Introduction

The global burden of colorectal cancer (CRC) is

substantial, with incidence rates rising, particularly in

developing countries, where healthcare systems often struggle to

provide adequate cancer care (1).

CRC is the third most common malignant tumor worldwide and the

second leading cause of cancer-related death following lung cancer

(2). The International Agency for

Research on Cancer estimates that the number of worldwide novel CRC

cases and associated deaths will be ~3.2 and 1.6 million,

respectively, in 2040 (3). The

disease presents substantial challenges to public health, not only

due to the physical and psychological burdens experienced by

patients, but also due to the notable healthcare costs involved in

its management (4).

Current CRC treatments, including surgery,

chemotherapy and radiation therapy, are often constrained by

serious side effects, such as adverse effects and high recurrence

rates, and inconsistent efficacy across patients. These limitations

underscore the urgent need for innovative adjunctive therapeutic

strategies that can improve treatment outcomes while minimizing

adverse effects (5,6). Postoperative infection, a common

complication following surgery, profoundly impacts both surgical

outcomes and patient prognosis; therefore, it remains a key focus

for prevention and control during the perioperative period

(7).

Recently, the use of probiotics as a supportive CRC

treatment has gained attention due to their ability to modulate the

gut microbiota and enhance immune responses (8). Probiotics are live microorganisms that

provide health benefits to the host, particularly through their

regulatory effects on the gut microbiome and immune system

(9). Certain probiotic strains,

such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Bifidobacterium longum

and Lactobacillus casei, may help prevent CRC by inhibiting

tumor growth and metastasis, reducing inflammation and improving

the overall gut environment (10).

Furthermore, probiotics have been found to support gut health and

alleviate the adverse effects commonly associated with conventional

cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal

toxicity (11). The beneficial

effects of probiotics may be mediated through mechanisms such as

modulation of the intestinal microbiota, strengthening of the

epithelial barrier function and regulation of systemic inflammatory

responses (12). These attributes

suggest that probiotics may not only improve the quality of life of

patients with CRC but also contribute to enhanced treatment

outcomes.

Despite a promising theoretical foundation, the

clinical application of probiotics in CRC management remains

inconsistent. A systematic review of the existing literature

revealed mixed findings A systematic review of the existing

literature revealed mixed findings regarding the effects of

probiotics on patients with CRC (13). Some studies reported beneficial

effects, suggesting that probiotics may modify the gut microbiota,

reduce inflammatory cytokines and secrete anticancer metabolites

(14). Probiotics have also been

revealed to modulate T-lymphocyte and dendritic cell activities

(15). Furthermore, specific lactic

acid-producing bacteria, valued for their immunomodulatory

properties, have demonstrated efficacy for instance, combinations

such as Lactobacillus salivarius and Lactobacillus

fermentum with Lactobacillus acidophilus have been

associated with reduced CRC cell proliferation (16). Other studies demonstrated no notable

impact on disease progression or survival outcomes (17,18).

This variability may stem from differences in study design,

probiotic strain dosage regimens and patient populations,

contributing to the heterogeneity of the results. Moreover, the

absence of robust, high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the

efficacy and safety of probiotics in this context (19). To address these gaps, the present

meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis (TSA) were employed to

systematically assess the available evidence on the use of

probiotics as an adjunct to standard CRC therapies. Meta-analysis

enables the synthesis of data across multiple studies, which

provides a more comprehensive evaluation of treatment effects. In

parallel, TSA can be used to estimate the required sample size to

confirm the reliability of the findings, which reduces the risk of

type I errors (20). The primary

aim of the present study was to clarify the role of probiotics in

enhancing the efficacy and safety of CRC treatment. By offering a

thorough, evidence-based assessment, the present study aims to

inform clinical practice and support the potential integration of

probiotics into CRC management. Future research should focus on

identifying the most effective probiotic strains and elucidating

the underlying mechanisms through which these microorganisms

influence tumor biology and patient outcomes (4).

Materials and methods

Study registration

The present study adhered to the Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and was

registered with the International Prospective Register of

Systematic Reviews under the identifier CRD42024510734 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024510734).

Literature search strategy

A systematic review was conducted by searching

multiple databases, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Embase (https://www.embase.com), Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central), Allied and

Complementary Medicine Database (https://www.proquest.com/amed), the American

Association for Cancer Research abstract database (https://www.aacr.org/) and China Biology Medicine disc

(http://www.sinomed.ac.cn). The search

covered all relevant articles published from the inception of each

database until December 26, 2023, without language restrictions.

The search strategy employed a combination of Medical Subject

Headings terms (https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov) and free-text keywords,

including disease-related search terms such as ‘CRC’, ‘colorectal

tumor’ and ‘colorectal neoplasm’. Intervention terms were comprised

of ‘probiotics’, ‘Lactobacilli’, ‘Bifidobacteria’,

‘Lactococci’, ‘yeast’, ‘Enterococci’,

‘Bifidobacterium’, ‘Lactobacillus’ and

‘Saccharomyces’. To identify relevant study designs, filters

such as ‘RCT’, and ‘placebo-controlled’ were applied. Boolean

operators (AND/OR) and proximity operators (NEAR/3) were used to

enhance search sensitivity. The full search strategy, adapted to

the syntax requirements of each database, is provided in Data S1.

Manual searches were additionally conducted to

ensure literature saturation. These included screening the

reference lists of the included studies and relevant review

articles, as well as reviewing journals subscribed to by the

People's Hospital of Putuo District library. Printed copies of

conference proceedings from the National Conference on Clinical

Nutrition (2021–2023), obtained during conference attendance were

also reviewed.

Where applicable, the corresponding authors of

potentially eligible studies were contacted via email to request

the missing data. Any unresolved missing data were addressed using

sensitivity analyses following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic

Reviews of Interventions (version 6.3; section 16.1.2; http://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6.3/chapter-16).

Study inclusion and exclusion

criteria

Publicly accessible RCTs that investigated the

efficacy of probiotic-assisted treatment in patients with CRC who

underwent open, laparoscopic or robotic CRC surgery were included

in this study. Sex and ethnicity were not restricted in the present

study. In the RCTs, the treatment group was treated with any dose

and type of probiotic preparation including Lactobacillus,

Bifidobacterium, Saccharomyces, and multi-strain combinations,

and the control group was treated with a placebo. The efficacy and

safety of the primary outcome measures, including the incidence of

postoperative infections and mean number of hospitalization days,

were explored. Studies in which the patients had advanced CRC who

could not undergo surgery, received other organ resections or had a

combination of other malignant tumors or gastrointestinal diseases

were excluded. Studies that could not extract the primary outcome

data and used probiotics combined with other adjunctive therapies,

in addition to studies on the pharmacokinetics of probiotics

without long-term follow-up outcome data were also excluded.

Literature screening and data

extraction

Two researchers conducted a thorough review of the

literature, extracted the data and cross-checked their findings. In

the event of discrepancies, they engaged in discussions to resolve

them or sought assistance from a third party for adjudication. Data

extraction was performed using a customized form, which encompassed

essential information, such as the authors of the included studies,

publication dates, characteristics of the study subjects, details

of interventions, elements of bias assessment and outcome measures

of interest. During data extraction, the probiotic genus (or

species/strain) used in each intervention arm was recorded for

every included study. The subgroup analyses (Lactobacillus,

Bifidobacterium, Saccharomyces and multi-strain combinations)

were then defined based on the predominant probiotic genus or

formulation type that consistently emerged from this extracted data

across the included studies.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the studies included in the

analysis was independently assessed by two investigators and

subsequently verified. The assessment of bias in the included

studies was conducted using the RCT risk of bias assessment tool

recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (21). This evaluation considered multiple

factors, such as the randomization method, allocation concealment,

blinding procedures for patients and investigators, blinding of

outcome assessors, completeness of outcome data, selective

reporting of study results and identification of other potential

sources of bias such as industry sponsorship bias and

geographic/ethnic heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing RevMan

software (version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration), with the mean

difference (MD) employed as the effect size for continuous

variables and the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous variables, each

presented with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity among the study outcomes was

assessed using the χ2 test (α=0.1) in conjunction with

the I2 statistic to measure the extent of

heterogeneity.

Meta-analysis was performed with a random-effects

model. In instances of significant statistical heterogeneity within

the findings of the incorporated studies, the origin of

heterogeneity was explored through subgroup analysis.

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots.

Additionally, TSA was performed using TSA software (version 0.9;

Copenhagen Clinical Trials Centre in Denmark) (22). TSA, a form of cumulative

meta-analysis, addresses the issue of random errors (both

false-negative and false-positive outcomes) that can occur in

conventional meta-analysis during repeated updates. Furthermore,

TSA helps determine the sample size required to achieve a reliable

conclusion. TSA analysis excluded zero-event studies (studies with

no infection events in both groups). The cumulative Z-curve

constituted the core graphical output of TSA. This curve plotted

the cumulative Z-scores (standard normal deviates) derived from

sequentially incorporating trial data as they accumulate over time,

thereby tracking the evolving strength of evidence for or against

the intervention effect. TSA employed this curve in conjunction

with pre-specified monitoring boundaries to assess potential early

stopping points. Benefit (efficacy) boundaries are defined such

that if the cumulative Z-curve crosses above this boundary, it

provides statistically significant evidence favoring the

intervention effect, allowing for an early conclusion of benefit.

Conversely, crossing a predefined futility boundary suggests a lack

of clinically meaningful effect. The region between these

boundaries represents a zone of insufficient evidence, indicating

that more data are required. A crucial parameter is the Required

Information Size (RIS), which estimates the total number of

participants needed to detect (or reject) a predefined target

intervention effect (such as, a 15% relative risk reduction) with a

prespecified power (typically 80–90%) while controlling the Type I

error rate (typically 5%). The RIS determines the maximum extent of

the X-axis (representing cumulative information size) on the TSA

graph. Decision rules based on the cumulative Z-curve position

relative to the boundaries are: i) If Z > Upper boundary, firm

evidence of benefit is concluded; ii) if Z < Lower boundary,

firm evidence of futility (or harm) is concluded; iii) if Z remains

between the boundaries, evidence is deemed inconclusive,

necessitating further trials.

Results

Literature search results

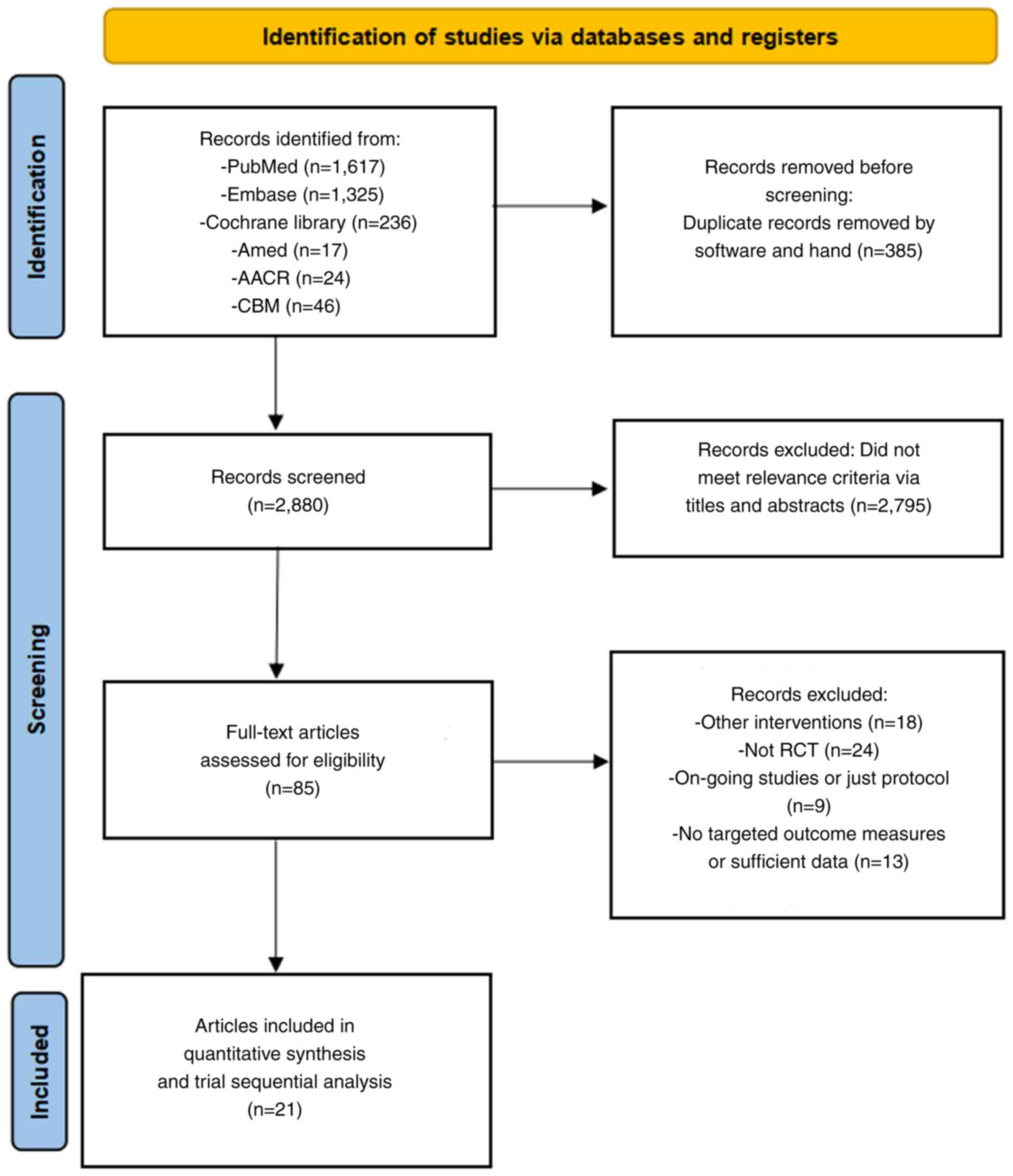

The search strategy initially retrieved 3,265

documents. After removing duplicates and conducting a preliminary

assessment of titles and abstracts, 2,880 documents remained.

Scrutiny of the full texts further narrowed down the total to 64

documents for rescreening, which ultimately identified 21 studies

suitable for quantitative meta-analysis and TSA (23–43).

These studies included 1,602 patients with CRC who had undergone

surgery or were scheduled to undergo surgery. The literature

screening process and outcomes are displayed in Fig. 1.

Basic characteristics of included

studies

Table I presents the

fundamental characteristics of the included studies. The detailed

information includes the country of origin, age range of the

participants, sample size, specific intervention measures and

duration of administration.

| Table I.Basic characteristics of included

studies. |

Table I.

Basic characteristics of included

studies.

|

|

| Sample size, n |

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| Age (range),

years |

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Country | T | C | Interventions | Duration of

administration | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Xia et al,

2010 | China | 30 | 30 | 67.3 (37–82) | Lactobacillus

casei, | >5 days

preoperatively | (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

acidophilus |

|

|

| Zhang et al,

2010 | China | 30 | 30 | T, 66.7 (41–83); |

Bifidobacterium | For 5 days

preoperatively | (42) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 63.0 (39–81) |

|

|

|

| Liu et al,

2011 | China | 50 | 50 | T, 65.3±11.0; | Lactobacillus

plantarum, | For 6 days

preoperatively | (28) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 65.7±9.9 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus | and 10 days

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and

Bifidobacterium longum |

|

|

| Zhang et al,

2012 | China | 30 | 30 | T, 67.5 (45–87); | Bifidobacterium

longum, | For 3–5 days

preoperatively | (43) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 61.5 (46–82) | Lactobacillus

acidophilus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and Enterococcus

faecalis |

|

|

| Liu et al,

2013 | China | 75 | 75 | T,

62.28±12.41; | Lactobacillus

plantarum, | For 6 days

preoperatively | (29) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 66.06±11.02 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus | and 10 days

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and

Bifidobacterium longum |

|

|

| Pellino et

al, 2013 | Italy | 10 | 8 | T, 71.5±2.1; | Streptococcus

thermophilus, | For 1 day to 4

weeks after | (34) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 72.9±1.6 | Bifidobacterium

longum, | discontinuing

antibiotics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

breve, |

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

infantis, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

acidophilus, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

plantarum, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

paracasei, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

delbrueckii |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| subsp.

bulgaricus |

|

|

| Mangell et

al, | Sweden | 32 | 32 | T, 74 (70–80); | Lactobacillus

plantarum | For 8 days

preoperatively | (31) |

| 2012 |

|

|

| C, 70 (64–79) |

| and 5 days

postoperatively |

|

| Chen et al,

2014 | China | 35 | 35 | T, 60.3±17.2; | Clostridium

typhimurium | For 5 days | (24) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 59.8±18.7 | and

Bifidobacterium infantis | preoperatively and

7 days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

postoperatively |

|

| Sadahiro et

al, | Japan | 100 | 95 | T, 67±9; |

Bifidobacteria | For 7 days

preoperatively | (36) |

| 2014 |

|

|

| C, 66±12 |

| and 5–10 days

postoperatively |

|

| Consoli et

al, | Brazil | 15 | 18 | T, 51 (28–76); | Saccharomyces

boulardii | For at least 7

days | (25) |

| 2016 |

|

|

| C, 59 (17–83) |

| preoperatively |

|

| Liu et al,

2015 | China | 66 | 68 | T,

65.62±18.18; | Lactobacillus

plantarum, | For 6 days

preoperatively | (30) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 60.16±16.20 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus | and 10 days

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and

Bifidobacterium longum |

|

|

| Mizuta et

al, 2016 | Japan | 31 | 29 | T, 68.9±10.4; | Bifidobacterium

longum | For 7–14 days

preoperatively | (32) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 71.2±9.5 |

| and 14 days

postoperatively |

|

| Yang et al,

2016 | China | 30 | 30 | T, 63.90±

2.25; | Bifidobacterium

longum, | For 5 days

preoperatively | (40) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 62.17±11.06 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus | to 7 days

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and Enterococcus

faecalis |

|

|

| Kotzampassi et

al, | Greece | 84 | 80 | T, 65.9±11.5; | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | From the day of

surgery to | (27) |

| 2015 |

|

|

| C, 66.4±11.9 | Lactobacillus

plantarum, | 14 days

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

lactis and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Saccharomyces

boulardii |

|

|

| Tan et al,

2016 | Malaysia | 20 | 20 | T, 64.3±14.5; | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | For 8 days

preoperatively | (37) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 68±11.9 | Lactobacillus

casei, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

lactis, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

bifidum, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

longum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and

Bifidobacterium infantis |

|

|

| Bajramagic et

al, | Bosnia and | 39 | 39 | NA | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | For 3 days | (23) |

| 2019 | Herzegovina |

|

|

| Lactobacillus

casei, | preoperatively

to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

plantarum, | 30 days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

rhamnosus, |

postoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

lactis, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

bifidum, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

breve, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Streptococcus

thermophiles |

|

|

| Xu et al,

2019 | China | 30 | 30 | T,

61.03±15.28; | Bifidobacterium

longum, | For 7

consecutive | (39) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 62.35±13.71 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus | days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and Enterococcus

faecalis | preoperatively |

|

| Zaharuddin et

al, | Malaysia | 27 | 25 | T, 67.33±9.44; | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | For 4 weeks | (41) |

| 2019 |

|

|

| C, 66.5±8.57 | Lactobacillus

lactis, | postoperatively

to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

casei subsp, | 6 months |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

longum, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

bifidum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and

Bifidobacterium infantis |

|

|

| Park et al,

2020 | Korea | 29 | 31 | T, 60.1±10.37; | Bifidobacterium

animalis | For 7 days | (33) |

|

|

|

|

| C, 61.03±7.02 | subsp. Lactis,

Lactobacillus | preoperatively

to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| casei, and

Lactobacillus | 21 days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

plantarum |

postoperatively |

|

|

Rodríguez-Padilla | Spain | 34 | 35 | T, 65 (45–81); | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | For 20 days | (35) |

| et al,

2021 |

|

|

| C, 68 (41–80) | Lactobacillus

plantarum, | preoperatively |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

paracasei, | every second

day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactobacillus

delbrueckii |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| subsp.

bulgaricus., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

breve, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

longum, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

infantis, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Streptococcus

thermophilus |

|

|

| Huang et al,

2023 | China | 50 | 50 | T,

57.7±11.9; | Bifidobacterium

infants, | From the third | (26) |

|

|

|

|

| C,

62.1±10.5 | Lactobacillus

acidophilus, | postoperative day

to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Enterococcus

faecalis, | the end of the

first |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bifidobacterium

cereus | 6 weeks |

|

Meta-analysis results

Incidence of postoperative infection

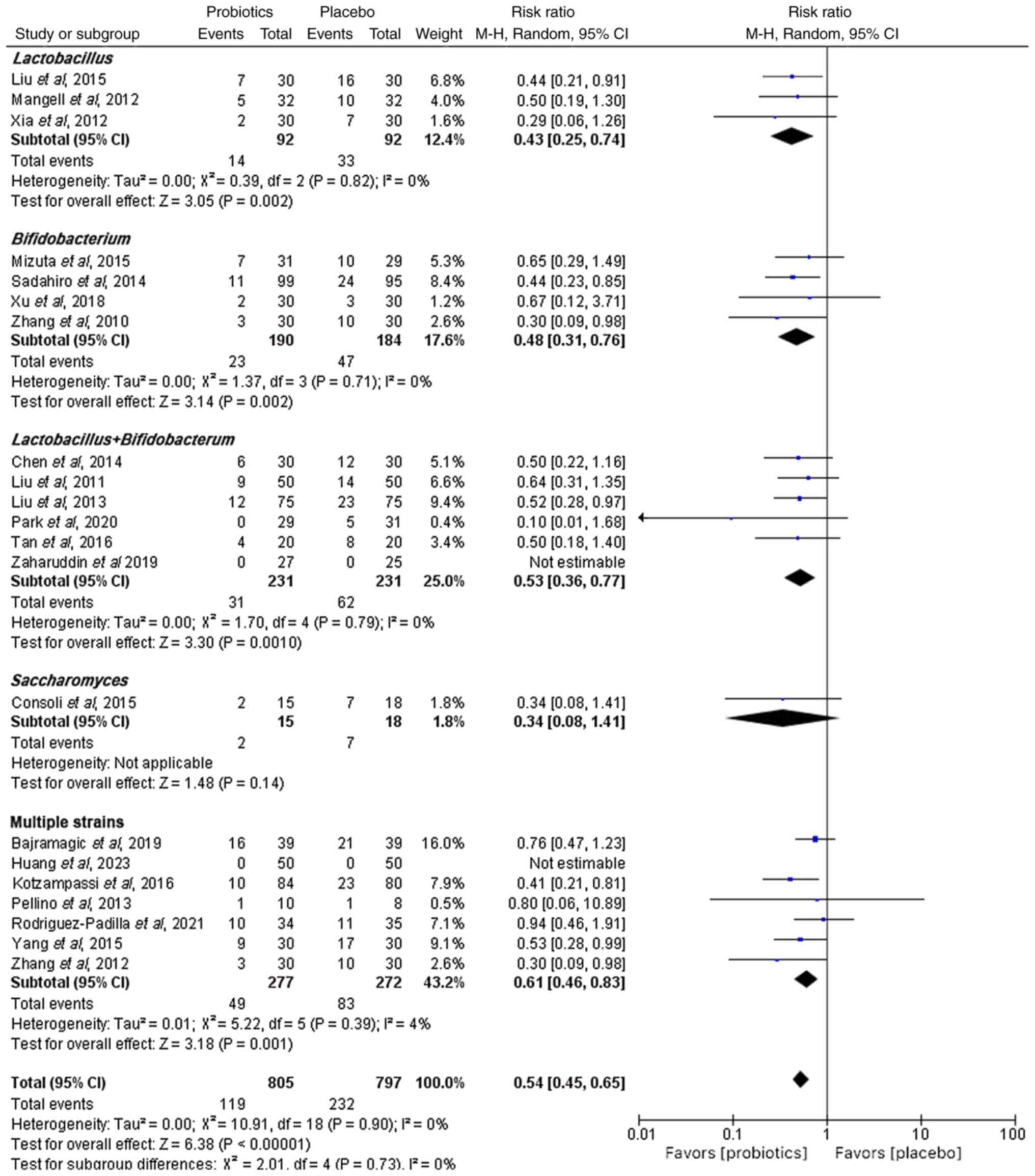

The incidence of postoperative infection was

examined in 21 studies that investigated the efficacy and safety of

probiotics as adjuvant therapy for CRC. A random-effects

meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of

postoperative infection in the probiotic group compared with that

in the placebo group (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.45–0.65; P<0.05)

(Fig. 2). Numerically, the

infection rate was 14.8% (119/805) in probiotic groups vs. 29.1%

(232/797) in controls. Given the various genera of probiotics used

in the included studies, a subgroup analysis based on probiotic

species was conducted, which revealed that using multiple strains

(RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.46–0.83; P<0.05), Lactobacillus

species (RR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.25–0.74; P<0.05),

Bifidobacterium species (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31–0.76;

P<0.05) and a combination of Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species (RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36–0.77;

P<0.05) significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative

infections compared with the placebo group. However, no significant

difference in the incidence of postoperative infections of the

single strains of Saccharomyces (RR, 0.34; 95% CI,

0.08–1.41; P>0.05) was found compared with that in placebo

group.

Mean length of hospitalization

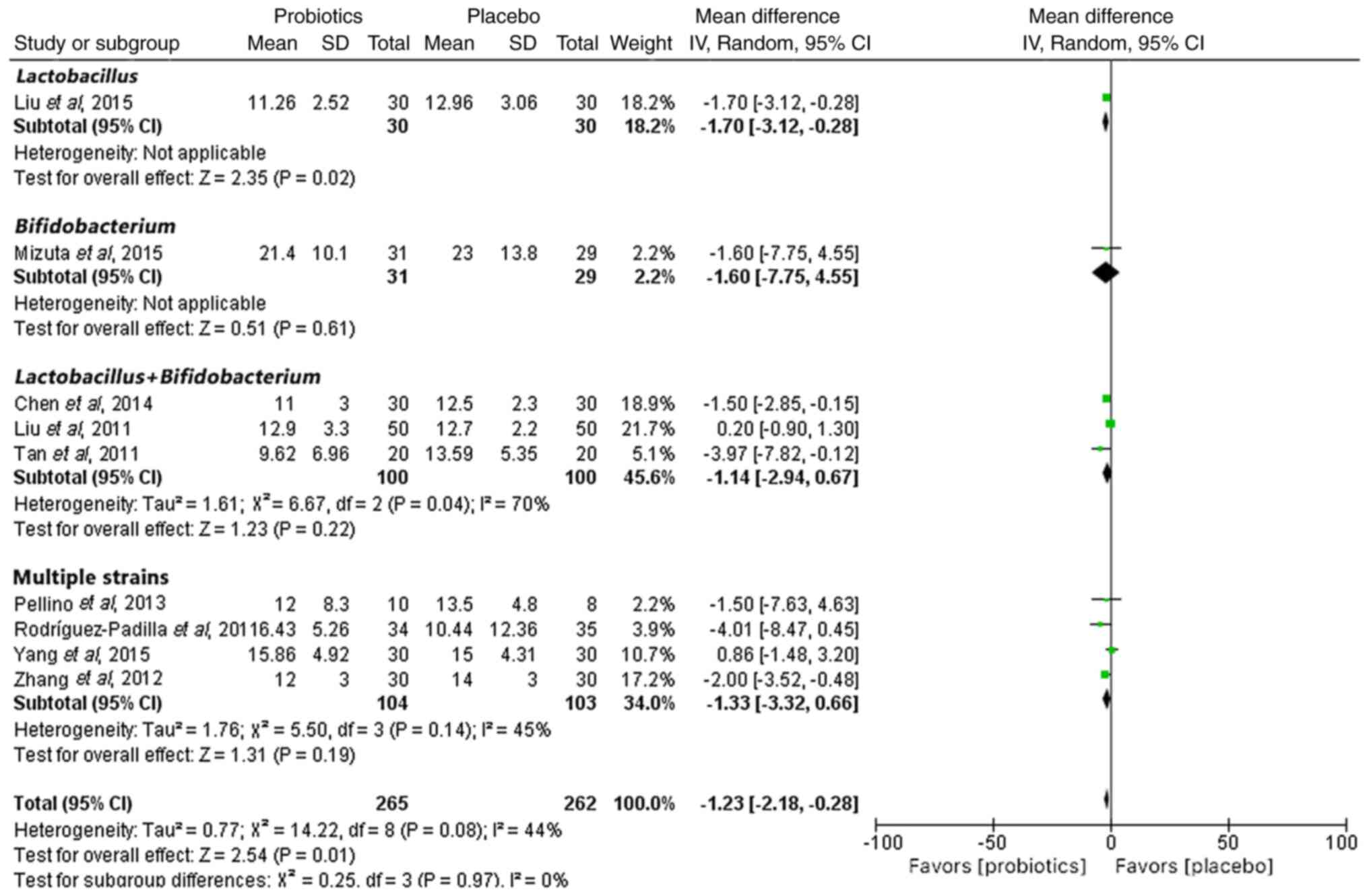

The length of hospitalization was reported in nine

of the RCTs. A random-effects meta-analysis indicated that

probiotics significantly reduced the length of hospital stay

compared with that in the placebo group (MD, −1.23; 95% CI, −2.18

to −0.28; P<0.05) (Fig. 3).

However, when analyzing the genera of probiotics used, there was no

significant reduction in the number of days of hospitalization for

any genus except for those using Lactobacillus species (MD,

−1.70; 95% CI, −3.12 to −0.28; P<0.05).

TSA of probiotics in adjuvant therapy

for CRC

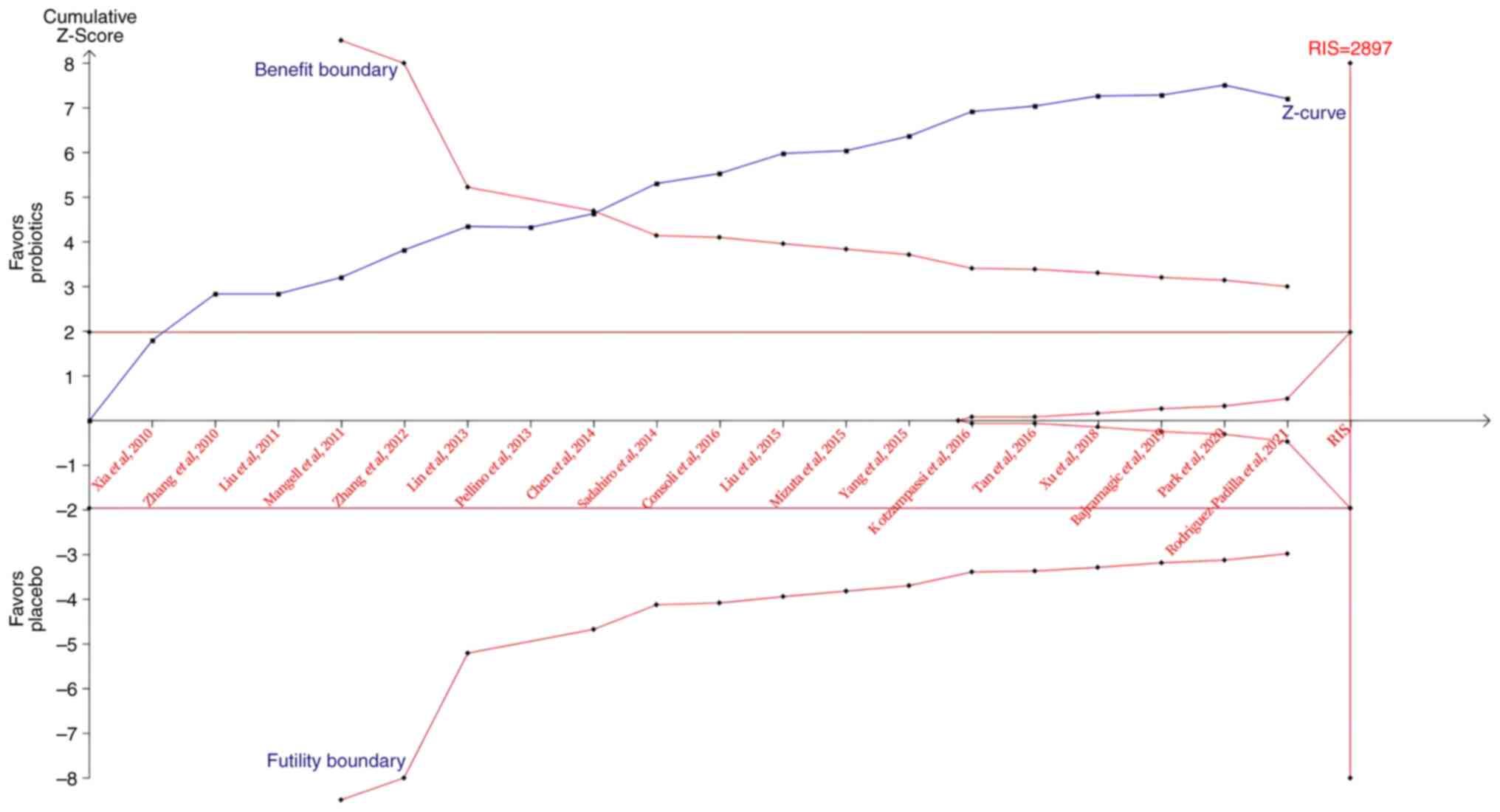

TSA results indicated that the cumulative Z-curve

crossed both the traditional and trial sequential monitoring

boundaries for benefit (Fig. 4),

which supports the fact that probiotics are effective in the

prevention of postoperative infections. Although the RIS (2,897

participants) was not reached, the results suggested no need for

further RCTs to confirm this finding.

Risk of bias and publication bias

assessment

The results of the methodological quality

assessment, which illustrate the risk of bias in the included

studies, are presented in Fig. S1.

The funnel plot, constructed using data on postoperative infection

rates, revealed an asymmetrical distribution of studies around the

funnel, which indicated the potential presence of publication bias.

Publication bias analysis is depicted in Fig. S2.

Discussion

In the realm of cancer research, there is a growing

focus on the interplay between diet, gut microbiota and CRC

(44). The human microbiota, which

consists of ~100 trillion microorganisms, forms an intricate

ecosystem that comprises bacteria, viruses, eukaryotes and archaea.

This ecosystem serves a key role in facilitating nutrient

absorption, bolstering host immunity against infections, fortifying

the intestinal immune system and regulating host metabolism

(45). Notably, the composition of

the microbiome differs between healthy individuals and those

diagnosed with CRC. The bacteria implicated in CRC to date include

Fusobacterium nucleatum, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus

gallolyticus, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis,

Escherichia coli, Peptostreptococcus spp. and

Ruminococcus spp. Conversely, species such as

Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp.,

Faecalibacterium spp., Roseburia spp.,

Clostridium spp., Granulicatella spp.,

Streptococcus thermophilus and other members of the

Lachnospiraceae family are diminished in patients with CRC

(46). Based on existing research,

persistent dysbiosis in gut microbiota diversity hinders the

efficacy of chemotherapy and promotes CRC development and

progression. Therefore, the regulation of gut microbiota has

emerged as a novel strategy for managing CRC progression (47,48).

Probiotics, recognized as potential agents that

influence the composition and functionality of human gut

microbiota, can provide therapeutic advantages in patients with CRC

when administered in appropriate dosages (49). Current clinical evidence indicates

that effective dosing typically ranges between 109 and

1011 colony-forming units per day, contingent upon

specific probiotic strains, disease status and therapeutic

objectives. Rigorous dose-finding studies remain necessary to

establish standardized protocols for CRC management (50–52).

The advantageous impacts of probiotics, which act in a species- or

strain-specific manner, encompass the preservation of a healthy

microbiome, reversal of dysbiosis, prevention of pathogenic

infections (such as, rotavirus-induced diarrhea and Clostridioides

difficile infections) and mucosal adhesion of pathogens, and

stabilization and enhancement of intestinal barrier function

(53–56). Probiotic bacteria may confer these

advantages through the production of anti-carcinogenic,

anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic and other biologically notable

compounds, such as short-chain fatty acids, which are frequently

associated with gastrointestinal disorders, including CRC (57). Another potential mechanism of

anticancer activity is the enhancement or restoration of natural

killer (NK) cell activity. NK cells serve a key role in regulating

immunity against both cancer and infections, with higher NK cell

activity being associated with a reduced risk of cancer. The

ability of probiotics to boost NK cell activity appears to be

connected to their production of IL-12 (58).

It is well established that postoperative

complications following CRC surgeries notably impact treatment

efficacy, recurrence rates and overall survival in patients.

Minimizing postoperative infection is key for the improvement of

surgical and long-term oncological outcomes. Numerous meta-analyses

have indicated the potential advantages of probiotics in mitigating

postoperative complications among patients with CRC. Persson et

al (59) focused on diarrhea as

the primary outcome, reporting an odds ratio (OR) of 0.42 (95% CI,

0.31–0.55; P<0.05). An et al (60) examined perioperative mortality,

yielding an RR of 0.17 (95% CI, 0.02–1.38; P<0.05), as well as

overall postoperative complications, yielding an RR of 0.45 (95%

CI, 0.27–0.76; P<0.05). Araújo et al (61) investigated various complications,

including ileus, which is impairment of intestinal motility (OR,

0.13; 95% CI, 0.02–0.78; P<0.05), diarrhea (OR, 0.32; 95% CI,

0.15–0.69; P<0.05), abdominal collection (OR, 0.35; 95% CI,

0.13–0.92; P<0.05), sepsis (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22–0.80;

P<0.05), pneumonia (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19–0.83; P<0.05) and

surgical site infection (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36–0.78; P<0.05).

Chen et al (62) assessed

total postoperative infections (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.15–0.64;

P<0.05) and surgical site infections (OR, 0.62; 95% CI,

0.39–0.99; P<0.05). There was no notable rise in adverse events

associated with probiotic use (63).

In the present study, the effectiveness and safety

of probiotics was examined in the prevention of postoperative

infections by incorporating unique methodological features, notably

the use of RRs instead of ORs to reduce the potential

overestimation of adverse effects associated with OR. The present

study involved a more extensive and detailed analysis, including

subgroup and TSA analyses, to evaluate evidence credibility. These

results indicated that probiotics may notably and positively

influence the reduction of postoperative infectious complications.

Postoperative infection represents a multifaceted challenge that

was intentionally not explored in depth within the present study.

Nevertheless, postoperative infection was identified as a primary

outcome due to its substantial clinical importance, as these

infections contribute to increased mortality rates and elevate both

direct and indirect healthcare expenditures. The placebo group

exhibited a postoperative infection incidence of 29.1% (232/797),

whereas the probiotic group demonstrated ~60% lower odds of

infection in patients with CRC. As a result, this outcome may

indirectly underscore the potential advantages of probiotics to

clinicians. In future research, we plan to utilize Mendelian

randomization to investigate the association between gut microbiota

and CRC prognosis. Additionally, the potential advantages of

probiotics in decreasing the mean length of hospital stay for

patients with CRC was investigated. The probiotic group experienced

a decrease in the mean number of hospitalization days by 1 day,

which led to potential cost savings in healthcare. However, it is

well established that length of hospital stay is influenced by

various confounding factors, including patient comorbidities (for

example, diabetes or coronary artery disease), psychological

conditions (for example, anxiety or depression) and the choice of

surgical approach. To mitigate the effects of these confounders, a

random-effects model was utilized. Furthermore, subgroup analyses

based on surgical techniques were performed and aimed to

standardize hospitalization duration by employing hospitalization

costs. However, this cost-based adjustment was not achievable due

to the lack of available data. Future research can include

cost-related outcomes to assess the economic benefits of probiotics

from a health economics perspective.

Furthermore, subgroup analysis indicated that the

effectiveness of various probiotic types in the prevention of

postoperative infections was evident in the combination of multiple

strains, Lactobacillus species, Bifidobacterium

species, and the combination of Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species, but not in single strains of

Saccharomyces. Additionally, smaller studies with shorter

durations tended to exhibit exaggerated effect sizes compared with

larger and longer studies. Accordingly, caution should be exercised

when interpreting the results of small, short-duration studies.

The variability in probiotic types, duration of

administration, study design and outcomes presents a challenge in

conducting TSA. While this variability was considered in the

present analysis, the assumptions regarding the results of future

large trials were based on the expectation of consistency with

existing trial findings. This assumption appears to be justified

for probiotics, given the coherence observed among the results of

large RCTs.

Despite not reaching the RIS of 2,897, the

cumulative Z-curve crossed the boundaries, which allowed a

conclusion to be reached without the need for further trials. To

the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first

application of TSA to assess the effect of probiotics on the

incidence of postoperative infections, which thereby enhances the

validity of these findings. However, the clinical application of

probiotics in CRC management poses several challenges. Variability

in study designs, probiotic formulations and patient populations

complicates the interpretation and comparison of the results.

Moreover, the optimal strains, dosages and duration of probiotic

therapy have not yet been defined. The limitations of the present

study are largely attributed to the heterogeneity of the included

trials. Several studies featured relatively small sample sizes,

which may have compromised the robustness and generalizability of

their findings. Additionally, the lack of long-term follow-up data

limits the ability to evaluate the sustained effects of probiotics

on CRC outcomes. Variations in patient demographics and clinical

settings further introduce potential statistical biases, which make

it more difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the

aggregated data.

In the past decade, research has increasingly

demonstrated the complex interplay between gut microbiota and

immune responses in maintaining physiological balance and

influencing the development, progression and treatment outcomes of

various diseases, including cancer (64–67).

Leveraging the gut mycobiome for diagnostic, prognostic and

therapeutic purposes in cancer and other disorders (such as

inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic diseases and autoimmune

conditions) demonstrates its potential in precision medicine.

Future research should prioritize large multicentre trials with

standardized protocols to strengthen the evidence for the use of

probiotics as adjunctive therapy in CRC management.

Future therapeutic strategies targeting the

microbiome or drawing inspiration from it should be designed to

modulate gut bacteria synergistically to enhance the effectiveness

of probiotics in clinical settings (68). Consequently, probiotics have the

potential to serve as a preventive measure for CRC and to enhance

treatment, thereby improving clinical outcomes for patients with

CRC in the future. The future of probiotic research in CRC should

focus on developing personalized treatment strategies and

conducting in-depth mechanistic studies. Tailoring probiotic

interventions to individual patient profiles and uncovering the

specific mechanisms through which probiotics exert their effects

will be key to realizing their full potential as adjunctive

therapies. Continued investigation in these areas will not only

enhance the current understanding of probiotics but also pave the

way for more effective targeted treatment strategies to potentially

improve outcomes for patients with CRC in the future.

In conclusion, probiotics demonstrate potential as

an effective strategy for the prevention of postoperative

infectious complications. The current meta-analysis with TSA

suggested that probiotics are efficacious in the prevention of

postoperative infections in patients undergoing colorectal

resection. Therefore, integrating probiotics into routine

perioperative care for CRC surgery may offer notable benefits for

patients in the future. However, further large-scale RCTs are

required to investigate the optimal composition, timing, duration

and dosing schedule of probiotics, particularly in patients with

immunodeficiency and dysbiosis who may be advised against probiotic

use.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Bureau of Science and

Technology of Zhoushan, Zhejiang province (grant no. 2022C31035)

and the Zhejiang Pharmaceutical Association (grant no.

2021ZYYJC04).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ, JH and WS conceptualized and designed the study,

conducted the statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. YZ,

JH, QX, FZ, YY and HY conducted data collection and wrote the

manuscript. FZ and WS are responsible for the interpretation of the

research results and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

FZ reviewed and gave final approval of the manuscript. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of People's Hospital of Putuo District (Zhoushan, China;

grant no. 2024014KYLW).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dang HX, Krasnick BA, White BS, Grossman

JG, Strand MS, Zhang J, Cabanski CR, Miller CA, Fulton RS,

Goedegebuure SP, et al: The clonal evolution of metastatic

colorectal cancer. Sci Adv. 6:eaay96912020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

GBD 2021 Diseases, Injuries Collaborators,

. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs),

disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy

(HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and

territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic

analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet.

403:2133–2161. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V,

Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N and Bray F:

Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and

mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 72:338–344. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Saffar KN, Larypoor M and Torbati MB:

Analyzing of colorectal cancerrelated genes and microRNAs

expression profiles in response to probiotics Lactobacillus

acidophilus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in colon cancer cell

lines. Mol Biol Rep. 51:1222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Türk S, Yılmaz A, Safari Baesmat A, Malkan

UY, Ucar G and Türk C: The probiotic-induced disregulation of

immune-related genes in colon cells and relation with colorectal

cancer. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 69:37–45. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Matsuda A, Maruyama H, Akagi S, Inoue T,

Uemura K, Kobayashi M, Shiomi H, Watanabe M, Arai H, Kojima Y, et

al: Do postoperative infectious complications really affect

long-term survival in colorectal cancer surgery? A multicenter

retrospective cohort study. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 7:110–120.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Guo J, Zhou B, Niu Y, Liu L and Yang L:

Engineered probiotics introduced to improve intestinal microecology

for the treatment of chronic diseases: present state and

perspectives. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 22:1029–1038. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim SH and Lim YJ: The role of microbiome

in colorectal carcinogenesis and its clinical potential as a target

for cancer treatment. Intest Res. 20:31–42. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang X, Pan L, Wang F, Long F, Yang B and

Tang D: Interventional effects of oral microecological agents on

perioperative indicators of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis.

Front Oncol. 13:12291772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Khorashadizadeh S, Abbasifar S, Yousefi M,

Fayedeh F and Moodi Ghalibaf A: The role of microbiome and

probiotics in chemo-radiotherapy-induced diarrhea: A narrative

review of the current evidence. Cancer Rep (Hoboken).

7:e700292024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

He Z, Xie H, Xu H, Wu J, Zeng W, He Q,

Jobin C, Jin S and Lan P: Chemotherapy-induced microbiota

exacerbates the toxicity of chemotherapy through the suppression of

interleukin-10 from macrophages. Gut Microbes. 16:23195112024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Imanbayev N, Iztleuov Y, Bekmukhambetov Y,

Abdelazim IA, Donayeva A, Amanzholkyzy A, Aigul Z, Aigerim I and

Aslan Y: Colorectal cancer and microbiota: Systematic review. Prz

Gastroenterol. 16:380–396. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sanders ME, Merenstein DJ, Reid G, Gibson

GR and Rastall RA: Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health

and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:605–616. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Azcárate-Peril MA, Sikes M and

Bruno-Bárcena JM: The intestinal microbiota, gastrointestinal

environment and colorectal cancer: A putative role for probiotics

in prevention of colorectal cancer? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 301:G401–G424. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Paolillo R, Romano Carratelli C,

Sorrentino S, Mazzola N and Rizzo A: Immunomodulatory effects of

Lactobacillus plantarum on human colon cancer cells. Int

Immunopharmacol. 9:1265–1271. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yuan L, Zhang S, Li H, Yang F, Mushtaq N,

Ullah S, Shi Y, An C and Xu J: The influence of gut microbiota

dysbiosis to the efficacy of 5-Fluorouracil treatment on colorectal

cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 108:184–193. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kumar A, Pramanik J, Batta K, Bamal P,

Gaur M, Rustagi S, Prajapati BG and Bhattacharya S: Impact of

metallic nanoparticles on gut microbiota modulation in colorectal

cancer: A review. Cancer Innov. 3:e1502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao J, Liao Y, Wei C, Ma Y, Wang F, Chen

Y, Zhao B, Ji H, Wang D and Tang D: Potential ability of probiotics

in the prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer. Clin Med

Insights Oncol. 17:117955492311882252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu J, Ma X, Wang X, Zhu G, Wang H, Zhang Y

and Li J: Efficacy and safety of compound kushen injection for

advanced colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

of randomized clinical trials with trial sequential analysis.

Integr Cancer Ther. 23:153473542412584582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Higgins JP, Savovic J and Page MJ: Chapter

8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. Cochrane Handbook

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Higgins JP,

Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al: Cochrane;

2021, Available from:. training.cochrane.org/handbook

|

|

22

|

Weng H, Li S and Zeng XT: Application of

the trial sequential analysis soft ware for meta-analysis. Chin J

Evid-Based Med. 16:604–611. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

23

|

Bajramagic S, Hodzic E, Mulabdic A, Holjan

S, Smajlovic SV and Rovcanin A: Usage of probiotics and its

clinical significance at surgically treated patients sufferig from

colorectal carcinoma. Med Arch. 73:316–320. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen H, Xia Y, Shi C, Liang Y, Yang Y and

Qin H: Effects of perioperative probiotics administration on

patients with colorectal cancer. Chin J Clin Nutr. 22:82014.(In

Chinese).

|

|

25

|

Consoli ML, da Silva RS, Nicoli JR,

Bruña-Romero O, da Silva RG, de Vasconcelos Generoso S and Correia

MI: Randomized clinical trial: Impact of oral administration of

saccharomyces boulardii on gene expression of intestinal cytokines

in patients undergoing colon resection. JPEN J Parenter Enteral

Nutr. 40:1114–1121. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huang F, Li S, Chen W, Han Y, Yao Y, Yang

L, Li Q, Xiao Q, Wei J, Liu Z, et al: Postoperative Probiotics

administration attenuates gastrointestinal complications and gut

microbiota dysbiosis caused by chemotherapy in colorectal cancer

patients. Nutrients. 15:3562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kotzampassi K, Stavrou G, Damoraki G,

Georgitsi M, Basdanis G, Tsaousi G and Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ: A

Four-Probiotics regimen reduces postoperative complications after

colorectal surgery: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

study. World J Surg. 39:2776–2783. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu Z, Qin H, Yang Z, Xia Y, Liu W, Yang

J, Jiang Y, Zhang H, Yang Z, Wang Y and Zheng Q: Randomised

clinical trial: The effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on

barrier function and post-operative infectious complications in

colorectal cancer surgery - a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther. 33:50–63. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu ZH, Huang MJ, Zhang XW, Wang L, Huang

NQ, Peng H, Lan P, Peng JS, Yang Z, Xia Y, et al: The effects of

perioperative probiotic treatment on serum zonulin concentration

and subsequent postoperative infectious complications after

colorectal cancer surgery: A double-center and double-blind

randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 97:117–126. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu Z, Li C, Huang M, Tong C, Zhang X,

Wang L, Peng H, Lan P, Zhang P, Huang N, et al: Positive regulatory

effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on postoperative liver

complications after colorectal liver metastases surgery: A

double-center and double-blind randomized clinical trial. BMC

Gastroenterol. 15:342015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mangell P, Thorlacius H, Syk I, Ahrné S,

Molin G, Olsson C and Jeppsson B: Lactobacillus plantarum 299v does

not reduce enteric bacteria or bacterial translocation in patients

undergoing colon resection. Dig Dis Sci. 57:1915–1924. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mizuta M, Endo I, Yamamoto S, Inokawa H,

Kubo M, Udaka T, Sogabe O, Maeda H, Shirakawa K, Okazaki E, et al:

Perioperative supplementation with bifidobacteria improves

postoperative nutritional recovery, inflammatory response, and

fecal microbiota in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: A

prospective, randomized clinical trial. Biosci Microbiota Food

Health. 35:77–87. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Park IJ, Lee JH, Kye BH, Oh HK, Cho YB,

Kim YT, Kim JY, Sung NY, Kang SB, Seo JM, et al: Effects of

probiotics on the symptoms and surgical ouTComes after anterior

REsection of colon cancer (POSTCARE): A randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Med. 9:21812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Candilio G,

Camerlingo A, Marcellinaro R, De Fatico S, Rocco F, Canonico S,

Riegler G and Selvaggi F: Early postoperative administration of

probiotics versus placebo in elderly patients undergoing elective

colorectal surgery: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC

Surg. 13 (Suppl 2):S572013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rodríguez-Padilla Á, Morales-Martín G,

Pérez-Quintero R, Gómez-Salgado J, Balongo-García R and Ruiz-Frutos

C: Postoperative ileus after stimulation with probiotics before

ileostomy closure. Nutrients. 13:6262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Tanaka A, Okada K,

Kamata H, Ozaki T and Koga Y: Comparison between oral antibiotics

and probiotics as bowel preparation for elective colon cancer

surgery to prevent infection: Prospective randomized trial.

Surgery. 155:493–503. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tan CK, Said S, Rajandram R, Wang Z,

Roslani AC and Chin KF: Pre-surgical administration of microbial

cell preparation in colorectal cancer patients: A randomized

controlled trial. World J Surg. 40:1985–1992. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xia Y, Yang Z, Chen HQ and Qin HL: Effect

of bowel preparation with probiotics on intestinal barrier after

surgery for colorectal cancer. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi.

13:528–531. 2010.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu Q, Xu P, Cen Y and Li W: Effects of

preoperative oral administration of glucose solution combined with

postoperative probiotics on inflammation and intestinal barrier

function in patients after colorectal cancer surgery. Oncol Lett.

18:694–698. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang Y, Xia Y, Chen H, Hong L, Feng J,

Yang J, Yang Z, Shi C, Wu W, Gao R, et al: The effect of

perioperative probiotics treatment for colorectal cancer:

short-term outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Oncotarget.

7:8432–8440. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zaharuddin L, Mokhtar NM, Muhammad Nawawi

KN and Raja Ali RA: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled

trial of probiotics in post-surgical colorectal cancer. BMC

Gastroenterol. 19:1312019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang W, Du P, Chen D, Cui L and Ying C:

Effect of viable bifidobacterium supplementon theimmune statusand

inflanunatory response inpatients undergoing resection for

colorectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 13:40. 2010.

|

|

43

|

Zhang JW, Du P, Gao J, Yang BR, Fang WJ

and Ying CM: Preoperative probiotics decrease postoperative

infectious complications of colorectal cancer. Am J Med Sci.

343:199–205. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yu J, Nong C, Zhao J, Meng L and Song J:

An integrative bioinformatic analysis of microbiome and

transcriptome for predicting the risk of colon adenocarcinoma. Dis

Markers. 2022:79940742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chang H, Lei L, Zhou Y, Ye F and Zhao G:

Dietary flavonoids and the risk of colorectal cancer: An updated

meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Nutrients. 10:9502018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Al-Nemari R, Al-Senaidy A, Semlali A,

Ismael M, Badjah-Hadj-Ahmed AY and Ben Bacha A: GC-MS profiling and

assessment of antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer properties

of extracts of Annona squamosa L. leaves. BMC Complement Med Ther.

20:2962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L,

Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, Prieto PA, Vicente D, Hoffman

K, Wei SC, et al: Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1

immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 359:97–103. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wong CC and Yu J: Gut microbiota in

colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

20:429–452. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Sun L, Zhu Z, Jia X, Ying X, Wang B, Wang

P, Zhang S and Yu J: The difference of human gut microbiome in

colorectal cancer with and without metastases. Front Oncol.

12:9827442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang W, An Y, Qin X, Wu X, Wang X, Hou H,

Song X, Liu T, Wang B, Huang X and Cao H: Gut microbiota-derived

metabolites in colorectal cancer: The bad and the challenges. Front

Oncol. 11:7396482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR,

Merenstein DJ, Pot B, Morelli L, Canani RB, Flint HJ, Salminen S,

et al: Expert consensus document. The international scientific

association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on

the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11:506–514. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E and Elinav E: The

pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat Med. 25:716–729.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sonnenburg JL and Bäckhed F:

Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism.

Nature. 535:56–64. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Szajewska H and Kołodziej M: Systematic

review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the

prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther. 42:793–801. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Szajewska H, Guarino A, Hojsak I, Indrio

F, Kolacek S, Shamir R, Vandenplas Y and Weizman Z; European

Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Nutrition, :

Use of probiotics for management of acute gastroenteritis: A

position paper by the ESPGHAN Working Group for Probiotics and

Prebiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 58:531–539. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Cani PD and Jordan BF: Gut

microbiota-mediated inflammation in obesity: A link with

gastrointestinal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:671–682.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Huang HC, Cai BH, Suen CS, Lee HY, Hwang

MJ, Liu FT and Kannagi R: BGN/TLR4/NF-B mediates epigenetic

silencing of immunosuppressive siglec ligands in colon cancer

cells. Cells. 9:3972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wu R, Shen Q, Li P and Shang N: Sturgeon

chondroitin sulfate restores the balance of gut microbiota in

colorectal cancer bearing mice. Int J Mol Sci. 23:37232022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Persson JE, Viana P, Persson M, Relvas JH

and Danielski LG: Perioperative or postoperative probiotics reduce

treatment-related complications in adult colorectal cancer patients

undergoing surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J

Gastrointest Cancer. 55:740–748. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

An S, Kim K, Kim MH, Jung JH and Kim Y:

Perioperative probiotics application for preventing postoperative

complications in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 58:16442022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Araújo MM, Montalvão-Sousa TM, Teixeira

PDC, Figueiredo ACMG and Botelho PB: The effect of probiotics on

postsurgical complications in patients with colorectal cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 81:493–510. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chen C, Wen T and Zhao Q: Probiotics used

for postoperative infections in patients undergoing colorectal

cancer surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2020:57347182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen Y, Qi A, Teng D, Li S, Yan Y, Hu S

and Du X: Probiotics and synbiotics for preventing postoperative

infectious complications in colorectal cancer patients: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 26:425–436.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Jaye K, Li CG and Bhuyan DJ: The complex

interplay of gut microbiota with the five most common cancer types:

From carcinogenesis to therapeutics to prognoses. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 165:1034292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, Smith L,

Bouladoux N, Weingarten RA, Molina DA, Salcedo R, Back T, Cramer S,

et al: Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by

modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. 342:967–970. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong

CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M, Rauber C,

Roberti MP, et al: Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based

immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 359:91–97. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Belkaid Y and Hand TW: Role of the

microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 157:121–41. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhang F, Aschenbrenner D, Yoo JY and Zuo

T: The gut mycobiome in health, disease, and clinical applications

in association with the gut bacterial microbiome assembly. Lancet

Microbe. 3:e969–e983. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|