Introduction

Skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) is a highly

aggressive malignancy originating from melanocytes, with increasing

global incidence and poor prognosis despite recent advances in

immunotherapy and targeted therapy (1). In 2020, >320,000 new cases of SKCM

were diagnosed worldwide, with nearly 57,000 related deaths

(2). SKCM is primarily associated

with exposure to ultraviolet radiation, whether from natural

sunlight or indoor tanning practices (3). The management of SKCM involves various

therapeutic approaches, such as surgery, radiotherapy, targeted

therapy and immunotherapy, with the choice of treatment determined

according to the disease stage (4).

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized

treatment paradigms in advanced SKCM, notable inter-patient

heterogeneity leads to variable therapeutic responses, underscoring

the need for novel biomarkers to guide personalized therapy.

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a fundamental

biological process involved in tumor progression, immune evasion

and therapeutic resistance (5).

Various PCD modes, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis,

necroptosis, autophagy and the newly defined cuproptosis, have been

shown to influence cancer immunity and treatment outcomes (6). Increasing evidence indicates that

PCD-related genes (PRGs) serve multifaceted roles in modulating the

tumor microenvironment (TME) and shaping antitumor immunity

(7). For example, high expression

of ferroptosis regulators has been associated with immune cell

infiltration and response to ICIs in several cancer types (8,9). In

lung adenocarcinoma, a machine learning-derived PCD signature was

shown to associate with prognosis, immune infiltration levels and

immunotherapy sensitivity (10,11). A

PCD signature could also serve as a prognostic biomarker for

ovarian cancer (12), bladder

cancer (13) and hepatocellular

carcinoma (14). However, the

clinical relevance and prognostic value of PCD-related gene

expression in SKCM, particularly in the context of immunotherapy,

have not been fully elucidated.

With the advancement of high-throughput sequencing

and computational methods, machine learning has emerged as a

powerful tool for integrating multi-dimensional genomic data to

uncover clinically relevant biomarkers. Compared with traditional

statistical approaches, machine learning algorithms such as Lasso,

CoxBoost, survivalSVM and random survival forest offer greater

flexibility and accuracy in modeling complex gene-phenotype

relationships and building predictive models with high

generalizability (15,16).

In the present study, a novel PCD-related index

(PCDI) was developed for SKCM using integrative machine learning

strategies. The predictive efficacy of the PCDI was systematically

evaluated in terms of prognosis and response to immunotherapy,

providing a potential tool for precision oncology in patients with

SKCM.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and

pre-processing

Transcriptomic and clinical data of patients with

SKCM were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; TCGA-SKCM

dataset; n=425) database on November 10, 2023. Three independent

validation cohorts were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database, namely,

GSE54467 (n=79) (17), GSE59455

(n=122) (18) and GSE65904 (n=210)

(19). Three immunotherapy datasets

[GSE91061 (20), GSE78220 (21) and IMvigor210 (22)] were used to assess the predictive

value of PCDI in treatment response.

A total of 15 types of PCD patterns (for example,

apoptosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis and autophagy) were

included and PCD-related genes were curated from Molecular

Signatures Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp),

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (https://www.kegg.jp/), GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and a recent study

(13) (Table SI). Differential expression

analysis (|log fold change| ≥1.5 and adjusted P<0.05) between

tumor and normal samples was conducted using the ‘limma’ R package

(version 3.64.3) (23) and

prognostic genes were screened using univariate Cox regression

analysis (P<0.05).

Construction of the PCDI

The present study employed an integrative machine

learning pipeline comprising 10 algorithms (Lasso, Ridge, CoxBoost,

random survival forest, survival-support vector machines, efficient

neural network, partial least squares regression for Cox, super

partial correlation, stepwise Cox and gradient boosting machine) to

develop and evaluate 77 model combinations. The present study

developed the PCDI in four steps following the methods of a

previous study (24): i) Univariate

Cox regression was used to investigate prognostic biomarkers

(TCGA); ii) a total of 77 algorithm combinations were then fitted

to the prediction model (TCGA); iii) all algorithm combinations

were carried out in GEO cohorts; and iv) the concordance (C)-index

was computed for each cohort. Detailed parameters of the 10 machine

learning algorithms are described in Data S1. The model with the highest

average C-index across TCGA and GEO cohorts was selected as the

optimal PCDI. Patients were stratified into high- and low-PCDI

(risk score) groups (cut-off value: 0.135) using the

‘surv_cutpoint’ function of the ‘survminer’ R package. Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis with log-rank test and time-dependent receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to assess the

prognostic capability of PCDI. The clinical outcome of patients

with SKCM was analyzed through both univariate and multivariate Cox

regression models to identify potential risk factors associated

with the disease. Based on PCDI score and additional clinical

features (age, sex, TNM stage, T stage, N stage and M stage), the

‘nomogramEx’ program (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nomogramEx/index.html)

was used to construct a predicting nomogram.

Evaluation of immunotherapeutic

value

Immune infiltration was evaluated using the

‘immunedeconv’ R package (version 1.0) (25), integrating CIBERSORT, TIMER and

other tools. Tumor microenvironment components (immune, stromal and

ESTIMATE scores) were assessed via the ‘estimate’ package (version

4.4.0) (26). To predict

immunotherapy response, the present study analyzed the tumor

mutation burden (TMB) (27), tumor

immune dysfunction and exclusion (TIDE) score (28), and immunophenoscore (29), as well as immune escape score

calculated with an immune escape gene set (CD47, ADAM10, HLA-G,

CD274, FASLG, CCL5, TGFB1, IL10, PTGER4) from a previous study

(30). TMB is an emerging biomarker

of sensitivity to ICIs and has been shown to be associated with

response to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade immunotherapy (26). TIDE is a computational tool used to

evaluate tumor immune escape mechanisms and predict the response to

ICI treatment. The immunophenoscore is a notable predictor of

response to anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

(CTLA-4) and anti-PD-1 therapy. The immune escape score is an

indicator used to evaluate the ability of tumor cells to evade

immune system surveillance and killing. The predictive value of

PCDI was further validated in three independent immunotherapy

cohorts (GSE91061, GSE78220 and IMvigor210). Gene set enrichment

analysis (GSEA) and single sample GSEA (ssGSEA) were conducted to

explore pathway differences between high and low PCDI groups.

Subsequently, the ‘oncoPredict’ R package (version 1.2) (31) was employed to estimate the

IC50 values of therapeutic agents for SKCM cases,

utilizing data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/).

Human Protein Atlas (HPA)

database

The HPA database (http://www.proteinatlas.org) utilizes transcriptomic

and proteomic technologies to explore protein expression at the RNA

and protein levels in different human tissue types and organs. The

HPA database is a convenient way to explore the expression levels

of stratifin (SFN), which had the highest positive coefficient in

the formula for calculating PCDI score, in normal and tumor tissue.

Representative immunohistochemical images of SFN staining in normal

and SKCM tissues were obtained from the ‘Tissue’ and ‘Cancer’

sections of the HPA.

Cell culture

Melanoma cell lines (A375, A2058, MV3, Sk-mel-1 and

Sk-mel-28) and a normal skin-derived cell line (PIG1) were obtained

from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese

Academy of Sciences. These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

enriched with 10% FBS (Procell Life Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) and 1% antibiotic solution (Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). Cells were maintained at 37°C in an

atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

To achieve SFN gene silencing, the melanoma A375 and

A2058 cell lines were separately transfected with si-SFN (cat. no.

siG000002810A-1-5; sequence 5′-GCAATTAGTATTGTTTGAAACAT-3′) or

si-negative control (cat. no. siN0000001-4-10; sequence

5′-GCAGGATGGGATAAGTCTAAA-3′) sequences provided by Guangzhou

RiboBio Co., Ltd. A total of 0.5 nmol siRNA was used for

transfection each time using Lipofectamine® 3000 (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A375 and A2058 cells were transfected

with siRNA at 37°C for 48 h before further experiments were

performed.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the aforementioned

cells (A375, A2058, MV3, Sk-mel-1, Sk-mel-28 and PIG-1) using

Triquick® Reagent (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). According to the manufacturer's protocol,

complementary DNA (cDNA) for SFN was synthesized from the isolated

RNA employing the SweScript RT I FTTSt Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit

(cat. no. G3330-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The

resulting cDNA was then used as a template for qPCR analysis

performed on a PCR system using 2X SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Low

ROX) (cat. no. G3321-05; Selleck China). The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min;

followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 70°C

for 30 sec. Gene expression levels were quantified using the

2−ΔΔCq method and normalized to GAPDH expression

(32). Primer sequences used were

as follows: GAPDH forward (F), 5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′ and

GAPDH reverse (R), 5′-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3′; and SFN F,

5′-TCCACTACGAGATCGCCAACAG-3′ and SFN R,

5′-GTGTCAGGTTGTCTCGCAGCA-3′.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

To evaluate cell viability, transduced A375 and

A2058 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and allowed to grow for

24, 48 or 72 h. After incubation, CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. G1613-1ML

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to each well,

followed by a 4-h incubation at 37°C. Absorbance values were

measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R

software (version 4.2.1; R Development Core Team). Differences

between continuous variables were assessed using either the

Wilcoxon rank-sum test or unpaired Student's t-test, depending on

data distribution. Pearson's correlation coefficients were

calculated to evaluate associations between two continuous

parameters. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using the

two-sided log-rank test Univariate and multivariate Cox regression

analyses were performed to identify risk factors for the overall

survival of patients with SKCM. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. All assays were

repeated three times.

Results

Identification of prognostic PRGs in

SKCM

To explore the prognostic value of PRGs in SKCM, the

present study first identified differentially expressed genes

(DEGs) between tumor and normal tissues from the TCGA-SKCM cohort.

A total of 1,638 genes were found to be significantly dysregulated

(|log2FC|>1.5; P<0.05) (Fig. S1A). By intersecting these DEGs with

a curated set of 1,254 PRGs, the present study obtained 117

differentially expressed PRGs (Fig.

S1B). Among them, univariate Cox regression identified 54 PRGs

that were significantly associated with overall survival (OS) in

patients with SKCM (Fig. S1C),

suggesting their potential utility for constructing a prognostic

model.

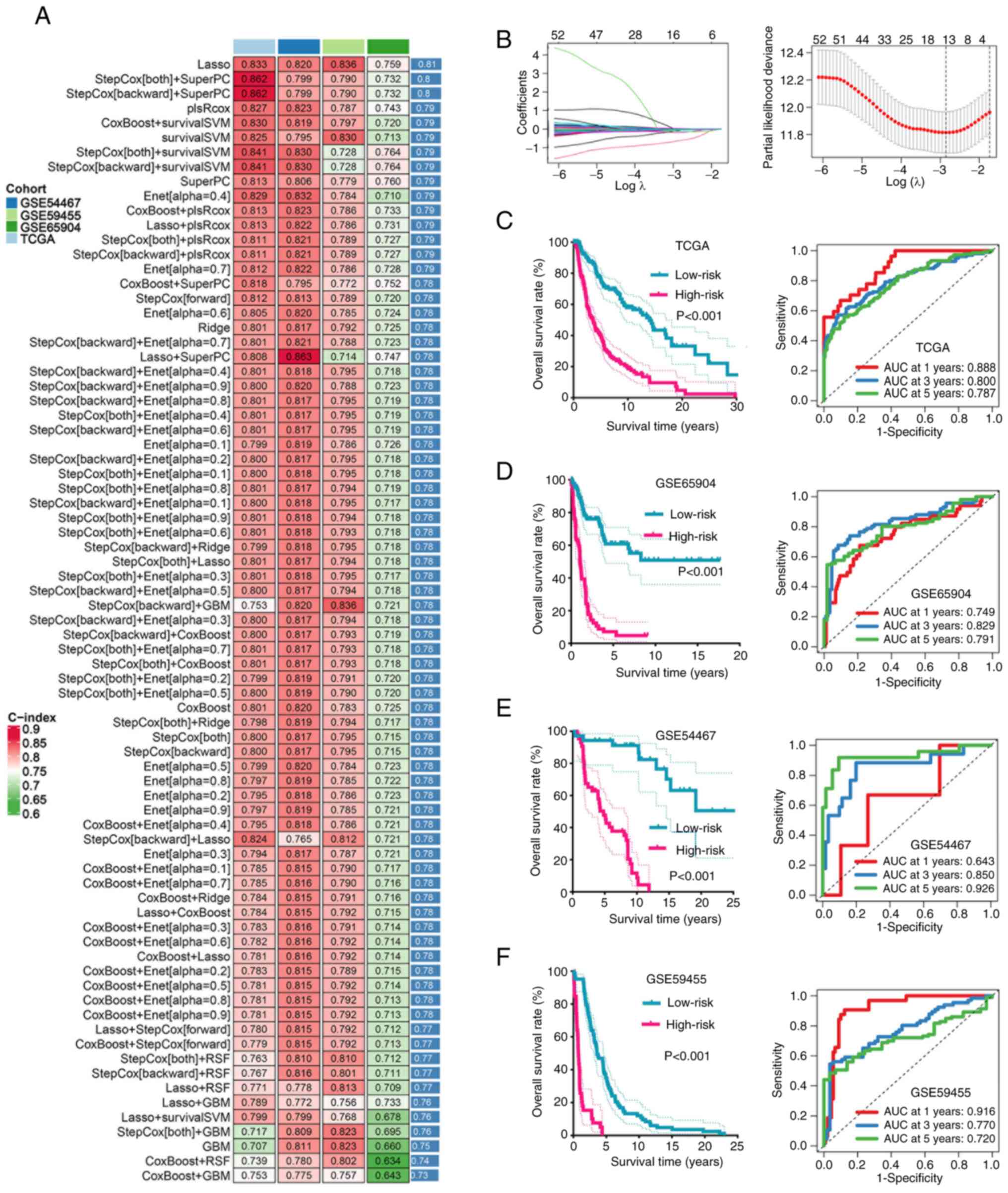

Integrative machine learning-based

PCDI

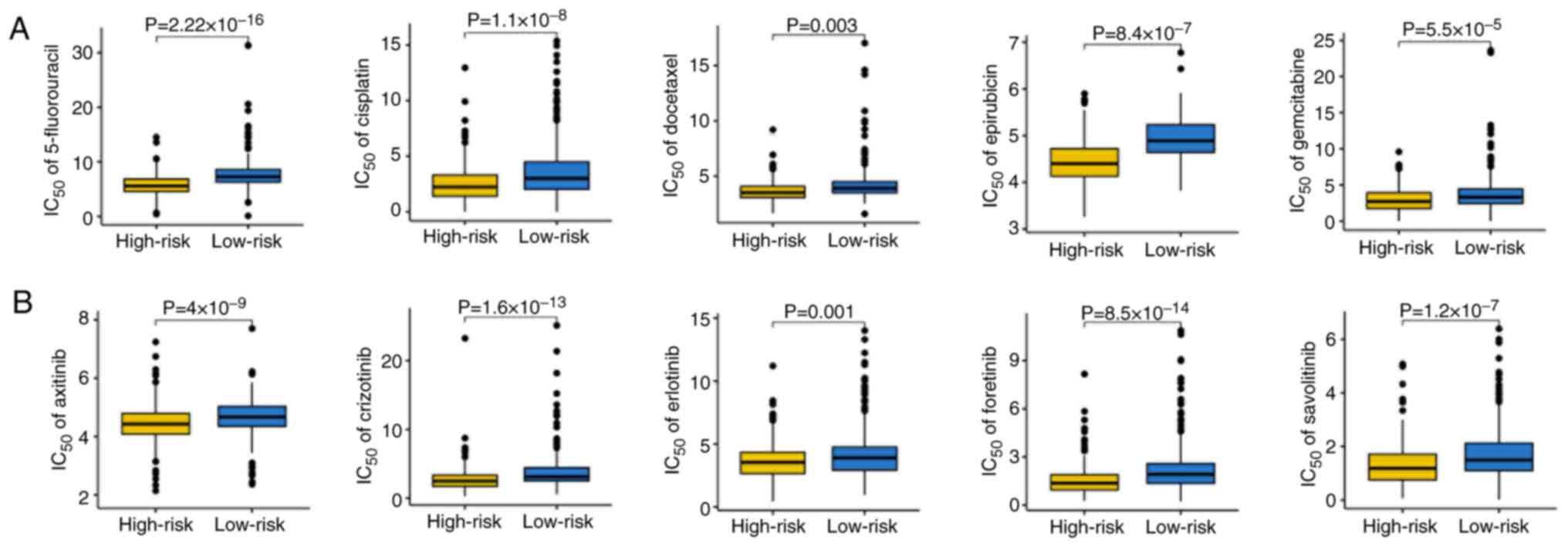

Using the 54 prognosis-associated PRGs, the present

study applied a machine learning integration strategy involving 77

algorithm combinations across TCGA and GEO datasets. Based on the

average C-index across training and validation cohorts, the Lasso

algorithm was identified as the optimal method, achieving the

highest predictive performance (Fig.

1A). The optimal λ parameter was selected when the partial

likelihood deviance reached its minimum in cross-validation and 13

PRGs were retained to construct the PCDI (Fig. 1B). The risk score for each patient

was calculated as: Risk score=(0.029 × SFNexp) + (−0.176

× IDSexp) + (−0.054 × SCFD1exp) + (−0.591 ×

TRIM34exp) + (−0.011 × CD74exp) + (−0.023 ×

FBXW7exp) + (−0.045 × CRIP1exp) + (−0.133 ×

IFNAR2exp) + (−0.051 × PIM2exp) + (−0.053 ×

CTSWexp) + (−0.008 × NUPR1exp) + (−0.029 ×

ICAM1exp) + (−0.024 × AIM2exp).

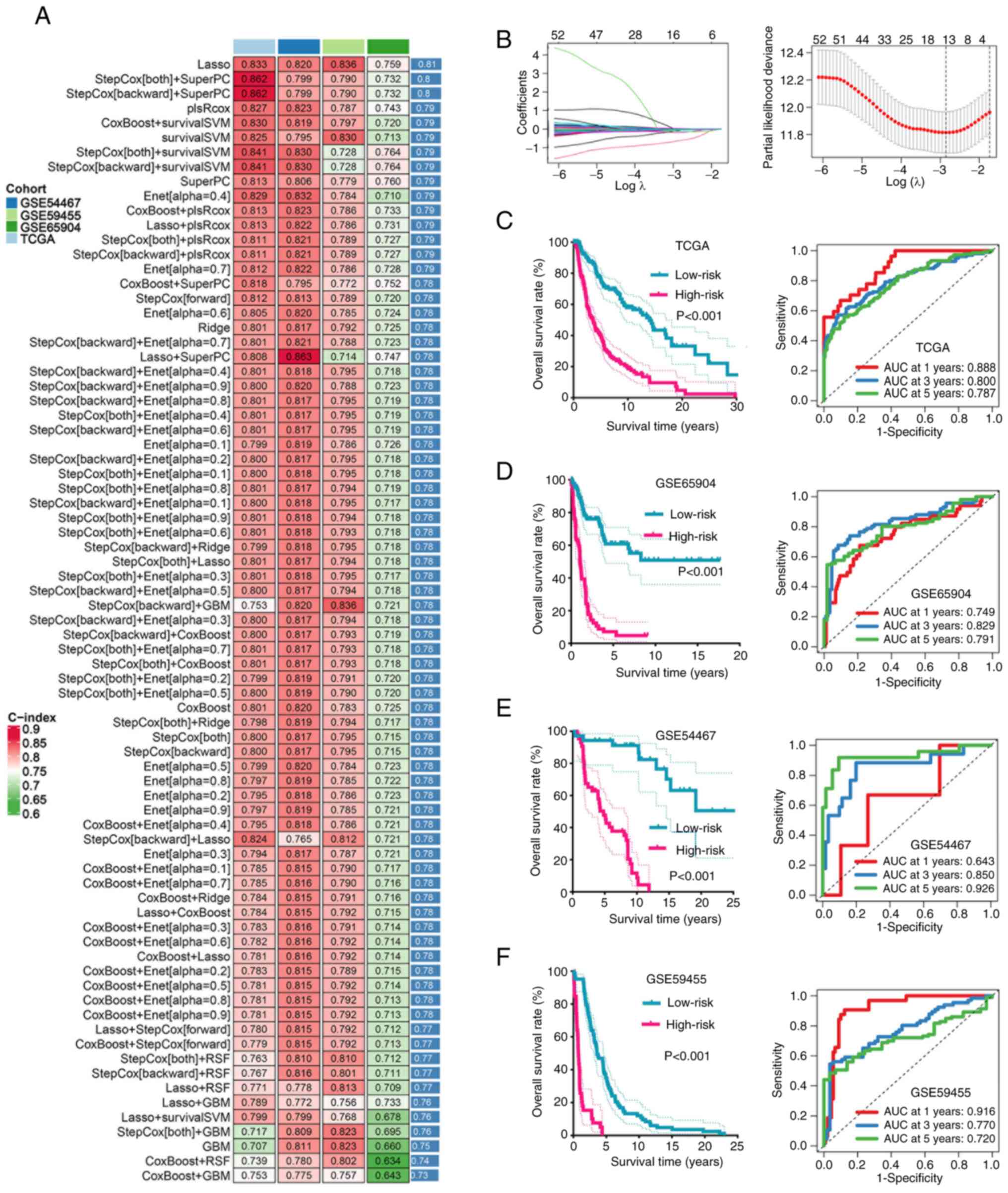

| Figure 1.Machine learning developed programmed

cell death-related signature. (A) The C-index of 77 types of

prognostic models of TCGA and GEO cohorts. (B) Determination of the

optimal λ was obtained when the partial likelihood deviance reached

the minimum value in the TCGA cohort and further generated Lasso

coefficients of the most useful prognostic genes. The survival

curve and their corresponding ROC curve in SKCM with different risk

score in (C) TCGA, (D) GSE65904, (E) GSE54467 and (F) GSE59455

dataset. C-index, concordance index; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GSE, gene expression data series;

SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; RSF, random survival forest;

survivalSVM, survival-support vector machines; Enet, efficient

neural network; plsRCox, partial least squares regression for Cox;

SuperPC, super partial correlation; GBM, gradient boosting machine;

AUC, area under the curve. |

Patients in the TCGA, GSE65904, GSE54467 and

GSE59455 cohorts were stratified into high- and low-risk groups

based on the optimal cut-off (0.1365). Kaplan-Meier survival

analyses demonstrated that patients in the high-risk group

consistently exhibited worse OS compared with that of the low-risk

group across all datasets (Fig.

1C-F). Time-dependent ROC analyses further confirmed the

predictive robustness of the model, with 1-, 3- and 5-year AUCs

>0.70 in the majority of cohorts. The AUC of the 1-, 3- and

5-year ROC curve was 0.888, 0.800 and 0.787 in the TCGA cohort

(Fig. 1C), 0.749, 0.829 and 0.791

in the GSE65904 cohort (Fig. 1D),

0.643, 0.850 and 0.926 in the GSE54467 cohort (Fig. 1E), and 0.916, 0.770 and 0.720 in the

GSE59455 cohort (Fig. 1F),

respectively.

Evaluation of the performance of

PCDI

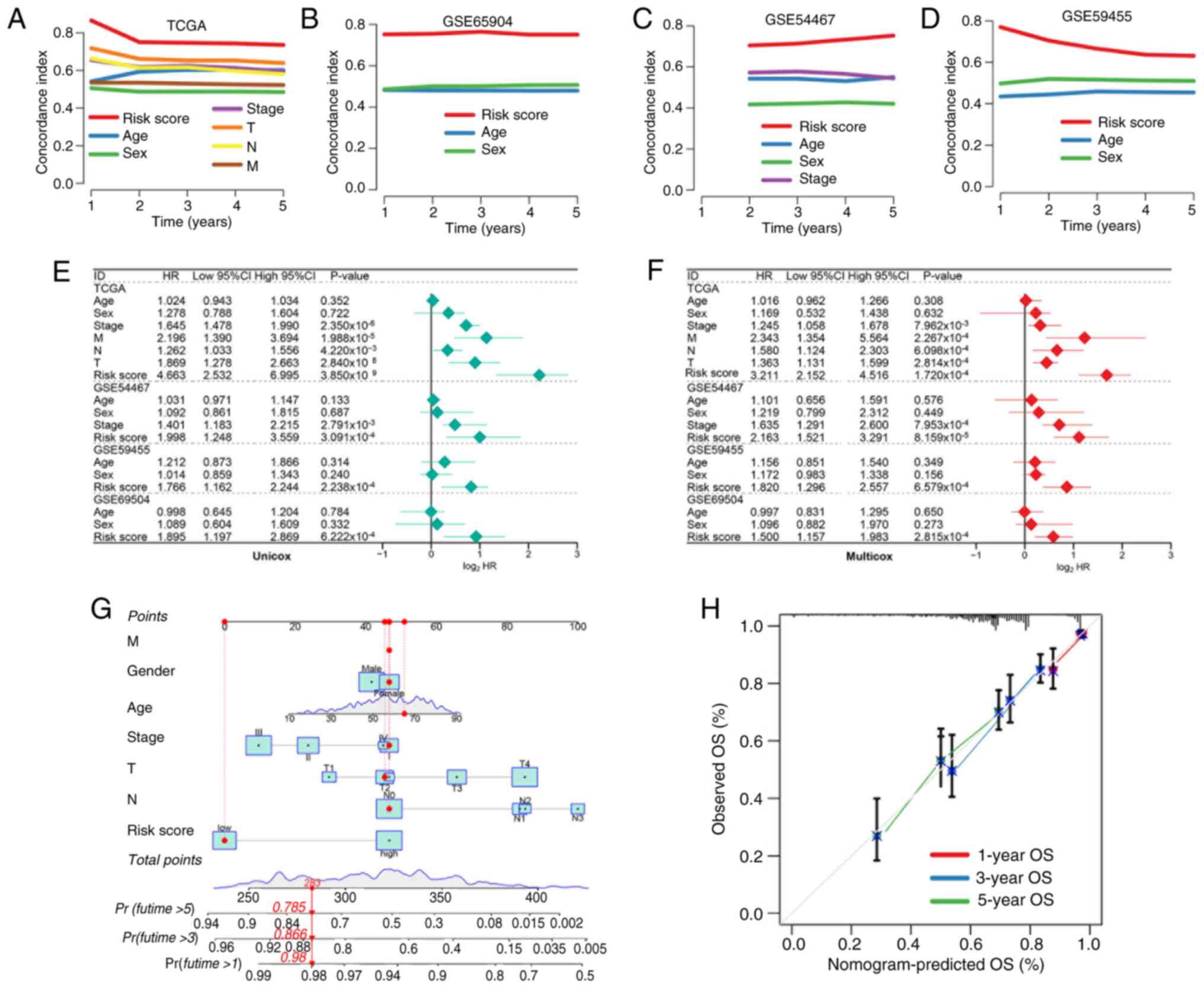

To further assess the clinical utility of the risk

signature, the present study compared its predictive accuracy

against standard clinical parameters. C-index analysis revealed

that the risk score consistently outperformed age, sex and TNM

stage in all cohorts (33)

(Fig. 2A-D). Univariate and

multivariate Cox regression analyses confirmed that the risk score

was an independent predictor of OS in SKCM (Fig. 2E and F). A prognostic nomogram

integrating the risk score and clinical features (for example, pT

and pN stage) was constructed (Fig.

2G) and calibration plots demonstrated notable agreement

between predicted and observed survival probabilities (Fig. 2H).

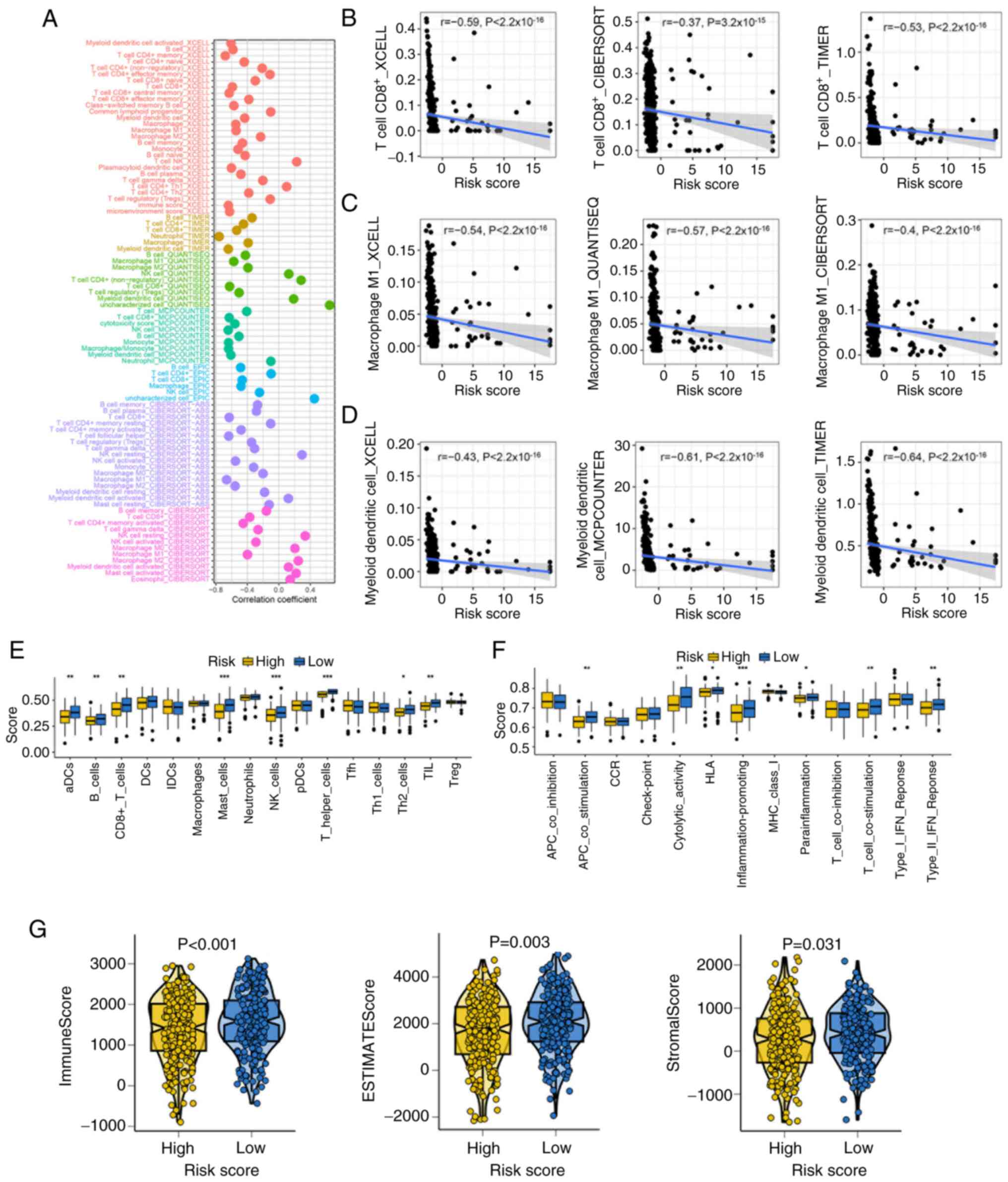

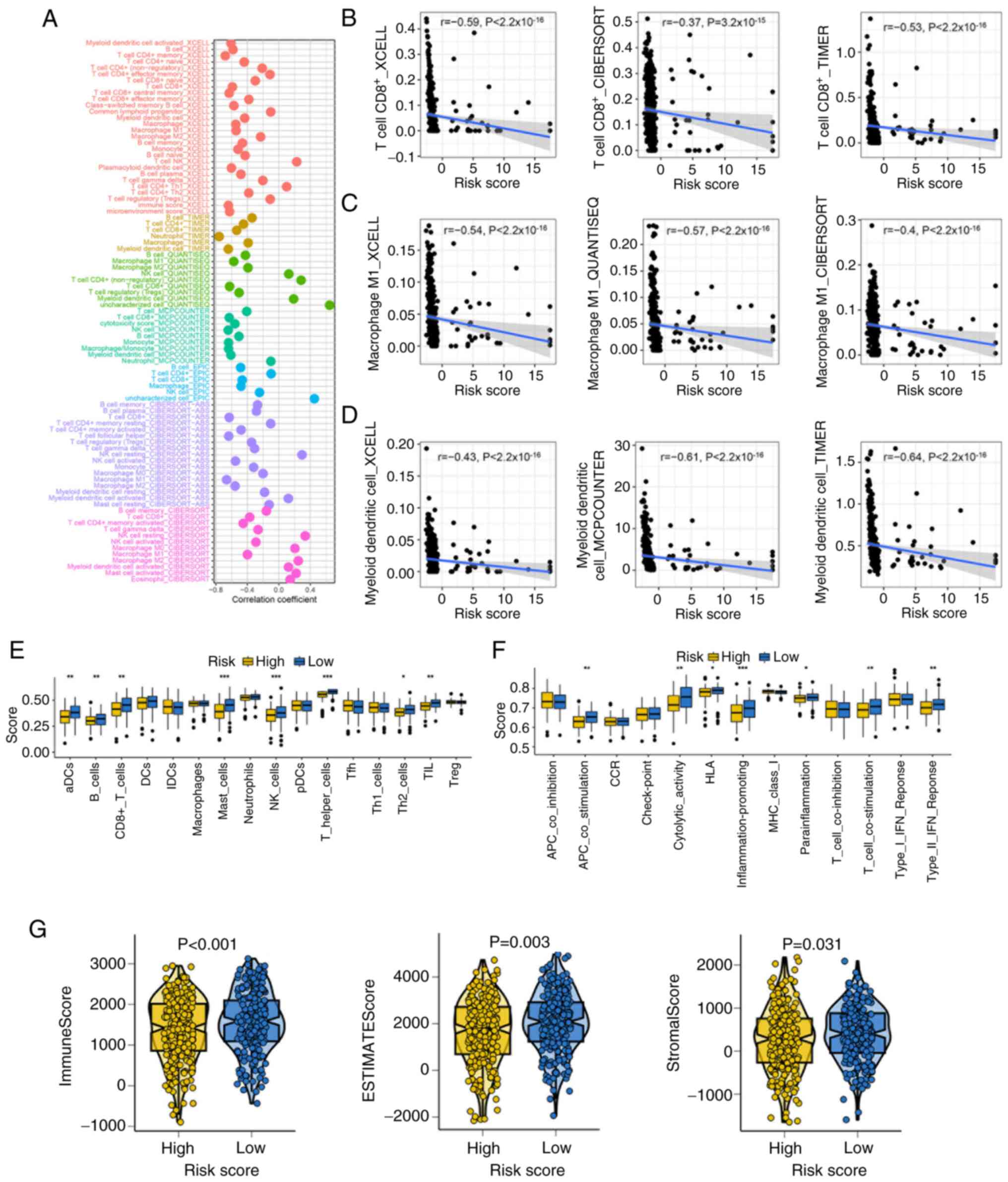

Immune landscape in high- and low-risk

groups

Due to the known association between PCD and immune

modulation, the present study investigated the immune infiltration

profiles of patients with SKCM with different risk scores. Multiple

deconvolution algorithms revealed significant negative correlations

between the risk score and immune cell abundance (Fig. 3A). Particularly, CD8+ T

cells, M1 macrophages and dendritic cells were significantly

negatively correlated with risk score in SKCM (Fig. 3B-D). ssGSEA analysis further

indicated lower immune cells and immune function scores, including

aDCs, B cells, CD8+ T cells, mast cells, NK cells, TILs,

T helper (Th) cells, Th2 cells, APC_co_stimulation, cytolytic

activity, inflammation promoting and T cell co-stimulation, human

leukocyte antigen (HLA), parainflammation and type II IFN response

in the high-risk group (Fig. 3E and

F). Patients with low-risk score also exhibited significantly

higher stromal, immune and ESTIMATE scores, which suggested a more

active tumor immune microenvironment (Fig. 3G).

| Figure 3.Landscape of the immune infiltration

among various risk score groups. (A) Correlation between risk score

and immune cell abundance, determined using seven algorithms. The

correlation between the risk score and the number of (B)

CD8+ T cells, (C) M1 macrophages and (D) dendritic

cells. ssGSEA study assessing (E) immune cell and (F)

immune-related function levels across several risk score

categories. (G) The stromal, immune and ESTIMATE scores across

various risk score categories. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. ssGSEA, single sample gene set enrichment analysis;

aDCs, antibody-drug conjugates; DCs, dendritic cells; NK, natural

killer; Tfh, T follicular helper cells; Th, T helper cells; TIL,

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; Treg, regulatory T cells; APC,

antigen presenting cells; CCR, chemokine receptor; MHC, major

histocompatibility complex; iDCs, immature dendritic cells; pDCs,

plasmacytoid dendritic cells. |

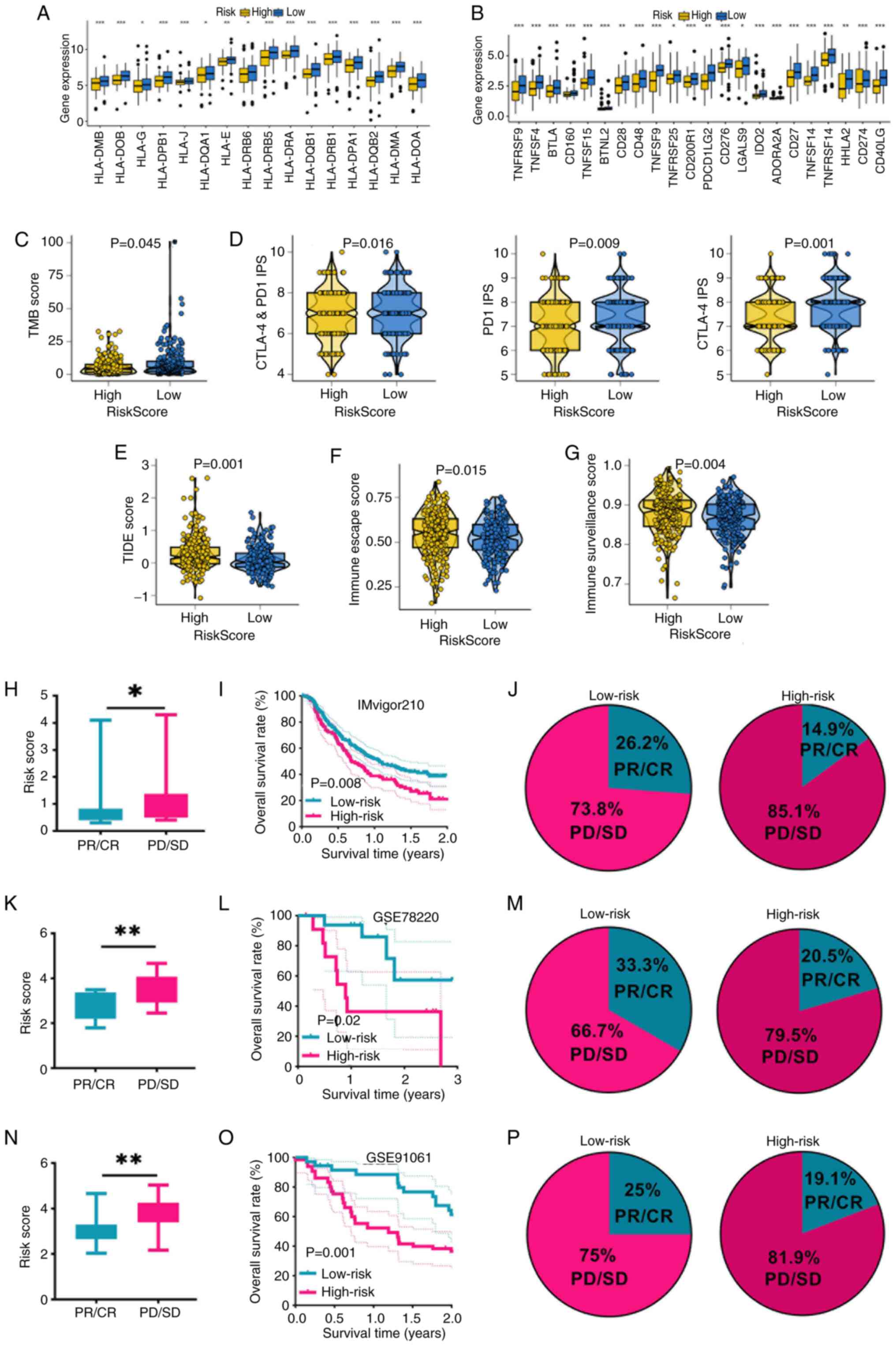

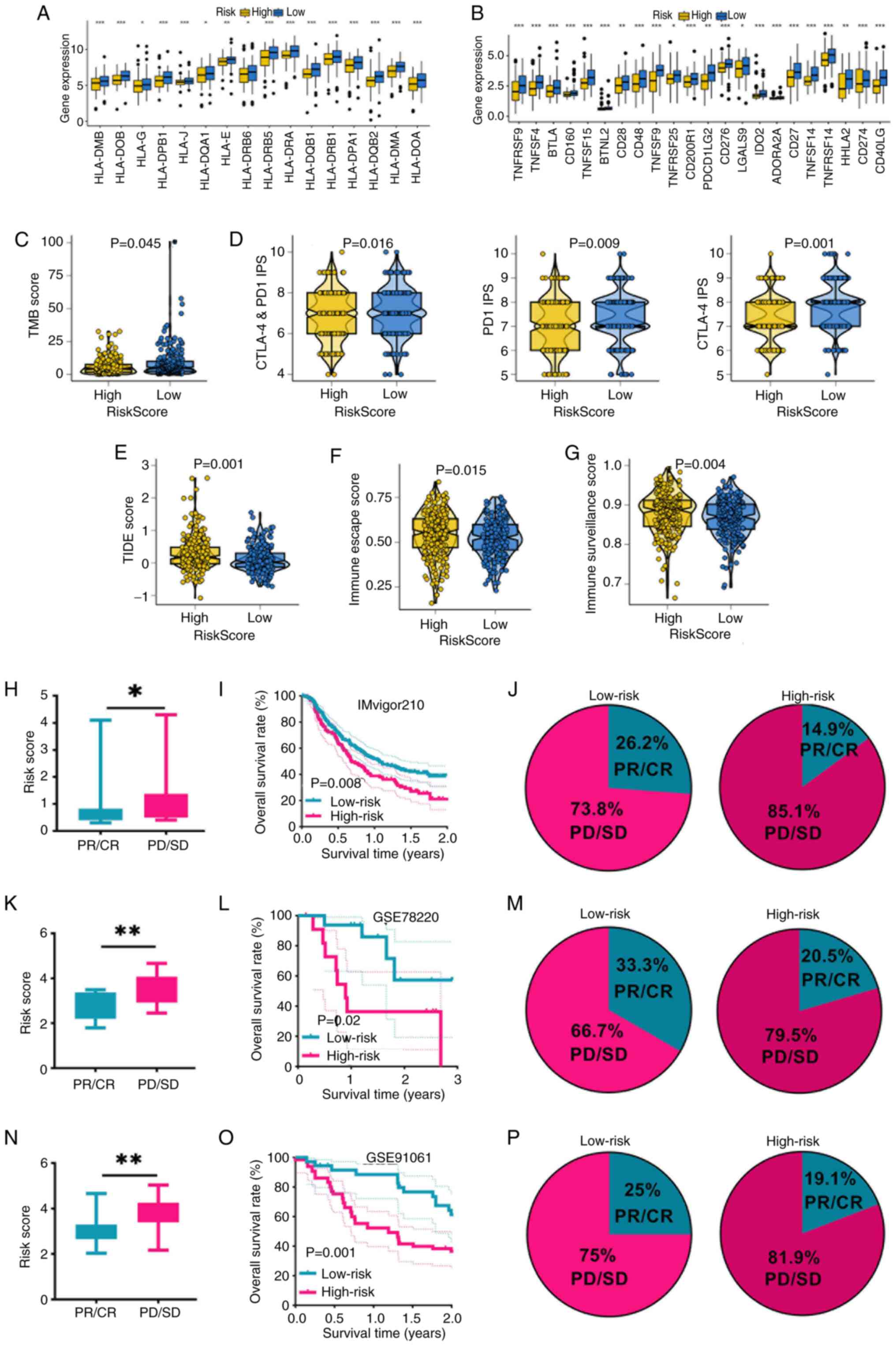

Association between risk score and

immunotherapy response

To evaluate the predictive value of the risk

signature in immunotherapy response, the present study examined

multiple immune-related features. Patients with SKCM with low-risk

score had significantly higher expression of HLA-related genes and

immune checkpoint molecules compared with patients with SKCM and a

high-risk score (Fig. 4A and B).

Elevated expression levels of HLA-related genes predicted a higher

chance of immunotherapy benefits (34). Furthermore, they demonstrated

increased TMB score and PD-1/CTLA4 immunophenoscores, suggesting

enhanced tumor immunogenicity (Fig. 4C

and D). A marked response to immunotherapy is indicated by low

TIDE and immune escape scores (28,35).

In the present study, low-risk score patients with SKCM had lower

TIDE, immune escape and immune surveillance scores, indicating a

more favorable immunotherapy profile (Fig. 4E-G). These findings were further

validated in three independent melanoma immunotherapy cohorts. In

the IMvigor210, GSE78220 and GSE91061 datasets, the risk score of

non-responders in SKCM was notably greater compared with that of

responders, and low-risk patients exhibited higher response rates

and improved survival outcomes compared with high-risk patients

(Fig. 4H-P), confirming the ability

of the signature to stratify immunotherapy benefit.

| Figure 4.Programmed cell death-related

signature acted as a biomarker for predicting the immunotherapy

benefits in SKCM. (A) Level of HLA-related genes, (B) immune

checkpoints, (C) TMB score, (D) PD1 and CTLA-4 immunophenoscore,

(E) TIDE score, (F) immunological escape score and (G) immune

surveillance score in patients with SKCM in different risk score

categories. (H) Risk score, (I) survival rates and (J)

immunotherapy response rate in patients with SKCM with different

risk score in the IMvigor210 cohort. (K) Risk score, (L) survival

rates and (M) immunotherapy response rate in patients with SKCM

with different risk scores in the GSE78220 cohort. (N) Risk score,

(O) survival rates and (P) immunotherapy response rate in patients

with SKCM with different risk scores in the GSE91061 cohort

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. SKCM, skin cutaneous

melanoma; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; TMB, tumor mutation burden;

PD1, programmed cell death protein-1; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

associated protein 4; TIDE, tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion;

GSE, gene expression data series; CR, complete response; PR,

partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease. |

Predictive value for chemotherapy and

targeted therapy sensitivity

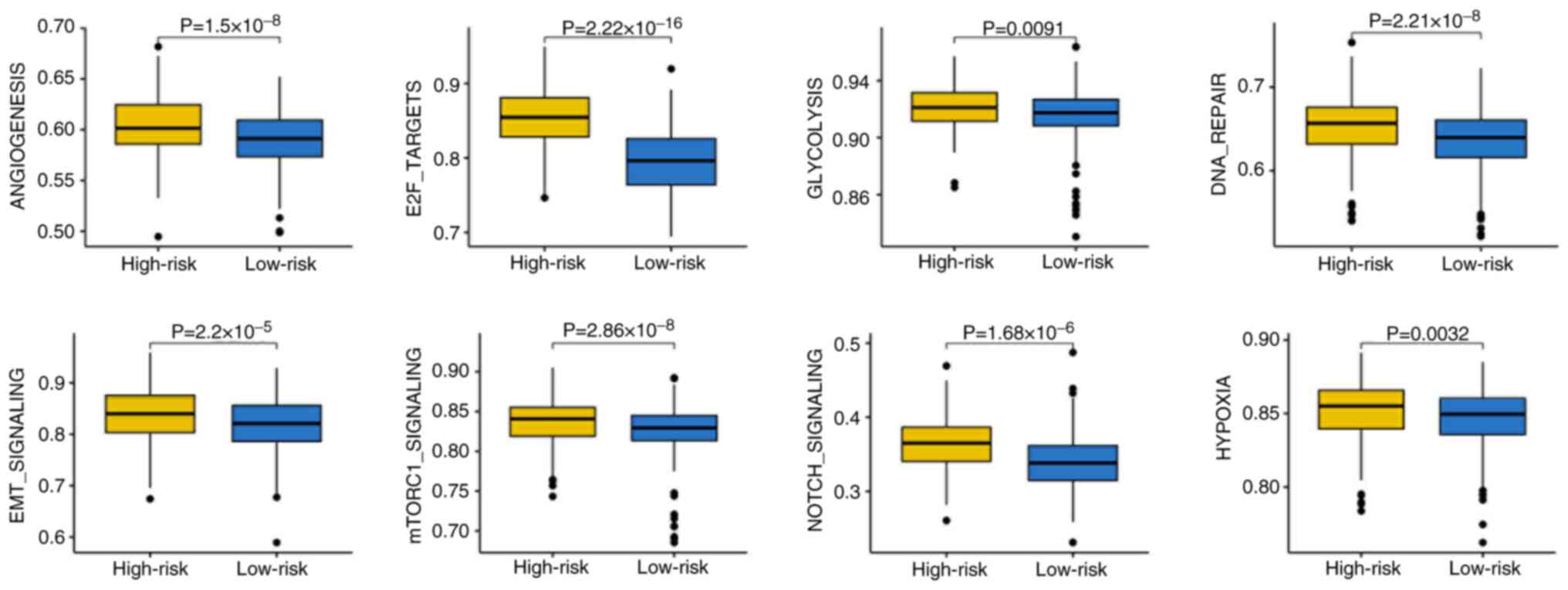

The present study next explored the association

between the risk score and drug sensitivity. Patients with low-risk

scores demonstrated significantly higher IC50 values for

commonly used chemotherapy agents, including 5-fluorouracil,

cisplatin, docetaxel, epirubicin and gemcitabine (Fig. 5A), and for several targeted

therapies such as axitinib, crizotinib, erlotinib, foretinib and

savolitinib (Fig. 5B). These

findings suggested that high-risk patients with SKCM may be more

sensitive to cytotoxic and targeted drugs, while low-risk patients

may derive greater benefit from immunotherapy.

Enrichment of cancer hallmarks in

high-risk patients with SKCM

To elucidate the biological pathways associated with

different risk groups, the present study performed gene set

enrichment analysis. High-risk patients exhibited increased

enrichment scores for cancer-related hallmarks, including

‘angiogenesis’, ‘E2F targets’, ‘glycolysis’, ‘DNA repair’, ‘EMT

signaling’, ‘mTORC1 signaling’, ‘Notch signaling’ and ‘hypoxia’

(Fig. 6). These pathways are

well-known to contribute to tumor progression, immune evasion and

resistance to therapy, potentially explaining the poor prognosis

and lower immunotherapy benefit in high-risk patients.

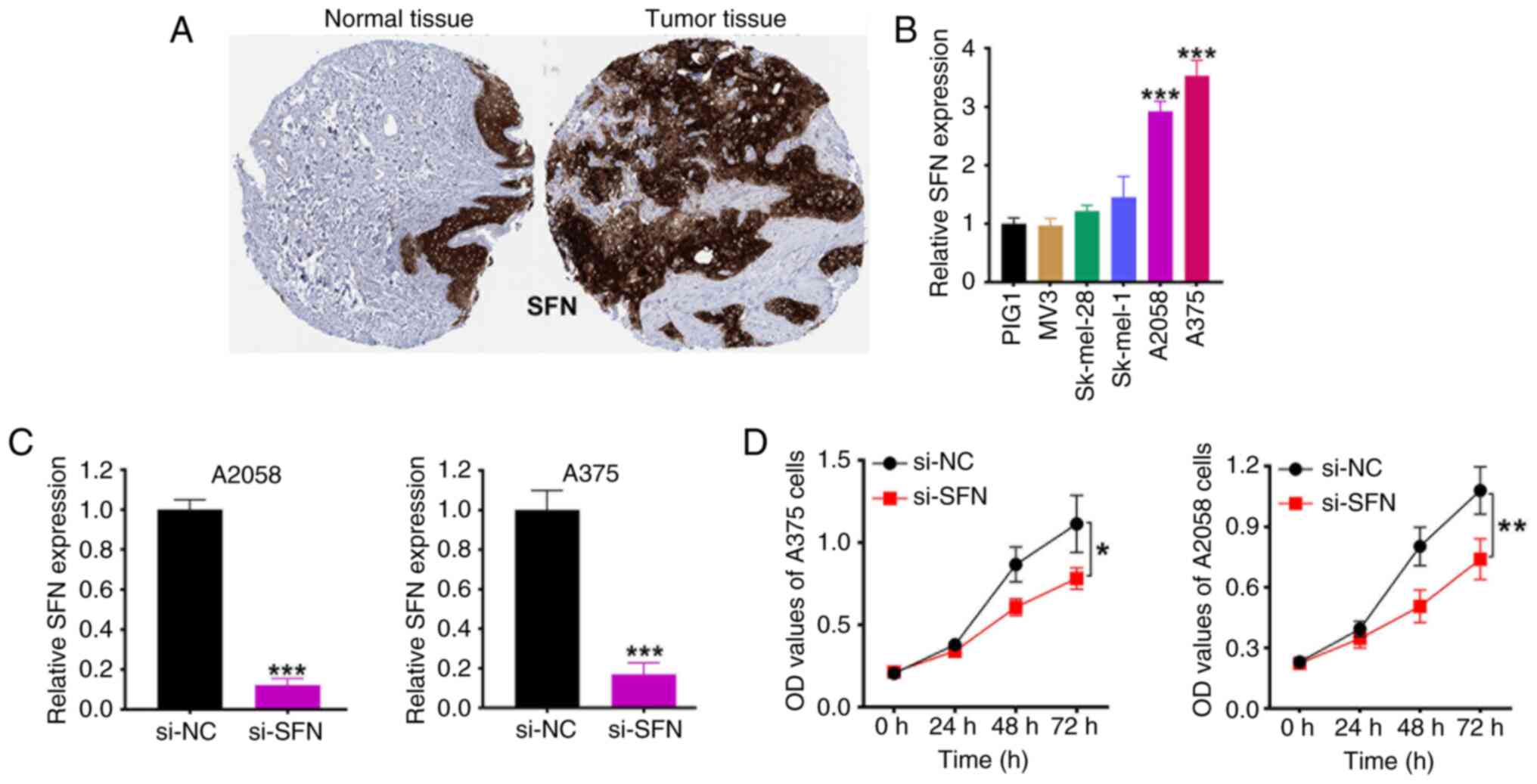

Validation of SFN as a functional

driver gene in SKCM

Among the 13 genes comprising the risk signature,

SFN had the highest positive coefficient and was consistently

upregulated in SKCM tissues. Immunohistochemistry confirmed

elevated SFN protein expression in SKCM compared with that in

normal skin (Fig. 7A). RT-qPCR also

demonstrated higher SFN expression in SKCM cell lines compared with

that in normal melanocytes of A375 and A2058 melanoma cells

(Fig. 7B). The SFN expression of

A375 and A2058 melanoma cells were then knocked down (Fig. 7C). Functionally, knockdown of SFN

significantly inhibited the proliferation of A375 and A2058

melanoma cells, as shown in the CCK-8 assays (Fig. 7D), supporting its role as an

oncogenic driver and validating its inclusion in the risk

model.

Discussion

In the present study, a robust PCDI was developed

and validated using integrated machine learning algorithms to

predict prognosis and immunotherapy response in patients with SKCM.

By integrating multi-cohort data and systematically evaluating 77

algorithm combinations, a 13-gene risk signature that stratifies

patients into distinct prognostic and immunological subtypes with

high accuracy and clinical relevance was identified.

The present study results demonstrated that the PCDI

effectively distinguishes patients with SKCM with poor outcomes

from those with favorable survival, as evidenced by consistent

results across TCGA and multiple independent GEO cohorts. The model

outperformed conventional clinical features such as age, sex and

TNM stage in prognostic prediction, which supports its potential

clinical utility (36,37). The integration of the risk score

into a nomogram further improved individual-level survival

prediction and calibration analyses confirmed its accuracy and

reliability (37).

Notably, the present study findings highlighted a

strong association between the PCDI and the tumor immune

microenvironment. High-risk patients exhibited reduced infiltration

of CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages and antigen-presenting

cells, alongside lower stromal and immune scores, indicating a more

immunosuppressive tumor contexture (38,39).

Conversely, low-risk patients demonstrated a more immunoactive

landscape with higher expression of HLA genes, immune checkpoints

and immune cell infiltration, which suggests a favorable

environment for immunotherapeutic intervention (40).

The relevance of PCDI in predicting immunotherapy

response was further confirmed by its correlation with multiple

immune-related biomarkers. Low-risk patients exhibited higher TMB,

immunophenoscores for PD-1/CTLA-4 and lower TIDE and immune escape

scores compared with patients with a high-risk score, features

known to associate with enhanced response to immune checkpoint

blockade (21,41,42).

These findings were validated across three independent

immunotherapy-treated melanoma cohorts, where low-risk patients

demonstrated significantly improved response rates and OS. These

results suggested that PCDI could serve as a predictive biomarker

to guide immunotherapy decision-making in SKCM (43,44).

Furthermore, the drug sensitivity analysis in the

present study indicated that high-risk patients were more sensitive

to multiple chemotherapeutic and targeted agents, including

5-fluorouracil, cisplatin and several receptor tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (crizotinib, erlotinib and foretinib). This observation

implies a potential trade-off in treatment strategy: While low-risk

patients may benefit more from immunotherapy, high-risk patients

might demonstrate improved response to conventional or targeted

cytotoxic treatment (45). These

findings underscore the value of PCDI in guiding personalized

therapeutic strategies beyond immunotherapy.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses revealed

that high-risk patients with SKCM were enriched in oncogenic

pathways such as glycolysis, E2F signaling, DNA repair, EMT and

hypoxia, all of which are known to contribute to tumor progression,

resistance to therapy and immune evasion (14–16).

These molecular characteristics likely explain the poor prognosis

and reduced immune responsiveness observed in the high-risk

group.

Among the 13 genes in the PCDI, SFN emerged as a

potential oncogenic driver in SKCM. The high expression levels of

SFN were validated at both the transcriptomic and protein levels

and functional assays confirmed its role in promoting melanoma cell

proliferation. These findings suggested that SFN may not only serve

as a biomarker but also represent a potential therapeutic target in

high-risk SKCM. A previous study reported that upregulation of SFN

was associated with the prognosis in ovarian cancer (46). Furthermore, SFN regulates cervical

cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis progression

through Lin-11, Isl-1 and Mec-3 domain kinase 2/cofilin signaling

(47).

Despite the strengths of the present study,

including a large sample size, cross-cohort validation and

integration of multi-dimensional data, several limitations should

be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the datasets

may introduce biases that could affect generalizability. Second,

although the immunotherapy response predictions were validated in

public cohorts, prospective clinical validation is warranted to

confirm the utility of PCDI in guiding treatment decisions. Lastly,

while SFN was functionally validated, the biological roles of other

model genes warrant further investigation.

Further understanding of the molecular mechanisms

through which PCDI-related genes contribute to melanoma progression

and immune modulation is essential. For instance, SFN, identified

as a key oncogenic driver in the present study model, is involved

in cell proliferation control. However, its downstream effectors in

the context of SKCM remain poorly characterized. Future studies

could explore whether SFN modulates tumor progression and immune

evasion pathways, such as PD-L1 expression or antigen presentation

machinery. While the present study PCDI demonstrated predictive

power across public immunotherapy cohorts, validation in

prospective, cohorts including treatment-naïve patients with SKCM

is imperative. Ideally, this would involve enrolling patients prior

to immunotherapy, obtaining baseline biopsies for transcriptomic

profiling, calculating PCDI scores and associating them with

clinical outcomes such as Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors response, progression-free survival and OS.

In conclusion, the present study developed a novel

machine learning-based PCDI that robustly predicts prognosis and

immunotherapy response in SKCM. The index provides valuable

insights into tumor biology and immune phenotypes and holds

potential as a biomarker for personalized therapy in patients with

melanoma. Future studies integrating multi-omics and experimental

validation will further refine and extend the clinical utility of

the present study model.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XW prepared the original draft. XW and YZ performed

the investigation. YZ conducted the formal analysis and curated the

data. SY and HS acquired data, and reviewed and edited the

manuscript. WC and SS analyzed and interpreted the data, and were

involved in project administration. XW and YZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM,

Gershenwald JE and Scolyer RA: Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet.

402:485–502. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J,

Vaccarella S, Meheus F, Cust AE, de Vries E, Whiteman DC and Bray

F: Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to

2040. JAMA Dermatol. 158:495–503. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lopes F, Sleiman MG, Sebastian K, Bogucka

R, Jacobs EA and Adamson AS: UV exposure and the risk of cutaneous

melanoma in skin of color: A systematic review. JAMA Dermatol.

157:213–219. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Leonardi GC, Falzone L, Salemi R, Zanghì

A, Spandidos DA, Mccubrey JA, Candido S and Libra M: Cutaneous

melanoma: From pathogenesis to therapy (Review). Int J Oncol.

52:1071–1080. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N and Dixit

VM: Cell death. Cell. 187:235–256. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu J, Hong M, Li Y, Chen D, Wu Y and Hu

Y: Programmed cell death tunes tumor immunity. Front Immunol.

13:8473452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liang T, Gu L, Kang X, Li J, Song Y, Wang

Y and Ma W: Programmed cell death disrupts inflammatory tumor

microenvironment (TME) and promotes glioblastoma evolution. Cell

Commun Signal. 22:3332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Liu Y, Shou Y, Zhu R, Qiu Z, Zhang Q and

Xu J: Construction and validation of a ferroptosis-related

prognostic signature for melanoma based on single-cell RNA

sequencing. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8184572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nedaeinia R, Dianat-Moghadam H,

Movahednasab M, Khosroabadi Z, Keshavarz M, Amoozgar Z and Salehi

R: Therapeutic and prognostic values of ferroptosis signature in

glioblastoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 155:1145972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang S, Wang R, Hu D, Zhang C, Cao P and

Huang J: Machine learning reveals diverse cell death patterns in

lung adenocarcinoma prognosis and therapy. NPJ Precis Oncol.

8:492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang L, Cui Y, Zhou G, Zhang Z and Zhang

P: Leveraging mitochondrial-programmed cell death dynamics to

enhance prognostic accuracy and immunotherapy efficacy in lung

adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 12:e0100082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cai X, Lin J, Liu L, Zheng J, Liu Q, Ji L

and Sun Y: A novel TCGA-validated programmed cell-death-related

signature of ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 24:5152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang Y and Zhang Q: Leveraging programmed

cell death signature to predict clinical outcome and immunotherapy

benefits in postoperative bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 14:229762024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gu X, Pan J, Li Y and Feng L: A programmed

cell death-related gene signature to predict prognosis and

therapeutic responses in liver hepatocellular carcinoma. Discov

Oncol. 15:712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nayarisseri A, Khandelwal R, Tanwar P,

Madhavi M, Sharma D, Thakur G, Speck-Planche A and Singh SK:

Artificial intelligence, big data and machine learning approaches

in precision medicine & drug discovery. Curr Drug Targets.

22:631–655. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ngiam KY and Khor IW: Big data and machine

learning algorithms for health-care delivery. Lancet Oncol.

20:e262–e273. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jayawardana K, Schramm SJ, Haydu L,

Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Mann GJ, Müller S and Yang JY:

Determination of prognosis in metastatic melanoma through

integration of clinico-pathologic, mutation, mRNA, microRNA, and

protein information. Int J Cancer. 136:863–874. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Budden T, Davey RJ, Vilain RE, Ashton KA,

Braye SG, Beveridge NJ and Bowden NA: Repair of UVB-induced DNA

damage is reduced in melanoma due to low XPC and global genome

repair. Oncotarget. 7:60940–60953. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cabrita R, Lauss M, Sanna A, Donia M,

Skaarup Larsen M, Mitra S, Johansson I, Phung B, Harbst K,

Vallon-Christersson J, et al: Tertiary lymphoid structures improve

immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature. 577:561–565. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Riaz N, Havel JJ, Makarov V, Desrichard A,

Urba WJ, Sims JS, Hodi FS, Martín-Algarra S, Mandal R, Sharfman WH,

et al: Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy

with nivolumab. Cell. 171:934–949.e16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno

BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, Berent-Maoz B, Pang J, Chmielowski B, Cherry G,

et al: Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to Anti-PD-1

therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 165:35–44. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rosenberg JE, Galsky MD, Powles T,

Petrylak DP, Bellmunt J, Loriot Y, Necchi A, Hoffman-Censits J,

Perez-Gracia JL, van der Heijden MS, et al: Atezolizumab

monotherapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Final analysis

from the phase II IMvigor210 trial. ESMO Open. 9:1039722024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: Limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu Z, Liu L, Weng S, Guo C, Dang Q, Xu H,

Wang L, Lu T, Zhang Y, Sun Z and Han X: Machine learning-based

integration develops an immune-derived lncRNA signature for

improving outcomes in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 13:8162022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sturm G, Finotello F and List M:

Immunedeconv: An R package for unified access to computational

methods for estimating immune cell fractions from bulk

RNA-sequencing data. Methods Mol Biol. 2120:223–232. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 4:26122013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Palmeri M, Mehnert J, Silk AW, Jabbour SK,

Ganesan S, Popli P, Riedlinger G, Stephenson R, de Meritens AB,

Leiser A, et al: Real-world application of tumor mutational

burden-high (TMB-high) and microsatellite instability (MSI)

confirms their utility as immunotherapy biomarkers. ESMO Open.

7:1003362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fu J, Li K, Zhang W, Wan C, Zhang J, Jiang

P and Liu XS: Large-scale public data reuse to model immunotherapy

response and resistance. Genome Med. 12:212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Charoentong P, Finotello F, Angelova M,

Mayer C, Efremova M, Rieder D, Hackl H and Trajanoski Z: Pan-cancer

immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype

relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade.

Cell Rep. 18:248–262. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun Y, Wu L, Zhong Y, Zhou K, Hou Y, Wang

Z, Zhang Z, Xie J, Wang C, Chen D, et al: Single-cell landscape of

the ecosystem in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell.

184:404–421.e16. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Maeser D, Gruener RF and Huang RS:

oncoPredict: An R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient

drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief

Bioinform. 22:bbab2602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ,

Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, Buzaid AC, Cochran AJ, Coit DG,

Ding S, et al: Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and

classification. J Clin Oncol. 27:6199–6206. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lin A and Yan WH: HLA-G/ILTs targeted

solid cancer immunotherapy: Opportunities and challenges. Front

Immunol. 12:6986772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lin A, Zhang J and Luo P: Crosstalk

between the MSI status and tumor microenvironment in colorectal

cancer. Front Immunol. 11:20392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR,

Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, Lazar AJ, Faries MB, Kirkwood JM,

McArthur GA, et al: Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the

American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging

manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 67:472–492. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang J, Yang F, Sun Q, Zeng Z, Liu M, Yu

W, Zhang P, Yu J, Yang L, Zhang X, et al: The prognostic landscape

of genes and infiltrating immune cells in cytokine induced killer

cell treated-lung squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Cancer Biol Med. 18:1134–1147. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tien FM, Lu HH, Lin SY and Tsai HC:

Epigenetic remodeling of the immune landscape in cancer:

Therapeutic hurdles and opportunities. J Biomed Sci. 30:32023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G and

Hacohen N: Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated

with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 160:48–61. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sun R, Limkin EJ, Vakalopoulou M, Champiat

S, Han SR, Verlingue L, Brandao D, Lancia A, Ammari S, Hollebecque

A, et al: A radiomics approach to assess tumour-infiltrating CD8

cells and response to anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: an

imaging biomarker, retrospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol.

19:1180–1191. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X,

Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, et al: Signatures of T cell dysfunction

and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med.

24:1550–1558. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu D, Schilling B, Liu D, Sucker A,

Livingstone E, Jerby-Arnon L, Zimmer L, Gutzmer R, Satzger I,

Loquai C, et al: Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of

clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic

melanoma. Nat Med. 25:1916–1927. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gide TN, Quek C, Menzies AM, Tasker AT,

Shang P, Holst J, Madore J, Lim SY, Velickovic R, Wongchenko M, et

al: Distinct immune cell populations define response to anti-PD-1

monotherapy and anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4 combined therapy. Cancer

Cell. 35:238–255.e6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ,

Lightfoot H, Forbes S, Bindal N, Beare D, Smith JA, Thompson IR, et

al: Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC): A resource for

therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res.

41((Database Issue)): D955–D961. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hu Y, Zeng Q, Li C and Xie Y: Expression

profile and prognostic value of SFN in human ovarian cancer. Biosci

Rep. 39:BSR201901002019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Du N, Li D, Zhao W and Liu Y: Stratifin

(SFN) regulates cervical cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, and

cytoskeletal remodeling and metastasis progression through

LIMK2/cofilin signaling. Mol Biotechnol. 66:3369–3381. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|