Introduction

The circadian rhythm, an intrinsic biological

process with a period of ~24 h, regulates a wide array of

physiological functions such as sleep-wake cycles, metabolism,

hormone secretion and immune responses (1–3).

Disruptions in this rhythm, collectively termed circadian rhythm

disorders (CRDs), have been associated with various health issues,

including an increased risk of developing cancer. The impact of

CRDs on cancer is multifaceted, influencing not only the

proliferation and survival of cancer cells but also the tumor

immune microenvironment (TME) (4),

which serves a key role in tumor progression and response to

therapy (5–7).

F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 22 (FBXL22),

an F-box protein-coding gene, is known to participate in the

ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is central to the regulation of

protein turnover and cellular homeostasis (8,9).

Emerging evidence suggests that FBXL22 also serves a role in cancer

development and progression, although the exact mechanism remains

unclear (8,10). Previous bioinformatics analysis has

indicated that FBXL22 is associated with breast cancer and acts as

a favorable factor for relapse-free survival in prostate cancer

(PCa) (11–13). However, a comprehensive pan-cancer

analysis of FBXL22, particularly in the context of the TME and its

interactions with the circadian rhythm, is lacking.

Due to the importance of circadian rhythms in

oncology and the potential role of FBXL22 in cancer, the present

study aimed to perform an extensive analysis of FBXL22 across

various cancer types. By leveraging data from The Cancer Genome

Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases, the

present study explored gene expression, genetic alterations and DNA

methylation patterns of FBXL22. The present analysis aimed to

reveal the correlation of these patterns with patient prognosis,

immune cell infiltration and TME, thereby providing insights into

the potential of FBXL22 as a biomarker and therapeutic target in

cancer.

Materials and methods

Data collection, normalization and

batch effect correction

Pan-cancer and normal tissue expression data for

FBXL22 were extracted from GTEx (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets) and TCGA

datasets (TCGA-PANCAN, http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) of University of

California Santa Cruz XENA (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). University of

Alabama at Birmingham CANcer data analysis Portal (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) and cBioPortal

(https://www.cbioportal.org/). RNA

sequencing expression data from TCGA and GTEx were harmonized to

ensure cross-dataset comparability. Raw read counts from TCGA were

normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) using the ‘edgeR’ R

package (R Development Core Team, version 3.46.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html).

GTEx data were processed using the same pipeline to maintain

consistency. Batch effects arising from differences in sequencing

platforms and study cohorts were corrected using the ComBat

algorithm (implemented via the ‘sva’ R package; version, 3.52.0;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/sva.html),

with ‘study cohort’ (TCGA vs. GTEx) as the batch variable.

Low-quality samples (read depth <10 million) and genes with zero

expression in >90% of the samples were excluded prior to

analysis.

Diagnostic receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve and immune infiltration analysis

The predictive accuracy of FBXL22 gene expression in

TCGA cancer types was assessed using ROC analysis with the ‘pROC’

package (Version, 1.18.0; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pROC/) in R

software (R Development Core Team; Version, 4.4.2). To assess

immune cell infiltration using the ‘ssGSEA’ algorithm, predefined

gene sets were employed from the Molecular Signatures Database

(MSigDB; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp)

hallmark collection, specifically the hallmark gene sets related to

the immune response. The cell-type marker genes used for immune

infiltration analysis were obtained from the ImmPort database

(version, DR35; http://www.immport.org/) and published literature,

ensuring their relevance and specificity for the immune cell types

under investigation. The ssGSEA algorithm was run with 1,000

permutations to assess statistical significance and normalized

enrichment scores were used to quantify the relative abundance of

immune cells in each sample. For the Tumor Immune Estimation

Resource 2.0 (TIMER2) tool (version 2.0; http://timer.cistrome.org), the present study used the

default settings with the immune gene module, which includes a

comprehensive set of immune-related genes and their corresponding

cell type-specific markers. Correlation analysis between FBXL22

expression and immune cell infiltration was performed using

Spearman's correlation coefficient to account for nonlinear

relationships.

Functional enrichment analysis of

FBXL22-related genes

Top 100 target genes associated with FBXL22

expression were identified using the ‘Similar Gene Detection’

module of Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2

(http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/). Heatmap

data for the top 10 genes were generated using the ‘Gene_Corr’

module of TIMER2. Protein-protein interaction networks were

constructed using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting

Genes/Proteins database (STRING: functional protein association

networks; http://cn.string-db.org/). Functional

enrichment analysis was performed using the ‘clusterProfiler’

package in the R software (version 4.10.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler/).

Gene ontology (GO, http://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg) enrichment analyses

(14) were performed to explore the

biological processes and pathways associated with FBXL22.

Significant terms were defined as those with an adjusted P-value

<0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction) and a minimum gene count

of 5 per term.

Subgroup survival prognosis analysis

for PCa and expression analysis in disease subtypes

RNA sequencing data from TCGA-prostate

adenocarcinoma (TCGA-PRAD; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-PRAD)

project were downloaded and organized using TCGA database

(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). Clinical

outcome data were obtained from a publication on general cancer

prognosis (15). The Prostate

Cancer Transcriptome Atlas (PCTA) database (version, 1.0.1;

http://www.thepcta.org/) was used to analyze

FBXL22 expression and its association with disease progression in

different subtypes of PCa. Patients were stratified based on

clinical features, such as Gleason score (GS) (16) and clinical stage and survival

analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank

tests (https://kmplot.com/analysis/).

Immuno-infiltration and immune

checkpoint gene co- expression analysis in PCa

Infiltration of the 24 immune cell types was

quantified using the ‘ssGSEA’ algorithm in the ‘GSVA’ R package (R

Development Core Team; version 1.52.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GSVA.html).

Spearman's correlation analysis was performed to examine the

relationship between FBXL22 expression and immune cell infiltration

matrix data as well as immune checkpoint protein expression in the

dataset.

Functional enrichment analysis of

FBXL22 in PCa

Patients were classified into high and low FBXL22

expression groups (low, 0–50%; high, 50–100%) for enrichment

analysis using the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ (version 4.10.0; R

Development Core Team; http://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler/).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the

‘clusterProfiler’ and ‘msigdbr’ packages (version 7.5.1; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/msigdbr/index.html)

and the MSigDB gene collection database. For GO/KEGG analysis of

differentially expressed genes, significance thresholds were an

adjusted P-value <0.05 and a minimum gene count of 5. For GSEA,

gene sets with a false discovery rate <0.25 and a nominal

P-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Cell culture and transfection

Human normal prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1) and

PCa cell lines (DU145 and PC3) were obtained from Procell Life

Science and Technology Co., Ltd. and cultured in DMEM (cat. no.

D6429; MilliporeSigma) or F-12K medium (cat. no. 21127022; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no.

A5670701; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) under standard conditions

(37°C; 5% CO2). Human natural killer (NK) cells (cat.

no. CP-H168), also from Procell Life Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd., were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. 11875093;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% FBS under the same

conditions. The human FBXL22 gene was amplified using forward (F)

primer 5′-TACCGAGCTCGGATCCATGTGGCCACTCTGCACCATG-3′ and reverse (R)

primer 5′-GATATCTGCAGAATTCTCACTGCGGGAACGCATCCG-3′, then subcloned

into a pcDNA3.1 (+) mammalian expression vector (cat. no. V79020;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to generate the

recombinant plasmid pcDNA3.1-FBXL22. The empty vector pcDNA3.1

served as a negative control (NC) and both were provided by

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd. (cat. no. RM09014P). For transfection,

cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of

5×104 cells per well and cultured until they reached 80%

confluence. Lipofectamine® 3000 (cat. no. L3000001;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used as the transfection

reagent. A mixture of 25 µl Opti-MEM I medium and 0.5 µl

Lipofectamine® 3000 reagent was prepared. Meanwhile, 1

µl P3000TM reagent and 25 µl Opti-MEM I medium were added to 2 µg

pcDNA3.1-FBXL22 or pcDNA3.1-NC plasmid DNA. The two solutions were

subsequently combined and incubated at 25°C for 10 min. The

resulting 50 µl complex was added to the cell culture medium,

followed by a 48 h incubation at 37°C. After 48 h, the medium was

replaced with fresh complete medium. All functional assays were

performed 48 h post-transfection. Successful transfection was

confirmed using reverse transcription (RT)-quantitative (q)PCR and

western blotting.

Cell viability, invasion and migration

assays

At 48 h post-transfection, cell viability was

assessed using a Cell Counting Kit (CCK-8; cat. no. A50298; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) assay following a 24 h incubation with the

CCK-8 reagent. Transwell invasion assays were performed using

24-well chambers (cat. no. 3378; Corning, Inc.,). The polycarbonate

membrane of the upper chamber was coated with 100 µl Matrigel (cat.

no. M8370; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

diluted 1:8 in serum-free DMEM at 4°C and polymerized for 0.5–1 h

at 37°C. The upper chamber was seeded with ~5×105 cells

in 200 µl serum-free DMEM. The lower chamber contained 500 µl

medium with 20% FBS. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5%

CO2. The membrane was fixed with 600 µl of 4% tissue

cell fixative (cat. no. P1110; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20–30 min at room temperature. After

discarding the fixative, cells were stained with 0.1–0.2% crystal

violet (cat. no. G1062; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 5–10 min at room temperature. Excess stain was

rinsed with PBS. Invasive cells in the lower membrane surface were

imaged using an inverted light microscope (model ICX41; Ningbo

Sunny Instruments Co., Ltd.) with a 50 µm scale bar. For the wound

healing assay, prostate cancer cell lines (DU145 and PC3) were

seeded in 6-well plates (Shanghai Kejin Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at

a density of 5×105 cells per well and cultured until a

confluent monolayer had formed. Vertical scratches were created

across the monolayer using a sterile 20 µl pipette tip, aligned

with pre-marked horizontal lines on the back of the plate to ensure

consistent observation points. After scratching, cells were washed

with PBS (cat. no. C3580-0500; VivaCell; Shanghai XP Biomed Ltd.)

2–3 times to remove detached cells and then incubated in serum-free

DMEM. Images of the scratches were captured immediately at 0 h

using an inverted light microscope (model ICX41; Ningbo Sunny

Instruments) at 40× magnification. Cells were further cultured at

37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, with additional images taken

at 24 h under the same 40× magnification. The healing rate was

quantified by measuring the change in scratch width using ImageJ

1.5.2a software (National Institutes of Health).

NK cell co-culture system with DU145

and PC3 PCa cell lines

NK cells were labeled with CellTracker™ Green CMFDA

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and co-cultured with

FBXL22-overexpressing or control DU145/PC3 cells in a Transwell

system (Corning, Inc.) with a pore size of 0.4 µm. The upper

chamber contained 1×105 NK cells in RPMI-1640 medium

without FBS and the lower chamber contained 2×105 PCa

cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 48 h of

co-culture, the Transwell membranes were first fixed with 600 µl of

4% tissue cell fixative (cat. no. P1110; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 20–30 min.

Following fixation, the membranes were stained with 0.1–0.2%

crystal violet (cat. no. G1062; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 5–10 min. Excess

stain was removed by rinsing with PBS three times. Analyzed for NK

cell migration and cytotoxic activity against PCa cells. For

Transwell assays assessing NK cell migration, the upper chamber

contained 1×105 NK cells in RPMI-1640 medium without

FBS, while the lower chamber contained RPMI-1640 medium with 10%

FBS. After 48 h, the membranes were processed for analysis.

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis was analyzed using an Annexin V-FITC/PI

Apoptosis Detection Kit (cat. no. CA1020; Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, transfected DU145 and PC3 cells were harvested by

trypsinization with EDTA-free trypsin (cat. no. C0205; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min at

4°C, and washed twice with cold PBS. The cell pellet was

resuspended in 1× binding buffer (10× binding buffer diluted 1:9

with deionized water) to a density of 1–5×106 cells/ml.

A 100 µl aliquot of the cell suspension was incubated with 5 µl

Annexin V-FITC in the dark at room temperature (25°C) for 15 min.

Subsequently, 5 µl PI solution and 400 µl PBS were added and

samples were immediately analyzed using a FACSCanto™ flow cytometer

(BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the FlowJo software

(v10.8.1; FlowJo LLC; BD Biosciences).

Gene expression

FBXL22 mRNA was quantified by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). RNA was extracted from

transfected DU145, PC3, and RWPE-1 cells using TRNzol (cat. no.

DP424; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Concentration/purity was

measured via NanoDrop One/OneC (cat. no. 840-317400; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; A260/280=1.8–2.0). cDNA was

synthesized with FastKing One-Step SuperMix (cat. no. KR118;

Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.; 20 µl; 4 µl 5× SuperMix; 2 µg RNA;

RNase-free water). The thermal cycling protocol was conducted as

follows: An initial step at 42°C for 15 min, followed by heat

inactivation at 95°C for 3 min and a final hold at 4°C for 30 min.

RT-qPCR was performed using a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System

(cat. no. 4376600; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with SYBR™ Green

Master Mix (cat. no. G3320-15; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) or SuperReal Premix Plus (cat. no. FP205; Tiangen Biotech

Co., Ltd.). Each 20 µl reaction mixture contained 10 µl 2× Premix,

0.6 µl forward and reverse primer each (10 µM), 2 µl of cDNA

template, and was made up to the final volume with nuclease-free

water. The following thermocycling conditions were used: 95°C 15

min; 40× (95°C 10 sec; 60°C 32 sec). A melting curve analysis was

performed immediately after the amplification cycles to confirm the

specificity of the PCR products and the absence of primer-dimers.

Expression calculated via 2−ΔΔCq (17) with β-actin control. Primers

sequences were as follows: FBXL22, Forward

5′-CCATGCACATAACCCAGCTCA-3′; Reverse (R),

5′-CCGAGGTGATTTCGGTCCAAC-3′; β-actin F,

5′-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3′; R, 5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′.

Western blotting

Protein levels were determined using western

blotting. Total protein was extracted from cells using RIPA lysis

buffer (cat. no. R0010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) and quantified with a BCA assay kit (cat. no. BL521A;

Biosharp Life Sciences). An equal amount (30 µg) of protein per

sample was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then electrophoretically

transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5%

non-fat milk in TBST (containing 0.1% Tween 20), for 2 h at room

temperature. After primary antibody incubation (4°C; overnight;

Table SI) and three washes with

TBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies: Goat

anti-rabbit IgG H and L (HRP) (cat. no. ab97051; Abcam) or

HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (cat. no. AS003; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.), both at a 1:10,000 dilution, for 1 h at room

temperature. Signals were detected using an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. P10300; Suzhou Xinsaimei

Biotechnology Co., Ltd) and visualized with a multi-functional

imaging system (SH-CUTE523; Zhehiang ICP; Table SII).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

An immunoprecipitation kit (cat. no. P2179S)

purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology was used for the

experiment. Transfected PC3 and DU145 cells (1×107) were

collected and lysed on ice with 500 µl lysis buffer (provided in

the kit) for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10

min at 4°C to pellet cellular debris and the protein concentration

of the supernatants was determined using a BCA assay (cat. no.

BL521A; Biosharp Life Sciences). A small amount of lysate (50 µl)

was incubated with 20 µl protein A/G agarose beads (pre-treated

with lysis buffer) at 4°C for 1 h to block non-specific binding.

For immunoprecipitation, 500 µl lysate (containing ~500 µg total

protein) was incubated with 1 µg anti-FBXL22 primary antibody (cat.

no. ab223059; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, 40 µl

pre-treated protein A/G agarose beads were added and incubated at

4°C for 2 h. The samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 3

min and the beads were collected and rinsed with elution buffer.

Finally, the bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 2X

SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 95°C for 10 min. Western blotting was

performed on the eluent to analyze the co-precipitated

proteins.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R

software and GraphPad Prism 9.5.1(Dotmatics). Gene expression

differences were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum (for two-group

comparisons) and Kruskal-Wallis tests (for multi-group

comparisons). For significant results using Kruskal-Wallis tests

(P<0.05), post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using

Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction. Correlations were assessed

using Spearman's or Pearson's correlation analysis. Survival

characteristics were compared using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox

regression analysis. For the KM plotter, mRNA expression data were

used; and patients were stratified into high and low FBXL22

expression groups using the 50th percentile (median) as the cut-off

(low, 0–50%; high, 50–100%). Data were represented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 were considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

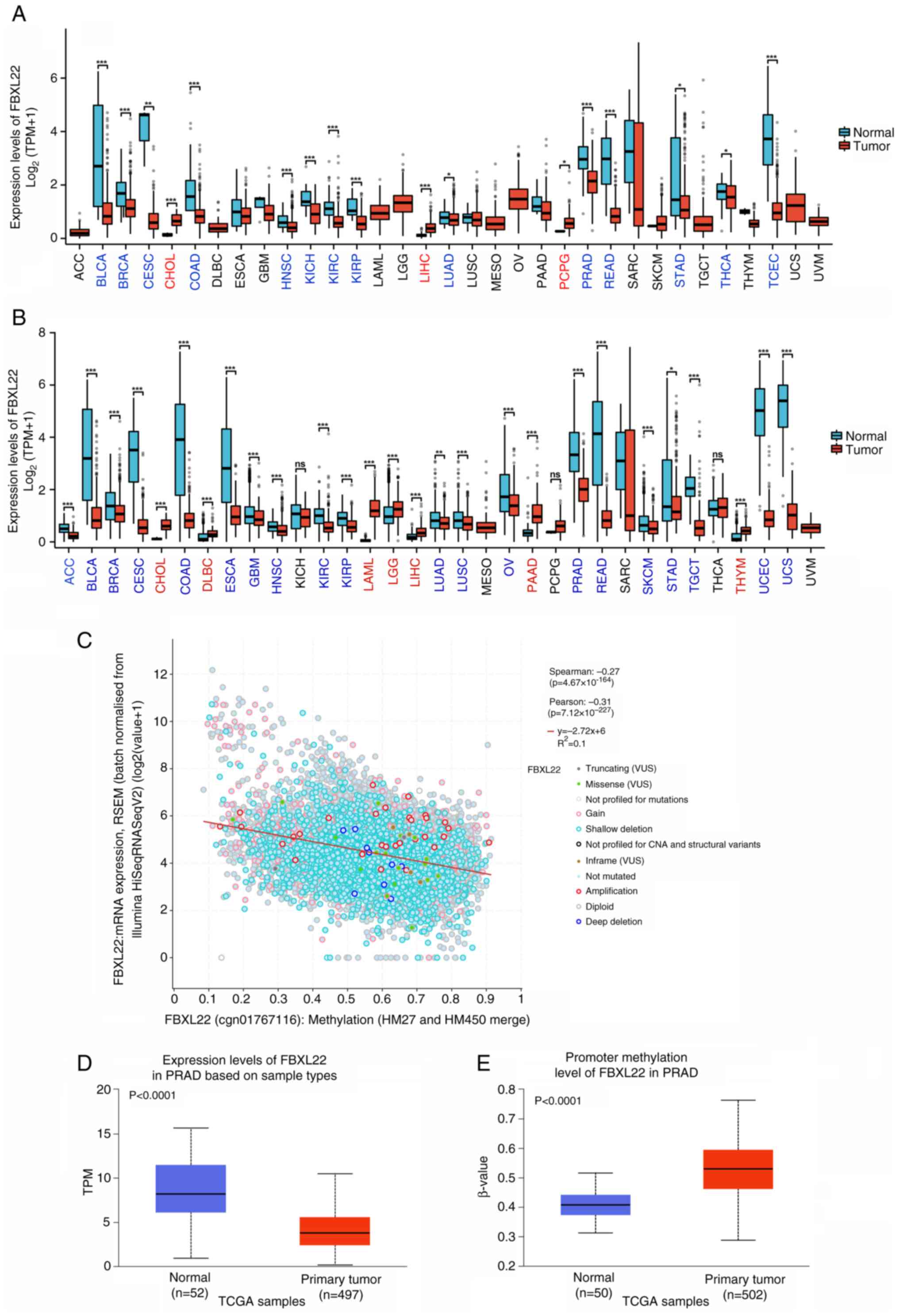

Pan-cancer expression and epigenetic

regulation of FBXL22

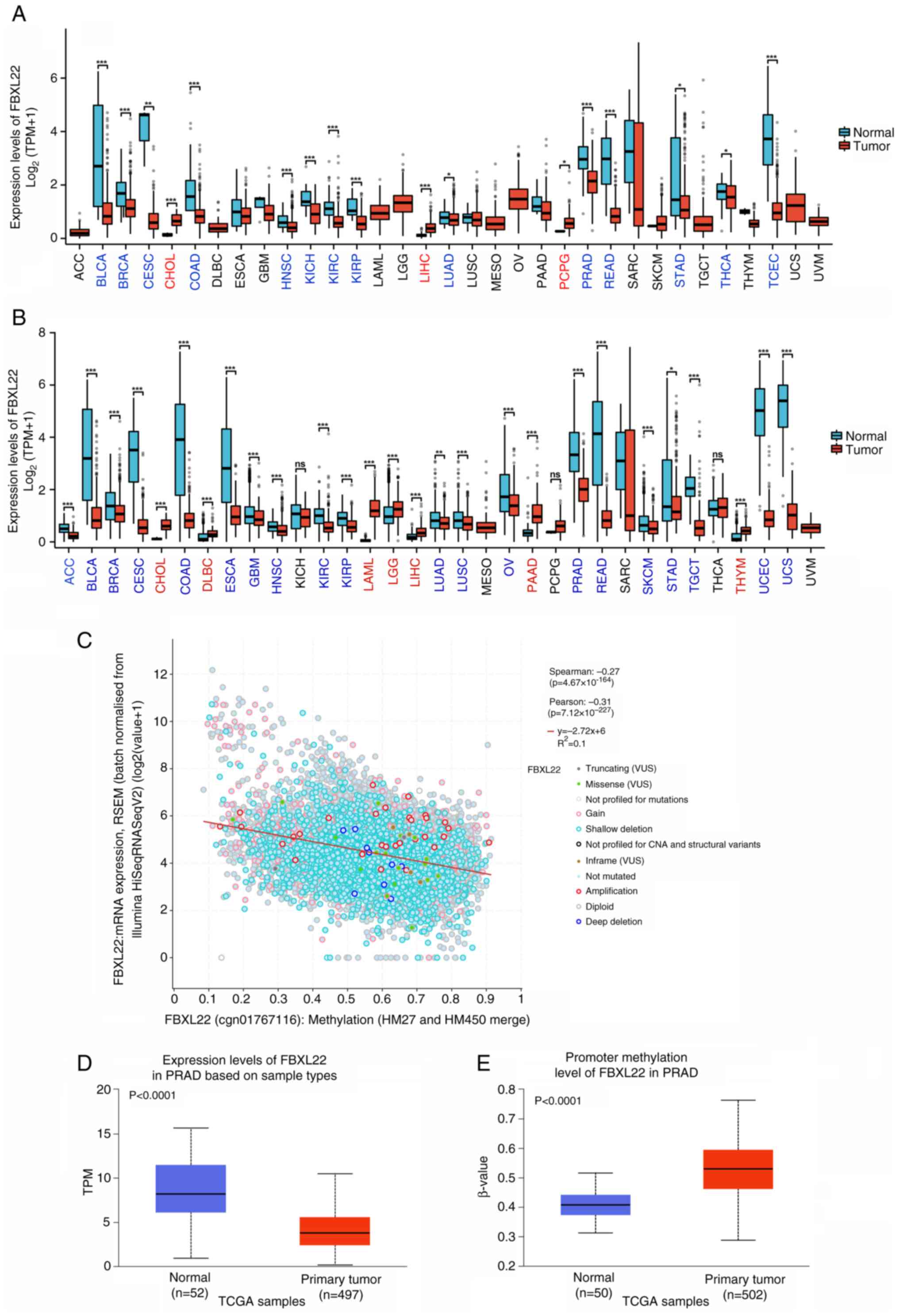

FBXL22 was differentially expressed in 33 cancer

types when compared with corresponding normal tissues. FBXL22 was

significantly downregulated in 19 cancer types, including uterine

carcinosarcoma (P<0.0001), endometrial carcinoma (UCEC;

P<0.0001) and colon adenocarcinoma (COAD; P<0.0001), but

overexpressed in seven cancer types such as cholangiocarcinoma

(CHOL; P<0.0001) and acute myeloid leukemia (LAML; P<0.0001)

(Fig. 1A and B). When comparing

tumor tissues with the corresponding normal tissues from TCGA and

GTEx databases, significant variations in FBXL22 expression were

observed in 26 cancer types (P<0.05), with the exception of

kidney chromophobe, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma and thyroid

carcinoma (THCA) (Fig. 1B). This

comparison highlights the distinct expression levels of FBXL22 in

neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic tissues and provides a foundation for

understanding its potential role in cancer. However, it should be

noted that expression levels in normal tissues were based on the

GTEx database and these data should be interpreted with caution

because of the potential differences in tissue collection and

processing methods between TCGA and GTEx.

| Figure 1.Expression levels of FBXL22 in

pan-cancer. (A) The expression status of FBXL22 in different cancer

tissues and para-cancerous tissues in TCGA database. Error bars

represent standard deviation. (B) Expression status of FBXL22 in

matched cancer tissues and normal tissues in TCGA and GTEx

databases. Cancer names in red text indicate high FBXL22 expression

in this cancer, while blue text indicates low FBXL22 expression in

this cancer. (C) Correlation between FBXL22 expression and

methylation in TCGA database (D) Promoter methylation levels of

FBXL22 in PRAD samples. (E) Expression differences of FBXL22 in

PRAD samples based on sample types. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ns, P≥0.05. FBXL22, F-box and leucine rich repeat

protein 22; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder urothelial

carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, cervical squamous

cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; CHOL,

cholangiocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; DLBC, lymphoid

neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma;

GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma; KICH, kidney chromophobe; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell

carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute

myeloid leukemia; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LIHC, Liver

hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, Lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung

squamous cell carcinoma; MESO, mesothelioma; ns, not significant;

OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic

adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD,

prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SARC,

sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach

adenocarcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TGCT, testicular

germ cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; THYM, thymoma; TMB,

tumor mutation burden; TPM, transcripts per million; UCEC, uterine

corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma. |

A strong negative correlation between FBXL22

expression and promoter methylation was observed (P<0.0001,

Spearman's ρ=−0.27; Pearson's r=−0.31; Fig. 1C). Elevated methylation levels in

tumors vs. normal tissues were prominent in kidney renal papillary

cell carcinoma, breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), THCA and PRAD

(P<0.0001), whereas reduced methylation was observed in

glioblastoma multiforme, liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) and

pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) (Figs.

1D and S1). In PCa, FBXL22

demonstrated significant promoter hypermethylation (P<0.0001)

and downregulation (P<0.0001) (Figs.

1D, E and S2).

Genomic alterations and mutation

frequency of FBXL22

Genomic alterations in FBXL22 were observed in 26

cases across 12 cancer types, with a somatic mutation frequency of

0.2% (Fig. S3). Among the various

cancer types, UCEC exhibited the highest mutation frequency of 1.7%

(9/529 cases), followed by stomach adenocarcinoma [STAD; 1.14%

(5/440 cases)] (Fig. S3). Missense

mutations were the predominant type of genetic alteration observed.

However, no significant correlation was found between FBXL22

expression levels and mutation types or copy number alteration

(Fig. S4; Table SIII; P>0.05). Although genomic

alterations of FBXL22 were identified across several cancer types,

the overall mutation frequency was relatively low. This suggested

that while genetic mutations can occur in FBXL22, they may not be

the primary driver of its expression changes in most cancer

types.

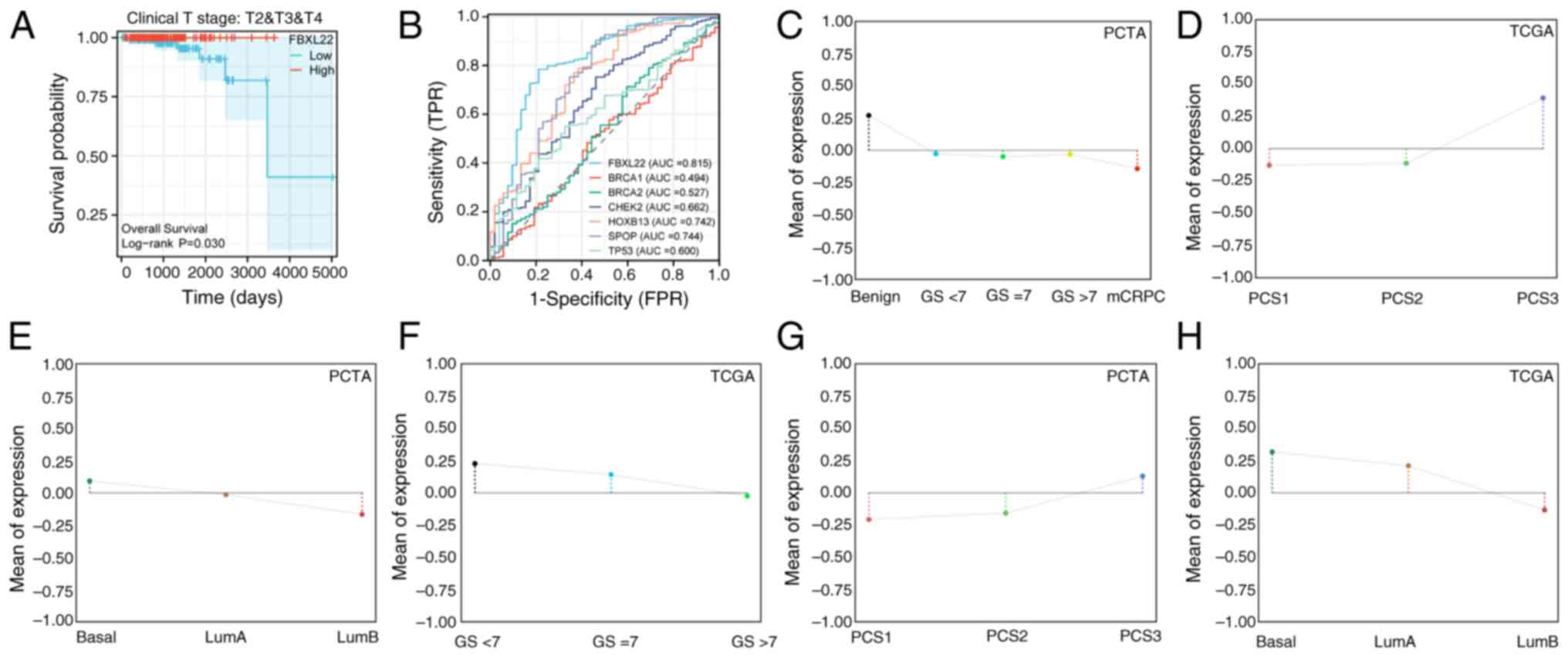

Survival analysis and prognostic

implications of FBXL22

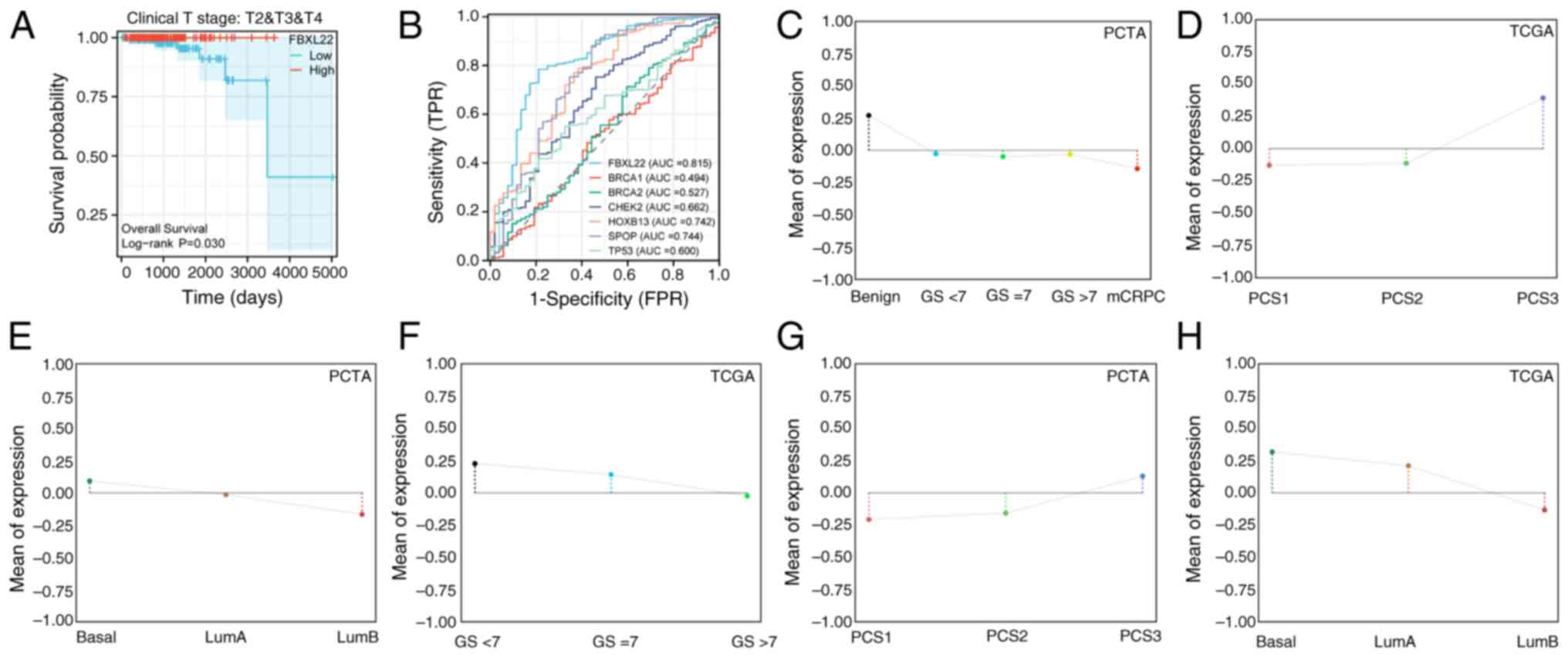

Survival analysis revealed that elevated FBXL22

expression was significantly associated with worse overall survival

(OS) in bladder cancer (BLCA; P<0.01) and STAD (P<0.05),

whereas low expression predicted unfavorable recurrence-free

survival in THCA (P<0.05) (Fig. 2A

and B). Kaplan-Meier validation across 21 cancer types

(n=7,489) further demonstrated that low FBXL22 expression

correlated with worse OS in esophageal adenocarcinoma (P<0.05)

and PAAD (P<0.05), whereas high expression remained a prognostic

factor for poor OS in BLCA (P<0.05) and STAD (P<0.05)

(Fig. S5). Notably, FBXL22

expression exhibited significant associations with PCa

clinicopathological features: Higher levels were observed in

patients with GS ≤7 (Fig. 2C and F;

P<0.001) and advanced clinical stages (Fig. 2D; P<0.05) and metastatic

castration-resistant PCa (Fig.

2E-G, P<0.001) and luminal B Prediction Analysis of

Microarray 50 subtypes (Fig. 2H,

P<0.001). Collectively, these findings underscore the key

relationship between FBXL22 expression and PCa progression markers

(GS, staging and molecular subtypes), which suggests it has a

potential role as a biomarker and functional driver in disease

progression.

| Figure 2.Clinical diagnosis and prognostic

implications of FBXL22 in PCa. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve of PFI in

patients with intermediate to advanced disease stage (Clinical T

stage, T2, T3 and T4) in PCa by FBXL22-expression groups. (B)

Diagnostic ROC curves of FBXL22 and other genes such as SPOP,

HOXB13, CHEK2, TP53, BRCA2 and BRCA1 in PCa. (C) FBXL22 expression

across PCa disease course subtypes. (D) FBXL22 expression in PCS

subtypes. (E) FBXL22 expression in basal, LumA and LumB subtypes.

(F) FBXL22 expression across GS subgroups. (G) FBXL22 expression in

PCS subtypes. (H) FBXL22 expression in basal, LumA and LumB

subtypes. FBXL22, F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 22; PCa,

prostate cancer; PFI, progression-free interval; ROC, receiver

operating characteristic; SPOP, Speckle-type pox virus and zinc

finger protein; HOXB13, homeobox B13; CHEK2, checkpoint kinase 2;

PAM50, Prediction Analysis of Microarray 50; PCTA, Prostate Cancer

Transcriptome Atlas; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; PCS, PCa

subtypes; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; Lum, luminal; GS,

Gleason score; TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive rate;

AUC, area under the curve. |

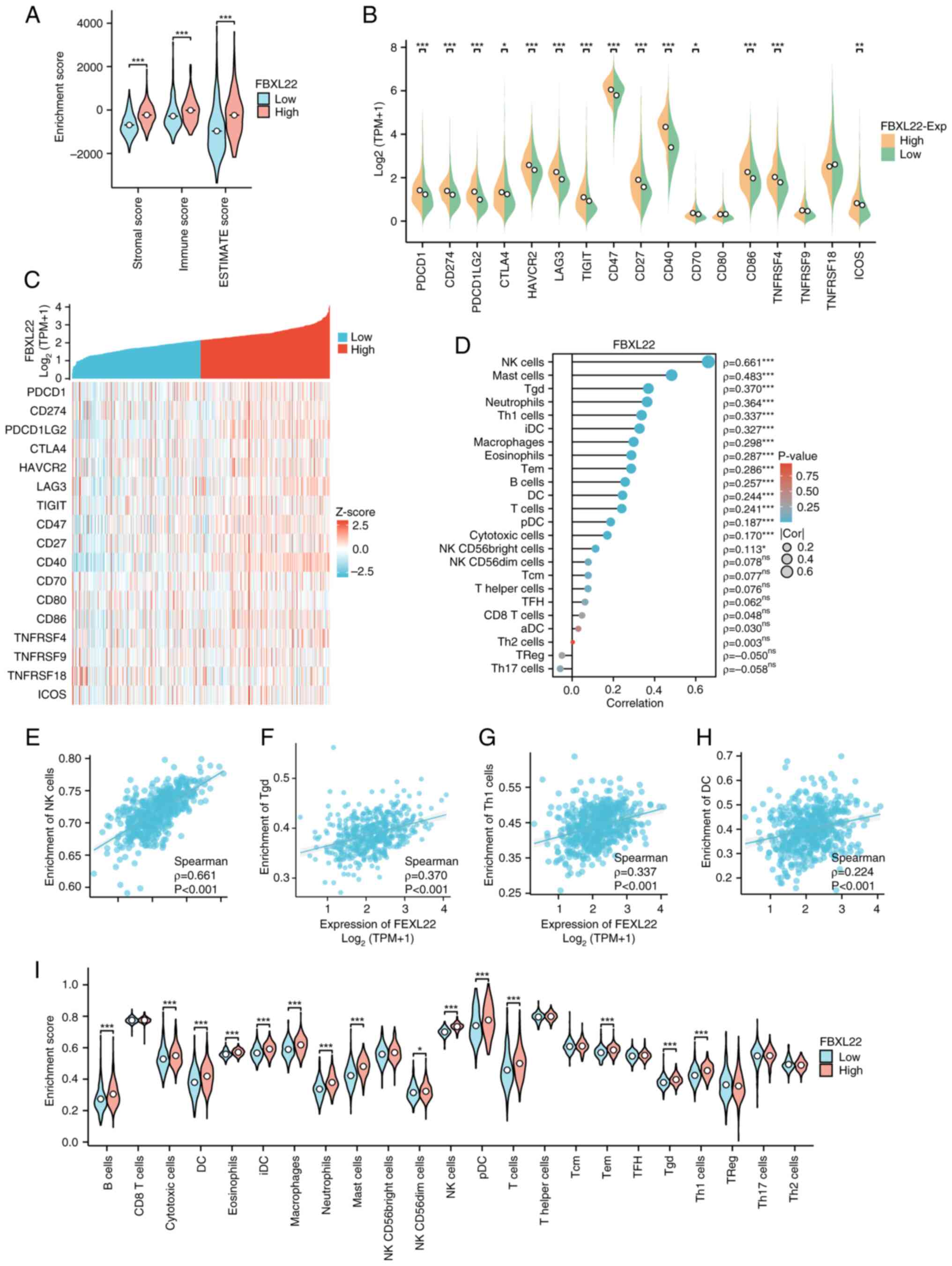

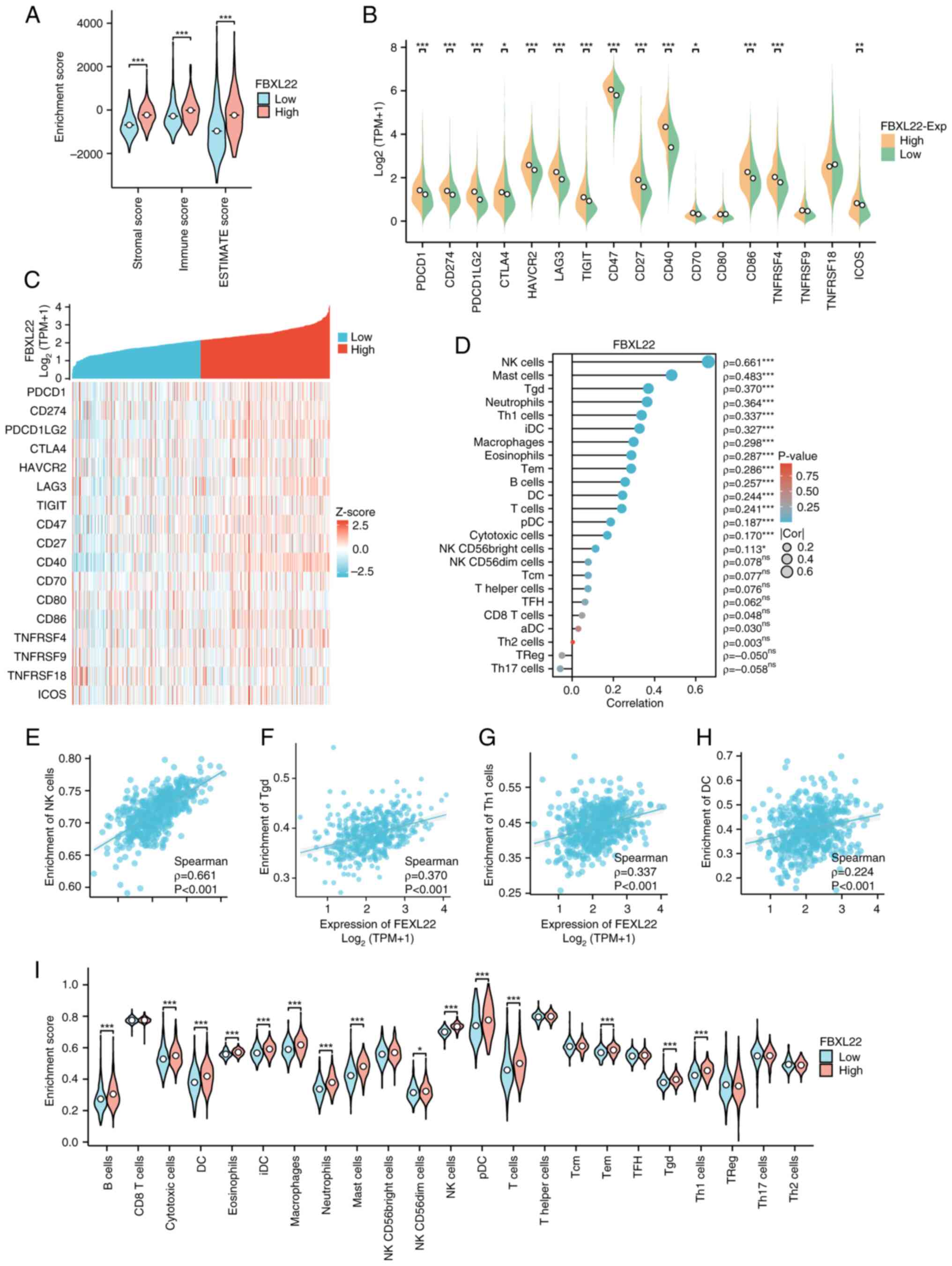

FBXL22 immune activation and TME

Comprehensive analyses revealed a significant

association between FBXL22 expression and TME dynamics (Figs. 3 and S6). Violin plots demonstrated that

FBXL22-high tumors exhibited markedly elevated enrichment scores

across diverse immune cell populations (P<0.05; Wilcoxon test),

particularly in cytotoxic subsets, including NK and CD8+

T cells (Fig. 3A and I). Consistent

with this immune-activated phenotype, key immunoregulatory markers

[programmed cell death 1 (PDCD1), CD274 and PDCD1 ligand 2]

demonstrated 2.1- to 3.4-fold higher expression in FBXL22-high

samples [log2(TPM+1); P<0.01; Fig. 3B]. Heatmap analysis further

demonstrated strong co-expression patterns between FBXL22 and

immune checkpoint regulators (Pearson's r=0.62–0.71; Z-score

normalized; Fig. 3C). Quantitative

correlation analyses revealed dose-dependent relationships between

FBXL22 expression and infiltration densities of antitumor immune

subsets, including significant associations with NK cells

(Spearman's ρ=0.57; P<0.00001), CD8+ T cells (r=0.49;

P<0.001), Th1 cells (r=0.43; P<0.001) and dendritic cells

(r=0.38; P<0.01; Fig. 3D-H).

These multimodal findings collectively suggest that FBXL22 is a

potential immunomodulatory hub with high expression levels

correlating with enhanced immune infiltration and checkpoint

activation, which suggests it has functional involvement in shaping

antitumor immune responses.

| Figure 3.Association of FBXL22 with

immune-infiltration in PCa. (A) The immune score of

FBXL22-expression groups. (B) Expression levels of the 17 immune

checkpoint proteins by FBXL22-expression group. (C) Heatmap

illustrating correlations between FBXL22 expression and 17 immune

checkpoint proteins. (D) Correlation between FBXL22 expression and

the infiltration levels of various immune cells. Scatter plot of

correlation between FBXL22 expression and the infiltration levels

of (E) NK, (F) Tgd, (G) Th1 and (H) DC cells. (I) Infiltration

levels of 23 types of immune cells were assessed by

FBXL22-expression group using ssGSEA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001; ns, P≥0.05. FBXL22, F-box and leucine rich repeat

protein 22; PCa, prostate cancer; NK, natural killer; DC, dendritic

cells; Tgd cells, γδ T cells; Th1 cells, T helper type 1 cells;

Treg, regulatory T cells; ssGSEA, single-sample gene set enrichment

analysis; ESTIMATE, Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in

MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data; TPM, transcripts per

million; ns, not significant. |

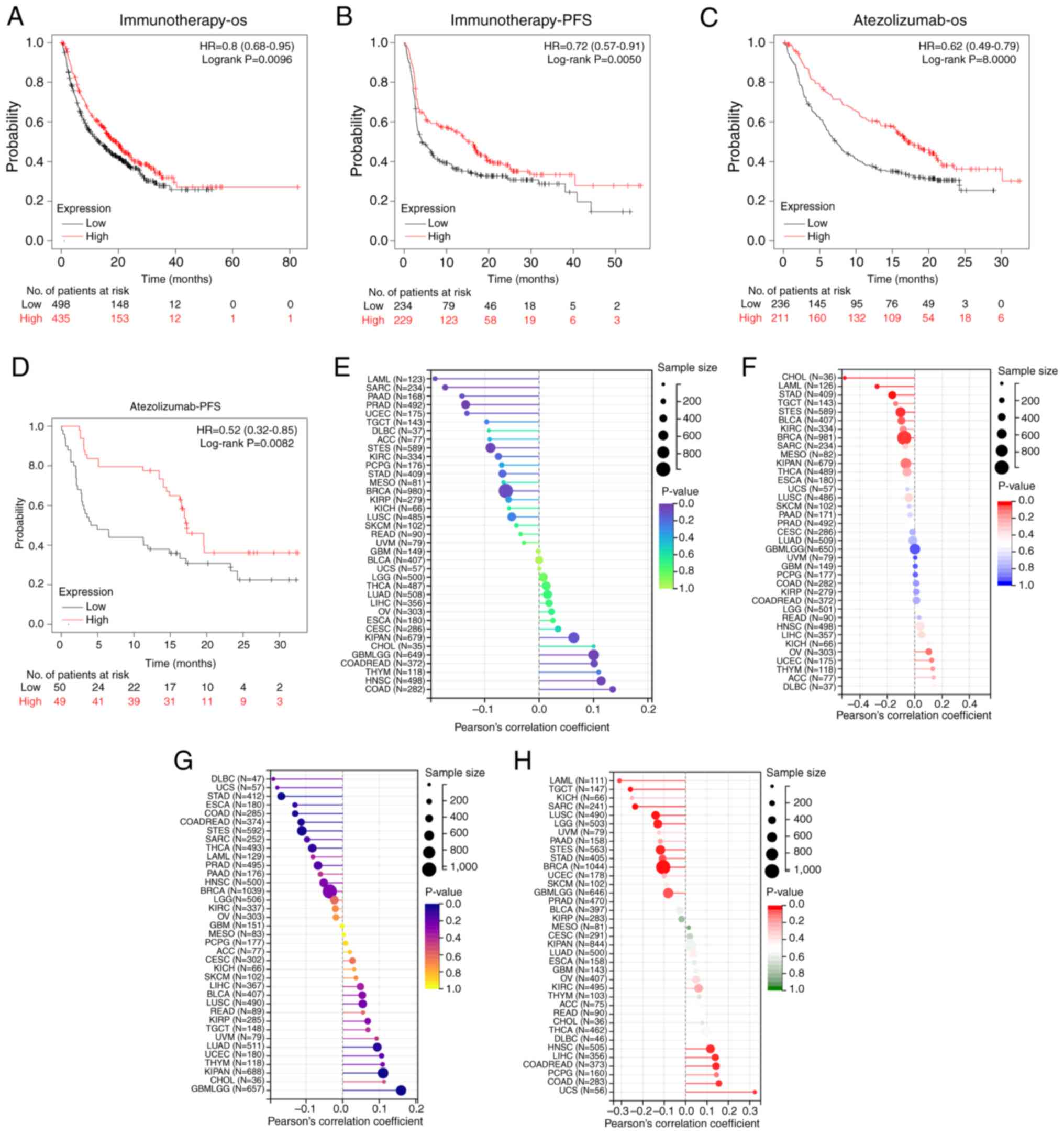

Therapeutic response prediction based

on FBXL22 expression

Low FBXL22 expression was associated with worse OS

(P<0.01) and progression-free survival (PFS; P=0.005) in

immunotherapy-treated patients, whereas high expression predicted

improved outcomes in atezolizumab-treated cohorts (P<0.001 for

OS; P<0.01 for PFS) (Fig. 4A-D).

This suggests that FBXL22 expression may be a predictive biomarker

of therapeutic responses to specific cancer treatments. Notably,

FBXL22 expression was negatively correlated with tumor mutation

burden (TMB) in LAML, BRCA and STAD, and positively correlated with

homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) in COAD and LIHC

(Fig. 4E-H; all P<0.05). The

negative correlation between FBXL22 expression and TMB in certain

cancer types and the positive correlation with HRD in others

further emphasizes its potential as a biomarker for guiding

personalized treatment decisions.

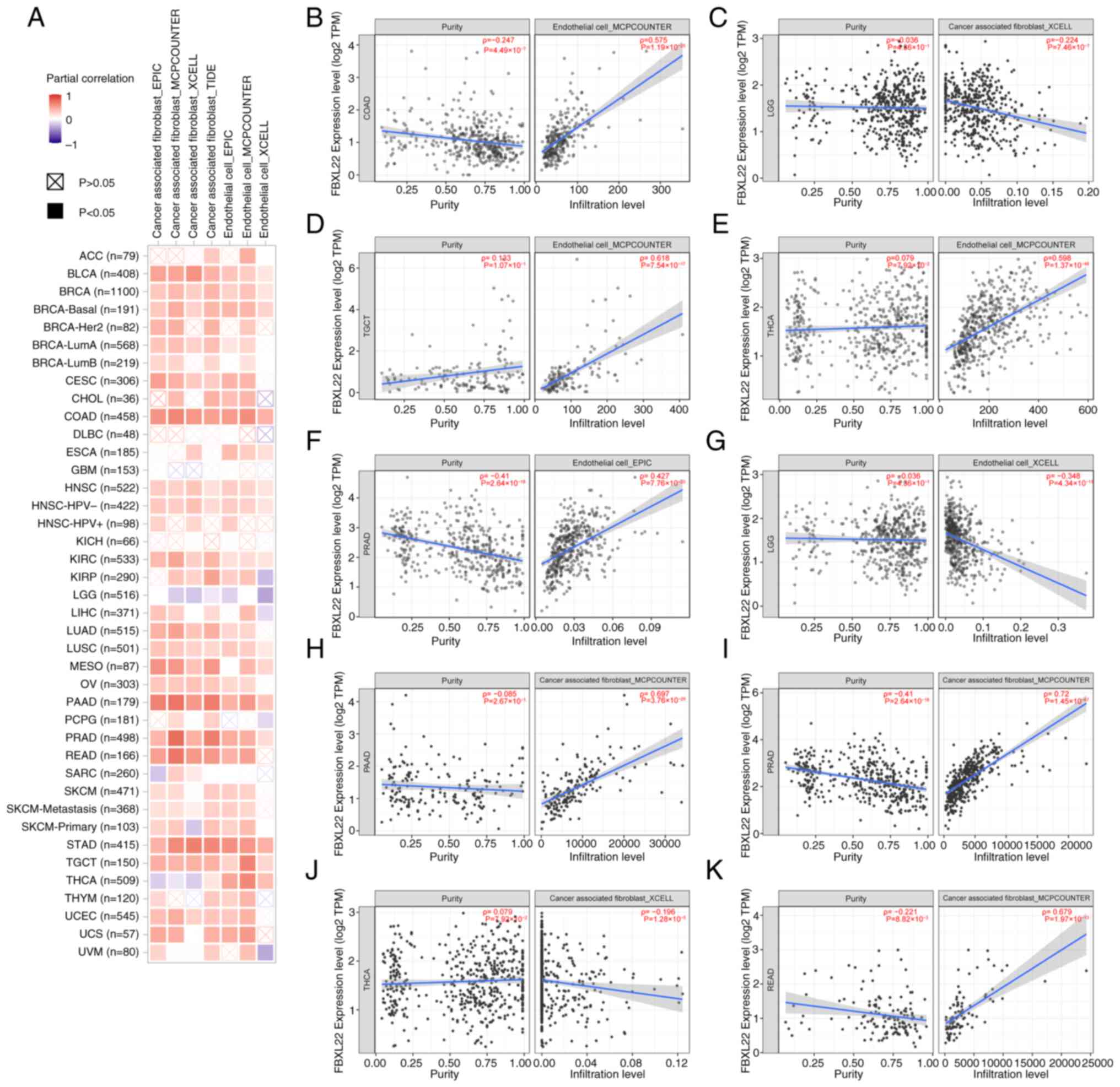

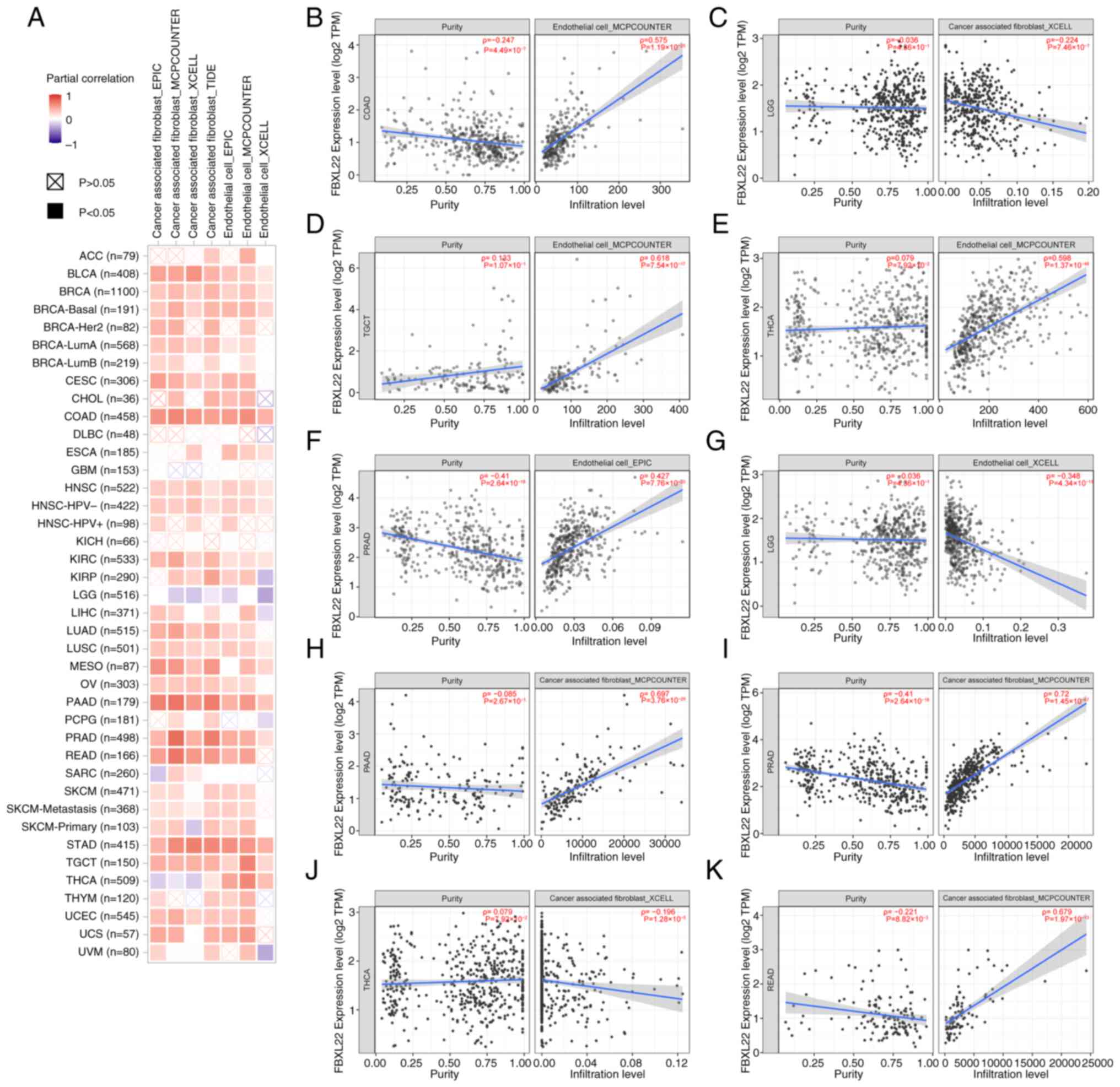

Immune regulatory gene analysis

FBXL22 expression was significantly correlated with

immune checkpoint pathway genes across multiple cancer types,

including positive associations with inhibitory genes [for example,

programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

associated protein 4 (CTLA4)] and stimulatory genes (for example,

CD40 and inducible T-cell co-stimulator) (Fig. S7; all P<0.05). Additionally,

FBXL22 correlated with immunomodulation-related genes such as

chemokines and major histocompatibility complex molecules in uveal

melanoma, READ and PRAD (Fig. S8;

all P<0.05). FBXL22 expression positively correlated with

cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) and endothelial cell (EC)

infiltration in most cancer types, except brain lower grade glioma

(Fig. 5A-K). In THCA, FBXL22

demonstrated a negative correlation with CAFs (ρ=−0.1961;

P<0.0001) but a positive association with ECs (ρ=0.5977;

P<0.0001) (Fig. 5E, J and

K).

| Figure 5.Correlation analysis between FBXL22

expression and immune infiltration of CAFs and ECs across all types

of cancer in TCGA. (A) Corresponding heatmap and (B) COAD, (C) LGG,

(D) TGCT, (E) THCA, (F) PRAD, (G) LGG, (H) PAAD, (I) PRAD, (J)

THCA, (K) READ. Each scatter plot includes data points representing

FBXL22 expression levels (x-axis) and infiltration levels of CAFs

or ECs (y-axis), with a trend line indicating the correlation

direction. Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ) and corresponding

P-value are annotated for each plot to quantify the strength and

significance of the association. FBXL22, F-box and leucine rich

repeat protein 22; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; ECs,

endothelial cells; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TPM, transcripts

per million; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; PRAD, prostate

adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ

cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; LGG, lower grade glioma. |

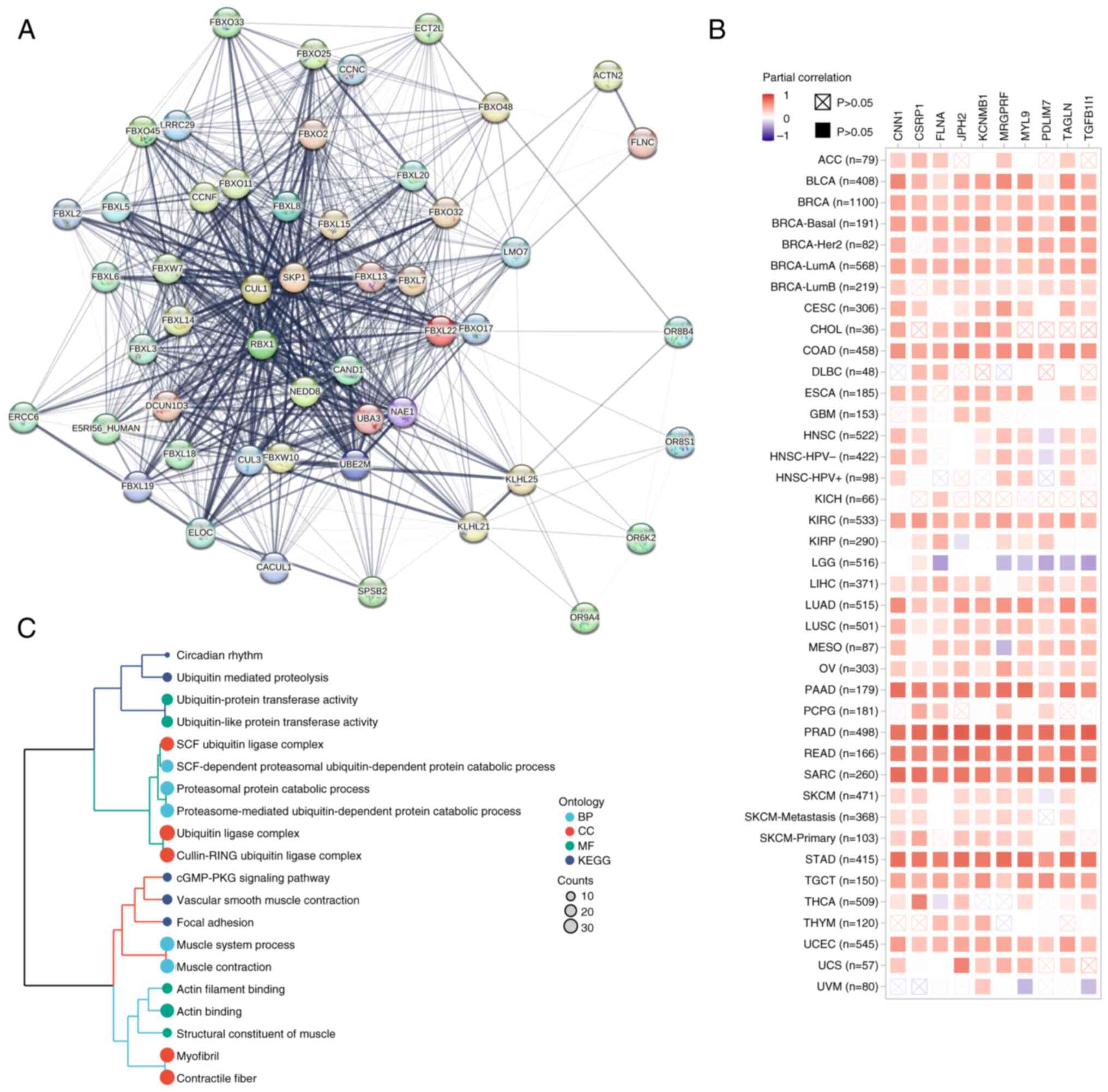

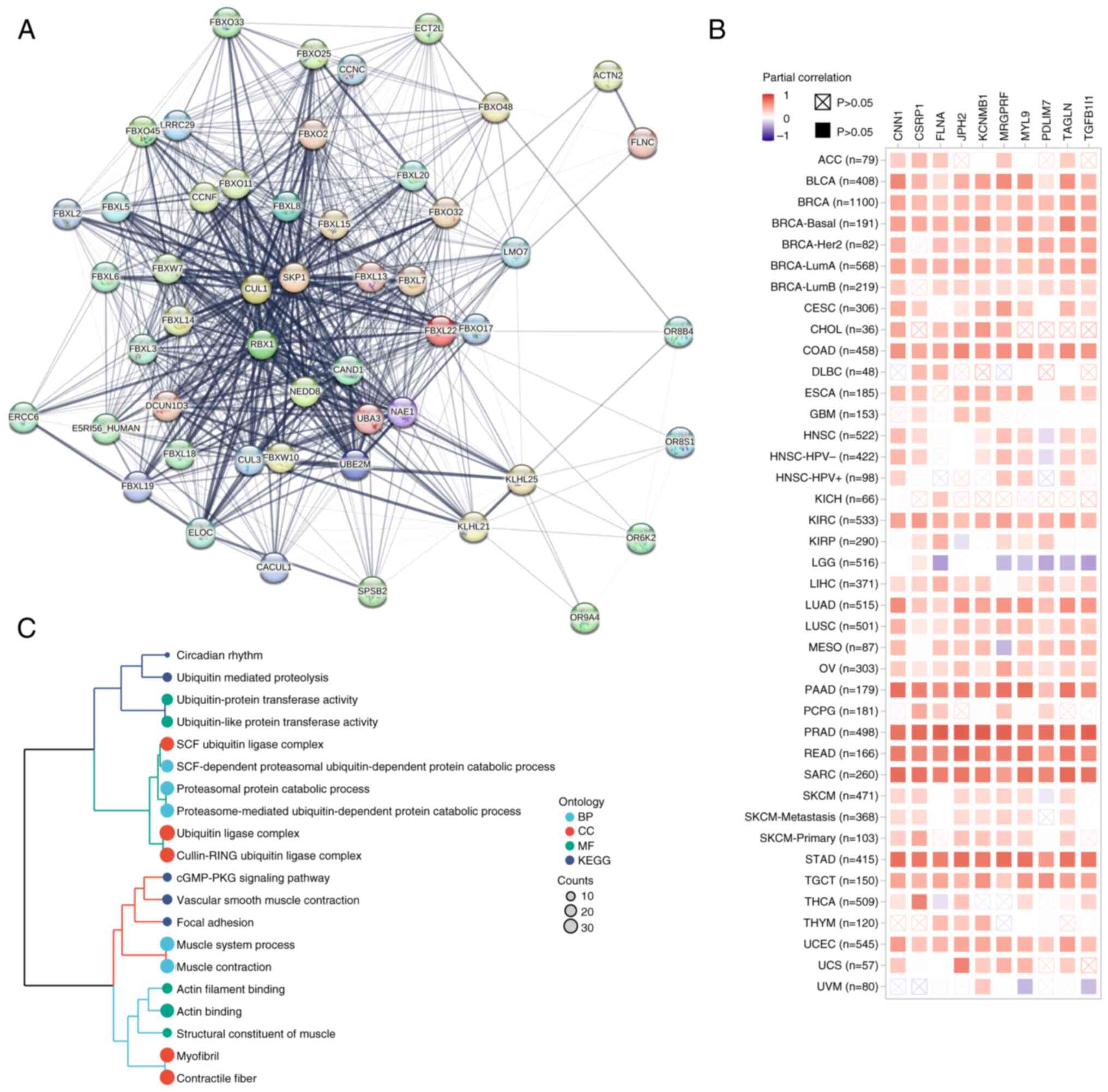

Functional enrichment analysis of

FBXL22-related genes

Protein-protein interaction analysis identified 50

FBXL22-binding partners, including filamin C (Fig. 6A). The top 100 FBXL22-correlated

genes, MRGPRF (r=0.83) and KCNMB1 (r=0.81), were enriched in

pathways such as ‘Circadian rhythm’, ‘Ubiquitin-mediated

proteolysis’ and ‘cGMP-PKG signaling’ (Figs. 6B, C and S9; Table

SIV and SV). These findings

provide insight into the molecular mechanisms by which FBXL22

exerts its effects on cancer cells and the TME.

| Figure 6.FBXL22-related gene enrichment

analysis in pan-cancer. (A) Network of interactions among

FBXL22-binding proteins using the STRING tool. (B) Heatmap of

expression correlations between FBXL22 and the top 10

FBXL22-correlated genes in different cancer types of TCGA using the

GEPIA2 tools, including MRGPRF, KCNMB1, PDLIM7, TAGLN, TGFB1I1,

JPH2, CNN1, FLNA, CSRP1 and MYL9. (C) KEGG and GO enrichment

analyses are visualized by cluster tree diagram. FBXL22, F-box and

leucine rich repeat protein 22; STRING, Search Tool for the

Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins; TCGA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; GEPIA2, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2;

MRGPRF, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor F; KCNMB1, potassium

calcium-activated channel subfamily M regulatory β subunit 1;

PDLIM7L, PDZ and LIM domain 7; TAGLN, Transgelin; TGFB1I1,

transforming growth factor β 1 induced 1; JPH2, junctophilin 2;

CNN1, calponin 1; FLNA, filamin A; CSRP1, cysteine and glycine rich

protein 1; MYL9, myosin light chain 9; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene ontology; BP, Biological process; CC,

Cellular component; MF, Molecular function. |

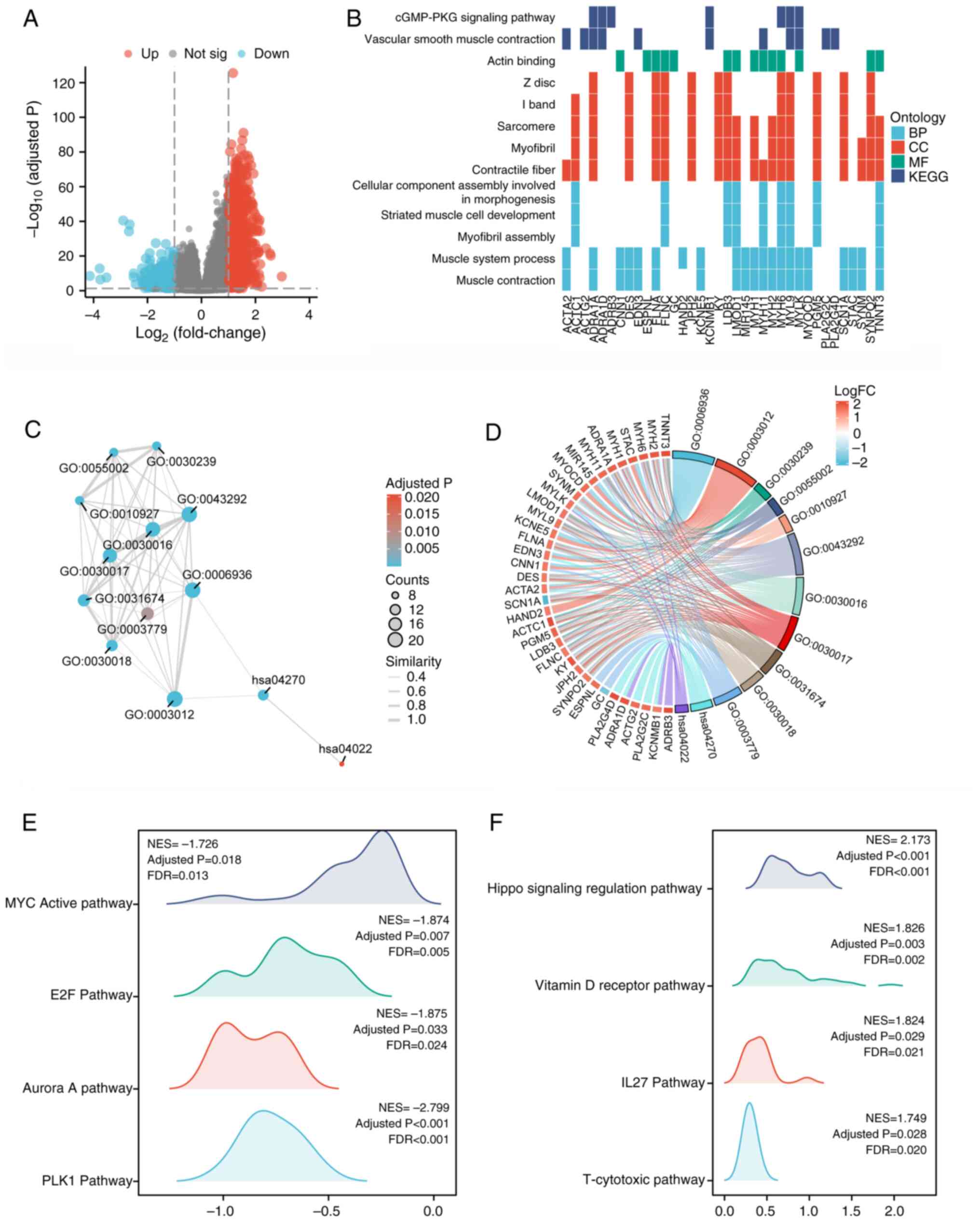

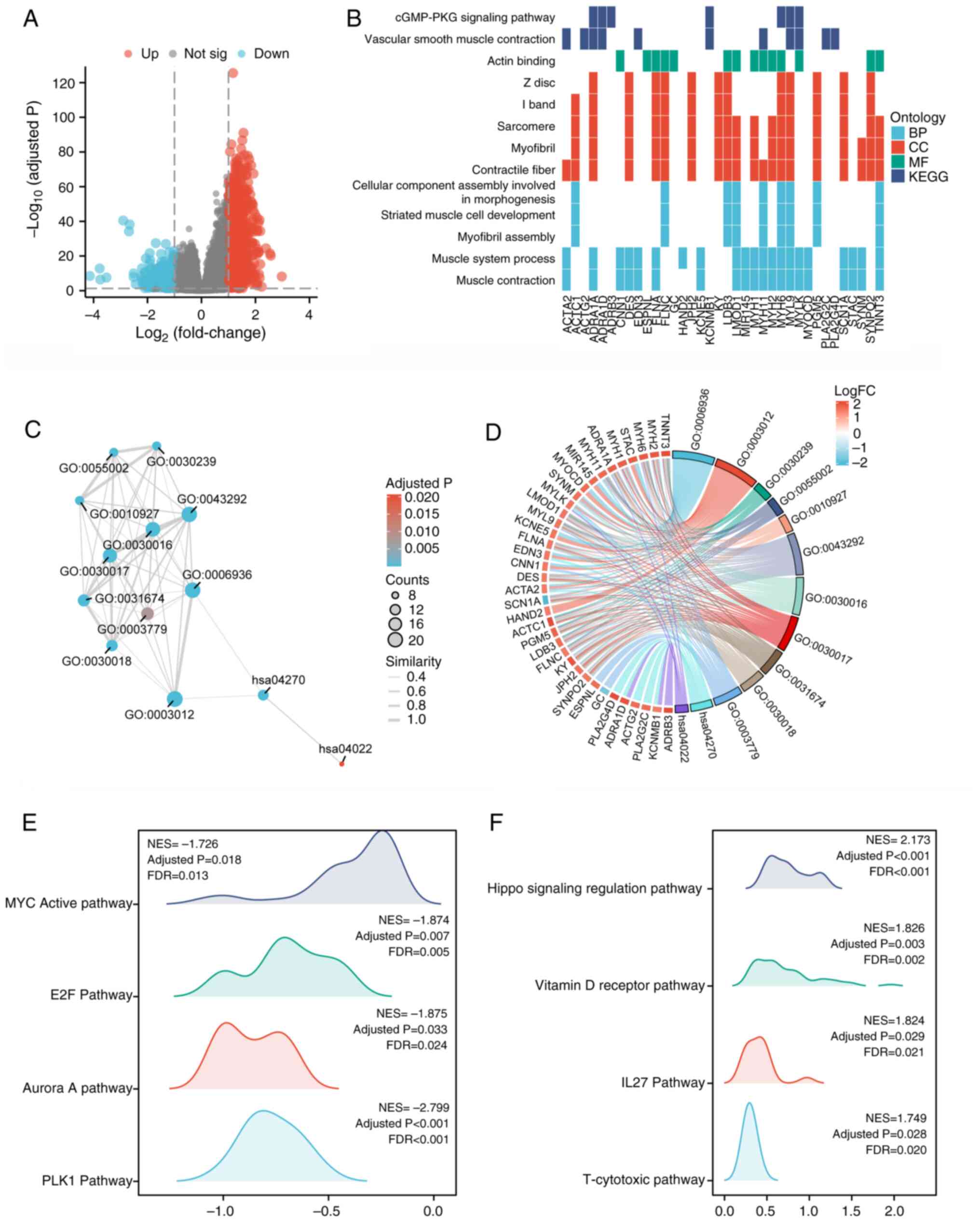

Differential expression and functional

enrichment of FBXL22 in PCa

In PCa, differential expression analysis identified

1,243 upregulated and 1,017 downregulated genes in the high-FBXL22

groups. These genes were enriched in pathways such as ‘Muscle

contraction’ and ‘cGMP-PKG signaling’ (Fig. 7A-D, Table SVI and SVII). GSEA revealed that FBXL22

negatively regulated pro-tumor pathways, such as ‘Myc active’,

‘E2F’ and ‘PLK1’, and were positively associated with

tumor-suppressive pathways, such as ‘Hippo signaling regulation’

and ‘Vitamin D receptor’ (Fig.

7E-F). These results suggested that FBXL22 serves a

tumor-suppressive role in PCa by modulating specific signaling

pathways.

| Figure 7.Differential expression and

functional enrichment analysis of FBXL22-associated genes in

prostate cancer. (A) Volcano plot illustrating differential

expression analysis between high-FBXL22 and low-FBXL22 expression

groups in PCa, which highlights the genes that were significantly

upregulated or downregulated in association with FBXL22 expression

levels. The results of KEGG and GO enrichment analysis are depicted

using (B) heat map and (C) Enrichment Map Analysis Platform,

respectively. (D) The analysis of GO/KEGG combined log(fold change)

is represented by a chordal diagram. The mountain maps display the

pathways (E) significantly negative or (F) significantly positive

associated with expression levels of FBXL22 in GSEA analysis

results. Error bars represent standard deviation. FBXL22, F-box and

leucine rich repeat protein 22; PCa, prostate cancer; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; GSEA, Gene

Set Enrichment Analysis; E2F, E2 DNA-binding factor; PLK1,

polo-like kinase 1; NES, nuclear export sequence; FDR, false

discovery rate; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF,

molecular function. |

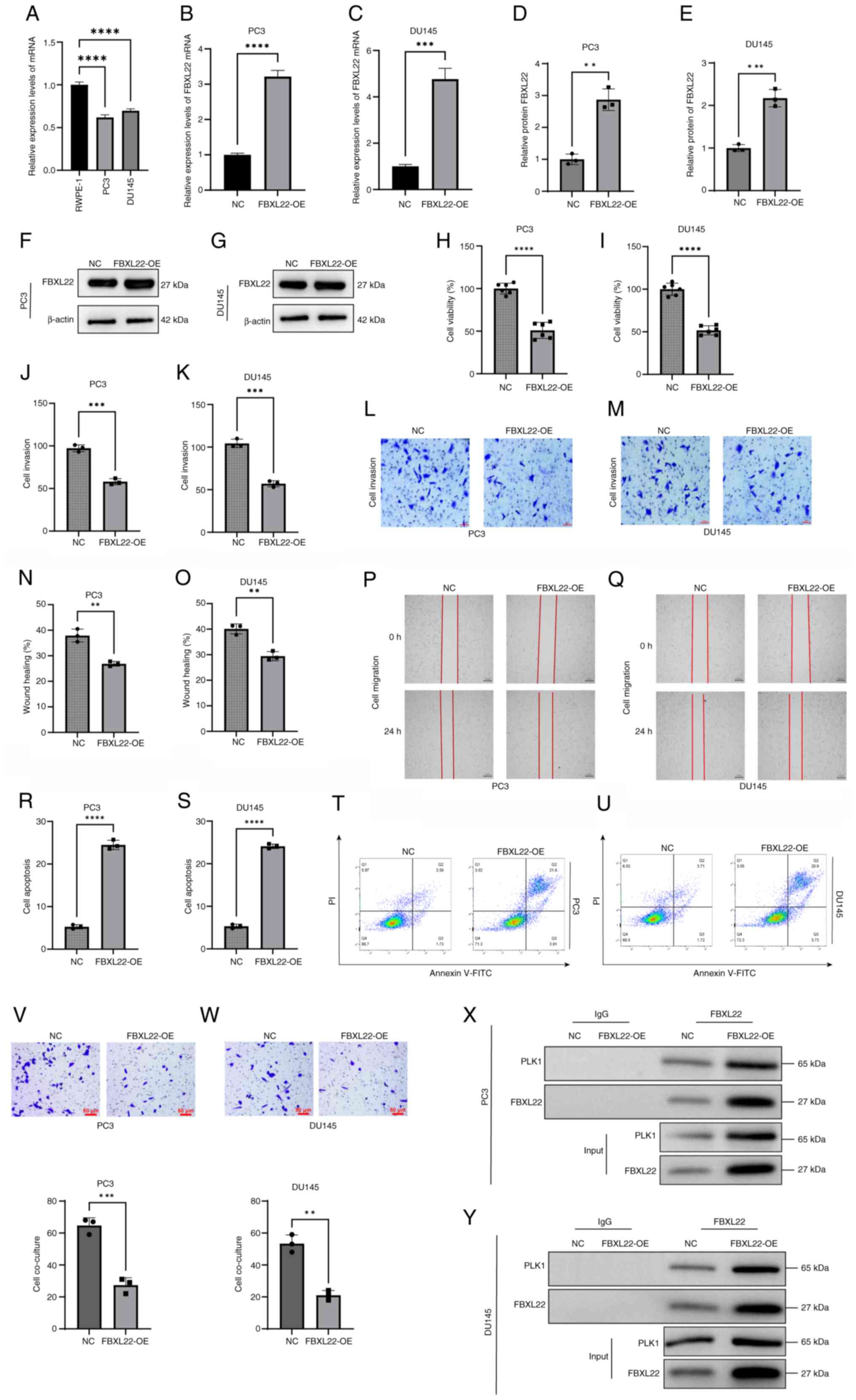

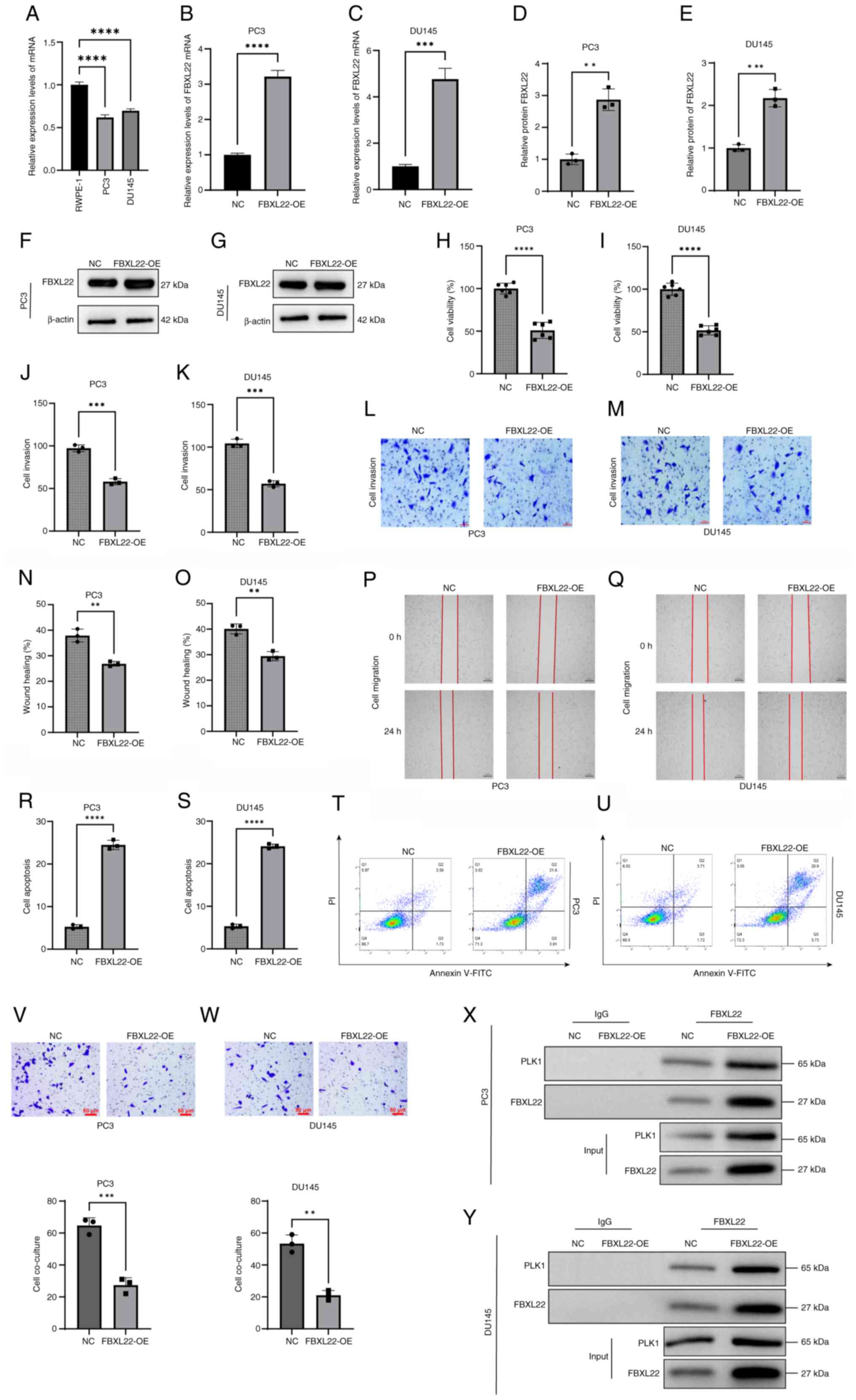

Inhibition of malignant behavior of

PCa cells by FBXL22

Analysis revealed that FBXL22 expression was

significantly decreased in PC3 and DU145 cells compared with normal

prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1; Fig.

8A). Compared with NC cells, FBXL22 overexpression markedly

increased both mRNA and protein levels of FBXL22 in PC3 and DU145

cells (Fig. 8B-G). CCK-8 assays

revealed that FBXL22 overexpression significantly reduced the cell

viability of PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig.

8H and I). Transwell assays indicated that cell invasion was

significantly decreased in FBXL22-overexpressing cells compared

with NC cells (Fig. 8J-M). Wound

healing assays demonstrated that FBXL22 overexpression

substantially inhibited cell migration (Fig. 8N-Q). Flow cytometric analysis

revealed that FBXL22 overexpression significantly increased the

apoptosis rate in PC3 and DU145 cell lines (Fig. 8R-U). Co-culture experiments with NK

cells revealed enhanced migration and cytotoxic activity of NK

cells against FBXL22-overexpressing PCa cells (Fig. 8V and W). Co-IP experiments confirmed

the interaction between FBXL22 and PLK1 (Fig. 8X and Y). Collectively, these

findings indicate that FBXL22 overexpression suppresses

proliferation, invasion and migration of PCa cells while promoting

apoptosis and enhancing immune cell activity.

| Figure 8.Effects of FBXL22 on viability,

invasion, migration and apoptosis of PCa cells. (A) The relative

expression levels of FBXL22 in normal prostate epithelial cell

lines RWPE-1 and PCa cell lines PC3 and DU145. The relative

expression levels of FBXL22 in NC and FBXL22-OE in (B) PC3 and (C)

DU145 cell lines. Semi-quantification of relative protein levels of

FBXL22 in NC and FBXL22-OE groups in (D) PC3 and (E) DU145 cells.

Western blot of FBXL22 in NC and FBXL22-OE groups in (F) PC3 and

(G) DU145 cells. Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay

in (H) PC3 and (I) DU145 cells. (J-M) The Transwell chamber was

utilized to evaluate cell invasive ability (scale bar, 50 µm).

(N-Q) Cell migratory ability was examined using a wound healing

assay (scale bar, 250 µm). The histograms demonstrate the relative

percentage of wound healing. (R) Quantification of apoptosis rates

in PC3 cells transfected with FBXL22-OE compared with the NC group,

shown as a bar graph. (S) Quantification of apoptosis rates in

DU145 cells under the same conditions. (T) Representative flow

cytometry dot plots for PC3 cells, detailing the distribution of

cells in different apoptosis stages. (U) Representative flow

cytometry dot plots for DU145 cells, using annexin V-FITC and PI

staining to delineate cell viability and apoptosis stages. NK cell

migration and cytotoxicity against FBXL22-OE (V) PC3 and (W) DU145

cells in co-culture Transwell experiments (scale bar, 50 µm).

Co-immunoprecipitation analysis confirming the interaction between

FBXL22 and PLK1 in (X) PC3 and (Y) DU145 cells. Error bars

represent standard deviation. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001; ns, P≥0.05. PCa, prostate cancer; FBXL22, F-box

and leucine rich repeat protein 22; OE, overexpression; NC,

negative control; ns, not significant; NK, natural killer. |

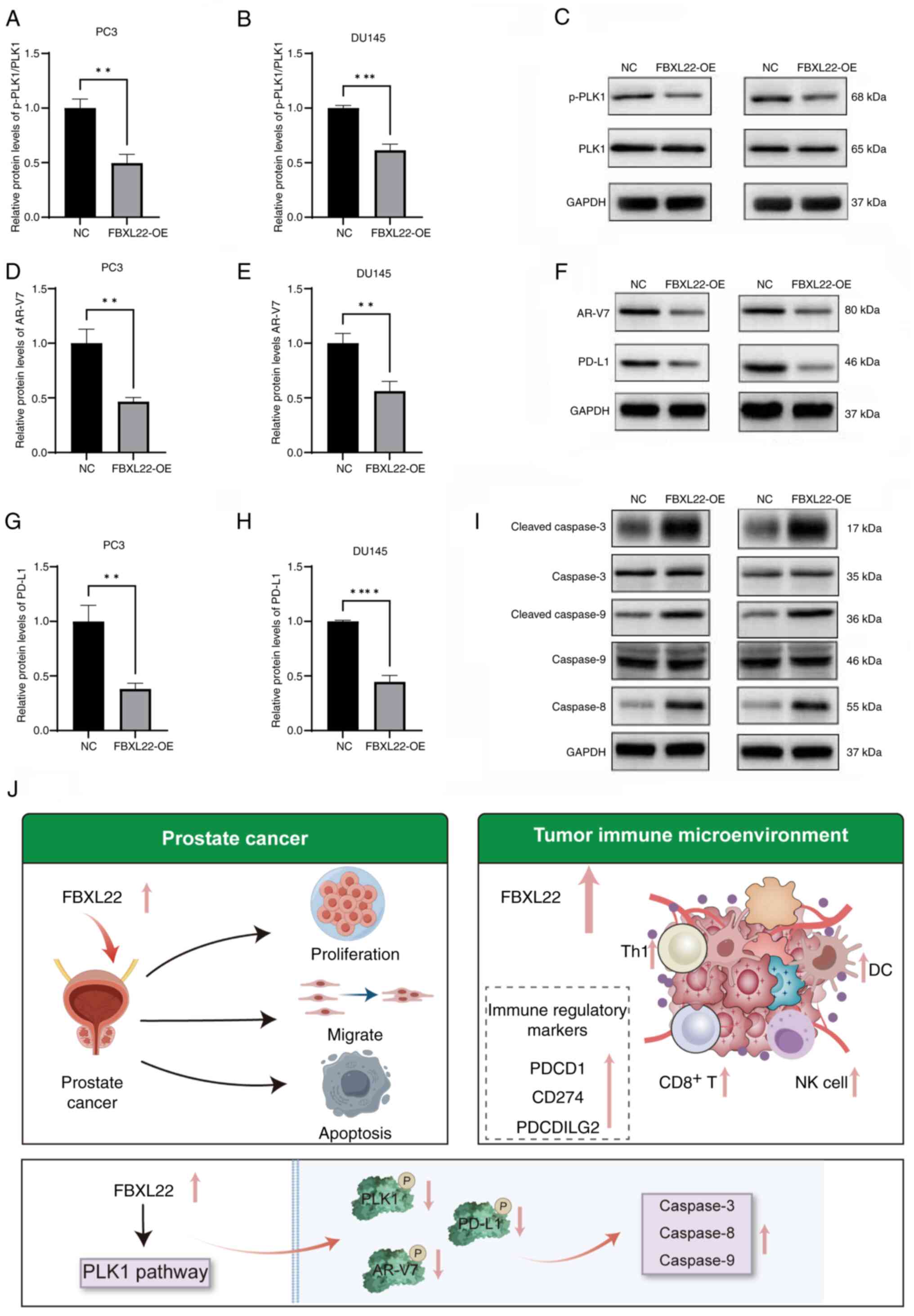

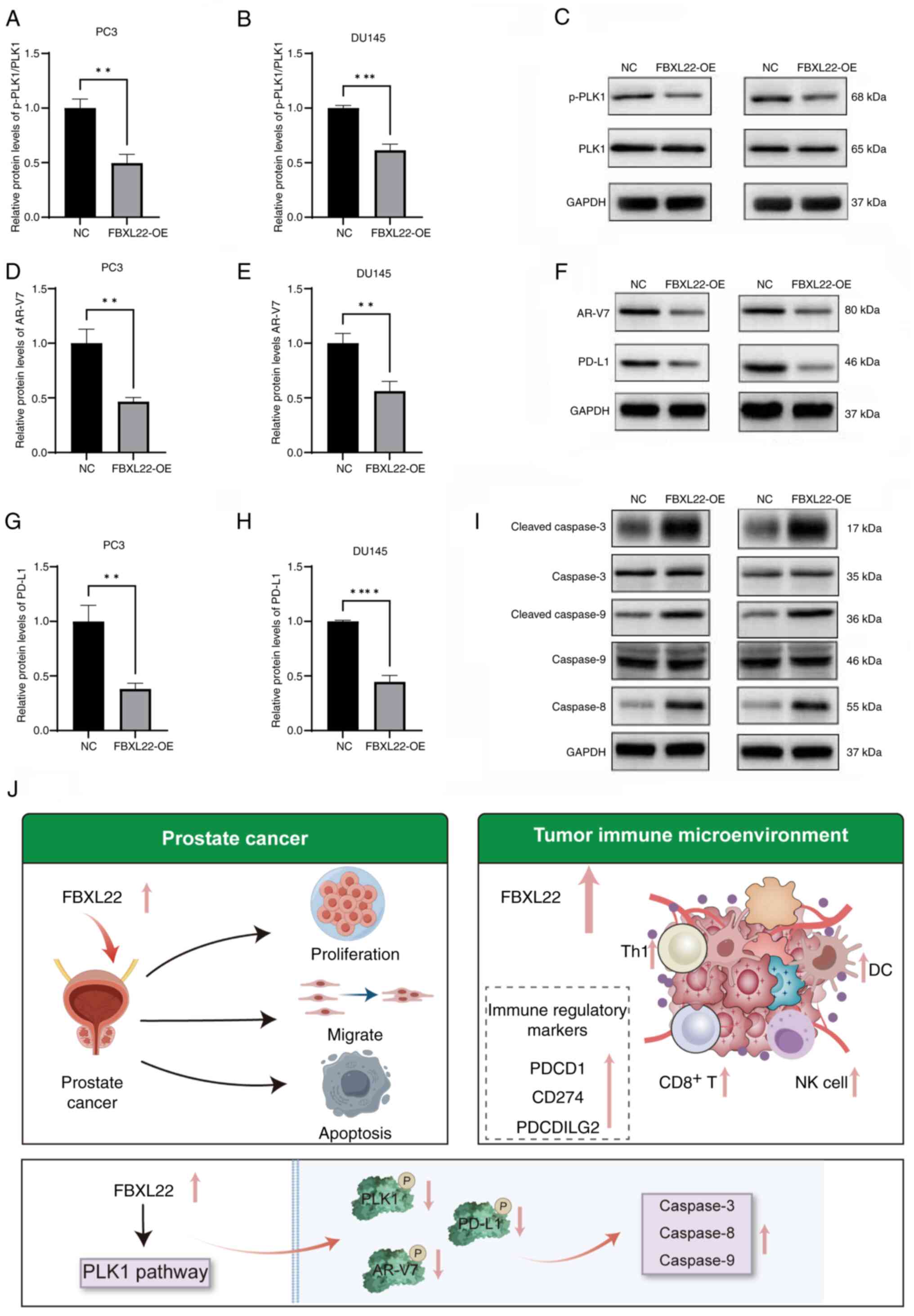

Mechanism of FBXL22 in PCa

FBXL22 upregulation resulted in reduced levels of

phosphorylated PLK1, AR-V7 and PD-L1 (P<0.01), as well as

increased levels of cleaved caspases-3, −8 and −9 (P<0.01)

(Figs. 9A-I, S10). These findings suggest that the

modulation of the PLK1 pathway may be a key mechanism by which

FBXL22 exerts tumor-suppressive effects in PCa. These results

provide a basis for the further exploration of FBXL22 as a

therapeutic target in PCa.

| Figure 9.Possible mechanism underlying the

impact of FBXL22 on PCa cell function. Western blot analysis

demonstrated the relative levels of p-PLK1 and PLK1 in (A) PC3 and

(B) DU145 cells transfected with FBXL22-OE compared with the NC

group. (C) Representative western blot images for p-PLK1, PLK1 and

GAPDH in PC3 and DU145 cells. Western blot analysis indicated the

relative levels of AR-V7 in (D) PC3 and (E) DU145 cells. (F)

Representative western blot images for AR-V7, PD-L1 and GAPDH in

PC3 and DU145 cells. Western blot analysis indicated the relative

levels of PD-L1 in (G) PC3 and (H) DU145 cells. (I) Representative

western blot images for cleaved-caspase-3, caspase-3,

cleaved-caspase-9, caspase-9, caspase-8 and GAPDH in PC3 and DU145

cells. (J) Mechanism by which FBXL22 functions in PCa cells. Error

bars represent standard deviation. The data indicates that FBXL22

overexpression reduces p-PLK1, AR-V7 and PD-L1 levels while

increasing cleaved caspase-3, −8 and −9 levels, which suggests

modulation of the PLK1 pathway and promotion of apoptosis.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. PCa, prostate

cancer; FBXL22, F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 22; OE,

overexpression; NC, negative control; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1;

AR-V7, androgen receptor splice variant 7; PD-L1, programmed

death-ligand 1; PDCD1, programmed cell death 1; PDCDILG2,

programmed cell death 1 Ligand 2. |

Discussion

The present study results demonstrated that FBXL22

upregulation suppresses cell viability, invasion and metastasis

while promoting apoptosis, potentially through the modulation of

the PLK1 pathway. Our comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of FBXL22

revealed its role as a circadian rhythm-regulated immune biomarker

with notable implications for cancer prognosis and therapy. These

findings indicate that FBXL22 is predominantly downregulated across

a multitude of cancer types and may serve as a prognostic and

diagnostic marker in specific cancer types, notably in PCa. This

downregulation was associated with poor OS in certain cancer types

such as BLCA and STAD, which highlights the potential utility of

FBXL22 as a prognostic biomarker (5–7).

Pan-cancer analysis of FBXL22 expression in the

present study revealed a complex and heterogeneous pattern.

Notably, FBXL22 was predominantly downregulated in most cancer

types compared with the corresponding normal tissues from the GTEx

database. However, significant overexpression was detected in CHOL

and LAML. This heterogeneity implies that FBXL22 may exert diverse

functions in different cancer contexts, which highlights the

importance of considering tissue-specific factors when interpreting

the role of FBXL22 in cancer. In cancer types such as BLCA and

STAD, elevated FBXL22 expression was associated with poor

prognosis, which appears to contradict its potential

tumor-suppressive role, as suggested by its low expression in other

cancer types. To reconcile this apparent discrepancy, we

hypothesized that the role of FBXL22 may be intricately associated

with the specific molecular landscape and TME of each cancer type.

For instance, in BLCA and STAD, FBXL22 overexpression might be

associated with the activation of alternative signaling pathways

that drive tumor progression, such as the PLK1 pathway, which has

been modulated by FBXL22 in PCa. In addition, tissue-specific

factors and genetic alterations can differentially influence the

function of FBXL22. In CHOL and LAML, the overexpression of FBXL22

might reflect its involvement in distinct pathophysiological

processes relevant to these cancer types. Further research is

warranted to delineate the specific mechanisms by which FBXL22

contributes to tumorigenesis in a cancer-specific manner, including

functional studies in CHOL and LAML models, as well as a more

detailed analysis of the molecular context in which FBXL22 exerts

its effects.

The present study results demonstrated a positive

correlation between high FBXL22 expression and immune checkpoint

genes such as PD-L1 and CTLA4, which suggests a potential role for

FBXL22 in immune suppression. However, high FBXL22 expression was

also associated with an improved response to immunotherapy, which

creates an apparent paradox. To address this contradiction, several

hypotheses were proposed that warrant further investigation. First,

the relationship between FBXL22 and immune checkpoint genes may be

context dependent. In some cancer types, FBXL22-induced immune

checkpoint expression may represent a feedback mechanism that

limits excessive immune activation, thereby maintaining immune

homeostasis while still permitting an overall immune-active

environment conducive to the immunotherapy response. This

hypothesis was supported by the observed co-expression patterns of

FBXL22 with both inhibitory and stimulatory immune checkpoint genes

across multiple cancer types, which suggests complex modulation of

immune responses. Second, the expression levels of immune

checkpoint genes, while correlated with FBXL22, may not solely

determine the therapeutic outcome but rather reflect a broader

immune landscape. High FBXL22 expression was also associated with

increased infiltration of antitumor immune cells, such as NK and

CD8+ T cells, which could outweigh the potential

immunosuppressive effects of checkpoint molecules, leading to

enhanced immunotherapy responses. Third, the TMB and the spectrum

of antigenic mutations present in tumors with high FBXL22

expression may enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade

therapy, even in the presence of elevated checkpoint expression.

This could be particularly relevant in cancer types in which FBXL22

expression is positively correlated with TMB, such as certain

subtypes of bladder and stomach cancer types. To fully understand

these interactions, future studies should incorporate in

vivo models to evaluate the direct impact of FBXL22 on immune

cell function within the TME and investigate how FBXL22 modulates

the balance between immune activation and suppression.

Additionally, analyzing the correlation among FBXL22 expression,

immune checkpoint usage and clinical outcomes across diverse cancer

types and immunotherapy regimens could provide further insights

into the role of FBXL22 as a biomarker of treatment response.

The mechanisms underlying the role of FBXL22 in

cancer appear to be multifaceted and involve circadian rhythm

regulation, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, focal adhesion

signaling and cGMP-PKG signaling (18). The present analysis also revealed

strong correlations between FBXL22 expression and immune checkpoint

genes, which suggests their involvement in the TME (19). This is further supported by the

observation that FBXL22 expression is associated with the

infiltration of CAFs and ECs, which may affect immunotherapy

outcomes (20,21).

In PCa, the present study provided evidence that

FBXL22 upregulation suppresses cell viability, invasion and

metastasis while promoting apoptosis, potentially by modulating the

PLK1 pathway (22). This suggests

that FBXL22 is a promising target for therapeutic interventions in

PCa.

The additional experiments further elucidate the

role of FBXL22 in PCa and the TME. The co-culture experiments with

NK cells provide evidence that FBXL22 overexpression enhances

immune cell activity, reinforcing its potential as an

immunomodulatory hub. This is supported by the observed increase in

NK cell migration and cytotoxicity, which suggests that FBXL22 may

promote antitumor immune responses by modulating the TME.

Furthermore, the Co-IP validation of the FBXL22-PLK1 interaction

strengthens the mechanistic basis for the tumor-suppressive effects

of FBXL22, likely mediated through PLK1 pathway modulation. These

findings collectively enhance current understanding of the dual

role of FBXL22 in regulating cancer cell behavior and immune cell

function, which underscores its therapeutic potential in PCa.

The correlation between FBXL22 expression and TMB,

microsatellite instability (MSI) and HRD across various cancer

types further underscores its potential as a predictive biomarker

of therapeutic response (23). The

findings of the present study indicate that FBXL22 can serve as a

biomarker to guide individualized cancer treatment decisions,

particularly in the context of immunotherapy and targeted therapies

(24).

TME, a complex network of cells and molecules that

surrounds a tumor, serves a key role in tumor biology (25). Based on TCGA data, the present

analysis suggested that FBXL22 was positively correlated with the

presence of CAFs and ECs in tumors (26). This correlation, along with the

notable associations between FBXL22 expression and genes associated

with immune checkpoint pathways and immunomodulation across

multiple cancer types, suggests that FBXL22 may function as an

oncogene involved in regulating the TME to promote an active state

or inflammatory response conducive to a robust response to immune

checkpoint inhibitor drugs (27).

Enrichment analysis integrating information about

FBXL22-binding protein genes and FBXL22 expression-related genes

across all tumor types revealed associations with processes such as

Skp1-Cullin-F-box-dependent, proteasomal, ubiquitin-dependent,

protein catabolic processes and muscle contraction (28). KEGG analysis suggested that the

pan-cancer role of FBXL22 may involve pathways, such as the

circadian rhythm, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, cGMP-PKG

signaling pathway and focal adhesion, which are closely associated

with tumor occurrence and development (29).

Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, the present

study provided the first comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of the

circadian rhythm gene FBXL22 and revealed its close association

with clinical prognosis, DNA methylation, immune regulation, immune

cell infiltration, TMB and MSI. The findings of the present study

suggest that FBXL22 is a promising novel marker of cancer

recurrence risk and immuno-infiltration in various tumor types,

particularly in PCa. These results contribute to current

understanding of the potential role and molecular mechanisms of

FBXL22 in tumor development and the TME based on clinical tumor

samples (30). Further research is

warranted to explore the mechanisms by which FBXL22 affects the

development and immune microenvironment of PCa and to validate its

potential as a therapeutic target.

In conclusion, the pan-cancer analysis of the

circadian rhythm gene FBXL22 revealed close associations between

its expression and clinical prognosis, DNA methylation, immune

regulation, immune cell infiltration, TMB and MSI. Furthermore,

preliminary investigations were performed into the mechanisms

underlying the potential ability of FBXL22 to inhibit PCa and

enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. The aforementioned

comprehensive multi-omics analysis demonstrated that FBXL22 has

notable potential as a novel marker for cancer recurrence risk and

immuno-infiltration in various tumor types, particularly PCa. These

results contribute to current understanding of the potential role

and molecular mechanisms of FBXL22 in tumor development and TIM,

based on clinical tumor samples.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Hebei Province Medical

Science Research Program (grant no. 20240298) and Finance

Department of Hebei Province Government-Sponsored Program for

Cultivating Outstanding Clinical Medical Talents (grant no.

ZF2025162).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL, WL and YS supervised the project and designed

the present study. JL, MF and JZ performed the data analysis and

prepared all the figures and tables. MF, SY and JZ performed the

experiments. JL and SY drafted the manuscript. WL and YS revised

the manuscript. JL obtained funding for the study. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. JL and WL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BLCA

|

bladder urothelial carcinoma

|

|

BRCA

|

breast invasive carcinoma

|

|

CHOL

|

cholangiocarcinoma

|

|

COAD

|

colon adenocarcinoma

|

|

HRD

|

homologous recombination

deficiency

|

|

LAML

|

acute myeloid leukemia

|

|

LIHC

|

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

PAAD

|

pancreatic adenocarcinoma

|

|

PRAD

|

prostate adenocarcinoma

|

|

READ

|

rectum adenocarcinoma

|

|

STAD

|

stomach adenocarcinoma

|

|

THCA

|

thyroid carcinoma

|

|

TMB

|

tumor mutation burden

|

|

UCEC

|

uterine corpus endometrial

carcinoma

|

|

UVM

|

uveal melanoma

|

References

|

1

|

Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, Metcalfe

C, Young GJ, Walsh EI, Lane JA, Noble S, Oliver SE, Evans S, et al:

Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on

prostate cancer mortality: The CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

319:883–895. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xuan W, Khan F, James CD, Heimberger AB,

Lesniak MS and Chen P: Circadian regulation of cancer cell and

tumor microenvironment crosstalk. Trends Cell Biol. 31:940–950.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhu X, Maier G and Panda S: Learning from

circadian rhythm to transform cancer prevention, prognosis, and

survivorship care. Trends Cancer. 10:196–207. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang C, Barnoud C, Cenerenti M, Sun M,

Caffa I, Kizil B, Bill R, Liu Y, Pick R, Garnier L, et al:

Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses.

Nature. 614:136–143. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jiang M, Jia K, Wang L, Li W, Chen B, Liu

Y, Wang H, Zhao S, He Y and Zhou C: Alterations of DNA damage

response pathway: Biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer

immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:2983–2994. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shang S, Liu J, Verma V, Wu M, Welsh J, Yu

J and Chen D: Combined treatment of non-small cell lung cancer

using radiotherapy and immunotherapy: Challenges and updates.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 41:1086–1099. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Spaich S, Will RD, Just S, Spaich S, Kuhn

C, Frank D, Berger IM, Wiemann S, Korn B, Koegl M, et al: F-box and

leucine-rich repeat protein 22 is a cardiac-enriched F-box protein

that regulates sarcomeric protein turnover and is essential for

maintenance of contractile function in vivo. Circ Res.

111:1504–1516. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hughes DC, Baehr LM, Driscoll JR, Lynch

SA, Waddell DS and Bodine SC: Identification and characterization

of Fbxl22, a novel skeletal muscle atrophy-promoting E3 ubiquitin

ligase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 319:C700–C719. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Beisaw A, Kuenne C, Guenther S, Dallmann

J, Wu CC, Bentsen M, Looso M and Stainier DYR: AP-1 contributes to

chromatin accessibility to promote sarcomere disassembly and

cardiomyocyte protrusion during zebrafish heart regeneration. Circ

Res. 126:1760–1778. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Haddad SA, Ruiz-Narváez EA, Haiman CA,

Sucheston-Campbell LE, Bensen JT, Zhu Q, Liu S, Yao S, Bandera EV,

Rosenberg L, et al: An exome-wide analysis of low frequency and

rare variants in relation to risk of breast cancer in African

American Women: the AMBER Consortium. Carcinogenesis. 37:870–877.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tekcham DS, Chen D, Liu Y, Ling T, Zhang

Y, Chen H, Wang W, Otkur W, Qi H, Xia T, et al: F-box proteins and

cancer: An update from functional and regulatory mechanism to

therapeutic clinical prospects. Theranostics. 10:4150–4167. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu J, Tan Z, Yang S, Song X and Li W: A

circadian rhythm-related gene signature for predicting relapse risk

and immunotherapeutic effect in prostate adenocarcinoma. Aging

(Albany NY). 14:7170–7185. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2:1001412021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, Poisson

LM, Lazar AJ, Cherniack AD, Kovatich AJ, Benz CC, Levine DA, Lee

AV, et al: An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to

drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell.

173:400–16.e11. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ukimura O, Coleman JA, de la Taille A,

Emberton M, Epstein JI, Freedland SJ, Giannarini G, Kibel AS,

Montironi R, Ploussard G, et al: Contemporary role of systematic

prostate biopsies: Indications, techniques, and implications for

patient care. Eur Urol. 63:214–230. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nguyen L, J WMM, Van Hoeck A and Cuppen E:

Pan-cancer landscape of homologous recombination deficiency. Nat

Commun. 11:55842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gonzalez D and Stenzinger A: Homologous

recombination repair deficiency (HRD): From biology to clinical

exploitation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 60:299–302. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, Luber B,

Nakazawa M, Roeser JC, Chen Y, Mohammad TA, Chen Y, Fedor HL, et

al: AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 371:1028–1038. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zheng Z, Li J, Liu Y, Shi Z, Xuan Z, Yang

K, Xu C, Bai Y, Fu M, Xiao Q, et al: The crucial role of AR-V7 in

enzalutamide-resistance of castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Cancers. 14:48772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

You S, Knudsen BS, Erho N, Alshalalfa M,

Takhar M, Al-Deen Ashab H, Davicioni E, Karnes RJ, Klein EA, Den

RB, et al: Integrated classification of prostate cancer reveals a

novel luminal subtype with poor outcome. Cancer Res. 76:4948–4958.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, Yu M, Lehrer J,

Alshalalfa M, Speers C, Cooperberg MR, Kim W, Ryan CJ, et al:

Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with

prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol.

3:1663–1672. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Myers JA and Miller JS: Exploring the NK

cell platform for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

18:85–100. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang Y, Xiang Y, Xin VW, Wang XW, Peng XC,

Liu XQ, Wang D, Li N, Cheng JT, Lyv YN, et al: Dendritic cell

biology and its role in tumor immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Dhanasekaran R, Deutzmann A,

Mahauad-Fernandez WD, Hansen AS, Gouw AM and Felsher DW: The MYC

oncogene- the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune

evasion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:23–36. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Qiu X, Boufaied N, Hallal T, Feit A, de

Polo A, Luoma AM, Alahmadi W, Larocque J, Zadra G, Xie Y, et al:

MYC drives aggressive prostate cancer by disrupting transcriptional

pause release at androgen receptor targets. Nat Commun.

13:25592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Arriaga JM, Panja S, Alshalalfa M, Zhao J,

Zou M, Giacobbe A, Madubata CJ, Kim JY, Rodriguez A, Coleman I, et

al: A MYC and RAS co-activation signature in localized prostate

cancer drives bone metastasis and castration resistance. Nat

Cancer. 1:1082–1096. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Faskhoudi MA, Molaei P, Sadrkhanloo M,

Orouei S, Hashemi M, Bokaie S, Rashidi M, Entezari M, Zarrabi A,

Hushmandi K, et al: Molecular landscape of c-Myc signaling in

prostate cancer: A roadmap to clinical translation. Pathol Res

Pract. 233:1538512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Han Z, Mo R, Cai S, Feng Y, Tang Z, Ye J,

Liu R, Cai Z, Zhu X, Deng Y, et al: Differential expression of E2F

transcription factors and their functional and prognostic roles in

human prostate cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8313292022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|