Introduction

Primary liver cancer (PLC) is the sixth most common

malignant tumor worldwide (1), and

primarily includes hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma. In China, PLC had the second highest mortality

rate among all cancers in 2020 (2).

HCC is the most prevalent type of PLC, accounting for ~90% of PLC

cases (3). The most common causes

of HCC include viral hepatitis, metabolic disorders, alcohol

consumption and smoking (4).

Surgical resection is the standard treatment for

patients with early stage PLC. Recurrence occurs in ~50% of

patients who undergo surgical resection within 2 years and the

5-year survival rate ranges between 50 and 75% (5). Patients with HCC frequently lack

noticeable clinical symptoms, resulting in delayed medical

attention, and missed opportunities for surgical resection or liver

transplantation. Systematic therapies, including immunotherapy,

targeted therapy, local radiotherapy and chemotherapy, are often

used in patients with intermediate-to advanced-stage disease

(6,7). However, drug resistance is the primary

cause of treatment failure and can lead to tumor recurrence or

metastasis (8). Once recurrence and

metastasis occur, the prognosis of patients with HCC decreases.

Therefore, high recurrence and metastasis rates due to therapeutic

resistance remain major clinical issues.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a rare subpopulation of

tumor cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation. CSCs are

resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and are associated with

tumorigenesis, recurrence and metastasis (9–11).

CSCs exhibit characteristics that are distinct from those of other

cancer cells and several surface markers have been identified in

previous studies, including CD44, CD133, epithelial cell adhesion

molecule (EpCAM) and hepatic leukemia factor (12–15).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are short endogenous

non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by binding to target

mRNAs (16). Previous studies have

reported that miRNAs serve key roles in tumor cell proliferation,

migration and invasion (17,18).

However, potential miRNAs associated with HCC-CSCs and their roles

in tumor therapy resistance, recurrence and metastasis remain to be

elucidated.

The present study aimed to identify potential miRNAs

associated with HCC-CSCs through a systematic review, data mining

and bioinformatics analysis. Subsequently, the expression of

candidate miRNAs and their biological functions were explored in

HCC-CSCs.

Materials and methods

Systematic review

The present study was reported as per the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses protocol

(19) and registered in the

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

(CRD42024508526).

Search strategy

All of the research articles used in the present

study were gathered from two publicly available literature

databases, PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/wos/),

with a search range from the date of establishment of the database

to January 15, 2024. A search strategy was collaboratively

developed and independently executed by two authors based on the

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study type

(PICOS) (20). The formulated PICOS

framework was as follows: i) The population was composed of

patients with HCC; ii) the intervention was the altered expression

levels of miRNAs in patients; iii) the comparison was between

groups, one with high miRNA expression and the other with low miRNA

expression; iv) the outcome was the difference in survival

prognosis between patients with HCC with low and high miRNA

expression; and v) the study method was comparative research. The

key words and search details are shown in Table SI.

Eligibility criteria

Research articles were included based on the

following criteria: i) Demonstrated significantly different miRNA

expression levels in patients with HCC (P<0.05); ii) compared

the prognoses of high and low miRNA expression groups; and iii)

described a clear follow-up time for patients. Studies were

excluded based on the following criteria: i) Did not use human

subjects; ii) did not perform a comparative analysis; iii) did not

include HCC; iv) did not have available data that could be

extracted; or v) were not original research projects.

Study selection and data

extraction

After excluding review articles and eliminating

duplicate items, the literature search results were imported into

Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/), an online tool

for systematic literature reviews. Independent screening of titles

and abstracts was conducted using inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The miRNAs mentioned in the target articles were extracted and

arranged in tables that included the first author, year, country,

number of patients, follow-up period, type of evidence, miRNA and

expression.

Data mining analysis

Coremine Medical (http://www.coremine.com/medical/), an online

data-mining tool, was used to explore potential miRNAs associated

with CSCs, metastasis, recurrence and drug resistance in HCC. Key

words including ‘liver carcinoma’, ‘neoplasm recurrence’, ‘neoplasm

metastasis’, ‘drug resistance’ and ‘neoplastic stem cells’ were

chosen as the search strategy, and the associated genes were

downloaded and screened for miRNAs with a significant difference

(P<0.05), based on the analysis role of the web tool.

Bioinformatics analysis

The ONCO.IO website (https://onco.io/)

was used to explore miRNA-target gene interactions and their

biological processes in HCC. A regulatory network diagram was

created to illustrate these interactions. The Enrichr database

(https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) was

used for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analysis. Box plots on the Encyclopedia of RNA

Interactomes (ENCORI) website (https://rnasysu.com/encori/) indicated the

differential expression levels of miRNAs between cancerous and

paracancerous tissue samples in liver HCC (LIHC). Kaplan-Meier

survival curves (https://www.kmplot.com) were used to assess the

effects of different miRNA expression levels on the survival of

patients with LIHC.

Cell culture and CSC culture

The Huh7 cell line was purchased from The Cell Bank

of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences and

confirmed by short tandem repeat profiling without discrepancies.

The cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. 11965118; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS [cat. no.

E01010; Eva (Suzhou) Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.] and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. C100C5; Suzhou Xinsaimei

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Cell culture was performed at 37°C in a

5% CO2 incubator. HCC-CSCs were developed from Huh7

cells using the protocol as described previously (21). The Huh7 cell line was cultured under

ultra-low attachment conditions with DMEM supplemented with 1%

penicillin-streptomycin, 0.5% N2 supplement (cat. no. 17502-048;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast

growth factor (bFGF; cat. no. HY-P7004; MedChemExpress) and 20

ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; cat. no. HY-P7109;

MedChemExpress) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 5–7

days.

Tumor sphere assays and sphere

formation efficiency (SFE)

A total of 2,000 cells in the logarithmic growth

phase were selected, seeded into 24-well ultra-low adsorption

culture plates and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1%

penicillin-streptomycin, 0.5% N2 supplement, 20 ng/ml bFGF, and 20

ng/ml EGF at 37°C in a 5% CO2 cell culture incubator for

6 days. Spherical cells were defined as those with diameters ≥100

µm. Imaging was performed using a Motic AE31E inverted microscope

(Motic Industrial Group Co., Ltd.). SFE was calculated on day 6

using the following formula: SFE=(number of spheres counted/number

of seeded cells) ×100.

miRNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

miRNAs were extracted and purified from Huh7 and

Huh7-CSCs using the miRcute miRNA Isolation Kit (cat. no. DP501;

Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The concentration and purity of the miRNAs were measured

using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The RT-qPCR detection of miRNA was performed

using the poly(A) tailing-based method. RT was performed using the

miRNA 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Tailing A; cat. no. MR201-01;

Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The reverse transcription for miRNA was

carried out at 37°C for 60 min, followed by an enzyme inactivation

step at 85°C for 5 sec. qPCR was performed using a Tap Pro

Universal SYBR™ qPCR Master Mix kit (cat. no. Q712-02;

Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The qPCR protocol consisted of an

initial denaturation step (95°C for 30 sec), followed by 40

amplification cycles (denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec), and concluded with a melt

curve analysis step (95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec and 95°C for

15 sec). U6 was used as the endogenous control and the

2−ΔΔCq method was used to analyze expression levels

(22). The primer sequences of the

detected genes were as follows: Hsa-miR-17-5p-q forward (F),

5′-GCCGCAAAGTGCTTACAGTGC-3′ and the reverse (R) primer for

miR-17-5p was the Universal reverse Q primer from the miRNA 1st

Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit; U6 F, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ and R,

5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the

Coremine, ONCO.IO, Enrichr, ENCORI and Kaplan-Meier plotter

databases. The ENCORI pan-cancer dataset (version 2024), comprising

10,546 samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), was analyzed.

The best-performing percentile was automatically selected as the

cutoff. The miRNA expression levels were quantified as reads per

million (RPM) and transformed using log2 (RPM + 0.01) to

normalize the data distribution. The RT-qPCR data are presented as

the mean ± Standard Error of the Mean and each experiment was

performed in triplicate unless otherwise noted. Differences in the

RT-qPCR results between the two groups were analyzed using unpaired

Student's t-test. Unless specified otherwise, P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Study characteristics

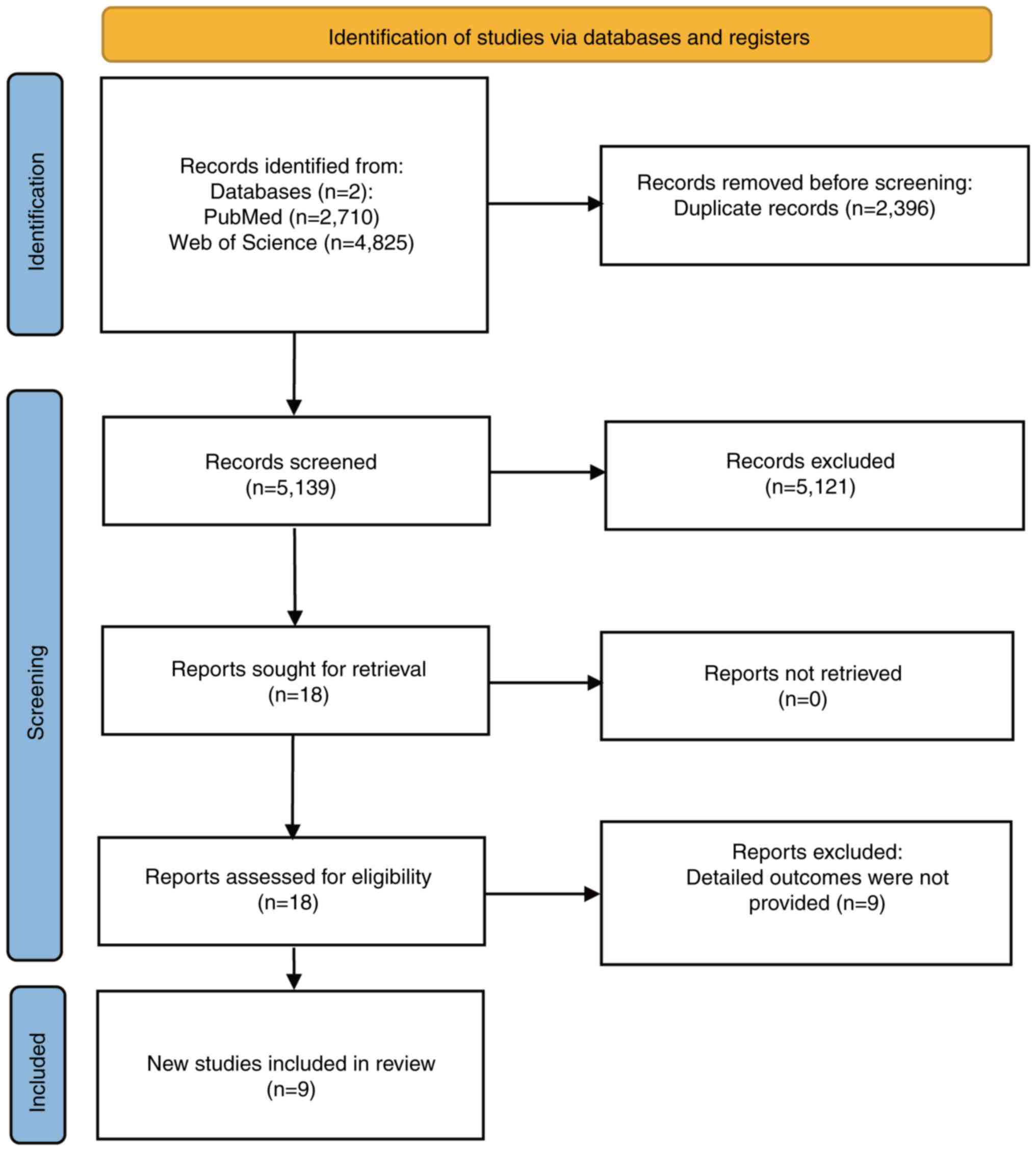

The initial literature search retrieved 7,535

research articles, with 2,710 from PubMed and 4,825 from Web of

Science. After further screening, 2,396 duplicates were removed,

and the titles and abstracts of the remaining 5,139 articles were

reviewed. A total of 5,121 articles failed to meet the inclusion

criteria, resulting in 18 articles selected for full reading and

review. Nine additional articles were excluded because they did not

meet the inclusion criteria and the remaining nine were included in

the study (23–31). The screening process is illustrated

in Fig. 1. These studies focused on

nine different miRNAs collected from the serum and tissues of

patients with HCC in China and South Korea. All nine miRNAs were

reported to have notable prognostic capability for patients with

HCC. The details of the nine studies are shown in Table I encompassing 1,318 patients with

HCC collectively.

| Table I.Extracted data of the nine articles

selected for the systematic review. |

Table I.

Extracted data of the nine articles

selected for the systematic review.

| First author,

year | Country | No. of patients

(male, female, unknown) | Follow-up

period | Type of evidence

(95% CI) | miRNA | Expression | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Xie et al,

2018 | China | 149 (117, 30,

2) | 150 months | OS: HR, 0.072

(0.033–0.159); | miR-33a | Downregulated | (23) |

|

|

|

|

| P<0.001 PFS: HR,

0.194 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| (0.118–0.317);

P<0.001 |

|

|

|

| Zhuang et

al, 2015 | China | 182 (155, 27) | 656±393 days | OS: HR, 2.793

(1.550–5.033); | miR-128-2 | Upregulated | (24) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.001 |

| (HCC serum) |

|

| Sun et al,

2015 | China | 60 (40, 20) | >24 months | DFS: HR, 2.681

(1.306–5.504); | miR-9 | Upregulated | (25) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.007 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

| Chen et al,

2012 | China | 66 (56, 10) | 100 months | OS: HR, 0.332

(0.139–0.793); | miR-203 | Downregulated | (26) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.013 RFS: HR,

0.202 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| (0.064–0.638);

P=0.006 |

|

|

|

| Zhou et al,

2016 | China | 38 (30, 8) | 25 months | DFS: RR, 3.273

(1.107–9.679); | miR-375 | Downregulated | (27) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.032 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

| Luo et al,

2019 | China | 148 (100, 48) | 24 months | OS: HR, 2.226

(1.235–4.012); | miR-200c | Downregulated | (28) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.008 RFS:

2.662 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| (1.618–4.38);

P<0.001 |

|

|

|

| Ha et al,

2019 | South | 289 (238, 51) | 151.4 months | IHRFS: HR, 1.89

(1.16–3.07); | miR-122 | Downregulated | (29) |

|

| Korea |

|

| P=0.010 DMFS: HR,

2.14 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| (1.05–4.36);

P=0.036 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RFS: HR, 2.17

(1.34–3.52); |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| P=0.002 |

|

|

|

| Zhu et al,

2012 | China | 266 (225, 41) | 81 months | OS: HR, 1.0

(0.7–1.4); P=0.901 | miR-29a-5p | Upregulated | (30) |

|

|

|

|

| TTR: HR, 0.5

(0.3–0.8); |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| P=0.003 |

|

|

|

| Chen et al,

2012 | China | 120 (102, 18) | 46 months | OS: RR, 4.96

(1.78–13.82); | miR-17-5p | Upregulated | (31) |

|

|

|

|

| P=0.002 DFS: RR,

1.79 |

| (HCC tissues) |

|

|

|

|

|

| (1.14–2.98);

P=0.042 |

|

|

|

miR-17-5p: Potential miRNA associated

with CSCs, drug resistance, recurrence and metastasis in HCC

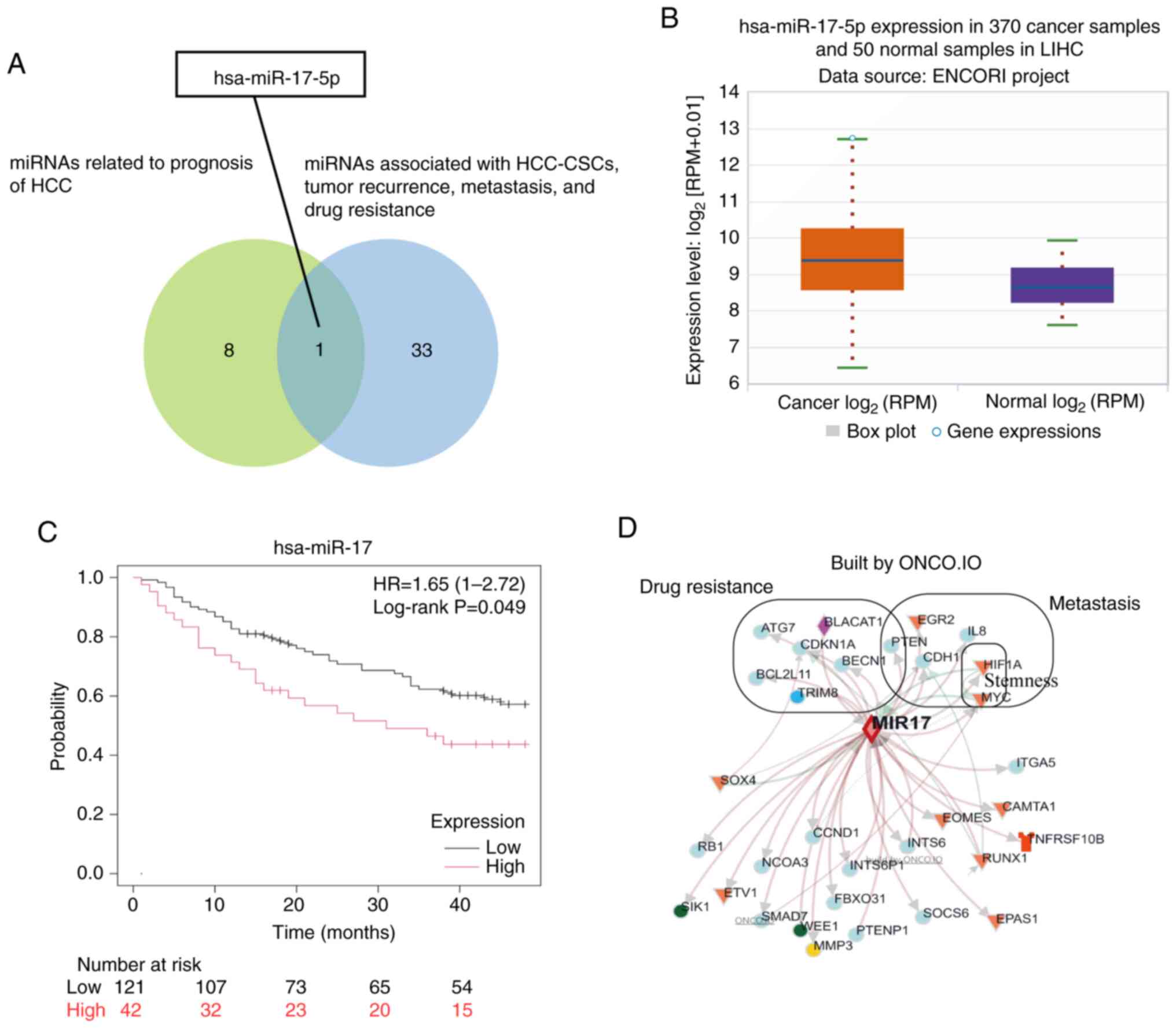

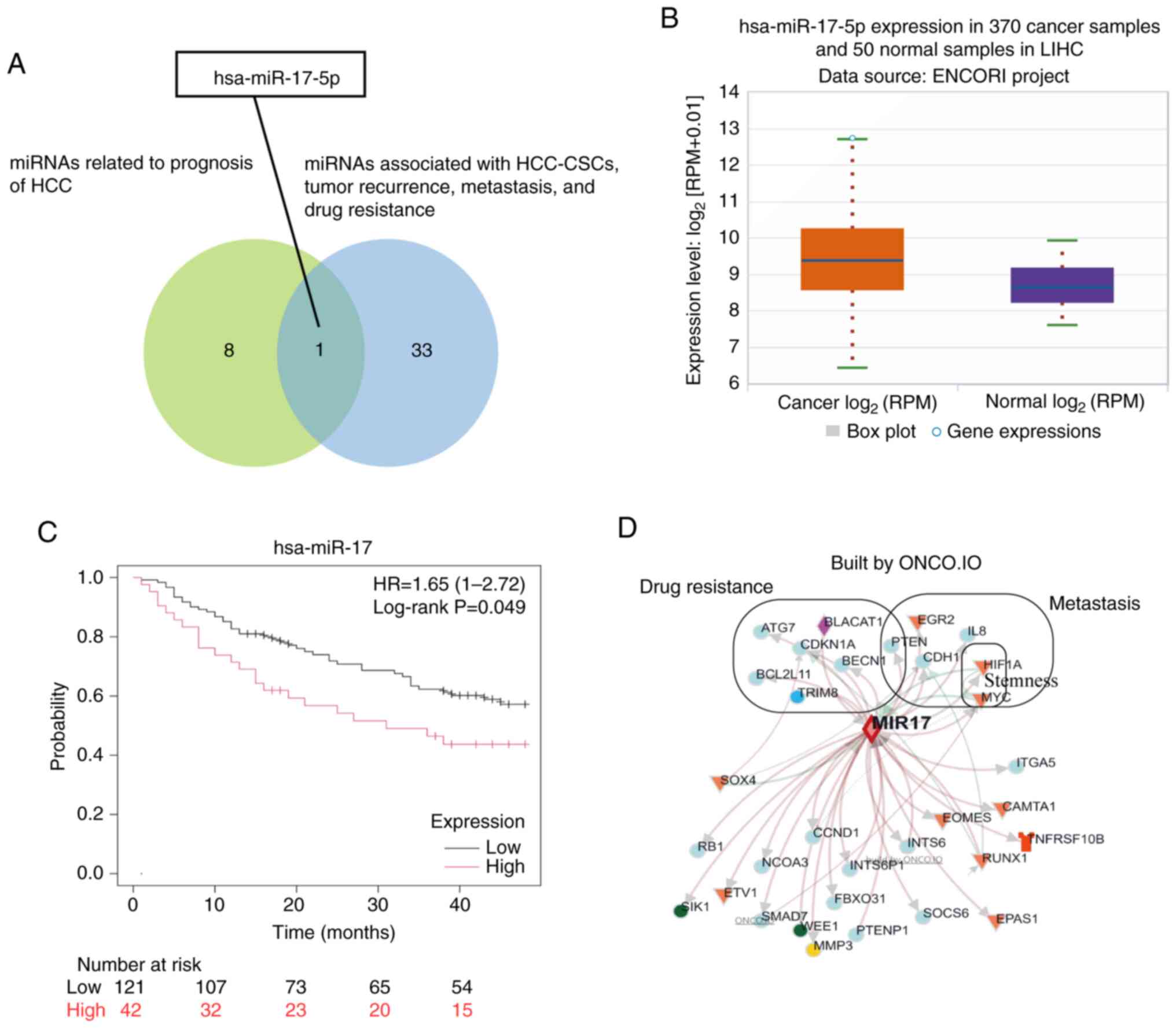

A total of 34 miRNAs, including miR-7-3HG, miR-100,

miR-25, miR-26B, miR-200A, miR-184, miR-190A, miR-21,miR-186,

miR-19A, miR-17, miR-196B, miR-22, Let-7d, miR-145, miR-183,

miR-34A,miR-17HG, miR-185, miR-107, Let-7c, miR-203A, miR-137,

miR-96, miR-191, miR-98, miR-4435-2HG, Let-7b, miR-31, miR-93,

miR-146A, miR-15B, miR-221, miR-192, associated with HCC, neoplasm

recurrence, neoplasm metastasis, drug resistance and CSCs were

identified in the Coremine database. The intersecting miRNA,

miR-17-5p, was selected by comparing the nine miRNAs from the

included studies with the 34 miRNAs identified in the Coremine

database (Fig. 2A). The ENCORI tool

demonstrated that miR-17-5p was expressed at significantly higher

levels in 370 cancerous tissues compared with that in 50 para-tumor

tissues (fold change, 2.08; Fig.

2B). Survival analysis of miR-17-5p, which included 163

patients who were followed-up for 48 months, was performed using

the Kaplan-Meier plotter online tool. The results of this analysis

revealed a significant association between miR-17-5p expression and

overall survival (months) in patients with HCC (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 2.miR-17-5p is a miRNA potentially

associated with CSCs, metastasis, recurrence and drug resistance in

HCC. (A) Venn diagram illustrating how the potential miRNA

(miR-17-5p) was selected by exploring the intersection between the

nine miRNAs associated with the prognosis of HCC, and the 34 miRNAs

associated with HCC-CSCs, metastasis, tumor recurrence and drug

resistance. (B) Box plot of miR-17-5p expression in LIHC. (C)

Survival analysis of miR-17-5p in LIHC. (D) Interaction network of

targeted genes of miR-17-5p, with the 12 genes involved in

metastasis, stemness and drug resistance specially marked.

miR/miRNA, microRNA; CSC, cancer stem cell; HCC, hepatocellular

carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; RPM, reads per

million. |

The interaction network of the target genes

regulated by miR-17-5p is shown in Fig.

2D. These 12 genes were directly identified through functional

analysis (pathogenic processes) using the ONCO.IO platform,

including two stemness-associated genes, seven drug

resistance-associated genes and six metastasis-associated genes.

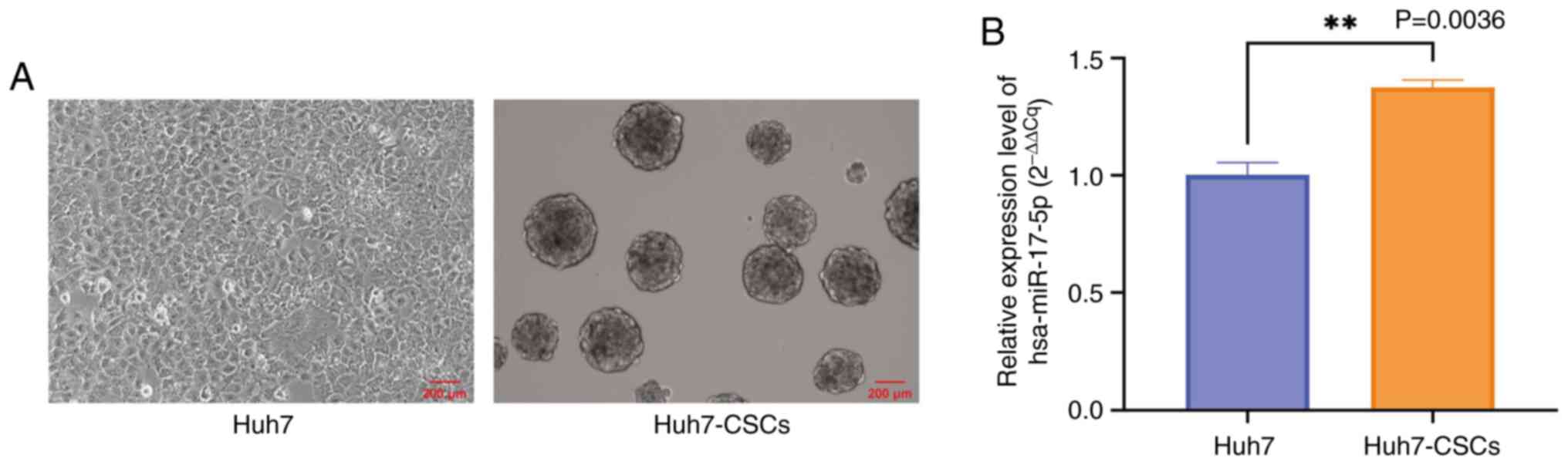

The combined list yielded 12 unique genes. Huh7-CSCs were

successfully developed from Huh7 cells. Spherical cells with a

diameter ≥100 µm were observed after 6 days of culturing in

ultra-low attachment conditions and the SFE of Huh7-CSCs was

calculated to be 4.7% (Fig. 3A).

Subsequently, the expression levels of miR-17-5p in Huh7-CSCs were

revealed to be significantly higher compared with those in Huh7

cells (Fig. 3B). The primary

biological processes regulated by miR-17-5p and its target genes,

including proliferation, invasion, migration, metastasis, stemness

and drug resistance, were explored using the ONCO.IO database

(Table II).

| Table II.Role of microRNA-17-5p targeted genes

in biological processes of cancer. |

Table II.

Role of microRNA-17-5p targeted genes

in biological processes of cancer.

| Process | No. of genes | Targeted genes |

|---|

| Proliferation | 17 | RBL2, RB1, NCOA3,

SOCS6, UBE2C, ETV1, SIK1, CDKN1A, RND3, Myc, SMAD7, STAT3, Sox4,

CCND1, RELA, BLACAT1 and CDH1 |

| Invasion | 14 | PTEN, EGR2, ITGA5,

ITGB1, ETV1, IL8, PTENP1, CD274, Myc, Sox4, STAT3, HIF1A, BLACAT1

and RELA |

| Migration | 10 | RB1, PTEN, ETV1,

SIK1, PTENP1, Myc, INTS6, INTS6P1, Sox4 and RUNX1 |

| Metastasis | 6 | PTEN, EGR2, IL8,

HIF1A, Myc and CDH1 |

| Stemness | 2 | HIF1A and Myc |

| Drug

resistance | 7 | BLACAT1, ATG7,

CDKN1A, PTEN, BCL2L11, BECN1 and TRIM8 |

The Enrichr tool was used to explore the potential

pathways of the 12 miR-17-5p target genes involved in metastasis,

stemness and drug resistance. These 20 pathways are listed in

Table III after excluding those

associated with other diseases, including acute myeloid leukemia

and thyroid cancer. These 20 pathways are primarily involved in the

regulation of metabolism, cell fate, hepatitis viruses and the

immune checkpoint system. Certain pathways, including central

carbon metabolism and proteoglycans are closely associated with

cell stemness.

| Table III.The 20 pathways of

microRNA-17-5p-targeted genes associated with metastasis, stemness

and drug resistance in HCC. |

Table III.

The 20 pathways of

microRNA-17-5p-targeted genes associated with metastasis, stemness

and drug resistance in HCC.

| Term | P-value | Genes |

|---|

| Pathways in

cancer |

2.75×10−7 | CDKN1A, BCL2L11,

CDH1, Myc, PTEN and HIF1A |

| Autophagy |

9.99×10−7 | BECN1, PTEN, HIF1A

and ATG7 |

| Central carbon

metabolism in cancer |

8.83×10−6 | Myc, PTEN and

HIF1A |

| miRNAs in

cancer |

2.54×10−5 | CDKN1A, BCL2L11,

Myc and PTEN |

| PI3K-AKT signaling

pathway |

4.27×10−5 | CDKN1A, BCL2L11,

Myc and PTEN |

| FOXO signaling

pathway |

5.79×10−5 | CDKN1A, BCL2L11 and

PTEN |

| Cellular

senescence |

9.73×10−5 | CDKN1A, Myc and

PTEN |

| Hepatitis B |

1.09×10−4 | EGR2, CDKN1A and

Myc |

| Hepatocellular

carcinoma |

1.21×10−4 | CDKN1A, Myc and

PTEN |

| Proteoglycans in

cancer |

2.18×10−4 | CDKN1A, Myc and

HIF1A |

| Mitophagy |

7.35×10−4 | BECN1 and

HIF1A |

| p53 signaling

pathway |

8.47×10−4 | CDKN1A and

PTEN |

| ErbB signaling

pathway |

1.15×10−3 | CDKN1A and Myc |

| PD-L1 expression

and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer |

1.26×10−3 | PTEN and HIF1A |

| HIF-1 signaling

pathway |

1.87×10−3 | CDKN1A and

HIF1A |

| Cell cycle |

2.42×10−3 | CDKN1A and Myc |

| Apelin signaling

pathway |

2.94×10−3 | BECN1 and CDH1 |

| Apoptosis |

3.15×10−3 | BECN1 and

BCL2L11 |

| Hepatitis C |

3.84×10−3 | CDKN1A and Myc |

| JAK-STAT signaling

pathway |

4.08×10−3 | CDKN1A and Myc |

Discussion

Previous studies have identified ~2,000 miRNAs in

humans that regulate >60% of protein-coding genes and perform

post-transcriptional gene regulation by binding to target genes

(32,33). Systematic reviews have been used as

a high-evidence tool to detect potential miRNAs with diagnostic

and/or prognostic potential in the study and treatment of cancer.

For example, a meta-analysis of nine studies (involving 1,624 study

participants, of which 957 were patients with cervical cancer and

667 were healthy controls) revealed a marked upregulation of miR-21

expression in cervical cancer (34). In the present study, nine miRNAs

were found to be associated with the prognosis of patients with HCC

in a systematic review. In HCC tumor tissues, the expression levels

of miR-33a, miR-203, miR-375 and miR-200c were markedly

downregulated, whereas those of miR-9, miR-29a-5p and miR-17-5p

were markedly upregulated. Due to the post-transcriptional

regulation feature of miRNA, several miRNAs are abnormally

expressed during the development of HCC and can affect patient

prognosis. These miRNAs bind to multiple target genes and are

involved in numerous biological processes in HCC. For example,

miR-375, which is downregulated in HCC tissues, inhibits tumor

angiogenesis by targeting platelet-derived growth factor C.

Additionally, miR-375 has been shown to reduce sorafenib resistance

by regulating astrocyte elevated gene-1and sirtuin (SIRT)5

(35,36). By contrast, miR-9 is not only

upregulated in HCC tissues but also exhibits higher expression in

patients with HCC with early vascular invasion. Mechanistically,

miR-9 promotes HCC cell invasion and migration by targeting SIRT1,

FOXO1 and SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent

regulator of chromatin, subfamily D, member 2 (37). Data mining was combined with a

systematic review to further understand the potential impact of

these miRNAs on stemness, tumor metastasis, recurrence and drug

resistance in HCC. miR-17-5p was specifically identified as a

potential miRNA associated with these processes. A previous study

reported that miR-17-5p expression is strongly associated with the

number of tumor nodules, pathological grading of HCC and venous

infiltration (31). Other studies

have demonstrated that miR-17-5p induces hepatocarcinogenesis, and

promotes the proliferation and migration of HCC cells by targeting

Smad3, Runt-related transcription factor 3 and PTEN (38–40).

However, the role of miR-17-5p in HCC-CSCs remains to be

elucidated.

CSCs are gradually gaining popularity in research

because of their ability to drive tumor metastasis and recurrence

(41–43). However, the mechanisms underlying

stemness maintenance remain unclear. CSCs are a subpopulation of

cancer cells that remain dormant and may contribute to drug

resistance and the risk of recurrence (44,45).

By contrast, most HCC cells exhibit rapid proliferation and are

easily eliminated by DNA damage therapy. A previous study reported

that miR-17-5p expression is often higher in cancerous tissues

compared with that in paracancerous tissues (46). Notably, the expression levels of

miR-17-5p were significantly higher in HCC-CSCs compared with those

in HCC cells in the present study. This finding suggests that

miR-17-5p expression in HCC-CSCs may differ from that in the

majority of HCC cells and the high expression level of miR-17-5p

could be a unique biological feature that maintains the stemness of

HCC-CSCs.

To reveal the role of miR-17-5p in regulating

stemness, the target genes of miR-17-5p and their biological

processes were predicted using bioinformatics. Notably, miR-17-5p

may be involved in regulating stemness by targeting

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF1A) and Myc. Hypoxia is an

essential feature of the tumor microenvironment in the majority of

solid tumors, which contributes to tumor metabolism reprogramming

and leads to the failure of antitumor therapy (47). According to a previous study,

knocking down HIF-1α expression can inhibit the expression of

stemness-related genes (Oct3/4, Nanog, BMI-1 and Notch1), as well

as suppress self-renewal, migration and chemoresistance in liver

cancer cells under hypoxic conditions (48). Myc is one of the most common

oncogenes in human carcinogenesis, and acts as a bridge between

stem and tumor cells. The Myc family consists of c-Myc, n-Myc and

l-Myc, among which c-Myc serves a key role in HCC pathogenesis. A

previous study showed that miR-17-5p regulates the expression of

c-Myc to influence HCC development (49). The inactivation of Myc enables tumor

cells to de-differentiate into normal liver cell lineages. However,

upon its reactivation, these cells rapidly regain their malignant

characteristics. These tumor cells with stem cell properties are

CSCs. It has been demonstrated that in Myc-induced HCC, the

inactivation and reactivation of Myc can engage certain cells with

stem cell properties (50).

Myc and HIF1A, two stemness-maintaining genes, are

closely associated with central carbon metabolism (CCM) and

proteoglycans in tumors according to KEGG pathway analysis. CCM

primarily involves glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid cycle. CCM

reprogramming occurs in various tumors and serves as the primary

source of cellular energy (51).

The present study revealed that CCM is closely associated with

CSCs. Under aerobic conditions, CSCs exhibit dual metabolic modes,

utilizing glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) as

energy sources that collectively drive tumor progression,

recurrence and drug resistance (52). Glycolysis is a key factor in

maintaining the stemness of HCC-CSCs. The upregulation of

glycolysis-associated genes in HCC-CSCs facilitates the expansion

of CSC populations, augments drug resistance and accelerates tumor

progression (53). For example,

hepatitis B virus X induces Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting

protein 3-like-dependent mitophagy, thereby upregulating glycolytic

metabolism. This metabolic shift modulates CSCs stemness through

elevated expression of cancer stemness-associated genes (such as

ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2, octamer-binding

transcription factor 4 and B-cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia

virus integration site 1), ultimately promoting tumor growth

(54). Furthermore, potassium

calcium-activated channel subfamily N member 4 potentiates

glycolysis in HCC-CSCs, upregulates stemness-associated

transcription factors, expands the HCC-CSCs population, and confers

resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy (55). OXPHOS serves as an alternative

energy source for CSCs. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that

HCC-CSCs exhibit more robust OXPHOS than HCC cell (56). Furthermore, the enhanced OXPHOS

levels in HCC-CSCs can promote stemness maintenance, thereby

increasing tumor metastasis. For example, organic cation/carnitine

transporter 2 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-γ coactivator 1α signaling to potentiate OXPHOS, elevating

EpCAM/CD24 expression, augmenting CSC sphere-forming capacity, and

ultimately driving HCC cell proliferation, migration and invasion

(57).

Proteoglycans, macromolecules composed of core

proteins and glycosaminoglycan chains, have also been implicated in

CSCs (58). These molecules

contribute to the maintenance of the CSC phenotype and facilitate

tumor progression. Glypican-3, a heparan sulfate proteoglycan

subtype, modulates c-Myc activity to regulate the migratory,

invasive and CSC-forming capabilities of HCC cells within hypoxic

tumor microenvironments (59).

Hyaluronic acid (HA) belongs to the glycosaminoglycan family and

CD44 is an HA receptor and a surface marker of HCC-CSCs. TGF-β

affects the expression levels of pluripotent transcription factors

by regulating CD44 subtypes and targeting the MAPK signaling

pathway, mediates the formation ability of HCC-CSCs, promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and increases the invasion and

migration of HCC cells (60). KEGG

pathway analysis indicated that miR-17-5p targeted genes associated

with stemness, metastasis and drug resistance mainly influenced

cell fate and metabolic reprogramming pathways to maintain CSC

survival in harsh microenvironments. Therefore, miR-17-5p may

represent a potential target that serves an essential role in

HCC-CSCs.

The present study had some limitations. First, the

nine studies selected in the systematic review only included

participants of Chinese and Korean ethnicities, which may have led

to bias and missed other potential miRNAs. However, inclusion of

only studies with Chinese and Korean ethnicities was due to the

current evidence base being limited and the reliability of the

present study findings was further validated using pan-ethnic

databases, such as TCGA. Second, a single HCC cell line (Huh7) was

used in the present study and only the expression levels of

miR-17-5p were explored in Huh7 and Huh7-CSCs, suggesting a

potential role for miR-17-5p in HCC-CSCs. In future studies, the

role of miR-17-5p will be explored in a larger population and

multiple cell lines. Direct investigations of miR-17-5p function in

drug resistance, metastasis and recurrence of HCC-CSCs will be

conducted, including miRNA mimic/inhibitor experiments, sphere

formation and drug resistance assays. In summary, miR-17-5p is a

miRNA potentially associated with CSCs, drug resistance, metastasis

and recurrence of HCC through cell fate and metabolic reprogramming

pathways. miR-17-5p exhibited higher expression in Huh7-CSCs

compared with that in Huh7 cells, and may target HIF1A and Myc to

maintain the stemness of HCC-CSCs. However, further experimental

studies are required to validate these hypotheses.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Southwest Medical

University Project (grant no. 2023ZYYJ08), the Sichuan Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 2022YFS0619), the National

Traditional Chinese Medicine Clinical Research Base Construction

Unit of the Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of

Southwest Medical University (grant no. 2018-131), the Luzhou

Science and Technology Innovation Team (grant no. 2021-162-01) and

the Science and Technology Innovation Team of Affiliated

Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical

University (grant no. 2022-CXTD-04).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YJ and XZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. YJ, QP and XZ conducted the systematic review and network

analysis. YKC, XZ and JW designed the study. MP, PZD, DZ, XW, YKC

and JW supervised the experiments and discussion. YJ and XZ wrote

and edited the manuscript. YJ, XW and QP performed the cytological

experiments. XZ, DZ and MP performed the statistical analyses and

interpreted the data. DZ, XW and PZD were involved in reviewing and

editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 380:1450–1462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Qi J, Li M, Wang L, Hu Y, Liu W, Long Z,

Zhou Z, Yin P and Zhou M: National and subnational trends in cancer

burden in China, 2005–20: An analysis of national mortality

surveillance data. Lancet Public Health. 8:e943–e955. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim E and Viatour P: Hepatocellular

carcinoma: Old friends and new tricks. Exp Mol Med. 52:1898–1907.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V

and Singh R: Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment

approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1873:1883142020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhong Y, Yang Y, He L, Zhou Y, Cheng N,

Chen G, Zhao B, Wang Y, Wang G and Liu X: Development of prognostic

evaluation model to predict the overall survival and early

recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

8:301–312. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Makary MS, Khandpur U, Cloyd JM, Mumtaz K

and Dowell JD: Locoregional therapy approaches for hepatocellular

carcinoma: Recent advances and management strategies. Cancers

(Basel). 12:19142020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nakano S, Eso Y, Okada H, Takai A,

Takahashi K and Seno H: Recent advances in immunotherapy for

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 12:7752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Niu L, Liu L, Yang S, Ren J, Lai PBS and

Chen GG: New insights into sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular

carcinoma: Responsible mechanisms and promising strategies. Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1868:564–570. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu J, Liao K and Zhou W: Exosomes regulate

the transformation of cancer cells in cancer stem cell homeostasis.

Stem Cells Int. 2018:48373702018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang Y, Wu G, Fu X, Xu S, Wang T, Zhang Q

and Yang Y: Aquaporin 3 maintains the stemness of CD133+

hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating STAT3. Cell Death Dis.

10:4652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bai X, Ni J, Beretov J, Graham P and Li Y:

Cancer stem cell in breast cancer therapeutic resistance. Cancer

Treat Rev. 69:152–163. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A and Freeman JW:

The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: Therapeutic

implications. J Hematol Oncol. 11:642018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Glumac PM and LeBeau AM: The role of CD133

in cancer: A concise review. Clin Transl Med. 7:182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xiang DM, Sun W, Zhou T, Zhang C, Cheng Z,

Li SC, Jiang W, Wang R, Fu G, Cui X, et al: Oncofetal HLF

transactivates c-Jun to promote hepatocellular carcinoma

development and sorafenib resistance. Gut. 68:1858–1871. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Akbari S, Kunter I, Azbazdar Y, Ozhan G,

Atabey N, Firtina Karagonlar Z and Erdal E: LGR5/R-Spo1/Wnt3a axis

promotes stemness and aggressive phenotype in hepatoblast-like

hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cell Signal. 82:1099722021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics,

biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu X, Wu Y, Zhou Z, Huang M, Deng W, Wang

Y, Zhou X, Chen L, Li Y, Zeng T, et al: Celecoxib inhibits the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer via the

miRNA-145/TGFBR2/Smad3 axis. Int J Mol Med. 44:683–693.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lv T, Jiang L, Kong L and Yang J:

MicroRNA-29c-3p acts as a tumor suppressor gene and inhibits tumor

progression in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting TRIM31. Oncol

Rep. 43:953–964. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J and Altman

DG; PRISMA Group, : Preferred reporting items for systematic

reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med.

6:e10000972009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C,

McNally R and Cheraghi-Sohi S: PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison

study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for

qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 14:5792014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Torre-Healy LA, Berezovsky A and Lathia

JD: Isolation, characterization, and expansion of cancer stem

cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1553:133–143. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xie RT, Cong XL, Zhong XM, Luo P, Yang HQ,

Lu GX, Luo P, Chang ZY, Sun R, Wu TM, et al: MicroRNA-33a

downregulation is associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis

in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett.

15:4571–4577. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhuang L, Xu L, Wang P and Meng Z: Serum

miR-128-2 serves as a prognostic marker for patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 10:e01172742015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sun J, Fang K, Shen H and Qian Y:

MicroRNA-9 is a ponderable index for the prognosis of human

hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8:17748–17756.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen HY, Han ZB, Fan JW, Xia J, Wu JY, Qiu

GQ, Tang HM and Peng ZH: miR-203 expression predicts outcome after

liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic

liver. Med Oncol. 29:1859–1865. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhou N, Wu J, Wang X, Sun Z, Han Q and

Zhao L: Low-level expression of microRNA-375 predicts poor

prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 37:2145–2152.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Luo C, Pu J, Liu F, Long X, Wang C, Wei H

and Tang Q: MicroRNA-200c expression is decreased in hepatocellular

carcinoma and associated with poor prognosis. Clin Res Hepatol

Gastroenterol. 43:715–721. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ha SY, Yu JI, Choi C, Kang SY, Joh JW,

Paik SW, Kim S, Kim M, Park HC, Park CK, et al: Prognostic

significance of miR-122 expression after curative resection in

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 9:147382019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhu HT, Dong QZ, Sheng YY, Wei JW, Wang G,

Zhou HJ, Ren N, Jia HL, Ye QH and Qin LX: MicroRNA-29a-5p is a

novel predictor for early recurrence of hepatitis B virus-related

hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. PLoS One.

7:e523932012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen L, Jiang M, Yuan W and Tang H:

miR-17-5p as a novel prognostic marker for hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Invest Surg. 25:156–161. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zenlander R, Salter H, Gilg S, Eggertsen G

and Stål P: MicroRNAs as plasma biomarkers of hepatocellular

carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis-A cross-sectional study.

Int J Mol Sci. 25:24142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB and Bartel

DP: Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome

Res. 19:92–105. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gebrie A: Disease progression role as well

as the diagnostic and prognostic value of microRNA-21 in patients

with cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS

One. 17:e02684802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li D, Wang T, Sun FF, Feng JQ, Peng JJ, Li

H, Wang C, Wang D, Liu Y, Bai YD, et al: MicroRNA-375 represses

tumor angiogenesis and reverses resistance to sorafenib in

hepatocarcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 28:126–140. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang D and Yang J: MiR-375 attenuates

sorafenib resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by

inhibiting cell autophagy. Acta Biochim Pol. 70:239–246.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen Y, Xu H, Tang H, Li H, Zhang C, Jin S

and Bai D: miR-9-5p expression is associated with vascular invasion

and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma, and in vitro

verification. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:14657–14671. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lu Z, Li X, Xu Y, Chen M, Chen W, Chen T,

Tang Q and He Z: microRNA-17 functions as an oncogene by

downregulating Smad3 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell

Death Dis. 10:7232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wang X, Li F, Cheng J, Hou N, Pu Z, Zhang

H, Chen Y and Huang C: MicroRNA-17 family targets RUNX3 to increase

proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev

Eukaryot Gene Expr. 33:71–84. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shan SW, Fang L, Shatseva T, Rutnam ZJ,

Yang X, Du W, Lu WY, Xuan JW, Deng Z and Yang BB: Mature miR-17-5p

and passenger miR-17-3p induce hepatocellular carcinoma by

targeting PTEN, GalNT7 and vimentin in different signal pathways. J

Cell Sci. 126:1517–1530. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu YC, Yeh CT and Lin KH: Cancer stem

cell functions in hepatocellular carcinoma and comprehensive

therapeutic strategies. Cells. 9:13312020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kim YJ, Yuk N, Shin HJ and Jung HJ: The

natural pigment violacein potentially suppresses the proliferation

and stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. Int J Mol

Sci. 22:107312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Prager BC, Xie Q, Bao S and Rich JN:

Cancer stem cells: The architects of the tumor ecosystem. Cell Stem

Cell. 24:41–53. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li L and Bhatia R: Molecular pathways:

Stem cell quiescence. Clin Cancer Res. 17:4936–4941. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Song S, Ma D, Xu L, Wang Q, Liu L, Tong X

and Yan H: Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound-generated singlet oxygen

induces telomere damage leading to glioma stem cell awakening from

quiescence. iScience. 25:1035582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zou R, Liu Y, Qiu S, Lu Y, Chen Y, Yu H,

Zhu H, Zhu W, Zhu L, Feng J and Han J: The identification of

N6-methyladenosine-related miRNAs predictive of hepatocellular

carcinoma prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy. Cancer Biomark.

38:551–566. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lequeux A, Noman MZ, Xiao M, Van Moer K,

Hasmim M, Benoit A, Bosseler M, Viry E, Arakelian T, Berchem G, et

al: Targeting HIF-1 alpha transcriptional activity drives cytotoxic

immune effector cells into melanoma and improves combination

immunotherapy. Oncogene. 40:4725–4735. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Cui CP, Wong CCL, Kai AKL, Ho DWH, Lau

EYT, Tsui YM, Chan LK, Cheung TT, Chok KSH, Chan ACY, et al: SENP1

promotes hypoxia-induced cancer stemness by HIF-1α deSUMOylation

and SENP1/HIF-1α positive feedback loop. Gut. 66:2149–2159. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

EI Tayebi HM, Omar K, Hegy S, EI Maghrabi

M, EI Brolosy M, Hosny KA, Esmat G and Abdelaziz AI: Repression of

miR-17-5p with elevated expression of E2F-1 and c-MYC in

non-metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma and enhancement of cell

growth upon reversing this expression pattern. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 434:421–427. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Shachaf CM and Felsher DW: Tumor dormancy

and MYC inactivation: Pushing cancer to the brink of normalcy.

Cancer Res. 65:4471–4474. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ebrahimi KH, Gilbert-Jaramillo J, James WS

and McCullagh JSO: Interferon-stimulated gene products as

regulators of central carbon metabolism. FEBS J. 288:3715–3726.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Snyder V, Reed-Newman TC, Arnold L, Thomas

SM and Anant S: Cancer stem cell metabolism and potential

therapeutic targets. Front Oncol. 8:2032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Xia H, Huang Z, Xu Y, Yam JWP and Cui Y:

Reprogramming of central carbon metabolism in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 153:1134852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen YY, Wang WH, Che L, Lan Y, Zhang LY,

Zhan DL, Huang ZY, Lin ZN and Lin YC: BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy

promotes hbx-induced cancer stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma

cells via glycolysis metabolism reprogramming. Cancers (Basel).

12:6552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Fan J, Tian R, Yang X, Wang H, Shi Y, Fan

X, Zhang J, Chen Y, Zhang K, Chen Z and Li L: KCNN4 promotes the

stemness potentials of liver cancer stem cells by enhancing glucose

metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 23:69582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu G, Luo Q, Li H, Liu Q, Ju Y and Song

G: Increased oxidative phosphorylation is required for stemness

maintenance in liver cancer stem cells from hepatocellular

carcinoma cell line HCCLM3 cells. Int J Mol Sci. 21:52762020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yang T, Liang N, Zhang J, Bai Y, Li Y,

Zhao Z, Chen L, Yang M, Huang Q, Hu P, et al: OCTN2 enhances

PGC-1α-mediated fatty acid oxidation and OXPHOS to support stemness

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Metabolism. 147:1556282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wang W, Han N, Xu Y, Zhao Y, Shi L, Filmus

J and Li F: Assembling custom side chains on proteoglycans to

interrogate their function in living cells. Nat Commun.

11:59152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yao G and Yang Z: Glypican-3 knockdown

inhibits the cell growth, stemness, and glycolysis development of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells under hypoxic microenvironment

through lactylation. Arch Physiol Biochem. 130:546–554.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Aguilar-Chaparro MA, Rivera-Pineda SA,

Hernández-Galdámez HV, Ríos-Castro E, Garibay-Cerdenares OL,

Piña-Vázquez C and Villa-Treviño S: Transforming growth factor-β

modulates cancer stem cell traits on CD44 subpopulations in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 126:e700032025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|