Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most

common malignancy of the oral cavity and accounts for approximately

90% of all oral cancers (1–3). It represents a major subgroup of head

and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), which are among the

sixth most common cancers worldwide, with over 500,000 new cases

annually (2). Despite advances in

surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the prognosis of patients

with recurrent or metastatic OSCC (R/M-OSCC) remains poor.

Since the 1980s, platinum-based chemotherapy

regimens have served as the standard treatment for advanced head

and neck cancers. The EXTREME regimen, which combines

5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and cetuximab, became a standard of care

in 2012 (4). More recently, immune

checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab,

targeting the programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) pathway, have expanded the therapeutic landscape and shown

promising efficacy in R/M-HNSCC, including OSCC (5,6). These

agents are now widely used in clinical practice in Japan and

globally. However, ICIs are not universally effective, and their

clinical benefit is limited to a subset of patients (7). Therefore, there is a pressing need to

identify reliable biomarkers to predict which patients are most

likely to respond to ICI therapy. While previous studies have

proposed PD-L1 expression, tumor mutational burden, and

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as candidate predictive

biomarkers, none have demonstrated sufficient sensitivity or

specificity for routine clinical use (8–10).

In recent years, inflammation- and nutrition-based

biomarkers have emerged as potential prognostic indicators in

various malignancies, including head and neck cancers (11–25).

These include the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (13–16,23,25–30),

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) (14–18,23,24),

lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) (25), C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio

(CAR) (12,20), prognostic nutritional index (PNI)

(31,32), and modified Glasgow Prognostic Score

(mGPS) (22,24). These markers are simple to calculate

using routinely available laboratory data and reflect the complex

interplay between systemic inflammation, nutritional status, and

cancer progression. Although several reports have explored the

prognostic significance of these markers in HNSCC, limited data

exist regarding their role in predicting the response and outcomes

of ICI treatment specifically in patients with OSCC. Moreover, it

remains unclear whether the timing of biomarker evaluation, before

or after ICI initiation, affects their prognostic utility.

Therefore, the aim of this retrospective study was

to evaluate the clinical relevance of inflammation- and

nutrition-based biomarkers as predictors of treatment response and

prognosis in patients with R/M-OSCC receiving ICI therapy. We also

investigated whether biomarker levels assessed after ICI

administration offer superior prognostic value compared to those

assessed prior to treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the

clinical data of 45 patients with R/M-OSCC treated with ICIs

between October 2017 and December 2024 at Hiroshima University

Hospital (Hiroshima, Japan). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years,

had histologically confirmed OSCC arising exclusively from the oral

cavity (excluding oropharyngeal subsites, such as the soft palate,

base of the tongue, and tonsillar region; this definition aligns

with previous clinical studies that focus solely on cancers of the

oral cavity), received at least one cycle of ICI therapy, and had

adequate clinical data including laboratory results and follow-up

information. Patients were excluded if they had concurrent

malignancies, active autoimmune diseases, or insufficient medical

records. The observation period was defined as the interval from

the initiation of ICI therapy to the date of death, last follow-up,

or the data cutoff (February 1, 2025), whichever came first.

Data collection and definitions

We assessed the following parameters: Age, sex,

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS),

primary tumor site, disease stage, presence of target lesions,

treatment line, history of surgery, history of radiotherapy,

combined positive score (CPS), chemotherapy regimen and dose,

initial treatment, presence or absence of radiotherapy, observation

period, number of treatment cycles, IBPSs before and after

treatment, overall survival (OS), one-year and two-year survival

rates, progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate

(ORR), disease control rate (DCR), best overall response, presence

or absence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), and details of

irAEs. All patients were staged according to the eighth edition of

the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM staging system

(33). In this study, OSCC was

defined as squamous cell carcinoma that arises exclusively from the

oral cavity, excluding oropharyngeal subsites, such as the soft

palate, base of the tongue, and tonsillar region.

The IBPSs were calculated as follows: the NLR was

determined by dividing the absolute neutrophil count

(/mm3) by the absolute lymphocyte count

(/mm3); LMR was calculated by dividing the absolute

lymphocyte count (/mm3) by the absolute monocyte count

(/mm3); PLR was determined by dividing the absolute

platelet count (/mm3) by the absolute lymphocyte count

(/mm3); CAR was calculated by dividing the C-reactive

protein (CRP) concentration (mg/dl) by the serum albumin

concentration (g/dL); and PNI was calculated as 10× serum albumin

concentration (g/dl) + 0.005× total lymphocyte count

(/mm3). These values were obtained from the blood test

results obtained within 1 week prior to the first day of ICI

administration and 4–6 weeks after the initiation of ICI

therapy.

In our department, the treatment strategy for

R/M-OSCC is guided by platinum sensitivity. For platinum-resistant

cases, nivolumab was administered intravenously at a dose of 3

mg/kg (between 2017 and September 2018) and at 240 mg every two

weeks (from October 2018 to February 2025). For platinum-sensitive

cases, pembrolizumab was used either as monotherapy or in

combination therapy. In platinum-sensitive patients with adequate

tolerance for combination therapy involving platinum agents and

5-fluorouracil (5-FU), treatment selection was based on the CPS.

Specifically, PD-L1 expression was evaluated using

immunohistochemistry with the Dako 22C3 pharmDx assay on

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor specimens. The CPS was

calculated by dividing the number of PD-L1-positive cells

(including tumor cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages) by the total

number of viable tumor cells, then multiplying by 100. A CPS of ≥1

was considered positive, in accordance with established diagnostic

criteria. All CPS evaluations were conducted by board-certified

oral pathologists with expertise in head and neck malignancies.

Pembrolizumab monotherapy was administered if CPS was ≥20%, while

pembrolizumab was combined with cisplatin (80 mg/m2) and

5-FU (800 mg/m2) for CPS values of 1–19 and <1%,

respectively. However, treatment decisions were made

comprehensively, considering factors such as age, comorbidities,

tumor growth rate, and overall performance status. In cases where

patients were unable to tolerate platinum-based agents or 5-FU,

pembrolizumab monotherapy or the EXTREME regimen was considered as

alternative treatment options. Following the discontinuation of

ICIs, subsequent chemotherapy was administered at the physician's

discretion.

Treatment efficacy was assessed using the Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (34). Following the administration of ICIs,

imaging studies, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance

imaging, and F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography,

were performed every two to three months or as clinically

indicated. The DCR was calculated as the sum of the complete

response (CR), partial response (PR), and stable disease (SD)

rates. OS was defined as the time from the first day of ICI

administration to the date of death or the date of the final

analysis (February 1, 2025), whichever was earlier. PFS was defined

as the time from the first day of ICI administration to the date of

disease progression or death.

Statistical analysis

To determine the cutoff values of biomarkers before

and after treatment, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

were constructed for disease control (CR + PR + SD). OS and PFS

were compared using the log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival

curves. P-values were calculated using the log-rank test.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify

prognostic factors, with the multivariate analysis performed using

the Cox proportional hazards model to determine predictors of OS

and PFS. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. P-values were determined using chi-square

tests to assess the association between categorical variables. In

cases with small sample sizes or expected cell counts, Fisher's

exact test was employed to ensure accurate statistical inference.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics

(version 30.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statements

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles of The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the

Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University (approval no. E2024-0196).

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics

Committee owing to the retrospective design of the study.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

outcomes

A total of 45 patients were enrolled in the study

(Table SI). The age of the

patients ranged from 35 to 84 years, with a median of 67 years. The

cohort consisted of 29 (64%) males and 16 (36%) females. Regarding

ECOG PS, 34 patients had a PS of 0, six had a PS of 1, one had a PS

of 2, and four had a PS of 3. The primary tumor site was

predominantly the tongue, observed in 24 (53%) patients. Other

primary sites included the maxillary gingiva in six (13%) patients,

mandibular gingiva in five (11%) patients, and buccal mucosa and

floor of the mouth in four (9%) patients each. At the initial

diagnosis, four patients were classified as stage I, 13 as stage

II, three as stage III, and 24 as stage IV. Nivolumab was

administered to 23 (51%) patients, while pembrolizumab was used in

22 (49%) patients. Surgical resection was performed as the initial

treatment in 42 (93%) patients, and radiotherapy was administered

to 39 (87%) patients. Of the 42 patients who underwent surgery, 41

had neck dissections, and one had surgery on the primary tumor. In

the one case, the patient discontinued outpatient follow-up after

primary tumor resection. Upon re-presentation, disease progression

was observed, and curative surgery was considered unfeasible due to

local recurrence and cervical lymph node metastasis. Therefore,

treatment with an ICI was initiated. Regarding target lesions,

distant metastases were present in 21 (47%) patients, whereas 12

(27%) patients had local residual disease. CPS expression of ≥ 20%

was observed in 29 (64%) patients. Regarding ICI administration,

monotherapy was used in 33 (73%) patients, while 12 (27%) patients

received combination therapy with chemotherapy.

The number of ICI administrations ranged from one to

68, with a median of five (Table

SII). Treatment efficacy was evaluated according to the

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria. CR was

observed in four (9%) patients, PR in six (13%) patients, SD in

five (11%) patients, and progressive disease in 30 (67%) patients.

The ORR, calculated as the sum of CR and PR, was 22%, while the

DCR, defined as the sum of CR, PR, and SD, was 33%. irAEs occurred

in 13 (29%) patients. The most common irAE was thyroid dysfunction,

observed in four (9%) patients, followed by interstitial pneumonia

in three (7%) patients and colitis in two (4%) patients. Other

reported adverse events included dermatologic disorders,

interstitial nephritis, hypopituitarism, neurological impairment,

atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney failure.

Survival analysis for OS and PFS after

ICI administration

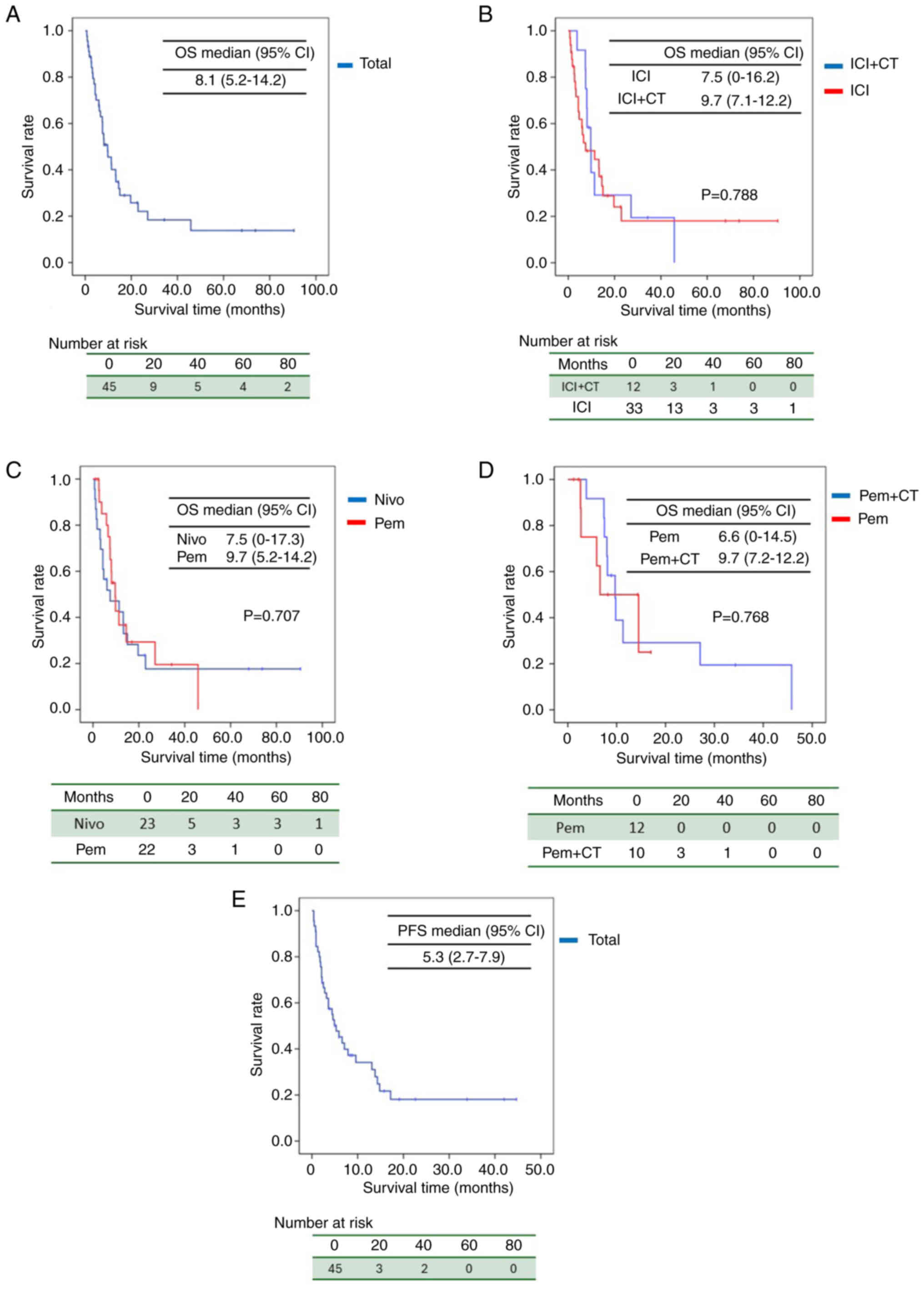

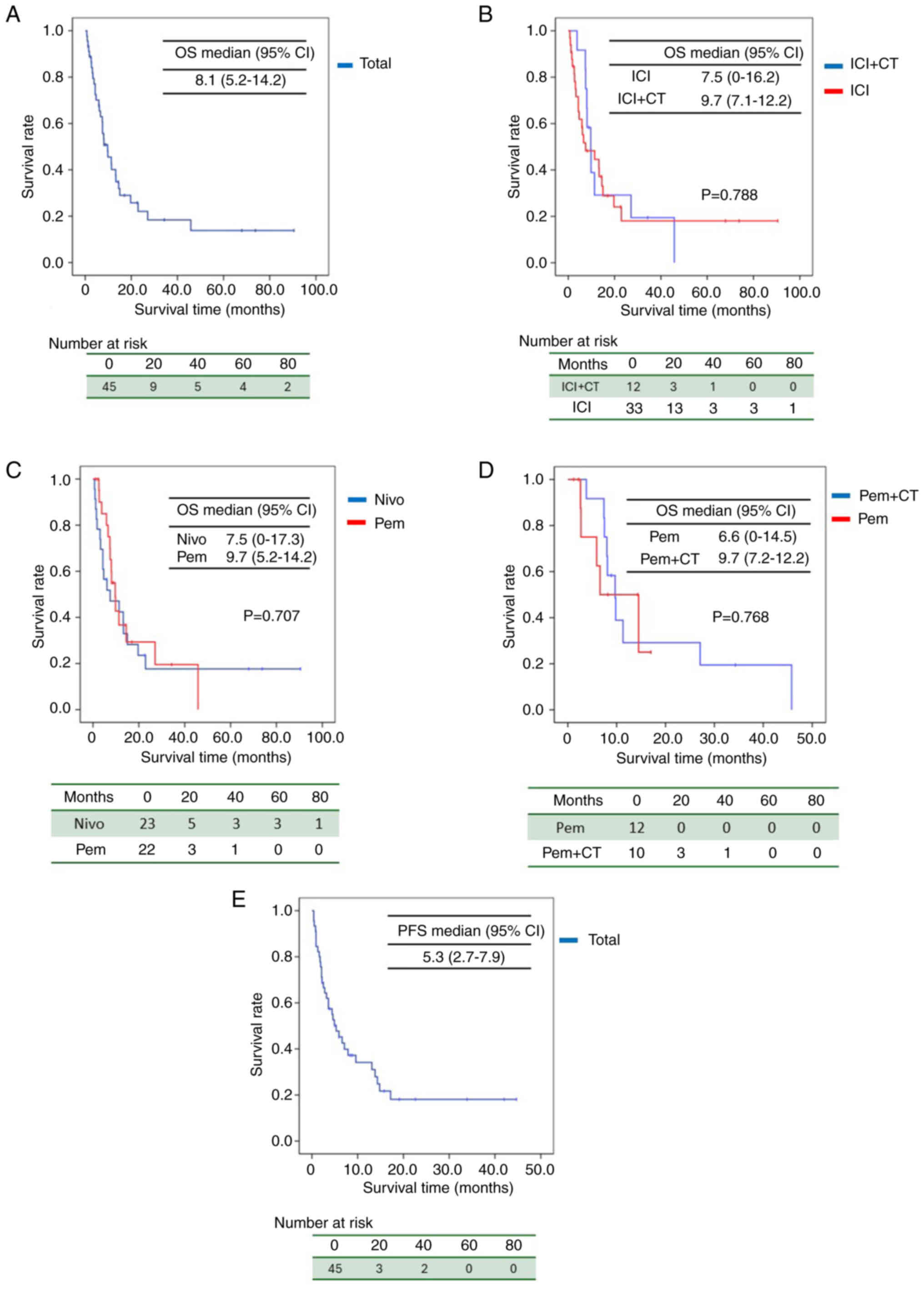

Figure 1 presents the results of OS analysis. In the

overall cohort of ICI-treated patients, the 1-year survival rate

was 40%, 2-year survival rate was 22%, and median OS was 8.1 months

[95% confidence interval (CI): 5.2–14.2] (Fig. 1A). For patients receiving ICI

monotherapy, the median OS was 7.5 months (95% CI: 016.2), whereas

for those receiving ICI in combination with chemotherapy, the

median OS was 9.7 months (95% CI: 7.1–12.2), with a log-rank test

P-value of 0.788 (Fig. 1B).

| Figure 1.Kaplan-Meier curves for OS. (A) OS of

the ICI-treated cohort, (B) OS of patients receiving ICI

monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy, (C) OS of patients

treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, (D) OS of patients treated

with pembrolizumab or in combination with chemotherapy, and (E) PFS

of the ICI-treated cohort. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; OS,

overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; CI, confidence

interval; CT, chemotherapy; Nivo, nivolumab; Pem,

pembrolizumab. |

For patients treated with nivolumab, the median OS

was 7.5 months (95% CI: 0–17.3), whereas for those treated with

pembrolizumab, the median OS was 9.7 months (95% CI: 5.2–14.2),

with a P-value of 0.707 (Fig. 1C).

Among patients treated with pembrolizumab, those receiving

chemotherapy alone had a median OS of 6.6 months (95% CI: 0–14.5),

whereas those receiving pembrolizumab in combination with

chemotherapy had a median OS of 9.7 months (95% CI: 7.2–12.2)

(Fig. 1D). Similar to the findings

of the KEYNOTE-048 trial, a trend toward prolonged OS was observed

with the addition of chemotherapy. The one-year and two-year PFS

rates for all patients were 34 and 6.7%, respectively, with a

median PFS of 5.3 months (Fig.

1E).

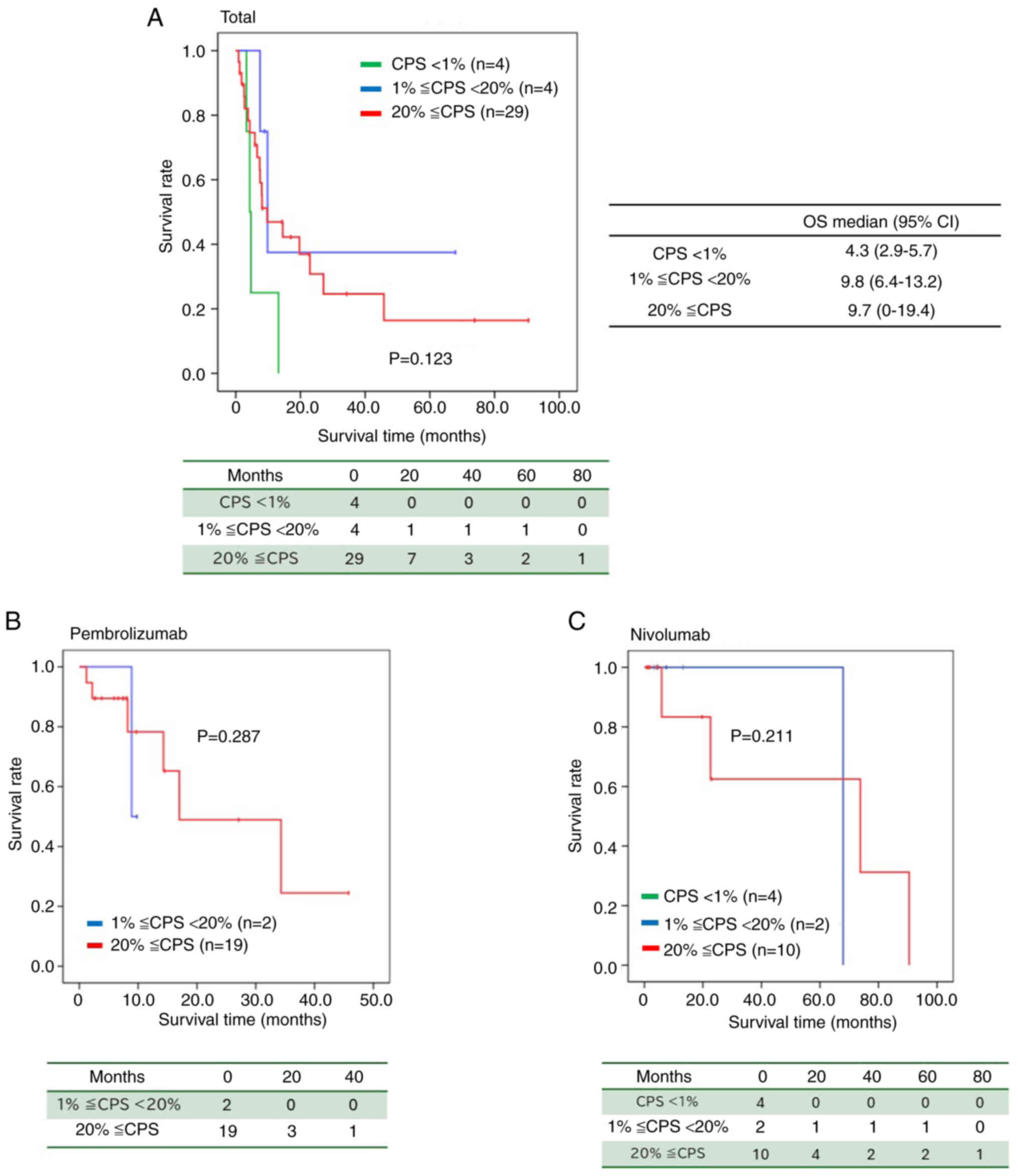

Figure 2 illustrates the OS according to CPS values.

In patients with CPS <1, the median OS was 4.3 months (95% CI:

2.9–5.7), whereas for those with CPS between 1 and <20, the

median OS was 9.8 months (95% CI: 6.4–13.2). For patients with CPS

≥20, the median OS was 9.7 months (95% CI: 0–19.4), with a P-value

of 0.123 (Fig. 2A).

Furthermore, in patients treated with pembrolizumab,

those with CPS between 1 and <20 had a median OS of 8.9 months,

whereas those with CPS ≥20 had a median OS of 17.0 months (95% CI:

0–34.6) (P=0.287) (Fig. 2B).

Compared with patients with CPS <1, those with CPS ≥1 tended to

have a prolonged median OS (Fig.

2A-C).

Cutoff values for pre- and

post-treatment markers according to ROC curve

ROC curves were constructed to assess the

discriminatory ability of biomarkers before and after treatment,

and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated (Fig. S1). The AUC values for pre-treatment

markers were as follows: 0.53802 for pre-NLR, 0.4735 for pre-LMR,

0.59217 for pre-PNI, 0.50691 for pre-PLR, 0.39516 for pre-CAR,

0.55876 for pre-eosinophils, and 0.58641 for pre-lymphocytes. In

contrast, the AUC values for post-treatment markers were 0.76959

for post-NLR, 0.68779 for post-LMR, 0.69585 for post-PNI, 0.64747

for post-PLR, 0.73618 for post-CAR, 0.51382 for post-eosinophils,

and 0.69935 for post-lymphocytes. Among all markers evaluated

before and after treatment, post-treatment NLR demonstrated the

highest AUC of 0.76959, with a cutoff value of 7.17 (Table SIII).

Univariate and multivariate analyses

results of prognostic factors for OS and PFS

We evaluated the impact of various factors on OS,

including age, sex, ECOG PS, type of ICI, presence or absence of

irAEs, ICI combination therapy, history of radiotherapy, body mass

index (BMI) based on cutoff values calculated from the ROC curve,

CPS value, DCR, and primary site (tongue vs. other), as shown in

Table I. In univariate analysis, a

higher ECOG PS was associated with poorer OS [hazard ratio

(HR)=2.50; 95% CI=1.17–5.33; P=0.0185], and patients with PD as the

efficacy of ICI had poorer OS (HR=4.30; 95% CI=1.79–10.33;

P=0.0011). Conversely, in multivariate analysis, male sex was

associated with poorer OS (HR=3.37; 95% CI=1.11–10.19; P=0.0316),

and patients with PD as the efficacy of ICI demonstrated poorer OS

(HR=6.96; 95% CI=1.80–27.03; P=0.0050).

| Table I.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of prognosis factors for OS. |

Table I.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of prognosis factors for OS.

|

|

| Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Number | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<65 | 20 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65 | 25 | 1.06 | 0.53–2.14 | 0.864 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 29 | 1.46 | 0.70–3.04 | 0.298 | 3.37 | 1.11–10.19 | 0.0316a |

|

Female | 16 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| ECOG PS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 34 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≥1 | 11 | 2.50 | 1.17–5.33 | 0.0185a |

|

|

|

| ICI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nivolumab | 23 | 1.14 | 0.57–2.28 | 0.707 |

|

|

|

|

Pembrolizumab | 22 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| irAE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 32 | 1.18 | 0.47–2.96 | 0.736 |

|

|

|

| ICI

combination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monotherapy | 33 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| With

chemotherapy | 12 | 1.09 | 0.41–2.86 | 0.865 |

|

|

|

| Radiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Previously | 39 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 6 | 2.09 | 0.82–5.28 | 0.146 |

|

|

|

| BMI,

kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<18.37 | 20 | 1.57 | 0.69–3.14 | 0.200 |

|

|

|

|

≥18.37 | 25 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| CPS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<20 | 8 | 1.18 | 0.47–2.96 | 0.736 |

|

|

|

|

≥20 | 29 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| DCR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CR/PR/SD | 15 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| PD | 40 | 4.30 | 1.79–10.33 | 0.0011a | 6.96 | 1.80–27.03 | 0.0050a |

| Primary site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tongue | 24 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Otherwise | 21 | 1.34 | 0.67–2.67 | 0.403 |

|

|

|

In the univariate analysis of the same variables for

PFS, ECOG PS, a history of radiotherapy, and DCR showed significant

differences. Specifically, higher ECOG PS was associated with

poorer PFS (HR=4.64; 95% CI=2.01–10.72; P=0.0003), while patients

without prior radiotherapy exhibited poorer PFS (HR=2.57; 95%

CI=1.03–6.44; P=0.043). Additionally, patients with PD as a

response to ICI were associated with poor PFS (HR=5.54; 95%

CI=2.15–14.27; P=0.0004). In the multivariate analysis, male sex

was associated with poorer PFS (HR=3.86; 95% CI=1.32–11.31;

P=0.0138). Furthermore, patients treated with nivolumab

demonstrated poorer PFS (HR=11.75; 95% CI=2.68–51.49; P=0.0011),

and those with PD as a response to ICI were also associated with

poor PFS (HR=9.15; 95% CI=2.38–35.14; P=0.0013). Lastly, patients

with primary tumors located in sites other than the tongue

demonstrated significantly shorter PFS than those with tongue

cancers (HR=4.87; 95% CI=1.51–15.72; P=0.0081) (Table SIV).

Univariate and multivariate analyses

results of pre- and post-treatment factors for OS and PFS

Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate the

association between pre-treatment factors, including age, sex, ECOG

PS, CPS value, ICI combination, prior radiotherapy, BMI, and IBPS

markers, encompassing both pre-treatment and post-treatment values

for NLR, LMR, PNI, PLR, CAR, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and mGPS,

and post-treatment factors, including the presence of irAE and IBPS

markers, with OS and PFS as endpoints (Tables II and SV). Regarding OS, only a higher ECOG PS

was associated with poor OS (HR=2.50; 95% CI=1.17–5.33; P=0.0185),

and no significant differences were observed in pre-IBPS markers in

the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis indicated that

pre-IBPS markers were not associated with prognosis; only sex and

BMI were significantly linked to poor OS (Table II). However, 4–6 weeks after ICI

administration, significant differences were found in NLR, PNI,

CAR, and mGPS in the univariate analysis. Specifically, higher NLR

(HR=2.15; 95% CI=1.07–4.33; P=0.034), lower PNI (HR=4.02; 95%

CI=1.98–8.18; P=0.0002), higher CAR (HR=2.98; 95% CI=1.46–6.06;

P=0.0025), and a mGPS of 1 (HR=2.26; 95% CI=1.02–5.05; P=0.0341)

were associated with poorer OS. Additionally, higher NLR (HR=4.17;

95% CI=1.12–15.57; P=0.0337) and lower PNI (HR=3.92; 95%

CI=1.44–10.64; P=0.0073) were associated with poorer OS in

multivariate analysis.

| Table II.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of pre- and post-treatment factors for OS. |

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of pre- and post-treatment factors for OS.

| A, Pre-treatment

factors |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

| Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Number | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<65 | 20 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65 | 25 | 1.06 | 0.53–2.14 | 0.864 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 29 | 1.46 | 0.70–3.04 | 0.298 | 4.11 | 1.50–11.24 | 0.0059a |

|

Female | 16 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| ECOG PS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 34 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≥1 | 11 | 2.50 | 1.17–5.33 | 0.0185a |

|

|

|

| CPS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<20 | 8 | 1.18 | 0.47–2.96 | 0.736 |

|

|

|

|

≥20 | 29 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| ICI

combination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mono | 33 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| With

chemotherapy | 12 | 1.09 | 0.41–2.86 | 0.865 |

|

|

|

| Radiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Previously | 39 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 6 | 2.09 | 0.82–5.28 | 0.146 |

|

|

|

| BMI,

kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<18.37 | 20 | 1.57 | 0.69–3.14 | 0.200 | 3.33 | 1.22–9.08 | 0.0188a |

|

≥18.37 | 25 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-NLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<4.7 | 16 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥4.7 | 29 | 1.42 | 0.69–2.90 | 0.338 |

|

|

|

| Pre-LMR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1.29 | 32 | 1.73 | 0.88–3.40 | 0.123 |

|

|

|

|

≥1.29 | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-PNI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<43.75 | 30 | 1.31 | 0.69–2.48 | 0.397 |

|

|

|

|

≥43.75 | 15 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-PLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<453.5 | 31 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥453.5 | 14 | 1.18 | 0.62–2.29 | 0.630 |

|

|

|

| Pre-CAR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<6.35 | 43 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥6.35 | 2 | 4.33 | 0.99–18.99 | 0.100 |

|

|

|

| Pre-eosinophil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<120 | 18 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥120 | 27 | 1.21 | 0.65–2.22 | 0.550 |

|

|

|

|

Pre-lymphocytes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<670 | 29 | 1.09 | 0.52–2.31 | 0.822 |

|

|

|

|

≥670 | 16 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B,

Post-treatment factors |

|

|

|

|

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable | Number | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| irAE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 32 | 1.18 | 0.47–2.96 | 0.736 |

|

|

|

| Post-NLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<7.17 | 22 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥7.17 | 23 | 2.15 | 1.07–4.33 | 0.034a | 4.17 | 1.12–15.57 | 0.0337 |

| Post-LMR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1.23 | 15 | 1.40 | 0.66–2.97 | 0.386 |

|

|

|

|

≥1.23 | 30 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Post-PNI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<36.6 | 16 | 4.02 | 1.98–8.18 | 0.0002a | 3.92 | 1.44–10.64 | 0.0073 |

|

≥36.6 | 29 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Post-PLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<221.1 | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥221.1 | 32 | 1.34 | 0.62–2.91 | 0.442 |

|

|

|

| Post-CAR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<0.44 | 22 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥0.44 | 23 | 2.98 | 1.46–6.06 | 0.0025a |

|

|

|

|

Post-eosinophil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<260 | 32 | 1.00 | 0.46–2.20 | 0.991 |

|

|

|

|

≥260 | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post-lymphocytes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<770 | 21 | 1.26 | 0.62–2.56 | 0.529 |

|

|

|

|

≥770 | 25 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Post-mGPS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 13 | Ref. |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 33 | 2.26 | 1.02–5.05 | 0.0341a |

|

|

|

For PFS, no significant differences were observed

prior to ICI administration. Moreover, in univariate analysis,

pre-IBPS markers showed no association with prognosis, though

significant differences were noted in ECOG PS and history of

radiotherapy. In multivariate analysis, pre-IBPS markers were not

associated with prognosis; only sex was significantly correlated

with poorer PFS. However, four to six weeks after ICI

administration, significant differences were observed in NLR, PNI,

and CAR. Higher NLR (HR=2.21; 95% CI=1.14–4.29; P=0.014), lower PNI

(HR=3.25; 95% CI=1.61–6.55; P=0.0015), and higher CAR (HR=2.93; 95%

CI=1.44–5.96; P=0.0029) were associated with poorer PFS. Moreover,

significant differences were observed in NLR, LMR, and PNI in

multivariate analysis. Higher NLR (HR=3.80; 95% CI=1.11–13.02;

P=0.00339), lower PNI (HR=2.96; 95% CI=1.08–8.06; P=0.0342), and

higher LMR (HR=4.02; 95% CI=1.14–14.18; P=0.0304) were associated

with poorer PFS (Table SV).

Univariate analysis results for

prognostic factors for the DCR

A univariate analysis was conducted to evaluate

factors influencing the DCR (Table

SVI). Significant differences were observed in ECOG PS

(P=0.0018), CPS (P=0.007), BMI (P=0.032), and history of

radiotherapy (P=0.027). The relationship between each IBPS item

immediately prior to ICI administration and DCR was analyzed, but

no significant differences were observed for any of the items

(Table SVI). In contrast, when the

relationship between post-treatment IBPS items and DCR was analyzed

four to six weeks after ICI administration, significant differences

were found in post-NLR (P=0.0006), post-LMR (P=0.0065), post-PNI

(P=0.0358), post-PLR (P=0.0396), post-CAR (P=0.0062), and

post-lymphocytes (P=0.0321).

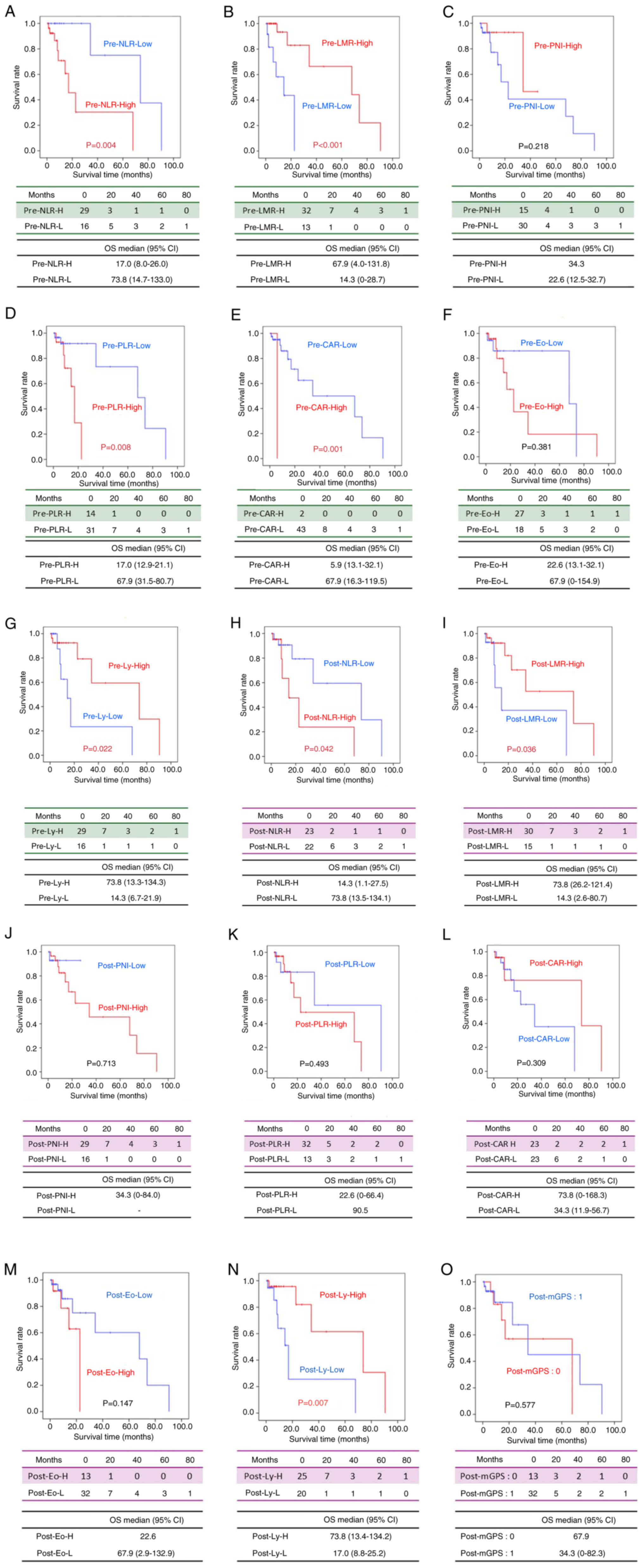

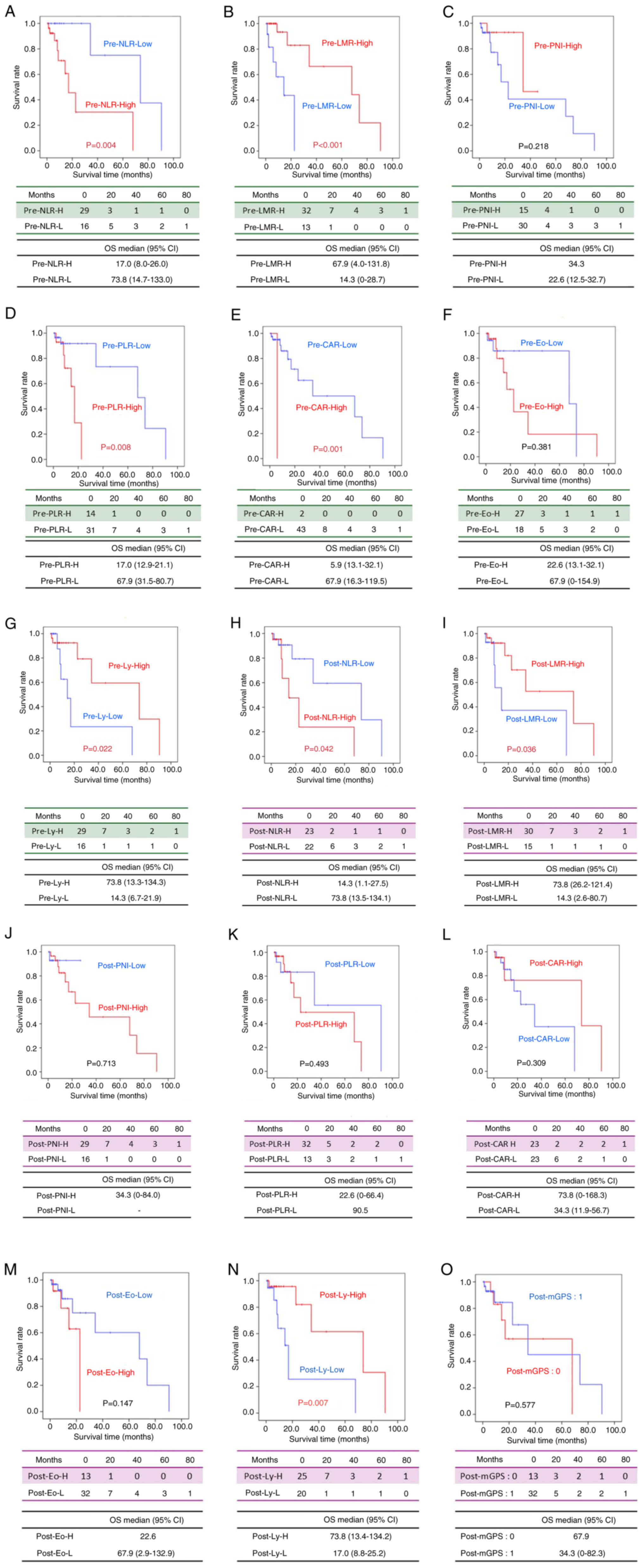

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall

survival according to each IBPS

Using the cutoff values determined from the ROC

curve for each IBPS marker before and after treatment, patients

were divided into two groups: High and Low. Then, Kaplan-Meier

survival curves were generated with OS as the endpoint. Significant

differences in OS were observed for the following markers: pre-NLR

(P=0.004), pre-LMR (P<0.001), pre-PLR (P=0.008), pre-CAR

(P=0.001), pre-lymphocytes (P=0.022), post-NLR (P=0.042), post-LMR

(P=0.036), and post-lymphocytes (P=0.007) (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3.Kaplan-Meier curves of OS according

to each inflammation-based prognostic score. OS according to the

(A) pre-NLR (A), (B) pre-LMR, (C) pre-PNI, (D) pre-PLR, (E)

pre-CAR, (F) pre-Eo, (G) pre-Ly, (H) post-NLR, (I) post-LMR, (J)

post-PNI, (K) post-PLR, (L) post-CAR, (M) post-Eo, (N) post-Ly and

(O) post-mGPS. CAR, C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio; Eo,

eosinophils; LMR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; Ly, lymphocytes;

mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; NLR,

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; OS, overall survival; PLR,

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional

index. |

In the Pre-NLR group, a significant difference in OS

was observed between the Low group (NLR <7.17) and the High

group (NLR ≥7.17) (P=0.042) (Fig.

3A). Similarly, in the Pre-LMR group, the Low group (LMR

<1.29) and the High group (LMR ≥1.29) showed a significant

difference (P<0.001) (Fig. 3B).

However, no significant difference was found in the Pre-PNI group

between the Low group (PNI <43.75) and the High group (PNI

≥43.75) (P=0.218) (Fig. 3C). In the

Pre-PLR group, OS differed significantly between the Low group (PLR

<453.5) and the High group (PLR ≥453.5) (P=0.008) (Fig. 3D). In the Pre-CAR group, a

significant difference was found between the Low group (CAR

<6.35) and the High group (CAR ≥6.35) (P=0.001) (Fig. 3E). Conversely, in the Pre-eosinophil

group, no significant difference in OS was observed between the Low

group (eosinophils <120/µl) and the High group (eosinophils

≥120/µl) (P=0.381) (Fig. 3F). A

significant difference was observed in the Pre-lymphocytes group

between the Low group (lymphocytes <670/µl) and the High group

(lymphocytes ≥670/µl) (P=0.022) (Fig.

3G).

Regarding post-treatment IBPS markers, in the

Post-NLR group, a significant difference in OS was found between

the Low group (NLR <4.7) and the High group (NLR ≥4.7) (P=0.042)

(Fig. 3H). In the Post-LMR group,

the Low group (LMR <1.23) and the High group (LMR ≥1.23) also

showed a significant difference (P=0.036) (Fig. 3I). No significant difference was

found in the Post-PNI group between the Low group (PNI <36.6)

and the High group (PNI ≥36.6) (P=0.713) (Fig. 3J). Similarly, no significant

difference was observed in the Post-PLR group (Low: PLR <221.1,

High: PLR ≥221.1, P=0.493) (Fig.

3K), Post-CAR group (Low: CAR <0.44, High: CAR ≥0.44,

P=0.309) (Fig. 3L), and the

Post-eosinophil group (Low: eosinophils <260/µl, High:

eosinophils ≥260/µl, P=0.147) (Fig.

3M). However, in the Post-lymphocytes group, a significant

difference was observed between the Low group (lymphocytes

<770/µl) and the High group (lymphocytes ≥770/µl) (P=0.007)

(Fig. 3N). No significant

difference was found between the Post-mGPS=0 group and the

Post-mGPS=1 group (P=0.577) (Fig.

3O).

Discussion

In this study, pre-treatment IBPS values did not

show significant associations with OS or PFS. However, post-ICI

treatment values for NLR, PNI, CAR, and mGPS were significantly

correlated with OS. Similarly, post-treatment values for NLR, PNI,

and CAR were significantly associated with PFS. While no

significant association was observed between pre-treatment IBPS

values and the DCR, post-treatment values of NLR, LMR, PNI, PLR,

and CAR were significantly correlated with DCR. Survival analysis

using Kaplan–Meier curves, with cutoff values derived from ROC

analysis, revealed that high NLR, low LMR, high PLR, high CAR, and

low lymphocyte counts prior to ICI administration were associated

with shorter OS. Furthermore, high NLR, low LMR, and low lymphocyte

counts following ICI administration were significantly associated

with shorter OS.

NLR is a marker of systemic inflammation and has

been reported as a prognostic factor in various cancers, including

R/M-OSCC (26–30). In our study, post-ICI NLR

demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy (AUC=0.7696), with

patients exhibiting NLR ≥7.17 having significantly shorter OS than

those with NLR <7.17. An elevated NLR reflects an increase in

neutrophils and a decrease in lymphocytes, suggesting

tumor-associated inflammation and immune suppression (35). Several studies have reported that an

increase in TILs is associated with a favorable prognosis (29,30).

The mechanism underlying the association between elevated NLR and

poor prognosis may be attributed to the inflammatory response, in

which increased neutrophil production promotes tumor proliferation,

invasion, and angiogenesis by inducing the secretion of chemokines

and cytokines, further enhancing tumor-associated inflammation and

suppressing anti-tumor immunity.

CAR is a marker that reflects systemic inflammation

and nutritional status. In patients with a high CAR, elevated

inflammatory cytokines stimulate CRP production while inhibiting

albumin synthesis and accelerating its degradation, signaling the

progression of cachexia (36–38).

In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, high interleukin-6 (IL-6)

expression has been reported, and IL-6 signaling promotes

immunosuppression and tumor progression (39,40).

Local and systemic increases in IL-6 correlate with elevated CRP

concentrations across various cancers (41,42).

In our study, a high CAR was associated with a poor prognosis,

highlighting its potential as an important prognostic marker for

patients with squamous cell carcinoma undergoing chemoradiotherapy

or cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Similarly, mGPS, calculated based on serum albumin

and CRP levels (43), has been

recognized as a prognostic factor for patients with recurrent or

metastatic head and neck cancer (44–48).

Consistent with these findings, our study also demonstrated a

significant association between post-ICI mGPS values and OS.

PLR, another hematological inflammatory marker, is

calculated from platelet and lymphocyte counts. Platelets, similar

to neutrophils, play a key role in inflammation and are often

elevated in patients with chronic inflammation associated with

solid tumors (49,50). Elevated platelet counts have been

linked to cancer progression, making PLR a promising predictive

marker for tumor progression (31,32).

Several studies have suggested that preoperative PLR values are

valuable for prognosis prediction in gastrointestinal cancers, and

more recent research has highlighted its potential for predicting

the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy (14).

PNI, calculated using albumin levels and lymphocyte

counts, reflects nutritional and immunological statuses (51). Previous studies have demonstrated

that pre-ICI PNI is associated with the efficacy of ICIs in

advanced or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer (52). Given the strong relationship between

immune function and nutritional status, low PNI values are

typically associated with poor prognosis. Our study further

corroborates this, demonstrating that low PNI values are associated

with reduced ICI efficacy and worse prognosis.

Notably, in our study, the AUC of nearly all

hematological markers improved after treatment compared with

pre-treatment values. This suggests that post-treatment values may

serve as more reliable prognostic indicators in patients receiving

ICI therapy. Matsuo et al reported that pre-treatment IBPSs

were insufficient for predicting prognosis in patients with

R/M-head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, while post-nivolumab

GPS, NLR, CAR, and eosinophil counts were significantly associated

with survival outcomes (48).

Similarly, Tachinami et al emphasized the importance of

post-treatment IBPS, including NLR, CAR, and PLR, in predicting

prognosis in R/M-OSCC (53). Our

findings are consistent with those of these studies, suggesting

that post-treatment data could be instrumental in predicting

treatment response, enabling the early identification of patients

with poor responses to ICI therapy and allowing for timely

transition to alternative treatment strategies. In this study, the

AUC values of biomarkers such as NLR, PNI, and CAR were below 0.8.

While an AUC above 0.8 is considered to indicate high predictive

accuracy, biomarkers with AUC values between 0.6 and 0.8 can still

be clinically useful (54,55). Especially in patients with R/M-OSCC

undergoing ICI therapy, the tumor immune microenvironment is

complex, and it is challenging to predict prognosis with a single

biomarker alone. In our analysis, even though the AUC values were

moderate, NLR and PNI were found to be independent prognostic

factors in multivariable analysis. Therefore, these markers may

still have clinical value in supporting treatment decisions.

Further improvements in predictive performance may be achieved by

developing composite models that integrate multiple clinical and

biological factors. Recent studies have identified several factors

influencing the efficacy of ICIs, including irAEs, BMI, history of

radiotherapy, ECOG PS, and CPS for PD-L1 expression (38,48,56–60).

In our study, sex and BMI were significant predictors of OS,

whereas sex, ICI type, presence of irAEs, and BMI were significant

predictors of PFS. Additionally, ECOG PS, CPS values, BMI, and

radiotherapy history were significantly associated with DCR.

In addition to hematological biomarkers such as

IBPS, various other factors have been proposed as potential

predictors of response to ICIs. Given the accessibility of

peripheral blood samples, numerous studies have analyzed

circulating cytokine levels, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha,

interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-6, IL-8, and transforming growth factor-β

(TGF-β) (61–63). Elevated IFN-γ levels have been

associated with improved ICI efficacy and toxicity, while higher

baseline levels of IL-8, IL-6, and TGF-β have been identified as

negative predictive markers. However, the extent to which these

circulating factors accurately reflect the tumor microenvironment

remains debatable. Additionally, studies have indicated that a high

neoantigen burden correlates with better treatment outcomes

(64), whereas genetic mutations

(e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor, KRAS, PTEN, TP53)

and dysregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway may impact ICI

response (65–69). Moreover, the use of corticosteroids,

antibiotics, or proton pump inhibitors influences ICI efficacy,

potentially through alterations in gut microbiota composition

(70–72). Future research should aim to

integrate these molecular, clinical, and therapeutic factors to

optimize patient selection and enhance treatment strategies for ICI

therapy.

One major limitation of this study is the small

sample size, particularly after stratification into subgroups. This

limitation is inherent to the retrospective design and the rarity

of patients with R/M-OSCC treated with ICIs at a single

institution. Although the limited cohort size reduced statistical

power, we were still able to identify consistent trends in the

performance of prognostic and predictive biomarkers, especially for

NLR and PNI. These results aligned with those of previous reports

(31,32,48,53)

and suggest that inflammation- and nutrition-based biomarkers may

provide meaningful clinical insights, even in smaller populations.

In addition, potential selection biases related to treatment

history, clinical stage, and histological type were not fully

controlled. Thus, further validation in prospective, multi-center

studies with larger cohorts is essential to confirm our findings

and develop robust predictive models. This study primarily aimed to

identify pre-treatment biomarkers predictive of ICI efficacy in

R/M-OSCC. While we also evaluated post-treatment biomarkers, their

prognostic value seemed limited, likely due to their reflection of

early treatment dynamics rather than baseline tumor biology.

Nevertheless, post-treatment biomarkers assessed 4–6 weeks after

ICI initiation showed potential for early prediction of treatment

efficacy, which may help identify non-responders and guide timely

treatment modifications. As our study did not include a control

group receiving alternative treatments such as chemotherapy or

targeted agents, the generalizability of our findings across

different treatment modalities remains uncertain. Future

prospective, multi-arm studies are warranted to evaluate the

prognostic consistency of these biomarkers and to determine whether

post-treatment markers retain predictive value independent of

treatment type.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that post-ICI

values of NLR, PNI, CAR, and mGPS were significantly associated

with survival outcomes in patients with R/M-OSCC. While

pre-treatment IBPS values did not demonstrate significant

associations with DCR, post-ICI values of NLR, LMR, PNI, PLR, and

CAR exhibited significant correlations. These findings suggest that

hematological biomarkers, including IBPS, may serve as valuable

predictors of ICI treatment efficacy. Early prediction of ICI

response and timely adjustments to treatment may lead to improved

prognosis and the early identification of patients who could

benefit from sequential treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science,

Sports, and Culture of Japan (grant no. 23K09398).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SaY and NI designed the study. SaY and AH organized

the data collection and analyzed the data. SaY, NI, FO, TN, MH, SO,

KK, TA and SoY participated in the treatment of patients with

R/M-OSCC, and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. SaY

and SoY were the main contributors to manuscript writing. SaY, NI

and SoY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles of The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the

Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University (approval no. E2024-0196).

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics

Committee owing to the retrospective design of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

5-FU

|

5-fluorouracil

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

BMI

|

body mass index

|

|

CAR

|

C-reactive protein-to-albumin

ratio

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

|

CPS

|

combined positive score

|

|

CR

|

complete response

|

|

CRP

|

C-reactive protein

|

|

DCR

|

disease control rate

|

|

ECOG PS

|

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Performance Status

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

IBPS

|

inflammation-based prognostic

score

|

|

ICIs

|

immune checkpoint inhibitors

|

|

IFN-γ

|

interferon-γ

|

|

IL

|

interleukin

|

|

irAEs

|

immune-related adverse events

|

|

LMR

|

lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

|

|

mGPS

|

modified Glasgow Prognostic Score

|

|

NLR

|

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

OSCC

|

oral squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

PLR

|

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

|

|

PNI

|

prognostic nutritional index

|

|

PR

|

partial response

|

|

R/M-OSCC

|

recurrent or metastatic oral squamous

cell carcinoma

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

SD

|

stable disease

|

|

TGF-β

|

transforming growth factor-β

|

References

|

1

|

Werning JW: Oral cancer: Diagnosis,

management, and rehabilitation. 1st Edition. Thieme Medical

Publishing Group; New York, USA: pp. 12007

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Olson CM, Burda BU, Beil T and Whitlock

EP: Screening for oral cancer: A targeted evidence update for the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Rockville (MD): Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013

|

|

4

|

Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, Remenar

E, Kawecki A, Rottey S, Erfan J, Zabolotnyy D, Kienzer HR, Cupissol

D, et al: Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and

neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 359:1116–1127. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J,

Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington K, Kasper S, Vokes EE,

Even C, et al: Nivolumab for recurrent Squamous-cell carcinoma of

the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 375:1856–1867. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C,

Dinis J, Licitra L, Ahn MJ, Soria A, Machiels JP, Mach N, Mehra R,

et al: Pembrolizumab versus standard therapy for recurrent or

metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-048): A

randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 393:156–167. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hanna GJ, Schoenfeld JD and Ferris RL:

Immunotherapy approaches in head and neck cancer: Current and

emerging strategies. Front Immunol. 13:8409042022.

|

|

8

|

Zhang P, Su DM, Liang M and Fu J:

Chemopreventive agents induce programmed death-1-ligand 1 (PD-L1)

surface expression in breast cancer cells and promote

PD-L1-mediated T cell apoptosis. Mol Immunol. 45:1470–1476. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu

VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA and Kinzler KW: Cancer genome landscapes.

Science. 339:1546–1558. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C and

Galon J: The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical

outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:298–306. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS,

Angerson WJ and Dunlop DJ: Evaluation of cumulative prognostic

scores based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with

inoperable Non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 89:1028–1030.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Iseki Y,

Hirakawa K and Ohira M: The significance of the C-reactive protein

to albumin ratio as a marker for predicting survival and monitoring

chemotherapeutic effectiveness in patients with unresectable

metastatic colorectal cancer. Springerplus. 5:17982016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

An X, Ding PR, Li YH, Wang FH, Shi YX,

Wang ZQ, He YJ, Xu RH and Jiang WQ: Elevated neutrophil to

lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in advanced pancreatic cancer.

Biomarkers. 15:516–522. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu Y, Li C, Zhao J, Yang L, Liu F, Zheng

H, Wang Z and Xu Y: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios predict chemotherapy outcomes and

prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous liver

metastasis. World J Surg Oncol. 14:2892016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang L, Huang Y, Zhou L, Dai Y and Hu G:

High pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of

poor survival prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 41:1525–1535. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rassouli A, Saliba J, Castano R, Hier M

and Zeitouni AG: Systemic inflammatory markers as independent

prognosticators of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head

Neck. 37:103–110. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Takenaka Y, Oya R, Kitamiura T, Ashida N,

Shimizu K, Takemura K, Yamamoto Y and Uno A: Platelet count and

platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers for head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma: Meta-analysis. Head Neck. 40:2714–2723.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bardash Y, Olson C, Herman W, Khaymovich

J, Costantino P and Tham T: Platelet-lymphocyte ratio as a

predictor of prognosis in head and neck cancer: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Oncol Res Treat. 42:665–677. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nishikawa D, Suzuki H, Koide Y, Beppu S,

Kadowaki S, Sone M and Hanai N: Prognostic markers in head and neck

cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Cancers (Basel).

10:4662018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mohammed FF, Poon I, Zhang L, Elliott L,

Hodson ID, Sagar SM and Wright J: Acute-phase response reactants as

objective biomarkers of radiation-induced mucositis in head and

neck cancer. Head Neck. 34:985–993. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kano S, Homma A, Hatakeyama H, Mizumachi

T, Sakashita T, Kakizaki T and Fukuda S: Pretreatment

lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as an independent prognostic factor

for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 39:247–253. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ikeguchi M: Glasgow prognostic score and

neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio are good prognostic indicators after

radical neck dissection for advanced squamous cell carcinoma in the

hypopharynx. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 401:861–866. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Turri-Zanoni M, Salzano G, Lambertoni A,

Giovannardi M, Karligkiotis A, Battaglia P and Castelnuovo P:

Prognostic value of pretreatment peripheral blood markers in

paranasal sinus cancer: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck. 39:730–736. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mikoshiba T, Ozawa H, Saito S, Ikari Y,

Nakahara N, Ito F, Watanabe Y, Sekimizu M, Imanishi Y and Ogawa K:

Usefulness of hematological inflammatory markers in predicting

severe side-effects from induction chemotherapy in head and neck

cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 39:3059–3065. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yasumatsu R, Wakasaki T, Hashimoto K,

Nakashima K, Manako T, Taura M, Matsuo M and Nakagawa T: Monitoring

the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be useful for predicting the

anticancer effect of nivolumab in recurrent or metastatic head and

neck cancer. Head Neck. 41:2610–2618. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ferrucci PF, Ascierto PA, Pigozzo J, Del

Vecchio M, Maio M, Antonini Cappellini GC, Guidoboni M, Queirolo P,

Savoia P, Mandalà M, et al: Baseline neutrophils and derived

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: Prognostic relevance in metastatic

melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 27:732–738.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kiriu T, Yamamoto M, Nagano T, Hazama D,

Sekiya R, Katsurada M, Tamura D, Tachihara M, Kobayashi K and

Nishimura Y: The time-series behavior of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio is useful as a predictive marker in non-small cell lung

cancer. PLoS One. 13:e01930182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sacdalan DB, Lucero JA and Sacdalan DL:

Prognostic utility of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in

patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review and

meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 11:955–965. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, Flatz L, Born

D, Jochum W, Templeton AJ and Früh M: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic

markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated

with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 111:176–181. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bagley SJ, Kothari S, Aggarwal C, Bauml

JM, Alley EW, Evans TL, Kosteva JA, Ciunci CA, Gabriel PE, Thompson

JC, et al: Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker

of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 106:1–7. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jain S, Harris J and Ware J: Platelets:

Linking hemostasis and cancer. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

30:2362–2367. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nieswandt B, Hafner M, Echtenacher B and

Männel DN: Lysis of tumor cells by natural killer cells in mice is

impeded by platelets. Cancer Res. 59:1295–1300. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK and Wittekind

C: TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8th Edition.

Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2016

|

|

34

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Granot Z and Jablonska J: Distinct

functions of neutrophil in cancer and its regulation. Mediators

Inflamm. 2015:7010672015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ferris RL: Immunology and immunotherapy of

head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 33:3293–3304. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pettersen K, Andersen S, Degen S, Tadini

V, Grosjean J, Hatakeyama S, Tesfahun AN, Moestue S, Kim J, Nonstad

U, et al: Cancer cachexia associates with a systemic

autophagy-inducing activity mimicked by cancer cell-derived IL-6

trans-signaling. Sci Rep. 7:20462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Tanoue K, Tamura S, Kusaba H, Shinohara Y,

Ito M, Tsuchihashi K, Shirakawa T, Otsuka T, Ohmura H, Isobe T, et

al: Predictive impact of C-reactive protein to albumin ratio for

recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

receiving nivolumab. Sci Rep. 11:27412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Duffy SA, Taylor JM, Terrell JE, Islam M,

Li Y, Fowler KE, Wolf GT and Teknos TN: Interleukin-6 predicts

recurrence and survival among head and neck cancer patients.

Cancer. 113:750–757. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Riedel F, Zaiss I, Herzog D, Götte K, Naim

R and Hörmann K: Serum levels of interleukin-6 in patients with

primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res.

25:2761–2765. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ravishankaran P and Karunanithi R:

Clinical significance of preoperative serum interleukin-6 and

C-reactive protein level in breast cancer patients. World J Surg

Oncol. 9:182011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

McKeown DJ, Brown DJ, Kelly A, Wallace AM

and McMillan DC: The relationship between circulating

concentrations of C-reactive protein, inflammatory cytokines and

cytokine receptors in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Br

J Cancer. 91:1993–1995. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Inoue Y, Iwata T, Okugawa Y, Kawamoto A,

Hiro J, Toiyama Y, Tanaka K, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Miki C and Kusunoki

M: Prognostic significance of a systemic inflammatory response in

patients undergoing multimodality therapy for advanced colorectal

cancer. Oncology. 84:100–107. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Matsuki T, Okamoto I, Fushimi C, Sawabe M,

Kawakita D, Sato H, Tsukahara K, Kondo T, Okada T, Tada Y, et al:

Hematological predictive markers for recurrent or metastatic

squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck treated with

nivolumab: A multicenter study of 88 patients. Cancer Med.

9:5015–5024. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ueki Y, Takahashi T, Ota H, Shodo R,

Yamazaki K and Horii A: Predicting the treatment outcome of

nivolumab in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma: Prognostic value of combined performance status and

modified Glasgow prognostic score. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

277:2341–2347. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Niwa K, Kawakita D, Nagao T, Takahashi H,

Saotome T, Okazaki M, Yamazaki K, Okamoto I, Hirai H, Saigusa N, et

al: Multicentre, retrospective study of the efficacy and safety of

nivolumab for recurrent and metastatic salivary gland carcinoma.

Sci Rep. 10:169882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Minohara K, Matoba T, Kawakita D, Takano

G, Oguri K, Murashima A, Nakai K, Iwaki S, Hojo W, Matsumura A, et

al: Novel Prognostic Score for recurrent or metastatic head and

neck cancer patients treated with Nivolumab. Sci Rep. 11:169922021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Matsuo M, Yasumatsu R, Masuda M, Toh S,

Wakasaki T, Hashimoto K, Jiromaru R, Manako T and Nakagawa T:

Inflammation-based prognostic score as a prognostic biomarker in

patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab therapy. In Vivo. 36:907–917.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wagner DD: New links between inflammation

and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 25:1321–1324. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Stone RL, Nick AM, McNeish IA, Balkwill F,

Han HD, Bottsford-Miller J, Rupairmoole R, Armaiz-Pena GN, Pecot

CV, Coward J, et al: Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian

cancer. N Engl J Med. 366:610–618. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang L, Ma W, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Wang K, Hu

B and Wang W: Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic

biomarker for gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 14:12199292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shoji F, Takeoka H, Kozuma Y, Toyokawa G,

Yamazaki K, Ichiki M and Takeo S: Pretreatment prognostic

nutritional index as a novel biomarker in non-small cell lung

cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung

Cancer. 136:45–51. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Tachinami H, Tomihara K, Yamada SI, Ikeda

A, Imaue S, Hirai H, Nakai H, Sonoda T, Kurohara K, Yoshioka Y, et

al: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an early marker of outcomes

in patients with recurrent oral squamous cell carcinoma treated

with nivolumab. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 61:320–326. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhou XH, Obuchowski NA and McClish DK:

Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. 2nd Edition. John Wiley

& Sons; New Jersey: 2011, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, Zehir A, Berger

MF, Seshan VE, Chan TA and Morris LGT: Response rates to anti-PD-1

immunotherapy in microsatellite-stable solid tumors with 10 or more

mutations per megabase. JAMA Oncol. 7:739–743. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Iwasa YI, Kitoh R, Yokota Y, Hori K,

Kasuga M, Kobayashi T, Kanda S and Takumi Y: Post-treatment

neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic factor in head and neck

cancers treated with nivolumab. Cancer Diagn Progn. 4:182–188.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K,

Veruttipong D, Goldman JW, Formenti SC, Garon EB and Lee P:

Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of

pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: A

secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:895–903. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Öjlert ÅK, Nebdal D, Lund-Iversen M,

Åstrøm Ellefsen R, Brustugun OT, Gran JM, Halvorsen AR and Helland

Å: Immune checkpoint blockade in the treatment of advanced

non-small cell lung cancer-predictors of response and impact of

previous radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 60:149–156. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Shankar B, Zhang J, Naqash AR, Forde PM,

Feliciano JL, Marrone KA, Ettinger DS, Hann CL, Brahmer JR,

Ricciuti B, et al: Multisystem immune-related adverse events

associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of

non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 6:1952–1956. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Hsiehchen D, Naqash AR, Espinoza M, Von

Itzstein MS, Cortellini A, Ricciuti B, Owen DH, Laharwal M, Toi Y,

Burke M, et al: Association between immune-related adverse event

timing and treatment outcomes. Oncoimmunology. 11:20171622022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang M, Zhai X, Li J, Guan J, Xu S, Li Y

and Zhu H: The role of cytokines in predicting the response and

adverse events related to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front

Immunol. 12:6703912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M,

Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, Park K, Smith D,

Artal-Cortes A, Lewanski C, et al: Atezolizumab versus docetaxel

for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer

(POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled

trial. Lancet. 387:1837–1846. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Sanmamed MF, Perez-Gracia JL, Schalper KA,

Fusco JP, Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Oñate C, Perez G, Alfaro

C, Martín-Algarra S, et al: Changes in serum interleukin-8 (IL-8)

levels reflect and predict response to anti-PD-1 treatment in

melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol.

28:1988–1995. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R,

Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, Birkbak

NJ, Hiley CT, et al: Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell

immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade.

Science. 351:1463–1469. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Miao D, Margolis CA, Vokes NI, Liu D,

Taylor-Weiner A, Wankowicz SM, Adeegbe D, Keliher D, Schilling B,

Tracy A, et al: Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint

blockade in microsatellite-stable solid tumors. Nat Genet.

50:1271–1281. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Giroux Leprieur E, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z,

Takam Kamga P, Costantini A, Julie C, Corjon A, Dumenil C, Dumoulin

J, Giraud V, Labrune S, et al: Sequential ctDNA whole-exome

sequencing in advanced lung adenocarcinoma with initial durable

tumor response on immune checkpoint inhibitor and late progression.

J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0005272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Guibert N, Jones G, Beeler JF, Plagnol V,

Morris C, Mourlanette J, Delaunay M, Keller L, Rouquette I, Favre

G, et al: Targeted sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA to predict

response to PD1 inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung Cancer. 137:1–6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhang W, Li Y, Lyu J, Shi F, Kong Y, Sheng

C, Wang S and Wang Q: An aging-related signature predicts favorable

outcome and immunogenicity in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci.

113:891–903. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR,

Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al:

Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:1627–1639. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, Rizvi H,

Auclin E, Ni A, Martínez-Bernal G, Ferrara R, Lai WV, Hendriks LEL,

et al: Impact of baseline steroids on efficacy of programmed cell

death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 36:2872–2878. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Liu C, Guo H, Mao H, Tong J, Yang M and

Yan X: An up-to-date investigation into the correlation between

proton pump inhibitor use and the clinical efficacy of immune

checkpoint inhibitors in advanced solid cancers: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 12:7532342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ochi N, Ichihara E, Takigawa N, Harada D,

Inoue K, Shibayama T, Hosokawa S, Kishino D, Harita S, Oda N, et

al: The effects of antibiotics on the efficacy of immune checkpoint

inhibitors in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer differ based

on PD-L1 expression. Eur J Cancer. 149:73–81. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|