Introduction

As the malignancy with the third highest incidence

rate and the second highest rate of cancer-related deaths globally,

colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for 1.2 million new cases and

~600,000 fatalities annually (1,2).

Epidemiological modeling predicts a notable increase in disease

burden, with 2.5 million new CRC diagnoses forecast globally by

2035 (3). The epidemiological

landscape of China is particularly concerning, as the country

exhibits the world's highest absolute CRC burden due to its

population size. Recent surveillance data from the National Cancer

Center suggests that the incidence of CRC has increased to the

extent that the disease is now the second most commonly occurring

malignancy in China (4). Despite

advancements in early diagnosis and treatment methods, the

long-term survival rate and prognostic outcomes of patients with

CRC still face challenges (5).

Accurate prognosis assessment is crucial for formulating

individualized treatment plans, predicting survival duration and

optimizing patient management.

In recent years, numerous studies have shown that

inflammatory response, nutritional status and immune function play

pivotal roles in cancer initiation, progression and outcomes

(6–8). Therefore, identifying biomarkers that

can comprehensively reflect a patient's inflammatory, nutritional

and immune status holds significant importance for improving the

prognostic assessment of patients with CRC. The preoperative

hematological parameters of patients with cancer can reflect their

inflammatory, immune and nutritional statuses. Thus, multiple

inflammation indices derived from hematological examinations have

been demonstrated to be closely associated with cancer prognosis.

Key validated prognostic indicators include the

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (9), the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

(10), the lymphocyte-to-monocyte

ratio (11), the

fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (12),

the derived NLR (dNLR) (13), the

mean corpuscular volume-to-lymphocyte ratio (14), the systemic inflammation response

index (15), the systemic

immune-inflammation index (16),

the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) (17), the cumulative inflammation index

(18), the prognostic inflammatory

and nutritional index (19), the

hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score (20) and pan-immune-inflammation values

(21). Recently, the C-reactive

protein (CRP)-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index, an emerging

immune-nutrition scoring system, has garnered increasing attention

from researchers (22). The CALLY

index, integrating CRP, albumin and lymphocyte levels, provides a

comprehensive assessment of a patient's inflammatory, nutritional

and immune status.

Multiple studies have confirmed that the CALLY index

serves as an independent prognostic factor in patients with gastric

cancer and that it can predict prognosis (23–25).

Conversely, relatively limited evidence exists in the literature

regarding the association between the CALLY index and prognosis in

patients with CRC. Given this context, the present study was

designed to evaluate the prognostic value of the CALLY index in

patients with stage I–III CRC. Through retrospective analysis of

clinicopathological data and preoperative hematological parameters

of patients who underwent radical resection, the study sought to

determine whether the CALLY index could serve as an independent

predictor for both recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall

survival (OS) rates, thereby potentially offering a novel biomarker

for prognostic assessment in CRC.

Patients and methods

Patients

The present retrospective study analyzed

clinicopathological data and preoperative laboratory hematological

parameters (measured within 1 week before surgery) from patients

with stage I–III CRC who underwent radical resection (R0) at

Jingdezhen First People's Hospital (Jingdezhen, China) between

January 2012 and March 2020. All consecutive patients meeting the

eligibility criteria during this period were initially screened.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Histologically confirmed

primary CRC; ii) no neoadjuvant therapy; and iii) R0 resection with

curative intent. Exclusion criteria eliminated patients with: i)

Synchronous/metachronous malignancies; ii) hematological disorders;

iii) preoperative infection/immunodeficiency; iv) incomplete data;

v) non-radical resection; and vi) receival of neoadjuvant therapy.

All data were extracted from the hospital's maintained

database.

Treatment and follow-up

The disease staging was determined using the eighth

edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer

Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) classification (26). Comorbidities was defined as

pre-existing comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases,

pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and

chronic liver disease. Postoperative anastomotic leakage

specifically referred to anastomotic leakage occurring within 30

days after surgery. Postoperative adjuvant therapy primarily

comprised chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other treatment modalities

based on these core therapeutic approaches. Patients with stage II

or III CRC received postoperative adjuvant therapy when deemed

clinically appropriate based on their overall health status.

Postoperative surveillance included contrast-enhanced computed

tomography scans performed at minimum every 6 months and blood

tests conducted every 3 months. Patients were followed up regularly

through outpatient visits or telephone interviews every 3 months

beginning on postoperative day 1 until the study endpoint, defined

as either patient death or March 31, 2025, whichever occurred

first. For outcome assessment, RFS time was calculated as the time

from surgery to CRC recurrence, last follow-up or death, while OS

time was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause

or last follow-up for surviving patients.

Determination of inflammatory

markers

All calculations for inflammatory markers are

presented in Table I, with the

CALLY index calculated as follows: Albumin (g/dl) × lymphocyte

count (n/µl)/[CRP (mg/dl) ×104] (22).

| Table I.Inflammatory marker names, formulae

and optimal cut-off values. |

Table I.

Inflammatory marker names, formulae

and optimal cut-off values.

| Marker | Calculation

formula | Optimal cutoff

value |

|---|

| C-reactive

protein-albumin-lymphocyte index | Albumin (g/dl) ×

lymphocyte count (/µl)/[CRP (mg/dl) ×104] | 6.790 |

| Derived

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | Neutrophils/(white

blood cells-neutrophils) | 2.320 |

| Fibrinogen-to-albumin

ratio | Fibrinogen

(g/l)/albumin (g/l) ×100 | 0.095 |

| Hemoglobin, albumin,

lymphocyte and platelet scores | Hemoglobin (g/l) ×

albumin (g/l) × lymphocytes/platelets | 35.130 |

| Cumulative

inflammatory index | (Corpuscular volume ×

width of erythrocyte distribution × neutrophils)/(lymphocytes

×1,000) | 7.275 |

|

Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio |

Lymphocyte/monocyte | 2.890 |

| Ratio between the

mean corpuscular volume and lymphocytes | Corpuscular

volume/lymphocytes | 72.310 |

|

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

Neutrophil/lymphocytes | 3.225 |

| Prognostic immune and

nutritional index | [Albumin (g/dl)

×0.9]-[monocytes (mm3) × 0.0007] | 3.255 |

|

Pan-immune-inflammatory values | Neutrophils ×

monocytes × platelets/lymphocytes | 391.72 |

|

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

Platelets/lymphocytes | 135.980 |

| Prognostic

nutritional index | Albumin (g/l) + 5 ×

lymphocytes (109/l) | 45.825 |

| Systemic

immune-inflammation index | Platelets ×

neutrophils/lymphocytes | 532.985 |

| Systemic

inflammatory response index | Neutrophils ×

monocytes/lymphocytes | 2.390 |

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R

software (version 4.3.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

The following R packages were employed: pROC (version 1.18.5) for

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with the

area under the curve (AUC) calculated to determine the optimal

cutoff value using the Youden index; survival (version 3.6.4) and

survminer (version 0.4.9) for survival analyses; and rstatix

(version 0.7.2) for statistical testing. Based on the optimal

cutoff, the patients were stratified into high-CALLY and low-CALLY

groups. Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed

as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using independent

samples t-tests, while non-normally distributed continuous

variables are presented as median (Q1-Q3) and

analyzed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Categorical variables are

reported as n (%) and were compared using χ2 tests or

Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. All tests were two-sided,

with P<0.05 considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards

regression models were constructed using the survival package to

estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

for RFS and OS. Variables with values of P<0.05 upon univariate

analysis were included in the multivariate model. Survival

probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves, with

between-group differences assessed by log-rank tests.

Ethical approval

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics

Committee at Jingdezhen First People's Hospital (approval no.

jdzyykt202514). The requirement for informed consent was waived due

to the retrospective nature of the study and data

anonymization.

Results

Patient characteristics

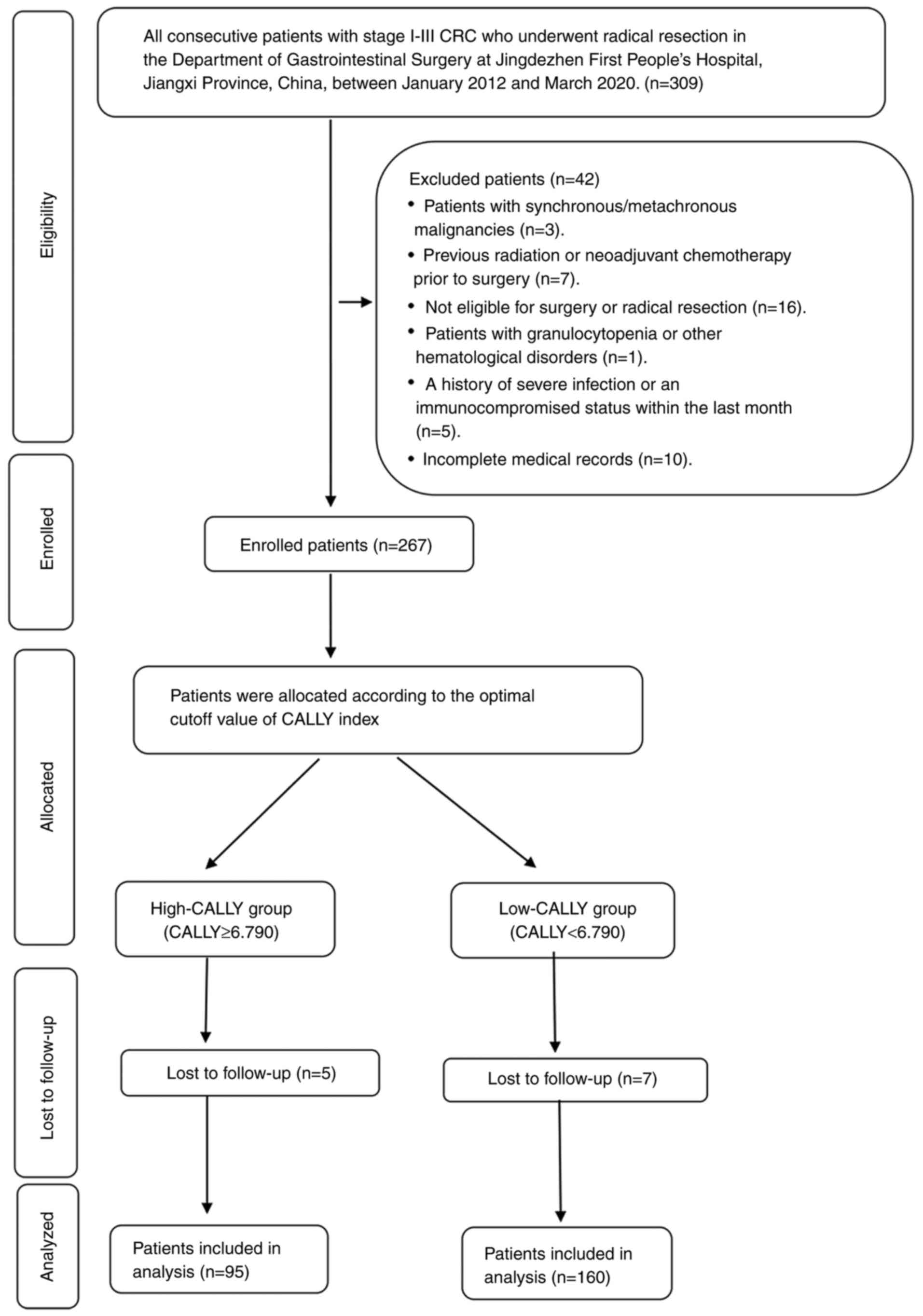

The present study consecutively screened 309

patients with stage I–III CRC undergoing radical resection

(Fig. 1). After applying exclusion

criteria (n=42) and accounting for loss to follow-up (n=12), the

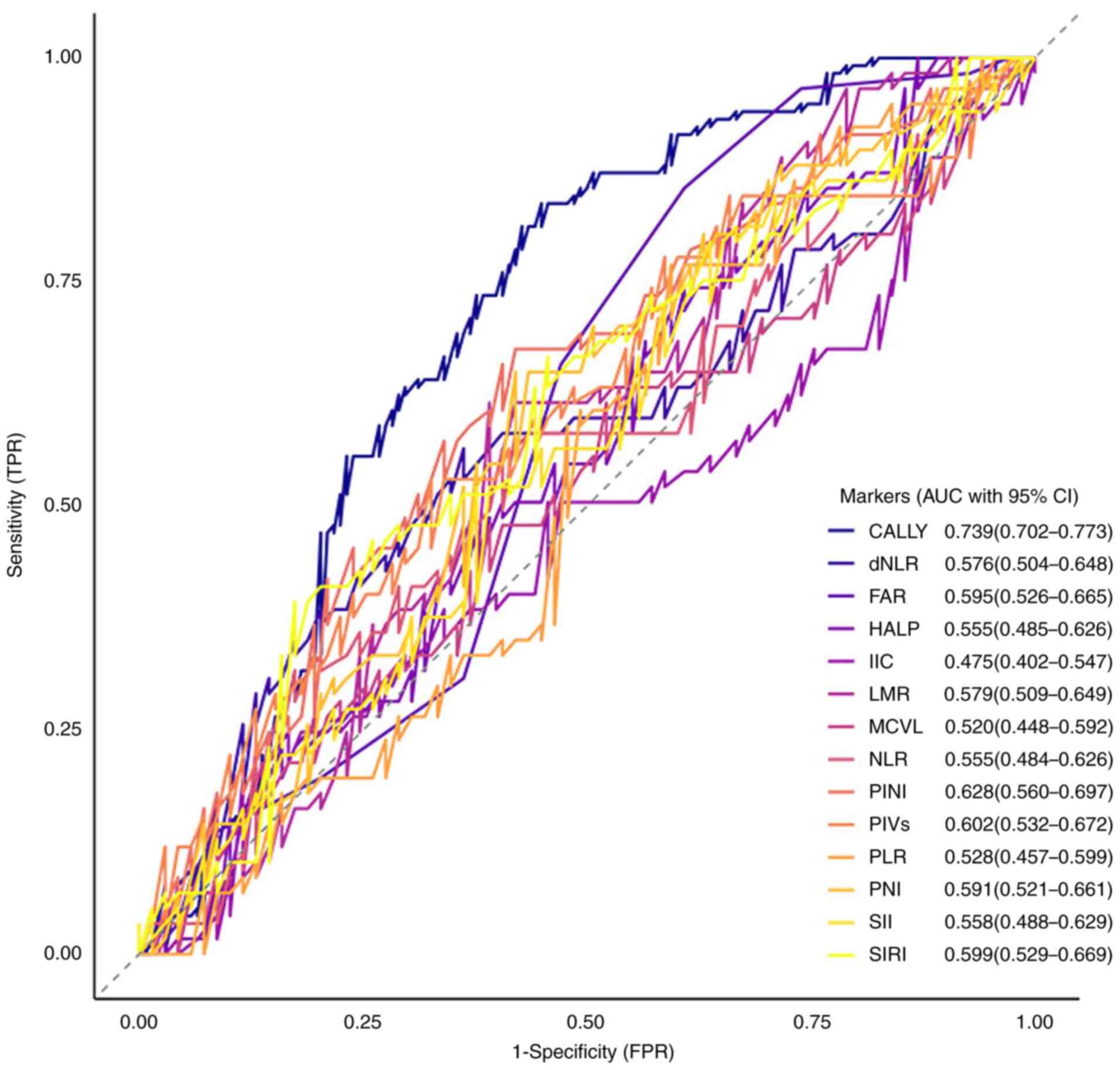

final cohort comprised 255 patients. ROC curve analysis evaluated

the prognostic performance of 14 inflammatory markers for clinical

outcomes in stage I–III CRC. The CALLY index demonstrated superior

discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.739 (95% CI, 0.702–0.773),

significantly outperforming all other biomarkers (Fig. 2). Stratified by the CALLY cutoff of

6.790 (Table I), the cohort

comprised 160 low-CALLY (<6.790) and 95 high-CALLY (≥6.790)

patients (Table II). The low-CALLY

group was associated with more aggressive tumor biology,

characterized by higher rates of poorly differentiated histology

(26.25 vs. 6.32%; P<0.001), advanced T4 stage (71.25 vs. 49.47%;

P<0.001), nodal metastasis (N1-2: 74.38 vs. 16.84%; P<0.001),

and stage III disease (73.12 vs. 16.84%; P<0.001). Clinically,

these patients more frequently required adjuvant therapy (75.62 vs.

45.26%; P<0.001), alongside significantly worse RFS (38.33±19.03

vs. 52.93±15.57 months; P<0.001) and OS (44.01±16.22 vs.

54.26±13.46 months; P<0.001) times that were visually

substantiated by pronounced separation in Kaplan-Meier curves

(Figs. 3 and 4). Notably, elevated CA125 (23.08 vs.

10.14%; P=0.005) and CA19-9 (24.79 vs. 14.49%; P=0.038) were more

prevalent in the high-CALLY group despite its less advanced

pathology. No significant intergroup differences existed in terms

of age, sex, tumor location, surgical approach, blood loss,

comorbidities, anastomotic leakage and tumour size P>0.05),

while the median (Q1-Q3) CALLY values

robustly distinguished the cohorts [low-CALLY, 2.62 (1.62–4.64) vs.

high-CALLY, 12.97 (9.88–17.16); P<0.001]. Collectively, low

CALLY status is associated with advanced disease, intensified

treatment needs and inferior survival, graphically validated by

stratified survival analyses, positioning it as a significant

prognostic integrator of inflammatory-nutritional imbalance in

CRC.

| Table II.Clinicopathological characteristics

of colorectal cancer patients by CALLY score group. |

Table II.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of colorectal cancer patients by CALLY score group.

|

|

| CALLY |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | Total (n=255) | Low (n=160) | High (n=95) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 62.58±12.49 | 62.34±12.87 | 62.98±11.90 | 0.695 |

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.927 |

|

Male | 144 (56.47) | 90 (56.25) | 54 (56.84) |

|

|

Female | 111 (43.53) | 70 (43.75) | 41 (43.16) |

|

| Tumor location |

|

|

| 0.808 |

|

Colon | 149 (58.43) | 95 (59.38) | 54 (56.84) |

|

|

Rectum | 106 (41.57) | 65 (40.63) | 41 (43.16) |

|

| Surgical

approach |

|

|

| 0.662 |

|

Open | 173 (67.84) | 114 (71.25) | 59 (62.11) |

|

|

Laparoscopic | 82 (32.16) | 46 (28.75) | 36 (37.89) |

|

| Tumor size ≥3.5

cm |

|

|

| 0.077 |

| No | 95 (37.25) | 53 (33.13) | 42 (44.21) |

|

|

Yes | 160 (62.75) | 107 (66.88) | 53 (55.79) |

|

| Blood loss,

mla | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 0.093 |

|

| (50.00–100.00) | (50.00–100.00) | (50.00–100.00) |

|

| Comorbidities |

|

|

| 0.062 |

| No | 201 (78.82) | 132 (82.50) | 69 (72.63) |

|

|

Yes | 54 (21.18) | 28 (17.50) | 26 (27.37) |

|

| Anastomotic

leakage |

|

|

| 0.437 |

| No | 240 (94.12) | 152 (95.00) | 88 (92.63) |

|

|

Yes | 15 (5.88) | 8 (5.00) | 7 (7.37) |

|

| Pathological

pattern |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Well | 18 (7.06) | 10 (6.25) | 8 (8.42) |

|

|

Moderate | 189 (74.12) | 108 (67.50) | 81 (85.26) |

|

|

Poor | 48 (18.82) | 42 (26.25) | 6 (6.32) |

|

| T stage |

|

|

| <0.001 |

| I | 2 (0.78) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.11) |

|

| II | 57 (22.35) | 21 (13.13) | 36 (37.89) |

|

|

III | 35 (13.73) | 25 (15.6) | 10 (10.53) |

|

| IV | 161 (63.14) | 114 (71.25) | 47 (49.47) |

|

| N stage |

|

|

| <0.001 |

| 0 | 120 (47.06) | 41 (25.63) | 79 (83.16) |

|

| I | 103 (40.39) | 92 (57.50) | 11 (11.58) |

|

| II | 32 (12.55) | 27 (16.88) | 5 (5.26) |

|

| TNM stage |

|

|

| <0.001 |

| I | 42 (16.47) | 4 (2.50) | 38 (40.00) |

|

| II | 80 (31.37) | 39 (24.38) | 41 (43.16) |

|

|

III | 133 (52.16) | 117 (73.13) | 16 (16.84) |

|

| P-adjuvant

therapy |

|

|

| <0.001 |

| No | 91 (35.69) | 39 (24.38) | 52 (54.74) |

|

|

Yes | 164 (64.31) | 121 (75.63) | 43 (45.26) |

|

| RFS, months | 43.76±19.14 | 38.33±19.03 | 52.93±15.57 | <0.001 |

| OS, months | 47.83±16.01 | 44.01±16.22 | 54.26±13.46 | <0.001 |

| CEA ≥5 ng/ml |

|

|

| 0.031 |

| No | 166 (65.10) | 120 (75.00) | 46 (48.42) |

|

|

Yes | 89 (34.90) | 40 (25.00) | 49 (51.58) |

|

| CA19-9 ≥30

U/ml |

|

|

| 0.038 |

| 0 | 206 (80.78) | 140 (87.50) | 66 (69.47) |

|

| 1 | 49 (19.22) | 20 (12.50) | 29 (30.53) |

|

| CA125 ≥25 U/ml |

|

|

| 0.005 |

| No | 214 (83.92) | 146 (91.25) | 68 (71.58) |

|

|

Yes | 41 (16.08) | 14 (8.75) | 27 (28.42) |

|

| CALLYa | 4.93 | 2.62 | 12.97 | <0.001 |

|

| (2.16–10.53) | (1.62–4.64) | (9.88–17.16) |

|

Prognostic significance of CALLY in

CRC survival

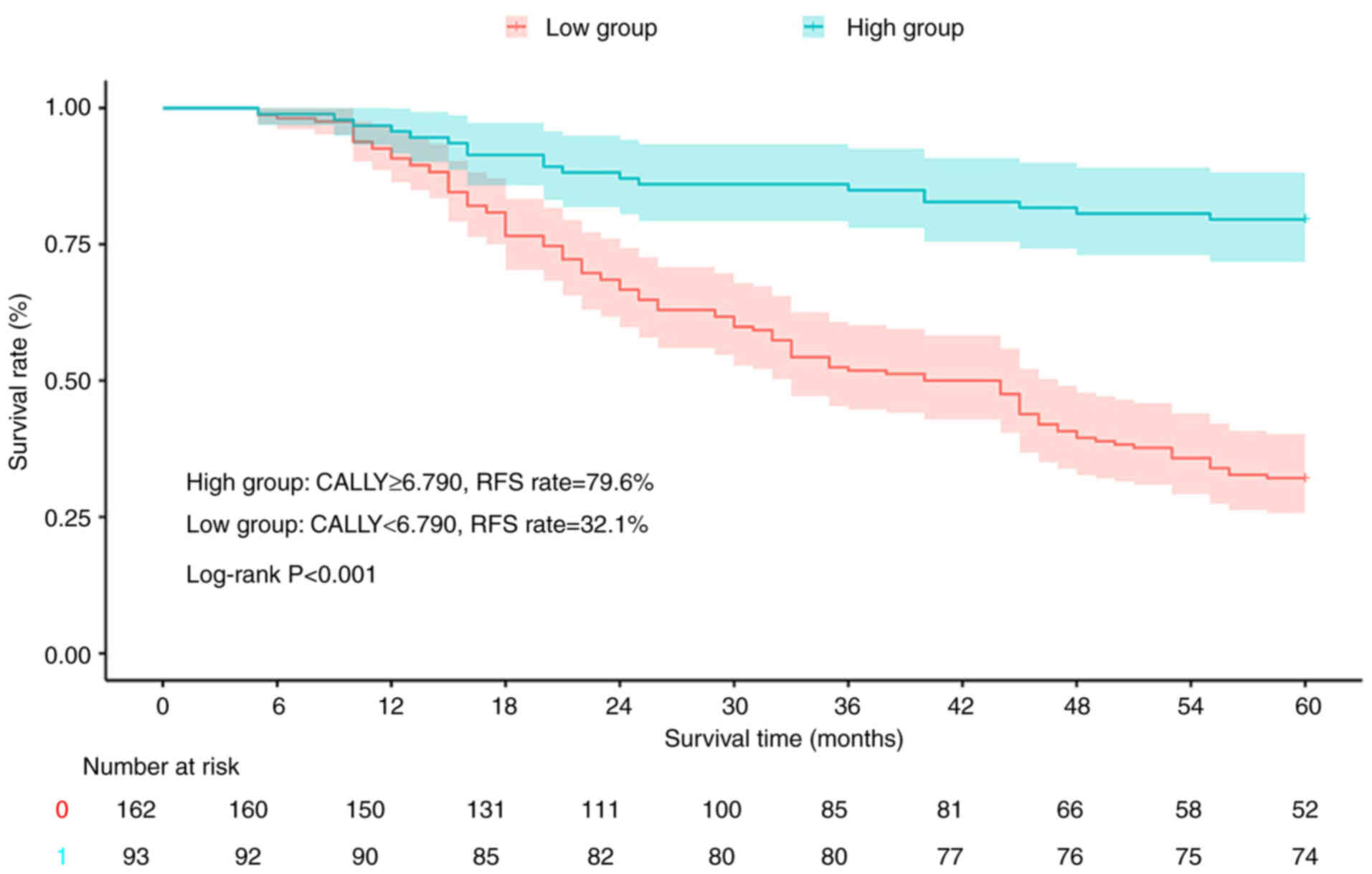

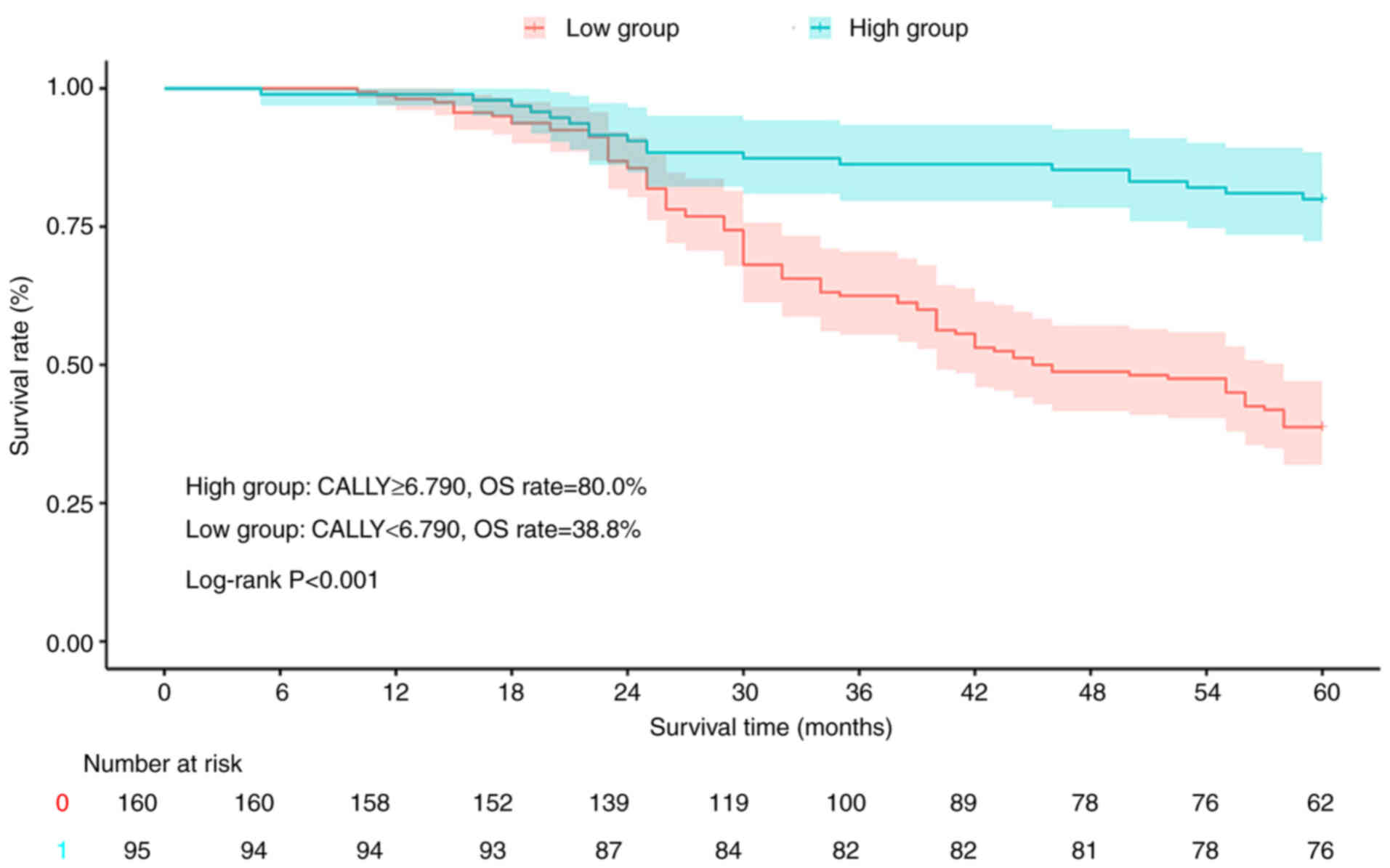

Stratification based on the CALLY index revealed

significant survival disparities among the patients with CRC.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the high-CALLY group (≥6.790) had

superior RFS (79.6 vs. 32.1%; log-rank P<0.001; Fig. 3) and OS (80.0 vs. 38.8%; log-rank

P<0.001; Fig. 4) rates compared

with the low-CALLY group (<6.790).

COX regression analysis of 5-year RFS

rate in patients with CRC

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

established CALLY as an independent predictor of RFS in CRC

(Table III). In the univariate

analysis, high CALLY exhibited a strong association with improved

RFS (HR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.14–0.35; P<0.001), outperforming

conventional biomarkers including CA19-9 (HR, 1.57; 95% CI,

1.04–2.38; P=0.032), CA125 (HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.36–3.07;

P<0.001) and CEA (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.01–2.06; P=0.041). After

adjusting for clinicopathological confounders in multivariate

analysis, CALLY retained independent significance (HR, 0.56; 95%

CI, 0.35–0.90; P=0.016), while among the other factors, only nodal

metastasis (N1-2 vs. N0: HR, 6.71; 95% CI, 4.17–10.81; P<0.001),

poor differentiation (moderate/poor vs. well: HR, 2.79; 95% CI,

1.88–4.16; P<0.001), advanced TNM stage (I vs. II–III: HR 2.59,

1.03–6.51; P=0.043) and elevated CA19-9 (>30 vs. ≤30 U/ml: HR,

1.69; 95% CI, 1.06–2.71; P=0.028) remained significant. Notably,

tumor size (P=0.114), blood loss (P=0.100), CEA (0.213), CA125

(0.755), advanced T stage (P=0.056) and adjuvant therapy (P=0.082)

lost statistical significance after adjustment.

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analysis

for recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with colorectal

cancer patients. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with colorectal

cancer patients.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (female vs.

male) | 0.85

(0.60–1.20) | 0.352 | - | - |

| Age (≥60 vs. <60

years) | 0.80

(0.56–1.14) | 0.211 | - | - |

| Tumor location

(rectum vs. colon) | 0.90

(0.63–1.28) | 0.564 | - | - |

| Surgical approach

(laparoscopic vs. open) | 0.20

(0.03–1.42) | 0.107 | - | - |

| Tumor size (≥3.5

vs. <3.5 cm) | 1.78

(1.22–2.61) | 0.003 | 1.51

(0.90–2.54) | 0.114 |

| Blood loss (≥100

vs. <100 ml) | 2.53

(1.56–4.08) | <0.001 | 1.83

(0.89–3.76) | 0.100 |

| Predisease (yes vs.

no) | 0.72

(0.46–1.13) | 0.156 | - | - |

| Anastomotic leakage

(yes vs. no) | 0.58

(0.24–1.42) | 0.236 | - | - |

| Pathological

pattern (moderate and poor vs. well) | 3.76

(2.58–5.48) | <0.001 | 2.79

(1.88–4.16) | <0.001 |

| T stage (I and II

vs. III and IV) | 3.29

(1.89–5.73) | <0.001 | 1.75

(0.98–3.12) | 0.056 |

| N stage (0 vs. I

and II) | 7.88

(4.95–12.54) | <0.001 | 6.71

(4.17–10.81) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage (I vs.

III and III) | 12.04

(3.83–37.87) | <0.001 | 2.59

(1.03–6.51) | 0.043 |

| P-adjuvant therapy

(yes vs. no) | 3.77

(2.40–5.92) | <0.001 | 1.59

(0.94–2.69) | 0.082 |

| CEA (>5 vs. ≤5

ng/ml) | 1.45

(1.01–2.06) | 0.041 | 0.76

(0.49–1.17) | 0.213 |

| CA125 (>25 vs.

≤25 U/ml) | 2.05

(1.36–3.07) | <0.001 | 0.92

(0.54–1.56) | 0.755 |

| CA19-9 (>30 vs.

≤30 U/ml) | 1.57

(1.04–2.38) | 0.032 | 1.69

(1.06–2.71) | 0.028 |

| CALLY (high vs.

low) | 0.22

(0.14–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.56

(0.35–0.90) | 0.016 |

COX regression analysis of 5-year OS

rate in patients with CRC

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

established CALLY as an independent predictor of OS in CRC

(Table IV). Upon univariate

analysis, high CALLY exhibited a profound protective effect on OS,

with an HR of 0.26 (95% CI, 0.16–0.43; P<0.001), outperforming

all other variables including nodal metastasis (HR, 7.95; 95% CI,

4.79–13.18; P<0.001), poor differentiation (HR, 3.69; 95% CI,

2.50–5.45; P<0.001) and elevated CA19-9 (HR, 1.74; 95% CI,

1.14–2.65; P=0.010). Following multivariate adjustment for

clinicopathological confounders, CALLY retained robust independent

significance (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.27–0.82; P=0.008), while nodal

metastasis (HR, 5.41; 95% CI, 2.93–9.98; P<0.001), poor

differentiation (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.54–3.81; P<0.001) and

elevated CA19-9 (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.02–2.57; P=0.043) remained

significant, alongside advanced TNM stage (HR, 1.74; 95% CI,

1.03–2.95; P=0.040). Conventional biomarkers (CEA and CA125),

anatomical factors (T stage), and treatment variables (adjuvant

therapy) lost statistical significance (P>0.05) after

adjustment, along with tumor size (P=0.121) and intraoperative

blood loss (P=0.154), which were significant in the univariate

analysis.

| Table IV.Univariate and multivariate analysis

for overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer. |

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (female vs.

male) | 0.77

(0.53–1.11) | 0.158 | - | - |

| Age (≥60 vs. <60

years) | 0.81

(0.56–1.17) | 0.263 | - | - |

| Tumor location

(rectum vs. colon) | 0.86

(0.59–1.25) | 0.440 | - | - |

| Surgical approach

(laparoscopic vs. open) | 0.20

(0.03–1.42) | 0.107 | - | - |

| Tumor size (≥3.5

vs. <3.5 cm) | 2.28

(1.50–3.47) | <0.001 | 1.57

(0.89–2.76) | 0.121 |

| Blood loss (≥100

vs. <100 ml) | 2.94

(1.81–4.78) | <0.001 | 2.01

(0.77–5.25) | 0.154 |

| Predisease (yes vs.

no) | 0.75

(0.47–1.20) | 0.230 | - | - |

| Anastomotic leakage

(yes vs. no) | 0.66

(0.27–1.63) | 0.372 | - | - |

| Pathological

pattern (moderate and poor vs. well) | 3.69

(2.50–5.45) | <0.001 | 2.42

(1.54–3.81) | <0.001 |

| T stage (I and II

vs. III and IV) | 4.65

(2.35–9.18) | <0.001 | 1.44

(0.63–3.30) | 0.394 |

| N stage (0 vs. I

and II) | 7.95

(4.79–13.18) | <0.001 | 5.41

(2.93–9.98) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage (I vs.

III and III) | 15.56

(3.84–63.01) | <0.001 | 1.74

(1.03–2.95) | 0.040 |

| P-adjuvant therapy

(yes vs. no) | 4.27

(2.58–7.06) | <0.001 | 1.64

(0.95–2.85) | 0.077 |

| CEA (>5 vs. ≤5

ng/ml) | 1.61

(1.11–2.32) | 0.011 | 0.90

(0.58–1.38) | 0.622 |

| CA125 (>25 vs.

≤25 U/ml) | 1.82

(1.19–2.81) | 0.006 | 1.01

(0.60–1.71) | 0.971 |

| CA19-9 (>30 vs.

≤30 U/ml) | 1.74

(1.14–2.65) | 0.010 | 1.61

(1.02–2.57) | 0.043 |

| CALLY (high vs.

low) | 0.26

(0.16–0.43) | <0.001 | 0.47

(0.27–0.82) | 0.008 |

Discussion

The CALLY index derives its prognostic power from

quantifying a pathophysiological triad that orchestrates CRC

progression through tumor microenvironment (TME)-specific

mechanisms. Elevated CRP levels reflect activation of

interleukin-6/Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3 signaling, which expands myeloid-derived suppressor

cells (MDSCs) that spatially exclude cytotoxic T lymphocytes from

tumor nests, a hallmark of ‘immune-excluded’ CRC subtypes (27,28).

Concurrently, hypoalbuminemia disrupts gut barrier integrity,

permitting translocation of procarcinogenic microbiota (for

example, Fusobacterium nucleatum) that activate transforming

growth factor-β signaling (29,30).

This further amplifies MDSC-mediated immunosuppression by inducing

regulatory T cell differentiation and programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) upregulation on tumor-associated macrophages (31). Lymphopenia completes this vicious

cycle by depleting CD103+ tissue-resident memory T cells

critical for controlling microsatellite-stable CRC (32). Collectively, these processes

establish an immunosuppressive TME favoring metastasis.

In gastric cancer research, Hashimoto et al

(33) demonstrated that the

high-CALLY group (cut-off value: 3.28) exhibited a significantly

higher proportion of early-stage cases (stage I: 71.5%; P=0.019)

and lower venous invasion rates compared with the low-CALLY group.

These findings align closely with the present study, where the

high-CALLY group (≥6.790) displayed superior tumor biological

characteristics, including significantly reduced rates of poor

differentiation (6.32 vs. 26.25%), T4 invasion (49.47 vs. 71.25%),

lymph node metastasis (N1-2 stage: 16.84 vs. 74.38%) and stage III

disease (16.84 vs. 73.12%) (all P<0.001). Paradoxically, despite

the favorable prognosis, the high-CALLY group showed elevated

levels of CA125 (23.08 vs. 10.14%) and CA19-9 (24.79 vs. 14.49%).

This apparent contradiction may be explained by enhanced

immunoediting mechanisms, such as intact lymphocyte function,

mediated through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, which

efficiently eliminates antigen-expressing tumor cells, leading to

the release of tumor-associated antigens (e.g., CA125/CA19-9) into

the bloodstream (34,35). Single-cell sequencing further

reveals that specific T-cell subsets (for example, tissue-resident

memory T cells) may modulate biomarker release dynamics by

regulating immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 (36). Future studies should explore the

combined prognostic value of serial CALLY measurements and tumor

markers.

The prognostic role of the CALLY index in advanced

CRC has been established. Furukawa et al (37) demonstrated its superiority in

metastatic settings, showing a 2.8-fold increased mortality risk in

patients with colorectal liver metastasis (95% CI, 1.6–4.9;

P<0.001) compared with conventional NLR/PNI biomarkers. The

present study extends these findings to stage I–III CRC through

three key analytical approaches. First, in a head-to-head

comparison of 14 prognostic markers, the CALLY index achieved the

highest discriminative power (AUC, 0.739). Second, multivariable

Cox models confirmed its independence from TNM stage and age (OS:

HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.16–3.98; P=0.015; and RFS: HR, 2.34; 95% CI,

1.32–4.15; P=0.003). Most notably, Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed

significant survival disparities, with low-CALLY patients

exhibiting 23.8 and 31.6% absolute reductions in 5-year OS (58.3

vs. 82.1%; P=0.008) and RFS (45.2 vs. 76.8%; P<0.001),

respectively. This tripartite validation, spanning ROC performance,

regression stability and survival curve divergence, solidifies the

CALLY index as a pan-stage prognostic tool.

The present study has several limitations that

warrant consideration. First, the single-center retrospective

design and relatively limited sample size may introduce selection

bias, highlighting the need for future multicenter studies with

larger cohorts to validate the findings. Second, the proposed CALLY

cutoff value was derived from a single institutional dataset,

necessitating external validation through collaborative multicenter

research to confirm its generalizability across diverse

populations. Specifically, the lack of an independent external

cohort for validating the optimal cutoff (6.790) and prognostic

performance limits the immediate clinical translatability of the

findings. Future studies should prioritize multi-institutional

collaboration to establish population-adjusted thresholds. Third,

the exclusive reliance on single-timepoint preoperative

measurements precluded assessment of dynamic changes in CALLY

values, suggesting that prospective studies incorporating serial

measurements would provide more comprehensive insights into its

clinical utility. Fourth, the absence of key prognostic confounders

in the analysis, including molecular subtypes (RAS/BRAF mutation

status), microsatellite instability status, perioperative

nutritional support and postoperative complications, may have

influenced survival outcomes independent of the CALLY index.

Finally, the analysis did not incorporate circulating tumor DNA or

other molecular residual disease markers, which could potentially

miss early micrometastatic signals.

The present study establishes the CALLY index as a

simple yet effective prognostic marker for patients with stage

I–III CRC after radical resection. Key findings demonstrate its

ability to: i) Independently predict RFS and OS rates; ii) stratify

patients by tumor aggressiveness; and iii) complement traditional

TNM staging. As a composite of routine blood parameters, this

multifaceted marker, integrating inflammatory, nutritional and

immune indicators, enhances clinical relevance while offering

cost-effectiveness and immediate clinical implementability.

Although further validation is warranted, the CALLY index may guide

personalized management by identifying high-risk patients requiring

intensified surveillance, ultimately optimizing CRC therapeutic

decisions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL and SZ were responsible for the study

conceptualization and methodology. JL and XH were responsible for

visualization, validation, investigation and data curation. JL

provided resources and wrote the original draft manuscript. SZ

helped to review and edit the manuscript, and supervised the study.

JL, XH and SZ were responsible for project administration. JL and

SZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics

Committee at The Jingdezhen First People's Hospital (Jingdezhen,

China; approval no. jdzyykt202514). The requirement for informed

consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and

data anonymization.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rezazadeh M, Agah S, Kamyabi A, Akbari A,

Ghamkhari Pisheh R, Eshraghi A, Babakhani A, Ahmadi A, Paseban M,

Heidari P, et al: Effect of diabetes mellitus type 2 and

sulfonylurea on colorectal cancer development: A Case-control

study. BMC Gastroenterol. 24:3822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mozooni Z, Golestani N, Bahadorizadeh L,

Yarmohammadi R, Jabalameli M and Amiri BS: The role of

interferon-gamma and its receptors in gastrointestinal cancers.

Pathol Res Pract. 248:1546362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global patterns and trends in

colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 66:683–691. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang Y, Han Z, Li X, Huang A, Shi J and Gu

J: Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in China.

Chin J Cancer Res. 32:729–741. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Benson AB III, Venook AP, Cederquist L,

Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC,

Fichera A, et al: Colon cancer, version 1.2017, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

15:370–398. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Burzinskis E, Janulaityte I, Jievaltas M,

Skaudickas D, Burzinskiene G, Dainius E, Naudziunas A and

Vitkauskiene A: Inflammatory markers in prostate cancer: Potential

roles in risk stratification and immune profiling. J Immunotoxicol.

22:24977762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tan J, Wu Z, Liu Y, Wang W, Qin W, Pan G,

Xiong Y, Ma J, Zhao J, Zhou H, et al: Transcriptional profiling

reveals H.pylori-associated genes induced inflammatory cell

infiltration and chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Front Immunol.

16:15925582025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yuan S, Zhu L, Chen X and Lin Q: Huanglian

Jiedu Tang regulates the inflammatory microenvironment to alleviate

the progression of breast cancer by inhibiting the RhoA/ROCK

pathway. Tissue Cell. 95:1028502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim JY, Jung EJ, Kim JM, Lee HS, Kwag SJ,

Park JH, Park T, Jeong SH, Jeong CY and Ju YT: Dynamic changes of

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

predicts breast cancer prognosis. BMC Cancer. 20:12062020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Huang XZ, Chen WJ, Zhang X, Wu CC, Zhang

CY, Sun SS and Wu J: An Elevated Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio

predicts poor prognosis and clinicopathological characteristics in

patients with colorectal cancer: A Meta-analysis. Dis Markers.

2017:10531252017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nøst TH, Alcala K, Urbarova I, Byrne KS,

Guida F, Sandanger TM and Johansson M: Systemic inflammation

markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur J Epidemiol.

36:841–848. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li X, Wu Q, Kong Y and Lu C: Mild

cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes is associated with

fibrinogen-to-albumin ratios. PeerJ. 11:e158262023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu X, Sun T, Zhang X, Wang W, Ji Y and

Jing J: The predicting role of albumin to derived

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for the prognosis of esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma patients aged 60 years and above. BMC

Cancer. 25:6522025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Poenariu IS, Boldeanu L, Ungureanu BS,

Caragea DC, Cristea OM, Pădureanu V, Siloși I, Ungureanu AM, Statie

RC, Ciobanu AE, et al: Interrelation of Hypoxia-inducible factor-1

Alpha (HIF-1 α) and the ratio between the mean corpuscular

Volume/Lymphocytes (MCVL) and the cumulative inflammatory index

(IIC) in ulcerative colitis. Biomedicines. 11:31372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang J, Gong L, Zhu X, Wang Y and Li C:

Mediation of systemic inflammation response index in the

association of healthy eating Index-2020 in patientis with

periodontitis. Oral Health Prev Dent. 23:225–232. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang Y, Lyu J, Jia H, Liang L, Xiao L, Liu

Y, Liu X, Li K, Chen T, Zhang R, et al: Clinical utility of the

systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting survival in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after radical radiotherapy.

Future Oncol. 17:2647–2657. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li H, Sun W, Fu S, Wang J, Jin B, Zhang S,

Liu Y, Zhang Q and Wang H: Prognostic value of the preoperative

prognostic nutritional and systemic immunoinflammatory indexes in

patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 25:4032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Șerban RE, Popescu DM, Boldeanu MV,

Florescu DN, Șerbănescu MS, Șandru V, Panaitescu-Damian A,

Forțofoiu D, Șerban RC, Gherghina FL and Vere CC: The diagnostic

and prognostic role of inflammatory markers, including the new

cumulative inflammatory index (IIC) and mean corpuscular

volume/lymphocyte (MCVL), in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cancers

(Basel). 17:9902025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xie H, Wei L, Liu M, Liang Y, Yuan G, Gao

S, Wang Q, Lin X, Tang S and Gan J: Prognostic significance of

preoperative prognostic immune and nutritional index in patients

with stage I–III colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 22:13162022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dong J, Jiang W, Zhang W, Guo T, Yang Y,

Jiang X, Zheng L and Du T: Exploring the J-shaped relationship

between HALP score and mortality in cancer patients: A NHANES

1999–2018 cohort study. Front Oncol. 14:13886102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li K, Zeng X, Zhang Z, Wang K, Pan Y, Wu

Z, Chen Y and Zhao Z: Pan-immune-inflammatory values predict

survival in patients after radical surgery for non-metastatic

colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. Oncol Lett. 29:1972025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Iida H, Tani M, Komeda K, Nomi T,

Matsushima H, Tanaka S, Ueno M, Nakai T, Maehira H, Mori H, et al:

Superiority of CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) as a

non-invasive prognostic biomarker after hepatectomy for

hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 24:101–115. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nakashima K, Haruki K, Kamada T, Takahashi

J, Tsunematsu M, Ohdaira H, Furukawa K, Suzuki Y and Ikegami T:

Usefulness of the C-reactive protein (CRP)-Albumin-lymphocyte

(CALLY) index as a prognostic indicator for patients with gastric

cancer. Am Surg. 90:2703–2709. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Fukushima N, Masuda T, Tsuboi K, Takahashi

K, Yuda M, Fujisaki M, Ikegami T, Yano F and Eto K: Prognostic

significance of the preoperative C-reactive

protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index on outcomes after

gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Today. 54:943–952. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Toda M, Musha H, Suzuki T, Nomura T and

Motoi F: Impact of C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte index as a

prognostic marker for the patients with undergoing gastric cancer

surgery. Front Nutr. 12:15560622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Amin MB, Edge SB and Greene FL: AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. New York: Springer; 2016

|

|

27

|

Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida

D, Yu GY, Vallabhapurapu S, Scheller J, Rose-John S, Cheroutre H,

Eckmann L and Karin M: IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of

intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated

cancer. Cancer Cell. 15:103–113. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan

V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI,

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, et al: Understanding the tumor

immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med.

24:541–550. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y,

Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, et al:

Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and

patient prognosis. Gut. 65:1973–1980. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen WD, Zhang X, Zhang YP, Yue CB, Wang

YL, Pan HW, Zhang YL, Liu H and Zhang Y: Fusobacterium

nucleatum is a risk factor for metastatic colorectal cancer.

Curr Med Sci. 42:538–547. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tauriello DVF, Palomo-Ponce S, Stork D,

Berenguer-Llergo A, Badia-Ramentol J, Iglesias M, Sevillano M,

Ibiza S, Cañellas A, Hernando-Momblona X, et al: TGFβ drives immune

evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis.

Nature. 554:538–543. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang A, Wu Y, Cui J, Cai M, Xie Y, Zou J,

Alenzi M, Yang H, Huang P and Huang M: Assessment of

compartment-specific CD103-positive cells for prognosis prediction

of colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 74:2372025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hashimoto I, Tanabe M, Onuma S, Morita J,

Nagasawa S, Maezawa Y, Kanematsu K, Aoyama T, Yamada T, Yukawa N,

et al: Clinical impact of the C-reactive Protein-albumin-lymphocyte

index in Post-gastrectomy patients with gastric cancer. In Vivo.

38:911–916. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ and

Schreiber RD: Cancer immunoediting: From immunosurveillance to

tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 3:991–998. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Łuksza M, Sethna ZM, Rojas LA, Lihm J,

Bravi B, Elhanati Y, Soares K, Amisaki M and Dobrin A: Neoantigen

quality predicts immunoediting in survivors of pancreatic cancer.

Nature. 606:389–395. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Reina-Campos M, Heeg M, Kennewick K,

Mathews IT, Galletti G, Luna V, Nguyen Q, Huang H, Milner JJ, Hu

KH, et al: Metabolic programs of T cell tissue residency empower

tumour immunity. Nature. 621:179–187. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Furukawa S, Hiraki M, Kimura N, Sakai M,

Ikubo A and Samejima R: The potential of the C-reactive

protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index as a prognostic biomarker

in colorectal cancer. Cancer Diagn Progn. 5:370–377. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|