Introduction

Cancer ranks as one of the leading causes of death

worldwide, following cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease

(1). In 2022, there were >20

million novel cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer-associated deaths

were reported worldwide (2),

accounting for nearly 16.8% of all global deaths and 22.8% of

fatalities from non-communicable disease (2), driven by population aging and global

development imbalances. Various factors, including environmental

pollution, viral infection, obesity, genetic variation and

unhealthy lifestyles, are implicated in cancer development

(3–6). However, the specific pathogens and

mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Gene mutation, aberrant expression and epigenetic

modifications can disrupt normal biological functions, which leads

to tumorigenesis. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a type of

non-protein-coding RNA that include >200 nucleotides. lncRNAs

regulate gene expression at transcriptional, epigenetic and

post-transcriptional levels, and are involved in key processes such

as chromosomal silencing, genomic imprinting, transcriptional

interference and intranuclear transport (7). Aberrant lncRNA expression is observed

in various cancer types, such as oral cancer, lung cancer and

gastric cancer, which not only reflect clinical aspects but also

predict prognosis in patients with malignant disease. The

maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3), a 32-kb imprinted gene located

on chromosome 14q32.3, encodes lncRNA MEG3 expression in diverse

tissues, such as cancerous tissues, normal tissues, and blood

(8). It was reported as the

ortholog of gene trap locus 2 in mice by Schuster-Gossler et

al (9) and identified in humans

in 2000 (10). To date, numerous

studies have demonstrated that MEG3 serves as a tumor suppressor

and is involved in cancer-associated processes such as cell

proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, immune response,

metabolism and apoptosis, which serve an important role in tumor

initiation and progression (11–13).

MEG3 is a key component of the p53 and mouse double minute 2 (MDM2)

signaling pathways, where it inhibits carcinogenesis by increasing

p53 expression (14). MEG3

expression is typically reduced or absent in a variety of cancer

types, including acute myeloid leukemia (15), serous ovarian cancer (16) and head and neck cancer (17), which suggests MEG3 may serve as a

tumor suppressor and target for cancer prevention and

treatment.

Genetic alterations, such as single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs), serve a key role in cancer susceptibility. In

lncRNAs, SNPs lead to aberrant transcript splicing and structural

changes, which impairs lncRNA function. Cao et al (18) reported that individuals with the AA

genotype in the MEG3 rs7158663 G>A polymorphism have a markedly

higher risk of colorectal cancer compared with those with the GG

genotype. Since then, several case-control studies have examined

the association between MEG3 polymorphisms and cancer risk,

although the results remain inconclusive (19,20).

Therefore, the present meta-analysis aimed to clarify the potential

associations between MEG3 polymorphisms and cancer risk.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present meta-analysis was conducted in

accordance with the guidelines of PRISMA (21). All data were extracted from

previously published studies and no ethical concerns were

involved.

Literature search strategy

A total of five online databases (PubMed

(pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?Db=pubmed), Excerpta Medica Database

(embase.com/landing?status=grey), Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/), China

National Knowledge Infrastructure (https://www.cnki.net/) and Wanfang (https://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/)) were mined for

studies that examined the association between MEG3 gene

polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility from inception up to

December 2024. Additionally, the references of all included studies

were reviewed to identify additional relevant studies (Table SI).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Observational

studies focusing on MEG3 gene polymorphisms; ii) studies with

sufficient genotype data on allele, homozygous and heterozygote for

each polymorphism locus; iii) studies published in English or

Chinese. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Case reports,

letters and reviews; ii) duplicate reports or those with

overlapping data; iii) studies lacking sufficient data to calculate

odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CI and iv) fundamental studies and others

using animal models or cell lines.

Data extraction

Two authors reviewed all included studies and

extracted the following data: Surname of first author, publication

year, country or region of study, ethnicity differences, control

group origin, sample sizes of patients and controls, frequency of

genotype distribution and genotyping method. Disagreements were

resolved through discussion with a third author.

Quality assessment

A total of two authors evaluated the quality of all

included studies with a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa

Quality Assessment Scale (NOS; Table

SII) (22). The NOS evaluates

six key aspects: Case representativeness, control source,

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) status in controls, genotyping

procedure, sample size and the assessment of the association.

Studies were scored on a scale of 0 to 11, with a score ≥8

indicating high quality.

Statistical analysis

Crude OR and 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate the

statistical strength of the associations between MEG3 polymorphisms

and cancer risk. A total of five genetic models were examined for

the rs7158663 G>A polymorphism: Allele contrast (A vs. G),

codominant models including heterozygote model (GA vs. GG) and

homozygote model (AA vs. GG), dominant model (AG + AA vs. GG) and

recessive model (AA vs. GG + GA). Similar genetic models were

applied to other loci (rs4081134 G>A, rs11160608 A>C,

rs3087918 T>G, rs3783355 G>A, rs2281511 G>A and rs12431658

T>C). Potential heterogeneity between the included studies was

assessed using the Cochran's χ2-based test (23). According to the recommendations of

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, a

random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) was used to

guarantee the statistical power (24,25).

Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, source of controls,

genotyping method and cancer subtypes were conducted when there

were multiple studies on the same theme. Cumulative analyses were

conducted to observe the trends in results when more studies were

added. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness

of the pooled results through gradual exclusion of studies.

Publication bias was evaluated with Egger's bias test and Begg's

funnel plots (26). All statistical

analyses were conducted using STATA (version 14.0; StataCorp LP).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Overall results

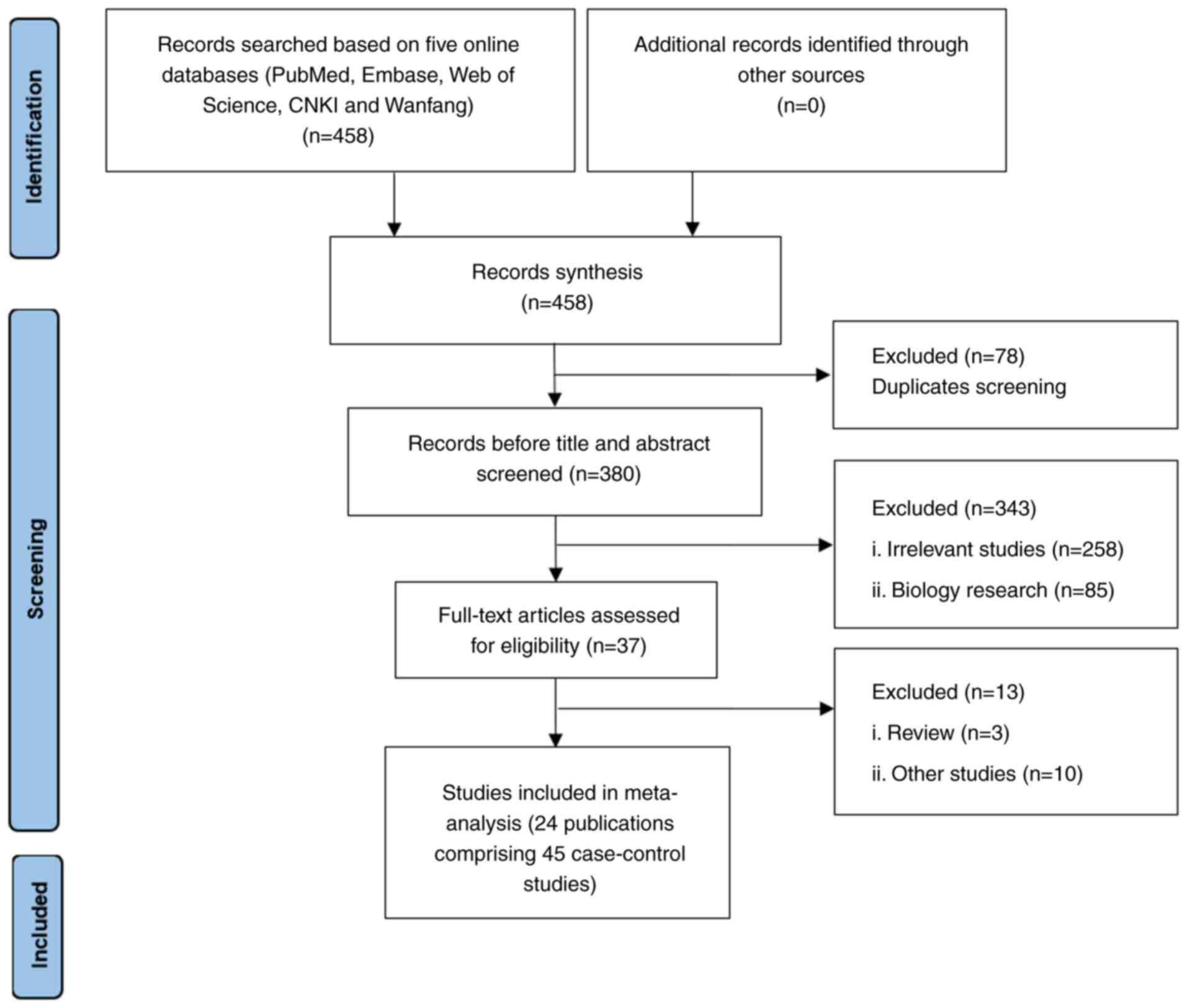

A total of 458 potential publications were

identified through a comprehensive search (Fig. 1). First, 78 duplicate articles were

excluded, 343 irrelevant articles were removed after title and

abstract screening and 13 articles were removed for reasons such as

reviews, fundamental research or lacking sufficient genotype data.

In total, 24 publications comprising 45 independent case-control

studies with 7,423 patients and 9,118 controls were included in

(18–20,27–47).

Of these, 16 studies were conducted in East Asia (based solely on a

Chinese population) and eight were conducted in the Middle East

(Egypt and Iran; Table I). There

were 21 studies that focused on rs7158663 G>A polymorphism

(18–20,27–38,41–46);

seven studies focused on rs4081134 G>A polymorphism (19,20,27,28,38–40),

six focused on s11160608 A>C polymorphism (30,33,38–40,47),

three focused on rs3087918 T>G polymorphism (30,33,38)

and two each focused on rs3783355 G>A (39,40),

rs2281511 G>A (39,40), rs12431658 T>C (39,40)

and rs10132552 T>C (32,42) polymorphisms, respectively. A total

of five case-control studies exhibited deviation from HWE across

multiple loci (Table I).

| Table I.Characteristics of studies on MEG3

polymorphisms and cancer risk. |

Table I.

Characteristics of studies on MEG3

polymorphisms and cancer risk.

| A, rs7158663

G>A |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Genotype

distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Case (%) | Control (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Country | Ethnicity | Source of

controls | Case, n | Control, n | GG | GA | AA | GG | GA | AA | Genotyping

method | Cancer | P-value for

HWE | NOS | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Cao et

al, | China | EA | HB | 516 | 517 | 264 | 200 | 52 | 298 | 188 | 31 |

TaqMan™ | Colorectal | 0.85 | 9 | (18) |

| 2016 |

|

|

|

|

| (51) | (39) | (10) | (58) | (36) | (6) | cancer |

|

|

|

|

| Zhuo et

al, | China | EA | HB | 392 | 783 | 233 | 141 | 18 | 433 | 296 | 54 | TaqMan | Neuro- | 0.72 | 9 | (19) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (59) | (36) | (5) | (55) | (38) | (7) |

| blastoma |

|

|

|

| Yang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 526 | 526 | 268 | 219 | 39 | 289 | 204 | 33 | TaqMan | Lung | 0.71 | 9 | (20) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (51) | (42) | (7) | (55) | (39) | (6) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Zhang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 172 | 224 | 83 | 74 | 15 | 128 | 76 | 10 | TaqMan | Gastric | 0.76 | 7 | (27) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (48) | (43) | (9) | (57) | (34) | (4) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Wei et

al, | China | EA | PB | 1,118 | 1,248 | 717 | 349 | 51 | 795 | 391 | 62 | TaqMan | Liver | 0.13 | 9 | (28) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (64) | (31) | (5) | (64) | (31) | (5) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Ali et

al, | Egypt | ME | HB | 150 | 154 | 57 | 63 | 30 | 84 | 63 | 7 | TaqMan | Breast | 0.26 | 7 | (29) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (38) | (42) | (20) | (55) | (41) | (5) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Zheng et

al, | China | EA | PB | 434 | 700 | 224 | 170 | 33 | 403 | 250 | 47 | Mass- | Breast | 0.33 | 9 | (30) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (52) | (39) | (8) | (58) | (36) | (7) |

ARRAY® | cancer |

|

|

|

| Xu et

al, | China | EA | HB | 165 | 200 | 98 | 54 | 13 | 111 | 78 | 11 | TaqMan | Prostate | 0.57 | 9 | (31) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (59) | (33) | (8) | (56) | (39) | (6) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Kong et

al, | China | EA | HB | 474 | 543 | 215 | 198 | 61 | 290 | 203 | 50 | TaqMan | Gastric | 0.10 | 9 | (32) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (45) | (42) | (13) | (53) | (37%) | ( ) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Mazraeh et

al, | Iran | ME | HB | 100 | 100 | 43 | 36 | 21 | 16 | 48 | 36 | PCR- | Leukemia | 1.00 | 6 | (33) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (43) | (36) | (21) | (16) | (48) | (36) | RFLP |

|

|

|

|

| Wang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 319 | 306 | 163 | 121 | 35 | 178 | 110 | 18 | PCR- | Lymphoma | 0.85 | 8 | (34) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (51) | (38) | (11) | (58) | (36) | (6) | RFLP |

|

|

|

|

| Gao et

al, | China | EA | HB | 430 | 445 | 202 | 185 | 43 | 256 | 159 | 30 | TaqMan | Colorectal | 0.43 | 8 | (35) |

| 2021 |

|

|

|

|

| (47) | (43) | (10) | (58) | (36) | (7) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Shaker et

al, | Egypt | ME | HB | 180 | 150 | 63 | 70 | 47 | 93 | 24 | 33 | TaqMan | Breast | <0.01 | 6 | (36) |

| 2021 |

|

|

|

|

| (35) | (39) | (26) | (62) | (16) | (22) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Moham- | Egypt | ME | HB | 114 | 110 | 33 | 54 | 27 | 60 | 45 | 5 | TaqMan | Hepato | 0.34 | 7 | (37) |

| med et

al, |

|

|

|

|

| (29) | (47) | (24) | (55) | (41) | (5) |

| cellular |

|

|

|

| 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Pei et al,

2022 | China | EA | HB | 266 | 266 | 118 | 119 | 29 | 153 | 96 | 17 | TaqMan | Leukemia | 0.71 | 10 | (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (44) | (45) | (11) | (58) | (36) | (6) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mirzaz- | Iran | ME | HB | 175 | 175 | 46 | 111 | 18 | 69 | 95 | 11 | PCR Tetra- | Lymphoma | 0.04 | 7 | (41) |

| adeh et al,

2022 |

|

|

|

|

| (26) | (63) | (10) | (39) | (54) | (6) | ARMS |

|

|

|

|

| Wang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 118 | 345 | 72 | 39 | 7 | 184 | 135 | 26 | TaqMan | Cervical | 0.86 | 6 | (42) |

| 2022 |

|

|

|

|

| (61) | (33) | (6) | (53) | (39) | (8) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Elhelaly et

al, | Egypt | ME | HB | 160 | 160 | 78 | 50 | 32 | 96 | 56 | 8 | TaqMan | Colorectal | 0.96 | 7 | (43) |

| 2023 |

|

|

|

|

| (49) | (31) | (20) | (60) | (35) | (5) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Asadi et

al, | Iran | ME | HB | 230 | 240 | 75 | 132 | 23 | 104 | 127 | 9 | PCR-Tetra | Breast | <0.01 | 7 | (44) |

| 2024 |

|

|

|

|

| (33) | (57) | (10) | (43) | (53) | (4) | ARMS | cancer |

|

|

|

| Wang et

al, | China | EA | PB | 271 | 267 | 120 | 123 | 28 | 154 | 96 | 17 | PCR- | Hepato- | 0.60 | 8 | (45) |

| 2024 |

|

|

|

|

| (44) | (45) | (10) | (58) | (36) | (6) | sequencer | cellular |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Lao et

al, | China | EA | HB | 200 | 200 | 87 | 76 | 37 | 108 | 71 | 21 | TaqMan | Nasopharyn | 0.08 | 7 | (46) |

| 2024 |

|

|

|

|

| (44) | (38) | (19) | (54) | (36) | (11) |

| geal cancer |

|

|

|

|

| B,

rs4081134G>A |

|

| Zhuo et

al, | China | EA | HB | 392 | 783 | 200 | 165 | 27 | 443 | 294 | 46 | TaqMan | Neuro- | 0.76 | 9 | (19) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (51) | (42) | (7) | (57) | (38) | (6) |

| blastoma |

|

|

|

| Yang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 526 | 526 | 349 | 161 | 16 | 314 | 182 | 30 | TaqMan | Lung | 0.59 | 9 | (20) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (66) | (31) | (3) | (60) | (35) | (6) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Hou et

al, | China | EA | HB | 444 | 984 | 243 | 169 | 16 | 598 | 332 | 54 |

Illumina® | Oral cancer | 0.38 | 7 | (39) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (55) | (38) | (4) | (61) | (34) | (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Zhang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 172 | 224 | 102 | 58 | 12 | 135 | 73 | 16 | TaqMan | Gastric | 0.17 | 7 | (27) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (59) | (34) | (7) | (60) | (33) | (7) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Yunho et

al, | China | EA | HB | 98 | 86 | 47 | 35 | 16 | 39 | 33 | 14 | PCR-RFLP | Oral cancer | 0.13 | 8 | (40) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (48) | (36) | (16) | (45) | (38) | (16) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Wei et

al, | China | EA | HB | 1,118 | 1,248 | 533 | 461 | 120 | 604 | 537 | 103 | TaqMan | Liver | 0.28 | 9 | (28) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (48) | (41) | (11) | (48) | (43) | (8) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Pei et al,

2022 | China | EA | HB | 266 | 266 | 141 | 107 | 18 | 149 | 101 | 16 | TaqMan | Leukemia | 0.84 | 10 | (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (53) | (40) | (7) | (56) | (38) | (6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C. rs11160608

A>C |

|

| Hou et

al, | China | EA | HB | 444 | 984 | 112 | 237 | 93 | 308 | 485 | 191 | Illumina | Oral cancer | 1.00 | 7 | (39) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (25) | (53) | (21) | (31) | (49) | (19) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yunho et

al, | China | EA | HB | 98 | 86 | 55 | 30 | 13 | 44 | 28 | 14 | PCR-RFLP | Oral cancer | 0.02 | 8 | (40) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (56) | (31) | (13) | (51) | (33) | (16) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Zheng et

al, | China | EA | PB | 434 | 700 | 126 | 218 | 80 | 227 | 341 | 132 | Mass- | Breast | 0.84 | 9 | (30) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (29) | (50) | (18) | (32) | (49) | (19) | ARRAY | cancer |

|

|

|

| Mazraeh et

al, | Iran | ME | HeB | 100 | 100 | 28 | 58 | 14 | 39 | 48 | 13 | ARMS- | Leukemia | 0.77 | 6 | (33) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (28) | (58) | (14) | (39) | (48) | (13) | PCR |

|

|

|

|

| Pei et al,

2022 | China | EA | HB | 266 | 266 | 80 | 137 | 49 | 85 | 131 | 50 | TaqMan | Leukemia | 0.97 | 10 | (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (30) | (52) | (18) | (32) | (49) | (19) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Abdi et

al, | Iran | ME | HB | 396 | 399 | 107 | 184 | 104 | 107 | 203 | 89 | Illumina | Gastric | 0.70 | 7 | (47) |

| 2024 |

|

|

|

|

| (27) | (46) | (26) | (27) | (51) | (22) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

|

| D, rs3087918

T>G |

|

| Zheng et

al, | China | EA | PB | 434 | 700 | 171 | 207 | 47 | 259 | 334 | 107 | Mass- | Breast | 0.97 | 9 | (30) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (39) | (48) | (11) | (37) | (48) | (15) | ARRAY | cancer |

|

|

|

| Mazraeh et

al, | Iran | ME | HB | 100 | 100 | 52 | 36 | 12 | 41 | 52 | 7 | PCR-RFLP | Leukemia | 0.08 | 6 | (33) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (52) | (36) | (12) | (41) | (52) | (7) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pei et al,

2022 | China | EA | HB | 266 | 266 | 105 | 129 | 32 | 98 | 128 | 40 | TaqMan | Leukemia | 0.86 | 10 | (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (39) | (48) | (12) | (37) | (48) | (15) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| E, rs3783355

G>A |

|

| Hou et

al, | China | EA | HB | 444 | 984 | 272 | 142 | 24 | 626 | 319 | 39 | Illumina | Oral cancer | 0.84 | 7 | (39) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (61) | (32) | (5) | (64) | (32) | (4) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yunho et

al, | China | EA | HB | 98 | 86 | 51 | 29 | 18 | 47 | 22 | 17 | PCR-RFLP | Oral cancer | <0.01 | 7 | (40) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (52) | (30) | (18) | (55) | (26) | (20) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F, rs2281511

G>A |

|

| Hou et

al, | China | EA | HB | 444 | 984 | 299 | 134 | 11 | 673 | 269 | 42 | Illumina | Oral cancer | 0.03 | 7 | (39) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (67) | (30) | (2) | (68) | (27) | (4) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yunho et

al, | China | EA | HB | 98 | 86 | 63 | 23 | 12 | 58 | 16 | 15 | PCR-RFLP | Oral cancer | <0.01 | 8 | (40) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (64) | (23) | (12) | (67) | (19) | (17) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G, rs12431658

T>C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hou et

al, | China | EA | HB | 444 | 984 | 390 | 50 | 3 | 839 | 139 | 6 | Illumina | Oral cancer | 0.93 | 7 | (39) |

| 2018 |

|

|

|

|

| (88) | (11) | (1) | (85) | (14) | (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yunho et

al, | China | EA | HB | 98 | 86 | 74 | 19 | 5 | 67 | 16 | 3 | PCR-RFLP | Oral cancer | 0.12 | 8 | (40) |

| 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| (76) | (19) | (5) | (78) | (19) | (3%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| H. rs10132552

T>C |

|

| Kong et

al, | China | EA | HB | 474 | 543 | 239 | 207 | 28 | 278 | 219 | 46 | TaqMan | Gastric | 0.76 | 9 | (32) |

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

| (50) | (44) | (6) | (51) | (40) | (8) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

| Wang et

al, | China | EA | HB | 118 | 345 | 82 | 32 | 4 | 187 | 142 | 16 |

TaqMan™ | Cervical | 0.09 | 6 | (42) |

| 2022 |

|

|

|

|

| (69) | (27) | (3) | (54) | (41) | (5) |

| cancer |

|

|

|

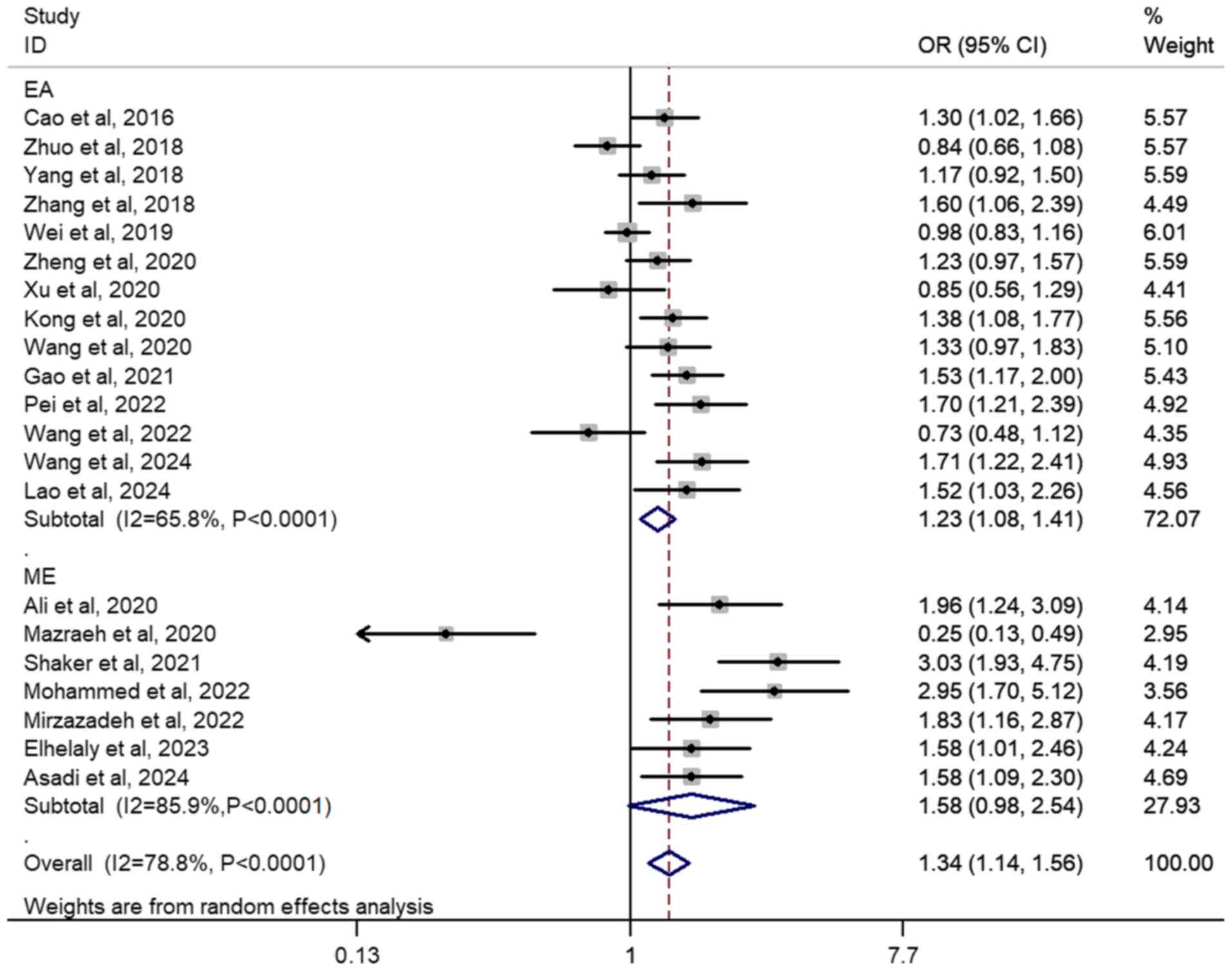

rs7158663 G>A polymorphism and

cancer risk

In total, 21 case-control studies involving 6,502

patients and 7,649 controls were included to investigate the

association between rs7158663 G>A polymorphism and cancer risk.

A significant association was observed in the overall population of

A vs. G (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14–1.48; P<0.01;

I2=82.3%), GA vs. GG (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.09–1.45;

P<0.01; I2=72.0%) AA vs. GG (OR, 1.74; 95%CI,

1.31–2.32; P<0.01; I2=77.3%), GA + AA vs. GG (OR,

1.34; 95% CI, 1.14–1.56; P<0.01; I2=78.8%; Fig. 2) and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 1.55; 95%

CI, 1.23–1.96; P<0.01; I2=67.9%; Table II). Subgroup analyses revealed

significantly elevated cancer risk associated with the rs7158663

G>A polymorphism in both HWE-yes groups [A vs. G (OR, 1.26; 95%

CI, 1.09–1.45; P<0.01; I2=83.3%); GA vs. GG (OR,

1.17; 95% CI, 1.03–1.34; P=0.02; I2=64.2%); AA vs. GG

(OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.20–2.25; P<0.01; I2=79.2%); AG +

AA vs. GG (OR,1.25; 95% CI, 1.07–1.47; P=0.01; I2=77.3%)

and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.18–1.98; P<0.01;

I2=71.1%)] and HWE-no groups [A vs. G (OR, 1.58; 95% CI,

1.31–1.91; P<0.01; I2=14.2%); GA vs. GG (OR, 2.15;

95% CI, 1.17–3.95; P=0.01; I2=80.4%); AA vs. GG (OR,

2.46; 95% CI, 1.65–3.68; P<0.01; I2=0%); AG + AA vs.

GG (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.38–2.99; P<0.01; I2=59.5%)

and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.05–2.72; P=0.03;

I2=32.2%)]. For ethnic diversity, the similar increased

risks were observed across both East Asian and Middle Eastern

individuals (Table II).

Furthermore, similar results were found in the genotyping subgroup

using the TaqMan™ method (Table II). Increased tumorigenic risks

were observed in gastrointestinal tract cancer groups [A vs. G (OR,

1.40; 95% CI, 1.26–1.55; P<0.01; I2=0%); GA vs. GG

(OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.15–1.51; P<0.01; I2=0%); AA vs.

GG (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.51–2.75; P<0.01; I2=29.6%);

GA + AA vs. GG (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.25–1.63; P<0.01;

I2=0%); and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.33–2.56;

P<0.01; I2=43.1%)] and breast cancer groups [A vs. G

(OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.20–2.09; P<0.01; I2=75.3%); GA

vs. GG (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.10–2.78; P=0.02; I2=81.2%);

AA vs. GG (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.34–4.92; P=0.01;

I2=74.8%); GA + AA vs. GG (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 2.22–2.63;

P<0.01; I2=76.9%) and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 1.99; 95%

CI, 1.06–3.74; P=0.03; I2=75.4%; Table II)].

| Table II.ORs and 95% CIs of MEG3 polymorphisms

and cancer risk. |

Table II.

ORs and 95% CIs of MEG3 polymorphisms

and cancer risk.

| A, rs7158663

G>A |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs. GG | AA vs. GG | GA + AA vs. GG | AA vs. GG + GA |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|---|

| Total | 21 | 1.30 | 1.14- | <0.01 | 82.3 | 1.26 | 1.09- | <0.01 | 72.0 | 1.74 | 1.31- | <0.01 | 77.3 | 1.34 | 1.14- | <0.01 | 78.8 | 1.55 | 1.23- | <0.01 | 67.9 |

|

|

|

| 1.48 |

|

|

| 1.45 |

|

|

| 2.32 |

|

|

| 1.56 |

|

|

| 1.96 |

|

|

| HWE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 18 | 1.26 | 1.09- | <0.01 | 83.3 | 1.17 | 1.03- | 0.02 | 64.2 | 1.64 | 1.20- | <0.01 | 79.2 | 1.25 | 1.07- | 0.01 | 77.3 | 1.53 | 1.18- | <0.01 | 71.1 |

|

|

|

| 1.45 |

|

|

| 1.34 |

|

|

| 2.25 |

|

|

| 1.47 |

|

|

| 1.98 |

|

|

| No | 3 | 1.58 | 1.33- | <0.01 | 14.2 | 2.15 | 1.17- | 0.01 | 80.4 | 2.46 | 1.65- | <0.01 | 0 | 2.05 | 1.38- | <0.01 | 59.5 | 1.64 | 1.13- | 0.03 | 32.2 |

|

|

|

| 1.88 |

|

|

| 3.95 |

|

|

| 3.68 |

|

|

| 2.99 |

|

|

| 2.38 |

|

|

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EA | 14 | 1.21 | 1.08 | <0.01 | 70.4 | 1.18 | 1.05- | 0.01 | 51.7 | 1.47 | 1.18- | <0.01 | 53.1 | 1.23 | 1.08- | <0.01 | 65.8 | 1.33 | 1.16–1. | <0.01 | 34.7 |

|

|

|

| 1.35 |

|

|

| 1.33 |

|

|

| 1.83 |

|

|

| 1.41 |

|

|

| 53 |

|

|

| ME | 7 | 1.53 | 1.04- | 0.03 | 88.8 | 1.44 | 0.89- | 0.14 | 84.3 | 2.70 | 1.12- | 0.03 | 88.3 | 1.58 | 0.98- | 0.06 | 85.9 | 2.30 | 1.13- | 0.02 | 84.5 |

|

|

|

| 2.23 |

|

|

| 2.34 |

|

|

| 6.52 |

|

|

| 2.54 |

|

|

| 4.68 |

|

|

| Genotyping

method |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TaqMan | 15 | 1.35 | 1.16- | <0.01 | 82.5 | 1.27 | 1.08- | <0.01 | 71.5 | 1.84 | 1.35- | <0.01 | 75.1 | 1.37 | 1.15- | <0.01 | 78.4 | 1.49 | 1.29- | <0.01 | 69.1 |

|

|

|

| 1.58 |

|

|

| 1.50 |

|

|

| 2.52 |

|

|

| 1.64 |

|

|

| 1.71 |

|

|

| PCR

series | 5 | 1.16 | 0.80- | 0.44 | 87.6 | 1.16 | 0.75- | 0.52 | 81.3 | 1.54 | 0.62- | 0.35 | 87.1 | 1.18 | 0.73- | 0.51 | 86.0 | 1.43 | 1.07- | 0.02 | 75.5 |

|

|

|

| 1.58 |

|

|

| 1.79 |

|

|

| 3.81 |

|

|

| 1.91 |

|

|

| 1.91 |

|

|

| Cancer type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gastroin- | 5 | 1.40 | 1.26- | <0.01 | 0 | 1.32 | 1.15- | <0.01 | 0 | 2.00 | 1.57- | <0.01 | 29.6 | 1.43 | 1.25- | <0.01 | 0 | 1.78 | 1.41- | <0.01 | 43.1 |

|

testinal |

|

| 1.55 |

|

|

| 1.51 |

|

|

| 2.54 |

|

|

| 1.63 |

|

|

| 2.25 |

|

|

|

tract |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liver | 3 | 1.55 | 0.90- | 0.11 | 92.6 | 1.45 | 0.90- | 0.13 | 82.3 | 2.44 | 0.75- | 0.14 | 89.9 | 1.63 | 0.89- | 0.11 | 89.9 | 1.96 | 0.74- | 0.17 | 85.9 |

|

|

|

| 2.6 |

|

|

| 2.33 |

|

|

| 7.93 |

|

|

| 2.97 |

|

|

| 5.17 |

|

|

|

Breast | 4 | 1.59 | 1.20- | <0.01 | 75.3 | 1.75 | 1.10- | 0.02 | 81.2 | 2.56 | 1.34- | 0.01 | 74.8 | 1.79 | 2.22- | <0.01 | 76.9 | 1.99 | 1.06- | 0.03 | 75.4 |

|

|

|

| 2.09 |

|

|

| 2.78 |

|

|

| 4.92 |

|

|

| 2.63 |

|

|

| 3.74 |

|

|

|

Blood | 4 | 1.09 | 0.67- | 0.73 | 90.4 | 1.06 | 0.60- | 0.84 | 85.5 | 1.27 | 0.44- | 0.66 | 88.9 | 1.07 | 0.57- | 0.84 | 89.2 | 1.29 | 0.65- | 0.46 | 77.4 |

|

|

|

| 1.76 |

|

|

| 1.88 |

|

|

| 3.69 |

|

|

| 2.01 |

|

|

| 2.57 |

|

|

|

Other | 5 | 1.02 | 0.82- | 0.85 | 72.0 | 0.97 | 0.80- | 0.78 | 40.4 | 1.11 | 0.69- | 0.66 | 62.5 | 0.99 | 0.78- | 0.96 | 62.1 | 1.12 | 0.74- | 0.59 | 52.7 |

|

|

|

| 1.28 |

|

|

| 1.19 |

|

|

| 1.79 |

|

|

| 1.26 |

|

|

| 1.69 |

|

|

| B, rs4081134

G>A |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 7 | 1.02 | 0.91- | 0.70 | 47.7 | 1.04 | 0.94- | 0.44 | 35.5 | 0.99 | 0.74- | 0.93 | 44.6 | 1.04 | 0.91- | 0.57 | 41.6 | 0.97 | 0.74- | 0.86 | 43.6 |

|

|

|

| 1.15 |

|

|

| 1.15 |

|

|

| 1.32 |

|

|

| 1.19 |

|

|

| 1.29 |

|

|

| Oral cancer | 2 | 1.04 | 0.88- | 0.61 | 0 | 1.20 | 0.98- | 0.11 | 3.3 | 0.79 | 0.49- | 0.33 | 0 | 1.14 | 0.92- | 0.24 | 0 | 0.78 | 0.48- | 0.25 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.24 |

|

|

| 1.50 |

|

|

| 1.27 |

|

|

| 1.42 |

|

|

| 1.20 |

|

|

|

| C, rs11160608

A>C |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 6 | 1.09 | 1.00- | 0.57 | 0 | 1.15 | 1.10- | 0.05 | 0 | 1.17 | 0.94- | 0.10 | 0 | 1.16 | 1.01- | 0.04 | 2.7 | 1.08 | 0.92- | 0.35 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.19 |

|

|

| 1.33 |

|

|

| 1.40 |

|

|

| 1.33 |

|

|

| 1.26 |

|

|

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EA | 4 | 1.08 | 0.98- | 0.13 |

| 1.19 | 1.01- | 0.04 | 0 | 1.15 | 0.93- | 0.20 | 0 | 1.18 | 1.01- | 0.04 | 0 | 1.03 | 0.86- | 0.77 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.20 |

|

|

| 1.41 |

|

|

| 1.42 |

|

|

| 1.37 |

|

|

| 1.23 |

|

|

| ME | 2 | 1.12 | 0.93- | 0.23 |

| 1.17 | 0.64- | 0.61 | 66.5 | 1.22 | 0.85- | 0.28 | 0 | 1.19 | 0.74- | 0.47 | 55.1 | 1.22 | 0.90- | 0.19 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.33 |

|

|

| 2.12 |

|

|

| 1.74 |

|

|

| 1.94 |

|

|

| 1.65 |

|

|

| Cancer type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oral | 2 | 1.05 | 0.77- | 0.76 | 50.0 | 1.26 | 0.99- | 0.07 | 36.5 | 1.24 | 0.91- | 0.17 | 37.4 | 1.13 | 0.71- | 0.61 | 57.1 | 1.07 | 0.82- | 0.68 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.43 |

|

|

| 1.61 |

|

|

| 1.68 |

|

|

| 1.79 |

|

|

| 1.39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| .79 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leukemia | 2 | 1.09 | 0.89- | 0.40 | 0 | 1.25 | 0.90- | 0.18 | 0 | 1.13 | 0.73- | 0.57 | 0 | 1.22 | 0.90- | 0.20 | 24.3 | 1.11 | 0.68- | 1.00 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.35 |

|

|

| 1.74 |

|

|

| 1.75 |

|

|

| 1.67 |

|

|

| 1.47 |

|

|

|

| D, rs3087918

T>G |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 3 | 0.86 | 0.75- | 0.04 | 0 | 0.88 | 0.72- | 0.22 | 30.5 | 0.74 | 0.54- | 0.05 | 0 | 0.85 | 0.70- | 0.09 | 0 | 0.77 | 0.59- | 0.08 | 39.4 |

|

|

|

| 0.99 |

|

|

| 1.08 |

|

|

| 0.99 |

|

|

| 1.03 |

|

|

| 1.03 |

|

|

|

| E, rs3783355

G>A |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 2 | 1.08 | 0.91- | 0.37 | 0 | 1.04 | 0.83- | 0.71 | 0 | 1.25 | 0.81- | 0.31 | 0 | 1.07 | 0.86- | 0.52 | 0 | 1.22 | 0.79- | 0.37 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.30 |

|

|

| 1.31 |

|

|

| 1.94 |

|

|

| 1.33 |

|

|

| 1.86 |

|

|

|

| F, rs2281511

G>A |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 2 | 0.96 | 0.80- | 0.70 | 0 | 1.14 | 0.90- | 0.27 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.38- | 0.10 | 0 | 1.05 | 0.84- | 0.68 | 0 | 0.61 | 0.37- | 0.7 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.16 |

|

|

| 1.44 |

|

|

| 1.08 |

|

|

| 1.31 |

|

|

| 1.03 |

|

|

|

| G, rs12431658

T>C |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 2 | 0.88 | 0.67- | 0.37 | 16.5 | 0.82 | 0.60- | 0.22 | 0 | 1.27 | 0.47- | 0.64 | 0 | 0.84 | 0.63- | 0.30 | 0 | 1.28 | 0.47- | 0.64 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.16 |

|

|

| 1.12 |

|

|

| 3.44 |

|

|

| 1.14 |

|

|

| 3.50 |

|

|

|

| H, rs10132552

T>C |

|

|

|

| A vs. G | GA vs.

GG | AA vs.

GG | GA + AA vs.

GG | AA vs. GG +

GA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a | OR | 95% CI | P-value | I2,

%a |

|

| Total | 2 | 0.79 | 0.50- | 0.29 | 77.4 | 0.77 | 0.37- | 0.49 | 87.4 | 0.68 | 0.43- | 0.10 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.38- | 0.40 | 85.7 | 0.69 | 0.44- | 0.10 | 0 |

|

|

|

| 1.22 |

|

|

| 1.62 |

|

|

| 1.08 |

|

|

| 1.47 |

|

|

| 1.07 |

|

|

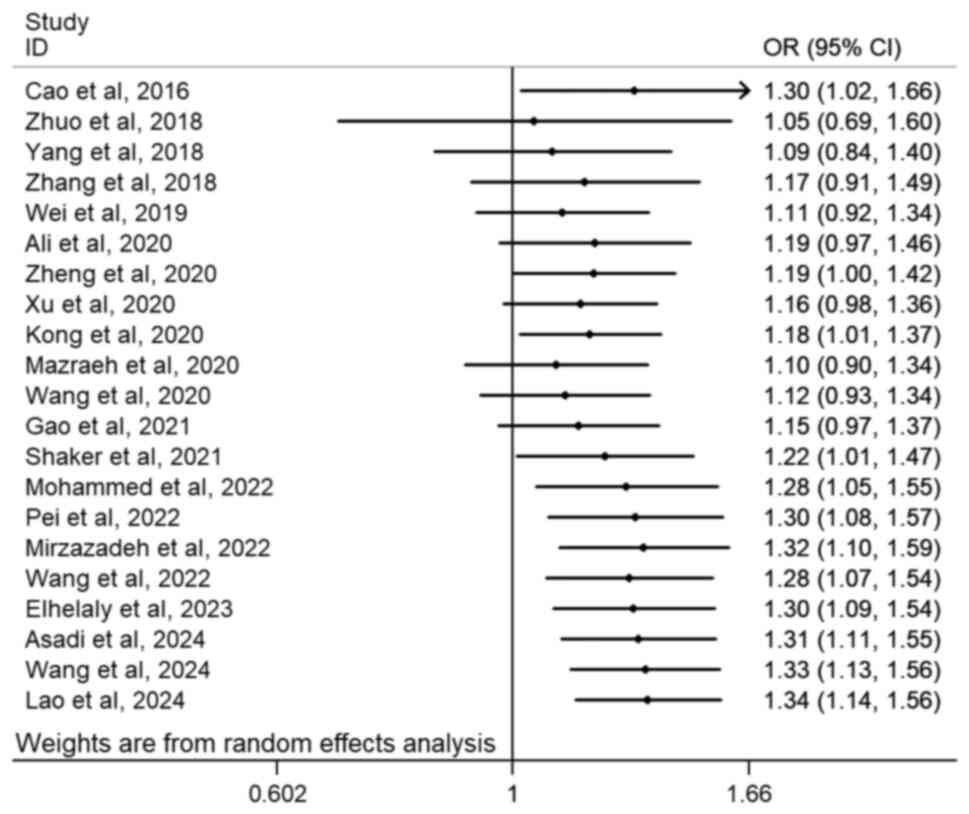

Cumulative analyses in the general population, which

revealed that the first statistically significant association

emerged when the study by Kong et al (2020) (32) was incorporated. This positive

finding specifically demonstrated an association between the

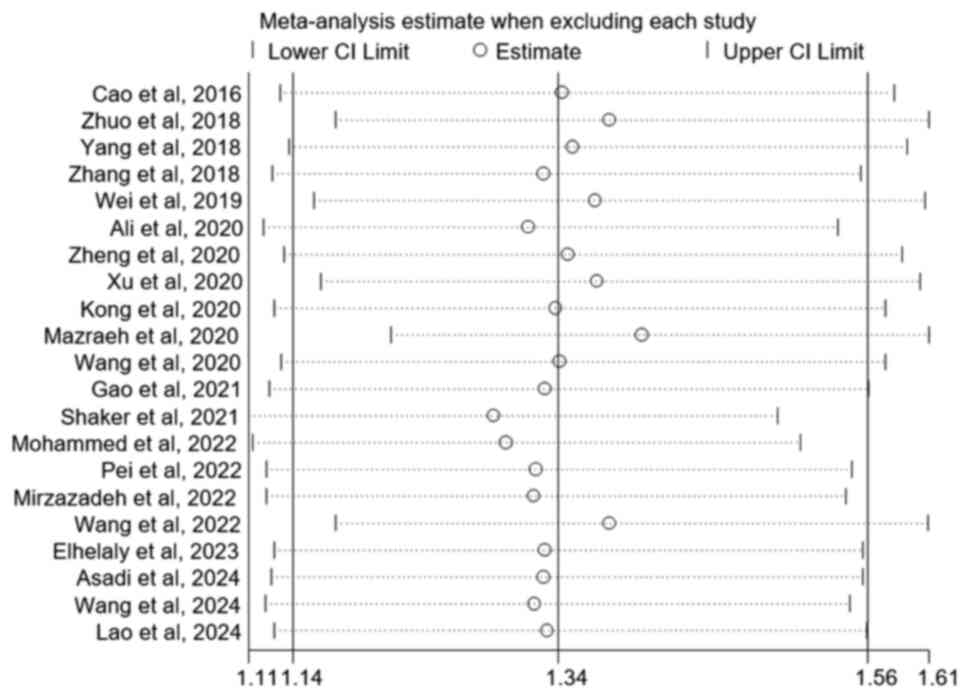

rs7158663 G>A polymorphism and cancer susceptibility (Fig. 3; GA + AA vs. GG). Furthermore,

sensitivity analyses demonstrated a consistent and stable result

when each study was removed step-by-step (Fig. 4; GA + AA vs. GG).

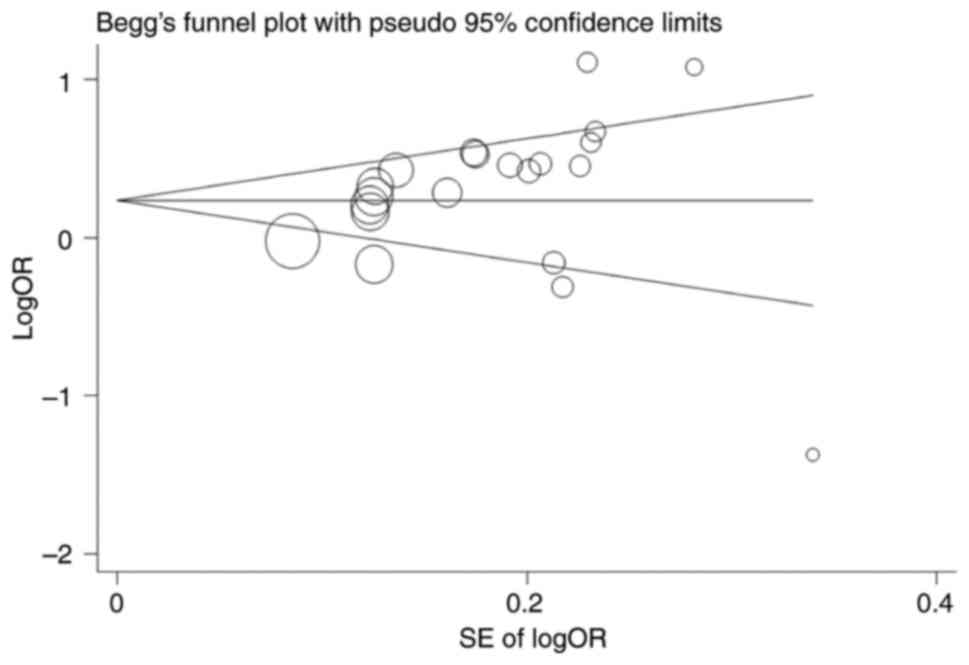

Funnel plot and Egger's test confirmed that there

was no significant publication bias in the general population [A

vs. G (P=0.13); GA vs. GG (P=0.30); AA vs. GG (P=0.10); GA + AA vs.

GG (P=0.18; Fig. 5) and AA vs. GG +

GA (P=0.03)].

rs4081134 G>A polymorphism and

cancer risk

A total of seven case-control studies involving

3,016 patients and 4,117 controls were included to examine the

association between the rs4081134G>A polymorphism and cancer

risk. No significant cancer risk was found overall [A vs. G (OR,

1.02; 95% CI, 0.91–1.15; P=0.70; I2=47.7%); GA vs. GG

(OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.91–1.20; P=0.52; I2=35.5%); AA vs.

GG (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.74–1.32; P=0.93; I2=44.6%); AG +

AA vs. GG (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91–1.19; P=0.57;

I2=41.6%) and AA vs. GG + GA (OR, 0.97; 95% CI,

0.74–1.29; P=0.86; I2=43.6%)] or in the subgroup

analysis for oral cancer (Table

II).

Cumulative and sensitivity analyses demonstrated

fluctuations when studies were added or removed. No publication

bias was observed and the results were further supported by Egger's

test [A vs. G (P=0.61); GA vs. GG (P=0.95); AA vs. GG (P=0.19); AG

+ AA vs. GG (P=0.87) and AA vs. GG + GA (P=0.14); data not

shown].

rs11160608 A>C polymorphism and

cancer risk

A total of six case-control studies involving 1,725

patients and 2,535 controls were included to examine the

association between rs11160608 A>C polymorphism and cancer risk.

Overall, a significantly increased risk of tumorigenesis was

observed [AC + CC vs. AA (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01–1.33; P=0.04;

I2=2.7%); Fig. S1;

Table II].

Cumulative (Fig.

S2; AC + CC vs. AA model) and sensitivity analyses (Fig. S3; AC + CC vs. AA model)

demonstrated no significant differences when each study was added

or removed. Furthermore, no publication bias was observed and the

results were further supported by Egger's test [C vs. A (P=0.51);

AC vs. AA (P=0.84); CC vs. CC (P=0.48); AC + CC vs. AA (P=0.75); CC

vs. AA + AC (P=0.35; Fig.

S4)].

Other polymorphisms and cancer

risk

No significant association was observed between

rs3087918 T>G, rs3783355 G>A, rs2281511 G>A, rs12431658

T>C, rs10132552 T>C polymorphisms and cancer risk (Table II).

Discussion

Cancer is the leading cause of death globally and

imposes notable economic and emotional burdens on both society and

individuals (48). It is predicted

that the global cancer burden will rise to 28.4 million cases by

2040, which marks a 47% increase from 2020 (49). Despite advances in understanding

cancer, its etiology and pathogenesis remain incompletely

understood.

lncRNA is one of the most important ncRNAs, serve

key roles in various biological processes, including the regulation

of histone modification, DNA methylation, transcriptional

regulation and post-transcriptional regulation (50,51).

Increasing evidence highlights that aberrant expression of lncRNAs

is associated with metastasis, recurrence and prognosis across

multiple types of cancer (52,53).

MEG3, located in the imprinting region of the Δ-like

1 homolog-MEG3 locus on chromosome 14q32.3 in humans, has garnered

increasing attention as a tumor suppressor involved in

tumorigenesis (8,21). Dysregulated expression of MEG3

restricts the cancer cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis

while promoting apoptosis (54,55).

Previous studies have suggested that lower MEG3 expression in

patients with cancer is associated with worse pathological grade,

enhanced tumor invasion and worse prognosis (56,57).

Several signaling pathways, including p53, MDM2, VEFG,

Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β, have been implicated in these processes

(14). MEG3 inhibits carcinogenesis

by interacting with microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), such as miR-148a-3p

and miR-155, within both the intracellular and extracellular

microenvironment (3,4), which offers potential strategies for

cancer diagnosis and treatment.

SNPs are the most common forms of genetic mutations

and serve a notable regulatory role in tumorigenesis. SNPs alter

the secondary structure of lncRNAs and affect the binding affinity

between lncRNAs and other molecules. The nucleotide substitution in

the MEG3 rs7158663 G>A polymorphism modifies the folding

structures and minimum free energy (5,58).

Ghaedi et al (59) revealed

that the rs7158663 polymorphism disrupts binding sites for miR-4307

and miR-1265 within MEG3. These alterations impact miRNA-lncRNA

interactions, which modify binding sites for specific miRNAs and

indirectly regulate gene expression.

Cao et al (18) performed a first case-control study

in a Chinese population and reported a markedly increased risk for

colorectal cancer associated with the MEG3 rs7158663 G>A

polymorphism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.08–1.59; P=0.007). Numerous

studies have examined the association between the MEG3 rs7158663

G>A polymorphism and various cancer types (18–20),

however, the results were inconsistent. Ali et al (29) investigated the impact of the

rs7158663 G>A polymorphism on breast cancer and found that

individuals with the AA genotypes exhibited a markedly higher

cancer risk compared with those with the GG genotype (OR, 6.32; 95%

CI, 2.59–15.44; P<0.01). Kong et al (32) identified an increased susceptibility

to gastric cancer in patients carrying the A allele at rs7158663

(OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.14–1.74; P<0.01). Mazraeh et al

(33) reported that both the

mutated homozygous and heterozygous genotypes are more likely to

develop acute myeloid leukemia compared with the GG genotype.

However, other studies, such as those by Zhuo et al

(19), Yang et al (20) and Xu et al (31), found no notable association between

the rs7158663 G>A polymorphism and cancer risk. Similar

inconsistencies were observed for the rs4081134 G>A polymorphism

and other loci (38). These

discrepancies may be attributed to several factors, such as small

sample sizes for each polymorphism locus, ethnic differences

between studies, inconsistent quality of each study and deviation

of HWE in controls in some studies.

To the best of our knowledge, the present systematic

review and meta-analysis encompassed all relevant studies on the

association between multiple lncRNA MEG3 polymorphisms and cancer

susceptibility. The rs7158663 G>A polymorphism markedly

contributed to cancer development in the general population, as

well as in various subgroup analyses. The present findings

suggested that both East Asian and Middle Eastern populations

carrying the A allele are more susceptible to cancer: Ethnic

differences appear to influence cancer susceptibility associated

with these polymorphisms, with individuals from East Asia and the

Middle East exhibiting heightened cancer risk. The majority of

observational studies were conducted in East Asia and the Middle

East (19,20,43).

Furthermore, the present meta-analysis highlighted the potential

role of the rs11160608 A>C polymorphism as a tumorigenic factor;

however, the limited number of original studies warrants caution in

drawing definitive conclusions.

Numerous limitations in the present meta-analysis

should be addressed. First, ethnic bias could not be avoided, since

most studies were conducted in East Asia (based solely on Chinese

populations) and the Middle East. This raises concerns regarding

the generalizability of the present results to other ethnic groups.

Second, several interacting factors, such as viral infection,

environmental pollution, unhealthy lifestyle and dietary habits are

known to influence cancer susceptibility (60,61).

However, a comprehensive assessment of the impact of these factors

was not possible, as data on these variables were not extracted

from all included studies, which may have introduced deviation.

Third, although multiple loci in MEG3 were examined, the

interactive assessment with other genes was not conducted, which

may limit understanding of the tumorigenic mechanisms associated

with these polymorphism loci. Fourth, heterogeneity existed between

genetic models, which was alleviated in the subgroup analysis,

particularly based on ethnicity and cancer subtypes.

Despite these limitations, a comprehensive and

systematic search strategy was employed, yielding a large sample

size. Rigorous statistical methods, including cumulative and

sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment, were used to

evaluate potential bias and subgroup analyses based on HWE status,

ethnicity, genotyping method and tumor subtypes were performed to

explore potential associations.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis indicated

that MEG3 rs7158663 G>A polymorphism may serve a key role in the

development of cancer, particularly in East Asian and Middle

Eastern populations and numerous types of cancer. Furthermore,

future case-control studies with larger sample sizes across diverse

ethnic groups are warranted to confirm these associations in the

future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Research Grant for Health

Science and Technology of Pudong Health Commission (grant no.

PW2022A-63).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YN and YH conceived and designed the study, analyzed

data and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. RC performed the

experiments and wrote the manuscript. XL analyzed data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. YN and YH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Pullella K and Kotsopoulos J: Arsenic

exposure and breast cancer risk: A Re-evaluation of the literature.

Nutrients. 12:33052020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rosenberg AJ, Agrawal N, Pearson A, Gooi

Z, Blair E, Cursio J, Juloori A, Ginat D, Howard A, Chin J, et al:

Risk and response adapted de-intensified treatment for

HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: Optima paradigm expanded

experience. Oral Oncol. 122:1055662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Park S, Ahn S, Kim DG, Kim H, Kang SY and

Kim KM: High frequency of juxtamembrane domain ERBB2 mutation in

gastric cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 19:105–112. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tseng CM, Chen YT, Tao CW, Ou SM, Hsiao

YH, Li SY, Chen TJ, Perng DW and Chou KT: Adult narcoleptic

patients have increased risk of cancer: A nationwide

population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 39:793–797. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hrdlickova B, de Almeida RC, Borek Z and

Withoff S: Genetic variation in the non-coding genome: Involvement

of micro-RNAs and long non-coding RNAs in disease. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1842:1910–1922. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhou Y, Zhang X and Klibanski A: MEG3

noncoding RNA: A tumor suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol. 48:R45–R53.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schuster-Gossler K, Bilinski P, Sado T,

Ferguson-Smith A and Gossler A: The mouse Gtl2 gene is

differentially expressed during embryonic development, encodes

multiple alternatively spliced transcripts, and may act as an RNA.

Dev Dyn. 212:214–228. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Miyoshi N, Wagatsuma H, Wakana S,

Shiroishi T, Nomura M, Aisaka K, Kohda T, Surani MA, Kaneko-Ishino

T and Ishino F: Identification of an imprinted gene, Meg3/Gtl2 and

its human homologue MEG3, first mapped on mouse distal chromosome

12 and human chromosome 14q. Genes Cells. 5:211–220. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ahmadi A, Rezaei A, Khalaj-Kondori M and

Khajehdehi M: A comprehensive bioinformatic analysis identifies a

tumor suppressor landscape of the MEG3 lncRNA in breast cancer.

Indian J Surg Oncol. 15:752–761. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Coan M, Haefliger S, Ounzain S and Johnson

R: Targeting and engineering long non-coding RNAs for cancer

therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 25:578–595. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu SJ, Dang HX, Lim DA, Feng FY and Maher

CA: Long noncoding RNAs in cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer.

21:446–460. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhu J, Liu S, Ye F, Shen Y, Tie Y, Zhu J,

Wei L, Jin Y, Fu H, Wu Y and Zheng X: Long Noncoding RNA MEG3

interacts with p53 protein and regulates partial p53 target genes

in hepatoma cells. PLoS One. 10:e01397902015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

He C, Wang X, Luo J, Ma Y and Yang Z: Long

noncoding RNA maternally expressed gene 3 is downregulated, and its

insufficiency correlates with Poor-risk stratification, worse

treatment response, as well as unfavorable survival data in

patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

19:15330338209458152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Buttarelli M, De Donato M, Raspaglio G,

Babini G, Ciucci A, Martinelli E, Baccaro P, Pasciuto T, Fagotti A,

Scambia G and Gallo D: Clinical value of lncRNA MEG3 in High-grade

serous ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12:9662020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ji Y, Feng G, Hou Y, Yu Y, Wang R and Yuan

H: Long noncoding RNA MEG3 decreases the growth of head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma by regulating the expression of miR-421 and

E-cadherin. Cancer Med. 9:3954–3963. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cao X, Zhuang S, Hu Y, Xi L, Deng L, Sheng

H and Shen W: Associations between polymorphisms of long non-coding

RNA MEG3 and risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese. Oncotarget.

7:19054–19059. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhuo ZJ, Zhang R, Zhang J, Zhu J, Yang T,

Zou Y, He J and Xia H: Associations between lncRNA MEG3

polymorphisms and neuroblastoma risk in Chinese children. Aging

(Albany NY). 10:481–491. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang Z, Li H, Li J, Lv X, Gao M, Bi Y,

Zhang Z, Wang S, Li S, Li N, et al: Association between long

noncoding RNA MEG3 polymorphisms and lung cancer susceptibility in

Chinese northeast population. DNA Cell Biol. 37:812–820. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J and Altman

DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and

meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol.

62:1006–1012. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stang A: Critical evaluation of the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of

nonrandomized studies in Meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol.

25:603–605. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J,

Marín-Martínez F and Botella J: Assessing heterogeneity in

meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods.

11:193–206. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

DerSimonian R: Meta-analysis in the design

and monitoring of clinical trials. Stat Med. 15:1237–1252. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mantel N and Haenszel W: Statistical

aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of

disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 22:719–748. 1959.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M and

Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical

test. BMJ. 315:629–634. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang Q, Ai L and Dai Y: Association

between polymorphism of long non-coding RNA maternally expressed

gene 3 and risk of gastric cancer. Chin J Bases Clin Gen Surg.

25:1323–1326. 2018.

|

|

28

|

Wei Z: Analysis of the Effect of Genetic

Variants of MEG3-P53-MDM2-PTEN Molecular Pathway on

Hepatocarcinogenesis. Master's degree dissertation. 2019.

|

|

29

|

Ali MA, Shaker OG, Alazrak M, AbdelHafez

MN, Khalefa AA, Hemeda NF, Abdelmoktader A and Ahmed FA:

Association analyses of a genetic variant in long non-coding RNA

MEG3 with breast cancer susceptibility and serum MEG3 expression

level in the Egyptian population. Cancer Biomark. 28:49–63. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zheng Y, Wang M, Wang S, Xu P, Deng Y, Lin

S, Li N, Liu K, Zhu Y, Zhai Z, et al: LncRNA MEG3 rs3087918 was

associated with a decreased breast cancer risk in a Chinese

population: A case-control study. BMC Cancer. 20:6592020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu B, Zhang M, Liu C, Wang C, You Z, Wang

Y and Chen M: Association of Long Non-coding RNA MEG3 polymorphisms

and risk of prostate cancer in chinese han population. Urol J.

18:176–180. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kong X, Yang S, Liu C, Tang H, Chen Y,

Zhang X, Zhou Y and Liang G: Relationship between MEG3 gene

polymorphism and risk of gastric cancer in Chinese population with

high incidence of gastric cancer. Biosci Rep. 40:BSR202003052020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mazraeh SA, Gharesouran J, Ghafouri-Fard

S, Ganjineh Ketab FN, Hosseinzadeh H, Moradi M, Javadlar M,

Hiradfar A, Rezamand A, Taheri M and Rezazadeh M: Association

between WT1 and MEG3 polymorphisms and risk of acute myeloid

leukemia. Meta Gene. 23:1006362020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wang XR: Association analyses of genetic

variants in long non-coding RNA MEG3 with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma susceptibility in Chinese Han population. Master's degree

dissertation. 2020.

|

|

35

|

Gao X, Li X, Zhang S and Wang X: The

association of MEG3 gene rs7158663 polymorphism with cancer

susceptibility. Front Oncol. 11:7967742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shaker O, Ayeldeen G and Abdelhamid A: The

impact of single nucleotide polymorphism in the Long Non-coding

MEG3 gene on MicroRNA-182 and MicroRNA-29 expression levels in the

development of breast cancer in egyptian women. Front Genet.

12:6838092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mohammed SR, Shaker OG, Mohamed MM,

Abdelhafez Mostafa MN, Gaber SN, Ali DY, Hussein HA, Elebiary AM,

Abonar AA, Eid HM and El Sayed Ali HS: The emerging role of lncRNA

MEG3 and MEG3 rs7158663 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 26:11–21. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pei JS, Chang WS, Chen CC, Mong MC, Hsu

SW, Hsu PC, Hsu YN, Wang YC, Tsai CW and Bau DT: Novel Contribution

of Long Non-coding RNA MEG3 genotype to prediction of childhood

leukemia risk. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 19:27–34. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hou Y, Zhang B, Miao L, Ji Y, Yu Y, Zhu L,

Ma H and Yuan H: Association of long non-coding RNA MEG3

polymorphisms with oral squamous cell carcinoma risk. Oral Dis.

25:1318–1324. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jeong YH and Zhao ZH: Correlation between

long noncoding RNA Meg3 polymorphism and risk of oral squamous cell

carcinoma. J Modern Stomatol. 33:328–332. 2019.(In Chinese).

|

|

41

|

Mirzazadeh S, Sarani H, Nakhaee A, Hashemi

SM, Taheri M, Hashemi M and Bahari G: Association between PAX8AS1

(rs4848320 C > T, rs1110839 G > T, and rs6726151 T > G)

and MEG3 (rs7158663) gene polymorphisms and non-Hodgkin lymphoma

risk. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 41:1174–1186. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang CT, Wu HY, Xia W, Cheng YP, Yang S,

Feng YL, Lu XY, Liang GY and Xu M: The association between

polymorphisms in long non-coding RNA MEG3 and the different

cervical lesions. Modern Oncol. 30:2804–2810. 2022.(In

Chinese).

|

|

43

|

Elhelaly Elsherbeny M, Ramadan Elsergany A

and Gamil Shaker O: Association of lncRNA MEG3 Rs7158663

polymorphism and serum expression with colorectal cancer in

egyptian patients. Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 12:102–111.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Asadi A, Barati F, Nakhaee A, Jahantigh D,

Hashemi SM, Taheri M and Bahari G: Association between PRNCR1,

PAX8AS1, MEG3, and PTENP1 gene polymorphisms and breast cancer

risk. Per Med. 21:373–383. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang Y, Gao F and Lu J: MEG3 rs7158663

genetic polymorphism is associated with the risk of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 44:531–541. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lao X, Wang Y, Huang R, He Y, Lu H and

Liang D: Genetic variants of LncRNAs HOTTIP and MEG3 influence

nasopharyngeal carcinoma susceptibility and clinicopathologic

characteristics in the Southern Chinese population. Infect Agent

Cancer. 19:322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Abdi E, Latifi-Navid S, Kholghi-Oskooei V,

Mostafaiy B, Pourfarzi F and Yazdanbod A: Roles of the lncRNAs

MEG3, PVT1 and H19 tagSNPs in gastric cancer susceptibility. BMC

Cancer. 24:14402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N and Chen WQ:

Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A

secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J

(Engl). 134:783–791. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer Statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P,

Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen LL, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME,

Fitzgerald KA, et al: Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions,

challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:430–447.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bridges MC, Daulagala AC and Kourtidis A:

LNCcation: LncRNA localization and function. J Cell Biol.

220:e2020090452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Nandwani A, Rathore S and Datta M: LncRNAs

in cancer: Regulatory and therapeutic implications. Cancer Lett.

501:162–171. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ma L, Bajic VB and Zhang Z: On the

classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 10:925–933. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ahmad M, Weiswald LB, Poulain L, Denoyelle

C and Meryet-Figuiere M: Involvement of lncRNAs in cancer cells

migration, invasion and metastasis: Cytoskeleton and ECM crosstalk.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ahadi A: Functional roles of lncRNAs in

the pathogenesis and progression of cancer. Genes Dis. 8:424–437.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

He Y, Luo Y, Liang B, Ye L, Lu G and He W:

Potential applications of MEG3 in cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

Oncotarget. 8:73282–73295. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang J, Lin Z, Gao Y and Yao T:

Downregulation of long noncoding RNA MEG3 is associated with poor

prognosis and promoter hypermethylation in cervical cancer. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 36:52017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL and Huarte M:

Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological

functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:96–118. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ghaedi H, Zare A, Omrani MD, Doustimotlagh

AH, Meshkani R, Alipoor S and Alipoor B: Genetic variants in long

noncoding RNA H19 and MEG3 confer risk of type 2 diabetes in an

Iranian population. Gene. 675:265–271. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Virolainen SJ, VonHandorf A, Viel K,

Weirauch MT and Kottyan LC: Gene-environment interactions and their

impact on human health. Genes Immun. 24:1–11. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Su H and Xie H: Associations between

lifestyle habits, environmental factors and respiratory diseases: A

cross-sectional study from southwest China. Front Public Health.

13:15139262025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|