Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is regarded as the most

common biliary malignancy, accounting for 80–95% of all biliary

malignancies worldwide (1). The

average overall survival of patients with GBC is 6 months, and the

5-year survival rate is 5% (2).

Radical resection remains the only curative approach for GBC, with

postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy routinely given.

However, there still exists >1/3 chance of metastasis and

recurrence after surgery (3,4). Once

GBC recurs, whether it is local recurrence or distant metastasis,

the 5-year overall survival rate of patients remains notably low at

just 15–20% (5).

For advanced patients with multiple distant

metastases, surgical resection does not meet the needs of the

patients. Patients with poor general condition are also unable to

tolerate chemotherapy (6,7). Minimally invasive interventional

therapy is characterized by minimal trauma and accurate

positioning, which is suitable for these patients. In several

cases, studies have focused on the local efficacy of interventional

therapy, but have ignored the systemic immune response caused by

interventional therapy (8,9). Only sporadic reports have shown the

efficacy of thermal ablation in achieving distant or systemic

responses (10–13). Microwave ablation (MWA) can kill

tumor cells in situ, activate the immune system of the body

and exert an immune attack on distant metastases, which is

consistent with the concept of the tumor in situ vaccine

(14). However, it is reported that

the immune response induced by it is relatively weak, which is

affected by the immunosuppressive microenvironment, and the effect

is not sustainable (15).

Radioactive particles can change the tumor microenvironment (TME)

from an immunosuppressive state to an immune activation state

(16,17).

The present study reports a case of a female patient

with advanced GBC whose disease course extended >5 years from

the initial diagnosis in order to validate the potential of

local-only therapy for metastatic GBC and investigate the immune

dynamics enabling durable remission. During the disease course

time, new metastatic tumors occurred several times, and the patient

underwent sequential treatment, including five rounds of ultrasound

(US)-guided microwave ablation (MWA) and one occurrence of

radioactive iodine-125 (125I) seed implantation

(RSI).

Case report

Case presentation

In 2018, a 60-year-old woman presented with

recurrent epigastric pain for 6 months. US was performed at

Zhenjiang Hospital of Chinese Traditional and Western Medicine

(Zhenjiang, China) and showed the gallbladder was almost filled

with an heterogeneous isoechoic mass, meeting the criteria for

high-risk polyp resection. Therefore, although the nature of the

mass was not clear, early intervention was needed. The patient

underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with final pathology

showing poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder,

with a size of 1.5×0.8×0.6 cm invading the whole layer, and a small

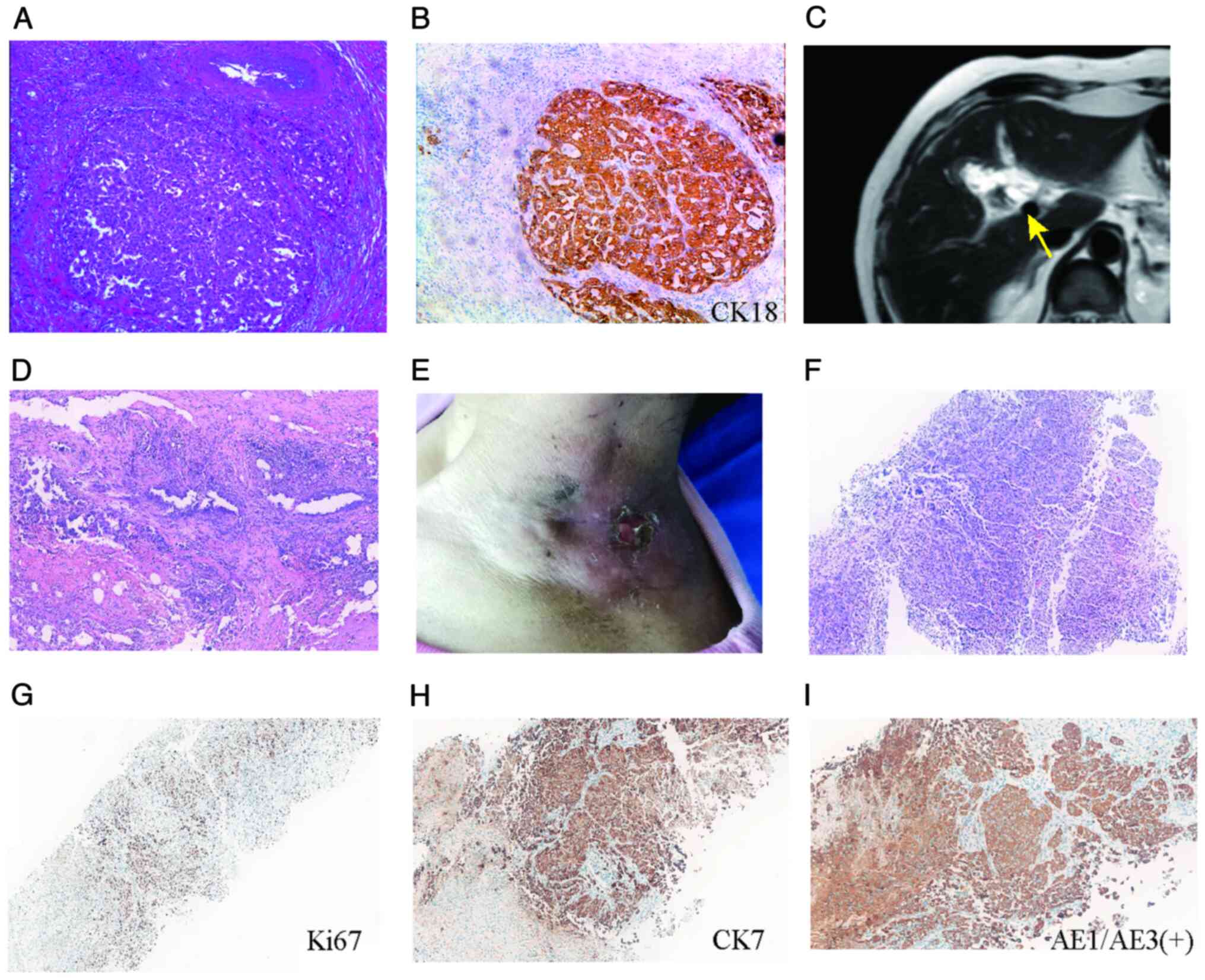

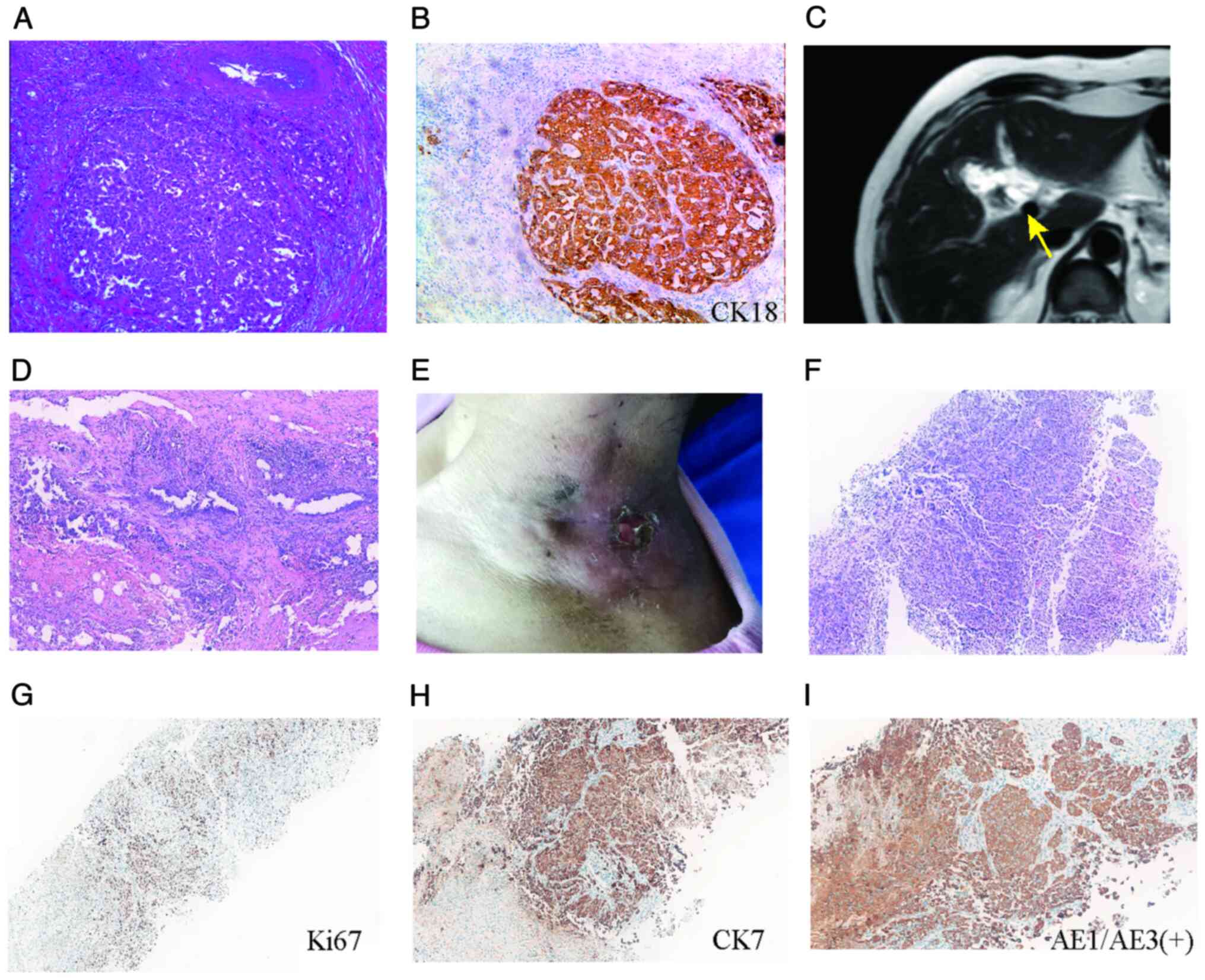

amount of atypical glands at the margin of the bile neck (Fig. 1A). According to tumor, lymph node

and metastasis (TNM) staging, it was T3NxMO and belonged to stage

IIa, with immunohistochemistry analysis of tissue samples showing

cytokeratin (CK; +), CK18 (+; Fig.

1B), Ki-67 (+, 30%) and α-fetoprotein (AFP; -) (Fig. S1A).

| Figure 1.Diagnostic and pathological

progression of gallbladder cancer. (A) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

specimen showing poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (H&E).

(B) IHC of primary tumor with positive CK18 confirming epithelial

origin. Magnification, ×400×. (C) Preoperative MRI showing

irregular gallbladder wall thickening (arrow) with adjacent hepatic

infiltration, suggesting residual malignancy. (D) Radical resection

specimen of residual poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in

gallbladder bed (H&E, 200× magnification). (E) Clinical

presentation showing left neck mass (8×8 cm) with surface

ulceration prior to treatment. (F) Core-needle biopsy of neck mass

demonstrated malignant epithelial cells (H&E), consistent with

metastatic carcinoma. IHC of neck metastasis showing (G) Ki-67 (+,

75%) indicative of a high proliferative index, (H) CK7 (+),

indicating biliary differentiation and (I) AE1/AE3 (+) indicating

pan-cytokeratin confirmation of epithelial lineage. Magnification,

×100. IHC, immunohistochemistry; CK, cytokeratin; AE1/AE3,

cytokeratin AE1/AE3; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. |

For definitive management, the patient was referred

to Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing

University (Nanjing, China). Preoperative MRI demonstrated

irregular gallbladder wall thickening with adjacent hepatic

infiltration, suggesting residual malignancy (Fig. 1C). Radical cholecystectomy was

performed, with pathology confirming residual poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma in the gallbladder bed (Figs. 1D and S1B). After surgery, the patient declined

chemoradiotherapy.

In September 2020, the patient presented to the

Department of Medical Ultrasound (Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu

University) with the chief complaint of a large mass on their left

neck for 3 months. A physical examination revealed an 8×8 cm mass

in the left neck, with skin ulcers visible on its surface (Fig. 1E).

To make a definite diagnosis, a core-needle biopsy

of the left neck mass was performed. The pathological result

indicated malignant epithelial cells (Fig. 1F), possibly originating from the

gallbladder, demonstrated using immunohistochemistry analysis of

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (+), vimentin (−), transcription termination

factor 1 (TTF-1; -), thyroglobulin (TG; -), CK5/6 (−), CK7 (+),

CK20 (+), caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX-2; -), Ki-67 (+, 75%)

(Figs. 1G-I and S1C). The Ki-67 proliferative index was

quantitatively assessed by a pathologist by visually estimating the

percentage of positive tumor nuclei in representative high-power

fields, according to standard diagnostic protocols.

The diagnosis of metastatic GBC was solidified by

systematically excluding other primary sites. The

immunohistochemical profile, notably CK7/CK20 positivity indicating

biliary origin, coupled with negative markers for lung (TTF-1),

thyroid (TG), colorectal (CDX-2) and squamous carcinomas (CK5/6),

provided definitive cellular evidence against alternative

primaries. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4-μm-thick

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections using standard diagnostic

protocols. Antigen retrieval involved citrate buffer incubation,

followed by primary antibody incubation (Jiangsu Lanou Biological

Material Co., Ltd.), polymer-HRP detection with DAB chromogen and

hematoxylin counterstain. This molecular characterization was

reinforced by the patient's established history of GBC resection 2

years prior. Regional imaging using physical examination and

targeted ultrasonography of the neck/axilla revealed no evidence of

new primary lesions. Although comprehensive whole-body PET/CT was

not performed due to the palliative treatment focus, the

convergence of pathological, clinical and localized radiological

findings confirmed metastatic GBC as the sole etiology.

Treatment

After consulting with multidisciplinary experts at

the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, the application of

US-guided MWA for neck mass was considered as a palliative therapy

for alleviating the patient's condition. Written informed consent

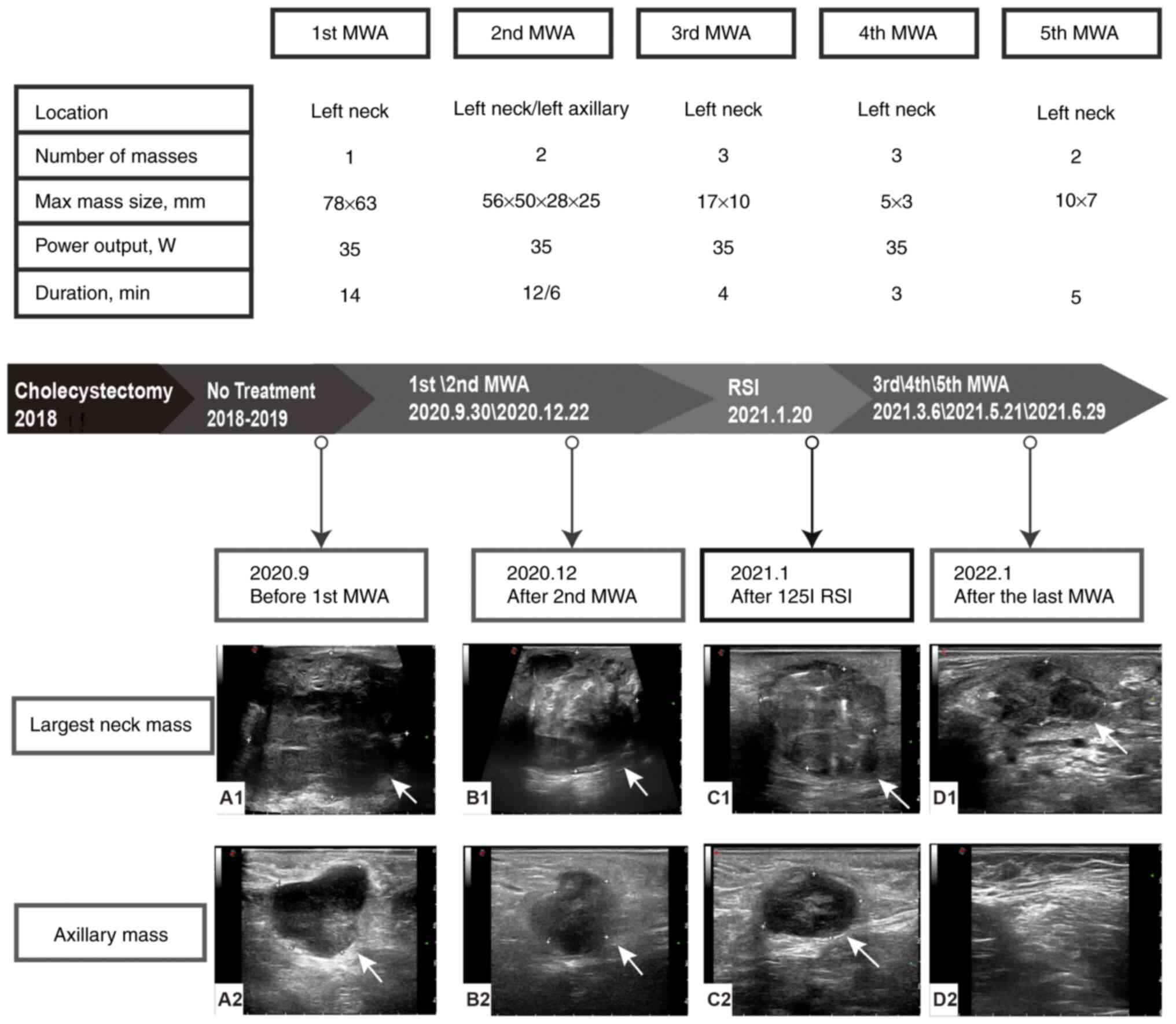

was obtained from the patient before MWA. Fig. 2 shows the specific treatment

timelines and details regarding the patient's metastases. Arrows

indicate the location of the mass vs. the ablation foci.

In September 2020, the patient underwent US-guided

MWA treatment of the left neck masses. Preoperative US showed that

the size of the left neck mass was 78×63×57 mm, with a clear

boundary and slightly irregular edge. The left common carotid

artery and internal jugular vein were notably compressed (Fig. 2A). An ECO-100A1 microwave

therapeutic system (Nanjing ECO Medical Technology Co., Ltd.)

consisting of a microwave generator, a hollow water-cooled shaft

antenna (16 gauge) and a flexible coaxial cable was employed. The

whole ablation process was performed under the guidance of US. A

total of 10 ml 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site for

local infiltration anesthesia, followed by 20 ml saline to isolate

and protect the surrounding tissue. The needle pin was inserted

into the lesion through previously determined path, and ablation

was performed using a continuous method, with a power output of 35

W. The ablation continued until the transient hyperechoic zone

covered the entire mass. The whole procedure lasted 14 min and 8

sec. The procedure was smooth, and the patient had no obvious

abnormal symptoms.

In December 2020, the patient underwent the second

MWA treatment for both left neck and left axillary masses.

Preoperative US showed that the size of the left axillary mass was

28×25 mm, and the left neck mass had enlarged to 56×50 mm. The

intraoperative power output was 35 W. The ablation time for the

left axillary mass was 5 min and 47 sec, and for the left neck

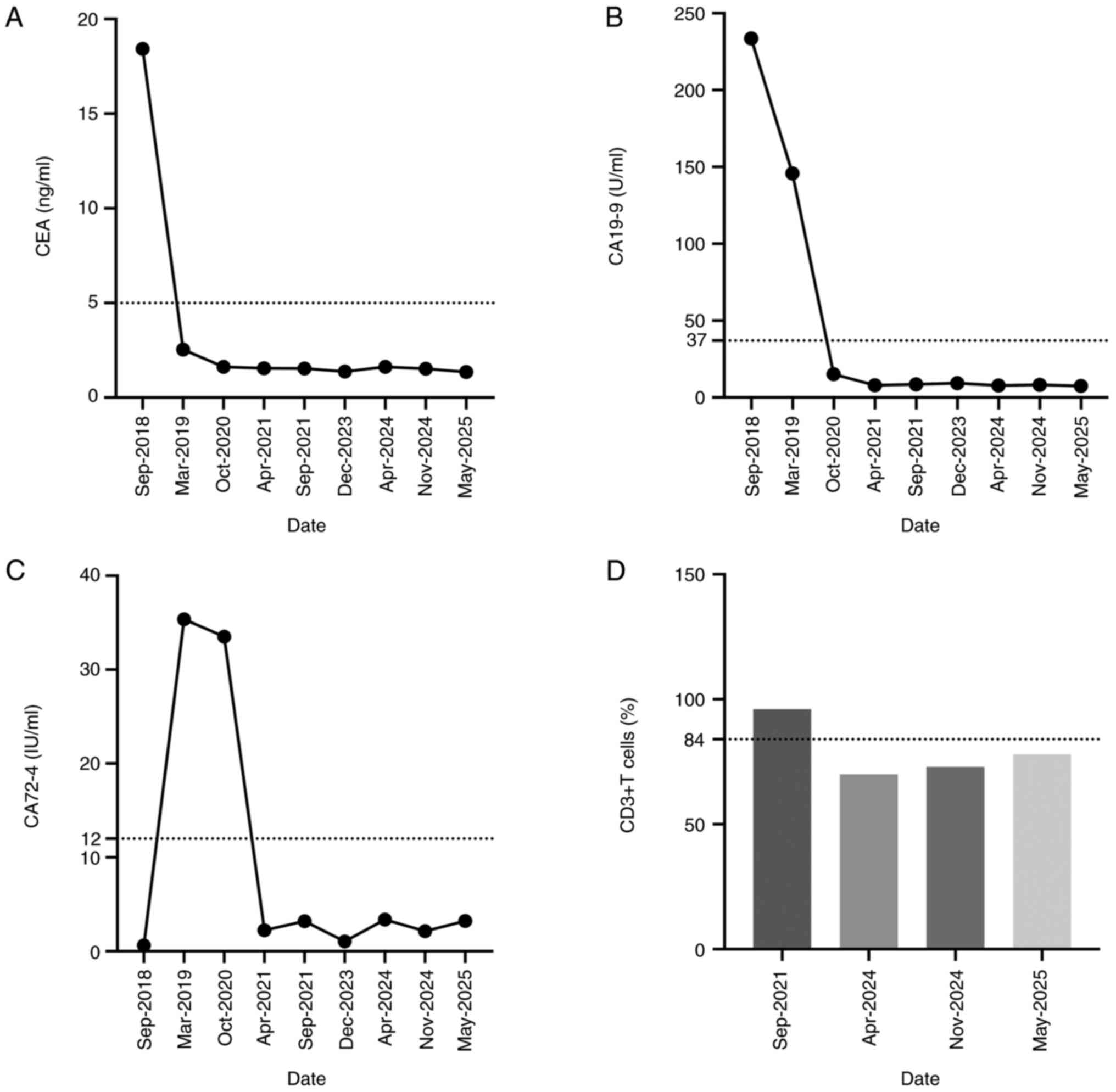

mass, it was 12 min and 30 sec. The levels of postoperative tumor

indicators, measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay

were: Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 1.62 ng/ml; carbohydrate

antigen CA19-9, 15.11 U/ml; and CA72-4, 33.51 IU/ml (Fig. 3A-C).

After 1 week, a follow-up US revealed an ablation

focus measuring 22×18 mm in the left axilla and 56×51 mm in the

left neck, both with clear margins (Fig. 2B). Contrast-enhanced US (CEUS)

demonstrated no enhancement in the early or late phases of

enhancement in the axillary and neck masses. A 1-month follow-up US

revealed the presence of a newly discovered mass, measuring ~33×35

mm in size, located just superior to the left neck ablation

foci.

In January 2021, due to the continuous new

occurrence and substantial volume of the metastasis tumors, MWA

alone was considered insufficient for inactivation. To achieve

further disease control, the patient underwent 125I RSI

for left neck masses. This decision balanced the lesion's critical

location abutting the carotid artery (Fig. 2A), the patient's explicit

chemotherapy refusal and the patient's frailty. RSI is not a

first-line treatment option for metastatic disease, but it has been

shown to be promising for refractory oligometastatic cases in

clinical practice (18).

Preoperative US identified two hypoechoic masses on the left neck,

measuring 54×40 mm and 40×32 mm, with CEUS showing partial necrosis

in the larger mass. A total of 58 125I particles

(physical dimension, 0.6 mm diameter; activity, 0.5 millicurie per

seed) were evenly distributed to the active region of the larger

mass, and 72 particles were evenly distributed to the other

mass.

A 1-month follow-up US revealed a reduction in the

size of the axillary ablation foci. The two neck masses had

decreased in size compared with previous measurements, displaying

clear margins and heterogeneous internal echoes with scattered

strong echogenic particles (Fig.

2C).

After 3 months, tumor indicators levels were as

follows: CEA, 1.55 ng/ml; CA19-9, 7.88 U/ml; and CA72-4, 2.24

IU/ml. All were within the normal range (Fig. 3A-C).

In March, April and June 2021, the patient underwent

the third, fourth and fifth sessions of MWA for neck masses,

respectively, targeting the residual active areas of the left neck

mass and suspicious lymph nodes for repeat ablation.

Outcome and follow-up

Following the last ablation procedure, the patient

returned to the hospital for follow-up at 3, 6, 30, 36, 42 and 47

months. The latest examination results were as follows: Physical

examination revealed smooth skin without redness or swelling and US

indicated the ablation foci had gradually absorbed and disappeared

completely (Fig. 2D). The tumor

markers remained within normal ranges. Flow cytometric analysis of

T cell subsets indicated that CD3+ levels consistently

remained high 2 years postoperatively (Fig. 3D).

Discussion

Due to the large number of metastatic tumors and the

high tendency for recurrence, traditional surgical treatments

struggle to completely eradicate the advanced cancer. This has

become a notable challenge in treatment and a leading cause of

patient mortality, highlighting the refractory nature of metastatic

cancer. Consequently, the focus of treatment and research for

advanced metastatic GBC has shifted to systemic therapies. Among

these, the GemCis chemotherapy protocol, which combines gemcitabine

and cisplatin, has been widely adopted internationally (1). However, a notable number of patients

with advanced cancer choose to refrain from chemotherapy in

clinical practice due to physical and mental distress, economic

pressure and other reasons, instead choosing palliative

interventional therapies which are low-cost. In the present case,

the patient rejected postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy or

chemotherapy, and finally developed distant metastasis. The team

offered only local palliative treatment for the metastatic mass of

the patient, which unexpectedly achieved long-term systemic

remission. Interventional therapy can not only destroy local tumor

tissue but also activate the immune system of the body, which in

turn has a certain immune attack on the distant metastasis, being

consistent with the concept of in situ tumor vaccine. Based

on a comprehensive literature review (PubMed, Web of Science and

EMBASE up to July 2025), no prior case reports or studies have

specifically documented the use of sequential MWA combined with

¹25I-RSI for metastatic GBC.

MWA is a technique that directly utilized thermal

energy to kill tumor cells in situ (19). Previous research has demonstrated

that thermal ablation can induce abscopal effects (9). This is a rare clinical response that

refers to tumor regression or growth at a site distant from

ablation or irradiation site. The abscopal response resulting from

MWA is seldom reported. However, in the present case, the patient

did not receive any systemic therapy prior to metastasis and had a

long postoperative follow-up period of 30 months. Thus, the

immunological mechanism of the abscopal effect warrants discussion.

Natural killer cells, which are effector lymphocytes of the innate

immune system and part of the first line of defense against cancer,

can be activated by MWA to promote the destruction of tumor cells

(20). Subsequently, residual

antigens remain in the tumor site (21). These antigens can release

inflammatory mediators, damage associated molecular patterns, and

immune regulatory factors (such as IL-1, IL-6 and HSP70) (22). Dendritic cells (DCs) phagocytose

antigens, present them on major histocompatibility complex

molecules and display co-stimulatory factors, thereby stimulating T

cells to generate adaptive immune responses and change the TME for

antitumor effects (9). In the

peripheral blood, a previous study reported that B cells are

notable antigen-presenting cells in the MWA-induced systemic

response (23).

In the present case, the patient was also treated

with a single RSI due to the repeated progression of the disease.

This treatment approach could create a favorable immune environment

for tumor in situ vaccines. Radioactive 125I

seeds are implanted into tumors to emit large doses of γ rays at

close range to destroy tumor cells without damaging normal tissues

(24,25). RSI is increasingly used in the local

treatment of tumors and has been utilized in the treatment of

various recurrent and refractory tumors (26–30).

RSI can trigger immunogenic tumor cell death. Tumor cells express

molecules that promote phagocytosis of cancer cells by surface DCs,

such as calreticulin, and release molecules that trigger ingested

antigen processing and cross-presentation, such as high mobility

group box 1 protein. This process promotes DC cross-presentation of

tumor antigens, altering the TME and generating antitumor immune

responses (31). A previous study

showed that RT can induce pyroptosis in tumor cells, resulting in

the release of cellular contents from tumor cells, causing an

inflammatory response and activating the immune system (32). RT can also induce abscopal effects.

Siva et al (33) reported 10

cases of abscopal effects after radiotherapy, and their median

duration was 21 months (range, 3–54 months). While RSI demonstrates

notable potential, its physical application faces inherent

constraints in metastatic settings. The technique is primarily

suited for limited, accessible lesions due to technical challenges

in precise seed placement within numerous or sub-centimeter

metastases, with risks of migration and adjacent tissue damage

(25,28). For cervical applications similar to

the present case, radiation damage to adjacent nerves or vessels

remains a concern (27). In the

present case, however, US-guided precision prevented such

complications, underscoring its importance for high-risk

anatomy.

MWA can be utilized as an in situ tumor

vaccine to a certain extent, but due to the relatively weak

response induced by it, it needs to be combined with other

treatment methods. In the present case, initial MWA achieved

partial control, but disease progression necessitated combined RSI.

However, after 125I RSI treatment, the notable effect

was achieved, and the subsequent ablation effect was greatly

enhanced. We hypothesize that the TME was transformed from an

immunosuppressive state to an immune activation state after RSI,

which provided a favorable immune environment for tumor treatment.

While immune checkpoint dynamics (such as programmed cell death

protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1) were not assessed in the

present study, their role in modulating abscopal responses warrants

investigation in future GBC studies (34).

Furthermore, the patient's peripheral blood T cell

subsets demonstrated a continuous increase in CD3+

levels. Notably, the CD3+ T-cell elevation persisted for

>30 months, substantially exceeding the typical duration of

acute inflammatory responses to cellular debris. Its temporal

association with complete clinical remission of all metastatic

lesions (47 months) and sustained normalization of tumor markers

strongly argues against non-specific inflammation (22), instead supporting a systemic

adaptive immune response. These findings align with the paradigm of

adaptive immune memory induced by in situ vaccination

(35,36), whereby localized tumor destruction

(via MWA/RSI) releases tumor-associated antigens, reprograms the

immunosuppressive microenvironment (16,31)

and potentiates sustained immunosurveillance mediated by

antigen-experienced T cells. While definitive proof of

tumor-specific immunity (such as T cell receptor sequencing or

cytotoxic assays) is lacking and remains unavailable due to the

retrospective nature of the present study, three concordant

observations strongly suggest abscopal immunity mediated by in

situ vaccination: i) Sustained CD3+ lymphocytosis;

ii) unprecedented disease control >47 months; and iii) durable

normalization of serum tumor markers. This clinical-immunological

profile provides compelling evidence consistent with long-term

immune memory formation.

The translation importance of the present case is

threefold: i) It challenges the therapeutic nihilism for advanced

GBC by demonstrating that sequential local interventions alone can

achieve durable systemic remission, offering hope for

chemotherapy-ineligible patients; ii) it provides the first

clinical evidence that combining RSI (radiotherapy) with MWA

synergistically overcomes immunosuppression, effectively creating

an in situ vaccine against metastatic GBC; and iii) It

establishes a foundation for minimally invasive strategies to

convert palliative care into curative intent, with 47-month

disease-free survival exceeding historical medians by >300%.

However, as a single-case report, the present study lacks

statistical power to establish causal relationships. The

exceptional response observed may be influenced by unique patient

biology. Comprehensive immune profiling was not available. Future

prospective trials are needed to validate the findings.

The patient's entire disease course lasted 5 years

and 4 months, during which recurrence and metastasis occurred.

Based on the patient's poor condition, a sequential therapy

consisting of multiple local interventions was precisely and

appropriately employed, which ultimately resulted in a favorable

prognosis. In conclusion, while the present single case cannot

confirm efficacy, it provides clinical rationale for exploring

combined ablation-RSI as an immune-activating strategy in

metastatic GBC. Palliative interventional therapy may induce a

systemic effect and can enhance the survival rate of patients with

advanced multiple metastatic cancer. The mechanism of the systemic

antitumor immune response induced by such local treatments merits

further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by National Science Foundation

for Young Scientists of China (grant no. 82302208), Medical

Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (grant no.

H2023141), Social Development Program of Zhenjiang City (grant nos.

SH2023015 and SH2023019) and Medical Education Collaborative

Innovation Fund of Jiangsu University (grant nos. JDY2023005 and

JDY2023012).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WL made substantial contributions to the conception

of the work, analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and drafted

the manuscript. YC, SZ and MA contributed to the acquisition and

analysis of clinical data. HZ and YC contributed to the study

design and methodology. JB and JQ contributed to the data analysis

and interpretation. BC conceived and supervised the study,

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content, and approved the final version to be published. WL and JB

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of any potentially identifiable images

or data included in the present article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Roa JC, García P, Kapoor VK, Maithel SK,

Javle M and Koshiol J: Gallbladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

8:692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Levy AD, Murakata LA and Rohrmann CA Jr:

Gallbladder carcinoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation.

Radiographics. 21:295–314. 549–555. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hundal R and Shaffer EA: Gallbladder

cancer: Epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 6:99–109.

2014.

|

|

4

|

Margonis GA, Gani F, Buettner S, Amini N,

Sasaki K, Andreatos N, Ethun CG, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees K, et

al: Rates and patterns of recurrence after curative intent

resection for gallbladder cancer: A multi-institution analysis from

the US extra-hepatic biliary malignancy consortium. HPB (Oxford).

18:872–878. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jarnagin WR, Ruo L, Little SA, Klimstra D,

D'Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, Wagman R, Blumgart LH and Fong Y:

Patterns of initial disease recurrence after resection of

gallbladder carcinoma and hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Implications

for adjuvant therapeutic strategies. Cancer. 98:1689–1700. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D,

Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira

SP, et al: Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for

biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 362:1273–1281. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sun J, Xie TG, Ma ZY, Wu X and Li BL:

Current status and progress in laparoscopic surgery for gallbladder

carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 29:2369–2379. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Campbell WA IV and Makary MS: Advances in

image-guided ablation therapies for solid tumors. Cancers (Basel).

16:25602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Slovak R, Ludwig JM, Gettinger SN, Herbst

RS and Kim HS: Immuno-thermal ablations-boosting the anticancer

immune response. J Immunother Cancer. 5:782017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bäcklund M and Freedman J: Microwave

ablation and immune activation in the treatment of recurrent

colorectal lung metastases: A case report. Case Rep Oncol.

10:383–387. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xu H, Sun W, Kong Y, Huang Y, Wei Z, Zhang

L, Liang J and Ye X: Immune abscopal effect of microwave ablation

for lung metastases of endometrial carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther.

16:1718–1721. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shao C, Yang M, Pan Y, Xie D, Chen B, Ren

S and Zhou C: Case report: Abscopal effect of microwave ablation in

a patient with advanced squamous NSCLC and resistance to

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 12:6967492021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Jiang G, Song C, Xu Y, Wang S, Li H, Lu R,

Wang X, Chen R, Mao W and Zheng M: Recurrent lung adenocarcinoma

benefits from microwave ablation following multidisciplinary

treatments: A case with long-term survival. Front Surg.

9:10382192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Saxena M, van der Burg SH, Melief CJM and

Bhardwaj N: Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer.

21:360–378. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

He N and Jiang J: Contribution of immune

cells in synergistic anti-tumor effect of ablation and

immunotherapy. Transl Oncol. 40:1018592024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Takashima ME, Berg TJ and Morris ZS: The

effects of radiation dose heterogeneity on the tumor

microenvironment and anti-tumor immunity. Semin Radiat Oncol.

34:262–271. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zeng P, Shen D, Shu W, Min S, Shu M, Yao

X, Wang Y and Chen R: Identification of a novel peptide targeting

TIGIT to evaluate immunomodulation of 125I seed

brachytherapy in HCC by near-infrared fluorescence. Front Oncol.

13:11432662023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wang H, Shi HB, Qiang WG, Wang C, Sun B,

Yuan Y and Hu WW: CT-guided radioactive 125I seed

implantation for abdominal incision metastases of colorectal

cancer: Safety and efficacy in 17 patients. Clin Colorectal Cancer.

22:136–142. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chu KF and Dupuy DE: Thermal ablation of

tumours: Biological mechanisms and advances in therapy. Nat Rev

Cancer. 14:199–208. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yu M, Pan H, Che N, Li L, Wang C, Wang Y,

Ma G, Qian M, Liu J, Zheng M, et al: Microwave ablation of primary

breast cancer inhibits metastatic progression in model mice via

activation of natural killer cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 18:2153–2164.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

den Brok MH, Sutmuller RP, van der Voort

R, Bennink EJ, Figdor CG, Ruers TJ and Adema GJ: In situ tumor

ablation creates an antigen source for the generation of antitumor

immunity. Cancer Res. 64:4024–4029. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ahmad F, Gravante G, Bhardwaj N,

Strickland A, Basit R, West K, Sorge R, Dennison AR and Lloyd DM:

Changes in interleukin-1β and 6 after hepatic microwave tissue

ablation compared with radiofrequency, cryotherapy and surgical

resections. Am J Surg. 200:500–506. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhou W, Yu M, Mao X, Pan H, Tang X, Wang

J, Che N, Xie H, Ling L, Zhao Y, et al: Landscape of the peripheral

immune response induced by local microwave ablation in patients

with breast cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 9:e22000332022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kang F, Wu J, Hong L, Zhang P and Song J:

Iodine-125 seed inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of

cholangiocarcinoma cells by inducing the ROS/p53 axis. Funct Integr

Genomics. 24:1142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lu W, Du P, Yang C, Jiang F, Xie P, Yang

J, Zhang Z and Ma J: The effect of computed tomography-guided

125I radioactive particle implantation in treating

cancer and its pain. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 33:176–181.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sugawara A, Nakashima J, Kunieda E, Nagata

H, Mizuno R, Seki S, Shiraishi Y, Kouta R, Oya M and Shigematsu N:

Incidence of seed migration to the chest, abdomen, and pelvis after

transperineal interstitial prostate brachytherapy with loose (125)I

seeds. Radiat Oncol. 6:1302011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang G, Wu Z, Yu W, Lyu X, Wu W, Fan Y,

Wang Y, Zheng L, Huang M, Zhang Y, et al: Clinical application and

accuracy assessment of imaging-based surgical navigation guided

125I interstitial brachytherapy in deep head and neck regions. J

Radiat Res. 63:741–748. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ji Z, Ni Y, He C, Huo B, Liu S, Ma Y, Song

Y, Hu M, Zhang K, Wang Z, et al: Clinical outcomes of radioactive

seed brachytherapy and microwave ablation in inoperable stage I

non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 13:3753–3762.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen L, Zhu GY, Jin ZC, Zhong BY, Wang Y,

Lu J, Pan T, Teng GJ and Guo JH: Efficacy and safety of radioactive

125I seed implantation for patients with

oligo-recurrence soft tissue sarcomas. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

45:808–813. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zaorsky NG, Davis BJ, Nguyen PL, Showalter

TN, Hoskin PJ, Yoshioka Y, Morton GC and Horwitz EM: The evolution

of brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 14:415–439.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Charpentier M, Spada S, Van Nest SJ and

Demaria S: Radiation therapy-induced remodeling of the tumor immune

microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:737–747. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cao W, Chen G, Wu L, Yu KN, Sun M, Yang M,

Jiang Y, Jiang Y, Xu Y, Peng S and Han W: Ionizing radiation

triggers the antitumor immunity by inducing gasdermin E-mediated

pyroptosis in tumor cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

115:440–452. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Siva S, MacManus MP, Martin RF and Martin

OA: Abscopal effects of radiation therapy: A clinical review for

the radiobiologist. Cancer Lett. 356:82–90. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hashimoto K, Nishimura S, Shinyashiki Y,

Ito T, Kakinoki R and Akagi M: Clinicopathological assessment of

PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint expression in desmoid tumors. Eur J

Histochem. 67:36882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhou Y, Xu X, Ding J, Jing X, Wang F, Wang

Y and Wang P: Dynamic changes of T-cell subsets and their relation

with tumor recurrence after microwave ablation in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 14:40–45. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu Q, Sun Z and Chen L: Memory T cells:

Strategies for optimizing tumor immunotherapy. Protein Cell.

11:549–564. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|