Introduction

Cancer is among the most notable challenges to

global public health because of its high prevalence, molecular

heterogeneity and tendency towards therapy resistance. According to

the GLOBOCAN 2022 report, an estimated 19.96 million new cancer

cases and 9.74 million cancer deaths occurred worldwide in 2022

(1). The identification of the

following 14 cancer hallmarks in human tumors has markedly

influenced the understanding of malignant progression in recent

decades (2,3): Sustaining proliferative signaling,

evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling

replicative immortality, inducing or accessing vasculature,

activating invasion and metastasis, deregulating cellular

metabolism, avoiding immune destruction, genome instability and

mutation, tumor-promoting inflammation, senescent cells,

polymorphic microbiomes, nonmutational epigenetic reprogramming and

unlocking phenotypic plasticity. Despite major advances in targeted

therapies and immuno-oncology, clinical treatments continue to face

three major obstacles: i) Intrinsic and acquired therapy

resistance; ii) recurrence driven by the reactivation of dormant

cancer cells; and iii) metastasis resulting from tumor evolution.

These challenges highlight the urgent need for novel therapeutic

targets and precision interventions to improve clinical outcomes in

the future.

Ribosome-binding protein 1 (RRBP1), a key protein in

endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-ribosome binding, serves pleiotropic

roles in tumorigenesis and progression. Through its regulation of

organelle dynamics and protein synthesis, RRBP1 promotes malignant

phenotypes such as cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis and

chemoresistance. Notably, RRBP1 is upregulated in various cancer

types, such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer and bladder cancer,

and its expression levels are positively associated with advanced

clinical stages and poor prognosis (4–10).

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of RRBP1 provides insights

into dysregulated organelle communication and offers a potential

foundation for the development of therapies targeting subcellular

interactions. The present review systematically describes the roles

of RRBP1 in cancer, emphasizing its functional diversity. It first

outlines the structural features and functions of RRBP1, then

analyzes its expression and regulatory mechanisms across several

cancer types. Lastly, it evaluates the potential of RRBP1 as a

therapeutic target and proposes combined strategies targeting

organelle interaction networks to potentially enhance treatment

efficacy, with the goal of expanding future research directions in

precision oncology.

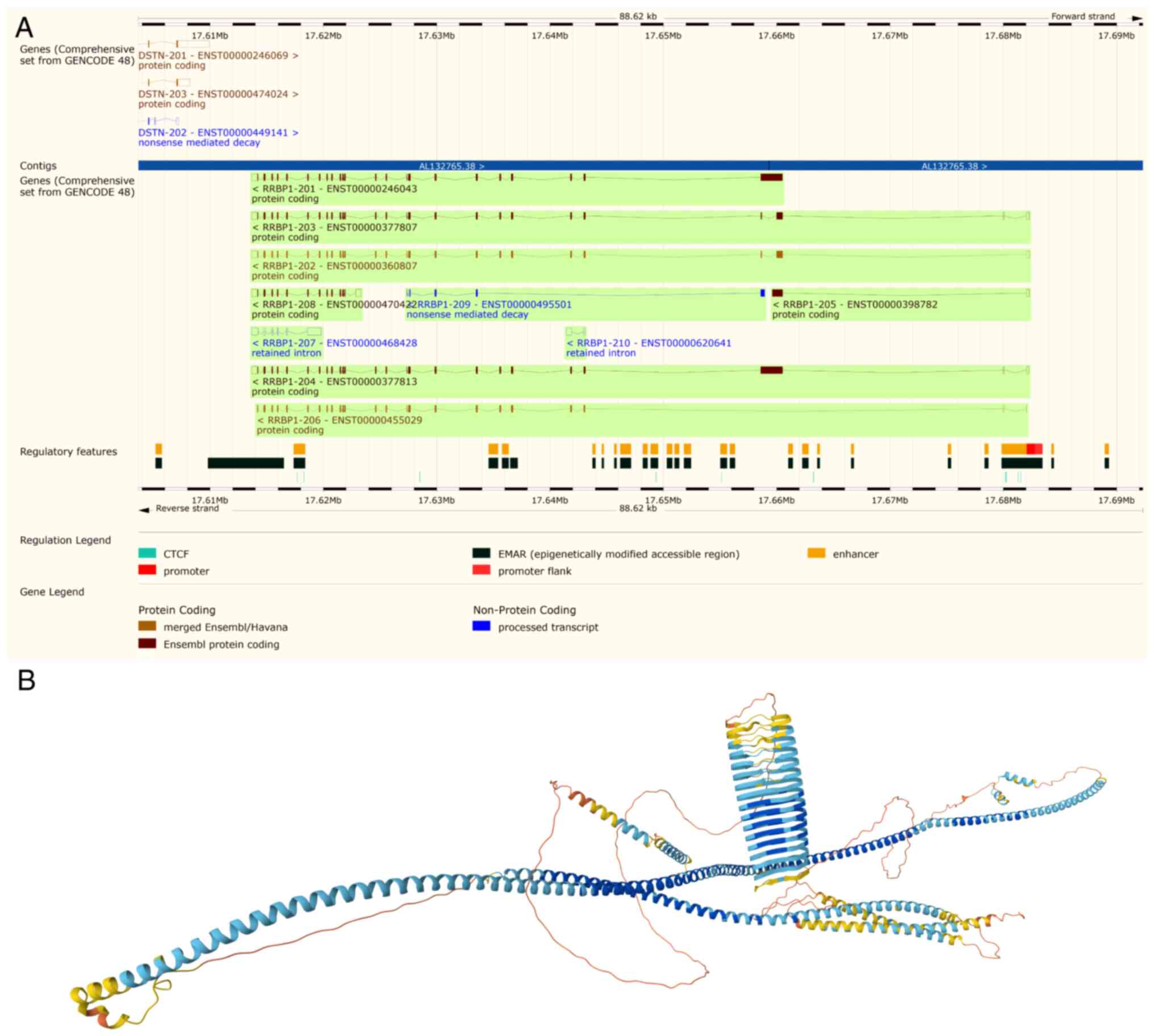

Function of RRBP1

RRBP1, also known as p180 because of its molecular

weight, is a ribosome-binding protein that localizes in the ER

membrane and is essential for the transport of newly synthesized

proteins (11). The gene structure

of RRBP1, featuring multiple splicing variants and its predicted

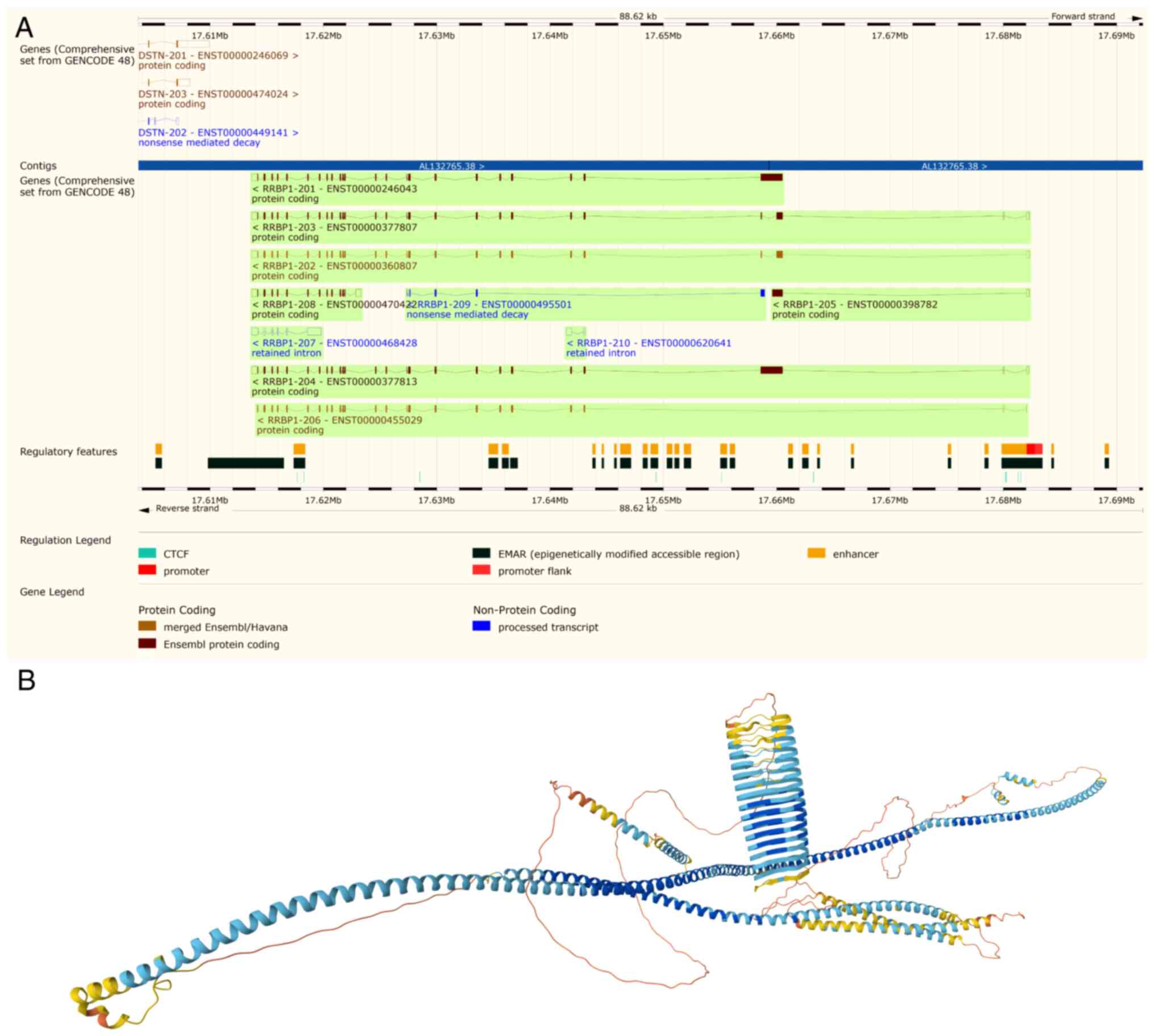

protein architecture, is detailed in Fig. 1. The present review used the Ensembl

Genome Browser (release 114; http://www.ensembl.org/) to display the genomic

structure of RRBP1, highlighting its splice variants, including the

MANE select transcript RRBP1-204 (Fig.

1A). Then the present review used AlphaFold (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/) to predict the 3D

protein structure of RRBP1 (UniProt ID, Q9P2E9), emphasizing its

characteristic long α-helical segments and coiled-coil architecture

(Fig. 1B). RRBP1 consists of a

hydrophobic NH2-terminus and an acidic coiled

COOH-terminal structural domain. The former includes a

transmembrane structural domain and a highly conserved tandem

repeat sequence (ribosome-binding structural domain), whereas the

latter contains a lysine-rich region and a PDZ-binding structural

domain (12–14). These structures enable RRBP1 to

interact efficiently with ribosomes, ER and other cellular

components.

| Figure 1.Schematic of RRBP1 gene

structure and predicted 3D protein conformation. (A) RRBP1

gene from Ensembl, revealing various splicing variants, coding and

non-coding transcripts and regulatory features. The default

transcript (MANE Select) is RRBP1-204. Visualization adapted from

the Ensembl Genome Browser (RRBP1, release 114, EMBL-EBI,

http://www.ensembl.org). (B) Predicted protein

structure of RRBP1. The color gradient from blue to yellow

indicates the predicted local distance difference test confidence

score (blue, high confidence; yellow/orange, low confidence). The

structure reveals the characteristic long α-helical segments and

coiled-coil architecture of RRBP1. Predicted protein structure from

the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (UniProt ID, Q9P2E9,

DeepMind and EMBL-EBI, http://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). RRBP1, ribosome-binding

protein 1; EMBL-EBI, European Molecular Biology Laboratory-European

Bioinformatics Institute; MANE, matched annotation. |

Role of RRBP1 in the regulation of

protein synthesis and translation

Although RRBP1 was originally described as a

ribosomal receptor, this type III transmembrane protein on the ER

is also specifically involved in ER-dependent translational

regulatory mechanisms, such as the mRNA localization of placental

alkaline phosphatase, collagens Iα1 plus Iα2, IIIγ and

calreticulin, by directing their binding to ER membranes (15). Furthermore, RRBP1 promotes the

localization and anchoring of specific mRNAs through a

ribosome-independent mechanism (16). RRBP1 regulates the assembly of

multimer/protein complexes through its C-terminal structural

domain, thereby promoting translational activity (17). In collagen secretory cells, RRBP1

preferentially enhances the efficiency of secretory protein

biosynthesis by strengthening the association of ribosomes with the

ER membrane and it promotes the efficiency of multimer formation,

thus highlighting its central role in efficient translation in

specialized secretory cells (17).

Notably, the finding that RRBP1 deletion induces compensatory

upregulation of signal recognition particle (SRP) receptor subunits

(SRα/SRβ) potentially indicates a functional complementarity with

SRP-dependent pathways (15).

However, since the ER binding rate of Sec61β mRNA was not markedly

altered after knockdown of RRBP1, its ER localization may be

achieved through a pathway independent of RRBP1 and multiple

mechanisms may coordinate the targeting and synthesis of

tail-anchored proteins (18). For

example, in the case of Sec61β mRNA, localization can occur

independently of active translation yet is enhanced by translation,

its ORF sequence appears to harbor elements mediating ER anchoring

and some transcripts may engage translocon-bound ribosomes for

closer membrane proximity (18). In

addition, certain affected transmembrane proteins translocate from

the ER to the mitochondria, thereby revealing a potential role of

RRBP1 in cellular intercompartmental communication (15). Furthermore, yeast two-hybrid

analyses have indicated that the C-terminal region of RRBP1

interacts with the kinesin family member 5B (KIF5B) (19), which has markedly high expression in

a variety of cancer cell lines (13), such as MCF-7, HeLa and U2OS cells

(20). RRBP1, a receptor for KIF5B,

is involved in vesicle transport or mRNA localization of ER origin

and its role of combining ribosomes with kinesins suggests its

potential involvement in tumor transport or tumor cell invasion

processes.

Roles of RRBP1 in organelle

interactions

Mitochondria-ER contacts (MERCs), which serve as an

interface for communication between ER and mitochondria, are

involved in regulating mitochondrial energy metabolism homeostasis,

membrane phospholipid remodeling, programmed cell death signaling

and other core biological processes by mediating calcium-ion

dynamic homeostasis and the exchange of intermediates in lipid

metabolism (21). Abnormal function

of MERCs can interfere with the synergistic network of cellular

organelles and thus lead to tumorigenesis, neurodegenerative

diseases and cardiovascular system dysfunction (21); therefore, MERCs might have potential

value as targets for disease intervention. RRBP1 mediates MERC

formation through a specific transmembrane interaction between its

PDZ-binding domain and the PDZ domain of the mitochondrial protein

synaptojanin-2 binding protein (SYNJ2BP). This interaction notably

regulates mitochondrial DNA replication and spatial organization,

thereby modulating mitochondrial genomic stability and functional

dynamics (14,21,22).

Protein translation inhibitors such as puromycin disrupt the

RRBP1-SYNJ2BP interaction and specifically eliminate mitochondrial

contacts with ribosome-enriched rough ER (14). Knockdown of RRBP1 almost completely

eliminates ribosome-rich rough ER contact sites (riboMERCs),

leaving only certain smooth-type contact sites and leads to a

decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential; therefore, RRBP1

appears to be essential for mitochondrial function (21). Glycoprotein (Gp)78 ubiquitin ligase

activity regulates the size and tubular morphology of riboMERCs.

Gp78 upregulation induces the formation of extended riboMERCs in

COS-7 and HeLa cells in the presence of RRBP1 (21). This mechanism suggests that RRBP1

provides a structural basis and Gp78 finely regulates the

complexity of the contact sites through a ubiquitination-dependent

pathway. In addition, dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency disrupts

RRBP1-SYNJ2BP interactions and leads to defects in mitochondrial

DNA distribution (22).

Dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency indirectly affects ER lamellar

structure and RRBP1 function by interfering with mitochondrial

division dynamics (22), thus

suggesting a key role of ER-mitochondrial synergistic interactions

in mitochondrial genome regulation.

Furthermore, the ER-mitochondrial contact site also

serves a key role in mitochondrial autophagy. RRBP1 mediates

selective mitophagy induced by mitochondrial protein import stress

(MPIS) through dynamic subcellular relocalization (perinuclear

rough ER to peripheral ER). Under MPIS conditions, the

cytosolic-retained Nod-like receptor protein nucleotide-binding,

leucine-rich repeat X1 forms a complex with RRBP1 and drives

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 lipidation and

autophagosome formation. This process is independent of the

canonical phopsphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1

(PINK1)-parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PRKN) pathway and

preferentially uses ER-mitochondria contact sites as membrane

sources (23,24). RRBP1 exhibits dual functionality; it

assists in localized translational recovery during acute stress but

switches to a pro-autophagic mode under prolonged stress. The

interaction between RRBP1 and splicing factor, proline- and

glutamine-rich, suggests a potential role of RRBP1 in regulating

the subcellular localization of mitochondrially-associated mRNAs

during stress recovery (23).

Notably, PINK1 and PRKN are genetic risk factors for Parkinson's

disease and accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial

quality control defects are a key molecular basis for

neurodegeneration (24–27). Consistent with this possibility,

Sierksma et al (28) have

identified RRBP1 as a subthreshold Alzheimer's disease risk

gene. In parallel with its stress-adaptive function, RRBP1

modulates ER ribosome interactions in neurons. RRBP1 is enriched in

the ER tubules of neuronal axons and is virtually absent in

dendrites. Nerve growth factor neurotrophin-3 specifically enhances

ER-ribosome interactions through RRBP1, whereas brain-derived

neurotrophic factor/nerve growth factor has no such effect, thus

suggesting selective regulation of the signaling pathway (29). In addition, the identification of

RRBP1 in the neuromuscular junction has confirmed its specific

distribution in the synaptic region. RRBP1 may be involved in the

localization of synaptic proteins by binding the kinesin KIF5B,

which might serve as a novel candidate target for exploring the

mechanisms of neuromuscular diseases (30). Whether mediating MPIS-induced

mitochondrial autophagy or regulating axonal ER-ribosome dynamics,

RRBP1 functions as a sub-stable hub at the organelle-membrane

interface.

Roles of RRBP1 in lipid

metabolism

RRBP1 has been identified as a key gene in

the regulation of lipid levels in an integrated multi-omics study

(31). Observations that RRBP1

expression quantitative trait loci markedly co-localize with

genetic association signals for low-density lipoprotein, total

cholesterol and non-high-density lipoprotein suggest that

RRBP1 is an effector gene for lipid-related genetic

variation (31). RRBP1 is markedly

upregulated in adipose stem and progenitor cells in the

subcutaneous adipose tissue of mice with obesity induced by a

high-fat diet (32). In addition, a

cellular compartment in hepatocytes, denoted wrappER, has been

identified to functionally and structurally integrate all

hepatocyte systems and intracellular fatty acid elimination

pathways (33). When RRBP1

expression is inhibited in the liver, the uniform juxtaposition

between wrappER and mitochondria is disrupted and localized

abnormal bumps form (33). When the

complex comprising RRBP1 and SYNJ2BP is not functional, the

directional flow of fatty acids from the ER to the mitochondria is

impeded and lipids abnormally accumulate in liver cells; therefore,

the RRBP1-SYNJ2BP axis directly influences the balance of liver

lipid stability by modulating the physical properties of the

membrane-contact interface (33).

In parallel, RRBP1 silencing decreases very low-density lipoprotein

biosynthesis and triggers intrahepatic triglyceride and free fatty

acid accumulation, which in turn markedly increases lipid droplet

accumulation and the expression level of the lipid droplet marker

perilipin 2 (34). These findings

demonstrated that RRBP1 is important in regulating hepatic lipid

metabolic homeostasis by maintaining the structural integrity of

the contact between the ER and mitochondria.

Roles of RRBP1 in various types of

cancer

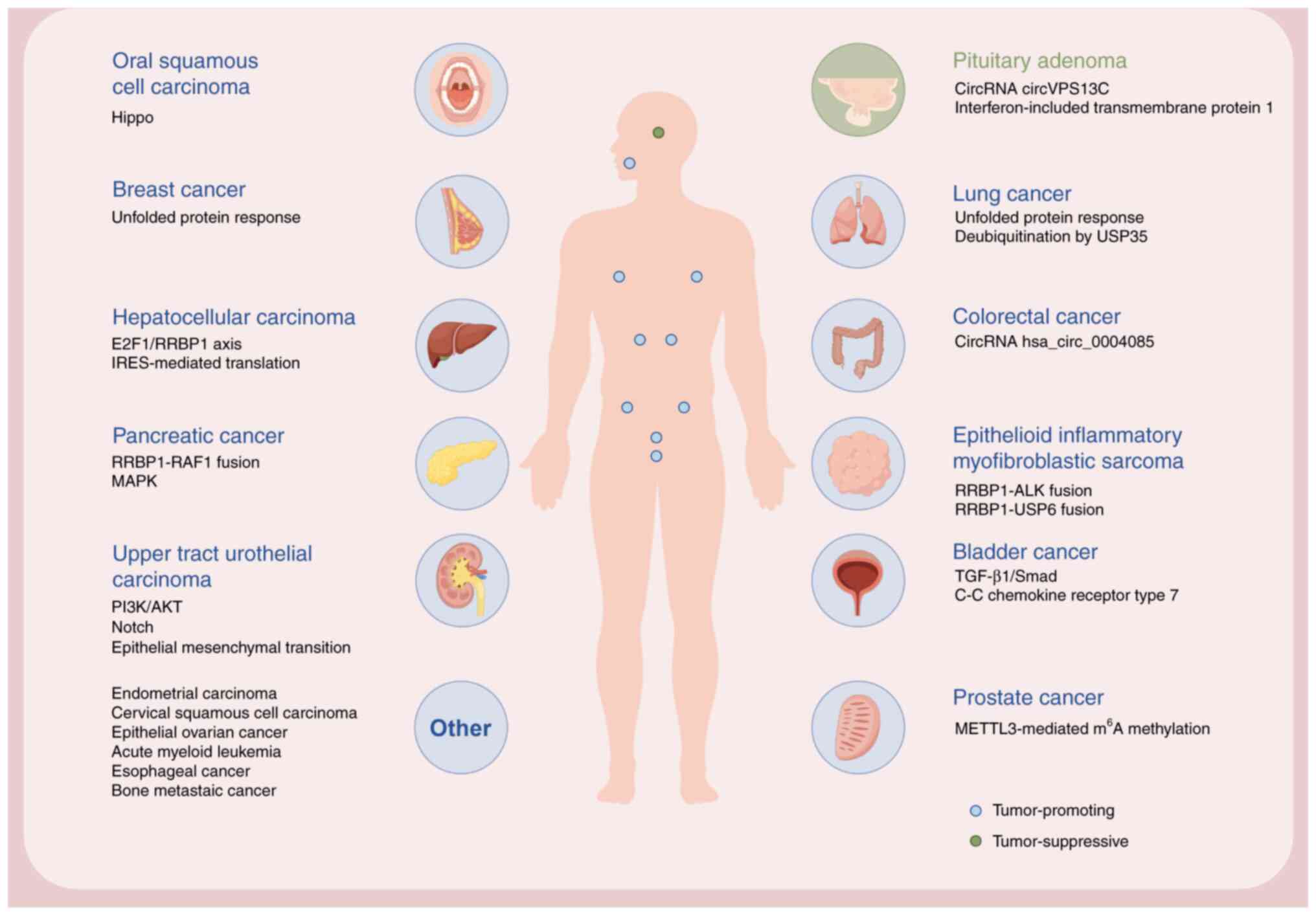

RRBP1 serves important regulatory roles in cancer

genesis and evolution. Due to its role in organelle interactions,

its molecular mechanisms and pathological associations are

receiving increasing attention (8,9,35–37).

RRBP1 influences tumor metabolic reprogramming and

microenvironmental adaptation by dynamically regulating substance

transport and signaling between subcellular compartments and

therefore might have translational value as a potential therapeutic

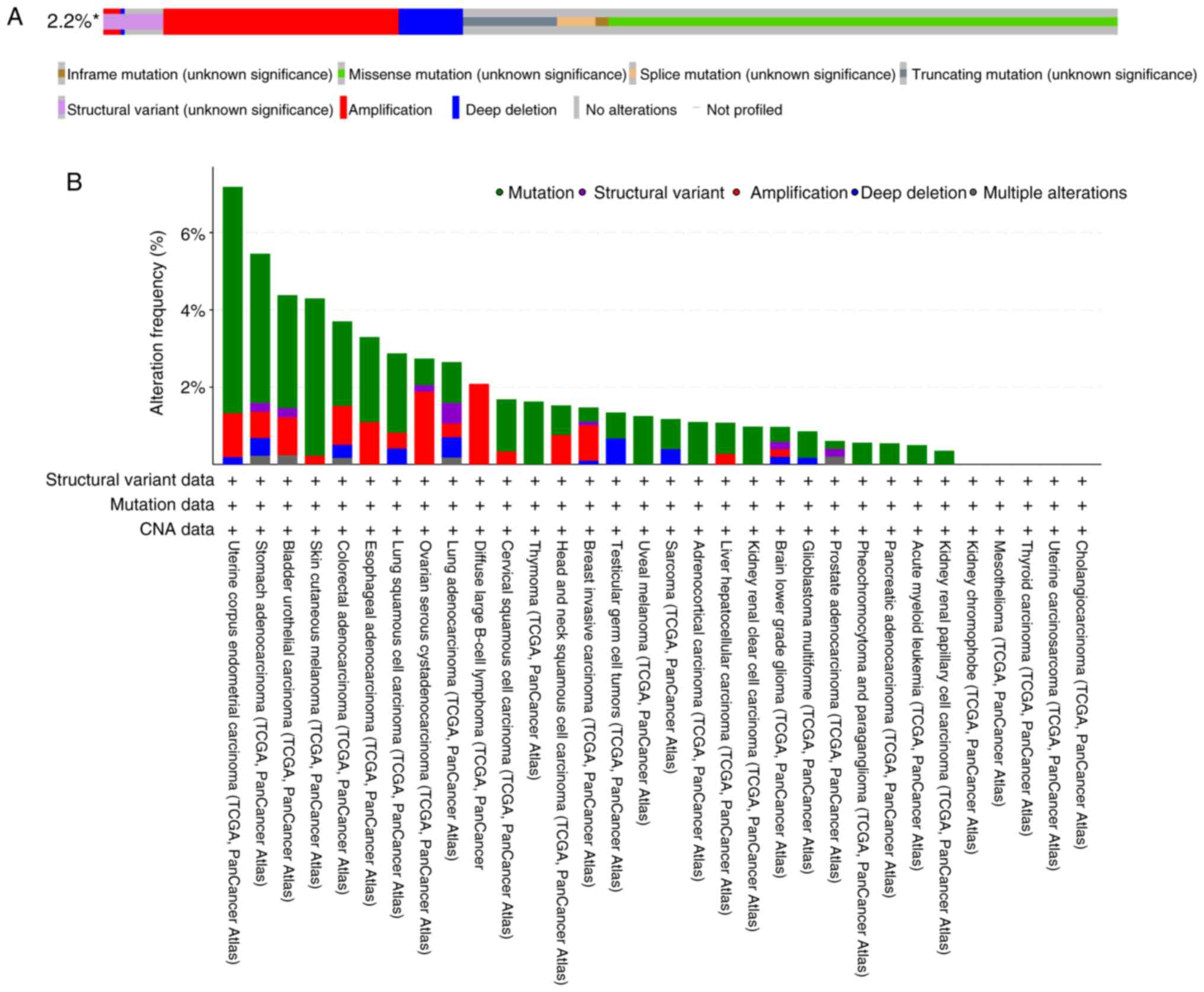

target. To comprehensively evaluate the contributions of genetic

alterations to RRBP1-driven oncogenesis, the present review

characterized the oncogenic status of RRBP1 across multiple cancer

types using the cBioPortal database for Cancer Genomics platform

(https://www.cbioportal.org/) (Fig. 2). Based on The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) Pan-Cancer Atlas studies, the present review generated an

OncoPrint visualization map depicting the types and occurrence

frequencies of RRBP1 genetic alterations, while also

illustrating the lineage distribution characteristics of specific

RRBP1 mutations. Among 10,967 samples, 237 samples exhibited

RRBP1 alterations, accounting for ~2.2% of all cases

(Fig. 2A). These alterations were

primarily missense mutations. Among these, uterine corpus

endometrial carcinoma, stomach adenocarcinoma, bladder urothelial

carcinoma and skin cutaneous melanoma exhibited relatively high

alteration frequencies (>4%) (Fig.

2B). By contrast, because the RRBP1 gene in

cholangiocarcinoma, uterine carcinosarcoma, thyroid carcinoma,

mesothelioma and kidney chromophobe demonstrated no changes

(Fig. 2B), the oncogenic role of

RRBP1 in these cancer types may be limited.

The following section discusses research progress on

RRBP1 in tumors and explores the precision therapeutic potential of

targeting RRBP1 or its microenvironmental adaptors according to its

multiple regulatory mechanisms.

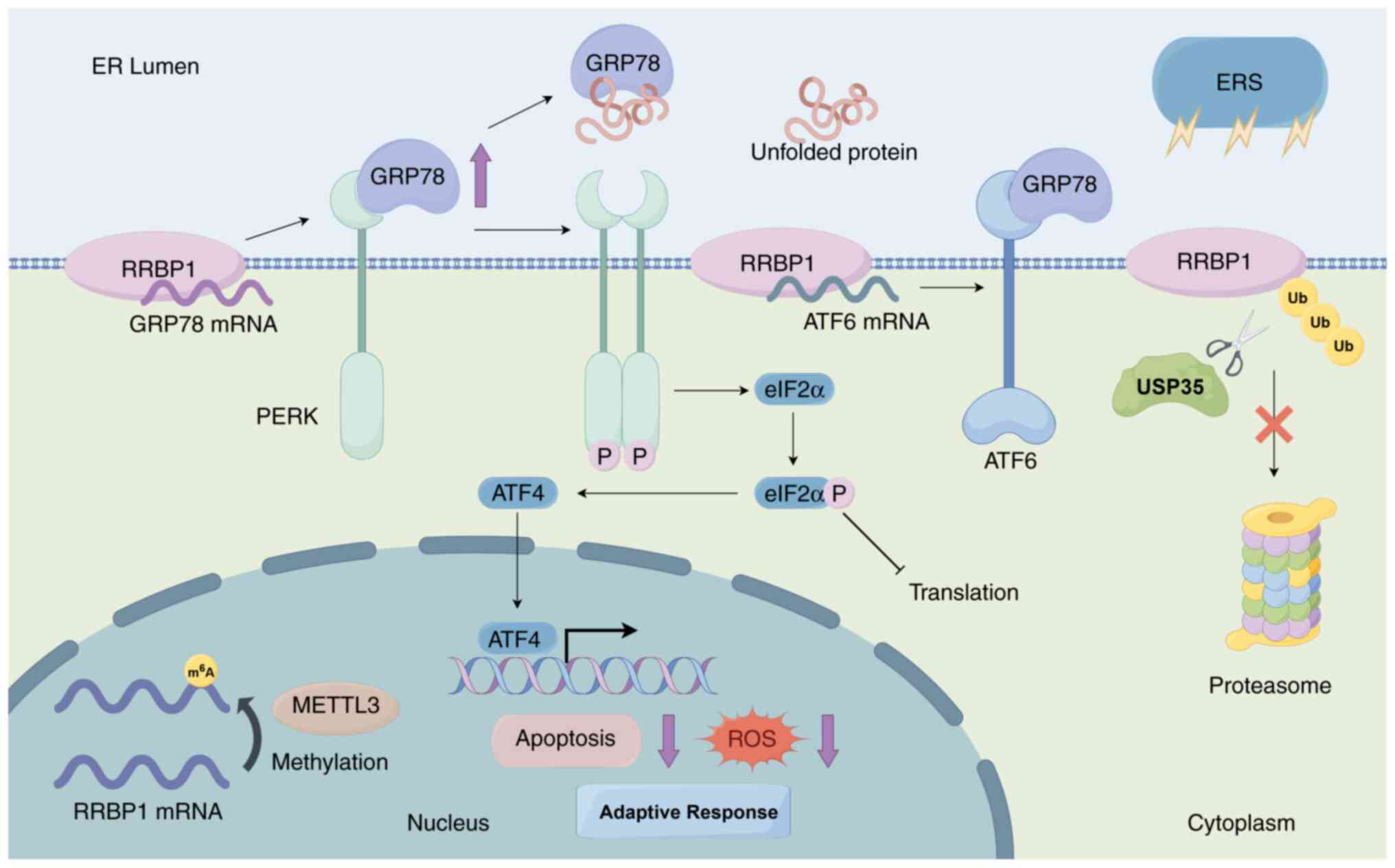

Lung cancer

A previous study reported that several mutated

genes, including RRBP1, have been identified to be enriched

primarily in nucleoplasmic localization and DNA repair-related

biological processes (38) and

therefore, may be involved in genetic susceptibility to lung

adenocarcinoma by influencing the DNA damage response mechanism. In

addition, RRBP1 is markedly upregulated in lung cancer tissues and

its upregulation is associated with early tumor stages (36). RRBP1 is also associated with the

unfolded protein response (UPR), a central mechanism through which

tumor cells respond to ER stress (ERS) (36). Cells rely on the ER to properly fold

and process secreted proteins and membrane proteins; however, when

protein folding is disrupted by various physiological or

pathological stimuli, such as deficient autophagy, energy

deprivation, inflammatory challenges and hypoxia, misfolded or

unfolded proteins accumulate, in the condition known as ERS

(39). To restore ER homeostasis,

cells activate an adaptive mechanism, the UPR, which is mediated by

three classic ER-resident sensors: Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α,

protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) and

activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (40). The UPR decreases global protein

synthesis, enhances the production of molecular chaperones and

promotes the degradation of misfolded proteins, thereby alleviating

the burden on the ER (40).

Although the UPR is initially protective, a prolonged or unresolved

UPR may trigger apoptotic signals, thus serving dual roles in cell

survival and death. Tumor cells undergo persistent ERS because of

rapid proliferation and a harsh microenvironment and must rely on

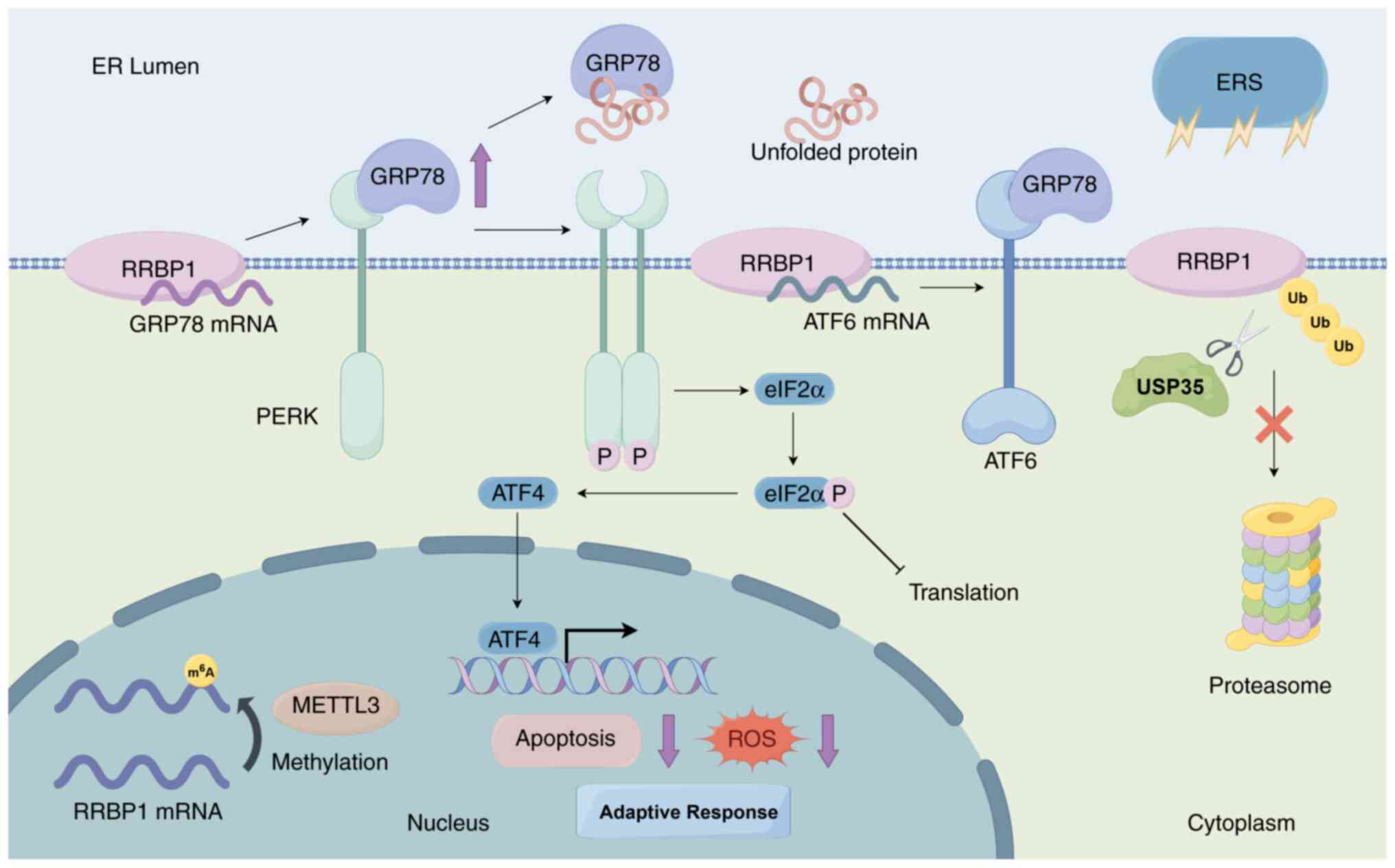

the UPR to maintain their survival. Glucose-regulated protein 78

(GRP78), a regulator of the UPR, is markedly upregulated in lung

cancer. However, when GRP78 is upregulated, it dissociates from the

UPR signaling sensor PERK; therefore, PERK dimerizes and undergoes

autophosphorylation (36,41). Phosphorylated PERK further catalyzes

the phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor

eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), thus leading to

translational repression, a core adaptive strategy enabling cells

to cope with mild ERS (Fig. 3)

(36,41). Tsai et al (36) have demonstrated that knockdown of

RRBP1 exacerbates ERS and markedly decreases cell viability and

tumor formation. This knockdown also markedly decreases ATF6 mRNA

levels; therefore, RRBP1 might be involved in the UPR by regulating

the mRNA stability of ATF6 (Fig. 3)

(36). By contrast, upregulation of

RRBP1 enhances the anti-apoptotic ability of tumor cells. RRBP1

protects cells against ERS-induced apoptosis by upregulating the

expression level of GRP78 and simultaneously decreasing the

accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (36). Therefore, RRBP1 regulates the UPR by

maintaining the mRNA stability of GRP78, which in turn helps lung

cancer cells adapt to ERS and chemotherapeutic stress and maintains

tumor survival and progression. Furthermore, in non-small cell lung

cancer, elevated expression of ubiquitin-specific processing

protease 35 (USP35) markedly upregulates RRBP1 protein levels

(41). USP35 stabilizes RRBP1

protein by directly binding RRBP1 and catalyzing its

deubiquitination modification, thereby inhibiting the

proteasome-mediated degradation pathway (Fig. 3) (41). The USP35/RRBP1 axis exerts a

protective effect through a dual mechanism; it enhances GRP78

expression and PERK phosphorylation levels (adaptive UPR signaling)

but also inhibits the CHOP-caspase3 apoptotic pathway, thus

markedly decreasing apoptosis (41).

| Figure 3.RRBP1 adapts to ERS through the UPR

and enhancement of self-stabilization. RRBP1 upregulates GRP78

expression by stabilizing GRP78 mRNA and regulates ATF6 mRNA to

stabilize ATF6 for participation in the UPR. In addition, RRBP1

inhibits degradation pathways through METTL3-mediated m6A

methylation and USP35-mediated deubiquitination, thus enhancing

self-stability and promoting adaptive stress signaling. RRBP1,

ribosome-binding protein 1; Ub, ubiquitin; UPR, unfolded protein

response; ERS, endoplasmic reticulum stress; GRP78,

glucose-regulated protein 78; ROS, reactive oxygen species; METTL3,

methyltransferase-like 3; USP35, ubiquitin-specific processing

protease 35; ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; m6A,

N6-methyladenine; PERK, protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum

kinase. |

Breast cancer

The mRNA and protein expression levels of RRBP1 in

breast cancer tissues are markedly higher compared with those in

normal tissues (4). RRBP1

expression is markedly associated with breast cancer histological

grade, human EGFR 2 (HER-2) status, p53 status and molecular

subtypes; furthermore, in patients with HER-2+ breast

cancer, increased RRBP1 expression is associated with worse overall

survival (OS) (4). The upregulation

of RRBP1 protein localizes primarily in the perinuclear region of

the cytoplasm (13). Normal breast

tissues demonstrate only weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining,

whereas the staining intensity is markedly enhanced in cancerous

tissues. RRBP1 expression is higher in malignant breast cancer

types compared with that in benign or proliferative lesions;

however, no gradient in RRBP1 expression has been observed in

benign or proliferative conditions (13). RRBP1 expression and lymph node

metastasis (LNM) are independent prognostic factors for OS in

patients with HER-2+ breast cancer, according to a

multivariate analysis (4). RRBP1

upregulation markedly influences survival in patients with

early-stage breast cancer, but this association has not been

observed in patients with advanced-stage types of cancer (4). RRBP1 promotes breast cancer cell

survival by participating in the UPR and this mechanism might

underlie its association with poor prognoses in patients with

HER-2+ breast cancer (4).

Liver cancer

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) studies, RRBP1 has

been shown to serve a key role in high glucose-mediated tumor

malignant progression through the E2F transcription factor 1

(E2F1)/RRBP1 signaling pathway (42). He et al (42) have reported that high glucose

treatment markedly upregulates the mRNA and protein expression

levels of RRBP1 in HepG2 cells, whereas knockdown of RRBP1 markedly

inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasive ability. RRBP1

has been suggested to be a core molecule mediating the pro-cancer

effect of high glucose. Furthermore, RRBP1 expression under

cellular stress conditions relies on an internal ribosome entry

site (IRES)-mediated translation mechanism (43). IRES elements are structured RNA

motifs within the 5′-untranslated regions of select mRNAs that

enable cap-independent initiation of translation (44). Under stress conditions, when

canonical cap-dependent protein synthesis is compromised, IRES

elements directly recruit the 40S ribosomal subunit, often with

assistance from IRES trans-acting factors, thereby sustaining the

translation of specific transcripts key for cell survival,

adaptation and reprogramming (44).

Notably, in cancer, dysregulated IRES-mediated translation and IRES

trans-acting factor activity have been implicated in tumorigenesis

and therapeutic resistance (45).

The 5′-untranslated region of RRBP1 mRNA has IRES activity, which

is markedly enhanced under chemotherapeutic drug treatment or serum

starvation (43). The La

autoantigen facilitates ribosome recruitment by binding the core

region of the IRES (−237 to −58 nt), whose two Gdf5 regulatory

region loop structures are essential for La protein binding

(43). In human HCC cells, RRBP1

protein levels are elevated under the aforementioned stress

conditions, but its mRNA transcripts do not markedly change, thus

suggesting that the enhancement of translational efficiency

originates from an IRES-dependent mechanism (43). Particularly, chemotherapeutic drugs

activate IRES-mediated translation by upregulating the expression

level of La protein, whereas serum starvation induces La protein

translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, both of which work

together in activating IRES-mediated translation (43).

In summary, RRBP1 drives tumor malignant progression

in high glucose environments through the E2F1/RRBP1 signaling axis

and E2F1 directly binds RRBP1, and enhances its transcriptional

activity, thereby promoting HCC cell proliferation, migration and

invasion. Under chemotherapeutic or serum starvation conditions,

RRBP1 enhances the efficiency of protein synthesis through an

IRES-mediated translation mechanism, which in turn enhances the

survival of HCC cells in adverse conditions. This mechanism does

not depend on changes in mRNA transcript levels but instead relies

on translation regulation to achieve rapid stress adaptation.

Colorectal cancer

RRBP1 mRNA is higher in colorectal cancer (CRC)

tissues compared with normal tissues and RRBP1 protein is less

variable in normal tissues but more heterogeneous in cancerous

tissues (5). RRBP1 expression is

predictive of unfavorable survival outcomes; patients with high

RRBP1 expression have shorter disease-specific survival (5). The positive association between

chromosomal gains and RRBP1 mRNA levels (5) suggests the potential involvement of

RRBP1 in CRC progression as a driver gene. RRBP1 is also

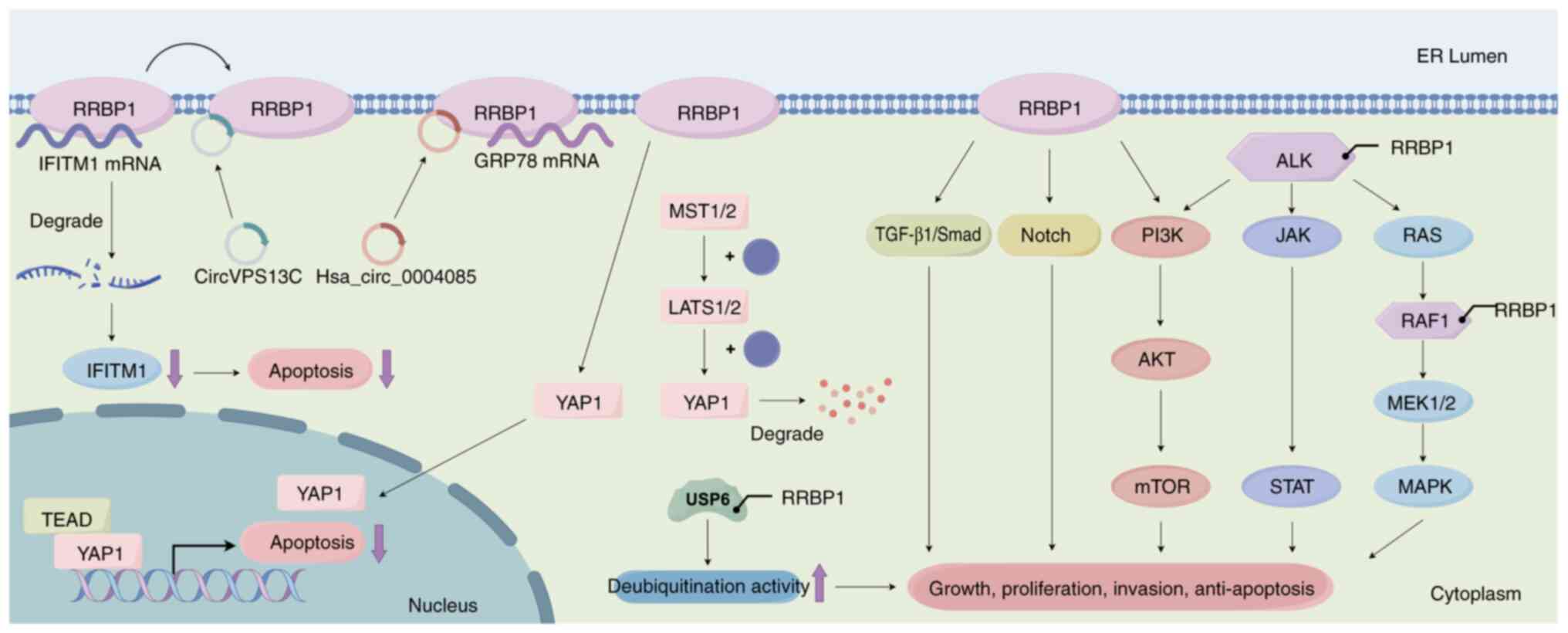

associated with chemoresistance in CRC. The circular RNA (circRNA)

hsa_circ_0004085 is a key molecule mediating chemoresistance in

Fusobacterium nucleatum-infected colon cancer cells

(46). Furthermore, RRBP1 is a

direct binding protein of hsa_circ_0004085 (46). Hsa_circ_0004085 inhibits

chemotherapeutic drug-induced ERS-associated apoptosis by enhancing

the stability of GRP78 mRNA by binding RRBP1 and upregulating the

expression level of GRP78, thus promoting chemoresistance in tumor

cells (Fig. 4) (46). Furthermore, hsa_circ_0004085

activates the UPR by promoting the translocation of the sheared

form of ATF6 (ATF6p50) to the nucleus, thereby enhancing the

adaptive survival of tumor cells (46).

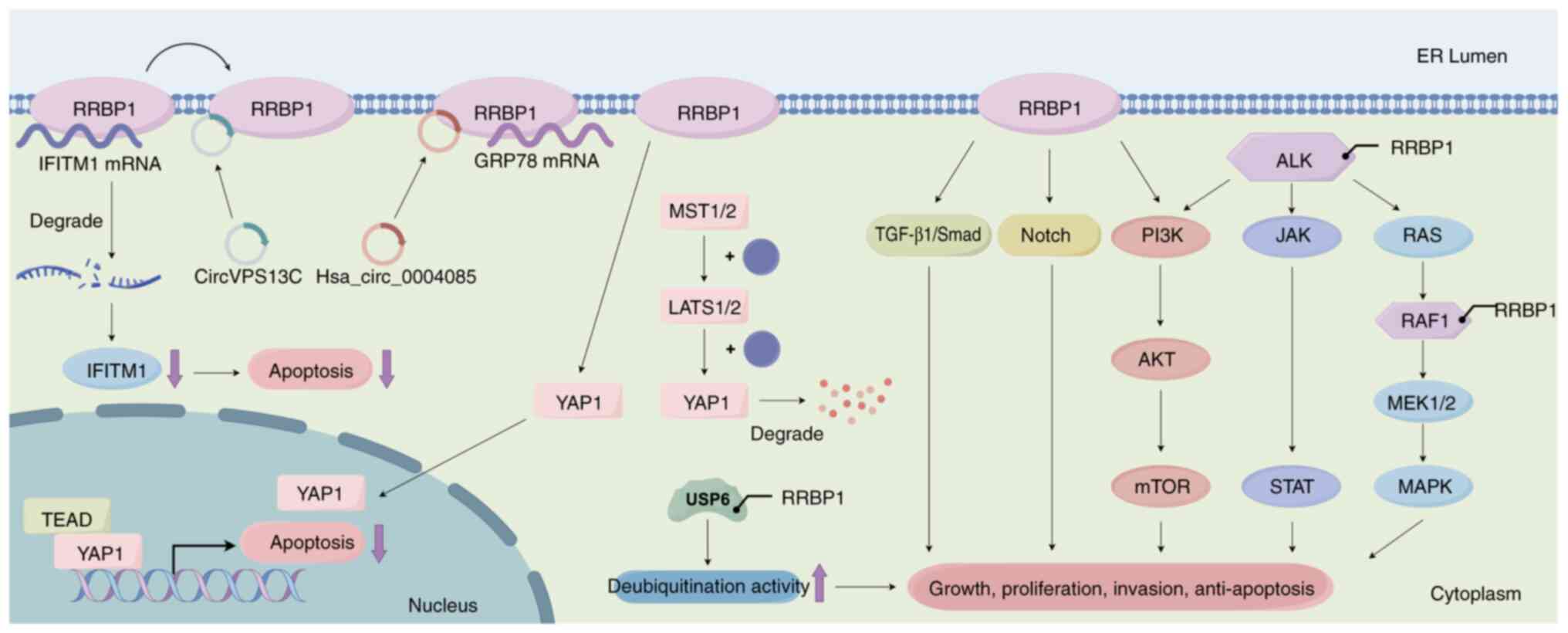

| Figure 4.RRBP1 promotes anti-apoptosis through

different signaling pathways, gene fusions and interactions with

circRNAs. RRBP1 activates various signaling pathways, thereby

promoting tumor cell proliferation and anti-apoptosis. It also

inactivates Hippo signaling and activates pro-survival and

anti-apoptotic genes. In addition, RRBP1 activates kinase

function through gene fusion (ALK, RAF1 and USP6),

promotes MAPK and other pathways and upregulates deubiquitination.

Furthermore, in the interaction between RRBP1 and circRNAs, binding

of RRBP1 to hsa_circ_0004085 stabilizes GRP78 and enhances cellular

adaptation to ERS. By contrast, circVPS13C inhibits the binding of

RRBP1 to IFITM1 mRNA by competitively binding RRBP1; subsequently,

degradation of IFITM1 mRNA leads to notable downregulation of its

protein expression level and further inhibits apoptosis. RRBP1,

ribosome-binding protein 1; YAP1, Yes-associated protein 1; ALK,

anaplastic lymphoma kinase; GRP78, glucose-regulated protein 78;

ERS, endoplasmic reticulum stress; IFITM1, interferon-induced

transmembrane protein 1; circRNA, circular RNA; hsa, Homo

sapiens; TEAD, transcription enhancement associated domain

family members; MST1/2, mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1/2;

LATS1/2, large tumor suppressor 1/2. |

RRBP1 is involved in tumor progression, has

utility as a prognostic marker, is a driver gene in CRC and its

expression level is also closely associated with chromosomal

abnormalities. Furthermore, it regulates chemoresistance-related

pathways through interaction with hsa_circ_0004085. Therefore, CRC

treatments should integrate the role of RRBP1 at the molecular and

cellular levels to overcome the associated resistance

mechanisms.

Bladder cancer and upper tract

urothelial carcinoma (UTUC)

The mRNA and protein expression levels of RRBP1 in

bladder cancer tissues are markedly higher compared with that in

normal bladder tissues (6). RRBP1

is highly expressed in advanced-stage, LNM and basal squamous

subtype bladder cancer and is closely associated with poor

prognosis in patients (6–8). In addition, Luo et al (8) have identified that the RRBP1

gene region exhibits aberrant DNA methylation in UTUC, according to

methylation profiling microarray analysis, and its mRNA and protein

expression levels are upregulated in both tumor tissues and a UTUC

cell line. Experimental overexpression of RRBP1 has been found to

promote the proliferation of bladder cancer cells, whereas

downregulation of RRBP1 inhibits cell proliferation (6). This proliferative effect is associated

with the TGF-β1/SMAD signaling pathway, which is activated by RRBP1

upregulation (Fig. 4) (6). Wang et al (7) have reported that knockdown of RRBP1

results in the downregulation of C-C chemokine receptor type 7 and

subsequent inhibition of the migration and invasive ability of

bladder cancer cells. In addition, knockdown of RRBP1 inhibits the

proliferation, migration and invasive ability of UTUC cells

(8). The high expression level of

RRBP1 drives the malignant progression of tumors through a

multidimensional regulatory network. Molecular subtyping analysis

has revealed that the high expression level of RRBP1 is positively

associated with genes related to cell proliferation; therefore, it

might promote cell cycle progression through activation of the

PI3K/AKT and Notch signaling pathways (Fig. 4). Furthermore, RRBP1 upregulates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) genes and basal cell

markers and suppresses luminal markers, thus contributing to the

acquisition of migratory and invasive properties of tumor cells and

a stem cell-like drug-resistant phenotype (8). The EMT is a reversible cellular

program in which epithelial cells lose their polarity and

intercellular adhesion through the downregulation of epithelial

markers such as E-cadherin and concurrently acquire mesenchymal

characteristics, including increased motility and the upregulation

of N-cadherin and vimentin (47).

This phenotypic shift facilitates tumor cell invasion through the

basement membrane and entry into the circulatory or lymphatic

systems, thus enabling metastatic dissemination. Notably, EMT is

closely associated with the acquisition of cancer stem cell-like

traits, including enhanced survival ability, resistance to

apoptosis and increased expression levels of drug efflux

transporters (47). These features

collectively contribute to resistance against chemotherapy and

immunotherapy. Furthermore, in a UTUC patient-derived organoid

model, high expression levels of RRBP1 have been associated with

chemoresistance to cisplatin, gemcitabine and epirubicin (8); therefore, it synergistically promotes

tumor cell survival by modulating ERS and yes-associated protein 1

(YAP1) signaling (Fig. 4) (8).

Overall, RRBP1 hypomethylation drives its

upregulation and subsequent participation in the malignant

progression of UTUC by promoting cell proliferation, the EMT

process and chemoresistance. Therefore, targeting RRBP1 or its

downstream effector pathways can reverse malignant tumor

phenotypes. In bladder cancer, RRBP1 serves a role in cell

proliferation through the TGF-β1/SMAD signaling pathway, whereas

cell migration and invasion involve the regulation of C-C chemokine

receptor type 7 and ERS, all of which may serve as potential

biomarkers for diagnosis and prognostic evaluation, thus providing

a precise therapeutic strategy for patients with high RRBP1

expression.

Prostate cancer

The mRNA and protein expression levels of RRBP1 are

higher in prostate cancer tissues compared with those in normal

cancer-adjacent tissues (9).

Patients with high (≥8) Gleason scores have higher RRBP1 expression

levels in tumor tissues compared with low Gleason scores (9). Furthermore, RRBP1 expression is

associated with the T stage of prostate cancer, LNM and

prostate-specific antigen level (9,48). The

median survival time is shorter in patients with prostate cancer

with higher compared with lower RRBP1 expression. Multifactorial

Cox regression analysis has indicated that RRBP1 is an independent

prognostic factor (9,48). Therefore, RRBP1 is closely

associated with tumor malignancy and progression and high RRBP1

expression can serve as a diagnostic marker and a predictor of poor

prognosis in prostate cancer. Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), an

RNA methyltransferase that forms a core methyltransferase complex

with METTL14, is responsible for adding N6-methyladenine

(m6A) modifications, which is the most common internal

modification in eukaryotic RNAs (49,50).

Rather than functioning through a single pathway, m6A

modifications influence multiple RNA processes by recruiting reader

proteins such as YT521-B homology m6A RNA binding

protein F2, which recognize m6A-marked transcripts and

promote their degradation (51).

For example, m6A and its reader proteins have been shown

to regulate multiple steps of RNA metabolism, including alternative

pre-mRNA splicing (via the nuclear reader YTHDC1) (52), mRNA stability and degradation (via

YTHDF2) (51), and translation

efficiency through enhanced ribosome loading (via YTHDF1) (53). These findings supported that

METTL3-mediated m6A modification is a dynamic

epitranscriptomic mechanism shaping mRNA fate and cellular

function. Notably, abnormal METTL3 expression and the resulting

imbalance in m6A regulation have been associated with

pathological conditions, including tumorigenesis (54). RRBP1 is a key downstream

target gene regulated by METTL3 in an m6A-dependent

manner. METTL3 upregulates the expression level of RRBP1 by binding

and methylating RRBP1 mRNA and enhancing its stability (Fig. 3) (49). Furthermore,

m6A-sequencing has revealed that RRBP1 mRNA demonstrates

stronger m6A enrichment in tumor tissues compared with

non-tumor tissues, thus further supporting the molecular mechanism

of its regulation by METTL3 (49).

In summary, RRBP1 is a core effector molecule of the

METTL3/m6A signaling axis in prostate cancer and its

m6A-dependent stabilization promotes tumor

aggressiveness and is closely associated with poor patient

prognosis. Peptide inhibitors targeting this regulatory axis have

potential therapeutic value in the future.

Epithelioid inflammatory

myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS)

EIMS is a rare inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

(IMT) subtype. IMT rarely recurs or metastasizes, whereas the

epithelioid variant of IMT, EIMS, which has distinctive

morphological features-for example, loosely arrayed round to

epithelioid tumor cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli,

eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm (55) and clinical aggressiveness, exhibits

poor prognosis (56,57). Chromosomal rearrangements are

frequently observed in IMT, including ALK rearrangement, a

genetic abnormality driving tumor cell proliferation in the form of

fusions of various chaperone genes such as TPM3-ALK, TPM4-ALK,

CLTC-ALK and EML4-ALK (56,58);

furthermore, the diversity of recombination patterns may be closely

associated with clinical heterogeneity (58). Notably, EIMS usually exhibits

nuclear membrane localization of Ran binding protein 2-ALK fusion

oncoproteins; in addition, novel RRBP1-ALK fusion proteins have

been identified in aggressive EIMS cases, showing cytoplasmic ALK

expression with perinuclear accentuation (Fig. 4) (56). The molecular structure and 3D

simulation structure of the RRBP1-ALK fusion protein are shown in

Fig. S1. The protein sequence of

RRBP1-ALK was obtained from the Ensembl database (https://www.ensembl.org/, release 114) and its domain

architecture was annotated using the Simple Modular Architecture

Research Tool (SMART; http://smart.embl.de/, accessed 12 August 2025). A

three-dimensional structural model was subsequently generated with

the AlphaFold server (https://alphafoldserver.com/, accessed 12 August

2025). Each ALK fusion partner retains a coiled-coil structural

domain in the ALK fusion protein, whereas RRBP1-ALK combines the

RRBP1 coiled-coil structural domain, the RRBP1 ER transmembrane

structural domain and the ribosome receptor structural domain

(56). The mechanism of the

formation of this fusion gene involves aberrant splicing of intron

20 of the RRBP1 gene; therefore, the RRBP1-ALK open

reading frame is composed of a 33-nucleotide sequence of

RRBP1 exon 20 fused to RRBP1 intron 20, which in turn

is fused to ALK exon 20 (56). This fusion pattern results in an ALK

protein with a cytoplasmic localization and an enhanced perinuclear

expression profile (56). EIMS

cases with RRBP1-ALK fusion exhibit a rapidly progressive

and aggressive disease course, with a median survival of only 2–10

months, which is markedly shorter compared with that of spindle

cell inflammatory myofibroblastoma with conventional ALK

fusion (56). Lee et al

(56) have suggested that

RRBP1-ALK is a novel recurrent oncogenic mechanism in

clinically aggressive EIMS. Although previous reports indicated

that the RRBP1-ALK fusion gene is seen only in EIMS,

subsequent reports have described the RRBP1-ALK fusion gene

in IMT (58,59). In a case report of recurrent IMT,

the 3′-end of exon 19 of the ALK gene was fused to the

5′-end of exon 10 of the RRBP1 gene (58). This case histologically revealed a

spindle cell type IMT, which differed from the morphological

features and clinical behavior of EIMS (58). Therefore, the RRBP1-ALK

fusion might have a heterogeneous pathogenic mechanism in different

IMT subtypes. A separate report presented a case with a

characteristic strong perinuclear ALK+ expression

pattern, in agreement with the expression profile of previously

reported cases of RRBP1-ALK fusion (56), and consisted of loosely organized

spindle cells on a mucus-like background (59). Furthermore, a recent study has

identified an RRBP1-USP6 fusion in low-grade myofibroblastic

sarcoma (Fig. 4) (60). This fusion arises from a T (17;20)

chromosomal translocation that juxtaposes exon 1 of the USP6

gene with exon 2 of the RRBP1 gene, thus marking the first

instance of RRBP1 being characterized as a fusion partner

for USP6 (60).

Structurally, this implies that the fusion transcript retains the

full coding sequence of USP6 together with its key

functional domains, including the ubiquitin-specific protease

catalytic core. RRBP1 functions as a regulatory module,

driving the abnormal expression of USP6. This finding has expanded

the genetic spectrum of USP6-associated neoplasms and is

potentially further links ER-ribosome pathway dysregulation and

malignant transformation in myofibroblastic tumors.

In conclusion, RRBP1 drives tumor malignancy

through fusion with ALK or USP6 genes and the

RRBP1-ALK fusion might enhance cancer cell survival and

invasiveness through ER localization, whereas the RRBP1-USP6

fusion aberrantly activates ubiquitination regulation, thus

suggesting an association between ER-ribosome pathway dysregulation

and tumor progression.

Pancreatic cancer

RRBP1 forms a fusion with the Raf1

gene (RRBP1-Raf1), which is markedly enriched in KRAS

wild-type tumors, according to the Arriba algorithm developed by

Uhrig et al (61). This

fusion retains the intact coding sequence of the Raf1 kinase

domain, whereas the transmembrane domain of RRBP1 anchors Raf1 to

the ER and drives its constitutive activation (61). Based on the structural features

described, it can be inferred that the breakpoint of the RRBP1-Raf1

fusion protein is located near the C-terminus of RRBP1, thereby

preserving its functional N-terminal domain and within the

N-terminal regulatory region of Raf1, maintaining the integrity of

its kinase domain. The structural preservation of the key domains

of both partners implies a breakpoint that occurs after the

functional segments of RRBP1 and before the key serine/threonine

kinase domain of Raf1, possibly resulting in a reading frame that

maintains the open reading frame and functional activity of the

fusion oncoprotein. Furthermore, functional studies demonstrated

that RRBP1-Raf1 expression in TP53-deficient MCF10A cells

and pancreatic ductal epithelial H6c7 cells markedly enhances

EGF-independent colony formation (61). After EGF withdrawal, the fusion

protein sustains MAPK pathway activation, as evidenced by markedly

elevated phosphorylation levels of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 (Fig. 4) (61). In brief, the preservation of the

Raf1 kinase domain in this fusion might confer differential

sensitivity to specific Raf inhibitors. This finding expands the

molecular mechanisms underlying MAPK pathway hyperactivation in

pancreatic cancer and provides a novel therapeutic direction for

KRAS wild-type pancreatic cancer.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

(OSCC)

RRBP1 is markedly upregulated in both early-stage

and late-stage cisplatin-resistant OSCC cell lines, as well as in

tumor tissues from chemotherapy-non-responsive patients vs. those

with chemotherapy-sensitive disease (62). Mechanistically, RRBP1 mediates

chemoresistance by regulating the Hippo signaling pathway effector

YAP1 (Fig. 4) (62). The Hippo signaling pathway, governed

by mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1/2 and large tumor suppressor

(LATS) 1/2 kinases, is implicated in cancer chemoresistance. After

activation, LATS1/2 phosphorylates key residues of YAP1 and

transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) [YAP1

serine (Ser) 127 and Ser397], thus leading to their cytoplasmic

retention and subsequent degradation via the β-transducin

repeat-containing protein-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome system

(62). By contrast, Hippo pathway

inactivation results in dephosphorylated YAP1/TAZ evading

degradation, translocating to the nucleus, binding transcription

enhancement-associated domain family members (TEADs) and activating

pro-survival and anti-apoptotic genes (62). Notably, RRBP1 expression is strongly

associated with YAP1 target genes and RRBP1 knockdown markedly

decreases YAP1 and its downstream targets at both the mRNA and

protein levels (62). Furthermore,

RRBP1 depletion restores cisplatin sensitivity and enhances

apoptosis, as evidenced by increased expression levels of cleaved

PARP (62). Therefore, these

findings established RRBP1 as a central driver of cisplatin

resistance in OSCC, through a mechanism involving Hippo pathway

dysregulation, and highlight RRBP1 targeting as a therapeutic

strategy to potentially overcome cisplatin-induced chemoresistance

in advanced OSCC in the future.

Pituitary adenoma

In non-functioning pituitary adenomas (NFPAs), the

function of RRBP1 is uniquely modulated by the circRNA circVPS13C

and demonstrates a distinct regulatory mechanism (63). CircVPS13C competitively binds RRBP1

and disrupts its interaction with interferon-induced transmembrane

protein 1 (IFITM1) mRNA, thereby decreasing IFITM1 mRNA stability

and suppressing its expression (Fig.

4) (63). IFITM1, which is

known to regulate cell proliferation and migration, exerts

tumor-suppressive effects in pituitary tumors; overexpression of

IFITM1 markedly inhibits the proliferation of pituitary

tumor-derived folliculostellate cells and induces apoptosis

(63). Zhang et al (63) have revealed that RRBP1 silencing

markedly decreases IFITM1 mRNA and protein levels, whereas

overexpression of RRBP1 partially rescues the inhibitory effects of

circVPS13C on IFITM1. In contrast to its pro-tumorigenic roles in

other cancer types, such as lung cancer, bladder cancer and EIMS,

RRBP1 exhibits tissue-specific regulation in NFPAs by sustaining

the tumor-suppressive function of IFITM1 (63). This finding underscores the

functional diversity of RRBP1 in tumor microenvironments and

highlights the key regulatory role of the circVPS13C-RRBP1-IFITM1

axis in NFPA progression.

Other cancer types

In female reproductive system cancer types, RRBP1

exhibits marked upregulation with distinct clinicopathological

associations. For instance, in endometrial carcinoma, elevated

RRBP1 levels are strongly associated with advanced International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages, poor

differentiation, deep myometrial invasion and LNM (37). Similarly, cervical squamous cell

carcinoma and epithelial ovarian cancer demonstrate markedly higher

RRBP1 expression in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues and

this elevated expression is associated with aggressive features

such as advanced FIGO staging, lymph node involvement and

unfavorable histotypes (35,64).

Notably, multivariate Cox analyses across these malignancies have

consistently identified RRBP1 as an independent prognostic factor

whose high expression predicts shortened OS and disease-free

survival (35,37,64).

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), RRBP1 has been

reported as a potential leukemogenesis-associated molecule

regulated by exosomes derived from bone marrow microenvironmental

mesenchymal stromal cells (65).

Barrera-Ramirez et al (65)

have identified that mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes in

patients with AML demonstrate diminished levels of microRNA

(miR)-339-3p, a direct RRBP1 suppressor, thereby derepressing RRBP1

transcription. This finding not only expands the oncogenic

repertoire of RRBP1 beyond solid tumors, but also suggests a novel

association between exosomal miRNA signaling and leukemic cell

regulation. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have directly

reported RRBP1 alterations or functional involvement in leukemias

other than AML or in lymphomas, to date. Thus, its role in these

hematological malignancies remains elusive and unreported,

warranting further investigation.

In esophageal cancer, RRBP1 is highly expressed at

both the mRNA and protein levels (10). Clinicopathological analysis has

demonstrated that high RRBP1 expression is markedly and positively

associated with the depth of tumor infiltration, LNM and advanced

TNM stage (10). Patients with high

RRBP1 expression exhibit a median survival of 43 months, in

contrast to the 56 months observed in low-expression cohorts,

thereby further validating its prognostic utility (10).

In bone metastasis, RRBP1 secreted by cancer cells

exerts a paradoxical role in modulating osteoblast differentiation

(66). Chen et al (66) have identified that RRBP1 is the only

highly abundant shared protein associated with osteoblast

differentiation in conditioned media of breast and prostate cancer

cells. Knockdown of RRBP1 in cancer cells enhances osteoblast

differentiation markers (ALP and bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein),

matrix mineralization and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)

2/SMAD1/5/9 activation in pre-osteoblasts (66). These findings indicated that bone

metastatic cancer cells inhibit osteoblastic differentiation by

secreting RRBP1 and the mechanism may involve the regulation of ERS

levels and interference with the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway. These

findings provide a potential theoretical basis for targeting RRBP1

in the treatment of bone metastasis-associated bone lesions in the

future.

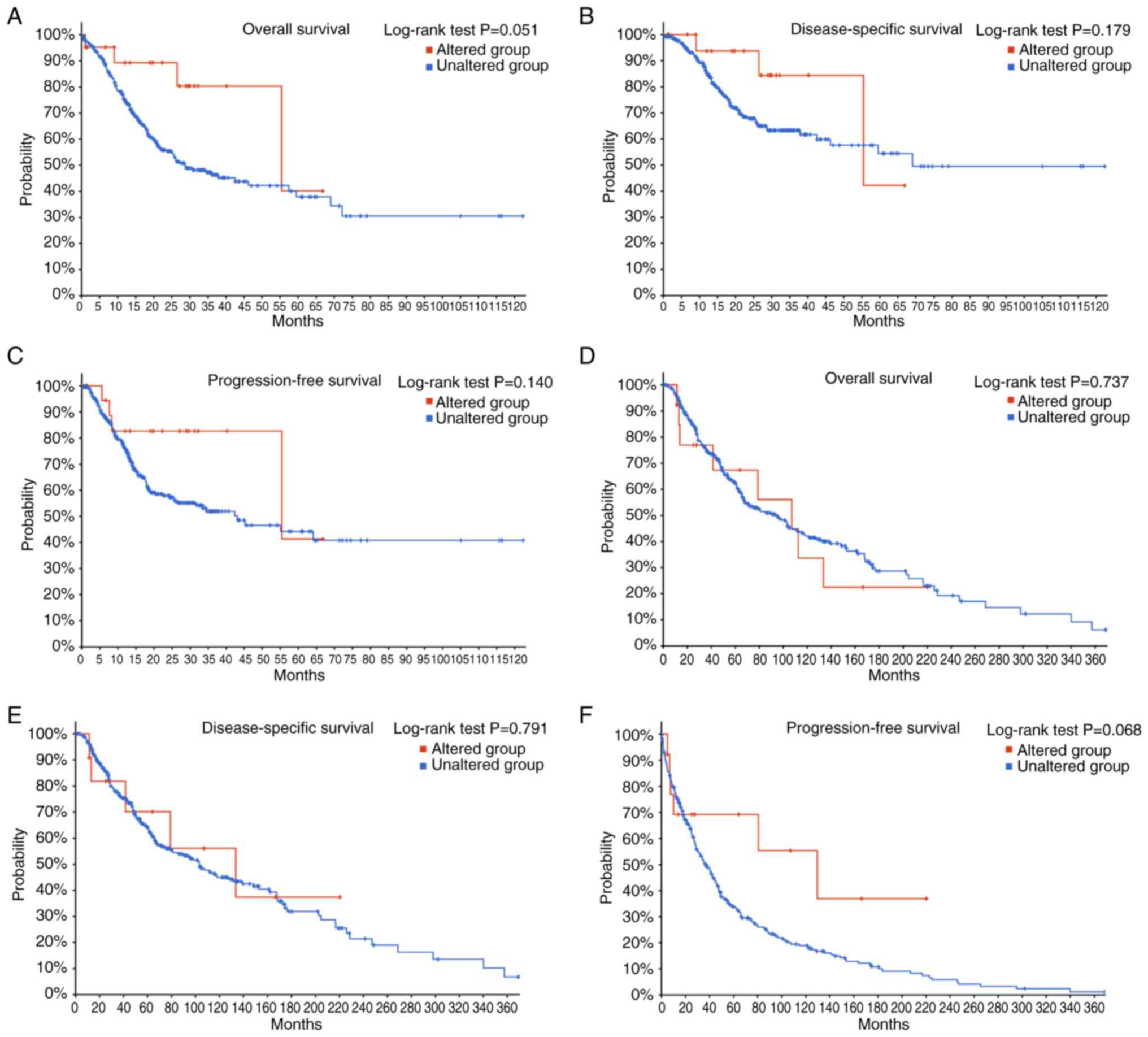

Beyond the aforementioned cancer types, several

tumor types have high RRBP1 alteration frequencies but lack

published evidence, to the best of our knowledge. Examples include

stomach adenocarcinoma and skin cutaneous melanoma (Fig. 2). The present review used the

cBioPortal database (TCGA; PanCancer Atlas; http://www.cbioportal.org/) to perform Kaplan-Meier

survival analyses for these cancer types and compared the survival

outcomes between patients with vs. without RRBP1 mutation

(Fig. 5). For stomach

adenocarcinoma, the RRBP1-altered group, as compared with

the unaltered group, demonstrated a trend toward improved OS,

disease-specific survival and progression-free survival (Fig. 5A-C). Similarly, in skin cutaneous

melanoma, patients with RRBP1 alterations also showed a

trend toward improved OS, disease-specific survival and

progression-free survival (Fig.

5D-F). Although these comparisons did not reach statistical

significance (log-rank P>0.05), the consistent direction of the

curves suggested potential biological relevance. One possible

explanation is that certain mutations in RRBP1 may impair

its function in protein transport and, therefore, slow tumor

progression or they may occur in molecular subtypes that are

intrinsically associated with a more favorable prognosis. However,

due to the limited number of mutated cases and potential

confounding clinical variables, these observations should be

interpreted with caution and require further exploration in studies

with larger sample sizes or functional studies.

Therapeutic targeting of RRBP1 in

cancer

The multifaceted roles of RRBP1 in tumorigenesis

and progression underscore its key position as a metastable hub at

organelle-membrane interfaces. RRBP1 serves complex and key roles

in multiple important molecular mechanisms in various types of

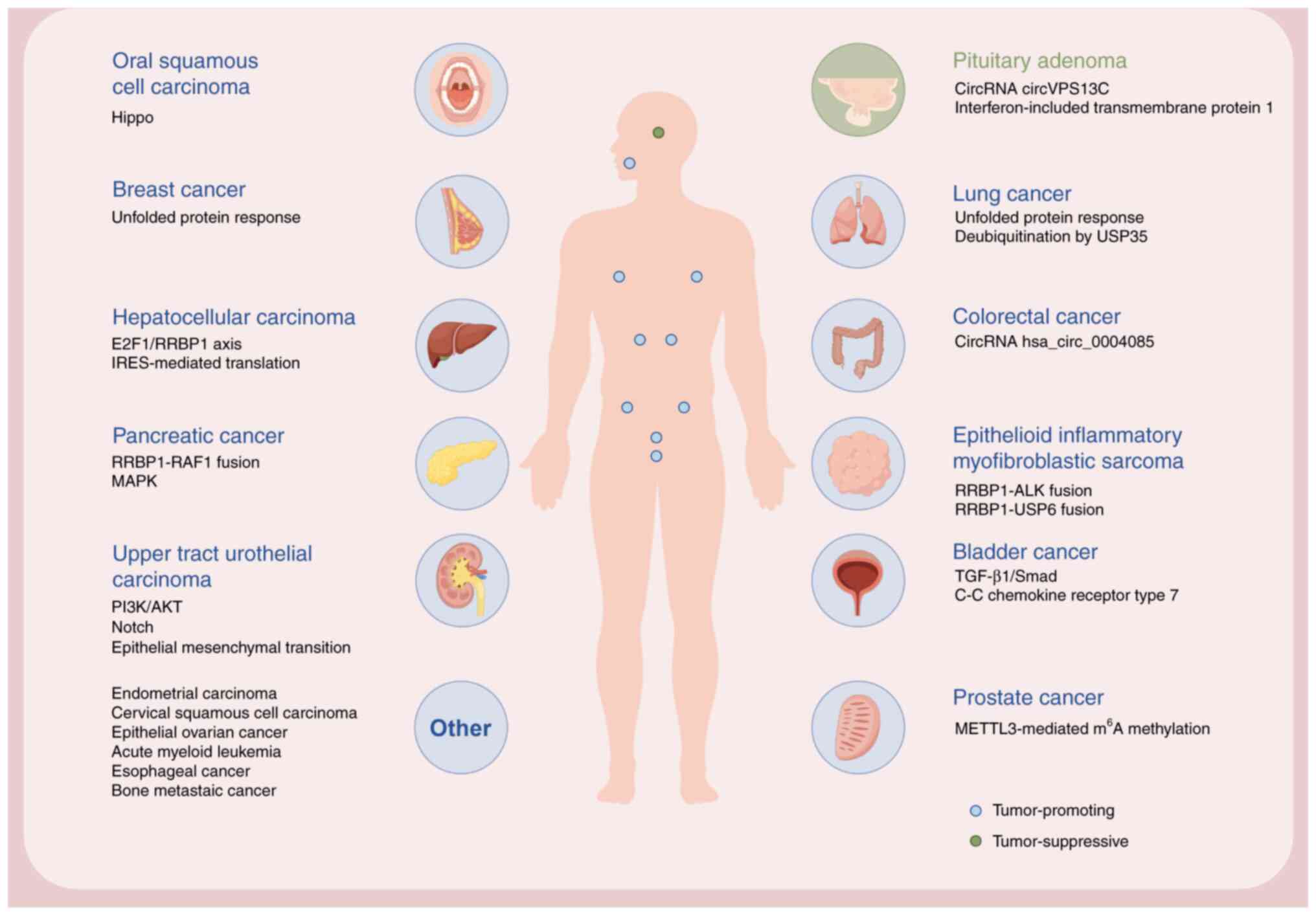

cancer (Fig. 6). Although its

upregulation is closely associated with tumor progression,

metastasis and chemotherapy resistance, its mechanistic basis

reveals environment-dependent regulatory mechanisms; therefore,

RRBP1 is a highly promising therapeutic target across cancer

types.

| Figure 6.RRBP1 expression in various human

organs and associated cancer types. Schematic diagram demonstrating

RRBP1-associated cancer types and representative molecular

mechanisms or keywords. Blue circles indicate tumor-promoting

roles, whereas green circles indicate tumor-suppressive roles.

‘Others’ include cancer types without specific organ illustration

(created in FigDraw). RRBP1, ribosome-binding protein 1, circRNA,

circular RNA; E2F1, E2F transcription factor 1; IRES, internal

ribosome entry site; USP35, ubiquitin-specific processing protease

35; m6A, N6-methyladenine; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma

kinase; METTL3, methyltransferase-like 3. |

Targeting RRBP1-mediated stress

adaptation

Stabilization of GRP78 inhibits ERS-associated

apoptosis and decreases ROS accumulation, thus markedly enhancing

cancer cell survival and chemoresistance (Fig. 3). In lung cancer, breast cancer and

CRCs, RRBP1 stabilizes GRP78 mRNA, thereby enhancing UPR-mediated

survival under ERS (4,36,46).

Small molecules targeting the GRP78-PERK-eIF2α axis, such as PERK

inhibitors (67), directly block

the signaling pathway but have the drawback of pancreatic toxicity.

Alternatively, by using a monoclonal antibody blocking RRBP1/GRP78

interaction, the regulation of UPR by RRBP1 can be decreased, thus

reversing chemoresistance.

Epigenetic modulation strategies

Enhancing self-stability through epigenetic

modification or inhibition of degradation pathways such as the

METTL3/m6A axis and USP35 deubiquitination promotes

adaptive stress signals (Fig. 3).

In lung cancer, the USP35 deubiquitination modification inhibits

the proteasome-mediated degradation pathway (41), whereas in prostate cancer, METTL3

stabilizes RRBP1 through m6A modification (49). Therefore, inhibition of the

METTL3/m6A axis, such as with small molecule peptides

(68), decreases the stability of

RRBP1 and blocks tumor progression. In addition, METTL3 inhibits

programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression through

m6A modification and weakens the antitumor immune

response (69). Inhibition of

METTL3 remodels the tumor microenvironment and enhances the

efficacy of programmed cell death protein-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy.

Furthermore, small molecule inhibitors or gene editing systems

targeting USP35 can also decrease RRBP1 protein stability (70). However, functional synergy among USP

family members poses an important technical hurdle. Specific USP

isoforms, such as USP7, USP14 and USP22, can promote therapeutic

resistance by enhancing pro-survival protein stability, while other

members may participate in distinct regulatory processes (70). This functional heterogeneity not

only leads to a lack of specificity for targeted interventions but

may also trigger unintended off-target effects. Therefore, in-depth

analysis of the molecular basis of specific USP subtypes mediating

drug resistance phenotypes will provide a key theoretical basis for

the achievement of precision interventions in the future.

Pathway inhibition approaches

Activation of the TGF-β/SMAD, PI3K/AKT, Notch and

MAPK pathways, and inhibition of the Hippo pathway, drives tumor

proliferation and anti-apoptotic ability (Fig. 4) (6,8,61,62).

To address the multifaceted nature of the tumor, a layered

targeting strategy can be designed. First, small molecule

inhibitors or antibody drugs can be developed to specifically

target RRBP1 and eliminate its inhibition of the Hippo pathway and

synergistic activation effect of multiple pathways. Second, key

downstream nodes can be targeted, e.g., with YAP/TAZ-TEAD complex

blockers (71), dual PI3K/mTOR

inhibitors (72), Ras/Raf/MAPK

inhibitors (73) or neutralizing

antibodies to decrease ligand-receptor binding (74,75).

Third, epigenetic regulation can be integrated by co-delivery of

RRBP1 small interfering RNA with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors

via nanocarriers, thus reversing pro-oncogenic regulation. Notably,

because the RRBP1 pathways of activation and inhibition differ

among cancer types, precise guidance of treatment and localization

of its subcellular mode of action are necessary, in conjunction

with spatial transcriptomics technology to potentially achieve

precise spatiotemporal targeting in the future.

Fusion gene-targeted therapy

At the gene level, RRBP1 is abnormally

activated by gene fusions (ALK, Raf1 and USP6) and

subsequently regulates kinase function or deubiquitination;

therefore, RRBP1 is a potential therapeutic target (Fig. 4) (56,60,61).

For RRBP1-ALK/Raf1 fusion proteins arising in EIMS and pancreatic

cancer, selective kinase inhibitors can impair aberrant kinase

activity but must be optimized to overcome RRBP1-mediated drug

resistance (73,76). For RRBP1-USP6 fusions with abnormal

ubiquitination regulation, proteasome inhibitors or

deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors can be explored (70). In addition, the rapid development of

gene editing technology in recent years is expected to overcome

existing therapeutic bottlenecks and provide more effective

treatment options through precise gene modification or modulation

strategies (77–81). Notably, one EIMS case report stated

that the RRBP1-ALK fusion+ case has notable

histological features, predominantly collagenous mesenchyme with

only localized areas of a mucus-like matrix (57). In contrast to the poor prognoses of

previous RRBP1-ALK fusion cases, which resulted in rapid

recurrence or death (56), this

case demonstrated a favorable prognosis with no recurrence or

metastasis during as many as 50 months of follow-up after

crizotinib-targeted therapy (57).

This prognostic difference may be closely associated with the

characteristics of the collagen fiber-dominated microenvironment in

the tumor stroma and the standardized use of ALK inhibitors after

surgery. Therefore, the development of therapeutic strategies

should be based on a combination of molecular features and tissue

microenvironmental characteristics. In addition, the type of

ALK fusion may be associated with the primary site of the

tumor. RRBP1-ALK fusions are observed predominantly in

abdominal EIMS, whereas rare fusion types such as echinoderm

microtubule-associated protein-like 4-ALK and

vinculin-ALK have been reported in central nervous system

cases (82). This molecular

heterogeneity highlights the need for molecular testing in the

diagnosis and classification of EIMS, particularly for the

differential diagnosis of cases involving rare sites. In summary,

gene fusions reveal molecular heterogeneity and clinical diversity

in different tumor types and the differences in pathogenic

mechanisms, histological features and therapeutic responses

highlight the key roles of precision medicine in diagnostic and

therapeutic decision-making. Future studies should further clarify

the interaction between the molecular characteristics of fusion

genes and the tumor microenvironment and establish improved

genotype-phenotype correlation models to potentially achieve truly

personalized treatment.

RNA-interaction disruption

RRBP1-RNA interactions have further revealed the

complex roles of RRBP1 in the regulation of tumor adaptation

(Fig. 4). In CRC, hsa_circ_0004085

binds RRBP1, stabilizes GRP78, enhances tumor cell adaptation to

ERS and promotes drug resistance, thereby inhibiting apoptosis

(46). For such RNA-interaction

networks, the development of targeted antisense oligonucleotides

(83), combined with specific

sequence design, chemical modification optimization, efficient

delivery systems and combined therapeutic strategies, can

potentially overcome the stability challenges posed by the cyclic

RNA structure, disrupt its binding to RRBP1 and restore apoptosis

susceptibility. However, in NFPA, overexpression of RRBP1 partially

reverses the inhibitory effect of circVPS13C on IFITM1, thereby

inducing apoptosis (63). This

duality challenges the traditional dichotomy of oncogenes and tumor

suppressor genes, highlights the high context dependence of RRBP1

function and emphasizes the need to design layered intervention

strategies based on microenvironmental characteristics.

The dual role of RRBP1 as a stress adaptor and

fusion partner presents both opportunities and challenges.

Targeting RRBP1-interacting pathways might enable precision therapy

by relying on the vulnerability of the upper and lower pathways.

However, both the tissue specificity of the RRBP1-ALK fusion and

the tumor suppressor function of IFITM1 by maintaining it in NFPA

caution against a one-size-fits-all solution (56–59,63).

Future research can prioritize functional stratification of the

RRBP1 network by using spatial multi-omics to determine how

organelle communication is rewired in specific tumor subtypes.

Despite the identification of RRBP1 as a promising

therapeutic candidate, to the best of our knowledge, no

interventional clinical trials directly targeting RRBP1 have been

registered in major trial repositories (ClinicalTrials.gov and World Health Organization

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) to date. Current

therapeutic concepts remain largely preclinical and indirect,

focusing instead on upstream or downstream regulatory nodes such as

GRP78, METTL3, USP35 or oncogenic fusion partners (ALK, Raf1 and

USP6) (67–70,73,76).

These strategies underscore the translational potential of RRBP1

but also highlight that its development as a direct druggable

target is still at an early investigational stage.

RRBP1 cancer-independent activities

Beyond oncology, the multifaceted roles of RRBP1 in

diverse physiological and pathological settings highlight its key

function as a structural and metabolic coordinator. In the

musculoskeletal system, RRBP1 exhibits a regulatory role by driving

collagen biosynthesis and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in

fibroblasts through miR-206-mediated post-transcriptional

regulation (84). Furthermore, its

dynamic expression during periodontal ligament stem cell

osteogenesis underscores its potential to promote osteogenesis

(85), possibly by promoting

ER-dependent ECM secretion. Paradoxically, the observation that

knockdown of RRBP1 in osteoblasts attenuates ALP and runt-related

transcription factor 2 expression in an osteoporosis model suggests

that bone formation is influenced by the environment (86). These findings have revealed that

RRBP1 is a multi-effect regulator spanning the environment of ECM

dynamics, osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. Therefore,

RRBP1 function can be considered an environmentally responsive

regulatory hub whose mode of action exhibits a dynamic balance

between physiological tissue remodeling and pathological bone

homeostatic imbalance.

Previous studies examining the relationship between

RRBP1 and hepatic lipid metabolism have focused on the functional

effects of RRBP1 expression regulation on ER-mitochondrial complex

formation and lipid metabolic output (21,32–34).

Although these functional gains or losses provide direct

mechanistic insights into the regulatory ability of RRBP1, they may

not fully reproduce the pathophysiological sequence observed in

vivo, whereby systemic metabolic alterations precede disruption

of lipid homeostasis. Notably, emerging investigations have begun

to bridge this knowledge gap by interrogating RRBP1 dynamics under

physiologically relevant metabolic states. For instance, a seminal

study has systematically characterized fasting-induced RRBP1

expression and subcellular localization patterns in both lean and

obese mouse models (87). Under

fasting, RRBP1 is specifically upregulated around the hepatic

portal vein and in the middle of the lobule and it drives specific

remodeling of rough surface ER-coated mitochondria, thereby

maintaining mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation function (87). By contrast, RRBP1 deficiency

inhibits fasting-induced ER-mitochondrial interactions and leads to

mitochondrial rounding, impaired β-oxidation and lipid accumulation

(87). These results have revealed

the molecular basis of RRBP1 in mediating metabolic adaptation

through dynamic regulation of ER-mitochondrial spatial

architecture. These findings have also clarified the role of RRBP1

as a key structural regulator that dynamically translates

physiological stimuli or pathological injury into structural and

functional remodeling of organelle networks. Future studies should

prioritize the elucidation of the upstream signaling pathways

regulating RRBP1 post-translational modifications and their

spatiotemporal coordination with other membrane contact site

regulators during metabolic adaptation.

Conclusions and perspectives

In cancer, RRBP1 drives malignancy by modulating

molecular signaling pathways and associated organelles, such as by

stabilizing the GRP78-PERK-eIF2α axis and inhibiting apoptosis,

activating pro-survival pathways (TGF-β/SMAD and PI3K/AKT) and

binding cyclic RNAs. In aggressive tumors, such as pancreatic

cancer and EIMS, this protein oncogenic role is further amplified

by fusion events (RRBP1-ALK and RRBP1-Raf1). Beyond

cancer, RRBP1 serves key central roles in several physiological and

pathological processes, such as the regulation of metabolic

homeostasis, regulation of neuronal function, homeostasis of the

cardiovascular system and remodeling of bone metabolism by

regulating the interactions between cellular organelles.

However, clinical translation faces challenges of

expression heterogeneity among cancer subtypes and the limitations

of current models, which are unable to reproduce systemic effects

due to a lack of cross-disease comparisons, since several previous

studies have relied on in vitro systemic or single-tissue

analyses (6,42,61,62).

To bridge these gaps, future research efforts should prioritize

multi-omics integration to decode the tissue-specific regulatory

networks and immune microenvironmental interactions of RRBP1.

Combining mechanistic understanding with advanced in vivo

models (humanized organoids or multi-tissue CRISPR screens) could

accelerate the development of organelle-targeted therapies and

pan-disease biomarkers, thereby potentially transforming precision

medicine from subcellular dynamics to clinical outcomes. Although

the cancer-promoting mechanism of RRBP1 has been gradually

revealed, its dynamic interaction network and targeted intervention

strategies can be further explored in depth, particularly to

overcome therapeutic resistance and microenvironmental remodeling.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for translational research in

this area.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82104603) and the Beijing Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. 7204322).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HH provided project administration, devised the

methodology, prepared Fig. 1,

Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 and Fig. S1 and drafted the manuscript. JO

conceived and designed the present review, acquired funding,

provided supervision, validated the data and reviewed the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of Cancer: New

Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liang X, Sun S, Zhang X, Wu H, Tao W, Liu

T, Wei W, Geng J and Pang D: Expression of ribosome-binding protein

1 correlates with shorter survival in Her-2 positive breast cancer.

Cancer Sci. 106:740–746. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pan Y, Cao F, Guo A, Chang W, Chen X, Ma

W, Gao X, Guo S, Fu C and Zhu J: Endoplasmic reticulum

ribosome-binding protein 1, RRBP1, promotes progression of

colorectal cancer and predicts an unfavourable prognosis. Br J

Cancer. 113:763–772. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lv SW, Shi ZG, Wang XH, Zheng PY, Li HB,

Han QJ and Li ZJ: Ribosome binding Protein 1 correlates with

prognosis and cell proliferation in bladder cancer. Onco Targets

Ther. 13:6699–6707. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang M, Liu S, Zhou B, Wang J, Ping H and

Xing N: RRBP1 is highly expressed in bladder cancer and is

associated with migration and invasion. Oncol Lett.

20:2032020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Luo HL, Liu HY, Chang YL, Sung MT, Chen

PY, Su YL, Huang CC and Peng JM: Hypomethylated RRBP1 potentiates

tumor malignancy and chemoresistance in upper tract urothelial

carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 22:87612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li T, Wang Q, Hong X, Li H, Yang K, Li J

and Lei B: RRBP1 is highly expressed in prostate cancer and

correlates with prognosis. Cancer Manag Res. 11:3021–3027. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang L, Wang M, Zhang M, Li X, Zhu Z and

Wang H: Expression and significance of RRBP1 in esophageal

carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 10:1243–1249. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Savitz AJ and Meyer DI: 180-kD ribosome

receptor is essential for both ribosome binding and protein

translocation. J Cell Biol. 120:853–863. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wanker EE, Sun Y, Savitz AJ and Meyer DI:

Functional characterization of the 180-kD ribosome receptor in

vivo. J Cell Biol. 130:29–39. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Telikicherla D, Marimuthu A, Kashyap MK,

Ramachandra YL, Mohan S, Roa JC, Maharudraiah J and Pandey A:

Overexpression of ribosome binding protein 1 (RRBP1) in breast

cancer. Clin Proteomics. 9:72012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hung V, Lam SS, Udeshi ND, Svinkina T,

Guzman G, Mootha VK, Carr SA and Ting AY: Proteomic mapping of

cytosol-facing outer mitochondrial and ER membranes in living human

cells by proximity biotinylation. Elife. 6:e244632017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bhadra P, Schorr S, Lerner M, Nguyen D,

Dudek J, Förster F, Helms V, Lang S and Zimmermann R: Quantitative

proteomics and differential protein abundance analysis after

depletion of putative mRNA receptors in the ER membrane of human

cells identifies novel aspects of mRNA targeting to the ER.

Molecules. 26:35912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cui XA, Zhang H and Palazzo AF: p180

promotes the ribosome-independent localization of a subset of mRNA

to the endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 10:e10013362012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ueno T, Kaneko K, Sata T, Hattori S and

Ogawa-Goto K: Regulation of polysome assembly on the endoplasmic

reticulum by a coiled-coil protein, p180. Nucleic Acids Res.

40:3006–3017. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cui XA, Zhang H, Ilan L, Liu AX, Kharchuk

I and Palazzo AF: mRNA encoding Sec61β, a tail-anchored protein, is

localized on the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 128:3398–3410.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Diefenbach RJ, Diefenbach E, Douglas MW

and Cunningham AL: The ribosome receptor, p180, interacts with

kinesin heavy chain, KIF5B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

319:987–992. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cardoso CM, Groth-Pedersen L, Høyer-Hansen

M, Kirkegaard T, Corcelle E, Andersen JS, Jäättelä M and Nylandsted

J: Depletion of kinesin 5B affects lysosomal distribution and

stability and induces Peri-nuclear accumulation of autophagosomes

in cancer cells. PLoS One. 4:e44242009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cardoen B, Vandevoorde KR, Gao G,

Ortiz-Silva M, Alan P, Liu W, Tiliakou E, Vogl AW, Hamarneh G and

Nabi IR: Membrane contact site detection (MCS-DETECT) reveals dual

control of rough mitochondria-ER contacts. J Cell Biol.

223:e2022061092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ilamathi HS, Benhammouda S, Lounas A,

Al-Naemi K, Desrochers-Goyette J, Lines MA, Richard FJ, Vogel J and

Germain M: Contact sites between endoplasmic reticulum sheets and

mitochondria regulate mitochondrial DNA replication and

segregation. iScience. 26:1071802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Killackey SA, Bi Y, Soares F, Hammi I,

Winsor NJ, Abdul-Sater AA, Philpott DJ, Arnoult D and Girardin SE:

Mitochondrial protein import stress regulates the LC3 lipidation

step of mitophagy through NLRX1 and RRBP1. Mol Cell.

82:2815–2831.e5. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Killackey SA, Bi Y, Philpott DJ, Arnoult D

and Girardin SE: Mitochondria-ER cooperation: NLRX1 detects

mitochondrial protein import stress and promotes mitophagy through

the ER protein RRBP1. Autophagy. 19:1601–1603. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ge P, Dawson VL and Dawson TM: PINK1 and

Parkin mitochondrial quality control: A source of regional

vulnerability in Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 15:202020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu J, Liu W, Li R and Yang H: Mitophagy

in Parkinson's disease: From pathogenesis to treatment. Cells.

8:7122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rüb C, Wilkening A and Voos W:

Mitochondrial quality control by the Pink1/Parkin system. Cell

Tissue Res. 367:111–123. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sierksma A, Lu A, Mancuso R, Fattorelli N,

Thrupp N, Salta E, Zoco J, Blum D, Buée L, De Strooper B and Fiers

M: Novel Alzheimer risk genes determine the microglia response to

amyloid-β but not to TAU pathology. EMBO Mol Med. 12:e106062020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Koppers M, Özkan N, Nguyen HH, Jurriens D,

McCaughey J, Nguyen DTM, Li CH, Stucchi R, Altelaar M, MacGillavry

HD, et al: Axonal endoplasmic reticulum tubules control local

translation via P180/RRBP1-mediated ribosome interactions. Dev

Cell. 59:2053–2068.e9. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nazarian J, Bouri K and Hoffman EP:

Intracellular expression profiling by laser capture

microdissection: Three novel components of the neuromuscular

junction. Physiol Genomics. 21:70–80. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ramdas S, Judd J, Graham SE, Kanoni S,

Wang Y, Surakka I, Wenz B, Clarke SL, Chesi A, Wells A, et al: A

multi-layer functional genomic analysis to understand noncoding

genetic variation in lipids. Am J Hum Genet. 109:1366–1387. 2022.