Introduction

Castleman disease is a relatively rare non-clonal

lymphoproliferative disease characterized by the histopathological

findings of the lymph nodes, as reported by Castleman et al

(1). Clinically, it is classified

into unicentric Castleman disease (UCD), in which the affected

lymph nodes are confined to a single region, and multicentric

Castleman disease (MCD), characterized by generalized

lymphadenopathy (2–5). The clinical symptoms of CD include a

variety of systemic symptoms and abnormalities upon testing. CD is

characterized by histological findings such as lymphoid follicle

hyperplasia and vascular invasion into lymphoid follicles, and is

definitively diagnosed based on histopathological findings. The

most common site of Castleman disease is the mediastinum,

accounting for approximately 70% of all cases; however, 15% of such

cases occur in the head and neck (6). Therefore, it is necessary to keep in

mind the concept of Castleman disease when cervical lymphadenopathy

is observed. However, it is extremely rare for Castleman disease to

occur in association with head and neck cancer cases, including

oral cancer, in which case it becomes difficult to distinguish

between the metastatic lymph nodes from head and neck cancer and

Castleman disease. Furthermore, the treatment for the two diseases

is completely different, so proper diagnosis is essential.

We experienced a case of MCD that was incidentally

detected during an evaluation of tongue cancer, and report this

case with a review of the pertinent literature.

Case report

A 73-year-old male was referred to our department by

our Internal Medicine Department in May 2022 under a suspicion of

tongue cancer on the left side. The patient became aware of pain in

the same region one month prior to his initial visit. His medical

history included chronic kidney disease, hypothyroidism, chronic

stasis dermatitis, and anemia. At his initial visit, a 25×15 mm

exophytic tumor with a slightly ambiguous border was observed on

the left side of his tongue; however, no paresthesia of the lingual

nerve was observed (Fig. 1). In

addition, no obvious swelling or tenderness of the cervical lymph

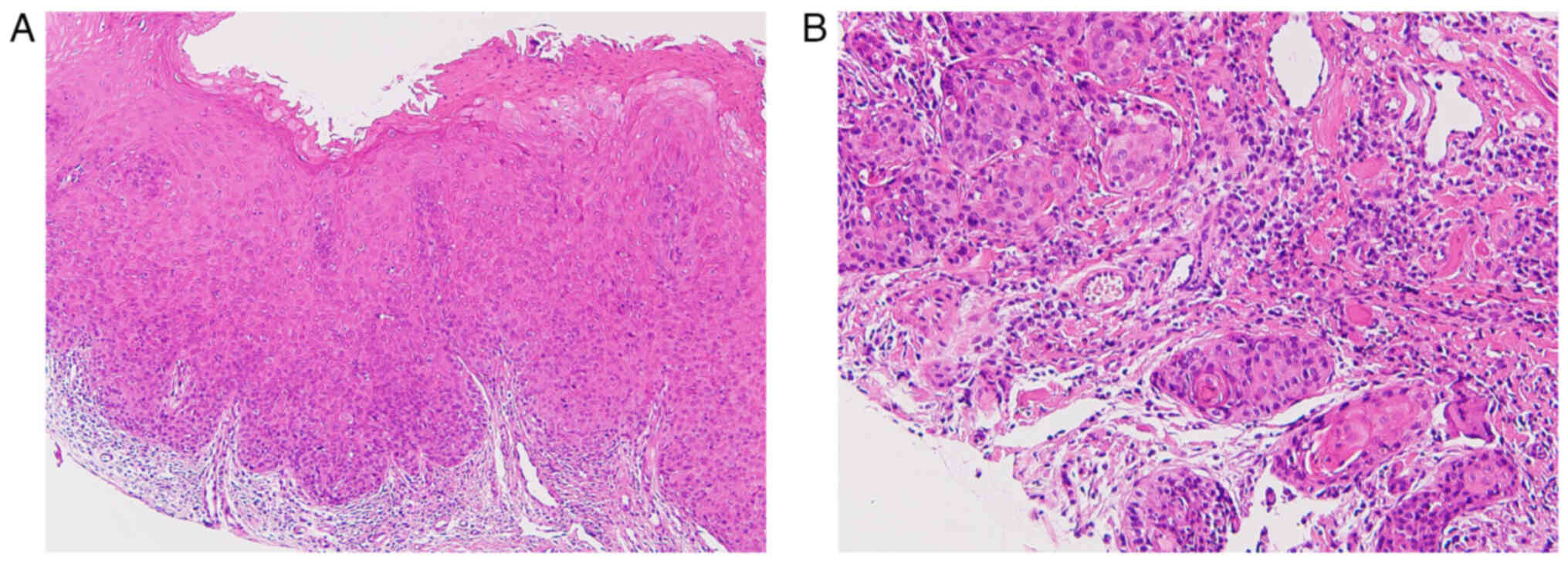

nodes was palpable. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated squamous

cell carcinoma (Fig. 2). A

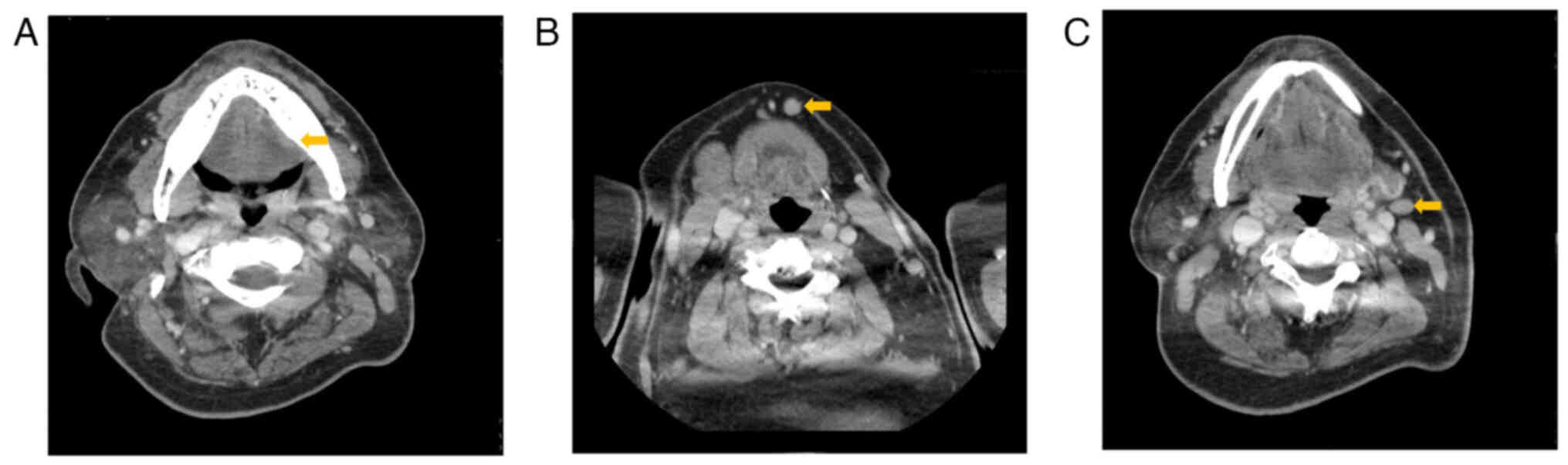

neoplastic lesion measuring 25×15×4 mm in size was observed on the

left side of his tongue upon Computed tomography (CT) and Magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI), with mild enlargement observed in the

submental lymph nodes and left submandibular lymph nodes; however,

no lung lesions were observed (Fig.

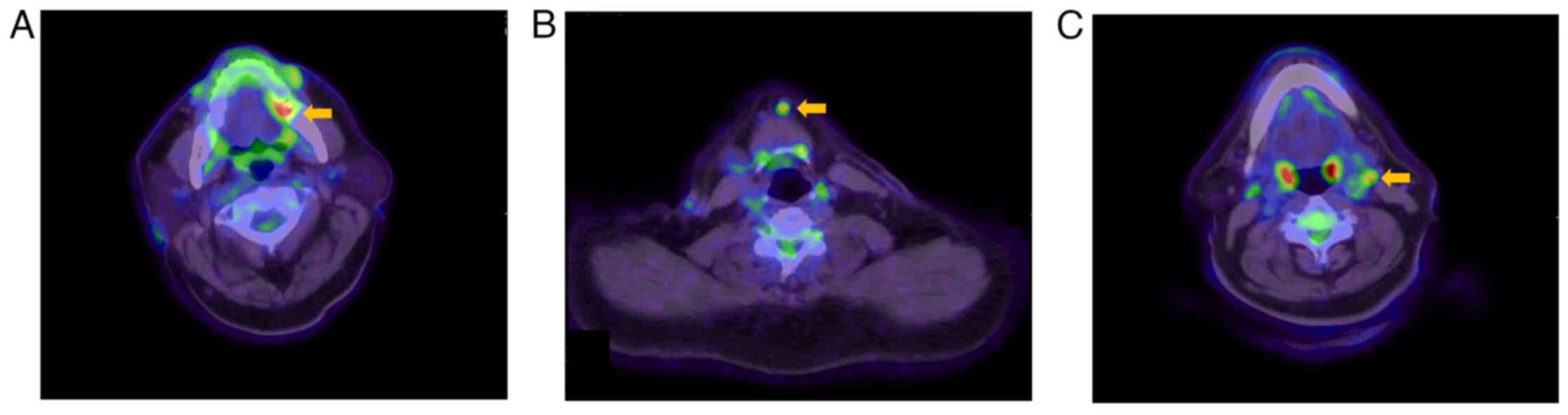

3). F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed

tomography (FDG-PET/CT) revealed a strong accumulation of SUVmax

6.9 on the left side of his tongue. An abnormal FDG uptake was also

observed in the submental lymph node (SUVmax 5.2) and the left

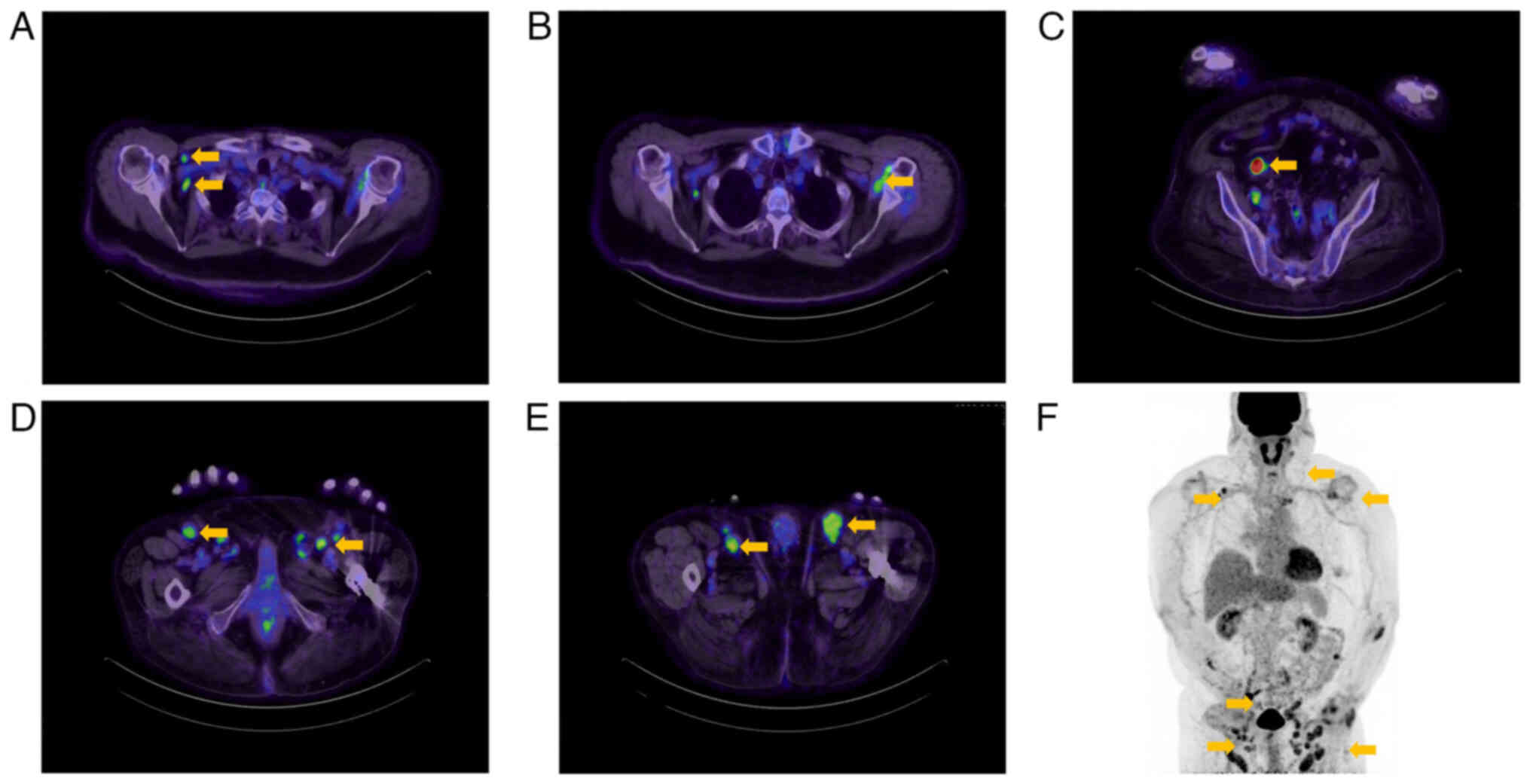

submandibular lymph node (SUVmax 4.8) (Fig. 4). In addition, multiple intense

accumulations (SUVmax 1.7–6.5) were detected in the lymph nodes of

both axillae, around the abdominal aorta, in the pelvic cavity, and

in both inguinal regions (Fig. 5).

Blood test results indicated low values of hemoglobin content (Hb)

at 10.4 g/dl and albumin (Alb) at 3 1g/dl, a slightly elevated

C-reactive protein (CRP) at 1.79 mg/dl, and a high γ-globulin

fraction in the protein fractionation pattern at 38.4%. Although

lymphoproliferative disorder was suspected, metastasis from tongue

cancer to the cervical lymph nodes could not be ruled out. For this

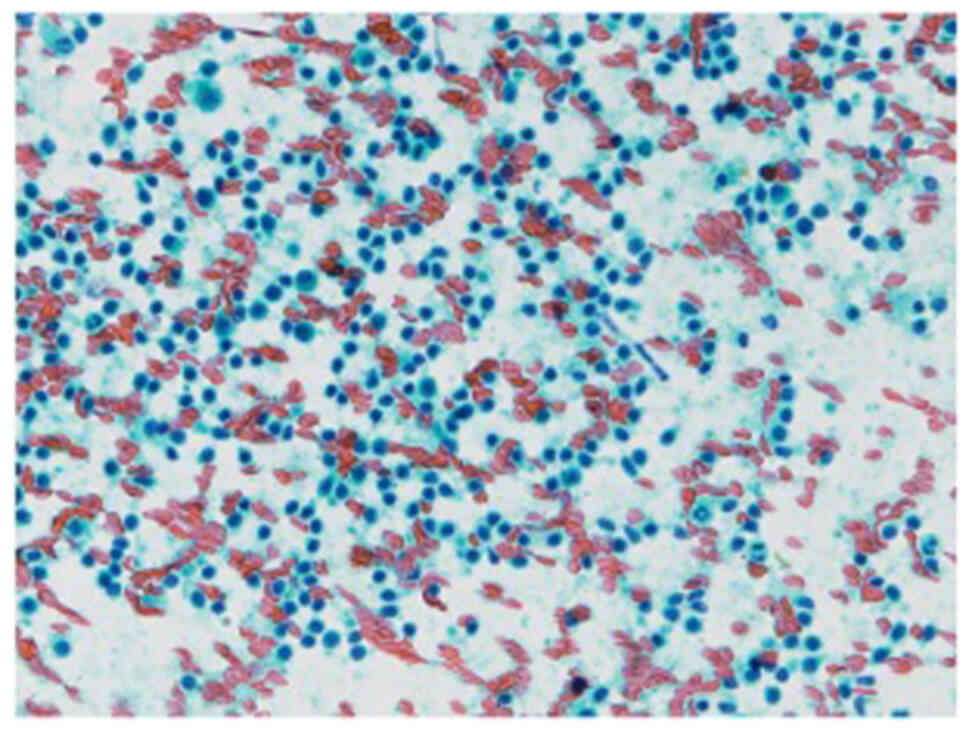

reason, we performed fine needle aspiration (FNA) on the submental

lymph nodes and left submandibular lymph nodes, while observing no

atypical epithelial cells suggesting metastasis (Fig. 6). In addition, we consulted our

Dermatology Department and performed a lymph node biopsy from the

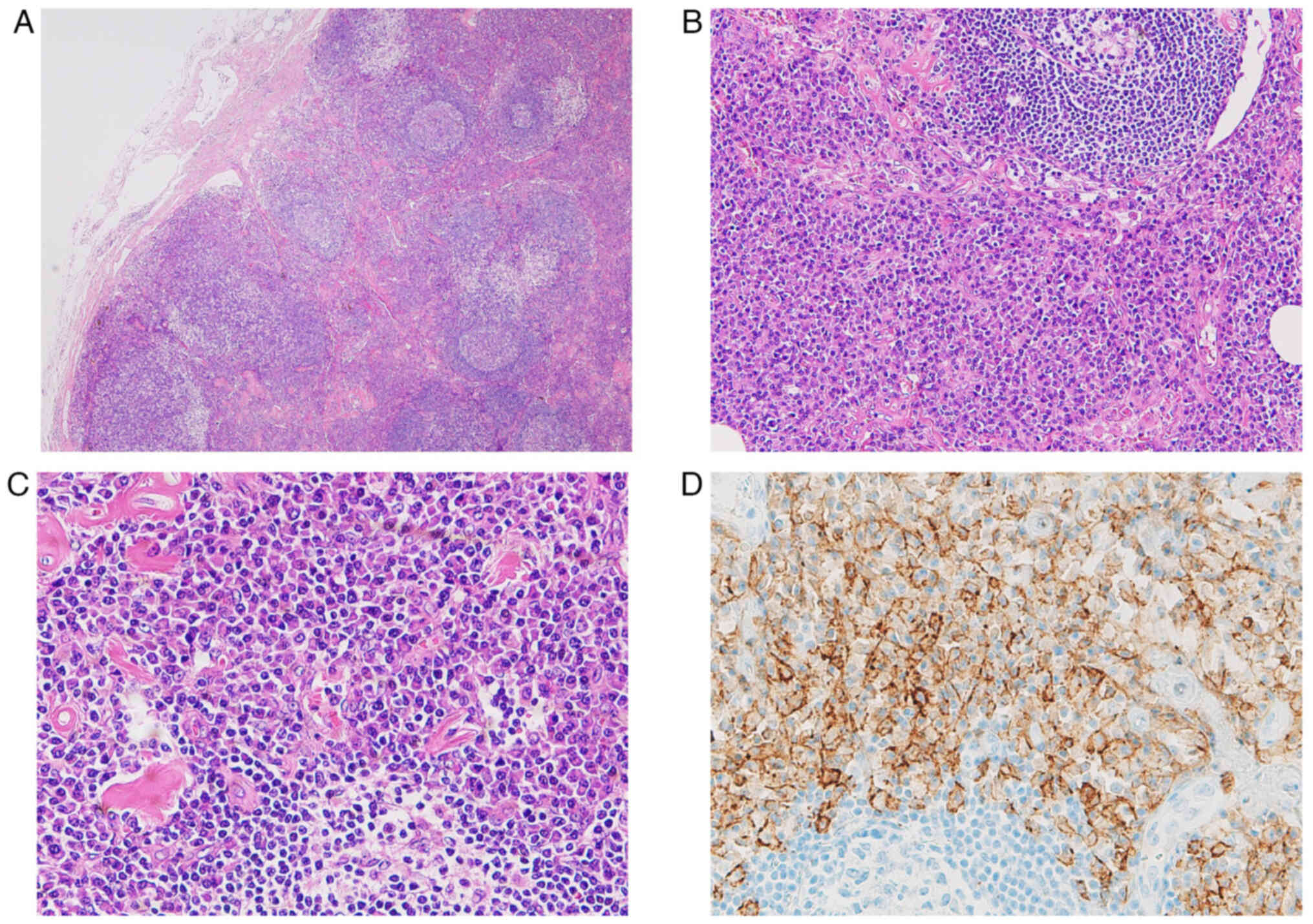

left inguinal region. Histologically, we observed follicle

formation with an embryonic center and significant plasma cell

proliferation around the follicle. When we investigated

kappa/lambda chains by means of clonality studies, the plasma cells

were not biased by kappa/lambda chains and immunohistochemistry did

not reveal any findings that could be considered to be tumor

proliferation. Since there was also no amyloid deposition, the

patient was diagnosed with a plasma cell variant of Castleman

disease (Fig. 7).

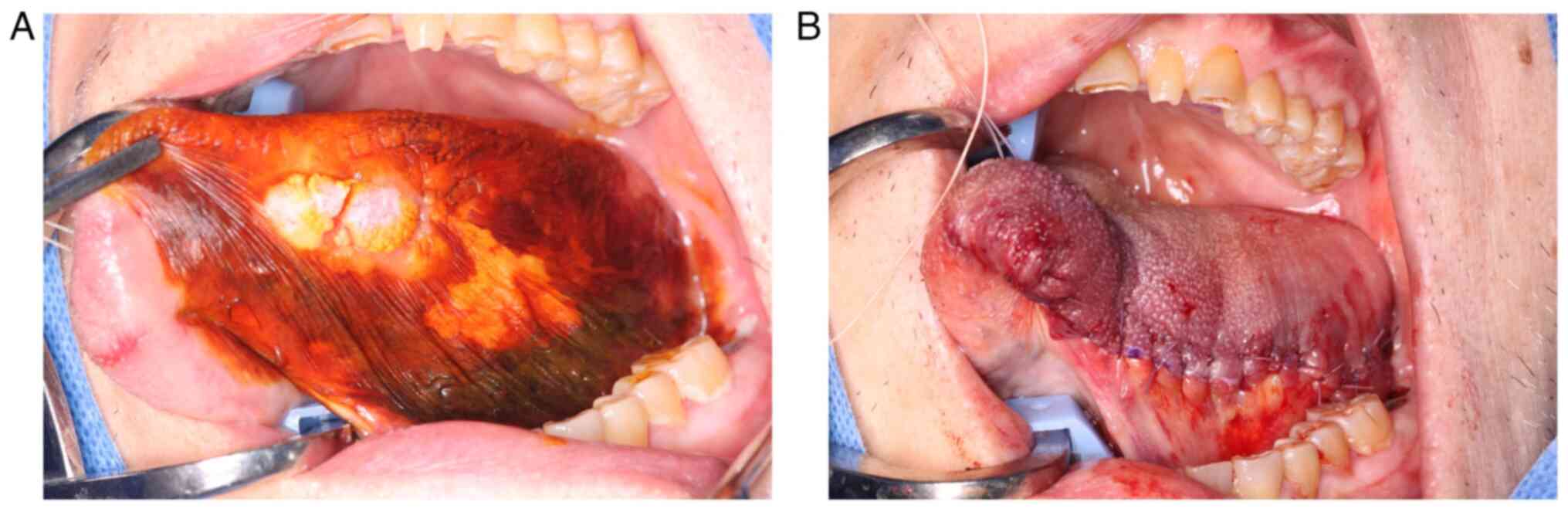

Based on the above, in August 2022, a left partial

glossectomy was performed under general anesthesia with a diagnosis

of left lingual squamous cell carcinoma (cT2N0M0, stage II) along

with MCD. Following the resection, the wound was sutured with 4-0

absorbent sutures (Fig. 8).

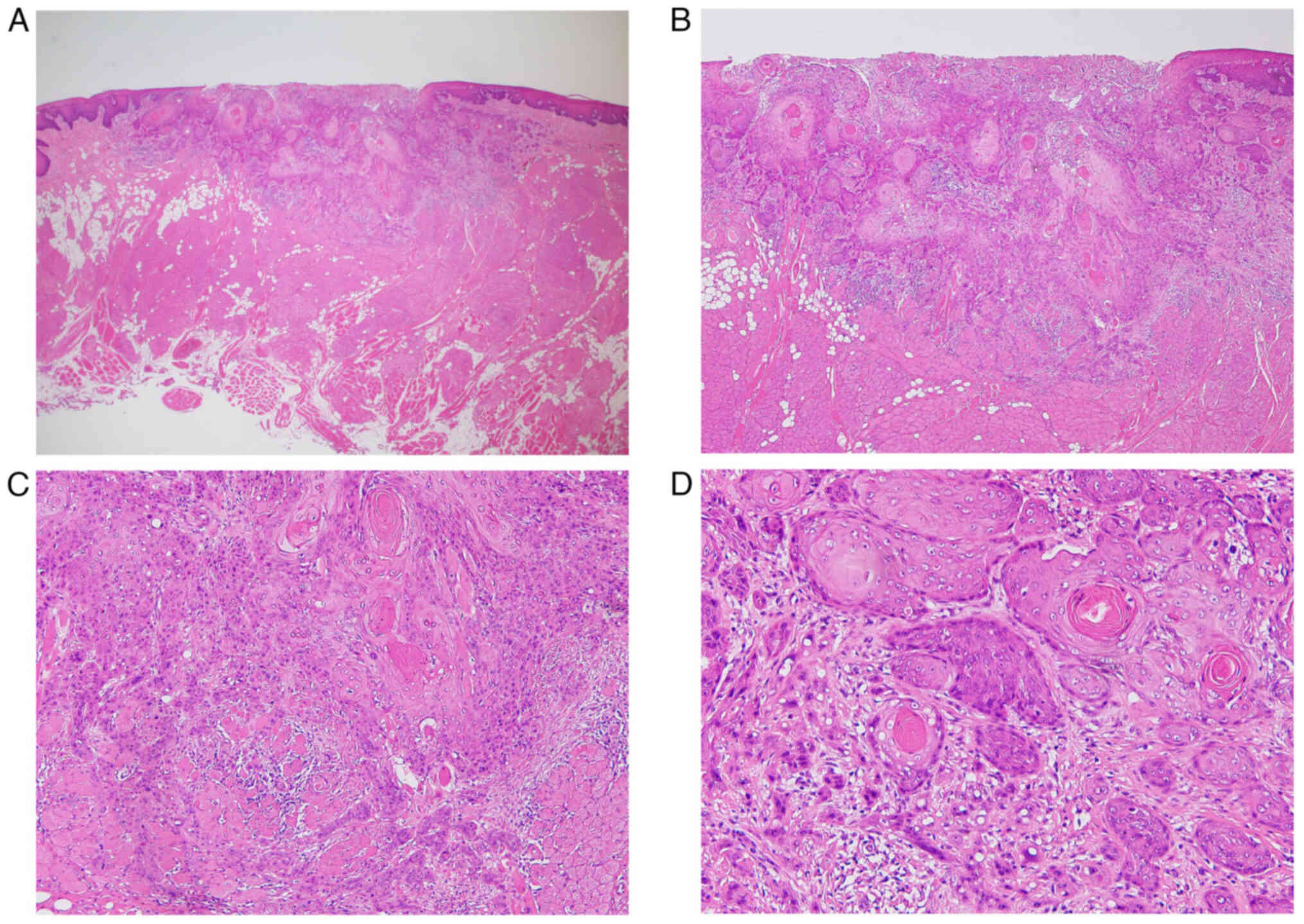

Histopathologically, the lesion showed a sheet-like proliferation

of atypical squamous cells with a tendency to keratinize, thus

forming large and small nests and infiltrating into the superficial

muscle layer. Moreover, low-grade dysplasia was observed in the

white mucosa around the tumor (Fig.

9). The depth of invasion was 2 mm and venous infiltration was

observed; however, no lymphatic vessels or nerve infiltration was

observed. Based on the above, the lesion was diagnosed as squamous

cell carcinoma (SCC) of the tongue (pT2N0M0, grade 1, stage II).

Our hematology department thereafter was responsible for the

treatment for Castleman disease. Because the symptoms were mild and

asymptomatic, with the 10-year survival rate expected to be 80%

even without treatment, our course of action was to monitor his

progress without using any immunosuppressive drugs and tocilizumab.

It was decided that if symptoms such as fatigue and slight fever

appeared, then the administration of 0.3 mg/kg/day of prednisolone

will be initiated, and if these symptoms were to either worsen or

if organ symptoms are observed, then the administration of

tocilizumab would be considered while increasing the dose of

prednisolone to 1 mg/kg/day. Postoperatively, the patient has been

undergoing monthly follow-up visits and CT scans every three months

to monitor the status of his tongue and the lymph node lesions.

Currently, there has been no evidence of any recurrent metastasis

of the tongue cancer even 30 months following surgery, and with no

progression of Castleman disease observed.

Discussion

Castleman disease is a non-neoplastic

lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown origin and it is a

relatively rare disease that was reported by Castleman et al

(1) in 1956. Subsequently, it was

histopathologically classified into three types by Keller et

al (7): hyaline vascular type

(HV type); plasma cell type (PC type); and mixed type (M type). HV

type is histologically characterized by the proliferation of

lymphoid follicles and the proliferation and vitrification of blood

vessels between follicles. It has few clinical symptoms and it

rarely demonstrates abnormal values upon blood testing. On the

other hand, PC type is characterized by the diffuse, sheet-like

infiltration of plasma cells into the interfollicular tissue and

expansion of the follicular spaces, which often causes a variety of

clinical symptoms such as generalized lymphadenopathy, anemia, and

abnormal blood tests. Although there are no specific

immunohistochemical markers for diagnosis, plasma cells may

occasionally be identified using CD138 immunostaining. Moreover,

depending on the distribution of the lesions, it is also

distinguished from UCD, which occurs only in a single lymph node,

and MCD, which spreads to multiple regions. In principle, UCD

corresponds to HV type, and MCD corresponds to PC type and M type.

However, typical findings are not always obtained in the

histopathological diagnosis of MCD, so careful judgment is required

for each individual case, while carefully considering the available

clinical information. The clinical symptoms of MCD include general

malaise, fever, anemia, high value of CRP, hypergammaglobulinemia,

and a variety of systemic symptoms and abnormalities upon testing.

A diagnosis is made based on both the clinical symptoms and the

histopathology of the enlarged lymph nodes (2). While clinical symptoms such as general

malaise and fever were not observed in our case, low Hb and Alb

values and a high gamma-globulin fraction were observed upon blood

testing. In addition, due to the fact that a CT scan confirmed the

enlargement of lymph nodes across multiple regions and that the

degree of plasma cell infiltration was histopathologically high, it

was diagnosed as a PC type of MCD.

While the most common site of Castleman disease is

the mediastinum, 15% of such cases occur in the head and neck, and

it is also known to occur in the abdominal cavity and axilla. The

differential diagnosis of Castleman disease occurring in the neck

includes inflammatory cervical lymphadenitis, cervical lymph node

metastasis of malignant tumors, and malignant lymphoma, as well as

sarcoidosis and IgG4-related diseases. If head and neck cancer is

present, then cervical lymph node metastasis should first be

suspected. In our case, multiple abnormal FDG accumulations were

systemically observed in addition to cervical lymph nodes upon

PET/CT, suggesting at least some form of lymphoproliferative

disorder. However, regarding the cervical lymph nodes, because the

possibility of metastasis from tongue cancer could not be ruled

out, FNA was performed. As far as we were able to find,

English-language reported cases of Castleman disease occurring in

conjunction with head and neck cancer are extremely rare, with only

three known cases, including our own case (8,9)

(Table I). The average patient age

was 47.7 years, with two patients in their 30s. There were two

males and one female, with the cancer site being the tongue in all

three cases. Histopathologically, two cases were HV type, and one

case was PC type. Regarding the site of lymphadenopathy, two cases

occurred at a single site (mediastinum, submandibular region) and

one case occurred at multiple sites. As noted earlier, both of the

two non-self cases of UCD corresponded to HV type. Lymphadenopathy

was also observed in the neck in two cases, including our own case.

In one case, under a diagnosis of cT1N3aM0, hemi-glossectomy and

bilateral neck dissection were performed. However, no lymph node

metastasis was observed in the postoperative histopathological

diagnosis, so it may have been possible to treat the disease by

partial resection alone. In our own case, only a partial

glossectomy was performed based on the results of the preoperative

FNA. To differentiate between metastatic lymph nodes from oral

cancer and Castleman disease, cervical ultrasonography, CT, and MRI

are first performed. However, as both conditions present with very

similar imaging findings, a definitive diagnosis requires either

FNA or a biopsy of the lymph node.

| Table I.Castleman disease occurring in

conjunction with head and neck cancer. |

Table I.

Castleman disease occurring in

conjunction with head and neck cancer.

| Author | Sex | Age | Location of SCC | Location of lymph

node enlargement | Clinical

diagnosis | Diagnosis at

biopsy | Treatment | Histopathological

diagnosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pereira et

al | F | 38 | Tongue | Right posteromedial

mediastinum | Germ cell cell

tumor | Small blue

lesion | Right posterolateral

excision of chest wall and thoracotomy with the right paraspinous

tumor | Hyaline vascular type

Castleman disease | (9) |

| Deshmukh et

al | M | 32 | Tongue | Submandibular

lesion | Cervical lymph node

metastasis | NA | Bilateral modified

neck dissection | Hyaline vascular type

Castleman disease | (8) |

| Present case | M | 73 | Tongue | Submental and left

submandibular, bilateral axillary, abdominal periaortic, pelvic,

and bilateral inguinal lymph nodes | Lymphoproliferative

disorders | Plasma cell type

Castleman disease | Observation | - | - |

MCD is believed to be caused by the sustained

production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) (10). For this reason, treatment is

centered on IL-6 inhibitors, with siltuximab mainly used (11); however, tocilizumab (2), an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, is the

only approved treatment by the Japanese National Health Insurance

System. In asymptomatic cases with only mild laboratory

abnormalities, as in the present case, careful observation may be

an appropriate management option. In moderate to severe cases, the

concomitant use of steroids is recommended in addition to

tocilizumab (12,13). With proper treatment, the prognosis

is relatively good, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 100% and

a 10-year overall survival rate of 90% or more in Japan (14). That said, obtaining a complete cure

is difficult, with most patients not achieving permanent remission

even via treatment with tocilizumab (15), so further therapeutic drug

development and clinical trials are needed going forward.

While the relationship between Castleman disease and

SCC has not been clarified, the involvement of IL-6 has been

suggested (16). IL-6 is a cytokine

involved in a variety of biological events, including immune

reactions, hematopoiesis, and acute phase reactions, with the

overproduction thereof thought to be involved in the development of

chronic inflammatory diseases and cancers. Riedel et al

(17) reported that they observed

elevated serum IL-6 levels in head and neck SCCs, particularly in

advanced cancers with lymph node metastases. In this case, the

symptoms of Castleman disease were mild and asymptomatic, and since

no active therapeutic intervention was undertaken and only

observation was performed, the IL-6 levels were therefore not

measured. Regarding the monitoring method, if Castleman disease and

oral cancer coexist, as observed in this case, then it is necessary

to confirm both lesions, with imaging examinations conducted once

every 3 to 6 months considered to be appropriate. Although the

course of MCD is generally slow, it is recommended to conduct

systemic examinations such as PET/CT once a year. In addition, in

conjunction with the Hematology Department, we should be prepared

to respond quickly when symptoms appear.

We described a case of MCD that was incidentally

detected during an evaluation of tongue cancer and reviewed the

literature on this rare entity. Distinguishing between

lymphadenopathy in Castleman disease and lymph node metastasis in

oral cancer is difficult using just the clinical findings and

images alone. In order to provide appropriate treatment, it is

necessary to carry out a histopathological examination in

cooperation with the relevant departments to make an appropriate

diagnosis and stage classification.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YY conceptualized the case report, performed the

acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the

manuscript. YY, SS, MY, MN and KS were involved in the treatment

and follow-up in this case. SA advised on patient treatment,

analyzed patient data, critically revised the manuscript and

provided valuable feedback, provided supervision, and approved the

final manuscript for publication. YY and SA confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

publication, authorizing the use of their imaging, pathological and

clinical data for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Castleman B, Iverson L and Menendez VP:

Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma.

Cancer. 9:822–830. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, Frank

D, Wu D, Srkalovic G, Simpson D, Liu AY, Menke D, Chandrakasan S,

et al: International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria

for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease.

Blood. 129:1646–1657. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bartoli E, Massarelli G, Soggia G and

Tanda F: Multicentric giant lymph node hyperplasia. A hyperimmune

syndrome with a rapidly progressive course. Am J Clin Pathol.

73:423–426. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gaba AR, Stein RS, Sweet DL and Variakojis

D: Multicentric giant lymph node hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol.

69:86–90. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Frizzera G, Banks PM, Massarelli G and

Rosai J: A systemic lymphoproliferative disorder with morphologic

features of Castleman's disease. Pathological findings in 15

patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 7:211–231. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bonekamp D, Horton KM, Hruban RH and

Fishman EK: Castleman disease: The great mimic. Radiographics.

31:1793–1807. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Keller AR, Hochholzer L and Castleman B:

Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node

hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer.

29:670–683. 1972. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Deshmukh M, Bal M, Deshpande P and

Jambhekar NA: Synchronous squamous cell carcinoma of tongue and

unicentric cervical Castleman's disease clinically mimicking a

stage IV disease: A rare association or coincidence? Head Neck

Pathol. 5:180–183. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pereira TC, Landreneau R, Nathan G and

Sturgis CD: Pathologic quiz case. Large posterior mediastinal mass

in a young woman. Pathologic diagnosis: Localized

hyaline-vascular-type Castleman disease (angiofollicular lymphoid

hyperplasia). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 125:964–967. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nishimoto N, Kanakura Y, Aozasa K, Johkoh

T, Nakamura M, Nakano S, Nakano N, Ikeda Y, Sasaki T, Nishioka K,

et al: Humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment of

multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 106:2627–2632. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

van Rhee F, Wong RS, Munshi N, Rossi JF,

Ke XY, Fosså A, Simpson D, Capra M, Liu T, Hsieh RK, et al:

Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman's disease: A randomised,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 15:966–974.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Nishimoto N, Sasai M, Shima Y, Nakagawa M,

Matsumoto T, Shirai T, Kishimoto T and Yoshizaki K: Improvement in

Castleman's disease by humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor

antibody therapy. Blood. 95:56–61. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Dispenzieri A, Armitage JO, Loe MJ, Geyer

SM, Allred J, Camoriano JK, Menke DM, Weisenburger DD, Ristow K,

Dogan A and Habermann TM: The clinical spectrum of Castleman's

disease. Am J Hematol. 87:997–1002. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Fujimoto S, Sakai T, Kawabata H, Kurose N,

Yamada S, Takai K, Aoki S, Kuroda J, Ide M, Setoguchi K, et al: Is

TAFRO syndrome a subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman

disease? Am J Hematol. 94:975–983. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Carbone A, Borok M, Damania B, Gloghini A,

Polizzotto MN, Jayanthan RK, Fajgenbaum DC and Bower M: Castleman

disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Matsumura N, Shiiki H, Saito N, Uramoto H,

Hanatani M, Nonaka H and Nakamura S: Interleukin-6-producing thymic

squamous cell carcinoma associated with Castleman's disease and

nephrotic syndrome. Intern Med. 41:871–874. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Riedel F, Zaiss I, Herzog D, Götte K, Naim

R and Hörmann K: Serum levels of interleukin-6 in patients with

primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res.

25:2761–2765. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|