Introduction

The fifth edition of the World Health Organization

(WHO) classification of breast cancer introduced a new form of the

disease called uncommon and salivary gland tumor (1). The majority of these breast and

salivary gland tumors have a good prognosis and limited

invasiveness, and are typically negative for immunohistochemistry

markers including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor

(PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (2,3). They

are typically indolent tumors with an excellent long-term

prognosis, even when triple negative. They have notably low rates

of lymph node metastasis and distant spread. By contrast,

conventional triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is biologically

aggressive, and is associated with a higher risk of early

recurrence and distant metastasis, and a markedly worse overall

prognosis. Thus, it is crucial to differentiate it from other

notably dangerous TNBC types. The prognosis of mucoepidermoid

carcinoma (MEC) is related to the grading of Elston-Ellis scoring

system, which is classified as low, medium and high grade according

to the proportion of tumor cystic components, nerve invasion,

necrosis and the number of mitoses per 10 high power fields

(4).

MEC accounts for 0.2–0.3% of the incidence rate of

breast cancer (1). It was first

reported in 1979 (5). Up to 2023,

the number of breast MEC cases reported in the global literature

was <70. Therefore, the present study aimed to improve the

current understanding of this tumor through a breast MEC and

literature review; understand its clinical features, typical

pathological morphology, immunohistochemical and molecular

characteristics and differential diagnosis; and to provide clinical

guidance for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this

tumor.

Case presentation

In August 2024, a 43 year old female patient found a

nodule in the upper outer quadrant of her right breast and was

admitted to Wuhu Hospital affiliated with East China Normal

University and Wuhu Second People's Hospital (Wuhu, China). There

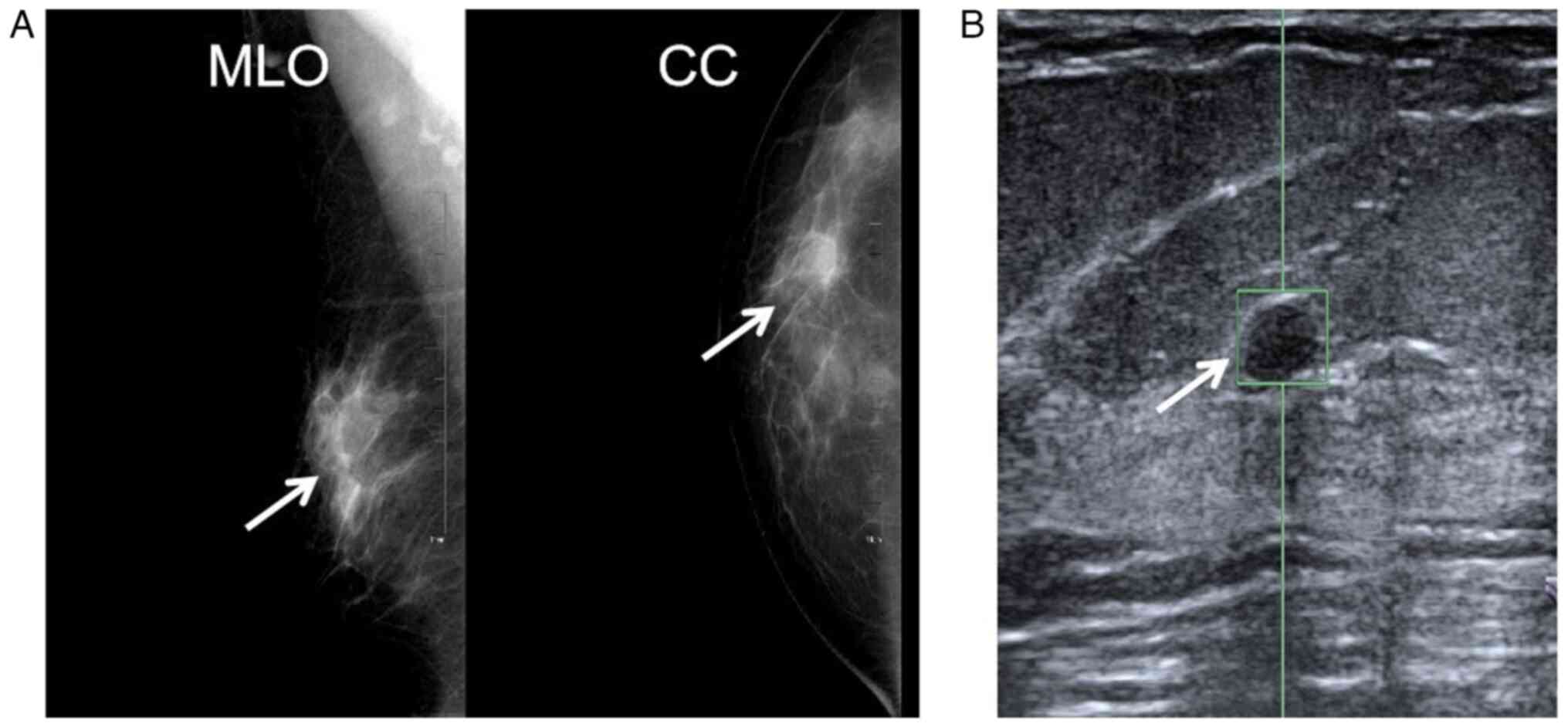

was no abnormal skin or nipple discharge. The mammogram showed an

oval-shaped isodense shadow in the upper outer quadrant of the

right breast, measuring ~1.7 cm in diameter. Automated breast

volume scanning showed a hypoechoic mass at the 9 o'clock position

of the right breast (~30 mm from the nipple and 15 mm from the skin

surface), which measured ~20×11 mm. The mass exhibited well-defined

borders, an irregular shape with shallow lobulation at the margins

and heterogeneous internal echogenicity (Fig. 1), suggestive of a benign tumor.

Tissues from breast rotational resection were sent

for standard pathological analysis. A pile of medium-textured,

gray-white, gray-yellow rotary-cut tissue measuring 1.5×1.0×1.0 cm

was found in the gross area. Microscopically, the tumor showed

cystic-solid growth, and papillary processes could be observed in

the capsule. The tumor was composed of mild intermediate,

epidermoid, mucous and eosinophilic fine cells. Cribriform gland

cavities and microcapsules of varying sizes were formed, which

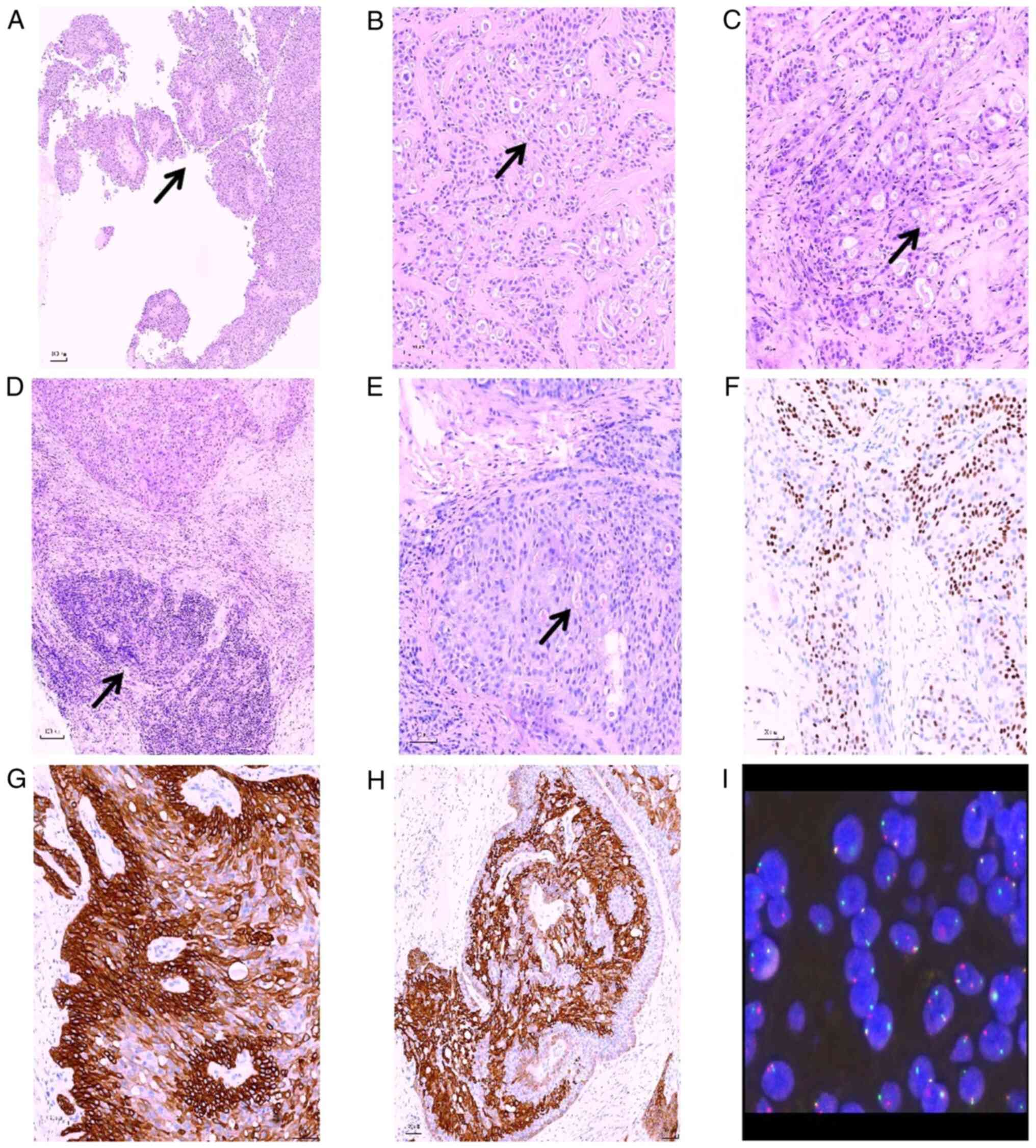

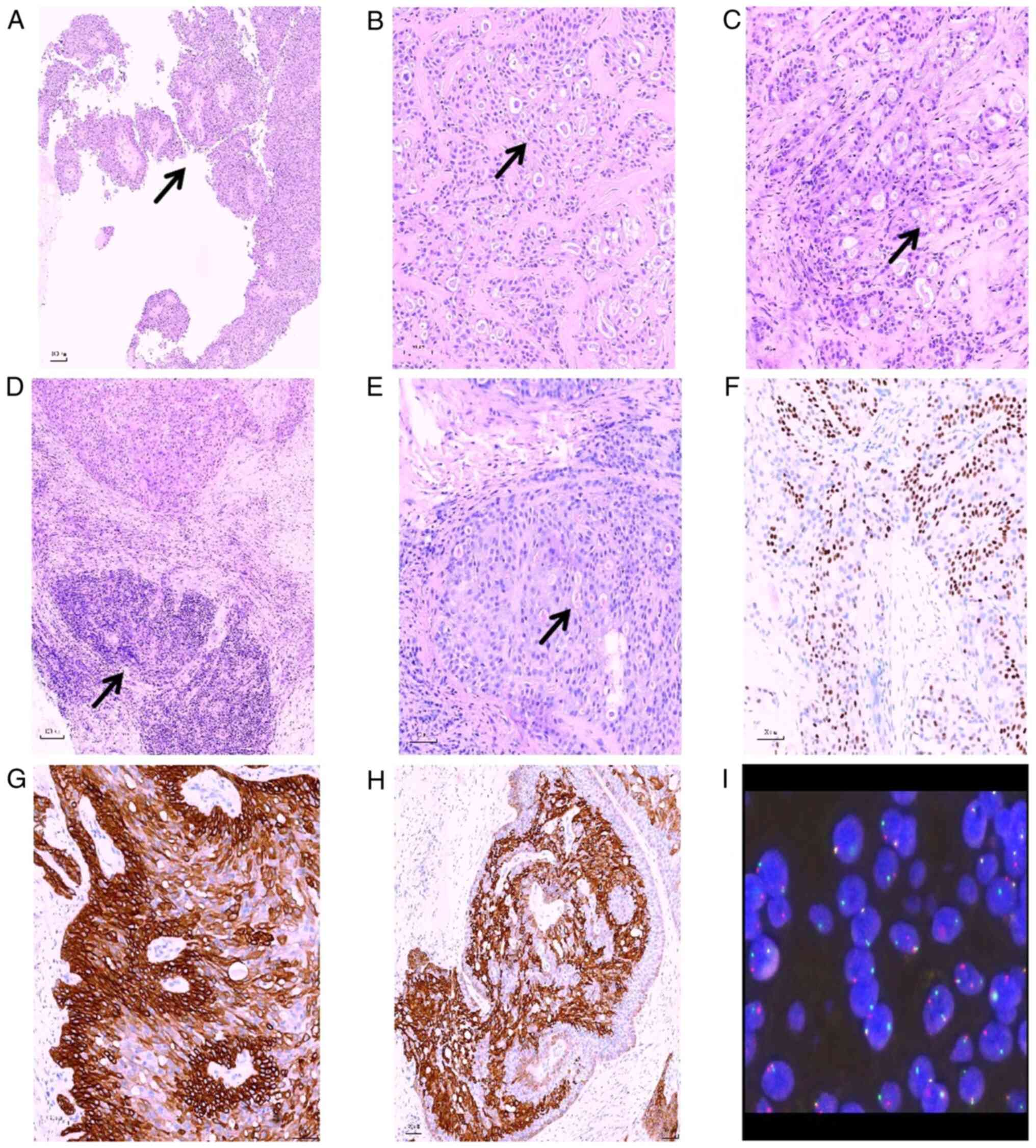

contained mucus or eosinophilic secretions (Fig. 2A-C). Lymphoid tissue hyperplasia

could be observed in the breast tissue around the tumor (Fig. 2D). Mitoses were infrequent. The

present case is classified as low-grade according to the

Elston-Ellis grading system (5).

| Figure 2.Pathological characteristics of breast

mucoepidermoid carcinoma. (A) The tumor was cystic, and the tumor

cells protruded into the cystic cavity to form a papillary

structure (arrow; H&E staining; magnification, ×100). (B) The

tumor cells were composed of alternating polygonal and mucoid

cells, and exhibited markedly small and visible nuclei. Nucleoli

was observed in polygonal cells, as well as eosinophilic cytoplasm

(arrow; H&E staining; magnification, ×200). (C) Ethmoid

glandular cavity or microcapsule structure could be observed

between the tumor cells, and there were eosinophilic secretions,

which may appear in the same cavity as blue-stained mucus (arrow;

H&E staining; magnification ×200). (D) Lymphoid tissue

hyperplasia could be observed in the breast tissue around the tumor

(arrow; H&E staining; magnification ×100). (E) Mucicarmine

staining showed positive staining of mucus both inside and outside

the tumor cells (arrow; H&E staining; magnification ×200).

Immunohistochemical staining showed that the tumor cells exhibited

a regional positive staining pattern for (F) p63, (G) CK5/6 and (H)

CK7 (magnification, ×200). (I) The mastermind like transcriptional

coactivator 2 gene showed a disrupted rearrangement, according to

the results of fluorescence in situ hybridization detection.

H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; CK, cytokeratin. |

Mucicarmine staining showed positive staining of

mucus inside and outside tumor cells (Fig. 2E). Tissues were fixed in 4% neutral

buffer formaldehyde solution at room temperature for 24 h, then

dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Following sectioning at a

thickness of 4 µm, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were dried in

an incubator at 60°C for 30 min to enhance adhesion to the slides.

The sections were then deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated

through a graded ethanol series. To quench endogenous peroxidase

activity, the tissues were treated with 3% hydrogen for 20 min at

room temperature. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on a

Benchmark XT automated immunohistochemistry stainer (Roche Tissue

Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's kit (OptiView DAB IHC

Detection Kit; cat. no. 760-700; Roche Diagnostics). This detection

kit is designed specifically for the Ventana Bench Mark series

fully automatic immunohistochemical staining instrument. All steps

(including blocking, primary antibody incubation, secondary

antibody/linker incubation, HRP polymer incubation, washing, and

DAB color development) are automatically completed by the

instrument according to the preset program.

Sections from known positive tissues were used as

positive controls, and PBS instead of primary antibody was used as

a negative control. The following primary antibodies were used: ER

(cat. no. IR078; Clone: SP1; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), PR (cat. no. IM361; Clone:16; Guangzhou LBP

Medicine Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), cytokeratin5/6

(CK5/6; cat. no. IM060; Clone: LBP1-CK5/6;Guangzhou LBP Medicine

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.); cytokeratin7 (CK7; cat. no.

IM061 Clone: LBP1-CK7; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science &

Technology Co., Ltd), transformation-related protein63 (p63; cat.

no. IM311; Clone:LBP1-P63; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3; cat. no.

IM277; Clone:LBP1-GATA3; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), SOX-10 (cat. no. IR349; Clone:LBP2-SOX10;

Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), Ki-67

(cat. no. IM098; Clone:LBP1-Ki67; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), TRPS-1 (cat. no. IR474; Clone:ZR382;

Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), Syn

(cat. no. IM136; Clone:LBP1-Syn; Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), S100 (cat. no. IM135; Clone:LBP1-S100;

Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The

stained sections were examined and imaged under a DM-2000 light

microscope (Leica Biosystems).

Immunohistochemical results showed that cytokeratin

(CK) 5/6 and p63 were positive in polygonal cells (Fig. 2F and G) cells; CK7 was positive in

mucoid cells (Fig. 2H); GATA

binding protein 3 (GATA3) and transcriptional repressor GATA

binding 1 (TRPS1) were positive (Fig.

S1A and B); S100 and SOX-10 were focal positive (Fig. S1C and D); SYN was negative

(Fig. S1E); ER was 20% positive

(Fig. S1F); PR was negative

(Fig. S1G); HER2 was 1+ (>10%

of invasive tumor cells showed faint, incomplete membrane staining;

Fig. S1H); and the Ki-67

proliferation index was ~10% (Fig.

S1I).

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections

were analyzed for mastermind like transcriptional coactivator 2

(MAML2) gene rearrangements using the ZytoLight SPEC MAML2 Dual

Color Break Apart Probe (ZYTOVISION GmbH; cat. no. Z-2014-200),

which consists of a SpectrumGreen-labeled probe targeting the 5′

region and a SpectrumOrange-labeled probe targeting the 3′ region

of the MAML2 gene. All aspects of probe design, including

nucleotide sequence, fragment length, enzymatic labeling and DNase

treatment for template removal, are optimized by the manufacturer

and constitute proprietary intellectual property. Sections of 4–5

µm thickness were mounted on charged slides, baked at 60°C for 60

min, deparaffinized in xylene, and dehydrated through a graded

ethanol series. Heat-induced pretreatment was performed in 1×

saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC; pH 6.3) at 80°C for 30 min,

followed by enzymatic digestion with 0.5 mg/ml pepsin in 0.01 N HCl

at 37°C for 15–30 min. Tissues were then post-fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin and dehydrated through a series of ethanol

solutions of increasing concentration. Hybridization was carried

out by applying 10 µl of the probe mixture onto the sample,

followed by a critical co-denaturation step at 82°C for 5 min. This

elevated temperature provides the energy required to disrupt the

hydrogen bonds in both the double-stranded DNA of the tissue of the

patient and the applied probe, denaturing them into single strands

and making the target genomic sequences accessible. Subsequently,

hybridization was allowed to proceed at 45°C for 16–20 h in a

humidified chamber.

Notably, post-hybridization stringency washing is a

critical step that must be carefully optimized according to the

manufacturer's instructions; commonly recommended conditions were

carried out, including washing in pre-warmed 2× SSC with 0.3% NP-40

at 73°C for 5 min, followed by a rinse in 2× SSC/0.05% Tween 20 at

room temperature. Slides were air-dried in the dark and

counterstained with DAPI. Analysis was performed on an

epifluorescence microscope using single interference filter sets

for orange and green. For each interference filter, monochromatic

images were acquired and merged using CytoVision (Leica

Microsystems). Analyses were performed in a minimum of 50 nuclei

harboring at least one copy of each signal. A specimen was

considered positive for MAML2 rearrangement when a minimum of 20%

of analyzed cells displayed split 3′MAML2 and 5′MAML2 signals or

single signals under a Leica DM6000 B motorized fluorescence

microscope. Fluorescence in situ hybridization detection

revealed a broken rearrangement of the MAML2 gene in the tumor

cells (Fig. 2I).

At 2 weeks after the rotational mastectomy, the

patient underwent right breast-conserving surgery, right axillary

sentinel lymph node biopsy and right breast fascial glandular flap

plasty. Postoperative pathology showed no metastatic carcinoma in

the right sentinel lymph nodes, no cancer infiltration at the

surgical margins of the breast-conserving procedure and a small

quantity of residual cancer tissue in the original surgical cavity.

Postoperative radiotherapy was administered, including whole-breast

radiotherapy (50 Gy/25 fractions) and tumor bed boost (10 Gy/5

fractions). After 8 months of monthly telephone and outpatient

follow-up the patient was alive, without any signs of

recurrence.

Discussion

The salivary glands are where MEC is most commonly

identified, followed by the tonsils, thyroid, pleura, lung, thymus,

esophagus and other areas (6–8).

However, it rarely happens in the breast. The breast gland MEC is

classified as salivary gland tumor according to the 2019 edition

WHO breast tumor classification (1). Its histological morphology is similar

to that of salivary gland MEC, which is composed of mucous,

intermediate (basal-like) and epidermis-like (squamous) cells.

Transparent cells and eosinophils can also be observed.

Pathological grading of mammary MEC is critically dependent on

histological features adapted from salivary gland systems,

emphasizing architecture, cytological atypia, mitoses and necrosis.

Low-grade tumors are indolent, while high-grade tumors behave

aggressively (9).

The majority of breast MEC cases are characterized

by negative expression of ER, PR and HER2. However, unlike other

TNBCs, they exhibit relatively good prognosis (10). Thus, distinguishing it from other

notably dangerous TNBC types is crucial. The clinical indications,

pathological morphology, molecular immunohistochemical

characteristics, pathological differential diagnosis, clinical

treatment and prognosis of breast MEC are as follows: Regarding

clinical features, up to 2023, the number of breast MEC cases

reported in the global literature was <70. The majority of cases

were case reports or small-scale case series studies. Case reports

were mainly from USA, Europe, Japan, China and other areas where

medical research is more developed. In previous years, a small

number of cases have been reported in China; however, the total

number of cases remains small. The age range of the patients is

wide, but the majority of patients are middle-aged and elderly

women (27–86 years old) (11). Most

patients exhibit minor pain or no discernible symptoms. Similar to

other breast cancer types, the common symptoms of MEC are breast

masses, and certain cases are accompanied by nipple discharge or

pain. The tumor can be cystic or solid, with a size of 0.5–11.0 cm

(mean, 3.5 cm). In previous studies, ultrasonography examination

revealed that the mass showed cystic and solid changes with clear

boundaries (9,11,12).

In regard to typical pathomorphological features,

MEC tumors show a cystic-solid growth pattern, marked vitreous

degeneration of the cyst wall, lymphocyte infiltration and

follicular structure in the stroma around the cyst wall. Solid or

papillary growth of the tumor can be observed in the capsule,

infiltrating into the surrounding cyst wall tissue, while the tumor

cells have a glandular cavity-like structure and secrete mucus in

part of the cavity. The tumor cells contain mucus-secreting cells,

clear cytoplasm and intermediate cells. Cystic or polycystic

structures and solid nests are typical structural patterns of

breast MEC. In low-grade MEC, the tumor cells in the cyst wall form

a papillary or polyp-like structure protruding into the cyst

cavity. Ethmoid glandular cavities and microcapsules of different

sizes can be formed between tumor cells, which contain mucus or

eosinophilic secretions. The ethmoid gland lumen or microcapsule

structure is considered a valuable morphological change in breast

MEC. Peritumor-associated lymphoid tissue hyperplasia is an

important diagnostic marker for breast MEC, which has been fully

recognized in salivary gland MEC. High-grade MEC of the breast has

shown the same cellular composition, but more solid components,

mainly epidermoid cells and intermediate cells, fine cell atypia,

increased mitosis, necrosis and nerve invasion. However, the

histological changes of high-grade breast MEC have been suggested

to be non-specific, and the diagnostic criteria remain unclear

(13). Previously reported

high-grade breast MEC cases may be a group of heterogeneous

tumors.

Regarding immunohistochemical and molecular

characteristics, epidermoid cells and intermediate cells express

high molecular weight CKs (such as CK5/6) and p63, while the

majority of mucoid cells express low-molecular weight keratins

(such as CK7). Breast MEC usually presents a typical

triple-negative immunophenotype (14). However, previous studies have shown

that it can express hormone receptors in different degrees. Most of

the reported cases of breast MEC have low ER expression (15,16).

The positive rate of ER in the present case was 20%. Previous

research has shown that the prognosis of patients with low levels

of hormone receptor expression was good (17). This is likely due to unique tumor

origin and molecular characteristics.Breast MEC arises from

salivary gland-like ductal cells (similar to salivary gland

tumors), not hormone-sensitive breast luminal cells (18). Its molecular drivers are unrelated

to estrogen signaling. Because tumor growth is not fueled by

estrogen signaling, it lacks the aggressive proliferative and

metastatic drive associated with hormone-dependent pathways. This

intrinsic ‘indolence’ is a key reason for its improved prognosis

(19,20). Low ER/PR positivity reflects passive

expression, not functional dependence. The tumor does not depend on

these signals for survival or growth (21). Low ER/PR expression typically occurs

in low-grade MEC, which inherently has positive outcomes regardless

of ER/PR status.

Breast MEC exhibits a lower incidence of MAML2

rearrangements (~38% of reported cases) compared with salivary

gland MEC (55–88%). The dominant fusion is CREB-regulated

transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1)-MAML2 from t(11;19) (q21;p13),

with rare CRTC3-MAML2 t(11;15) (q21;q26) fusion.

CRTC1/3:MAML2-positive breast MECs are associated with lower

histological grade and improved survival, similar to salivary MEC

(22,23). However, fusion-negative cases may

show aggressive behavior due to genomic instability. To date, there

have been 21 molecular analysis reports of breast MEC, including 7

cases carrying CRTC1-MAML2 and 1 case carrying CRTC3-MAML2

translocation (24). Breast MECs

lack TP53 mutations, which are found in high-grade forms of TNBCs,

and the MAML2 or EWS RNA binding protein 1 rearrangements

pathognomonic of salivary MECs. Breast MEC is molecularly distinct

from both salivary gland MEC and conventional TNBCs. While

CRTC1/3-MAML2 fusions define a subset with favorable prognosis,

dominant PI3K/AKT/mTOR dysregulation and EGFR/amphiregulin

activation offer actionable targets. Larger cohort studies using

RNA in situ hybridization and targeted Next-Generation

Sequencing are needed to validate these alterations and explore

fusion-independent oncogenic mechanisms (25). The molecular genetic characteristics

of tumors require further research.

With regard to differential diagnosis, intraductal

papilloma with common epithelial hyperplasia/squamous metaplasia

includes fibrous cystic wall, solid sieve-like hyperplasia of tumor

cells protruding from the cystic cavity, papillary structures with

fibrous vascular axis, relatively mild cells and

immunohistochemical expression of CK5/6. Careful identification of

different cellular components and morphological features, such as

mucus secretion, in MEC can aid in identification (1). Solid papillary carcinoma presents as

cystic papillary hyperplasia, with cells of the same size and

visible mucus inside, as well as invasive growth. However, there is

a lack of thick-walled cystic cavity and peripheral lymphocyte

infiltration. In a previous study, immunohistochemical staining

showed strong ER/PR positivity, CK5/6 and p63 negativity and SYN

positivity (1). Secretory carcinoma

presents as cystic, solid or papillary structures, and secretions

inside the microvesicles can be observed both inside and outside

the tumor cells. Furthermore, no thick infiltration of lymphocytes

is detected in the cyst wall or its surroundings. The

immunohistochemical results show that S100, SOX-10 and CD117 are

positive, whereas p63 and CK5/6 are negative. The combination of

the ETS variant transcription factor 6-neurotrophic tyrosine

receptor kinase 3 gene is the most relevant molecular

characteristic (15). Squamous

metaplasia is usually focal, with clear cellular atypia, keratosis

(keratinized beads) and lack of intracellular and extracellular

mucus (1). Clear cell sweat gland

adenoma is more common in the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, nipple

and areola. The histological features of the tumor are mostly

cystic and papillary hyperplasia, with clear cell morphology mixed

with transparent squamous cells. Small glandular structures are

scattered in the transparent cells, arranged by cuboidal

eosinophils, but there is no lymphocyte infiltration around the

cyst wall, mucous epithelium, intracellular or extracellular mucus.

There are multiple overlaps in histological features and molecular

genetic changes between low-grade MEC and breast clear cell sweat

gland adenoma (26).

Regarding the prognosis and clinical treatment of

breast MEC, at present, there is no standard treatment for breast

MEC, probably because it is rare and the treatment may involve

surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In the case of low-grade

malignant tumors, the tumor must be removed completely. For

patients with a high malignant degree and strong invasiveness,

radical mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection should be

performed for a good overall prognosis of MEC; however,

histological grade is an important prognostic factor, and

high-grade tumors have a poor prognosis. The prognosis of breast

MEC is associated with tumor grade and distant metastasis (14,15).

Lymph node metastasis can be found in all grades of breast MEC,

while distant metastasis can only be observed in high-grade cases.

The prognosis of low-grade breast MEC is good, while high-grade MEC

with distant metastasis often leads to mortality.

In conclusion, breast MEC is a rare malignant tumor

prone to misdiagnosis as other lesions. Pathological diagnosis

requires the integration of morphological features,

immunohistochemical profiling, specific staining techniques and

molecular testing. Comprehensive analysis of histological grading

is crucial for clinical management, enabling prognostic evaluation

while emphasizing the importance of differential diagnosis from

other histologically similar tumors. Histological grading provides

critical guidance for clinical management and prognostic

evaluation. Globally reported cases of breast MEC remain scarce.

The rarity of this neoplasm poses considerable challenges to

related research and data aggregation. Future efforts should

prioritize case data accumulation through international

collaboration, as well as multicenter studies to facilitate the

comprehensive investigation of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MX and ZXX conceived and designed the study. MX

analyzed and summarized the data and wrote the manuscript. CCC and

XYS collected the laboratory examination data and images of the

case. ZXX critically revised the manuscript. MX, CCC, XYS and ZXX

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient involved in the present study was

subjected to standard clinical practice and provided written

informed consent for the publication of medical data and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Foschini MP, Geyer FC, Marchio C and

Nishimura R: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. WHO Classification of

Tumours Editorial Board. WHO Classification of Tumours, Breast

Tumours, International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: pp.

149–50. 2019

|

|

2

|

Cserni G, Quinn CM, Foschini MP, Bianchi

S, Callagy G, Chmielik E, Decker T, Fend F, Kovács A, van Diest PJ,

et al: Triple-negative breast cancer histological subtypes with a

favourable prognosis. Cancers. 13:56942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cima L, Kaya H, Marchiò C, Nishimura R,

Wen HY, Fabbri VP and Foschini MP: Triple-negative breast

carcinomas of low malignant potential: Review on diagnostic

criteria and differential diagnoses. Virchows Arch. 480:109–126.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cipriani NA, Lusardi JJ, McElherne J,

Pearson AT, Olivas AD, Fitzpatrick C, Lingen MW and Blair EA:

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma: A comparison of histologic grading

systems and relationship to MAML2 rearrangement and prognosis. Am J

Surg Pathol. 43:885–897. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Patchefsky AS, Frauenhoffer CM, Krall RA

and Cooper HS: Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast.

Arch Pathol Lab Med. 103:196–198. 1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu C, Zhao Y, Chu W, Zhang F and Zhang Z:

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of esophagus combined with squamous

carcinoma of lung: A case report and literature review. J Cancer

Res Ther. 11:6582015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Goh GH, Lim CM, Vanacek T, Michal M and

Petersson F: Spindle cell mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the palatine

tonsil with CRTC1-MAML2 fusion transcript: Report of a rare case in

a 17-year-old boy and a review of the literature. Int J Surg

Pathol. 25:705–710. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hu HJ, Zhou RX, Liu F, Wang JK and Li FY:

You cannot miss it: Pancreatic mucoepidermoid carcinoma: A case

report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 97:e99902018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ye RP, Liao YH, Xia T, Kuang HA and Xiao

XL: Breast mucoepidermoid carcinoma: A case report and review of

literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 13:3192–3199. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Burghel GJ, Abu-Dayyeh I, Babouq N,

Wallace A and Abdelnour A: Mutational screen of a panel of tumor

genes in a case report of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast

from Jordan. Breast J. 24:1102–1104. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

He X, You J, Chen Y, Tang H, Ran J and Guo

D: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast, 3 cases report and

literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 102:e337072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen G, Liu W, Liao X, Yu F and Xie Y:

Imaging findings of the primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the

breast. Clin Case Rep. 10:e054492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Di Tommaso L, Foschini MP, Ragazzini T,

Magrini E, Fornelli A, Ellis IO and Eusebi V: Mucoepidermoid

carcinoma of the breast. Virchows Arch. 444:13–19. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yan M, Gilmore H and Harbhajanka A:

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast with MAML2 rearrangement: A

case report and literature review. Int J Surg Pathol. 28:787–792.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bean GR, Krings G, Otis CN, Solomon DA,

García JJ, van Zante A, Camelo-Piragua S, van Ziffle J and Chen YY:

CRTC1-MAML2 fusion in mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast.

Histopathology. 74:463–473. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mura MD, Clement C, Foschini MP, Borght

SV, Waumans L, Eyken PV, Hauben E, Keupers M, Weltens C, Smeets A,

et al: High-grade HER2-positive mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the

breast: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep.

17:5272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sherwell-Cabello S, Maffuz-Aziz A,

Rios-Luna NP, Pozo-Romero M, López-Jiménez PV and Rodriguez-Cuevas

S: Primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the breast. Breast J.

23:753–755. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lakhani SR, Ellis Ian O, Schnitt SJ, Tan

PH and van de Vijver MJ: WHO Classification of Tumours of the

Breast. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC);

2012

|

|

19

|

Howitt BE, Vivero M, Nucci MR, Fletcher

CD, Cipriani NA, Ott PA, Sholl LM, Doyle LA, Hornick JL and Parra

AR: The repertoire of genetic alterations in salivary gland-type

mammary carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 56:137–146. 2016.

|

|

20

|

Ross JS, Wang K, Rand JV, Sheehan CE,

Jennings TA, Al-Rohil RN, Otto GA, Curran JJ, Yelensky R, Lipson D,

et al: The distribution of CRTC1-MAML2 fusion gene in salivary

gland and salivary gland-type tumors of the head, neck, and breast:

A multi-institutional study. Modern Pathol. 31:725–731. 2018.

|

|

21

|

Pareja F, Arnaud Da Cruz P, Gularte-Mérida

R, Vahdatinia M, Li A, Geyer FC, da Silva EM, Nanjangud G, Wen HY,

et al: Pleomorphic adenomas and mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the

breast are underpinned by fusion genes. NPJ Breast Cancer.

6:202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Vered M and Wright JM: Update from the 5th

edition of the world health organization classification of head and

neck tumors: Odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumours. Head Neck

Pathol. 16:63–75. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nakayama T, Miyabe S, Okabe M, Sakuma H,

Ijichi K, Hasegawa Y, Nagatsuka H, Shimozato K and Inagaki H:

Clinicopathological significance of the CRTC3-MAML2 fusion

transcript inmucoepidermoid carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 22:1575–1581.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kawaguchi K, Ijichi H, Ueo H, Hisamatsu Y,

Omori S, Shigechi T, Kawaguchi K, Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Kubo M, et al:

Breast mucoepidermoid carcinoma with a rare CRTC3-MAML2 fusion. Int

Cancer Conf J. 13:481–487. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Venetis K, Sajjadi E, Ivanova M, Andaloro

S, Pessina S, Zanetti C, Ranghiero A, Citelli G, Rossi C, Lucioni

M, et al: The molecular landscape of breast mucoepidermoid

carcinoma. Cancer Med. 12:10725–10737. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Memon RA, Prieto Granada CN and Wei S:

Clear cell papillary neoplasm of the breast with MAML2 gene

rearrangement: Clear cell hidradenoma or Low-grade mucoepidermoid

carcinoma? Pathol Res Pract. 216:1531402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|