Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is among the

most lethal malignancies, characterized by an extremely poor

prognosis (1,2). In recent years, neoadjuvant

chemotherapy has become the standard treatment for borderline

resectable PDAC (3–5). Moreover, even in patients initially

diagnosed with unresectable PDAC, surgical resection following a

favorable response to chemotherapy has been shown to improve

survival outcomes (6).

Additionally, several studies suggest that neoadjuvant chemotherapy

may also be beneficial for patients with resectable PDAC (7,8). These

findings demonstrate the important role of chemotherapy in the

multidisciplinary management of PDAC.

Several chemotherapeutic regimens are currently

available for the treatment of PDAC. However, their efficacies vary

among patients. In some cases, tumor progression has been observed

despite treatment, resulting in loss of resectability (9). Therefore, the development of

personalized treatment strategies based on tumor characteristics is

becoming an important consideration for optimizing the selection of

chemotherapy for PDAC.

In a previous study, we found that a higher tumor

blood flow (TBF) prior to treatment was associated with a better

response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (10). However, that study was limited by

its small sample size and lack of stratification according to the

chemotherapy regimen. Furthermore, PDAC generally possesses an

intense stromal pathology surrounding cancer cells, which is called

desmoplastic stroma (2,11). Desmoplastic stroma leads to high

intra-tumoral tissue pressure, blood vessel collapse, and decreased

tumor perfusion (12). Chemotherapy

may affect desmoplastic stroma by reducing the number of cancer

cells. Furthermore, the previous report described the experience of

tumor molecular and cellular alterations in PDAC (13). Therefore, it is important to

evaluate not only pre-treatment TBF but also post-treatment TBF.

Although one study examined changes in TBF after chemotherapy

(14), a comparison between pre-

and post-treatment TBF according to chemotherapy regimen has not

been explored.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the

association between pre-treatment TBF and histopathological

therapeutic response stratified by chemotherapy regimen and to

assess changes in TBF before and after chemotherapy. In addition,

intra-tumoral vessels, which may affect the TBF, were evaluated

using immunostaining.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

We conducted a retrospective review of the

electronic medical records at Shiga University of Medical Science

Hospital between January 2011 and December 2023 to identify

patients who underwent pancreatectomy following preoperative

chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for PDAC. The medical records of

the patients were accessed for the purpose of this study in April

2024. A total of 58 consecutive patients who underwent

contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) before the initiation

of preoperative therapy were included. Clinical and pathological

data were collected for the analysis.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Shiga University of Medical Science (approval number R2017-171) and

was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the

Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the

patients or their legal representatives on an opt-out basis.

CECT examinations protocol and image

analysis

Three-phase CECT examinations were performed using a

64-detector row computed tomography (CT) scanner (Aquilion CX

Edition; Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan). An

intravenous bolus of 100 ml of nonionic iodinated contrast material

(Iopamiron®, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) was

administered at a dose of ≥600 mgI/kg body weight and an injection

rate of 3 ml/s through the median cubital vein. Scans were acquired

with a slice thickness of 5 mm according to institutional

protocols. Imaging was performed at 35 s (arterial phase), 70 s

(portal venous phase), and 130 s (late phase) after contrast

injection.

CT images were independently reviewed by two

experienced surgeons, each with >10 years of expertise in

pancreatic imaging, who were blinded to all clinical and

pathological data. Tumor and aortic attenuation values were

measured during each phase (non-enhanced, arterial, portal venous,

and late) using a picture archiving and communication system

(ShadeQuest/ViewR-DG; Yokogawa Medical Solutions Corporation,

Tokyo, Japan). In cases of discrepancies, a consensus was reached

through a joint review.

Tumor attenuation values (TAV) and aortic

attenuation values (AAV) were determined following a previously

described methodology (10,15). Regions of interest were drawn to

encompass as much of the tumor and aorta as possible, while

avoiding their margins. For tumor measurements, cystic or vascular

regions were excluded. The average of three measurements per phase

was recorded. In all cases, the peak aortic enhancement occurred at

35 s.

TBF was calculated using the maximum slope method

[10, 14]:

The previous study demonstrated that TBF ≥0.36

s−¹ provides prediction of the destruction of over 50%

of tumor cells in PDAC (10).

Hence, the patients were classified into two groups according to

the pre-treatment TBF: the high TBF group (TBF ≥0.36

s−¹) and the low TBF group (TBF <0.36

s−¹).

Assessment of therapeutic pathological

response

The therapeutic pathological response was graded

according to the Japanese classification of pancreatic carcinoma by

the Japan Pancreas Society: Eight edition (16). The evaluations were performed by two

specialized pancreatic pathologists who were blinded to the

clinical outcomes. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from the

largest cross-section of the tumor were assessed.

Assessment of intra-tumoral vessels by

CD31 immunostaining

The tissue specimens were cut into 4 µm slices from

10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks. The specimens were

then deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval

by heating the slides in distilled water at 98°C for 45 min with an

antigen retrieval solution (Immunosaver®, Nisshin EM,

Tokyo, Japan). The slides were then treated in 3%

H2O2 in methanol for 10 min at 25°C to block

endogenous peroxidase activity. To prevent nonspecific protein

binding, the slides were treated with Blocking One Hist (Nacalai

Tesque) and incubated overnight with a monoclonal antibody against

CD31 (1:50, MA5-16337, Invitrogen, CA, USA). Subsequently, they

were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled

polymer-conjugated secondary antibody [Simple Stain MAX PO (MULTI);

Nichirei Bioscience] at 25°C for 30 min. The antigen was visualized

by diaminobenzidine staining (#415172; Nichirei Bioscience)

chromogen for 2–5 min. Finally, the slides were counterstained with

hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Negative controls were

prepared by excluding the primary antibodies.

The tumor sections were examined under a microscope.

Image analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The CD31-positive area

ratio was determined by evaluating five randomly selected fields,

excluding the adenocarcinoma ductal structures. For vessel

quantification, five high-power fields (200× magnification) were

selected and patent (open-lumen) vessels were visually counted.

Clinical data collection and

statistical analysis

The patient characteristics were compared between

the low and high TBF groups. Categorical variables are expressed as

numbers and percentages (%), whereas continuous variables are

expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. Fisher's exact test

(for categorical variables) and the Mann-Whitney U test (for

continuous variables) were used to evaluate significant differences

between the two groups. The Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test was used

to examine the trends. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to

evaluate significant difference between pre-treatment and

post-treatment TBF in each regimen. Spearman's rank correlation

analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between the

intra-tumoral vessels and the post-treatment TBF. In two-tailed

tests, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All

statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical

Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user

interface for R software (The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, version 2.13.0, Vienna, Austria) (17) and Bell Curve for Excel software

version 3.23 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo,

Japan).

Results

Comparison of clinical features

between high and low TBF groups

A total of 58 patients were enrolled in the study.

Of these, 35 (60.3%) were categorized into the low TBF group and 23

(39.7%) into the high TBF group. The treatment regimens included

gemcitabine plus S-1 (GS, n=23), gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel

(GnP, n=18), and modified FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX, n=17). The

clinical characteristics of each group are summarized in Table I. There were no significant

differences between the groups in pre-treatment tumor size or tumor

marker levels, including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate

antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and Duke pancreatic monoclonal antigen type

2 (DUPAN-2). Additionally, no significant differences were observed

in pre-treatment duration, treatment regimen, or resectability

classification. Furthermore, the pre-treatment duration showed no

significant differences between low and high TBF groups according

to the treatment regimen (P=0.708 in GS, P=0.138 in GnP, and

P=0.768 in mFOLFIRINOX, respectively). The patients who received

chemoradiotherapy did not show significant differences between low

and high TBF groups (8.6% vs. 8.7%, P=1.000). However,

post-treatment tumor size (P=0.046) and DUPAN-2 (P=0.044) were

significantly lower in the high TBF group. Moreover,

pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed significantly more frequently

in the high TBF group (P=0.004). Although no significant difference

was found in the RECIST classification between groups, the

prevalence of a therapeutic pathological response of Grade II or

higher was significantly greater in the high TBF group (P=0.027).

The overall survival was significantly better in the high TBF group

than that in the low TBF group (not reached vs. 27 months,

P=0.043). Furthermore, the progression-free survival was better in

the high TBF group than that in low TBF group (55 months vs. 10

months, P=0.002).

| Table I.Clinical features in the high and low

pre-treatment TBF groups. |

Table I.

Clinical features in the high and low

pre-treatment TBF groups.

| Factors | Low TBF group

(n=35) | High TBF group

(n=23) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, male | 25 (71.4) | 11 (47.8) | 0.098 |

| Age, years | 65.0 (62.5,

71.5) | 69.0 (61.0,

72.0) | 0.556 |

| Resectability |

|

| 0.286 |

|

Resectable | 14 (40.0) | 8 (34.8) |

|

|

Borderline-resectable | 10 (28.6) | 11 (47.8) |

|

|

Unresectable | 11 (31.4) | 4 (17.4) |

|

| Pre-treatment CEA,

ng/dl | 4.0 (2.5, 5.5) | 4.0 (3.2, 7.2) | 0.643 |

| Pre-treatment CA19-9,

U/l | 114 (33, 215) | 114 (33, 215) | 0.279 |

| Pre-treatment

DUPAN-2, U/l | 270 (74, 1,400) | 145 (37, 1,020) | 0.698 |

| Pre-treatment tumor

size, mm | 32.4 (28.0,

44.0) | 26.2 (23.5,

37.3) | 0.057 |

| Pre-treatment

regimen |

|

| >0.999 |

| GS | 14 (40.0) | 9 (39.1) |

|

|

GnP | 11 (31.4) | 7 (30.4) |

|

|

mFOLFIRINOX | 10 (28.6) | 7 (30.4) |

|

| Pre-treatment

period, months | 3.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) | 0.453 |

| Chemoradiotherapy,

yes | 3 (8.6) | 2 (8.7) | >0.999 |

| Post-treatment CEA,

ng/dl | 4.7 (2.4, 5.7) | 3.6 (2.9, 6.4) | 0.905 |

| Post-treatment

CA19-9, U/l | 41 (23, 77) | 33 (18, 59) | 0.279 |

| Post-treatment

DUPAN-2, U/l | 98 (25, 338) | 25 (25, 92) | 0.044a |

| Post-treatment

tumor size, mm | 26.2 (19.0,

33.5) | 22.1 (17.5,

27.5) | 0.046a |

| RECIST

classification |

|

| 0.427 |

|

Progressive disease | 1 (2.9) | 1 (4.3) |

|

| Stable

disease | 23 (65.7) | 11 (47.8) |

|

| Partial

response | 11 (31.4) | 11 (47.8) |

|

| Surgical procedure,

PD | 18 (51.4) | 21 (91.3) | 0.004a |

| Pathological

response, at least grade II | 8 (22.9) | 12 (52.2) | 0.027a |

Association between TBF and

therapeutic pathological response in each regimen

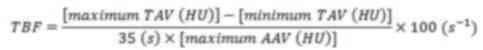

Fig. 1 illustrates

the association between TBF and therapeutic pathological responses.

In the mFOLFIRINOX group, a higher TBF was significantly associated

with a better therapeutic pathological response, as assessed using

the Jonckheere-Terpstra test (P=0.010). In contrast, TBF was not

associated with therapeutic response in patients receiving GnP

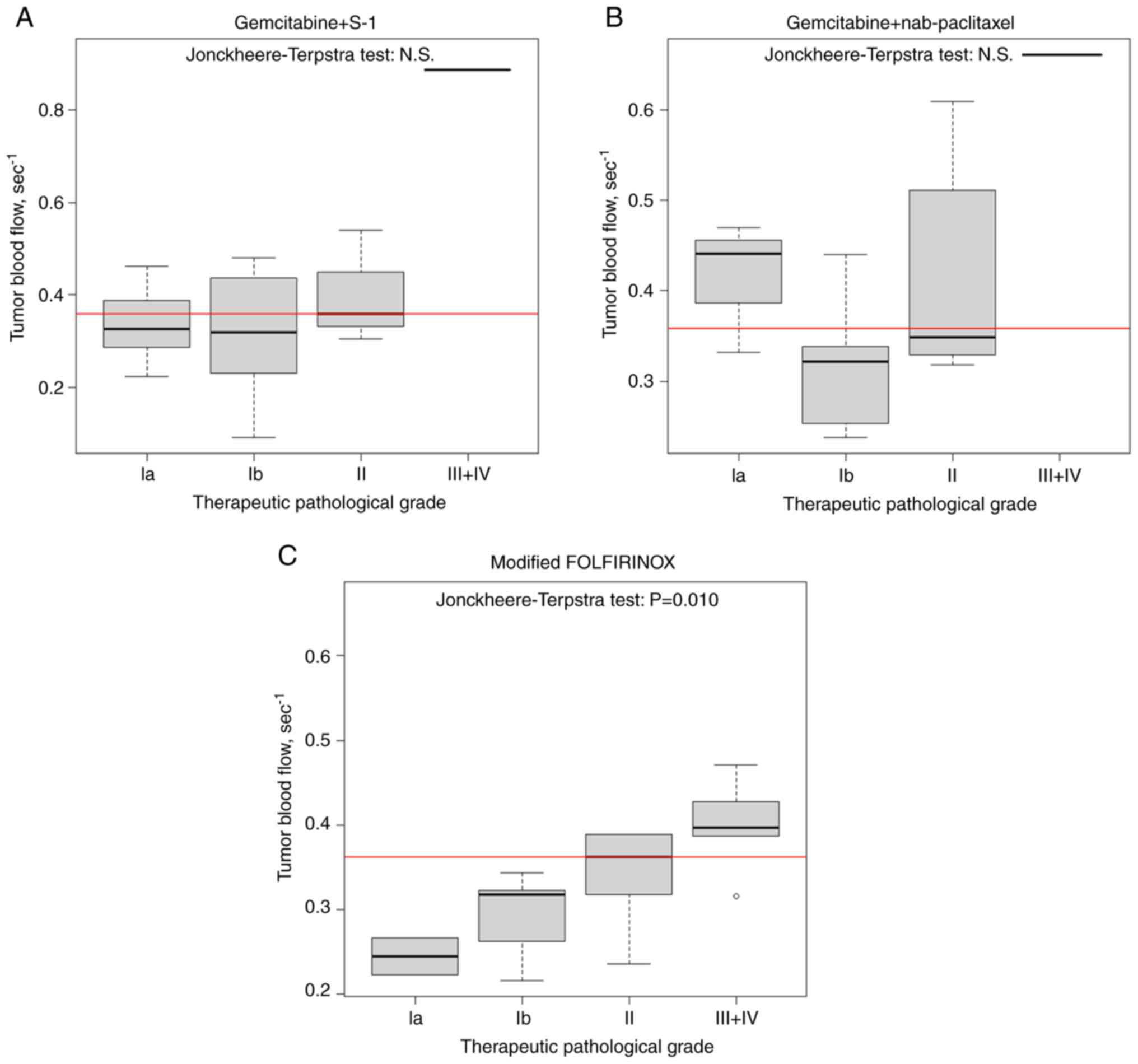

(P=0.490) or GS (P=0.387). Fig. 2

shows the therapeutic pathological response according to regimen in

the low and high TBF groups. In the low TBF group, approximately

90% of patients treated with GnP achieved a therapeutic

pathological response of Grade Ib or higher, compared to 80% of

patients treated with mFOLFIRINOX and approximately 65% of those

treated with GS. These findings suggest that GnP is more effective

than mFOLFIRINOX or GS in patients with a low TBF. Conversely, in

the high TBF group, mFOLFIRINOX demonstrated greater efficacy than

GnP or GS.

Between January 2024 and August 2025, we treated few

new cases; Case 1: Patient with resectable PDAC who received

mFOLFIRINOX for 2 months, followed by radical resection. The TBF

was 0.43, and the therapeutic pathological response was Grade II.

Case 2: Patient with resectable PDAC who received GnP for 2 months,

followed by radical resection. The TBF was 0.24, and the

therapeutic pathological response was Grade II. Case 3: Patient

with resectable PDAC who received GS for 2 months, followed by

radical resection. The TBF was 0.43, and the therapeutic

pathological response was Grade Ia. The medical records of these

patients were accessed in August 2025.

Change in TBF following treatment in

each regimen

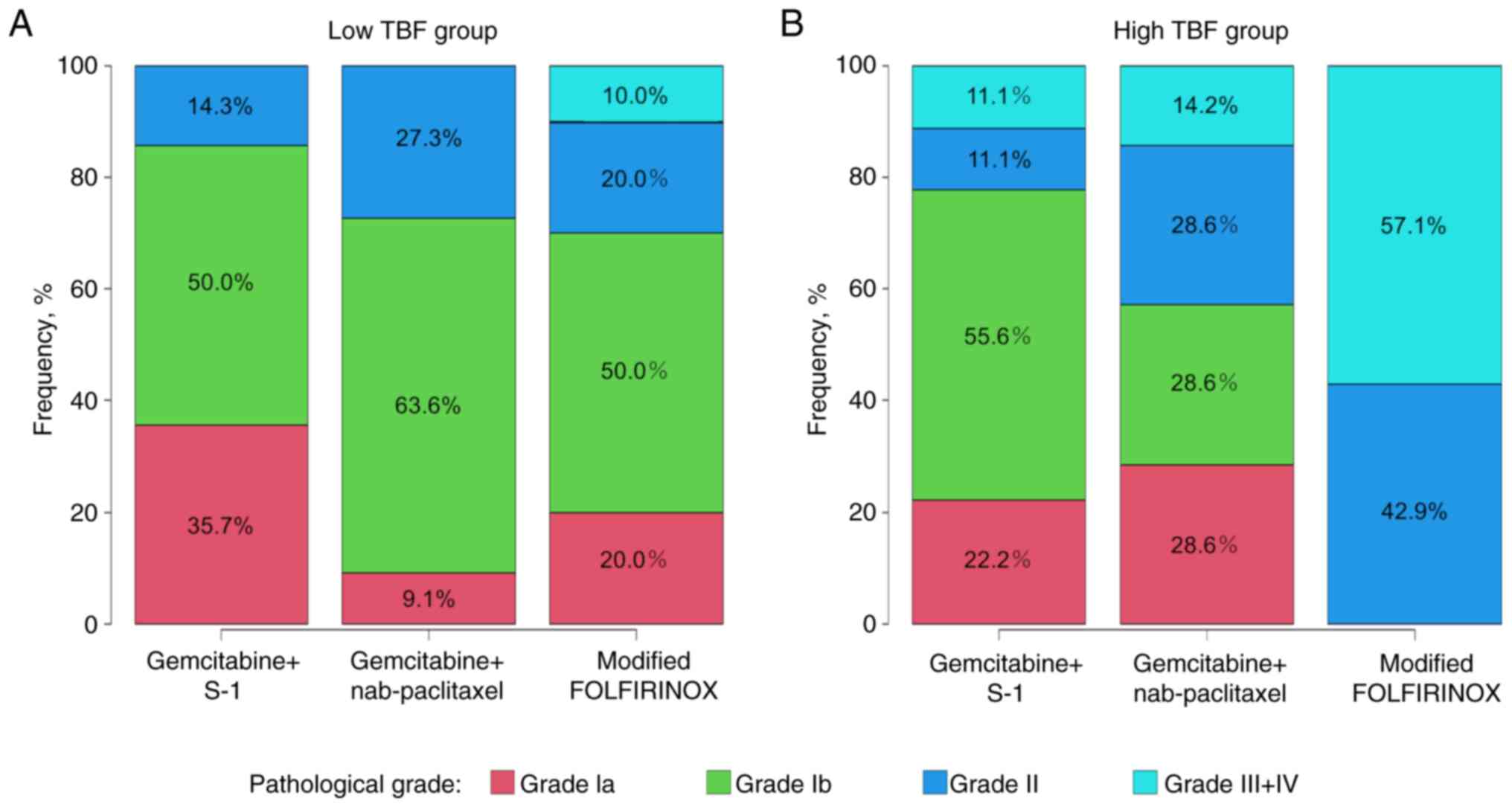

The changes in TBF before and after treatment for

each regimen are shown in Fig. 3.

No significant differences were observed between the pre- and

post-treatment TBF values for mFOLFIRINOX and GS. However, the

post-treatment TBF significantly increased after GnP treatment

(P=0.018). Furthermore, among patients in the low TBF group,

post-treatment TBF significantly increased after GnP treatment

(P=0.004), whereas TBF remained unchanged in patients treated with

mFOLFIRINOX (P=0.445) or GS (P=0.397).

Association between the post-treatment

TBF and the intra-tumoral vessels

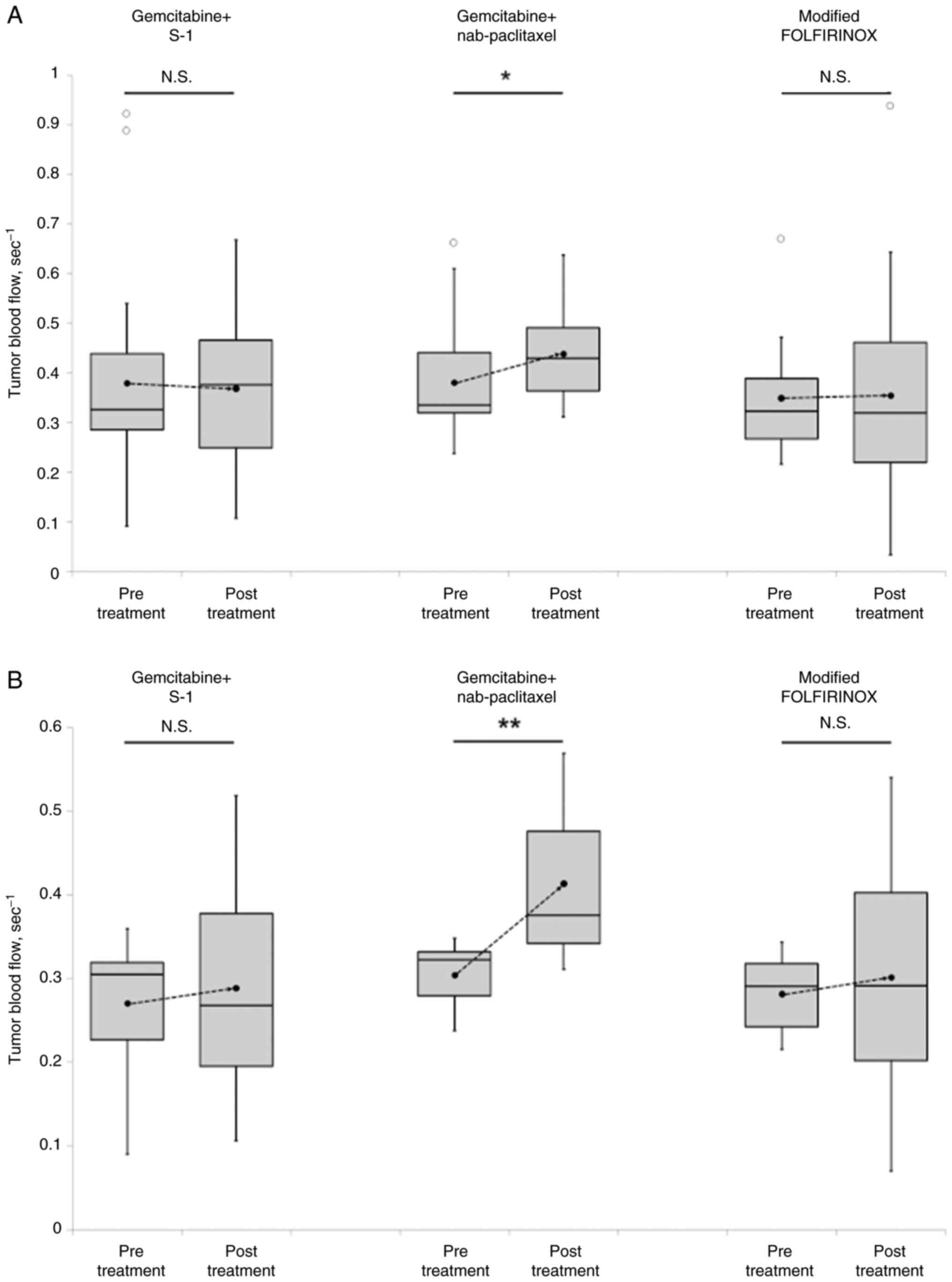

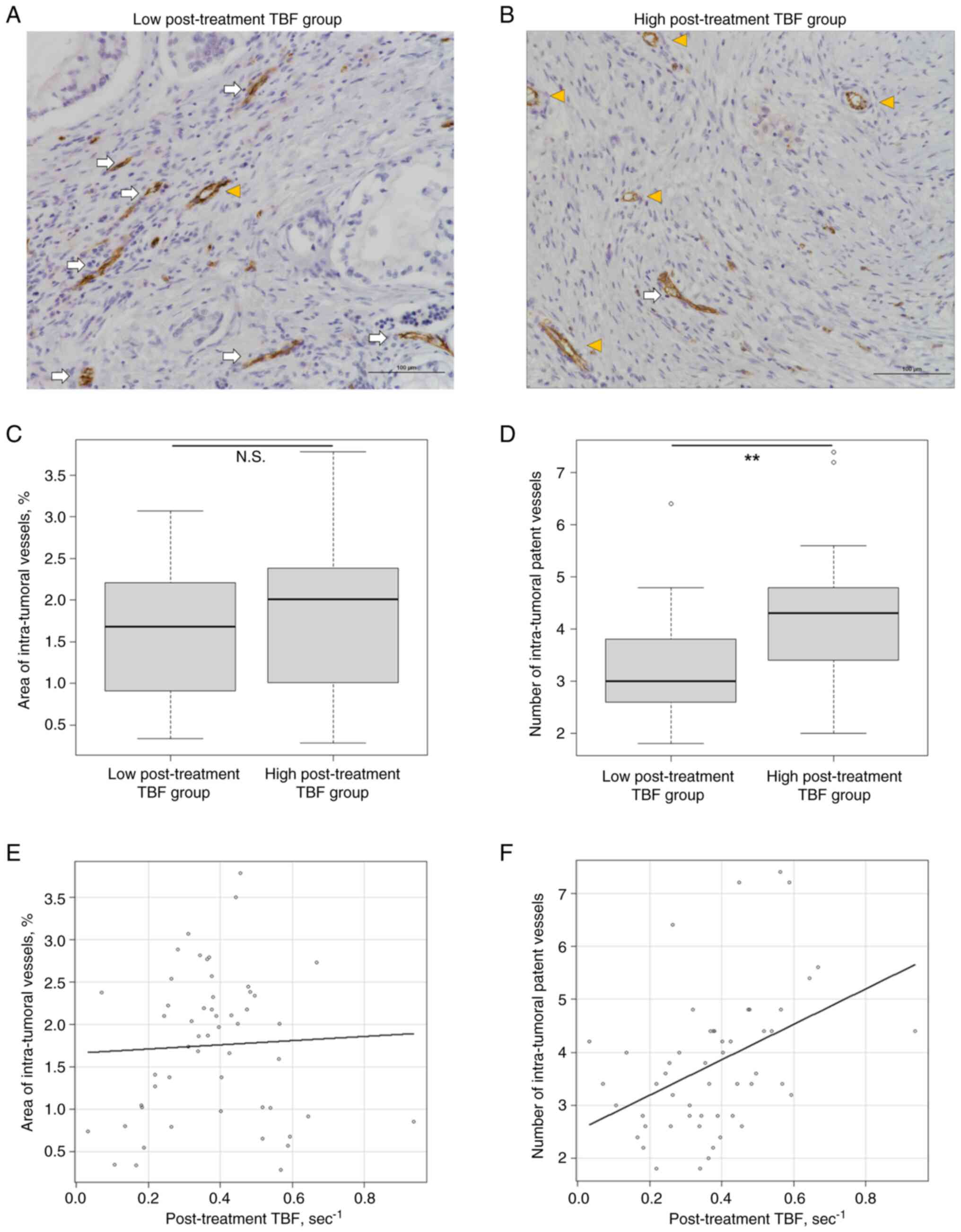

We further evaluated intra-tumoral vessels using

CD31 immunostaining (Fig. 4). The

number of intra-tumoral patent vessels was significantly higher in

the high post-treatment TBF group (P=0.006). However, the areas of

the intra-tumoral vessels were not significantly different between

the two groups (P=0.428). Regarding the correlation between

post-treatment TBF and intra-tumoral vessels, post-treatment TBF

did not correlate with the area of intra-tumoral vessels. However,

a higher post-treatment TBF was significantly associated with a

greater number of intra-tumoral patent vessels (Spearman rank

correlation coefficient, r=0.486; P<0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we identified three clinically

significant findings. First, higher TBF before treatment was

associated with better therapeutic efficacy of mFOLFIRINOX, whereas

pre-treatment TBF did not influence outcomes in patients receiving

GnP or GS. Second, in cases with low pre-treatment TBF, TBF

improved after treatment with GnP, yet remained unchanged in

patients treated with mFOLFIRINOX or GS. Finally, the TBF was

positively correlated with the number of intra-tumoral patent

vessels. Recently, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has become the standard

therapeutic option for PDAC in recent years (3–7).

However, the optimal pre-operative therapeutic regimen remains

unclear. Considering the heterogeneous nature of the pancreatic

tumor microenvironment (2),

personalizing chemotherapy based on individual tumor

characteristics may improve clinical outcomes. Our findings suggest

that TBF may serve as a useful indicator for selecting an

appropriate chemotherapy regimen for PDAC.

First, we found that patients with higher

pretreatment TBF showed better pathological responses to

mFOLFIRINOX. Previous study has reported that therapeutic

responders showed significantly higher TBF when assessed using

perfusion computed tomography, which allows accurate evaluation of

TBF (14). The findings of our

study are consistent with these results, supporting the notion that

higher TBF is associated with a better response to therapy in PDAC.

Although our study evaluated TBF using conventional

contrast-enhanced CT, which is considered less accurate than

perfusion CT for assessing TBF, we obtained similar findings.

Importantly, conventional contrast-enhanced CT is more widely

available and routinely performed in clinical practice compared

with perfusion CT, which highlights the potential clinical

applicability of our results. Furthermore, prior study did not

perform analyses according to treatment regimen, and their cohorts

included patients treated with both gemcitabine- and 5-fluorouracil

(5-Fu)-based therapies. In contrast, our study demonstrated the

relationship between TBF and preoperative therapy according to each

regimen, which may provide new information for guiding the

selection of personalized optimal therapy for patients with PDAC.

Nevertheless, both previous report and our study are limited by

relatively small sample sizes, and further large-scale

investigations are needed to validate these findings and to clarify

the role of TBF in treatment stratification. One of the hallmark

pathological features of PDAC is the dense desmoplastic stroma

surrounding tumor cells (2,11), which increases intra-tumoral

pressure, compresses blood vessels, and reduces perfusion. This, in

turn, impairs drug delivery to tumor (12). Previous studies have also reported a

relationship between stromal density and TBF (18), supporting the notion that tumors

with high TBF levels may permit more effective drug delivery,

leading to improved therapeutic outcomes.

Conversely, no correlation was observed between

pre-treatment TBF and therapeutic response in patients receiving

GnP or GS. This led us to hypothesize that changes in TBF during

treatment may contribute to therapeutic response. Indeed, when we

compared TBF before and after treatment, we observed that TBF

improved in GnP-treated patients with an initially low TBF, but

remained unchanged in those treated with mFOLFIRINOX or GS. These

results suggest that GnP may improve tumor perfusion during

treatment, potentially enhancing drug delivery and efficacy, even

in poorly perfused tumors. The previous study showed GnP reduce

fibrillar collagen matrix (19).

Thus, GnP may reduce intra-tumoral pressure and compresses blood

vessels, subsequently improve tumor perfusion. On the other hand,

in the nude mice gastric cancer model, conventional dose of 5-Fu

and prodrug of 5-Fu did not reduce cancer-associated fibroblast

(20). Thus, mFOLFIRINOX and GS may

not improve tumor perfusion. Therefore, mFOLFIRINOX may be more

suitable for tumors with a high pre-treatment TBF, whereas GnP may

be preferable for tumors with a low pre-treatment TBF. As for GS,

there were differences in clinical background compared to

mFOLFIRINOX or GnP group, such as shorter treatment duration and a

greater number of patients with low pre-treatment CA19-9 levels.

However, it was difficult to describe the reason behind the lack of

correlation between TBF and treatment efficacy in GS group only

from these factors. In the previous report, molecular and cellular

alterations in PDAC were shown to occur during treatment,

suggesting that a single time-point analysis of tumor

characteristics may be insufficient (13). To achieve personalized treatment, it

may be important to repeatedly assess molecular and cellular

information and intervene promptly in accordance with tumor

evolution. Therefore, future investigations are warranted.

Additionally, we investigated the association

between TBF and intra-tumoral vessels using CD31 immunostaining.

Although TBF did not correlate with the area of the intra-tumoral

vessels, a higher TBF was associated with a greater number of

intra-tumoral patent vessels. Generally, PDAC are characterized by

dense desmoplastic stroma (2,11).

Therefore, both patent and occlusive vessels were observed in these

tumors. However, a previous report evaluated only the area of

intra-tumoral vessels (18). Our

study was the first, to the best of our knowledge, to evaluate

patent intra-tumoral vessels. In GnP-treated patients, TBF improved

post-treatment, suggesting dynamic changes in intra-tumoral

vascular patency. The predictive value of TBF for chemotherapeutic

response is likely due to its effect on the efficiency of

intra-tumoral drug delivery.

This study had several limitations. First, this was

a retrospective analysis with a limited small sample size. Second,

variations in neoadjuvant treatment duration among patients could

not be controlled. Third, owing to the lack of pre-treatment

specimens, we were unable to directly evaluate the correlation

between pre-treatment TBF and pathological features. Because all

tissue analyses were performed on post-treatment specimens,

treatment-induced changes could not be ruled out. Nonetheless, we

believe that the correlations observed between post-treatment TBF

and pathological features are biologically plausible. Future in

vivo studies are warranted to investigate these associations

under controlled conditions.

In conclusion, we demonstrated an association

between TBF and the therapeutic response to each chemotherapy

regimen for PDAC. Furthermore, we observed that the changes in TBF

during treatment varied depending on the chemotherapy regimen.

These findings suggest that TBF may serve as a useful biomarker for

guiding the selection of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for PDAC.

However, larger prospective studies are needed to validate these

results.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HMa, TMa, YT, HMo, NN, TS, RO, ST, KT, MK, SK, TMi

and MT contributed to the study conception and design. HMa

performed data analysis and interpretation. HMa and TMa assessed

the immunostaining. HMa and YT evaluated tumor blood flow using

computed tomography. HMo, NN, TMa and TS sectioned the pathological

tissue blocks, prepared the slides and performed the

immunostaining. HMo, NN, TMa, TS, RO, ST, KT, MK, SK, TMi and MT

performed surgery and postoperative management. The first draft of

the manuscript was written by HMa, and TMa, YT, HMo, NN, TMa, TS,

RO, ST, KT, MK, SK, TMi and MT commented on previous versions of

the manuscript. HMa, TMa and MT confirmed the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shiga University of Medical Science (approval no.

R2017-171; Otsu, Japan) and was conducted in accordance with the

principles outlined in The Declaration of Helsinki. Informed

consent was obtained from all the patients or their legal

representatives on an opt-out basis.

Patient consent for publication

Consent for publication of the study was obtained

via the opt-out approach.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Maehira H, Miyake T, Iida H, Tokuda A,

Mori H, Yasukawa D, Mukaisho KI, Shimizu T and Tani M: Vimentin

expression in tumor microenvironment predicts survival in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: heterogeneity in fibroblast

population. Ann Surg Oncol. 26:4791–4804. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Andriulli A, Festa V, Botteri E, Valvano

MR, Koch M, Bassi C, Maisonneuve P and Sebastiano PD:

Neoadjuvant/preoperative gemcitabine for patients with localized

pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann Surg

Oncol. 19:1644–1662. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kato H, Usui M, Isaji S, Nagakawa T, Wada

K, Unno M, Nakao A, Miyakawa S and Ohta T: Clinical features and

treatment outcome of borderline resectable pancreatic head/body

cancer: A multi-institutional survey by the Japanese society of

pancreatic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 20:601–610. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

D'Angelo F, Antolino L, Farcomeni A,

Sirimarco D, Kazemi Nava A, De Siena M, Petrucciani N, Nigri G,

Valabrega S, Aurello P and Ramacciato G: Neoadjuvant treatment in

pancreatic cancer: Evidence-based medicine? A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Med Oncol. 34:852017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Satoi S, Yamaue H, Kato K, Takahashi S,

Hirono S, Takeda S, Eguchi H, Sho M, Wada K, Shinchi H, et al: Role

of adjuvant surgery for patients with initially unresectable

pancreatic cancer with a long-term favorable response to

non-surgical anti-cancer treatments: Results of a project study for

pancreatic surgery by the Japanese society of

hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci.

20:590–600. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Motoi F, Satoi S, Honda G, Wada K, Shinchi

H, Matsumoto I, Sho M, Tsuchida A and Unno M; Study Group of

Preoperative therapy for Pancreatic cancer (PREP), : A single-arm,

phase II trial of neoadjuvant gemcitabine and S1 in patients with

resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma:

PREP-01 study. J Gastroenterol. 54:194–203. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Unno M, Motoi F, Matsuyama Y, Satoi S,

Toyama H, Matsumoto I, Aosasa S, Shirakawa H, Wada K, Fujii T, et

al: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 versus

upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer: Results of the

randomized phase II/III Prep-02/JSAP05 trial. Ann Surg. April

16–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Li D, Xie K, Wolff R and Abbruzzese JL:

Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 363:1049–1057. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Maehira H, Tsuji Y, Iida H, Mori H, Nitta

N, Maekawa T, Kaida S, Miyake T and Tani M: Estimated tumor blood

flow as a predictive imaging indicator of therapeutic response in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Use of three-phase

contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Int J Clin Oncol.

27:373–382. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook

N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM and

Tuveson DA: Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut.

60:861–868. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Neesse A, Bauer CA, Öhlund D, Lauth M,

Buchholz M, Michl P, Tuveson DA and Gress TM: Stromal biology and

therapy in pancreatic cancer: Ready for clinical translation? Gut.

68:159–171. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wolff RA, Wang-Gillam A, Alvarez H, Tiriac

H, Engle D, Hou S, Groff AF, San Lucas A, Bernard V, Allenson K, et

al: Dynamic changes during the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Oncotarget. 9:14764–14790. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hamdy A, Ichikawa Y, Toyomasu Y, Nagata M,

Nagasawa N, Nomoto Y, Sami H and Sakuma H: Perfusion CT to assess

response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Initial experience. Radiology.

292:628–635. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Miles KA: Measurement of tissue perfusion

by dynamic computed tomography. Br J Radiol. 64:409–412. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ishida M, Fujii T, Kishiwada M, Shibuya K,

Satoi S, Ueno M, Nakata K, Takano S, Uchida K, Ohike N, et al:

Japanese classification of pancreatic carcinoma by the Japan

pancreas society: Eight edition. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci.

31:755–768. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Koyasu S, Tsuji Y, Harada H, Nakamoto Y,

Nobashi T, Kimura H, Sano K, Koizumi K, Hamaji M and Togashi K:

Evaluation of tumor associated stroma and its relationship with

tumor hypoxia using dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and (18)F

misonidazole PET in murine tumor models. Radiology. 278:734–741.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Alvarez R, Musteanu M, Garcia-Garcia E,

Lopez-Casas PP, Megias D, Guerra C, Muñoz M, Quijano Y, Cubillo A,

Rodriguez-Pascual J, et al: Stromal disrupting effects of

nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 109:926–933.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang C, Xi W, Jiang J, Ji J, Yu Y, Zhu Z

and Zhang J: Metronomic chemotherapy remodel cancer-associated

fibroblasts to decrease chemoresistance of gastric cancer in nude

mice. Oncol Lett. 14:7903–7909. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|