Introduction

Prostate cancer remains a major public health issue

worldwide, being the second leading cause of death. In 2020, the

number of cancer patients exceeded 50 million. Moreover, it

accounts for >19 million new cases and nearly 10 million deaths

globally each (1). Approximately

10% of patients are diagnosed at the metastatic stage, according to

data from sources such as the French National Cancer Institute. The

therapeutic management of metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate

cancer has undergone a drastic evolution in the past decade, with

intensification emerging as the standard therapeutic approach

(2–7).

Whilst the primary metastatic sites typically

involve the lymph nodes, bones, lungs and liver, reports of

metastatic involvement in the digestive system are scarce. The

prognosis and management of such cases are inadequately described

in the current literature (8). In

the present article, a rare case of prostate adenocarcinoma with

metastasis to the colon is presented, providing information on its

unique challenges and outlining the approach taken for its

management.

Case report

The patient, a 72-year-old man, was initially

asymptomatic but had a medical history of amebiasis and sigmoid

colectomy due to diverticulosis. The family history of the patient

included leukemia in a nephew and a brother, as well as

microsatellite stability colonic cancer in a daughter (diagnosed at

45 years old) and a brother (diagnosed at 50 years old). Due to

this familial predisposition, the patient underwent regular

colorectal cancer screenings, involving colonoscopies with

resection of low-grade dysplastic polyps.

In January 2020, during a routine screening at Bégin

Military Hospital (Saint-Mandé, France), three sub-centimeter

polyps were resected. A total of two were conventional colonic

adenomas with low-grade dysplasia, whilst the third consisted of

non-signet-ring isolated cells forming small clusters, occasionally

with small lumina, infiltrating the lamina propria between normal

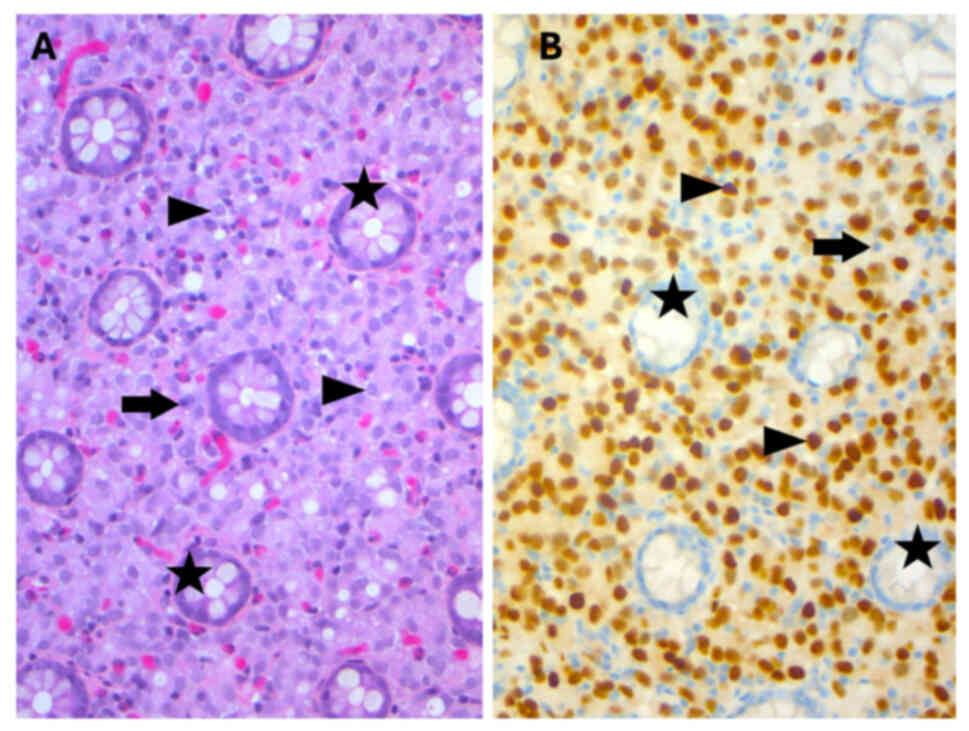

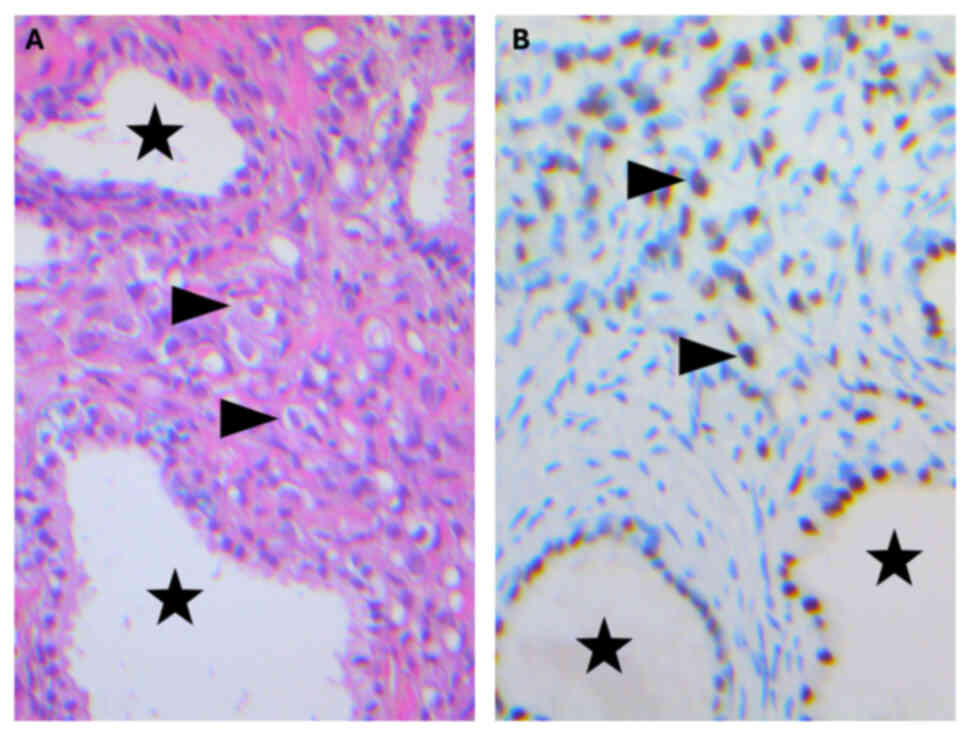

colonic glands (Fig. 1A).

Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated diffuse positivity for

NK3 homeobox 1 (NKX3.1; Fig. 1B),

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and prosaposin (PSAP), and negativity for

caudal type homeobox 2, transcription termination factor 1, GATA

binding protein 3 and paired box 8 (Fig. 2). Due to the high specificity and

sensitivity of NKX3.1 for prostate adenocarcinoma, with negative

markers not suggesting intestinal, pulmonary, urothelial or renal

primary cancer, the presented staining profile required further

clinical investigation to identify if there was a prostatic primary

with metastasis to the colon (9).

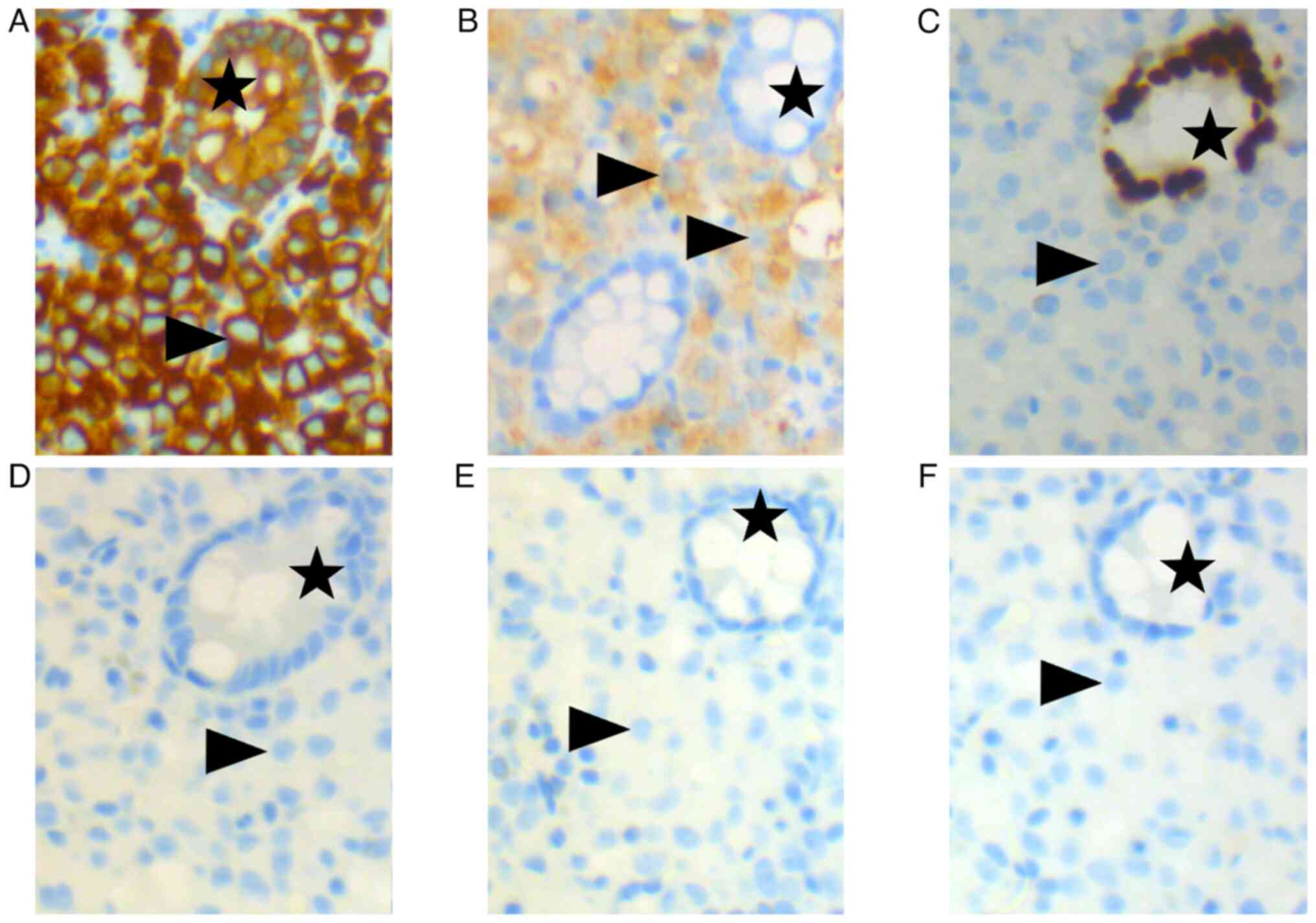

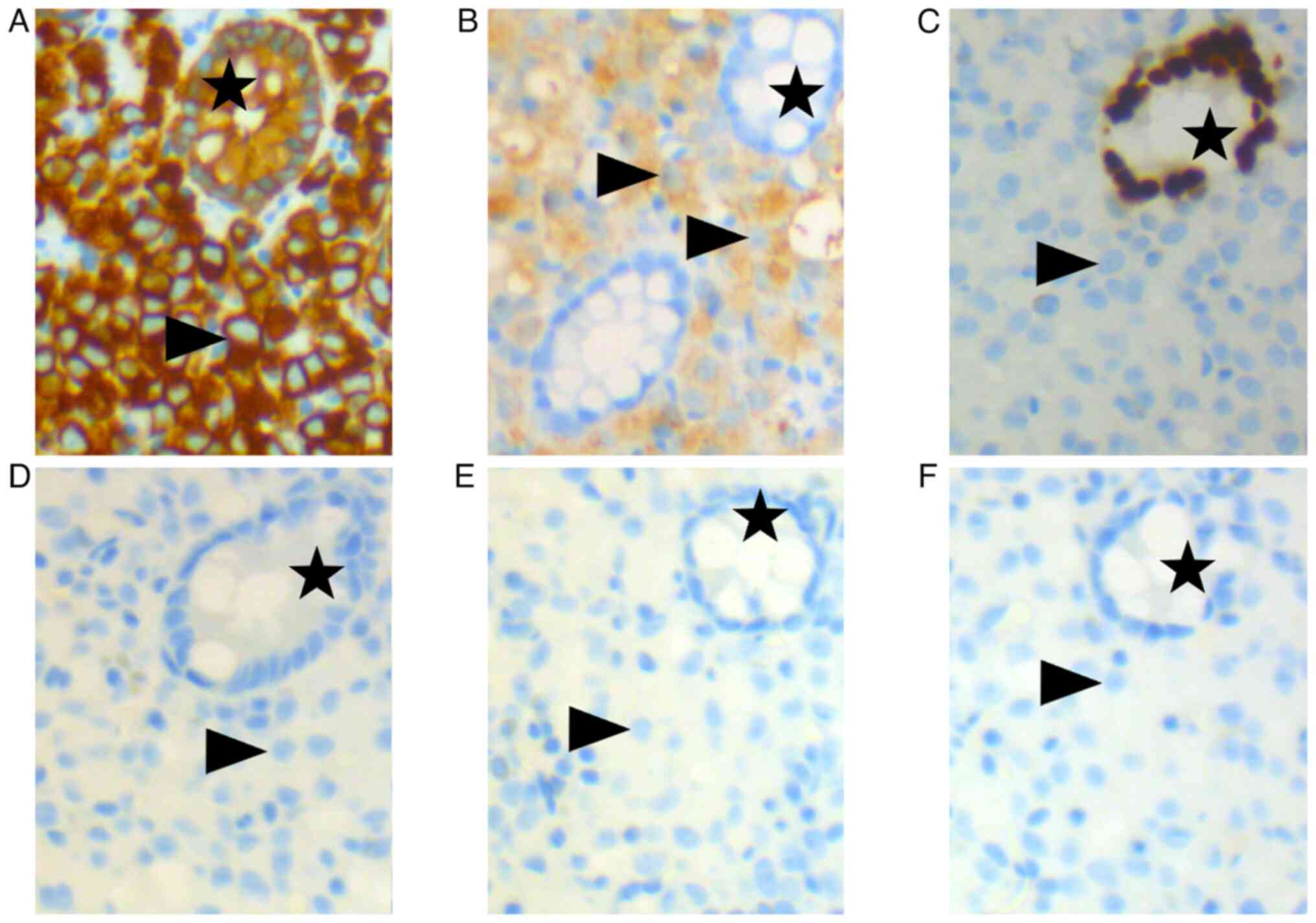

| Figure 2.Immunohistochemical staining performed

on a colonic polyp. (A) Positive, brown-colored cytoplasmic

staining of cytokeratin AE1/AE3 was observed in tumoral single

cells (arrowheads), indicating an epithelial nature, and in cells

of normal colonic crypts (stars), which serve as a positive

internal control. (B) Positive cytoplasmic staining of prosaposin

was observed in tumoral single cells (arrowheads), suggesting, in

addition to NK3 homeobox 1, a prostatic primary, whereas normal

blue-colored cells of normal colonic crypts (stars) were negative.

(C) No nuclear stain was observed in tumoral single cells

(arrowheads) stained with caudal type homeobox 2 antibodies,

suggesting this was not an intestinal primary, whereas cells of

normal colonic crypts (stars) were positive, serving as a positive

internal control. No nuclear stain was seen in tumoral single cells

(arrowheads) with (D) transcription termination factor 1, (E) GATA

binding protein 3 and (F) paired box 8 antibodies, nor in cells of

normal colonic crypts (stars); therefore not indicating a lung,

urothelial or kidney primary. Magnification, ×200. |

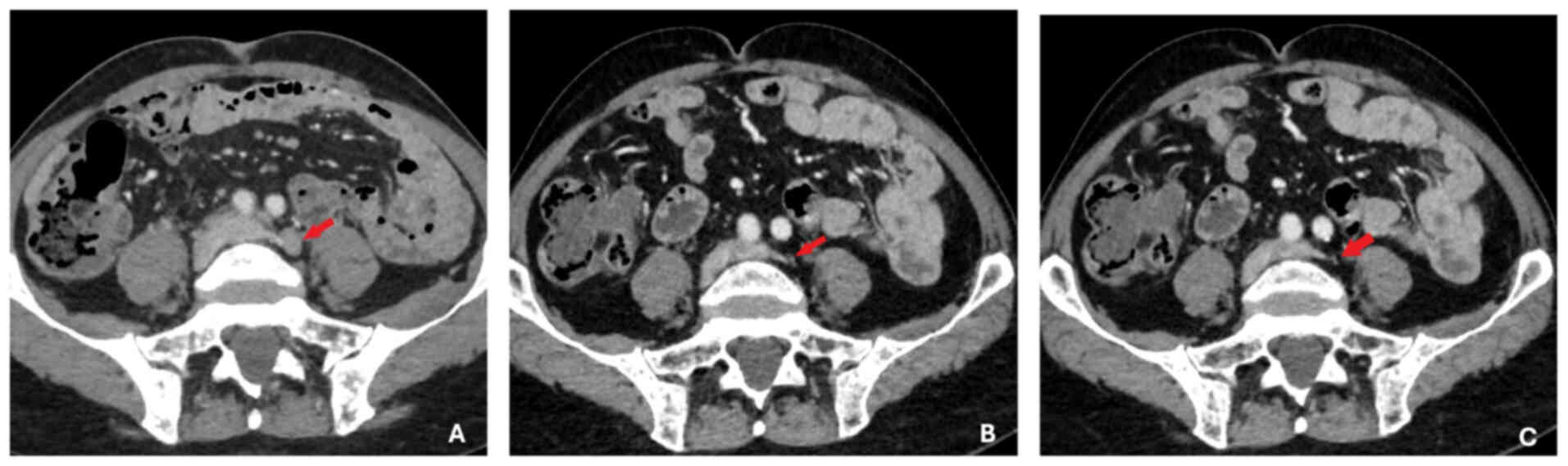

Following this unexpected potential diagnosis, a

prostate specific antigen (PSA) test revealed an elevated level of

1,286 ng/ml (reference range, 0–4 ng/ml). Imaging studies,

including a thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan, showed diffuse

secondary bone lesions, pelvic and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy

and prostatic hypertrophy without identifiable suspicious lesions

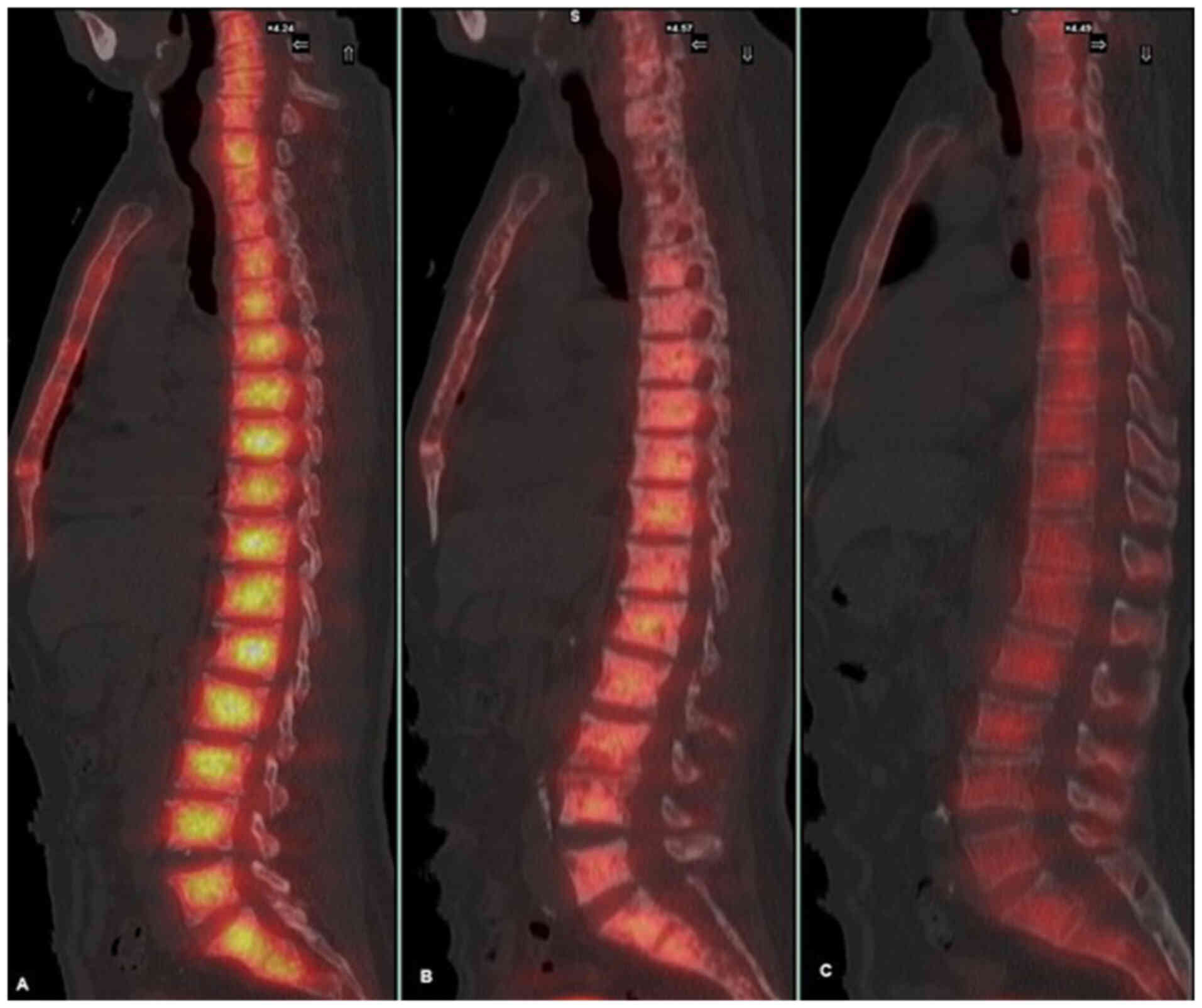

(Fig. 3). Bone scintigraphy

demonstrated a ‘super bone scan’, indicative of diffuse

osteomedullary involvement (Fig.

4).

Prostate needle biopsy (Fig. 5) showed a Gleason score of 4+5=9

adenocarcinoma [The International Society of Urological Pathology

(ISUP) grade group 5] (9). Gleason

pattern 5, consisting of single cells infiltrating prostatic

tissue, appeared morphologically similar to those seen in the

colonic lesion of the patient which stained positive for NKX3.1

(8). Finally, as subsequent

investigations into the initial histological observations revealed

an aggressive prostatic primary tumor by PSA test and prostate

needle biopsy, the clinical and histological data were consistent

with a metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma with a rare colonic

metastasis.

The patient underwent molecular screening of the

prostate and colonic metastases tissues, as well as circulating

tumor DNA (ctDNA) and germinal screening, all of which were

negative (data not shown). Saliva and blood samples were analyzed

for germline alterations using the Invitae Multi-Cancer panel,

which includes the Fanconi anemia complementation group A gene.

Plasma derived from blood was also tested for cell-free DNA using

the Resolution ctDx HRD™ assay by Exact Sciences. Additionally,

tumor tissue was analyzed to detect tumor-derived alterations using

the FoundationOne® CDx test by Foundation Medicine,

Inc.

The treatment choice for the patient was based on

three key factors: i) The prognosis of the disease, which was poor

due to visceral involvement; ii) the patient and comorbidities,

particularly age; and iii) the maintenance of quality of life.

Based on these points, two options were possible: i)

Intensification with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) + androgen

receptor pathway inhibitor (ARPI); or ii) a triplet with ADT +

abiraterone acetate (AA) + docetaxel or ADT + enzalutamide +

docetaxel. Data from PEACE 1 indicate that for patients aged >70

years old, there is no overall survival (OS) benefit from the

triplet, and it is associated with a marked increase in adverse

effects, such as cardiovascular issues and cytopenias (7). In the ENZAMET study, which evaluated

the combination of ADT + enzalutamide + docetaxel compared with the

standard arm of ADT +/- docetaxel, no benefit was demonstrated for

the enzalutamide + docetaxel combination (10). All trials evaluating intensification

with a doublet have demonstrated a clear OS benefit for this

population, along with a marked improvement in quality of life, as

measured by standardized scales (7,10).

Therefore, the doublet was chosen as the therapeutic option for the

patient in the present case.

The patient began anti-hormonal treatment with the

gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone antagonist, degarelix, at an

initial dosage of 240 mg, administered only once, followed by an

80-mg injection 1 month later, which was then repeated monthly,

leading to a rapid decline in PSA levels to 687.5 ng/ml at 15 days.

After 1 month, an androgen synthesis inhibitor, abiraterone

acetate, was also administered at a dosage of 1,000 mg/day, orally.

The patient showed a rapid, clinical, biological (PSA <0.02

ng/ml at 6 months onwards) and radiological response over a 3-year

period, indicating successful disease management, 3 months of the

initiation of the association. The patient experienced no side

effects aside from grade 1 hot flashes, decreased libido and mild

grade 1 anxiety, according to the CTCAE version 5 (11).

Monitoring of efficacy and tolerance was conducted

through telemonitoring and an in-person medical visit every 3

months.

Histology

Specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin (4% formaldehyde solution) at room temperature (20–25°C)

for 24–48 h depending on the size and type of tissue. After

fixation, the tissue was processed using a series of alcohols for

dehydration (70, 80, 95 and 100%) and xylene for clearing, followed

by embedding in molten paraffin wax at 58–60°C. The paraffin block

was cut into 4- to 5-µm sections. The slides were then incubated in

xylene to remove paraffin wax, followed by rehydration through

graded alcohols (100, 95 and 70%) to water. The slides were

incubated in hematoxylin for 3–5 min at room temperature and then

rinsed under running tap water for 1–2 min. Differentiation was

performed in acid alcohol (optional) and bluing in alkaline water

or Scott's tap water substitute for 30 sec. Slides were immersed in

eosin for 1–2 min at room temperature. For dehydration, slides were

passed through graded alcohols (70, 95 and 100%) and cleared in

xylene. Finally, the slides were mounted with a coverslip using a

mounting medium. A brightfield microscope was used for

observation.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a

Ventana Benchmark Ultra stainer with UltraView Universal DAB

Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics). Positive staining for NKX3.1

(EP356 clone; Bio SB, Inc) is highly indicative of a prostatic

primary tumor. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on a

colonic polyp. Positive, brown-colored cytoplasmic staining of

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (PCK26 clone; Roche Diagnostics) was observed

in tumoral single cells, indicating an epithelial nature, and in

cells of normal colonic crypts (stars), which served as a positive

internal control (Fig. 2A).

Positive cytoplasmic staining of prosaposin (PASE/4LJ clone; Cell

Marque™; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was observed in tumoral single

cells, suggesting, in addition to NK3 homeobox 1, a prostatic

primary, whereas normal blue-colored cells of normal colonic crypts

(stars) were negative (Fig. 2B). No

nuclear stain was observed in tumoral single stained with caudal

type homeobox 2 antibodies (PASE/4LJ clone; Cell Marque™;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), suggesting this was not an intestinal

primary, whereas cells of normal colonic crypts were positive,

serving as a positive internal control (Fig. 2C). No nuclear stain was seen in

tumoral single cells with transcription termination factor 1 (SP141

clone; Roche Diagnostics) (Fig.

2D), GATA binding protein 3 (L50-832 Clone; Zytomed Systems

GmbH) and paired box 8 (MRQ-50 clone; Cell Marque™; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) antibodies, nor in cells of normal colonic crypts;

therefore not indicating a lung, urothelial or kidney primary

(Fig. 2E). Magnification at ×200

was used.

Discussion

Globally, a total of ~10% of patients presenting

with prostate cancer are at a metastatic stage (12). A previous meta-analysis demonstrated

that the baseline presence of visceral disease is a negative

prognostic factor and the distribution of metastases markedly

influences OS (13). Most patients

with prostate cancer present with bone metastases, either with

(72.8%) or without lymph node involvement, followed by visceral

disease (20.8%) and lymph node-only disease (6.4%). Liver

metastases are associated with the shortest median OS (13.5

months), whilst lung metastases have shown an improved median OS

(19.4 months) compared with liver metastases, but worse than

non-visceral bone metastases (21.3 months). Lymph node-only disease

is associated with the longest median OS (31.6 months).

Furthermore, hazard ratios for mortality are markedly higher in men

with lung or liver metastases compared with those with bone

metastases (13). However, there is

limited data on other metastatic sites. Gandaglia et al

(8) reported that digestive

locations accounted for 2.7% of metastatic sites. Among patients

with exclusively digestive metastases, 52% had additional

concomitant metastatic sites; however, only 2.7% of patients with

digestive metastases presented a second metastatic site in bone

(8).

To the best of our knowledge, the present case

report is the 9th published case of a patient with prostate cancer

presenting with secondary digestive localization (13–21).

The majority of patients (n=7) presented with a metastatic

metachronous evolution with a long disease-free interval. Patients

presenting synchronous disease have histologically demonstrated a

more aggressive form (ISUP >4, Gleason score >7) (22). The circumstances of discovering

metastatic digestive disease of prostate cancer were often noisy

digestive symptoms, more closely resembling those of a primary

colorectal origin. Only a few patients reported urinary symptoms,

which, from an endoscopic perspective, could initially suggest a

primary digestive pathology. Nevertheless, immunohistochemical

analysis is essential, particularly with specific markers of

prostate cancer such as NKX3.1.

The present clinical case is one of the only cases

with molecular biology data at the tissue, germinal and ctDNA

levels. In the present case, no anomalies were identified. However,

Swami et al (23) presented

differences in the genomic, transcriptomic and immune landscape of

prostate cancer based on the site of metastasis at the American

Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium

(2024). Different molecular and immunological profiles between the

primary and metastatic sites were reported, explaining distinct

evolutions and providing avenues for therapeutic adaptation. For

these patients, a complete colonoscopy must be performed to assess

the volume of the disease, in addition to a bone and CT scan.

Moreover, molecular screening on the metastatic site should be

performed.

The management of patients with prostate cancer has

markedly evolved in previous years, with the addition of a

second-generation hormonal therapy +/- docetaxel to ADT. However,

to date, no study has included this digestive metastatic site, to

the best of our knowledge, and therapeutic management remains

challenging. Data from the literature suggests a notable role for

local treatment +/- ADT in patients with secondary digestive

localization (13–21).

Similar to the patient in the present case report,

patients with digestive localization, according to the CHAARTED

classification, are classified as high volume (visceral metastases

and/or 4 bone metastases, including at least one outside the pelvis

and spine) (2). Furthermore, if

there is the presence of >3 bone lesions and/or Gleason >7,

the patient will be classified as high risk, according to the

LATITUDE classification. The patient in the present case report was

thus classified as high volume and high risk, with >4 bone

locations, a Gleason score of 9 and the presence of visceral

localization (2,3).

The high-risk classification of the patient

according to the CHAARTED and LATITUDE criteria warranted a more

aggressive treatment approach (2,3). Based

on the data from STAMPEDE and PEACE 1, primary radiotherapy does

not provide a survival benefit to high risk patients (7,24). The

combination of ADT + ARPI has demonstrated a survival benefit for

high risk patients regardless of the molecule used (AA,

enzalutamide, apalutamide) (2–5). The

PEACE 1 and ARASENS studies (6,7)

reported a benefit from adding docetaxel to the ADT + ARPI doublet,

which could be an option for the present patient. For the patient

in the present study, a doublet was chosen to limit side effects.

Moreover, there is no reported benefit of the triplet ADT + AA +

docetaxel in patients aged >70 years old. In addition,

considering the high metastatic volume and comorbidities of the

patient and potential side effects, the decision to avoid

chemotherapy and radiotherapy was taken to provide a tailored and

less burdensome therapeutic regimen. Despite the severe initial

prognosis of the patient, the sustained reduction of their PSA

levels markedly improved their prognosis. The use of PSA and its

reduction and duration are key tools in the management of the

patients.

At present, the triplet treatment with the

combination of ADT + darolutamide + ARPI could be considered, as it

has demonstrated a benefit in the high-volume hormone-sensitive

metastatic population, with this benefit maintained in patients

aged >70 years old (6). However,

this treatment option was not available at the time of the present

case.

Despite the valuable insights gained from the

present study, the small sample size, unique case presentation and

absence of randomized controlled trials limit the generalizability

of the findings, highlighting the need for larger studies and

further research to validate and expand upon these conclusions.

In conclusion, although digestive localizations are

infrequent, understanding their management is essential to maintain

the benefit in OS. Thus, a complete colonoscopy is an indispensable

complementary examination for diagnosis. Therapeutic options are

based on ADT + ARPI +/- docetaxel, considering the clinical status

and history of the patient. There is currently no role for local

treatment of prostate cancer with secondary digestive localization.

A molecular biology examination should also be performed to inform

the choice between doublet and triplet therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MAA, ATN, EP, JLL, DL, CH, MP, HP, ALR, AB, MD, HV

and AS made substantial contributions to the conception of the

work; the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data; or the

creation of new software used in the work; drafted the work; and

approved the submitted version; and agreed to be personally

accountable for the their own contributions. MA and CH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the local ethics

committee, Bégin Military Hospital and the national ethics

committee, Sud-Ouest et Outre-Mer II (approval no.

2020-A0003138).

Patient consent for publication

The patient, as a participant in a larger study,

provided written informed consent for the publication of their data

and gave additional verbal consent specifically for the publication

of the present case report, including the use of their data and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G,

Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney MM, et

al: Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate

cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:737–746. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N,

Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, Özgüroğlu M, Ye D, Feyerabend S,

Protheroe A, et al: Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients

with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive

prostate cancer (LATITUDE): Final overall survival analysis of a

randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20:686–700.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP,

Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, Alcaraz A, Alekseev B, Iguchi

T, Shore ND, et al: ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of

androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men

with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol.

37:2974–2986. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, Chung BH,

Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, Juárez A, Merseburger AS,

Özgüroğlu M, Uemura H, et al: Apalutamide in patients with

metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: Final survival

analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J

Clin Oncol. 39:2294–2303. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Smith MR, Hussain M, Saad F, Fizazi K,

Sternberg CN, Crawford ED, Kopyltsov E, Park CH, Alekseev B and

Montesa-Pino Á: Darolutamide and survival in metastatic,

hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 386:1132–1142.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fizazi K, Foulon S, Carles J, Roubaud G,

McDermott R, Fléchon A, Tombal B, Supiot S, Berthold D, Ronchin P,

et al: Abiraterone plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation

therapy and docetaxel in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive

prostate cancer (PEACE-1): A multicentre, open-label, randomised,

phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet. 399:1695–1707.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J,

Trudeau V, Shariat SF, Kim SP, Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Briganti A,

Trinh QD, et al: Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with

prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. Prostate. 74:210–216.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gurel B, Ali TZ, Montgomery EA, Begum S,

Hicks J, Goggins M, Eberhart CG, Clark DP, Bieberich CJ, Epstein JI

and De Marzo AM: NKX3.1 as a marker of prostatic origin in

metastatic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 34:1097–1105. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sweeney CJ, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, Begbie

S, Cheung L, Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Frydenberg M, Horvath LG and

Joshua AM: Testosterone suppression plus enzalutamide versus

testosterone suppression plus standard antiandrogen therapy for

metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (ENZAMET): An

international, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

24:323–334. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

National Cancer Institute, . Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). 2017.

|

|

12

|

Jegu J, Tretarre B, Velten M, Guizard AV,

Danzon A, Buemi A, Colonna M, Kadi-Hanifi AM, Ganry O, Molinie F,

et al: Prostate cancer management and factors associated with

radical prostatectomy in France in 2001. Prog Urol. 20:56–64.

2010.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, Zhou H, Solomon

NC, Fizazi K, Tangen CM, Rosenthal M, Petrylak DP, Hussain M, et

al: Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on

overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer.

J Clin Oncol. 34:1652–1659. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vaghefi H, Magi-Galluzzi C and Klein EA:

Local recurrence of prostate cancer in rectal submucosa after

transrectal needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy. Urology.

66:8812005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Venara A, Thibaudeau E, Lebdai S, Mucci S,

Ridereau-Zins C, Azzouzi R and Hamy A: Rectal metastasis of

prostate cancer: About a case. J Clin Med Res. 2:137–139.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Morita T, Meguro N, Tomooka Y, Maeda O,

Saiki S, Kuroda M, Miki T, Usami M and Kotake T: Rectal metastasis

of prostatic cancer causing annular stricture: A case report.

Hinyokika Kiyo. 37:295–298. 1991.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tunio MA, Agamy AM, Fenn N, Hanratty D and

Williams NW: An unusual delayed rectal metastasis from prostate

cancer masquerading as primary rectal cancer. Int J Surg Case Rep.

100:1077322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nwankwo N, Mirrakhimov AE, Zdunek T and

Bucher N: Prostate adenocarcinoma with a rectal metastasis. BMJ

Case Rep. 2013:bcr20130095032013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Abbas TO, Al-Naimi AR, Yakoob RA, Al-Bozom

IA and Alobaidly AM: Prostate cancer metastases to the rectum: A

case report. World J Surg Oncol. 9:562011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Liu ZH, Li C, Kang L, Zhou ZY, Situ S and

Wang JP: Prostate cancer incorrectly diagnosed as a rectal tumor: A

case report. Oncol Lett. 9:2647–2650. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Dulskas A, Cereska V, Zurauskas E,

Stratilatovas E and Jankevicius F: Prostate cancer solitary

metastasis to anal canal: Case report and review of literature. BMC

Cancer. 19:3742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B,

Srigley JR and Humphrey PA; Grading Committee, : The 2014

International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus

conference on gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: Definition of

grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg

Pathol. 40:244–252. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Swami U, Nazari S, Gebrael G, Elliott A,

Bagrodia A, Puri D, Nabhan C, McKay RR, Antonarakis ES and Agarwal

N: Differences in genomic, transcriptomic, and immune landscape of

prostate cancer (PCa) based on site of metastasis (mets). J Clin

Oncol. 42:212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Attard G, Murphy L, Clarke NW, Cross W,

Jones RJ, Parker CC, Gillessen S, Cook A, Brawley C, Amos CL, et

al: Abiraterone acetate and prednisolone with or without

enzalutamide for high-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer: A

meta-analysis of primary results from two randomised controlled

phase 3 trials of the STAMPEDE platform protocol. Lancet.

399:447–460. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|