Introduction

Recent advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) targeting the programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway have

significantly improved treatment outcomes in non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC), with improvements in overall survival (OS) and

progression-free survival (PFS) (1–6). ICIs

can yield favorable clinical outcomes even in patients with NSCLC

and bone metastases (BoMs) (7–11), a

condition traditionally associated with poor prognosis (12–14).

However, not all patients respond favorably, highlighting a need

for continued research to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of

ICIs.

In our clinical experience, we have observed several

cases of NSCLC with BoMs where bone-targeted radiotherapy (RT)

combined with ICIs achieved lung tumor shrinkage and prolonged

survival. This phenomenon, where tumors shrink at sites distant

from the irradiated area, is known as the abscopal effect (15). RT promotes an antitumor immune

response by inducing antigen release and immunogenic cell death,

enhancing maturation and antigen presentation by antigen-presenting

cells, mobilizing T cells, and sensitizing tumor cells to

immune-mediated cell death, which may underlie the abscopal effect

(15,16). Although the abscopal effect is rare

and its mechanisms are unclear (17), ICIs may enhance immune responses

induced by RT, suggesting a potential synergistic effect that could

improve ICI efficacy (16–20). Notably, increased infiltration and

enhanced cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells within the

tumor immune microenvironment have been reported to play a crucial

role in augmenting the abscopal effect (21,22).

However, the relationship between RT for BoMs and the abscopal

effect in ICI-treated NSCLC has not been elucidated. The study

aimed to determine whether RT for BoMs induces an abscopal effect

in ICI-treated NSCLC and the clinical benefits of this effect.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient

population

This retrospective study included patients with

advanced NSCLC diagnosed with BoMs before receiving ICI treatment

between January 2016 and March 2024 at Kanazawa University

Hospital. The ICIs used in this study were PD-1 inhibitors

(nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and PD-L1 inhibitors (atezolizumab

and durvalumab). For patients with negative driver-gene mutations

and a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) >50%, first-line

treatment was PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy or combination

therapy with platinum-based agents. In other cases, ICIs were

employed as second-line or later therapy following failure of

conventional chemotherapy or molecular-targeted treatments. To

accurately evaluate the effects of RT on BoMs, patients who had

received RT for lung lesions or brain metastases, as well as those

who had been treated with bone-modifying agents for BoMs, were

excluded. Additionally, patients with a performance status of 3 or

higher and those who received combination therapy with PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4

inhibitors were excluded. This study was approved by the Medical

Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University (approval number: 3339-1)

and was conducted in accordance with relevant laws and

institutional guidelines as well as with the tenets enunciated in

the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was waived

due to the retrospective design. Instead, consent was obtained via

an opt-out method approved by the ethics committee, with study

information provided publicly to allow patients to decline

participation.

Data analysis

The medical records used in this study were

collected from the Kanazawa University Hospital database. Data

included patient characteristics such as age, sex, histological

type, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, PD-L1

TPS, number of BoM, visceral metastasis, and ICI and RT history,

including timing and site of BoM. All data were reviewed

independently by at least two investigators to ensure accuracy and

consistency. Patients who received RT to treat multiple bone

lesions were excluded to evaluate the therapeutic effect of

radiation on a single metastatic bone lesion. Participants were

divided into two groups: irradiated (RT-BoM) and non-irradiated

BoMs (non-RT-BoM), and clinical outcomes were evaluated by

assessing responses in lung lesions, OS, PFS, and the incidence of

immune-related adverse events (irAEs, grade ≥3 based on Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0). To evaluate

local control of BoMs with and without irradiation, spinal

paralysis and pathological fractures during ICI treatment were

assessed. Lung lesion response was assessed based on Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1, with size changes

measured via computed tomography between ICI initiation and the

final follow-up. This radiological evaluation was performed by at

least two physicians, including radiologists, to ensure accuracy

and reliability.

Statistical analysis

OS and PFS from ICI treatment initiation were

assessed using the Kaplan-Meier curve analysis. All clinical data

were used as variables, with Fisher's exact and log-rank tests to

compare between the two groups. In addition, logistic regression

and the COX proportional hazards models were used in multivariate

analysis to assess correlations between clinical data and outcomes

and identify independent predictive factors. Cases with missing

data for key variables or primary outcomes were excluded from the

analysis. However, PD-L1 TPS was not assessed in some patients;

these cases were included in the analysis as a separate unknown

category. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant, and EZR

software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University,

Saitama, Japan) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

In total, 108 patients with NSCLC having BoMs were

enrolled, and their clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table I. This study included 80 men

and 28 women, with a mean age of 66.6±8.6 years. The median

follow-up time from initiation of ICI treatment was 21.8 (2–101)

months. The RT-BoM and non-RT-BoM groups included 33 and 75

patients, respectively, with no significant difference observed for

clinical characteristics (Table I).

In the RT-BoM group, the dose/fraction was 2-8 Gy/1-15 fx (total

dose 8-39 Gy) and the most frequently irradiated site was the

spine. Additionally, 66.7% of cases received radiation before

initiating ICI (Table I).

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of

participants. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of

participants.

| Clinical

characteristic | RT-BoM, n

(n=33) | Non-RT-BoM, n

(n=75) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

| 0.63 |

|

Male | 26 | 54 |

|

|

Female | 7 | 21 |

|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.52 |

|

≥70 | 21 | 42 |

|

|

<70 | 12 | 33 |

|

| Histology |

|

| 0.81 |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 25 | 59 |

|

|

Non-adenocarcinoma | 8 | 16 |

|

| PD-L1 TPS, % |

|

| 0.98 |

|

<50 | 15 | 34 |

|

|

≥50 | 7 | 17 |

|

|

Unknown | 11 | 24 |

|

| PS |

|

| 0.51 |

| ≤1 | 28 | 68 |

|

| 2 | 5 | 7 |

|

| ICIs |

|

| 0.98 |

| PD-1

inhibitor | 22 | 51 |

|

| PD-L1

inhibitor | 11 | 24 |

|

| Treatment line of

ICIs |

|

| 0.19 |

|

1st | 18 | 51 |

|

|

≥2nd | 15 | 24 |

|

| Number of BoM |

|

| 0.81 |

|

Monostotic | 9 | 18 |

|

|

Multiple | 24 | 57 |

|

| Visceral

metastasis |

|

| 0.62 |

|

Yes | 27 | 57 |

|

| No | 6 | 18 |

|

| Radiation to BoM

timing |

|

|

|

| Pre-ICI

treatment | 22 |

|

|

|

Post-ICI treatment | 11 |

|

|

| Site |

|

|

|

|

Spine | 20 |

|

|

|

Pelvis | 11 |

|

|

| Long

bones of the extremities | 2 |

|

|

Clinical outcomes between RT-BoM vs.

non-RT-BoM groups

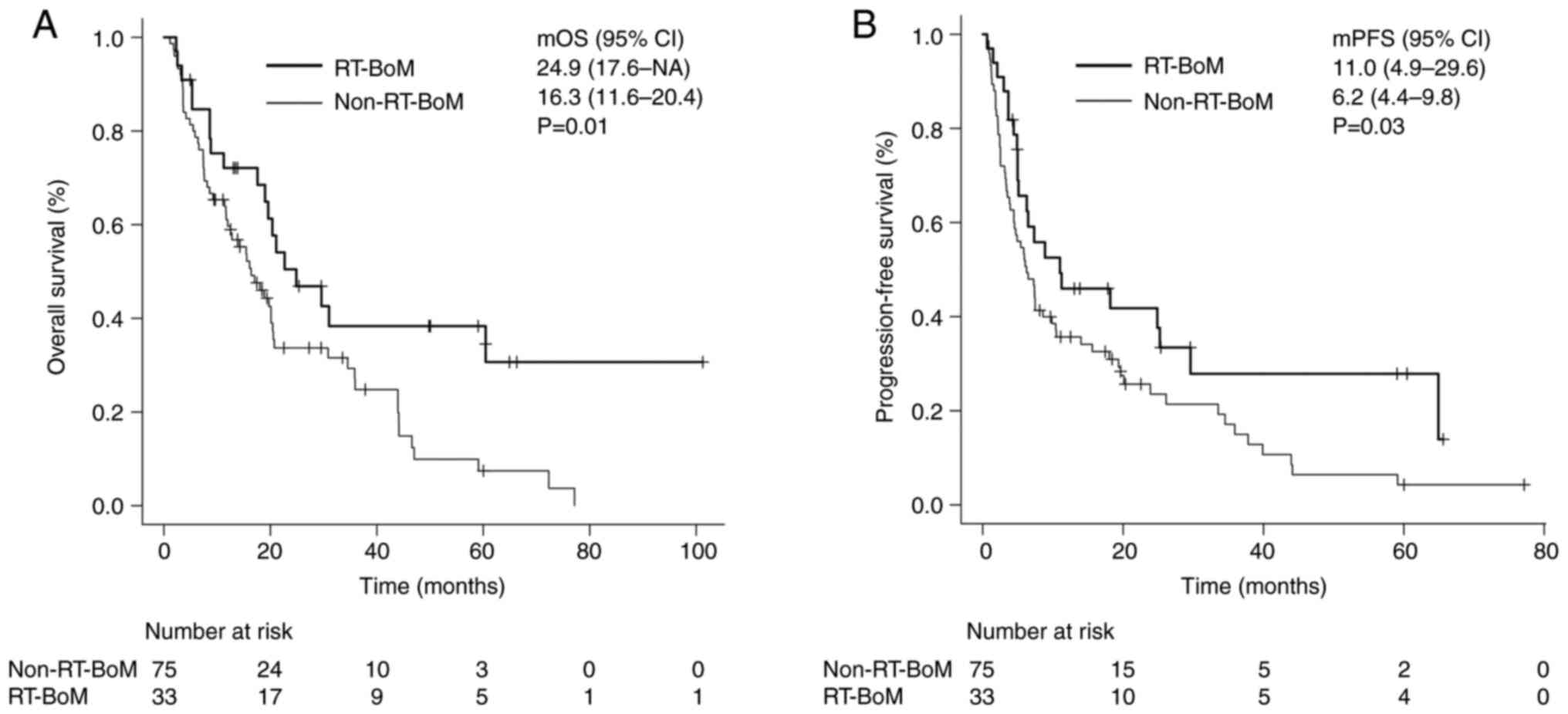

The overall response rate of lung lesions in the

RT-BoM group was 42.4%, which was significantly better than that in

the non-RT-BoM group (21.3%, P=0.03). The median OS and PFS in the

RT-BoM group were 24.9 (17.6-NA) and 11.0 (4.9-29.6) months,

respectively, significantly longer than those in the non-RT-BoM

group [16.3 (11.6-20.4) months, P=0.01; 6.2 (4.4-9.8) months,

P=0.03] (Fig. 1A and B). The

incidence of irAEs in the RT-BoM group was 21.2%, similar to that

in the non-RT-BoM group (21.3%), with no significant difference

(P=0.99). No skeletal-related events (SREs) were observed after

radiation in the RT-BoM group; however, two cases of pathological

fracture were observed in the non-RT-BoM group during ICI treatment

(both cases required surgery for vertebral pathological fractures

and paralysis).

Furthermore, subgroup analyses were performed for

the RT-BoM group. The group that received radiation before ICI

initiation (n=22) had a significantly better lung lesion response

rate than the group that received radiation after ICI initiation

(n=11) (54.5 vs. 9.1%, P=0.02). Although no significant difference

was observed in OS [24.9 (18.9-NA) vs. 21.0 (3.3-NA)months, P=0.58]

or PFS [18.2 (5.1-NA) vs. 6.4 (1.4-64.9) months, P=0.45] between

the two groups, a trend toward prolonged OS and PFS was noted in

the group that received radiation before initiating ICIs.

Irradiation sites of BoM were analyzed in the spine (n=22) and

pelvis (n=11), where case numbers were high. No significant

differences were observed between lung lesion response (22.7 vs.

36.3%, P=0.61), OS [24.8 (8.6-NA) vs. 22.6 (8.6-NA) months,

P=0.44), and PFS [8.9 (3.6-NA) vs. 18.1 (4.8-NA) months, P=0.27].

However, due to the limited number of cases in each group, these

findings should be interpreted with caution.

Predictive factors of clinical

outcomes

Univariate analysis identified predictors of lung

lesion response, revealing significant differences in sex [odds

ratio and 95% confidence interval: 0.23 (0.06-0.85), P=0.02] and

radiation for BoM (2.72 (1.12-6.58), P=0.01]. Multivariate analysis

incorporating these factors revealed that radiation for BoM was an

independent predictor [3.69 (1.20-11.40), P=0.02] (Table II). Univariate analysis for OS

predictors showed significant differences in visceral metastasis

[hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval: 2.72 (1.12-6.58),

P=0.02] and radiation for BoM [2.21 (1.22-3.97), P<0.01].

Multivariate analysis confirmed radiation for BoM as an independent

predictor of OS [2.22 (1.23-4.01), P<0.01] (Table III). For PFS, univariate analysis

showed significant differences in sex [1.68 (1.05-2.70), P=0.03],

treatment line of ICIs [1.73 (1.12-2.67), P=0.01], and radiation

for BoM [0.60 (0.36-0.97), P=0.04]. Multivariate analysis

incorporating these factors revealed that treatment line of ICIs

(1.84 [1.16-2.91], P=0.01) and radiation for BoM (0.56 [0.33-0.93],

P=0.02) were independent predictors of PFS (Table IV).

| Table II.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of lung lesion response. |

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of lung lesion response.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Comparison | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | Male vs.

female | 0.23

(0.06-0.85) | 0.02 | 0.48

(0.11-2.17) | 0.34 |

| Age | ≥70 vs. <70

years | 1.11

(0.46-2.58) | 0.82 |

|

|

| Histology | ADC vs.

non-ADC | 2.29

(0.88-5.94) | 0.09 |

|

|

| PD-L1 TPS | <50 vs. ≥50 | 1.25

(0.43-3.58) | 0.67 |

|

|

| PS | ≤1 vs. 2 | 2.03

(0.59-6.97) | 0.26 |

|

|

| ICIs | PD-1 inhibitor vs.

PD-L1 inhibitor | 0.42

(0.15-1.15) | 0.09 |

|

|

| Treatment line of

ICIs | 1st vs. ≥2nd | 0.43

(0.16-1.14) | 0.09 |

|

|

| Number of BoMs | Monostotic vs.

multiple | 1.65

(0.59-4.59) | 0.33 |

|

|

| Visceral

metastasis | Yes vs. no | 2.50

(0.77-8.02) | 0.12 |

|

|

| Radiation to

BoM | Yes vs. no | 2.72

(1.12-6.58) | 0.02 | 3.69

(1.20-11.40) | 0.02 |

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of overall survival. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of overall survival.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Comparison | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | Male vs.

female | 1.33

(0.82-2.17) | 0.23 |

|

|

| Age | ≥70 vs. <70

years | 1.42

(0.91-2.23) | 0.11 |

|

|

| Histology | ADC vs.

non-ADC | 1.01

(0.57-1.74) | 0.99 |

|

|

| PD-L1 TPS | <50 vs. ≥50 | 1.01

(0.53-1.86) | 0.98 |

|

|

| PS | ≤1 vs. 2 | 1.17

(0.61-2.29) | 0.63 |

|

|

| ICIs | PD-1 inhibitor vs.

PD-L1 inhibitor | 1.31

(0.81-2.11) | 0.28 |

|

|

| Treatment line of

ICIs | 1st vs. ≥2nd | 1.56

(0.99-2.46) | 0.06 |

|

|

| Number of BoMs | Monostotic vs.

multiple | 1.54

(0.90-2.61) | 0.11 |

|

|

| Visceral

metastasis | Yes vs. no | 2.72

(1.12-6.58) | 0.02 | 1.28

(0.80-2.04) | 0.31 |

| Radiation to

BoM | Yes vs. no | 2.21

(1.22-3.97) | <0.01 | 2.22

(1.23-4.01) | <0.01 |

| Table IV.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of progression-free survival. |

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of progression-free survival.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Comparison | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | Male vs.

female | 1.68

(1.05-2.70) | 0.03 | 1.51

(0.93-2.45) | 0.08 |

| Age | ≥70 vs. <70

years | 0.91

(0.59-1.41) | 0.69 |

|

|

| Histology | ADC vs.

non-ADC | 0.87

(0.52-1.47) | 0.62 |

|

|

| PD-L1 TPS | <50 vs. ≥50 | 0.85

(0.47-1.51) | 0.58 |

|

|

| PS | ≤1 vs. 2 | 1.45

(0.76-2.74) | 0.25 |

|

|

| ICIs | PD-1 inhibitor vs.

PD-L1 inhibitor | 1.31

(0.82-2.11) | 0.24 |

|

|

| Treatment line of

ICIs | 1st vs. ≥2nd | 1.73

(1.12-2.67) | 0.01 | 1.84

(1.16-2.91) | 0.01 |

| Number of BoMs | Monostotic vs.

multiple | 1.56

(0.93-2.61) | 0.08 |

|

|

| Visceral

metastasis | Yes vs. no | 1.43

(0.83-2.44) | 0.18 |

|

|

| Radiation to

BoM | Yes vs. no | 2.21

(1.22-3.97) | <0.01 | 2.22

(1.23-4.01) | <0.01 |

Discussion

Our study found that combined therapy with ICIs and

RT for BoM in advanced NSCLC may induce a favorable response in

lung lesions, considered an abscopal effect, and prolong prognosis,

in addition to providing good local control of BoMs.

Recent, large-scale studies on immunotherapy

combining ICIs and RT (23–32) have demonstrated that ICI treatment

enhances the immune response induced by RT, whereas RT enhances the

therapeutic effect of ICIs, confirming the existence of the

abscopal effect (18–20). Several systematic reviews and

meta-analyses have reported the occurrence of the abscopal effect

at distant sites, alongside prolonged OS and PFS with the

combination of ICIs and RT (20,33–36).

However, the abscopal effect remains rare, and its underlying

mechanism is not yet fully understood (17). Additionally, the relationship

between irradiation of BoMs and abscopal effect in NSCLC has rarely

been studied.

BoM is a poor prognostic factor in lung cancer

(12–14), and SREs, such as severe pain,

pathological fracture, and spinal cord compression, significantly

reduces daily activity and quality of life (37,38).

Therefore, early management of BoMs is crucial to prevent SREs.

Generally, RT and bone-modifying agents are commonly used in

combination to avoid interfering with systemic therapy (39–41).

This study focused on RT for BoMs and explored its potential to

improve ICI treatment efficacy. This favorable treatment effect,

which can be considered an abscopal effect, may improve clinical

outcomes for patients with NSCLC presenting BoMs, who typically

have a poor prognosis.

Our study found that irradiation of BoMs improved

the response rate of lung lesions and prolonged prognosis,

consistent with reports of the abscopal effect induced by RT of

lung or brain lesions (20,33–36),

as well as recent findings by Facilissimo et al (42) demonstrating similar benefits of RT

to BoMs in NSCLC patients receiving ICIs. In addition, no spinal

paralysis and pathological fractures occurred at the irradiated

site, and good local control was achieved. The incidence of grade 3

or higher irAEs, evaluated as a safety measure, was similar between

the RT-BoM and non-RT-BoM groups and consistent with previous

studies (36,43,44).

Subgroup analysis for investigating optimal RT strategy suggested

that RT prior to ICI treatment may result in better clinical

outcomes. Our results aligned with the suggestion that the optimal

timing for RT is either concomitant with or prior to ICI

administration (19,45). Based on these results, irradiated

BoMs before initiating ICIs may provide good local control,

pulmonary response, and prolonged prognosis, which can be

considered an abscopal effect, for advanced NSCLC. Our analysis

found no significant differences in clinical outcomes among

different irradiated BoM sites, suggesting that therapeutic

benefits may apply broadly. However, due to limited sample size and

site heterogeneity, further studies are needed to explore

site-specific effects and optimize treatment. While our results are

promising, the retrospective nature and heterogeneity in RT

protocols preclude definitive clinical recommendations. Further

prospective studies are needed to determine the optimal timing,

dosage, fractionation, and the role of irradiated sites to

establish standardized treatment protocols for clinical

practice.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a

retrospective analysis conducted at a single center without

randomization or a control group, which may have introduced

selection bias and limited generalizability. Second, the RT-BoM

group included a small number of patients (n=33), and RT regimens

varied in dose, fractionation, and treatment site, limiting the

evaluation of specific RT parameters. Third, although a possible

abscopal effect was suggested, its underlying mechanisms remain

unclear. Notably, we did not assess changes in the tumor immune

microenvironment or PD-L1 expression, which limits interpretation

of the immunological response. Further prospective, multi-center

studies, including randomized controlled trials with standardized

RT protocols and immune profiling, are necessary to validate and

expand upon these findings.

In conclusion, in ICI treatment of NSCLC with BoMs,

irradiation of BoMs was associated with improved lung lesion

response and prolonged prognosis, suggesting a possible abscopal

effect. In addition to local control of BoMs, systemic clinical

benefits were observed. However, due to the limitations of this

study, including its retrospective single-center design, small

sample size, and heterogeneity in RT protocols, these findings

should be interpreted with caution. Further prospective,

multi-center studies and mechanistic investigations are warranted

to confirm and better understand the observed effects and to

develop an optimized immunoradiotherapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions but may

be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YA, KH, MO, IM, SY and SD conceptualized the study.

YA, KH, SM, YT, MO, IM and SY developed the methodology. YA

performed the formal analysis. YA, KH, SM, YT, MO, IM and SY

conducted the investigation and data acquisition. KH, SY and SD

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. YA wrote the original

draft. KH, MO, IM, SY and SD performed review and editing. KH and

SD supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Kanazawa University (no. 3339-1; Kanazawa, Japan). The

requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the

retrospective design. Instead, consent was obtained via an opt-out

method approved by the ethics committee, with study information

provided publicly to allow patients to decline participation.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was not

required for the present study because all data were fully

anonymized and contained no identifiable patient information.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BoM

|

bone metastasis

|

|

ICI

|

immune checkpoint inhibitor

|

|

irAE

|

immune-related adverse event

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PD-1

|

programmed cell death protein 1

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed cell death ligand 1

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

RT

|

radiotherapy

|

|

SRE

|

skeletal-related event

|

|

TPS

|

tumor proportion score

|

References

|

1

|

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E,

Pérez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al:

Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated,

PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010):

A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 387:1540–1550. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L,

Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE,

Holgado E, et al: Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced

squamous-cell non-Small-Cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med.

373:123–135. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR,

Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al:

Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-Small-Cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:1627–1639. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG,

Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe

S, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive

non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 375:1823–1833. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park

K, Ciardiello F, Von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, Hida T, Kowalski DM, Dols

MC, et al: Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with

previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3,

open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet.

389:255–265. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho

BC, Turna HZ, Castro G, Srimuninnimit V, Laktionov KK, Bondarenko

I, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously

untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A randomised, Open-label,

controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 393:1819–1830. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Asano Y, Yamamoto N, Demura S, Hayashi K,

Takeuchi A, Kato S, Miwa S, Igarashi K, Higuchi T, Yonezawa H, et

al: The therapeutic effect and clinical outcome of immune

checkpoint inhibitors on bone metastasis in advanced non-small-cell

lung cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8716752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Asano Y, Yamamoto N, Demura S, Hayashi K,

Takeuchi A, Kato S, Miwa S, Igarashi K, Higuchi T, Taniguchi Y, et

al: Combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors and

denosumab improves clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer

with bone metastases. Lung Cancer. 193:1078582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Asano Y, Yamamoto N and Demura S, Takeuchi

A, Kato S, Miwa S, Okuda M, Matsumoto I, Yano S and Demura S: Serum

inflammatory dynamics as novel biomarkers for immune checkpoint

inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer with bone metastases.

Anticancer Res. 44:4493–4503. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Asano Y, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Hayashi K,

Takeuchi A, Kato S, Miwa S, Igarashi K, Higuchi T, Taniguchi Y, et

al: Novel predictors of immune checkpoint inhibitor response and

prognosis in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with bone

metastasis. Cancer Med. 12:12425–12437. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Asano Y, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Kato S,

Miwa S, Taniguchi Y, Okuda M, Matsumoto I, Yano S and Demura S:

Combining dynamics of serum inflammatory and nutritional indicators

as novel biomarkers in immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment of

non-small-cell lung cancer with bone metastases. Int

Immunopharmacol. 136:1122762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kawachi H, Tamiya M, Tamiya A, Ishii S,

Hirano K, Matsumoto H, Fukuda Y, Yokoyama T, Kominami R, Fujimoto

D, et al: Association between metastatic sites and first-line

pembrolizumab treatment outcome for advanced non-small cell lung

cancer with high PD-L1 expression: A retrospective multicenter

cohort study. Invest New Drugs. 38:211–218. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Landi L, D'Incà F, Gelibter A, Chiari R,

Grossi F, Delmonte A, Passaro A, Signorelli D, Gelsomino F, Galetta

D, et al: Bone metastases and immunotherapy in patients with

advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

7:3162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yin M, Guan S, Ding X, Zhuang R, Sun Z,

Wang T, Zheng J, Li L, Gao X, Wei H, et al: Construction and

validation of a novel web-based nomogram for patients with lung

cancer with bone metastasis: A real-world analysis based on the

SEER database. Front Oncol. 12:10752172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Demaria S and Formenti SC: The abscopal

effect 67 years later: From a side story to center stage. Br J

Radiol. 93:202000422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Walle T, Martinez Monge R, Cerwenka A,

Ajona D, Melero I and Lecanda F: Radiation effects on antitumor

immune responses: Current perspectives and challenges. Ther Adv Med

Oncol. 10:17588340177425752018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Morita Y, Saijo A, Nokihara H, Mitsuhashi

A, Yoneda H, Otsuka K, Ogino H, Bando Y and Nishioka Y: Radiation

therapy induces an abscopal effect and upregulates programmed

death-ligand 1 expression in a patient with non-small cell lung

cancer. Thorac Cancer. 13:1079–1082. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bang A and Schoenfeld JD: Immunotherapy

and radiotherapy for metastatic cancers. Ann Palliat Med.

8:312–325. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xing D, Siva S and Hanna GG: The abscopal

effect of stereotactic radiotherapy and immunotherapy: Fool's Gold

or El Dorado? Clin Oncol. 31:432–443. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fiorica F, Tebano U, Gabbani M, Perrone M,

Missiroli S, Berretta M, Giuliani J, Bonetti A, Remo A, Pigozzi E,

et al: Beyond abscopal effect: A meta-analysis of immune checkpoint

inhibitors and radiotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 13:23522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zheng Y, Liu X, Li N, Zhao A, Sun Z, Wang

M and Luo J: Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy could improve

the immune infiltration of melanoma in mice and enhance the

abscopal effect. Radiat Oncol J. 41:129–139. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wei J, Montalvo-Ortiz W, Yu L, Krasco A,

Ebstein S, Cortez C, Lowy I, Murphy AJ, Sleeman MA and Skokos D:

Sequence of alphaPD-1 relative to local tumor irradiation

determines the induction of abscopal antitumor immune responses.

Sci Immunol. 6:eabg01172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Park B, Yee C and Lee KM: The effect of

radiation on the immune response to cancers. Int J Mol Sci.

15:927–943. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mondini M, Levy A, Meziani L, Milliat F

and Deutsch E: Radiotherapy-immunotherapy combinations-Perspectives

and challenges. Mol Oncol. 14:1529–1537. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente

D, Murakami S, Hui R, Kurata T, Chiappori A, Lee KH, De Wit M, et

al: Overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in

stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 379:2342–2350. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gray JE, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D,

Murakami S, Hui R, Kurata T, Chiappori A, Lee KH, Cho BC, et al:

Three-year overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy

in stage III NSCLC-update from PACIFIC. J Thorac Oncol. 15:288–293.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Theelen WSME, Peulen HMU, Lalezari F, van

der Noort V, De Vries JF, Aerts JG, Dumoulin DW, Bahce I, Niemeijer

AL, De Langen AJ, et al: Effect of pembrolizumab after stereotactic

Body radiotherapy vs. pembrolizumab alone on tumor response in

patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Results of the

PEMBRO-RT phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.

5:1276–1282. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K,

Veruttipong D, Goldman JW, Formenti SC, Garon EB and Lee P:

Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of

pembrolizumab in the treatment of Non-small-cell lung cancer: A

secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:895–903. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bates JE, Morris CG, Milano MT, Yeung AR

and Hoppe BS: Immunotherapy with hypofractionated radiotherapy in

metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: An analysis of the National

Cancer Database. Radiother Oncol. 138:75–79. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Foster CC, Sher DJ, Rusthoven CG, Verma V,

Spiotto MT, Weichselbaum RR and Koshy M: Overall survival according

to immunotherapy and radiation treatment for metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer: A National Cancer Database analysis.

Radiat Oncol. 14:182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Welsh J, Menon H, Chen D, Verma V, Tang C,

Altan M, Hess K, De Groot P, Nguyen QN, Varghese R, et al:

Pembrolizumab with or without radiation therapy for metastatic

non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized phase I/II trial. J

Immunother Cancer. 8:e0010012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Theelen WSME, Chen D, Verma V, Hobbs BP,

Peulen HM, Aerts JG, Bahce I, Niemeijer AL, Chang JY, de Groot PM,

et al: Pembrolizumab with or without radiotherapy for metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer: A pooled analysis of two randomised

trials. Lancet Respir Med. 9:467–475. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu Z, Xu T, Chang P, Fu W, Wei J, Xia C,

Wang Q, Li M, Pu X, Huang F, et al: Efficacy and safety of immune

checkpoint inhibitors with or without radiotherapy in metastatic

non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Front Pharmacol. 14:10642272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tomaciello M, Conte M, Montinaro FR,

Sabatini A, Cunicella G, Di Giammarco F, Tini P, Gravina GL,

Cortesi E, Minniti G, et al: Abscopal effect on bone metastases

from solid tumors: A systematic review and retrospective analysis

of challenge within a challenge. Biomedicines. 11:11572023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rodríguez Plá M, Dualde Beltrán D and

Ferrer Albiach E: Immune checkpoints inhibitors and SRS/SBRT

synergy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer and melanoma: A

systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 22:116212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Geng Y, Zhang Q, Feng S, Li C, Wang L,

Zhao X, Yang Z, Li Z, Luo H, Liu R, et al: Safety and efficacy of

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with radiotherapy in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Cancer Med. 10:1222–1239. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kan C, Vargas G, Le Pape F and Clézardin

P: Cancer cell colonisation in the bone microenvironment. Int J Mol

Sci. 17:16742016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Santini D, Barni S, Intagliata S, Falcone

A, Ferraù F, Galetta D, Moscetti L, La Verde N, Ibrahim T, Petrelli

F, et al: Natural history of non-small-cell lung cancer with bone

metastases. Sci Rep. 5:186702015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lutz S, Balboni T, Jones J, Lo S, Petit J,

Rich SE, Wong R and Hahn C: Palliative radiation therapy for bone

metastases: Update of an ASTRO Evidence-Based Guideline. Pract

Radiat Oncol. 7:4–12. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Makita K, Hamamoto Y, Kanzaki H, Kataoka

M, Yamamoto S, Nagasaki K, Ishikawa H, Takata N, Tsuruoka S, Uwatsu

K, et al: Local control of bone metastases treated with external

beam radiotherapy in recent years: A multicenter retrospective

study. Radiat Oncol. 16:2252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

LeVasseur N, Clemons M, Hutton B, Shorr R

and Jacobs C: Bone-targeted therapy use in patients with bone

metastases from lung cancer: A systematic review of randomized

controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 50:183–193. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Facilissimo I, Natoli G, Gaspari F,

Comandone T, Bongiovanni D, Gollini P, Provenza C and Comandone A:

The role of bone radiotherapy during immune checkpoint inhibitors

treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: A single-institution

experience. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 17:175883592513324512025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Jayathilaka B, Mian F, Franchini F,

Au-Yeung G and IJzerman M: Cancer and treatment specific incidence

rates of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint

inhibitors: A systematic review. Br J Cancer. 132:51–57. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Suazo-Zepeda E, Bokern M, Vinke PC,

Hiltermann TJ, De Bock GH and Sidorenkov G: Risk factors for

adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients

with non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 70:3069–3080. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Dang TO, Ogunniyi A, Barbee MS and Drilon

A: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of PD-L1 positive advanced or

metastatic Non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther.

16:13–20. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|