Introduction

According to recent global cancer statistics, lung

cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy,

accounting for ~2.3 million new cases annually (11.7%). Despite

this, it remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality,

responsible for an estimated 1.8 million deaths worldwide (18%)

(1). Tobacco smoking is well

established as the primary risk factor for lung cancer (2). However, additional contributors

include genetic susceptibility, environmental pollutants,

occupational exposures, socioeconomic status and biological sex

(3).

Although lung cancer continues to be associated with

a poor prognosis, the 5-year relative survival rate for all types

has improved significantly over the past four decades, increasing

from 10.7 to 19.8% (4). This

improvement is largely attributed to advances in diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies, including earlier detection, molecular

profiling, refined staging methods and enhanced treatment

approaches, such as surgery, radiotherapy, targeted therapies and

immunotherapy (5,6).

For cases deemed medically inoperable or for

patients those who decline surgery, stereotactic ablative

radiotherapy (SABR) has emerged as a highly effective alternative

(7,8). SABR is a non-invasive, image-guided

radiotherapy technique that delivers high-dose radiation with

sub-millimeter precision, allowing for maximal tumor control while

minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues (9). Clinical studies have demonstrated

excellent local control rates with SABR, reaching up to 98% at 3

years, and a favorable toxicity profile (10,11).

For inoperable peripherally located stage I lung

cancer, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) can result in

superior local control rates without increasing major toxicities

compared with standard radiotherapy (12). However, the two randomized phase 3

trials on patients with operable stage I NSCLC (STARS and ROSEL)

have closed early due to slow patient accrual. Chang et al

(13) assessed the overall survival

(OS) of patients treated with SBRT vs. surgery by pooling data from

the STARS trial [NCT00840749] and the ROSEL trial [NCT00687986].

The estimated 3-year OS was 95% [95% confidence interval (CI),

85–100%] in the SBRT group compared with 79% (95% CI, 64–97%) in

the surgery group; therefore, it was concluded that SBRT could be a

suitable option for operable patients with stage I NSCLC (13). However, due to the small sample size

and short-follow-up duration this analysis has notable limitations.

A subsequent revised STARS trial, which provided a larger sample

size of SBRT patients, along with a protocol-specified

propensity-matched prospectively registered cohort of patients who

underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical lobectomy with

mediastinal lymph node dissection (VATS L-MLND) (14). Long-term survival outcomes after

SABR were found to be non-inferior to those achieved with VATS

L-MLND in operable patients with stage IA NSCLC (14). Despite these promising results,

lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection remains the

standard of care for operable patients with operable early-stage

NSCLC (15).

According to the Californian Cancer Center registry

data, long-term survival analysis of untreated patients with stage

I NSCLC suggests that a large proportion patients die of lung

cancer specific reasons; the 5-year OS of untreated patients with

stage I NSCLC was 6% overall (16).

There are numerous factors affecting treatment outcomes after SBRT

in patients with NSCLC. Baine et al (17) investigated the role of histology on

post-SBRT treatment outcomes such as local, regional and distant

control; the multi-institutional analysis showed higher local,

regional and distant recurrence rates and worse OS in NSCLC

patients with squamous cell cancer after SBRT. The biologically

effective dose (BED) affects the efficacy and the OS of patients

with NSCLC treated with SBRT. Medium or medium to high BEDs have

been associated with improved OS compared with high or low BEDs

(18).

The assessment of frequency and severity of

comorbidities also serves a critical role in terms of treatment

outcomes after SBRT. In lung cancer, one of the most frequently

used comorbidity scores is the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)

(19,20). The CCI includes 19 different

diseases, each of which is weighted with scores ranging from 1 to 6

points according to the risk of long-term mortality (21).

For treatment planning, position emission tomography

(PET) computed tomography (CT) scans with a fludeoxyglucose-18

tracer (FDG) can predict stage I and stage II disease, as well as

the Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging (22,23)

(T- and N-status), among patients with NSCLC more effectively

compared with dedicated PET alone (24). Furthermore, FDG-PET-CT may to be a

suitable diagnostic tool for predicting the therapeutic outcomes of

patients with early-stage NSCLC treated with SBRT more accurately

(25).

The specific aim of the present study was to provide

data on the long-term (10-year) survival rates of patients with

NSCLC treated with SBRT in a real-world setting. Specifically, the

present study aimed to analyze clinical and treatment-related

prognostic factors including age, performance status, comorbidities

(CCI), BEDmean and gross tumor volume (GTV), as well as their

associations with OS. Using Cox regression models and Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis, the present study aimed to identify patient- and

tumor-related factors influencing long-term outcomes, evaluate the

prognostic impact of BEDmean and GTV and explore whether older

patients experience comparable or superior outcomes compared with

that of younger patients. The present analyses were conducted to

support clinical decision-making and individual risk stratification

in patients with early-stage NSCLC treated with SBRT outside of

randomized controlled trials.

Patients and methods

Data and material

Patient recruitment was conducted retrospectively

using the databases of the Department of Radiation Oncology at the

University Hospital Halle [Halle (Saale), Germany]. Patient data

were anonymized and retrieved from the hospital information system

ORBIS (version 03.20.02.01; Moody's Analytics, Inc.). Information

regarding diagnostic imaging and radiation treatment were obtained

from Centricity PACS (Cytiva) and from Elekta Mosaiq (version 2.84;

Elekta Instrument AB).

All patients (n=99) treated with SBRT between

January 2009 and December 2013, were considered. After the initial

screening process, further analysis focused on patients with NSCLC

with M0-status according to the TNM staging system. Prior to any

data collection, the present study was approved by the ethics

committee of the Medical Faculty of Martin Luther University

Halle-Wittenberg (ethics approval number 2025-006). A total of 64%

of patients were male and 36% were female. The median age was 72

years, with a range of 44 to 91 years. Inclusion criteria comprised

age >18 years, receipt of at least one SBRT treatment and

curative treatment intent. The last date of follow-up was October

11, 2024.

Patient characteristics were categorized in multiple

classifications for analysis. Sex was classified as male or female,

while performance status was assessed using the Karnofsky

performance status (KPS). The KPS is a widely used method of

assessing the functional status of patients with cancer. This scale

allows clinicians to quantify a patient's functional impairment,

facilitating comparisons of therapeutic effectiveness and

prognostic assessments (26). Lower

KPS scores correlate with decreased survival rates across various

serious illnesses, including cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), congestive heart failure and advanced neurological

disorders, such as stroke or dementia (27). In the present study, KPS scores were

dichotomized into >70% (indicating superior physical condition)

and ≤70% (indicating poorer condition). T-status was grouped into

T1, T2, T3, T4 and unknown stage based on the TNM staging system;

nodal involvement (N-status) was categorized as N0 (no nodal

involvement), N1, N2 or unknown. The Union for International Cancer

Control (UICC) stage was recorded as stage I, II, III or unknown

stage according to the 7th edition of the UICC classification

(23).

Histological grading was documented as either known

or unknown, while tumor histology was categorized into

adenocarcinoma, large cell lung carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma,

not otherwise specified (NOS) or unknown histology. PET-based

treatment was recorded as performed or not performed. Radiation

dose was reported as single dose (such as 7, 8 and 12.5 Gy) and

number of fractions delivered. Furthermore, treatment regimens and

prescription isodoses were recorded.

COPD is a common comorbidity in patients with lung

cancer and is classified into four grades based on the severity of

airflow limitation, as defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic

Obstructive Lung Disease (28).

These grades are determined using spirometry, specifically

assessing the post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume (FEV) in

a 1-sec duration (FEV1), as a percentage of the

predicted value. Grade I (mild) is characterized by an

FEV1 ≥80% of the predicted value. Symptoms may include

chronic cough and sputum production, but airflow limitation is

mild. Grade II (moderate) corresponds to an FEV1 between

50–79% of the predicted value. Patients typically experience

shortness of breath on exertion, along with cough and sputum

production. Grade III (severe) includes an FEV1 between

30–49% of the predicted value, often accompanied by significant

shortness of breath, reduced exercise capacity, fatigue and

frequent exacerbations. Grade IV (very severe) is defined as a

FEV1 <30% of the predicted value or <50% with

chronic respiratory failure. Grade IV diseases is associated with

severe airflow limitation, a significant decline in quality of life

and life-threatening exacerbations (29).

For analysis, COPD status of each patient was

categorized into COPD unspecified, COPD I, COPD II, COPD II–III,

COPD III, COPD IV or unknown status. Overall comorbidities were

evaluated using the CCI and the age adjusted CCI. The CCI is a

widely used tool to estimate the prognosis and 10-year survival of

patients based on their comorbidities. Table I provides an overview of CCI

estimation based on different comorbidities and their weight in the

score (21).

| Table I.Charlson comorbidity index

calculation chart. |

Table I.

Charlson comorbidity index

calculation chart.

| Comorbidity | Weight | Criteria |

|---|

| Myocardial

infarction | 1 | History of

myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease |

| Congestive heart

failure | 1 | History of heart

failure |

| Peripheral vascular

disease | 1 | Claudication,

peripheral artery disease or previous vascular surgery |

| Cerebrovascular

disease | 1 | Stroke, transient

ischemic attack or history of cerebral hemorrhage |

| Dementia | 1 | Clinical diagnosis

of dementia |

| Chronic pulmonary

disease | 1 | Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease or asthma |

| Connective tissue

disease | 1 | Rheumatoid

arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Peptic ulcer

disease | 1 | History of gastric

or duodenal ulcer |

| Mild liver

disease | 1 | Chronic liver

disease without liver failure (for example, cirrhosis without

ascites) |

| Diabetes without

complications | 1 | Diabetes mellitus

without end-organ damage |

| Diabetes with

complications | 2 | Diabetes with

end-organ damage, such as retinopathy or nephropathy |

| Hemiplegia or

paraplegia | 2 | Paralysis due to

stroke, spinal cord injury or other causes |

| Moderate or severe

renal disease | 2 | Chronic kidney

disease with creatinine >3 mg/dL or dialysis-dependent |

| Cancer

(non-metastatic, active treatment) | 2 | Any solid tumor

without metastasis, currently treated |

| Leukemia | 2 | Chronic or acute

leukemia |

| Lymphoma | 2 | Non-Hodgkin's or

Hodgkin's lymphoma |

| Moderate or severe

liver disease | 3 | Cirrhosis with

complications (ascites, encephalopathy) |

| Metastatic solid

tumor | 6 | Any solid tumor

with metastasis |

| HIV/AIDS | 6 | HIV infection with

AIDS or opportunistic infections |

The age-adjusted CCI incorporates the age of the

patient to provide a more refined assessment of prognosis. In this

approach, one additional point is added to the total CCI score for

each decade of life starting from 50 years of age. For example,

patients aged 50 to 59 years receive one additional point, those

aged 60 to 69 years receive two points, those aged 70 to 79 years

receive three points and patients aged ≥80 years receive four

points. This adjustment reflects the increasing risk of mortality

associated with aging, independent of the presence or severity of

comorbid conditions (21,30). By accounting for age, the

age-adjusted CCI provides a more accurate prediction of outcomes,

particularly in older populations where age serves a significant

role in overall health and survival (30). In the present study, CCI was used to

evaluate the burden of comorbidities in the patient population. The

CCI was analyzed in two forms: The original version (without age

adjustment) and the age-adjusted version. The CCI without

age-adjustment was categorized into 3 groups: Low comorbidity

(<4), moderate comorbidity (4–5) and

high comorbidity (>5). The age-adjusted CCI was further

stratified into 4 groups: Very low (<3), low (3–5),

moderate (6–8) and high (>8).

Stereotactic radiation treatment

Treatment plans were carried out in accordance with

the national recommendations in place at the time of data

collection. The equipment consisted of a ‘Light Speed RT’ (GE

Healthcare) for scanning the patient geometry, the ‘Oncentra Master

Plan’ treatment planning system (Elekta Instrument AB) and two

linear accelerators (‘MXE’ and ‘Primus’; Siemens Healthineers),

each equipped with a collimator offering 1-cm leaf width in the

center part (measured at isocenter distance) and a portal imaging

system for position verification.

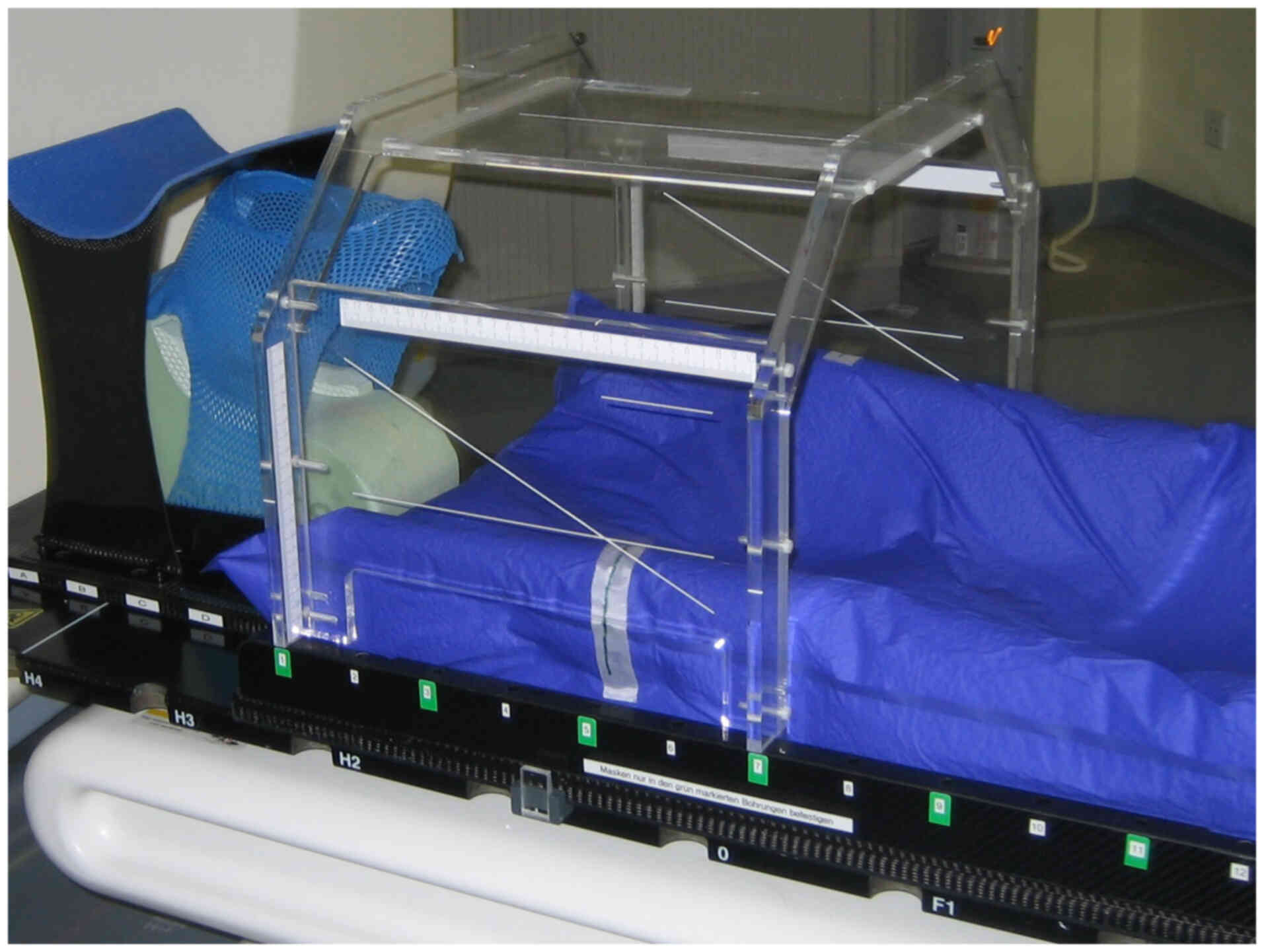

Patients were immobilized by means of a vacuum

mattress on a stereotactic board to which a stereotactic frame

(acrylic box) was attached (Fig.

1). A radiopaque coordinate system embedded in the acrylic

glass was used for patient alignment under the treatment machine.

Several CT series were collected with a slice thickness of 2.5 mm

using different scan techniques to visualize the tumor's movement

during a breathing cycle. Target volume was defined as this

movement space enlarged by 5 mm in all directions to account for

overall geometrical uncertainties of the treatment chain. Dose was

calculated using the ‘collapsed cone algorithm’ on the ‘slow’ CT

series. This series was scanned with a gantry rotation time of 4

sec and therefore displayed an averaged anatomy during ~1 breathing

cycle.

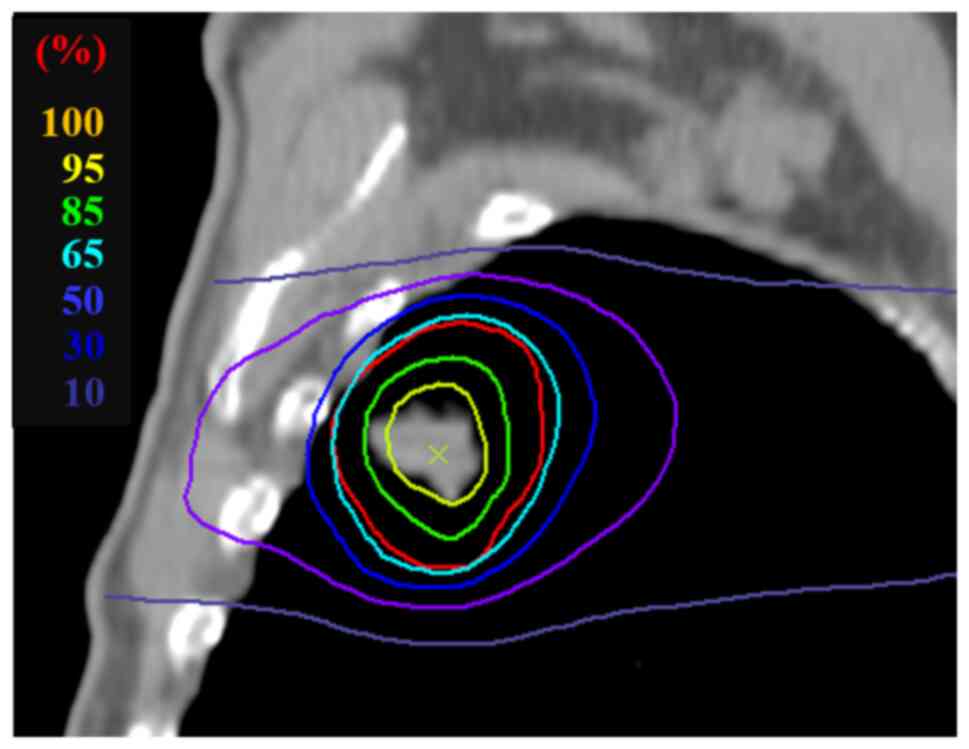

Dose was prescribed in 1 to 6 fractions onto the 65%

isodose enclosing the target volume, with the dose rising steeply

to a maximum of 100% in the center of the target (Fig. 2). All treatment plans consisted of

6–13 fixed beams of 6 MV acceleration potential and were created

using 3D-conformal technique with the beam isocenter in the center

of the tumor. Prior to each irradiation session, a control CT

examination (slow series) of the movement space of the tumor was

taken in which the center coordinates of the tumor, as documented

in the treatment plan, were localized relative to the origin of the

stereotactic frame. The beam isocenter of the treatment device was

then set to that location and orthogonal MV images were taken.

Finally, these images were compared with the respective digitally

reconstructed radiographs from the treatment planning system to

verify correct patient position. Patients were irradiated daily,

unless if three fractions were applied. Those patients were

irradiated every other day.

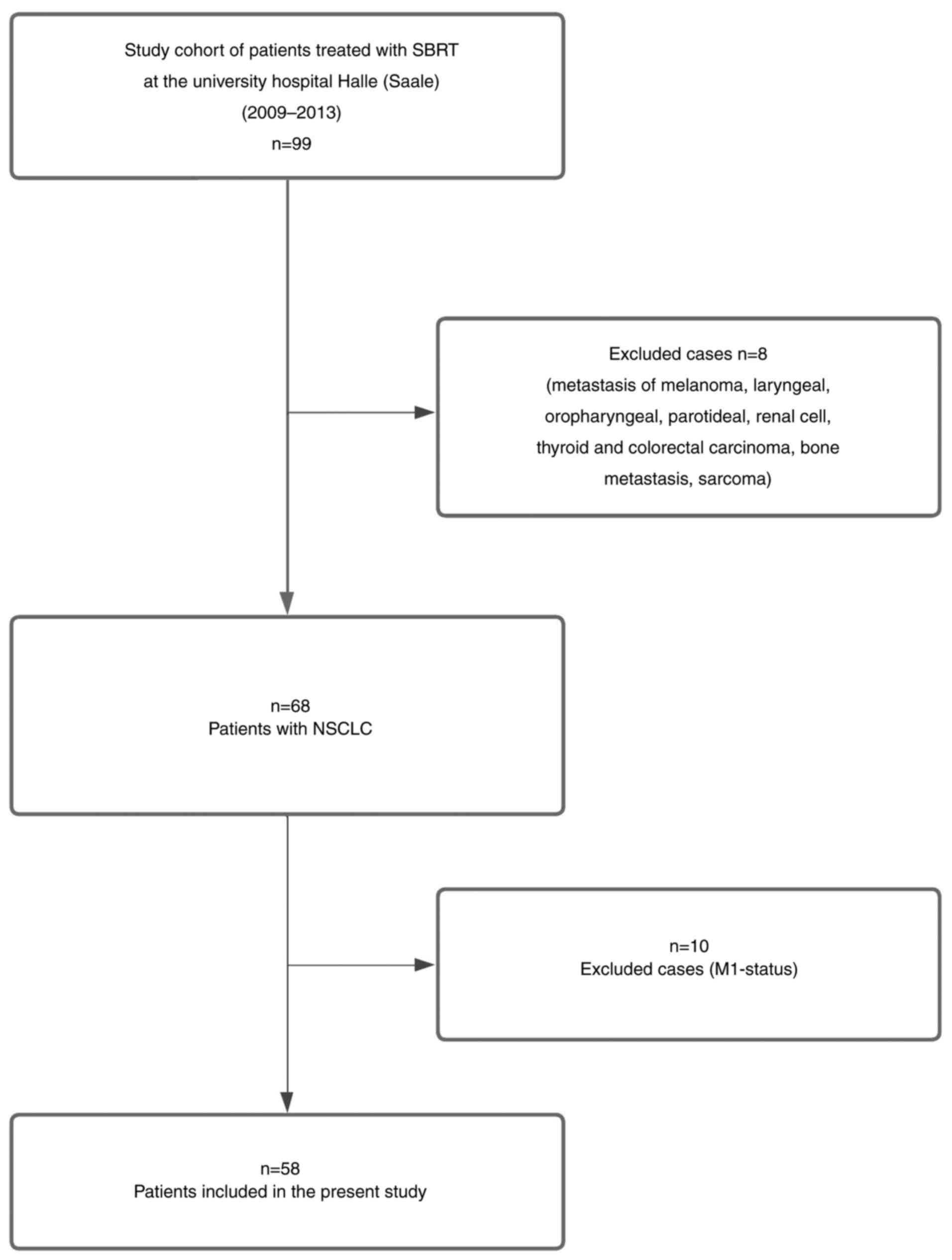

Calculation of biologically equivalent

dose

The varying effectiveness of the different dose

concepts can be partially explained by the use of a biologically

equivalent dose BED according to the linear quadratic model

(31):

Where n, d and α⁄β are the number of treatment

sessions, their dose and the characteristic parameter of the linear

quadratic model, which is inversely proportional to the repair

capacity of the tissue under consideration, respectively (1). As per previous research for the

stereotactic irradiation of lung tumors (32) the arithmetic mean was calculated

from the prescription BEDmin and the isocenter

BEDmax with α/β=10 Gy:

In the present study, the BED is given in units of

Gy10 in order to visualize the numerical value of α⁄β

used in the calculation. GTV was defined based on the radiotherapy

planning CT acquired prior to the start of SBRT.

Statistical analyses

Proportional hazard Cox regression models were used

to assess the association of cancer-related parameters with OS and

computed hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). In

the univariate analysis, each clinical factor was evaluated

individually. All significant predictors, as well as CCI and KPS,

from the univariate models were subsequently considered in a

multivariate analysis.

To identify the best-fitting model, a stepwise

variable selection approach was applied (both forward inclusion and

backward elimination) based on the Akaike Information Criterion

(33). The final multivariable

model was derived from this stepwise selection procedure. The

primary endpoint of the analysis was OS, defined as the time

interval between the end of radiotherapy and either death or the

last known follow-up as documented in the local citizen

registration.

Survival curves were generated using the

Kaplan-Meier method to analyze cumulative patient survival.

Differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Cut-off values for both BEDmean and GTV were defined as

the thresholds that provided the best separation in OS, as

determined by the log-rank test. To assess the robustness of the

findings in the presence of missing data, a sensitivity analysis

using five imputations was performed. All statistical analyses were

conducted using RStudio (version 2024.04.2+764; Posit Software,

PBC).

Results

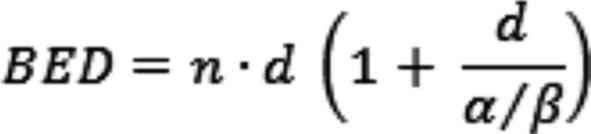

Case selection

The present retrospective study cohort was initially

comprised of 99 patients who were treated with SBRT at the

radiation oncology department of the University Hospital Halle

(Saale) between 2009 and 2013. However, 31 patients that were

treated for lung or bone metastasis caused by various primary

tumors (such as melanoma, laryngeal, oropharyngeal, parotid, renal

cell, thyroid, colorectal carcinoma or sarcoma) were excluded. The

remaining 68 patients were diagnosed with lung cancer.

Subsequently, 10 of these 68 patients were excluded due to

M1-status, resulting in a final cohort of 58 patients with

M0-status that were included in the present analysis (Fig. 3).

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of all patients with

lung cancer are presented in Table

II, stratified by age groups (<75 and ≥75 years). Among

patients aged <75 years (n=28) and ≥75 years (n=30), the

proportion of females was comparable (32 vs. 33%), with the

majority of patients in both groups being male (68 vs. 67%). A

higher KPS (>70%) was observed more frequently among older

patients (53 vs. 29%), whereas lower KPS (≤70%) occurred more often

in the younger group (71 vs. 47%).

| Table II.Baseline patient characteristics

(n=58)a. |

Table II.

Baseline patient characteristics

(n=58)a.

| Characteristic | Total, n (%) | Patients aged

<75 years, n (%) | Patients aged ≥75

years, n (%) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

Female | 19 (33) | 9 (32) | 10 (33) |

|

Male | 39 (67) | 19 (68) | 20 (67) |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

<75 | 28 (48) |

|

|

|

≥75 | 30 (52) |

|

|

|

Karnofsky-performance-status, % |

|

|

|

|

>70 | 24 (41) | 8 (29) | 16 (53) |

|

≤70 | 34 (59) | 20 (71) | 14 (47) |

| T-status |

|

|

|

| 1 | 26 (45) | 12 (43) | 14 (47) |

| 2 | 19 (33) | 7 (25) | 12 (40) |

| 3 | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| 4 | 3 (5) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) |

|

Unknown | 8 (14) | 5 (18) | 3 (10) |

| N-status |

|

|

|

| 0 | 43 (74) | 18 (64) | 25 (83) |

| 1 | 2 (3) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 4 (7) | 3 (11) | 1 (3) |

|

Unknown | 9 (16) | 5 (18) | 4 (13) |

| UICC-stage |

|

|

|

| I | 37 (64) | 16 (57) | 21 (70) |

| II | 8 (14) | 4 (14) | 4 (13) |

|

III | 4 (7) | 3 (11) | 1 (3) |

|

Unknown | 9 (16) | 5 (18) | 4 (13) |

| Grading |

|

|

|

|

Known | 16 (28) | 7 (25) | 9 (30) |

|

Unknown | 42 (72) | 21 (75) | 21 (70) |

| PET-based

treatment |

|

|

|

| No | 15 (26) | 9 (32) | 6 (20) |

|

Yes | 41 (71) | 18 (64) | 23 (77) |

|

Unknown | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Histology |

|

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma | 16 (28) | 7 (25) | 9 (30) |

| Large

cell lung carcinoma | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Not

otherwise specified | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma | 23 (40) | 13 (46) | 10 (33) |

|

Unknown | 15 (26) | 7 (25) | 8 (27) |

| COPD |

|

|

|

| COPD

unspecified | 11 (19) | 4 (14) | 7 (23) |

| COPD

I | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| COPD

II | 8 (14) | 6 (21) | 2 (7) |

| COPD

II–III | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| COPD

III | 4 (7) | 1 (4) | 3 (10) |

| COPD

IV | 11 (19) | 10 (36) | 1 (3) |

|

Unknown | 22 (38) | 7 (25) | 15 (50) |

| CCI without age

adjustment |

|

|

|

|

<3 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

|

>8 | 10 (17) | 4 (14) | 6 (20) |

|

3-5 | 11 (19) | 9 (32) | 2 (7) |

|

6-8 | 36 (62) | 14 (50) | 22 (73) |

| CCI

age-adjusted |

|

|

|

|

<3 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

|

3-5 | 11 (19) | 9 (32) | 2 (7) |

|

6-8 | 36 (62) | 14 (50) | 22 (73) |

|

>8 | 10 (17) | 4 (14) | 6 (20) |

| Treatment regimen

(prescription isodose); BEDmean/Gy10 |

|

|

|

| 37.5

Gy/3 fr. (65%); 126.51 Gy10 | 29 (60) | 12 (52) | 17 (68) |

| 40 Gy/4

fr. (65%); 118.11 Gy10 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| 28 Gy/4

fr. (65%); 68.53 Gy10 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| 32 Gy/4

fr. (65%); 83.71 Gy10 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| 36 Gy/4

fr. (65%); 100.24 Gy10 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| 50 Gy/5

fr. (80%); 120.31 Gy10 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| 48 Gy/6

fr. (65%); 125.57 Gy10 | 14 (29) | 7 (30) | 7 (28) |

T1 tumors were the most common in both groups (43

vs. 47%), while T2 tumors were slightly more frequent among older

patients (25 vs. 40%). T3 and T4 stages were rare in both groups.

Unknown T-status was more common in the <75 years group (17 vs.

10%). Regarding nodal status, most patients were N0, particularly

in the older group (83 vs. 64%). N1 and N2 involvement was observed

only in younger patients (N1: 7%; N2: 11%), while N-status remained

unknown in 18 and 14% of the <75 and ≥75 groups,

respectively.

UICC stage I was the most frequent stage in both age

groups (57 vs. 70%). Stage II and III cases were similarly

distributed, and unknown stage was slightly more frequent in the

younger group (18 vs. 14%). Histological grading was unknown in the

majority of patients in both age groups, slightly more so in

younger patients (75 vs. 70%).

A PET-based treatment approach was used more often

in older patients (77 vs. 64%). Squamous cell carcinoma was the

most frequent histological subtype (46 vs. 33%), followed by

adenocarcinoma (25 vs. 30%). Large cell lung carcinoma occurred

only in the younger group (4%). Tumors NOS were found exclusively

in older patients (10%).

Regarding comorbidities, COPD IV was substantially

more frequent in younger patients (36 vs. 3%), while unspecified

COPD was more frequent in the older group (23 vs. 14%). The

proportion of patients with unknown COPD status was higher among

older patients (51 vs. 25%). Age-adjusted CCI values were higher in

the ≥75 years group: 73% had a score of 6–8 and 20% had a score of

>8, compared with 50 and 14% in the <75 years group,

respectively.

The most commonly prescribed treatment regimen was

37.5 Gy in 3 fractions (52 vs. 68%), followed by 48 Gy in 6

fractions (32 vs. 28%). Most patients received a mean biological

effective dose (BEDmean) of 126.51 Gy10 (50%). The

second most frequent BEDmean was 125.57 Gy10,

administered in 24% of patients. All other regimens (e.g., 118.11,

120.31, 100.24, 83.71 and 68.53 Gy10) accounted for

<5% of patients.

Survival analysis

For OS, the 3-, 5- and 10-year OS rate was 35.09,

24.56 and 8.77%, respectively. The overall median survival of all

patients without metastasis was 32 months (95% CI, 10–35 months).

Median survival estimates for the respective patient subgroups are

summarized in Table SI.

The results of the univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analyses are summarized in Table III. Although the CCI and KPS

showed a statistically significant but weak correlation (Pearson's

r=0.29; P=0.029), both variables were retained in the univariate

Cox regression analyses. This decision was based on clinical

reasoning, as comorbid burden and performance status represent

distinct yet complementary aspects of the general health of a

patient and may independently influence survival. Furthermore,

considering their relevance within different age groups, their

inclusion allows for a more nuanced assessment of age-related

heterogeneity in the prognosis of patients with non-metastatic

NSCLC.

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate

Cox-regression models. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate

Cox-regression models.

|

| Univariate Cox

model | Multivariate

stepwise model |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.025 |

|

| 0.057 |

|

<75 | - | - |

| - | - |

|

|

≥75 | 0.54 | 0.31–0.92 |

| 0.55 | 0.30–1.01 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female | - | - |

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 1.12 | 0.64–1.97 | 0.762 |

|

|

|

| CCI |

|

| 0.654 |

|

|

|

|

<4 | - | - |

|

|

|

|

|

4-5 | 1.36 | 0.73–2.53 |

|

|

|

|

|

>5 | 1.11 | 0.53–2.30 |

|

|

|

|

| Karnofsky

performance status, % |

|

| 0.311 |

|

|

|

|

>70 | - | - |

|

|

|

|

|

≤70 | 1.33 | 0.77–2.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

BEDmean/Gy10 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.257 |

|

|

|

| GTV | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.041 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.024 |

In the univariate analysis, age ≥75 years was

significantly associated with decreased OS (HR, 0.54; 95% CI,

0.31–0.92; P=0.025). However, age ≥75 years was not statistically

significant in the multivariate stepwise model (HR, 0.55; 95% CI,

0.30–1.01; P=0.057), although a similar trend was observed. Sex

(male vs. female) was not significantly associated with OS in the

univariate analysis (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.64–1.97; P=0.7) and was

not selected for the multivariate stepwise model.

The CCI did not show a significant association with

survival in either the univariate analysis or the stepwise model

(P=0.6). When compared with patients with a CCI <4, those with

scores of 4–5 (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.73–2.53) and >5 (HR, 1.11;

95% CI, 0.53–2.30) did not differ significantly in mortality risk.

The KPS (≤70 vs. >70%) was also not significantly associated

with survival (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.77–2.30; P=0.3) and was excluded

from the multivariate stepwise model. The mean BED

(BEDmean/Gy10) showed no significant association with

survival in the univariate analysis (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.00;

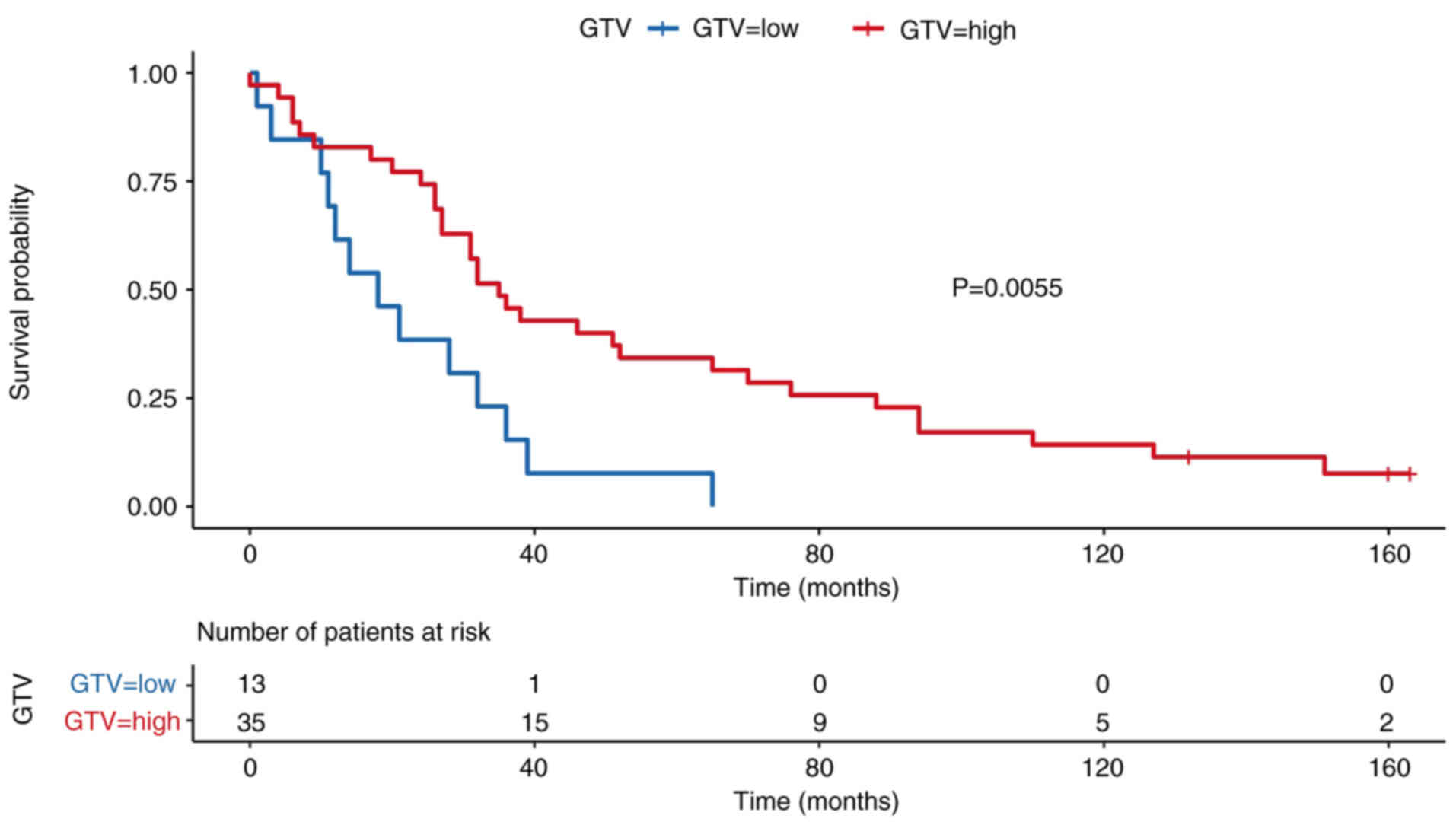

P=0.2) and was not retained in the multivariate model. The GTV was

significantly associated with survival in both the univariate (HR,

1.01; 95% CI, 1.00–1.02; P=0.041) and multivariate (HR, 1.01; 95%

CI, 1.00–1.02; P=0.024) analyses. This indicates that larger tumor

volumes were independently associated with increased mortality

risk.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

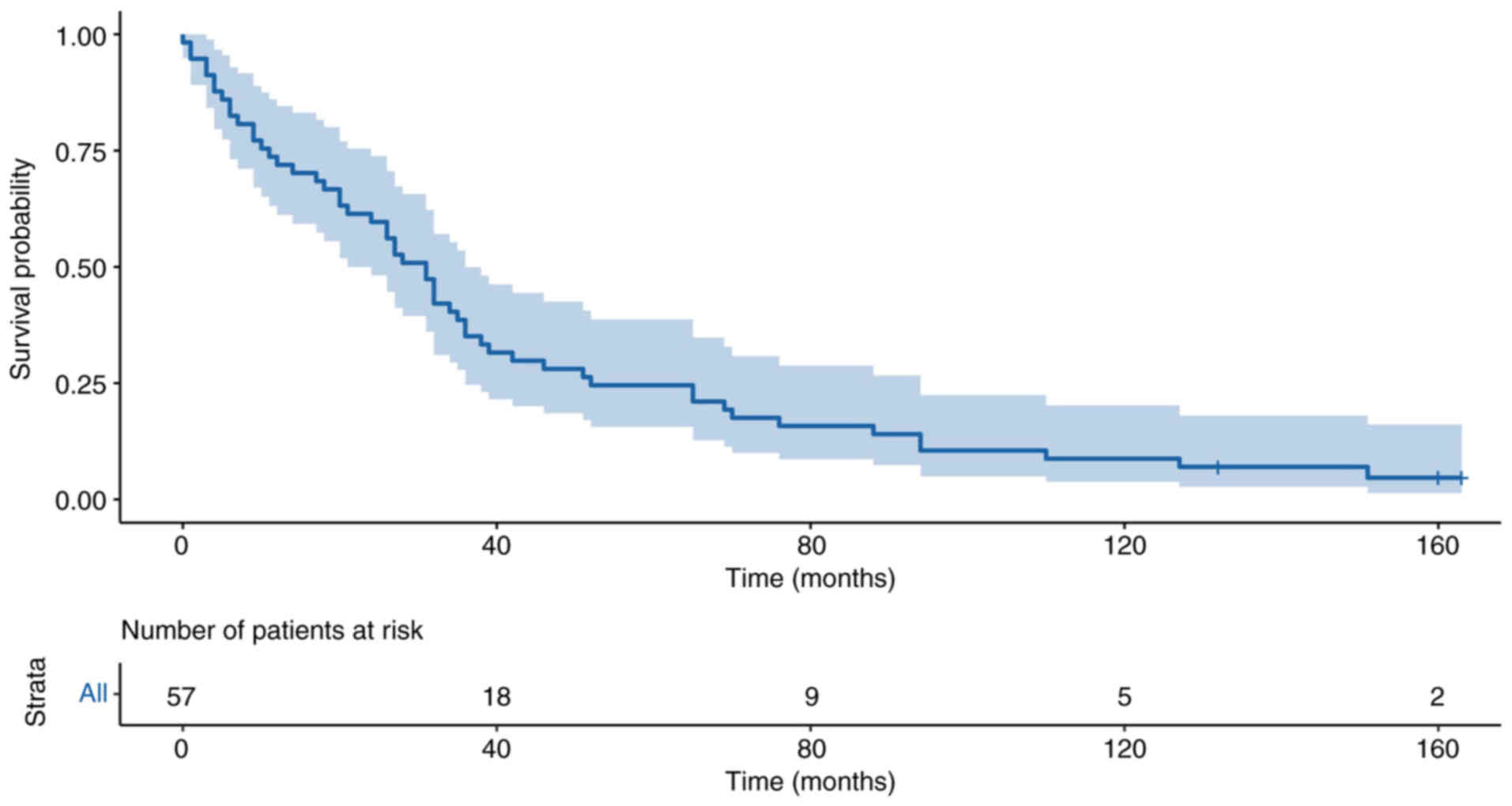

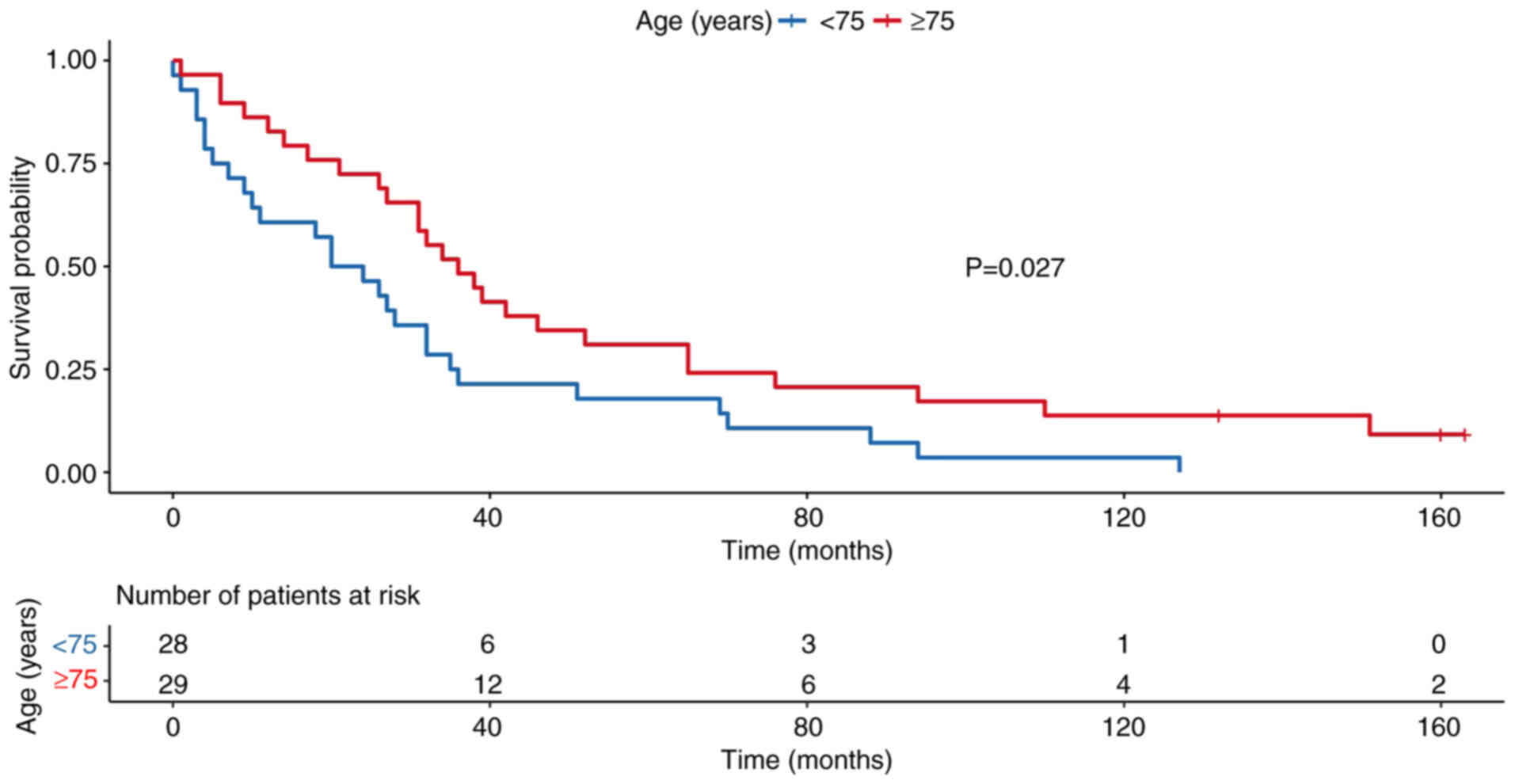

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to

illustrate OS in the present study cohort and stratified subgroups.

The survival curve for the total cohort up to 10 years (120 months)

is displayed in Fig. 4. OS was

stratified by age group (<75 vs. ≥75 years), which demonstrated

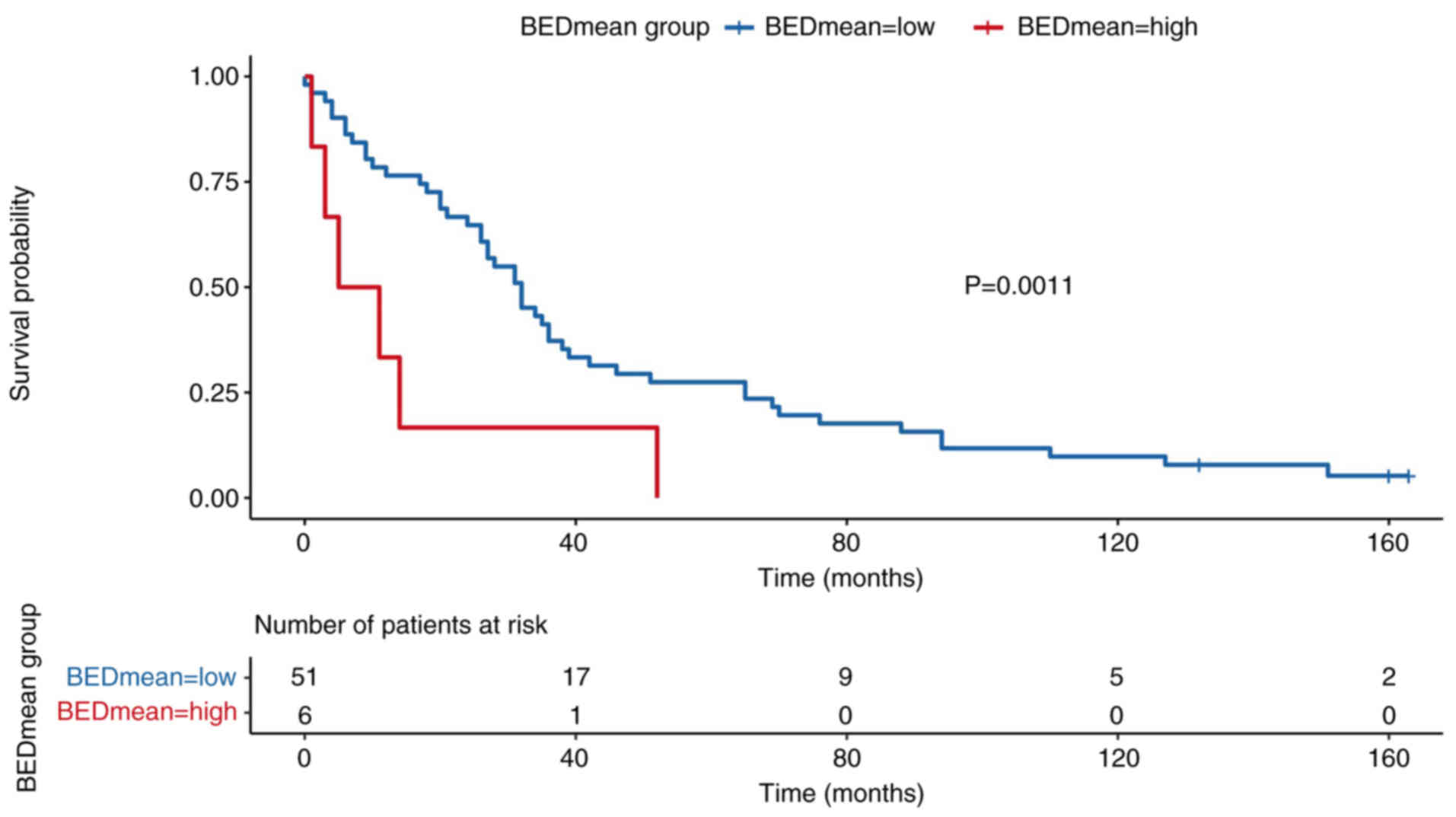

significantly reduced survival in older patients (P=0.023; Fig. 5). Survival rates were also analyzed

stratified according to BEDmean, using a cut-off of 120.31

Gy10 (Fig. 6). Patients

with high BEDmean demonstrated significantly improved survival

rates compared with those with lower doses (P=0.011). Survival was

stratified by GTV, using a cut-off of 25.6 cm3 (Fig. 7). Patients with larger tumor volumes

had significantly poorer survival outcomes (P=0.006).

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of the Cox regression

results, a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputations was

conducted and compared with the univariate and multivariate

stepwise model based on complete-case analysis. The pooled results

from the imputed datasets were compared with the complete case

analysis. The consistency of effect estimates between both models

supported the validity of the present conclusions. Overall, the

effect estimates were consistent between the imputed and stepwise

models. The variable age ≥75 years remained significantly

associated with improved survival across both approaches

(univariate imputed, HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.29–0.88; P=0.016;

multivariate stepwise, HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.29–0.85; P=0.012). Sex,

CCI and KPS did not show any significant associations in either

model.

Volume GTV remained significantly associated with

worse survival in both the univariate imputed (HR, 1.01; 95% CI,

1.00–1.02; P=0.007) and multivariate stepwise model (HR, 1.01; 95%

CI, 1.00–1.02, P<0.001). BEDmean also showed improved survival

in the imputed model (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.00; P=0.14), but

this was not statistically significant. Taken together, the

sensitivity analysis supported the robustness of the aforementioned

findings, particularly regarding age and GTV, and further

validation of the multivariate model despite missing data (Table IV).

| Table IV.Sensitivity analysis using multiple

imputation. |

Table IV.

Sensitivity analysis using multiple

imputation.

|

| Univariate Cox

model (multiple imputation) | Multivariate

stepwise model |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<75 | - | - |

| - | - |

|

|

≥75 | 0.50 | 0.29–0.88 | 0.016 | 0.49 | 0.29–0.85 | 0.012 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female | - | - |

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 1.03 | 0.58–1.83 | >0.924 |

|

|

|

| CCI | 1.05 | 0.87–1.25 | 0.671 |

|

|

|

| Karnofsky

performance status | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.542 |

|

|

|

|

BEDmean/Gy10 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.141 |

|

|

|

| GTV | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.007 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to analyze

data on the long-term (10-year) OS of patients with NSCLC treated

with SBRT in a real-world setting. To the best of our knowledge

there have only been a few analyses that have provided 10-year

follow-up data of patients treated with SBRT (34–37).

The working group ‘Extracranial Stereotactic

Radiotherapy’ of the German Society for Radiation Oncology

previously investigated the efficacy and safety of SBRT based on a

retrospective multicentric analysis (38). Data of 582 NSCLC patients treated

with SBRT at 13 institutions between 1998 and 2011 were

retrospectively analyzed. The BED was the most significant factor

associated with freedom from local progression (FFLP) and OS;

3-year FFLP and OS were 92.5 and 62.2%, respectively (38). In the present dataset, the 3-year OS

was lower (35.09%) compared with the of the aforementioned working

group study. However, the analysis by Guckenberger et al

(38) exclusively included patients

with stage I NSCLC. By contrast, the present cohort comprised 64%

patients with stage I NSCLC. Additionally, the baseline KPS in the

SBRT working group cohort was 80%, whereas in the present dataset,

59% of patients with NSCLC had a KPS of ≤70%. Therefore, the

observed difference in 3-year OS may be attributed to the poorer

clinical performance status of the present cohort and the inclusion

of patients with NSCLC with more advanced UICC stages.

In contrast to previously published findings

(39), BEDmean did not remain a

significant predictor of OS in the multivariate analysis (P=0.2),

despite being associated with survival in univariate Cox regression

(HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.00; P=0.2) and showing a significant

difference in Kaplan-Meier analysis (P=0.011). These inconsistent

findings may reflect the complex interplay between dose, tumor

volume and patient frailty (40,41).

However, the current literature specifically addressing the use of

SBRT in elderly patients, particularly with respect to survival

outcomes, is scarce. This gap in the literature highlights the

relevance of the present study and supports the need for further

research in this underrepresented patient subgroup. Furthermore,

the sensitivity analysis using multiple imputations demonstrated

that the BEDmean only had a non-significant trend toward improved

survival (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.00; P=0.14). This suggested that

while BED remains a key dosimetry parameter, its prognostic impact

on OS may be diminished in heterogeneous, comorbidity-burdened

patient populations such as in the present study. In a Chinese

retrospective multicenter analysis from 2023 analyzing a total of

145 early-stage NSCLC patients treated with SBRT, the 5-year local

recurrence rate was 5.1% and progression-free survival (PFS) rates

at 3- and 5-years were 69.2 and 60.5%, respectively. The

corresponding OS rates were 78.1 and 70.1% (42).

In the present analysis, older age was associated

with a survival benefit compared with younger patients in the

univariate Cox regression (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.31–0.92; P=0.025),

although this association did not remain statistically significant

in the multivariate model (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.30–1.01; P=0.057).

This finding may be explained by notable differences in baseline

characteristics between the two age groups. In the younger cohort

(<75 years), 71% of patients had a KPS of ≤70%, 48% were

diagnosed with COPD stage IV and 64% had an age-adjusted CCI score

of ≥6. By contrast, older patients (≥75 years) were more frequently

characterized by higher performance status and less severe COPD

staging. Given that SBRT is typically offered to patients deemed

medically inoperable, it could be considered that younger patients

in the present cohort were selected for SBRT only when significant

comorbidities or poor functional status precluded surgical

treatment. This selection bias may have contributed to the

unexpected survival disadvantage in the younger subgroup.

Similar to the analysis by Guckenberger et al

(38) real-world outcomes of SBRT

treatment in inoperable patients with stage I NSCLC were reported

from a Japanese cohort (42). In

this retrospective study, 399 patients with a median age of 75

years were analyzed (43). The

overall 3-year survival rate in this cohort was 77%, which was even

higher compared with the 3-year survival rate reported by

Guckenberger et al (38).

Most of these patients had optimal performance status scores (n=237

had an ECOG score of 0) and no pulmonary comorbidities (n=255 had

no emphysema; n=292 had no pulmonary interstitial changes), which

is in contrast to 31% of the patients in the present study who had

COPD grade IV.

Kreinbrink et al (40) investigated the safety and efficacy

of SBRT in patients ≥80 years with early-stage NSCLC, and it

reported that the median survival was 29.1 months. In comparison,

the overall median survival in the present analysis was slightly

higher at 32 months (95% CI, 10–35 months). However, the shorter

survival observed in their cohort could be attributed to a worse

median Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status

of 2 (range, 0–3) and an increased median age of 83 years. By

contrast, only 52% of patients in the present dataset was ≥75

years. Overall, Kreinbrink et al (40) reported high efficacy and low

toxicity rates in a cohort of elderly, inoperable patients with

NSCLC.

A large proportion of patients in the current study

presented with high T-stages (T3-statge, 4.0%; T4-stage, 6%) and N+

status, which may be explained by several factors. In interpreting

the present findings, it is important to acknowledge the potential

variability in T- and N-staging within the cohort, particularly

given the retrospective nature of the study and the heterogeneity

of available documentation. In certain cases, multiple tumor

lesions within the ipsilateral lung may have contributed to a

higher T-stage classification. Additionally, centrally located

tumors could have raised diagnostic uncertainty regarding the

involvement of hilar lymph nodes. In such instances, the

distinction between direct tumor invasion and true nodal metastasis

may have been unclear, potentially leading to an N+ classification

despite the absence of pathological confirmation. These

considerations highlight the inherent limitations of retrospective

staging assessments and underline the need for cautious

interpretation of TN-stage-based survival outcomes in this context.

Such diagnostic challenges, particularly in borderline cases, may

have potentially influenced staging decisions.

Prior studies have shown the superiority of CCI

compared with individual comorbid conditions in the prediction of

survival (19,20,30).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are only few analyses

available using CCI as predictor for survival in a cohort of

patients treated with SBRT (44–46).

Baker et al (46)

investigated the role of CCI and the cumulative illness rating

scale (CIRS) as prognostic factors for death within 6 months after

SBRT; it was reported that CIRS and tumor diameter were more

accurate predictors in terms of early-mortality in early-stage lung

cancer after SBRT (46). A

subsequent trial performed by Eriguchi et al (47) retrospectively analyzed operable

stage I NSCLC treated with SBRT, staged as cT1-2N0M0. The median

follow-up after SBRT was 40 months and in their multivariate

regression analysis, age and CCI were found to be significantly

associated with OS (47). By

contrast, the present analysis did not find a significant

association between CCI and OS. Patients with a CCI score of 4–5

had a hazard ratio of 1.36 (95% CI, 0.73–2.53) and those with a

score >5 had a hazard ratio of 1.11 (95% CI, 0.53–2.30) compared

to patients with a CCI <4. Neither comparison reached

statistical significance (P=0.6) and these findings were consistent

across both univariate and multivariate models. However, the median

age of the cohort in the study by Eriguchi et al (47) was slightly older at 79 years (range,

55–88 years) compared with that of the present SBRT cohort at 74

years (range, 45–91 years). Furthermore, the median follow-up time

of their study was notably shorter compared with that of the

present analysis (40 vs. 149 months). In addition, different ethnic

backgrounds (Asian vs. European patients) should be considered in

the interpretation of the different outcomes between CCI and

survival.

Ganti et al (48) examined the prognostic role of CCI in

terms of survival based on a large sample size (n=617) of patients

with NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Multivariate

regression models showed no correlation between survival and the

age-adjusted CCI or CCI without age-adjustment. In contrast to the

present findings, another study conducted on 2,221 patients with

lung cancer treated with SBRT showed a significant association

between OS and CCI as well as between lung cancer specific survival

and CCI (49). The patient

characteristics and follow-up time differed when compared with the

present study; the median 5-year OS rate was 34 months for patients

with pathological confirmation of their diagnosis compared with 26

months in the present study.

PET-CT based treatment planning have shown good

clinical outcomes in inoperable adenocarcinoma, with higher PET-CT

SUVmax values before SBRT being associated with increased risk of

failure (50). When using

PET-CT-based radiation planning, the GTV and clinical tumor volume

could be significantly reduced and accuracy improved (51–53).

Additionally, recent studies have established predictive models for

treatment outcomes (PFS and distant metastasis-free survival) after

SBRT based on radiomic features and PET-CT (54–57).

Although PET-CT-based treatment planning has demonstrated clinical

value in previous studies (52,54,58,59),

it was not included in the present multivariate Cox regression

model. Due to the limited overall sample size, the number of

variables that could be entered into the model had to be restricted

to avoid overfitting. As a result, only covariates with

statistically significant associations in the univariate analysis

(P<0.05) were selected for multivariate modeling. PET-CT did not

meet this criterion and was therefore excluded from further

analysis.

PET-CT was already established as a routine imaging

modality during the treatment period and was used in a large

proportion of the present cohort. The contribution of PET-CT to

improved clinical outcomes may have been indirectly captured

through a more accurate GTV definition, which was significantly

associated with OS (52). PET-CT

enables precise delineation of GTV, often resulting in reduced

volumes and improved dose conformity (60). In the present dataset, GTV emerged

as an independent predictor of OS in both univariate and

multivariate analyses. Thus, the prognostic effect of PET-CT-based

planning may have been reflected through its influence on GTV, even

though it was not explicitly included as a covariate in the final

model.

A key limitation of the present retrospective,

single-center analysis lies in the inherent risk of selection bias

and residual confounding due to the non-randomized nature of the

cohort. Although missing data and potential bias was addressed

through multiple imputations and complete-case sensitivity

analyses, these methods rely on assumptions (for example, data

missing at random) that cannot be fully verified. Furthermore, the

absence of randomization limits causal inference and associations

observed in multivariate models should be interpreted as

exploratory rather than confirmatory.

The monocentric design further restricts the

generalizability of the present findings, as treatment protocols,

patient selection and follow-up strategies may differ across

institutions. The relatively small sample size limits statistical

power, particularly for subgroup analyses, and increases the risk

of type II errors. Although GTV and age emerged as significant

prognostic factors in both primary and imputed models, these

findings warrant validation in larger, multicenter cohorts.

Additionally, the retrospective nature of data collection led to

incomplete documentation of certain clinical variables and

inconsistent reporting of toxicity or recurrence, precluding

analysis of endpoints such as local control or PFS. Due to this, OS

remained the only robust endpoint available for analysis. Finally,

the lack of standardized imaging protocols and follow-up intervals

may have introduced variability in outcome assessment. Despite the

application of rigorous statistical methods, these methodological

limitations underscore the need for prospective, multicenter

studies with standardized data collection to improved understand

the long-term outcomes of SBRT in early-stage NSCLC.

A potential concern in long-term survival analyses

of elderly or comorbid patients is the risk of loss to follow-up or

competing events unrelated to cancer, such as non-cancer-related

deaths. In the present cohort, follow-up was actively conducted via

association with the local citizen registration office, which

allowed for robust and reliable ascertainment of vital status for

all patients. Therefore, no patients were lost to follow-up and OS

could be determined with high confidence. However, due to the

retrospective design and limited availability of cause-of-death

information and cancer-specific survival could not be evaluated. As

such, the reported OS includes both cancer-related and

non-cancer-related deaths. This limitation is particularly relevant

in an elderly cohort with substantial comorbidities, where

non-cancer mortality may compete with oncologic outcomes. While the

CCI was included in the analysis to account for overall comorbidity

burden, it was not significantly associated with survival in the

present models. The influence of competing risks, especially in

older patients or those with severe COPD, should be considered when

interpreting the OS results. Future prospective studies with

detailed documentation of cause of death and competing events are

warranted to separate cancer-specific outcomes from broader

survival metrics in SBRT-treated patients with NSCLC.

In the present multivariate Cox regression analysis,

GTV emerged as an independent predictor of OS, with larger tumor

volumes being significantly associated with worse outcomes. This

finding is consistent with previously published evidence,

reinforcing the prognostic relevance of tumor volume in

SBRT-treated patients with NSCLC. Kessel et al (61) analyzed 219 patients with lung

metastases and confirmed that smaller GTV and PTV were

significantly associated with improved OS using a univariate

analysis. In addition to the favorable oncologic outcomes, low

rates of physician- and patient-reported high-grade toxicity even

after long-term follow-up, were reported. This underlines the

importance of minimizing irradiated volume not only to reduce

toxicity but also to potentially improve survival. The integration

of patient-reported outcomes further emphasized the impact of

respiratory symptoms such as severe dyspnea on patients' quality of

life and highlights the clinical relevance of sparing functional

lung tissue, especially in patients with compromised pulmonary

function (61). These results

underscore the importance of volumetric parameters such as GTV and

PTV in SBRT planning and outcomes. The present results contributed

to this evidence by demonstrating that even in a real-world cohort

with heterogeneous stages and performance statuses, tumor volume

remained a robust and independent prognostic factor for survival.

Future analysis should also focus on the long-term outcomes of

medically operable early-stage patients with lung cancer treated

with surgery compared with SBRT. Due to the lack of prospective,

randomized trials comparing both treatments, advanced statistical

methods such as propensity score matching are needed to evaluate

these treatment outcomes.

The present study provided long-term survival data

for early-stage patients with NSCLC treated with SBRT. Although OS

rates remained limited, patients aged ≥75 years demonstrated better

outcomes, likely reflecting more selective inclusion of older

patients with lower tumor burden and favorable clinical

characteristics. Tumor volume was independently associated with OS,

highlighting its prognostic relevance in this setting. By contrast,

BEDmean and performance status were not significant predictors.

These findings emphasize the importance of tumor characteristics

over chronological age when considering SBRT for early-stage

NSCLC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JAM performed the data analysis. SG, CK, CP and DV

contributed to the refinement of the analysis. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript. JAM and DV confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Medical Faculty of Martin Luther University

Halle-Wittenberg [Halle (Saale), Germany; approval no. 2025-006].

As patient data was obtained from the University Hospital Halle, it

should be noted that the University Hospital Halle serves as the

academic teaching hospital and clinical center of the Medical

Faculty of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work the author(s)

used ChatGPT, a language model developed by OpenAI Inc., in order

to improve writing style and check grammar and spelling. After

using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as

needed and took full responsibility for the content of the

publication.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BED

|

biologically effective dose

|

|

CCI

|

Charlson comorbidity index

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

|

COPD

|

chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease

|

|

FDG-PET

|

fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography

|

|

FEV1

|

forced expiratory volume in 1

second

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

KPS

|

Karnofsky performance status

|

|

SCLC

|

small cell lung cancer

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-SCLC

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

RT

|

radiotherapy

|

|

SBRT

|

stereotactic body radiation

therapy

|

|

UICC

|

Unité International Contre Le

Cancer

|

|

VATS L-MLND

|

video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical

lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Islami F, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global

trends of lung cancer mortality and smoking prevalence. Transl Lung

Cancer Res. 4:327–338. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Koch M, Gräfenstein L, Karnosky J, Schulz

C and Koller M: Psychosocial burden and quality of life of lung

cancer patients: Results of the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-LC29

questionnaire and hornheide screening instrument. Cancer Manag Res.

13:6191–6197. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, Zhao M, Li M, Ma K,

Yin J, Zhan C and Wang Q: Trends in the incidence, treatment, and

survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades.

Cancer Manag Res. 11:943–953. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P, Meldgaard P,

Nicolson M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Smit EF, Syrigos K, Stahel R, et

al: 2nd ESMO consensus conference on lung cancer: Non-small-cell

lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in

advanced disease. Ann Oncol. 25:1475–1484. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tan WL, Jain A, Takano A, Newell EW, Iyer

NG, Lim WT, Tan EH, Zhai W, Hillmer AM, Tam WL and Tan DSW: Novel

therapeutic targets on the horizon for lung cancer. Lancet Oncol.

17:e347–e362. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Palma D, Visser O, Lagerwaard FJ,

Belderbos J, Slotman BJ and Senan S: Impact of introducing

stereotactic lung radiotherapy for elderly patients with stage I

non-small-cell lung cancer: A population-based time-trend analysis.

J Clin Oncol. 28:5153–5159. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Palma DA and Senan S: Improving outcomes

for high-risk patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer:

Insights from population-based data and the role of stereotactic

ablative radiotherapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 14:1–5. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Potters L, Kavanagh B, Galvin JM, Hevezi

JM, Janjan NA, Larson DA, Mehta MP, Ryu S, Steinberg M, Timmerman

R, et al: American society for therapeutic radiology and oncology

(ASTRO) and American college of radiology (ACR) practice guideline

for the performance of stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 76:326–332. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, Michalski

J, Straube W, Bradley J, Fakiris A, Bezjak A, Videtic G, Johnstone

D, et al: Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early

stage lung cancer. JAMA. 303:1070–1076. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Senthi S, Haasbeek CJA, Slotman BJ and

Senan S: Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for central

lung tumours: A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 106:276–282.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ball D, Mai GT, Vinod S, Babington S,

Ruben J, Kron T, Chesson B, Herschtal A, Vanevski M, Rezo A, et al:

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy in

stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer (TROG 09.02 CHISEL): A phase 3,

open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 20:494–503.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, Mehran RJ,

Louie AV, Balter P, Groen HJM, McRae SE, Widder J, Feng L, et al:

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable

stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: A pooled analysis of two

randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 16:630–637. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chang JY, Mehran RJ, Feng L, Verma V, Liao

Z, Welsh JW, Lin SH, O'Reilly MS, Jeter MD, Balter PA, et al:

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for operable stage I

non-small-cell lung cancer (revised STARS): Long-term results of a

single-arm, prospective trial with prespecified comparison to

surgery. Lancet Oncol. 22:1448–1457. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Altorki N, Wang X, Damman B, Mentlick J,

Landreneau R, Wigle D, Jones DR, Conti M, Ashrafi AS, Liberman M,

et al: Lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection for peripheral

clinical T1aN0 non-small cell lung cancer: A post hoc analysis of

CALGB 140503 (Alliance). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 167:338–347.e1.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou S-HI, Gandara DR,

Anton-Culver H and Jablons DM: Natural history of stage I non-small

cell lung cancer: Implications for early detection. Chest.

132:193–199. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Baine MJ, Verma V, Schonewolf CA, Lin C

and Simone CB II: Histology significantly affects recurrence and

survival following SBRT for early stage non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung Cancer. 118:20–26. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang J, Yang F, Li B, Li H, Liu J, Huang

W, Wang D, Yi Y and Wang J: Which is the optimal biologically

effective dose of stereotactic body radiotherapy for Stage I

non-small-cell lung cancer? A meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys. 81:e305–e316. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Birim O, Kappetein AP and Bogers AJJC:

Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of long-term outcome

after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac

Surg. 28:759–762. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Birim O, Maat APWM, Kappetein AP, van

Meerbeeck JP, Damhuis RAM and Bogers AJJC: Validation of the

Charlson comorbidity index in patients with operated primary

non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 23:30–34.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL and

MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in

longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis.

40:373–383. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Edge SB and Compton CC: The American joint

committee on cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging

manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 17:1471–1474. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK and

Wittekind C: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 8th Edition.

Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ, USA: pp. 129–136. 2016

|

|

24

|

Cerfolio RJ, Ojha B, Bryant AS, Raghuveer

V, Mountz JM and Bartolucci AA: The accuracy of integrated PET-CT

compared with dedicated PET alone for the staging of patients with

nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 78:1017–1023. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Clarke K, Taremi M, Dahele M, Freeman M,

Fung S, Franks K, Bezjak A, Brade A, Cho J, Hope A and Sun A:

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC): Is FDG-PET a predictor of outcome? Radiother Oncol.

104:62–66. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Freeman M, Ennis M and Jerzak KJ:

Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≤60 is strongly associated with

shorter brain-specific progression-free survival among patients

with metastatic breast cancer with brain metastases. Front Oncol.

12:8674622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D and Tamburini M:

Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: A

prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single

institution. Eur J Cancer. 32A:1135–1141. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Halpin D,

Anzueto A, Barnes P, Bourbeau J, Han MK, Martinez FJ, Montes de Oca

M, et al: Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

207:819–837. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mirza S, Clay RD, Koslow MA and Scanlon

PD: COPD guidelines: A review of the 2018 GOLD report. Mayo Clin

Proc. 93:1488–1502. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J and

Patierno C: Charlson comorbidity index: A critical review of

clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 91:8–35. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fowler JF: The linear-quadratic formula

and progress in fractionated radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 62:679–694.

1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Klement RJ, Sonke JJ, Allgäuer M,

Andratschke N, Appold S, Belderbos J, Belka C, Blanck O, Dieckmann

K, Eich HT, et al: Correlating dose variables with local tumor

control in stereotactic body radiation therapy for early-stage

non-small cell lung cancer: A modeling study on 1500 individual

treatments. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 107:579–586. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang Z: Variable selection with stepwise

and best subset approaches. Ann Transl Med. 4:1362016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Henschke CI, Yip R, Sun Q, Li P, Kaufman

A, Samstein R, Connery C, Kohman L, Lee P, Tannous H, et al:

Prospective cohort study to compare long-term lung cancer-specific

and all-cause survival of clinical early stage (T1a-b; ≤20 mm)

NSCLC treated by stereotactic body radiation therapy and surgery. J

Thorac Oncol. 19:476–490. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fan S, Zhang Q, Chen J, Chen G, Zhu J, Li

T, Xiao H, Du S, Zeng Z and He J: Comparison of long-term outcomes

of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) via Helical tomotherapy

for early-stage lung cancer with or without pathological proof.

Radiat Oncol. 18:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Speicher PJ and D'Amico TA: Weighing the

relative importance of short-term versus long-term outcomes when

comparing surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 10 (Suppl

17):S2022–S2024. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Arnett ALH, Mou B, Owen D, Park SS, Nelson

K, Hallemeier CL, Sio T, Garces YI, Olivier KR and Merrell KW:

Long-term clinical outcomes and safety profile of SBRT for

centrally located NSCLC. Adv Radiat Oncol. 4:422–428. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Guckenberger M, Allgäuer M, Appold S,

Dieckmann K, Ernst I, Ganswindt U, Holy R, Nestle U,

Nevinny-Stickel M, Semrau S, et al: Safety and efficacy of

stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage 1 non-small-cell lung

cancer in routine clinical practice: A patterns-of-care and outcome

analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 8:1050–1058. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jimenez-Jimenez E, Marti-Laosa MM,

Nieto-Guerrero JM, Perez ME, Gómez M, Lozano E and Sabater S:

Biologically effective dose (BED) value lower than 120 Gy improve

outcomes in lung SBRT. Clin Transl Oncol. 26:1203–1208. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kreinbrink P, Blumenfeld P, Tolekidis G,

Sen N, Sher D and Marwaha G: Lung stereotactic body radiation

therapy (SBRT) for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in the

very elderly (≥80 years old): Extremely safe and effective. J

Geriatr Oncol. 8:351–355. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Pop DD, Hopîrtean C, Coşer F, Dan F, Zah

T, Fekete Z, Chiş A, Tufăscu G, Udrea A and Mihai A: Implementation

of advanced radiotherapy techniques: Stereotactic body radiotherapy

(SBRT) for oligometastatic patients with lung metastasis-a single

institution experience. Med Pharm Rep. 95:410–417. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Guo Y, Zhu Y, Zhang R, Yang S, Kepka L,

Viani GA, Milano MT, Sio TT, Sun X, Wu H, et al: Five-year

follow-up after stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically

inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter

study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 12:1293–1302. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Onishi H, Shioyama Y, Matsumoto Y, Matsuo

Y, Miyakawa A, Yamashita H, Matsushita H, Aoki M, Nihei K, Kimura

T, et al: Real-world results of stereotactic body radiotherapy for

399 medically operable patients with stage I histology-proven

non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 15:43822023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Snider M, Salama JK and Boyer M: Survival

and recurrence rates following SBRT or surgery in medically

operable stage I NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 197:1079622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wong OY, Yau V, Kang J, Glick D, Lindsay

P, Le LW, Sun A, Bezjak A, Cho BCJ, Hope A and Giuliani M: Survival

impact of cardiac dose following lung stereotactic body

radiotherapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 19:e241–e246. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Baker S, Sharma A, Peric R, Heemsbergen WD

and Nuyttens JJ: Prediction of early mortality following

stereotactic body radiotherapy for peripheral early-stage lung

cancer. Acta Oncol. 58:237–242. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Eriguchi T, Takeda A, Sanuki N, Tsurugai

Y, Aoki Y, Oku Y, Hara Y, Akiba T and Shigematsu N: Stereotactic

body radiotherapy for operable early-stage non-small cell lung

cancer. Lung Cancer. 109:62–67. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ganti AK, Siedlik E, Marr AS, Loberiza FR

Jr and Kessinger A: Predictive ability of Charlson comorbidity

index on outcomes from lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 34:593–596.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wilkie JR, Lipson R, Johnson MC, Williams

C, Moghanaki D, Elliott D, Owen D, Atluri N, Jolly S and Chapman

CH: Use and outcomes of SBRT for early stage NSCLC without

pathologic confirmation in the veterans health care administration.

Adv Radiat Oncol. 6:1007072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Moraes FY, Abreu CECV, Siqueira GSM,

Haddad CK, Degrande FAM, Hopman WM, Neves-Junior WFP, Gadia R and

Carvalho HA: Applying PET-CT for predicting the efficacy of SBRT to

inoperable early-stage lung adenocarcinoma: A Brazilian

case-series. Lancet Reg Health Am. 11:1002412022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mahasittiwat P, Yuan S, Xie C, Ritter T,

Cao Y, Ten Haken RK and Kong FMS: Metabolic tumor volume on PET

reduced more than gross tumor volume on CT during radiotherapy in

patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with 3DCRT or

SBRT. J Radiat Oncol. 2:191–202. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chirindel A, Adebahr S, Schuster D,

Schimek-Jasch T, Schanne DH, Nemer U, Mix M, Meyer P, Grosu AL,

Brunner T and Nestle U: Impact of 4D-(18)FDG-PET/CT imaging on

target volume delineation in SBRT patients with central versus

peripheral lung tumors. Multi-reader comparative study. Radiother

Oncol. 115:335–341. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hoopes DJ, Tann M, Fletcher JW, Forquer

JA, Lin PF, Lo SS, Timmerman RD and McGarry RC: FDG-PET and

stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I non-small-cell

lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 56:229–234. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen K, Hou L, Chen M, Li S, Shi Y, Raynor

WY and Yang H: Predicting the efficacy of SBRT for lung cancer with

18F-FDG PET/CT radiogenomics. Life (Basel).

13:8842023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Thor M, Fitzgerald K, Apte A, Oh JH, Iyer

A, Odiase O, Nadeem S, Yorke ED, Chaft J, Wu AJ, et al: Exploring

published and novel pre-treatment CT and PET radiomics to stratify

risk of progression among early-stage non-small cell lung cancer

patients treated with stereotactic radiation. Radiother Oncol.

190:1099832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yu X, He L, Wang Y, Dong Y, Song Y, Yuan

Z, Yan Z and Wang W: A deep learning approach for automatic tumor

delineation in stereotactic radiotherapy for non-small cell lung

cancer using diagnostic PET-CT and planning CT. Front Oncol.

13:12354612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yu L, Zhang Z, Yi H, Wang J, Li J, Wang X,

Bai H, Ge H, Zheng X, Ni J, et al: A PET/CT radiomics model for

predicting distant metastasis in early-stage non-small cell lung

cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: A

multicentric study. Radiat Oncol. 19:102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Tyran M, Charrier N, Darreon J, Madroszyk

A, Tallet A and Salem N: Early PET-CT after stereotactic

radiotherapy for stage 1 non-small cell lung carcinoma is

predictive of local control. In Vivo. 32:121–124. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Borm KJ, Oechsner M, Schiller K, Peeken

JC, Dapper H, Münch S, Kroll L, Combs SE and Duma MN: Prognostische

Faktoren bei der stereotaktischen Strahlentherapie von

Lungenmetastasen. Strahlenther Onkol. 194:886–893. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Retif P, Verrecchia-Ramos E, Saleh M,

Djibo Sidikou A, Letellier R, Al Salah A, Pfletschinger E, Taesch

F, Ben-Mahmoud S and Michel X: On the use of 4D-PET/CT for the safe

SBRT re-irradiation of central lung recurrence within

radiation-induced fibrosis: A clinical case. J Clin Med.

14:40152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kessel KA, Grosser RCE, Kraus KM, Hoffmann

H, Oechsner M and Combs SE: Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT)

in patients with lung metastases-prognostic factors and long-term

survival using patient self-reported outcome (PRO). BMC Cancer.

20:4422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|