Introduction

Cancer is a critical health issue characterized by

high rates of morbidity and mortality. Cancer is a major societal,

public-health and economic challenge in the 21st century,

accounting for ~1 in 6 deaths (16.8%) and nearly 1 in 4 deaths from

non-communicable diseases (NCD; 22.8%) worldwide. Cancer

contributes to 30.3% of premature NCD deaths among those aged 30–69

years and ranks among the three leading causes of death in this age

group in 177 of 183 countries (1).

Beyond being a key barrier to increasing life expectancy, cancer

incurs substantial societal and macroeconomic costs that vary by

cancer type, geography and sex (2).

Underscoring the disproportionate burden on women, an estimated one

million children became maternal orphans in 2020 due to a maternal

cancer death, nearly half attributable to breast or cervical cancer

(3). The extracellular matrix

(ECM), as a key component of the tumor stroma, notably influences

cancer progression by serving as both a physical scaffold and a

regulator of cell and tissue functions. Beyond merely transmitting

signals, the ECM also generates biochemical and biophysical cues

that activate cellular responses (4). The interaction between tumor cells and

the ECM is dynamic and reciprocal, leading to continuous reshaping

of the surrounding malignant tissue. Research indicates that tumors

can exploit ECM remodeling to establish a microenvironment

conducive to tumorigenesis and metastasis (5). In turn, cellular behaviors such as

adhesion, migration, angiogenesis and malignant transformation are

influenced by changes in the ECM (6,7).

Within this intricate relationship between the ECM and tumor cells,

collagens serve a pivotal role. As the primary component of the

ECM, collagens constitute ~30% of its structure, with 28 distinct

collagen types identified. These various collagens contribute to

the formation of the basal membrane and interstitial matrix,

creating tissue-specific ECM compositions (8). Alterations in collagen within the

tumor microenvironment generate biomechanical signals that are

detected by both tumor and stromal cells, initiating a series of

biological processes. A previous study has highlighted the abnormal

behaviors of collagens in cancer progression, including

degradation, remodeling, fragmentation, linearization and

fasciculation (9), demonstrating

the role of collagens in precancerous lesions and cancer

development. Understanding the mechanisms by which collagens

influence different stages of cancer progression has enhanced their

diagnostic and prognostic value while opening new avenues for

therapeutic target identification (10).

Several antioxidants, anti-inflammatory and

antimicrobial compounds targeting the synthesis and function of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory processes are

already available as anticancer agents. These compounds offer

notable advantages over traditional chemotherapeutic drugs by

precisely targeting cancerous processes while minimizing harm to

healthy cells (11). The Purple

Collagen complex (PCC) incorporates several bioactive compounds

known for their diverse health benefits, including inulin which is

a prebiotic fiber that promotes gut health by stimulating the

growth of beneficial intestinal bacteria (12). Another compound is the elderberry,

which is derived from Sambucus nigra, rich in flavonoids,

particularly anthocyanins, which exhibit antioxidant properties.

These compounds support immune function and have been traditionally

used to alleviate cold and flu symptoms (13). Another plant-based compound is the

black cumin extract sourced from Nigella sativa, which is

known for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial

effects, attributed to its active component, thymoquinone (14). Magnesium citrate and malate found in

PCC are highly bioavailable. Magnesium citrate is commonly used to

treat constipation and improve bone health, while magnesium malate

has been suggested to benefit individuals with fibromyalgia

(15). The eggshell membrane

contains naturally occurring glycosaminoglycans and proteins that

support joint health by reducing pain and stiffness associated with

joint disorders (16). Another

compound found in the complex is the bromelain, an enzyme extracted

from pineapples, bromelain possesses anti-inflammatory and

proteolytic properties, aiding in digestion and potentially

reducing inflammation (17). The

final ingredient of PCC is the liposomal vitamin C which is a

potent antioxidant that supports immune function and skin health.

Encapsulating vitamin C in liposomes enhances its bioavailability,

ensuring efficient delivery and absorption (18). Collectively, these components

contribute to the multifaceted health-promoting properties of

PCC.

Due to the established links between the bioactive

compounds and cancer dynamics, the present study aimed to examine

in vitro effects of Purple Collagen, a complex containing

bioactive double hydrolyzed collagens type I, II, III, V and X

collagen peptides and several antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

agents (inulin, elderberry extract, magnesium citrate and malate,

eggshell membrane, bromelain, black cumin extract and liposomal

vitamin C), on cell viability, migration, oxidative stress,

antioxidant status and apoptotic markers of two cancer types HCT116

colon carcinoma and MIA PaCa-2 pancreas carcinoma cells. By

evaluating the mechanisms through which PCC influences these

processes, the present study aimed to uncover its potential as a

therapeutic agent in these cancer types.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The study protocol was approved by Scientific

Research Ethical Committee of Biruni University in May 2024 with an

approval number of 2024-BIAEK/01-41. HCT116 colon carcinoma cells

were obtained from ATCC (cat. no. CCL-247) and MIA PaCa-2cells

obtained from ATCC (cat. no. CRL-1420). The present study includes

the MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic carcinoma cell line and the HCT116 cell

line, both of which are of human origin.

All cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Nutriculture;

EcoTech Biotechnology Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics (Diagnovum)

at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2

(Kabin Incubator; Esco Lifesciences Group). The cells were

maintained in these conditions throughout the experiments.

Purple Collagen, the commercial test compound used

in the present study, was supplied by the company Kiperin

Pharmaceutical Food Industry and Trade Limited Company.

Kiperin® PCC contains 10 g collagen (bioactive double

hydrolyzed collagens containing type I, II, III, V and X collagen

peptides derived from grass-fed, pasture-raised calves), 3 g of

inulin, 500 mg of elderberry (Sambucus) extract, 180 mg

magnesium citrate (providing 29 mg magnesium), 180 mg magnesium

malate (providing 27 mg magnesium), 100 mg eggshell membrane, 90 mg

bromelain (2,400 gelatin-digesting units), 90 mg black cumin

extract, 90 mg liposomal vitamin C and 40 mg 100% natural blueberry

flavor. The dosage was determined in accordance with the Turkish

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry's regulatory standards, which

specify that dietary supplements containing hydrolyzed collagen

should not provide >10 g per day (19). A concentration was used similar to a

previous double hydrolyzed collagen study, which positively

affected healthy cells and suppressed cancer cells (20), and the dosage was determined

accordingly. The selected doses, 0.5, 1 and 1.5 µg/ml, were

normalized to the in vitro cell number (6×104

cells/well) to approximate physiologically attainable levels while

minimizing off-target cytotoxic responses. Due to the structural

and functional similarities between hydrolyzed collagen and purple

collogen, the same dosage range in the experiments was applied.

Cells were detached with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, neutralized with

medium containing 10% FBS, pelleted at 300 × g for 5 min at 37°C,

and resuspended in PBS. The suspension was mixed 1:1 with 0.4%

trypan blue, incubated for 2–3 min at room temperature, and then 10

µl was loaded onto a Thoma hemocytometer. Cells were counted under

a light microscope (10X objective) in the four large corner

squares, including cells touching the top and left borders. Counts

from both chambers were averaged. Viable (unstained) and non-viable

(blue) cells were recorded separately; cell density was calculated

as cells/ml=(mean cells per square) × dilution factor (2) × 104, and %

viability=viable/(viable + non-viable) ×100. The resulting density

was used to adjust seeding for subsequent assays.

The effective dose of Purple Collagen was determined

as 1 µg/ml concentration among three doses tested (0.5, 1 and 1.5

µg/ml) by cell counts measured for three times using the Mindray

BC-6800 (Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd.) cell

counter. Each cell line was divided into two experimental groups:

Control cells (untreated) and collagen-treated cancer cells (1

µg/ml concentration of Purple Collagen). Cells were incubated with

the respective treatments for 48 h at 37°C.

Wound healing assay

To evaluate cell migration, a wound healing assay

was performed in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, consistent with

previous studies utilizing HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines

(21–23). At least 90% confluent monolayers of

cells were scratched with a sterile pipette tip, creating a uniform

gap. Images of wound closure of HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were

taken at 0, 6, 15, 30 and 43 h using an inverted light microscope

(Inverted ICX41 SOPTOP; China) at the same marked position. Wound

healing was quantified by measuring the percentage of wound closure

over time (24). Wound closure area

was measured using ImageJ (1.54g; National Institutes of Health)

software.

Measurement of oxidative stress levels

and antioxidant capacity

Cell lysates were prepared from HCT116 and MIA

PaCa-2 cell lines following standard protocols (25,26)

and stored at −80°C until analysis. All reagents and samples were

equilibrated to room temperature before use.

The total oxidant status (TOS) and total antioxidant

status (TAS) levels in two cell lines were assessed using

commercial assay kits provided by Rel Assay Diagnostics. Both

assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol,

utilizing a spectrophotometer (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer;

BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) to quantify the absorbance

changes associated with the oxidative and antioxidative properties

of the samples.

To measure TOS, the assay relied on the oxidation of

ferrous ions to ferric ions by oxidant molecules in the sample. The

ferric ions formed a colored complex with a chromogen in an acidic

medium, and the color intensity was proportional to the total

oxidant molecules present. For the assay, 45 µl cell lysate,

standard solution or distilled water (used as a blank) was mixed

with 300 µl buffer solution (pH 1.75). The absorbance of the

reaction mixture was first read at 530 nm after 30 sec.

Subsequently, 15 µl ferrous ion solution was added to the mixture,

and after incubation for 5 min at 37°C or 10 min at room

temperature, the absorbance was read again. The TOS was calculated

based on the change in absorbance and expressed as µmol

H2O2 equivalents (Eq)/l.

For TAS measurements, antioxidants in the sample

reduced dark blue-green ABTS radical cations to their colorless

form. The assay used 18 µl cell lysate, standard solution or

distilled water (blank), which was mixed with 300 µl acetate buffer

(pH 5.8). The initial absorbance of the reaction mixture was

measured at 660 nm after 30 sec. Subsequently, 45 µl ABTS

prochromogen solution was added, and after incubation for 5 min at

37°C or 10 min at room temperature, the final absorbance was

recorded. The antioxidant capacity was quantified based on the

change in absorbance and expressed as mmol Trolox Eq/l.

The TOS and TAS levels were calculated and analyzed

statistically, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation

(SD).

Reverse transcription

(RT)-quantitative (q)PCR for apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory

markers expression

Total RNA was extracted from cells, and the

concentration was assessed using a Qubit fluorometer. Subsequently,

500 ng RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA)

using the OneScript® Plus cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied

Biological Materials Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The RT reaction was carried out with Moloney-Murine

Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase. The commercial kit used in

the present study was applied according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Internal quality control steps, including positive

and negative control samples, were performed to validate the

reliability and specificity of the assay. These controls were

included in every experimental run. For experimental validation,

PCR amplification was performed, followed by agarose gel

electrophoresis. The observation of a single band of the expected

size confirmed that each primer pair was specific and

effective.

RT-qPCR was performed using the BlasTaq™ 2X qPCR

MasterMix (Applied Biological Materials Inc.) following the

supplier's protocol. Each reaction contained 2 µg of cDNA template,

1 µM each primer, and the appropriate volume of MasterMix, adjusted

to a final volume of 25 µl with nuclease-free water. The primers

used were as follows: BAX, forward

5′-GCCCTTTTGCTTCAGGGTTTCA-3′ and reverse

5′-CTGTCCAGTTCGTCCCCGAT-3′; BCL2 forward

5′-GTGGATGACTGAGTACCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAG-3′;

TP53 forward 5′-AATCTCCGCAAGAAAGGGGAG-3′ and reverse

5′-TTGGGCAGTGCTCGCTTAG-3′; cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1

(p21) forward 5′-GACTGTGATGCGCTAATGGC-3′ and reverse

5′-CCGTGGGAAGGTAGAGCTTG-3′; GAPDH (housekeeping gene)

forward 5′-CCACCCATGGCAAATTCC-3′ and reverse

5′-TGGGATTTCCATTGATGACAAG-3′.

Amplification and detection were performed on a

Bio-Rad CFX96™ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.)

under the following cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for

15 sec, annealing at 60°C for 15 sec and extension at 72°C for 15

sec. Fluorescence data were collected at the end of each extension

step. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method, normalizing the gene expressions to

GAPDH as the internal control (27).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Instat Software 8.0.1 (Dotmatics). The distribution of the

data was assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

For data that followed a normal distribution, comparisons between

groups were performed using an unpaired t-test. For non-normally

distributed data, a Mann-Whitney U test was applied. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. To

ensure the objectivity and integrity of the findings, all

statistical analyses were performed by an independent researcher

not affiliated with Kiperin Pharmaceutical.

Results

Cell viability and proliferation

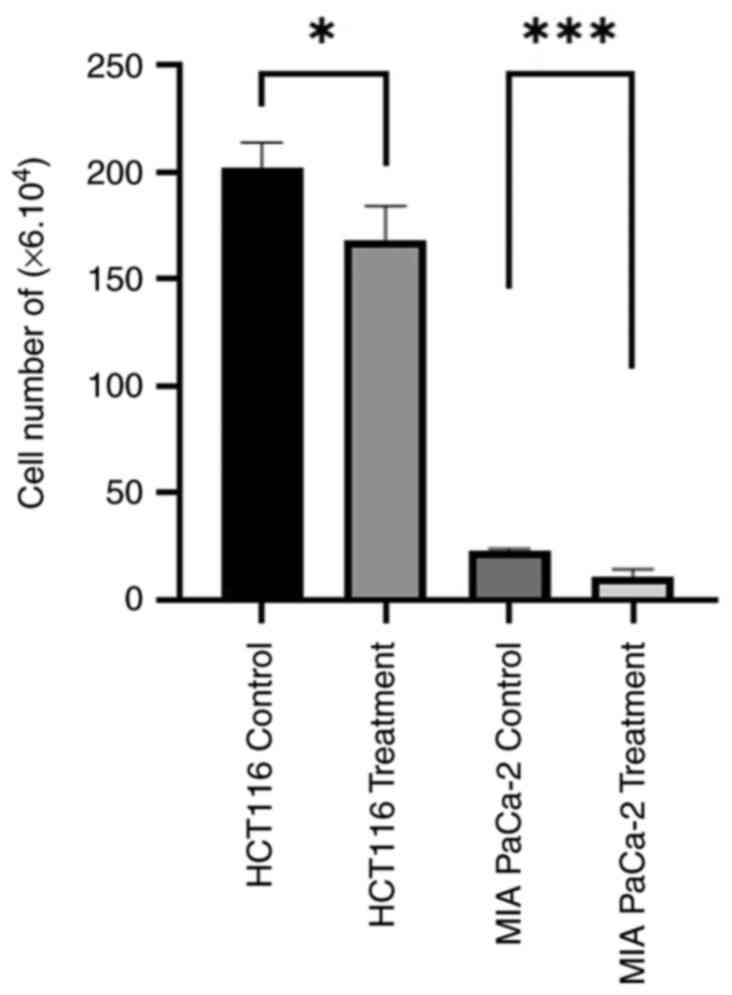

The cell numbers of HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines

were assessed in the control conditions and after treatment with 1

µg/ml dose of PCC (Fig. 1). The

results indicate a significant decrease in the number of HCT116

cells treated with the PCC compared with the control group

(P=0.0141). Similarly, a significant reduction in the number of MIA

PaCa-2 cells was observed following treatment with the PCC compared

with the control group (P=0.0004). These findings suggest that

treatment with PCC has inhibitory effects on the proliferation of

colon cancer and pancreas carcinoma cells.

Cell migration

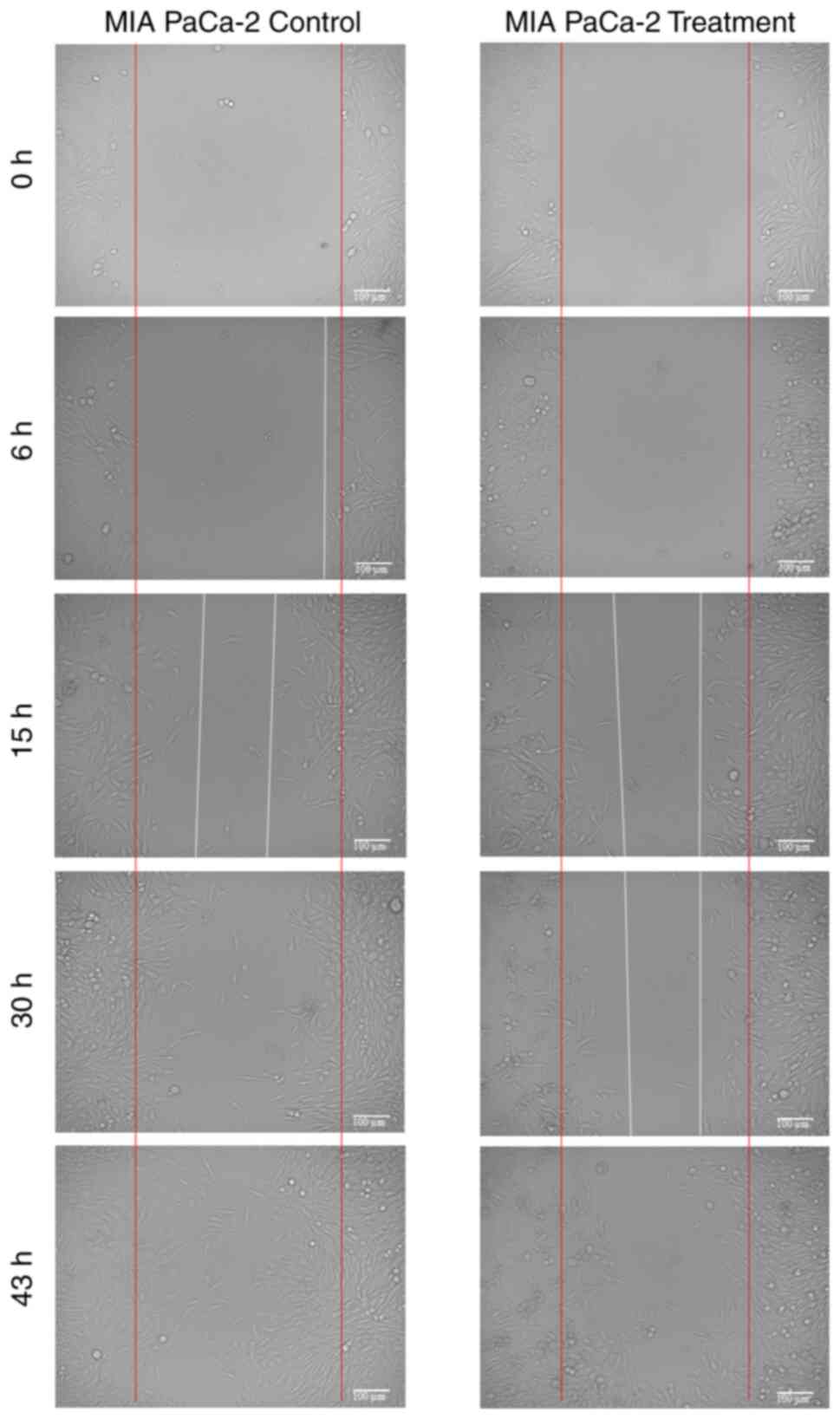

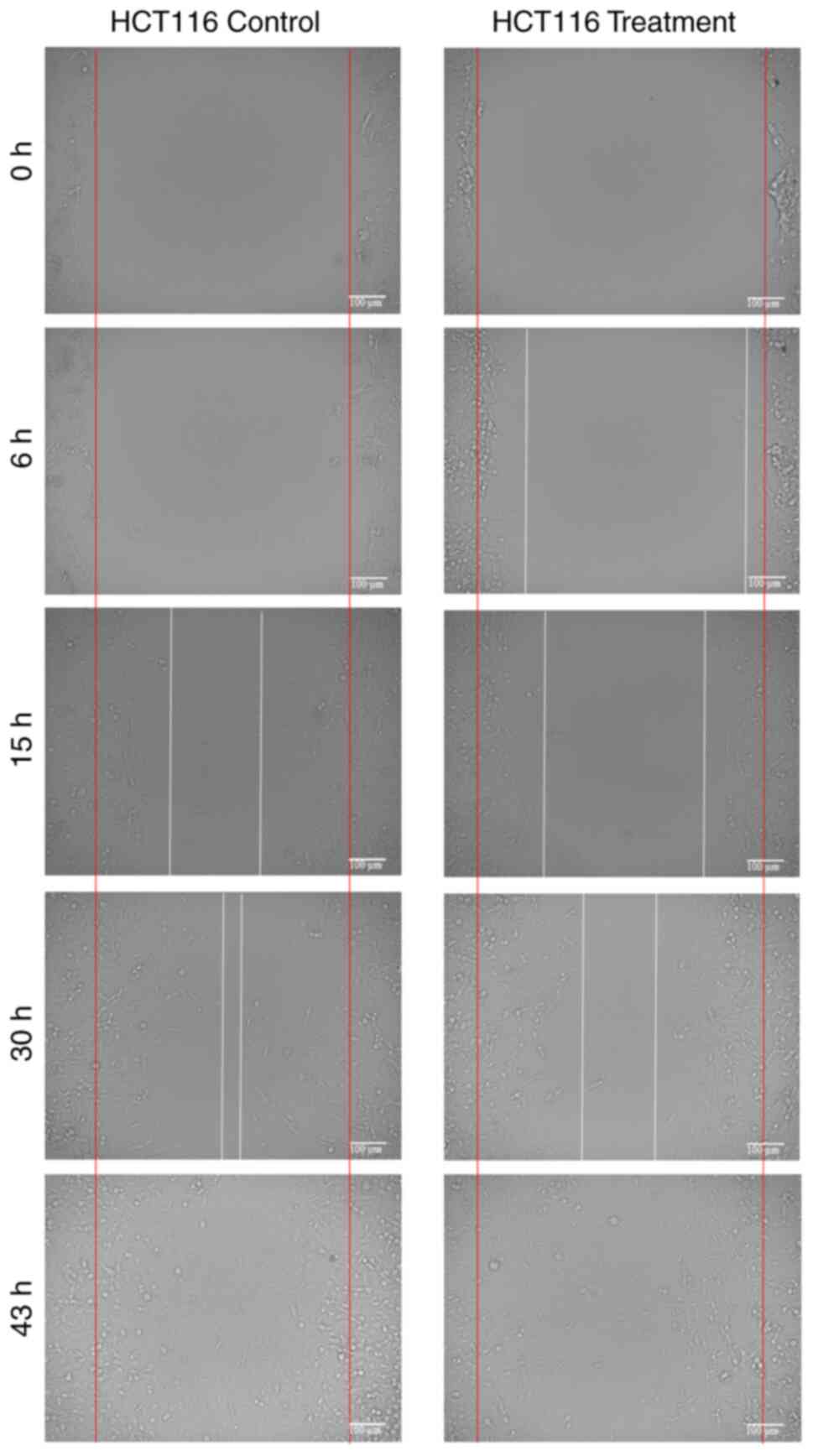

The migration rates of HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cells

over different incubation periods are presented in Table I, and representative microscopic

images are shown in Figs. 2 and

3. In both cell lines, treatment

with 1 µg/ml PCC reduced migration compared with the controls,

although the extent and timing of inhibition varied between the two

cell lines.

| Table I.Migration rate of the wound healing

assay in control or PCC-treated cells. |

Table I.

Migration rate of the wound healing

assay in control or PCC-treated cells.

| Incubation | Migration rate of

MIA PaCa-2 cells (%) | Migration rate of

HCT116 cells (%) |

|---|

| 6 h |

|

|

|

Control | 7.8 | 1.6 |

| 1 µg/ml

PCC | 5.0 | 12.8 |

|

P-value | 0.006 | <0.00014 |

| 15 h |

|

|

|

Control | 46.1 | 43.3 |

| 1 µg/ml

PCC | 43.8 | 30.4 |

|

P-value | 0.549 | <0.0003 |

| 30 h |

|

|

|

Control | 74.0 | 63.8 |

| 1 µg/ml

PCC | 42.3 | 61.2 |

|

P-value | 0.226 | 0.003 |

| 43 h |

|

|

|

Control | 91.7 | 100 |

| 1 µg/ml

PCC | 72.1 | 85.9 |

|

P-value | 0.002 | >0.999 |

For MIA PaCa-2 cells, migration was significantly

reduced in the PCC group at 6 h (5.0 vs. 7.8% P=0.006) and at 43 h

(72.1 vs. 91.7%; P=0.002). However, at 15 and 30 h, the reductions

(43.8 vs. 46.1% and 42.3 vs. 74.0%, respectively) did not reach

statistical significance (P=0.549 and P=0.226, respectively).

For HCT116 cells, PCC treatment resulted in

consistently significant reductions in migration at early and

intermediate time points. At 6 h, migration was markedly higher in

treated cells (12.8 vs. 1.6%; P=0.00014), compared with the control

cells. At 15 and 30 h, PCC-treated cells showed significantly lower

migration compared with the controls (30.4 vs. 43.3%; P=0.0003;

61.2 vs. 63.8%; P=0.003). At 43 h, the control cells had achieved

complete closure (100%), while treated cells reached 85.9%;

however, this difference was not statistically significant

(P>0.999).

Oxidative and antioxidant status

The TOS and TAS levels in HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2

cells under control conditions and after treatment with 1 µg/ml PCC

are presented in Table II. For

HCT116 cells, TOS levels did not differ significantly between the

control (0.302±0.181 µmol H2O2 Eq/l) and

PCC-treated groups (1.253±2.401 µmol H2O2

Eq/l; P=0.7619). However, TAS levels demonstrated a significant

reduction in the PCC-treated group (0.122±0.102 mmol Trolox Eq/l)

compared with the control (2.414±2.39 mmol Trolox Eq/l;

P=0.0095).

| Table II.TOS and TAS levels in HCT116 and MIA

PaCa-2 cells treated with 1 µg/ml PCC. |

Table II.

TOS and TAS levels in HCT116 and MIA

PaCa-2 cells treated with 1 µg/ml PCC.

| A, HCT116

cells |

|---|

|

|---|

| Group | TOS (µmol

H2O2 Eq/l) | TAS (mmol Trolox

Eq/l) |

|---|

| Control | 0.302±0.181 | 2.414±2.390 |

| 1 µg/ml PCC | 1.253±2.401 | 0.122±0.102 |

|

P-value | 0.762 | 0.01 |

|

| B, MIA PaCa-2

cells |

|

| Group | TOS (µmol

H2O2 Eq/l) | TAS (mmol Trolox

Eq/l) |

|

| Control | 5.090±0.560 | 2.300±0.004 |

| 1 µg/ml PCC | 8.720±2.450 | 0.007±0.00014 |

|

P-value | 0.292 | 0.600 |

For MIA PaCa-2 cells, no significant differences

were observed in either TOS levels (control, 5.09±0.56 µmol

H2O2 Eq/l; PCC-treated, 8.72±2.45 µmol

H2O2 Eq/l; P=0.292) or TAS levels (control,

2.300±0.004 mmol Trolox Eq/l; PCC-treated, 0.007±0.000 mmol Trolox

Eq/l; P=0.686). These results indicate that 1 µg/ml PCC has a

cell-specific effect on oxidative and antioxidant balance; however,

there was a significant decrease in TAS levels increase in TOS

levels in HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines.

Expression levels of apoptotic and

cell cycle regulatory markers

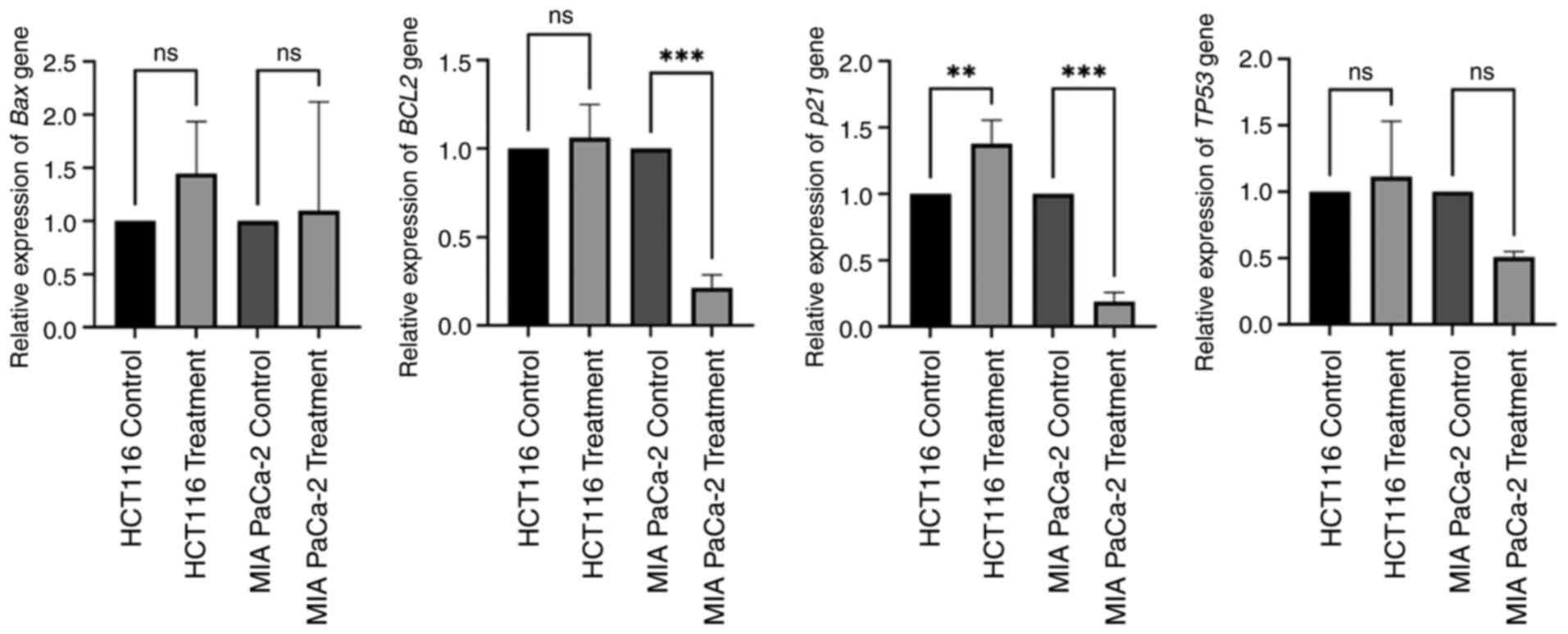

The expression levels of BAX, BCL2, TP53 and

p21 in HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cells under control conditions

and after treatment with 1 µg/ml PCC are presented in Fig. 4. In both cell lines, BAX

expression was not significantly altered with PCC treatment

compared with the control. BCL2 expression was significantly

decreased in MIA PaCa-2 cells (P=0.00029), but not in HCT116 cells.

The tumor suppressor marker p21 showed significant

upregulation in HCT116 cells (0.00221) after PCC treatment, but

downregulation in MIA PaCa-2 cells (P=0.00025). TP53

expression did not differ with PCC treatment in both cell lines

compared with the control. These results suggest that 1 µg/ml PCC

caused an apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory effect, affecting

BCL2 and p21 expression levels in different cell

lines. It was observed that pro-apoptotic pathways were activated

in both the HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines. This highlights the

potential role of the PCC in modulating apoptosis and cell cycle

regulation.

Discussion

The findings of the present experimental study

demonstrate that the PCC exhibits significant cell-type-specific

effects on cancer cell proliferation, migration, oxidative stress

and the expression of apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory markers.

The observed reduction in cell viability and proliferation in

HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cells suggests that PCC treatment selectively

inhibits the growth of colon cancer and pancreas carcinoma cells.

Furthermore, the differential modulation of oxidative and

antioxidant status, with a notable reduction in TAS levels in

HCT116 cells, highlights the potential of PCC to influence cellular

redox balance. The significant reduction in migration observed in

both cell lines, particularly at intermediate time points, further

underscores the potential role of PCC in inhibiting cancer cell

motility and metastatic capacity.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of

cancer-associated mortalities globally (28). While approximately half of patients

with colorectal cancer initially respond positively to conventional

therapies (29), long-term survival

remains poor due to the high likelihood of metastasis following

multimodal treatment (30).

Therefore, alternative therapies are needed. The treatment of

HCT116 colorectal cancer cells with PCC, which includes bioactive

double-hydrolyzed collagens (types I, II, III, V and X) and various

bioactive components (inulin, elderberry extract, magnesium citrate

and malate, eggshell membrane, bromelain, black cumin extract,

liposomal vitamin C), resulted in a significant reduction in cell

proliferation and migration. This inhibitory effect may be

associated with downregulation of anti-apoptotic markers

BCL2 and p21. These findings align with existing

literature indicating that certain bioactive compounds can modulate

apoptotic pathways in colorectal cancer cells (31). For instance, a previous study has

demonstrated that targeting specific molecular pathways can enhance

the expression of pro-apoptotic signals, thereby promoting cancer

cell death (32). Additionally, the

observed modulation of oxidative and antioxidant status, evidenced

by changes in TOS and TAS levels, suggests that components of the

PCC may influence the redox balance within HCT116 cells. This is

consistent with research indicating that alterations in oxidative

stress can impact cancer cell behavior (33,34).

Collectively, these results suggest that PCC exerts its anticancer

effects through the modulation of apoptosis, oxidative stress and

cell migration pathways in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells.

Sato and Seiki (35)

also suggest that hydrolyzed collagen fragments may trigger

intracellular stress responses, potentially explaining the

upregulation of tumor suppressor proteins such as TP53 and

p21 in the present study. According to Madri and Furthmayr

(36), the interaction of collagen

with cellular signaling pathways may affect apoptosis and cell

cycle regulation. Bioactive peptides in the PCC may modulate these

pathways, leading to the observed changes in apoptotic and cell

cycle markers. Blueberry extract, a dietary phytochemical, has been

reported to have a chemo-preventive activity in triple negative

breast cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo

(37,38). Blueberry reduced cell proliferation

in HCC38, HCC1937 and MDA-MB-231 cells and reduced the metastatic

potential of MDA-MB-231 cells through modulation of the

PI3K/AKT/NFkB pathway. Bilberry treatment decreased MMP-9

activity and urokinase-type plasminogen activator secretion, and

increased tissue inhibitor of MMP-1 and plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 secretion in MDA-MB-231 cells (38,39).

Minker et al (40) reported

that the proanthocyanidins extracted from 11 berry species

including blueberry may be preventive against human colorectal

cancer cell lines by inducing apoptosis. In line with the

literature, the PCC, which also contains blueberry extract, may

modulate the metastatic features of the cell lines HCT116 and MIA

PaCa-2 with different incubation durations.

Notably, the inhibitory effect on migration,

observed in both HCT116 and MIA PaCa-2 cells at intermediate time

points, aligns with prior studies suggesting that hydrolyzed

collagen fragments can interfere with ECM integrity, integrin

signaling, and MMP activity, and the phytochemicals with anticancer

features. These findings emphasize the complexity of PCC which has

potential role against the cancer progression and highlight the

potential therapeutic value of bioactive compounds in complex, in

selectively modulating cancer cell behavior. Future studies should

explore the mechanistic underpinnings of these effects, with a

focus on optimizing collagen formulations and dosages to enhance

their anticancer efficacy across diverse tumor types.

The findings showed a significant decrease in

BCL2 gene expression in MIA PaCa-2 cells as well as

modulation of p21 expression in both cell types treated with

PCC. These changes indicate that although the collagen complex

regulates p21 gene expression, which serves an important

role in the repair mechanism and the process leading to apoptosis,

it indicates its pro-apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory effect by

decreasing BCL2 gene expression. Mammoto et al

(41) and Payne and Huang (42) describe how specific collagen

interactions can modulate intracellular signaling pathways,

including those regulating apoptosis. Hydrolyzed collagen fragments

in the PCC can disrupt essential survival pathways by interfering

with ECM-integrin signaling, resulting in increased pro-apoptotic

markers. Furthermore, Yin et al (43) identified collagen genes associated

with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and immune infiltration,

highlighting their role in pancreatic carcinoma progression. The

observed decrease in BCL2 expression may indicate that the

PCC modulates stress response pathways associated with these

processes, pushing pancreatic carcinoma cells towards apoptosis

rather than proliferation.

The present study has several limitations that

should be considered. The in vitro design does not fully

replicate the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, including

interactions with immune cells and vascular structures.

Furthermore, only a single dose of PCC was tested, and a broader

dose-response analysis was not performed. The short-term nature of

the experiments does not account for potential long-term effects or

resistance mechanisms. While significant changes in apoptotic and

cell cycle markers were observed, the specific molecular mechanisms

underlying these effects were not explored in detail. Future

studies are warranted to confirm the observed gene expression

changes at the protein and functional levels. Additionally, in

vivo experiments were not performed, which limits the

translational relevance of the results. The study also did not

isolate the contributions of individual bioactive components within

the collagen complex or assess detailed oxidative stress markers

beyond TOS and TAS levels. As the formulation contains multiple

bioactive ingredients, it remains unclear whether the observed

biological effects are due to individual components or synergistic

interactions. Future studies are warranted to investigate the

specific contributions and potential synergistic mechanisms of each

component A more comprehensive migration analysis and consideration

of cell line variability would further strengthen the findings.

Addressing these limitations in future research will provide more

robust and clinically relevant insights.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

underscore the cell-type-specific effects of PCC on cancer cell

proliferation, migration, oxidative stress and apoptosis. While the

complex demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on the

viability and migration of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells, its

effects on MIA PaCa-2 cells varied, reflecting the distinct

biological characteristics of these cancer types. The pro-apoptotic

and cell cycle-regulatory effects, marked by upregulation of

BCL2 and p21, suggest that PCC may modulate key

molecular pathways to promote apoptosis in certain cancers.

Oxidative and antioxidant modulation, particularly TOS decrease and

TAS increase in cancer cells, highlights the role of collagen in

influencing redox balance.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Purple Collagen complex is a product developed by Kiperin

Pharmaceutical Food Industry and Trade Limited Company at Biruni

University Technopark with support from the Ministry of Industry

and Technology of the Republic of Türkiye (project support no.

93867). The consumables and reagents used in the study were

provided by Kiperin Pharmaceutical Food Industry and Trade Limited

Company.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LKB served as the project manager, supervised the

study, contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and

participated in the manuscript writing and editing. CY performed

the statistical analysis, optimized the methodology and provided

critical revisions to the manuscript. NH contributed to data

interpretation, literature review and manuscript editing. LKB and

CY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

participated in an independent and impartial evaluation of the

study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Scientific

Researches Ethical Committee of Biruni University in May 2024 with

an approval number of 2024-BIAEK/01-41. All procedures were

performed in accordance with ethical research guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LKB serves as a scientific consultant for Kiperin

Pharmaceutical Food Industry and Trade Limited Company (Istanbul,

Turkey). The authors used Kiperin collagen in the study from

Kiperin Pharmaceutical Food Industry and Trade Limited Company,

although the study was conducted independently, and the company had

no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis,

interpretation of results or manuscript preparation. The other

authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E and

Soerjomataram I: The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a

leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 127:3029–3030.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, Kuhn M, Yang J,

Jiao L, Wang Z, Li W, Geldsetzer P, Bärnighausen T, et al:

Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers

in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol.

9:465–472. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Guida F, Kidman R, Ferlay J, Schüz J,

Soerjomataram I, Kithaka B, Ginsburg O, Vega RB, Galukande M,

Parham G, et al: Global and regional estimates of orphans

attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat Med.

28:2563–2572. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN,

Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M,

Boettiger D, et al: Tensional homeostasis and the malignant

phenotype. Cancer Cell. 8:241–254. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Desai N, Sahel D, Kubal B, Postwala H,

Shah Y, Chavda VP, Fernandes C, Khatri DK and Vora LK: Role of the

extracellular matrix in cancer: Insights into tumor progression and

therapy. Adv Ther. 8:24003702025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Gialeli C and

Karamanos NK: Extracellular matrix structure. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

97:4–27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Winkler J, Abisoye-Ogunniyan A, Metcalf KJ

and Werb Z: Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour

progression and metastasis. Nat Commun. 11:51202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Frantz C, Stewart KM and Weaver VM: The

extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 123:4195–4200. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zaffar M and Pradhan A: Assessment of

anisotropy of collagen structures through spatial frequencies of

Mueller matrix images for cervical pre-cancer detection. Appl Opt.

59:1237–1248. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Song K, Yu Z, Zu X, Li G, Hu Z and Xue Y:

Collagen remodeling along cancer progression providing a novel

opportunity for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

23:105092022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kaur R, Bhardwaj A and Gupta S: Cancer

treatment therapies: Traditional to modern approaches to combat

cancers. Mol Biol Rep. 50:9663–9676. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hiel S, Bindels LB, Pachikian BD, Kalala

G, Broers V, Zamariola G, Chang BPI, Kambashi B, Rodriguez J, Cani

PD, et al: Effects of a diet based on inulin-rich vegetables on gut

health and nutritional behavior in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr.

109:1683–1695. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Domínguez R, Zhang L, Rocchetti G, Lucini

L, Pateiro M, Munekata PES and Lorenzo JM: Elderberry (Sambucus

nigra L.) as potential source of antioxidants: Characterization,

optimization of extraction parameters and bioactive properties.

Food Chem. 330:1272662020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Srinivasan K: Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) and

black cumin (Nigella sativa) seeds: Traditional uses, chemical

constituents, and nutraceutical effects. Food Qual Saf. 2:1–6.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Morel V, Pickering ME, Goubayon J, Djobo

M, Macian N and Pickering G: Magnesium for pain treatment in 2021?

State of the art. Nutrients. 13:13972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ruff KJ, DeVore DP, Leu MD and Robinson

MA: Eggshell membrane: A possible new natural therapeutic for joint

and connective tissue disorders: Results from two open-label human

clinical studies. Clin Interv Aging. 4:235–240. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kansakar U, Trimarco V, Manzi MV, Cervi E,

Mone P and Santulli G: Exploring the therapeutic potential of

bromelain: Applications, benefits, and mechanisms. Nutrients.

16:20602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Maurya VK, Shakya A, McClements DJ,

Srinivasan R, Bashir K, Ramesh T, Lee J and Sathiyamoorthi E:

Vitamin C fortification: Need and recent trends in encapsulation

technologies. Front Nutr. 10:12292432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of

Agriculture and Forestry, . List of restricted substances for food

supplements. 2025.Available from:. https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/GKGM/Belgeler/DB_Gida_Isletmeleri/Takviye_Edici_Gidalar_Kisitli_Maddeler_Listesi.pdf

|

|

20

|

Batur LK, Yavas C and Hekim N: Kiperin

double-hydrolyzed collagen as a potential anti-tumor agent: Effects

on HCT116 colon carcinoma cells and oxidative stress modulation.

Curr Issues Mol Biol. 47:3642025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Huang YP, Yeh CA, Ma YS, Chen PY, Lai KC,

Lien JC and Hsieh WT: PW06 suppresses cancer cell metastasis in

human pancreatic carcinoma MIA PaCa-2 cells via the inhibitions of

p-Akt/mTOR/NF-κB and MMP2/MMP9 signaling pathways in vitro. Environ

Toxicol. 39:2768–2781. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Abassi H, Ayed-Boussema I, Shirley S, Abid

S, Bacha H and Micheau O: The mycotoxin zearalenone enhances cell

proliferation, colony formation and promotes cell migration in the

human colon carcinoma cell line HCT116. Toxicol Lett. 254:1–7.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Liu S, Yang W, Li Y and Sun C: Fetal

bovine serum, an important factor affecting the reproducibility of

cell experiments. Sci Rep. 13:19422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jonkman JEN, Cathcart JA, Xu F, Bartolini

ME, Amon JE, Stevens KM and Colarusso P: An introduction to the

wound healing assay using live-cell microscopy. Cell Adh Migr.

8:440–451. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Batur LK, Yavas C, Merdan YE and Aygan A:

Kiperin postbiotic supplement-enhanced bacterial supernatants

promote fibroblast function: Implications for regenerative

medicine. Biomedicines. 13:14302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sevindik M, Akgul H, Bal C, Altuntas D,

Korkmaz AI and Dogan M: Oxidative stress and heavy metal levels of

Pholiota limonella mushroom collected from different regions. Curr

Chem Biol. 12:169–172. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:7–30. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Singh A, Sweeney MF, Yu M, Burger A,

Greninger P, Benes C, Haber DA and Settleman J: TAK1 inhibition

promotes apoptosis in KRAS-dependent colon cancers. Cell.

148:639–650. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dienstmann R, Salazar R and Tabernero J:

Personalizing colon cancer adjuvant therapy: Selecting optimal

treatments for individual patients. J Clin Oncol. 33:1787–1796.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wu X, Cai J, Zuo Z and Li J: Collagen

facilitates the colorectal cancer stemness and metastasis through

an integrin/PI3K/AKT/Snail signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

114:1087082019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Turner BTX, Kacem MB, Liu A, Hsieh CER,

Hegde SM and Curran MA: 787 Targeting DNA damage response modulates

antiphagocytic signals to convert radiotherapy into a systemic

immunotherapy to treat metastatic colorectal cancer. J Immuno

Therapy Cancer. 12:2024.

|

|

33

|

Skowronki K, Andrews J, Rodenhiser DI and

Coomber BL: Genome-wide analysis in human colorectal cancer cells

reveals ischemia-mediated expression of motility genes via DNA

hypomethylation. PLoS One. 9:e1032432014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hamidian K, Saberian MR, Miri A, Sharifi F

and Sarani M: Doped and un-doped cerium oxide nanoparticles:

Biosynthesis, characterization, and cytotoxic study. Ceram Int.

47:13895–13902. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sato H and Seiki M: Regulatory mechanism

of 92 kDa type IV collagenase gene expression which is associated

with invasiveness of tumor cells. Oncogene. 8:395–405.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Madri JA and Furthmayr H: Collagen

polymorphism in the lung: An immunochemical study of pulmonary

fibrosis. Hum Pathol. 11:353–366. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Reboredo-Rodríguez P: Potential roles of

berries in the prevention of breast cancer progression. J Berry

Res. 8:307–323. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Adams LS, Kanaya N, Phung S, Liu Z and

Chen S: Whole blueberry powder modulates the growth and metastasis

of MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast tumors in nude mice. J Nutr.

141:1805–1812. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Fang M, Yuan J, Peng C and Li Y: Collagen

as a double-edged sword in tumor progression. Tumour Biol.

35:2871–2882. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Minker C, Duban L, Karas D, Järvinen P,

Lobstein A and Muller CD: Impact of procyanidins from different

berries on caspase 8 activation in colon cancer. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2015:1541642015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mammoto T, Jiang A, Jiang E, Panigrahy D,

Kieran MW and Mammoto A: Role of collagen matrix in tumor

angiogenesis and glioblastoma multiforme progression. Am J Pathol.

183:1293–1305. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Payne LS and Huang PH: The pathobiology of

collagens in glioma. Mol Cancer Res. 11:1129–1140. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yin W, Zhu H, Tan J, Xin Z, Zhou Q, Cao Y,

Wu Z, Wang L, Zhao M, Jiang X, et al: Identification of collagen

genes related to immune infiltration and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in glioma. Cancer Cell Int. 21:2762021. View Article : Google Scholar

|