Introduction

Kidney cancer remains one of the most prevalent and

deadliest tumors in urological oncology, with ~155,702 mortalities

and 434,419 new cases recorded worldwide in 2022 (1). Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC)

accounts for >70% of all kidney cancer cases and is the most

common subtype (2). ccRCC typically

exhibits aggressive growth, frequent metastasis and substantial

immune infiltration, with ~30% of patients experiencing recurrence

after total nephrectomy (3,4). Conventional radiation therapy and

chemotherapy have demonstrated limited efficacy in the treatment of

all renal cell carcinoma subtypes (5). Immunotherapy and targeted therapy have

shown considerable potential in patients with ccRCC. However, owing

to low response rates, immunotherapy may not be suitable for all

individuals (6). In addition,

patients receiving targeted therapy are prone to resistance,

limiting the efficacy of existing treatments and complicating ccRCC

control (7). The outcomes of

patients with ccRCC are primarily affected by drug resistance and

metastasis (8). Therefore, to

effectively treat metastatic ccRCC, it is clinically important to

identify the most preferable biomarkers and immune-related

therapeutic targets.

Human guanylate-binding protein 5 (GBP5), which

belongs to the guanylate-binding protein (GBP) family, is

classified under the dynamin superfamily of large GTPases that are

induced by interferons (9,10). It is regarded as a key regulator of

immune responses in neoplastic diseases (9). Studies have shown that GBP5 exerts

antiviral activity and influences innate immunity and inflammation

(11,12). Due to the notable functions of other

members of the GBP family in proliferation and invasion, GBP5 may

also serve a major role in malignancy (13). Previous studies have supported the

key role of GBP5 in cancer progression. In gastric adenocarcinomas,

GBP5 expression is markedly upregulated, contributing to cancer

development through the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)-STAT1/GBP5/C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) signaling circuit (14,15).

In addition, GBP5 enhances the migration, invasion and

proliferation of glioblastoma cells, promoting glioblastoma

progression through the proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase

Src/ERK1/2/MMP3 pathway (16).

Furthermore, in triple-negative breast cancer cells exhibiting high

GBP5 expression, GBP5 knockdown notably reduces the number of

migrating cells, the activity of the IFN-γ/STAT1 and TNF-α/NF-κB

signaling axes and the expression of programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) (17).

Previous reports have outlined the relevance of GBP5

in tumor immunity. Several studies have indicated that GBP5

expression is associated with the extent of immune cell

infiltration in breast cancer (17), melanoma (18), colon cancer (19), ovarian cancer (20), hepatocellular cancer (21) and small-cell lung cancer (22), emphasizing the role of GBP5 in

shaping the tumor immune microenvironment (TME). In oral squamous

cell carcinoma, GBP5 serves as an immune-related biomarker that

induces NF-κB activation and facilitates radioresistance, PD-L1

upregulation and tumor metastasis (23). In hepatocellular carcinoma and

ovarian cancer, GBP5 not only activates the PI3K-AKT signaling

pathway but also modulates tumor metabolism and immune evasion

through the regulation of DNA methylation and micro-RNA networks

(24,25). Furthermore, in cutaneous melanoma

and ovarian cancer, GBP5 induces pyroptosis through the

JAK2-STAT1-caspase-1 axis, therefore influencing cell death and

immune responses. Overall, GBP5 modulates the immune

microenvironment which further influences the prognosis of diverse

tumor types (20,26). In ccRCC, immune-suppressive cells,

such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells,

induce immune dysfunction, leading to poor therapeutic outcomes

(27). However, the precise

function of GBP5 is still not fully understood in ccRCC.

The present study employed R software together with

a variety of bioinformatics tools to integrate and analyze data,

aiming to comprehensively investigate the role of GBP5 in ccRCC.

Specifically, its differential expression patterns, associations

with clinicopathological features, prognostic and diagnostic

significance, protein-protein interaction networks, biological

functions, and potential involvement in tumor immune cell

infiltration were examined. Furthermore, in vitro cellular

experiments were performed to validate and further explore the

impact of GBP5 on the biological behavior of ccRCC. To the best of

our knowledge, the results of the present study demonstrate the

biological function and clinical significance of GBP5 and its

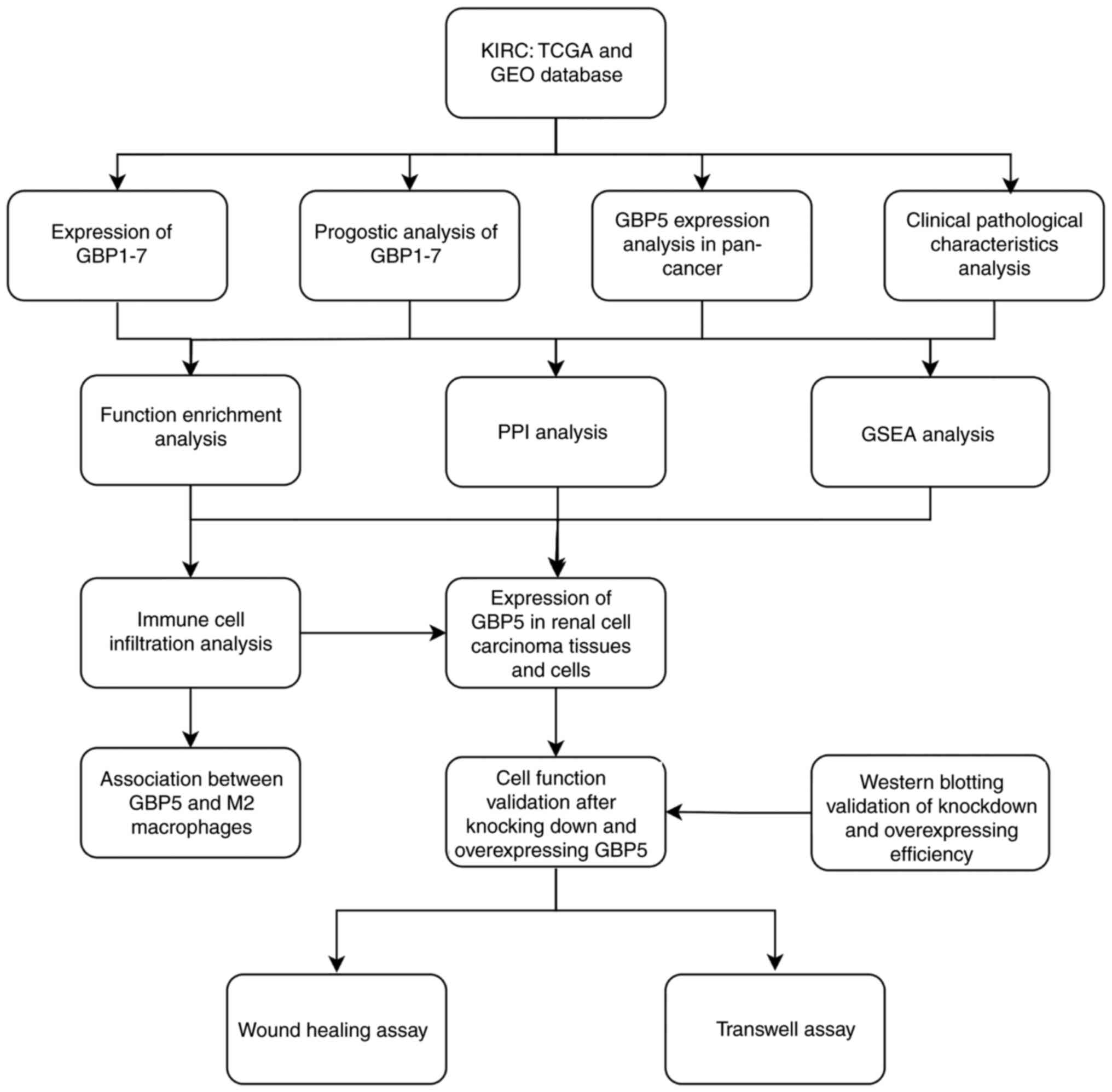

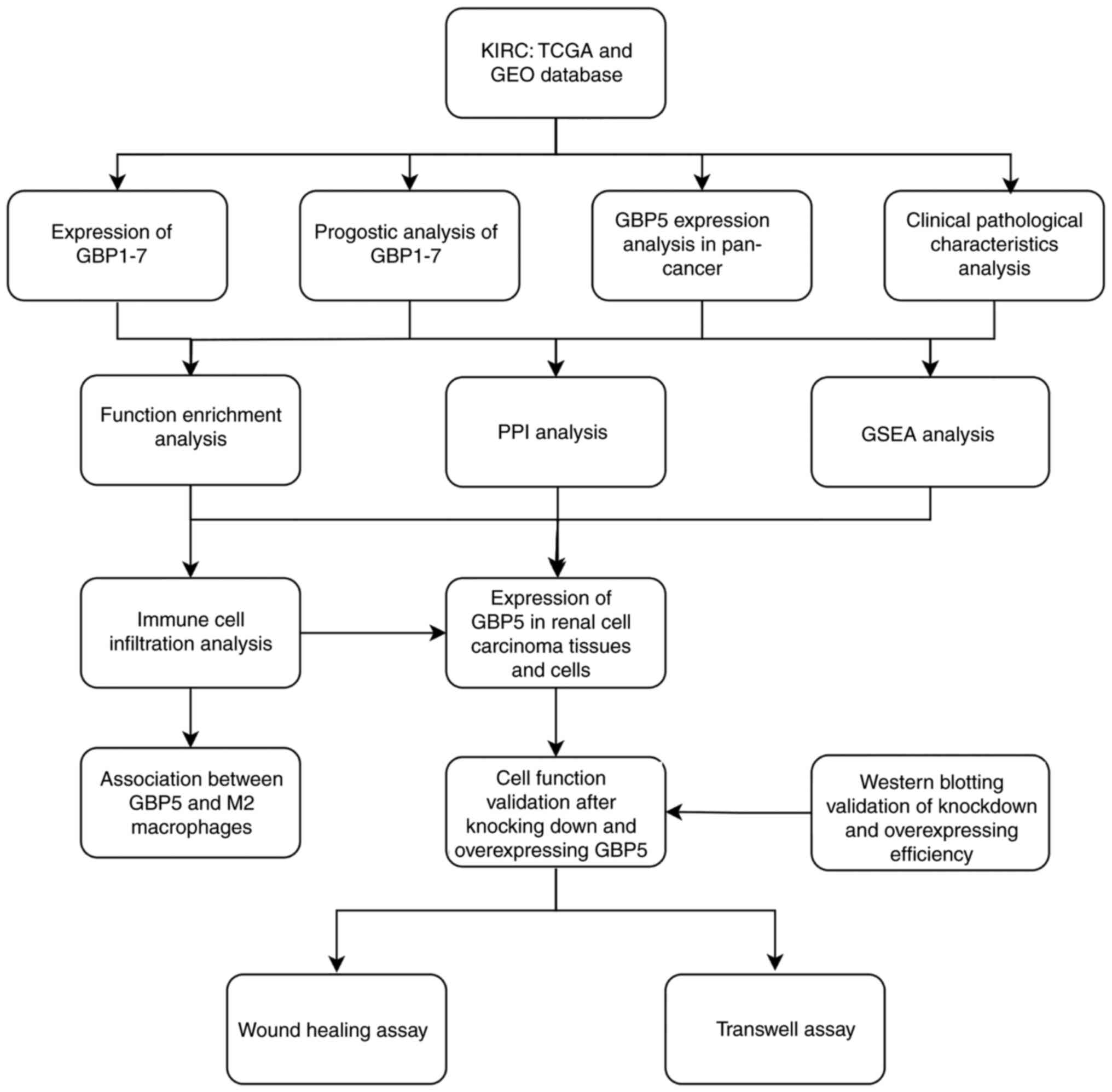

influence on tumor immunity in ccRCC for the first time. Fig. 1 illustrates the study design and

workflow, highlighting the step-by-step process from data

acquisition to experimental validation. The present study provides

novel insights into the function of GBP5 in ccRCC, potentially

offering new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the diagnosis

and treatment of ccRCC.

| Figure 1.Overall workflow of the study.

Schematic representation of the major steps and analytical methods

employed, offering a concise and visual summary of the entire

research process. KIRC datasets from TCGA and GEO databases were

utilized to perform differential gene expression and prognostic

analyses of GBP1-7 genes, with a focus on the clinical pathological

characteristics of GBP5 in ccRCC, as well as the gene function

enrichment analysis, PPI network analysis, GSEA analysis and immune

cell infiltration analysis conducted. Finally, wound-healing and

Transwell assays were conducted to evaluate the role of GBP5 in the

invasion and migration of ccRCC cells. KIRC, kidney renal clear

cell carcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene Expression

Omnibus; GBP, guanylate-binding protein; PPI, protein-protein

interaction; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; ccRCC, clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. |

Materials and methods

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis 2 (GEPIA2)

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) analyzes gene expression

differences based on tumor samples and normal samples from both The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and the Genotype-Tissue

Expression (https://www.gtexportal.org) databases (28). In the present study, this tool

facilitated the comparison of GBP5 expression between renal tumor

tissue and adjacent normal tissue.

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset

selection

From the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), two datasets were

acquired. GSE53757 (29) included

GBP1-6 mRNA data from 72 ccRCC and 72 normal tissues. GSE36895

(30) provided GBP1-6 mRNA data

from 23 ccRCC samples and 23 normal tissues. Analysis of GBP1-6

mRNA levels was conducted using these two datasets.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) plotter

As an online tool, the KM plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis) provided survival

analysis capabilities for 21 tumor types by associating gene

expression profiles with clinical prognosis (31). Using this resource, the KIRC dataset

was selected in the pan-cancer module, and the ‘auto select best

cutoff’ option was applied for patient grouping to evaluate the

overall survival of GBP1-7.

GeneMANIA database analysis

GeneMANIA (http://www.genemania.org) is a publicly accessible

tool for analyzing genetic and protein interactions, co-expression,

pathways and gene co-localization (32). The potential interactions of GBP5

with related genes were assessed using this platform.

TIMER database analysis

TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) is based on six

algorithms used to evaluate immune infiltration levels (33). The impact of GBP5 expression on

immune cell infiltration in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

(KIRC) was analyzed in the present study. TIMER2.0 (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/) was also

employed to investigate GBP5 expression differences between tumor

tissue and adjacent tissue, alongside its association with immune

cell gene markers in KIRC (34).

Tumor Immune Single-cell Hub 2

(TISCH2) database analysis

Based on single-cell RNA sequencing, the TISCH2

database (http://tisch.comp-genomics.org/) is designed to

analyze the TME at single-cell resolution (35). The distribution and expression

patterns of GBP5 in the TME were analyzed using the GSE111360

(36) and GSE121636 (37) datasets.

Bioinformatics analysis

TCGA-KIRC RNA-sequencing data were downloaded from

TCGA database. Transcript per million format expression data and

the corresponding clinical information were extracted. Boxplots

illustrating GBP5 expression across different clinicopathological

features, including tumor-lymph node-metastasis (TNM) stages, were

generated using the ‘ggplot2 v3.3.5’ R package (RStudio, Inc.).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to

assess the diagnostic value of GBP5 in ccRCC. Based on the criteria

of log2 fold change ≥2 and the adjusted P-value of

<0.05, GBP5-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were

identified and visualized through a volcano plot plotted using the

aforementioned ‘ggplot2’ R package. Gene Ontology (GO) biological

process enrichment analysis was performed using the DAVID database

(https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted to explore the

relevant molecular signaling pathways. Data from the Tracking Tumor

Immunophenotype (TIP) database (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/TIP) were used for immune

cell infiltration analysis (38).

The relationship between GBP5 expression and immune cell

infiltration and circulation was assessed using Spearman's rank

correlation analysis.

Clinical samples

A total of eleven pairs of clinical specimens were

obtained from the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital

(Shenzhen, P.R. China) between August 2024 and November 2024.

Patients were eligible if no radiotherapy or chemotherapy had been

administered prior to biopsy, the pathological diagnosis confirmed

ccRCC and no other malignant tumors were present. The Ethics

Committee of the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital approved

the collection of renal carcinoma tumor tissues and adjacent normal

tissues (approval no. 2024256), ensuring that all procedures

complied with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of

Helsinki. All the donors signed an informed consent form.

Cell culture

Human ACHN, Caki-1, 786-O and human proximal tubular

epithelial (HK-2) cell lines were procured from Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. RPMI 1640 complete medium

(Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to

culture the 786-O and ACHN cells. For Caki-1 cells, McCoy's 5A

complete medium (Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

was used. For HK-2 cells, Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was utilized. A 10% fetal bovine

serum solution (FBS; Procell Life Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) and 1% antibiotics solution (100 µg/ml streptomycin and 100

U/ml penicillin) were added to prepare the complete medium.

Cultures were placed at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator,

Mycoplasma contamination was checked in all cell lines and

short tandem repeats analysis was used for authentication.

Transfection of lentivirus

Lentivirus overexpression, GBP5 overexpression (GBP5

OE; 47597-2; order of vector elements:

Ubi-MCS-3FLAG-SV40-puromycin), vector controls (CON254), GBP5 short

hairpin RNA (shRNA; order of vector elements:

hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin) and negative control shRNAs

(shNC) were produced by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The target

sequences of the shRNAs were as follows: shNC (CON313),

5′-TTCTCCGAACGTCACGT-3′; the GBP5-specific shRNA shGBP5#1

(103584–1), 5′-CTGGAAATAGATGGGCAACTT-3′ and the GBP5-specific shRNA

shGBP5#2 (103585–1), 5′-TGCCTCATCGAGAACTTTAAT-3′. Caki-1 and 786-O

cells were transfected according to manufacturer's instructions.

Cells infected with lentivirus were treated with puromycin (2

µg/ml) for 7 days, followed by evaluation of target gene knockdown

and overexpression efficiency using western blot analysis. The

stable cell lines obtained after successful selection and

maintained within 50 passages were used for subsequent

experiments.

Western blotting

Tissue and cellular protein lysates were prepared

using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with protease and

phosphatase inhibitors (cat. no. P1048, Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Protein concentrations were determined using the

bicinchoninic acid method (cat. no. P0012; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The proteins were resolved using 8–10% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the proteins

(10–50 µg) were then transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes

(cat. no. 66485; Pall Life Sciences). The membranes were blocked

with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at 20–25°C, after which the membranes

were incubated at 4°C for 8–12 h with primary antibodies against

CD163 (1:1,000; cat. no. R381830; Chengdu Zen-BioScience Co.,

Ltd.), GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. D110016-0100; Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. D110022-0100; Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), Flag (1:5,000; cat. no. 20543-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

and GBP5 (1:2,000; cat. no. 13220-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.).

The membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies [horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:5,000; cat. no.

511203; Chengdu Zen-BioScience Co., Ltd.] and HRP-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. 511103; Chengdu Zen-BioScience

Co., Ltd.) at 20–25°C for 2 h. Protein signals were detected using

the ChemiDoc™ MP enhanced chemiluminescence system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and quantified using the ImageJ

software (version 1.40 g; National Institutes of Health).

Wound healing assay

786-O and Caki-1 cells were seeded in 12-well plates

and cultured until they reached full confluence. A 1,000 µl pipette

tip was used to create a linear scratch in the cell monolayer. The

wells were rinsed twice with PBS to remove detached cells and the

adherent cells were maintained in a medium containing 1% FBS.

Images of the wound area were captured at 0, 10, 12, 24 and 36 h

using time-lapse imaging under a light microscope (magnification,

×4).

Transwell assay

Transwell assay was performed to assess the

migratory potential of ccRCC cells. Cell migration was evaluated

using uncoated Transwell chambers (cat. no. 14341, 8 µm pore size;

LABSELECT®; Lanjieke Technology Co., Ltd.) and cell

invasion was assessed using Matrigel-coated inserts (Corning, Inc.)

pre-incubated at 37°C for 30 min. A total of 3×104 786-O

and Caki-1 cells were seeded into the upper chambers of 24-well

plates containing serum-free medium. Culture medium supplemented

with 15% FBS was added to the lower chambers, making up 500 µl as a

chemoattractant. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h for the invasion

assay and 12 h for the migration assay, the cells that had moved to

the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at 20–25°C for 30 min, followed by crystal violet

staining at 20–25°C for 10 min. Following staining, the cells were

imaged using a light microscope (magnification, ×10) and cell

counts were performed in three or more randomly selected fields of

view.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 7.0; GraphPad; Dotmatics)

was used for statistical analyses. Each experiment was performed in

triplicate. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard

deviation. Both unpaired and paired two-tailed Student's t-tests

were used for comparisons between groups. For comparisons involving

multiple groups, Tukey's post hoc test was applied after one-way

ANOVA. Spearman's or Pearson's correlation coefficients were

determined, depending on suitability, to perform correlation

analyses. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Additionally, the following criteria

indicated statistical significance: *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001.

Results

Role of GBP expression and its

prognostic significance in ccRCC

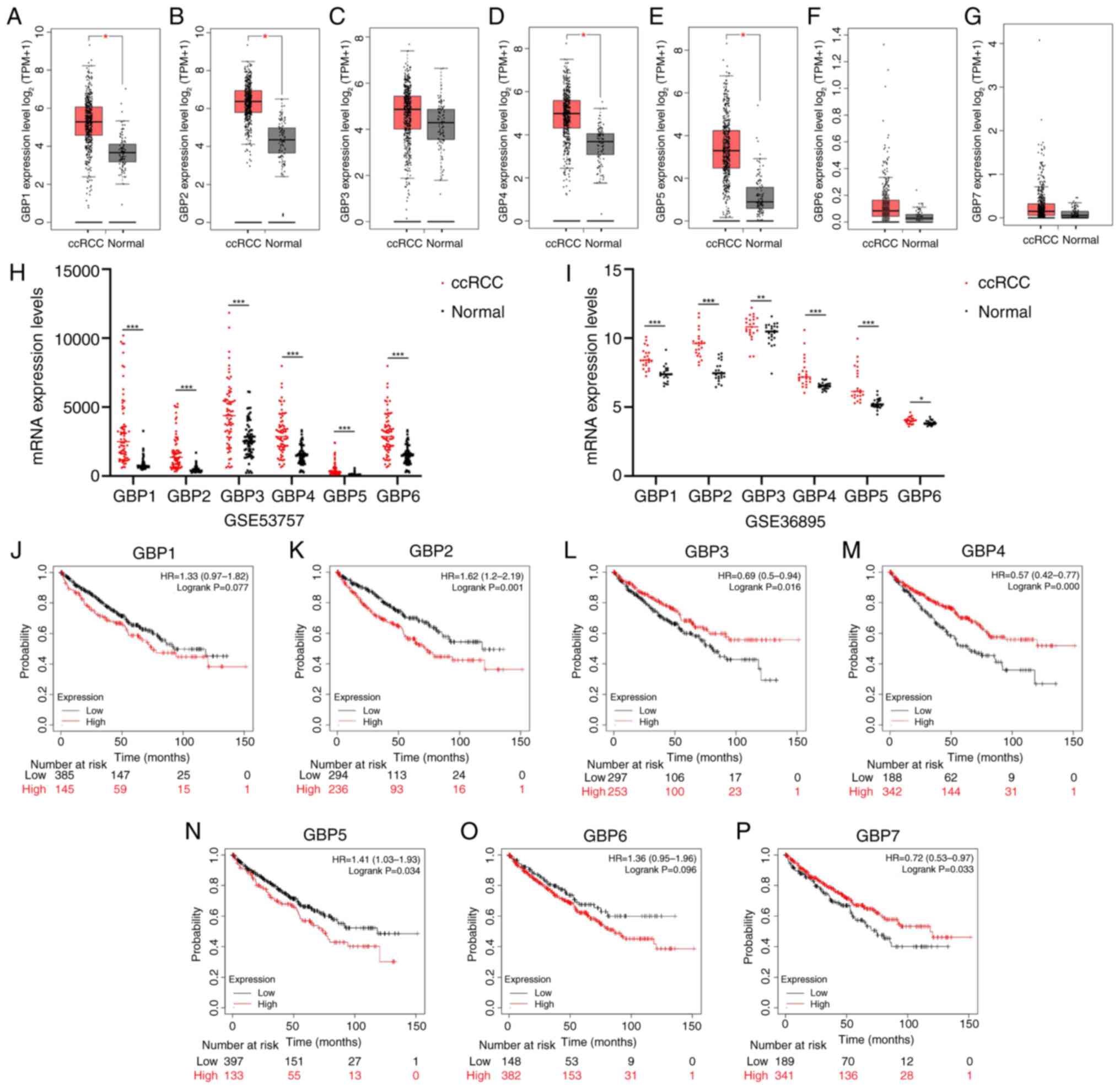

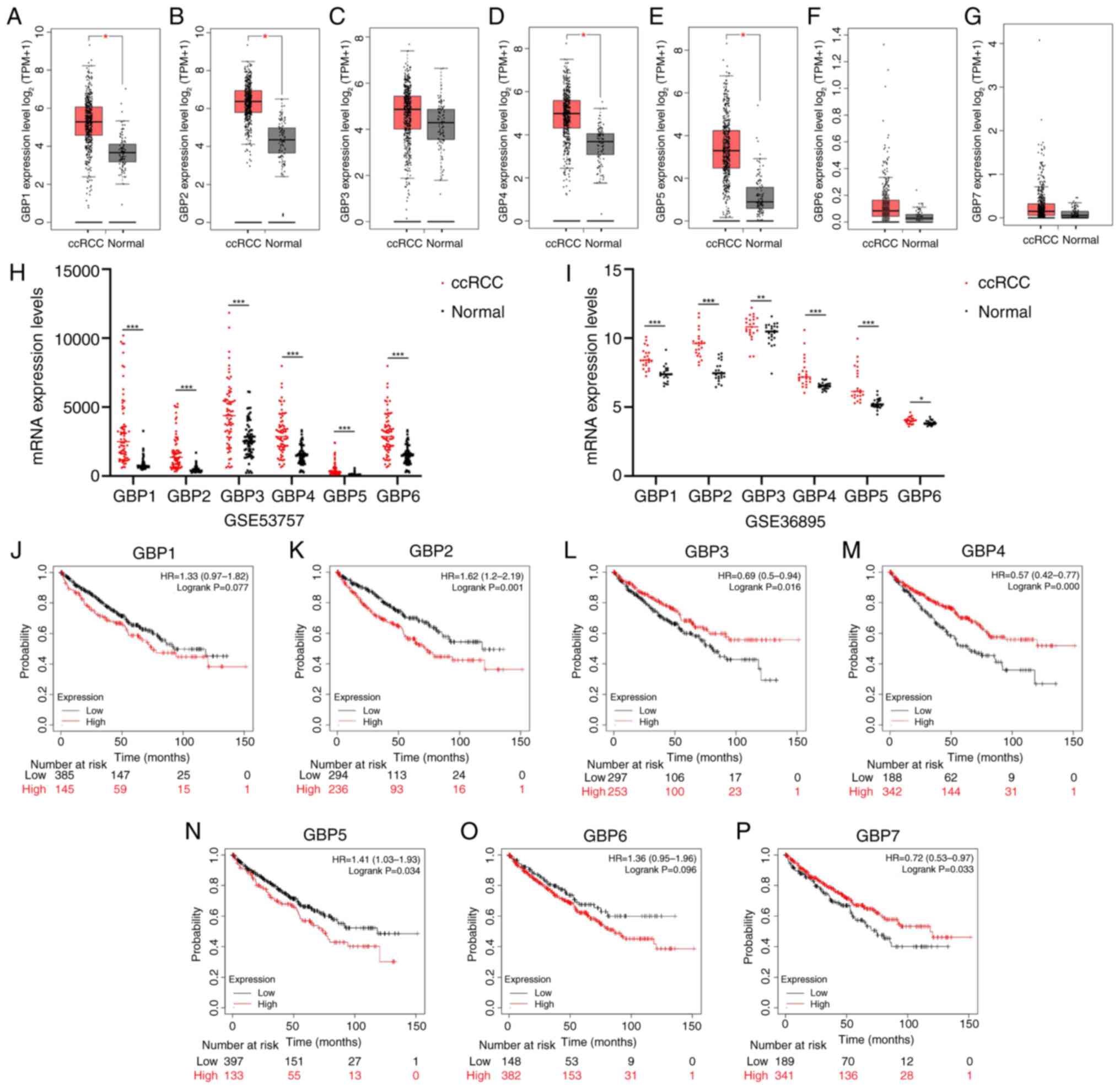

Research suggests that the GBP gene family members

regulate the biological behavior of various cancers, indicating

their role in cancer initiation and progression (12). Therefore, the GEPIA2.0 tool was

initially applied to assess the expression of the GBP family

members in ccRCC. Results revealed that GBP1-7 exhibited a

consistent expression pattern, characterized by upregulation in

tumor tissues (Fig. 2A-G). Notably,

the upregulation of GBP1, GBP2 (39), GBP4 and GBP5 was statistically

significant. This observation was consistent with the results of

the analysis of ccRCC datasets from the GEO database, further

reinforcing their validity (Fig. 2H and

I). Furthermore, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis results

indicated that elevated levels of GBP2 (39) and GBP5 were associated with a poor

prognosis, whereas low expression of GBP3, GBP4 and GBP7 was

associated with unfavorable outcomes (Fig. 2J-P). Collectively, these findings

support the hypothesis that the GBP gene family is critically

involved in ccRCC, with individual members exhibiting distinct

clinical relevance. Research specifically targeting GBP5 in ccRCC

has been limited. Therefore, the present study focused on

elucidating the function of GBP5 in ccRCC.

| Figure 2.Expression and prognostic analysis of

GBP1-7 in ccRCC. (A-G) The expression levels of GBP1-7 in KIRC and

matching adjacent tissues were assessed using the gene expression

profiling interactive analysis 2 online tool. Results indicate that

GBP1, GBP2, GBP4 and GBP5 are highly expressed in KIRC tissues. The

mRNA expression of GBP1-6 in ccRCC and adjacent tissues from Gene

Expression Omnibus databases (H) GSE53757 (n=72) and (I) GSE36895

(n=23) was analyzed. Results show that GBP1-6 are highly expressed

in ccRCC tissues. (J-P) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis results

indicate that elevated levels of GBP2 and GBP5 are associated with

a poor prognosis, whereas low expression of GBP3, GBP4 and GBP7 is

associated with unfavorable outcomes. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. GBP, guanylate-binding protein; ccRCC, clear cell

renal cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; TPM,

transcript per million; HR, hazard ratio. |

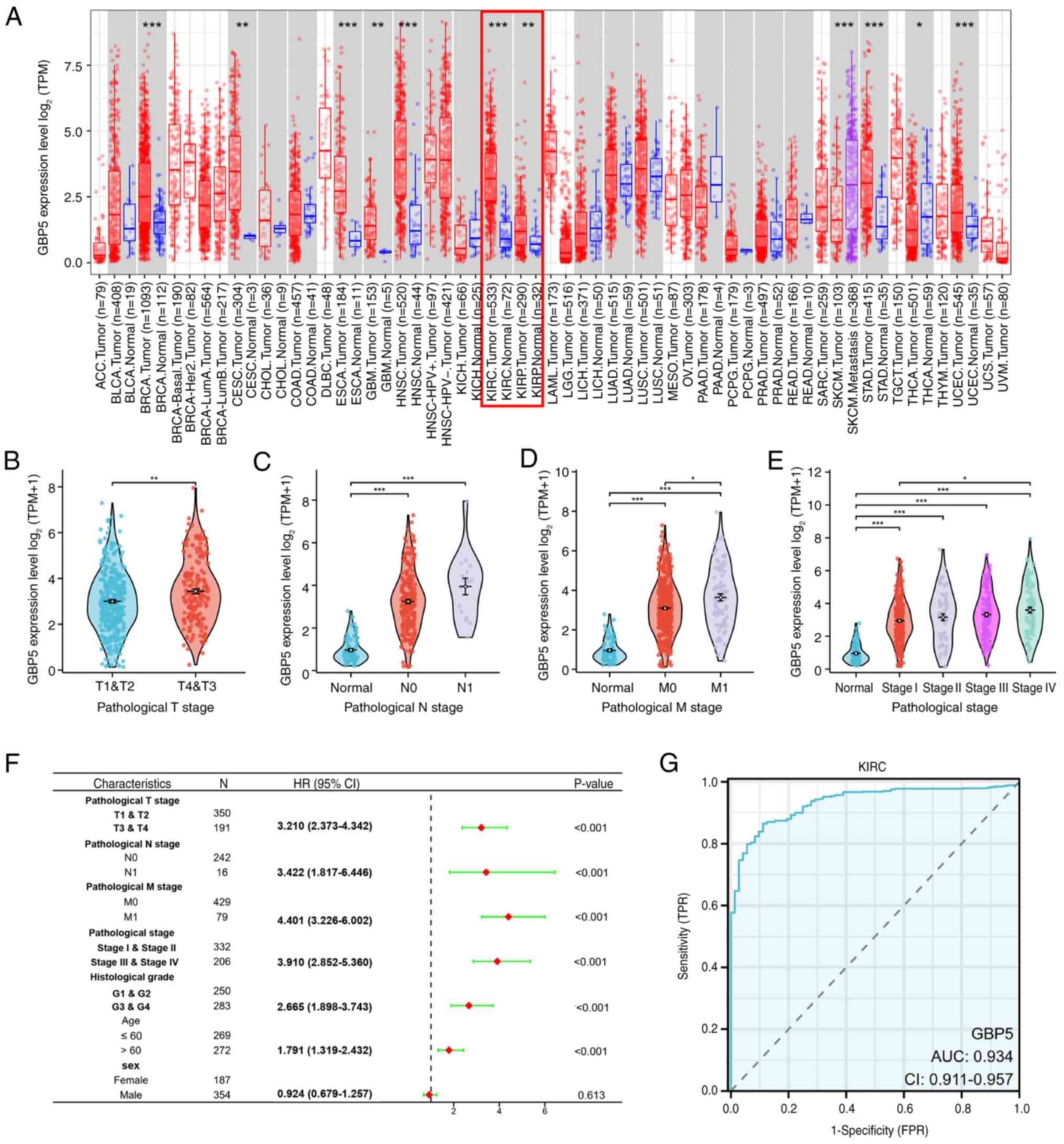

Clinical characteristics and

diagnostic value of GBP5 expression in ccRCC

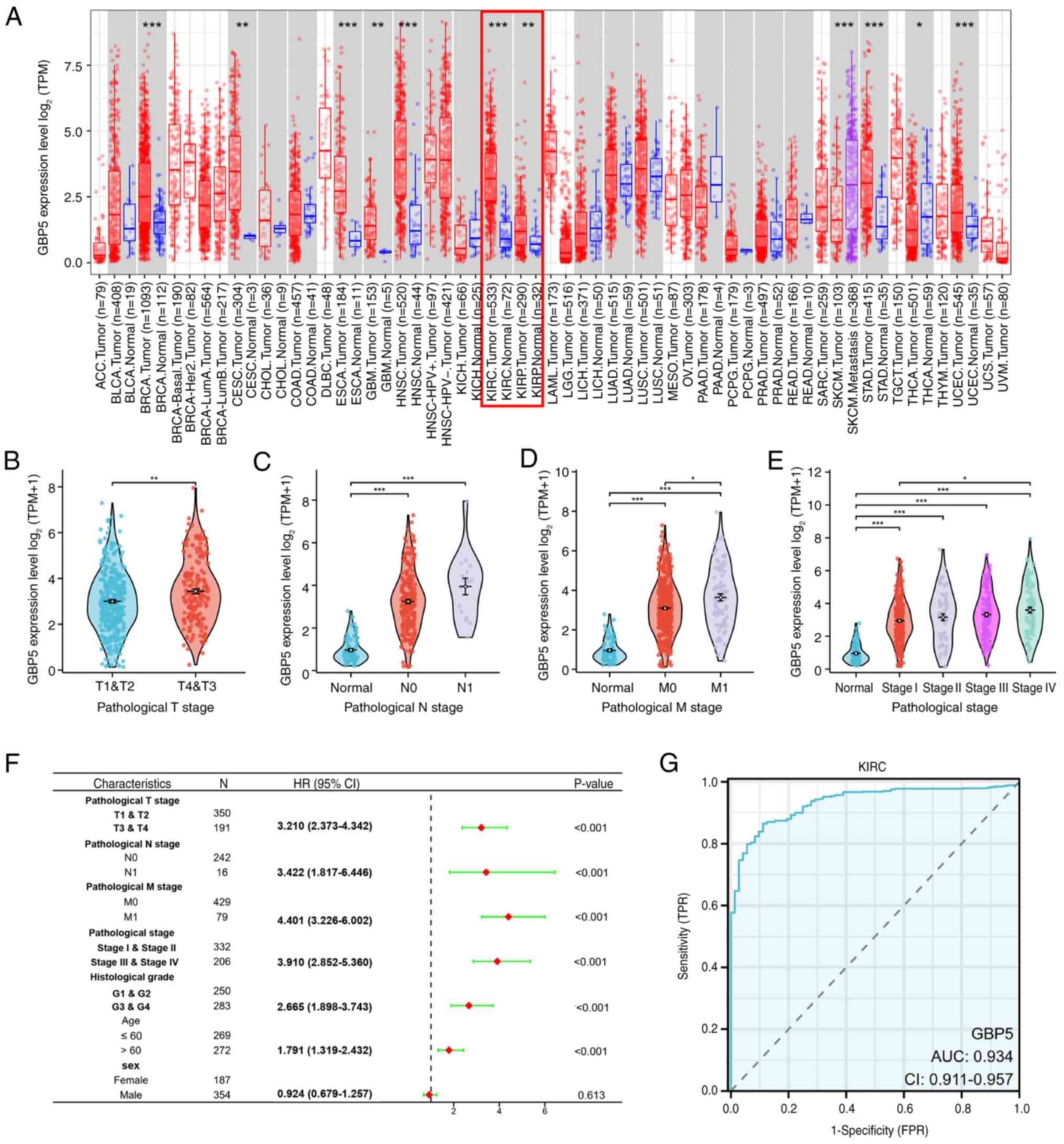

To comprehensively assess the expression profile of

GBP5 across multiple tumor types, the TIMER database was employed.

Analysis showed a marked increase in GBP5 expression across a wide

range of malignancies, including KIRC and kidney renal papillary

cell carcinoma (Fig. 3A). To

investigate the clinical relevance of GBP5 in ccRCC, an in-depth

analysis was performed using transcriptomic and clinical data from

TCGA. Elevated GBP5 expression was significantly associated with

notable clinicopathological factors, including tumor size (T

stage), lymph node involvement (N stage), distant metastasis (M

stage) and both clinical and pathological stage classifications

(Fig. 3B-E). Notably, GBP5

expression increased progressively with advancing tumor stage. In

addition, univariate Cox regression analysis indicated that

elevated GBP5 expression was associated with unfavorable clinical

characteristics in patients with ccRCC (Fig. 3F). To evaluate the diagnostic

potential of GBP5 in ccRCC, ROC curve analysis was performed,

revealing a good diagnostic efficacy with an area under the curve

(AUC) value of 0.934 (Fig. 3G),

suggesting high sensitivity and specificity. These results imply

that GBP5 is a promising diagnostic biomarker involved in the

progression of ccRCC.

| Figure 3.Clinical characteristics of GBP5 in

ccRCC. (A) The analysis of GBP5 mRNA expression in tumor and normal

tissues was performed using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource

2.0. Analysis showed a marked increase in GBP5 expression across a

wide range of malignancies, notably KIRC and KIRP. The association

of GBP5 mRNA expression with different clinical variables in

patients with KIRC, such as (B) T stage, (C) N stage, (D) M stage

and (E) pathological stage. (F) Univariate cox regression analysis

indicates that elevated GBP5 expression is linked to unfavorable

clinical characteristics in patients with ccRCC. (G) Receiver

operating characteristic curve analysis suggests that GBP5 has high

sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of ccRCC, with an AUC

of 0.934. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. GBP5,

guanylate binding protein 5; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell

carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney

renal papillary cell carcinoma; T, tumor; N, lymph node; M,

metastasis; AUC, area under curve; TPM, transcript per million;

TPR, true-positive rate; FDR, false discovery rate. |

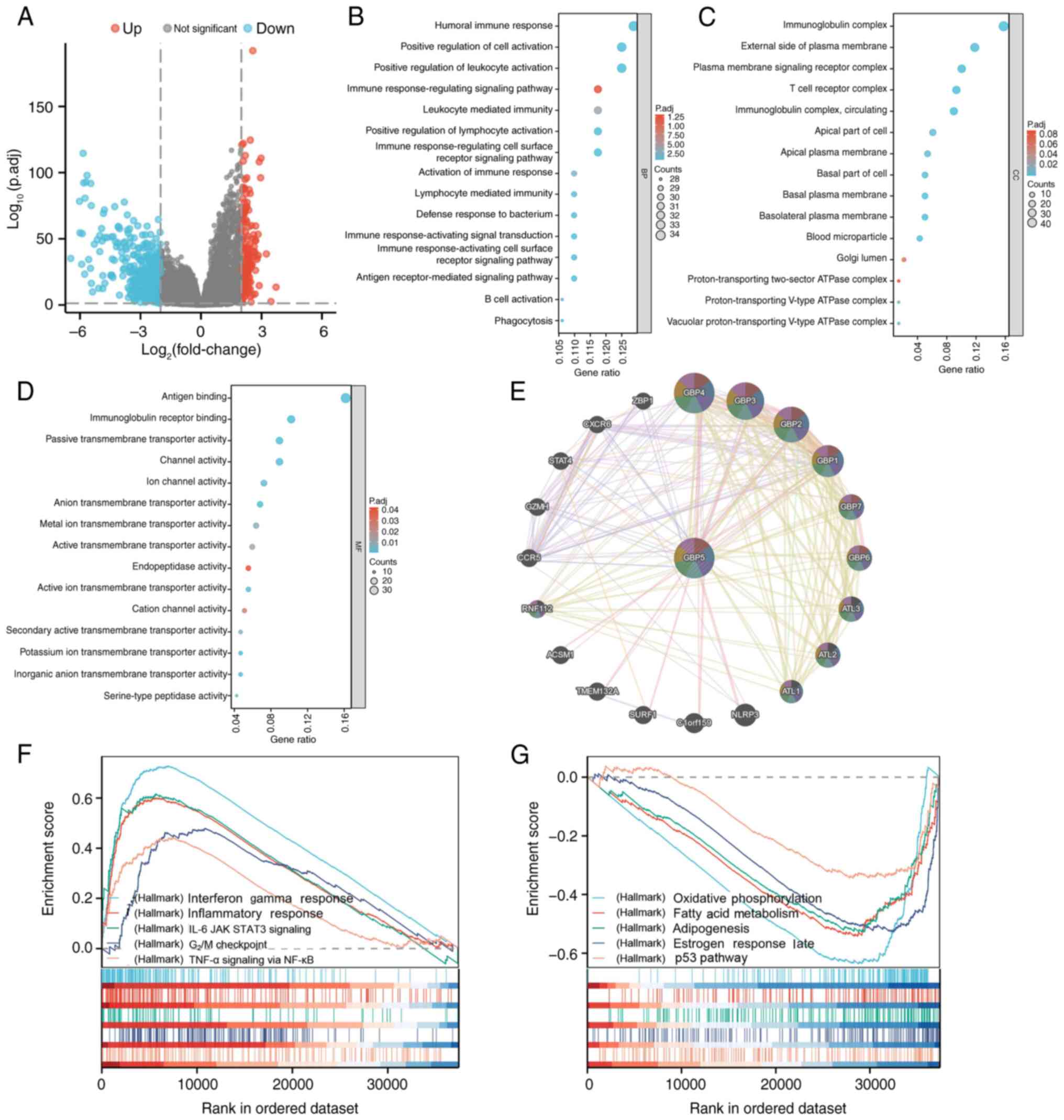

Functional enrichment of GBP5

interaction and expression related genes

To further investigate the potential biological

function of GBP5 in ccRCC, DEG analysis was performed and the

results were visualized using a volcano plot (Fig. 4A). Notably upregulated and

downregulated genes were identified using the criteria:

Log2 fold change >2 and adjusted P-value <0.05.

Enrichment analysis was performed on these DEGs, revealing

significant associations with various GO terms. Specifically, GO

biological process analysis revealed significant enrichment in

‘humoral immune response’, ‘positive regulation of cell

activation’, ‘positive regulation of leukocyte activation’ and

‘immune response-regulation signaling pathways’ (Fig. 4B). The enriched GO cellular

component terms were the ‘immunoglobulin complex’, ‘external side

of plasma membrane’, ‘plasma membrane signaling receptor complex’

and ‘T cell receptor complex’-related components (Fig. 4C). Regarding GO molecular functions,

enrichment was observed in functions such as ‘antigen binding’,

‘immunoglobulin receptor binding’, ‘passive transmembrane

transporter activity’ and ‘channel activity’-associated functions

(Fig. 4D).

Subsequently, GeneMANIA was used to build a

protein-protein interaction network for GBP5 in order to identify

interacting proteins potentially involved in tumorigenesis. Results

indicated that GBP5 exhibited strong co-expression with proteins

such as GBP1, GBP2, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)

and GBP4 (Fig. 4E), implying a

potential interaction between GBP5 and these genes, which could

promote tumor progression.

To further elucidate the biological pathways

regulated by GBP5 across the high and low expression groups, GSEA

was performed. As shown in Fig. 4F,

several biological pathways showed notable enrichment in the high

GBP5 expression group, including IFN-γ response, IL-6/JAK/STAT3

signaling, inflammatory response, G2/M damage checkpoint

and TNF-α signaling through NF-κB. By contrast, pathways such as

oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, adipogenesis,

estrogen response late and the p53 pathway were enriched in the low

GBP5 expression group (Fig. 4G).

According to these findings, GBP5 may influence ccRCC progression

through mechanisms related to tumor immunity, cell cycle regulation

and inflammation.

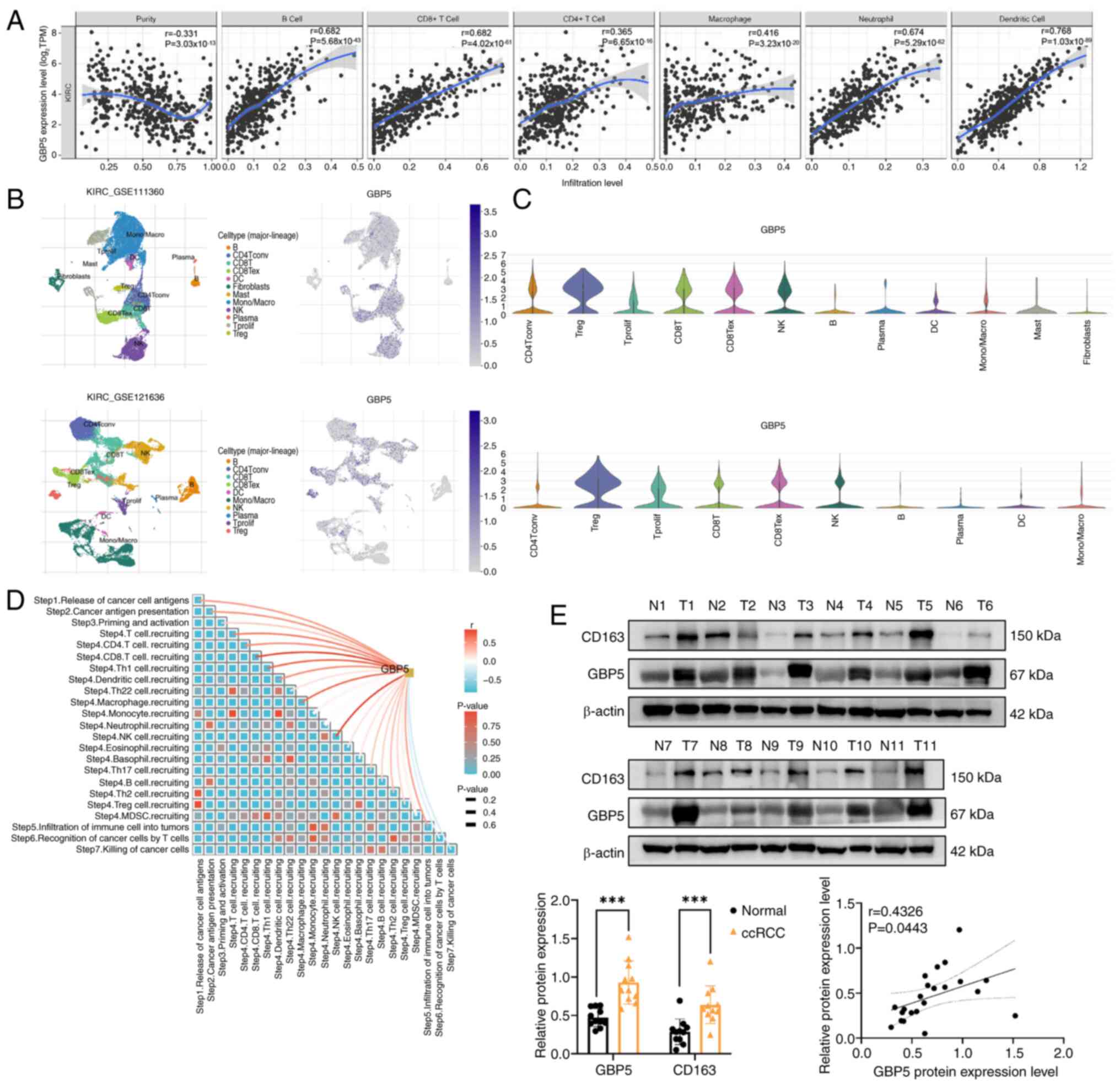

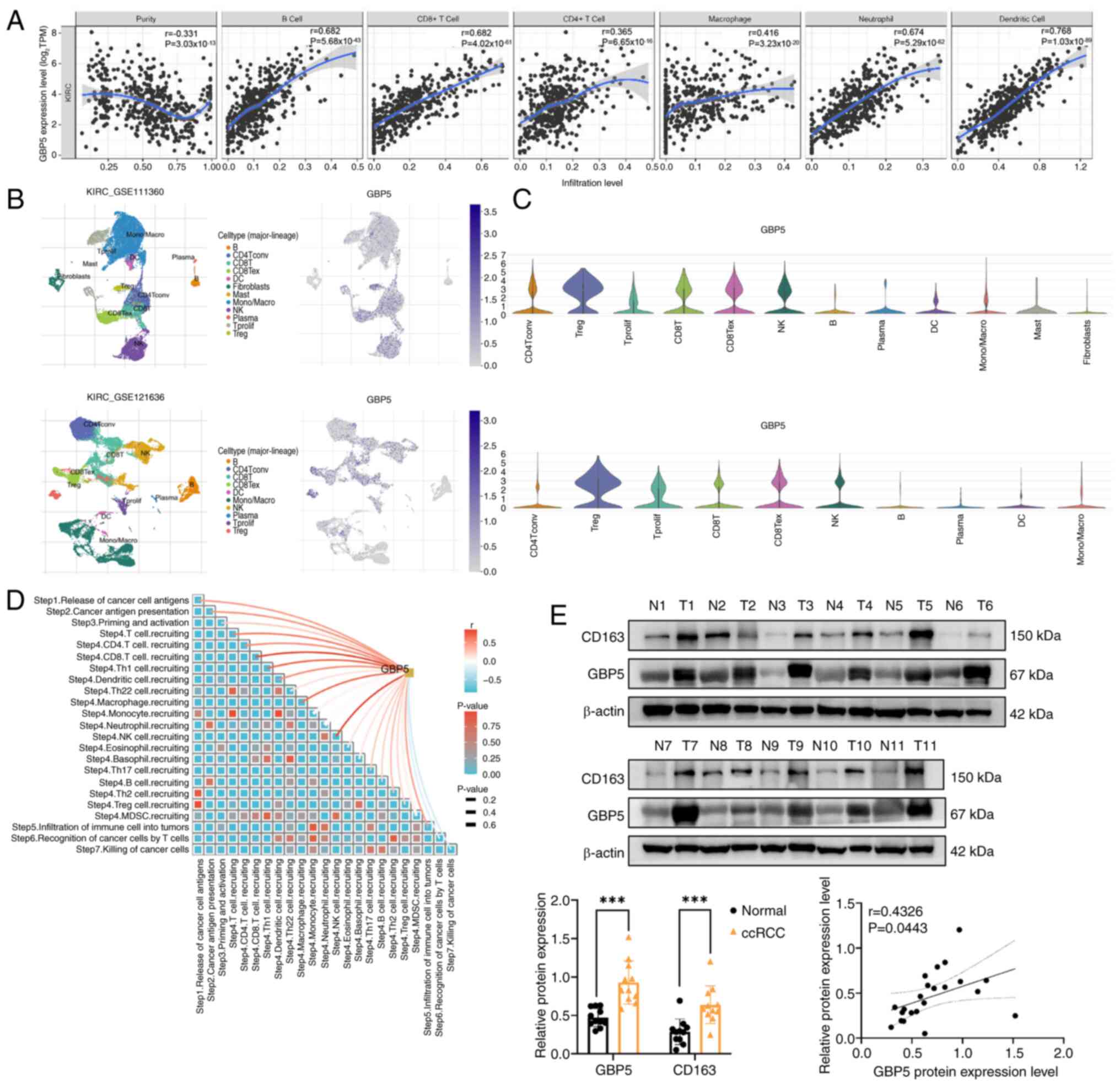

Immune cell infiltration is associated

with GBP5 in ccRCC

To investigate whether GBP5 affects immune cell

infiltration in ccRCC, the TIMER online tool was used to explore

the relationship between GBP5 expression and the abundance of

various immune cell types. In ccRCC, a strong positive correlation

was observed between GBP5 expression and the levels of immune cell

infiltration, including B cells, CD8+ T cells,

CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic

cells (Fig. 5A). These findings

suggest that GBP5 serves a role in immune cell infiltration in

ccRCC. TIMER2.0 was then utilized to conduct a deeper analysis of

the association between GBP5 expression and marker genes of various

immune cells (Table I). The data

revealed strong positive correlations between GBP5 and marker genes

of T cells, CD8+ T cells, M2 macrophages and exhausted T

cells, further supporting the involvement of GBP5 in immune

regulation in ccRCC.

| Figure 5.Relationship between GBP5 expression

and immune cell infiltration in KIRC. (A) Analysis of the Tumor

Immune Estimation Resource database revealed a positive correlation

between GBP5 expression and infiltration levels of B cells,

CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages,

neutrophils and DCs in KIRC. (B and C) The Tumor Immune Single-cell

Hub database was employed to assess the expression of GBP5 in

various tumor microenvironment-associated cellular subpopulations.

In both KIRC GSE111360 and GSE121636 datasets, GBP5 was found to be

highly expressed in CD4+ T cells, proliferating T cells,

regulatory T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cells. (D) The

Tracking Tumor Immunophenotype database was employed to analyze the

immunological features of GBP5. Results indicate a strong positive

correlation between GBP5 and various immune cells, including

macrophages, NK cells and CD8+ T cells. (E) Western

blotting was used to measure GBP5 and CD163 protein levels in the

samples of patients with ccRCC. The levels of GBP5 and CD163 are

significantly higher in ccRCC tissues compared with adjacent normal

tissues and the relative expression levels of GBP5 and CD163

exhibit a positive correlation. ***P<0.001. GBP5,

guanylate-binding protein 5; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell

carcinoma; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; NK, natural

killer; DC, dendritic cells; TPM, transcript per million, N,

normal; T, tumor. |

| Table I.Correlation analysis between

guanylate-binding protein 5 and immune cell markers in the Tumor

Immune Estimation Resource 2.0 database. |

Table I.

Correlation analysis between

guanylate-binding protein 5 and immune cell markers in the Tumor

Immune Estimation Resource 2.0 database.

|

|

| KIRC |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

| None | Purity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Description | Gene markers | r | P-value | r | P-value |

|---|

| CD8+ T

cell | CD8A | 0.838 |

5.76×10−141 | 0.825 |

6.04×10−116 |

|

| CD8B | 0.785 |

3.79×10−119 | 0.767 |

5.25×10−95 |

| T cell

(general) | CD3D | 0.837 |

2.66×10−136 | 0.819 |

1.20×10−108 |

|

| CD3E | 0.852 |

6.79×10−152 | 0.836 |

1.73×10−122 |

|

| CD2 | 0.886 |

5.95×10−175 | 0.873 |

2.72×10−142 |

| B cell | CD19 | 0.474 |

2.97×10−34 | 0.439 |

4.92×10−26 |

|

| CD79A | 0.520 |

4.93×10−34 | 0.486 |

8.87×10−26 |

| Monocyte | CD86 | 0.750 |

2.52×10−95 | 0.726 |

4.68×10−76 |

|

| CD115 (CSF1R) | 0.604 |

2.19×10−54 | 0.556 |

1.39×10−39 |

| TAM | CCL2 | 0.108 |

1.14×10−2 | 0.052 | 0.263 |

|

| CD68 | 0.470 |

1.60×10−15 | 0.455 |

1.05×10−13 |

|

| IL10 | 0.589 |

3.28×10−50 | 0.523 |

2.33×10−34 |

| M1 Macrophage | INOS(NOS2) | 0.046 | 0.287 | −0.02 | 0.667 |

|

| IRF5 | 0.452 |

8.40×10−29 | 0.444 |

4.40×10−24 |

|

| COX2(PTGS2) | 0.068 | 0.114 | 0.028 | 0.548 |

| M2 Macrophage | CD163 | 0.512 |

4.58×10−39 | 0.483 |

0.85×10−30 |

|

| VSIG4 | 0.501 |

8.24×10−37 | 0.445 |

1.28×10−25 |

|

| MS4A4A | 0.563 |

4.87×10−46 | 0.526 |

5.76×10−35 |

| Neutrophils | CD66b

(CEACAM8) | 0.052 | 0.228 | 0.056 | 0.232 |

|

| CD11b (ITGAM) | 0.576 |

3.10×10−49 | 0.529 |

2.51×10−35 |

|

| CCR7 | 0.582 |

1.41×10−48 | 0.538 |

5.35×10−35 |

| Dendritic cell | HLA-DPB1 | 0.765 |

6.03×10−99 | 0.753 |

1.23×10−80 |

|

| HLA-DQB1 | 0.538 |

2.18×10−44 | 0.493 |

4.34×10−34 |

|

| HLA-DRA | 0.778 |

2.89×10−104 | 0.777 |

1.45×10−90 |

|

| HLA-DPA1 | 0.773 |

1.52×10−97 | 0.768 |

8.45×10−83 |

|

| BDCA-1 (CD1C) | 0.305 |

4.19×10−13 | 0.242 |

9.85×10−8 |

|

| BDCA-4 (NRP1) | 0.106 |

2.36×10−3 | 0.058 |

7.69×10−2 |

|

| CD11c (ITGAX) | 0.571 |

3.10×10−47 | 0.536 |

2.97×10−36 |

| Th1 | T-bet (TBX21) | 0.540 |

9.41×10−41 | 0.508 |

6.33×10−30 |

|

| STAT4 | 0.644 |

3.19×10−67 | 0.612 |

1.20×10−51 |

|

| STAT1 | 0.821 |

3.05×10−122 | 0.809 |

6.13×10−102 |

|

| IFN-γ (IFNG) | 0.841 |

3.15×10−147 | 0.823 |

7.02×10−117 |

|

| TNF-α (TNF) | 0.408 |

1.72×10−22 | 0.368 |

1.33×10−15 |

| Th2 | GATA3 | 0.346 |

2.95×10−16 | 0.363 |

1.18×10−15 |

|

| STAT6 | 0.142 |

1.21×10−5 | 0.152 |

3.70×10−5 |

|

| STAT5A | 0.652 |

6.78×10−64 | 0.621 |

1.01×10−49 |

|

| IL13 | 0.112 |

1.73×10−2 | 0.09 | 0.053 |

| Tfh | BCL6 | 0.092 | 0.035 | 0.089 | 0.059 |

|

| IL21 | 0.290 |

4.62×10−44 | 0.275 |

1.62×10−33 |

| Th17 | STAT3 | 0.268 |

4.13×10−11 | 0.242 |

3.34×10−8 |

|

| IL17A | 0.081 | 0.062 | 0.063 | 0.180 |

| Treg | FOXP3 | 0.678 |

2.03×10−68 | 0.651 |

4.99×10−55 |

|

| CCR8 | 0.734 |

3.03×10−96 | 0.719 |

4.66×10−77 |

|

| STAT5B | 0.168 |

2.28×10−5 | 0.179 |

4.09×10−5 |

|

| TGFβ | 0.194 |

2.65×10−6 | 0.157 |

3.51×10−4 |

| T cell

exhaustion | PDCD1 | 0.795 |

3.89×10−118 | 0.781 |

1.82×10−97 |

|

| CTLA4 | 0.773 |

1.90×10−113 | 0.760 |

8.78×10−95 |

|

| LAG3 | 0.815 |

2.78×10−119 | 0.798 |

6.42×10−99 |

|

| TIM-3 (HAVCR2) | 0.371 |

9.92×10−20 | 0.331 |

1.07×10−13 |

|

| GZMB | 0.489 |

1.35×10−33 | 0.444 |

7.90×10−23 |

To validate the relationship between GBP5 expression

and immune cell infiltration in ccRCC, two single-cell RNA datasets

of ccRCC were analyzed from the TISCH2 database. GBP5 expression

was assessed in different TME-associated cell subsets. The results

demonstrated that in both KIRC GSE111360 and GSE121636 datasets,

GBP5 was highly expressed in CD4+ T cells, proliferating

T cells, regulatory T cells, CD8+ T cells and natural

killer (NK) cells (Fig. 5B and

C).

Association between GBP5 and

tumor-associated macrophages

Further analysis of the immunological

characteristics of GBP5 in ccRCC was conducted. Results indicated a

strong positive correlation between GBP5 and various immune cells,

including macrophages, NK cells and CD8+ T cells

(Fig. 5D). To validate the findings

from public databases, western blotting of tumor and adjacent

normal tissues from 11 patients with ccRCC was performed. In ccRCC

tissues, the levels of GBP5 and CD163 were markedly higher compared

with those in adjacent normal tissues. The relative expression

levels of GBP5 and CD163 exhibited a positive correlation (Fig. 5E). These findings underscore the

association between GBP5 and M2 macrophages and suggest a potential

interaction between them.

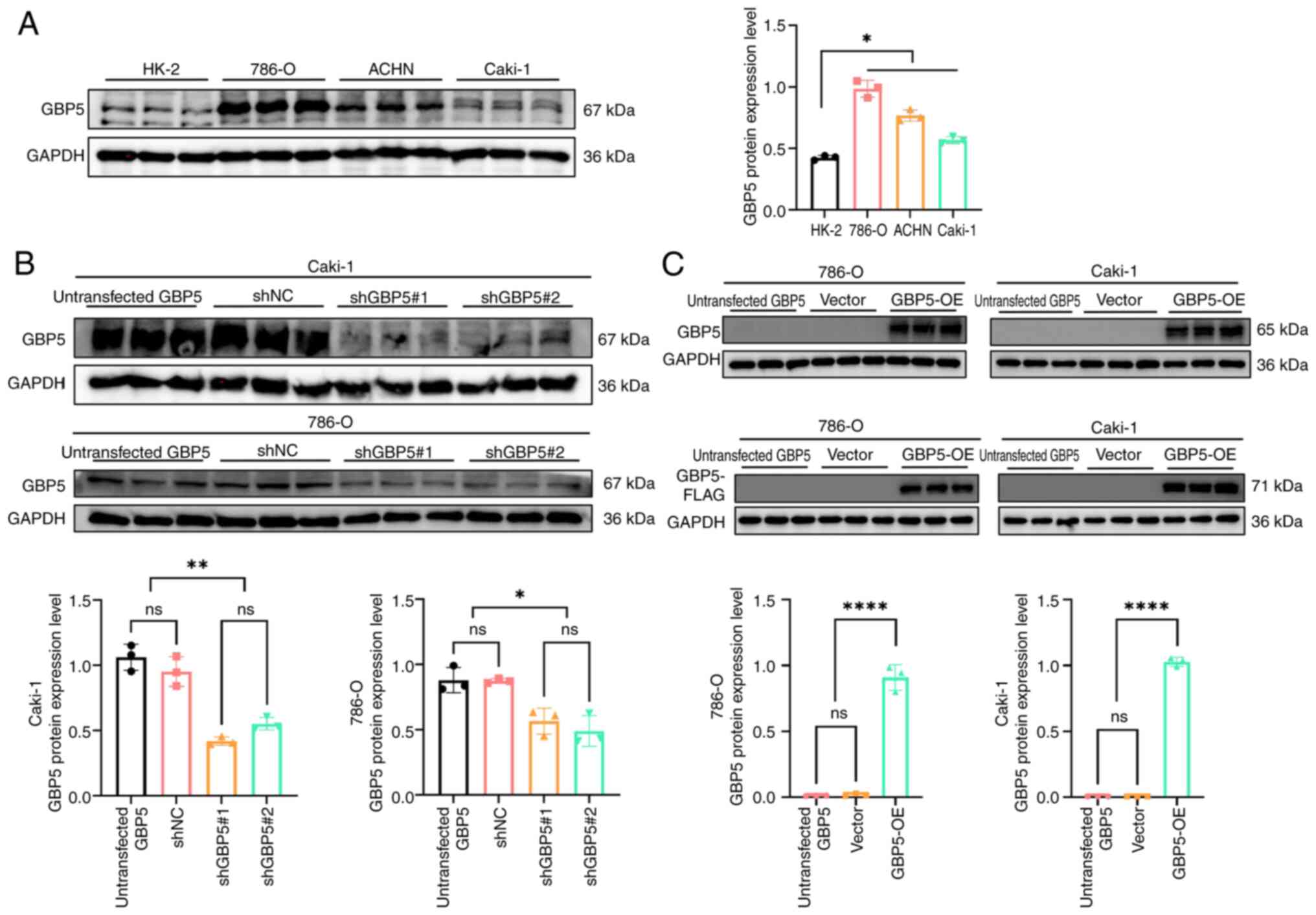

Verification of GBP5 expression and

its effect on the biological behavior of ccRCC

Several in vitro experiments were performed

to investigate the role of GBP5 in ccRCC cells. Western blotting

was performed to assess GBP5 expression in Caki-1, 786-O, ACHN and

HK-2 cells. Findings demonstrated that GBP5 protein levels were

markedly higher in renal cancer cell lines compared with HK-2 cells

(Fig. 6A). For subsequent

experiments, 786-O and Caki-1 cell lines were selected.

The efficiency of lentivirus-mediated gene silencing

was evaluated using western blotting. As shown in Fig. 6B, two lentiviral constructs carrying

different shRNA sequences targeting GBP5 were tested in Caki-1 and

786-O cells. Both shRNA constructs effectively knocked down GBP5

expression, with shGBP5#1 showing improved knockdown efficiency.

Thus, the shGBP5#1 lentivirus was selected to establish stable GBP5

knockdown cell lines. Similarly, GBP5 OE cell lines were generated

using a lentiviral system. Following the exogenous introduction of

GBP5 into 786-O and Caki-1 cells, western blotting analysis

confirmed a significant upregulation of GBP5 expression (Fig. 6C).

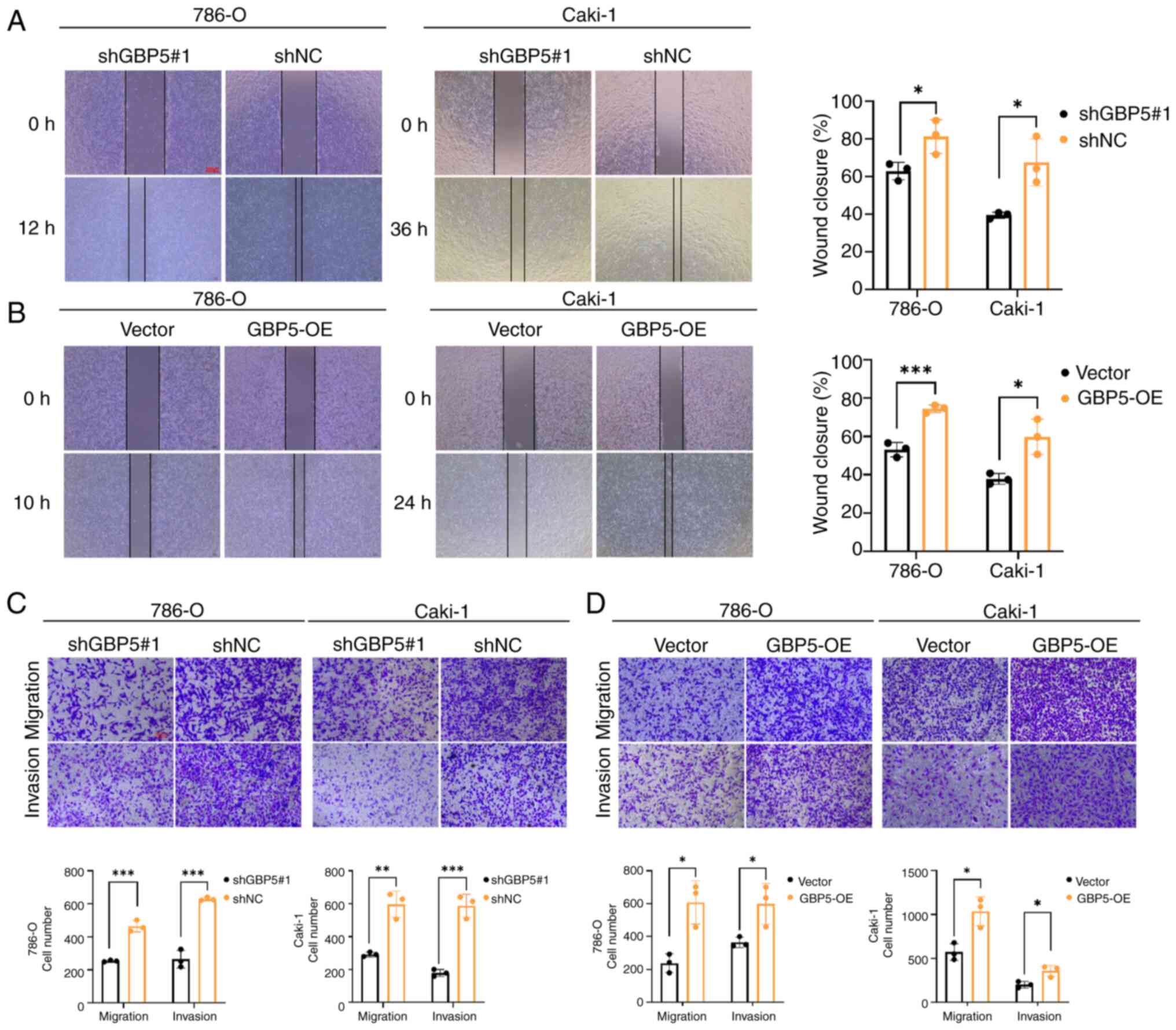

To explore the biological function of GBP5 in cancer

progression, a wound healing assay was performed. Notably, the

suppression of GBP5 expression significantly decreased the

migratory capacity of the cells (Fig.

7A). By contrast, GBP5 overexpression enhanced the

wound-closure rate (Fig. 7B). These

findings were consistently observed in Caki-1 and 786-O cell lines,

indicating that the GBP5-mediated regulation of cell migration is

not cell-type specific.

The Transwell migration assays demonstrated that

GBP5 knockdown inhibited cell migration, whereas GBP5

overexpression significantly promoted it (Fig. 7C and D). In addition, the

Matrigel-coated Transwell invasion assays demonstrated that GBP5

depletion markedly suppressed the invasive capabilities of Caki-1

and 786-O cells, whereas the overexpression of GBP5 exerted the

opposite effect, significantly enhancing cell invasion (Fig. 7C and D).

Discussion

ccRCC is the predominant subtype of RCC. It is

associated with a poor prognosis and also lacks effective

biomarkers. The primary cause of ccRCC-related mortality is the low

rate of early detection and scarcity of effective treatments for

patients with advanced or metastatic disease (40,41).

Consequently, it is key to identify reliable biomarkers for early

detection and prognosis, along with the development of innovative

therapeutic approaches to enhance the clinical outcomes of

ccRCC.

GBP5, which is induced by IFN-γ and classified

within the large GTPase family, is one of seven GBPs with strong

sequence homology that contribute to host defense mechanisms

(42). The function of GBP5 in

cancer, particularly ccRCC, remains largely unclear. In the present

study, GBP5 was recognized as a potential immunotherapeutic target,

exhibiting upregulation in several types of cancer. Previous

studies have highlighted the involvement of GBP5 in the progression

of oral squamous cell carcinoma (23), hepatocellular carcinoma (43), gastric cancer (15) and glioblastoma (16). In the present study, GBP5 was

characterized as a novel biomarker for ccRCC involved in the

tumorigenesis and progression of this malignancy. Findings show

that GBP5 expression was notably increased in ccRCC tissues and was

also associated with a poor prognosis. With this, the results of

the bioinformatics analysis demonstrated that GBP5 exhibited stage-

and grade-specific expression, making it a useful biomarker for

diagnosing and predicting the prognosis of patients with ccRCC.

However, GBP5 has been reported to serve an opposite role in

ovarian cancer (44), likely due to

the complexity of ovarian tumorigenesis and the organ-specific

characteristics, such as lineage-specific transcription factors

(45).

Cancer progression involves a complex array of

immune evasion mechanisms that collectively shape the immunological

characteristics of the TME. Tumor-associated immune cells have been

explored as potential therapeutic biomarkers for cancer (46). In response to pathogen- or

danger-associated molecular patterns, GBP5 serves a key role in the

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (47). It primarily mediates inflammation

and activates macrophages in the innate immune system (48). Previous studies have suggested that

GBP5 may be involved in tumor immunity (17–22).

The efficacy of both targeted therapies and immunotherapies is

influenced by the TME immune landscape (49). Various immune cell types such as T

cells, regulatory tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), T regulatory

cells (Tregs), cancer-associated fibroblasts and myeloid-derived

suppressor cells, serve a role in the TME and contribute to immune

cell infiltration, which is regulated by tumor and

immune-modulating factors (50,51).

Associations between GBP5 expression and several immune cell

markers were observed, including CD8+ T cells, Tregs, T

helper type 1 cells, exhausted T cells, M2 macrophages and

monocytes. Patients with ccRCC showing elevated programmed cell

death protein 1 expression alongside CD8+ T cell and

Treg infiltration tended to have worse clinical outcomes (52–54).

Tregs may contribute to tumor progression and immune escape by

interacting with the TME and suppressing antigen-presenting cell

maturation (55). Although

CD8+ T cell infiltration is elevated in the ccRCC

microenvironment, it does not appear to enhance prognosis, most

likely because of functional T cell exhaustion (56). Moreover, analysis revealed a

positive association between GBP5 expression and CD163, an

established marker of M2-polarized TAMs. M2-like TAMs are commonly

found in tumors and facilitate tumor progression, cell

proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis by secreting

diverse cytokines and chemokines (57–60).

These findings indicate that GBP5 is a possible driver of ccRCC

progression through TAMs.

Cancer metastasis is the primary cause of mortality

in patients with cancer (61).

Regarding cancer biology, GBP5 has been implicated in various

malignant behaviors, including tumor invasion, migration,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cell proliferation and

supporting properties of cancer stem cells (16,23).

Similarly, GBP5 was found to be involved in the regulation of renal

cancer cell invasion and migration, perhaps explaining why patients

with high GBP5 expression in ccRCC exhibit a poor prognosis. With

regards to the molecular mechanisms underlying the function of GBP5

in tumorigenesis, previous research has demonstrated that GBP5

might enhance tumor progression in breast and oral cancers by

upregulating PD-L1 expression and activating NF-κB signaling

(17,23). Additionally, GBP5 accelerates

gastric cancer development by engaging in a

JAK1-STAT1/GBP5/CXCL8-mediated positive feedback circuit (15). In the present study, through

bioinformatic approaches, GBP5 was found to associate with key

oncogenic signaling cascades such as the INF-γ response,

IL-6/JAK/STAT3 axis and the TNF-α/NF-κB network. These pathways are

recognized for their essential roles in both cancer development and

immune regulation (62,63). However, the precise molecular

mechanisms by which GBP5 modulates these pathways in RCC warrants

further investigation.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, the

publicly available ccRCC datasets used in the analyses were limited

in scope, which may have introduced potential errors or biases.

Secondly, while the pro-migratory and pro-invasive roles of GBP5 in

renal cancer cells have been confirmed in vitro, the

underlying molecular mechanisms remain unexplored and no in

vivo validation has been performed. Finally, although GBP5

appears to be related to tumor immune cell infiltration, the

present study lacks supporting in vitro and in vivo

experimental evidence. These limitations must be considered when

interpreting the findings and they will be addressed in future

studies to provide a deeper understanding of the role of GBP5 in

immune cell infiltration and metastasis in ccRCC.

Overall, using bioinformatic analyses and in

vitro experiments, the upregulation of GBP5 in ccRCC was

confirmed. Moreover, immune cell infiltration in ccRCC is

associated with the upregulation of GBP5. In addition, GBP5

facilitates renal cancer cell migration and invasion, suggesting

its usefulness as a prognostic biomarker for poor clinical outcomes

and a promising immunotherapeutic target in ccRCC.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Clinical,

Translational and Basic Research Laboratory of the University of

Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital for providing infrastructure support

and research resources essential to this study.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Medical Scientific

Research Foundation of Guangdong (grant no. B2023384).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding authors.

Authors' contributions

XC, SJY, XX and CL participated in the study design,

conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data and

drafted the initial manuscript. Bioinformatics analysis and some

experimentation was performed by XC, SJY, SY, WZ and ZL. SJY and CL

were also in charge of revising the manuscript, supervising the

study and offering technical experimental support. XC, SJY, XX and

CL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors were

involved in preparing, proofreading and submitting the manuscript.

All authors read, confirmed and approved the final version of the

manuscript, and are accountable for the manuscript's content.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The collection of renal carcinoma tumor tissues and

adjacent normal tissues was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital (approval no. 2024256)

and was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the

Declaration of Helsinki. All donors signed informed consent

forms.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shuch B, Amin A, Armstrong AJ, Eble JN,

Ficarra V, Lopez-Beltran A, Martignoni G, Rini BI and Kutikov A:

Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma:

Distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur

Urol. 67:85–97. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Braun DA, Hou Y, Bakouny Z, Ficial M,

Sant' Angelo M, Forman J, Ross-Macdonald P, Berger AC, Jegede OA,

Elagina L, et al: Interplay of somatic alterations and immune

infiltration modulates response to PD-1 blockade in advanced clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 26:909–918. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Choueiri TK and Motzer RJ: Systemic

therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med.

376:354–366. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Maines F, Caffo O, Veccia A, Trentin C,

Tortora G, Galligioni E and Bria E: Sequencing new agents after

docetaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 96:498–506. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Choueiri TK, Fishman MN, Escudier B,

McDermott DF, Drake CG, Kluger H, Stadler WM, Perez-Gracia JL,

McNeel DG, Curti B, et al: Immunomodulatory activity of nivolumab

in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 22:5461–5471.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Abah MO, Ogenyi DO, Zhilenkova AV, Essogmo

FE, Ngaha Tchawe YS, Uchendu IK, Pascal AM, Nikitina NM, Rusanov

AS, Sanikovich VD, et al: Innovative therapies targeting

drug-resistant biomarkers in metastatic clear cell renal cell

carcinoma (ccRCC). Int J Mol Sci. 26:2652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Linehan WM and Ricketts CJ: Decade in

review-kidney cancer: Discoveries, therapies and opportunities. Nat

Rev Urol. 11:614–616. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Praefcke GJK and McMahon HT: The dynamin

superfamily: Universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules?

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 5:133–147. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Vestal DJ: The guanylate-binding proteins

(GBPs): Proinflammatory cytokine-induced members of the dynamin

superfamily with unique GTPase activity. J Interferon Cytokine Res.

25:435–443. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Shenoy AR, Wellington DA, Kumar P, Kassa

H, Booth CJ, Cresswell P and MacMicking JD: GBP5 promotes NLRP3

inflammasome assembly and immunity in mammals. Science.

336:481–485. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tretina K, Park ES, Maminska A and

MacMicking JD: Interferon-induced guanylate-binding proteins:

Guardians of host defense in health and disease. J Exp Med.

216:482–500. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fellenberg F, Hartmann TB, Dummer R,

Usener D, Schadendorf D and Eichmüller S: GBP-5 splicing variants:

New guanylate-binding proteins with tumor-associated expression and

antigenicity. J Invest Dermatol. 122:1510–1517. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Patil PA, Blakely AM, Lombardo KA, Machan

JT, Miner TJ, Wang LJ, Marwaha AS and Matoso A: Expression of

PD-L1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and the immune microenvironment

in gastric adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 73:124–136. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cao FY, Wang CH, Li X, Ma MZ, Tao GC, Yang

C, Li K, He XB, Tong SL, Zhao QC, et al: Guanylate binding protein

5 accelerates gastric cancer progression via the

JAK1-STAT1/GBP5/CXCL8 positive feedback loop. Am J Cancer Res.

13:1310–1328. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yu X, Jin J, Zheng Y, Zhu H, Xu H, Ma J,

Lan Q, Zhuang Z, Chen CC and Li M: GBP5 drives malignancy of

glioblastoma via the Src/ERK1/2/MMP3 pathway. Cell Death Dis.

12:2032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cheng SW, Chen PC, Lin MH, Ger TR, Chiu HW

and Lin YF: GBP5 repression suppresses the metastatic potential and

PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomedicines.

9:3712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Deng Z, Liu J, Yu YV and Jin YN: Machine

learning-based identification of an immunotherapy-related signature

to enhance outcomes and immunotherapy responses in melanoma. Front

Immunol. 15:14511032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Elsayed I, Elsayed N, Feng Q, Sheahan K,

Moran B and Wang X: Multi-OMICs data analysis identifies molecular

features correlating with tumor immunity in colon cancer. Cancer

Biomark. 33:261–271. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zou C, Shen J, Xu F, Ye Y, Wu Y and Xu S:

Immunoreactive microenvironment modulator GBP5 suppresses ovarian

cancer progression by inducing canonical pyroptosis. J Cancer.

15:3510–3530. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xiang S, Li J, Shen J, Zhao Y, Wu X, Li M,

Yang X, Kaboli PJ, Du F, Zheng Y, et al: Identification of

prognostic genes in the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Front Immunol. 12:6538362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tong Q, Li D, Yin Y, Cheng L and Ouyang S:

GBP5 expression predicted prognosis of immune checkpoint inhibitors

in small cell lung cancer and correlated with tumor immune

microenvironment. J Inflamm Res. 16:4153–4164. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chiu HW, Lin CH, Lee HH, Lu HW, Lin YHK,

Lin YF and Lee HL: Guanylate binding protein 5 triggers NF-κB

activation to foster radioresistance, metastatic progression and

PD-L1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Immunol.

259:1098922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen HQ, Zhao J, Li Y, He LX, Huang YJ,

Shu WQ, Cao J, Liu WB and Liu JY: Gene expression network regulated

by DNA methylation and microRNA during microcystin-leucine arginine

induced malignant transformation in human hepatocyte L02 cells.

Toxicol Lett. 289:42–53. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mitra A, Ghosh S, Porey S and Mal C: GBP5

and ACSS3: Two potential biomarkers of high-grade ovarian cancer

identified through downstream analysis of microarray data. J Biomol

Struct Dyn. 41:4601–4613. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shi Z, Gu J, Yao Y and Wu Z:

Identification of a predictive gene signature related to pyroptosis

for the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Medicine (Baltimore).

101:e305642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Diaz-Montero CM, Rini BI and Finke JH: The

immunology of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Nephrol. 16:721–735.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 47 (W1). W556–W560.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

von Roemeling CA, Radisky DC, Marlow LA,

Cooper SJ, Grebe SK, Anastasiadis PZ, Tun HW and Copland JA:

Neuronal pentraxin 2 supports clear cell renal cell carcinoma by

activating the AMPA-selective glutamate receptor-4. Cancer Res.

74:4796–4810. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Liao

A, Leng N, Pavía-Jiménez A, Wang S, Yamasaki T, Zhrebker L,

Sivanand S, Spence P, et al: BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal

cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 44:751–759. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lánczky A and Győrffy B: Web-based

survival analysis tool tailored for medical research (KMplot):

Development and implementation. J Med Internet Res. 23:e276332021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O,

Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT,

et al: The GeneMANIA prediction server: Biological network

integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function.

Nucleic Acids Res 38 (Web Server Issue). W214–W220. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu

JS, Li B and Liu XS: TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 77:e108–e110. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res 48 (W1). W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Han Y, Wang Y, Dong X, Sun D, Liu Z, Yue

J, Wang H, Li T and Wang C: TISCH2: Expanded datasets and new tools

for single-cell transcriptome analyses of the tumor

microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1): D1425–D1431. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Neal JT, Li X, Zhu J, Giangarra V,

Grzeskowiak CL, Ju J, Liu IH, Chiou SH, Salahudeen AA, Smith AR, et

al: Organoid modeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Cell.

175:1972–1988.e16. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Borcherding N, Vishwakarma A, Voigt AP,

Bellizzi A, Kaplan J, Nepple K, Salem AK, Jenkins RW, Zakharia Y

and Zhang W: Mapping the immune environment in clear cell renal

carcinoma by single-cell genomics. Commun Biol. 4:1222021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xu L, Deng C, Pang B, Zhang X, Liu W, Liao

G, Yuan H, Cheng P, Li F, Long Z, et al: TIP: A web server for

resolving tumor immunophenotype profiling. Cancer Res.

78:6575–6580. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ye S, Li S, Qin L, Zheng W, Liu B, Li X,

Ren Z, Zhao H, Hu X, Ye N and Li G: GBP2 promotes clear cell renal

cell carcinoma progression through immune infiltration and

regulation of PD-L1 expression via STAT1 signaling. Oncol Rep.

49:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cerbone L, Cattrini C, Vallome G, Latocca

MM, Boccardo F and Zanardi E: Combination therapy in metastatic

renal cell carcinoma: Back to the future? Semin Oncol. 47:361–366.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Braun DA, Bakouny Z, Hirsch L, Flippot R,

Van Allen EM, Wu CJ and Choueiri TK: Beyond conventional

immune-checkpoint inhibition-novel immunotherapies for renal cell

carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:199–214. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Santos JC and Broz P: Sensing of invading

pathogens by GBPs: At the crossroads between cell-autonomous and

innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 104:729–735. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Fu J, Qin W, Tong Q, Li Z, Shao Y, Liu Z,

Liu C, Wang Z and Xu X: A novel DNA methylation-driver gene

signature for long-term survival prediction of hepatitis-positive

hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Med. 11:4721–4735. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zahra A, Dong Q, Hall M, Jeyaneethi J,

Silva E, Karteris E and Sisu C: Identification of potential

bisphenol A (BPA) exposure biomarkers in ovarian cancer. J Clin

Med. 10:19792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Arner EN and Rathmell WK: Mutation and

tissue lineage lead to organ-specific cancer. Nature. 606:871–872.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gajewski TF, Schreiber H and Fu YX: Innate

and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat

Immunol. 14:1014–1022. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu P, Ye L, Ren Y, Zhao G, Zhang Y, Lu S,

Li Q, Wu C, Bai L, Zhang Z, et al: Chemotherapy-induced phlebitis

via the GBP5/NLRP3 inflammasome axis and the therapeutic effect of

aescin. Br J Pharmacol. 180:1132–1147. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhou L, Zhao H, Zhao H, Meng X, Zhao Z,

Xie H, Li J, Tang Y and Zhang Y: GBP5 exacerbates rosacea-like skin

inflammation by skewing macrophage polarization towards M1

phenotype through the NF-κB signalling pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol

Venereol. 37:796–809. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wilkie KP and Hahnfeldt P: Tumor-immune

dynamics regulated in the microenvironment inform the transient

nature of immune-induced tumor dormancy. Cancer Res. 73:3534–3544.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Heidegger I, Pircher A and Pichler R:

Targeting the tumor microenvironment in renal cell cancer biology

and therapy. Front Oncol. 9:4902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Najjar YG, Rayman P, Jia X, Pavicic PJ Jr,

Rini BI, Tannenbaum C, Ko J, Haywood S, Cohen P, Hamilton T, et al:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell subset accumulation in renal cell

carcinoma parenchyma is associated with intratumoral expression of

IL1β, IL8, CXCL5, and Mip-1α. Clin Cancer Res. 23:2346–2355. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Dai S, Zeng H, Liu Z, Jin K, Jiang W, Wang

Z, Lin Z, Xiong Y, Wang J, Chang Y, et al: Intratumoral

CXCL13+CD8+T cell infiltration determines

poor clinical outcomes and immunoevasive contexture in patients

with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0018232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Giraldo NA, Becht E, Pagès F, Skliris G,

Verkarre V, Vano Y, Mejean A, Saint-Aubert N, Lacroix L, Natario I,

et al: Orchestration and prognostic significance of immune

checkpoints in the microenvironment of primary and metastatic renal

cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 21:3031–3040. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Giraldo NA, Becht E, Vano Y, Petitprez F,

Lacroix L, Validire P, Sanchez-Salas R, Ingels A, Oudard S, Moatti

A, et al: Tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood t-cell

immunophenotypes predict early relapse in localized clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 23:4416–4428. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Paluskievicz CM, Cao X, Abdi R, Zheng P,

Liu Y and Bromberg JS: T Regulatory cells and priming the

suppressive tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 10:24532019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Braun DA, Street K, Burke KP, Cookmeyer

DL, Denize T, Pedersen CB, Gohil SH, Schindler N, Pomerance L,

Hirsch L, et al: Progressive immune dysfunction with advancing

disease stage in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 39:632–648.e8.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi

L and Allavena P: Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment

targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:399–416. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Pittet MJ, Michielin O and Migliorini D:

Clinical relevance of tumour-associated macrophages. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 19:402–421. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Xiang X, Wang J, Lu D and Xu X: Targeting

tumor-associated macrophages to synergize tumor immunotherapy.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zheng W, Ye S, Liu B, Liu D, Yan R, Guo H,

Yu H, Hu X, Zhao H, Zhou K and Li G: Crosstalk between GBP2 and M2

macrophage promotes the ccRCC progression. Cancer Sci.

115:3570–3586. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Meirson T, Gil-Henn H and Samson AO:

Invasion and metastasis: The elusive hallmark of cancer. Oncogene.

39:2024–2026. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yu H, Pardoll D and Jove R: STATs in

cancer inflammation and immunity: A leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev

Cancer. 9:798–809. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA and Grandis JR:

Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 15:234–248. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|