Introduction

Meibomian gland carcinoma (MGC) is a malignant tumor

arising from the meibomian glands of the eyelid, characterized by

pronounced local invasiveness and a high propensity for metastasis

to regional lymph nodes and distant organs (1,2). The

overall incidence of SGC is ~2 cases per 100,000 person-years. The

mortality rate of this disease has decreased from 50% to 2–10%

(3,4). The early clinical manifestations of

MGC are often subtle and non-specific, frequently leading to

misdiagnosis or confusion with benign inflammatory conditions such

as meibomian gland cysts. This diagnostic challenge often results

in delayed treatment, thereby increasing the likelihood of tumor

invasion and metastasis (5,6). Despite surgical resection being the

current mainstay of treatment, the postoperative recurrence rate

remains high, reaching up to 40% (5). To date, the molecular mechanisms

underlying the pathogenesis and progression of MGC remain largely

unclear, both domestically and internationally.

Our previous study successfully established and

characterized cell models of MGC and normal meibomian gland cells

through primary culture of freshly excised surgical tissue,

followed by differential gene expression analysis (7). Using microRNA (miRNA or miR)

microarray technology, miR-3907 was identified as notably

upregulated in MGC tissues compared with in adjacent non-tumorous

tissues. Bioinformatic analyses, along with dual-luciferase

reporter assays, confirmed that thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) is a

direct target of miR-3907. Functional experiments further

demonstrated that miR-3907 promotes the proliferation and migration

of MGC cells by downregulating THBS1 expression (8). THBS1, a well-established tumor

suppressor, is notably downregulated in MGC, where it normally

functions to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis. As an

extracellular matrix protein, THBS1 serves a critical role in tumor

progression and dissemination across multiple cancer types

(9,10). For instance, its expression has been

associated with clinical parameters such as tumor-node-metastasis

staging and lymph node metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell

carcinoma, and it has been reported to influence the

trans-epithelial migration of breast cancer cells (11,12).

Building upon the identification of the miR-3907-THBS1 regulatory

axis, the present study aimed to further elucidate the role of

chitobiosyldiphosphodolichol β-mannosyltransferase 1 (ALG1), a

downstream effector protein. Due to the inherent limitations in

delivering miR-3907 and the challenges posed by THBS1 as a large

extracellular matrix protein for clinical drug administration

(13), targeting ALG1 may offer a

more practical therapeutic approach. ALG1, being amenable to

inhibition by small-molecule compounds (14), represents a feasible downstream

target for rapid clinical translation. Moreover, a comprehensive

investigation of the entire ‘miRNA-target gene-effector protein’

pathway not only enhances mechanistic specificity but also

facilitates the development of tiered therapeutic strategies.

Proteomics, as a cutting-edge tool for systematically profiling

protein expression and function in biological systems, provides

powerful means to elucidate disease pathogenesis and progression,

and to uncover novel therapeutic targets (15,16).

Our research group performed a preliminary proteomic analysis of

MGC after overexpressing THBS1 and identified certain

differentially expressed proteins. However, in-depth functional

validation of these proteins has not been performed (17).

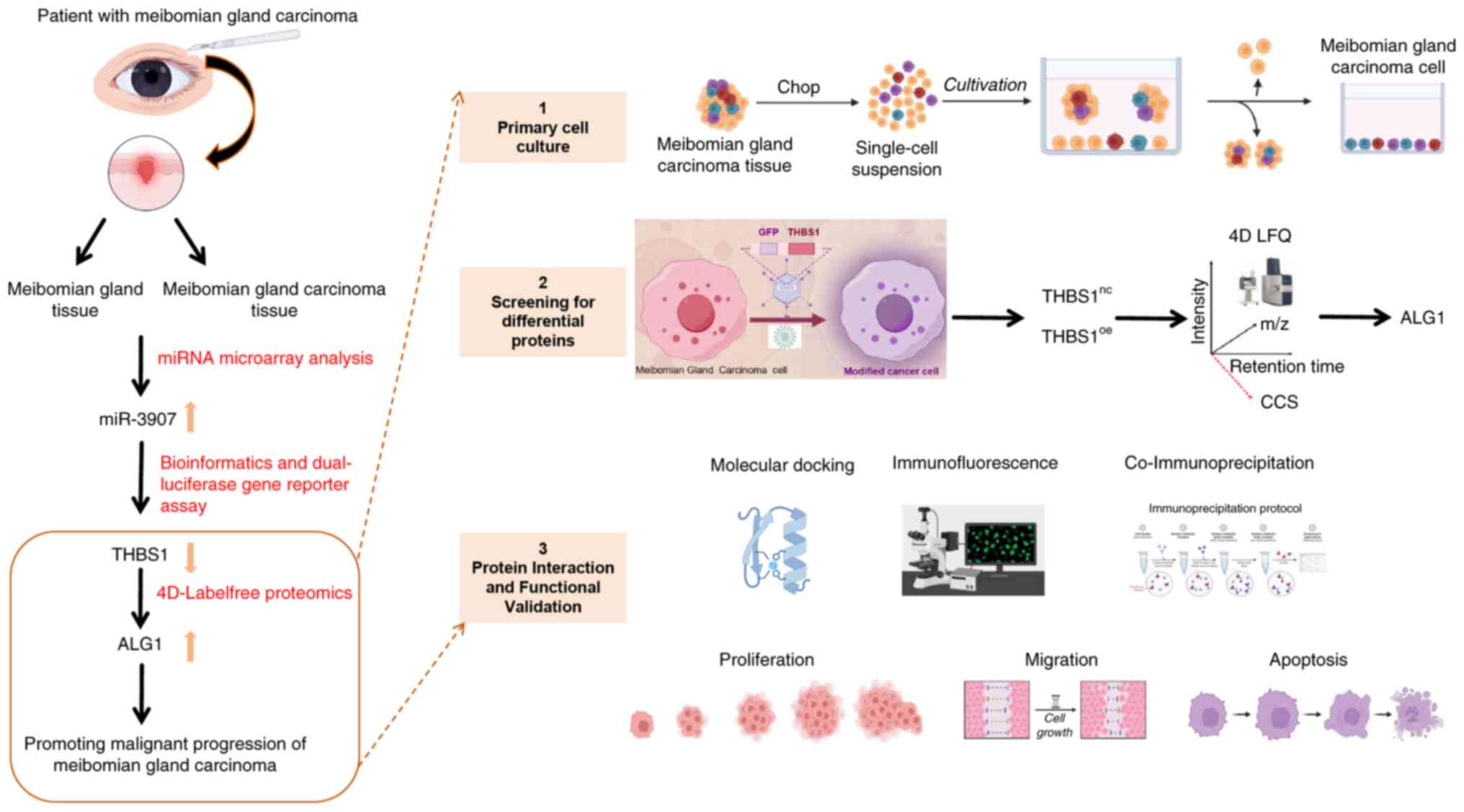

The present study aimed to comprehensively assess

the downstream regulatory mechanisms of THBS1 in MGC. Utilizing 4D

label-free quantitative proteomics, differentially expressed

proteins (DEPs) were identified between THBS1-overexpressing and

control groups. Among these, ALG1 exhibited the most significant

fold change and was selected as the primary focus of the present

research. Furthermore, the functional role and molecular mechanisms

of ALG1 within the miR-3907/THBS1/ALG1 regulatory axis were

evaluated, with particular emphasis on its influence on MGC cell

behavior and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The findings

of the present study provide new insights into the

post-transcriptional regulatory network of MGC and offer promising

avenues for the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers and

targeted therapeutic strategies. The experimental workflow of the

present study is presented in Fig.

1.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following materials were used in the present

study: RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), trypsin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), dimethyl

sulfoxide (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.),

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), RNA extraction kit (EZBioscience),

first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (EZBioscience), quantitative

real-time PCR kit (EZBioscience), total protein extraction kit

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), BCA protein

concentration assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.), apoptosis detection kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.).

Primary cell culture

In our previous research, fresh MGC tissues and

adjacent paracancerous tissues were obtained from patients

undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery (8). The primary cells used in the present

study were derived from these tissue samples. Informed consent in

writing from patients for all samples was obtained prior to the

aforementioned published study. Moreover, the primary MGC cells

were previously isolated, identified and characterized using Oil

Red O staining and immunofluorescence, leading to the successful

establishment of three primary MGC cell lines (7). Cells in the logarithmic growth phase

between passages 4 and 10 were selected for all experiments. They

were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (HyClone; Cytiva), and maintained at 37°C

in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days.

Once cell confluence reached ~90%, the cells were harvested and

used for subsequent assays. The study protocol was approved by the

Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital

[Tianjin, China; approval no. 2020KY(L)-20].

Cell transfection and lentiviral

overexpression

For small interfering (si)RNA-mediated gene

knockdown experiments, siRNAs targeting ALG1 and negative control

siRNAs were synthesized by OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The

ALG1-specific siRNA sequences included a sense strand

(5′-GAUCCUGCGGGCAAGCUAATT-3′) and an antisense strand

(5′-UUAGCUUGCCCGCAGGAUCTT-3′), and the negative control siRNA

sequences included a sense strand (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′) and

an antisense strand (5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′). The siRNA was

used at a final concentration of 50 nM for cell transfection. When

preparing the transfection reagent, 50 µl Opti-MEM (BasalMedia) was

used to dilute the siRNA, which was gently pipetted up and down to

mix. Separately, 1.0 µl Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was diluted with 50 µl Opti-MEM,

gently pipetted to mix and incubated at room temperature for 5 min.

The diluted transfection reagent and siRNA solution were then

combined and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After siRNA

transfection, mRNA levels were detected 24–48 h later, whilst

protein levels were analyzed after 48–96 h.

Lentiviral overexpression was performed using a

second-generation packaging system [OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Co.,

Ltd.] consisting of pSLenti-SFH-EGFP-P2A-Puro-CMV-THBS1-3×FLAG-WPRE

(THBS1OE) or

pcSLenti-EF1-EGFP-P2A-Puro-CMV-ALG1-3×FLAG-WPRE (ALG1OE)

as transfer plasmids, with corresponding empty vectors serving as

negative controls. The mass of lentiviral vector plasmid was 2 µg,

and the ratio of vector plasmid: packaging plasmid: envelope

plasmid was 2:1.5:0.5. The packaging plasmid mixture (backbone:

Shuttle=1:1; total=32 µg) was transfected into 293T cells (American

Type Culture Collection) using Trans-fect Lentiviral Packaging

Transfection Reagent [OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.]

following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded

in a 100-mm dish to achieve a confluency of 70–80% at the time of

transfection. Plasmids and reagents were separately diluted in 500

µl Opti-MEM, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, combined and

further incubated at room temperature for 20 min to form complexes.

After the medium was replaced with 10 ml Opti-MEM, the complexes

were added to the cells. A total of 6–8 h post-transfection, the

medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. Viral supernatants

were harvested at 48 and 72 h post-transfection, pooled,

centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature to remove

debris, filtered through 0.22-µm membranes, and ultracentrifuged at

100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in

pre-cooled DPBS, incubated overnight at 4°C, filtered again,

aliquoted and stored at −80°C. For transduction, MGC cells were

seeded in a 24-well plate to reach 30–40% confluency and infected

with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 40 (determined by

pre-experiment) in the presence of 5 µg/ml polybrene. A total of

8–12 h post-infection, the medium was replaced and the cells were

cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. Transduced cells were

selected using 5 µg/ml puromycin for 7–10 days, with medium changes

every 24–48 h. In the maintenance phase, cells were cultured in

medium containing 1 µg/ml puromycin.

Protein extraction

A total of 300 µl 8M urea was added to each primary

cell sample for protein lysis, and a protease inhibitor cocktail

was added at a concentration of 10% (v/v) of the total lysis

volume. The lysates were centrifuged at 14,100 × g for 20 min at

4°C and the supernatants were carefully collected. Protein

concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay. The

remaining lysates were stored at −80°C for subsequent analyses.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis

Protein digestion was performed using a commercial

micro-protease digestion kit. Briefly, 20 µl protein lysate was

mixed with MMB magnetic beads in an eight-tube strip and incubated

at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, 45 µl binding buffer was added,

followed by a 15-min incubation at room temperature. After

discarding the supernatant, the beads were washed three times with

wash buffer. Proteins were then resuspended in 20 µl digestion

solution and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. The reaction was terminated

by adding 5 µl quenching buffer, and the resulting peptides were

freeze-dried. For LC-MS/MS analysis, two mobile phases were

prepared: Mobile phases A (100% water with 0.1% formic acid) and B

(80% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). The freeze-dried peptide

samples were reconstituted in 10 µl mobile phase A and centrifuged

at 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then subjected

to LC-MS/MS analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed

under the conditions specified in Table

I. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on a timsTOF_HT

instrument (Bruker Corporation) equipped with a Captive Spray ion

source, operating in data-dependent acquisition mode. The

ionization was conducted in positive ion mode. The nitrogen gas

temperature was 200°C, the nebulizer pressure at 17.4 psi, and the

nitrogen flow rate at 10 l/min. The mass scan range was set to m/z

100–1,700. The resolution for MS1 spectra was set to 60,000 at m/z

1,222. Within the TIMS tunnel, the ion accumulation time was 100

msec, and the ion mobility range was 0.6–1.6 cm2/V. A

total cycle time of 1.1 sec was used, incorporating 10 parallel

accumulation-serial fragmentation scans. Raw mass spectrometry data

were acquired for further analysis.

| Table I.Elution conditions for liquid

chromatography, with a separation flow rate of 500 nl/min, and the

separation gradients. |

Table I.

Elution conditions for liquid

chromatography, with a separation flow rate of 500 nl/min, and the

separation gradients.

| Time, min | Proportion of

mobile phase B, % |

|---|

| 00:00 | 3.5 |

| 17:00 | 32.0 |

| 18:00 | 95.0 |

| 20:00 | 95.0 |

| 21:00 | 1.0 |

| 22:00 | 1.0 |

Protein identification and

quantification

All RAW files generated from mass spectrometry were

analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer software suite (version 2.4;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). MS/MS spectra were searched

against the Homo sapiens UniProt Swiss-Prot proteome database

(uniprot.org/)(20,407 target sequences; downloaded on March 7,

2023). Furthermore, the Sequest HT search engine(used in Proteome

Discoverer software) was employed with the following parameters:

Fully tryptic enzyme specificity, allowing up to two missed

cleavages, and a minimum peptide length of six amino acids.

Carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.02146 Da) was set as

a fixed modification, whilst oxidation of methionine residues

(+15.99492 Da) was considered a variable modification. The

precursor mass tolerance was set to 15 ppm, and the fragment mass

tolerance was 0.02 Da for MS/MS spectra acquired in the Orbitrap.

Peptide spectral matches and peptides were filtered using the

Percolator algorithm (percolator.ms/) to achieve a false discovery

rate (FDR) <1%. Following spectral assignment, peptides were

assembled into proteins and further filtered based on the combined

probability scores of constituent peptides, maintaining a final

protein-level FDR of 1%. By default, the top-ranked or ‘master’

protein was defined as the one with the highest number of unique

peptides and the lowest percent peptide coverage value (namely, the

longest matching protein). Only unique and razor (parsimonious)

peptides were considered for quantification.

Functional analysis of proteins and

DEPs

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed

using the InterProScan 5 tool (ebi.ac.uk/interpro), based on

annotations from the non-redundant protein database. Pathway

analysis was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) database (genome.jp/kegg/) to identify functionally

relevant signaling pathways. Protein-protein interaction networks

were predicted using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/), which integrates both known

and predicted interactions based on orthologous relationships

across species (18). GO and KEGG

enrichment analyses were performed using a dedicated enrichment

pipeline to further interpret the biological significance of

DEPs.

Global analysis, differential protein

screening and functional annotation

Differential expression analysis was performed using

the Significance A algorithm within the MaxQuant software suite

(version 2.6.4.0, available at http://www.biochem.mpg.de/6304115/maxquant). A

paired-sample t-test was employed to compare protein expression

levels between the experimental and control groups. Proteins

exhibiting an absolute log2 fold change (FC) of >1.5

and a P-value of <0.05 were considered significantly

differentially expressed. Among these, ALG1 was identified as the

protein with the highest fold change based on the proteomics

sequencing data. To further assess the functional and biological

relevance of the DEPs, bioinformatic analyses were performed using

the GO and the KEGG pathway databases, enabling a systematic

understanding of the molecular functions, biological processes and

pathways in which the DEPs are involved.

RNA extraction and quantitation

RNA was extracted from the collected primary cells

using a commercial RNA extraction kit(Cat.No.:B0004DP,

EZBioscience), followed by reverse transcription into cDNA using a

specific reverse transcription kit(Cat.No.:A0010CGQ,EZBioscience),

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using the 2×

Color SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix(Cat.No.:A0012-R1,EZBioscience).

The amplification protocol consisted of an initial denaturation

step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at

95°C for 10 sec, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec.

Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (19),

with GAPDH employed as the internal control for normalization.

Primer sequences used in the present study are listed in Table II.

| Table II.Primer sequences. |

Table II.

Primer sequences.

|

| Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| ALG1 |

CCCCGAGTTTTCCAGTACGG |

CAGCAATGCTAGGCAGACCT |

| THBS1 |

AGACTCCGCATCGCAAAGG |

TCACCACGTTGTTGTCAAGGG |

| BAX |

CCCGAGAGGTCTTTTTCCGAG |

CCAGCCCATGATGGTTCTGAT |

| BCL-2 |

GGTGGGGTCATGTGTGTGG |

CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCC |

| E-CADHERIN |

TGGACCGAGAGAGTTTCCCT |

CAAAATCCAAGCCCGTGGTG |

| N-CADHERIN |

TCAGGCGTCTGTAGAGGCTT |

ATGCACATCCTTCGATAAGACTG |

| VIMENTIN |

AATGACCGCTTCGCCAACT |

ATCTTATTCTGCTGCTCCAGGAA |

| GAPDH |

GATGCTGGCGCTGAGTACG |

GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGC |

Western blot

Cell lysates were prepared by resuspending cells in

a lysis buffer (cat. no. #BC3710,Solarbio) and incubating them on

ice for 30 min. The lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for

30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected for protein

concentration determination using a BCA assay. A total of 25

µg/lane protein was separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred

onto PVDF membranes. To block nonspecific binding, membranes were

blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes

were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies

against THBS1 (1:1,000, Affinity, DF6848), β-actin (1:8,000,

Affinity, AF7018), ALG1 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 12872-1-AP), GAPDH

(1:1,000, Affinity, cat. no. AF7021), Bax (1:1,000, Affinity,

AF0120), and BCL-2 (1:1,000, Affinity, AF6139). After three washes

with TBST (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

containing 0.1% Tween-20, membranes were incubated with goat

anti-rabbit IgG(H+L)-HRP(1:7,000, Affinity, S0001) for 2 h at room

temperature. Following an additional three washes, protein bands

were visualized using an ECL detection kit(CAT:SQ201,EpiZyme), and

images were captured using a chemiluminescence imaging

system(Catalog number: Tanon 4600, Shanghai Tianneng Technology

Co., Ltd.). Semi-quantification of protein expression was performed

using ImageJ software (Version 1.8.0, National Institutes of

Health) by measuring the band intensities. The relative expression

level of each target protein was calculated as the ratio of its

band intensity to that of the internal loading control.

Bioinformatics analysis

To assess the expression patterns of the target gene

ALG1 across several tumor types, data were retrieved from

the publicly available Tumor Immune Estimation Resource, version 2

(TIMER2.0) database (http://timer.cistrome.org/) using the ‘Gene DE’

module. Additionally, expression levels of ALG1 in tumor compared

with in adjacent normal tissues were analyzed based on datasets

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; portal.gdc.cancer.gov/1) to

evaluate its differential expression profile.

Protein-protein docking

The three-dimensional structures of THBS1 and ALG1

proteins were retrieved from the UniProt database (www.uniprot.org), the Protein Data Bank (rcsb.org/),

and the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database

(alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/). Rigid protein-protein docking was performed

using GRAMM-X software (http://vakser.bioinformatics.ku.edu/resources/gramm/grammx)

to predict the potential interaction interface between THBS1 and

ALG1. The resulting docking models were analyzed and visualized

using PyMOL software (version 2.4, http://pymol.org/) to further interpret the nature of

the molecular interactions.

Immunofluorescence

co-localization

Cells were cultured on sterilized glass coverslips

until reaching ~80% confluency. Following three washes with PBS for

5 min each, cells were fixed with pre-chilled methanol at −20°C for

5 min. After fixation, non-specific binding sites were blocked

using 5% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, followed by PBS

washing. Primary antibodies against THBS1 (cat. no. AB1823, Abcam)

and ALG1 (cat. no. 12872-1-AP, Proteintech) (1:100) were

co-incubated with the cells overnight at 4°C. After washing with

PBS, cells were incubated with the following fluorescently labeled

secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature: Goat anti-rabbit

DyLight 488 (A23220, Abbkine) and goat anti-mouse DyLight 594

(A23410, Abbkine). Nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5 min at room

temperature, followed by further PBS washes. Coverslips were then

mounted using the antifade mounting medium, and samples were

observed using a confocal fluorescence microscope (LSM 800; Carl

Zeiss AG).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-Ip)

A total of ~50 µl each MGC cell protein lysate,

prepared using NP-40 lysis buffer (N8032,Solarbio), was reserved as

an input control. The remaining sample was adjusted to a total

volume of 300 µl, containing ~900 µg protein. To each sample, 30 µl

50% Protein A agarose beads were added, followed by incubation on

ice for 45 min to pre-clear the lysates. Samples were then

centrifuged at 700 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were

collected whilst the pellets were discarded. For

immunoprecipitation, 200 µl pre-cleared supernatant (~600 µg

protein) was incubated with 7 µl of the primary antibody against

THBS1 (cat. no. AB263905, Abcam) or ALG1 (12872-1-AP, Proteintech),

whilst 100 µl (equivalent to ~300 µg protein) was incubated with

3.5 µl control IgG. Both mixtures were rotated overnight at 4°C.

The following day, 30 µl of 50% agarose beads were added to the

antibody sample, and 10 µl beads were added to the IgG control.

Samples were then incubated for an additional 4 h at 4°C under

constant rotation. After centrifugation under the aforementioned

conditions, the supernatants were collected as negative controls.

The beads were washed five times with 0.5 ml ice-cold PBS, and the

first wash supernatant was retained for analysis. Subsequently, the

beads were resuspended in 30 µl of 1X SDS loading buffer and boiled

at 95°C for 5 min. The resulting immunoprecipitates were analyzed

using western blotting as aforementioned to assess protein-protein

interactions.

CCK-8 assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay.

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of

5×103 cells per well. Cell proliferation was evaluated

at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. At each time point, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent was

added to each well. Plates were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C, and

the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader

(Tecan Group, Ltd.).

Wound-healing assay

When cells reached ~90% confluence, a linear scratch

was made across the cell monolayer using a sterile 100 µl pipette

tip. Detached cells were removed by washing with PBS, and the

medium was replaced with a complete medium containing 1% FBS.

Images of the wound area were captured at 0 and 24 h using an

inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation). The cell migration rate

was calculated using the following formula: Cell migration rate

(%)=[(Width at 0 h-width at 24 h)/width at 0 h]-x100.

Transwell assay

Cell migration and invasion were evaluated using

Transwell chambers. Migration assays were performed without

Matrigel (cat. no. CLS3422, Corning, Inc.), whilst invasion assays

used chambers pre-coated with Matrigel (CLS354480; Corning, Inc.).

Cells were harvested, counted and resuspended in a serum-free

medium at a density of 1×106 cells/ml. A total of 200 µl

cell suspension was added to the upper chamber, whilst 500 µl

complete medium containing 20% FBS (ExCell Bio) was added to the

lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 48 h of incubation at

37°C, the contents of both chambers were removed. Non-migratory or

non-invasive cells on the upper surface of the membrane were

carefully wiped off with a cotton swab. The chambers were washed

with PBS, and cells on the lower membrane surface were fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. Following

air-drying, the membranes were stained with 0.1% crystal violet at

room temperature for 20 min. After washing twice with PBS, stained

cells were visualized and counted under an inverted microscope.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry with

Annexin V-FITC/APC and Propidium Iodide (PI)/7-AAD staining.

Briefly, 5×105 cells were harvested following digestion

with EDTA-free trypsin and resuspended in 500 µl binding buffer.

The cell suspension was gently pipetted to ensure a single-cell

distribution. Subsequently, 5 µl Annexin V-FITC (or APC) and 5 µl

PI (or 7-AAD) were added to the suspension. Samples were incubated

in the dark at room temperature for 5–10 min and analyzed within 1

h using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCelesta™; BD Biosciences) and

FlowJo 10.6.2 software (FlowJo, LLC). The apoptosis rate was

calculated by summing the proportions of early apoptotic cells (Q3

quadrant) and late apoptotic cells (Q2 quadrant).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation of three independent experiments. All statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version

10.1.2; Dotmatics). For comparisons between two groups, independent

sample t-tests were employed. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was applied for comparisons among multiple groups, as appropriate.

When ANOVA results were significant, Tukey's HSD post hoc test was

used to identify pairwise differences. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference

Results

Proteomic analysis after THBS1

overexpression

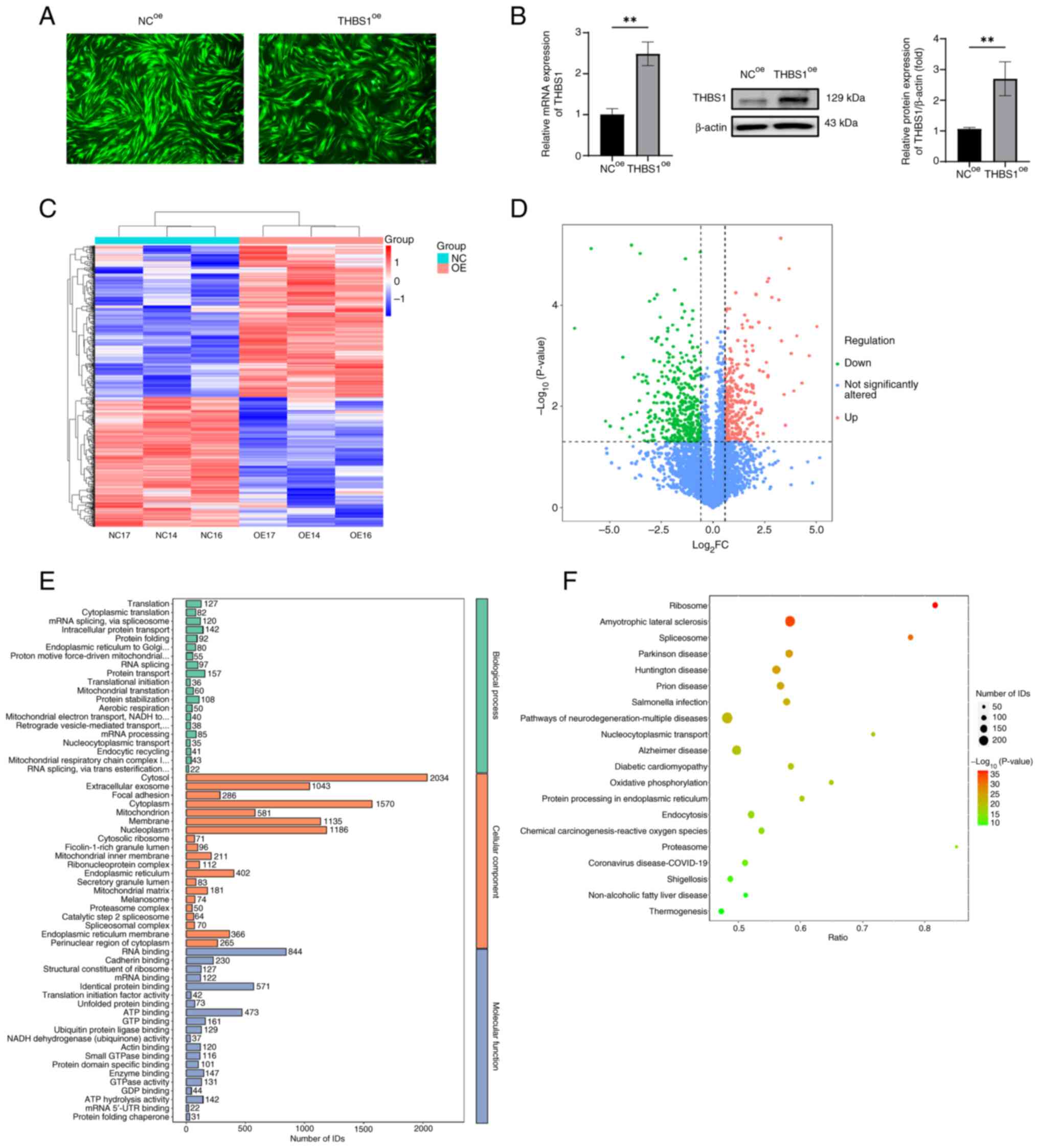

Fluorescence microscopy demonstrated successful

lentiviral infection of MGC cells, with strong fluorescence signals

observed in both negative control overexpression (NCoe)

and THBS1 overexpression (THBS1oe) groups at 72 h

post-infection (Fig. 2A).

Quantitative analysis further assessed the overexpression,

demonstrating significantly elevated mRNA and protein levels of

THBS1 in the THBS1oe group compared with in the

NCoe group (Fig. 2B;

P<0.05). Subsequent proteomic analysis identified a total of

35,894 peptides and 4,949 proteins. Quality control procedures,

including hierarchical clustering of DEPs, confirmed high data

reproducibility. The clustering dendrogram displayed in the heatmap

(Fig. 2C) revealed consistent

expression profiles among biological replicates. A volcano plot

visually represented 685 DEPs between the THBS1oe and

NCoe groups, of which 369 were upregulated and 316 were

downregulated (Fig. 2D). Based on

the criteria |log2(FC)|>1.5 and P<0.05, ALG1 was

identified as the most significantly altered protein. GO enrichment

analysis was performed across three domains: Biological process

(BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF). In the

BP category, DEPs were significantly enriched in processes such as

translation, cytoplasmic translation, mRNA splicing via the

spliceosome, intracellular protein transport and protein folding.

In the CC category, DEPs were predominantly localized to the

cytosol, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and cellular

membranes. For MF, enrichment was observed in RNA binding,

identical protein binding, ATP binding and cadherin binding

(Fig. 2E). KEGG pathway analysis

revealed that DEPs were enriched in several disease-related

pathways, including Ribosome, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis,

Spliceosome and Parkinson's disease (Fig. 2F). Additionally, DEPs were involved

in core signaling pathways associated with cell cycle regulation,

DNA replication and transcriptional dysregulation in cancer. These

results indicate that THBS1 overexpression exerts widespread

effects on the cellular proteome, providing new insights into its

downstream molecular mechanisms.

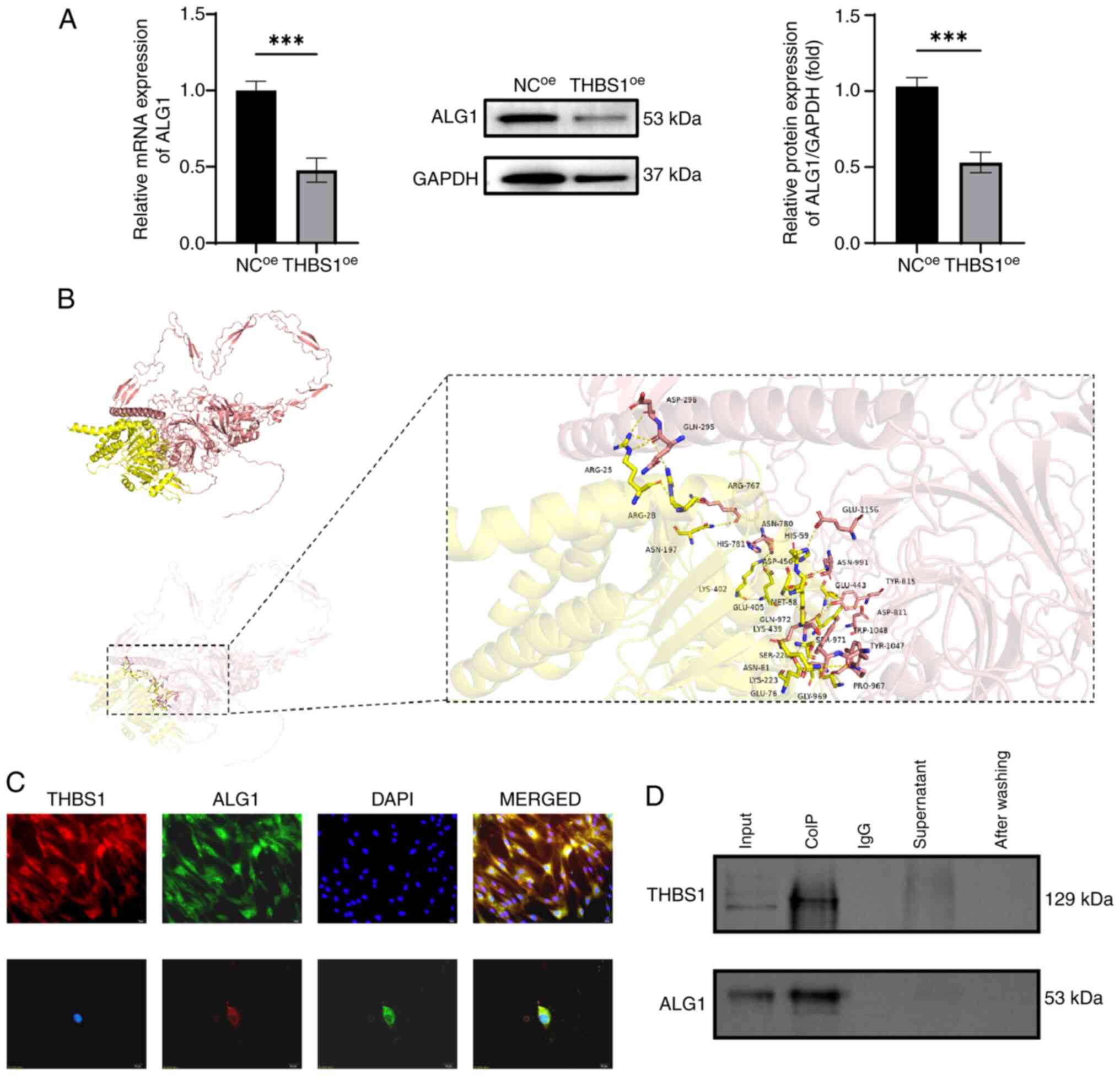

Interaction between THBS1 and

ALG1

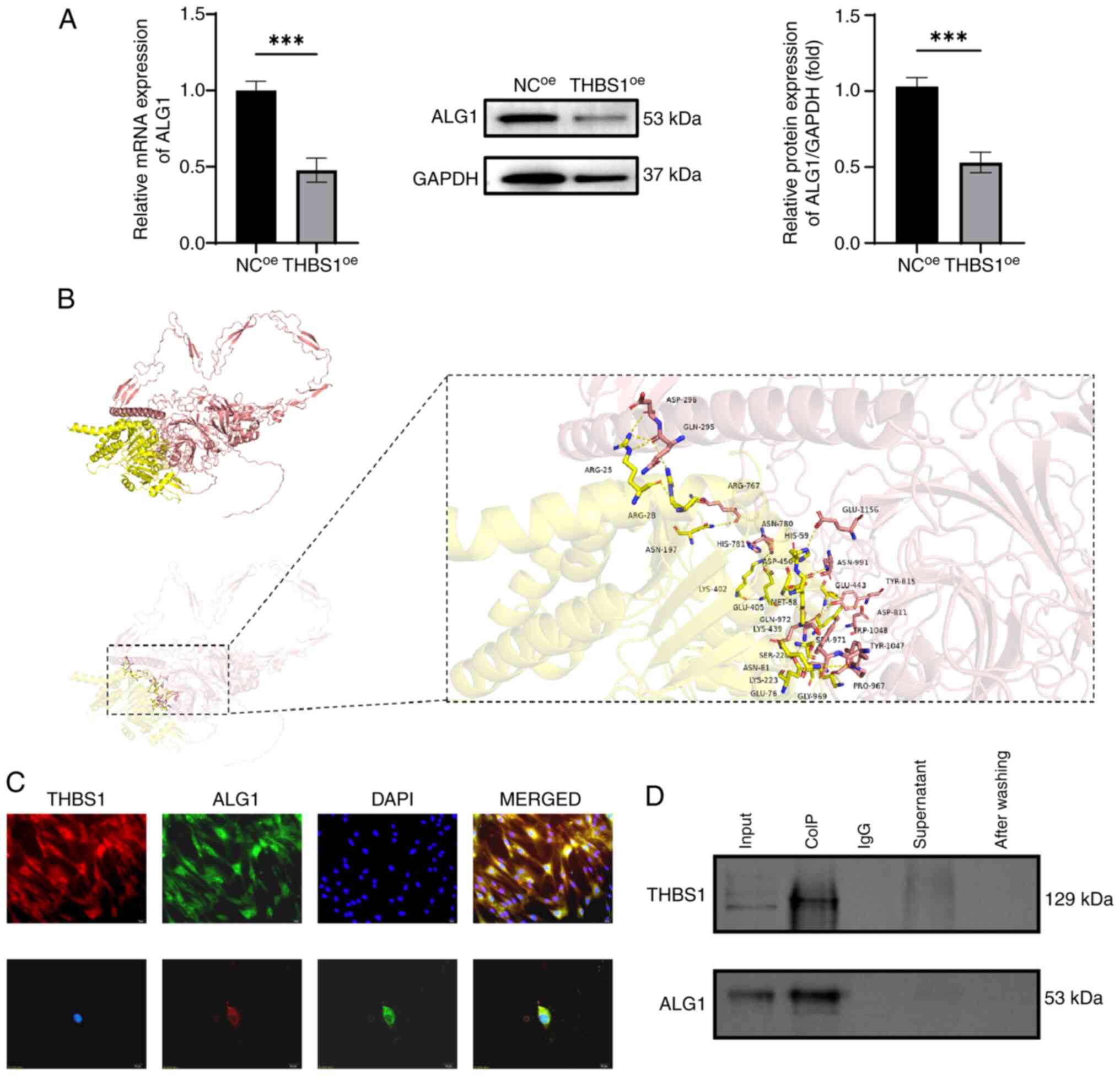

Proteomic analysis identified ALG1 as the most

significantly altered protein following THBS1 overexpression.

Quantitative expression analysis revealed that both mRNA and

protein levels of ALG1 were significantly reduced in the

THBS1oe group compared with in the NCoe

group, consistent with the proteomic sequencing data (Fig. 3A). To further assess the potential

interaction between THBS1 and ALG1, a protein-protein docking

analysis was performed. The docking model demonstrated that THBS1

(depicted in pink) forms a stable complex with ALG1 (depicted in

yellow), with hydrogen bonds formed between amino acid residues

ASN-991 of THBS1 and MET-58 of ALG1 (indicated by yellow dashed

lines), and a calculated binding energy of −4.9 kcal/mol (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest a strong

and stable interaction between the two proteins with high binding

affinity. To visualize their subcellular distribution,

immunofluorescence co-localization experiments were performed.

THBS1 (red fluorescence) and ALG1 (green fluorescence) were

demonstrated to co-localize predominantly in the cytoplasm, whereas

DAPI staining (blue fluorescence) clearly delineated the nuclear

region (Fig. 3C). Finally, Co-IP

assays revealed the direct physical interaction between THBS1 and

ALG1. This interaction was demonstrated to be specific and

unaffected by the presence of other proteins, further supporting

the docking results (Fig. 3D).

| Figure 3.Validation of the interaction between

THBS1 and ALG1. (A) Validation of ALG1 downregulation following

THBS1 overexpression via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and

western blot analyses. (B) Protein docking model of THBS1 and ALG1

showing their interface residues (THBS1, pink; ALG1, yellow; and

hydrogen bonds, yellow dashed lines). (C) Immunofluorescence

co-localization analysis of THBS1 and ALG1 (magnification, ×400;

scale bar, 20 µm). (D) Immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrating

the specific interaction between THBS1 and ALG1. ***P<0.001.

ALG1, chitobiosyldiphosphodolichol β-mannosyltransferase 1; THBS1,

thrombospondin 1; NC, negative control; oe, overexpression; CoIP,

co-immunoprecipitation. |

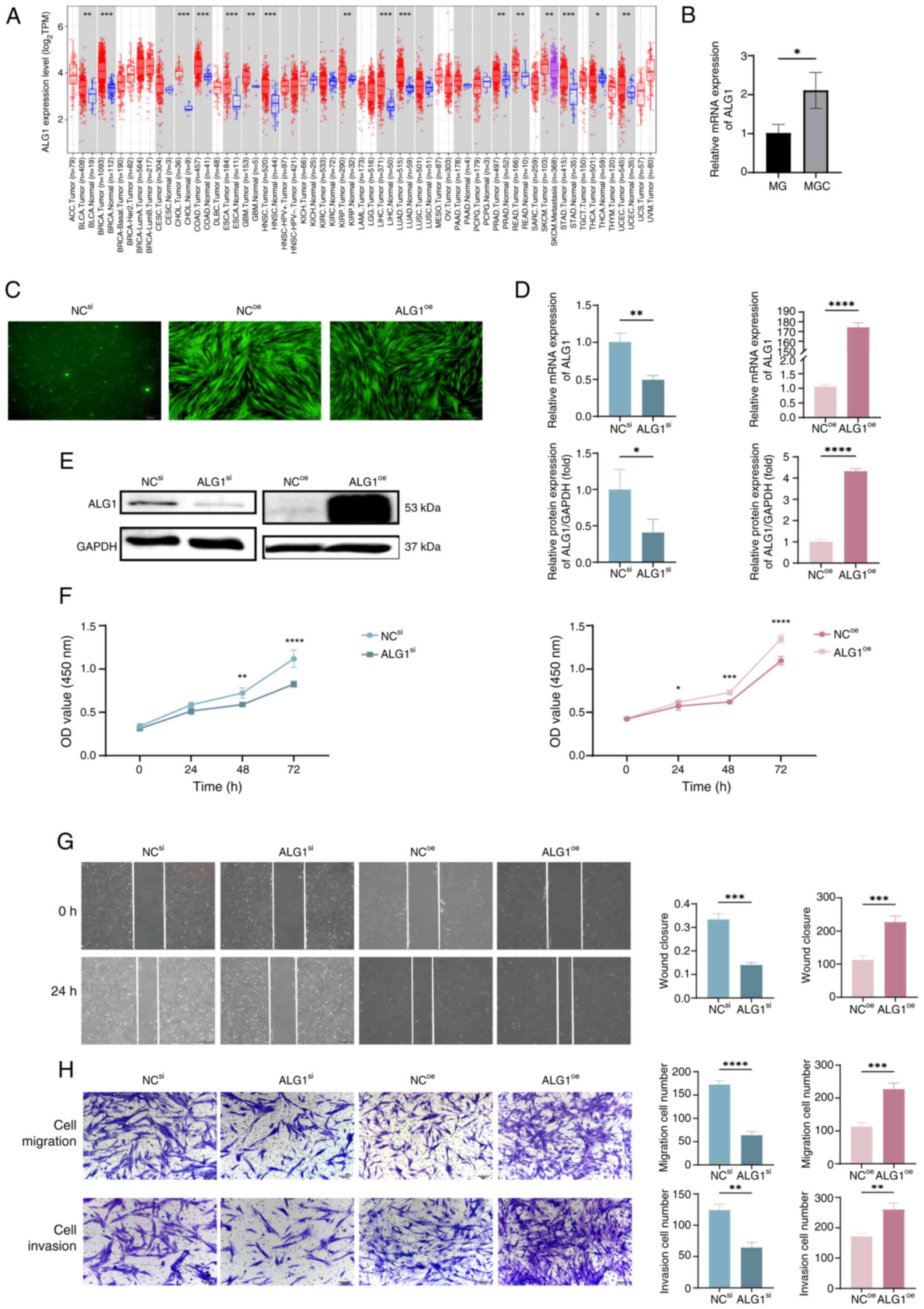

Expression profile of ALG1 and its

effects on MGC cell proliferation, migration and invasion

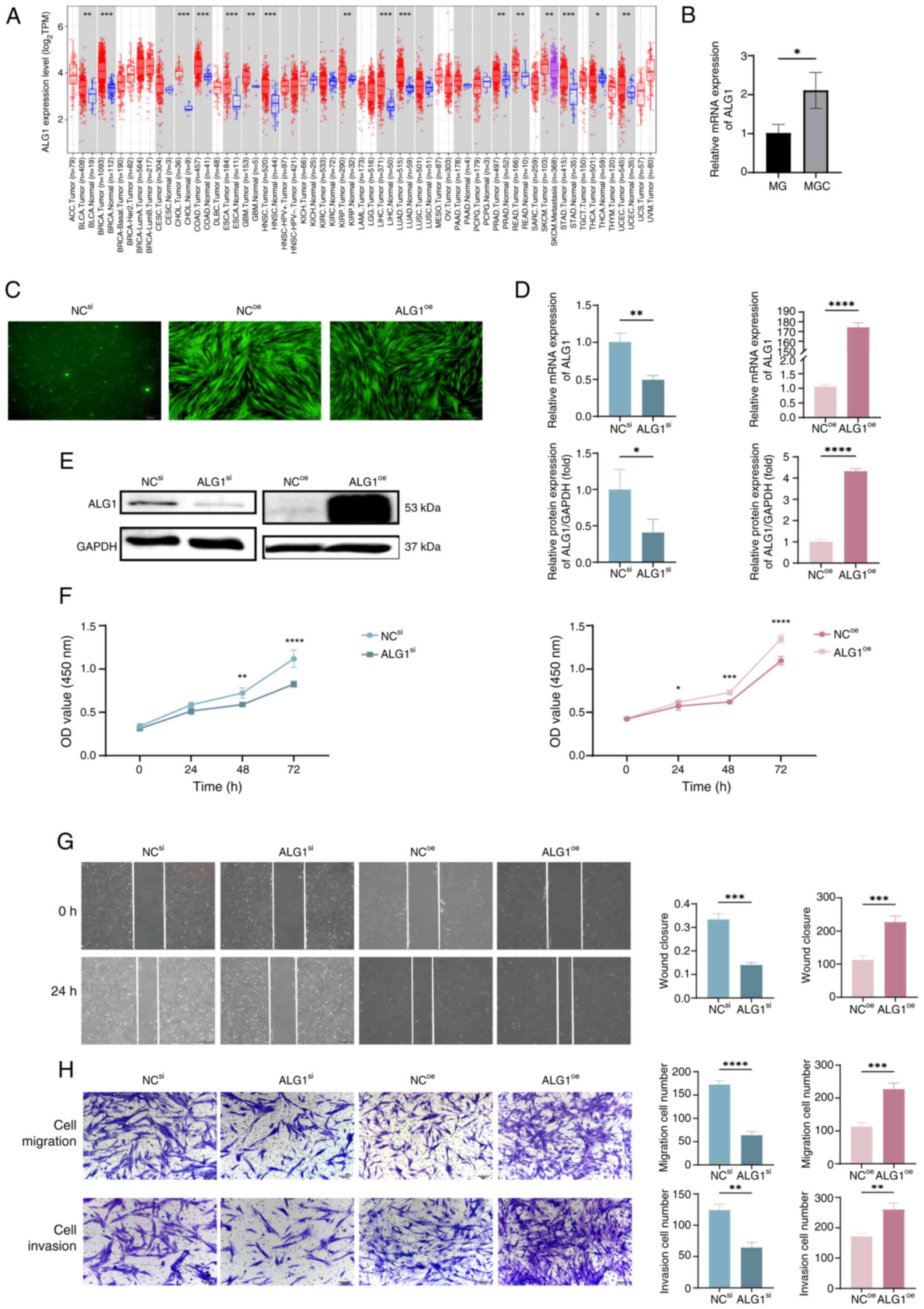

Using bioinformatics analysis via the TIMER 2.0

platform, the expression pattern of ALG1 across several tumor types

and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues were assessed in

the TCGA database (Fig. 4A). ALG1

expression was significantly elevated in multiple malignancies,

including bladder urothelial carcinoma, breast invasive carcinoma,

cholangiocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, esophageal carcinoma,

glioblastoma multiforme, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,

kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma, liver hepatocellular

carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, rectum

adenocarcinoma, stomach adenocarcinoma and uterine corpus

endometrial carcinoma, compared with in adjacent non-tumor tissues.

These findings suggest that ALG1 is frequently overexpressed in

diverse cancers, implying its potential oncogenic role and

relevance in tumor progression, thus providing a rationale for

further investigation into its functional significance in MGC

cells. To experimentally evaluate ALG1 expression in MGC cells,

RT-qPCR was performed to quantify ALG1 mRNA levels. The results

indicated that ALG1 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated

in MGC cells compared with in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 4B). Fluorescence microscopy further

demonstrated detectable ALG1-associated fluorescence signals across

the NCsi, NCoe and ALG1 overexpression

(ALG1oe) groups (Fig.

4C). Moreover, RT-qPCR and western blot analyses demonstrated

successful knockdown of ALG1 in the ALG1si group and

overexpression in the ALG1oe group, relative to their

respective controls (Fig. 4D and

E). Subsequently, the functional impact of ALG1 on MGC cell

behavior was assessed. CCK-8 assays revealed that ALG1 knockdown

significantly suppressed MGC cell proliferation, whereas ALG1

overexpression promoted cell proliferation compared with the NC

group (Fig. 4F). In addition,

scratch wound healing and Transwell invasion assays demonstrated

that ALG1 knockdown significantly reduced the migration and

invasion of MGC cells, whilst ALG1 overexpression significantly

enhanced these phenotypes compared with the NC group (Fig. 4G and H).

| Figure 4.Regulatory role of ALG1 in the

Biological Behaviors of MGC Cells. (A) Differential expression

analysis of ALG1 in tumors and adjacent normal tissues across

several cancer types and subtypes using the Tumor Immune Estimation

Resource 2.0. (B) Comparison of ALG1 mRNA expression levels in

primary MG and MGC cells. (C) Fluorescence microscopy images (×40;

scale bar, 200 µm) of MGC cells following ALG1 knockdown

(ALG1si) and overexpression (ALG1oe) in

NCsi, NCoe and ALG1oe groups. (D)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and (E) western blot

analyses of successful knockdown and overexpression of ALG1 in MGC

cells using siRNA and lentivirus, respectively. (F) Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay evaluating the effects of ALG1 regulation on MGC cell

proliferation. (G) Scratch wound-healing assay assessing the impact

of ALG1 modulation on cell migration (×40; scale bar, 200 µm). (H)

Transwell assay measuring the effects of ALG1 on MGC cell migration

and invasion (×100; scale bar, 100 µm). *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. ALG1, chitobiosyldiphosphodolichol

β-mannosyltransferase 1; MG, meibomian gland; MGC, MG carcinoma;

si, small interfering; oe, overexpression; NC, negative control;

TPM, transcripts per million; OD, optical density. |

Regulatory effects of ALG1 on

apoptosis and EMT

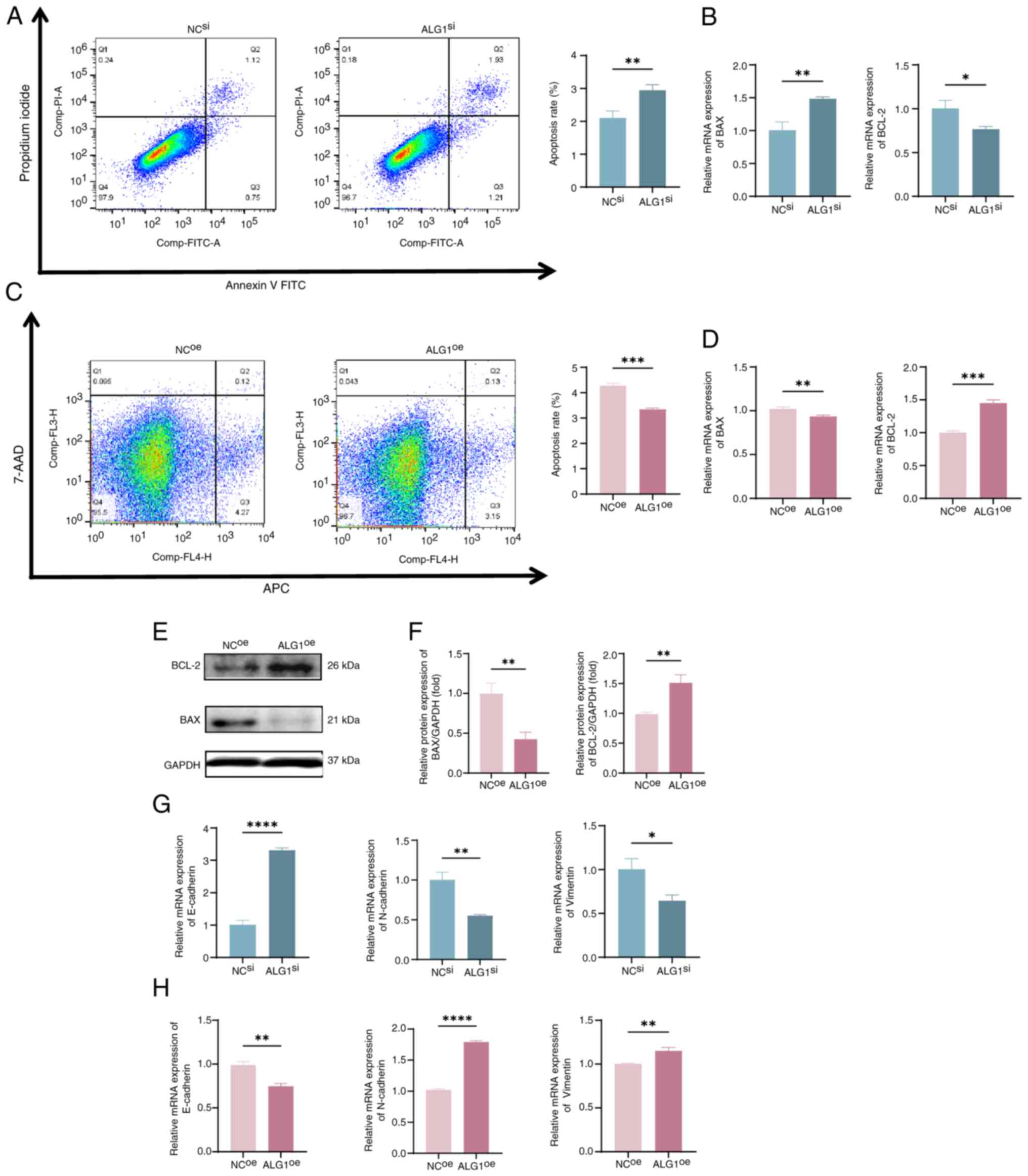

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that ALG1 knockdown

(ALG1si group) significantly increased the apoptosis

rate of MGC cells compared with that of the NC group (Fig. 5A). This finding was supported by the

significant upregulation of the mRNA expression of the

pro-apoptotic gene Bax and downregulated expression of the

anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 in the ALG1si group compared

with in the NCsi group (Fig.

5B). These findings suggest that ALG1 silencing induces

apoptosis in MGC cells, which may contribute to the suppression of

tumor growth and metastatic potential. Conversely, overexpression

of ALG1 (ALG1oe group) produced the opposite effects

(Fig. 5C and D). Meanwhile, the

downregulation of Bax and upregulation of Bcl-2 following ALG1

overexpression were further demonstrated using western blot

analysis (Fig. 5E and F).

Moreover, EMT is a key biological process involved

in tumor invasion and metastasis. EMT is characterized by the loss

of epithelial markers, such as E-cadherin, and the gain of

mesenchymal markers, including N-cadherin and vimentin, along with

cytoskeletal remodeling and acquisition of mesenchymal phenotypes

(20). To elucidate the role of

ALG1 in EMT regulation, the expression levels of canonical EMT

markers were assessed. In comparison with the NC group, knockdown

of ALG1 was associated with a significant decrease in vimentin and

N-cadherin expression, accompanied by a significant increase in

E-cadherin expression. This indicates a reversal of the EMT process

(Fig. 5G). Conversely,

overexpression of ALG1 (ALG1oe group) produced the

opposite effects, with significantly increased expression of

mesenchymal markers and suppressed expression of E-cadherin

compared with the NC group (Fig.

5H). Collectively, these results suggest that ALG1 promotes

EMT, and its downregulation facilitates a mesenchymal-to-epithelial

transition, thereby inhibiting the invasive and metastatic

potential of MGC cells.

Discussion

Globally, MGC is the third most common malignant

tumor of the eyelid. It predominantly affects elderly women and

most frequently involves the upper eyelid (21,22).

Early diagnosis and prompt surgical excision are essential to

prevent recurrence; however, due to its nonspecific clinical

presentation, MGC is frequently misdiagnosed or diagnosed at an

advanced stage, often leading to regional lymph node involvement

and distant metastasis, which severely compromise patient prognosis

(23,24). Although radiotherapy and

chemotherapy are commonly employed as adjunctive treatments for

advanced MGC, their clinical efficacy remains unsatisfactory.

Consequently, there is growing interest in molecular-targeted

therapies as a promising alternative for managing this malignancy.

Proteomic technologies offer a powerful approach to directly

analyze global and dynamic changes in the proteome, enabling the

discovery of novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets

(25,26). In this context, the identification

of effective molecular markers capable of inhibiting MGC

progression is urgently needed to improve therapeutic outcomes and

patient survival.

Proteomics research in cancer primarily aims to

identify and characterize key proteins involved in malignant

transformation, discover biomarkers for early detection, predict

prognosis, assess therapeutic efficacy, uncover novel drug targets,

and ultimately advance the development of personalized medicine

(27,28). Despite substantial progress in the

field, proteomic investigations into the molecular mechanisms of

MGC remain relatively limited. Previous studies have reported that

miR-3907 is markedly upregulated in MGC and promotes cancer cell

proliferation and migration by negatively regulating THBS1

expression (7). Building upon these

findings, the present study employed 4D-label-free quantitative

proteomics to systematically analyze downstream DEPs following

THBS1 overexpression. GO enrichment analysis revealed that these

DEPs were predominantly involved in critical biological processes

such as translation, intracellular protein transport and protein

folding. Furthermore, KEGG pathway analysis indicated significant

enrichment in ribosome metabolism, as well as pathways associated

with cell cycle regulation, DNA replication and transcriptional

dysregulation in cancer. These results offer valuable insights into

the functional landscape of THBS1-regulated proteins and provide a

robust foundation for future research aimed at the identification

of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Follow-up validation

experiments confirmed that THBS1 overexpression markedly

downregulated the mRNA and protein expression levels of ALG1.

Functional studies further demonstrated a direct interaction

between THBS1 and ALG1 and revealed that ALG1 exerts a potential

oncogenic role in MGC progression. Collectively, these findings

deliver important theoretical evidence for elucidating the

molecular mechanisms underlying MGC and contribute to the

identification of promising therapeutic targets for improving

clinical management of this malignancy.

ALG1, which encodes the enzyme responsible for

catalyzing the first mannosylation step in the biosynthesis of

lipid-linked oligosaccharides, serves a key role in

glycometabolism. Notably, metabolic differences between normal and

tumor cells are profound, with a well-documented shift from

oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg

effect) recognized as a hallmark of cancer development (29). This metabolic reprogramming enhances

tumor cell proliferation, invasion and chemoresistance, and is

closely associated with the tumor microenvironment (TME) and immune

evasion. Previous studies have revealed that ALG1 is markedly

associated with immune cell infiltration, TME modulation and

therapeutic responsiveness in gastric adenocarcinoma, highlighting

its potential as a target in cancer treatment (30,31).

Furthermore, ALG1 has been implicated in the early stages of

N-glycosylation, a process intricately linked to the progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma (31). In

colorectal cancer, prognostic models based on glycolysis-related

genes, including ALG1, have demonstrated positive associations with

poor patient outcomes, EMT activation and immune modulation within

the TME (32). However, the

functional role and clinical significance of ALG1 in MGC have not

yet been elucidated.

In the present study, through analysis of publicly

available databases, the results demonstrated that ALG1 expression

is elevated in multiple tumor types, underscoring its potential as

a broadly applicable therapeutic target. It was further revealed

that ALG1 is markedly upregulated in MGC cells, thereby expanding

the spectrum of cancers characterized by high ALG1 expression.

Moreover, through a combination of protein-protein docking,

immunofluorescence co-localization, and Co-IP assays, the present

study identified a direct physical interaction between THBS1 and

ALG1, for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. Functional

studies revealed that ALG1 knockdown significantly inhibited MGC

cell proliferation, migration and invasion, whilst simultaneously

promoting apoptosis. By contrast, ALG1 overexpression exerted the

opposite effects. These findings suggest that ALG1 functions as a

putative oncogene in MGC and raise the possibility that

small-molecule inhibitors targeting ALG1 may serve as a novel

therapeutic strategy, particularly in cancers with elevated ALG1

expression.

EMT is a fundamental biological process that

facilitates cancer cell migration and invasion, and it is

intimately associated with cellular stemness in both tissue

homeostasis and cancer progression (33,34).

This process is orchestrated by a set of core EMT-associated

transcription factors, which suppress the expression of epithelial

markers (such as E-cadherin) and simultaneously induce mesenchymal

markers, including vimentin and N-cadherin (35). The present study demonstrated that

ALG1 modulated EMT marker expression in MGC cells. Specifically,

ALG1 knockdown resulted in increased E-cadherin expression,

indicating enhanced epithelial characteristics and cell-cell

adhesion. Conversely, overexpression of ALG1 suppressed E-cadherin

expression, consistent with a shift toward a mesenchymal phenotype.

In parallel, the expression levels of vimentin and N-cadherin were

positively associated with ALG1 expression, further reinforcing the

role of ALG1 in promoting EMT. These findings support the

hypothesis that ALG1 contributes to MGC cell metastasis and

invasiveness by regulating EMT-associated genes. However, the

present study only explored the role of ALG1 in MGC cells via cell

function experiments and detection of EMT-related markers.

Subsequent research should focus on the signaling pathways closely

associated with EMT in KEGG. By detecting the phosphorylation

levels of key proteins and analyzing upstream-downstream regulatory

relationships, further studies should aim to thoroughly dissect the

regulatory mechanisms of these pathways and comprehensively uncover

the exact molecular mechanisms by which ALG1 regulates EMT. Such

insights will provide a foundation for precision medicine

approaches and may lead to the development of personalized

therapeutic strategies targeting EMT and metastatic progression.

Moreover, to address the limitation of focusing solely on ALG1,

future research should utilize proteomics data to study other

proteins among the identified differentially expressed proteins.

Bioinformatics and functional analyses should employ to explore

their roles in cell phenotypes and analyze their expression in

larger patient cohorts to uncover new mechanisms, biomarkers and

therapeutic approaches.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

THBS1 overexpression suppresses MGC progression via the

downregulation of ALG1, and revealed a direct molecular interaction

between THBS1 and ALG1. Functionally, silencing ALG1 significantly

inhibited MGC cell proliferation, migration and invasion, whilst

promoting apoptosis. Mechanistically, these effects were associated

to ALG1-mediated modulation of EMT, characterized by downregulation

of E-cadherin and upregulation of mesenchymal markers such as

N-cadherin and vimentin. Collectively, these findings highlight

ALG1 as a critical oncogenic mediator in MGC and suggest its

positioning within the miR-3907/THBS1/ALG1 regulatory axis. This

axis represents a promising theranostic biomarker for the

diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of MGC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Open Project of Tianjin

Key Laboratory of Retinal Functions and Diseases (grant no.

2021tjswmm001), Tianjin Health Science and Technology Project

(grant no. TJWJ2022MS012) and Tianjin Key Medical Discipline

(Specialty) Construction Project (grant no. TJYXZDXK-037A).

Availability of data and materials

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in

the present study may be found in the ProteomeXchange Consortium

via the PRIDE (36) partner

repository under accession number PXD059655 or at the following

URL: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride.

Authors' contributions

WW, HTW, GJW, XL, LMZ, FT and TTL conceived and

designed the study. WW, HTW, GJW, XL, LMZ, FT, and TTL acquired,

analyzed and interpreted the data. WW drafted the manuscript. WW,

HTW, GJW, XL, LMZ, FT and TTL revised the manuscript. WW, HTW and

GJW performed the statistical analyses. LMZ and TTL obtained

funding for the present study. WW and HW confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee

of Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital [approval no.

2020KY(L)-20]. Informed written consent was obtained from all

subjects involved in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Seago M, Hosking AM, Greenway HT and

Kelley B: Extraocular sebaceous carcinoma treated with Mohs

micrographic surgery-A 24-year retrospective review of tumor

characteristics and treatment outcomes. Dermatol Surg.

47:1195–1199. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sa HS, Rubin ML, Xu S, Ning J, Tetzlaff M,

Sagiv O, Kandl TJ and Esmaeli B: Prognostic factors for local

recurrence, metastasis and survival for sebaceous carcinoma of the

eyelid: Observations in 100 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 103:980–984.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tripathi R, Chen Z, Li L and Bordeaux JS:

Incidence and survival of sebaceous carcinoma in the United States.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 75:1210–1215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Muqit MM, Foot B, Walters SJ, Mudhar HS,

Roberts F and Rennie IG: Observational prospective cohort study of

patients with newly-diagnosed ocular sebaceous carcinoma. Br J

Ophthalmol. 97:47–51. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu M, Chen Q, Luo Y, Chai P, He X, Huang

H, Tan J, Ye J and Zhou C: Recurrence in eyelid sebaceous

carcinoma: A multicentric study of 418 patients. Invest Ophthalmol

Vis Sci. 65:42024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Timtim E, Barahimi B, Mawn LA and Sobel

RK: Sebaceous carcinoma masquerading as ocular mucous membrane

pemphigoid. Orbit. 43:531–534. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lu L, Zhang Y, Ge S, Wen H, Tang X, Zeng

JC, Wang L, Zeng Z, Rada G, Ávila C, et al: Evidence mapping and

overview of systematic reviews of the effects of acupuncture

therapies. BMJ Open. 12:e0568032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang C, Zhu L, Liu X, Jiang M, Tang Q, Xu

F, Lin T, Dong L and He Y: MicroRNA-3907 promotes the proliferation

and migration of sebaceous gland carcinoma of the eyelid by

targeting thrombospondin 1. Oncol Lett. 22:8332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Corbella E, Fara C, Covarelli F, Porreca

V, Palmisano B, Mignogna G, Corsi A, Riminucci M, Maras B and

Mancone C: THBS1 and THBS2 enhance the in vitro proliferation,

adhesion, migration and invasion of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

cells. Int J Mol Sci. 25:17822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kaur S, Bronson SM, Pal-Nath D, Miller TW,

Soto-Pantoja DR and Roberts DD: Functions of thrombospondin-1 in

the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 22:45702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cen J, Feng L, Ke H, Bao L, Li LZ, Tanaka

Y, Weng J and Su L: Exosomal thrombospondin-1 disrupts the

integrity of endothelial intercellular junctions to facilitate

breast cancer cell metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 11:19462019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Huang C, Zhou X, Li Z, Liu H, He Y, Ye G

and Huang K: Downregulation of thrombospondin-1 by DNA

hypermethylation is associated with tumor progression in laryngeal

squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 14:2489–2496. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Momin MY, Gaddam RR, Kravitz M, Gupta A

and Vikram A: The challenges and opportunities in the development

of microRNA therapeutics: A multidisciplinary viewpoint. Cells.

10:30972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Vergani-Junior CA, Moro RP, Pinto S,

De-Souza EA, Camara H, Braga DL, Tonon-da-Silva G, Knittel TL, Ruiz

GP, Ludwig RG, et al: An intricate network involving the argonaute

ALG-1 modulates organismal resistance to oxidative stress. Nat

Commun. 15:30702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Meier F, Brunner AD, Koch S, Koch H,

Lubeck M, Krause M, Goedecke N, Decker J, Kosinski T, Park MA, et

al: Online parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (PASEF) with

a novel trapped ion mobility mass spectrometer. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 17:2534–2545. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Haymond A, Davis JB and Espina V:

Proteomics for cancer drug design. Expert Rev Proteomics.

16:647–664. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang W, Wang HT, Liu X, Zhu LM and Lin TT:

Proteomic analysis of meibomian gland carcinoma cells after

overexpression of thrombospondin 1. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi J

Ophthalmol (Chinese). 61:376–383. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M,

Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT,

Pyysalo S, et al: The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein

association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any

sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D638–D646.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Brabletz T, Kalluri R, Nieto MA and

Weinberg RA: EMT in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:128–134. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jayaraj P, Ray D, Goel K, Singh A, Kant N

and Sen S: Molecular landscape of eyelid sebaceous gland carcinoma:

A comprehensive review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 72:1393–1403. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cicinelli MV and Kaliki S: Ocular

sebaceous gland carcinoma: an update of the literature. Int

Ophthalmol. 39:1187–1197. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vempuluru VS, Tanna V, Luthra A and Kaliki

S: Eyelid/periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma in 500 eyes:

Analysis based on 8th edition American joint cancer committee

classification. Am J Ophthalmol. 269:49–59. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dini F, Susini P, Nisi G, Cuomo R,

Grimaldi L, Massi D, Innocenti A, Doni L, Mazzini C, Santoro N and

De Giorgi V: Periocular sebaceous carcinoma: Updates in the

diagnosis, treatment, staging, and management. Int J Dermatol.

63:726–736. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lee YT, Tan YJ and Oon CE: Molecular

targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. Eur J

Pharmacol. 834:188–196. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin F, Li Z, Hua Y and Lim YP: Proteomic

profiling predicts drug response to novel targeted anticancer

therapeutics. Expert Rev Proteomics. 13:411–420. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tan HT, Lee YH and Chung MC: Cancer

proteomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 31:583–605. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Haga Y, Minegishi Y and Ueda K: Frontiers

in mass spectrometry-based clinical proteomics for cancer diagnosis

and treatment. Cancer Sci. 114:1783–1791. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Abbaszadeh Z, Cesmeli S and Biray Avci C:

Crucial players in glycolysis: Cancer progress. Gene.

726:1441582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liao Z and Xie Z: Construction of a

disulfidptosis-related glycolysis gene risk model to predict the

prognosis and immune infiltration analysis of gastric

adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 26:2309–2322. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cao X, Shao Y, Meng P, Cao Z, Yan G, Yao

J, Zhou X, Liu C, Zhang L, Shu H and Lu H: Nascent proteome and

glycoproteome reveal the inhibition role of ALG1 in hepatocellular

carcinoma cell migration. Phenomics. 2:230–241. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu G, Wu X and Chen J: Identification and

validation of a glycolysis-related gene signature for depicting

clinical characteristics and its relationship with tumor immunity

in patients with colon cancer. Aging. 14:8700–8718. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Verstappe J and Berx G: A role for partial

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in enabling stemness in

homeostasis and cancer. Semin Cancer Boil. 90:15–28. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ramesh V, Brabletz T and Ceppi P:

Targeting EMT in cancer with Repurposed Metabolic Inhibitors.

Trends in cancer. 6:942–950. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fontana R, Mestre-Farrera A and Yang J:

Update on epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer progression.

Annu Rev Pathol. 19:133–156. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Perez-Riverol Y, Bai J, Bandla C,

García-Seisdedos D, Hewapathirana S, Kamatchinathan S, Kundu DJ,

Prakash A, Frericks-Zipper A, Eisenacher M, et al: The PRIDE

database resources in 2022: A hub for mass spectrometry-based

proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:D543–D552. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|