Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is primarily

divided into two major subtypes: Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and

lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). Among these, LUAD is the more

common form, representing 40–50% of NSCLC cases. The incidence of

LUAD has increased significantly, with prevalence rates reaching

39% in males and 57% in females in 2020, according to a global

population-based study (1),

particularly among non-smokers (2).

By contrast, LUSC, which is associated with smoking, accounts for

25–30% of NSCLC cases (3), and its

occurrence has decreased in line with lower smoking rates (4). For early-stage LUAD (stages I and II),

surgery remains the primary treatment modality, whereas patients

with EGFR mutations may benefit from targeted therapies (5). However, for more advanced stages (III

and IV), LUAD typically requires a combination of chemotherapy,

targeted therapy and immunotherapy (6,7).

Furthermore, the 5-year survival rate for patients with advanced

LUAD is generally <30%, with certain cases at <5% (8). This highlights the need for the

development of genetic signatures that can guide treatment

decisions and predict patient outcomes.

Mitochondrial genes associated with cuproptosis are

key factors in the progression of LUAD, making them potential

prognostic biomarkers (9).

Cuproptosis is a form of programmed cell death (PCD) induced by the

accumulation of copper ions (Cu2+), and there is an

increased demand for Cu2+ during tumor development and

metastasis (10). Excessive copper

accumulation leads to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and

damage to essential cellular components, ultimately resulting in

cell death. However, tumor cells require metal ions for metabolic

processes, and targeting metal ions presents notable potential for

future therapeutic research (11).

A total of three primary mechanisms underlie cuproptosis: i)

Oxidative stress, where copper ions catalyze the Fenton reaction,

generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage cell

membranes, proteins and DNA; ii) mitochondrial dysfunction, where

excess copper ions impair mitochondrial function, reduce ATP

production and release cytokines, triggering cell death; and iii)

lipid peroxidation, where copper ions induce lipid peroxidation,

disrupting the cell membrane and leading to cell death (12). Mitochondria and their associated

genes serve pivotal roles in cellular energy metabolism and

apoptosis, impacting tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion (13). Moreover,

mitochondria are crucial for LUAD progression, particularly under

hypoxic conditions where they support rapid tumor growth through

mitochondrial glycolysis, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect

(14). In LUAD cells, mitochondrial

dysfunction enhances resistance to oxidative stress and disrupts

mitochondrial membrane integrity, which in turn affects the balance

of Bcl-2 family proteins and facilitates evasion of apoptosis,

ultimately contributing to an uncontrolled cell cycle (15). Cuproptosis influences mitochondrial

membrane permeability and electron transport chain activity,

altering oxidative stress tolerance. Additionally, copper-induced

cell death leads to mitochondrial dysfunction by binding copper

ions to specific mitochondrial proteins, such as fatty acid

synthase and proteins involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle

(16). Therefore, both cuproptosis

and mitochondrial function serve central roles in the invasion,

metastasis and immune evasion of LUAD cells, markedly influencing

patient prognosis.

Despite the aforementioned findings, no studies to

date have explored the prognostic impact of cuproptosis-related

mitochondrial genes in LUAD, to the best of our knowledge.

Therefore, the present study aimed to identify such genes to

construct a prognostic model, and to further assess the prognostic

value of these genes in patients with LUAD by analyzing immune cell

infiltration, tumor gene mutations and drug sensitivity.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

LUAD sample data were obtained from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), which provides gene

expression profiles and clinical data for 489 patients with LUAD

and 59 adjacent normal tissue samples (17). To retrieve TCGA-LUAD dataset, the

official TCGA website was accessed and the data repository page was

entered by selecting the ‘Repository’ tab and clicking on ‘Explore

Our Cancer Datasets’. Using the ‘Cohort Builder’, the ‘Program’

field was expanded, and TCGA and LUAD were selected. Further

filtering was then performed by re-entering the ‘Repository’

section and selecting ‘RNA-Seq’, ‘STAR Counts’ and ‘Open access’

under the ‘Experimental Strategy’ filter. All relevant files were

subsequently added to the cart and downloaded using the ‘Download’

option. After acquisition, data cleaning and preprocessing were

performed, including gene symbol conversion. For duplicate genes,

the average expression value was calculated, and the data were

transformed from Fragments Per Kilobase of exon Model per Million

Mapped Fragments (FPKM) to transcripts per kilobase million

followed by log2 transformation. The final dataset

included gene expression profiles for >50,000 genes and

comprehensive clinical information for 489 patients with LUAD,

which included sex, age, survival time, survival status, clinical

stage and tumor (T)-node (N)-metastasis (M) stage. The GSE26939,

GSE31210 and GSE72094 datasets were also retrieved from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/geo), which provide gene

expression profiles and clinical survival data for 115, 226 and 398

patients, respectively. TCGA-LUAD dataset was used as the primary

training set, whilst the three GEO datasets were used for external

validation. The GSE26939, GSE31210, and GSE72094 datasets were

selected as they provide sufficient gene expression profiles and

comprehensive clinical information, especially survival time and

survival status: GSE26939 consists of gene expression data measured

using Agilent 44K microarrays and DNA copy number measurements

using Affymetrix 250K Sty and SNP6 microarrays from samples from

115 patients with LUAD (18);

GSE31210 involves the detection of EGFR, KRAS and ALK mutation

statuses in 226 patients with pathological stages I–II (19); and GSE72094 provides expression

sequencing of mutation-associated genes from tumor samples of 398

patients with LUAD, as well as data for tumor proliferation and

immune surveillance (20). Data

processing and visualization were performed using R software

(version 4.3.2; The R Foundation).

Acquisition of cuproptosis-related

mitochondrial and differential gene analysis

Based on previous studies, 13 cuproptosis-related

genes and 1,136 mitochondrial-related genes were identified

(21,22). Pearson correlation analysis was

performed using the ‘limma’ R package (version 3.54.1), which is

available from bioconductor.org/packages/limma (23,24).

To explore more potential cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes,

genes with a correlation (cor) of >0.3 were selected as

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes (cor >0.3 was considered

to be strongly correlated) (25,26).

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered based on the

criteria of |logFoldChange|≥1 and P<0.05. A Venn diagram was

created using the online tool jvenn (version 1.2.0,

jvenn.toulouse.inrae.fr/app/index.html) to show the overlap between

DEGs and mitochondrial genes in TCGA dataset.

Machine learning and risk score model

construction

A univariate Cox analysis was performed, and the

results were visualized using a forest plot. TCGA, GSE26939,

GSE31210 and GSE72094 datasets were combined for machine learning

analysis. A total of 10 machine learning algorithms and 117

algorithm combinations were used, and the best algorithm

combination was determined based on 10-fold cross-validation. The

best model was selected based on the highest average C-index value.

The 10 machine learning algorithms included the following: Least

Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) (26), Random Survival Forest (RSF)

(27), StepCox (28), Elastic Net (Enet) (29), Ridge (30), Generalized Boosted Regression

Modeling (GBM) (31), CoxBoost

(32), Cox Partial Least Squares

Regression (plsRcox) (33),

Supervised Principal Components (SuperPC) (34) and survival-Support Vector Machine

(survival-SVM) (35). Finally, a

risk score model was constructed using the LASSO + survival-SVM

algorithm based on the C-index value, and the optimal cutoff point

was determined (22). The machine

learning algorithms used are listed in Table I. A total of 22 prognostic genes

were identified. The λ.min value was used as the penalty parameter

for the LASSO machine learning model as λ.min ensures that more

prognostic genes are retained without compromising predictive

performance, allowing the exploration of the roles of more relevant

prognostic genes in LUAD prognosis and treatment (36). The code for the 117 machine learning

methods is provided in Data S1. The risk score was calculated by

applying the standardized expression values of the identified genes

and their respective coefficients, with the following formula: Risk

score=∑ (Coef × Expr), where Coef is the coefficient and Expr is

the FPKM for each gene. The code used to calculate the risk

coefficients is provided in Data S2. Survival analysis was

performed using the ‘survival’ R package (version 3.8–3,

CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival) (37), the ‘survminer’ package (version

0.5.0, available at http://CRAN.R–project.org/package=survminer)

(38), and the ‘ggplot2’ package

(version 3.5.2, available at http://CRAN.R–project.org/package=ggplot2)

(39). Kaplan-Meier analysis was

performed based on risk grouping to evaluate patient prognosis.

Patients were categorized into high- and low-risk groups based on

the median risk score.

| Table I.Types of machine learning. |

Table I.

Types of machine learning.

| Algorithm | R package | (Refs.) |

|---|

| LASSO | glmnet | (26) |

| RSF |

RandomForestSRC | (27) |

| StepCox | survival | (28) |

| Enet | glmnet | (29) |

| Ridge | glmnet | (30) |

| GBM | gbm | (31) |

| CoxBoost | CoxBoost | (32) |

| plsRcox | plsRcox | (33) |

| SuperPC | superpc | (34) |

| survival-SVM | survivalsvm | (35) |

Nomogram construction based on risk

score model

A forest plot was used to present the impact of each

variable on the model, including P-values, hazard ratios (HRs) and

95% confidence intervals (CIs). A nomogram was constructed using

both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of

clinical features and risk scores, using the ‘rms’ R package

(version 6.7-0, CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms) (40). Calibration curves were used to

assess the clinical applicability of the model. Receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to evaluate the

predictive accuracy of the model (22).

Tumor microenvironment (TME) and tumor

mutational burden (TMB) estimation based on risk score

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA)

normalized the gene expression profile within each sample and then

calculated the ssGSEA score for each gene set. ssGSEA analysis of

the gene expression profile from TCGA-LUAD dataset was performed to

quantitatively analyze the levels of immune cells and

immune-related pathways. The ssGSEA analysis code is provided in

Data S3. In this way, ssGSEA transforms the gene expression profile

of an individual sample into a gene set enrichment score matrix.

The gene sets used for immune infiltration analysis mainly came

from previously published studies and were downloaded from the

supplementary file of He et al (25). Additionally, these gene sets were

obtained by searching for the target pathway genes in the ‘Quick

Search’ section on the homepage of the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php). These gene

sets are provided in Table SI. The

expression of interleukin (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) gene

families were compared between the high- and low-risk groups

(26). Additionally, a correlation

heatmap analysis of 22 model genes with immune cells and pathways

was generated. Moreover, the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion

(TIDE) analysis was performed using the TIDE web platform (version

1.0, tide.dfci.harvard.edu) to predict the response of patients

with LUAD to immune checkpoint therapy by calculating immune

dysfunction, with a higher TIDE score indicating greater resistance

to immunotherapy (41). The

ESTIMATE algorithm (available at:

bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/estimate/) and the ‘estimate’ R

package (version 1.0.13) were used to evaluate stromal, immune, and

estimate scores to infer TME in each LUAD patient (42). The CIBERSORT algorithm (http://cibersort.stanford.edu/) and the ‘xCell’ R

package (version 1.1.0, xcell.ucsf.edu/) were used to analyze

immune cell infiltration and estimate the expression of 67 immune

cell subtypes in each patient (43,44).

In addition, tumor mutational burden (TMB), an important biomarker

for predicting tumor immune response, was calculated using the

‘maftools’ R package (version 2.24.0, available at http://bioconductor.org/packages/maftools) (36,45).

Drug sensitivity analysis

(IC50)

The association between prognostic genes and 198

drugs was assessed. Drugs were selected for analysis based on their

correlation with risk scores and prognostic genes, and a heatmap

was created. Drug sensitivity was assessed using the ‘oncoPredict’

R package (version 1.2, available at http://github.com/HuangLabUMN/oncoPredict) (46), whilst the ‘ggpubr’ package (version

0.6.1, rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/) was used for correlation

analysis (47). Subsequently, the

‘pheatmap’ (version 1.0.13, available at http://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap) and ‘psych’

(version 2.5.6, available at personality-project.org/r/psych/)

packages were used to generate heatmaps (48,49).

Cell culture

A549 and PC9 human lung cancer cell lines, were

purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences

(Shanghai, China). The catalog numbers are as follows: A549 (Cat.

No. TCHu150) and PC9 (Cat. No. TCHu142). The cells were cultured in

RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS (NEWZERUM; FBS-UE500, Uruguay) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin solution. They were maintained in a

humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2, and the

culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days. When cells reached 90%

confluence, they were digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution for

subsequent experiments.

Small interfering (si)RNA

transfection

siRNA was used to knockdown gene expression, with a

negative control (siNC). Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) siRNA and

siNC were purchased from IBSBIO. The sequences used were as

follows: si-SOD2, 5′-GGUUCCUUUGACAAGUUUAAG-3′ and si-NC,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. According to the manufacturer's

instructions, si-SOD2 was transfected into A549 and PC9 cells using

Lipofectamine™ 3000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen™; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Transfection was performed using 50 nM

siRNA/well. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator

with 5% CO2 for 6 h, after which the transfection medium

was replaced with fresh complete medium.

Subsequent experiments, including RT-qPCR, Western

blotting, and migration/proliferation assays, were carried out 24

to 48 h post-transfection. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that SOD2

expression was significantly reduced after siRNA transfection in

both A549 and PC9 cells.

RT-qPCR

After transfection, A549 and PC9 cell lines were

digested with trypsin according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and its concentration was measured using

a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA

was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using the

PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

following the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using the

SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) to assess the

expression of the SOD2 gene. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. β-actin was used as

the internal control, and relative mRNA expression was calculated

using the 2−ΔΔCq method (50). The primer sequences used were as

follows: β-actin (forward), 5′-ATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAACGTAC-3′ and

(reverse), 5′-CACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCGTGTG-3′; and SOD2 (forward),

5′-GCTCCGGTTTTGGGGTATCTG-3′ and (reverse),

5′-GCGTTGATGTGAGGTTCCAG-3′.

Cell proliferation assay

For the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (51), A549 and PC9 cell lines were

transfected with siRNA for 48–72 h. Subsequently, 5,000 cells/well

were seeded into 96-well plates. Cells were incubated at 37°C with

5% CO2, and CCK-8 solution (80 µl complete medium and 20

µl CCK-8 reagent; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was

added at 2, 24, 48 and 72 h after incubation. After 2 h of

incubation, absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Each sample was

analyzed in triplicate.

Transwell migration and invasion

assays

For the Transwell migration and invasion assays,

A549 and PC9 cells were cultured in 6-well plates and transfected

with siRNA for 24 h. Migration was assessed using 24-well Transwell

chambers (BD Biosciences). A total of 5×104 cells were

seeded into the upper chamber containing 150 µl serum-free medium,

whilst the lower chamber contained 500 µl medium supplemented with

20% FBS. For the invasion assay, Matrigel was thawed from −20°C to

liquid state at 4°C and diluted at a ratio of 1:8 with serum-free

medium. Subsequently, 50 µl diluted Matrigel was added to the upper

chamber and incubated at 37°C for 3 h to allow gelation before

seeding the cells, to evaluate cell invasion. Following 24 h of

incubation, the cells that had migrated or invaded to the lower

surface of the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30

min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min, both at room

temperature. Images were captured under a light microscope (Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for analysis.

Colony formation assay

A total of 500 A549 or PC9 cells 500 cells were

seeded into 6-well plates and incubated at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 10 days (52). Once visible colonies (≥50 cells)

formed, the cells were washed with PBS, stained with 0.1% crystal

violet for 20 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Images

of the cells were then captured by light microscope(Olympus,

Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Colony counts were analyzed

using GraphPad software (version 9.5.1; Dotmatics).

Mitochondrial immunofluorescence

assay

The A549 and PC9 cell lines were cultured on sterile

coverslips in 6-well plates and treated with siNC and si-SOD2. When

the cells reached 60% confluence, they were stained with

MitoTracker Deep Red mitochondrial probe (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at 37°C. After staining, the cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature,

followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100. The coverslips

were then mounted with a fluorescence quenching mounting medium

containing DAPI (1.5 µg/ml). Fluorescence imaging was performed

using a laser confocal microscope to compare the mitochondrial

density after treatment with siNC and si-SOD2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed ≥3 times. For

comparisons between two groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or

unpaired t-test was used. All data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD) with n=3. Pearson correlation analysis was

performed to assess related genes, and univariate and multivariate

Cox analyses were performed to identify prognostic-related genes.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1). All

analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.5 (The R

Foundation). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

signification difference.

Results

Screening and identification of

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes

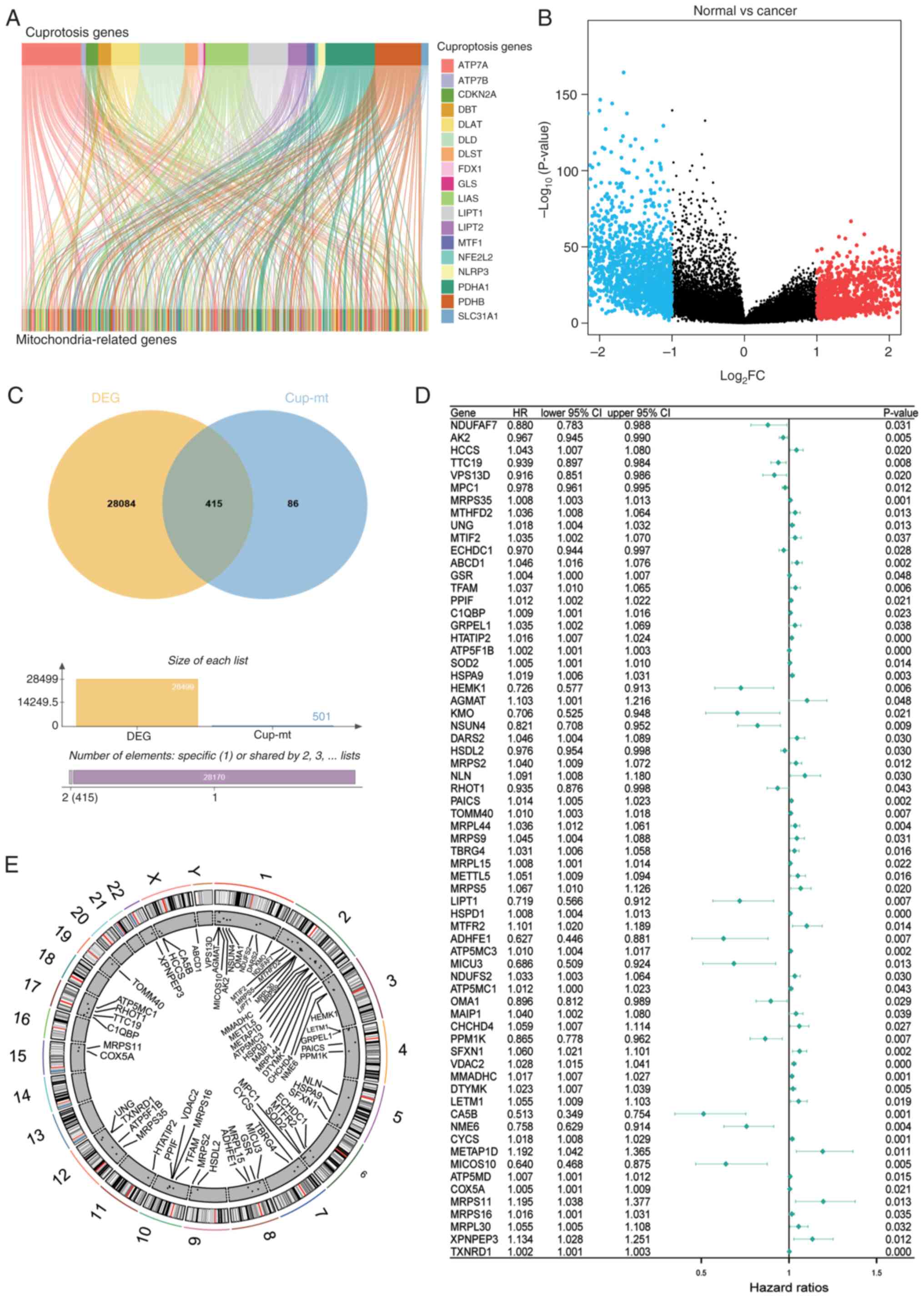

A total of 501 cuproptosis-related mitochondrial

genes were identified using Pearson correlation analysis (cor

>0.3; Fig. 1A). In the screening

of cuproptosis and mitochondria-related genes, Pearson's linear

correlation analysis was used. A general threshold of 0.5 was set

as a strong correlation. However, the 1-, 3- and 5-year ROC values

of the prognostic genes selected from this analysis were 0.653,

0.639 and 0.602, respectively, all of which were <0.7 (Fig. S1). Moreover, the correlation

between genes is not necessarily linear and could involve indirect

regulation. Therefore, to include more potential genes, a threshold

of 0.3 was set according to the study by Jiang et al

(26).

Differential gene expression analysis using TCGA

dataset revealed 415 cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes

(Fig. 1B and C). Moreover,

univariate Cox regression analysis identified 67 prognostic-related

genes (Fig. 1D), with their

chromosomal distribution mapped (Fig.

1E).

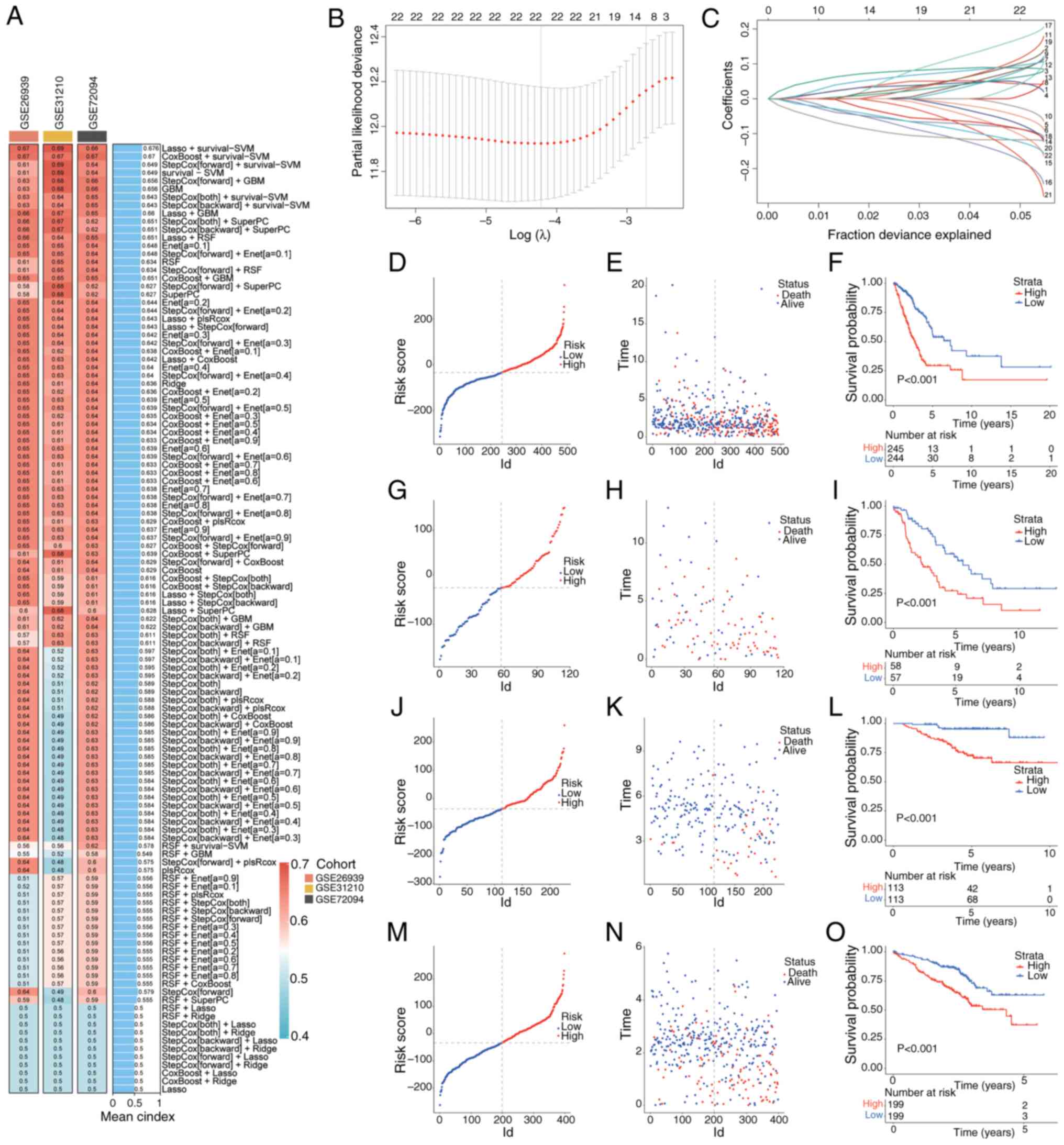

Construction of a risk scoring model

based on machine learning

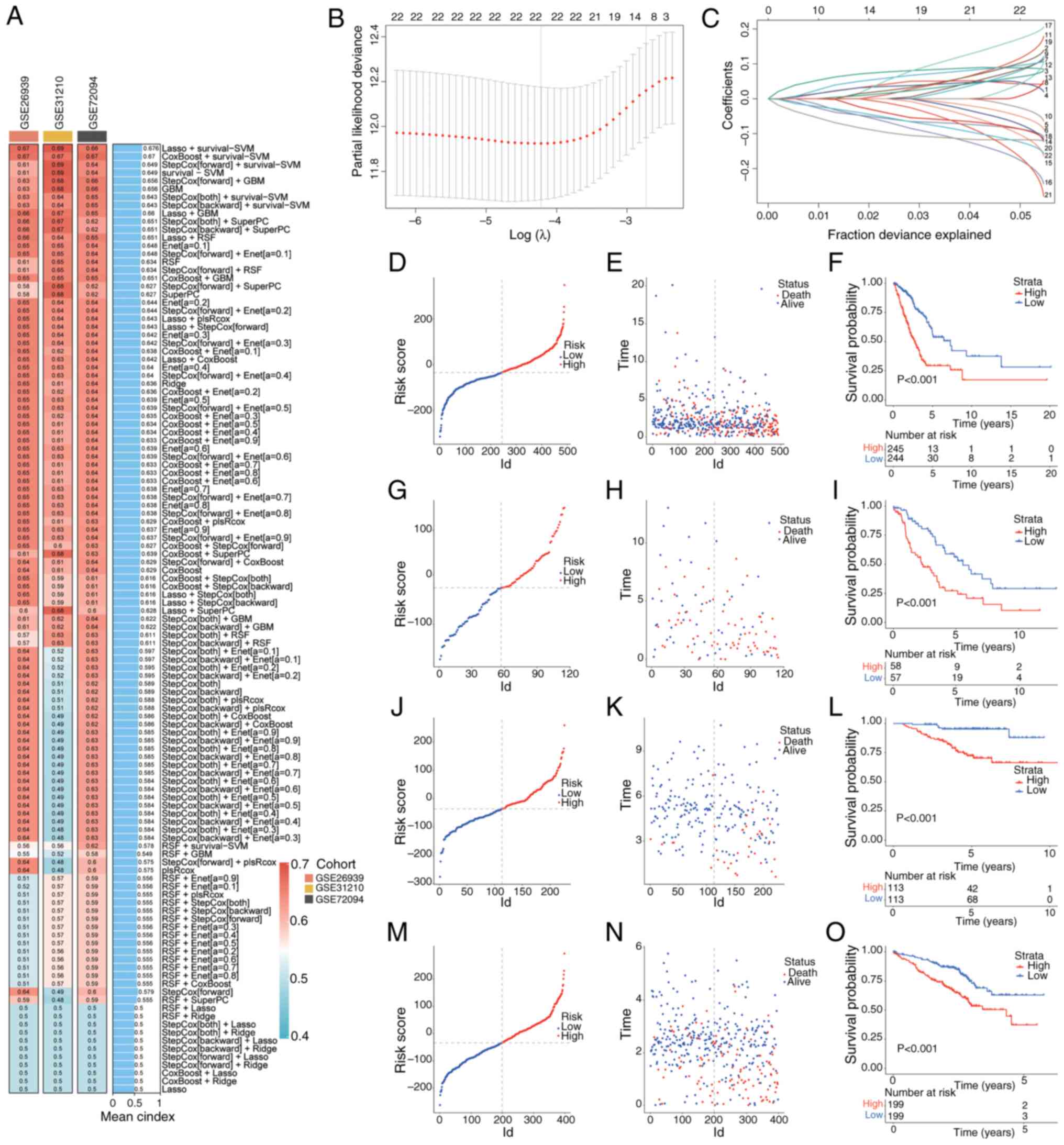

A total of >100 predictive models were tested

using 10 distinct algorithms across multiple datasets, including

TCGA LUAD and GEO datasets. The LASSO + survival-SVM algorithm

achieved the highest C-index (0.676) and was selected as the

optimal model (Fig. 2A-C). This

model identified 22 key prognostic genes, including metabolism of

cobalamin associated D (MMADHC), SOD2, human immunodeficiency

virus-1 Tat interactive protein 2 (HTATIP2), cytochrome C somatic

(CYCS), mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 (MPC1), adenylate kinase 2

(AK2). The distribution of patient risk scores in the training and

testing sets is shown in Fig. 2D, G, J

and M. Moreover, scatter plots were generated for the survival

times of patients in the high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 2E, H, K and N). Kaplan-Meier analysis

revealed that the high-risk group had significantly worse overall

survival (OS) than the low-risk group (Fig. 2F, I, L and O). To develop a

risk-score model, the following formula was applied: Risk

score=(0.04223596 × MMADHC) + (0.0910999 × SOD2) + (0.08776809 ×

HTATIP2) + (0.04116991 × CYCS) + (−0.05948219 × MPC1) +

(−0.09171416 × AK2) + (0.05753366 × MRPL44) + [0.01824556 ×

transforming growth factor β regulator 4 (TBRG4)] + [0.09307276 ×

mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM)] + (−0.03425415 ×

tetratricopeptide repeat domain 19) + (0.13106342 ×

coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 4) +

(0.09911277 × sideroflexin 1) + (0.06724052 × ATP binding cassette

subfamily D member 1) + (−0.08541973 × NADH: ubiquinone

oxidoreductase complex assembly factor 7) + (−0.11770888 × NOP2/Sun

RNA methyltransferase 4) + (−0.19223805 × NME/NM23 nucleoside

diphosphate kinase 6) + (0.18218013 × X-Prolyl aminopeptidase 3) +

(−0.09327797 × lipoyltransferase 1) + (0.11149579 × mitochondrial

methionyl aminopeptidase type 1D) + (−0.11764198 × carbonic

anhydrase 5B) + (−0.19248092 × kynurenine 3-monooxygenase) +

(−0.13196013 × alcohol dehydrogenase iron containing 1).

| Figure 2.Machine learning-based prognostic

risk score model construction. (A) C-index for each machine

learning prediction model calculated for the training and test

sets, with >100 models included. (B) LASSO regression analysis

established a model containing cuproptosis-related mitochondrial

genes associated with prognosis. (C) Coefficients of the LASSO

analysis. (D) Distribution of risk scores, (E) survival status and

time distribution in high- and low-risk groups. (F) Kaplan-Meier

curves showing the OS of patients in high- and low-risk groups in

TCGA training set. (G) Distribution of risk scores, (H) survival

status and time distribution in high- and low-risk groups, and (I)

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the OS of patients in high- and

low-risk groups in the GSE26939 test set. (J) Distribution of risk

scores, (K) survival status and time distribution in high- and

low-risk groups, and (L) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the overall OS

of patients in high- and low-risk groups in the GSE31210 test set.

(M) Distribution of risk scores, (N) survival status and time

distribution in high- and low-risk groups, and (O) Kaplan-Meier

curves showing the overall OS of patients in high- and low-risk

groups in the GSE72094 test set. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage

and selection operator; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; OS, overall

survival. |

Prognostic curves for high and low

risk scores in subgroups

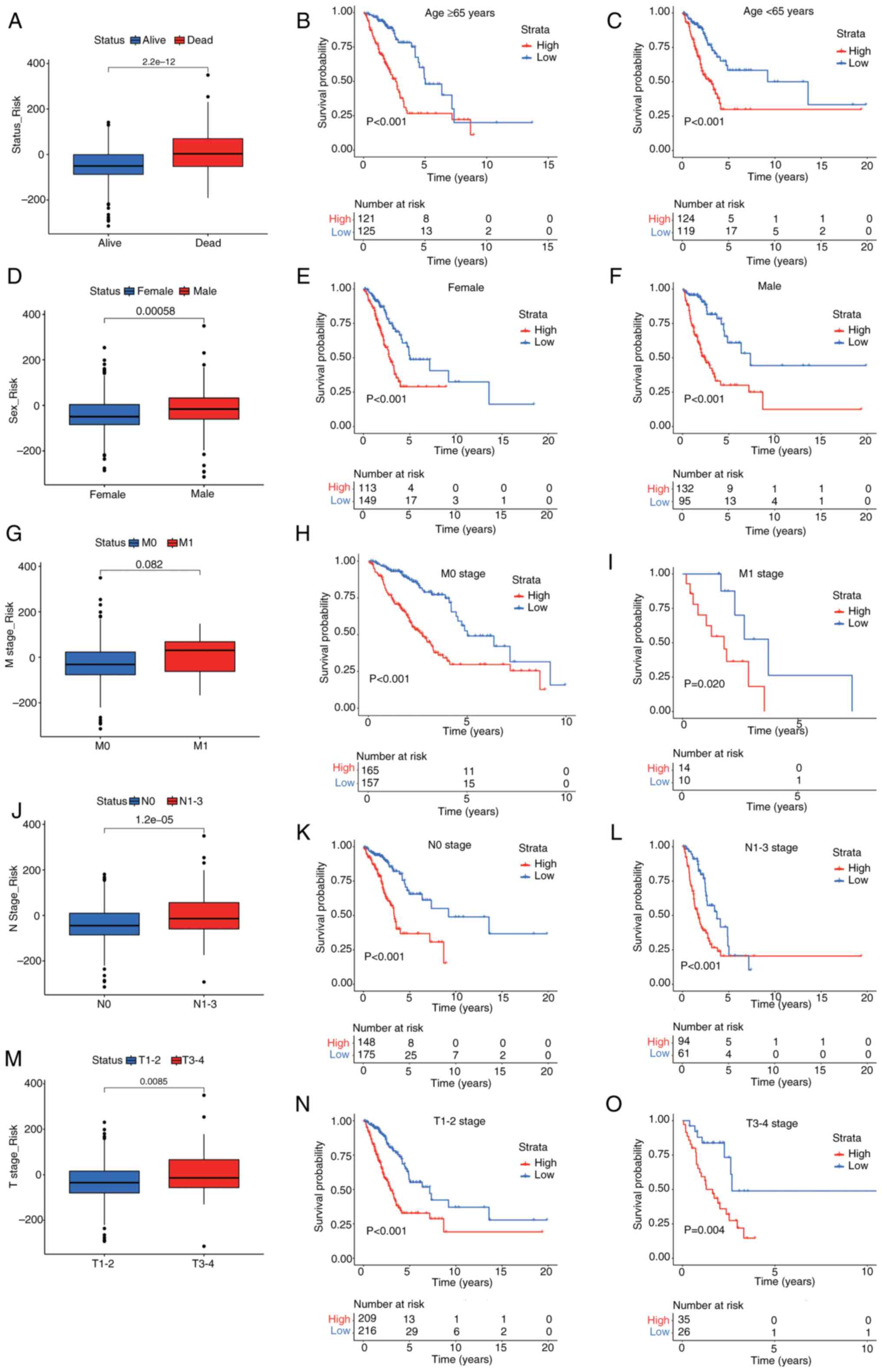

To further assess the clinical relevance of the risk

scoring model, it was applied it to survival prediction. The

results revealed that the cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene

risk scoring system had strong predictive power and stability

across several subgroups. Deceased patients had significantly

higher risk scores compared with survivors (Fig. 3A). After age stratification, it was

demonstrated that patients aged ≥65 years in the high-risk group

had a significantly reduced OS compared with those in the low-risk

group (Fig. 3B), and significant

differences were also observed in patients aged <65 years

(Fig. 3C). Sex stratification

analysis revealed that male patients had significantly higher risk

scores than female patients (Fig.

3D), and survival analysis (Fig. 3E

and F) demonstrated worse OS for both male and female high-risk

groups compared with low-risk groups. Regarding the M stage, the

results revealed a statistically significant trend in risk scores

between M0 and M1 patients (Fig.

3G); however, survival analysis demonstrated that high-risk M0

patients had significantly lower OS than low-risk patients

(Fig. 3H), with similar differences

observed in M1 patients (Fig. 3I).

For the N stage, the risk scores in N1-3 stages were significantly

higher than in the N0 stage (Fig.

3J). Moreover, survival analysis (Fig. 3K and L) indicated significantly

worse OS in the high-risk group for both N0 and N1-3 stages

compared with in the low-risk group. In the T stage analysis,

patients with T3-4 stages had significantly higher risk scores

compared with those with T1-2 stages (Fig. 3M). Survival analysis (Fig. 3N and O) further indicated

significantly shorter OS in the high-risk group compared with in

the low-risk group for T1-2 stages and T3-4 stages. In summary, the

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene-based risk scoring system

exhibited stable differentiation and clinical predictive value

across diverse subgroups, offering robust support for patient

stratification and risk management. Furthermore, this risk scoring

system has the potential to identify high-risk patients.

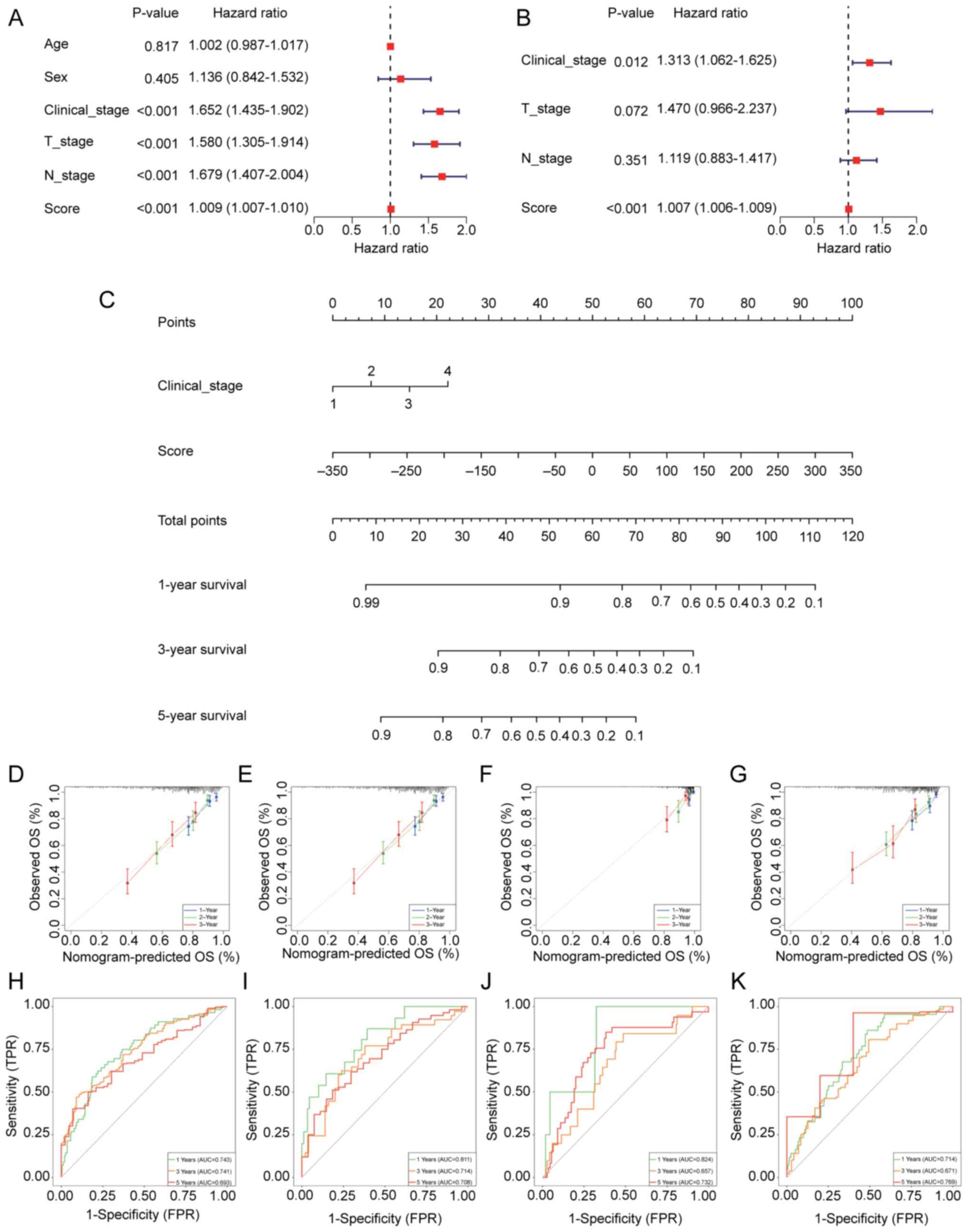

Construction of a prognostic

nomogram

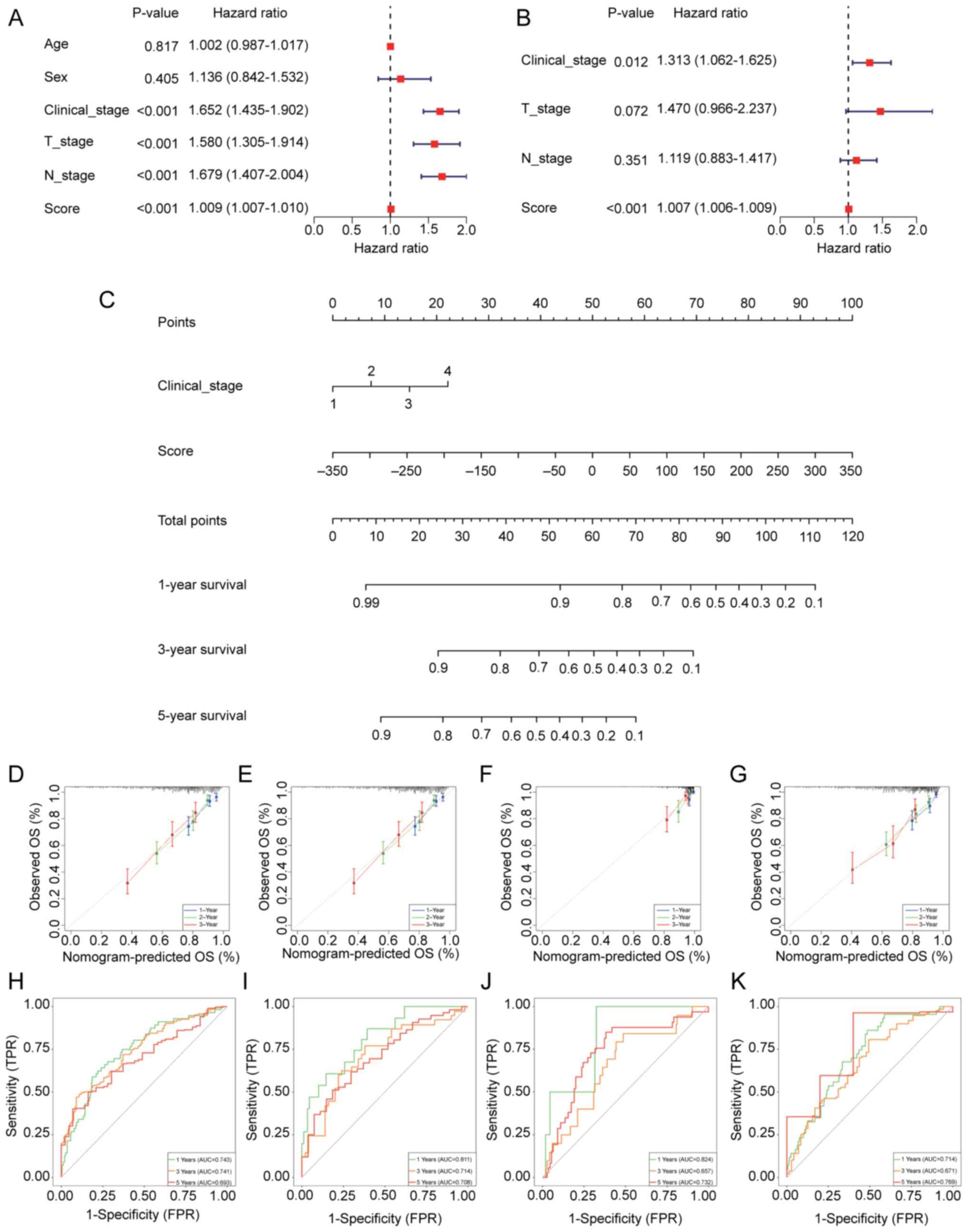

A univariate Cox regression analysis was performed,

which evaluated the influence of several clinical variables and

risk scores on the survival prognosis of patients with LUAD

(Fig. 4A). The analysis revealed

that age and sex were not significantly associated with survival

prognosis. However, clinical stage (HR=1.652;), T stage (HR=1.580)

and N stage (HR=1.679) were all significantly associated with a

worse prognosis, with higher stages indicating an increased risk of

death. Moreover, the risk score (HR=1.009) was confirmed as an

independent prognostic factor for survival, with higher scores

associated with a higher risk of death. Following the

identification of these four significant factors, a multivariate

Cox analysis was performed (Fig.

4B). Clinical stage and the cuproptosis-related mitochondrial

gene risk score were independent prognostic factors for survival in

patients with LUAD. A nomogram was then developed which combined

clinical stage and risk score to predict 1-, 3- and 5-year survival

(Fig. 4C). The nomogram enabled

precise survival predictions at several time points by summing the

total score based on the contributions from each parameter. To

evaluate the nomogram, TCGA-LUAD training set and three independent

validation datasets, GSE26939, GSE31210 and GSE72094, were used.

The calibration curves demonstrated that the predictions of the

nomogram for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival were highly consistent with

actual observations, showing accuracy similar to that of an ideal

model (Fig. 4D-G). Additionally,

ROC curves were utilized to assess the predictive performance of

the model (Fig. 4H-K). The results

indicated that in TCGA training set, the area under the curve (AUC)

values for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival were 0.731, 0.679 and 0.654,

respectively. In the GSE26939 dataset, the AUC values for 1-, 3-

and 5-year survival were 0.819, 0.787 and 0.753, respectively. The

GSE31210 dataset demonstrated a more improved performance, with AUC

values of 0.836, 0.806 and 0.779 for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival,

respectively. Moreover, for the GSE72094 dataset, the AUC values

for 1-, 3- and 5-year survival were 0.714, 0.678 and 0.670,

respectively. These results highlight the high predictive accuracy

and stability of the model across multiple datasets, with a

particularly notable performance in the GSE31210 and GSE26939

datasets.

| Figure 4.Nomogram construction to elucidate

lung adenocarcinoma prognosis. (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate

Cox regression analyses for clinical features and risk scores. (C)

Nomogram based on clinical features and risk scores. Calibration

curves showing the accuracy of predicted and actual values in (D)

TCGA training set, (E) the GSE26939 test set, (F) the GSE31210 test

set and (G) the GSE72094 test set. Receiver operating

characteristic curves evaluating the performance of the nomogram in

(H) TCGA training set, (I) the GSE26939 test sets, (J) the GSE31210

test set and (K) the GSE72094 test set. TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; T, tumor; N, node; OS, overall survival; FPR, false-positive

rate; TPR, true-positive rate; AUC, area under the curve. |

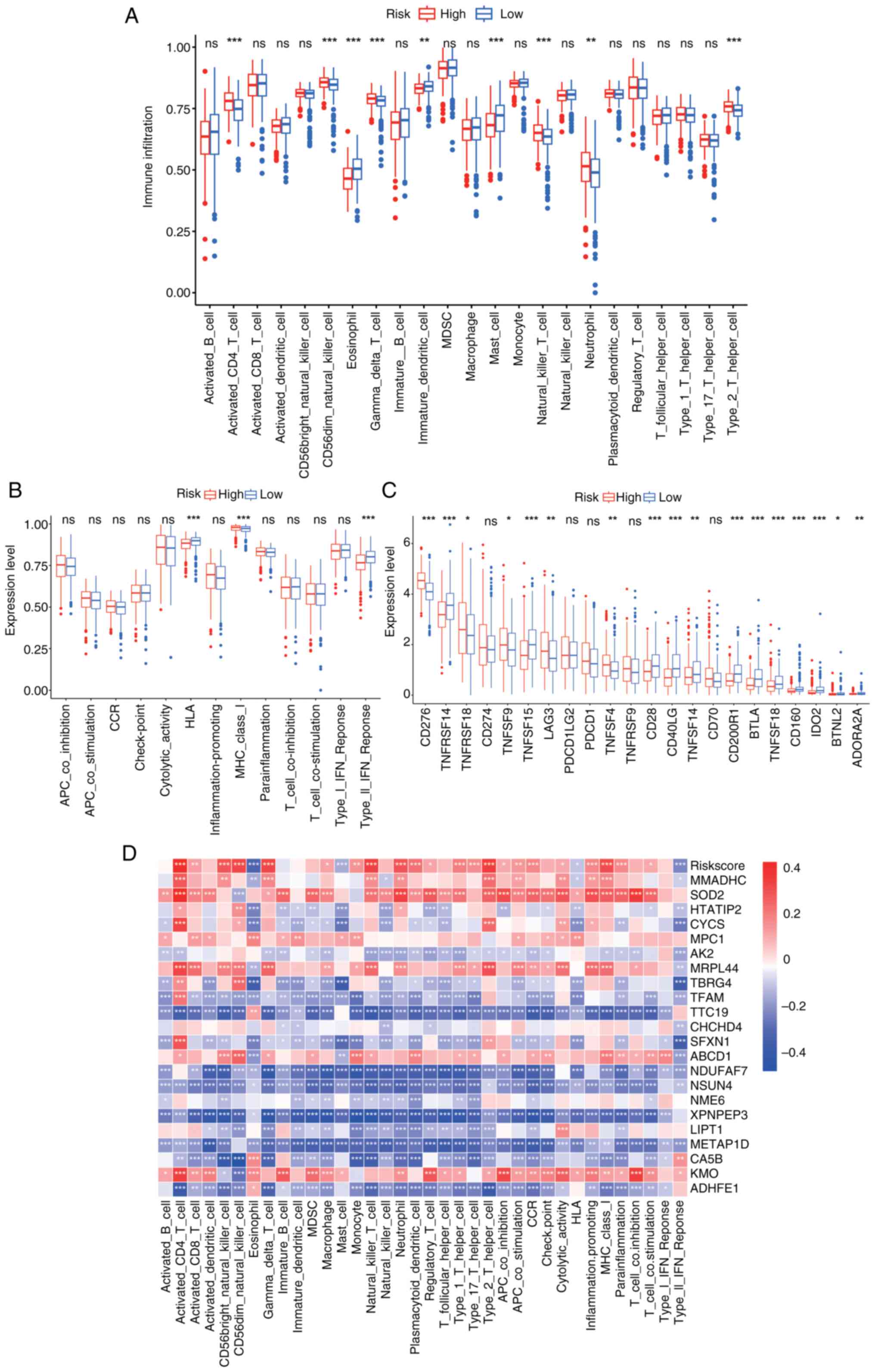

TME, immune checkpoints and

immune-related gene family analysis

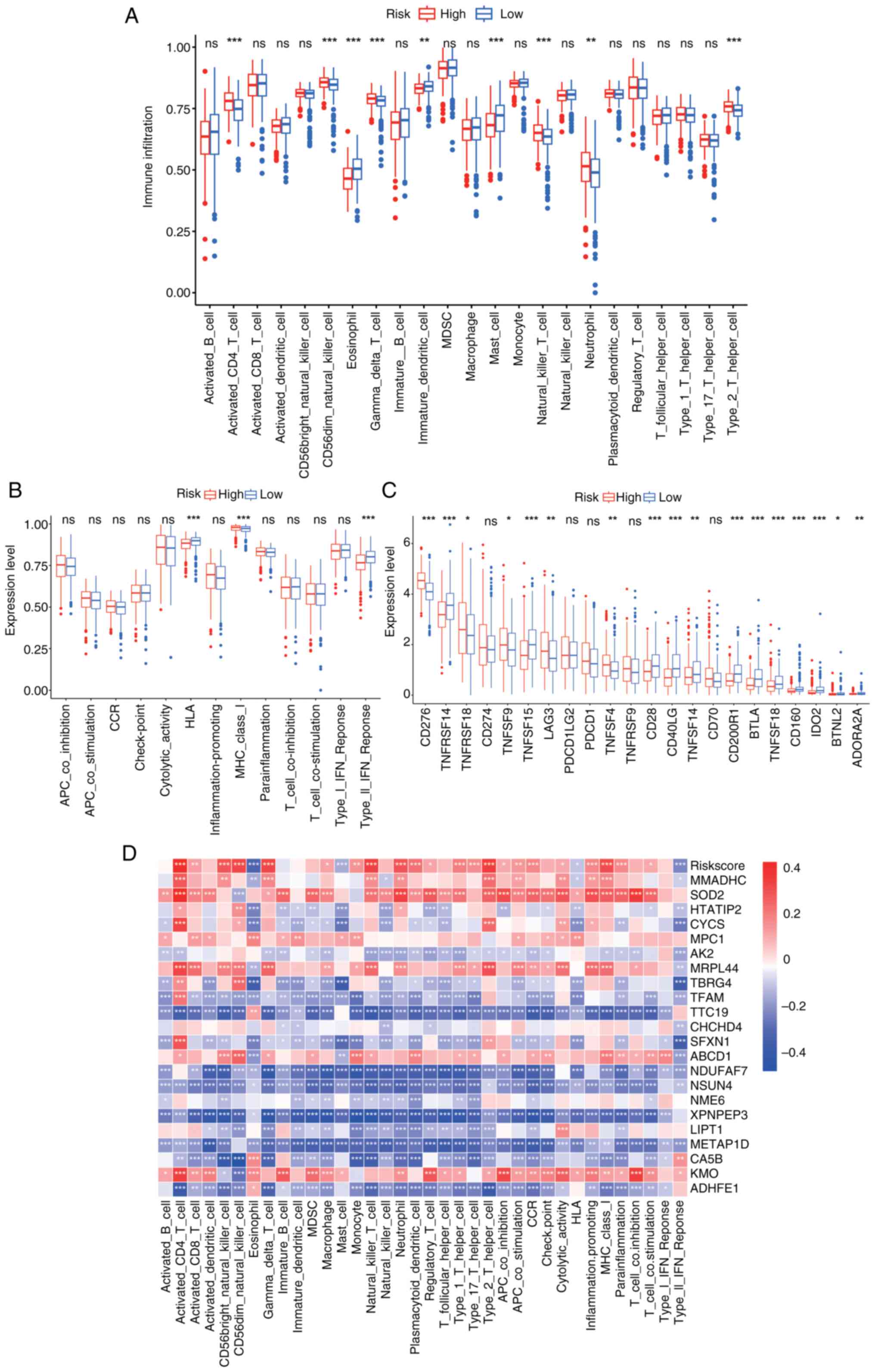

Significant differences were observed in the levels

of activated CD4 T cells, CD56dim natural killer cells,

eosinophils, γδ T cells, immature dendritic cells, mast cells,

natural killer T cells, neutrophils and type 2 T helper cells

between the high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 5A). The high-risk group displayed

higher levels of immunosuppressive cells, whilst the low-risk group

had a higher proportion of immune-activating cells. Further

analysis highlighted the presence of more immunosuppressive

pathways in the high-risk group, with the low-risk group showing

stronger immune activation (Fig.

5B). The expression levels of immune checkpoint genes [such as

programmed cell death protein 1, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)

and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4] were significantly

higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group (Fig. 5C), suggesting a more prominent

immunosuppressive environment. Furthermore, the correlations

between the 22 model genes, immune cell pathways and immune cells

were identified (Fig. 5D).

| Figure 5.Immune cell infiltration in high- and

low-risk groups. (A) Expression of 23 immune cell subtypes between

high- and low-risk groups. (B) Distribution and expression of

immune-related pathways in high- and low-risk groups. (C)

Expression of checkpoint-related genes in high- and low-risk

groups. (D) Correlation heatmap of risk scores and model genes with

immune cells and pathways. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

ns, not significant. TNFRSF, tumor necrosis factor receptor

superfamily; LAG3, Lymphocyte activation gene 3; PDCD1LG2,

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 2; CD200R1, CD200 receptor 1; BTLA,

B and T lymphocyte attenuator; IDO2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2;

BTNL2, Butyrophilin like 2; ADORA2A, Adenosine a2a receptor. |

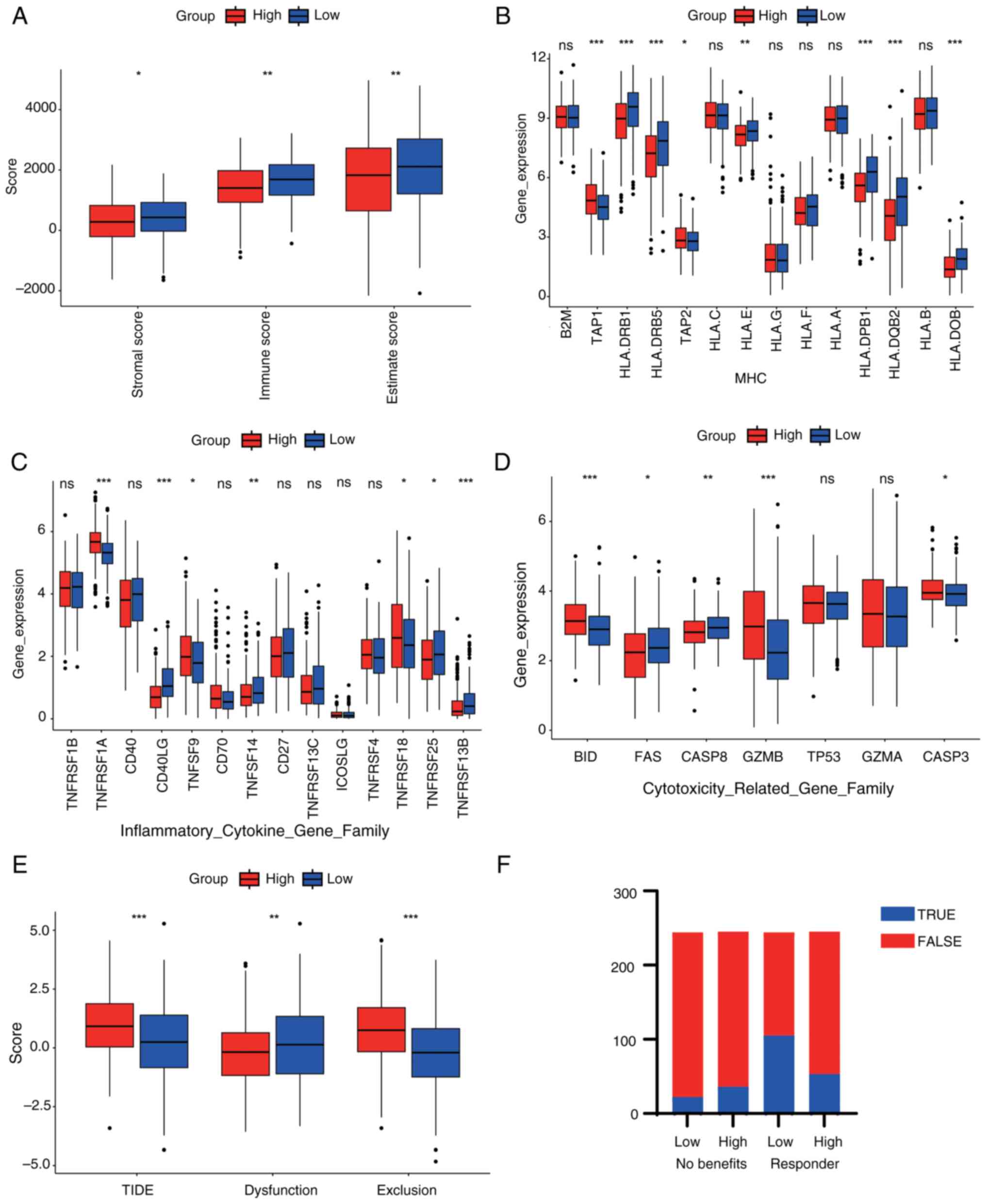

The stromal score was significantly higher in the

low-risk group, indicating a greater stromal component in these

tumors. The immune score was also markedly higher in the low-risk

group, suggesting enhanced immune cell infiltration. Similarly, the

estimate score, which integrates both stromal and immune scores,

was significantly elevated in the low-risk group. These findings

suggested that low-risk patients possess a tumor microenvironment

that is richer in stroma and more immunologically active,

potentially contributing to better prognosis (Fig. 6A). Moreover, significant variations

in the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene

family members [such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B, HLA-C and

HLA-DPB1] were revealed, with certain MHC genes downregulated in

the high-risk group, potentially suppressing their antigen

presentation function and promoting tumor immune evasion (Fig. 6B). Changes in the expression of

inflammatory factor gene families (such as TNFSF10, TNFRSF1A and

CD40) were also demonstrated (Fig.

6C), with certain inflammatory factors upregulated in the

high-risk group, which may indicate a chronic inflammatory state

that accelerates tumor progression. It was further revealed that

the expression levels of cytotoxic molecule-related gene families

(such as granzyme A, perforin 1, FAS and caspase 8) were generally

lower in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group, suggesting

a suppression of immune cytotoxicity, thus weakening immune killing

ability (Fig. 6D). Patients in the

high-risk group exhibited significantly higher TIDE and exclusion

scores compared with those in the low-risk group, suggesting a

greater likelihood of immune escape and decreased responsiveness to

immunotherapy. Additionally, the dysfunction score was also higher

in the high-risk group, indicating impaired T cell function

(Fig. 6E). Finally, patients in the

high-risk group exhibited a lower proportion of predicted

responders and fewer potential benefits from immunotherapy compared

to those in the low-risk group (Fig.

6F). In summary, the high-risk group demonstrated reduced

antigen presentation, increased chronic inflammation and diminished

immune killing capability, which may collectively contribute to

tumor immune evasion and progression.

In further analyses, immune cells with significant

expression differences (Fig. 5A)

were selected for survival prognosis analysis. In the high and low

expression groups of eosinophils, immature dendritic cells and type

2 T helper cells, the survival differences were demonstrated to be

significant (Fig. S2A-C). The

relative proportions of 22 immune cell types estimated by the

CIBERSORT algorithm showed distinct patterns between the high- and

low-risk groups, with the low-risk group exhibiting a higher

abundance of immune-active cells such as CD8+ T cells and activated

NK cells, suggesting a more favorable immune microenvironment

(Fig. S2D). In addition,

single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) analysis revealed significant

differences in the infiltration scores of 67 immune cell subtypes

between the two risk groups, with the low-risk group demonstrating

stronger enrichment in immune-related signatures, such as

antigen-presenting cells and cytotoxic lymphocytes (Fig. S2E).

Genetic variation and functional

analysis

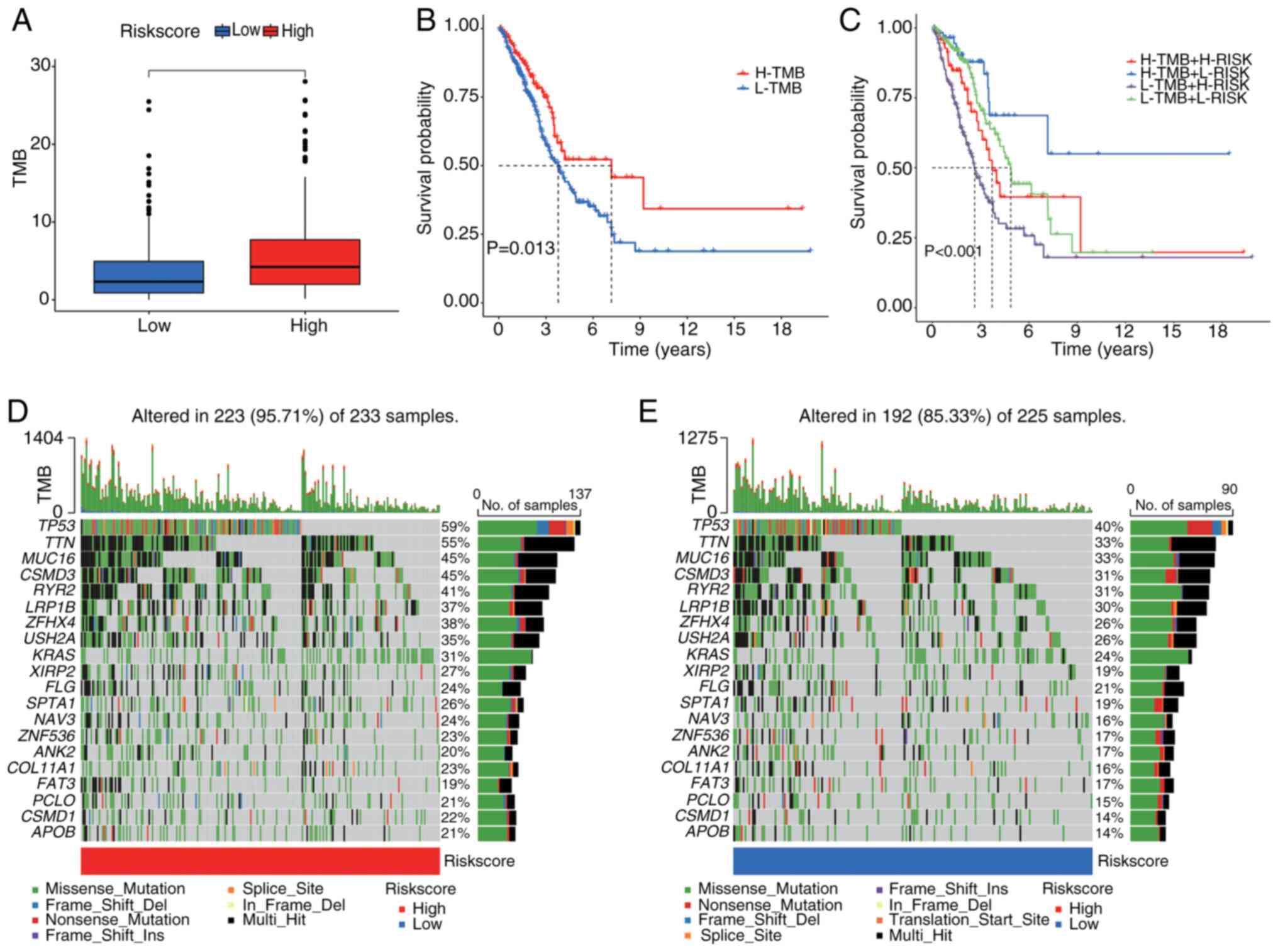

TMB was compared between the high- and low-risk

groups (Fig. 7A). The analysis

demonstrated that the high-risk group exhibited significantly

higher TMB levels than the low-risk group. Survival analysis

revealed that patients with elevated TMB had significantly improved

survival outcomes than those with lower TMB (Fig. 7B and C), suggesting an association

between TMB and prognosis. Moreover, when TMB was combined with the

risk score, patients in the low-TMB and high-risk group (L-TMB +

H-RISK) displayed the worst survival outcomes, whilst those in the

high-TMB and low-risk group (H-TMB + L-RISK) showed the best

survival results.

Additionally, in the high-risk cohort, 95.71% of the

223 samples had gene mutations (Fig.

7D). The most commonly mutated genes were tumor protein P53

(TP53; 59%), titin (TTN; 55%) and mucin 16 (MUC16; 45%), followed

by other frequently mutated genes such as CUB and sushi multiple

domains 3 (CSMD3), ryanodine receptor 2 (RYR2) and LDL receptor

related protein 1B (LRP1B). The predominant mutation types included

missense mutations and frameshift deletions. By contrast, in the

low-risk group, 85.33% of the 225 samples had gene mutations, with

TP53 (40%), TTN (33%) and MUC16 (33%) being the most frequently

mutated genes, followed by CSMD3, RYR2 and LRP1B (Fig. 7E). Whilst both groups shared common

mutated genes, the mutation frequency and TMB were markedly higher

in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group.

Role of risk score in immunotherapy

and drug sensitivity analysis

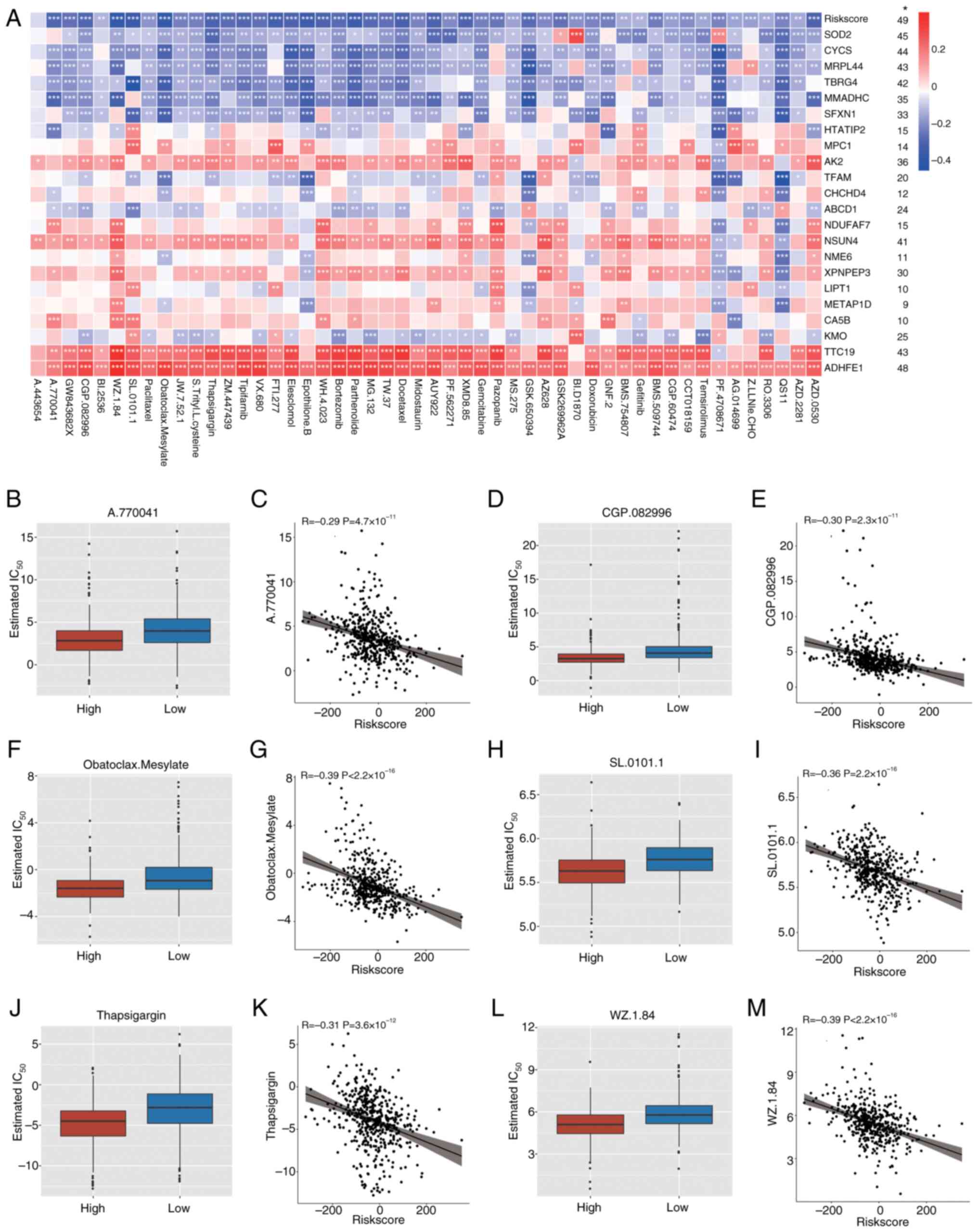

To assess the association between drug sensitivity,

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes and the risk score,

correlation analysis was performed. The results revealed

significant correlations between these genes, the risk score and

the sensitivity to several drugs (Fig.

8A). Several drugs demonstrated a significant negative

correlation with the risk score, suggesting that patients in the

high-risk group are more responsive to these treatments. The

IC50 values for A770041, CGP.082996, Obatoclax.Mesylate,

SL.0101.1, Thapsigargin and WZ.1.84 were notably lower in the

high-risk group than in the low-risk group, indicating stronger

inhibitory effects (Fig. 8B, D, F, H, J

and L). Furthermore, significant negative correlations were

demonstrated between risk scores and IC50 values for

these drugs (Fig. 8C, E, G, I, K and

M), suggesting that as the risk score increases, drug

sensitivity significantly improves. Specifically, for high-risk

patients, drugs such as A770041, CGP.082996, and Obatoclax Mesylate

may offer more effective therapeutic outcomes, indicating that the

risk score may serve as a crucial prognostic marker and a predictor

of drug response.

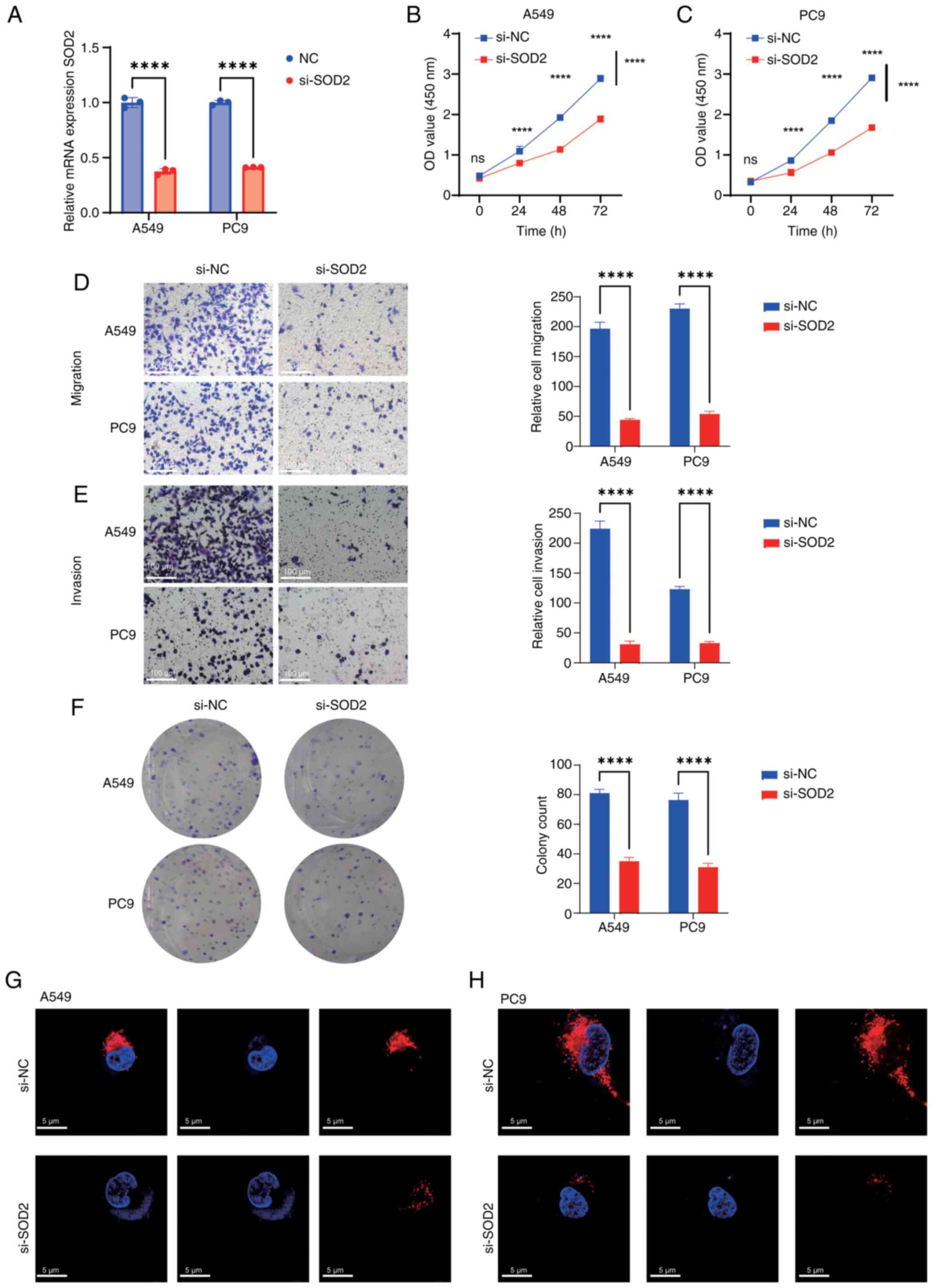

Knockdown of SOD2 inhibits malignant

behavior in LUAD

Among the aforementioned prognostic genes, SOD2,

CYCS, MRPL44, TBRG4, and MMADHC exhibited stronger drug

sensitivity, as indicated by a greater number of significantly

associated compounds (Fig. 8A). The

top 10 genes with high IC50 sensitivity and a

significant correlation with several drugs were screened, and SOD2

demonstrated a significant correlation with the highest number of

drugs. Therefore, we hypothesized that SOD2 has favorable

prognostic and therapeutic significance in LUAD, and the role of

SOD2 was further evaluated in vitro. First, SOD2 was

significantly knocked down in A549 and PC9 cells (Fig. 9A). Subsequently, CCK-8 assays

demonstrated a significant reduction in cell proliferation after

SOD2 knockdown in both cell lines compared with controls (Fig. 9B and C). Furthermore, it was

revealed that, compared with controls, there was a significant

decrease in cell migration and invasion (Fig. 9D and E), and a significant reduction

in cell proliferation (Fig. 9F)

post-SOD2 knockdown. Mitochondrial immunofluorescence assay

demonstrated that SOD2 knockdown markedly reduced mitochondrial

expression compared with controls (Fig.

9G and H).

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to develop

a prognostic model using cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes

for risk stratification and prognosis prediction in patients with

LUAD, which may offer valuable insights for guiding the treatment

of LUAD.

Cuproptosis is a newly identified form of PCD that

is triggered by excessive intracellular accumulation of copper ions

(53). The buildup of copper

induces mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and damage to

critical intracellular biomolecules, leading to cell death. Unlike

other forms of PCD, such as apoptosis and necroptosis,

copper-induced cell death does not involve the activation of

caspases, particularly caspase-3, which is a hallmark of classical

apoptosis. Instead, cuproptosis is characterized by copper

accumulation that disrupts mitochondrial lipid metabolism and

destabilizes iron-sulfur (Fe/S) cluster-containing proteins,

resulting in mitochondrial membrane instability, oxidative damage

and subsequent cell death (10).

In LUAD, a highly invasive and metastatic subtype of

NSCLC, copper toxicity has been reported to promote mitochondrial

dysfunction (54), a hallmark of

cancer cell metabolic reprogramming. Tumor cells often exhibit the

‘Warburg effect’, favoring glycolysis over oxidative

phosphorylation for energy production even in the presence of

oxygen (55). This metabolic shift

not only supports rapid tumor cell proliferation but also renders

LUAD cells more susceptible to mitochondrial damage caused by

excess copper accumulation (56).

Elevated serum copper levels have been observed in patients with

lung cancer, with significantly increased levels in individuals

with advanced-stage disease compared with those diagnosed at

earlier stages (57). Copper ions

can promote tumor angiogenesis by activating hypoxia-inducible

factor-1 (HIF-1) and upregulating VEGF expression, thereby

facilitating the development and metastasis of lung cancer cells.

Additionally, copper ions may activate the AKT signaling pathway,

leading to anti-apoptotic effects in lung cancer cells. They also

enhance glycolysis and alter amino acid metabolism, further

reshaping the TME (58).

Elesclomol, an antitumor agent that targets

mitochondrial metabolism, exerts part of its anticancer activity by

inducing cuproptosis (59).

Disruption of intracellular copper homeostasis can lead to

metabolic imbalance and cell death. Disulfiram (DSF) has also been

reported to elevate intracellular copper levels, thereby inducing

death in lung cancer cells (60).

Moreover, the interplay between cuproptosis and mitochondrial

dysfunction provides critical insights into the progression and

therapeutic resistance of LUAD. Therefore, targeting

cuproptosis-related mechanisms, particularly by restoring and

regulating mitochondrial function during treatment, may offer novel

strategies for LUAD therapy. Therefore, the present study aimed to

identify a distinct cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene

signature with significant prognostic value for LUAD, providing

potential molecular targets for precision oncology (61).

Through the analysis of TCGA dataset, 501 genes

related to cuproptosis and mitochondrial function were identified.

Using univariate Cox regression, LASSO regression and multiple

machine learning algorithms, 22 key genes significantly associated

with the prognosis of LUAD were screened. These genes (for example,

SOD2, MMADHC, CYCS, MPC1 and TFAM) are involved in mitochondrial

energy metabolism, oxidative stress response and the regulation of

apoptosis (62). The model was

constructed using TCGA-LUAD dataset and assessed in three

independent GEO datasets (GSE26939, GSE31210 and GSE72094). The

results demonstrated that the risk score based on these 22

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial genes effectively distinguished

between high- and low-risk patients. High-risk patients exhibited

worse survival outcomes across several clinical subgroups (age,

sex, clinical stage and TNM stage). Furthermore, both univariate

and multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed the risk score as

an independent prognostic factor for LUAD. A nomogram integrating

the risk score and clinical variables (clinical stage, T stage and

N stage) was constructed to predict 1-, 3- and 5-year survival

probabilities, thereby validating the clinical utility of the

model.

Research by Liu et al (63) employed LASSO regression to screen

for cuproptosis-related genes and included only two external

validation cohorts, without reporting ROC AUC values or performing

phenotype-related experiments such as CCK-8 or Transwell assays. By

contrast, the present study adopted a more comprehensive approach

by utilizing 117 machine learning algorithms to select prognostic

genes, incorporating three external GEO validation datasets, and

calculating the corresponding ROC AUC values. Furthermore,

extensive external validations were performed, including RT-qPCR,

CCK-8, Transwell and colony formation assays, and

immunofluorescence experiments. Similarly, the study by Yang et

al (64) also relied on LASSO

modeling to identify cuproptosis-related stemness genes, yet

validation was limited to a single GEO dataset (GSE141569) with AUC

values of <0.7, thus lacking persuasive power. The present

study, however, included three external GEO cohorts (GSE26939:

0.811, 0.714 and 0.708; GSE31210: 0.824, 0.657 and 0.732; and

GSE72094, 0.714, 0.671 and 0.769), most of which achieved AUC

values of >0.7, highlighting the robustness of the prognostic

model. Furthermore, research by You et al (65) only utilized LASSO for gene selection

and performed RT-qPCR as the sole validation method, whereas the

present work provided more comprehensive external validation

encompassing RNA expression, phenotypical assays in two cell lines

and immunofluorescence analysis. The study by Liang et al

(66), which compared Deep Neural

Network and Cox models, was limited by a single external validation

dataset (GSE68465). The time-dependent ROC analysis for 1-, 3-, and

5-year survival prediction yielded AUC values of 0.606, 0.621, and

0.603, respectively, all of which were <0.7, indicating

suboptimal prognostic performance. By contrast, the multi-model

screening using 117 machine learning algorithms in the present

study enabled the identification of optimal models with stronger

validation performance across multiple GEO datasets. Finally, the

study by Zhang et al (67)

used GSE68465 as the training set and TCGA, GSE72094 and GSE37745

as validation cohorts. As TCGA is the largest and most widely used

LUAD cohort, the authors believe it should serve as the training

dataset, with the GEO cohorts more suited for external validation.

Additionally, whilst the model by Zhang et al (67) yielded unsatisfactory time-dependent

AUC values in the GSE37745 dataset (0.658, 0.646 and 0.630 for

predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival, respectively), the

prognostic model in the present study demonstrated notably greater

generalizability and predictive accuracy across multiple GEO

datasets. Collectively, the present study integrated a more

advanced machine learning framework, comprehensive external

validations and robust ROC performance, thus offering a marked

advancement over existing research in this field.

Zhao et al (21) established a prognostic model based

on hypoxia- and mitochondria-related genes, which were selected

using weighted gene co-expression network analysis. The model

incorporated 16 genes [pyruvate kinase M1/2 (PKM), S100 calcium

binding protein A16, related RAS viral (r-ras) oncogene homolog,

tubulin α4a, plakophilin 3, potassium channel tetramerization

domain containing 12, lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase 1,

ITPR interacting domain containing 2, mitotic spindle organizing

protein 2A, leukemia inhibitory factor receptor alpha, protein

tyrosine phosphatase receptor type M, large tumor suppressor kinase

2, PDLIM1 interacting kinase 1 like, golgin RAB6-interacting,

protocadherin 7, and cadherin-like and PC-esterase domain

containing 1). The prognostic performance was evaluated using ROC

analysis, with AUC values of 0.721, 0.711 and 0.671 for 1-, 3- and

5-year survival in TCGA cohort, respectively. External validation

was performed using GSE31210 (AUC, 0.756, 0.641 and 0.669,

respectively) and GSE72094 (AUC, 0.672, 0.670 and 0.673,

respectively). Although the study also assessed the TME and drug

sensitivity, the model construction was based solely on a single

LASSO analysis, and external validation was limited to two datasets

without in vitro experimental validation. Moreover, Jiang

et al (26) developed a

prognostic model derived from cuproptosis- and anoikis-related

genes [eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 α kinase 3

(EIF2AK3), IKAROS family zinc finger 3 (IKZF3), integrin subunit

alpha V (ITGAV), O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT),

polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), TNF receptor associated factor 2

(TRAF2), and X-ray repair cross complementing 5 (XRCC5)], which

were selected using Pearson correlation analysis (threshold of

>0.3). The model was constructed using the LASSO algorithm and

further evaluated using immunohistochemistry data from the Human

Protein Atlas database, comparing gene expression between LUAD and

adjacent normal tissues. The ROC values for survival prediction in

TCGA cohort were 0.732, 0.743 and 0.712 for 1-, 3- and 5-year

survival, respectively. External validation in GSE26939 achieved

AUCs of 0.663, 0.614 and 0.599, respectively. In comparison with

the aforementioned models, the prognostic model in the present

study was constructed using a more robust and systematic pipeline.

First, prognostic genes were screened using Pearson correlation

analysis (threshold of >0.3), followed by evaluation across 117

machine learning algorithms to select the optimal model, thereby

ensuring optimum predictive performance. In terms of biological

insight, the present study comprehensively analyzed the TME using

ssGSEA for immune checkpoint and immune pathway enrichment

analysis, combined with immune scoring, TIDE prediction and

CIBERSORT for immune cell infiltration quantification. Furthermore,

TMB analysis was performed, not only comparing mutation counts

between high- and low-risk groups but also integrating survival

analysis to reveal the prognostic impact of TMB. A detailed

comparison between previous research and the present study is

provided in Table SII.

The present study explored a mitochondrial gene

signature related to cuproptosis, with a particular focus on SOD2.

This gene signature shares a common foundation with two recently

published signatures: Zhao et al (21), which focused on hypoxia and

mitochondrial-related genes, especially PKM2, and Jiang et

al (26), which identified a

cuproptosis-anoikis-related gene signature, including EIF2AK3,

IKZF3, ITGAV, OGT, TRAF2, XRCC5 and PLK1. The present study, along

with the gene signatures proposed by Zhao et al (21) and Jiang et al (26), aimed to identify and evaluate

mitochondria-related gene signatures with the potential to serve as

diagnostic and therapeutic targeting biomarkers in LUAD. The study

by Zhao et al (21) mainly

linked mitochondrial dysfunction with hypoxia. PKM2 is a

rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis, catalyzing the conversion of

phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate. In tumor cells, it predominantly

exists in a low-activity dimeric form. PKM2 directly binds to

integrin β1, activating the FAK/SRC/ERK axis to promote tumor

metastasis and support angiogenesis. Furthermore, using integrin β1

inhibitors has been reported to markedly reduce tumor migration and

invasion, indicating that PKM2 could serve as a potential

diagnostic marker (68,69). Furthermore, in the signature by

Jiang et al (26), genes

such as EIF2AK3, IKZF3, ITGAV and OGT serve key roles in cell

survival, adhesion and oxidative stress responses. EIF2AK3, also

known as EIF2α kinase, is an important regulator of cellular stress

responses. It modulates the cell cycle and helps cancer cells

sustain growth, supporting the malignant phenotype of tumors

(70). ITGAV, a cell adhesion

molecule, promotes the interaction between cells and the

extracellular matrix, helping cells resist anoikis (death induced

by detachment), thereby assisting cancer cells in surviving and

circulating in the bloodstream (71). OGT, by modulating the glycosylation

of cell adhesion proteins, enhances the interaction between cells

and the matrix, potentially serving a role in resisting anoikis,

allowing cancer cells to survive after detaching from their primary

site and migrate to new locations (72).

The present study investigated the

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene signature. SOD2, identified

through drug sensitivity-related screening, is a mitochondrial

antioxidant enzyme that emphasizes the core role of oxidative

stress and mitochondrial damage in cuproptosis and cancer

progression. SOD2 protects cells from oxidative damage by clearing

ROS in the mitochondria, which is particularly important in cancer

cells, as they typically produce large amounts of ROS during

metabolic processes. Overexpression of SOD2 may help tumor cells

resist oxidative damage, promoting their survival in harsh

microenvironments (73). Therefore,

the development of SOD2 inhibitors or ROS modulators may increase

ROS levels, promoting cancer cell death, which has clinical

therapeutic implications. As such, SOD2 could serve as a potential

therapeutic marker in clinical treatments.

The innovations of the present study were as

follows: First, 117 machine learning algorithms (comprising 10

types of freely combinable machine learning methods) were applied

to identify prognostic genes, and the optimal model was selected

based on the highest concordance index (C-index). Second, three GEO

datasets were used for external validation, whereas most existing

studies used only one or two, thereby providing a more

comprehensive validation of model reliability and generalizability.

Third, the model in the present study achieved relatively high ROC

values in both TCGA validation and all three GEO test sets, with

several values reaching ≤0.8. The calibration curve closely aligned

with the ideal diagonal, indicating notable predictive performance

and strong clinical applicability (62). Moreover, the TME and TMB were

analyzed, and the results demonstrated that patients in the

high-risk group exhibited a greater number of gene mutations. This

provides important insights for guiding targeted therapy and

assessing prognosis. Finally, drug sensitivity analysis was

performed for 198 molecular drugs and the top 40 statistically

significant drugs were identified, offering clinical guidance for

chemotherapy and targeted therapy selection. Using the

‘oncoPredict’ R package, the IC50 values of these 198

drugs were evaluated, providing a valuable reference for future

personalized treatment strategies. Moreover, as the central theme

of the present study was the cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene

signature, in vitro experiments were performed using

immunofluorescence techniques to visualize mitochondrial changes

after SOD2 gene knockdown, thereby validating the functional

relevance of mitochondria in this context.

The TME serves a key role in tumor progression,

immune evasion and treatment response. A study by Isomoto et

al (74) reported that the

immune landscape surrounding EGFR-mutant tumors in NSCLC exhibited

a lack of T cell infiltration, along with a reduced PD-L1+/CD8+

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes ratio, underscoring the critical

role of the TME in immune therapy (75). The present study identified

significant differences in immune cell infiltration between high-

and low-risk patients with LUAD. Specifically, the high-risk group

had a higher proportion of immunosuppressive cells, including

regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which

suppress antitumor immune responses. By contrast, the low-risk

group exhibited a higher proportion of immune-activated cells, such

as CD4+ T cells and natural killer cells, suggesting a

more favorable immune microenvironment.

The present study also assessed the association

between the cuproptosis-related mitochondrial gene signature and

drug sensitivity. The correlation between risk scores and the

sensitivity of 198 different drugs was evaluated. The findings

indicated that high-risk patients had increased sensitivity to

specific chemotherapeutic and targeted therapeutic agents,

suggesting that these patients may benefit from certain drug

treatments. Additionally, the results revealed that drugs such as

A770041 and Obatoclax Mesylate were significantly associated with

risk scores, implying that these drugs might be more effective in

high-risk patients with LUAD compared with low-risk patients. In

the study by Chen et al (75), Obatoclax Mesylate, a Bcl-2 family

antagonist, was used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies

and solid tumors. The nanoparticle-targeted delivery system of this

drug improved its circulation time and accelerated delivery to

tumor sites, increasing tumor-targeting specificity.

Furthermore, Fig.

8A illustrates the strong correlation between MMADHC gene

expression and the IC50 values of several drugs.

However, the role of MMADHC in lung cancer or other malignancies

remains unexplored. Bhat et al (76) identified a homozygous pathogenic

mutation in MMADHC, which is associated with homocystinuria. By

contrast, the SOD2 gene, strongly correlated with the

IC50 values of several drugs, has been associated with

tumor development and progression. SOD2 is a crucial antioxidant

enzyme in humans and is part of the superoxide dismutase family

(77). Located on chromosome 6, the

SOD2 gene encodes the SOD2 protein found in mitochondria,

responsible for neutralizing superoxide anions

(O2−) and converting them into hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2), thus mitigating oxidative

stress and cellular damage. SOD2 can eliminate excessive

mitochondrial ROS. Deficiency in the sirtuin 3/SOD2 signaling

pathway leads to increased mitochondrial ROS and mitochondrial

damage. The underlying mechanisms include loss of mitochondrial

membrane potential, abnormal mitochondrial ultrastructure and

oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA (78). Hernandez-Saavedra and McCord

(79) suggested that genetic

variations in SOD2 may increase the risk of cancer by creating

potential glucocorticoid response elements. Additionally, Zhao

et al (80) reported that

overexpression of microRNA-512-5p increased SOD2 levels, promoting

tumorigenesis and progression in NSCLC. At present, the specific

regulatory role of SOD2 in the cuproptosis pathway has not been

fully elucidated. However, recent findings by Li et al

(81) indirect supported a

potential association. In the present study, PX478, a HIF-1α

inhibitor, was reported to enhance oxidative stress in A549 cells

treated with DSF, as indicated by increased levels of ROS and

malondialdehyde, accompanied by a reduction in SOD levels. This

elevated oxidative stress subsequently upregulated ATPase copper

transporting β (ATP7B) expression, thereby promoting cuproptosis

and ultimately inhibiting the progression and metastasis of NSCLC

cells. Moreover, DSF treatment markedly decreased the viability of

A549 cells, and was associated with simultaneous upregulation of

ATP7B and PD-L1. Notably, when the dosage of DSF was insufficient

to induce robust cuproptosis, the increased PD-L1 expression

potentially contributed to enhanced immune suppression and immune

evasion, which may increase the risk of tumor cell proliferation

and metastasis. Notably, combination therapy with anti-PD-L1 agents

further augmented the antitumor effects of DSF, highlighting the

potential synergistic benefits of integrating immune checkpoint

blockade with cuproptosis-based therapeutic strategies in

NSCLC.

Copper ions can catalyze the formation of ROS,

leading to cellular damage, including mitochondrial dysfunction.

This is particularly evident in LUAD cells, as these cells are

often already in a high-oxidative state due to their rapid

metabolic activity. Cuproptosis, a form of cell death induced by

copper, takes advantage of this vulnerability (82). By increasing copper ion levels in

tumor cells, it can push them beyond their capacity to handle ROS,

ultimately leading to cell death. This mechanism may selectively

target cancer cells that are already primed to handle oxidative

stress while sparing normal cells (83). Although copper homeostasis is

critical for tumor progression, copper overload disrupts cellular

processes and induces cell death. Inducing cuproptosis in LUAD is a

potential strategy to exploit the inherent oxidative stress and

metabolic dysregulation of cancer cells, thereby selectively

killing them. By targeting copper transport mechanisms (such as

ATP7B) or using copper ionophores (such as DSF), it is possible to

selectively accumulate copper in cancer cells to induce

cuproptosis, thereby reducing tumor proliferation, migration and

metastasis (84). Copper ions also

serve a role in angiogenesis by activating VEGF. However, in cancer

cells, the regulation of copper uptake, distribution and efflux is

often impaired, leading to excessive intracellular copper

accumulation that drives the cells into a programmed death state

(cuproptosis). There is growing interest in exploiting this

imbalance in copper homeostasis to achieve therapeutic effects

(85–87). Therefore, increasing copper levels

beyond physiological thresholds could be a way to ‘push’ cancer

cells into an irreversible cell death state. In summary, whilst

copper can promote tumor growth by supporting cellular functions,

targeting copper overload via cuproptosis is an emerging strategy

to selectively induce cancer cell death in LUAD. This approach aims

to exploit the vulnerability of cancer cells to excess copper,

making cuproptosis a promising mechanism to consider in LUAD

treatment.

The study by Tsvetkov et al (88) reported that excessive Cu ions led to

ROS generation via the Fenton reaction. When intracellular copper

ion levels increase tenfold, it triggers cuproptosis, causing lipid

peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction. DSF can induce

apoptosis in tumor cells through copper ions, as reported in

vitro by Li et al (81),

where DSF promoted overexpression of ATP7B and PD-L1, inhibiting

the cell viability of A549 cells and enhancing oxidative stress,

which led to tumor cell apoptosis. The cuproptosis inducer DSF

combined with sulfasalazine (SAS) has been proposed as a new

antitumor drug. DSF regulates intracellular copper ion levels,

promoting cuproptosis in NSCLC tumor cells, and enhances

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated oxidative

stress-induced cytotoxicity. In a mouse model, SAS combined with

DSF-Cu markedly reduced both tumor size and number. In a mouse

model, SAS combined with DSF-Cu markedly reduced both tumor size

and number (89). Moreover, in

vitro research by Liu et al (90) demonstrated that DSF-Cu exhibited

anti-angiogenic activity by inhibiting EGFR, fibroblast growth

factor receptor 1 and IGF-1Rβ. It also notably suppressed stem cell

transcription factors such as SRY-box 2, thereby inhibiting tumor

stem cell proliferation and invasion. Additionally, it enhanced

cuproptosis in tumor cells. DSF-Cu can synergize with the WEE1

inhibitor Adavosertib to induce G2/M phase arrest and promote

cuproptosis in NSCLC tumor cells (91). Furthermore, in in vitro mouse

models, the combination of DSF-Cu and Adavosertib markedly reduced

tumor size and weight, especially in a p53-deficient xenograft

model (91).

While the present study offers valuable insights

into the prognostic significance of the cuproptosis-mitochondrial

gene signature in LUAD, several limitations exist. First, despite

the high predictive accuracy of the model across multiple datasets,

its clinical applicability requires further validation in

prospective clinical trials. Second, although based on extensive

RNA sequencing data, future studies could include single-cell RNA

sequencing and spatial transcriptomics to explore cellular

heterogeneity and expression patterns in different tissue areas.

Third, although the machine learning model predicts survival

outcomes effectively, its predictive power could be improved by

incorporating additional clinical variables (such as treatment

history and molecular subtypes).

In conclusion, the present study established a

comprehensive prognostic model based on the copper

death-mitochondrial-related gene signature, which not only provides

new insights into the molecular mechanisms of LUAD but also offers

valuable guidance for clinical decision-making. Future research

should further validate the findings of the present study, explore

novel therapies targeting the copper death pathway, and improve

treatment outcomes for patients with LUAD through personalized

therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Tianjin Municipal Health

Commission, the Tianjin Key Medical Discipline Sub-project (grant

no. TJLCMS2021-06), the Tianjin Municipal Education Commission

through the General Project of the Natural Science Foundation

(grant no. 2020KJ162), the Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (grant no.

320.6750.2022-11-43), the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (grant no. 82172569), the Natural Science Foundation of

Tianjin (grant no. 23JCYBJC01010) and the Tianjin Key Medical

Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (grant no.

TJYXZDXK-061B).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YHL, WHZ, ZXZ and ZXD conceived and designed the

study, analyzed and interpreted data, drafted and critically

revised the manuscript, approved the final version, and agree to be

accountable for all aspects of the work. HH, CD, YWL, MHL, HBZ and

MW analyzed and interpreted data; assisted with figure preparation,

visualization, reference organization, and manuscript drafting or

revision; reviewed and approved the final version. JC supervised

the entire project, contributed to study design and data

interpretation, critically reviewed the manuscript, approved the

final version. HLZ performed the experiments, supervised laboratory

work, obtained funding and resources, critically reviewed the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. YHL and WHZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang Y, Vaccarella S, Morgan E, Li M,

Etxeberria J, Chokunonga E, Manraj SS, Kamate B, Omonisi A and Bray

F: Global variations in lung cancer incidence by histological

subtype in 2020: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol.

24:1206–1218. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Florez N, Kiel L, Riano I, Patel S,

DeCarli K, Dhawan N, Franco I, Odai-Afotey A, Meza K, Swami N, et

al: Lung cancer in women: The past, present, and future. Clin Lung

Cancer. 25:1–8. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Carter-Harris L: Lung cancer stigma as a

barrier to medical help-seeking behavior: Practice implications. J

Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 27:240–245. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu HI, Chiang CJ, Su SY, Jhuang JR, Tsai

DR, Yang YW, Lin LJ, Wang YC and Lee WC: Incidence trends and

spatial distributions of lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell

carcinoma in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 13:16552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nakagawa K, Yoshida Y, Yotsukura M and

Watanabe SI: Minimally invasive open surgery (MIOS) for clinical

stage I lung cancer: Diversity in minimally invasive procedures.

Jpn J Clin Oncol. 51:1649–1655. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Duma N, Santana-Davila R and Molina JR:

Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and

treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 94:1623–1640. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Doval DC, Desai CJ and Sahoo TP:

Molecularly targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer: The

evolving role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Indian J Cancer. 56

(Suppl 1):S23–S30. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Laerum D, Strand TE, Brustugun OT,

Gallefoss F, Falk R, Durheim MT and Fjellbirkeland L: Evaluation of

sex inequity in lung-cancer-specific survival. Acta Oncol.

63:343–350. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lyu G, Dai L, Deng X, Liu X, Guo Y, Zhang

Y, Wang X, Huang Y, Wu S, Guo JC and Liu Y: Integrative analysis of

cuproptosis-related mitochondrial depolarisation genes for

prognostic prediction in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cell Mol

Med. 29:e704382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang W, Lu K, Jiang X, Wei Q, Zhu L, Wang

X, Jin H and Feng L: Ferroptosis inducers enhanced cuproptosis

induced by copper ionophores in primary liver cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 42:1422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen L, Min J and Wang F: Copper

homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Faubert B, Li KY, Cai L, Hensley CT, Kim

J, Zacharias LG, Yang C, Do QN, Doucette S, Burguete D, et al:

Lactate metabolism in human lung tumors. Cell. 171:358–371. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

He Y, Ji Z, Gong Y, Fan L, Xu P, Chen X,

Miao J, Zhang K, Zhang W, Ma P, et al: Numb/Parkin-directed

mitochondrial fitness governs cancer cell fate via metabolic

regulation of histone lactylation. Cell Rep. 42:1120332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Elnaggar GN, El-Hifnawi NM, Ismail A,

Yahia M and Elshimy RAA: Micro RNA-148a targets Bcl-2 in patients

with non-small cell lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

22:1949–1955. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ran XM, Xiao H, Tang YX, Jin X, Tang X,

Zhang J, Li H, Li YK and Tang ZZ: The effect of

cuproptosis-relevant genes on the immune infiltration and

metabolism of gynecological oncology by multiply analysis and

experiments validation. Sci Rep. 13:194742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huang H, Shi Z, Li Y, Zhu G, Chen C, Zhang

Z, Shi R, Su L, Cao P, Pan Z, et al: Pyroptosis-related LncRNA

signatures correlate with lung adenocarcinoma prognosis. Front

Oncol. 12:8509432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wilkerson MD, Yin X, Walter V, Zhao N,

Cabanski CR, Hayward MC, Miller CR, Socinski MA, Parsons AM, Thorne

LB, et al: Differential pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma

subtypes involving sequence mutations, copy number, chromosomal

instability, and methylation. PLoS One. 7:e365302012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Okayama H, Kohno T, Ishii Y, Shimada Y,

Shiraishi K, Iwakawa R, Furuta K, Tsuta K, Shibata T, Yamamoto S,

et al: Identification of genes upregulated in ALK-positive and

EGFR/KRAS/ALK-negative lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res.

72:100–111. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schabath MB, Welsh EA, Fulp WJ, Chen L,

Teer JK, Thompson ZJ, Engel BE, Xie M, Berglund AE, Creelan BC, et

al: Differential association of STK11 and TP53 with KRAS

mutation-associated gene expression, proliferation and immune

surveillance in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 35:3209–3216. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhao W, Huang H, Zhao Z, Ding C, Jia C,

Wang Y, Wang G, Li Y, Liu H and Chen J: Identification of hypoxia

and mitochondrial-related gene signature and prediction of

prognostic model in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cancer. 15:4513–4526.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang Z, Zhang P, Xie J, Cui Y, Shuo W and

Yue D: Five-gene prognostic model based on autophagy-dependent cell

death for predicting prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep.

14:264492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang J, Zhang J, Zhang F, Lu S, Guo S,

Shi R, Zhai Y, Gao Y, Tao X, Jin Z, et al: Identification of a

disulfidptosis-related genes signature for prognostic implication

in lung adenocarcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 165:1074022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ritchie ME: limma: Linear models for

microarray and RNA-Seq data. The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing. 2024.

|

|

25

|

He Y, Jiang Z, Chen C and Wang X: