Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is an aggressive

neoplastic disease of the renal parenchyma that accounts for 2–3%

of all diagnosed cancer types (1,2). Among

these subtypes, clear-cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most frequent and is

characterized by intrinsic chemoresistance (3,4).

Overall, ccRCC is diagnosed late in up to 50% of patients, with a

median survival of 6–10 months (5,6).

In cancer, lymphocytes develop a hypofunctional

state known as immune exhaustion, in which cells exhibit increased

expression of immune checkpoints or exhaustion receptors.

Immunotherapy reverses this state of exhaustion by blocking the

interaction between checkpoints and their ligands, leading to the

activation of antitumor immunity (7,8). The

approved therapies for advanced RCC include tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (targeted therapy) and immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs). Currently, there are five ICIs approved for the treatment

of advanced RCC: i) Nivolumab and pembrolizumab, which target

programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) expressed on lymphocytes;

ii) ipilimumab, which targets cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated

protein-4 (CTLA-4) also expressed on lymphocytes; and iii)

atezolizumab or avelumab, which target the programmed death

ligand-1 (PD-L1) on cancer and stromal cells (9–12). In

cancer, the upregulation of ligands such as PD-L1 on stroma and

tumor cells have immunosuppressive effects on lymphocytes via

ligation of the inhibitory receptors CTLA-4 and PD-1. The use of

ICIs block these inhibitory signals, which restores the cytotoxic

function of infiltrating lymphocytes (7). However, the lack of consensus on

predictive tools for guiding the use of ICIs prevents their

widespread applicability, which is a notable issue considering the

cost-effectiveness and side effects associated with these therapies

(13,14).

Since localized disease can be successfully treated

with surgery, there is a lack of studies analyzing the expression

of markers such as PD-1, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 during the early stages

of the disease. To address this knowledge gap, the present study

aimed to evaluate the expression levels of ICI targets [PD-1,

PD-L1, CTLA-4, lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and T-cell

immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing-3 (TIM-3)] in blood and

tumors obtained from a small cohort of patients diagnosed with

localized ccRCC. The expression levels of these markers across

three tissues were compared: Blood and tumor tissue from patients

with ccRCC, and blood from a group of healthy controls.

Furthermore, the expression levels of the markers associated with

the nuclear grade in tumors and changes in blood after a short-term

follow-up of 12 months were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment

The present study included 20 patients diagnosed

with ccRCC who underwent elective localized nephrectomy (median

age, 62 years; range, 44–71 years) and 10 control subjects (median

age, 62 years; range, 55–72 years) who were considered healthy

based on medical history and did not have any prior diagnosis of

cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders or

current infections. Patients and controls were recruited from the

Service of Urology at the University Hospital ‘Dr José Eleuterio

González’ (Nuevo León, Mexico) between January 2022 and January

2024 (Table I). Patients were

excluded if they were diagnosed with metastatic disease or RCC

variants other than ccRCC. The present study was approved by the

Institutional Ethics Committee (approval no. IN23-00002) and all

participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Peripheral venous blood samples (4 ml) were obtained on the day

before the scheduled nephrectomy (n=20) and after 12 months of

clinical follow-up from a subgroup of patients who consented to

subsequent blood analysis (n=10). The clinical follow-up consisted

of a complete clinical evaluation by a urologist, including

radiologic studies to evaluate RCC relapse. Healthy controls were

sampled only at the beginning of the study (n=10). Furthermore,

after completing histopathological analysis, 2 g of tumor tissue

was sampled from the macroscopically defined tumor area in each

nephrectomized kidney. The histopathological analysis consisted of

RCC subtype diagnosis, pathological tumor staging (pTNM) according

to the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines (15), evaluation of tumor grade according

to the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading

system (16), presence of tumor

necrosis and identification of sarcomatoid or rhabdoid

differentiation.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of the

participants. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of the

participants.

| Variable | Control (n=10) | Patients

(n=20) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

| 0.139a |

|

Male | 4 (40) | 14 (70) |

|

|

Female | 6 (60) | 6 (30) |

|

| Age, years ±

SD | 60.8±6.0 | 59.4±8.0 | 0.610b |

| Tumor size, cm ±

SD | - | 8.2±3.9 | - |

| Necrosis <50%, n

(%) | - | 18 (90) | - |

| Nuclear grade, n

(%) |

|

|

|

| G2 | - | 6 (30) | - |

| G3 | - | 9 (45) | - |

| G4 | - | 5 (25) | - |

| T stage, n (%) |

|

|

|

| T1 | - | 6 (30) | - |

| T2 | - | 2 (10) | - |

| T3 | - | 10 (50) | - |

| T4 | - | 2 (10) | - |

Immunohistochemistry

All studied samples underwent a comprehensive

assessment for multifocality, necrosis and sarcomatoid features.

Representative sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues

were used for further analyses. Briefly, the tissues were fixed

with 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 h at room temperature.

After fixation, tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced to

obtain 4-µm-thick sections. Subsequently, the tissues were

rehydrated through a series of alcohol solutions, from absolute to

70% ethanol, finishing with distilled water. Since standard

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections do not require

permeabilization, this step was not performed. Immunostaining was

performed using the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit (cat. no.

760-700; Roche Tissue Diagnostics; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) and the

BenchMark ULTRA stainer module (cat. no. 05342716001; Roche Tissue

Diagnostics; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.). The OptiView detection kit

includes reagents for peroxidase inhibition, biotin-free

hapten-coupled secondary antibody and horseradish peroxidase

multimer coupled tertiary antibodies. Chromogenic reaction was

performed with the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB)

chromogen. Antigen retrieval was performed using Discovery CC1

solution (cat. no. 950-500; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) for 64 min at

100°C. The primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal

anti-CTLA-4 (cat. no. BSB 2880; clone BSB-88; Bio SB, Inc.), rabbit

monoclonal anti-PD-L1 (cat. no. 790-4905; clone SP263; Roche Tissue

Diagnostics; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) and rabbit monoclonal

anti-CD3 (cat. no. 790-4341; clone 2GV6; Roche Tissue Diagnostics;

Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) at a dilution of 1:50 for 32 min at 37°C.

The secondary reaction was performed using the OptiView DAB

Detection Kit for an additional 12 min at 37°C. All staining

procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol

to ensure consistency and reliability. Clinical analyses of all

samples were performed by three clinical pathologists using a

brightfield optical microscope (Olympus CX31; Olympus

Corporation).

The DP200 slide scanner (cat. no. 08303916001; Roche

Tissue Diagnostics; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) was used for

whole-slide scanning. Subsequently, a set of 8–10 randomly selected

images (magnification, ×40) were further analyzed using the QuPath

software for Windows (version 0.5.1) (17). Digital analyses were performed by a

trained non-pathologist (Fig. S1).

The percentage of positive cells was calculated using the following

formula: Percentage of positive cells=[number of positive

cells/(number of positive cells + number of negative cells)]

×100.

Flow cytometry

Cytometric analyses of blood samples were performed

on the day of nephrectomy (n=7-12) and after a 12-month clinical

follow-up (n=10). Some of the blood samples were lost during the

procedure due to a technical error, and only samples deemed

acceptable after quality control were included, defined as properly

anticoagulated blood and a viability >50% based on trypan blue

exclusion (n=7-12). For tissue analysis (n=18), the tumor was

mechanically and enzymatically digested in DMEM supplemented with

5% FBS (cat. no. F2442; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The enzyme

cocktail contained collagenase (cat. no. C9891; MilliporeSigma),

hyaluronidase (cat. no. H3506; MilliporeSigma), DNase (cat. no.

10104159001; Roche Diagnostics, Ltd.) and trypsin (cat. no.

15090-046; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with EGTA (cat.

no. E3889; MilliporeSigma). Furthermore, the tissues were incubated

with the protease dispase (cat. no. 17105041; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and BD FACS™ Lysing Solution (cat. no. 349202; BD

Biosciences) for 10 min at room temperature. After eliminating the

aggregates with a 70 µm cell strainer (cat. no. 352350; Falcon;

Corning Life Sciences), 1×106 cells were stained.

Complete blood samples (50 µl) were stained, followed by

erythrocyte lysis for 20 min. The antibody cocktail for lymphocytes

(CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes)

contained FITC mouse anti-human CD8 (20 µl/sample; cat. no. 555366;

clone RPA-T8), PE mouse anti-human CD279 (PD-1; 20 µl/sample; cat.

no 557946; clone MIH4), BV605 mouse anti-human CD4 (5 µl/sample;

cat. no. 562658; clone RPA-T4), APC-Cy™7 mouse anti-human CD3 (5

µl/sample; cat. no. 557832; clone SK7), Alexa Fluor® 647

mouse anti-human CD366 (TIM-3; 5 µl/sample; cat. no. 565558; clone

7D3), PE-CF594 mouse anti-human CD223 (LAG-3; 5 µl/sample; cat. no.

565718; clone T47-530) and BV421 mouse anti-human CD152 (CTLA-4; 5

µl/sample; cat. no. 562743; clone BNI3). The antibody cocktail for

myeloid cells (granulocytes and monocytes) contained Alexa

Fluor® 488 mouse anti-human CD14 (5 µl/sample; cat. no.

557700; clone M5E2), BV421 mouse anti-human CD274 (PD-L1; 5

µl/sample; cat. no. 563738; clone MIH1), PE mouse anti-human CD45

(5 µl/sample; cat. no. 561866; clone HI30) and 7-AAD viability

solution (5 µl/sample; cat. no. 559925). All antibodies were

acquired from BD Biosciences.

For each sample, 1×105 events were

acquired using an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and

Company) and analyzed with DIVA version 8.0 for Windows (BD

Biosciences). The percentages of CD4+ and

CD8+ cells were quantified relative to CD3+

cells. Similarly, the percentages of lymphocytes

(CD14−SSClo), monocytes

(CD14+SSClo) and granulocytes

(CD14−SSChi) were quantified relative to

CD45+ cells (Fig. S2).

PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 fluorescence was analyzed as

the mean fluorescence intensity (Fig.

S3).

Statistical analysis

After confirming the parametric distribution of the

data, an unpaired Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used for two- and

three-group comparisons, respectively. Fisher's exact test was used

to compare the sex proportions between patients and healthy

controls and between tumor grade categories (Grade 2 vs. Grade

>2). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism

(version 5.0; Dotmatics) for Windows and Microsoft Excel. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Clinical description of the

participants

Both groups of participants had similar ages and

comorbidities, such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and

obesity. The mean age ± SD of the participants was 59.4±8 years in

the patient group and 60.8±6 years in the healthy control group. A

total of 10 patients were classified as T3 on the pTNM staging

system and 14 patients had an ISUP nuclear grade ≥3. The average

tumor size was 8.2±3.9 cm (Table

I).

Immunohistochemistry reveals increased

infiltration of the tumor tissue by CD3+

lymphocytes

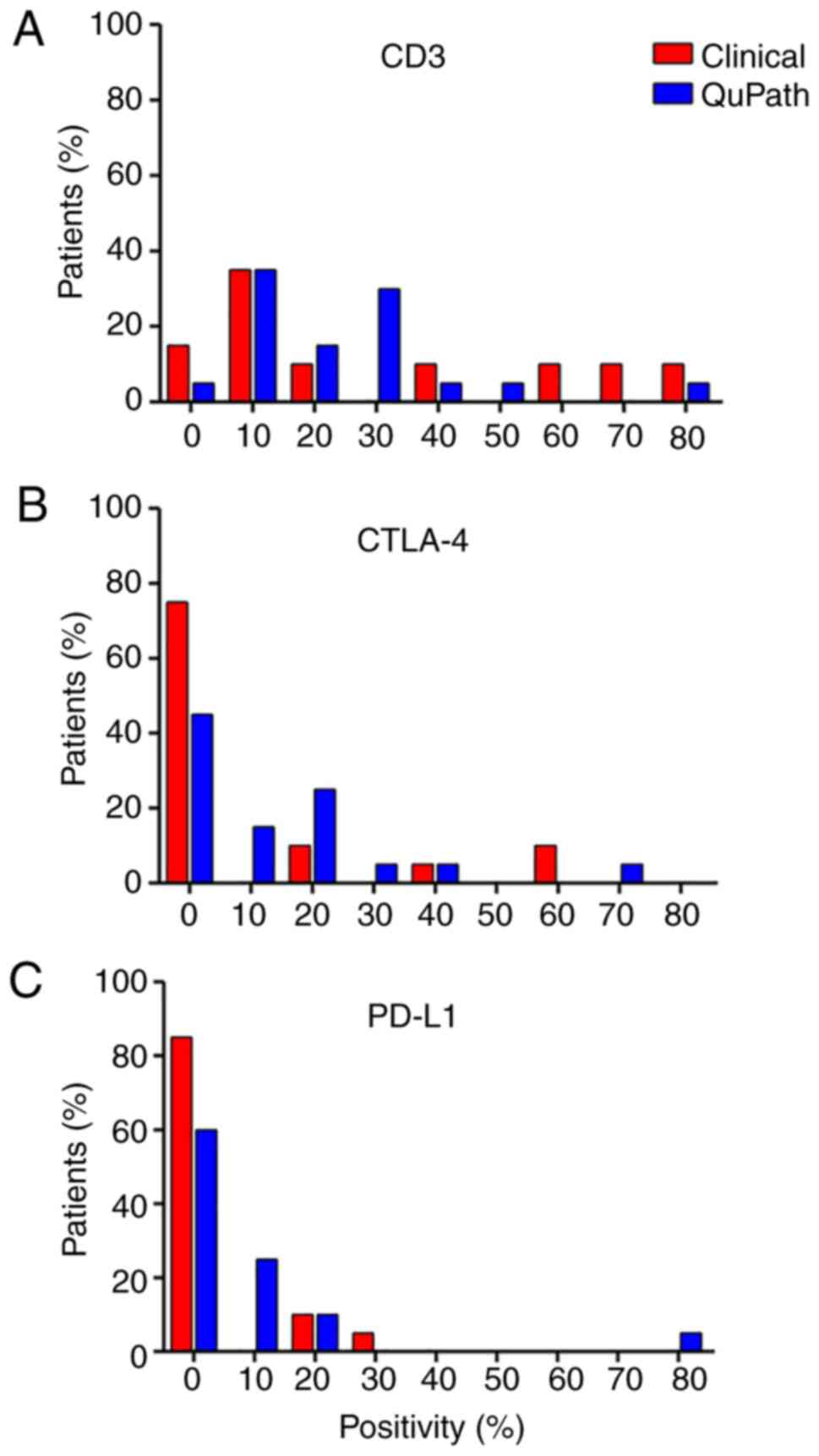

Serial sections from RCC tissue were stained for

CD3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 for immunohistochemical analysis. Positivity

was evaluated by both clinical pathologists and digital analysis of

micrographs using QuPath software (see Materials and methods;

Fig. S1). Of all the tumor

samples, >80% were positive for CD3 (Fig. 1A). By contrast, CTLA-4 (Fig. 1B) and PD-L1 (Fig. 1C) were positive in only 50 and 25%

of the samples, respectively. These findings demonstrate that ccRCC

tissue is highly infiltrated with lymphocytes and has low

expression of the exhaustion markers CTLA-4 and PD-L1.

CD8+ lymphocytes and

monocytes dominates the tissue cellularity among infiltrating

leukocytes

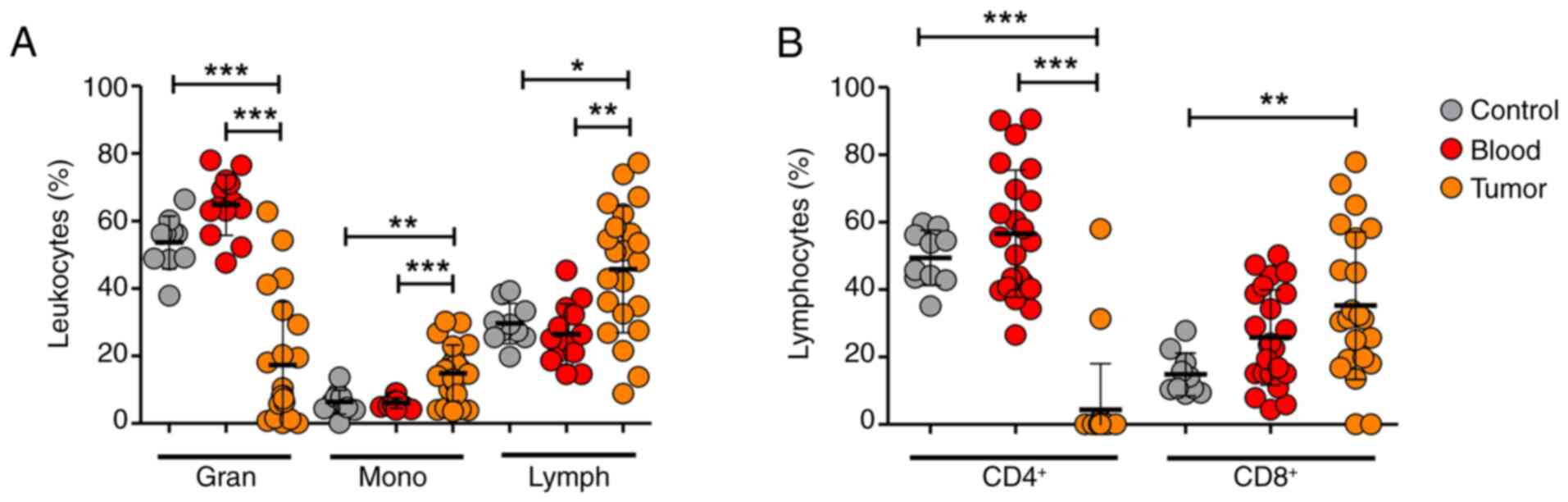

In addition to immunohistochemistry, flow cytometric

analysis of tumor tissue and peripheral blood was performed to

evaluate the changes in leukocyte dynamics (Figs. 2 and S2). The tumor tissue exhibited decreased

infiltration of granulocytes and increased infiltration of

monocytes and lymphocytes compared with the leukocyte percentages

in the blood (Figs. 2A and S2A, C and E). Among the lymphocyte

subpopulations, CD8+ lymphocytes were the dominant

subpopulation in the tumor tissue; notably, the percentage

CD4+ lymphocytes was markedly lower (Figs. 2B and S2B, D and F). There was a trend for

increased percentages of granulocytes and CD4+ and

CD8+ lymphocytes in blood from patients compared with

blood from healthy controls; however, the differences were not

statistically significant.

Tumor-infiltrating leukocytes

demonstrate decreased expression levels of the markers LAG-3,

TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1

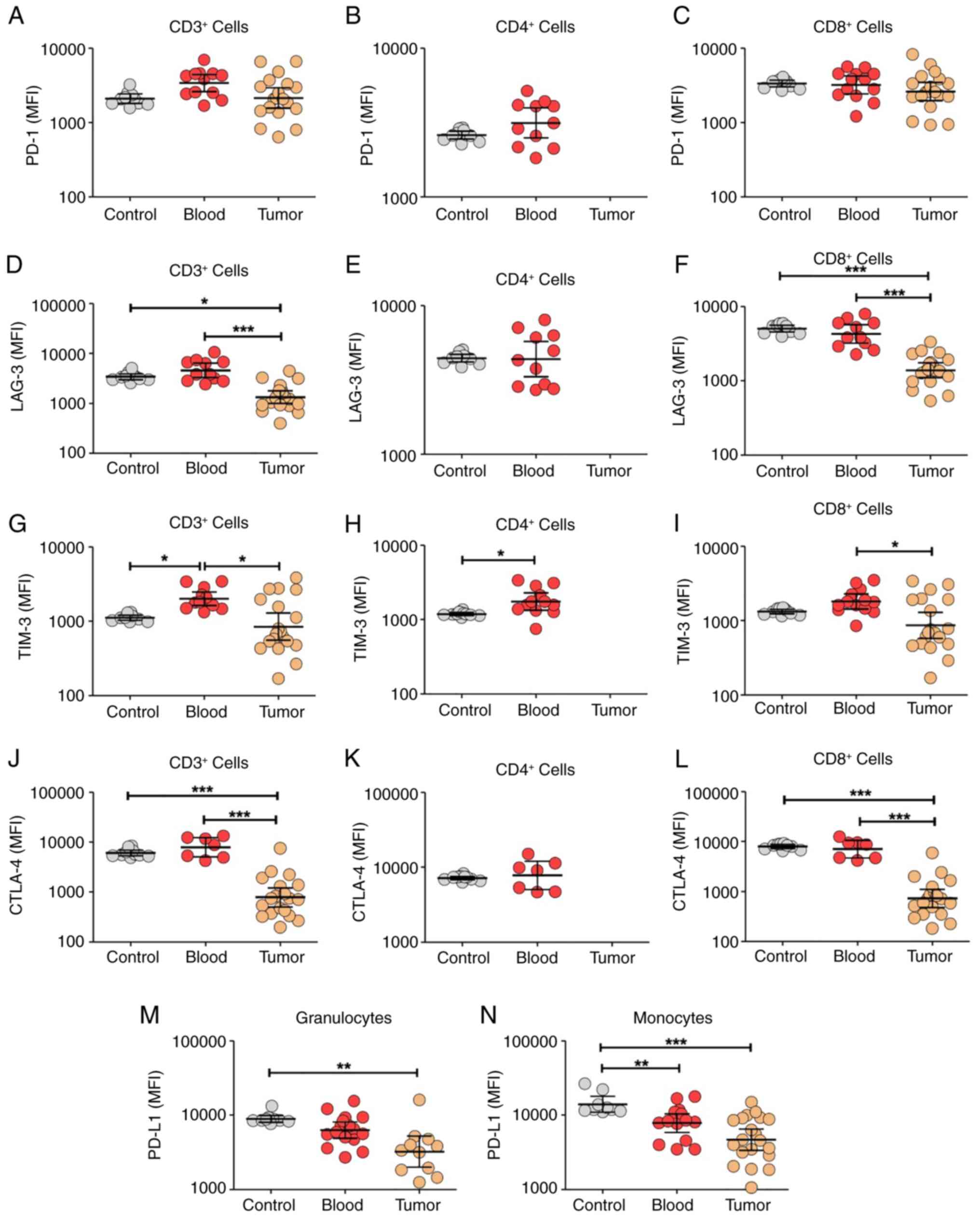

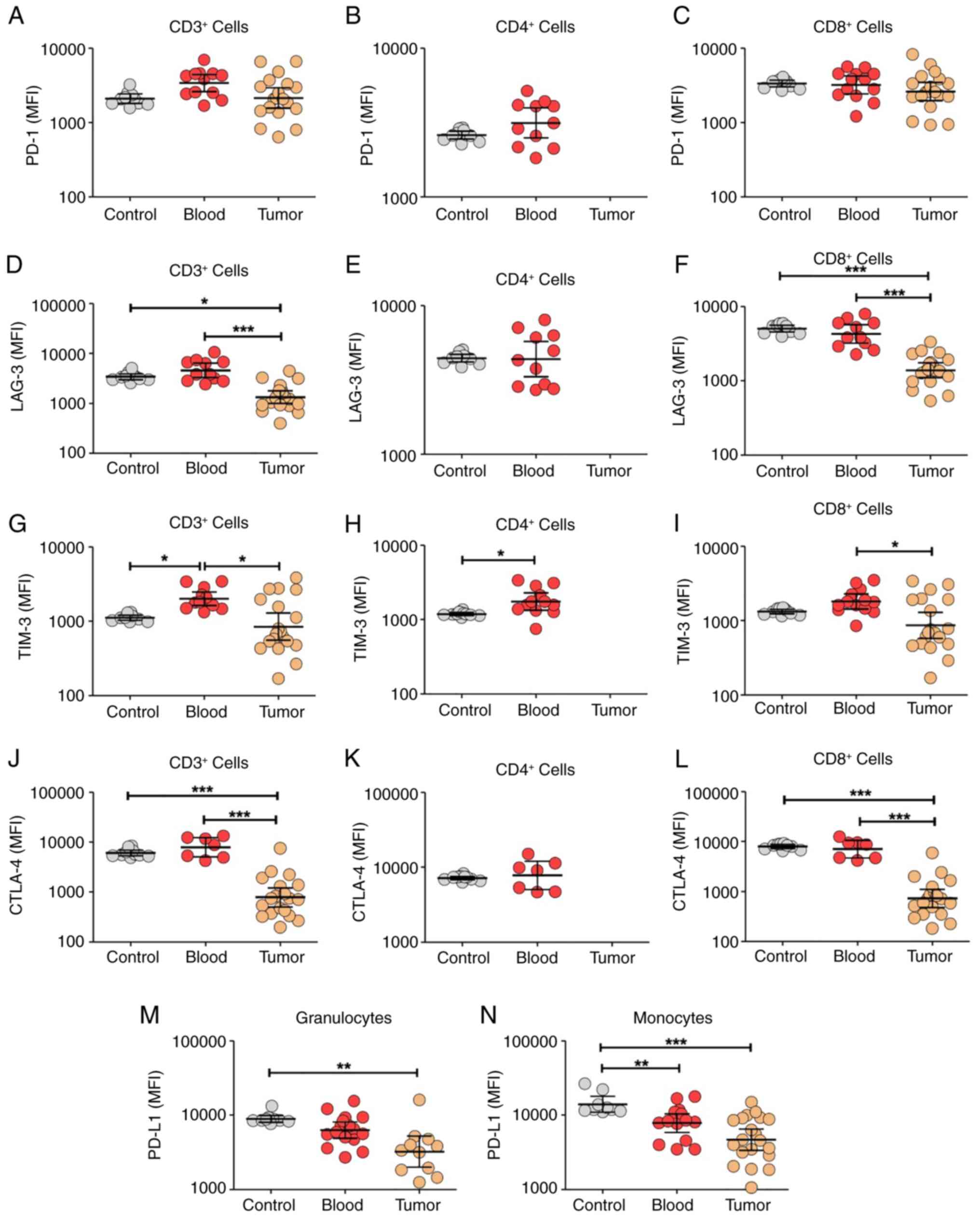

After assessing leukocyte dynamics, the expression

levels of several receptors associated with lymphocyte exhaustion

were evaluated, a principal mechanism involved in antitumor

immunity. Using flow cytometry, the expression levels of PD-1,

LAG-3, TIM-3 and CTLA-4 in lymphocytes, and PD-L1 receptors in

granulocytes and monocytes were evaluated (Figs. 3 and S3). There was no change in PD-1

expression (Figs. 3A-C and S3A) but decreased expression levels of

LAG-3 (Figs. 3D-F and S3B), TIM-3 (Figs. 3H-I and S3C) and CTLA-4 (Figs. 3J-L and S3D) among tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

were observed compared with blood samples. In addition, decreased

PD-L1 expression levels were reported in granulocytes (Fig. 3M) and monocytes (Figs. 3N and S3E) that infiltrated the tumor tissue

compared with the blood. Only two markers indicated expression

differences between the patient and healthy control blood samples.

The patients had increased TIM-3 levels (Fig. 3G) and decreased PD-L1 levels

(Fig. 3N) in lymphocytes and

monocytes, respectively. Collectively, the present study results

demonstrate decreased expression of several exhaustion-associated

markers within tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, with the notable

exception of PD-1.

| Figure 3.Compared with circulating leukocytes,

tumor-infiltrating leukocytes exhibit decreased expression of the

exhaustion receptors LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 based on flow

cytometry. All receptors were evaluated in blood leukocytes from

healthy controls (control), blood leukocytes from patients (blood)

and tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (tumor). PD-1 was evaluated in

(A) CD3+, (B) CD4+ and (C) CD8+

lymphocytes. LAG-3 was evaluated in (D) CD3+, (E)

CD4+ and (F) CD8+ lymphocytes. TIM-3 was

evaluated in (G) CD3+, (H) CD4+ and (I)

CD8+ lymphocytes. CTLA-4 was evaluated in (J)

CD3+, (K) CD4+ and (L) CD8+

lymphocytes. PD-L1 was evaluated in (M) granulocytes and (N)

monocytes. The tumor-infiltrating leukocytes exhibited decreased

expression levels of LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 compared with

blood leukocytes, but no changes were observed in PD-1 expression.

Data are expressed as MFI ± SD. Control group, n=10; blood group,

n=7-12; tumor group, n=18. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA

with Bonferroni's post hoc test (except panels B, E, H and K, which

were analyzed using an unpaired Student's t-test). *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PD-1,

programmed cell death protein-1; LAG-3, lymphocyte activation

gene-3; TIM-3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing

protein-3; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein-4;

MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. |

Patient stratification according to

nuclear grade indicates no differences in the expression of

exhaustion markers

To assess the clinical significance of quantifying

the exhaustion-associated markers, the differential expression of

these markers was evaluated according to the tumor nuclear grade

(Table II). No overall differences

in marker expression associated with nuclear grade were reported,

except for CD3 positivity based on immunohistochemistry.

Furthermore, the temporal changes in blood expression levels of the

tested markers were compared 12 months after therapeutic

nephrectomy (Table III). The only

change observed was an increase in CTLA-4 expression levels in

blood lymphocytes at 12 months compared with basal levels.

Collectively, ccRCC tissue exhibited increased proportions of

infiltrated CD3+ lymphocytes and monocytes compared with

the proportions in the blood (Figs.

1 and 2). Infiltrated

leukocytes showed decreased expression levels of the exhaustion

markers LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1, but not PD-1 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the variables did not

change after stratifying the patients according to nuclear grade

and between baseline and clinical follow-up (Tables II and III).

| Table II.Analysis of leukocyte markers

according to tumor grade G2-G4. |

Table II.

Analysis of leukocyte markers

according to tumor grade G2-G4.

| Variable | G2 (n=6) | G3 (n=9) | G4 (n=5) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.354 |

|

Male | 5 (83) | 5 (55) | 3 (60) |

|

|

Female | 1 (17) | 4 (45) | 2 (40) |

|

| Age, years ±

SD | 61.5±8.6 | 59.7±8.9 | 60.2±7.7 | 0.919 |

| Tumor size, cm ±

SD | 7.2±3.2 | 7.8±5.1 | 8.6±2.4 | 0.851 |

| Necrosis, % ±

SD | 16.7±17.2 | 15.5±19.8 | 22.5±14.7 | 0.744 |

| Positive tissue on

immunohistochemistry, % ± SD |

|

|

|

|

|

CD3 | 13.4±7.6 | 19.8±14.6 | 39.6±22.0 | 0.030 |

| CD3

(clinical) | 14.3±22.6 | 25.6±30.7 | 54.0±24.1 | 0.071 |

|

CTLA-4 | 14.9±25.7 | 13.1±14.7 | 9.4±10.0 | 0.876 |

| CTLA-4

(clinical) | 17.0±26.3 | 8.6±19.9 | 4.2±8.8 | 0.566 |

|

PD-L1 | 16.6±31.0 | 6.8±5.8 | 0.6±0.5 | 0.322 |

| PD-L1

(clinical) | 0.5±0.5 | 5.8±11.2 | 4.8±8.5 | 0.514 |

| Flow cytometry of

blood samples, MFI ± SD |

|

|

|

|

| PD-L1

granulocytes | 6,975±5,007 | 6,165±2,272 | 8,873±4,598 | 0.669 |

| PD-L1

monocytes | 5,486±3,618 | 9,543±5,709 | 9,414±2,200 | 0.356 |

| PD-1

CD3 | 475±158 | 925±577 | 2,357±2,451 | 0.134 |

| LAG-3

CD3 | 662±238 | 1,000±530 | 3,093±3,319 | 0.122 |

| TIM-3

CD3 | 552±288 | 775±336 | 1,309±840 | 0.130 |

| CTLA-4

CD3 | 692±226 | 1,166±724 | 4,285±5,624 | 0.181 |

| Flow cytometry of

tumor samples, MFI ± SD |

|

|

|

|

| PD-L1

granulocytes | 6,797±6,332 | 6,031±7,207 | 2,207±1,010 | 0.588 |

| PD-L1

monocytes | 3,032±1,059 | 7,944±3,871 | 29451±48,419 | 0.162 |

| PD-1

CD3 | 2,473±792 | 2,248±1,399 | 3,128±2,616 | 0.729 |

| LAG-3

CD3 | 1,301±294 | 1,488±930 | 1,452±768 | 0.927 |

| TIM-3

CD3 | 502±258 | 731±501 | 1,139±1,015 | 0.395 |

| CTLA-4

CD3 | 444±227 | 801±876 | 1,052±816 | 0.524 |

| Table III.Changes in leukocyte markers at 12

months follow-up using flow cytometry. |

Table III.

Changes in leukocyte markers at 12

months follow-up using flow cytometry.

| Variable | Basal (n=20) | 12 months

(n=10) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Granulocytes, % ±

SD | 34.2±32.9 | 45.4±21.4 | 0.320 |

| Monocytes, % ±

SD | 12.2±11.0 | 7.4±2.3 | 0.166 |

| Lymphocytes, % ±

SD | 48.3±25.7 | 42.0±21.4 | 0.497 |

| CD4+, %

± SD | 56.3±18.1 | 52.8±15.1 | 0.604 |

| CD8+, %

± SD | 24.6±13.8 | 18.1±9.2 | 0.197 |

| PD-L1, MFI ±

SD |

|

|

|

|

Monocytes | 6,135±3,916 | 6,807±4,716 | 0.674 |

|

Granulocytes | 15,867±27,880 | 4,951±3,556 | 0.232 |

| PD-1, MFI ± SD |

|

|

|

|

CD3+ | 2,320±1,821 | 3,160±1,967 | 0.260 |

|

CD4+ | 1,973±1,534 | 2,993±1,768 | 0.118 |

|

CD8+ | 2,570±1,499 | 3,041±1,779 | 0.457 |

| LAG-3, MFI ±

SD |

|

|

|

|

CD3+ | 3,043±2,802 | 1,771±1,208 | 0.185 |

|

CD4+ | 2,840±2,321 | 1,826±1,192 | 0.209 |

|

CD8+ | 2,805±2,272 | 1,464±968 | 0.088 |

| TIM-3, MFI ±

SD |

|

|

|

|

CD3+ | 1,358±805 | 1,263±817 | 0.766 |

|

CD4+ | 1,301±772 | 1,210±746 | 0.762 |

|

CD8+ | 1,317±744 | 1,193±786 | 0.680 |

| CTLA-4, MFI ±

SD |

|

|

|

|

CD3+ | 3,672±4,437 | 8,416±6,330 | 0.026 |

|

CD4+ | 3,902±4,297 | 8,539±6,102 | 0.024 |

|

CD8+ | 3,012±4,058 | 6,743±5,130 | 0.041 |

Discussion

RCC primarily affects patients aged 60 to 70 years

old (2). Among its variants, up to

80% of the diagnoses are associated with ccRCC, a severe disease

characterized by intrinsic aggressiveness, chemoresistance and poor

prognosis (3,6). In the early stages, ccRCC may be cured

through nephrectomy; however, advanced disease often requires

systemic and combined therapies such as immunotherapy and systemic

targeted therapy (5). These

treatments present challenges, particularly due to the lack of

validated tools for selecting patients based on their likelihood of

clinical response and the risk of adverse events (13,14).

The role of infiltrating leukocytes in prognosis and response to

treatment is not completely understood and depends on

characteristics such as the cell phenotype, tumor infiltration and

the cell exhaustion status (7). For

example, the increased infiltration of CD8+ and

CD68+ cells and decreased infiltration of

CD4+ cells predict a positive response to ICI treatment

(18). However, in general,

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are commonly associated with poor

prognosis (19). Particularly in

RCC, highly infiltrated tumors (also called hot tumors) are

associated with poor prognosis (20). Among exhaustion markers, the

increased expression of PD-L1 is found in ~6% of patients with RCC

and is commonly associated with poor outcomes (21). The relationship between systemic

inflammation and RCC prognosis has also been investigated,

revealing a negative association between these variables (22). For these reasons, the expression

levels of exhaustion receptors should be interpreted with caution

because, while increased levels of PD-L1 are commonly associated

with poor overall prognosis, the increased availability of these

ligands could be predictive of the success of ICI treatments

(23). There is a lack of

information regarding the temporal expression of molecular

immunotherapy targets among tumors and tumor stages, including

kidney tumors. To address this issue, the present study aimed to

characterize the expression of five common immunotherapy targets,

PD-1, PD-L1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and CTLA-4, in tissue and blood samples

obtained from a cohort of 20 patients with localized ccRCC, an

early stage of the disease. According to the literature, the 5-year

cancer-specific survival rates for stage I, II, III and IV patients

are 97.4, 89.9, 77.9 and 26.7%, respectively, and nephrectomy

improves the condition-specific survival, mostly in advanced tumors

(stages III and IV) (24).

The immunohistochemistry results of the present

study aligned with those of previous reports that characterize

ccRCC as a highly immunogenic tumor (25). The tumor tissue indicated increased

expression levels of CD3, but moderate-to-absent expression of

CTLA-4 and PD-L1. In the majority of cancer types, elevated CD3

expression is generally associated with a favorable prognosis and

response to systemic immunotherapy (26–29);

however, previous studies suggest the opposite for ccRCC, where

high infiltration of lymphocytes and increased expression of

exhaustion markers have been associated with poor overall prognosis

and unresponsiveness to immunotherapy (25,30,31).

The present study assessed the immunohistochemistry data using two

approaches: Clinical analysis by pathologists and digital analysis

using the QuPath software. From an objective point of view, digital

analysis would overcome the possibility of subjective or biased

analysis, although it is more complex and usually restricted to

research settings.

Following immunohistochemistry, the present study

adopted flow cytometry to evaluate the expression of biomarkers in

the blood and tissue samples. The integration of

immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry followed the rationale that

combined methods would enable a broader and more accurate

assessment of immune exhaustion compared with each method alone.

Flow cytometry was selected as a complementary technique to

immunohistochemistry due to its capacity for high-dimensional,

single-cell analysis, which allows for the precise quantification

of immune subsets and co-expression of exhaustion markers. In the

flow cytometry analysis, the present study evaluated the expression

of a set of biomarkers commonly associated with lymphocyte

exhaustion and targeted by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in

clinical oncology. The results demonstrated that the patients had a

distinct pattern of infiltrating leukocytes, predominantly

cytotoxic lymphocytes and monocytes. Evaluation of the tumor tissue

indicated the absence of CD4+ lymphocytes and a relative

increase in CD3+CD4−CD8− cells

(data not shown). A decrease in the number of infiltrating

CD4+ cells has been associated with poor prognosis in

patients with sarcoma and cervical carcinoma (32,33).

The relative increase in

CD3+CD4−CD8− cells and the

abundance of lipids within the tumor core suggest the presence of

natural killer T lymphocytes because such cells have intrinsic

capabilities to recognize lipidic antigens (34,35).

Furthermore, ccRCC has been associated with the presence of

circulating double-positive lymphocytes

(CD4+CD8+) and dysfunctional lymphocytes in

ex vivo assays (36–38). Other previous studies have also

proposed the use of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (39) and C-reactive protein serum levels

(40,41) as potential cost-effective biomarkers

for the prediction of immunotherapy response in advanced ccRCC.

After assessing lymphocyte kinetics, the present

study investigated the expression of exhaustion-associated markers

using flow cytometry. Among circulating leukocytes, patients had

increased TIM-3 expression levels in blood lymphocytes and

decreased PD-L1 expression levels in blood monocytes compared with

that of the control group. In tumors, unchanged expression levels

of PD-1 and decreased expression levels of LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and

PD-L1 were reported compared with those in the blood samples.

Similarly, PD-L1 expression levels decreased among infiltrating

monocytes and granulocytes. These results suggest that mild

leukocyte dysfunction is present in the localized stage of ccRCC,

but there is uncertainty about the implications of these findings

in the later response to ICIs in advanced disease, mostly because

the immune exhaustion phenomenon is highly dynamic. It is important

to highlight that immune exhaustion is a complex mechanism

involving multiple receptors and cell phenotypes (42–44).

For example, exhausted CD8+ cells promote tumor

progression, but exhausted T regulatory (Treg) lymphocytes inhibit

tumor progression (45). Treg

lymphocytes mediate immunosuppression in T cells and dendritic

cells by producing the regulatory cytokines interleukin-10 and

transforming growth factor-β (45).

Therefore, detailed and comprehensive studies addressing multiple

markers are warranted to predict immunotherapy responses. Increased

expression levels of TIM-3 in lymphocytes and decreased expression

levels of PD-L1 in monocytes have been associated with worse

outcomes in patients diagnosed with RCC (46,47).

To assess the clinical significance of biomarker

expression in patients with RCC, patients were stratified based on

nuclear grade, due to the well-established inverse association

between nuclear grade and clinical outcomes (31,48).

The present study results did not indicate changes in tissue

leukocyte dynamics and biomarker expression compared with nuclear

grade, except for an increased percentage of CD3 positivity in

grade 4 tumors (Table II). In the

same context, when evaluating the changes in blood biomarker

expression after 12 months of clinical follow-up, the present study

demonstrated that most markers were stable over time, with the

notable exception of CTLA-4 (Table

III). These results suggest that the expression of exhaustion

biomarkers in localized disease was not associated with the nuclear

grade staging and did not demonstrate variation in the short-term

follow-up of 12-months.

The overall results of the present study suggest

that localized ccRCC shows decreased expression levels of the

exhaustion receptors LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1, implying a

lack of biological support for an immune exhaustion state in this

stage of the disease. In the future, it will be necessary to

analyze an expanded set of markers (OX40, 4-1BB, TOX and

interleukin-10) and cell phenotypes (T regulatory lymphocytes,

myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages)

in localized and metastatic disease to shed light on the

progressive expression of such biomarkers in RCC.

The present study had several limitations, including

the small number of participants, which followed the exclusion of

samples with insufficient cell counts to ensure reliable results

and the short-term follow-up of patients, which complicates the

clinical significance of the findings. In addition, tissue samples

were compared with blood samples because obtaining healthy renal

tissue is challenging due to ethical and practical reasons.

However, the findings remain notable due to the clinical nature of

the present study, the combined use of immunohistochemistry and

flow cytometry, simultaneous analysis of tumor and blood samples

and homogeneous inclusion of patients with localized disease. In

the future, a prospective study is warranted to assess an extended

panel of biomarkers as prognostic and predictive tools to guide the

use of immunotherapy in patients with RCC.

ccRCC is highly infiltrated by lymphocytes and

patients demonstrate decreased expression levels of the exhaustion

biomarkers LAG-3, TIM-3, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 within infiltrating tumor

leukocytes compared with circulating leukocytes. These biomarkers

remain stable in the short term and are not associated with nuclear

grade staging, which suggest they have limited use as a prognostic

tool in localized ccRCC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Science and

Technology Council (CONACYT), México (grant no. 301133).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

on Figshare at the following URL: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Flow_cytometry_data_for_tissue_leukocytes_in_a_cohort_of_20_patients_with_clear_cells_renal_cell_carcinoma/26888827/1.

Authors' contributions

RGGa, MMT, AGG and MCSC conceptualized and designed

the present study. RGGa, MMT and NLL developed and devised the

methodology. MMT and RGGu supervised the present study. RGGa, AGG,

VMOJ and MAOM were involved in the clinical evaluation and

follow-up of patients. MMT and RGGa acquired and analyzed the data

for flow cytometry. JPFG, RGGa, RGGu and JHEJ were involved in the

immunohistochemistry analysis. RGGa, MAOM and MMT wrote the first

draft. MMT, MCSC, VMOJ and NLL revised and corrected the

manuscript. RGGa and MMT confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the institutional

ethics committee (approval no. IN23-00002). All patients provided

written informed consent before enrollment in the present

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Padala SA and Barsouk A, Thandra KC,

Saginala K, Mohammed A, Vakiti A, Rawla P and Barsouk A:

Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J Oncol. 11:79–87.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rose TL and Kim WY: Renal cell carcinoma:

A review. JAMA. 332:1001–1010. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Di S, Gong M, Lv J, Yang Q, Sun Y, Tian Y,

Qian C, Chen W, Zhou W, Dong K, et al: Glycolysis-related biomarker

TCIRG1 participates in the regulation of renal cell carcinoma

progression and tumor immune microenvironment by affecting aerobic

glycolysis and AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int.

23:1862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ma G, Wang Z, Liu J, Fu S, Zhang L, Zheng

D, Shang P and Yue Z: Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals

sophisticated metabolic alteration and identifies FMNL1 as a

prognostic marker in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer.

12:6563–6575. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R and

Van Poppel H: exploratory subgroup analyses of renal function and

overall survival in European organization for research and

treatment of cancer randomized trial of nephron-sparing surgery

versus radical nephrectomy. Eur Urol Focus. 3:599–605. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bahadoram S, Davoodi M, Hassanzadeh S,

Bahadoram M, Barahman M and Mafakher L: Renal cell carcinoma: An

overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. G Ital

Nefrol. 39:2022–vol3. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

González-Garza R, Gutiérrez-González A,

Salinas-Carmona M and Mejía-Torres M: Biomarkers for evaluating the

clinical response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell

carcinoma (Review). Oncol Rep. 52:1642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jiang X, Liu G, Li Y and Pan Y: Immune

checkpoint: The novel target for antitumor therapy. Genes Dis.

8:25–37. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Motzer RJ, Alyasova A, Ye D, Karpenko A,

Li H, Alekseev B, Xie L, Kurteva G, Kowalyszyn R, Karyakin O, et

al: Phase II trial of second-line everolimus in patients with

metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RECORD-4). Ann Oncol. 27:441–448.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF,

Frontera OA, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, Plimack ER, Barthélémy P,

Porta C, George S, et al: Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus

sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med.

378:1277–1290. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, Rini B,

Albiges L, Campbell MT, Venugopal B, Kollmannsberger C, Negrier S,

Uemura M, et al: Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for

advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 380:1103–1115. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rini BI, Powles T, Atkins MB, Escudier B,

McDermott DF, Suarez C, Bracarda S, Stadler WM, Donskov F, Lee JL,

et al: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients

with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma

(IMmotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised

controlled trial. Lancet. 393:2404–2415. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S,

Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, Das S, Beckermann KE, Ha L, et al: Fatal

toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. JAMA

Oncol. 4:1721–1728. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Saliby RM, Saad E, Kashima S, Schoenfeld

DA and Braun DA: Update on biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma.

American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 44:22024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Amin MB; American Joint Committee on

Cancer, : American Cancer Society: AJCC cancer staging manual,

Eight edition/editor-in-chief, Mahul B, Amin, MD, FCAP; Stephen B.

Edge, MD, FACS [and 16 others]; Donna M. Gress, RHIT, CTR-Technical

editor; Laura R. Meyer, CAPM-Managing editor. American Joint

Committee on Cancer, Springer; Chicago IL: 2017

|

|

16

|

Organisation mondiale de la santé, Centre

international de recherche sur le cancer, . Urinary and male

genital tumours. 5th ed. International agency for research on

cancer; Lyon: 2022

|

|

17

|

Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA,

Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, McQuaid S, Gray RT, Murray LJ,

Coleman HG, et al: QuPath: Open source software for digital

pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 7:168782017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kazama A, Bilim V, Tasaki M, Anraku T,

Kuroki H, Shirono Y, Murata M, Hiruma K and Tomita Y:

Tumor-infiltrating immune cell status predicts successful response

to immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep.

12:203862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu C, Cui Y, Liu J, Ma L, Xiong Y, Gong Y,

Zhao Y, Zhang X, Chen S, He Q, et al: Noninvasive evaluation of

tumor immune microenvironment in patients with clear cell renal

cell carcinoma using metabolic parameter from preoperative

2-[18F]FDG PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging.

48:4054–4066. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ohe C, Yoshida T, Ikeda J, Tsuzuki T,

Ohashi R, Ohsugi H, Atsumi N, Yamaka R, Saito R, Yasukochi Y, et

al: Histologic-based tumor-associated immune cells status in clear

cell renal cell carcinoma correlates with gene signatures related

to cancer immunity and clinical outcomes. Biomedicines. 10:3232022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Möller K, Fraune C, Blessin NC, Lennartz

M, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Lindhorst L, Dahlem R, Fisch M, Eichenauer

T, et al: Tumor cell PD-L1 expression is a strong predictor of

unfavorable prognosis in immune checkpoint therapy-naive clear cell

renal cell cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 53:2493–2503. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ozbek E, Besiroglu H, Ozer K, Horsanali MO

and Gorgel SN: Systemic immune inflammation index is a promising

non-invasive marker for the prognosis of the patients with

localized renal cell carcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 52:1455–1463.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kawashima A, Kanazawa T, Kidani Y, Yoshida

T, Hirata M, Nishida K, Nojima S, Yamamoto Y, Kato T, Hatano K, et

al: Tumour grade significantly correlates with total dysfunction of

tumour tissue-infiltrating lymphocytes in renal cell carcinoma. Sci

Rep. 10:62202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cheaib JG, Patel HD, Johnson MH, Gorin MA,

Haut ER, Canner JK, Allaf ME and Pierorazio PM: Stage-specific

conditional survival in renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy.

Urol Oncol. 38:6.e1–6.e7. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Giraldo NA, Becht E, Vano Y, Petitprez F,

Lacroix L, Validire P, Sanchez-Salas R, Ingels A, Oudard S, Moatti

A, et al: Tumor-Infiltrating and peripheral blood T-cell

immunophenotypes predict early relapse in localized clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 23:4416–4428. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jung M, Lee JA, Yoo SY, Bae JM, Kang GH

and Kim JH: Intratumoral spatial heterogeneity of

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is a significant factor for

precisely stratifying prognostic immune subgroups of microsatellite

instability-high colorectal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 35:2011–2022.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mei Z, Liu Y, Liu C, Cui A, Liang Z, Wang

G, Peng H, Cui L and Li C: Tumour-infiltrating inflammation and

prognosis in colorectal cancer: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 110:1595–1605. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tewari N, Zaitoun AM, Arora A, Madhusudan

S, Ilyas M and Lobo DN: The presence of tumour-associated

lymphocytes confers a good prognosis in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma: An immunohistochemical study of tissue microarrays.

BMC Cancer. 13:4362013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rathore AS, Kumar S, Konwar R, Makker A,

Negi MPS and Goel MM: CD3+, CD4+ & CD8+ tumour infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs) are predictors of favourable survival outcome in

infiltrating ductal carcinoma of breast. Indian J Med Res.

140:361–369. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kahlmeyer A, Stöhr CG, Hartmann A, Goebell

PJ, Wullich B, Wach S, Taubert H and Erlmeier F: Expression of PD-1

and CTLA-4 are negative prognostic markers in renal cell carcinoma.

J Clin Med. 8:7432019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kawakami F, Sircar K, Rodriguez-Canales J,

Fellman BM, Urbauer DL, Tamboli P, Tannir NM, Jonasch E, Wistuba

II, Wood CG and Karam JA: PD-L1 and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

status in patients with renal cell carcinoma and sarcomatoid

dedifferentiation. Cancer. 123:4823–4831. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bi Q, Liu Y, Yuan T, Wang H, Li B, Jiang

Y, Mo X, Lei Y, Xiao Y, Dong S, et al: Predicted CD4+ T cell

infiltration levels could indicate better overall survival in

sarcoma patients. J Int Med Res. 49:03000605209815392021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shah W, Yan X, Jing L, Zhou Y, Chen H and

Wang Y: A reversed CD4/CD8 ratio of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

and a high percentage of CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are

significantly associated with clinical outcome in squamous cell

carcinoma of the cervix. Cell Mol Immunol. 8:59–66. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Paul S, Chhatar S, Mishra A and Lal G:

Natural killer T cell activation increases iNOS+CD206- M1

macrophage and controls the growth of solid tumor. J Immunother

Cancer. 7:2082019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li J, Moresco P and Fearon DT:

Intratumoral NKT cell accumulation promotes antitumor immunity in

pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e24039171212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nishida K, Kawashima A, Kanazawa T, Kidani

Y, Yoshida T, Hirata M, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto Y, Sawada M, Kato R,

et al: Clinical importance of the expression of CD4+CD8+ T cells in

renal cell carcinoma. Int Immunol. 32:347–357. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Menard LC, Fischer P, Kakrecha B, Linsley

PS, Wambre E, Liu MC, Rust BJ, Lee D, Penhallow B, Orduno NM and

Nadler SG: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) tumors display large

expansion of double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ T cells with expression

of exhaustion markers. Front Immunol. 9:27282018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zelba H, Bedke J, Hennenlotter J, Mostböck

S, Zettl M, Zichner T, Chandran A, Stenzl A, Rammensee HG and

Gouttefangeas C: PD-1 and LAG-3 dominate checkpoint

receptor-mediated T-cell inhibition in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer

Immunol Res. 7:1891–1899. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Young M, Tapia JC, Szabados B, Jovaisaite

A, Jackson-Spence F, Nally E and Powles T: NLR outperforms low

hemoglobin and high platelet count as predictive and prognostic

biomarker in metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 22:1020722024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Fukuda H,

Tachibana H, Yoshida K, Iizuka J, Okumi M, Ishida H and Tanabe K:

Predictive impact of an early change in serum C-reactive protein

levels in nivolumab therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Urol Oncol. 38:526–532. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Noguchi G, Nakaigawa N, Umemoto S,

Kobayashi K, Shibata Y, Tsutsumi S, Yasui M, Ohtake S, Suzuki T,

Osaka K, et al: C-reactive protein at 1 month after treatment of

nivolumab as a predictive marker of efficacy in advanced renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 86:75–85. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wei F, Zhong S, Ma Z, Kong H, Medvec A,

Ahmed R, Freeman GJ, Krogsgaard M and Riley JL: Strength of PD-1

signaling differentially affects T-cell effector functions. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:E2480–E2489. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tsujikawa T, Kumar S, Borkar RN, Azimi V,

Thibault G, Chang YH, Balter A, Kawashima R, Choe G, Sauer D, et

al: Quantitative multiplex immunohistochemistry reveals

myeloid-inflamed tumor-immune complexity associated with poor

prognosis. Cell Rep. 19:203–217. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Pichler R, Siska PJ, Tymoszuk P, Martowicz

A, Untergasser G, Mayr R, Weber F, Seeber A, Kocher F, Barth DA, et

al: A chemokine network of T cell exhaustion and metabolic

reprogramming in renal cell carcinoma. Front Immunol.

14:10951952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Denize T, Jegede OA, Matar S, El Ahmar N,

West DJ, Walton E, Bagheri AS, Savla V, Laimon YN, Gupta S, et al:

PD-1 Expression on intratumoral regulatory T cells is associated

with lack of benefit from anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic

clear-cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res.

30:803–813. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cai C, Xu YF, Wu ZJ, Dong Q, Li MY, Olson

JC, Rabinowitz YM, Wang LH and Sun Y: Tim-3 expression represents

dysfunctional tumor infiltrating T cells in renal cell carcinoma.

World J Urol. 34:561–567. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yeong J, Zhao Z, Lim JCT, Li H, Thike AA,

Koh VCY, Teh BT, Kanesvaran R, Toh CK, Tan PH and Khor LY: PD-L1

expression is an unfavourable prognostic indicator in Asian renal

cell carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 73:463–469. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Warren AY and Harrison D: WHO/ISUP

classification, grading and pathological staging of renal cell

carcinoma: Standards and controversies. World J Urol. 36:1913–1926.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|