Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS), a typical malignant bone tumor,

predominantly affects children and young adults. Notably progress

in the prevention and treatment of OS has been achieved through the

introduction of potential treatment approaches. However, the global

annual incidence of OS is ~3.4 cases per million population, with a

slight male predominance. Despite advancements in treatment, the

5-year survival rate for patients with localized disease is 60–70%,

which drops to 15–30% for those with metastatic or recurrent

disease. Mortality trends have shown an annual increase of

approximately 1.4% in certain populations (1–4). It

has also been reported that ~80% of patients with OS have high

programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) mRNA expression (5). Programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors have been evaluated in clinical

trials for the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas; however,

there has been no notable responses recorded in patients with

advanced OS (6). The success of

immunotherapy is highly dependent on the level of immune cells

within the microenvironment of the host (7,8).

Therefore, assessing the immunoreactivity of OS is crucial in

making decisions about individualized treatment.

Ferroptosis, a novel type of cell death, is

typically accompanied by high levels of lipid peroxidation and iron

build-up (9). It serves a role in

numerous key pathological processes, including the development and

incidence of cancer (10).

Moreover, a previous study reported that ferroptosis serves a core

role in modulating genes involved in tumor immune escape (11). For example, the absence of

glutathione peroxidase 4, a key regulator of ferroptosis, prevents

an increase in the levels of CD8+ and CD4+ T

cells (11). Hence, determination

of immune infiltration-related ferroptosis genes for cancer

immunoreactivity could reveal novel insights into OS treatment.

In the present study, a single-sample Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) was used to assign patients with OS

into two clusters. A risk model was constructed using two immune

infiltration-related ferroptosis genes.

Materials and methods

Data abstraction

Clinical and pathological data from 87 patients with

OS were retrieved from the Therapeutically Applicable Research to

Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) database (accession no.

phs000468.v22.p8) (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/target)

(12). Furthermore, the expression

profile of the GSE21257 dataset (13) was downloaded from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), which contains data

from 53 human OS tissues. The gene probes of the platform were

transformed to gene names by referencing the GPL10295 platform

(14).

OS subgroup determination based on

immune gene sets

The 29 immune-related gene sets encompass several

types of immune cells, functions and pathways, were obtained from a

previously published study by Nguyen et al (15). For each overall survival dataset

(TARGET-OS database, phs000468.v22.p8), the level of immune-cell

infiltration in cancers was estimated using ssGSEA with the

GSVApackage (bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GSVA.html)

in R language (R 4.2.2 with Bioconductor 3.16.). Subsequently,

tumor purity, immune score and stromal score were inferred using

the ESTIMATE R package [v1.0.13 Kosuke Yoshihara Lab (Academic)].

Consensus clustering and molecular subtyping were performed using

the ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ R package

[bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.htmlv1.68.0(Bioconductor

release 3.19)], based on the ssGSEA scores. K-means clustering,

spectral clustering and PCA-k-means clustering were each replicated

50 times, and the optimal clustering outcome was utilized.

Differential expression analysis

Gene expression data from RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq)

were normalized using the voom transformation prior to differential

expression analysis. The ‘limma’ R package was used to screen the

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between high immunity

(Immunity_H) and low immunity (Immunity_L) samples. DEGs were

identified based adjusted P<0.05 and (|log2FC|) >0.5. This

threshold was selected to capture moderate transcriptional changes

relevant to immune modulation in OS, where subtle gene expression

variations may markedly impact biological pathways. Whilst

stringent cutoffs (such as |log2FC| >1) are common, studies

indicate that immune-related genes often exhibit smaller yet

functionally critical expression shifts in tumor microenvironments

(16–18).

Moreover, the ‘pheatmap’ R package was used to plot

heatmaps, whilst ‘ggpubr’ was used to generate boxplots. FerrDb

(http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/) and

PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were used to obtain

data on the 283 ferroptosis genes. For each of the DEGs and

ferroptosis genes, a Venn diagram was used for overlapping.

Development of a prognostic model

based on ferroptosis genes

Prognosis-related ferroptosis genes were identified

using the univariate Cox regression (UCR) model. Subsequently, the

expression levels of these genes were combined, and the estimated

regression coefficients were used to calculate prognostic scores

for each patient. The following formula was utilized to determine

the risk score for each patient: Risk score=β1×1 + β2×2 + … + βixi.

Subsequently, based on the median risk score as the cut-off value,

samples were divided into high- and low-risk groups. The

Kaplan-Meier (K-M) method was employed to determine the survival

rates in each group. Variables were included in both UCR and

multivariate Cox regression (MCR) analyses to assess the

independence of the risk variables. Receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the accuracy and

specificity of the signature associated with immune

infiltration-related ferroptosis genes.

Gene ontology (GO) annotation and

pathway enrichment analysis

RStudio software (version 4.2; Posit Software, PBC;

rstudio.com/) was utilized to perform mRNA GO enrichment and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) functional analyses.

CIBERSORT estimation

CIBERSORT estimates the abundance ratios based on

gene expression data from several cell types within a mixed cell

population (19,20). In the present study, the CIBERSORT

algorithm was utilized to measure the percentage of immune cells.

Subsequently, patients were categorized into low- and high-risk

groups based on prognostic risk score for overall survival.

Gene set enrichment analysis

(GSEA)

GSEA was used to elucidate the different signaling

pathways between the two risk subgroups, and all datasets were used

for a GSEA using c2.cp.kegg.v7.0.symbols.gmt. Nominal P<0.05,

|normalized ES| Enrichment Score)>1 and false Discovery Rate)

q<0.25 were selected out.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug sensitivity data were retrieved from the

CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/). The R

packages, ‘impute’, ‘limma’, ‘ggplot2’ and ‘ggpubr’ were used for

data processing, statistical analysis and result visualization.

Quantification of gene expression

using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

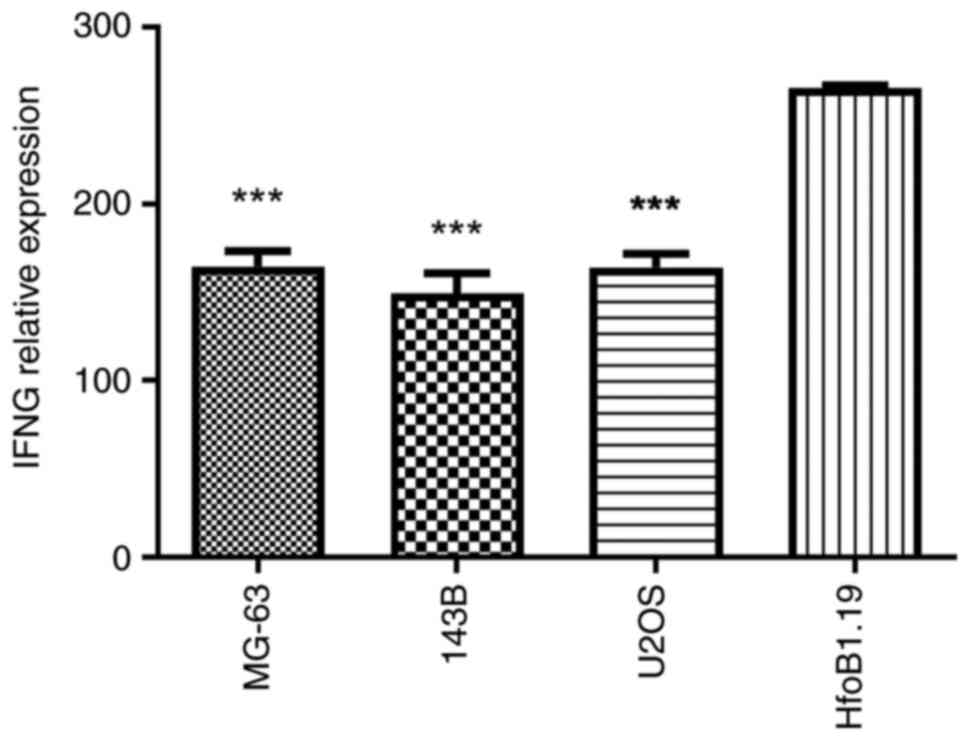

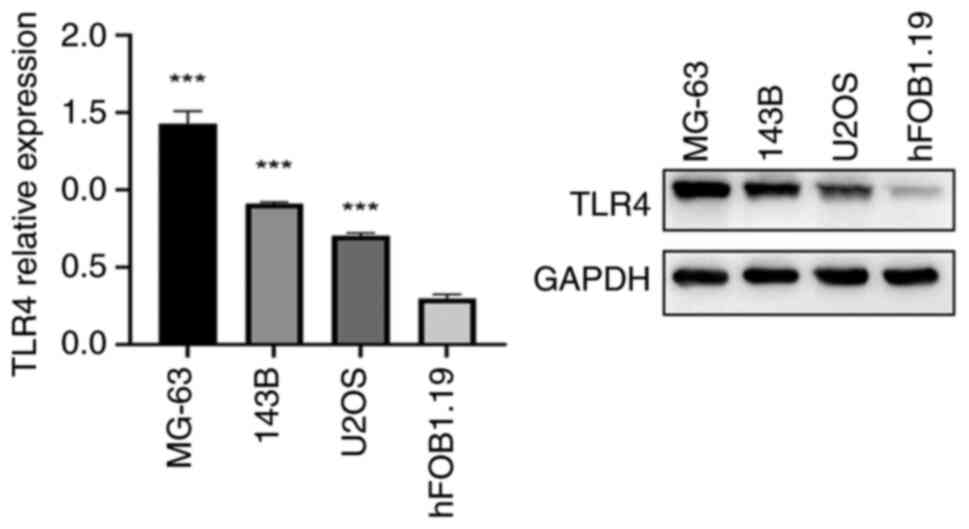

The relative mRNA expression levels of IFNG and

TLR4were measured in human OS cells lines, MG-63, 143B and U2OS,

and in the normal human osteoblast hFOB1.19 cell line. The hFOB1.19

cell line was maintained in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 34°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified

atmosphere. Moreover, The human OS cell lines MG-63 and 143B cells

(iCell Bioscience Inc.) were cultured in MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), while U2OS cells (iCell Bioscience Inc.) were

cultured in McCoy's 5A medium (cat. no. 16600082; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Both culture media were supplemented with

10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37°C with 5%

CO2 in a humidified environment.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and subsequently used to synthesize cDNA

with SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase

(Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

incorporating 5 µg oligo (dT) primers per sample. RT was performed

under the following temperature conditions: 25°C for 10 min (primer

annealing), followed by 42°C for 50 min (cDNA synthesis), and 70°C

for 15 min (enzyme inactivation). qPCR was performed using

SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied

Biosystems®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a total

volume of 20 µl with the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The thermocycling

conditions were set at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of

95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 45 sec. Melt-curve analysis was used

to confirm the specificity of the amplification, and GAPDH served

as the endogenous control for normalization of the amount of total

RNA in each group. The relative gene expression was calculated in

fold change according to the 2−ΔΔCq method (21), repeated independently in triplicate.

The primer sequences were designed as follows: Interferon γ (IFNG)

forward, 5′-TGCCTGCAATCTGAGCCAGT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGGAAGCACCAGGCATGAAA-3′; toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) forward,

5′-TAGCGAGCCACGCATTCACA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TAGGAACCACCTCCACGCAG-3′;

and GAPDH forward, 5′-GACCTGACCTGCCGTCTA-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGGAGTGGGTGTCGCTGT-3′.

Authentication testing of the MG-63, 143B, U2OS and

hFOB1.19 cell lines was performed (Shanghai Biowing Applied

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) via short tandem repeat (STR) profiling.

The STR profiles matched the standards recommended for the

authentication of the MG-63, 143B, U2OS and hFOB1.19 cell

lines.

Semi-quantification of gene expression

using western blot analysis

Total proteins extracted from human OS (MG-63, 143B

and U2OS) and the normal human osteoblast hFOB1.19 cell line were

harvested using ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride for 1 h. Following the

manufacturer's instructions, a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merch KGaA) was used to determine the amount of

protein. A total of 20 µg protein/lane was separated on 12%

SDS-PAGE (Beyotime Biotechnology) and transferred onto PVDF

membranes (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). The membranes were blocked

with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h, and washed in

Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 [150 mmol/l NaCl (pH 7.5), 20 mmol/l

Tris-HCl and 0.1% Tween 20] at room temperature three times.

Primary monoclonal antibodies against TLR4 (1:1,000; cat. no.

BA1717; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) and the loading

control, GAPDH (1:10,000; cat. no. AB0037; Shanghai Abways

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were incubated with the membranes

overnight at 4°C. Membranes were incubated with horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody

(1:10,000 dilution; cat. no. BE0101; bioeasy) for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein bands were visualized using ECL) reagent (cat.

no. T4600; Tianneng Technologies) according to the manufacturer's

instructions.

Detection of IFNG expression using

ELISA

The levels of the anti-fibrotic factor IFNG in

MG-63, 143B, U2OS and normal human osteoblasts were assessed using

the Human Interferon γ ELISA Kit (cat. no. H0108c; Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism (version 8.0; Dotmatics) or SPSS (version 24.0; IBM Corp.).

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3

independent experimental repeats. For linear correlation, Pearson's

correlation coefficient was used. Comparisons between multiple

groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed

by Tukey's post hoc test. Overall survival was determined using K-M

survival curves along with the log-rank test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. For

comparisons between two groups, statistical significance was

assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed

data (immune cell infiltration proportions and immune checkpoint

gene expression). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Immune subtypes identified in OS

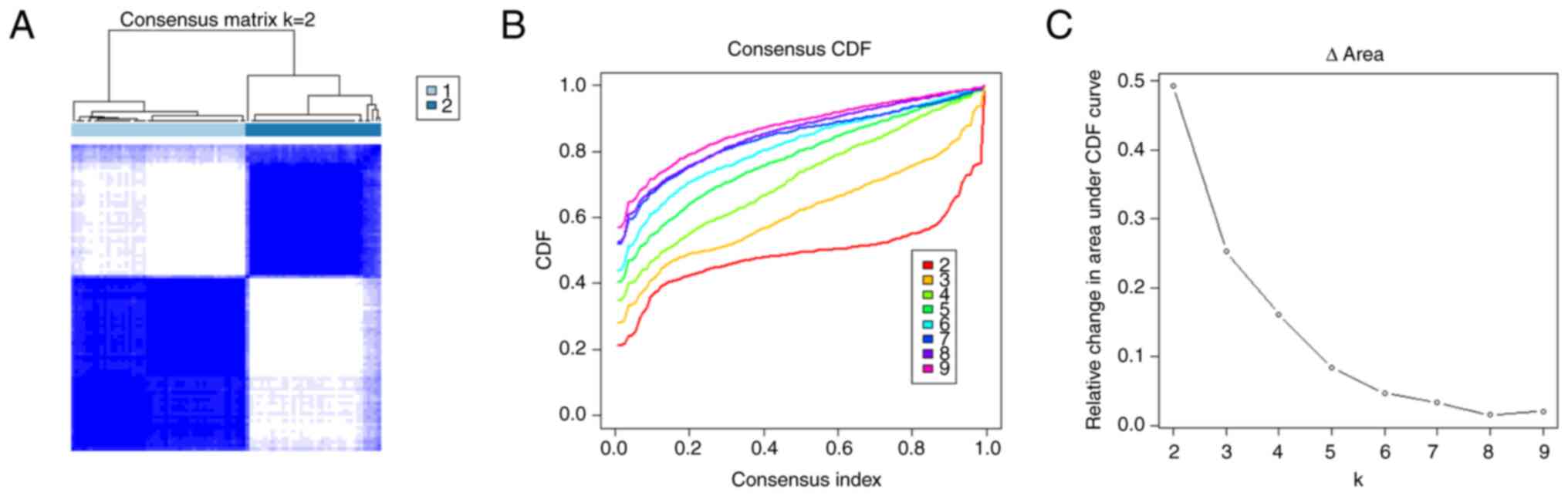

A total of 87 patients with OS were included in the

present study. ssGSEA was performed on each sample using gene sets

comprised of mRNA transcripts specific to most subpopulations of

both innate and adaptive immune cells. All tumor samples were

categorized into k subtypes, with k-values of 2–9. Based on the

consensus score of the cumulative distribution function curve, k=2

was determined to be the optimal number of subtypes (referred to as

Immunity_H and Immunity_L; Fig.

1).

Immune features of the three immune

subtypes

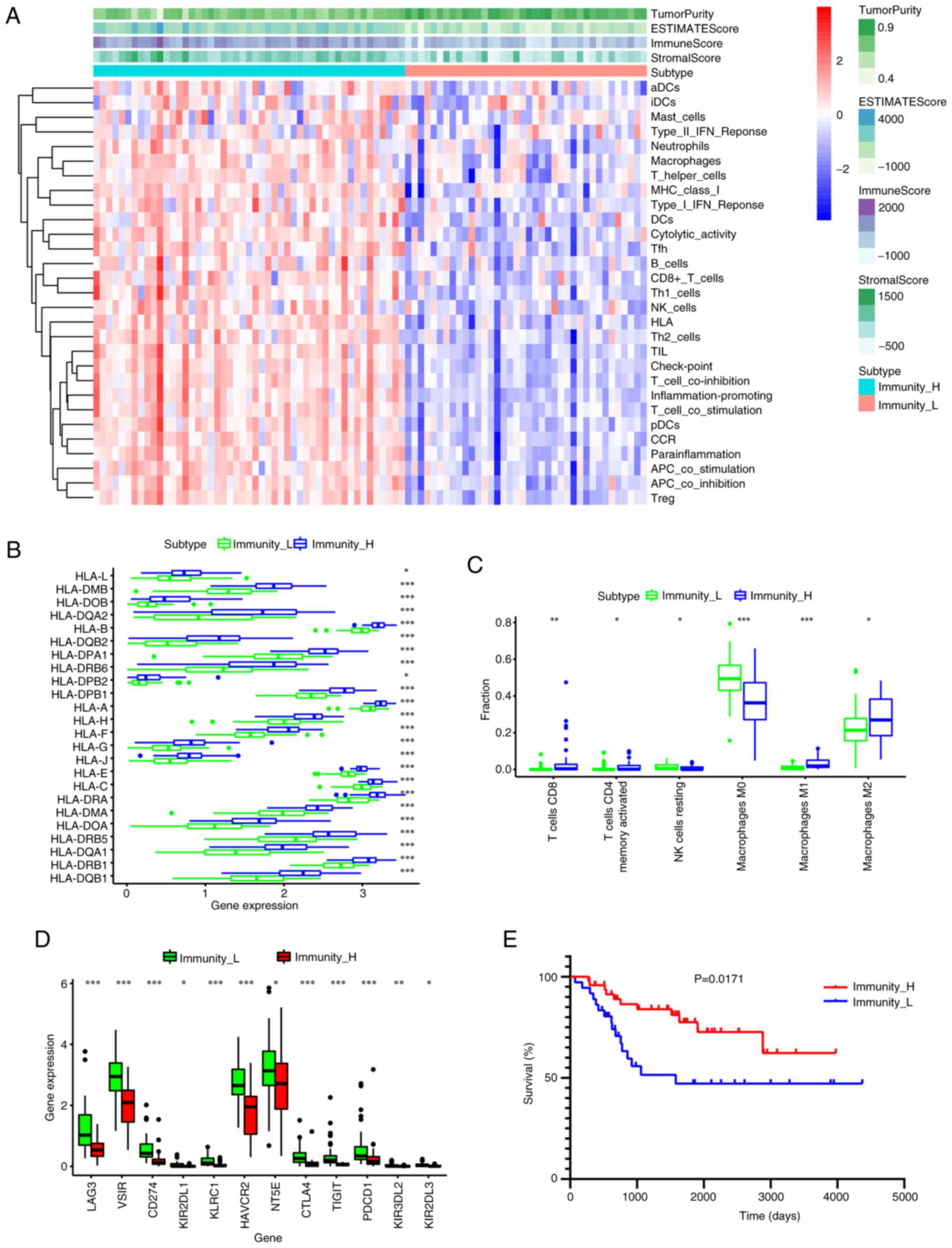

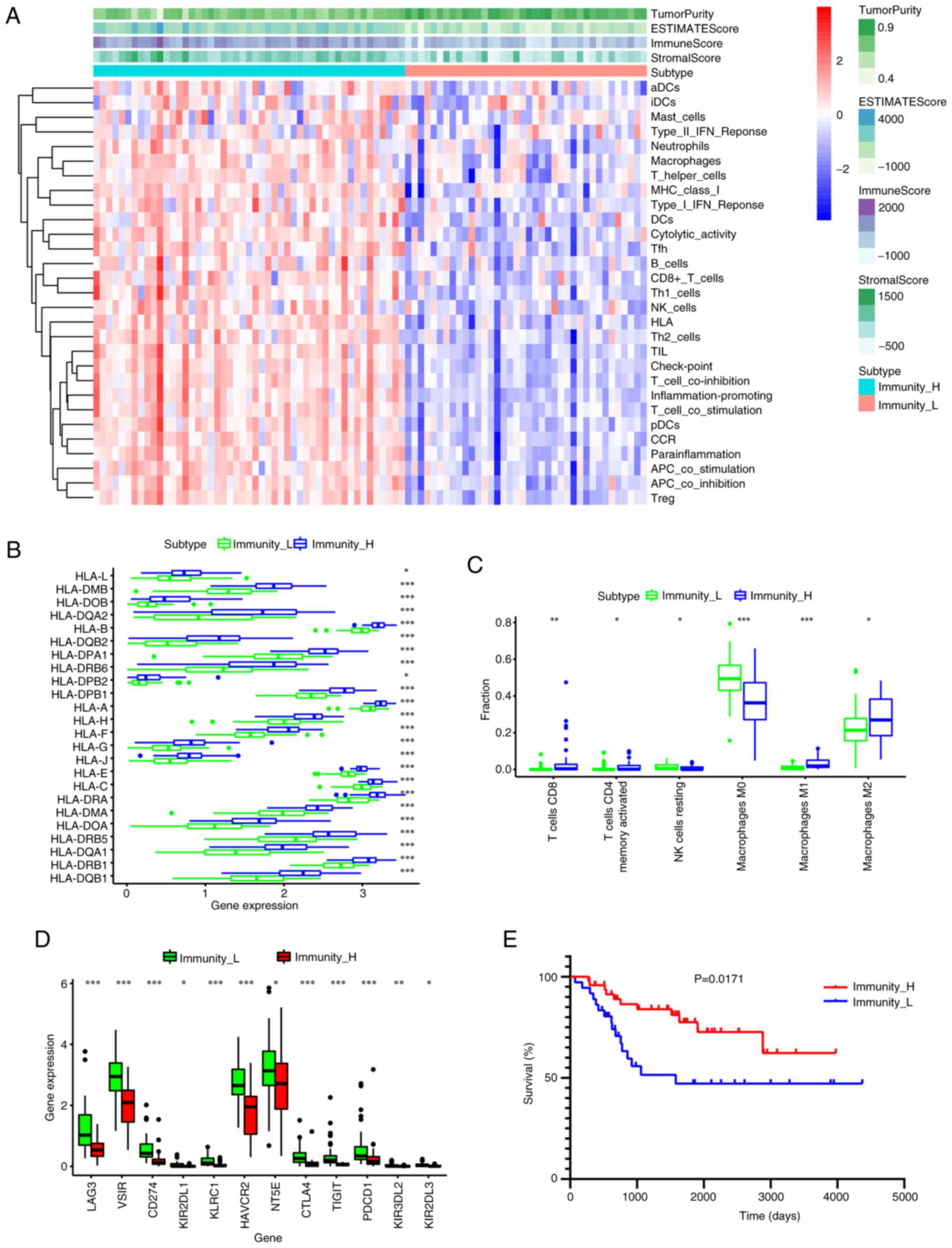

The ssGSEA clustering analysis indicated that the

extent of immune infiltration was higher in the Immunity_H group

than in the Immunity_L group (Fig.

2A). The overall survival cases in the Immunity_H group

exhibited significantly lower tumor purity and higher ESTIMATE,

stromal and immune scores compared with those in the Immunity_L

group (Fig. 2A; P<0.005).

Additionally, the expression of most human leukocyte antigens was

significantly higher in the high immune cell infiltration cluster

(Immunity_H group) compared with the low immune cell infiltration

cluster (Immunity_L group). (P<0.05; Fig. 2B). The Immunity_H subtype showed

significantly increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells,

memory activated CD4+ T cells, M2 macrophages and M1

macrophages compared with the Immunity_L subtype (P<0.05;

Fig. 2C). However, the Immunity_H

subtype exhibited significantly lower infiltration of M0

macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells resting compared with the

Immunity_L subtype (P<0.05; Fig.

2C). Furthermore, the expression of the following eight immune

checkpoint genes associated with immune escape were assessed:

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), V-set immunoregulatory

receptor, CD274, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2 (HAVCR2),

killer cell immunoglobulin like receptor (KIR)-two Ig domains and

long cytoplasmic tail 1, killer cell lectin like receptor C1,

5′-nucleotidase ecto, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

(CTLA4), T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT),

KIR-three Ig domains and long cytoplasmic tail 2, KIR-two Ig

domains and long cytoplasmic tail 3 and programmed cell death 1

(PDCD1). The expression levels of these genes were significantly

higher in the Immunity_H group than in Immunity_L group (P<0.05;

Fig. 2D). Finally, K-M analysis

indicated that patients with OS in the Immunity_H cluster had a

significantly improved survival rate compared with those in the

Immunity_L cluster (P=0.0171; Fig.

2E).

| Figure 2.Determination of the two immune

subtypes in osteosarcoma. (A) Heatmap of single-sample Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis scores. (B) There was a significant difference

in the expression of most HLAs between the high- and low-immune

cell infiltration clusters. (C) Difference in the expression levels

of infiltrating immune cells between the two clusters. (D)

Difference in the expression levels of the immune checkpoint genes,

LAG3, VSIR, CD274, HAVCR2, NT5E, CTLA4, TIGIT and PDCD1, among the

two subtypes. (E) Patients in low immune cell infiltration cluster

showed worse overall survival than those in high immune cell

infiltration cluster. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005. LAG3,

lymphocyte-activation gene 3; VSIR, V-set immunoregulatory

receptor; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; NT5E,

5′-nucleotidase ecto; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated

protein 4; TIGIT, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains;

PDCD1, programmed cell death 1. |

Identification of DEGs and functional

enrichment analyses

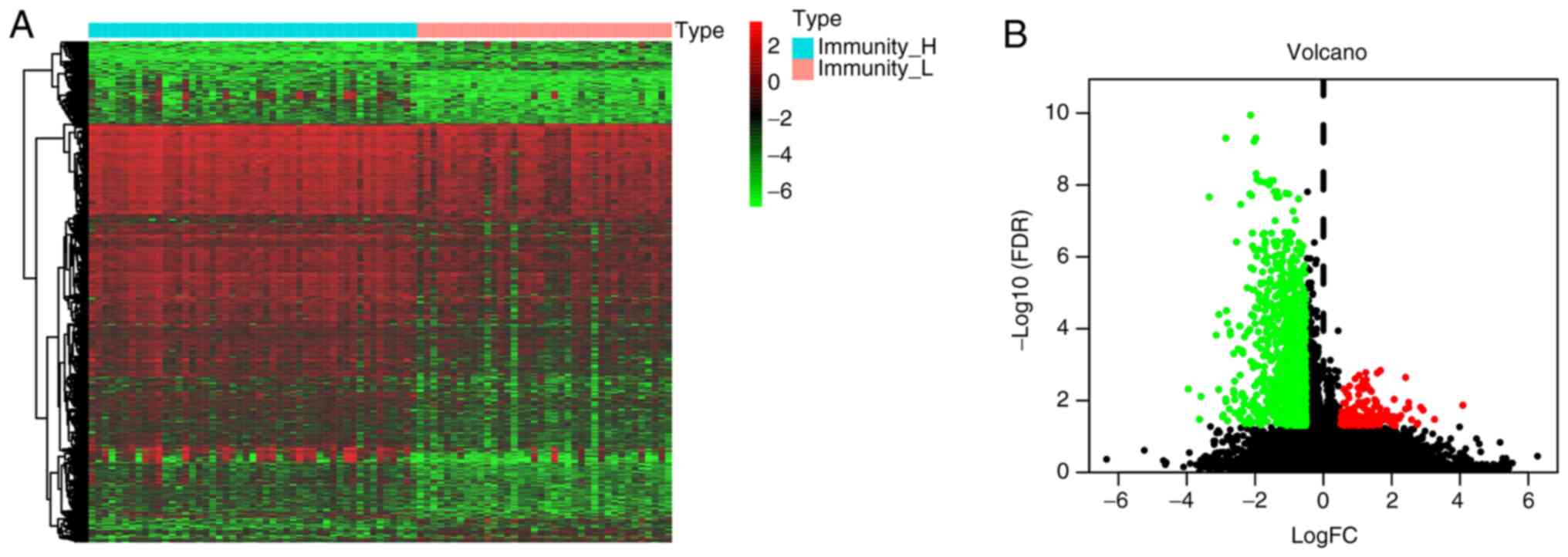

The results revealed that Immunity_H represents an

immune-infiltration cluster, whilst Immunity_L signifies a cluster

with low immune cell infiltration. Consequently, differentially

expressed immune infiltration-related genes were identified from

both Immunity_H and Immunity_L groups. In total, 1,240 DEGs were

identified, comprising 159 upregulated genes and 1,081

downregulated genes (Fig. 3).

Immune infiltration-related

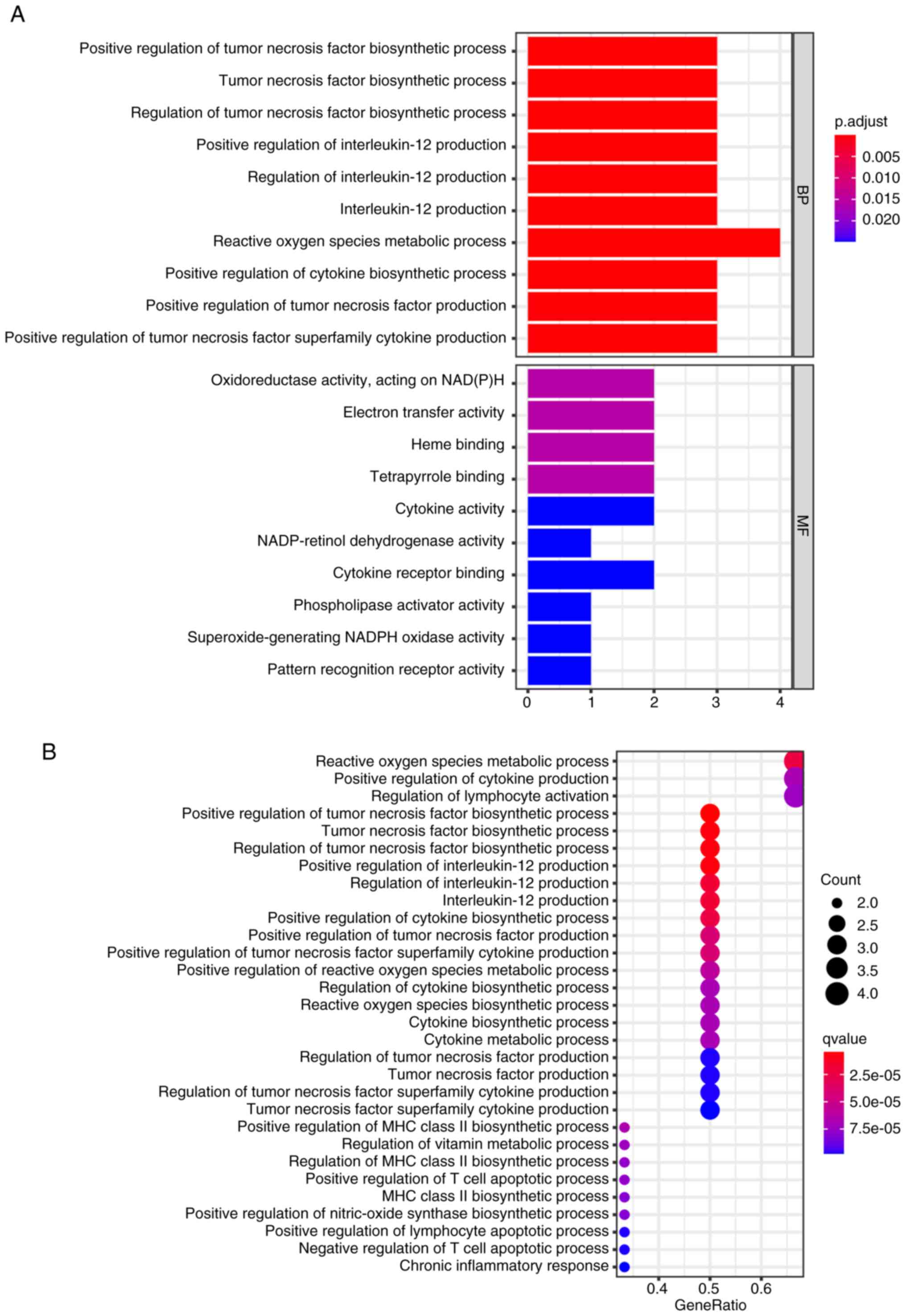

ferroptosis genes and functional enrichment analyses

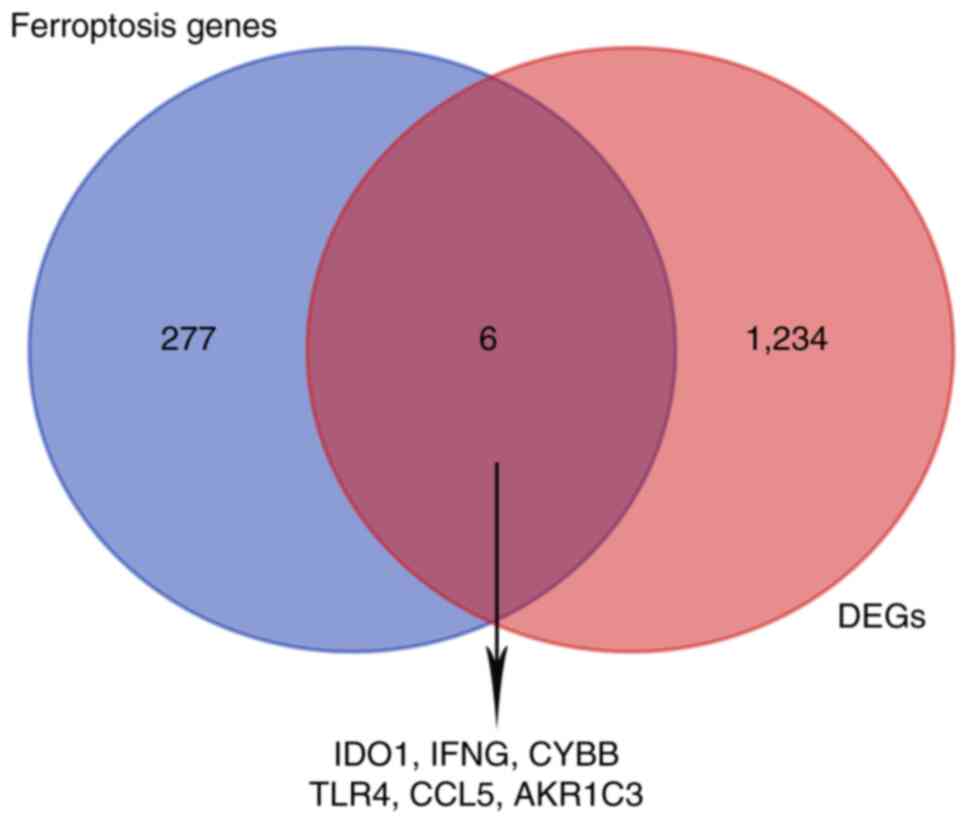

Immune infiltration-related genes that were

differentially expressed were intersected with 283 ferroptosis

genes. A total of six overlapping genes were screened for

subsequent analyses (Fig. 4).

Additional investigations were performed into the potential

functions of the genes by employing GO and KEGG analyses. The GO

terms were mainly enriched in positive regulation of the tumor

necrosis factor biosynthetic process, reactive oxygen species

metabolic process, regulation of tumor necrosis factor biosynthetic

process and positive regulation of interleukin-12 production

(Fig. 5A). Additionally, the KEGG

pathway analysis (Fig. 5B)

demonstrated that the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 signaling pathway,

nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor

signaling pathway in cancer, PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint

pathway were also enriched in the PD-L1-positive and toll-like

receptor-signaling pathways (Fig.

5B). The results indicate that the inflammatory and

immunological responses may be involved in the development of OS

tumorigenesis.

Construction of the diagnostic and

prognosis model based on two ferroptosis genes

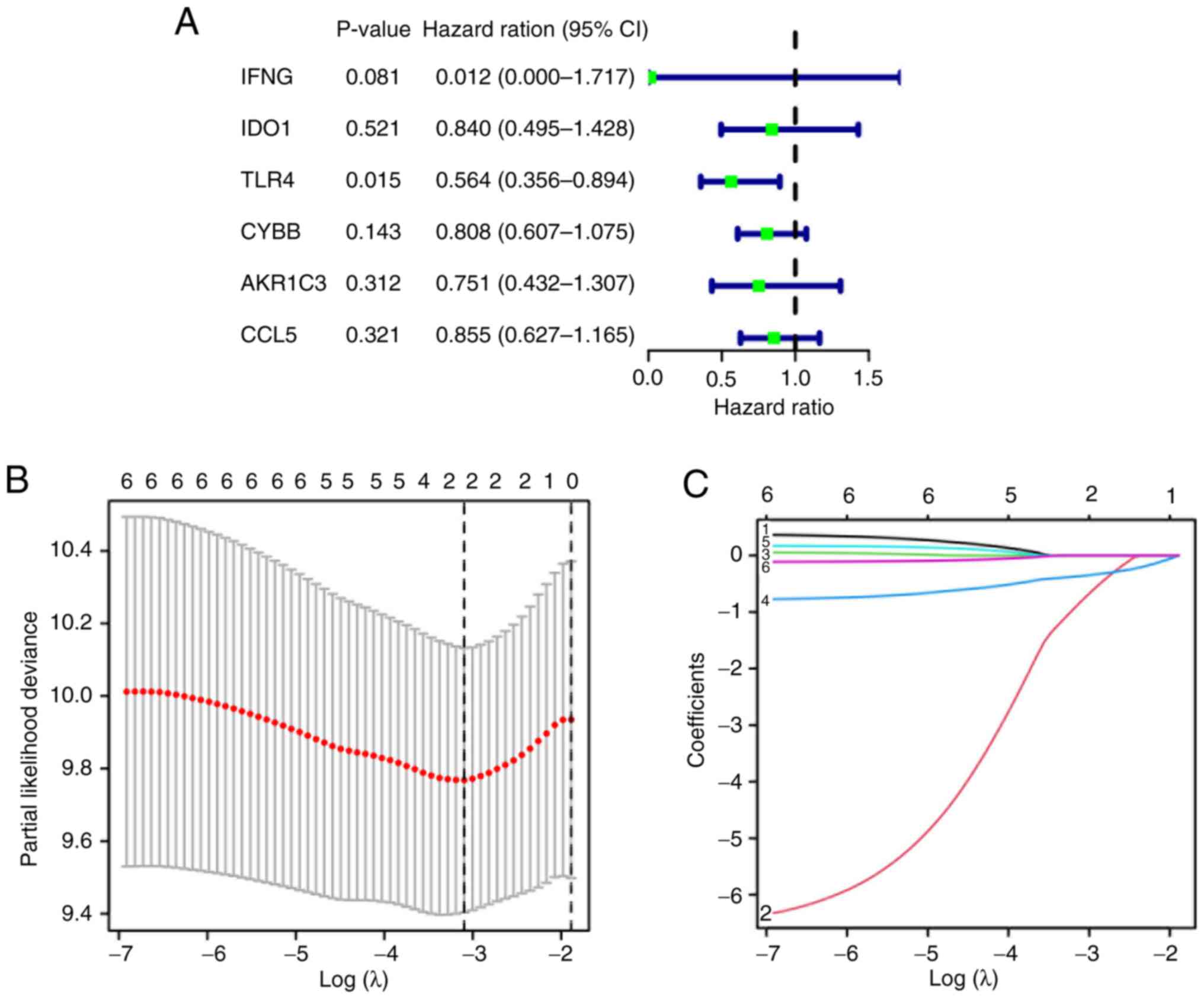

UCR analysis was performed with OS prognosis as the

dependent variable, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. TLR4 was revealed to have a

notable association with overall survival (P<0.05; Fig. 6A). Subsequently, Least Absolute

Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression analysis

identified two genes, IFNG and TLR4 (Fig. 6B and C). After which, a prognostic

signature was developed based on the following formula: Risk

score=(−0.3623 × TLR4 expression value) + (−0.8072 × IFNG

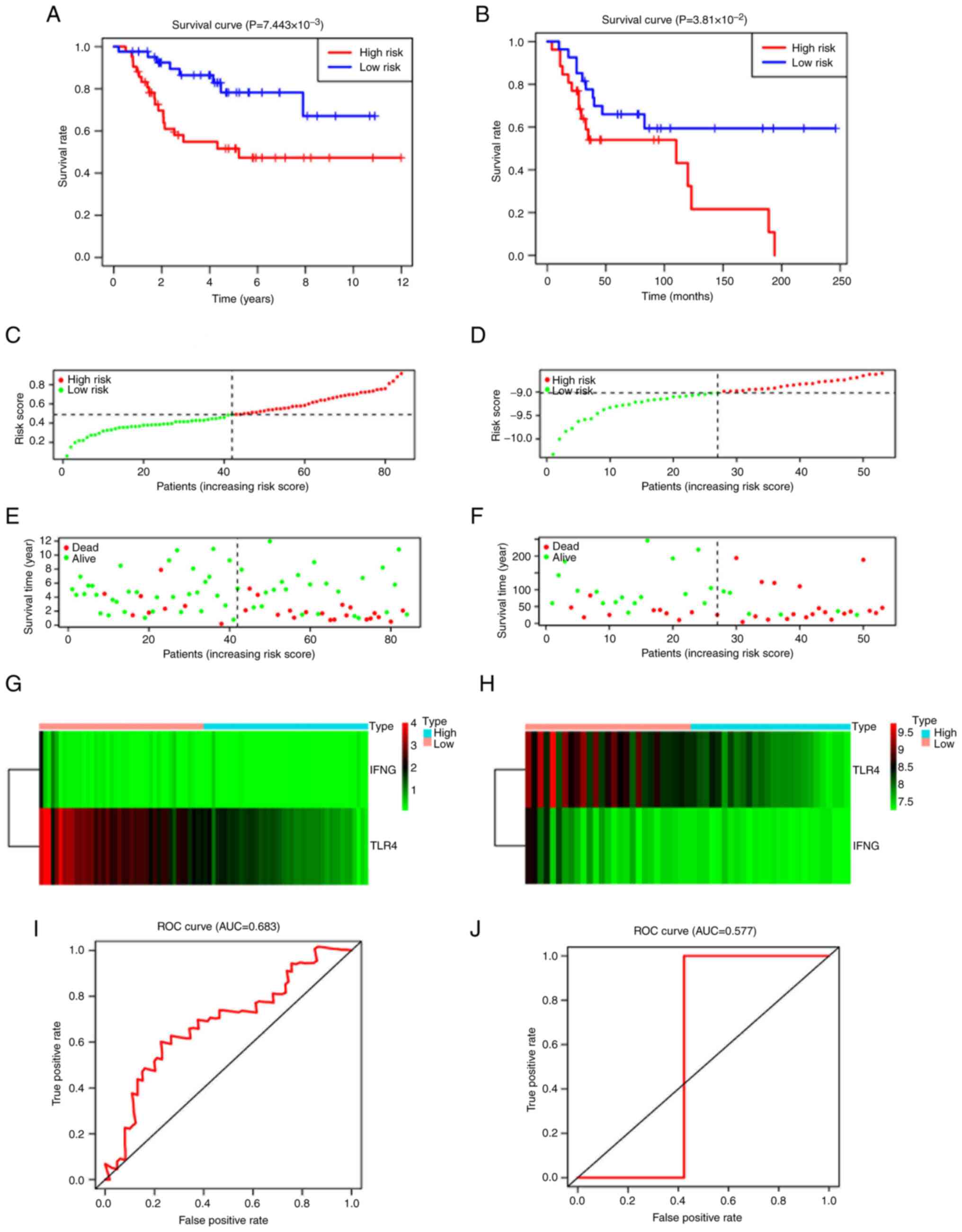

expression value). Patients were stratified into high-(n=43) and

low-(n=44) risk groups. The high-risk group exhibited a

significantly worse prognosis compared with the low-risk group

(P=7.443×10−3; Fig. 7A).

Moreover, ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the Cox prediction

model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.683 for survival

prediction at 3 years (Fig. 7I),

showing improved accuracy and suggesting moderate predictive

capability. The riskScore plot, status plot and the expression of

the two signature genes are presented in Fig. 7C, E and G. The GEO dataset was then

used to assess the robustness of the model. Compared with patients

in the low-risk group, patients in the higher risk group had a

shorter survival period, which was in-line with the previous

results (P=7.443×10−3; Fig.

7B); the AUC of ROC was 0.577 (Fig.

7J). The detailed risk scores, status plot and

ferroptosis-related gene expression are presented in Fig. 7B, D, F and H.

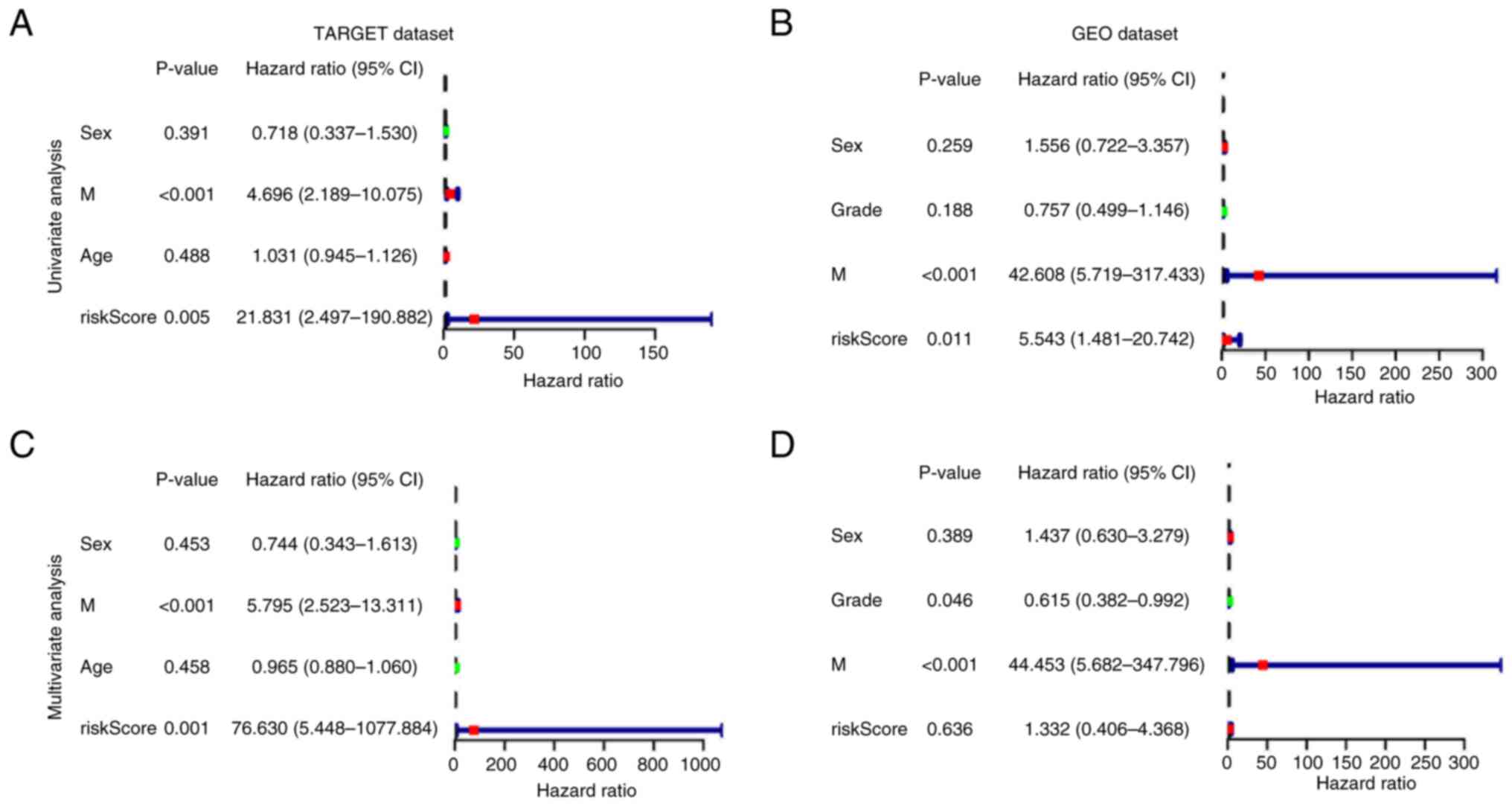

Additionally, to assess whether the signature was

independent of other clinical characteristics, UCR and MCR analyses

were performed in two cohorts. UCR indicated that the metastasis

status and risk score had a significant influence on prognosis in

both datasets (Fig. 8A and B). In

MCR analysis, the risk score derived from the signature was an

independent prognostic factor in the TARGET cohort [hazard ratio

(HR), 76.630; 95% confidence interval (CI), 5.448–1077.884;

P<0.001]. However, the risk score was not an independent

prognostic factor in the GEO cohort (HR, 1.332; 95% CI,

0.406–4.368; P=0.636; Fig. 8C and

D); however, this may be due to the limited number of samples

used (n=53).

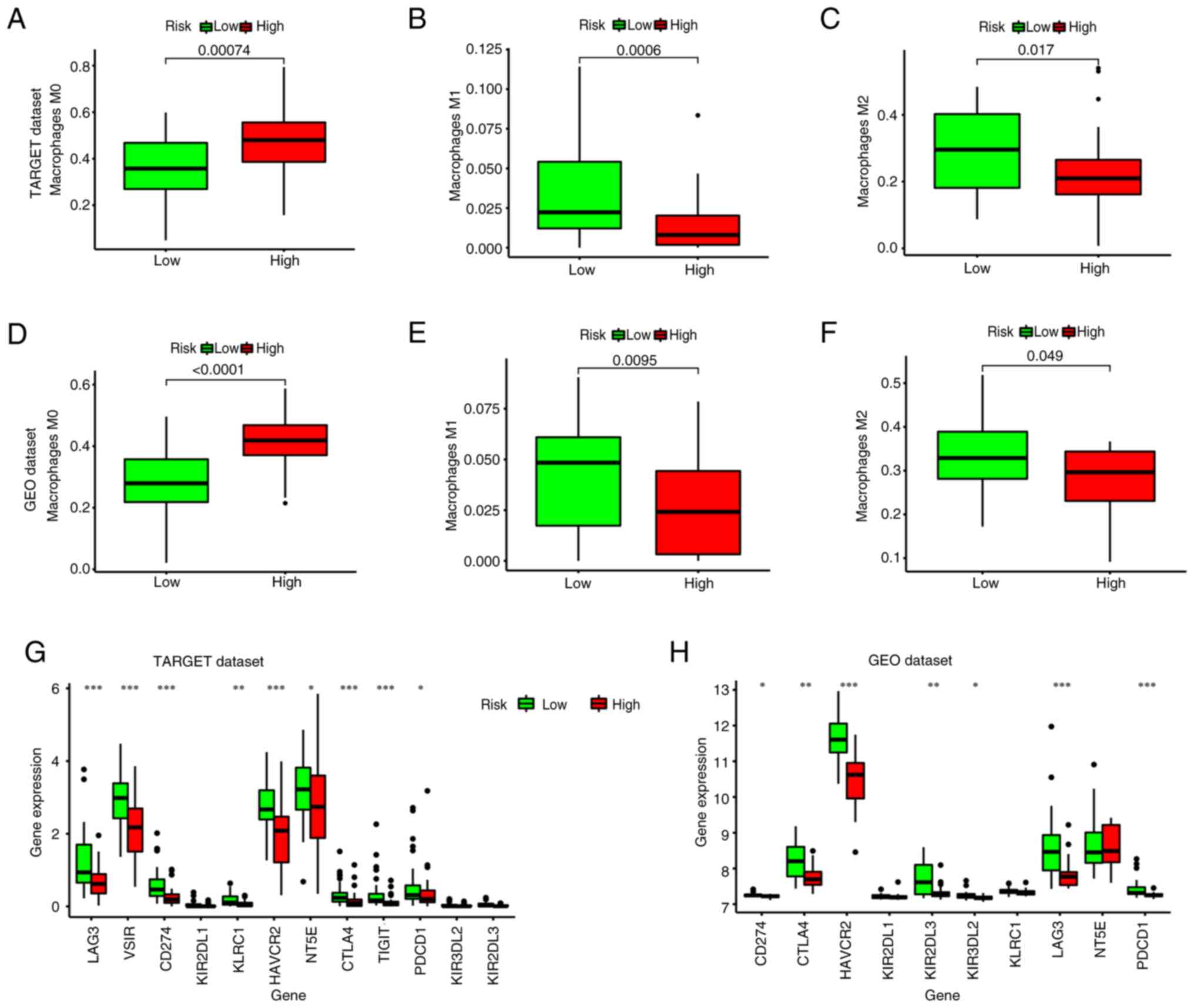

Assessment of the diverse

tumor-infiltrating immune cell (TIIC) types between low- and

high-risk cohorts

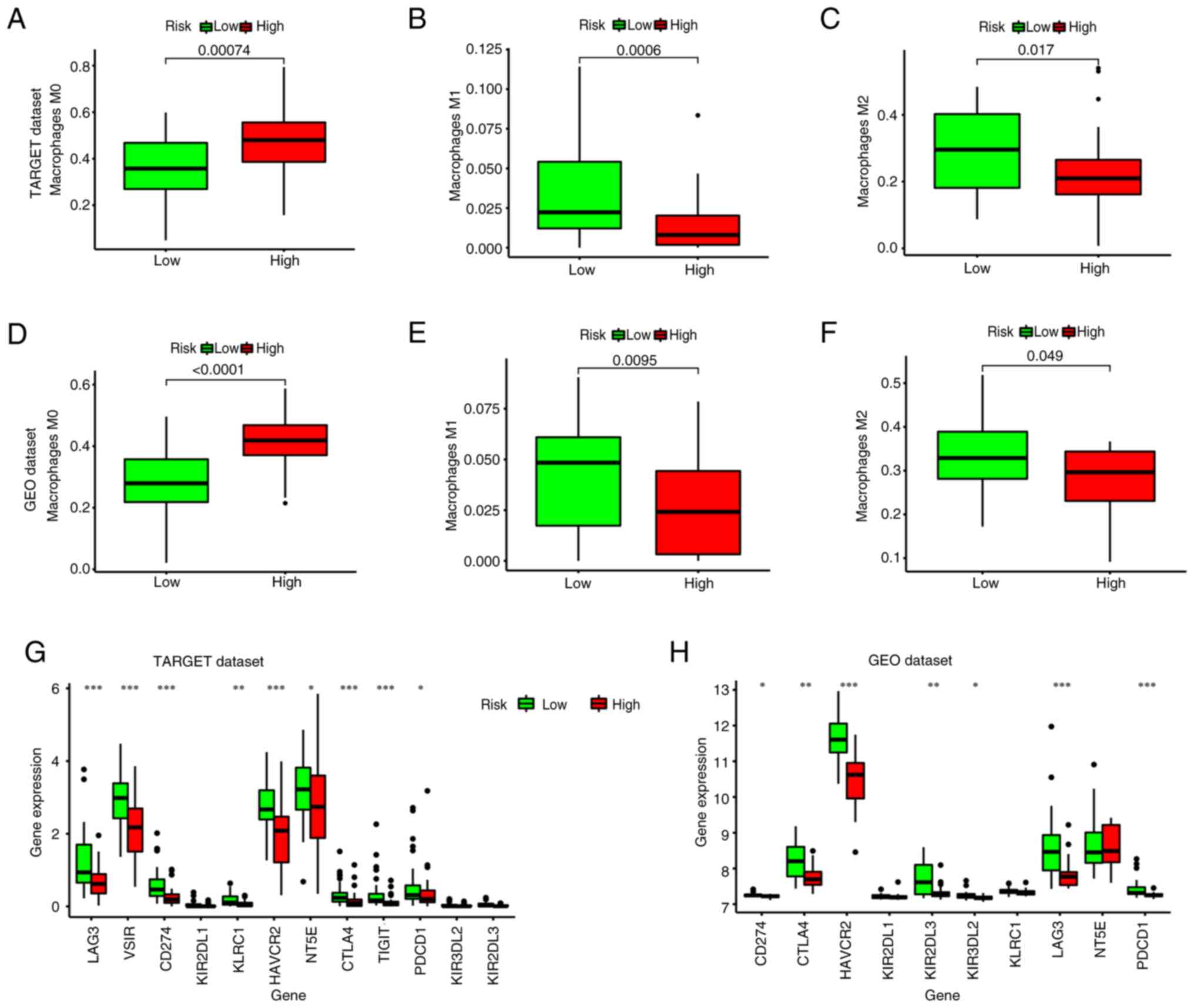

Using CIBERSORT, the immune infiltration percentage

of each cell type was calculated using the gene matrix as a basis.

In patients in the high-risk group, there was a significantly

increased number of M0 macrophages (P=0.00074; Fig. 9A). By contrast, the low-risk group

exhibited significantly higher levels of M1 macrophages (P=0.006;

Fig. 9B) and M2 macrophages

(P=0.017; Fig. 9C). Furthermore,

the expression of immune checkpoint genes in the low-risk group,

including LAG3, CD274, CTLA4, HAVCR2, TIGIT, HAVCR2 and PDCD1 was

higher than that in the high-risk group (P<0.05; Fig. 9G). Additionally, consistent results

were obtained using the GEO cohort (Fig. 9D-F and H; P<0.005).

| Figure 9.Analysis of immune cell infiltration

in patients with osteosarcoma. Differences in the number of (A) M0,

(B) M1 and (C) M2 macrophages between the high- and low-risk groups

in the TARGET dataset. Differences in the number of (D) M0, (E) M1

and (F) M2 macrophages between the high- and low-risk groups in the

GEO dataset. Differences in the expression of immune checkpoint

genes among the high- and low-risk groups in the (G) TARGET and (H)

GEO datasets. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005. TARGET,

Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective

Treatments; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; LAG3,

lymphocyte-activation gene 3; VSIR, V-set immunoregulatory

receptor; KIR2DL1, killer cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor, two Ig

domains, Long cytoplasmic tail, inhibitory receptor 1; KLRC1,

Killer cell Lectin-like Receptor subfamily C member 1; HAVCR2,

hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; NT5E, 5′-nucleotidase ecto;

CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; TIGIT, T cell

immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains; PDCD1, programmed cell

death 1. |

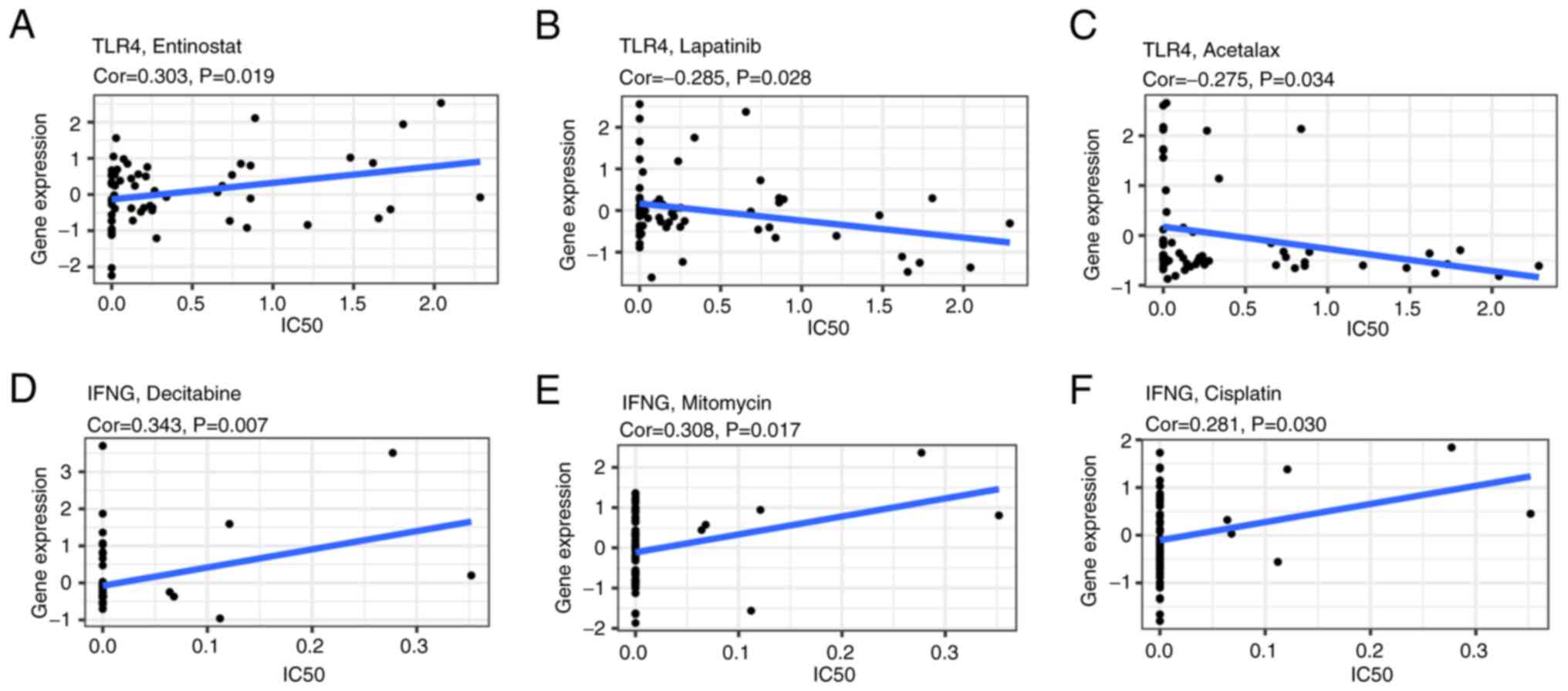

Drug sensitivity analysis of IFNG and

TLR4

To assess the underlying correlation between IFNG

and TLR4 gene expression and drug sensitivity in several human

cancer cell lines from the CellMiner database, a correlation

analysis was performed. TLR4 was demonstrated to be significantly

correlated with the drug sensitivity of entinostat (correlation

coefficient=0.303; P=0.019; Fig.

10A), lapatinib (correlation coefficient=−0.285; P=0.028;

Fig. 10B) and acetalax

(correlation coefficient=−0.275; P=0.034; Fig. 10C). Additionally, IFNG expression

was significantly correlated with the drug sensitivity of

decitabine (correlation coefficient=0.343; P=0.007; Fig. 10D), mitomycin (correlation

coefficient=0.308; P=0.017; Fig.

10E) and cisplatin (correlation coefficient=0.281; P=0.030;

Fig. 10F).

Association between risk and

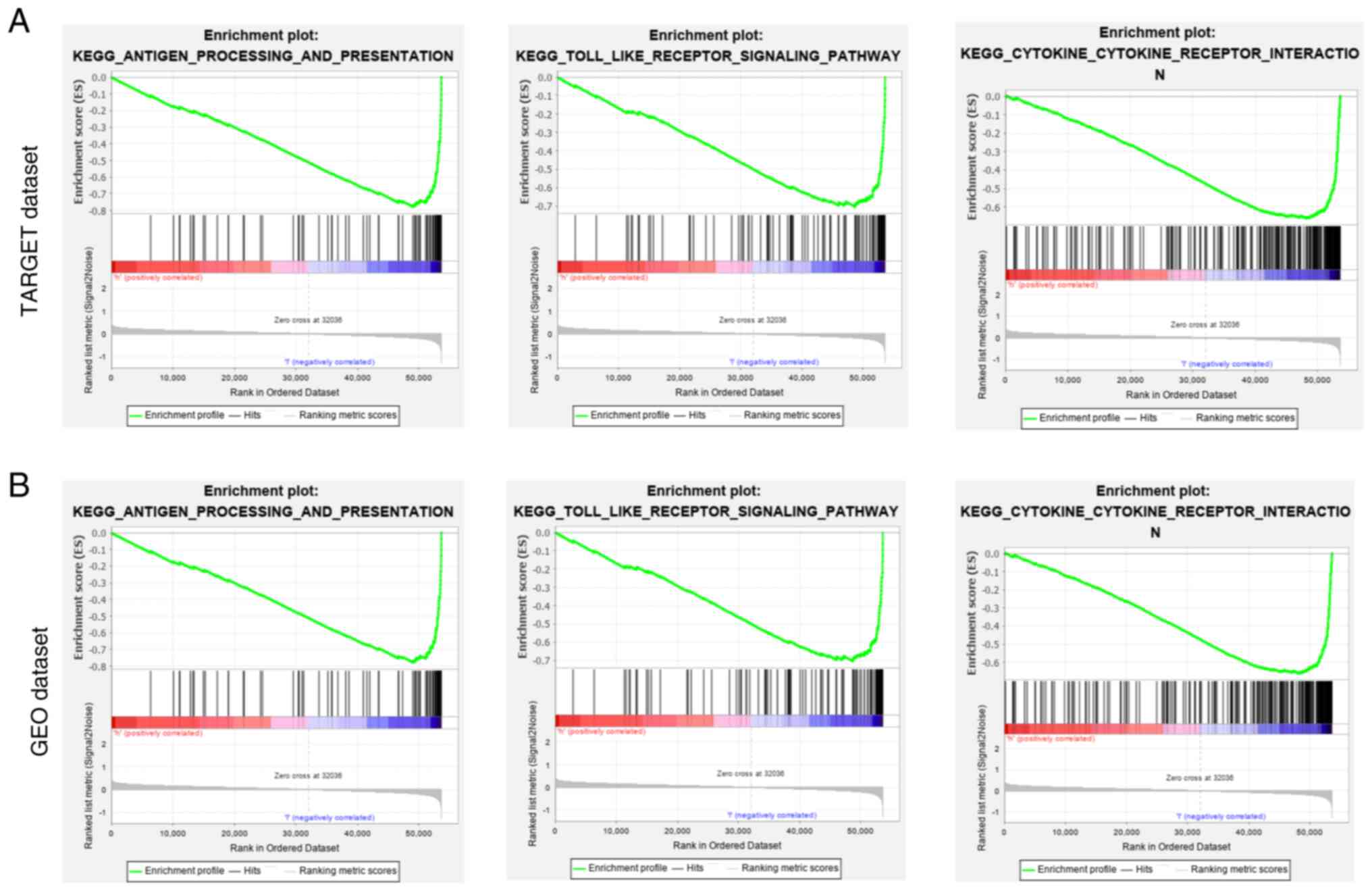

immune-related pathways

GSEA indicated that, compared with the low-risk

group, the high-risk group was negatively associated with

immune-related pathways, such as antigen processing and

presentation, the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway and

cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Fig. 11).

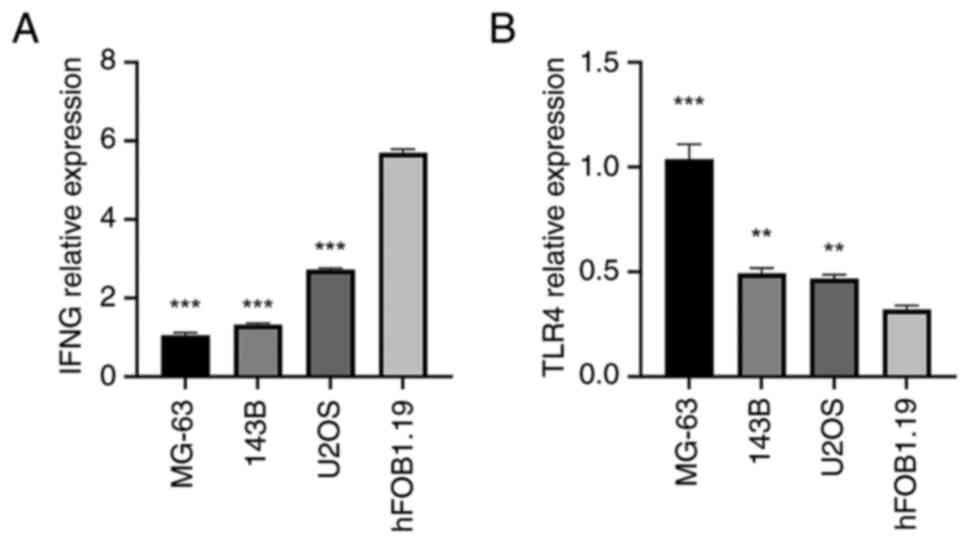

Validation of the expression level of

immune infiltration-related ferroptosis genes (IFNG and TLR4) in

hFOB1.19, MG-63, 143B and U2OS cell lines

To confirm that the two immune infiltration-related

ferroptosis genes, IFNG and TLR4, are specifically expressed in OS

cells, RT-qPCR was performed using the MG-63, 143B, U2OS and normal

human osteoblast (hFOB1.19) cell lines. Both IFNG and TLR4 were

expressed in MG-63, 143B and U2OS cells, with TLR4 expression

significantly higher in these OS cell lines than in hFOB1.19 cells.

By contrast, IFNG expression in the MG-63, 143B and U2OS cells was

significantly lower than in hFOB1.19 cells than in the OS cell

lines (Fig. 12). The same pattern

was observed in the results of the western blot analysis and ELISA

(Figs. 13 and 14). Consequently, this cellular

experiment corroborates the reliability of the bioinformatics

analysis results.

Discussion

Human OS, a primary malignant bone tumor, is most

prevalent during adolescence and in children (22). With the rapid development of

molecular biology technology, there has been a growing interest in

anticancer immunotherapies, including immune modulators, immune

checkpoint inhibitors and genetically modified T cells (23,24).

Patients with OS lacking immune cell infiltration present with high

rates of metastasis and poor clinical outcomes (25). Notably, immune reconstitution has

been reported to suppress OS recurrence and improve survival in

metastatic OS (26).

Recent studies have reported that

ferroptosis-related genes exhibit cell-type-specific expression in

immune cells, directly influencing their functional roles. TLR4 was

reported to be predominantly expressed in myeloid cells

(macrophages and dendritic cells). Moreover, its upregulation in M2

macrophages was reported to promote iron retention via ferritin

heavy chain 1 and suppress lipid peroxidation, enhancing

anti-inflammatory functions (27,28).

IFNG is secreted by activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells.

It induces tumor ferroptosis by downregulating the solute carrier

family 7 member 11/glutathione peroxidase 4 pathway whilst

upregulating acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4

(ACSL4) (29,30). In OS, TLR4 likely stabilizes iron

homeostasis in stromal macrophages, whilst IFNG from infiltrating T

cells sensitizes tumor cells to ferroptosis. This spatial crosstalk

creates a feed-forward loop where ferroptotic cells release

damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs; such as high-mobility

group box 1 (HMGB1)], further recruiting dendritic cells and

amplifying antitumor immunity (30–32).

Based on the immune signature score, patients with

OS were categorized into two clusters. Significant differences were

observed in tumor purity, ESTIMATE scores, stromal scores, immune

scores and the expression of immune checkpoint markers between the

Immunity_H and Immunity_L groups. Patients in the Immunity_H group

exhibited greater immune infiltration compared with those in the

Immunity_L group.

A prognosis model incorporating two

ferroptosis-related genes was utilized to develop a risk model for

predicting the overall survival of patients with OS. The risk score

was then used to classify patients into two distinct risk groups.

The reliability of the identified immune subtypes (Immunity_H/L)

was supported by the internal consensus clustering stability within

the TARGET cohort (Fig. 1). Whilst

the identical immunotyping procedure was not replicated on the

external GEO validation cohort due to platform heterogeneity, the

successful validation of the downstream immunotype-derived

ferroptosis prognostic model (IFNG/TLR4 risk score) in this

independent dataset (Fig. 7F-J)

provides indirect support for the biological relevance captured by

the initial subtyping approach. Furthermore, the K-M curve, score

plot, survival status plot and ROC curve indicated that the two

immune-related risk levels had a favorable predictive potential for

prognosis.

Notably, the multivariate Cox regression analysis,

incorporating clinical factors such as age, sex and metastasis

status, demonstrated that the ferroptosis-based risk score remained

an independent prognostic predictor in the primary cohort (TARGET),

suggesting its value beyond these potential confounders. However,

in the smaller GEO cohort, the risk score did not reach independent

significance in the multivariate model (P=0.636), which may be due

to the limited sample size (n=53).

To address how ferroptosis influences the tumor

immune microenvironment, the following mechanistic insights are

proposed based on recent studies: i) Ferroptosis modulates

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and T-cell activity; Lnk

deficiency in MDSCs triggers ferroptosis via the FMS-like tyrosine

kinase 3/STAT1/interferon regulatory factor-1/arachidonate

(12S)-lipoxygenase axis, reducing Arginase-1 expression and

increasing TNF-α, thereby weakening MDSC-mediated immunosuppression

(33). This aligns with the results

of the Immunity_H cluster (enriched in CD8+ T cells/M1

macrophages) and improved survival rates; ii) with a dual role in

T-cell function, CD8+ T cells promote tumor ferroptosis

via IFN-γ-mediated xCT suppression, but are themselves

vulnerable to ferroptosis due to ROS accumulation (34,35).

This may explain the protective role of IFNG in the model in

the present study, and its downregulation in OS cells; iii)

macrophage polarization: M1 macrophages exhibit ferroptosis

sensitivity via ACSL4, whilst M2 macrophages resist it via

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (35). The elevated M1/M2 infiltration in

the low-risk group in the present study may reflect

ferroptosis-driven plasticity, supported by enriched HIF-1/TLR

pathways in KEGG; iv) immunogenic cell death: Ferroptotic cells

release DAMPs (such as HMGB1) that activate dendritic cells and

T-cell priming (36,37). This may have driven the compensatory

immune checkpoint upregulation (PD-L1/CTLA4/LAG3) in the low-risk

group; and v) TLR4/IFNG bridge ferroptosis and immunity: TLR4

inhibits ferroptosis via ROS/p38-MAPK suppression, potentially

explaining its high-risk association. Conversely, IFNG

enhances tumor ferroptosis but risks T-cell depletion (38), creating a feedback loop evident in

the cellular data in the present study.

IFNG was excessively expressed in the low-risk

group. Moreover, the circulating concentrations of IFNG have been

reported to be markedly associated with overall survival in

patients with OS (39).

Furthermore, IFNG serves a crucial role in the antitumor immune

response by enhancing antigen presentation, T-lymphocyte

differentiation and maturation across several cancers (40). For example, IFN-γ, encoded by the

IFNG gene, acts on tumor cells, enhancing their recognition by

CD8+ T cells as well as by CD4+ T cells.

IFN-γ can promote tumor cell apoptosis by upregulating the

expression of caspase-1, −3 and −8. An important aspect is the

ability of IFN-γ to induce PD-L1 expression in cancer, stromal and

myeloid cells, which impairs effector tumor immunity (41,42).

The aforementioned research indicates that IFNG is involved in

tumor immunity, which aligns with the findings of the present

study.

TLR4 is known for its function in recognizing

pathogen-associated antigens and activating the production of

pro-inflammatory factors (43). It

has previously been reported to serve a role in lung tumorigenesis

induced by chemically induced pulmonary inflammation (44). Furthermore, the inhibition of TLR4

has been reported to mitigate oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced

ferroptosis by suppressing oxidative stress and p38-MAPK signaling,

ultimately enhancing neuronal cell viability (38). Moreover, the present study

investigated the association between IFNG/TLR4 expression and drug

sensitivity using publicly available pharmacogenomic databases

(GDSC or CTRP). Spearman correlation analysis revealed that higher

IFNG expression was significantly associated with increased

sensitivity to entinostat (r=0.32, P<0.05) and decitabine

(r=0.28, P<0.05), both epigenetic modulators. Conversely,

elevated TLR4 expression correlated with resistance to cisplatin

(r=−0.35, P<0.05), a conventional chemotherapeutic agent

commonly used in OS treatment. These findings suggest that our

ferroptosis-based risk signature may not only have prognostic value

but also potential implications for predicting treatment

response.

Considering the pivotal role of TIICs in the

progression of cancers, the diverse types of TIICs were explored

between low- and high-risk cohorts in the present study. A previous

investigation reported that resting memory CD4+ T cells

are among the most enriched TIICs in gastric cancer samples

(45). In addition, studies have

reported the presence of follicular helper T cells in tertiary

lymphoid structures of numerous tumors, suggesting that they serve

a role in generating effective and sustained antitumor immune

responses (46). Macrophages are

considered to serve as both antitumor agents (M1 macrophages) and

protumor agents (M2 macrophages) (47). In the present study, patients in the

high-risk group exhibited an elevated level of M0 macrophages. By

contrast, patients in the low-risk group showed increased

proportions of both M0 and M2 macrophages. Immune checkpoint

molecules, including CD274, CTLA4 and LAG3, have been demonstrated

to serve a role in tumor immunology (48). The targeted blockade of two

molecules, CD274 and CTLA-4, resulted in clinical benefits for

individuals with several solid tumors (49,50).

The present study revealed that the expression of immune checkpoint

genes in the low-risk group was higher than in the high-risk group.

Furthermore, GSEA based on RNA-Seq data revealed that the risk

score was associated with the antigen processing and presentation

pathway, the toll-like receptor signaling pathway and the

cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. In the tumor

microenvironment, numerous chemokines are released to facilitate

the migration of immune cells, thereby mediating the balance

between protumor and antitumor responses (51). The toll-like receptor pathway was

originally recognized as a critical mediator regulating immune

responses (52). Therefore, the

toll-like receptor signaling pathway could potentially be used to

predict responses to immunotherapy. In summary, the results of the

present study indicate that a high risk of mortality (poor overall

survival), as predicted by ferroptosis-based prognostic signature,

may influence immune infiltration-related biological processes.

Several limitations of the present study warrant

consideration. Firstly, the analysis was retrospective and relied

on publicly available datasets (TARGET and GEO). Whilst the

prognostic model was validated in an independent cohort (GEO), the

inherent biases and unmeasured confounders associated with

retrospective data cannot be fully eliminated. Prospective

validation in larger, uniformly treated cohorts is essential.

Secondly, data heterogeneity between the TARGET (RNA-seq) and GEO

(microarray) datasets, including differences in platform

technology, normalization methods and sample processing, poses

challenges for direct integration and validation. Mitigation of

this was attempted using standardized methods (such as ssGSEA,

CIBERSORT and consistent bioinformatic pipelines) and focusing on

relative risk stratification rather than absolute expression

cut-offs. However, this heterogeneity likely contributed to the

reduced statistical significance of the risk score as an

independent prognostic factor in the smaller GEO cohort during MCR

(Fig. 8D). Thirdly, the statistical

models have inherent limitations. The LASSO Cox regression used for

model construction helps prevent overfitting but may not capture

all relevant biological complexity. The sample size, particularly

for subgroup analyses and the GEO validation cohort, limits

statistical power. Furthermore, whilst standard significance

thresholds (P<0.05) were used for certain comparative analyses

(such as immune cell infiltration and checkpoint expression),

formal adjustment for multiple testing was not applied in all

exploratory comparisons, potentially increasing the risk of Type I

errors. Fourthly, whilst the cellular experiments demonstrated

differential expression of IFNG and TLR4 in OS cell lines compared

with in normal osteoblasts (Fig.

12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14), these in vitro models

cannot fully recapitulate the complexity of the in vivo

tumor microenvironment and its immune interactions. Therefore,

functional studies are needed to definitively establish the causal

roles of these genes in modulating ferroptosis and immune

infiltration within OS. Finally, the precise mechanistic links

between ferroptosis (as defined by the specific genes IFNG and

TLR4) and the observed immune cell profiles remain correlative

based on the bioinformatic and cellular expression data. Dedicated

experiments investigating how modulation of IFNG or TLR4 affects

ferroptosis sensitivity and immune cell behavior in OS models are

crucial next steps.

In conclusion, in the present study, two immune

subtypes in OS (Immunity_H and Immunity_L) with differing immune

infiltration and patient outcomes were identified. A prognostic

model based on ferroptosis genes (IFNG and TLR4) stratified

patients into high- and low-risk groups, where high-risk was

characterized by increased M0 macrophages and reduced immune

checkpoint expression. The findings highlight the interplay between

ferroptosis and immune regulation in OS. Future studies should

validate these genes as therapeutic targets and explore their

mechanisms in larger cohorts and preclinical models.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was received from the Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of

Pediatric Orthopedics (grant no. 2023TP1019), Science and

Technology Project of Furong Laboratory (grant no. 2023SK2111),

Hunan Provincial Clinical Medical Research Center for Pediatric

Limb Deformities (grant no. 2019SK4006) and Hunan Provincial Health

Research Project (grant no. 20256815).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LRZ and GY conceived and designed the study. LRZ

collected data and wrote the manuscript. GHZ and HBM analyzed data

and constructed the figures. GY revised the manuscript, LRZ and GY

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

OS

|

osteosarcoma

|

|

DEG

|

differentially expressed gene

|

|

UCR

|

univariate Cox regression

|

|

MCR

|

multivariate Cox regression

|

|

ssGSEA

|

single-sample Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis

|

|

TARGET

|

Therapeutically Applicable Research to

Generate Effective Treatments

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

TIIC

|

tumor-infiltrating immune cell

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Isakoff MS, Bielack SS, Meltzer P and

Gorlick R: Osteosarcoma: Current treatment and a collaborative

pathway to success. J Clin Oncol. 33:3029–3035. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mirabello L, Troisi RJ and Savage SA:

International osteosarcoma incidence patterns in children and

adolescents, middle ages and elderly persons. Int J Cancer.

125:229–234. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pei Y, Yao Q, Li Y, Zhang X and Xie B:

microRNA-211 regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and

migration/invasion in human osteosarcoma via targeting EZRIN. Cell

Mol Biol Lett. 24:482019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shen JK, Cote GM, Choy E, Yang P, Harmon

D, Schwab J, Nielsen GP, Chebib I, Ferrone S, Wang X, et al:

Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in osteosarcoma. Cancer

Immunol Res. 2:690–698. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tawbi HA, Burgess M, Bolejack V, Van Tine

BA, Schuetze SM, Hu J, D'Angelo S, Attia S, Riedel RF, Priebat DA,

et al: Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone

sarcoma (SARC028): A multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm,

open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:1493–1501. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pardoll DM: The blockade of immune

checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:252–264.

2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, Hwu WJ,

Weber JS, Ribas A, Hodi FS, Joshua AM, Kefford R, Hersey P, et al:

Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and response to the

anti-programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab in melanoma. J Clin

Oncol. 34:4102–4109. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao

N, Sun B and Wang G: Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell

Death Dis. 11:882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

He GN, Bao NR, Wang S, Xi M, Zhang TH and

Chen FS: Ketamine induces ferroptosis of liver cancer cells by

targeting lncRNA PVT1/miR-214-3p/GPX4. Drug Des Devel Ther.

15:3965–3978. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy

PD, Johnson JK, Liao P, Lang X, Kryczek I, Sell A, et al:

CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer

immunotherapy. Nature. 569:270–274. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen X, Bahrami A, Pappo A, Easton J,

Dalton J, Hedlund E, Ellison D, Shurtleff S, Wu G, Wei L, et al:

Recurrent somatic structural variations contribute to tumorigenesis

in pediatric osteosarcoma. Cell Rep. 7:104–112. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen W, Liao Y, Sun P, Tu J, Zou Y, Fang

J, Chen Z, Li H, Chen J, Peng Y, et al: Construction of an ER

stress-related prognostic signature for predicting prognosis and

screening the effective anti-tumor drug in osteosarcoma. J Transl

Med. 22:662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pradervand S, Weber J, Thomas J, Bueno M,

Wirapati P, Lefort K, Dotto GP and Harshman K: Impact of

normalization on miRNA microarray expression profiling. RNA.

15:493–501. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nguyen CB, Kumar S, Zucknick M, Kristensen

VN, Gjerstad J, Nilsen H and Wyller VB: Associations between

clinical symptoms, plasma norepinephrine and deregulated immune

gene networks in subgroups of adolescent with chronic fatigue

syndrome. Brain Behav Immun. 76:82–96. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang T, Wang S, Hua D, Shi X, Deng H, Jin

S and Lv X: Identification of ZIP8-induced ferroptosis as a major

type of cell death in monocytes under sepsis conditions. Redox

Biol. 69:1029852024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yu D, Hu H, Zhang Q, Wang C, Xu M, Xu H,

Geng X, Cai M, Zhang H, Guo M, et al: Acevaltrate as a novel

ferroptosis inducer with dual targets of PCBP1/2 and GPX4 in

colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:2112025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zou Y, Palte MJ, Deik AA, Li H, Eaton JK,

Wang W, Tseng YY, Deasy R, Kost-Alimova M, Dančík V, et al: A

GPX4-dependent cancer cell state underlies the clear-cell

morphology and confers sensitivity to ferroptosis. Nat Commun.

10:16172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV,

Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, et al: The

prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across

human cancers. Nat Med. 21:938–945. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bashur L and Zhou G: Cancer stem cells in

osteosarcoma. Case Orthop J. 10:38–42. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang SD, Li HY, Li BH, Xie T, Zhu T, Sun

LL, Ren HY and Ye ZM: The role of CTLA-4 and PD-1 in anti-tumor

immune response and their potential efficacy against osteosarcoma.

Int Immunopharmacol. 38:81–89. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Tsukahara T, Emori M, Murata K, Mizushima

E, Shibayama Y, Kubo T, Kanaseki T, Hirohashi Y, Yamashita T, Sato

N and Torigoe T: The future of immunotherapy for sarcoma. Expert

Opin Biol Ther. 16:1049–1057. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Scott MC, Temiz NA, Sarver AE, LaRue RS,

Rathe SK, Varshney J, Wolf NK, Moriarity BS, O'Brien TD, Spector

LG, et al: Comparative transcriptome analysis quantifies immune

cell transcript levels, metastatic progression, and survival in

osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 78:326–337. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Merchant MS, Melchionda F, Sinha M, Khanna

C, Helman L and Mackall CL: Immune reconstitution prevents

metastatic recurrence of murine osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 56:1037–1046. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Morgan PK, Pernes G, Huynh K, Giles C,

Paul S, Smith AAT, Mellett NA, Liang A, van Buuren-Milne T, Veiga

CB, et al: A lipid atlas of human and mouse immune cells provides

insights into ferroptosis susceptibility. Nat Cell Biol.

26:645–659. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ma L, Chen C, Zhao C, Li T, Ma L, Jiang J,

Duan Z, Si Q, Chuang TH, Xiang R and Luo Y: Targeting carnitine

palmitoyl transferase 1A (CPT1A) induces ferroptosis and synergizes

with immunotherapy in lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9:642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bell HN, Stockwell BR and Zou W: Ironing

out the role of ferroptosis in immunity. Immunity. 57:941–956.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zheng Y, Sun L, Guo J and Ma J: The

crosstalk between ferroptosis and anti-tumor immunity in the tumor

microenvironment: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic controversy.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:1071–1096. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li X, Li Y, Tuerxun H and Zhao Y, Liu X

and Zhao Y: Firing up ‘cold’ tumors: Ferroptosis causes immune

activation by improving T cell infiltration. Biomed Pharmacother.

179:1172982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cheng Z, Wang K, Wang Y, Liu T, Li J, Wang

Y, Chen W, Awuti R, Zhou H, Tong W, et al: Ferroptosis mediated by

the IDO1/Kyn/AhR pathway triggers acute thymic involution in

sepsis. Cell Death Dis. 16:5622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhou J, Yin H, Pan J, Yin R, Wei X, Shen

M, Cai L, Liu Z, Zhao J, Chen W, et al: Lnk deficiency attenuates

the immunosuppressive capacity of MDSCs via ferroptosis to suppress

tumor development. Cell Death Dis. 16:6102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li S, Ouyang X, Sun H, Jin J, Chen Y, Li

L, Wang Q, He Y, Wang J, Chen T, et al: DEPDC5 protects

CD8+ T cells from ferroptosis by limiting

mTORC1-mediated purine catabolism. Cell Discov. 10:532024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hu J, Cui L, Hou B, Ding X, Liu H, Sun W,

Mi Y, Chen Y and Zou Z: Ferroptosis in tumor associated immune

cells: A double-edged sword against tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

212:1048182025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gupta T, Wu SR, Chang LC, Lin FC, Shan YS,

Yeh CS and Su WP: Radiocleavable rare-earth nanoactivators

targeting over-expressed folate receptors induce mitochondrial

dysfunction and remodel immune suppressive microenvironment in

pancreatic cancer. J Nanobiotechnology. 23:5622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li P, Huang C, He Y, Lei X, Shen X, Xu J,

Mo Y, Sun X, Zheng L and Niu Y: M2 macrophage-laden vascular grafts

orchestrate the optimization of the inflammatory microenvironment

for abdominal aorta regeneration. Acta Biomater. 204:323–339. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhu K, Zhu X, Sun S, Yang W, Liu S, Tang

Z, Zhang R, Li J, Shen T and Hei M: Inhibition of TLR4 prevents

hippocampal hypoxic-ischemic injury by regulating ferroptosis in

neonatal rats. Exp Neurol. 345:1138282021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Flores RJ, Kelly AJ, Li Y, Nakka M,

Barkauskas DA, Krailo M, Wang LL, Perlaky L, Lau CC, Hicks MJ and

Man TK: A novel prognostic model for osteosarcoma using circulating

CXCL10 and FLT3LG. Cancer. 123:144–154. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Castro F, Cardoso AP, Gonçalves RM, Serre

K and Oliveira MJ: Interferon-gamma at the crossroads of tumor

immune surveillance or evasion. Front Immunol. 9:8472018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Shtrichman R and Samuel CE: The role of

gamma interferon in antimicrobial immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol.

4:251–259. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, Saco J,

Escuin-Ordinas H, Rodriguez GA, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Hugo W, Wang X,

et al: Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and

PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep. 19:1189–1201. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Rosadini CV, Zanoni I, Odendall C, Green

ER, Paczosa MK, Philip NH, Brodsky IE, Mecsas J and Kagan JC: A

single bacterial immune evasion strategy dismantles both MyD88 and

TRIF signaling pathways downstream of TLR4. Cell Host Microbe.

18:682–693. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bauer AK, Dixon D, DeGraff LM, Cho HY,

Walker CR, Malkinson AM and Kleeberger SR: Toll-like receptor 4 in

butylated hydroxytoluene-induced mouse pulmonary inflammation and

tumorigenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 97:1778–1781. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Li L, Ouyang Y, Wang W, Hou D and Zhu Y:

The landscape and prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells in gastric cancer. PeerJ. 7:e79932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gu-Trantien C, Loi S, Garaud S, Equeter C,

Libin M, de Wind A, Ravoet M, Le Buanec H, Sibille C,

Manfouo-Foutsop G, et al: CD4+ follicular helper T cell

infiltration predicts breast cancer survival. J Clin Invest.

123:2873–2892. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Gambardella V, Castillo J, Tarazona N,

Gimeno-Valiente F, Martínez-Ciarpaglini C, Cabeza-Segura M, Roselló

S, Roda D, Huerta M, Cervantes A and Fleitas T: The role of

tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer development and

their potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer Treat Rev.

86:1020152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Harrington BK, Wheeler E, Hornbuckle K,

Shana'ah AY, Youssef Y, Smith L, Hassan Q II, Klamer B, Zhang X,

Long M, et al: Modulation of immune checkpoint molecule expression

in mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 60:2498–2507. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow

MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K,

et al: Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J

Med. 369:122–133. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Redman

BG, Kuzel TM, Harrison MR, Vaishampayan UN, Drabkin HA, George S,

Logan TF, et al: Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma:

Results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 33:1430–1437.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Goralski KB, Jackson AE, McKeown BT and

Sinal CJ: More than an adipokine: The complex roles of chemerin

signaling in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 20:47782019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Tran TH, Tran TTP, Truong DH, Nguyen HT,

Pham TT, Yong CS and Kim JO: Toll-like receptor-targeted particles:

A paradigm to manipulate the tumor microenvironment for cancer

immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 94:82–96. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|