Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor in

female patients (1); according to

data from the World Health Organization, in 2020, there were ~2.26

million new breast cancer cases worldwide, threatening their lives

by affecting both physical and psychological health (2,3). The

latest advancements in treatment have mainly focused on the use of

molecular biology and immunological approaches to develop highly

targeted therapies for different types of breast cancer. This has

been explored through inhibiting specific targets or molecules that

promote tumor progression (4). Due

to the presence of different subtypes and differences in treatment

modalities (5), it is common to

categorize breast cancers on the basis of expression patterns of

three receptors: Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human

epidermal growth factor-2 (HER2) receptor, or as a triple-negative

breast cancer (TNBC). Most patients suffer from estrogen

receptor-positive breast cancers; the majority of patients have

estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, accounting for >70% of

all cases (6), in vitro

models are primarily represented by MCF-7 cells. Endocrine therapy,

usually using tamoxifen (TAM), has been shown to markedly prolong

the survival of patients with breast cancer (7). TNBC, a subtype in which estrogen,

progesterone and HER2 receptors are not expressed, accounts for

12–17% of invasive breast cancers (8,9) and

83% of total mortalities (10).

Compared with other breast cancer subtypes, triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC), represented by the MDA-MB-231 cell line in

vitro, has the highest recurrence and metastasis rates and is

exemplified by development at a young age and a poor prognosis

(11). Currently, there are no

effective treatments other than surgery, radiation and chemotherapy

therapy. Doxorubicin (DOX) is widely used to treat TNBC (12), as a chemotherapy drug, therefore in

the present study, both TAM and DOX were chosen to induce apoptosis

in breast cancer cells.

Multiple transcription factors have been reported to

regulate proliferation and apoptosis in breast cancer cells

(13,14). These transcription factors achieve

these effects by controlling protein translation and degradation.

Consequently, interactions between proteins and transcription

factors play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of

breast cancer (15,16). The transcription factor FoxO3a has

potent tumor suppressor effects in a variety of malignancies, such

as gastric, prostate and colorectal cancers (17–19).

RNA interference targeting FOXO3a was used to measure the impact of

simvastatin on FOXO3a-expressing cells (20). Therefore, the present study

performed FoxO3a knockdown. Previous studies have shown that low

expression of FoxO3a could inhibit the apoptosis of tumor cells

(21,22).

The application of proteomics allows for the

discovery of additional proteins, which can provide insight into

the mechanisms of disease and identify specific biomarkers that

induce apoptosis. In the present study, small interfering

(si)RNA-negative control (NC) and si-FoxO3a cel ls from two types

of breast cancer were treated with TAM and DOX to construct

estrogen-dependent and triple-negative si-FoxO3a breast cancer cell

lines. The aims were to validate the effect on drug-induced

apoptosis in breast cancer cells after interference with FoxO3a,

analyze the signaling pathways that serve a role in the regulation

of apoptosis after treatment via proteomics; and validate the

signaling pathway-associated differentially expressed proteins

(DEPs). The present study hypothesizes that targeting regulatory

proteins in protein digestion and absorption signaling pathway

could lead to timely detection of breast cancer metastasis and

improve treatment outcomes.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Breast epithelial cells, MCF-10A, and breast cancer

cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were purchased from the Shanghai

Institute of Biological Sciences. The cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and high-glucose

DMEM (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), supplemented

with 10% FBS (EvaCell) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Cytiva)

at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

A total of 2.5×105 cells/well (MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231) were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated at 37°C

for 24 h. Liposomal transfection of siRNA was performed the

following day when the cell density reached 60% using the

transfection reagent Lipofectamine® 3000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 24 h at 37°C. The siRNAs were designed by our

laboratory staff and synthesized by Guangzhou Ruibo Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. In addition, 1,750 ml basal medium, 5 µl siRNA, 5 µl

transfection reagent and 240 µl serum-free medium was added to each

well. At 8 h after transfection in serum-free medium, the medium

was replaced with complete medium and the cells were incubated for

a further 24 h. si-FoxO3a target sequence was

5′-AATGATGGGGGGCTGACTGAAA-3′, synthesized by RiboBio Biotechnology,

the initial siRNA transfection concentration is 50 nmol.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted with

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for reverse transcription (SureScript™ First-Strand cDNA;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The quality and concentration of

the extracted RNA was analyzed using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop

Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse

transcription conditions are as follows: 25°C 5 min, 42°C 15 min,

85°C 5 min. Blaze Taq SYBR® Green qPCR Mix 2.0 (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for RT-qPCR experiments.

Thermocycling conditions: 95°C pre-denaturation for 10 min, 95°C

denaturation for 15 sec, 60°C annealing for 1 min, 72°C extension

for 30 sec, repeated for 40 cycles, with three replicate wells per

sample, and the transcript levels were normalized to those of

GAPDH. Gene expression levels were analyzed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (23). The

following primers were used: GAPDH-forward (F):

5′-ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC-3′; GAPDH-reverse (R):

5′-TGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTT-3′; FoxO3a-F: 5′-CGGACAAACGGCTCACTCT-3′;

FoxO3a-R: 5′-GGACCCGCATGAATCGACTAT-3′;

Western blotting

Experiments were performed with MCF-7/MDA-MB-231

si-NC and si-FoxO3a cells treated with TAM/DOX for 24 h, which were

both washed twice with PBS and lysed on ice for 30 min with the

addition of lysis buffer(Beyotime Biotechnology). Centrifugation

was performed at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was

collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the

Enhanced BCA Protein Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). A total of 5 µg/lane protein per well, separated by

SDS-PAGE (5% concentrating and 5% separating gel), transferred to a

PVDF membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following

primary antibodies: GAPDH (1:1,000; cat. no. P04406; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), FoxO3a (1:1,000; cat. no. O43524; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), trophoblast glycoprotein (TPBG; 1:1,000; cat.

no. Q13641; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), sodium-coupled

neutral amino acid symporter 2 (SLC38A2; 1:1,000; cat. no. DF4673;

Affinity Biosciences), asparagine synthetase (ASNS; 1:1,000; cat.

no. P08243; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), phosphorylated

(p)-FOXO3a (1:1,000; cat. no. O43524; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.) and zyxin (ZYX; 1:1,000; cat. no. Q15942; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.). The membrane was washed three times, incubated

with a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. 210830803;

Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room

temperature, and the results were detected with a chemiluminescent

ECL detection system(Thermo Fisher). The experiments all contained

three independent biological replicates, and three technical

replicates were used for each biological replicate to ensure data

reliability.

Water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1)

assay

A total of 6×103 cells per well were

seeded in a 96-well plate, and three replicate wells were used for

each group. When the density reached 80–90%, the culture medium was

discarded, and 100 µl different concentrations of TAM/DOX were

added. Each well had 10 µl WST-1 reagent added 24 h after the drug

treatment, the reaction was carried out at 37°C for 15–30 min and

the optical density value was assessed at the wavelength of 460 nm.

The experiments all contained three independent biological

replicates, and three technical replicates were used for each

biological replicate to ensure data reliability.

Cell apoptosis

A total of 2.5×105 cells were seeded in a

6-well plate and digested with trypsin. Following centrifugation

for 10 min at 4°C, 12,000 × g the cells were resuspended in PBS,

centrifuged again and then, according to the protocol of the

FITC-coupled Annexin-V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences),

each sample was mixed with 490 µl 1X binding buffer and 5 µl each

of FITC and PI dyes. The cells were stained for 20 min at room

temperature, protected from light and assessed using flow cytometry

within 1 h. There were 10,000 cells in each group. The experiments

all contained three independent biological replicates, and three

technical replicates were used for each biological replicate to

ensure data reliability.

Hoechst staining

Hoechst 33342 is a dye that penetrates cell

membranes, causing living cells to fluoresce blue. When apoptosis

occurs with inconsistent nuclear fragmentation; the brightness of

the blue fluorescence is increased. A total of 10,000 si-NC and

si-FoxO3a cells were cultured for 6–8 h, the cells were treated

with the drugs for 24 h, the supernatant was discarded and the

cells were washed twice with precooled PBS. Hoechst 33342 staining

solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added, and the cells

were stained for 15–20 min at room temperature, before being washed

three times with precooled PBS at 4°C for 5 min each. The

fluorescent intensity of the cells was observed using fluorescence

microscopy. The experiments all contained three independent

biological replicates, and three technical replicates were used for

each biological replicate to ensure data reliability.

Wound healing assay

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded into 6-well

plates (3×105 and 5×105/well, respectively),

and the transfection and drug treatments were carried out as

aforementioned. After the cells grew to 90% confluence, a sterile

tip was used to scratch the cells. Cell debris was removed by

washing with PBS and the cells were cultured in serum-free medium

for 24 h. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope

(magnification, ×10) at 0 and 24 h after scratching. The relative

size of the wound area from 0 to 24 h was measured using Image J

software(National Institutes of Health; version no. 1.47) to

calculate the cell migration rate. The experiments all contained

three independent biological replicates, and three technical

replicates were used for each biological replicate to ensure data

reliability.

Proteomics processing

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells treated with TAM/DOX

drugs for 24 h were recorded as control (ctrl)-TAM and ctrl-DOX,

respectively. FoxO3a knockdown cells treated with drugs for 24 h

were recorded as si-TAM and si-DOX. After treatment, the cell

precipitate was collected, 20% trichloroacetic acid was added, the

mixture was vortexed well and the cells were left to precipitate

for 2 h at 4°C. The supernatant was removed by centrifugation at

4°C, 4,500 × g for 5 min, and the precipitate was washed with

precooled acetone 2–3 times. The precipitate was allowed to dry, a

final concentration of 200 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate was

added, the precipitate was broken by ultrasonication and it was

enzymatically digested overnight. Dithiothreitol was added to a

final concentration of 5 mM and reduced at 56°C for 30 min.

Iodine-acetyl carbamate was added to a final concentration of 11 mM

and incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The

confidence interval for the difference in the protein

quantification ratio between the si-FoxO3a and the si-NC group was

assessed as the multiplicity of differences, with a fold-change

>1.2 and P<0.05. The false discovery rate (FDR) for protein

identification and peptide-spectrum match identification in the

search database settings was 1%, revealing that different protein

networks existed in both cancer cell lines after interfering with

FoxO3a expression.

Liquid chromatography-mass

spectrometry analysis

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis was

performed by Jingjie PTM Bio-Laboratory (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd. using

positive ionization mode. The primary mass spectrometry scan range

was 400–1,200 m/z with a resolution of 60,000. The fixed starting

point for the secondary mass spectrometry scan range was 110 m/z,

with a secondary scan resolution of 15,000. Mobile phase A was an

aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile;

mobile phase B was an aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid

and 90% acetonitrile. The liquid chromatography gradient settings

were as follows: 0–68 min, 6–23%B; 68–82 min: 23–32%B; 82–86 min:

32–80%B; 86–90 min: 80%B. Flow rate maintained constant at 500

nl/min.

Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG(Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) functional enrichment analysis,

and STRING protein interactions

GO (geneontology.org) and KEGG (kegg.jp) functional

enrichment analyses were performed based on secondary

categorization and Fisher's exact test was applied to calculate the

significance P-value with the aim of determining whether DEPs were

significantly enriched in certain functional types. The FDR value

in enrichment analysis is set to 1%. Directly copy or import the

identified differentially expressed proteins into the STRING

database (cn.string-db.org).

Statistical analyses

A Student's t-test (unpaired)was used to compare

differences between two groups, and a one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test was used to compare differences between

multiple groups. Calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics

17.0 (IBM Corp.) software, with normality analysis being performed

using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Three replications were

performed for all the experiments, and the data are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Assessment of baseline expression

levels of FoxO3a and successful knockdown of FoxO3a

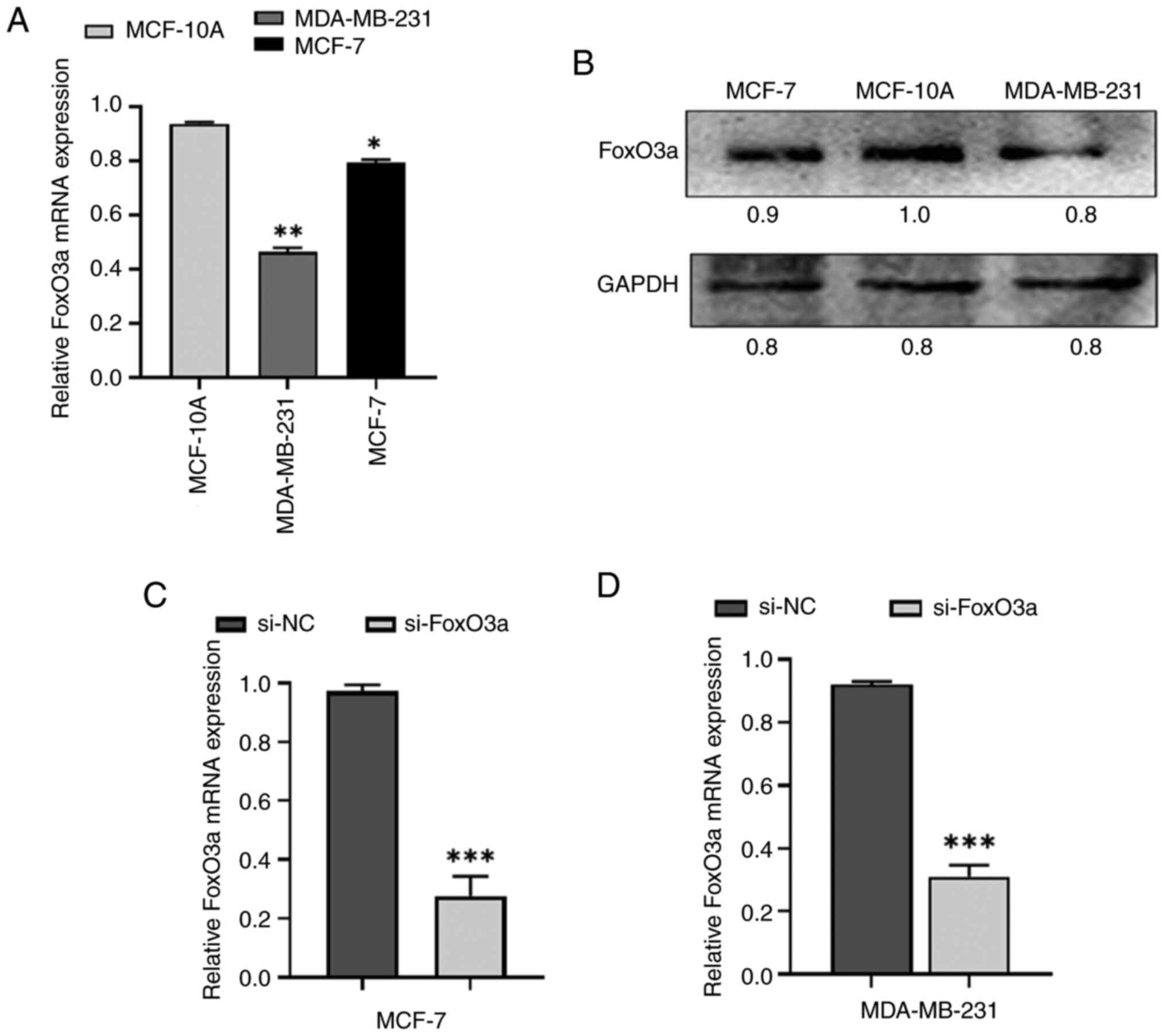

FoxO3a expression was examined in MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells using RT-qPCR and western blotting, which

demonstrated that FoxO3a levels were detected in both cell types

(Fig. 1A and B). FoxO3a was

successfully knocked down by transfection of siRNA for 24 h.

RT-qPCR was used to assess the knockdown efficiency as shown in

Fig. 1C and D.

si-FoxO3a decreases the degree of

apoptosis

Annexin V/PI double staining demonstrates that

si-FoxO3a hinders the apoptosis of breast cancer cells by antitumor

drugs

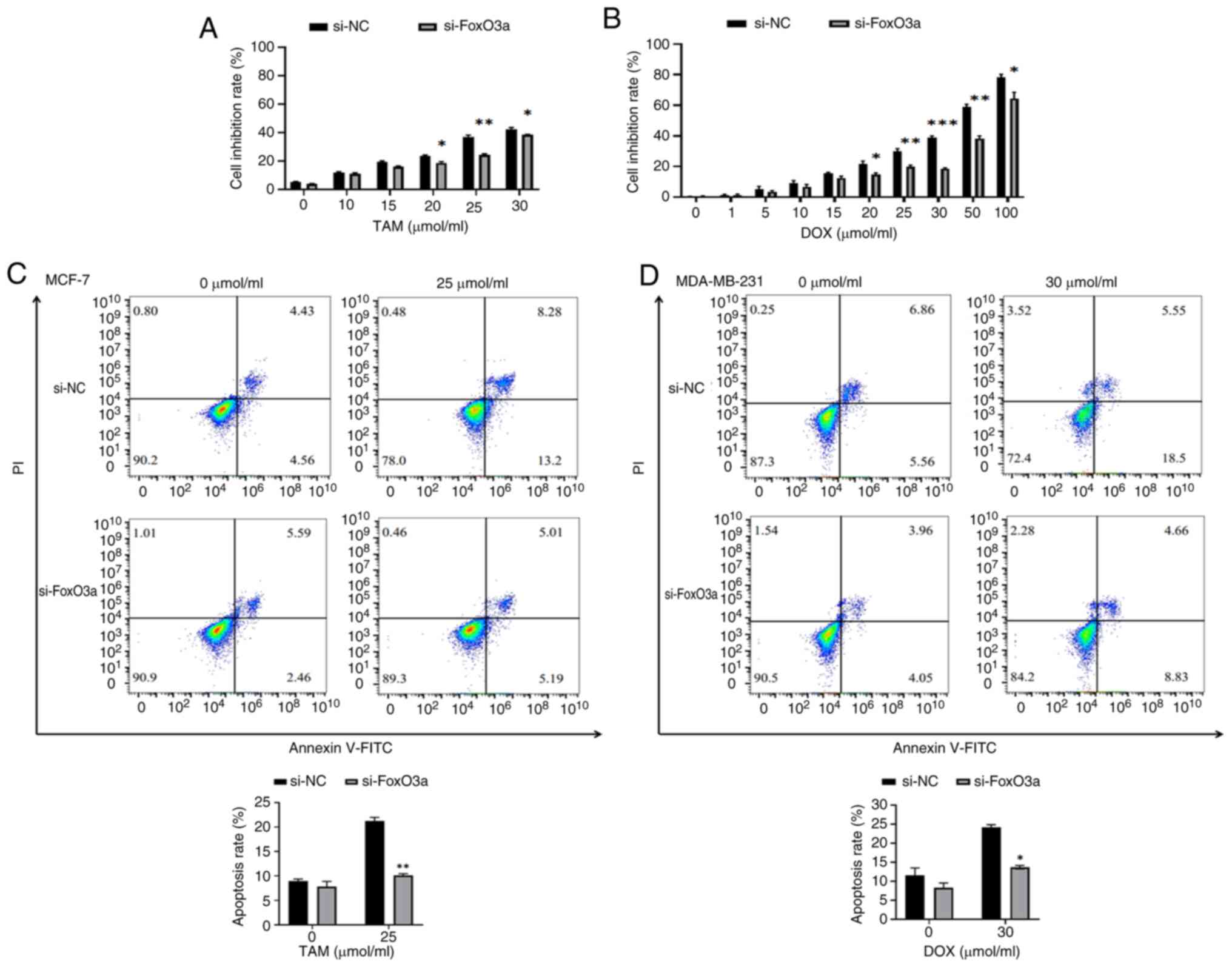

The WST-1 assay was used to determine the optimal

concentrations of TAM and DOX. This method is easy to perform,

produces stable results and has low cytotoxicity. The results of

the WST-1 assay revealed that the apoptosis rate of si-FoxO3a MCF-7

and MDA-MB-231 cells by 25 µmol/ml and 30 µmol/ml TAM and DOX

respectively, was decreased compared with the si-NC cells (Fig. 2A and B). Flow cytometry was used to

analyze the proapoptotic effects of 0 and 25 µmol/ml TAM drug

treatments for 24 h on si-NC and si-FoxO3a MCF-7 cells, and 0 and

30 µmol/ml DOX drug treatments for 24 h on si-NC and si-FoxO3a

MDA-MB-231 cells. The results (Fig. 2C

and D) revealed that the apoptosis rates of the si-NC and

si-FoxO3a MCF-7 cells were 8.95±0.04% and 7.81±1.17%, respectively,

and the apoptotic rates of si-NC and si-FoxO3a MDA-MB-231 cells

were 11.56±2.22% and 8.31±0.20%, respectively, when cultured for 24

h without treatment. The differences were not found to be

statistically significant. These findings indicate that the

transfection of siRNA had no significant effect on the level of

apoptosis in either type of breast cancer cells. By contrast, when

treated with drugs for 24 h, the apoptosis rates of the si-NC and

si-FoxO3a treated MCF-7 cells were 21.22±0.88% and 10.10±0.44%,

respectively, and the apoptosis rates of si-NC and si-FoxO3a

MDA-MB-231 cells were 24.19±0.60% and 13.67±0.35%, respectively.

The level of apoptosis in si-FoxO3a cells was significantly reduced

after treatment with the drug, demonstrating that interfering with

FoxO3a decreases the sensitivity of cancer cells to the drug.

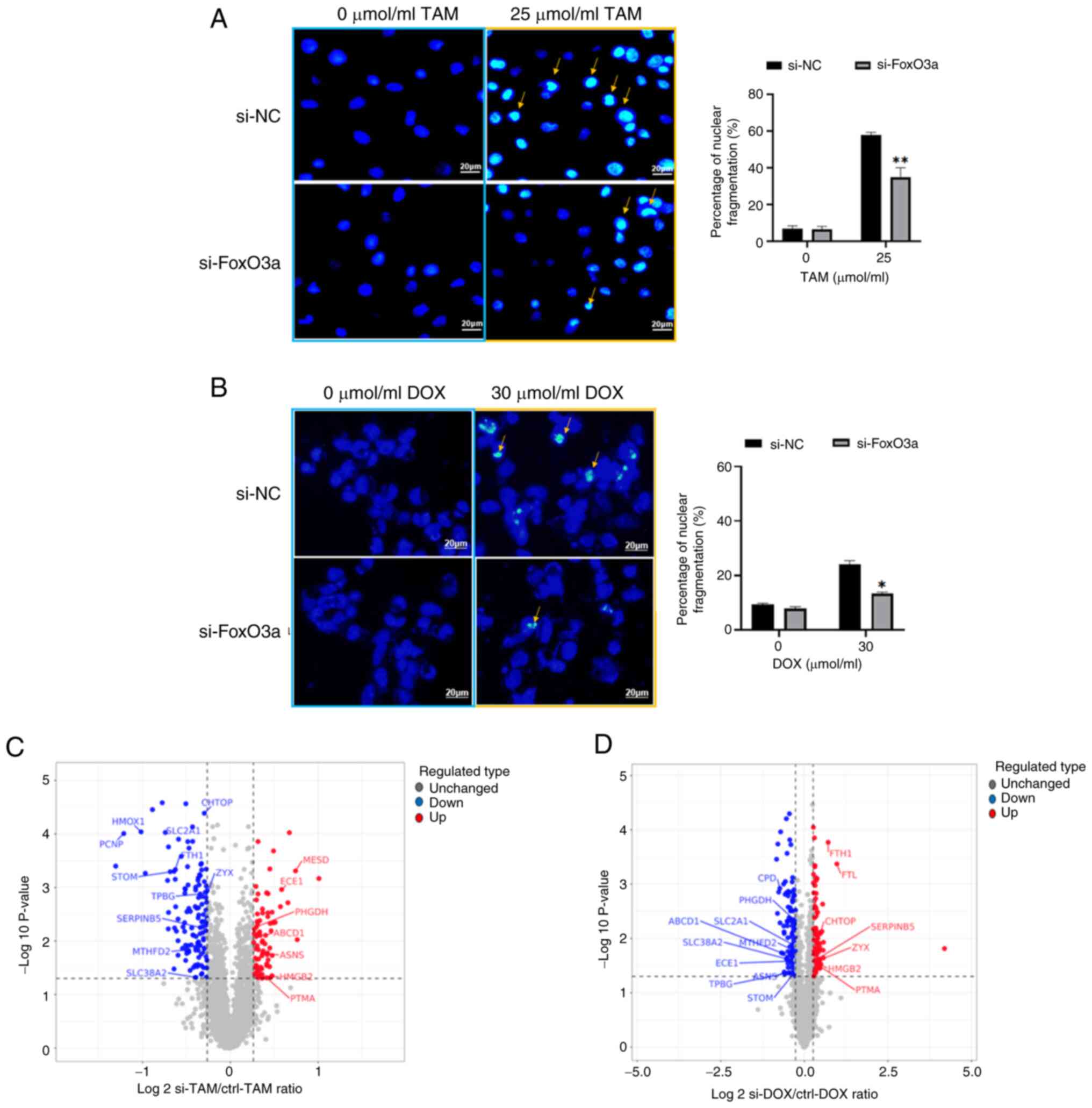

Hoechst staining demonstrates that

si-FoxO3a hinders the inhibitory effect of antitumor drugs on

breast cancer cells

si-NC cells and si-FoxO3a cells without drug

treatment presented with dark blue fluorescence staining of the

nuclei. After drug treatment for 24 h, the nuclear staining of the

two types of breast cancer cells was not homogeneous, as there was

some nuclear fragmentation, indicated by increased fluorescence

brightness. Furthermore, the levels of nuclear fragmentation in

si-FoxO3a cells were significantly reduced compared with si-NC

cells. This indicates reduced apoptosis of si-FoxO3a cells.

Quantification of the nuclear fragmentation levels is presented in

Fig. 3A and B.

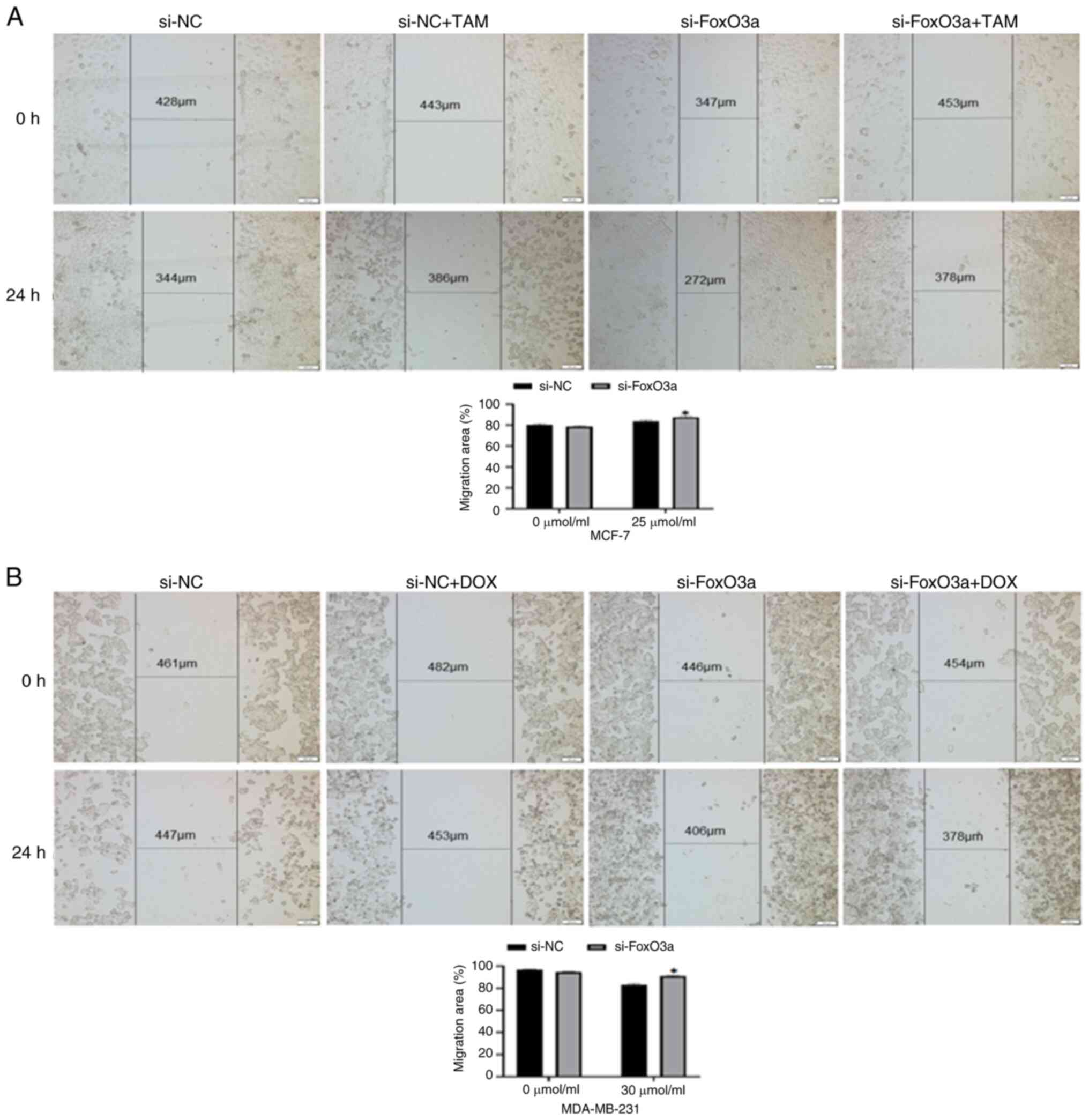

Wound healing assay demonstrates

enhanced migration of si-FoxO3a cells

Subsequently, the migration of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

si-NC and si-FoxO3a cells towards the scratched area was observed.

Without drug treatment, there was no significant difference in

migration rates between si-NC and si-FoxO3a cancer cells. Following

24 h treatment with TAM and DOX, respectively, the migration rate

of si-FoxO3a cells was significantly increased compared to the

si-NC group (Fig. 4A and B). This

indicates that FoxO3a knockdown reduces cancer cell death and

enhances their migratory capacity.

Proteomics analysis of DEPs in

si-FoxO3a

The study consisted of si-FoxO3a and si-NC groups

for label-free quantitative proteomics analysis, with three

biological replicates for each group. A screen for DEPs by the

ratio of quantitative values of DEPs in si-FoxO3a to si-NC cells

revealed 206 DEPs in MCF-7 and 207 DEPs in MDA-MB-231 cells, with

15 proteins in crossover and subcellular localization analysis. The

volcano plots (Fig. 3C and D) show

that TPBG, SLC38A2, ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 1,

endothelin converting enzyme 1, ASNS, ferritin heavy chain 1

(FTH1), ZYX, stomatin, solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1),

serpin family B member 5, prothymosin α, phosphoglycerate

dehydrogenase, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase

(NADP+ dependent) 2, high mobility group box 2 and

chromatin target of PRMT1 (CHTOP) were DEPs common to the two types

of cells after knockdown of FoxO3a. The presence of coregulatory

proteins could provide new perspectives on the treatment and

mitigation of drug resistance in both types of breast cancer.

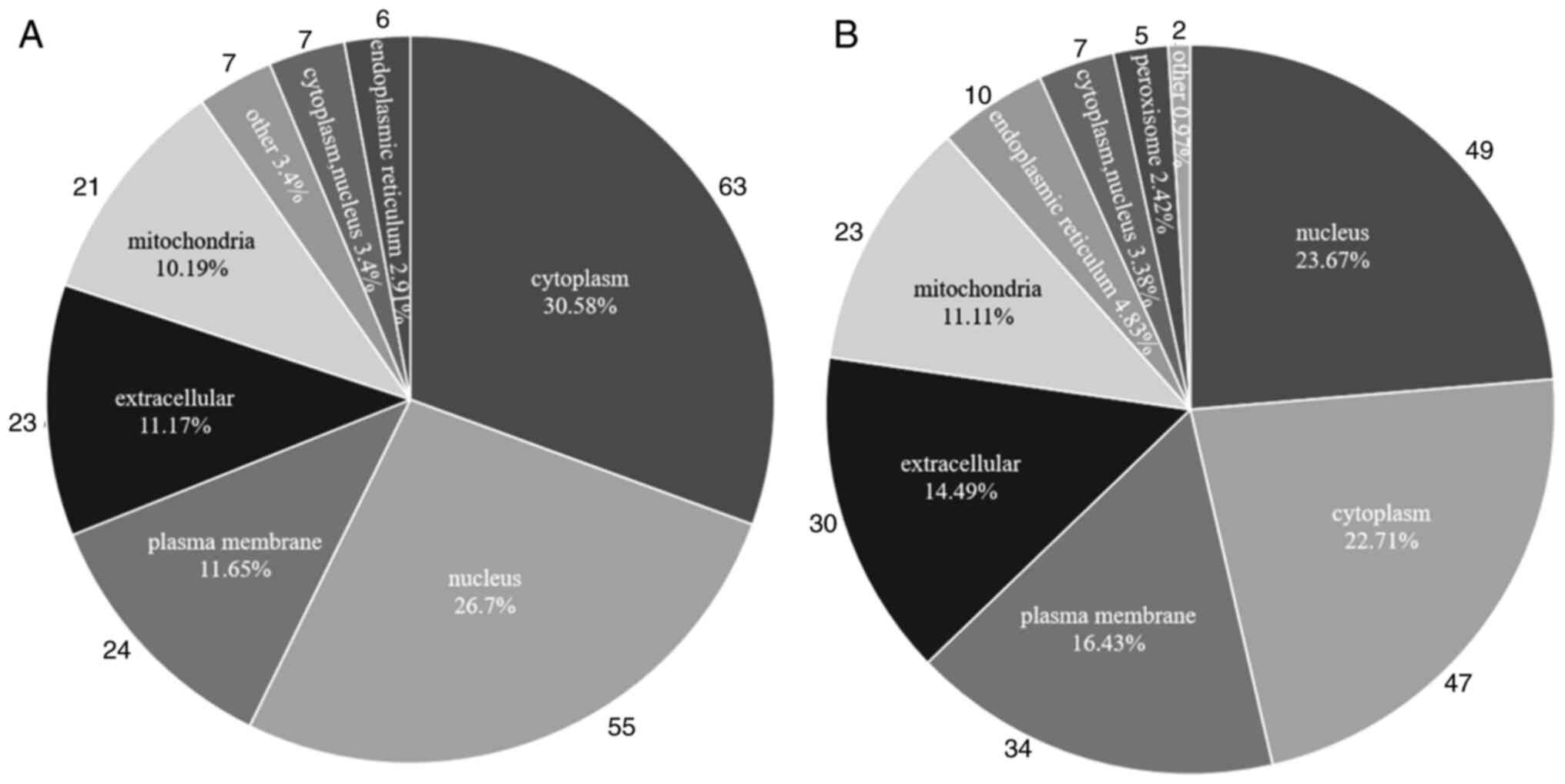

Subcellular localization analysis

Subcellular localization analysis was performed on

the identified DEPs. DEPs in MCF-7 cells were located mainly in the

nucleus (n=63), cytoplasm (n=55) and plasma membrane (n=24). DEPs

in MDA-MB-231 cells were located predominantly in the nucleus

(n=49), cytoplasm (n=47) and plasma membrane (n=34). Therefore, the

nucleus and cytoplasm are the regions where DEPs are predominantly

localized in these two types of breast cancer cells (Fig. 5A and B). This is a major region of

protein synthesis and energy transfer, therefore alterations of

proteins within this region can affect the structure and biological

function of other relevant proteins and thus regulate breast cancer

progression.

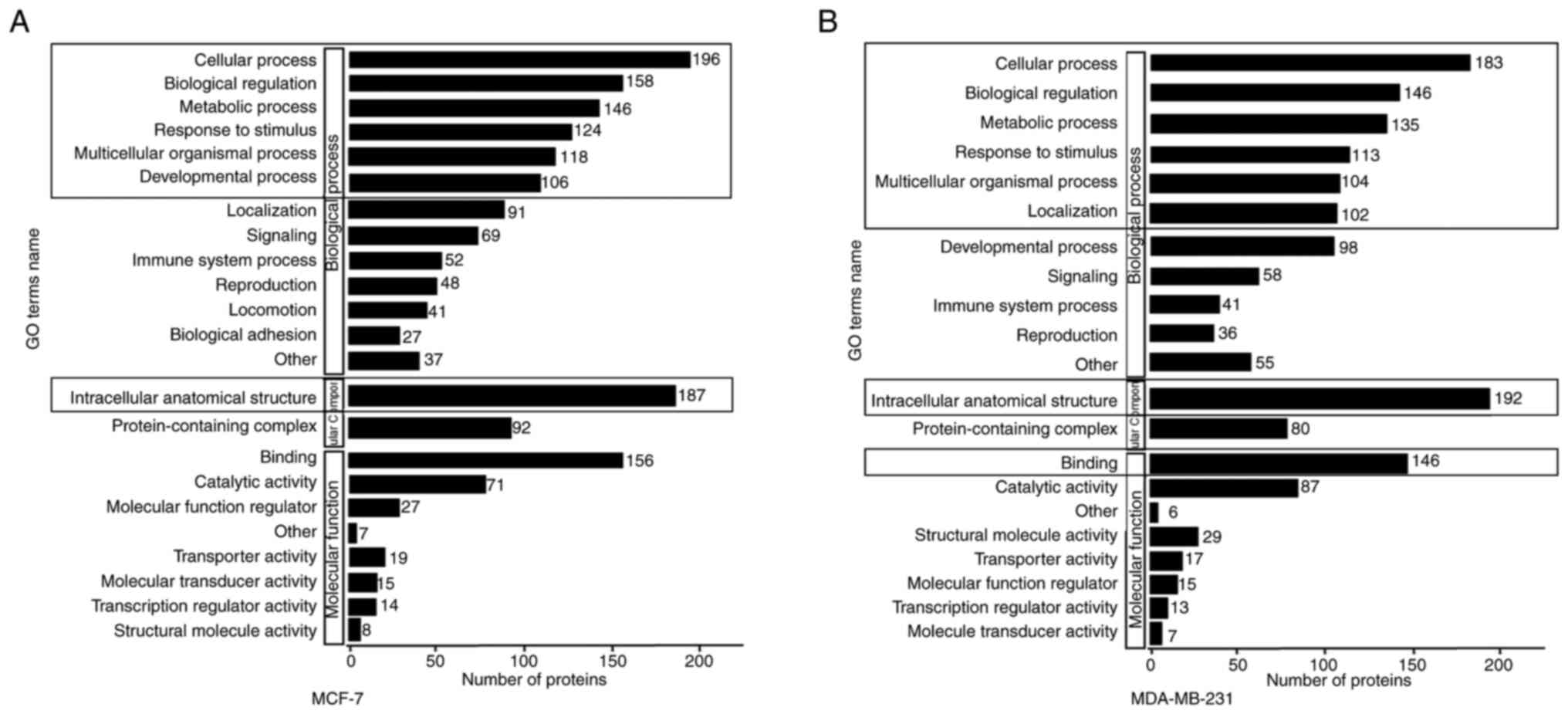

Gene Ontology (GO) secondary

classification map

The GO database (geneontology.org) is designed to

qualify and characterize gene and protein functions in three

categories: Biological process (BP), molecular function (MF) and

cellular component (CC). The y-axis represents the GO

classification, and the x-axis represents the number of proteins.

Fig. 6A and B shows the involvement

of >100 differentially expressed upregulated and downregulated

proteins in each of the three major classifications of the GO

database. The DEPs of the two breast cancer cell lines coregulate

BP processes such as ‘cellular process’, ‘biological regulation’,

‘metabolic process’, ‘response to stimulus’ and ‘multicellular

organismal processes’. These proteins are primarily localized to

the ‘intracellular anatomical structure’ and perform the MF of

‘binding’ (Fig. 6A and B).

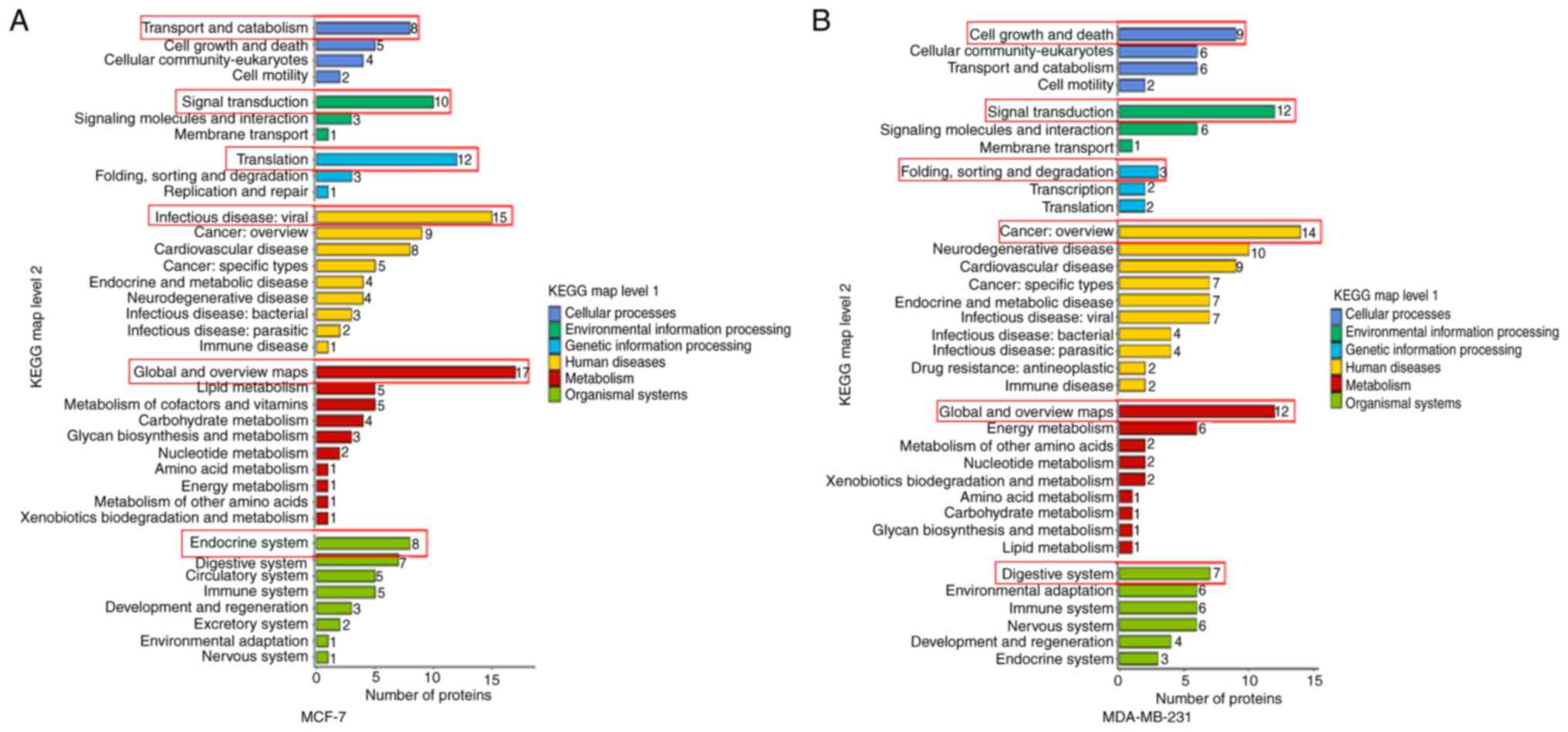

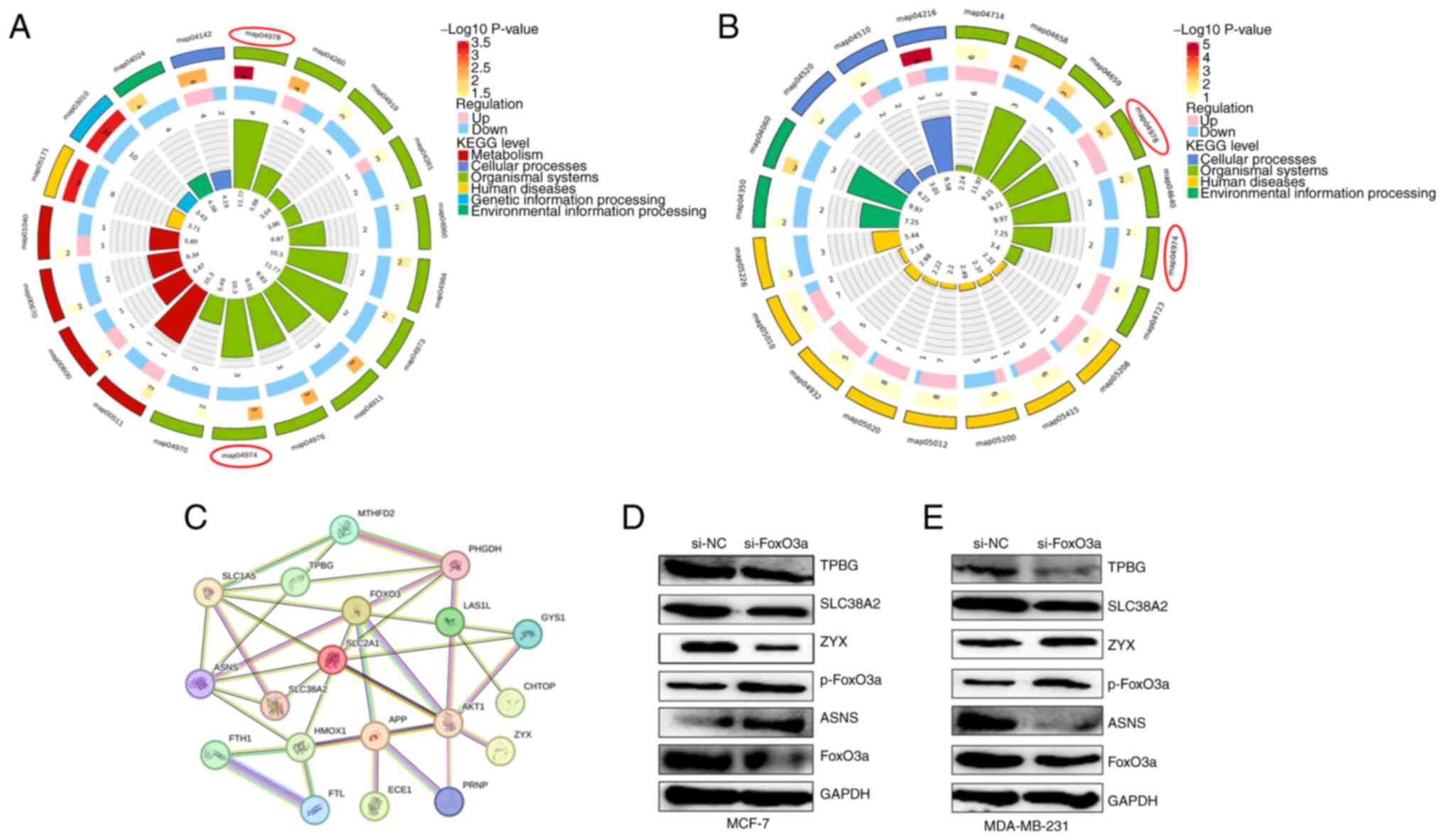

KEGG secondary classification map

As shown in Fig. 5,

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cellular DEPs share common BPs and functions

across multiple KEGG secondary classifications. Most of these DEPs

were involved in the CP of ‘transport and catabolism’ and ‘cell

growth and death’; ‘signal transduction’ in EIP, suggesting a close

relationship with signaling pathways; ‘translation’ and ‘folding,

sorting and degradation’ in GIP, suggesting an association with

protein structure and function; ‘infectious disease: viral’ and

‘cancer: overview’ in HD; ‘global and overview maps’ in metabolism;

and the ‘endocrine system’ and ‘digestive system’ in OS (Fig. 7A and B). The description involved

the process of protein digestion and absorption.

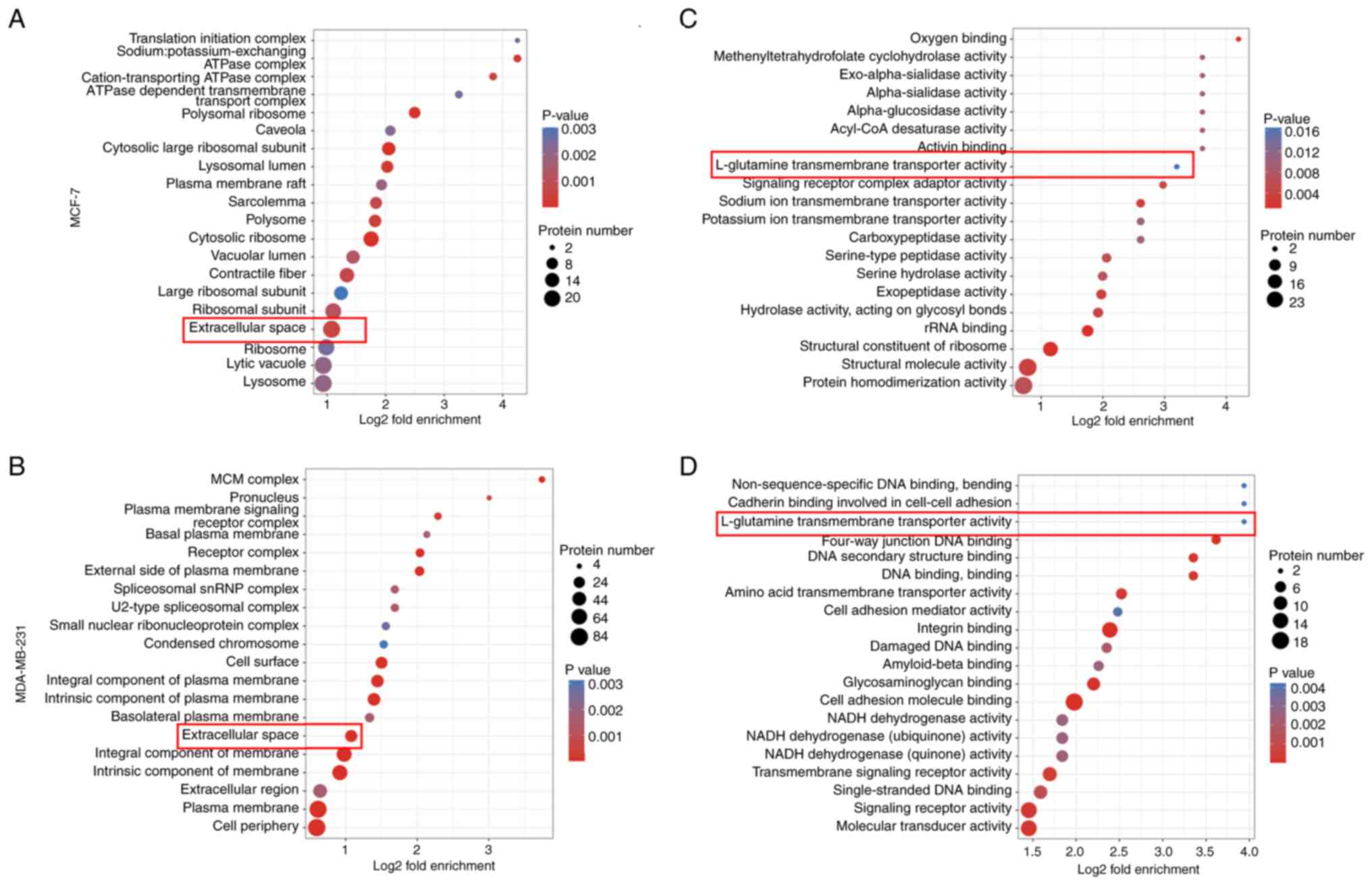

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis

To understand the functions of the DEPs, the GO

database was used to classify the enrichment of the screened DEPs.

The DEPs identified in MCF-7 cells were enriched mainly at the BP

level in ‘ribosome biogenesis’ and ‘protein localization to the

membrane’. The BP process of DEPs identified in MDA-MB-231 cells

was enriched mainly in the ‘cell surface receptor signaling

pathway’ and ‘regulation of the defense response’. Notably, the

common molecular functions of DEPs in both breast cancer cell lines

at the CC and MF levels, are mainly seen in the ‘extracellular

space’ and ‘L-glutamine transmembrane transporter activity’

(Fig. 8A-D). This suggests that

there are similar signaling pathway functions of the DEPs of two

si-FoxO3a breast cancer cell types and they are associated with

amino acid transport.

The results of KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated

that DEPs in two si-FoxO3a breast cancer cell lines after treatment

with two drugs were enriched mainly in the ‘map04974 protein

digestion and absorption’ and ‘map04978 mineral absorption’

signaling pathways (Fig. 9A and B).

Considering the notable role that protein levels serve in the

development of breast cancer, and the combined subcellular

localization analysis and GO enrichment results, primarily

targeting the activity of ‘L-glutamine transmembrane transporter

activity’, demonstrated the role of transport proteins, the present

study focused on the preceding signaling pathway (map04974).

FoxO3a regulates protein digestion and

absorption signaling pathway-related proteins

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network mapping

was performed for common DEPs and DEPs involved in apoptotic

processes, together with FoxO3a, in two types of breast cancer

cells. The findings indicated that the DEPs are closely related to

each other and are involved in the regulation of protein digestion

and absorption signaling pathways and apoptotic processes.

-Therefore, DEPs identified in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells involved

in the protein digestion and absorption signaling pathway and

apoptosis, were mapped together with FoxO3a. This was performed

using the STRING database to identify potential relationships

between the proteins (Fig. 9C).

Western blotting for verification of

the DEPs

The DEPs identified in the two types of breast

cancer cells were validated using western blotting, which revealed

that TPBG were downregulated and that p-FoxO3a levels were

increased in si-FoxO3a cells compared with si-NC cells. ASNS was

upregulated in MCF-7 cells and downregulated in MDA-MB-231 cells

treated with si-FoxO3a. In addition, ZYX was upregulated in MCF-7

cells, and downregulated in MDA-MB-231 cells. The validation

results were consistent with the proteomics results (Fig. 9D and E).

Discussion

Breast cancer, a malignant tumor with a high

incidence and mortality rate, is a serious threat to women's lives

and health (24). Drug resistance,

recurrence and metastasis affect its treatment and prognosis. Thus,

the search for reliable molecular markers can aid in the

implementation of targeted therapy strategies for breast cancer, to

overcome resistance to existing chemotherapeutic agents. The

estrogen receptor antagonist TAM can be used as a first-line

therapeutic agent as ~70% of breast cancers are estrogen

receptor-positive. DOX is one of the most active agents against

metastatic breast cancer cells, especially TNBC, and targeting

tumor cells by loading DOX-carrying liposomes onto the surface of

macrophages can enhance antitumor immune responses (25). Some side effects are associated with

prolonged drug use, and numerous efforts have been made by

researchers to mitigate these effects and improve their efficacy

(26). Existing studies have

demonstrated that the sirtuin 1/AKT pathway can overcome DOX

treatment resistance (27).

Exploring signaling pathways may be an effective approach to

improving drug efficacy. FoxO3a has gradually attracted the

attention of researchers as a transcription factor that has tumor

suppressor potential and is involved in multiple signaling

pathways. We have previously demonstrated its notable regulatory

role in a variety of malignant tumors (28), mainly involving regulating BPs such

as apoptosis, autophagy, DNA damage repair and angiogenesis to

influence tumor progression (29–31).

Our previous experiments revealed that FoxO3a can be altered during

drug-induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells (21). Therefore, the present study analyzed

the changes in signaling pathway proteins that occur when TAM and

DOX cause apoptosis in cancer cells. This was performed using

proteomic analysis of si-FoxO3a treated cells to identify the

metastatic process and provide a scientific basis for overcoming

therapeutic resistance.

FoxO3a expression was assessed in two breast cancer

cell lines before being successfully knocked down and evaluated

using RT-qPCR. Control and FoxO3a knockdown cell models of

estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells and triple-negative MDA-MB-231

cells, were denoted as si-NC and si-FoxO3a, respectively. The

concentrations of 25 and 30 µmol/ml for TAM and DOX, respectively,

were determined using a WST-1 assay. The results demonstrated that

si-FoxO3a cells were more resistant to drug-induced apoptosis in

breast cancer cells compared with the si-NC cells, suggesting that

interference with FoxO3a can reduce cancer cell death and increase

their migration rate. The upper right quadrant of the flow

cytometry results may reflect a mixture of late apoptotic cells and

necrotic cells. Therefore, the present study further verified the

level of apoptosis using Hoechst staining, indicating the FoxO3a

transcription factor promotes drug-induced apoptosis in breast

cancer cells. This should be validated using FoxO3a overexpression

vectors in the future.

A study by Li et al (32) demonstrated that FoxO3a can be used

as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer; therefore, the

development of FoxO3a-targeted drugs shows promise. Most of the

DEPs were localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm regions, which are

also the main regions for protein synthesis and energy transfer. GO

enrichment analysis revealed common molecular functions of DEPs in

both breast cancer cell lines at the CC and MF levels, mainly the

extracellular space and L-glutamine (Gln) transmembrane transporter

activity. These findings suggest that the DEPs are involved in the

same signaling pathways of both si-FoxO3a breast cancer cell lines

and are related to amino acid transport. This suggests modulating

associated signaling pathway proteins by knocking down FoxO3a may

be a key mechanism for drug-induced apoptosis in breast cancer

cells. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the two si-FoxO3a

breast cancer cell lines inhibited drug-induced apoptosis through

the protein digestion and absorption signaling pathway. DEPs were

selected to map the PPI network together with FoxO3a, and the

connections between the protein and FoxO3a were assessed. The

regulation of apoptosis in breast cancer cells following knock down

of FoxO3a expression may involve other or parallel pathways. As

indicated by GO and KEGG secondary classifications, differentially

expressed proteins in the two breast cancer cell lines jointly

regulate processes such as ‘biological regulation’, ‘metabolic

processes’, and ‘stimulus response’. Additionally, they are

involved in ‘translation’ and ‘folding, sorting, and degradation’

in GIP. These processes are largely unrelated to mineral

absorption, strongly suggesting an association with protein

digestion and absorption functions. Therefore, the validation of

proteins related to the protein digestion and absorption signaling

pathway was primarily focused on. DEPs TPBG, SLC38A2, ASNS, ZYX and

p-FoxO3a were selected for subsequent validation using western

blotting, which yielded results consistent with those of the

proteomic analysis. After FoxO3a is phosphorylated by kinases such

as AKT, it is translocated from the cell nucleus, leading to loss

of activity and reduced expression. At this point, p-FoxO3a levels

increase, and the AKT signaling pathway is generally activated.

After FoxO3a is phosphorylated by kinases such as AKT, it

translocated from the cell nucleus, leading to loss of activity and

reduced expression.

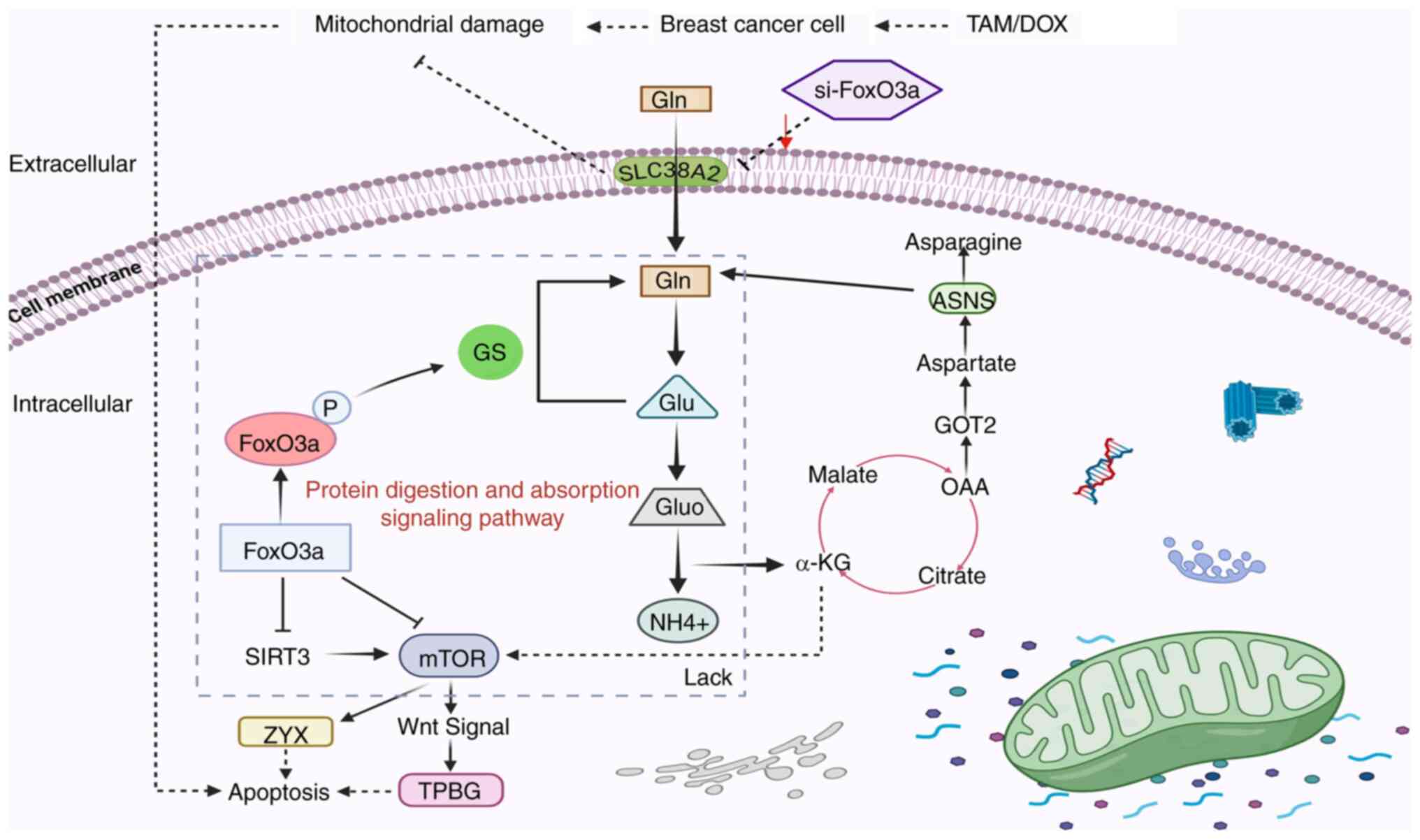

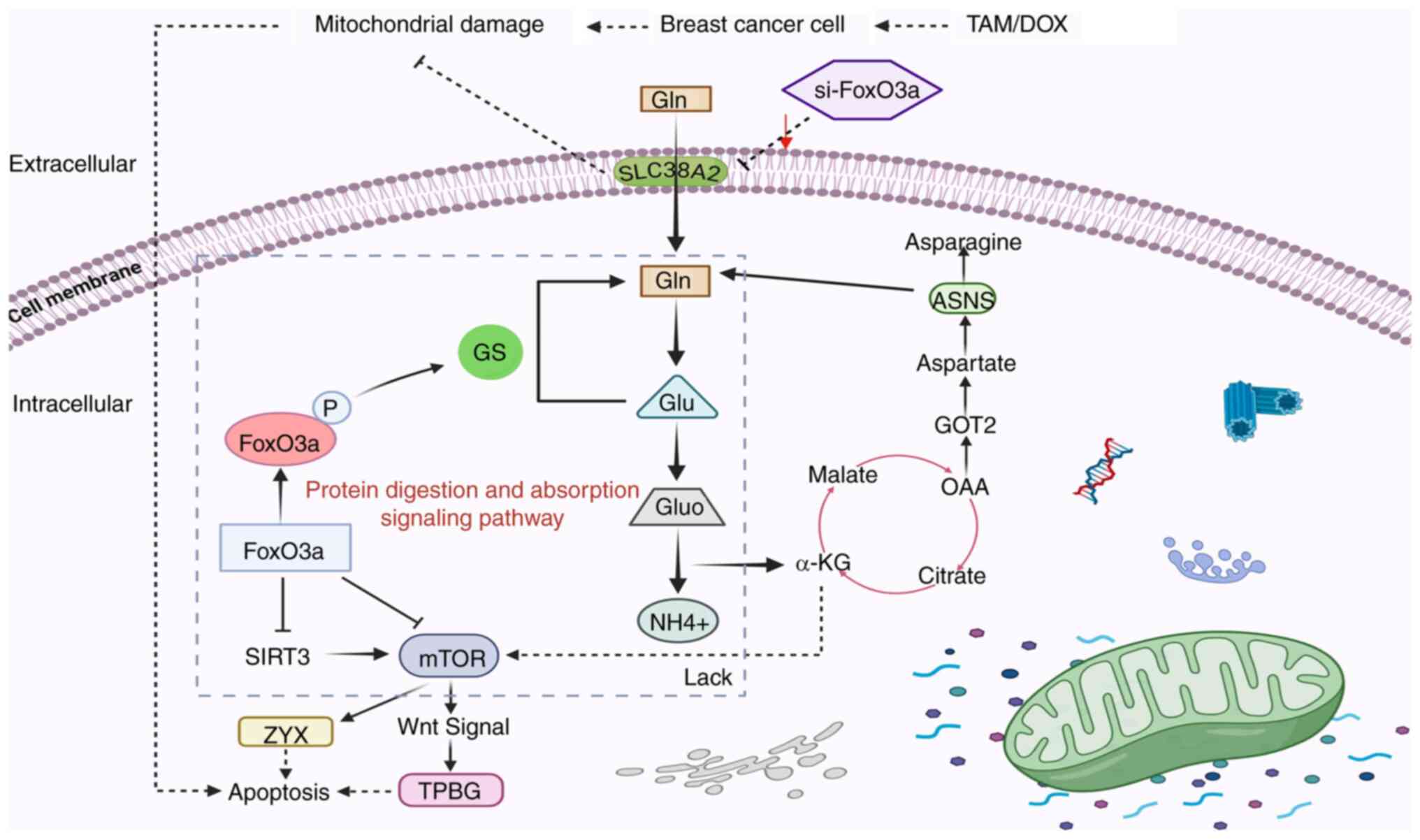

The end products of protein digestion are amino

acids, as seen in the cellular pathway diagram (Fig. 10) and the protein digestion and

absorption pathway is mainly involved in the regulation of multiple

amino acid transport proteins. The activation of cell signaling

pathways is closely related to protein hydrolysis and pro-apoptotic

processes, while the activation of protein digestion and absorption

signaling pathways is mainly related to the levels of various amino

acid transport proteins (33). TAM

and DOX can cause mitochondrial damage and thus induce apoptosis in

breast cancer cells. si-FoxO3a can impair this effect, as when Gln

is transported into the cell via SLC38A2, it inhibits the levels of

FoxO3a, research indicates that reduced FoxO3a expression leads to

excessive glutamine consumption by activated T cells, promoting the

tricarboxylic acid cycle and activating mTOR signaling to influence

transport processes (34).

Downregulating ASNS expression inhibits asparagine synthesis and

its downstream mTOR pathway to suppress TNBC progression, while

suppression of the mTOR signaling pathway affects FoxO3a levels

(35); therefore, si-FoxO3a also

affects ASNS expression by regulating the metabolism of various

amino acids. Furthermore, it may directly affect the levels of ZYX

and TPBG, and indirectly affects the levels of Wnt signaling, by

regulating mTOR (36). This

indicates a close relationship between FoxO3a and the protein

digestion and absorption signaling pathway. TPBG, SLC38A2, ASNS and

ZYX are associated with protein digestion and absorption signaling

pathways, hence these proteins were selected for validation.

| Figure 10.FoxO3a regulates the protein

digestion and absorption signaling pathway. Antitumor drugs act on

breast cancer cells, inducing mitochondrial damage and triggering

the internal apoptotic program of cancer cells. si-FoxO3a impedes

the mitochondrial damage process and affects Gln transport into the

cell by decreasing the expression of the amino acid transport

protein SLC38A2. This leads to a decrease in the conversion of Gln

to glutamate, a decrease in the tricarboxylic acid cycle

intermediate product OAA and the catalytic function of ASNS cannot

be effectively performed. α-KG deficiency decreases mTOR

expression. FoxO3a suppresses mTOR expression, thereby inhibiting

ZYX expression and promoting cancer cell apoptosis. FoxO3 also

affects TPBG levels through regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway

to promote apoptosis in cancer cells. si, small interfering;

SLC38A2, solute carrier family 38 member 2; ASNS, asparagine

synthetase; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; mTOR, mechanistic target of

rapamycin kinase; TPBG, trophoblastic glycoprotein; ZYX, zyxin;

Gluo, glutamate dehydrogenase; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; GS, glutamine

synthetase. |

Fig. 10 shows a

hypothetical model by which the aforementioned DEPs may participate

in the apoptosis process of breast cancer cells. The effect of

FoxO3a on SLC38A2 and TPBG requires further experimental

validation. TPBG is a transmembrane protein highly expressed mainly

in trophoblast and cancer cells (37). It promotes pancreatic cancer cell

metastasis through the Wnt signaling pathway, affecting the Wnt

downstream protein signaling cascade, causing increased cancer cell

migration and reducing apoptosis (38). It also induces lung cancer cell

invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by inhibiting the

levels of microRNA-15b present (39). The ectopic expression of TPBG

markedly promotes the migration and invasive ability of two TNBC

lines (40). Studies have

demonstrated that TPBG is a therapeutic target for several

anticancer drugs currently in clinical development, mainly because

of its high expression in tumors and low expression in normal

tissues (41,42).

Tumor cells usually take up large quantities of

amino acids from the extracellular environment to sustain

proliferation and metastasis. Therefore, the upregulation of

certain amino acid transporter proteins to obtain large amounts of

amino acids acts as an important source of energy for tumor cells

(43). The SLC family of proteins

contains dozens of members that transport different amino acid

types (44). The membrane

transporter protein SLC38A2 is mainly responsible for the transport

of neutral amino acids, such as Gln (33), and is involved in a range of energy

metabolism processes. Therefore, the upregulation of SLC38A2 may

help maintain enlarged cell volume to sustain proliferation, thus

reducing cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, increased SLC38A2 expression

promotes glutamine-dependent cell proliferation and is associated

with low survival and resistance to TAM in patients with TNBC

(45,46).

Additional studies have demonstrated that the

development of drugs targeting SLC38A2 may be of value in some

hormone-resistant breast cancers (45,47),

demonstrating the importance of its role in future clinical

applications. ASNS uses glutamate to provide a nitrogen source to

enable aspartic acid to synthesize asparagine (48), and studies have demonstrated that

its high expression promotes breast cancer metastasis and

colorectal cancer progression (49,50).

The downregulation of ASNS inhibits the induction of cell cycle

arrest and suppresses cell proliferation (51). With this, its expression levels are

associated with that of apoptosis, thus harboring the potential to

serve as a prognostic marker for breast cancer (52). ASNS inhibition is essential for

targeting asparagine metabolism in cancer (53). Previous studies have demonstrated

that elevated asparagine levels catalyzed by ASNS are key for

breast cancer metastasis (53,54).

Inhibition of the Gln-associated pathway does not reduce the

viability of all cancer cell lines, even in Gln-dependent TNBC cell

lines (55). Therefore, the low

expression of ASNS in si-FoxO3a MDA-MB-231 cells may be due to the

substitution of other amino acids for Gln, which serve a role in

maintaining the growth of breast cancer cells, resulting in reduced

levels of ASNS. This is a hypothesis; therefore, further

verification is ultimately required.

ZYX is mainly responsible for the interaction

between cells and the extracellular matrix and is involved in the

organization and regeneration of the cytoskeleton. It is also

involved in in the regulation of adhesion-mediated extracellular

matrix signaling (56) to influence

the downstream pathways related to cell migration, invasion and

apoptosis. ZYX functions not only as an oncogenic protein, but also

as an antitumor protein in carcinogenesis (57). On one hand, ZYX promotes the

progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating the AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway (58). ZYX acts

as an inhibitor of the growth of colorectal cancer cells and is

associated with the levels of p53 (59). Therefore, its role in different

types of breast cancer warrants further investigation (60).

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of

the present study, as rescue experiments could not be performed due

to particular constraints, and only two cell lines were available

for experimentation. Additionally, due to a lack of in vivo

experiments to differentially validate the relationship between the

proteins, further exploration is needed to achieve this in the

future. Further limitations that should also be noted include the

need for verification of the association between FoxO3a and

proteins such as SLC38A2 and TPBG. This requires more exploration

in future studies. In addition, the proteomics analysis section of

the present study was performed by an external service provider.

The P-values reported were not corrected, and the lack of multiple

testing correction may have resulted in a higher false positive

rate.

Breast cancer development involves numerous proteins

and signaling molecules, and the results of the present study

indicate DEPs after knockdown of FoxO3a are involved in the amino

acid transport pathway and mainly serve a role in the protein

digestion and absorption signaling pathway (Fig. 10). In conclusion, knocking down

FoxO3a inhibits drug-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells and

alters expression levels of proteins in the protein digestion and

absorption signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Financial support was received for the research and/or

publication of the present article. Funding was received from the

Natural Science Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Science

and Technology (grant no. YDZJ202401085ZYTS), the Jilin Provincial

Department of Education Science and Technology Research Project

(grant no. JJKH20220460KJ), the Mekong College Student Scientific

Research and Innovation Fund Program (grant no. 2023JYMKZ001), and

the Jilin Province College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Project (grant no. S202413706001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in ProteomeXchange via the iProX partner repository under accession

number PXD068299 or at the following URL: https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD068299.

Authors' contributions

LS and ZW wrote the manuscript, and designed and

performed the experiments. YL, JL, HT and XS performed the

experiments. CH, YZ, LC and SC analyzed the data. SC was involved

in the conception and design of the study. LS and ZW confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors reviewed the results,

and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Katsura C, Ogunmwonyi I, Kankam HK and

Saha S: Breast cancer: Presentation, investigation and management.

Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 83:1–7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Avti PK, Singh J, Dahiya D and Khanduja

KL: Dual functionality of pyrimidine and flavone in targeting

genomic variants of EGFR and ER receptors to influence the

differential survival rates in breast cancer patients. Integr Biol

(Camb). 15:zyad0142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fortin J, Leblanc M, Elgbeili G, Cordova

MJ, Marin MF and Brunet A: The mental health impacts of receiving a

breast cancer diagnosis: A meta-analysis. Br J Cancer.

125:1582–1592. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ye F, Dewanjee S, Li Y, Jha NK, Chen ZS,

Kumar A, Vishakha Behl T, Jha SK and Tang H: Advancements in

clinical aspects of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in breast

cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:1052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Castellote-Huguet P, Ruiz-Espana S,

Galan-Auge C, Santabarbara JM, Maceira AM and Moratal D: Breast

cancer diagnosis using texture and shape features in MRI. Annu Int

Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2023:1–4. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nunnery SE and Mayer IA: Targeting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hormone-positive breast cancer. Drugs.

80:1685–1697. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kotsopoulos J, Gronwald J, Huzarski T,

Aeilts A, Armel SR, Karlan B, Singer CF, Eisen A, Tung N, Olopade

O, et al: Tamoxifen and the risk of breast cancer in women with a

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 201:257–264.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Masci D, Naro C, Puxeddu M, Urbani A,

Sette C, La Regina G and Silvestri R: Recent advances in drug

discovery for triple-negative breast cancer treatment. Molecules.

28:75132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu C, Feng Q, Yang H, Wang G, Huang L, Bai

Q, Zhang C, Wang Y, Chen Y, Cheng Q, et al: A light-triggered

mesenchymal stem cell delivery system for photoacoustic imaging and

chemo-photothermal therapy of triple negative breast cancer. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 5:18003822018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hwang KT, Kim J, Jung J, Chang JH, Chai

YJ, Oh SW, Oh S, Kim YA, Park SB and Hwang KR: Impact of breast

cancer subtypes on prognosis of women with operable invasive breast

cancer: A population-based study using SEER database. Clin Cancer

Res. 25:1970–1979. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Al-Azhri J, Zhang Y, Bshara W, Zirpoli G,

McCann SE, Khoury T, Morrison CD, Edge SB, Ambrosone CB and Yao S:

Tumor expression of vitamin D receptor and breast cancer

histopathological characteristics and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res.

23:97–103. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sun Z, Zhou D, Yang J and Zhang D:

Doxorubicin promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion via

DCAF13. FEBS Open Bio. 12:221–230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang D, Qiu T, Peng J, Li S, Tala Ren W,

Yang C, Wen Y, Chen CH, Sun J, et al: YB-1 is a positive regulator

of KLF5 transcription factor in basal-like breast cancer. Cell

Death Differ. 29:1283–1295. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Katzenellenbogen BS, Guillen VS and

Katzenellenbogen JA: Targeting the oncogenic transcription factor

FOXM1 to improve outcomes in all subtypes of breast cancer. Breast

Cancer Res. 25:762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Francois M, Donovan P and Fontaine F:

Modulating transcription factor activity: Interfering with

protein-protein interaction networks. Semin Cell Dev Biol.

99:12–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Liu TT, Yang H, Zhuo FF, Yang Z, Zhao MM,

Guo Q, Liu Y, Liu D, Zeng KW and Tu PF: Atypical E3 ligase ZFP91

promotes small-molecule-induced E2F2 transcription factor

degradation for cancer therapy. EBioMedicine. 86:1043532022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pang X, Zhou Z, Yu Z, Han L, Lin Z, Ao X,

Liu C, He Y, Ponnusamy M, Li P and Wang J: Foxo3a-dependent miR-633

regulates chemotherapeutic sensitivity in gastric cancer by

targeting Fas-associated death domain. RNA Biol. 16:233–248. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Meng XY, Wang KJ, Ye SZ, Chen JF, Chen ZY,

Zhang ZY, Yin WQ, Jia XL, Li Y, Yu R and Ma Q: Sinularin stabilizes

FOXO3 protein to trigger prostate cancer cell intrinsic apoptosis.

Biochem Pharmacol. 220:1160112024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Khoshinani HM, Afshar S, Pashaki AS,

Mahdavinezhad A, Nikzad S, Najafi R, Amini R, Gholami MH,

Khoshghadam A and Saidijam M: Involvement of miR-155/FOXO3a and

miR-222/PTEN in acquired radioresistance of colorectal cancer cell

line. Jpn J Radiol. 35:664–672. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wolfe AR, Debeb BG, Lacerda L, Larson R,

Bambhroliya A, Huang X, Bertucci F, Finetti P, Birnbaum D, Van

Laere S, et al: Simvastatin prevents triple-negative breast cancer

metastasis in pre-clinical models through regulation of FOXO3a.

Breast Cancer Res Treat. 154:495–508. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen S, Li YQ, Yin XZ, Li SZ, Zhu YL, Fan

YY, Li WJ, Cui YL, Zhao J, Li X, et al: Recombinant adenoviruses

expressing apoptin suppress the growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells

and affect cell autophagy. Oncol Rep. 41:2818–2832. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kang BG, Shende M, Inci G, Park SH, Jung

JS, Kim SB, Kim JH, Mo YW, Seo JH, Feng JH, et al: Combination of

metformin/efavirenz/fluoxetine exhibits profound anticancer

activity via a cancer cell-specific ROS amplification. Cancer Biol

Ther. 24:20–32. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ: Analyzing

real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc.

3:1101–1108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Khan MA, Sadaf Ahmad I, Aloliqi AA, Eisa

AA, Najm MZ, Habib M, Mustafa S, Massey S, Malik Z, et al: FOXO3

gene hypermethylation and its marked downregulation in breast

cancer cases: A study on female patients. Front Oncol.

12:10780512022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Yang L, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Li Y, Xie

Z, Wang H, Lin Y, Lin Q, Gong T, et al: Live macrophage-delivered

doxorubicin-loaded liposomes effectively treat triple-negative

breast cancer. ACS Nano. 16:9799–9809. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ansari L, Shiehzadeh F, Taherzadeh Z,

Nikoofal-Sahlabadi S, Momtazi-Borojeni AA, Sahebkar A and Eslami S:

The most prevalent side effects of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

monotherapy in women with metastatic breast cancer: A systematic

review of clinical trials. Cancer Gene Ther. 24:189–193. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wei Y, Guo Y, Zhou J, Dai K, Xu Q and Jin

X: Nicotinamide overcomes doxorubicin resistance of breast cancer

cells through deregulating SIRT1/Akt pathway. Anticancer Agents Med

Chem. 19:687–696. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sun L, Liu J, Bao D, Hu C, Zhao Y and Chen

S: Progress in the study of FOXO3a interacting with microRNA to

regulate tumourigenesis development. Front Oncol. 13:12939682023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen YF, Pandey S, Day CH, Chen YF, Jiang

AZ, Ho TJ, Chen RJ, Padma VV, Kuo WW and Huang CY: Synergistic

effect of HIF-1α and FoxO3a trigger cardiomyocyte apoptosis under

hyperglycemic ischemia condition. J Cell Physiol. 233:3660–3671.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yadav RK, Chauhan AS, Zhuang L and Gan B:

FoxO transcription factors in cancer metabolism. Semin Cancer Biol.

50:65–76. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Liu H, Yin J, Wang H, Jiang G, Deng M,

Zhang G, Bu X, Cai S, Du J and He Z: FOXO3a modulates WNT/β-catenin

signaling and suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in

prostate cancer cells. Cell Signal. 27:510–518. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Li H, Tang X, Sun Z, Qu Z and Zou X:

Integrating bioinformatics and experimental models to investigate

the mechanism of the chelidonine-induced mitotic catastrophe via

the AKT/FOXO3/FOXM1 axis in breast cancer cells. Biomol Biomed.

24:560–574. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gauthier-Coles G, Bröer A, McLeod MD,

George AJ, Hannan RD and Bröer S: Identification and

characterization of a novel SNAT2 (SLC38A2) inhibitor reveals

synergy with glucose transport inhibition in cancer cells. Front

Pharmacol. 13:9630662022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Petry ÉR, Dresch DF, Carvalho C, Medeiros

PC, Rosa TG, de Oliveira CM, Martins LAM, Guma FCR, Marroni NP and

Wannmacher CMD: Oral glutamine supplementation relieves muscle loss

in immobilized rats, altering p38MAPK and FOXO3a signaling

pathways. Nutrition. 118:1122732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yuan Q, Wang Q, Li J, Yin L, Liu S, Zu X

and Shen Y: CCT196969 inhibits TNBC by targeting the

HDAC5/RXRA/ASNS axis to down-regulate asparagine synthesis. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 44:2312025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhao X, Lai H, Li G, Qin Y, Chen R, Labrie

M, Stommel JM, Mills GB, Ma D, Gao Q and Fang Y: Rictor

orchestrates β-catenin/FOXO balance by maintaining redox

homeostasis during development of ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

44:1820–1832. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Park S, Yoo JE, Yeon GB, Kim JH, Lee JS,

Choi SK, Hwang YG, Park CW, Cho MS, Kim J, et al: Trophoblast

glycoprotein is a new candidate gene for Parkinson's disease. NPJ

Parkinsons Dis. 7:1102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

He P, Jiang S, Ma M, Wang Y, Li R, Fang F,

Tian G and Zhang Z: Trophoblast glycoprotein promotes pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma cell metastasis through Wnt/planar cell

polarity signaling. Mol Med Rep. 12:503–509. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Su H, Yu S, Sun F, Lin D, Liu P and Zhao

L: LINC00342 induces metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma by targeting

miR-15b/TPBG. Acta Biochim Pol. 69:291–297. 2022.

|

|

40

|

Ye F, Liang Y, Wang Y, Yang RL, Luo D, Li

Y, Jin Y, Han D, Chen B, Zhao W, et al: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts facilitate breast cancer progression through exosomal

circTBPL1-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Death Dis.

14:4712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hu G, Leal M, Lin Q, Affolter T, Sapra P,

Bates B and Damelin M: Phenotype of TPBG gene replacement in the

mouse and impact on the pharmacokinetics of an antibody-drug

conjugate. Mol Pharm. 12:1730–1737. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Stern PL, Brazzatti J, Sawan S and McGinn

OJ: Understanding and exploiting 5T4 oncofoetal glycoprotein

expression. Semin Cancer Biol. 29:13–20. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kandasamy P, Zlobec I, Nydegger DT,

Pujol-Giménez J, Bhardwaj R, Shirasawa S, Tsunoda T and Hediger MA:

Oncogenic KRAS mutations enhance amino acid uptake by colorectal

cancer cells via the hippo signaling effector YAP1. Mol Oncol.

15:2782–2800. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kandasamy P, Gyimesi G, Kanai Y and

Hediger MA: Amino acid transporters revisited: New views in health

and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 43:752–789. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Morotti M, Zois CE, El-Ansari R, Craze ML,

Rakha EA, Fan SJ, Valli A, Haider S, Goberdhan DCI, Green AR and

Harris AL: Increased expression of glutamine transporter

SNAT2/SLC38A2 promotes glutamine dependence and oxidative stress

resistance, and is associated with worse prognosis in

triple-negative breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 124:494–505. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Morotti M, Bridges E, Valli A, Choudhry H,

Sheldon H, Wigfield S, Gray N, Zois CE, Grimm F, Jones D, et al:

Hypoxia-induced switch in SNAT2/SLC38A2 regulation generates

endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

116:12452–12461. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Stretton C, Lipina C, Hyde R, Cwiklinski

E, Hoffmann TM, Taylor PM and Hundal HS: CDK7 is a component of the

integrated stress response regulating SNAT2 (SLC38A2)/System A

adaptation in response to cellular amino acid deprivation. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1866:978–991. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Shen Y, Li M, Xiong Y, Gui S, Bai J, Zhang

Y and Li C: Proteomics analysis identified ASNS as a novel

biomarker for predicting recurrence of skull base chordoma. Front

Oncol. 11:6984972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Du F, Chen J, Liu H, Cai Y, Cao T, Han W,

Yi X, Qian M, Tian D, Nie Y, et al: SOX12 promotes colorectal

cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by regulating asparagine

synthesis. Cell Death Dis. 10:2392019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Knott SRV, Wagenblast E, Khan S, Kim SY,

Soto M, Wagner M, Turgeon MO, Fish L, Erard N, Gable AL, et al:

Asparagine bioavailability governs metastasis in a model of breast

cancer. Nature. 554:378–381. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yang H, He X, Zheng Y, Feng W, Xia X, Yu X

and Lin Z: Down-regulation of asparagine synthetase induces cell

cycle arrest and inhibits cell proliferation of breast cancer. Chem

Biol Drug Des. 84:578–584. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qin C, Yang X and Zhan Z: High expression

of asparagine synthetase is associated with poor prognosis of

breast cancer in Chinese population. Cancer Biother Radiopharm.

35:581–585. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Nishikawa G, Kawada K, Hanada K, Maekawa

H, Itatani Y, Miyoshi H, Taketo MM and Obama K: Targeting

asparagine synthetase in tumorgenicity using patient-derived

tumor-initiating cells. Cells. 11:32732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen W, Qin Y, Qiao L, Liu X, Gao C, Li

TR, Luo Y, Li D, Yan H, Han L, et al: FAM50A drives breast cancer

brain metastasis through interaction with C9ORF78 to enhance

L-asparagine production. Sci Adv. 11:eadt30752025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Reis LMD, Adamoski D, Souza RO, Ascenção

CF, de Oliveira KR, Corrêa-da-Silva F, de Sá, Patroni FM, Dias MM,

Consonni SR, de Moraes-Vieira PMM, et al: Dual inhibition of

glutaminase and carnitine palmitoyltransferase decreases growth and

migration of glutaminase inhibition-resistant triple-negative

breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 294:9342–9357. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Partynska A, Gomulkiewicz A, Dziegiel P

and Podhorska-Okolow M: The role of zyxin in carcinogenesis.

Anticancer Res. 40:5981–5988. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kotb A, Hyndman ME and Patel TR: The role

of zyxin in regulation of malignancies. Heliyon. 4:e006952018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Cai T, Bai J, Tan P, Huang Z, Liu C, Wu Z,

Cheng Y, Li T, Chen Y, Ruan J, et al: Zyxin promotes hepatocellular

carcinoma progression via the activation of AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway. Oncol Res. 31:805–817. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Mohammadi H, Shakiba E, Rostampour R,

Bahremand K, Goodarzi MT, Bashiri H, Ghobadi KN and Asadi S: Down

expression of zyxin is associated with down expression of p53 in

colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Cell Med. 14:461–471. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ma B, Cheng H, Gao R, Mu C, Chen L, Wu S,

Chen Q and Zhu Y: Zyxin-Siah2-Lats2 axis mediates cooperation

between Hippo and TGF-β signalling pathways. Nat Commun.

7:111232016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|