Introduction

Due to the continuous advancement of modern medical

technology, the survival of patients with cancer has been markedly

prolonged. However, this progress has also led to a corresponding

rise in the risk of developing other primary malignancies (1–3).

Multiple primary cancers (MPC) denote the diagnosis of ≥2 primary

malignant tumors in a patient, either simultaneously or

sequentially (4). The etiology of

MPC is complex and may be associated with numerous factors,

including patient genetics, immune dysregulation, exposure to

carcinogens, environmental factors, treatment modalities and

increased disease surveillance (5–10). In

clinical practice, the diagnosis and treatment of MPC present

numerous challenges (4,11). Its symptoms and imaging features

closely mimic those of metastatic cancer, often leading to

misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis, which may delay the optimal

timing for treatment. Furthermore, the treatment of MPC lacks

standardized guidelines, and clinical decision-making requires a

comprehensive consideration of several factors, including the

physical condition of the patient, type of tumor pathology, tumor

staging and prior treatment history, further complicating clinical

decision-making (4,5,12).

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a prevalent

malignancy localized to the head and neck region. It is

characterized by a distinct geographical distribution, with notably

higher incidence rates in Southeast Asia and Southern China

compared with other regions worldwide (13,14).

Despite advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic technologies,

NPC remains a marked public health burden due to its high incidence

and mortality rates (15). Notably,

the incidence of MPC among patients with NPC is relatively high

(1.9–8.7%) (16–19), which may be attributed to the unique

biological behavior of NPC and its treatment modalities

(radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy), both of which may potentially

induce second primary cancers (17,20).

When patients with NPC develop MPC, clinical management and

prognosis become even more complex. Therefore, a deeper

understanding of the clinical characteristics and survival outcomes

of patients with NPC-related MPC (NPC-MPC) is crucial for

optimizing treatment strategies and improving prognosis.

Although previous studies have explored the

incidence and outcomes of MPC among specific groups of cancer

survivors (5,18,21,22),

certain reports have indicated that patients with metachronous MPC

(mMPC) have an improved prognosis compared with patients with

synchronous MPC (sMPC) (4,23–26).

The number of studies specifically focused on NPC-MPC cases remains

limited and it is unclear whether the previously reported survival

advantage of mMPC compared with sMPC is also applicable to patients

with NPC in association with other primary tumors. Additionally,

there is no consensus on the clinical characteristics, prognosis

and prognostic factors of this complex and unique patient

population. Therefore, identifying prognostic factors in patients

with NPC-MPC is of critical clinical importance. These factors will

not only facilitate accurate patient assessment and personalized

treatment planning but also provide evidence-based guidance for

clinicians to optimize therapeutic strategies. For example,

identifying high-risk patient groups may help guide early detection

and intervention, with the potential for improved patient

prognosis.

Given the current knowledge gaps and clinical needs

in the field of NPC-MPC, the present retrospective study aimed to

analyze the clinical data of 306 patients with NPC-MPC, with a

focus on comparing the clinical characteristics, treatment

responses and survival outcomes between patients with sMPC and

mMPC. Survival and multivariate regression analysis were employed

to identify key prognostic factors, with the aim to provide a

theoretical foundation for the clinical management of NPC-MPC

cases, optimize treatment strategies and ultimately improve patient

prognosis and quality of life.

Materials and methods

Clinical subjects

The clinical data of patients with NPC

[International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code C11

(27)] who were admitted to the

First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning,

China) from January 2012 to December 2023 were retrospectively

collected by accessing patient medical records whilst following the

appropriate research criteria and guidelines. The clinical data of

patients who had been initially diagnosed with NPC-MPC were then

extracted.

The diagnosis of MPC was based on the criteria

established by Warren and Gates in 1932 (28). The inclusion criteria were as

follows (29): i) Each tumor must

be pathologically confirmed as malignant; ii) each tumor must

possess distinct pathological characteristics; iii) tumors should

be located in different organs or, if in the same organ, be

non-contiguous; and iv) one of the tumors must be pathologically

diagnosed as NPC. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria were as

follows: i) No pathological evidence; ii) recurrence or metastasis

of the primary cancer; and iii) incomplete clinical data. Based on

the time interval between the onset of the two primary tumors,

patients were further categorized into two groups: i) sMPC group,

defined as those occurring simultaneously or within 6 months of

each other; and ii) mMPC group, defined as those with a diagnostic

interval of >6 months (30).

Based on the cancer onset sequence, the NPC first (NCF) and the

other cancer first (OCF) groups were defined. In NCF MPCs, NPC was

the first-occurring tumor, and in OCF MPCs, other malignancies

occurred before NPC. For sMPCs, classification relied on the

earliest documented evidence (pathological confirmation,

radiological suspicion or symptom onset). For cases with identical

diagnostic timestamps (truly simultaneous presentations),

precedence was assigned to the malignancy demonstrating a more

advanced tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage. Persisting diagnostic

uncertainties were resolved by symptom chronology analysis or

multidisciplinary tumor board consensus.

The present retrospective study was reviewed and

approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. As it was a retrospective

study, the Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed

patient consent.

Clinical data collection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to

the patient cohort and 35 sMPC and 271 mMPC cases were selected for

retrospective analysis. The clinical characteristics of patients

assessed included age, sex, marital status, smoking and alcohol

consumption status, family history of cancer, histological subtypes

of cancer, TNM stage, treatment details and survival time. Marital

status was classified as either married or unmarried. Based on the

World Health Organization (WHO) classification, the histological

subtypes of NPC included keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (WHO

I subtype), differentiated non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

(WHO II subtype) and undifferentiated non-keratinizing squamous

cell carcinoma (WHO III subtype) (31). Smoking status was classified as

never smoker, current or ex-smoker or heavy smoker (≥20 pack-years)

(32). Alcohol consumption status

was categorized into never drinker, current or ex-drinker and heavy

drinker (≥30 g/day) (33). A total

of two experienced pathologists independently reviewed all

pathology slides to confirm the diagnosis. Discrepancies were

resolved by achieving consensus. To ensure quality control,

diagnostic reports were cross validated with institutional cancer

registry data.

Treatment

The clinical staging of NPC was determined according

to the 2017 Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on

Cancer staging system (34), where

the TNM stage was defined as early-stage (stage I–II) or

advanced-stage (stage III–IV). In accordance with the guidelines of

the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for head and neck cancer

(35), a standardized treatment

plan was established according to the TNM stage of the patient.

Endpoints and follow-up

All enrolled patients were followed up using

outpatient reviews, inpatient examinations and telephone calls

until the death of the patient or until March 2024. Overall

survival (OS) was calculated from the time of diagnosis of the

first cancer to the death of the patient or last follow-up.

Patients lost to follow-up were treated as censored cases, with

their survival time calculated up to the date of the last confirmed

contact (such as their final hospital visit or telephone contact),

meaning that their observation was ended at that point without an

event being recorded. All surviving patients without adverse events

were censored at the study end date (March 2024).

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used for categorical

variables when all expected cell counts were >5 or when ≤20% of

cells had expected counts of ≤5; otherwise, Fisher's exact test was

applied for 2×2 tables, and the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test

(Monte Carlo method, 100,000 replicates, two-sided) was used for

larger contingency tables. An unpaired (independent samples) t-test

was used for continuous variables. OS was estimated using the

Kaplan-Meier method, and survival outcomes between the two groups

were compared via the log-rank test. To explore the factors

influencing prognosis, multivariate Cox regression analysis was

performed. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using

Schoenfeld residuals, and all covariates satisfied this assumption.

Multicollinearity among covariates was evaluated using the variance

inflation factor (VIF), where all VIF values were observed to be

below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, indicating no

significant collinearity. SPSS (version 27.0; IBM Corp.) and R

Statistical Software (version 4.2.2; http://www.r-project.org) were used for all

statistical analyses. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

with sMPC and mMPC

A total of 306 patients diagnosed with MPC-involving

NPC were included in the present study (Table I). Among these, 35 patients (11.4%)

had sMPC, whilst 271 patients (88.6%) had mMPC. The proportion of

patients with other cancer as the first primary cancer (OCF group)

was significantly higher in the sMPC group (37.1%) compared with in

the mMPC group (11.8%), with the difference between groups being

statistically significant (P<0.001). Conversely, the proportion

of NPC as the first primary cancer (NCF) was notably higher in the

mMPC group (88.2%) than in the sMPC group (62.9%). The mean age at

diagnosis of MPC was significantly higher in the sMPC group

(53.3±12.4 years) compared with in the mMPC group (46.2±11.9 years;

P=0.001). No significant differences were observed between groups

in terms of sex distribution (P=0.194), family history of cancer

(P=0.100) or marital status (P=0.704). However, smoking history

differed significantly, with a higher proportion of heavy smokers

in the sMPC group (11.4%) compared with in the mMPC group (3.9%;

P=0.042).

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of 306

patients with multiple primary cancers. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of 306

patients with multiple primary cancers.

| Variable | Total (n=306) | sMPC group

(n=35) | mMPC group

(n=271) | P-value | Test statistic |

|---|

| Order of

occurrence |

|

|

|

<0.001a | - |

|

OCF | 45 (14.7) | 13 (37.1) | 32 (11.8) |

|

|

|

NCF | 261 (85.3) | 22 (62.9) | 239 (88.2) |

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.194 | 1.686 |

|

Male | 216 (70.6) | 28 (80.0) | 188 (69.4) |

|

|

|

Female | 90 (29.4) | 7 (20.0) | 83 (30.6) |

|

|

| Age at MPC

diagnosis, years | 47.0±12.2 | 53.3±12.4 | 46.2±11.9 | 0.001 | 10.822 |

| Family history of

cancer |

|

|

| 0.100a | - |

| No | 267 (87.3) | 27 (77.1) | 240 (88.6) |

|

|

|

Yes | 39 (12.7) | 8 (22.9) | 31 (11.4) |

|

|

| Marital status |

|

|

| 0.704a | - |

|

Married | 291 (95.1) | 34 (97.1) | 257 (94.8) |

|

|

|

Unmarried | 15 (4.9) | 1 (2.9) | 14 (5.2) |

|

|

| Smoking status |

|

|

| 0.042a | - |

| Never

smoker | 204 (66.7) | 19 (54.3) | 185 (68.3) |

|

|

| Current

or ex-smoker | 90 (29.4) | 12 (34.3) | 78 (28.8) |

|

|

| Heavy

smokerb | 12 (3.9) | 4 (11.4) | 8 (3.0) |

|

|

| Alcohol status |

|

|

| 0.061a | - |

| Never

drinker | 231 (75.5) | 21 (60.0) | 210 (77.5) |

|

|

| Current

or ex-drinker | 49 (16.0) | 9 (25.7) | 40 (14.8) |

|

|

| Heavy

drinkerc | 26 (8.5) | 5 (14.3) | 21 (7.7) |

|

|

| TNM stage - first

cancer |

|

|

| 0.002a | - |

|

I/II | 129 (42.2) | 6 (17.1) | 123 (45.4) |

|

|

|

III/IV | 173 (56.5) | 28 (80.0) | 145 (53.5) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 4 (1.3) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (1.1) |

|

|

| TNM stage - second

cancer |

|

|

| 0.587a | - |

|

I/II | 120 (39.2) | 14 (40.0) | 106 (39.1) |

|

|

|

III/IV | 181 (59.2) | 20 (57.1) | 161 (59.4) |

|

|

|

Unknown | 5 (1.6) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (1.5) |

|

|

| Histological

type |

|

|

| 0.492a | - |

| I | 7 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.6) |

|

|

| II | 29 (9.5) | 5 (14.3) | 24 (8.9) |

|

|

|

III | 270 (88.2) | 30 (85.7) | 240 (88.6) |

|

|

| Surgery - first

cancer |

|

|

| 0.003a | - |

| No | 270 (88.2) | 25 (71.4) | 245 (90.4) |

|

|

|

Yes | 36 (11.8) | 10 (28.6) | 26 (9.6) |

|

|

| Radiotherapy -

first cancer |

|

|

|

<0.001a | - |

| No | 39 (12.7) | 14 (40.0) | 25 (9.2) |

|

|

|

Yes | 267 (87.3) | 21 (60.0) | 246 (90.8) |

|

|

| Chemotherapy -

first cancer |

|

|

| 0.819 | 0.052 |

| No | 117 (38.2) | 14 (40.0) | 103 (38.0) |

|

|

|

Yes | 189 (61.8) | 21 (60.0) | 168 (62.0) |

|

|

| Surgery - second

cancer |

|

|

| <0.001 | 11.308 |

| No | 129 (42.2) | 24 (68.6) | 105 (38.7) |

|

|

|

Yes | 177 (57.8) | 11 (31.4) | 166 (61.3) |

|

|

| Radiotherapy -

second cancer |

|

|

| 0.002 | 9.993 |

| No | 232 (75.8) | 19 (54.3) | 213 (78.6) |

|

|

|

Yes | 74 (24.2) | 16 (45.7) | 58 (21.4) |

|

|

| Chemotherapy -

second cancer |

|

|

| 0.116 | 2.473 |

| No | 186 (60.8) | 17 (48.6) | 169 (62.4) |

|

|

|

Yes | 120 (39.2) | 18 (51.4) | 102 (37.6) |

|

|

| Survival state |

|

|

| 0.047 | 3.942 |

|

Survived | 119 (38.9) | 19 (54.3) | 100 (36.9) |

|

|

|

Dead | 187 (61.1) | 16 (45.7) | 171 (63.1) |

|

|

| Median survival

time of first cancer, months | 155.2

(137–172.5) | 41.3

(37.7–44.9) | 160.3

(139.0–181.6) | <0.001 | 77.794 |

| Median survival

time of second cancer, months | 32.0

(26.3–37.7) | 40.8

(29.0–52.7) | 30.5

(24.2–36.8) | 0.302 | 1.065 |

Patients in the sMPC group had a significantly

higher proportion of advanced-stage first cancers (III/IV) compared

with in the mMPC group (80.0 vs. 53.5%; P=0.002). No significant

differences were observed in the TNM stage of the second primary

cancer (P=0.587). Most patients had histological type III cancer

(88.2%), with no significant difference between the sMPC and mMPC

groups (P=0.492) (Table I).

Age at occurrence of MPCs in patients

with NPC

Patients with sMPC exhibited distinct age patterns

at the time of cancer occurrence. The age at first cancer diagnosis

was significantly higher in the sMPC group (53.3±12.3 years)

compared with in the mMPC group (45.5±11.5 years; P<0.001).

Conversely, the age at second cancer diagnosis did not differ

significantly between the groups (53.3±12.4 vs. 54.5±10.6 years;

P=0.814) (Table II).

| Table II.Age at occurrence of multiple primary

cancers involving nasopharyngeal carcinoma. |

Table II.

Age at occurrence of multiple primary

cancers involving nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

|

|

|

| NCF group

(n=261) | OCF group

(n=45) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | sMPC group

(n=35) | mMPC group

(n=271) | sMPC | mMPC | sMPC | mMPC |

|---|

| Age at first cancer

diagnosis, years | 53.3±12.3 |

45.5±11.5a | 52.9±15.3 | 48.6±10.4 | 53.5±10.6 |

45.1±11.6b |

| Age at second

cancer diagnosis, years | 53.3±12.4 | 54.5±10.6 | 53.0±15.4 | 54.3±11.3 | 53.5±10.6 | 54.5±10.5 |

When stratified by NCF and OCF groups, the age at

first cancer diagnosis did not significantly differ within the NCF

group (52.9±15.3 years for sMPC group vs. 48.6±10.4 years for mMPC

group; P>0.05). However, in the OCF group, patients in the mMPC

group were significantly younger at first cancer diagnosis

(45.1±11.6 years) compared with those in the sMPC group (53.5±10.6

years; P=0.001). No significant differences were observed in the

age at second cancer diagnosis within either the NCF or OCF groups

(Table II).

Distribution of affected sites in

MPCs

The affected site distribution was based on the

anatomical locations involved in the first and second primary

cancers. Although both sites were reviewed for each patient, the

nasopharynx was excluded from this summary as all patients had NPC

as the index cancer. Statistical analysis revealed no significant

differences between patients with sMPC and mMPC (P=0.940; Table III) with reference to all major

affected sites of cancer (excluding the nasopharynx). The head and

neck region was the most frequently involved site (29.0%), followed

by the digestive (27.4%) and respiratory (24.4%) systems, as

detailed in Table III.

| Table III.Distribution of affected sites in

synchronous and metachronous multiple primary cancers. |

Table III.

Distribution of affected sites in

synchronous and metachronous multiple primary cancers.

| Affected site | Total (n=303) | sMPC group

(n=36) | mMPC group

(n=267) | P-value |

|---|

| Respiratory

system | 74 (24.4) | 10 (27.8) | 64 (24.0) | 0.940 |

| Digestive

system | 83 (27.4) | 10 (27.8) | 73 (27.3) |

|

| Urinary system | 22 (7.3) | 3 (8.3) | 19 (7.1) |

|

| Reproductive

system | 21 (6.9) | 1 (2.8) | 20 (7.5) |

|

| Head and neck | 88 (29.0) | 10 (27.8) | 78 (29.2) |

|

| Others | 15 (5.0) | 2 (5.6) | 13 (4.9) |

|

Visualization of survival time

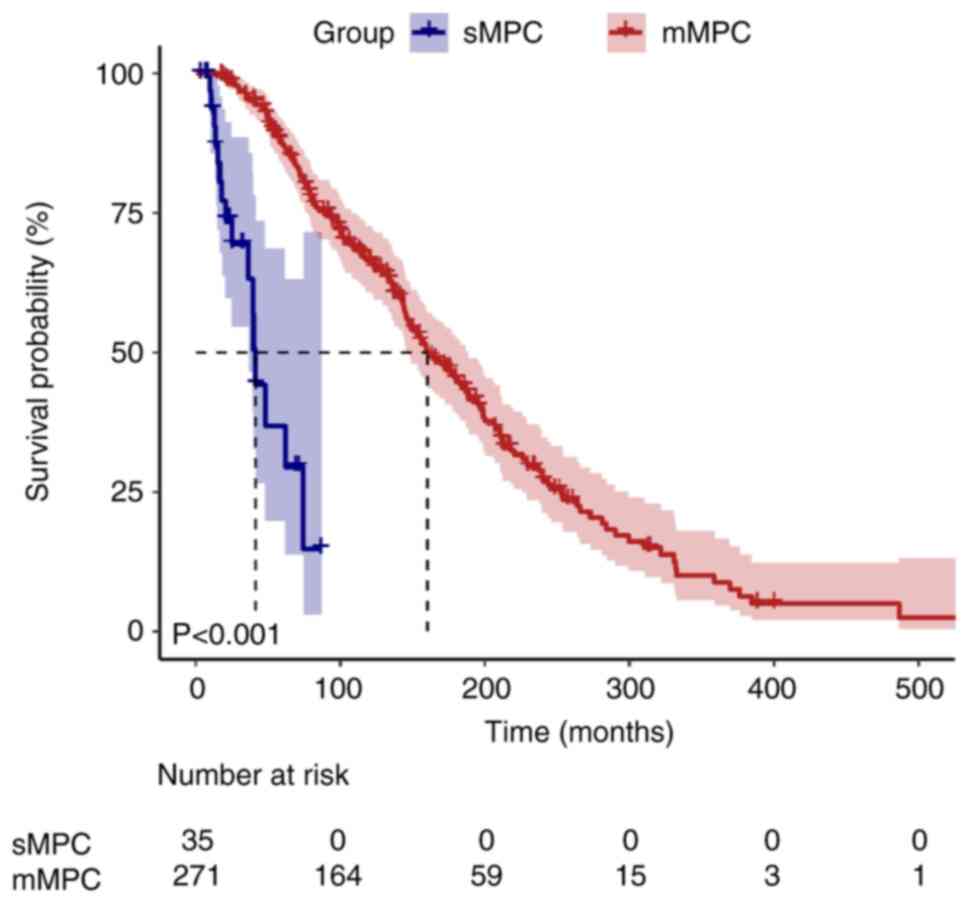

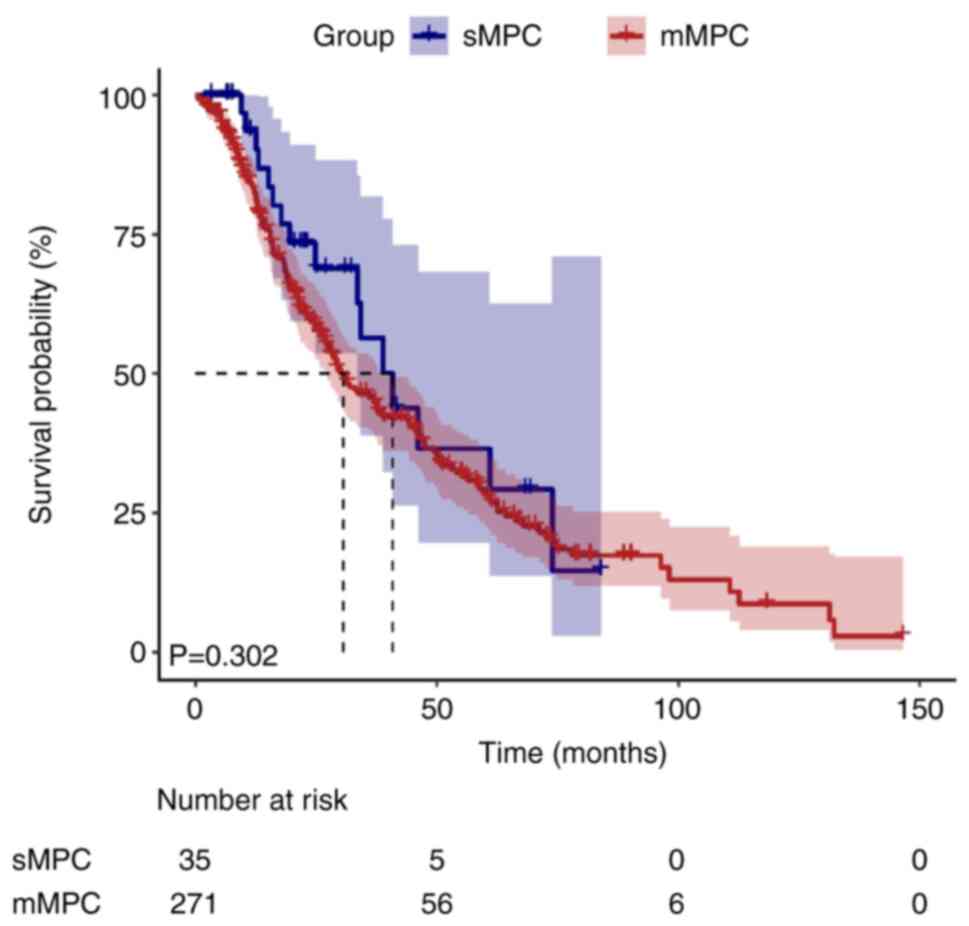

During the median follow-up duration of 155.2 months

[95% confidence interval (CI), 137.9–172.5], 10 patients (3.3%)

were lost to follow-up and censored as per the pre-defined

protocol. Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrated divergent

survival outcomes between the sMPC and mMPC groups (Figs. 1 and 2). The median survival time for the first

cancer was significantly shorter in the sMPC group (41.3 months;

95% CI, 37.7–44.9) compared with in the mMPC group (160.3 months;

95% CI, 139.0–181.6; log-rank P<0.001). By contrast, the median

survival time for the second cancer did not differ significantly

between the two groups (40.8 vs. 30.5 months; P=0.302).

Survival outcomes and prognostic

factors

Univariate analysis

Univariate analysis (Table IV) identified several factors that

were significantly associated with first cancer survival time.

Notably, an older age at first cancer diagnosis was strongly

associated with shorter survival, with each 1-year increase in age

corresponding to a 5% increase in the risk of death [hazard ratio

(HR), 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03–1.06; P<0.001]. Smoking history also

had a profound effect on survival, with heavy smokers exhibiting

significantly worse survival (HR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.37–5.38; P=0.004)

compared with current or ex-smokers. Radiotherapy for the first

cancer was significantly associated with improved survival (HR,

0.53; 95% CI, 0.34–0.83; P=0.011), suggesting its potential benefit

for these patients. Conversely, chemotherapy was significantly

associated with reduced survival, with patients receiving

chemotherapy showing significantly worse survival compared with

those who did not receive chemotherapy (HR, 2.01; 95% CI,

1.47–2.75; P<0.001). However, variables such as family history

of cancer and marital status did not show statistically significant

associations with survival (P>0.05).

| Table IV.Univariate analysis of prognostic

factors in multiple primary cancers. |

Table IV.

Univariate analysis of prognostic

factors in multiple primary cancers.

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Order of occurrence

(OCF vs. NCF) | 0.64

(0.42–1.01) | 0.054 |

| Sex (Male vs.

female) | 0.72

(0.52–0.99) | 0.036 |

| Age at first cancer

diagnosis (continuous variable) | 1.05

(1.03–1.06) | <0.001 |

| Family history of

cancer (Yes vs. no) | 1.05

(0.67–1.66) | 0.832 |

| Age at MPC

diagnosis (continuous variable) | 1.04

(1.02–1.05) | <0.001 |

| Age at second

cancer diagnosis (continuous variable) | 0.99

(0.97–1.00) | 0.050 |

| Marital status

(Unmarried vs. married) | 0.73

(0.30–1.78) | 0.470 |

| Smoking (reference,

Never) |

| 0.005 |

| Current

or ex-smoker | 1.51

(1.08–2.10) |

|

|

Heavya | 2.71

(1.37–5.38) |

|

| Alcohol (reference,

Never) |

| 0.054 |

| Current

or ex-drinker | 1.24

(0.82–1.89) |

|

|

Heavyb | 1.88

(1.14–3.09) |

|

| First cancer

affected site (reference, Nasopharynx) |

| 0.292 |

|

Respiratory system | 2.77

(0.68–11.26) |

|

|

Digestive system | 1.98

(1.07–3.66) |

|

| Urinary

system | 1.22

(0.39–3.83) |

|

|

Reproductive system | 1.27

(0.52–3.1) |

|

|

Others | 1.61

(0.59–4.36) |

|

| Secondary cancer

site (reference, Nasopharynx) |

| 0.455 |

|

Respiratory system | 1.01

(0.63–1.63) |

|

|

Digestive system | 1.01

(0.63–1.60) |

|

| Urinary

system | 0.82

(0.36–1.86) |

|

|

Reproductive system | 0.58

(0.27–1.27) |

|

| Head

and neck system | 0.35

(0.10–1.14) |

|

|

Others | 0.76

(0.49–1.19) |

|

| TNM stage - first

cancer (reference, I/II) |

| <0.001 |

|

III/IV | 4.54

(3.21–6.42) |

|

|

Unknown | 3.58

(1.11–11.56) |

|

| TNM stage - second

cancer (reference, I/II) |

| 0.009 |

|

III/IV | 1.62

(1.18–2.22) |

|

|

Unknown | 1.28

(0.46–3.56) |

|

| Histology type

(reference, I) |

| 0.494 |

| II | 0.72

(0.27–1.92) |

|

|

III | 0.61

(0.25–1.49) |

|

| Surgery - first

cancer (Yes vs. no) | 1.42

(0.88–2.29) | 0.174 |

| Radiotherapy -

first cancer (Yes vs. no) | 0.53

(0.34–0.83) | 0.011 |

| Chemotherapy -

first cancer (Yes vs. no) | 2.01

(1.47–2.75) | <0.001 |

| Surgery - second

cancer (Yes vs. no) | 0.47

(0.35–0.64) | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy -

second cancer (Yes vs. no) | 1.31

(0.93–1.84) | 0.131 |

| Chemotherapy -

second cancer (Yes vs. no) | 1.55

(1.15–2.10) | 0.005 |

Multivariate analysis

After adjusting for confounding factors,

multivariate survival analysis (Table

V) revealed that mMPC was significantly associated with

improved survival compared with sMPC (adjusted HR, 0.21; 95% CI,

0.11–0.40; P<0.001). Moreover, age at first cancer diagnosis was

identified as an independent predictor of survival (adjusted HR,

1.04; 95% CI, 1.02–1.05; P<0.001). By contrast, advanced TNM

stage (stage III/IV vs. I/II) was a significant independent

predictor of poor survival (adjusted HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.84–4.26;

P<0.001). Notably, radiotherapy for the first cancer

demonstrated a protective effect (adjusted HR, 0.55; 95% CI,

0.31–0.98; P=0.042), suggesting that patients who received

radiotherapy may have had improved survival outcomes. Furthermore,

chemotherapy for the first primary cancer revealed a significant

univariate association with a worse survival (HR, 2.01; 95% CI,

1.47–2.75; P<0.001; Table IV);

however, this significance was attenuated in multivariate models

(adjusted HR, 1.12; P=0.549; Table

V). A similar pattern was observed for second primary cancer

chemotherapy, where univariate analysis demonstrated a significant

association (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.15–2.10; P=0.005; Table IV) that was diminished in

multivariate analysis (adjusted HR, 1.24; P=0.200; Table V).

| Table V.Multivariate analysis of prognostic

factors in multiple primary cancers. |

Table V.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic

factors in multiple primary cancers.

| Variable | Crude HR (95%

CI) | Crude P-value | Adjusted HR (95%

CI) | Adjusted

P-value |

|---|

| MPC type (mMPC vs.

sMPC) | 0.11

(0.06–0.20) | <0.001 | 0.21

(0.11–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male vs.

female) | 0.72

(0.52–0.99) | 0.036 | 0.89

(0.62–1.3) | 0.553 |

| Age at first cancer

diagnosis (continuous variable, per year increase) | 1.05

(1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.04

(1.02–1.05) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status

(Current or ex-smoker vs. never smoked) | 1.51

(1.08–2.10) | 0.015 | 0.98

(0.68–1.43) | 0.927 |

| Smoking status

(Heavy smokera vs.

never smoked) | 2.71

(1.37–5.38) | 0.004 | 1.32

(0.64–2.71) | 0.458 |

| TNM stage of first

cancer (III/IV vs. I/II) | 4.54

(3.20–6.42) | <0.001 | 2.8

(1.84–4.26) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage of first

cancer (unknown vs. I/II) | 3.58

(1.11–11.57) | 0.033 | 0.58

(0.16–2.12) | 0.408 |

| TNM stage of second

cancer (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.62

(1.18–2.22) | 0.003 | 1.81

(1.24–2.63) | 0.002 |

| TNM stage of second

cancer (unknown vs. I/II) | 1.28

(0.46–3.56) | 0.631 | 1.47

(0.50–4.28) | 0.480 |

| Radiotherapy for

first cancer (Yes vs. no) | 0.53

(0.34–0.83) | 0.011 | 0.55

(0.31–0.98) | 0.042 |

| Chemotherapy for

first cancer (Yes vs. no) | 2.01

(1.47–2.75) | <0.001 | 1.12

(0.77–1.63) | 0.549 |

| Surgery for second

cancer (Yes vs. no) | 0.47

(0.35–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.82

(0.57–1.20) | 0.311 |

| Chemotherapy for

second cancer (Yes vs. no) | 1.55

(1.15–2.10) | 0.005 | 1.24

(0.89–1.72) | 0.200 |

Discussion

The current retrospective cohort analysis delineated

distinct clinicopathological patterns and survival trajectories

between the sMPC and mMPC groups of MPCs in patients with NPC. The

following principal findings emerged: i) Patients with sMPC

exhibited unique demographic profiles characterized by older age,

heavier smoking burden and advanced-stage first cancers; and ii)

synchronicity independently predicted survival outcomes, with the

sMPC group demonstrating a 4.8-fold increased mortality risk

compared with the mMPC group. The significant differences in

clinical characteristics observed between the two groups have

important implications for clinical management.

The demographic divergence observed between groups

suggest distinct carcinogenic mechanisms. The older age of the sMPC

cohort at initial diagnosis and its elevated heavy smoking

prevalence aligned with cumulative mutagenic exposure models.

Notably, 37.1% of patients with sMPC developed OCF malignancies as

first primaries compared with 11.8% in the mMPC group. This is

similar to the results of previous studies (36,37)

and implies potentially shared etiological factors such as aging,

genetic mutations and tobacco-related field cancerization that

simultaneously increase the risk of multiple cancers or exposure to

a unique set of carcinogens that trigger the development of

multiple primary tumors at the same time (7,38–40).

The older age at diagnosis in the sMPC group may be due to the

cumulative exposure to carcinogens over a longer period. This is

consistent with the multistep carcinogenesis process theory, where

genetic mutations and cellular damage accumulates over time, often

due to prolonged exposure to carcinogens, gradually resulting in an

association with cancer development (5,36,41,42).

The head and neck region, and the digestive and

respiratory systems, were the most frequently affected sites in the

secondary malignancies, which is generally consistent with previous

research findings. The presence of multiple synchronous tumors in

the head and neck area and the upper aerodigestive tract has been

well established (16,17,43)

and may be explained by the concept of ‘field cancerization’

(44). This trend may result from

the growing incidence of thyroid, lung and digestive system

malignancies (45–47), and the observation highlights the

need for enhanced surveillance for malignancies of the head and

neck and upper aerodigestive tract to be integrated throughout the

treatment and management process of NPC. Such surveillance can

facilitate the early detection of malignancies and help formulate

personalized treatment strategies for patients with NPC exhibiting

MPC.

Moreover, the survival analysis revealed that

patients with mMPC had an improved prognosis compared with those

with sMPC (median overall survival, 160.3 vs. 41.3 months;

P<0.001). This survival disparity may reflect divergent

biological pathways. In the sMPC cohort, advanced age (53.3±12.4

vs. 46.2±11.9 years; P=0.001) and heavy smoking prevalence (11.4

vs. 3.0%; P=0.042) may indicate a cumulative mutagenic exposure

potentially driving synchronous carcinogenesis through field

cancerization (44). This

mechanism, consistent with previous findings, is associated with

synchronous tumors in related regions such as the head and neck,

lung and colorectal areas, often exhibiting more aggressive

behavior (23–25). Additionally, patients with sMPC have

a significantly higher proportion of advanced-stage first cancers

(80.0 vs. 53.5%; P=0.002), aligning with findings that synchronous

colorectal cancer tends to present with advanced TNM stages and

larger tumor diameters. This higher intrinsic tumor burden

inherently limits therapeutic options and effectiveness (25). Conversely, patients with mMPC

benefit from longer inter-cancer intervals (>6 months): Tissue

repair reduces prior treatment toxicity (for example,

chemotherapy-related risk drops from a univariate HR value of 2.01

to an adjusted HR value of 1.12), which is consistent with the

finding that metachronous colorectal cancer has fewer complications

and improved tolerance due to sufficient inter-cancer intervals

(25). Over time, restored immune

competence and DNA repair capacity in patients with mMPC may

further lower the risk of aggressive tumor progression. Crucially,

regular monitoring enabled by the inter-cancer interval facilitates

early detection of second primary cancers, in line with the

conclusion that metachronous cancers are more likely to be

diagnosed at earlier, curable stages (4). Moreover, a reduced mutual influence

between tumors in mMPC facilitates radical treatments such as

radiotherapy, as observed in the 85% 5-year survival rate with

radiotherapy for metachronous head and neck cancers (23), mirrored by the significant benefit

of radiotherapy observed in the present study (adjusted HR, 0.55;

P=0.042). In summary, sMPC has a poor prognosis that is associated

with field cancerization-driven synchronous progression, a high

tumor burden and treatment limitations. By contrast, mMPC exhibits

survival advantages from inter-cancer interval-driven bodily

repair, early detection and access to radical treatments.

Results of the present multivariate analysis

demonstrated that mMPC is an independent survival predictor, whilst

radiotherapy was revealed to be associated with protective effects

despite the complexity of MPC. This underscores its indispensable

role in NPC management. The identification of independent

prognostic factors, such as mMPC, age at first cancer diagnosis,

TNM stage and radiotherapy for the first cancer provides valuable

guidance for clinicians to stratify patients and formulate

personalized treatment plans. This finding is consistent with

previous studies (16,48). The protective effect of radiotherapy

on patient survival is consistent with its established role in NPC

treatment. Conversely, chemotherapy was observed to be

significantly associated with worse survival in the univariate

analysis; however, this finding lost statistical significance in

the multivariate model. This discrepancy can be attributed to

confounding by indication. Specifically, patients receiving

chemotherapy were more likely to present with advanced-stage

disease, which is itself a strong predictor of poor prognosis. Once

the model was adjusted for TNM stage and other covariates, the

independent effect of chemotherapy diminished, suggesting that

chemotherapy use was a marker of disease severity rather than a

direct cause of worse outcomes.

Clinically, the aforementioned findings advocate for

tailored surveillance strategies. Universal TNM staging remains

critical for all patients given the persistent prognostic impact of

advanced-stage disease. For patients with sMPC who are

characterized by older age, a higher prevalence of advanced-stage

first cancers and heavy smoking, comprehensive baseline assessments

(such as whole-body PET-CT and endoscopy) are essential to avoid

missing synchronous second primary malignancies. Post-treatment

surveillance should be intensified for early detection of

subsequent primaries, alongside mandatory smoking cessation

interventions. For patients with mMPC, long-term surveillance

targeting the head and neck region and upper aerodigestive tract

should commence after NPC diagnosis. Treatment strategies require a

tiered optimization approach: Radiotherapy should be prioritized

for the first cancer given its independent association with patient

survival, whilst chemotherapy decisions warrant a cautious risk

assessment that accounts for age and TNM stage disparities in sMPC

whilst weighing cumulative treatment burdens in mMPC.

Although the present study provides valuable

insights into the survival outcomes of patients with NPC who have

MPC, there are several limitations to consider. The retrospective

nature of the study may have led to selection bias, potentially

affecting the accuracy and reliability of the data. Therefore,

further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Additionally, the focus of the study on a single cohort of patients

with NPC may limit the generalizability of the results to other

cancer types or populations. Future studies should explore the

molecular mechanisms underlying synchronous and metachronous cancer

development to inform treatment strategies.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the

significant clinical heterogeneity and survival disparities between

patients with NPC who also present with either sMPC or mMPC. Among

patients with mMPC, a younger age, early TNM stage and radiotherapy

for the first cancer are associated with improved survival

outcomes. By identifying key prognostic factors and their

implications for treatment, these findings can inform clinical

practice and guide future research aimed at improving the outcomes

for this complex patient population.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Guangxi Natural Science

Foundation Outstanding Youth Science Fund Project (grant no.

2024JJG140004); National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant

nos. 82272736, 81460460 and 81760542); Key Research and Development

Program of Guangxi Province, China (2018AB61001); Youth Science and

Technology Award of Guangxi Province, China (2023); The Research

Foundation of the Science and Technology Department of Guangxi

Province, China (grant nos. 2023GXNSFDA026009, 2016GXNSFAA380252

and 2014GXNSFBA118114); the Research Foundation of the Health

Department of Guangxi Province, China (grant no. S2018087); Guangxi

Medical University Training Program for Distinguished Young

Scholars (2017); Medical Excellence Award Funded by the Creative

Research Development Grant from the First Affiliated Hospital of

Guangxi Medical University (2016); Guangxi Medical High-level

Talents Training Program (2022); and the Central Government Guide

Local Science and technology Development Projects (grant no.

ZY18057006).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XH, YK, TW, ZM and MK contributed to the study

conception and design. Data management and accuracy verification

were handled by XH, YK, TW and ZM. XH and YK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. The statistical analysis,

interpretation of the results and writing of the first draft of the

manuscript were performed by XH. Oversight and critical manuscript

revisions were performed by MK. All authors commented on previous

versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in line with the

principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and

approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, China; approval

no. 2025-E0109). Due to the retrospective design, the committee

waived the requirement for informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wagle NS, Nogueira L, Devasia TP, Devasia

TP, Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Islami F, Jemal A, Alteri R, Ganz PA

and Siegel RL: Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2025.

CA Cancer J Clin. 75:308–340. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Choi E, Hua Y, Su CC, Wu JT, Neal JW,

Leung AN, Backhus LM, Haiman C, Le Marchand L, Liang SY, et al:

Racial and ethnic differences in second primary lung cancer risk

among lung cancer survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 8:pkae0722024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Freire MV, Thissen R, Martin M, Fasquelle

C, Helou L, Durkin K, Artesi M, Lumaka A, Leroi N, Segers K, et al:

Genetic evaluation of patients with multiple primary cancers. Oncol

Lett. 29:42024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tanjak P, Suktitipat B, Vorasan N,

Juengwiwattanakitti P, Thiengtrong B, Songjang C, Therasakvichya S,

Laiteerapong S and Chinswangwatanakul V: Risks and cancer

associations of metachronous and synchronous multiple primary

cancers: A 25-year retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 21:10452021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ge S, Wang B, Wang Z, He J and Ma X:

Common multiple primary cancers associated with breast and

gynecologic cancers and their risk factors, pathogenesis, treatment

and prognosis: A review. Front Oncol. 12:8404312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang BX, Brantley KD, Rosenberg SM,

Kirkner GJ, Collins LC, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Schapira L, Borges VF,

Warner E, et al: Second primary non-breast cancers in young breast

cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 207:587–597. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Trapani JA, Thia KY, Andrews M, Davis ID,

Gedye C, Parente P, Svobodova S, Chia J, Browne K, Campbell IG, et

al: Human perforin mutations and susceptibility to multiple primary

cancers. OncoImmunology. 2:e241852013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Aredo JV, Luo SJ, Gardner RM, Sanyal N,

Choi E, Hickey TP, Riley TL, Huang WY, Kurian AW, Leung AN, et al:

Tobacco smoking and risk of second primary lung cancer. J Thorac

Oncol. 16:968–979. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

De Vries S, Schaapveld M, Janus CPM,

Daniëls LA, Petersen EJ, van der Maazen RWM, Zijlstra JM, Beijert

M, Nijziel MR, Verschueren KMS, et al: Long-term cause-specific

mortality in hodgkin lymphoma patients. J Natl Cancer Inst.

113:760–769. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou B, Zang R, Song P, Zhang M, Bie F,

Bai G, Li Y, Huai Q, Han Y and Gao S: Association between

radiotherapy and risk of second primary malignancies in patients

with resectable lung cancer: A population-based study. J Transl

Med. 21:102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Division of Cancer Control and Population

Sciences Program Areas, . Long Term Survivorship. Definitions.

National Cancer Institute; 2020

|

|

12

|

Tian M, Shen J, Liu M, Chen XF, Wang TJ

and Sun YS: Prognostic factors and nomogram development for

survival in renal cell carcinoma patients with multiple primary

cancers: A retrospective study. Transl Androl Urol. 14:685–695.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun

Y and Ma J: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 394:64–80. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wu T, Miao W, Qukuerhan A, Alimu N, Feng

J, Wang C, Zhang H, Du H and Chen L: Global, regional, and national

burden of nasopharyngeal carcinoma from 1990 to 2021. Laryngoscope.

135:1409–1418. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang LL, Li GH, Li YY, Qi ZY, Lin AH and

Sun Y: Risk assessment of secondary primary malignancies in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A big-data intelligence platform-based

analysis of 6,377 long-term survivors from an endemic area treated

with intensity-modulated radiation therapy during 2003–2013. Cancer

Res Treat. 51:982–991. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chow JCH, Au KH, Mang OWK, Cheung KM and

Ngan RKC: Risk, pattern and survival impact of second primary

tumors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma following

definitive intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol.

15:48–55. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Svärd F, Alabi RO, Leivo I, Mäkitie AA and

Almangush A: The risk of second primary cancer after nasopharyngeal

cancer: A systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

280:4775–4781. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao C, Miao JJ, Hua YJ, Wang L, Han F, Lu

LX, Xiao WW, Wu HJ, Zhu MY, Huang SM, et al: Locoregional control

and mild late toxicity after reducing target volumes and radiation

doses in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal

carcinoma treated with induction chemotherapy (IC) followed by

concurrent chemoradiotherapy: 10-year results of a phase 2 study.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 104:836–844. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Scélo G, Boffetta P, Corbex M, Chia KS,

Hemminki K, Friis S, Pukkala E, Weiderpass E, McBride ML, Tracey E,

et al: Second primary cancers in patients with nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: A pooled analysis of 13 cancer registries. Cancer Causes

Control. 18:269–278. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Guzzinati S, Buja A, Grotto G, Zorzi M,

Manfredi M, Bovo E, Del Fiore P, Tropea S, Dall'Olmo L, Rossi CR,

et al: Synchronous and metachronous multiple primary cancers in

melanoma survivors: A gender perspective. Front Public Health.

11:11954582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang Y, Jiang Y, Bai Y and Xu H: Do cancer

survivors have an increased risk of developing subsequent cancer? A

population-based study. J Transl Med. 23:3552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bugter O, Van Iwaarden DLP, Dronkers EAC,

de Herdt MJ, Wieringa MH, Verduijn GM, Mureau MAM, Ten Hove I, van

Meerten E, Hardillo JA and Baatenburg de Jong RJ: Survival of

patients with head and neck cancer with metachronous multiple

primary tumors is surprisingly favorable. Head Neck. 41:1648–1655.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kang X, Zhang C, Zhou H, Zhang J, Yan W,

Zhong WZ and Chen KN: Multiple pulmonary resections for synchronous

and metachronous lung cancer at two Chinese centers. Ann Thorac

Surg. 109:856–863. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fan H, Wen R, Zhou L, Gao X, Lou Z, Hao L,

Meng R, Gong H, Yu G and Zhang W: Clinicopathological features and

prognosis of synchronous and metachronous colorectal cancer: A

retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 109:4073–4090. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tamura K, Fujimoto T, Shimizu T, Nagayoshi

K, Mizuuchi Y, Hisano K, Horioka K, Shindo K, Nakata K, Ohuchida K

and Nakamura M: Clinical features, surgical treatment strategy, and

feasibility of minimally invasive surgery for synchronous and

metachronous multiple colorectal cancers: A 14-year single-center

experience. Surg Endosc. 38:7139–7151. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

World Health Organization (WHO), .

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related

Health Problems. 10th Revision (ICD-10). WHO; Geneva: 2016,

https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/C11

|

|

28

|

Warren S and Gates O: Multiple primary

malignant tumors: A survey of the literature and a statistical

study. Am J Cancer. 16:1358–1414. 1932.

|

|

29

|

Working Group Report: International rules

for multiple primary cancers (ICD-0 third edition). Eur J Cancer

Prev. 14:307–308. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yang XB, Zhang LH, Xue JN, Wang YC, Yang

X, Zhang N, Liu D, Wang YY, Xun ZY, Li YR, et al: High incidence

combination of multiple primary malignant tumors of the digestive

system. World J Gastroenterol. 28:5982–5992. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Guo LF, Hong JG, Wang RJ, Chen GP and Wu

SG: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma survival by histology in endemic and

non-endemic areas. Ann Med. 56:24250662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Duncan MS, Freiberg MS, Greevy RA Jr,

Kundu S, Vasan RS and Tindle HA: Association of smoking cessation

with subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 322:642–650.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cho JH, Shin SY, Kim H, Kim M, Byeon K,

Jung M, Kang KW, Lee WS, Kim SW and Lip GYH: Smoking cessation and

incident cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open. 7:e24426392024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O'Sullivan B,

Brandwein MS, Ridge JA, Migliacci JC, Loomis AM and Shah JP: Head

and neck cancers-major changes in the American joint committee on

cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:122–137. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Adelstein D, Gillison ML, Pfister DG,

Spencer S, Adkins D, Brizel DM, Burtness B, Busse PM, Caudell JJ,

Cmelak AJ, et al: NCCN guidelines insights: Head and neck cancers,

version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 15:761–770. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li F, Zhong WZ, Niu FY, Zhao N, Yang JJ,

Yan HH and Wu YL: Multiple primary malignancies involving lung

cancer. BMC Cancer. 15:6962015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ventura L, Carbognani P, Gnetti L, Rossi

M, Tiseo M, Silini EM, Sverzellati N, Silva M, Succi M, Braggio C,

et al: Multiple primary malignancies involving lung cancer: A

single-center experience. Tumori. 107:196–203. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wynder EL, Mushinski MH and Spivak JC:

Tobacco and alcohol consumption in relation to the development of

multiple primary cancers. Cancer. 40 (4 Suppl):S1872–S1878. 1977.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Oeffinger KC, Baxi SS, Novetsky Friedman D

and Moskowitz CS: Solid tumor second primary neoplasms: Who is at

risk, what can we do? Semin Oncol. 40:676–689. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hung RJ, Baragatti M, Thomas D, McKay J,

Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Zaridze D, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, Fabianova

E, Mates D, et al: Inherited predisposition of lung cancer: A

hierarchical modeling approach to DNA repair and cell cycle control

pathways. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 16:2736–2744. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Amer M: Multiple neoplasms, single

primaries, and patient survival. Cancer Manag Res. 6:119–134. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liberale C, Soloperto D, Marchioni A,

Monzani D and Sacchetto L: Updates on larynx cancer: Risk factors

and oncogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:129132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Goggins WB, Yu IT, Tse LA, Leung SF, Tung

SY and Yu KS: Risk of second primary malignancies following

nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong. Cancer Causes Control.

21:1461–1466. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Slaughter DP, Southwick HW and Smejkal W:

Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium.

Clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 6:963–968.

1953. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME and

Edwards BK: Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer

analyses from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

(SEER) program. Oncologist. 12:20–37. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Watanabe S, Kodama T, Shimosato Y, Arimoto

H, Sugimura T, Suemasu K and Shiraishi M: Multiple primary cancers

in 5,456 autopsy cases in the National cancer center of Japan. J

Natl Cancer Inst. 72:1021–1027. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Boucai L, Zafereo M and Cabanillas ME:

Thyroid cancer: A review. JAMA. 331:425–435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang X, Wang Z, Chen Y, Lin Q, Chen H, Lin

Y, Lu L, Zheng P and Chen X: Impact of prior cancer on the overall

survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J

Otolaryngol. 43:1032352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|