Lung cancer remains one of the most common and

lethal cancers worldwide, markedly contributing to cancer-related

illness and death (1,2). It is the leading cause of cancer

mortality, with >2 million new cases diagnosed each year and a

persistently low 5-year survival rate, especially in advanced

stages (3–5). The disease is mainly divided into two

subtypes based on histological and molecular features: Non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for ~85% of cases, and

small cell lung cancer (SCLC), representing the remaining ~15% and

known for its rapid growth and early spread (6). NSCLC includes adenocarcinoma, squamous

cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma, each with unique molecular

profiles and clinical behaviors (7).

Lung cancer development and progression are driven

by complex signaling pathways that regulate fundamental cellular

processes such as proliferation, survival, metastasis and

resistance to therapy (8–10). Dysregulation of these pathways often

results from genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations or

environmental exposures, including tobacco smoke, air pollution and

carcinogens such as asbestos and radon (11–14).

Over the past decade, notable progress has been made in elucidating

the molecular mechanisms underlying lung cancer pathogenesis

(15,16). Advances in genomic sequencing have

enabled the identification of key oncogenic drivers, including

mutations in EGFR, rearrangements in anaplastic lymphoma kinase

(ALK), and mutations in KRAS (17–20).

These discoveries have led to the development of targeted therapies

that have fundamentally transformed the clinical management of lung

cancer (21). For example,

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib,

erlotinib and osimertinib, have demonstrated robust efficacy in

patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, markedly improving both

progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared

with conventional chemotherapy (22–25).

Similarly, ALK inhibitors, including crizotinib, alectinib and

lorlatinib, have markedly improved outcomes for patients with

ALK-rearranged NSCLC, offering durable responses and enhanced

quality of life (26–28). KRAS mutations are present in 25–30%

of lung adenocarcinomas and have historically been considered

untreatable with drugs due to the lack of suitable binding pockets

for therapeutic intervention (29,30).

However, recent breakthroughs, particularly the development of KRAS

G12C inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib, have yielded

promising clinical results, opening new therapeutic avenues for

this patient population (30–32).

In addition to well-characterized signaling

pathways, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis serves a central role in tumor

growth and survival in lung cancer (33). Activation of this pathway is

frequently driven by mutations or amplifications in upstream

regulators such as EGFR, KRAS and PI3K itself (34). Dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway contributes to resistance against both chemotherapy and

targeted therapies, thereby positioning it as a key focus of

ongoing research (35). Current

preclinical and clinical investigations are assessing inhibitors

targeting components of this pathway, including PI3K, AKT and mTOR,

both as monotherapies and in combination regimens, with the aim of

overcoming therapeutic resistance and improving patient outcomes

(36–38). The involvement of immune checkpoint

pathways, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed

death receptor ligand-1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T

lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), in tumor immune evasion

has been established (39,40). These insights have facilitated the

development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have

markedly reshaped treatment paradigms for both NSCLC and SCLC

(41). Therapeutic agents such as

pembrolizumab, nivolumab and atezolizumab have demonstrated

clinically meaningful improvements in survival, particularly among

patients with high PD-L1 expression or elevated tumor mutational

burden (42–44). Beyond enhancing clinical outcomes,

these agents have also redefined standard treatment practices, with

the combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy now widely

adopted as a first-line therapy (45).

The present review provides an overview of key

signaling pathways involved in lung cancer pathogenesis, including

EGFR, ALK, KRAS, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and immune checkpoint pathways. It

also highlights recent advances in targeted therapies, such as

next-generation TKIs, monoclonal antibodies and combination

strategies, and their clinical implications.

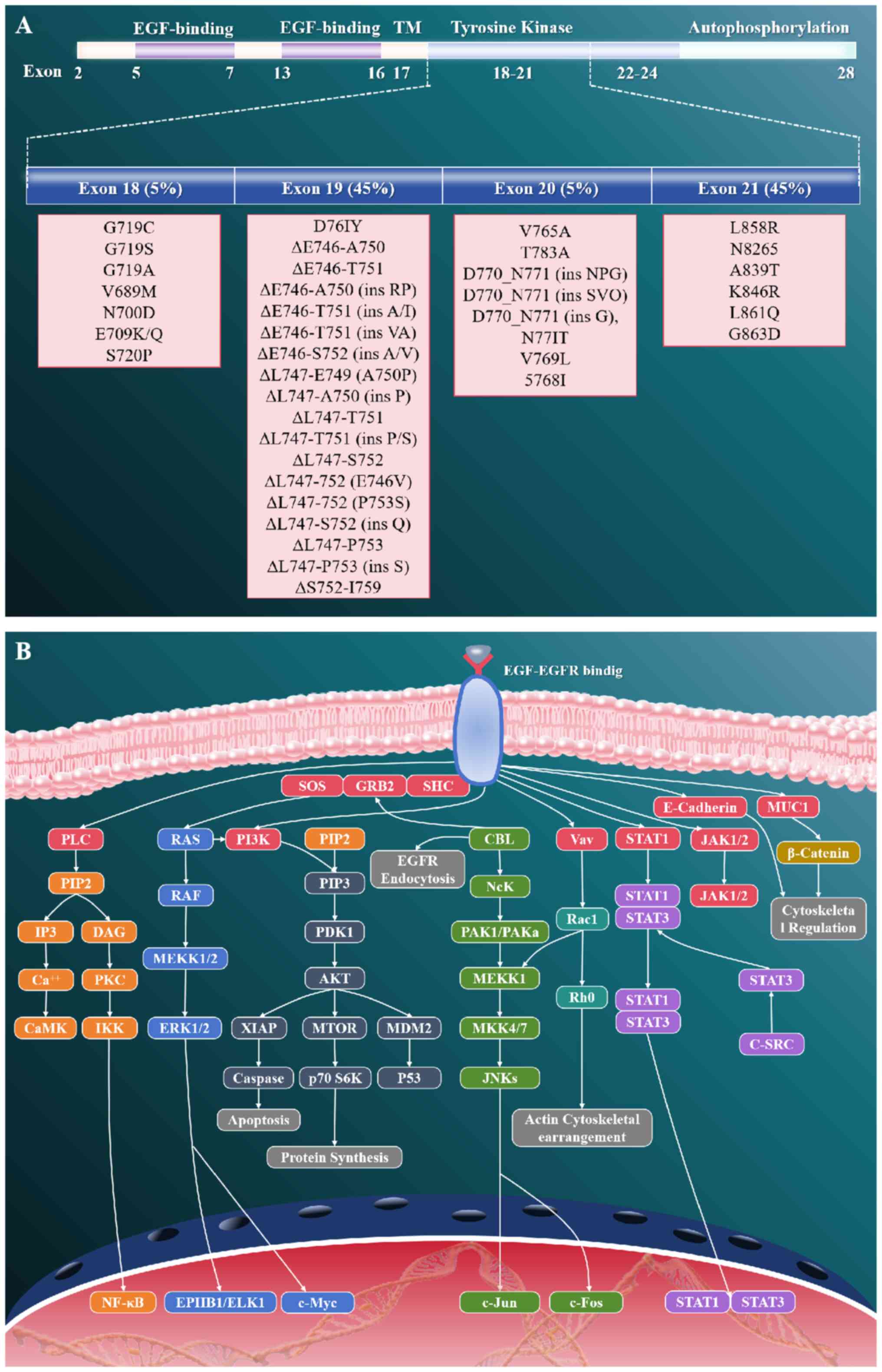

The EGFR pathway represents one of the most

extensively studied and clinically significant signaling cascades

in NSCLC (46). This pathway is

crucial for regulating essential cellular processes, including

proliferation, survival, differentiation and migration (47,48).

In NSCLC, specific genetic alterations in the EGFR gene, most

notably exon 19 deletions and the L858R point mutation in exon 21,

lead to constitutive activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase

(RTK) (49,50) (Fig.

1). Such activation results in ligand-independent dimerization

and subsequent autophosphorylation (48–50).

These oncogenic changes initiate downstream signal transduction

through key pathways including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and

RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK cascades, ultimately driving uncontrolled cell

proliferation, suppression of apoptosis and enhanced tumor

viability (51,52). The recognition of EGFR mutations as

driver oncogenes in NSCLC has fundamentally reshaped the

therapeutic approach to lung cancer (49). First-generation EGFR-TKIs, including

gefitinib and erlotinib, have demonstrated notable efficacy in

patients harboring these mutations, leading to a substantial

improvement in PFS compared with conventional chemotherapy

(53). These small-molecule

inhibitors competitively bind to the ATP-binding site of the EGFR

tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), effectively obstructing downstream

signaling (54). The subsequent

development of second-generation TKIs (such as afatinib and

dacomitinib) alongside third-generation inhibitors (such as

osimertinib) has further enhanced clinical outcomes by addressing

resistance mechanisms whilst increasing target specificity

(55–57).

Despite these advancements, the development of

acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs remains a major clinical

challenge. The most common mechanism of resistance is the T790M

gatekeeper mutation in exon 20, which increases the affinity of the

receptor for ATP and physically impedes TKI binding (58). Other mechanisms contributing to

resistance include MET amplification, human epidermal growth factor

receptor (HER)2 amplification, histologic transformation into SCLC,

and activation of alternative signaling pathways (59–64).

To overcome these challenges, ongoing research is focused on the

development of fourth-generation EGFR inhibitors, combination

therapies targeting parallel signaling pathways and novel

therapeutic approaches such as antibody-drug conjugates and

bispecific antibodies directed against EGFR (65,66).

The evolution of EGFR-targeted therapies in NSCLC

exemplifies a paradigm for precision medicine in oncology, wherein

tumor molecular profiling directly informs clinical

decision-making. Current clinical guidelines emphasize the

importance of comprehensive molecular testing at both initial

diagnosis and during disease progression to identify actionable

genetic alterations and mechanisms of therapeutic resistance

(66). Furthermore, the integration

of liquid biopsy methodologies for ctDNA analysis has facilitated

dynamic monitoring of EGFR mutation status and the detection of

emerging resistance mutations, thereby enabling more timely and

evidence-based treatment adjustments (67,68).

As the understanding of EGFR signaling biology continues to

advance, it is anticipated that novel therapeutic strategies will

further improve clinical outcomes for patients with EGFR-mutated

NSCLC.

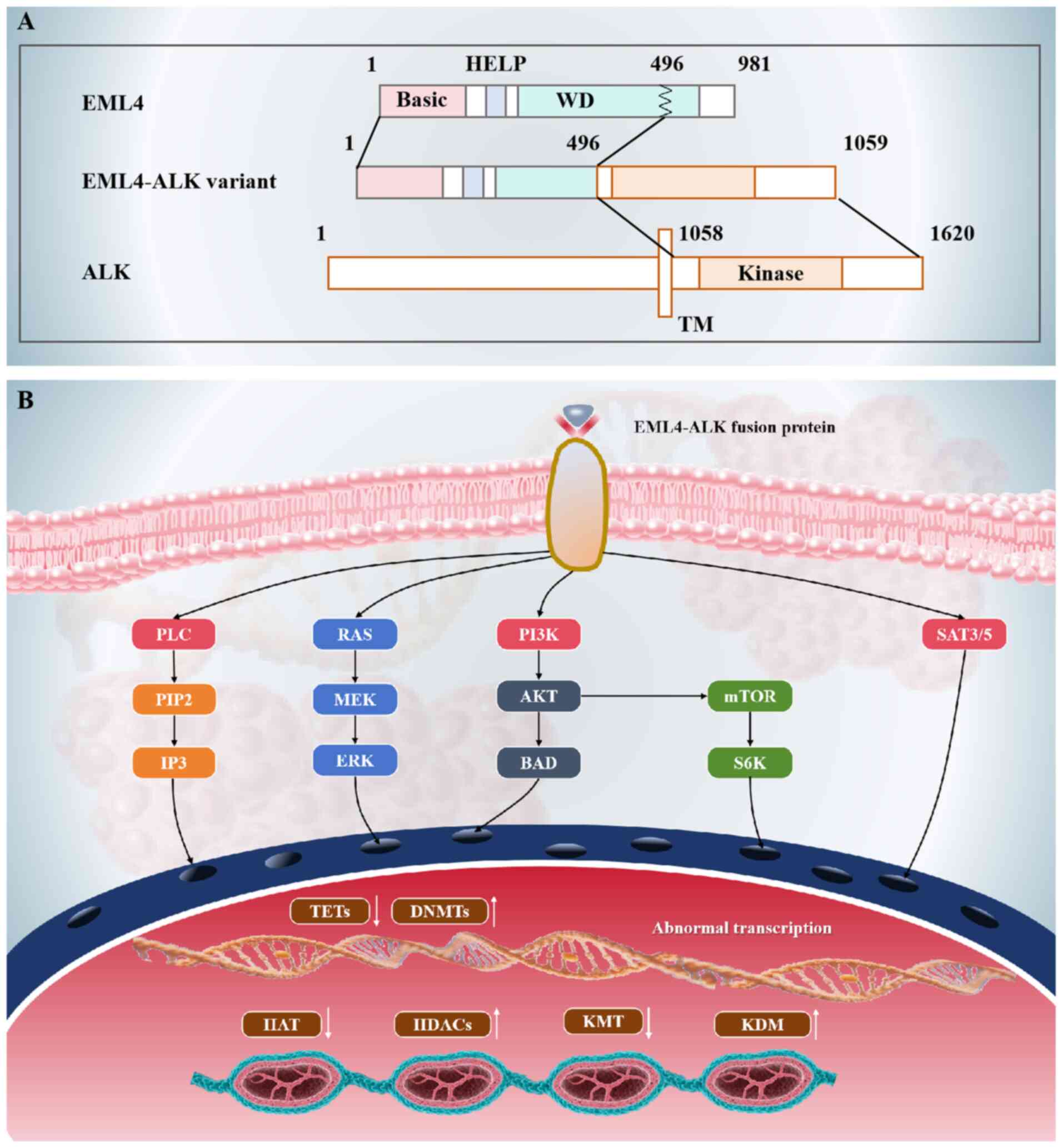

ALK rearrangements, particularly the echinoderm

microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4)-ALK fusion, constitute

a clinically distinct molecular subgroup in NSCLC, occurring in

3–7% of cases (69,70). This genetic aberration originates

from a chromosomal inversion on chromosome 2p, leading to the

fusion of the EML4 gene with the ALK gene (71). The resulting EML4-ALK fusion protein

acts as a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that drives

oncogenic signaling primarily through the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT

pathways, which are key regulators of cell proliferation, survival

and metastasis (72–74) (Fig.

2). The identification of ALK rearrangements has fundamentally

reshaped the therapeutic landscape for patients with ALK-positive

NSCLC (75). Targeted ALK

inhibitors, such as crizotinib, alectinib and lorlatinib, have

demonstrated substantial clinical benefits (76–78).

Crizotinib, as the first-generation ALK inhibitor, was the first to

show marked improvements in PFS and overall response rates compared

with conventional chemotherapy (76). However, despite its initial

efficacy, resistance to crizotinib commonly develops (typically

within 1 year of treatment initiation) due to secondary mutations

within the ALK kinase domain or activation of alternative signaling

pathways (79).

To overcome resistance mechanisms associated with

ALK inhibition, next-generation agents, such as alectinib and

lorlatinib, have been developed. Alectinib, classified as a

second-generation ALK inhibitor, has demonstrated superior clinical

efficacy in both treatment-naïve patients and those who have

developed resistance to crizotinib (77). Its enhanced central nervous system

(CNS) penetration markedly improves therapeutic effectiveness

against brain metastases (77).

Lorlatinib, a third-generation ALK inhibitor, is specifically

designed to target a broad spectrum of ALK resistance mutations and

has shown potent activity in patients who have progressed after

prior ALK inhibitor therapy (78).

Despite these advancements, resistance to ALK

inhibitors remains a notable clinical challenge. Resistance

mechanisms include on-target mutations within the ALK gene,

activation of alternative signaling pathways (referred to as

off-target resistance) and histological transformation (69,80,81).

Current research efforts are directed toward further characterizing

these resistance mechanisms and developing innovative therapeutic

strategies, including combination therapies and fourth-generation

ALK inhibitors-to enhance clinical outcomes for patients with

ALK-positive NSCLC (82–84). The ongoing advancement of

ALK-targeted therapies underscores the essential role of precision

medicine in the effective management of NSCLC.

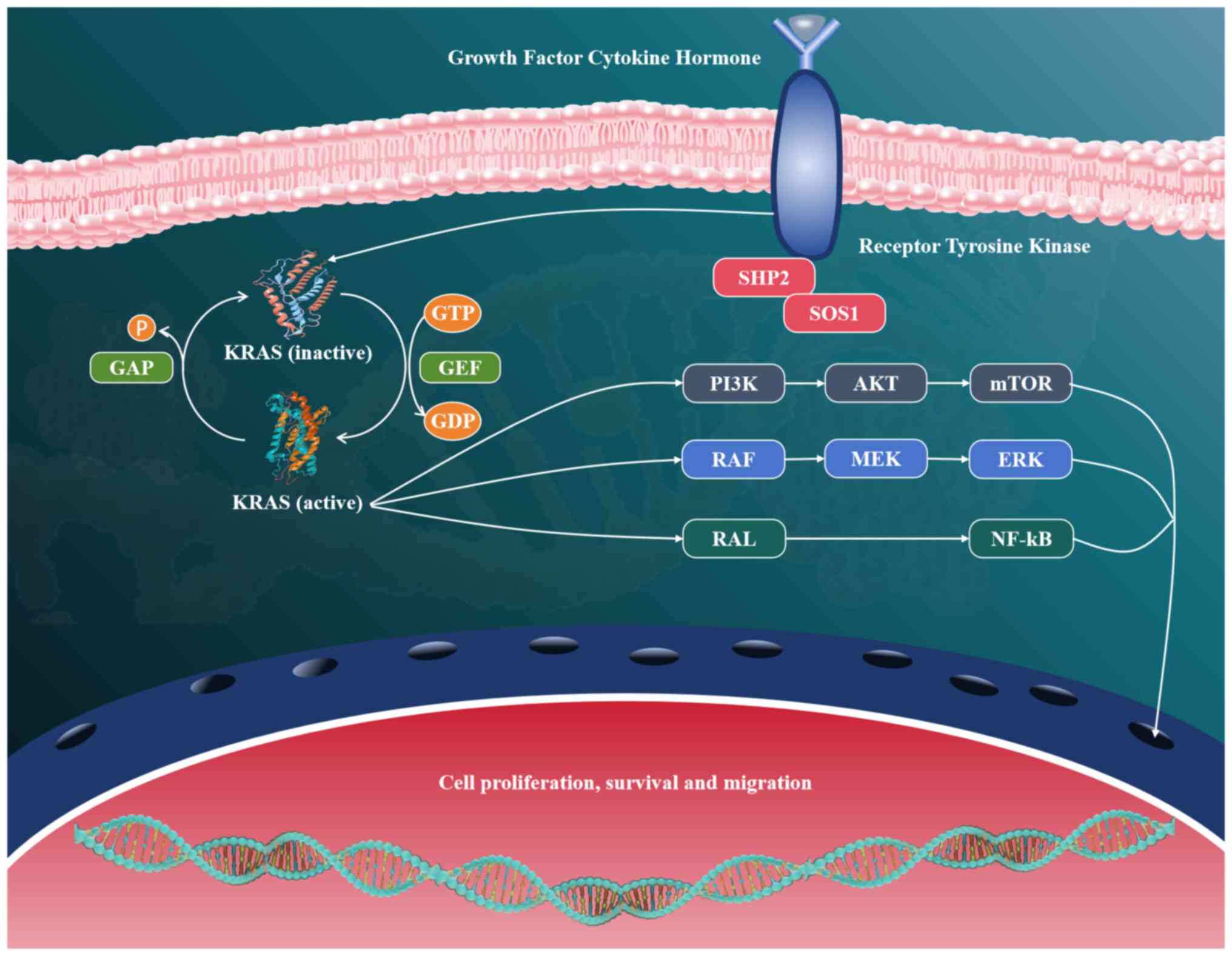

KRAS mutations represent one of the most prevalent

and clinically notable genetic alterations in NSCLC, occurring in

25–30% of cases, particularly among adenocarcinoma subtypes

(85). These mutations are

predominantly located at codon 12 (such as G12C, G12V and G12D),

with lower frequencies observed at codons 13 and 61 (86). They result in constitutive

activation of the KRAS protein, thereby promoting uncontrolled

cellular proliferation and survival (87). The oncogenic activity of mutant KRAS

is primarily mediated through sustained activation of downstream

signaling pathways, most notably the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT cascades

(88). These pathways regulate

essential cellular functions such as cell cycle progression,

metabolic regulation and evasion of apoptosis, ultimately

contributing to tumor growth, metastasis and therapeutic resistance

(89,90) (Fig.

3).

For decades, KRAS was considered ‘undruggable’ due

to its lack of conventional binding pockets and its high affinity

for GTP/GDP, which posed substantial challenges in the development

of small-molecule inhibitors (91).

However, advances in structural biology and drug discovery have

fundamentally transformed the therapeutic landscape for KRAS-mutant

NSCLC (92). The identification of

a unique, druggable pocket adjacent to the G12C mutation site has

enabled the development of covalent inhibitors that selectively

target the mutant cysteine residue (93). Among these agents, sotorasib (AMG

510) and adagrasib (MRTX849) have emerged as promising therapeutic

options, demonstrating notable clinical efficacy in patients with

KRAS G12C-mutant NSCLC (85,94).

Sotorasib, recognized as the first US Food and Drug

Administration-approved KRAS G12C inhibitor, has demonstrated an

objective response rate of ~37% in pretreated patients (95). By contrast, adagrasib has shown both

systemic and intracranial antitumor activity, achieving a response

rate of ~43% in the KRYSTAL-1 trial (96).

These groundbreaking developments have not only

introduced novel therapeutic opportunities for patients with

KRAS-mutant NSCLC but have also spurred extensive research into

combination strategies and next-generation KRAS inhibitors. Current

clinical trials are actively evaluating the potential of combining

KRAS G12C inhibitors with ICIs, Src homology 2 domain-containing

protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 inhibitors or other targeted agents

to overcome resistance mechanisms and improve long-term clinical

outcomes (97–99). Additionally, ongoing efforts are

focused on developing inhibitors specifically targeting alternative

KRAS mutations (such as G12D and G12V), as well as pan-KRAS

inhibitors designed to benefit a broader patient population

(100). Despite these encouraging

advances, several challenges remain, most notably the emergence of

acquired resistance and the need for more effective therapeutic

approaches targeting non-G12C KRAS mutations, which highlights the

critical importance of continued research in this rapidly evolving

field (101,102).

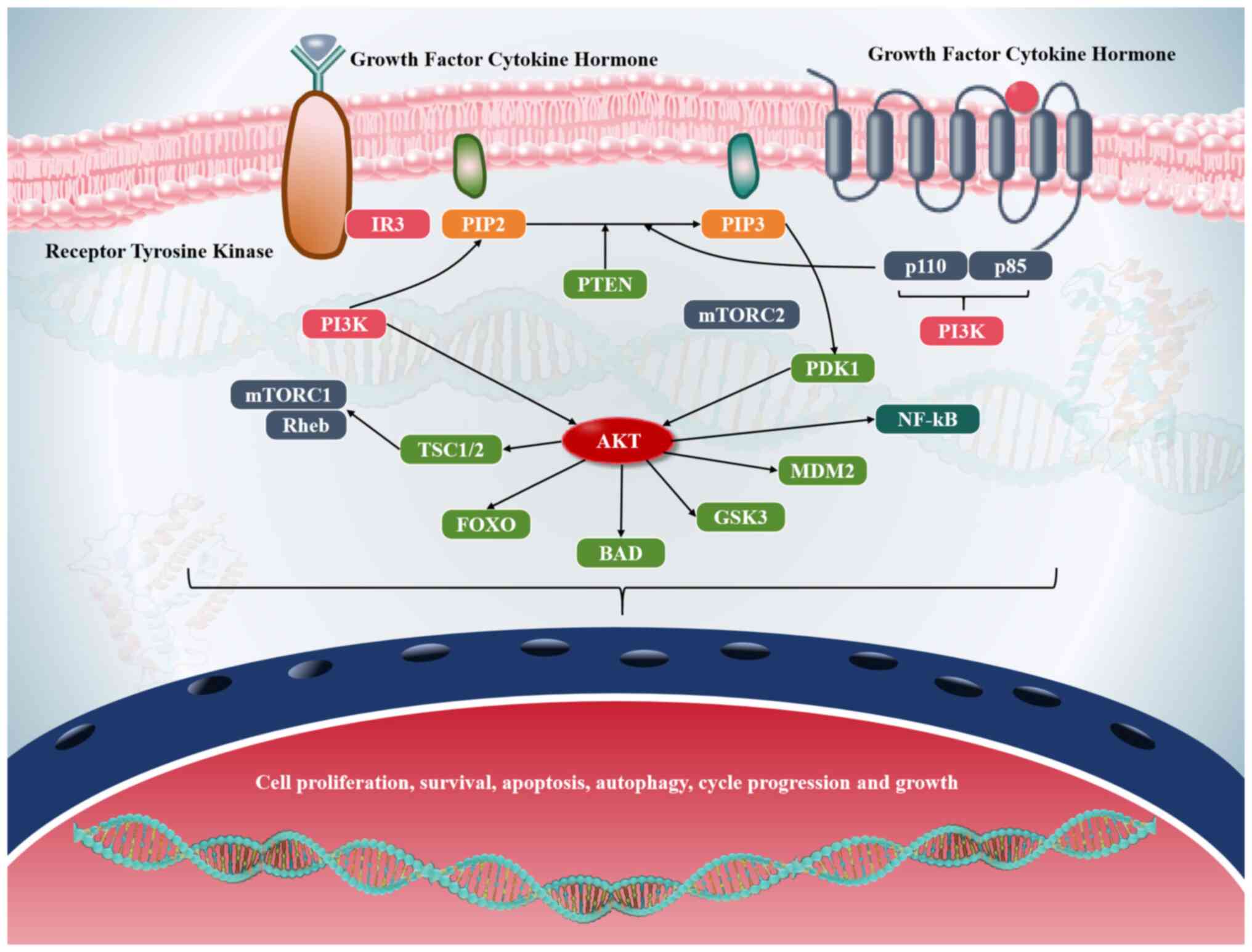

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a highly conserved and

tightly regulated signaling cascade that governs essential cellular

functions such as growth, proliferation, metabolism and survival

(103–105). It integrates signals from diverse

extracellular stimuli, including growth factors, hormones and

nutrients, to coordinate critical cellular responses necessary for

maintaining homeostasis (106–108). Dysregulation of this pathway is

frequently observed in multiple malignancies, particularly lung

cancer, and is often driven by genetic alterations that result in

constitutive activation (109).

Among the most common are activating mutations in PI3K catalytic

subunit α, which encodes the catalytic subunit of PI3K and leads to

elevated PIP3 levels and enhanced signaling output (110). Concurrently, loss-of-function

mutations or deletions in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, a

negative regulator of the pathway, further contribute to sustained

pathway activation (74).

Additionally, amplification or overexpression of AKT reinforces

oncogenic signaling, promoting aberrant cell survival and

proliferation (111). In lung

cancer, these molecular alterations are associated with aggressive

tumor phenotypes characterized by resistance to apoptosis,

increased angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming-all of which

facilitate tumor progression and metastasis (112) (Fig.

4).

Despite compelling biological evidence supporting

the therapeutic targeting of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in lung

cancer, clinical development of inhibitors has encountered notable

obstacles. Although preclinical studies demonstrate that PI3K, AKT

and mTOR inhibitors can effectively suppress tumor growth and

induce apoptosis (73,113), their clinical utility has been

hampered by dose-limiting toxicities and the emergence of

resistance mechanisms (73,113). Common adverse effects, such as

hyperglycemia, rash, diarrhea and hepatotoxicity, frequently

necessitate dose reductions or treatment discontinuation, thereby

compromising therapeutic efficacy (51). Resistance typically develops through

compensatory activation of alternative pathways (such as MAPK/ERK),

feedback loops involving RTKs or mutations in downstream effectors

(114–116). These findings underscore the

complexity of pathway inhibition and highlight the urgent need for

innovative therapeutic strategies.

To overcome these limitations, combination therapies

targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are under intensive

investigation (117). One

promising strategy involves combining pathway inhibitors with other

targeted agents, such as EGFR or MEK inhibitors, to simultaneously

block multiple signaling nodes and prevent adaptive resistance

(118–120). For instance, dual inhibition of

EGFR and PI3K/AKT/mTOR has demonstrated robust synergistic effects

in preclinical models of lung cancer harboring both EGFR mutations

and pathway alterations (118).

Another emerging approach combines PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors with

ICIs, such as anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies, to enhance

antitumor immune responses (121,122). Preclinical evidence indicates that

pathway inhibition can modulate the tumor microenvironment by

reducing immunosuppressive signals and promoting T-cell

infiltration, thereby augmenting the efficacy of immunotherapy

(33,123). Ongoing clinical trials are

evaluating these combinatorial approaches with the goal of

improving clinical outcomes and overcoming resistance in patients

with lung cancer.

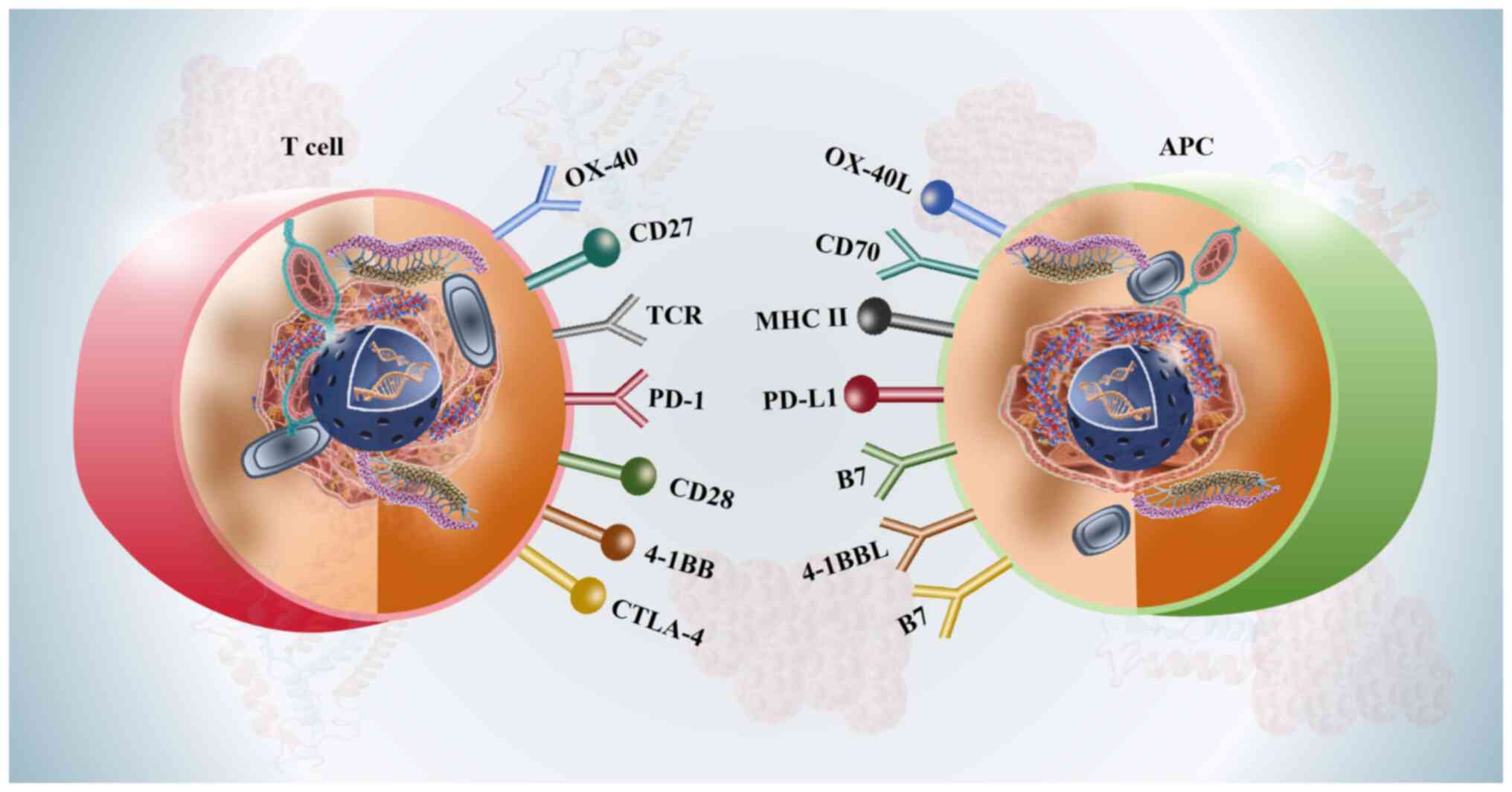

Immune checkpoint pathways, particularly the

PD-1/PD-L1 axis and CTLA-4, serve as critical mechanisms by which

tumors evade immune surveillance (124). Under normal physiological

conditions, these pathways regulate T-cell activation and maintain

immune self-tolerance (125).

However, cancer cells exploit these regulatory mechanisms to

suppress antitumor immune responses, thereby facilitating tumor

growth and metastasis (126). The

PD-1/PD-L1 interaction serves a central role in this immune evasion

process (127). PD-1 is expressed

on activated T cells and binds to PD-L1, which is frequently

overexpressed on tumor cells and within the tumor microenvironment

(124). This interaction inhibits

T-cell proliferation and effector functions, ultimately leading to

T-cell exhaustion and immune tolerance (128). Similarly, CTLA-4, expressed on

both regulatory T cells and activated effector T cells, competes

with CD28 for binding to B7 ligands on antigen-presenting cells,

thereby dampening early T-cell activation and promoting an

immunosuppressive environment (73,129)

(Fig. 5).

The advent of ICIs has markedly transformed the

treatment landscape for advanced NSCLC (130). Monoclonal antibodies targeting

PD-1 (such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab), PD-L1 (such as

atezolizumab) and CTLA-4 (such as ipilimumab) have demonstrated

robust clinical activity by reinvigorating antitumor immunity.

Pembrolizumab was the first ICI approved as a first-line therapy

for patients with NSCLC and high PD-L1 expression (≥50%), based on

the KEYNOTE-024 trial (131). It

notably improved PFS and OS compared with platinum-based

chemotherapy. Nivolumab and atezolizumab have also shown durable

clinical benefit, particularly in patients with high PD-L1

expression or elevated tumor mutational burden (TMB) (132,133). These therapies offer a favorable

toxicity profile relative to conventional chemotherapy,

contributing to improved patient quality of life (132).

Despite these therapeutic advances, both primary and

acquired resistance to ICIs remain notable clinical barriers

(134). Primary resistance refers

to the absence of an initial response, whereas acquired resistance

develops following an initial positive response (135). Resistance mechanisms can be

broadly categorized into tumor-intrinsic and tumor-extrinsic

factors. Tumor-intrinsic mechanisms include loss of antigen

presentation (such as mutations in human leukocyte antigen or

β2-microglobulin), activation of alternative immune checkpoints

(such as T-Cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 or lymphocyte

activating 3) and upregulation of immunosuppressive signaling

pathways (such as TGF-β or indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) (136–138). Tumor-extrinsic mechanisms involve

an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment enriched with

regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells and

M2-polarized macrophages (139).

Additionally, genomic alterations, such as mutations in

serine/threonine kinase 11 or kelch-like ECH associated protein 1,

have been associated with reduced responsiveness to ICIs in NSCLC

(140).

To enhance patient selection and optimize treatment

outcomes, there is a need for reliable predictive biomarkers.

Currently, PD-L1 expression assessed using immunohistochemistry is

the most widely used biomarker; however, its predictive value is

limited. Certain patients with low PD-L1 expression demonstrate

durable responses, whilst others with high expression fail to

respond. TMB, which reflects the total number of somatic mutations

per megabase of genome sequenced, has emerged as a complementary

biomarker (141). Higher TMB

levels are associated with increased neoantigen production and

enhanced immune recognition. Nevertheless, standardization of TMB

assessment remains a challenge. Other emerging biomarkers under

investigation include gene expression signatures, spatial patterns

of immune infiltration and ctDNA analysis (142).

To overcome resistance and improve ICI efficacy,

several combination strategies are being evaluated in clinical

trials. Dual checkpoint inhibition, such as combined PD-1 and

CTLA-4 blockade, has demonstrated synergistic effects in NSCLC

(143). Combinations of ICIs with

targeted therapies (such as EGFR or ALK inhibitors) are also being

explored in molecularly-defined NSCLC subpopulations (144). Another promising approach involves

combining ICIs with agents that modulate the tumor

microenvironment, including angiogenesis inhibitors (such as

bevacizumab) and drugs targeting immunosuppressive myeloid cells

[such as colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitors (CSF1R)]

(145). Furthermore, integrating

ICIs with conventional modalities such as chemotherapy or

radiotherapy has shown potential to enhance antitumor immunity

through mechanisms such as immunogenic cell death and increased

antigen release (146–148).

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous disease that arises

from complex interactions among multiple signaling pathways.

Although targeted therapies have markedly transformed the treatment

landscape for certain patient populations, the development of

resistance mechanisms and pathway redundancies continue to pose

substantial challenges. In addition to the well-established

oncogenic drivers such as EGFR, ALK and KRAS, a multitude of other

signaling pathways contribute to lung cancer pathogenesis, disease

progression and therapeutic resistance. These pathways frequently

interact with known oncogenic drivers, thereby modulating tumor

proliferation, survival, metastasis and immune evasion. The

following section provides an overview of several key signaling

pathways implicated in lung cancer (Table I).

HER2, also known as ErbB2, is a transmembrane

glycoprotein with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (149). It is encoded by the HER2/neu

proto-oncogene located on chromosome 17q21 (149). As a core member of the EGFR/ErbB

family, HER2 serves a pivotal role in regulating fundamental

cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and

survival (150). These functions

underscore its significance in normal embryonic development as well

as in the pathogenesis of several malignancies, particularly NSCLC

(149,150). In lung tumorigenesis, HER2

alterations, including point mutations, gene amplifications and

protein overexpression, drive uncontrolled tumor cell

proliferation, enhance metastatic potential and contribute to

resistance to conventional therapeutic strategies (151). Consequently, HER2 has emerged as a

key therapeutic target in oncology, leading to the development of

targeted agents such as monoclonal antibodies (such as trastuzumab)

and TKIs (such as lapatinib), which are specifically designed to

inhibit its oncogenic signaling (152).

FLT3, also known as CD135 or Flk-2, is a member of

the RTK III family, which includes KIT proto-oncogene, receptor

tyrosine kinase (KIT), platelet-derived growth factor receptor

(PDGFR) and CSF1R (153). The

receptor comprises an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a

transmembrane region and an intracellular TKD (153). FLT3 is predominantly expressed in

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells within the bone marrow,

thymus and lymph nodes, where it regulates myeloid and lymphoid

cell proliferation, survival and differentiation (152,153). Although primarily associated with

hematologic malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FLT3

dysregulation has also been implicated in solid tumors, including

NSCLC (154,155). FLT3 aberrations in lung cancer

occur through three major mechanisms: i) Overexpression associated

with aggressive disease and poor clinical prognosis (155); ii) rare internal tandem

duplication and TKD mutations that may drive tumor progression

(155); and iii) crosstalk with

EGFR, MET or ALK signaling pathways, contributing to drug

resistance in lung adenocarcinoma (155). Given its oncogenic potential, FLT3

is currently under investigation as a therapeutic target in lung

cancer. Small-molecule inhibitors such as midostaurin and

quizartinib, originally developed for AML, are now being evaluated

in clinical trials involving FLT3-altered NSCLC (156). To overcome resistance, combination

therapies incorporating MEK or PI3K/AKT inhibitors are actively

being explored (156).

The PDGFR is a single-chain transmembrane

glycoprotein belonging to the Type III RTK family (157). It is widely expressed in several

cell types, including smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, endothelial

cells, glial cells and chondrocytes (158). PDGFRα, one of its major isoforms,

promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion and neovascularization

(159). Activation of the PDGFR

signaling cascade engages key downstream effectors such as the

RAS-MAPK and PI3K pathways (160).

PDGFRα contributes to lung cancer progression through four

well-defined mechanisms (159): i)

Enhancing cyclin D1 expression and accelerating the G1/S phase

transition; ii) increasing MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels to promote tumor

invasion; iii) inducing VEGF secretion and recruiting

tumor-associated fibroblasts to support angiogenesis; and iv)

activating cancer-associated fibroblasts that release

pro-tumorigenic cytokines. Dysregulation of PDGFR in lung cancer

arises from multiple molecular alterations, including gene

amplification, activating mutations, chromosomal rearrangements,

and autocrine or paracrine activation loops (157–159). Therapeutic strategies targeting

PDGFR include multitargeted TKIs (such as imatinib, sunitinib and

sorafenib), selective inhibitors (such as crenolanib and

olaratumab) and combination regimens with chemotherapy,

anti-angiogenic agents or immunotherapy (159,160). Despite promising preclinical and

clinical evidence, the development of drug resistance and

challenges in patient stratification remain notable barriers

(160). Further understanding of

PDGFR biology may enable the design of more effective therapeutic

strategies for PDGFR-driven lung cancers.

The KIT receptor (CD117) serves a notable role in

lung cancer, particularly in neuroendocrine subtypes such as SCLC

and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (161). As a type III RTK, KIT has a unique

structural organization: Its extracellular domain binds stem cell

factor (SCF) through five immunoglobulin-like loops, whilst the

intracellular region contains a split TKD responsible for

downstream signal transduction (161). This architecture enables KIT to

regulate essential cellular functions, including proliferation,

survival, differentiation and migration (162). A total of 15–20% of SCLC cases

exhibit KIT overexpression coupled with autocrine SCF production,

establishing a self-sustaining growth loop (162). Although TKIs, such as imatinib,

demonstrate robust efficacy in other KIT-driven malignancies, most

notably gastrointestinal stromal tumors, their clinical benefit in

lung cancer is restricted to patients harboring specific activating

mutations or gene amplifications (163). Therefore, comprehensive molecular

profiling is crucial for identifying patients who may derive

therapeutic benefit. Research efforts have been directed toward

developing next-generation KIT inhibitors with enhanced CNS

penetration, such as avapritinib, as well as exploring combination

strategies involving ICIs or epigenetic modulators (162,163).

FGFR, a member of the RTK family, comprises four

principal isoforms: FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4 (164). Upon binding to its ligand,

fibroblast growth factor, FGFR undergoes dimerization and

autophosphorylation, leading to the activation of multiple

downstream signaling pathways, including JAK/STAT, phospholipase

Cγ, PI3K and MAPK (165). These

signaling cascades regulate fundamental cellular processes such as

chemotaxis, differentiation and proliferation, and also serve roles

in the development of nerve cells and fibroblasts (166). Notably, the FGFR pathway functions

as a key oncogenic driver in a subset of lung cancers, particularly

squamous cell carcinomas (167).

Although FGFR-targeted therapies show preclinical efficacy, their

clinical translation requires more precise patient stratification

and strategies to overcome resistance mechanisms (168). Further investigation into FGFR

biology may facilitate the development of novel, molecularly

tailored therapeutic approaches for distinct subtypes of lung

cancer.

The p53 signaling pathway interacts with multiple

intracellular networks and is central to maintaining cellular

homeostasis and normal physiological functions (173). It activates in response to DNA

damage or abnormal proliferation, causing cell cycle arrest and DNA

repair (174). If damage cannot be

repaired, p53 induces apoptosis by activating pro-apoptotic genes

(173). Normally, p53 mRNA levels

are high, but protein levels stay low due to rapid mouse double

minute 2 (MDM2)-mediated ubiquitination and degradation (173–175). MDM2 binds to p53 and promotes its

breakdown, forming a key negative feedback loop (176). Due to its tumor-suppressive

function, p53 pathway dysregulation serves a major role in lung

cancer development (177).

Targeting this pathway may offer potential for personalized

treatment, though challenges remain due to mutations and complex

regulation (178). Advances in

targeted therapy have created new opportunities for leveraging p53

in precision oncology (179).

Integrating comprehensive molecular profiling with the development

of novel agents and rational combination strategies will be

critical to unlocking the therapeutic potential of p53.

Abnormal activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is

strongly associated with lung cancer development (180). Upon binding of Wnt ligands to the

Frizzled-LDL receptor related protein receptor complex on the cell

membrane, Axin translocation is initiated, allowing β-catenin to

accumulate in the nucleus (181).

There, β-catenin interacts with Tcf/Lef transcription factors and

recruits co-activators to drive the expression of Wnt target genes

(182). In the absence of Wnt

signals, β-catenin is phosphorylated and subsequently degraded by a

destruction complex composed of adenomatous polyposis coli protein,

GSK3β and casein kinase 1 α1, thereby maintaining low intracellular

levels of β-catenin (183–185). Under these conditions, Tcf/Lef

functions as a transcriptional repressor, inhibiting gene

expression (186). Mutations in

β-catenin that disrupt the regulation of Wnt signaling have been

identified in several malignancies, including lung, liver, ovarian,

skin, prostate cancer and melanoma (187–191). The Wnt/β-catenin pathway serves a

pivotal role in lung cancer pathogenesis, particularly in tumor

initiation and the maintenance of cancer stem cell properties

(184). Although therapeutic

targeting of this pathway remains challenging due to its

pleiotropic functions and intricate regulatory mechanisms, advances

in molecular profiling and targeted therapies offer promising

avenues for intervention (186,187). Future progress will depend on

integrating molecular stratification with novel agents and rational

combination strategies to fully exploit the therapeutic potential

of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in lung cancer treatment (187–191).

The TGFβ family includes cytokines that inhibit the

growth of normal epithelial cells (199). It consists of TGFβ isoforms,

Activins, Inhibins, Nodal, bone morphogenetic proteins,

anti-Müllerian hormone, and growth and differentiation factors

(200–202). This pathway regulates key cellular

processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis,

extracellular matrix remodeling, differentiation and immune

responses (203). Dysregulated

TGFβ signaling disrupts cellular homeostasis and is associated with

tumor initiation, progression and immune evasion (203). TGFβ initiates signaling by binding

to two transmembrane receptors, TβRI and TβRII, that activate a

downstream signaling cascade (199,203). Upon binding to TβRII, TGFβ

recruits and phosphorylates TβRI (203). Activated TβRI subsequently

phosphorylates SMAD2 and SMAD3, which associate with SMAD4 to form

a transcriptional complex that translocates into the nucleus to

regulate gene expression (204).

As a central regulator of lung cancer progression, aberrant TGFβ

signaling serves a critical role in promoting metastasis and

suppressing antitumor immunity (205). Although targeting this pathway

holds therapeutic promise, further research is needed to clarify

its context-dependent functions and optimize combination therapies

(206). A deeper understanding of

how TGFβ interacts with other oncogenic pathways-such as EGFR and

KRAS-is essential for developing effective precision treatments in

lung cancer (207).

The NF-κB family consists of transcription factors

that regulate essential biological processes such as immunity,

inflammation, cell survival, growth and differentiation (208–210). The mammalian NF-κB family consists

of five members: NF-κB1 (p50), NF-κB2 (p65), RelA (p65), RelB and

c-Rel (211). These proteins form

homodimers or heterodimers, translocate into the nucleus, bind to

κB sites in target genes and control their expression (212). Under normal conditions, NF-κB is

sequestered in the cytoplasm by the inhibitory protein IκB,

remaining in an inactive state (213). Aberrant NF-κB activation, driven

by overexpression or mutations in pathway components, is strongly

associated with lung cancer initiation and progression (214,215). As a central regulator of

inflammation and oncogenesis, NF-κB promotes tumor survival, immune

evasion and metastasis (216).

Although therapeutic targeting is complicated by its essential

physiological roles, precision strategies, such as selective

inhibition and combination therapies, offer potential for improving

lung cancer treatment (217).

Further research on biomarker-guided modulation of NF-κB signaling

is crucial for advancing clinical applications (218).

Insulin and IGF signaling pathways are central

regulators of metabolic processes (219). Previous research demonstrated that

these pathways contribute to tumor initiation and progression,

positioning them as key therapeutic targets (220). The human insulin receptor and IGF1

receptor both have tetrameric structures with intrinsic tyrosine

kinase activity (221). Upon

ligand binding, they phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate

proteins, which activate downstream pathways such as PI3K/AKT and

MAPK, thereby promoting oncogenic processes (220,221). Studies have reported that insulin

and IGF1 stimulate tumor cell proliferation, whereas inhibition of

either pathway suppresses tumor growth (222). The insulin/IGF axis serves as a

critical driver of lung cancer metabolism and progression,

integrating metabolic dysregulation with oncogenic signaling

(223,224). Although the clinical application

of IGF-targeted therapies has encountered challenges, combination

approaches and precision metabolic interventions offer promising

avenues (225). Future research

should focus on overcoming resistance mechanisms and targeting

metabolic vulnerabilities in lung cancer (226).

The development of next-generation TKIs marks a

notable advancement in the treatment of oncogene-driven NSCLC,

particularly for patients exhibiting resistance to

earlier-generation inhibitors (227). These next-generation TKIs,

including osimertinib for EGFR-mutant NSCLC and lorlatinib for

ALK-positive NSCLC, have been specifically designed to overcome the

limitations associated with their predecessors (18,228).

They offer enhanced efficacy, broader activity against resistance

mutations and improved penetration into the CNS (229,230). Such advancements have transformed

the therapeutic landscape, providing renewed hope for patients who

develop resistance to initial therapies.

Osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR-TKI, has

emerged as a cornerstone in the treatment of NSCLC with EGFR

mutations (228). First- and

second-generation EGFR TKIs, including erlotinib, gefitinib and

afatinib, have demonstrated marked clinical benefits for patients

harboring activating EGFR mutations such as exon 19 deletions and

L858R mutations (53–57). However, resistance to these agents

inevitably develops, often due to the acquisition of the EGFR T790M

mutation, which diminishes the binding affinity of

earlier-generation TKIs (228).

Osimertinib was specifically designed to target both activating

EGFR mutations and the T790M resistance mutation, rendering it an

effective option for overcoming this resistance (231). Clinical trials, including the AURA

series and the FLAURA study, have reported that osimertinib offers

superior PFS and OS compared with earlier-generation TKIs, even in

first-line settings (232–234). Furthermore, osimertinib

demonstrates enhanced CNS penetration, making it particularly

effective against brain metastases, a common and challenging

complication associated with EGFR-mutant NSCLC (229). This CNS activity is especially

critical given that 25–40% of patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC

develop brain metastases during their disease course (235).

Similarly, lorlatinib, a third-generation ALK-TKI,

has emerged as a groundbreaking therapy for ALK-positive NSCLC

(18). Earlier-generation ALK

inhibitors, including crizotinib, ceritinib and alectinib, have

demonstrated notable efficacy in treating ALK-rearranged NSCLC

(78). However, resistance

frequently develops due to secondary mutations in the ALK gene or

activation of bypass signaling pathways (69). Lorlatinib was specifically designed

to address these resistance mechanisms and exhibits potent activity

against a broad spectrum of ALK resistance mutations, notably the

highly resistant G1202R mutation (236). The CROWN trial provided compelling

evidence of the superior efficacy of lorlatinib compared with

crizotinib in the first-line treatment setting, showing notably

prolonged PFS and higher intracranial response rates (237). Similar to osimertinib, lorlatinib

also demonstrates marked CNS penetration, rendering it particularly

effective in managing brain metastases, a complication that affects

≤60% of patients with ALK-positive NSCLC throughout their disease

trajectory (230,238).

The enhanced CNS activity of next-generation TKIs

represents a critical feature, particularly given that the brain is

a common site for metastasis in oncogene-driven NSCLC (239). Traditional chemotherapy and

earlier-generation TKIs frequently fail to achieve sufficient drug

concentrations within the CNS due to the presence of the

blood-brain barrier, resulting in inadequate control over brain

metastases (240). By contrast,

next-generation TKIs such as osimertinib and lorlatinib are

specifically designed to penetrate the blood-brain barrier more

effectively, thereby facilitating robust intracranial responses and

delaying the progression of CNS disease (229,230). This capability not only enhances

survival rates but also preserves neurological function and

improves quality of life for patients.

Despite these advancements, resistance to

next-generation TKIs continues to pose a significant challenge. In

the case of osimertinib, resistance mechanisms include the

emergence of EGFR C797S mutations, MET amplification and

histological transformation to SCLC (57). For lorlatinib, resistance may arise

through compound ALK mutations or activation of alternative

signaling pathways (241). To

address these challenges, ongoing research is focused on developing

fourth-generation TKIs, exploring combination therapies, and

investigating novel strategies, such as antibody-drug conjugates

and immunotherapy in oncogene-driven NSCLC (242–244).

An ADC represents a sophisticated and innovative

class of therapeutic agents that integrates the precision of

monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxic effects

characteristic of chemotherapy (245). Structurally, an ADC consists of

three core components: i) A monoclonal antibody engineered to

selectively recognize and bind to a specific antigen expressed on

the surface of tumor cells; ii) a cytotoxic agent, commonly

referred to as the payload, which induces cell death in targeted

cancer cells; and iii) a chemical linker that stably connects the

antibody to the payload (245).

The monoclonal antibody functions as a ‘guided missile’,

selectively delivering the cytotoxic payload directly to tumor

cells whilst minimizing damage to healthy tissues, thereby reducing

off-target toxicity (246). This

targeted delivery mechanism represents one of the key advantages of

ADCs, enabling the use of highly potent cytotoxic agents that would

be too toxic for systemic administration (246).

ADCs are increasingly being adopted in oncology,

particularly in the treatment of lung cancer, where early clinical

trials have shown encouraging results (247–249). In both NSCLC and SCLC, ADCs have

demonstrated notable response rates and improved survival outcomes,

especially among patients who have limited remaining treatment

options (250,251). For example, ADCs targeting

proteins such as HER2, HER3, trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2

(TROP2), carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5

(CEACAM5) and MET in NSCLC, and delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) in SCLC,

have attracted considerable attention due to their ability to

produce durable responses in heavily pretreated populations

(251–254). These findings highlight the

potential of ADCs to address notable unmet needs in lung cancer

therapy, particularly for patients with limited therapeutic

alternatives.

In NSCLC, several ADCs are currently under

investigation, each targeting distinct tumor-associated antigens.

HER2-targeted ADCs, such as trastuzumab deruxtecan, have

demonstrated notable efficacy in NSCLC characterized by HER2

mutations or overexpression (255). Although HER2 mutations are rare in

NSCLC, they are associated with aggressive disease and poor

prognosis; therefore, HER2-targeted ADCs represent a promising

therapeutic strategy for this specific patient population (256). Similarly, HER3-targeted ADCs,

including patritumab deruxtecan, are being evaluated in EGFR-mutant

NSCLC, particularly in patients who have developed resistance to

EGFR-TKIs (257). HER3 is

frequently overexpressed in EGFR-mutant NSCLC and serves a key role

in mediating resistance to targeted therapies, making it an

attractive target for ADC development (258).

TROP2 is another promising target in NSCLC, as it

is overexpressed in a substantial proportion of lung

adenocarcinomas and is associated with poor prognosis (259). Sacituzumab govitecan, a

TROP2-targeted ADC, has demonstrated encouraging activity in NSCLC,

with durable responses observed in patients with advanced disease

(260). In addition, CEACAM5 and

MET are actively being investigated as ADC targets in NSCLC

(246). CEACAM5 is overexpressed

in a subset of lung adenocarcinomas, whilst MET amplification or

overexpression is a well-established driver of tumor growth and

therapeutic resistance in NSCLC (246,261). ADCs directed against these

proteins aim to deliver potent cytotoxic payloads specifically to

tumor cells, thereby overcoming resistance mechanisms and improving

clinical outcomes (262). In SCLC,

DLL3 has emerged as a compelling target for ADC development

(263). DLL3 is highly expressed

on the surface of SCLC cells but is scarcely present in normal

tissues, making it an ideal candidate for targeted therapy

(263). Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a

DLL3-targeted ADC, has shown promising activity in SCLC,

particularly among patients with high DLL3 expression (264). Although early clinical trials

encountered certain challenges, ongoing research is focused on

optimizing the use of DLL3-targeted ADCs and identifying biomarkers

that can predict treatment response (265–267).

However, the development of ADCs for lung cancer

presents multiple challenges. Key considerations include the

optimization of target selection, improvement of linker stability

to prevent premature release of the cytotoxic payload, and

effective management of toxicities such as interstitial lung

disease, which has been reported with certain ADCs (268–270). Moreover, the identification of

predictive biomarkers is crucial for selecting patients most likely

to benefit from ADC therapy, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy

(253).

Combination strategies, such as dual inhibition of

EGFR and MET or concurrent targeting of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

along with immune checkpoints, are currently under active

investigation to overcome resistance and improve therapeutic

outcomes (147,271,272). These approaches aim to address the

complex and heterogeneous nature of cancer biology, where

single-agent therapies often fail due to the development of

resistance mechanisms and tumor heterogeneity (273).

For example, dual inhibition of EGFR and MET

represents a promising therapeutic approach in cancers

characterized by co-activation of these pathways or in cases where

resistance to EGFR inhibitors arises from MET amplification or

signaling activation (274). EGFR

is a well-characterized oncogenic driver involved in tumor

proliferation across multiple malignancies, including NSCLC

(46). However, resistance to

EGFR-TKIs frequently emerges through mechanisms such as activation

of the MET pathway (275). By

simultaneously targeting both EGFR and MET, researchers seek to

block compensatory signaling pathways that tumors utilize to evade

therapeutic pressure, thereby prolonging the duration of treatment

response (276).

Similarly, the co-targeting of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway and immune checkpoints represents a synergistic strategy in

cancer therapy (277). The

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway functions as a central regulator of cell

growth, survival and metabolic processes, with its dysregulation

commonly observed across multiple tumor types (120). However, inhibitors targeting this

pathway frequently trigger feedback activation of compensatory

signaling mechanisms, which can compromise their therapeutic

effectiveness (122). Combining

PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors with ICIs, such as anti-PD-1 or

anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, aims not only to suppress tumor

proliferation directly but also to enhance the ability of the

immune system to recognize and eradicate malignant cells (278). This combinatorial strategy

leverages the potential of immunotherapy to counteract the

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment often reinforced by

aberrant PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling (279).

These combination strategies are supported by

preclinical evidence and early-phase clinical trials, which have

shown encouraging results in terms of tumor regression and

prolonged PFS (280–282). Nonetheless, several challenges

remain, including the optimization of dosing regimens, mitigation

of overlapping toxicities and the identification of predictive

biomarkers to guide patient selection for those most likely to

derive clinical benefit (283). As

research progresses, these combination therapies hold promise to

transform the treatment paradigm for cancers that currently present

major therapeutic challenges when managed with monotherapies.

Liquid biopsies, which analyze ctDNA, have emerged

as a transformative, non-invasive tool for detecting targetable

mutations and monitoring treatment responses in patients with

cancer (284). By contrast to

traditional tissue biopsies, often requiring invasive procedures

and potentially failing to capture the full genetic heterogeneity

of tumors, liquid biopsies offer a minimally invasive alternative

that can be serially performed over time (285). This approach involves isolating

ctDNA, which consists of DNA fragments shed by tumor cells into the

bloodstream, and analyzing them for clinically relevant genetic

alterations such as mutations, amplifications or gene fusions that

drive tumorigenesis (286). By

providing a real-time molecular profile of the tumor, liquid

biopsies enable clinicians to identify actionable mutations,

including EGFR, ALK or BRAF variants, and guide personalized

therapeutic strategies accordingly (287).

One of the most notable advantages of liquid

biopsies is their ability to monitor treatment response and detect

emerging resistance mechanisms (288). For example, in patients receiving

targeted therapies such as EGFR inhibitors, resistance mutations,

such as T790M in NSCLC, can be detected early through ctDNA

analysis (289). Such early

identification allows for timely adjustments to treatment regimens.

Moreover, liquid biopsies can assess tumor burden and minimal

residual disease following surgical resection or systemic therapy,

thereby offering valuable prognostic insights that support clinical

decision-making regarding adjuvant or maintenance treatments

(290).

Biomarker-driven approaches, which rely on the

identification of specific molecular alterations, serve a

fundamental role in personalizing cancer therapy and improving

patient outcomes (291). By

integrating liquid biopsy data with clinical and pathological

information, clinicians can stratify patients into distinct

molecular subgroups and select therapies most likely to achieve

favorable outcomes (292,293). For instance, patients with

HER2-positive breast cancer or KRAS-mutated colorectal cancer can

be matched to targeted therapies or clinical trials evaluating

novel agents specifically designed to target their unique genetic

profiles (294,295). This precision medicine strategy

not only enhances therapeutic efficacy but also minimizes

unnecessary exposure to ineffective treatments and their associated

adverse effects (296).

Furthermore, liquid biopsies serve an increasingly

central role in clinical trials by facilitating patient selection,

monitoring pharmacodynamic responses and evaluating the impact of

investigational therapies on tumor genetics (297). As technological advancements,

marked by improvements in sensitivity, specificity and the ability

to detect low-frequency mutations, continue to evolve, liquid

biopsies are poised to become a cornerstone of modern oncology care

(298). These innovations hold the

potential to transform how cancer is diagnosed, treated and

monitored, ultimately advancing the development of more

personalized, effective and patient-centered therapeutic strategies

(298,299).

Despite marked advancements in targeted therapy for

lung cancer, several critical challenges persist that require

focused attention and innovative strategies. One of the most

pressing concerns is the inevitable emergence of resistance to

targeted therapies, which can occur through both on-target and

off-target mechanisms (300).

Primary resistance affects 20–30% of patients, whilst acquired

resistance typically develops within 9–14 months after treatment

initiation, substantially limiting the duration of clinical benefit

(301). The underlying mechanisms

of resistance are complex and heterogeneous, encompassing secondary

mutations in the target gene (such as EGFR T790M and C797S),

activation of bypass signaling pathways (such as MET amplification

and HER2 activation) and histological transformations (such as

conversion to SCLC) (302–304).

The identification and validation of predictive

biomarkers remain a major challenge in optimizing targeted

therapeutic strategies (305).

Although considerable progress has been achieved in detecting

common driver mutations (such as EGFR, ALK and ROS1), there is an

urgent need for more sensitive and comprehensive biomarker

platforms capable of detecting rare mutations, gene fusions and

intricate molecular profiles (306–308). Liquid biopsy technologies,

particularly ctDNA analysis, have shown promise in this regard;

however, their application remains limited by issues of sensitivity

and specificity, particularly in the context of early-stage disease

and minimal residual disease monitoring (309).

Moreover, the development of effective therapies

for rare molecular subtypes, collectively representing 10–15% of

NSCLC cases, remains a notable unmet clinical need (227). These subtypes encompass rare

genetic alterations such as EGFR exon 20 insertions, HER2

mutations, RET fusions, NTRK fusions and MET exon 14 skipping

mutations (64–67). Although targeted therapies have been

developed for several alterations, certain patients still lack

effective treatment options (71).

Furthermore, the limited size of patient populations associated

with these rare subtypes poses substantial challenges for clinical

trial enrollment and pharmaceutical development.

Future research should focus on several key areas

to effectively address the aforementioned challenges: i)

Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of resistance through

comprehensive genomic profiling and functional investigations; ii)

developing novel therapeutic agents, including fourth-generation

EGFR inhibitors, covalent KRAS inhibitors and selective RET

inhibitors; iii) optimizing combination strategies that target

multiple pathways concurrently whilst maintaining acceptable

toxicity profiles; iv) advancing biomarker discovery through

multi-omics approaches and artificial intelligence-assisted data

analysis; and v) innovating clinical trial designs, such as basket

trials and platform trials, to accelerate drug development for rare

molecular subtypes.

Additionally, there is an increasing necessity to

integrate targeted therapies with other treatment modalities, such

as immunotherapy and radiotherapy, to develop more comprehensive

treatment strategies. The investigation of novel drug delivery

systems, including antibody-drug conjugates and nanoparticle-based

therapies, may also present new opportunities to enhance

therapeutic efficacy whilst minimizing systemic toxicity.

Signaling pathways serve a crucial role in the

pathogenesis of lung cancer, driving essential processes such as

cell proliferation, survival, invasion and metastasis. The

dysregulation of these pathways, often resulting from genetic

mutations or amplifications, serves as a hallmark of lung cancer

and contributes to its aggressive behavior and resistance to

conventional therapies. Targeted therapies that specifically

inhibit these aberrant signaling pathways have transformed the

treatment landscape for lung cancer, particularly in NSCLC, which

constitutes the majority of cases. Advancements in understanding of

these signaling pathways have also facilitated the development of

innovative therapeutic strategies, including combination therapies

and next-generation inhibitors aimed at overcoming resistance

mechanisms. Ongoing research and clinical trials are imperative to

address existing challenges and further propel advancements in the

field of precision oncology.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

ZT, WS and HaZ were responsible for conception and

design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of

data. SX, JZ and JR revised the article. XW and HuZ completed the

final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Li Y, Wu X, Yang P, Jiang G and Luo Y:

Machine learning for lung cancer diagnosis, treatment, and

prognosis. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 20:850–866. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bade BC and Dela Cruz CS: Lung cancer

2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med.

41:1–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Harðardottir H, Jonsson S, Gunnarsson O,

Hilmarsdottir B, Asmundsson J, Gudmundsdottir I, Saevarsdottir VY,

Hansdottir S, Hannesson P and Gudbjartsson T: Advances in lung

cancer diagnosis and treatment-a review. Laeknabladid. 108:17–29.

2020.(In Icelandic). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Abu Rous F, Singhi EK, Sridhar A, Faisal

MS and Desai A: Lung cancer treatment advances in 2022. Cancer

Invest. 41:12–24. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wu F, Wang L and Zhou C: Lung cancer in

China: Current and prospect. Curr Opin Oncol. 33:40–46. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rodriguez-Canales J, Parra-Cuentas E and

Wistuba II: Diagnosis and molecular classification of lung cancer.

Cancer Treat Res. 170:25–46. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Sousa VML and Carvalho L: Heterogeneity

in lung cancer. Pathobiology. 85:96–107. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Abolfathi H, Arabi M and Sheikhpour M: A

literature review of microRNA and gene signaling pathways involved

in the apoptosis pathway of lung cancer. Respir Res. 24:552023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Niu Z, Jin R, Zhang Y and Li H: Signaling

pathways and targeted therapies in lung squamous cell carcinoma:

Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

7:3532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan M, Zhao Y, Arkenau HT, Lao T, Chu L

and Xu Q: Signal pathways and precision therapy of small-cell lung

cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Masciale V, Banchelli F, Grisendi G,

Samarelli AV, Raineri G, Rossi T, Zanoni M, Cortesi M, Bandini S,

Ulivi P, et al: The molecular features of lung cancer stem cells in

dedifferentiation process-driven epigenetic alterations. J Biol

Chem. 300:1079942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hoque MO, Brait M, Rosenbaum E, Poeta ML,

Pal P, Begum S, Dasgupta S, Carvalho AL, Ahrendt SA, Westra WH and

Sidransky D: Genetic and epigenetic analysis of erbB signaling

pathway genes in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 5:1887–1893. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

He H, He MM, Wang H, Qiu W, Liu L, Long L,

Shen Q, Zhang S, Qin S, Lu Z, et al: In utero and

childhood/adolescence exposure to tobacco smoke, genetic risk, and

lung cancer incidence and mortality in adulthood. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med. 207:173–182. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen CY, Huang KY, Chen CC, Chang YH, Li

HJ, Wang TH and Yang PC: The role of PM2.5 exposure in lung cancer:

Mechanisms, genetic factors, and clinical implications. EMBO Mol

Med. 17:31–40. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nagano T, Tachihara M and Nishimura Y:

Molecular mechanisms and targeted therapies including immunotherapy

for non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets.

19:595–630. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Samarelli AV, Masciale V, Aramini B, Coló

GP, Tonelli R, Marchioni A, Bruzzi G, Gozzi F, Andrisani D,

Castaniere I, et al: Molecular mechanisms and cellular contribution

from lung fibrosis to lung cancer development. Int J Mol Sci.

22:121792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ohmori T, Yamaoka T, Ando K, Kusumoto S,

Kishino Y, Manabe R and Sagara H: Molecular and clinical features

of EGFR-TKI-associated lung injury. Int J Mol Sci. 22:7922021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Schneider JL, Lin JJ and Shaw AT:

ALK-positive lung cancer: A moving target. Nat Cancer. 4:330–343.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Reck M, Carbone DP, Garassino M and

Barlesi F: Targeting KRAS in non-small-cell lung cancer: Recent

progress and new approaches. Ann Oncol. 32:1101–1110. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yoda S, Dagogo-Jack I and Hata AN:

Targeting oncogenic drivers in lung cancer: Recent progress,

current challenges and future opportunities. Pharmacol Ther.

193:20–30. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Herrera-Juárez M, Serrano-Gómez C,

Bote-de-Cabo H and Paz-Ares L: Targeted therapy for lung cancer:

Beyond EGFR and ALK. Cancer. 129:1803–1820. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yoneda K, Imanishi N, Ichiki Y and Tanaka

F: Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR-mutations. J

UOEH. 41:153–163. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hosomi Y, Morita S, Sugawara S, Kato T,

Fukuhara T, Gemma A, Takahashi K, Fujita Y, Harada T, Minato K, et

al: Gefitinib alone versus gefitinib plus chemotherapy for

non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated epidermal growth factor

receptor: NEJ009 study. J Clin Oncol. 38:115–123. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Greenhalgh J, Bagust A, Boland A, Dwan K,

Beale S, Hockenhull J, Proudlove C, Dundar Y, Richardson M, Dickson

R, et al: Erlotinib and gefitinib for treating non-small cell lung

cancer that has progressed following prior chemotherapy (review of

NICE technology appraisals 162 and 175): A systematic review and

economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 19:1–134. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Remon J, Besse B, Aix SP, Callejo A,

Al-Rabi K, Bernabe R, Greillier L, Majem M, Reguart N, Monnet I, et

al: Osimertinib treatment based on plasma T790M monitoring in

patients with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): EORTC

lung cancer group 1613 APPLE phase II randomized clinical trial.

Ann Oncol. 34:468–476. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Abdelgalil AA and Alkahtani HM:

Crizotinib: A comprehensive profile. Profiles Drug Subst Excip

Relat Methodol. 48:39–69. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S,

Ahn JS, Kim DW, Ou SI, Pérol M, Dziadziuszko R, Rosell R, et al:

Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive

non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 377:829–838. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Solomon BJ, Liu G, Felip E, Mok TSK, Soo

RA, Mazieres J, Shaw AT, de Marinis F, Goto Y, Wu YL, et al:

Lorlatinib versus crizotinib in patients with advanced ALK-positive

non-small cell lung cancer: 5-Year outcomes from the phase III

CROWN study. J Clin Oncol. 42:3400–3409. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Luo J, Ostrem J, Pellini B, Imbody D,

Stern Y, Solanki HS, Haura EB and Villaruz LC: Overcoming

KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 42:1–11.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, Heist RS,

Ou SI, Pacheco JM, Johnson ML, Sabari JK, Leventakos K, Yau E, et

al: Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring a

KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 387:120–131. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ,

Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, Schuler M, Borghaei H, Barlesi F,

et al: Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl

J Med. 384:2371–2381. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Olivier T and Prasad V: Sotorasib in

KRAS(G12C) mutated lung cancer. Lancet. 403:1452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sanaei MJ, Razi S, Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi A

and Bashash D: The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in lung cancer; oncogenic

alterations, therapeutic opportunities, challenges, and a glance at

the application of nanoparticles. Transl Oncol. 18:1013642022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Iksen, Pothongsrisit S and Pongrakhananon

V: Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in lung cancer: An

update regarding potential drugs and natural products. Molecules.

26:41002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ghareghomi S, Atabaki V, Abdollahzadeh N,

Ahmadian S and Hafez Ghoran S: Bioactive PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR

inhibitors in targeted lung cancer therapy. Adv Pharm Bull.

13:24–35. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tan AC: Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR

pathway in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac Cancer.

11:511–518. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen B, Song Y, Zhan Y, Zhou S, Ke J, Ao

W, Zhang Y, Liang Q, He M, Li S, et al: Fangchinoline inhibits

non-small cell lung cancer metastasis by reversing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and suppressing the cytosolic

ROS-related Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. Cancer Lett.

543:2157832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li J, Zhang D, Wang S, Yu P, Sun J, Zhang

Y, Meng X, Li J and Xiang L: Baicalein induces apoptosis by

inhibiting the glutamine-mTOR metabolic pathway in lung cancer. J

Adv Res. 68:341–357. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cheng W, Kang K, Zhao A and Wu Y: Dual

blockade immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in lung

cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 17:542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shen X, Huang S, Xiao H, Zeng S, Liu J,

Ran Z and Xiong B: Efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 plus CTLA-4

antibodies ± other therapies in lung cancer: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 30:3–8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Vergnenegre A and Chouaid C: Economic

analyses of immune-checkpoint inhibitors to treat lung cancer.

Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 21:365–371. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N,

Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L,

et al: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 372:2018–2028. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cascone T, Awad MM, Spicer JD, He J, Lu S,

Sepesi B, Tanaka F, Taube JM, Cornelissen R, Havel L, et al:

Perioperative nivolumab in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med.

390:1756–1769. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Vallières E,

Martínez-Martí A, Rittmeyer A, Chella A, Reck M, Goloborodko O,

Huang M, et al: Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after

chemotherapy in resected stage II–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer

(IMpower010): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III

trial. Ann Oncol. 34:907–919. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang T, Li W, Diwu D, Chen L, Chen X and

Wang H: Efficacy and safety of first-line immunotherapy plus

chemotherapy in treating patients with extensive-stage small cell

lung cancer: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Immunol.

14:11970442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

da Cunha Santos G, Shepherd FA and Tsao

MS: EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 6:49–69. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S,

Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et

al: EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical

response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 304:1497–1500. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Liu X, Wang P, Zhang C and Ma Z: Epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR): A rising star in the era of

precision medicine of lung cancer. Oncotarget. 8:50209–50220. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Agraso S, Lázaro M, Firvida XL, Santomé L,

Fernández N, Azpitarte C, Leon L, Garcia C, Hudobro G, Areses MC,

et al: Real-world data with afatinib in Spanish patients with

treatment-naïve non-small-cell lung cancer harboring exon 19

deletions in epidermal growth factor receptor (Del19 EGFR):

Clinical experience of the Galician lung cancer group. Cancer Treat

Res Commun. 33:1006462022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Matsui T, Tanizawa Y and Enatsu S: Exon 19

deletion and exon 21 L858R point mutation in EGFR Mutation-positive

non-small cell lung cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 48:673–676.

2021.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yu J, Zhang L, Peng J, Ward R, Hao P, Wang

J, Zhang N, Yang Y, Guo X, Xiang C, et al: Dictamnine, a novel

c-Met inhibitor, suppresses the proliferation of lung cancer cells

by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways.

Biochem Pharmacol. 195:1148642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wen Z, Jiang R, Huang Y, Wen Z, Rui D,

Liao X and Ling Z: Inhibition of lung cancer cells and

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction by ectonucleoside triphosphate

phosphohydrolase-7 (ENTPD7). Respir Res. 20:1942019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Qin BM, Chen X, Zhu JD and Pei DQ:

Identification of EGFR kinase domain mutations among lung cancer

patients in China: Implication for targeted cancer therapy. Cell

Res. 15:212–217. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang Q, Dai HH, Dong HY, Sun CT, Yang Z

and Han JQ: EGFR mutations and clinical outcomes of chemotherapy

for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lung

Cancer. 85:339–345. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang C, Zhao K, Hu S, Dong W, Gong Y and

Xie C: Clinical outcomes of afatinib versus osimertinib in patients

with non-small cell lung cancer with uncommon EGFR mutations: A

pooled analysis. Oncologist. 28:e397–e405. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sun H and Wu YL: Dacomitinib in

non-small-cell lung cancer: A comprehensive review for clinical

application. Future Oncol. 15:2769–2777. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P,

Giovannetti E and Tiseo M: Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in

EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 121:725–737.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Skoulidis F and Papadimitrakopoulou VA:

Targeting the gatekeeper: Osimertinib in EGFR T790M

mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

23:618–622. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Spagnolo CC, Ciappina G, Giovannetti E,

Squeri A, Granata B, Lazzari C, Pretelli G, Pasello G and Santarpia

M: Targeting MET in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A new old

story? Int J Mol Sci. 24:101192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Oh DY and Bang YJ: HER2-targeted

therapies-a role beyond breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

17:33–48. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yin X, Li Y, Wang H, Jia T, Wang E, Luo Y,

Wei Y, Qin Z and Ma X: Small cell lung cancer transformation: From

pathogenesis to treatment. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:595–606. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Cheng WL, Feng PH, Lee KY, Chen KY, Sun

WL, Van Hiep N, Luo CS and Wu SM: The role of EREG/EGFR pathway in