91). Mitochondrial dysfunction and

HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming contribute to T cell

exhaustion, a process reversible through glycolysis inhibition

(102). Treatment with digoxin or

acriflavine, both inhibitors of HIF-1 expression and function, in

subcutaneous tumor mice has been reported to limit tumor growth

(103). Therefore, targeting HIF-1

in the TME may be an effective therapeutic strategy for AML.

Metabolic features of the AML

microenvironment and their impact on immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint (IC) inhibitors

ICs are molecular mechanisms that regulate immune

system activity, comprising co-stimulatory receptors such as CD40

and CD80 and inhibitory receptors such as cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 and PD-1. These checkpoints

maintain immune tolerance, protect normal tissues from excessive

immune responses, or, in certain cases, enable cancer cells to

evade immune surveillance (34).

The advent of IC inhibitors has improved the prognosis for numerous

solid tumors and certain lymphomas by blocking inhibitory signals

such as the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, thereby enhancing antitumor

immunity (104). However, their

efficacy in AML remains limited, particularly with PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors (105), for reasons

that are not yet fully understood. In the AML TME, competition for

nutrients between AML cells and T cells restricts T cell access to

glucose and glutamine, impairing their metabolic function and

antitumor response. Consequently, IC inhibitors fail to enhance T

cell-mediated antitumor effects (22). Furthermore, the PD-1/PD-L1

interaction serves a critical immunosuppressive role in the TME,

promoting regulatory T cell function and inhibiting the activation

and proliferation of Teffs, thereby further dampening the antitumor

immune response (106).

Limitations of adoptive T cell therapy

(ACT)

ACT enhances immune responses against tumors or

infections by modifying or expanding autologous or donor-derived T

cells ex vivo. This includes engineering T cells with

chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) or TCRs to recognize specific

tumor antigens. Following expansion, these Teffs are re-infused to

mediate targeted immune responses (107,108). However, unlike in ALL, CAR-T cell

therapy shows limited efficacy in AML, largely due to the

immunosuppressive TME (29).

Lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to CAR-T cell infusion can

enhance therapeutic outcomes by reducing Tregs in the TME and

alleviating their suppressive effects, thereby improving CAR-T cell

proliferation and persistence in vivo (109). In AML, expanded Tregs secrete

immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which impair

CAR-T cell function (57).

Additionally, AML cells secrete arginase II, disrupting T cell

metabolism and promoting immune evasion (41). Inhibition of arginine metabolism has

been reported to enhance the efficacy of CD33-CAR T cells in

preclinical AML models (110).

Similarly, blocking the adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR), a downstream

mediator of adenosine signaling, improves CAR-T cell efficacy in

solid tumors (111). Adenosine

suppresses T cell proliferation, activation and effector function

via A2AR, whilst promoting Treg expansion, thereby dampening

antitumor immunity (112).

However, whether this mechanism extends to hematologic malignancies

such as AML and CLL remains unclear.

Potential therapeutic strategies for

metabolic regulation

In patients with AML, elevated intracellular and

plasma arginase activity markedly inhibits T cell proliferation,

contributing to immune dysfunction. This effect is largely mediated

by increased expression and activity of arginase II in AML cells,

identifying it as a potential biomarker for immune status and

disease progression. Inhibition of arginase II has been reported to

restore T cell proliferation and enhance antitumor immunity

(110,113). When PD-1 binds to its ligand

PD-L1, activated T cells are unable to continue glycolysis and

normal amino acid metabolism, which results in insufficient energy

production to support their effector functions. In addition to

inhibiting glycolysis and amino acid metabolism, PD-1 may also

impair T cell oxidative detoxification capacity, reducing their

ability to cope with oxidative stress (114). Thus, elucidating the PD-1

signaling axis is crucial for understanding T cell dysfunction and

identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Future research directions and

challenges

Key areas for further exploration in T

cell metabolism in AML TME

Although the role of T cell metabolism in the AML

TME has been preliminarily elucidated, further in-depth exploration

is needed in the following key areas.

Metabolic reprogramming and

personalized therapy

In future research, individualized treatments

targeting T cell metabolic reprogramming in the TME of patients

with AML should focus on the impact of metabolic heterogeneity on

treatment responses. Differences in metabolic characteristics

between patients with AML may profoundly influence the metabolic

state of T cells and their antitumor capabilities. For example,

variations in glycolysis, FAO or amino acid metabolism across

different patients could lead to notable differences in therapeutic

efficacy. Utilizing metabolomics and single-cell analysis

techniques could uncover individual differences in T cell metabolic

reprogramming and provide a basis for precise metabolic

interventions. However, this approach faces several challenges,

such as the ways to integrate multidimensional data to accurately

identify key metabolic nodes, implement personalized metabolic

regulation of targets in clinical applications and minimize

potential side effects of metabolic interventions on systemic

metabolic homeostasis. In the future, combining advanced

technological methods and large-scale clinical studies will be

necessary to explore the feasibility of personalized metabolic

interventions, with the goal of achieving precision treatment for

patients with AML.

Application of emerging

technologies

In future research on T cell metabolic reprogramming

within the AML TME, emerging technologies will provide crucial

support for uncovering metabolic regulatory mechanisms and

therapeutic potential. The application of single-cell metabolomics

and spatial metabolomics can capture the dynamic changes and

spatial heterogeneity of T cell metabolism in the AML

microenvironment with high resolution, offering a new perspective

on the role of metabolic reprogramming in tumor immune evasion.

Moreover, metabolic flux analysis can track the dynamic changes in

key metabolic pathways within T cells in real-time, revealing the

flow and regulation patterns of metabolites under different

conditions. By contrast, CRISPR screening technology can precisely

identify key genes and metabolic nodes involved in T cell metabolic

reprogramming, providing specific targets for developing

intervention strategies. The combination of these technologies will

not only deepen the understanding of T cell metabolic regulation

mechanisms but also advance the design of personalized metabolic

treatment plans. However, the application of the aforementioned

technologies in AML still faces challenges, such as integrating

multidimensional data, high costs and unclear clinical translation

pathways. Future multi-disciplinary collaborations will be required

to further optimize their application.

Challenge of clinical translation

There are still notable obstacles and challenges in

translating the research on T cell metabolic reprogramming within

the AML TME into clinical application. A key obstacle from basic

research to clinical use is the way to simplify complex metabolic

mechanism studies into clear clinical targets, whilst ensuring

these targets have broad applicability across heterogeneous patient

populations. Moreover, although certain preliminary progress has

been made in clinical trials of metabolic interventions in AML,

such as improving the immune microenvironment through the

regulation of glycolysis, FAO or amino acid metabolism, issues such

as individual variability in efficacy, long-term treatment side

effects and resistance remain prominent. Metabolic interventions

may affect systemic metabolic homeostasis leading to unpredictable

toxic reactions, and the adaptive metabolic mechanisms of tumor

cells may induce resistance. Therefore, future research needs more

precise targeting strategies to achieve efficient regulation within

specific metabolic pathways, whilst minimizing systemic effects.

The combination of advanced technologies, such as metabolomics and

single-cell analysis for personalized treatment design, along with

the development of combination therapies to mitigate resistance,

may be key approaches to overcoming these challenges.

Conclusions

The present review explored the key mechanisms of T

cell metabolic reprogramming in the TME of AML and its notable

impact on antitumor immune responses. The AML microenvironment,

through the synergistic effects of high LA levels, hypoxia,

nutrient competition and chemokines, markedly suppresses critical

metabolic pathways in T cells, such as glycolysis, lipid metabolism

and amino acid metabolism, weakening their proliferation, effector

functions and antitumor capabilities. Additionally, the

accumulation of metabolic waste products from AML cells, as well as

abnormalities in adenosine and potassium ion metabolism, further

promotes the establishment of an immunosuppressive state.

Furthermore, although the mechanisms of T cell metabolic

reprogramming are preliminarily understood, designing personalized

treatment strategies based on the metabolic characteristics of

patients remains a major challenge. Emerging technologies, such as

single-cell metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis, provide new

research directions for uncovering metabolic mechanisms and

developing metabolic-targeted therapies. At the same time, future

clinical translation needs to balance efficacy with side effects,

optimizing metabolic intervention strategies to enhance the

effectiveness of immunotherapy.

In summary, in-depth research on T cell metabolic

reprogramming in the AML microenvironment will provide important

theoretical support for improving AML immunotherapy strategies,

whilst also offering new insights for the clinical application of

metabolic intervention therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XYZ designed and conceived the study. YHL wrote the

manuscript. JL and MY revised the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ and Bloomfield CD:

Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 373:1136–1152. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu H: Emerging agents and regimens for

AML. J Hematol Oncol. 14:492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Peng C, Xu Y, Wu J, Wu D, Zhou L and Xia

X: TME-related biomimetic strategies against cancer. Int J

Nanomedicine. 19:109–135. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bawek S, Gurusinghe S, Burwinkel M and

Przespolewski A: Updates in novel immunotherapeutic strategies for

relapsed/refractory AML. Front Oncol. 14:13749632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Menter T and Tzankov A: Tumor

microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia: Adjusting niches. Front

Immunol. 13:8111442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lamble AJ and Lind EF: Targeting the

immune microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia: A focus on T

cell immunity. Front Oncol. 8:2132018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Korn C and Méndez-Ferrer S: Myeloid

malignancies and the microenvironment. Blood. 129:811–822. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rieger CT and Fiegl M: Microenvironmental

oxygen partial pressure in acute myeloid leukemia: Is there really

a role for hypoxia? Exp Hematol. 44:578–582. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yu S and Jiang J: Immune

infiltration-related genes regulate the progression of AML by

invading the bone marrow microenvironment. Front Immunol.

15:14099452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zeng T, Cui L, Huang W, Liu Y, Si C, Qian

T, Deng C and Fu L: The establishment of a prognostic scoring model

based on the new tumor immune microenvironment classification in

acute myeloid leukemia. BMC Med. 19:1762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chraa D, Naim A, Olive D and Badou A: T

lymphocyte subsets in cancer immunity: Friends or foes. J Leukoc

Biol. 105:243–255. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Plitas G and Rudensky AY: Regulatory T

cells: Differentiation and function. Cancer Immunol Res. 4:721–725.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

MacIver NJ, Michalek RD and Rathmell JC:

Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol.

31:259–283. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lochner M, Berod L and Sparwasser T: Fatty

acid metabolism in the regulation of T cell function. Trends

Immunol. 36:81–91. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Endo Y, Kanno T and Nakajima T: Fatty acid

metabolism in T-cell function and differentiation. Int Immunol.

34:579–587. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C,

Feng Y, Fuhrer T, Kogadeeva M, Picotti P, Meissner F, Mann M, et

al: L-arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival

and anti-tumor activity. Cell. 167:829–842.e13. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang J, He Y, Hu F, Hu C, Sun Y, Yang K

and Yang S: Metabolic reprogramming of immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 25:122232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Halestrap AP: The monocarboxylate

transporter family-structure and functional characterization. IUBMB

Life. 64:1–9. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Uhl FM, Chen S, O'Sullivan D,

Edwards-Hicks J, Richter G, Haring E, Andrieux G, Halbach S,

Apostolova P, Büscher J, et al: Metabolic reprogramming of donor T

cells enhances graft-versus-leukemia effects in mice and humans.

Sci Transl Med. 12:eabb89692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ju HQ, Zhan G, Huang A, Sun Y, Wen S, Yang

J, Lu WH, Xu RH, Li J, Li Y, et al: ITD mutation in FLT3 tyrosine

kinase promotes Warburg effect and renders therapeutic sensitivity

to glycolytic inhibition. Leukemia. 31:2143–2150. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Herst PM, Howman RA, Neeson PJ, Berridge

MV and Ritchie DS: The level of glycolytic metabolism in acute

myeloid leukemia blasts at diagnosis is prognostic for clinical

outcome. J Leukoc Biol. 89:51–55. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Herst PM, Hesketh EL, Ritchie DS and

Berridge MV: Glycolytic metabolism confers resistance to combined

all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis in

HL60rho0 cells. Leuk Res. 32:327–333. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jones RG and Thompson CB: Tumor

suppressors and cell metabolism: A recipe for cancer growth. Genes

Dev. 23:537–548. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Röhrig F and Schulze A: The multifaceted

roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

16:732–749. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Heintzman DR, Fisher EL and Rathmell JC:

Microenvironmental influences on T cell immunity in cancer and

inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol. 19:316–326. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zha C, Yang X, Yang J, Zhang Y and Huang

R: Immunosuppressive microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia:

Overview, therapeutic targets and corresponding strategies. Ann

Hematol. 103:4883–4899. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Böttcher M, Baur R, Stoll A, Mackensen A

and Mougiakakos D: Linking immunoevasion and metabolic

reprogramming in B-cell-derived lymphomas. Front Oncol.

10:5947822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S,

Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G,

Hoves S, et al: Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid

on human T cells. Blood. 109:3812–3819. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen Y, Feng Z, Kuang X, Zhao P, Chen B,

Fang Q, Cheng W and Wang J: Increased lactate in AML blasts

upregulates TOX expression, leading to exhaustion of CD8+ cytolytic

T cells. Am J Cancer Res. 11:5726–6742. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Voskoboinik I, Whisstock JC and Trapani

JA: Perforin and granzymes: Function, dysfunction and human

pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 15:388–400. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sradhanjali S and Reddy MM: Inhibition of

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase as a therapeutic strategy against

cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 18:444–453. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rostamian H, Khakpoor-Koosheh M,

Jafarzadeh L, Masoumi E, Fallah-Mehrjardi K, Tavassolifar MJ, M

Pawelek J, Mirzaei HR and Hadjati J: Restricting tumor lactic acid

metabolism using dichloroacetate improves T cell functions. BMC

Cancer. 22:392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K,

Tanegashima T, Lin YT, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Irie T, Okumura G, Kono

H, et al: Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T

cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell.

40:201–218.e9. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang P, Sun Y, Zhang M, Hu L, Wang X, Luo

L, Qiao C, Wang J, Xiao H, Li X, et al: The inhibition of

CD4+ T cell proinflammatory response by lactic acid is

independent of monocarboxylate transporter 1. Scand J Immunol.

94:e131032021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jiang F, Mao Y, Lu B, Zhou G and Wang J: A

hypoxia risk signature for the tumor immune microenvironment

evaluation and prognosis prediction in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci

Rep. 11:146572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu X, Wang L, Kang Q, Feng C and Wang J:

A hypoxia-related genes prognostic risk model, and mechanisms of

hypoxia contributing to poor prognosis through immune

microenvironment and drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia.

Front Pharmacol. 15:13394652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Augustin RC, Delgoffe GM and Najjar YG:

Characteristics of the tumor microenvironment that influence immune

cell functions: Hypoxia, oxidative stress, metabolic alterations.

Cancers (Basel). 12:38022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jacque N, Ronchetti AM, Larrue C, Meunier

G, Birsen R, Willems L, Saland E, Decroocq J, Maciel TT, Lambert M,

et al: Targeting glutaminolysis has antileukemic activity in acute

myeloid leukemia and synergizes with BCL-2 inhibition. Blood.

126:1346–1356. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Carr EL, Kelman A, Wu GS, Gopaul R,

Senkevitch E, Aghvanyan A, Turay AM and Frauwirth KA: Glutamine

uptake and metabolism are coordinately regulated by ERK/MAPK during

T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol. 185:1037–1044. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Klysz D, Tai XG, Robert PA, Craveiro M,

Cretenet G, Oburoglu L, Mongellaz C, Floess S, Fritz V, Matias MI,

et al: Glutamine-dependent α-ketoglutarate production regulates the

balance between T helper 1 cell and regulatory T cell generation.

Sci Signal. 8:ra972015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sun LY, Li XJ, Sun YM, Huang W, Fang K,

Han C, Chen ZH, Luo XQ, Chen YQ and Wang WT: LncRNA ANRIL regulates

AML development through modulating the glucose metabolism pathway

of AdipoR1/AMPK/SIRT1. Mol Cancer. 17:1272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Balihodzic A, Barth DA, Prinz F and

Pichler M: Involvement of long non-coding RNAs in glucose

metabolism in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13:9772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pavlova NN, Zhu J and Thompson CB: The

hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab.

34:355–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Cunningham I and Kohno B: 18 FDG-PET/CT:

21st century approach to leukemic tumors in 124 cases. Am J

Hematol. 91:379–384. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang R, Feng W, Wang H, Wang L, Yang X,

Yang F, Zhang Y, Liu X, Zhang D, Ren Q, et al: Blocking migration

of regulatory T cells to leukemic hematopoietic microenvironment

delays disease progression in mouse leukemia model. Cancer Lett.

469:151–161. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bakker E, Qattan M, Mutti L, Demonacos C

and Krstic-Demonacos M: The role of microenvironment and immunity

in drug response in leukemia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1863:414–426.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang M, Yang Y, Liu J, Guo L, Guo Q and

Liu W: Bone marrow immune cells and drug resistance in acute

myeloid leukemia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 250:102352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ciciarello M, Corradi G, Forte D, Cavo M

and Curti A: Emerging bone marrow microenvironment-driven

mechanisms of drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia: Tangle or

chance? Cancers (Basel). 13:53192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Feske S, Colucci F and Coetzee WA: Do

KATP channels have a role in immunity? Front Immunol.

15:14849712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Feske S, Wulff H and Skolnik EY: Ion

channels in innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol.

33:291–353. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Eil R, Vodnala SK, Clever D, Klebanoff CA,

Sukumar M, Pan JH, Palmer DC, Gros A, Yamamoto TN, Patel SJ, et al:

Ionic immune suppression within the tumour microenvironment limits

T cell effector function. Nature. 537:539–543. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Vodnala SK, Eil R, Kishton RJ, Sukumar M,

Yamamoto TN, Ha NH, Lee PH, Shin M, Patel SJ, Yu Z, et al: T cell

stemness and dysfunction in tumors are triggered by a common

mechanism. Science. 363:eaau01352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Almeida L, Lochner M, Berod L and

Sparwasser T: Metabolic pathways in T cell activation and lineage

differentiation. Semin Immunol. 28:514–524. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Fukushi A, Kim HD, Chang YC and Kim CH:

Revisited metabolic control and reprogramming cancers by means of

the warburg effect in tumor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 23:100372022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Riether C: Regulation of hematopoietic and

leukemia stem cells by regulatory T cells. Front Immunol.

13:10493012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Epperly R, Gottschalk S and Velasquez MP:

A bump in the road: how the hostile AML microenvironment affects

CAR T cell therapy. Front Oncol. 10:2622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Han Y, Dong Y, Yang Q, Xu W, Jiang S, Yu

Z, Yu K and Zhang S: Acute myeloid leukemia cells express ICOS

ligand to promote the expansion of regulatory T cells. Front

Immunol. 9:22272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhou Q, Bucher C, Munger ME, Highfill SL,

Tolar J, Munn DH, Levine BL, Riddle M, June CH, Vallera DA, et al:

Depletion of endogenous tumor-associated regulatory T cells

improves the efficacy of adoptive cytotoxic T-cell immunotherapy in

murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 114:3793–3802. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu SY, Liao S, Liang L, Deng J and Zhou

Y: The relationship between CD4+ T cell glycolysis and

their functions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 34:345–360. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cao J, Liao S, Zeng F, Liao Q, Luo G and

Zhou Y: Effects of altered glycolysis levels on CD8+ T

cell activation and function. Cell Death Dis. 14:4072023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yao CC, Sun RM, Yang Y, Zhou HY, Meng ZW,

Chi R, Xia LL, Ji P, Chen YY, Zhang GQ, et al: Accumulation of

branched-chain amino acids reprograms glucose metabolism in

CD8+ T cells with enhanced effector function and

anti-tumor response. Cell Rep. 42:1121862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Rabbani N and Thornalley PJ:

Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino

Acids. 42:1133–1142. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Palanissami G and Paul SFD: AGEs and RAGE:

Metabolic and molecular signatures of the glycation-inflammation

axis in malignant or metastatic cancers. Explor Target Antitumor

Ther. 4:812–849. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Waghela BN, Vaidya FU, Ranjan K, Chhipa

AS, Tiwari BS and Pathak C: AGE-RAGE synergy influences programmed

cell death signaling to promote cancer. Mol Cell Biochem.

476:585–598. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bakhtiyari M, Liaghat M, Aziziyan F,

Shapourian H, Yahyazadeh S, Alipour M, Shahveh S,

Maleki-Sheikhabadi F, Halimi H, Forghaniesfidvajani R, et al: The

role of bone marrow microenvironment (BMM) cells in acute myeloid

leukemia (AML) progression: Immune checkpoints, metabolic

checkpoints, and signaling pathways. Cell Commun Signal.

21:2522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wang R, Liu Z, Fan Z and Zhan H: Lipid

metabolism reprogramming of CD8+ T cell and therapeutic

implications in cancer. Cancer Lett. 567:2162672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jameson SC and Masopust D: Understanding

subset diversity in T cell memory. Immunity. 48:214–226. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kaech SM and Cui W: Transcriptional

control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev

Immunol. 12:749–761. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

D'Cruz LM, Rubinstein MP and Goldrath AW:

Surviving the crash: Transitioning from effector to memory CD8+ T

cell. Semin Immunol. 21:92–98. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mougiakakos D: The induction of a

permissive environment to promote T cell immune evasion in acute

myeloid leukemia: The metabolic perspective. Front Oncol.

9:11662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Noviello M, Manfredi F, Ruggiero E, Perini

T, Oliveira G, Cortesi F, De Simone P, Toffalori C, Gambacorta V,

Greco R, et al: Bone marrow central memory and memory stem T-cell

exhaustion in AML patients relapsing after HSCT. Nat Commun.

10:10652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Abbas HA, Hao D, Tomczak K, Barrodia P, Im

JS, Reville PK, Alaniz Z, Wang W, Wang R, Wang F, et al: Single

cell T cell landscape and T cell receptor repertoire profiling of

AML in context of PD-1 blockade therapy. Nat Commun. 12:60712021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM,

Shen H, Wang LS, Jones RG and Choi Y: Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory

by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 460:103–107. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Raud B, McGuire PJ, Jones RG, Sparwasser T

and Berod L: Fatty acid metabolism in CD8+ T cell

memory: Challenging current concepts. Immunol Rev. 283:213–231.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

van der Windt GJW, Everts B, Chang CH,

Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E, Pearce EJ and Pearce EL:

Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+

T cell memory development. Immunity. 36:68–78. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa

S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP and Ahmed R: mTOR regulates

memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 460:108–112. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Li P, Yin YL, Li D, Woo Kim S and Wu G:

Amino acids and immune function. Br J Nutr. 98:237–252. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Wang Y, Bai C, Ruan Y, Liu M, Chu Q, Qiu

L, Yang C and Li B: Coordinative metabolism of glutamine carbon and

nitrogen in proliferating cancer cells under hypoxia. Nat Commun.

10:2012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Leone RD, Zhao L, Englert JM, Sun IM, Oh

MH, Sun IH, Arwood ML, Bettencourt IA, Patel CH, Wen J, et al:

Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome

tumor immune evasion. Science. 366:1013–1021. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT,

Bondarev I, Pashine A and Mellor AL: Inhibition of T cell

proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med.

189:1363–1372. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Murray PJ: Amino acid auxotrophy as a

system of immunological control nodes. Nat Immunol. 17:132–139.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Di Marcantonio D, Martinez E, Kanefsky JS,

Huhn JM, Gabbasov R, Gupta A, Krais JJ, Peri S, Tan Y, Skorski T,

et al: ATF3 coordinates serine and nucleotide metabolism to drive

cell cycle progression in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cell.

81:2752–2764.e6. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Yabushita T and Goyama S: Nucleic acid

metabolism: The key therapeutic target for myeloid tumors. Exp

Hematol. 142:1046932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Capelletti MM, Montini O, Ruini E,

Tettamanti S, Savino AM and Sarno J: Unlocking the heterogeneity in

acute leukaemia: Dissection of clonal architecture and metabolic

properties for clinical interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 26:452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Wu HL, Gong Y, Ji P, Xie YF, Jiang YZ and

Liu GY: Targeting nucleotide metabolism: A promising approach to

enhance cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 15:452022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wang H, Wei Y and Wang N: Purinergic

pathways and their clinical use in the treatment of acute myeloid

leukemia. Purinergic Signal. Mar 6–2024.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Ohta A: A metabolic immune checkpoint:

Adenosine in tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 7:1092016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Evans DR and Guy HI: Mammalian pyrimidine

biosynthesis: Fresh insights into an ancient pathway. J Biol Chem.

279:33035–33038. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Santi A, Caselli A, Paoli P, Corti D,

Camici G, Pieraccini G, Taddei ML, Serni S, Chiarugi P and Cirri P:

The effects of CA IX catalysis products within tumor

microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 11:812013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Pollizzi KN, Patel CH, Sun IH, Oh MH,

Waickman AT, Wen J, Delgoffe GM and Powell JD: mTORC1 and mTORC2

selectively regulate CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Clin

Invest. 125:2090–2108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Dabi YT, Andualem H, Degechisa ST and

Gizaw ST: Targeting metabolic reprogramming of T-cells for enhanced

anti-tumor response. Biologics. 16:35–45. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Saravia J, Raynor JL, Chapman NM, Lim SA

and Chi H: Signaling networks in immunometabolism. Cell Res.

30:328–342. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Yan Y, Huang L, Liu Y, Yi M, Chu Q, Jiao D

and Wu K: Metabolic profiles of regulatory T cells and their

adaptations to the tumor microenvironment: Implications for

antitumor immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Castro I, Sampaio-Marques B and Ludovico

P: Targeting metabolic reprogramming in acute myeloid leukemia.

Cells. 8:9672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, Liddle C,

Atkins AR, Downes M and Evans RM: PPARγ signaling and metabolism:

The good, the bad and the future. Nat Med. 19:557–566. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Angela M, Endo Y, Asou HK, Yamamoto T,

Tumes DJ, Tokuyama H, Yokote K and Nakayama T: Fatty acid metabolic

reprogramming via mTOR-mediated inductions of PPARγ directs early

activation of T cells. Nat Commun. 7:136832016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Tabe Y, Konopleva M and Andreeff M: Fatty

acid metabolism, bone marrow adipocytes, and AML. Front Oncol.

10:1552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chowdhury PS, Chamoto K, Kumar A and Honjo

T: PPAR-induced fatty acid oxidation in T cells increases the

number of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells and facilitates

anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 6:1375–1387. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zhang JZ, Behrooz A and Ismail-Beigi F:

Regulation of glucose transport by hypoxia. Am J Kidney Dis.

34:189–202. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Miska J, Lee-Chang C, Rashidi A, Muroski

ME, Chang AL, Lopez-Rosas A, Zhang P, Panek WK, Cordero A, Han Y,

et al: HIF-1α is a metabolic switch between glycolytic-driven

migration and oxidative phosphorylation-driven immunosuppression of

tregs in glioblastoma. Cell Rep. 27:226–237.e4. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Nagao A, Kobayashi M, Koyasu S, Chow CCT

and Harada H: HIF-1-dependent reprogramming of glucose metabolic

pathway of cancer cells and its therapeutic significance. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:2382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Wu H, Zhao X, Hochrein SM, Eckstein M,

Gubert GF, Knöpper K, Mansilla AM, Öner A, Doucet-Ladevèze R,

Schmitz W, et al: Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the transition

of precursor to terminally exhausted T cells through

HIF-1α-mediated glycolytic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 14:68582023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Pan F, Barbi J and Pardoll DM:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: A link between metabolism and T cell

differentiation and a potential therapeutic target. Oncoimmunology.

1:510–515. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Alatrash G, Daver N and Mittendorf EA:

Targeting immune checkpoints in hematologic malignancies. Pharmacol

Rev. 68:1014–1025. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Stahl M and Goldberg AD: Immune checkpoint

inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: Novel combinations and

therapeutic targets. Curr Oncol Rep. 21:372019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhou Q, Munger ME, Highfill SL, Tolar J,

Weigel BJ, Riddle M, Sharpe AH, Vallera DA, Azuma M, Levine BL, et

al: Program death-1 signaling and regulatory T cells collaborate to

resist the function of adoptively transferred cytotoxic T

lymphocytes in advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood.

116:2484–2493. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Sadelain M, Brentjens R and Rivière I: The

basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer

Discov. 3:388–398. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Riddell SR, Jensen MC and June CH:

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells: Clinical translation in

stem cell transplantation and beyond. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant.

19 (1 Suppl):S2–S5. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Suryadevara CM, Desai R, Farber SH, Choi

BD, Swartz AM, Shen SH, Gedeon PC, Snyder DJ, Herndon JE II, Healy

P, et al: Preventing Lck activation in CAR T cells confers treg

resistance but requires 4-1BB signaling for them to persist and

treat solid tumors in nonlymphodepleted hosts. Clin Cancer Res.

25:358–368. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Mussai F, Wheat R, Sarrou E, Booth S,

Stavrou V, Fultang L, Perry T, Kearns P, Cheng P, Keeshan K, et al:

Targeting the arginine metabolic brake enhances immunotherapy for

leukaemia. Int J Cancer. 145:2201–2208. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Beavis PA, Henderson MA, Giuffrida L,

Mills JK, Sek K, Cross RS, Davenport AJ, John LB, Mardiana S,

Slaney CY, et al: Targeting the adenosine 2A receptor enhances

chimeric antigen receptor T cell efficacy. J Clin Invest.

127:929–941. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Leone RD, Sun IM, Oh MH, Sun IH, Wen J,

Englert J and Powell JD: Inhibition of the adenosine A2a receptor

modulates expression of T cell coinhibitory receptors and improves

effector function for enhanced checkpoint blockade and ACT in

murine cancer models. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 67:1271–1284.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Mussai F, De Santo C, Abu-Dayyeh I, Booth

S, Quek L, McEwen-Smith RM, Qureshi A, Dazzi F, Vyas P and

Cerundolo V: Acute myeloid leukemia creates an arginase-dependent

immunosuppressive microenvironment. Blood. 122:749–758. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Patsoukis N, Bardhan K, Chatterjee P, Sari

D, Liu B, Bell LN, Karoly ED, Freeman GJ, Petkova V, Seth P, et al:

PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis

and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat Commun.

6:66922015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|