Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) has a poor

prognosis, ranking 11th in overall mortality, 7th among men and

17th among women, worldwide (1).

Treatment options include surgery, endoscopic submucosal

dissection, chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy (CRT), and heavy ion

therapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and

5-fluorouracil (CF) plus docetaxel (DCF) had a better prognosis

than neoadjuvant CRT in patients with locally advanced, resectable

ESCC (2). One of the reasons for

the worse prognosis of neoadjuvant CRT might be the side effects

due to CRT, despite CRT having a high pathological complete

response (pCR) rate and few local recurrences (2). Therefore, methods to predict the CRT

treatment response prior to treatment in ESCC need to be developed,

would be clinically useful, and could be effective in planning

personalized treatments for ESCC patients.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake is

elevated in malignant tumor cells. Therefore, FDG-positron emission

tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT), which can visualize

FDG accumulation, has been used to identify malignant tumors. In

clinical practice, FDG-PET/CT is used to assess the presence and

location of distant metastases. The most commonly used FDG-PET/CT

parameter is the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), which

represents tissue metabolism. Moreover, SUVmax has been used to

determine treatment response. Previous studies reported that

post-treatment PET parameters can predict patients who will respond

to treatment. Murakami et al (3) reported that comparing post-treatment

PET parameters with pre-treatment PET parameters contributes to

confirming the prognosis of patients with ESCC treated with

neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Swisher et al (4) reported that post-treatment SUVmax was

an independent predictor of survival in patients with ESCC treated

with CRT. To the best of our knowledge, pretreatment PET parameters

have not been able to predict the prognosis or treatment response

of patients with ESCC.

Recently, whole-body continuous imaging using flow

motion has become possible allowing for the measurement of FDG

dynamics. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the

use of dynamic whole-body PET/CT (DW-PET/CT) for esophageal cancer

imaging. In this study, we enrolled ESCC patients who underwent CRT

and investigated the relationship between pretreatment

DW-PET/CT-derived parameters, such as the Patlak slope (PS) and

Patlak intercept (PI), and treatment response.

Highly proliferative cells exhibit greater

radiosensitivity (5). Additionally,

in malignant tumors, cells proliferate rapidly, metabolic activity

is heightened, and glycolysis is upregulated (6,7). Under

such conditions, the PS, which reflects the metabolic rate, is

expected to be elevated. Since the PS reflects active cell

division, we hypothesized that a higher PS may indicate patients

more likely to have favorable response to CRT. In addition, the PI

is considered a parameter reflecting perfusion (8). During CRT resistance, reduced blood

perfusion within the tumor leads to hypoxia, low pH, and decreased

drug delivery, all of which contribute to treatment resistance

(9,10). Thus, we hypothesize that a high PI

would indicate stable perfusion and potentially reduce treatment

resistance and improve CRT efficacy.

Materials and methods

Patient population

This retrospective study included patients with

pathologically proven ESCC who underwent pretreatment DW-PET/CT

followed by CRT between August 2021 and May 2024. We identified

fifty-nine ESCC patients who received CRT after DW-PET/CT at our

institute during the study period (Table I). Three patients were excluded

because their tumors were too small to identify on PET/CT images.

Finally, 56 patients were eligible for this study. The subjects

included 44 men and 12 women with a mean age of 73.0 years (range

28–90 years). The clinical stage was determined by gastrointestinal

endoscopy, barium esophagography, chest and abdominal computed

tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and

18F-FDG-PET, based on the 12th Edition of the Japanese

Classification of Esophageal Cancer (4,11).

Clinicopathological data including age, sex, clinical TNM stage,

and pathological findings were collected from electronic medical

records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

at Chiba University Hospital (IRB reference number: HK202302-10;

Chiba, Japan). Written informed consent was obtained for all

examinations and treatments, including DW-PET/CT. However, with

regard to consent for participation in this study, the opt-out

approach was used because of the retrospective design. The study

details were made publicly available on websites or at locations

accessible to potential participants, and all participants were

given the freedom to opt out of the study.

| Table I.Characteristics of patients treated

with chemoradiotherapy (n=56). |

Table I.

Characteristics of patients treated

with chemoradiotherapy (n=56).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 73 (28–90) |

| Sex,

Male/Female | 44/12 |

| Tumor location,

Ce/Ut/Mt/Lt | 12/9/18/17 |

| Clinical T status,

T1/T2/T3/T4 | 6/4/12/34 |

| Clinical N status,

N-/N+ | 13/43 |

| Clinical M status,

M0/M1 | 46/10 |

| Clinical stage,

I/II/III/IV | 5/6/11/34 |

| Surgery, +/- | 13/43 |

| SCC histology | 56 |

| Median

neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (range) | 3.1 (1.3–11.3) |

| Median prognostic

nutritional index (range) | 48.1

(33.6–57.9) |

| CEA,

≤5.0/>5.0 | 44/12 |

| SCC-associated

antigen, ≤1.5/>1.5 | 26/30 |

| CYFRA,

≤3.5/>3.5/not available | 50/5/1 |

| Serum p53

antibodies, ≤10/>10/not available | 46/8/2 |

| Chemotherapy,

CF/FOLFOX | 52/4 |

| Therapeutic

response, Responder/Non- | 38/18 |

| Responder |

|

| Median tumor

length, mm (range) | 50.5 (15–110) |

| Median tumor

contraction rate, % (range) | 33.33 (−14-70) |

Treatment plan and response

evaluation

CRT consisted of two cycles of CF [800

mg/m2 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in a continuous infusion for

5 days and 80 mg/m2 cisplatin on day 1] or two cycles of

FOLFOX (400 mg/m2 5-FU, 85 mg/m2 oxaliplatin,

and 200 mg/m2 levofolinate on day 1, followed by 1,600

mg/m2 5-FU in a continuous infusion for 2 days). All

patients received 2 Gy × 15–30 fractions of radiation therapy.

Re-evaluation of the primary tumor was performed by CT, endoscopy,

and gastrography 3 to 4 weeks after the completion of CRT.

Endoscopic ultrasound and PET were not always used for response

evaluation. The treatment response was evaluated according to the

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (11). Complete response (CR) was defined as

the disappearance of the target lesion and as the disappearance of

endoscopically suggestive neoplastic lesions and the absence of

histological evidence of cancer on biopsy. Partial response (PR)

was a reduction in the target lesion by 30% or more, progressive

disease (PD) was an increase in the target lesion by 20% or more,

and stable disease (SD) was defined as no reduction equivalent to

PR and no increase equivalent to PD. We calculated the response of

the target lesion according to the thickness of the tumor. We

targeted the main lesion because we wanted to examine the effects

of CRT on the main lesion. In this study, patients who showed a

response, CR or PR, were categorized as clinical responders. The

remaining patients with either SD or PD were categorized as

clinical non-responders. We also calculated the contraction rate of

the main tumor during CRT. The equation for this contraction rate

is as follows: Tumor contraction rate (%)=(Tumor thickness before

treatment-Tumor thickness after treatment)/Tumor thickness before

treatment ×100.

DW-PET/CT protocol

The study participants were scanned on a Siemens

Biograph mCT Flow (Siemens Medical Solutions) with a 221-cm axial

field of view. The crista was a lutetium oxyorthosilicate (LSO),

the gantry opening diameter was 78 mm, the bismuth germanate

detectors were set for 300 sec, the LSO for 40 ns, and the

semiconductor for 214 ps. Patients were asked not to eat for 6 h

before imaging, and their blood glucose levels were measured

immediately before scanning. The blood sugar levels of all patients

were below 150 mg/dl at the time of the PET study. FDG was

administered with an auto-dispensing injector (UG-05; Universal

GIKEN). First, the static whole-body images were acquired 60 min

after the injection of FDG (3.7 MBq/kg [max 370 MBq]). DW-PET/CT

image series were acquired every 5 min starting 60 min after the

injection of FDG (65, 70, 75, and 80 min) using

continuous-bed-motion technique (Flow motion technique) (12,13).

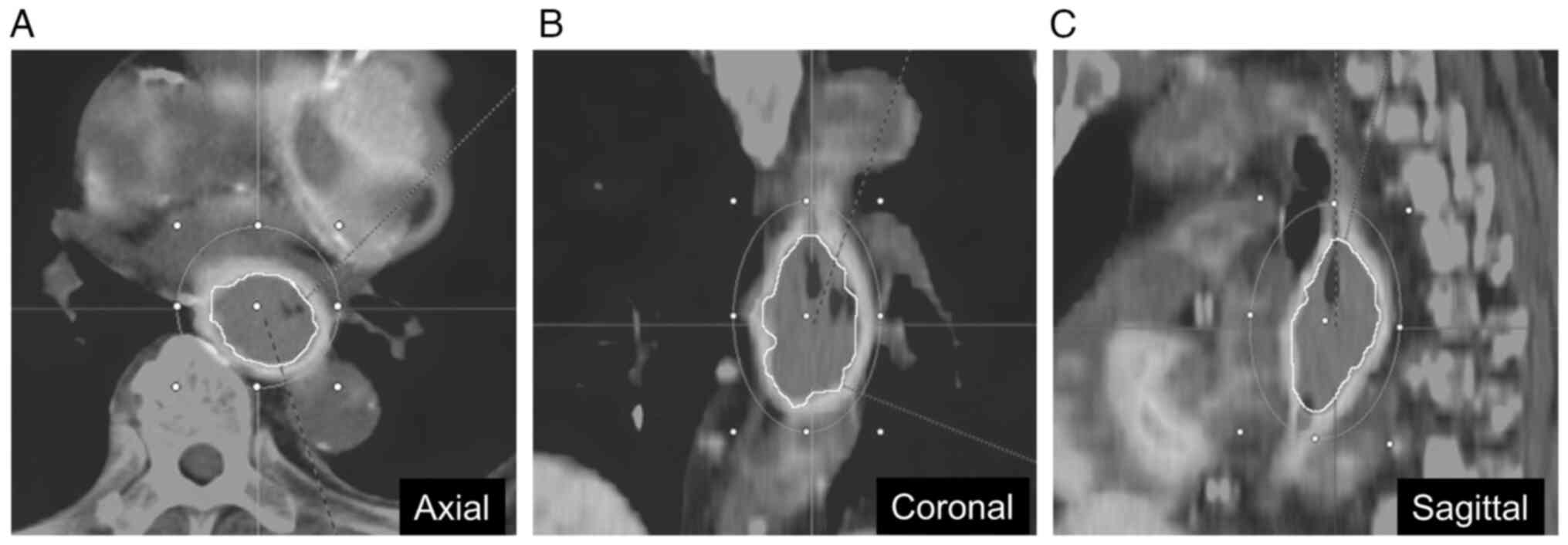

DW-PET/CT analysis

DW-PET/CT analysis was performed using the syngo.via

software. Using this software, kinetic analysis of FDG was

performed according to the compartment model. PS and PI were

calculated as DW-PET/CT parameters based on four whole-body PET/CT

image series acquired at every 5 min starting 60 min (65, 70, 75,

and 80 min) after the injection of FDG, and DW-PET/CT images of the

PS and PI were generated. PS was presumed to represent the absolute

metabolic rate of FDG, while PI represented the percentage of blood

concentration and represents perfusion within the tissue (14–16). A

spherical volume of interest (VOI) was placed over the primary

tumor with the highest glucose uptake on the trans-axial PET images

acquired at 60 min after the injection of FDG, and the tumor lesion

was automatically delineated by using threshold of 40% of SUVmax

within the VOI (Fig. 1) (13,17).

In this automatically defined tumor area, the SUVmax and mean PS

and PI values were calculated. This analysis was performed by a

single observer (M.I. with 3 years of experience in PET and CT

interpretation) supervised by an experienced gastroenterologist

(Y.K. with 10 years of experience in PET and CT

interpretation).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the

JMP Pro software (version 17.0; SAS Institute, Inc.). Differences

were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. The

Mann-Whitney U test was applied for comparison of DW-PET/CT

parameters between responder and non-responder groups. Correlations

between DW-PET/CT parameters and tumor contraction rate during CRT

was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficients. Area

under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analyses

were performed to assess the predictive value of DW-PET/CT

parameters for predicting treatment responders. Logistic regression

analysis was also performed to improve the AUC.

In addition to evaluating the predictive accuracy of

the PS and PI using AUC analyses, we evaluated the characteristics

of misclassified cases. Categorical variables were analyzed using

Fisher's exact test; continuous variables were assessed using the

Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

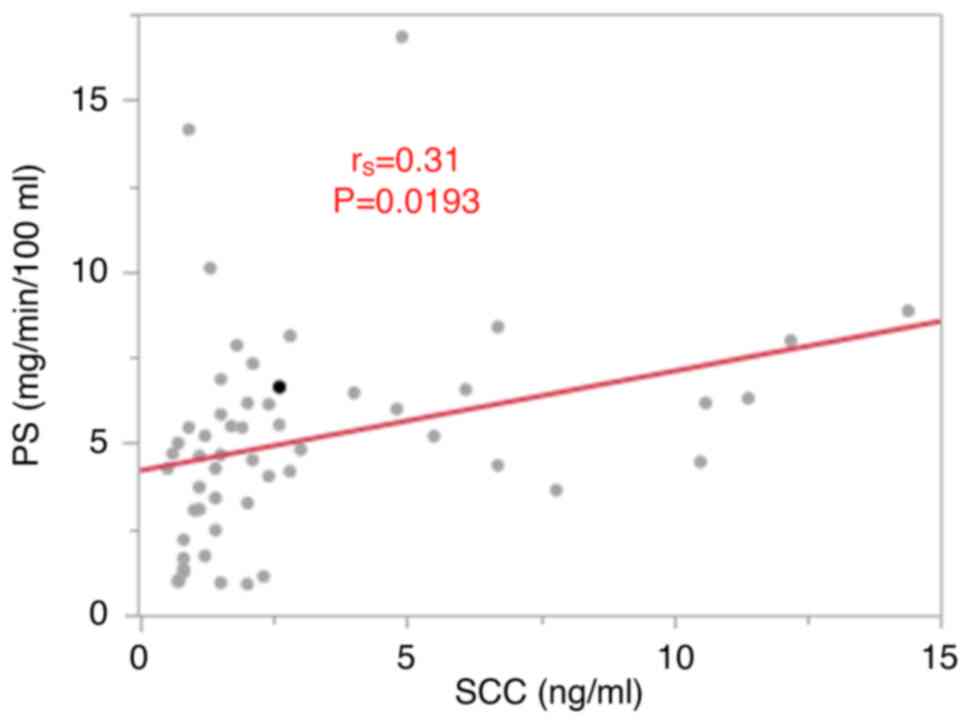

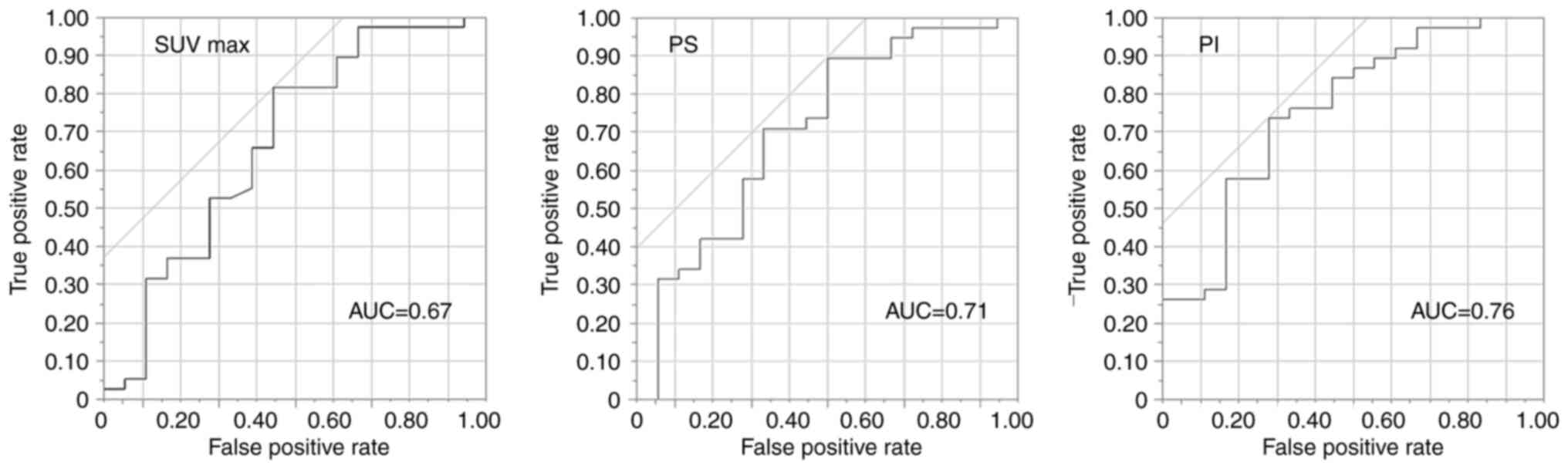

Relationship between DW-PET/CT-derived

parameters and treatment response

We compared DW-PET/CT parameters between treatment

responders and non-responders. Tumors of responders showed

significantly higher SUVmax, PS, and PI than non-responders

(P=0.04, P=0.0012, and P=0.0018, respectively; Table II). Next, we investigated the

relationships between the PS, PI, and clinical parameters. A weak

correlation was observed between squamous cell carcinoma-associated

antigen levels and PS (rs=0.31, P=0.0193; Fig. 2). No correlations were found between

SUVmax or PI and clinical parameters. Additionally, the PS did not

correlate with the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, prognostic

nutritional index, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, cytokeratin

fragment levels, or serum p53 antibodies. The PS and PI showed good

performances in predicting treatment response with AUCs of 0.71 and

0.76, whereas the SUVmax showed a poor performance with an AUC of

0.67 (Fig. 3). For the PS, when the

cut-off point was set at 3.26 (calculated by the Youden Index

method), the sensitivity was 89.5%, specificity was 50.0%, and

accuracy was 76.8% for the prediction of patients who showed good

response to CRT. For the PI, when the cut-off point was set at

71.37 (calculated by Youden Index method), the sensitivity was

73.7%, specificity was 72.2%, and accuracy was 73.2% for the

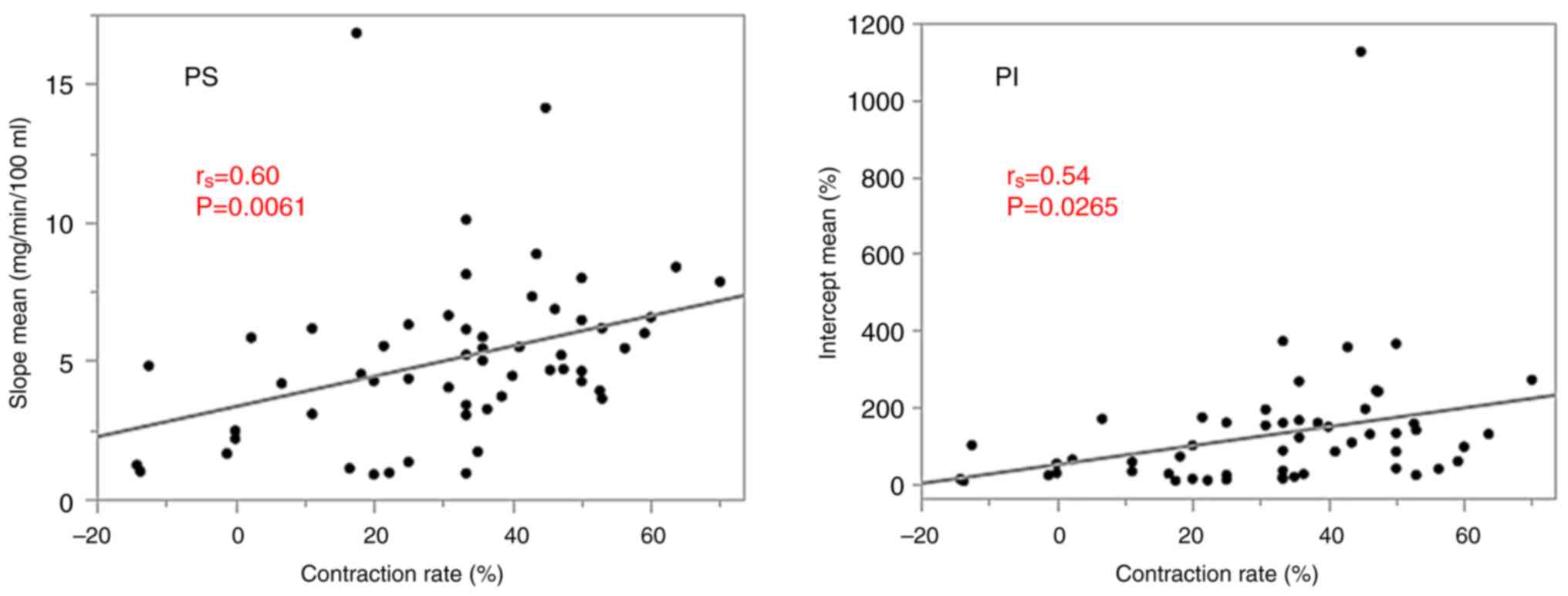

prediction of patients who showed good response to CRT. The tumor

contraction rate during CRT showed significant positive

correlations with the PS and PI (rs=0.60, P=0.0061 and

rs=0.54, P=0.0265, respectively; Fig. 4).

| Table II.Relationship between therapeutic

responders and SUVmax, Patlak slope and Patlak intercept in

patients with esophageal cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. |

Table II.

Relationship between therapeutic

responders and SUVmax, Patlak slope and Patlak intercept in

patients with esophageal cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy.

| Measured

parameter | Responder

(n=38) | Non-responder

(n=18) | P-value |

|---|

| SUVmax | 17.57±8.22 | 12.86±8.38 | 0.04 |

| Patlak slope,

mg/min/100 ml | 5.55±2.51 | 4.10±3.72 | 0.0012 |

| Patlak intercept,

% | 161.42±188.30 | 57.96±58.03 | 0.0018 |

To evaluate the predictive accuracy of the PS and PI

using AUC analyses, we evaluated the characteristics of

misclassified cases. No significant differences in clinical or

imaging features were observed between the PS true-positive and

false-positive groups. However, when comparing the PS true-positive

and false-negative groups, the false-negative group was

characterized by less advanced T and N classifications and overall

stage (P<0.0001, P=0.0237, and P=0.0002, respectively), as well

as lower squamous cell carcinoma-associated antigen levels

(P=0.0360). Similarly, no significant differences were found

between the PI true-positive and false-positive groups. In

contrast, the PI false-negative group showed significantly less

advanced T classification and overall stage compared to the

true-positive group (P=0.0221 and P=0.0479, respectively). These

findings suggest that cases with less advanced T classification and

overall disease stage are more likely to result in false-negative

predictions for both PS and PI.

To improve the AUCs for PS and PI, logistic

regression analysis was performed; however, the AUCs showed no

improvement. Logistic regression was conducted using the following

explanatory variables: PS≥3.26 vs. PS<3.26 and PI≥71.37 vs.

PI<71.37. Individually, neither PS (OR=3.38, 95% CI: 0.63–21.00,

P=0.16) nor PI (OR=3.73, 95% CI: 0.74–18.83, P=0.11) were

significant indicators of the responder status. However, a combined

model incorporating both PS and PI significantly distinguished

responders from non-responders (log-likelihood ratio=6.37,

χ2=12.75, degree of freedom=2, P=0.0017,

R2=0.18, AIC=64.04). The ROC analysis yielded an AUC of

0.76. When PS and PI were treated as continuous variables, the

overall model test yielded the following parameters: log-likelihood

ratio=5.74, χ2=11.48, degree of freedom=2, P=0.0032,

R2=0.16, and AIC=65.31. The corresponding ROC curve

analysis showed an AUC of 0.75.

Discussion

Patients with ESCC have a poor prognosis and are

treated using a multidisciplinary approach that combines various

therapies. The JCOG1109 trial (2)

showed that postoperative DCF therapy has a better prognosis than

CF or CRT in terms of overall survival. In contrast, the pCR rates

for preoperative DCF therapy and CRT with CF therapy were 18.6 and

36.7%, respectively. DCF also carries a higher risk of adverse

events such as myelosuppression and neutropenia, with 42–90% of

patients developing grade 3 or higher neutropenia and 10–39%

developing febrile neutropenia (18–20).

These data indicate the presence of a population for which CRT is

suitable. Determining which cases are suitable for CRT can be

useful for treatment decision-making. The results of our study

indicate that, in ESCC patients undergoing CRT, those with higher

measured PS and PI had better responses. Similarly, the tumor

contraction rate correlated with a higher PS. The PS measured using

FDG-PET may be promising imaging biomarker for treatment selection

in patients with ESCC.

Various methods have been proposed to predict CRT

efficacy, including analyses of genes, RNA, proteins, metabolites,

the tumor microenvironment, and the microbiome. Among these,

imaging techniques offer the distinct advantage of being

non-invasive. In this study, we focused on imaging biomarkers

obtained during baseline clinical assessments.

Several studies have reported on the use of various

imaging modalities, such as CT, MRI, and PET, in assessing the

response of esophageal cancer to CRT. During CT perfusion imaging,

blood flow has been shown to correlate with treatment response and

overall survival (21,22). Other CT-derived parameters, such as

tumor thickness (23) and radiomic

features like LLLEnergy (24), have

also been reported to be associated with treatment response and

overall survival. Among MRI-derived parameters, the apparent

diffusion coefficient has been reported to correlate with survival

outcomes (25,26). Ktrans has been associated with pCR

(27,28), and has also been shown to be useful

for predicting response (29).

Additionally, histogram analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient

values has been reported to correlate with both pCR and

recurrence-free survival (30).

The advantages of PET imaging include not needing

contrast agents, its applicability in patients with metallic

implants, and a lower susceptibility to motion artifacts caused by

cardiac activity. van der Aa et al (31) reported that the SUVmax, which has

been widely used in clinical practice, is not predictive of pCR. In

our study, however, we demonstrated the potential utility of

alternative PET parameters, PS and PI, in predicting treatment

response.

Several studies have examined dynamic PET parameters

in cancers other than esophageal cancer. Many of these studies

suggest that such parameters are useful in distinguishing between

benign and malignant lesions including in lung cancer, liver

cancer, nasopharyngeal tumors, bone lesions, post-operative

gastroesophageal cancers, and colorectal lesions (13,32–36).

Additionally, dynamic PET has been used to predict hormone receptor

status in breast cancer (37) and

to differentiate subtypes of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

(38).

Differences in metabolic behavior have also been

reported among different cancer types within the same tissue. For

example, Kaneko et al (39)

showed that MRI-FDG imaging could differentiate between

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and

liver metastases. Similarly, Lv et al (40) demonstrated that ΔKi is useful for

distinguishing between primary and synchronous multiple lung

cancers.

Several studies have investigated the relationship

between cancer and treatment response using dynamic PET parameters.

Wang et al (41) reported

that the Palak Ki is associated with the response to immunotherapy

in non-small cell lung cancer. In addition, de Geus-Oei et

al (42) demonstrated that

MRI-FDG correlates with overall survival and progression-free

survival in colorectal cancer, while Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss et

al (43) found that the influx

rate was useful for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

in soft-tissue sarcoma. In concert, Hofheinz et al (44) reported an association between the

Kslope and progression-free survival in non-small cell lung cancer.

Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss et al (45) have also examined prognosis in

non-small cell lung cancer and shown that k3 is related to

progression-free survival in multiple myeloma. To the best of our

knowledge, no studies have reported on these parameters in

esophageal cancer.

Several studies have used CT, MRI, and conventional

FDG-PET images as biomarkers for prognosis prediction and treatment

selection in patients with ESCC (46,47). A

common limitation of these studies was the objectivity of the

region of interests generated when the parameters were obtained

from the images. To ensure objectivity, many studies have taken

measurements at the site of the maximum tumor diameter when

obtaining regions of interest from images, and in some cases,

artificial intelligence has been employed. However, the methods

evaluated only one image slice of the tumor and could not evaluate

the entire tumor. The method employed in this study

semi-automatically set the VOI to surround the entire tumor,

allowing for evaluation of the whole tumor and ensuring

objectivity. We believe that these results are superior to those of

previous studies. Compared to CT and MRI, FDG-PET has drawbacks

such as patient exposure to radiation and examination costs;

however, if the results of these studies can be introduced into

clinical practice, the test will be a useful tool for making

treatment decisions and predicting prognoses.

This study included patients with cT0-1 ESCC. These

patients are generally candidates for surgery or endoscopic

treatment; however, CRT is often performed for elderly patients,

patients with poor activities of daily living, and patients with

circumferential lesions. Therefore, we decided to include such

cases in our analysis.

Our study had several limitations. First, the

biological investigations were not performed to confirm the

parameters obtained from DW-PET/CT. Second, our study was based on

single-center retrospective data and had a relatively small sample

size. Thus, prospective multicenter investigations with larger

populations are required to strengthen the statistical power of our

results. Third, we drew the VOI semi-automatically, which is

therefore objective. Fourth, this study included several types of

treatment, which could be biased. Finally, we did not assess the

histological tumor grade in this study.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that parameters

obtained from DW-PET/CT, such as the PS and PI, can be useful

predictors for treatment response in ESCC patients treated with

CRT.

Acknowledgements

Part of this study was presented at the AACR Annual

Meeting, 23–25 April, 2025 in Chicago, IL, USA. Poster No. 2543,

Section 1, Board 22.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MI, YK, KH, GO, ToT, AH, RM, MU, TaT, YM, AN, TS,

NS, TI and HM contributed to the study conception and design.

Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed

by MI and KH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MI,

and YK, KH, GO, ToT, AH, RM, MU, TaT, YM, AN, TS, NS, TI and HM

commented on previous versions of the manuscript. MI and YK confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the

ethical standards of the responsible committee on human

experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki

Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Written informed consent

was obtained from all participants before examinations and

treatments, including DW-PET/CT. However, with regard to consent

for participation in this study, the opt-out approach was used due

to the retrospective design of the study. The study details were

made publicly available on websites or at locations accessible to

potential participants; all participants were given the freedom to

opt out of the study. This retrospective study was approved by the

Clinical Research Center (Institutional Review Board) of Chiba

University Hospital (IRB reference number: HK202302-10).

Patient consent for publication

Consent for publication of the study was obtained

via the opt-out approach.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

5-FU

|

5-fluorouracil

|

|

AUC

|

area under the receiver operating

characteristic curve

|

|

CF

|

cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil

|

|

CR

|

complete response

|

|

CRT

|

chemoradiotherapy

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

DCF

|

cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil plus

docetaxel

|

|

DW-PET/CT

|

dynamic whole-body positron emission

tomography-computed tomography

|

|

ESCC

|

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

FDG

|

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

|

|

FDG-PET/CT

|

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

|

|

FOLFOX

|

5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and

levofolinate

|

|

LSO

|

lutetium oxyorthosilicate

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

pCR

|

pathological complete response

|

|

PD

|

progressive disease

|

|

PET/CT

|

positron emission tomography-computed

tomography

|

|

PI

|

Patlak intercept

|

|

PR

|

partial response

|

|

PS

|

Patlak slope

|

|

SD

|

stable disease

|

|

SUVmax

|

maximum standardized uptake value

|

|

VOI

|

volume of interest

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kato K, Machida R, Ito Y, Daiko H, Ozawa

S, Ogata T, Hara H, Kojima T, Abe T, Bamba T, et al: Doublet

chemotherapy, triplet chemotherapy, or doublet chemotherapy

combined with radiotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally

advanced oesophageal cancer (JCOG1109 NExT): A randomised,

controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 404:55–66. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Murakami K, Yoshida N, Taniyama Y,

Takahashi K, Toyozumi T, Uno T, Kamei T, Baba H and Matsubara H:

Maximum standardized uptake value change rate before and after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy can predict early recurrence in patients

with locally advanced esophageal cancer: A multi-institutional

cohort study of 220 patients in Japan. Esophagus. 19:205–213. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Swisher SG, Maish M, Erasmus JJ, Correa

AM, Ajani JA, Bresalier R, Komaki R, Macapinlac H, Munden RF,

Putnam JB, et al: Utility of PET, CT, and EUS to identify

pathologic responders in esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg.

78:1152–1160. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bergonie J and Tribondeau L:

Interpretation of some results of radiotherapy and an attempt at

determining a logical technique of treatment. Radiat Res.

11:587–588. 1959. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Warburg O, Wind F and Negelein E: The

metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 8:519–530. 1927.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Vaupel P and Multhoff G: The warburg

effect: Historical dogma versus current rationale. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1269:169–177. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Hohenberger P,

Pan L, Kasper B, Roumia S and Strauss LG: Dynamic PET with FDG in

patients with unresectable aggressive fibromatosis:

Regression-based parametric images and correlation to the FDG

kinetics based on a 2-tissue compartment model. Clin Nucl Med.

37:943–948. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Carmeliet P and Jain RK: Angiogenesis in

cancer and other diseases. Nature. 407:249–257. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gatenby RA and Gillies RJ: Why do cancers

have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 4:891–899. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hu J, Panin V, Smith AM, Spottiswoode B,

Shah V and von Gall CA: Design and implementation of automated

clinical whole body parametric PET with continuous bed motion. IEEE

Trans Radiat Plasma Med Sci. 4:696–707. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Watanabe M, Kato H, Katayama D, Soeda F,

Matsunaga K, Watabe T, Tatsumi M, Shimosegawa E and Tomiyama N:

Semiquantitative analysis using whole-body dynamic F-18

fluoro-2-deoxy-glucose-positron emission tomography to

differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. Ann Nucl Med.

36:951–963. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Patlak CS and Blasberg RG: Graphical

evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time

uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 5:584–590.

1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Osborne DR and Acuff S: Whole-body dynamic

imaging with continuous bed motion PET/CT. Nucl Med Commun.

37:428–431. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Phelps ME, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, Selin C,

Sokoloff L and Kuhl DE: Tomographic measurement of local cerebral

glucose metabolic rate in humans with

(F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: Validation of method. Ann Neurol.

6:371–388. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lemarignier C, Di Fiore F, Marre C, Hapdey

S, Modzelewski R, Gouel P, Michel P, Dubray B and Vera P:

Pretreatment metabolic tumour volume is predictive of disease-free

survival and overall survival in patients with oesophageal squamous

cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 41:2008–2016. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Tanaka K, Shiraishi

O, Motoori M, Peng YF, Yasuda T, Yano M, Shiozaki H, Mori M and

Doki Y: Multicenter phase I/II study of docetaxel, cisplatin and

fluorouracil combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced or

recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Oncology.

80:307–313. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Umeki Y, Matsuoka H, Fujita M, Goto A,

Serizawa A, Nakamura K, Akimoto S, Nakauchi M, Tanaka T, Shibasaki

S, et al: Docetaxel cisplatin 5-FU(DCF) therapy as a preoperative

chemotherapy to advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A

single-center retrospective cohort study. Internal Medicine.

62:319–325. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Katada C, Sugawara M, Hara H, Fujii H,

Nakajima TE, Ando T, Kojima T, Watanabe A, Sakamoto Y, Ishikawa H,

et al: A management of neutropenia using granulocyte colony

stimulating factor support for chemotherapy consisted of docetaxel,

cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in patients with oesophageal squamous

cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 51:199–204. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hayano K, Okazumi S, Shuto K, Matsubara H,

Shimada H, Nabeya Y, Kazama T, Yanagawa N and Ochiai T: Perfusion

CT can predict the response to chemoradiation therapy and survival

in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Initial clinical results.

Oncol Rep. 18:901–908. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Makari Y, Yasuda T, Doki Y, Miyata H,

Fujiwara Y, Takiguchi S, Matsuyama J, Yamasaki M, Hirao T, Koyama

MK, et al: Correlation between tumor blood flow assessed by

perfusion CT and effect of neoadjuvant therapy in advanced

esophageal cancers. J Surg Oncol. 96:220–229. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wongwaiyut K, Ruangsin S, Laohawiriyakamol

S, Leelakiatpaiboon S, Sangthawan D, Sunpaweravong P and

Sunpaweravong S: Pretreatment esophageal wall thickness associated

with response to chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced esophageal

cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 51:947–951. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kasai A, Miyoshi J, Sato Y, Okamoto K,

Miyamoto H, Kawanaka T, Tonoiso C, Harada M, Goto M, Yoshida T, et

al: A novel CT-based radiomics model for predicting response and

prognosis of chemoradiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Sci Rep. 14:20392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Aoyagi T, Shuto K, Okazumi S, Shimada H,

Kazama T and Matsubara H: Apparent diffusion coefficient values

measured by diffusion-weighted imaging predict

chemoradiotherapeutic effect for advanced esophageal cancer. Dig

Surg. 28:252–257. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

De Cobelli F, Giganti F, Orsenigo E,

Cellina M, Esposito A, Agostini G, Albarello L, Mazza E, Ambrosi A,

Socci C, et al: Apparent diffusion coefficient modifications in

assessing gastro-oesophageal cancer response to neoadjuvant

treatment: Comparison with tumour regression grade at histology.

Eur Radiol. 23:2165–2174. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sun NN, Liu C, Ge XL and Wang J: Dynamic

contrast-enhanced MRI for advanced esophageal cancer response

assessment after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Diagn Interv Radiol.

24:195–202. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lei J, Han Q, Zhu S, Shi D, Dou S, Su Z

and Xu X: Assessment of esophageal carcinoma undergoing concurrent

chemoradiotherapy with quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced

magnetic resonance imaging. Oncol Lett. 10:3607–3612. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gu L, Xie X, Guo Z, Shen W, Qian P, Jiang

N and Fan Y: Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging:

A novel approach to assessing treatment in locally advanced

esophageal cancer patients. Niger J Clin Pract. 24:1800–1807. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hirata A, Hayano K, Ohira G, Imanishi S,

Hanaoka T, Murakami K, Aoyagi T, Shuto K and Matsubara H:

Volumetric histogram analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient for

predicting pathological complete response and survival in

esophageal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Am J

Surg. 219:1024–1029. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

van der Aa DC, Gisbertz SS, Anderegg MCJ,

Lagarde SM, Klaassen R, Meijer SL, van Dieren S, Hulshof M, Bergman

J, Bennink RJ, et al: (18)F-FDG-PET/CT to detect pathological

complete response after neoadjuvant treatment in patients with

cancer of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction: Accuracy and

long-term implications. J Gastrointest Cancer. 55:270–280. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Weissinger M, Atmanspacher M, Spengler W,

Seith F, Von Beschwitz S, Dittmann H, Zender L, Smith AM, Casey ME,

Nikolaou K, et al: Diagnostic performance of dynamic whole-body

patlak [(18)F]FDG-PET/CT in patients with indeterminate lung

lesions and lymph nodes. J Clin Med. 12:39422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang Q, Wang RF, Zhang J and Zhou Y:

Differential diagnosis of pulmonary lesions by parametric imaging

in (18)F-FDG PET/CT dynamic multi-bed scanning. J BUON. 18:928–934.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Parodi D, Dighero E, Biddau G, D'Amico F,

Bauckneht M, Marini C, Garbarino S, Campi C, Piana M and Sambuceti

G: Localized FDG loss in lung cancer lesions. EJNMMI Res.

14:1022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Skawran S, Messerli M, Kotasidis F,

Trinckauf J, Weyermann C, Kudura K, Ferraro DA, Pitteloud J, Treyer

V, Maurer A, et al: Can dynamic whole-body FDG PET imaging

differentiate between malignant and inflammatory lesions? Life

(Basel). 12:13502022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang X, Zhuang M, Yang S, Wang Y, Liu Q,

Xu X, Xiao M, Peng Y, Jiang P, Xu W, et al: The valuable role of

dynamic (18)F FDG PET/CT-derived kinetic parameter K(i) in patients

with nasopharyngeal carcinoma prior to radiotherapy: A prospective

study. Radiother Oncol. 179:1094402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sundaraiya S, T R, Nangia S, Sirohi B and

Patil S: Role of dynamic and parametric whole-body FDG PET/CT

imaging in molecular characterization of primary breast cancer: A

single institution experience. Nucl Med Commun. 43:1015–1025. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

van Berkel A, Vriens D, Visser EP, Janssen

MJR, Gotthardt M, Hermus ARMM, Geus-Oei LF and Timmers HJLM:

Metabolic Subtyping of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma by

(18)F-FDG Pharmacokinetics Using Dynamic PET/CT Scanning. J Nucl

Med. 60:745–751. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kaneko K, Nagao M, Yamamoto A, Yano K,

Honda G, Tokushige K and Sakai S: Patlak reconstruction using

dynamic 18 F-FDG PET imaging for evaluation of malignant liver

tumors: A comparison of HCC, ICC, and metastatic liver tumors. Clin

Nucl Med. 49:116–123. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lv W, Yang M, Zhong H, Wang X, Yang S, Bi

L, Xian J, Pei X, He X, Wang Y, et al: Application of dynamic

(18)F-FDG PET/CT for distinguishing intrapulmonary metastases from

synchronous multiple primary lung cancer. Mol Imaging.

2022:80812992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang D, Qiu B, Liu Q, Xia L, Liu S, Zheng

C, Liu H, Mo Y, Zhang X, Hu Y, et al: Patlak-Ki derived from

ultra-high sensitivity dynamic total body [(18)F]FDG PET/CT

correlates with the response to induction immuno-chemotherapy in

locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Nucl

Med Mol Imaging. 50:3400–3413. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

de Geus-Oei LF, van Laarhoven HW, Visser

EP, Hermsen R, van Hoorn BA, Kamm YJ, Krabbe PF, Corstens FH, Punt

CJ and Oyen WJ: Chemotherapy response evaluation with FDG-PET in

patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 19:348–352. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss LG,

Egerer G, Vasamiliette J, Mechtersheimer G, Schmitt T, Lehner B,

Haberkorn U, Stroebel P and Kasper B: Impact of dynamic 18F-FDG PET

on the early prediction of therapy outcome in patients with

high-risk soft-tissue sarcomas after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A

feasibility study. J Nucl Med. 51:551–558. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hofheinz F, Hoff JV, Steffen IG, Lougovski

A, Ego K, Amthauer H and Apostolova I: Comparative evaluation of

SUV, tumor-to-blood standard uptake ratio (SUR), and dual time

point measurements for assessment of the metabolic uptake rate in

FDG PET. EJNMMI Res. 6:532016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Hoffmann M,

Bergner R, Uppenkamp M, Eisenhut M, Pan L, Haberkorn U and Strauss

LG: Prediction of short-term survival in patients with advanced

nonsmall cell lung cancer following chemotherapy based on

2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography: A

feasibility study. Mol Imaging Biol. 9:308–317. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Okazumi S, Ohira G, Hayano K, Aoyagi T,

Imanishi S and Matsubara H: Novel advances in qualitative

diagnostic imaging for decision making in multidisciplinary

treatment for advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Med. 13:6322024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hayano K, Ohira G, Hirata A, Aoyagi T,

Imanishi S, Tochigi T, Hanaoka T, Shuto K and Matsubara H: Imaging

biomarkers for the treatment of esophageal cancer. World J

Gastroenterol. 25:3021–3029. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|