Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer

globally and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths

(1). According to the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the digestive system

(2), rectal cancer (RC) can be

histologically graded as well differentiated, moderately

differentiated, poorly differentiated and undifferentiated.

Different histopathological grades markedly influence treatment

strategies and prognosis (3). For

patients with early local tumor-stage RC and no lymph node or

distant metastasis (cT1N0M0), survival rates are relatively high

following endoscopic resection, local excision or segmental

resection, with chemotherapy not typically required postoperatively

(4). However, if post-endoscopic

resection pathology reveals high-risk recurrence factors, such as

moderate-to-poor differentiation, vascular invasion or positive

resection margins, clinical guidelines recommend additional

segmental resection and regional lymph node dissection (5). For rectal adenocarcinoma with moderate

differentiation and late-stage local tumor (T)-stage such as T4a

and T4b, local excision is prone to residual cancer, and

neoadjuvant therapy followed by radical total mesorectal excision

surgery is recommended (6). Poorly

differentiated or undifferentiated carcinomas indicate more

aggressive tumor biology, with a higher likelihood of early

metastasis and worse prognosis (7).

These cases often necessitate more aggressive treatment approaches

which may include additional surgical resection of the primary

lesion and regional lymphadenectomy. Postoperative adjuvant

radiotherapy or chemotherapy is often required to improve overall

therapeutic efficacy. Notable, the outcomes of salvage surgery for

patients with recurrence after local excision are limited. The

3-year overall survival rate is only ~31, and ~39% of patients

develop distant metastases (8).

However, Hahnloser et al (9)

reported that, when extended resection was performed within 30 days

of local excision, the 5-year survival rate was comparable with

that of patients who initially underwent radical resection.

Therefore, if the initial pathology following local excision

indicates poor differentiation, interval radical resection should

be considered. Nevertheless, this approach may compromise sphincter

preservation, leading certain patients to opt for adjuvant

chemoradiotherapy instead (10). In

summary, accurate preoperative prediction of the histological

differentiation of RC is of paramount importance, as it directly

influences surgical recommendations and patient decision-making

prior to the initial intervention.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential for

the non-invasive characterization of RC, providing superior soft

tissue resolution and offering more accurate insights into the

heterogeneity of the tumor compared with other imaging modalities

(11). However, pathological

differentiation is still primarily dependent on postoperative

pathological biopsy (12), and

there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that conventional

imaging techniques can reliably differentiate pathological grading

of RC. Consequently, there is a pressing need for more intelligent

and sensitive diagnostic technologies to enable preoperative

assessment of RC differentiation. Radiomics, which extracts

numerous quantitative features from medical images, has shown

notable potential in evaluating RC characteristics (13). Existing studies have indicated that

radiomic features based on MRI of the primary tumor can predict the

pathological differentiation of other tumors. However, most of

these studies have focused primarily on the intratumoral features

(14,15), neglecting potentially valuable

information in the peritumoral region and requiring more clinical

interpretability which hinders the widespread application of

imaging models.

The peritumoral region includes endothelial cells,

fibroblasts, immune cells, other cell types and extracellular

components, forming the tumor microenvironment (16). The tumor microenvironment serves a

decisive role in tumor progression, treatment response and

metastasis. Therefore, radiomic features of the peritumoral

environment may provide crucial data for clinically assessing the

aggressive biological behavior of tumors. Whilst Liu et al

(17) reported that peritumoral

tissues in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are associated with

pathological differentiation, systematic exploration of the

relationship between peritumoral tissues and pathological

differentiation in patients with RC is lacking, and the value of

peritumoral features in predicting RC pathological differentiation

remains controversial.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

construct a predictive model based on intratumoral and peritumoral

(within 5 mm of the tumor) radiomics features derived from

multiparametric MRI to achieve preoperative noninvasive

differentiation between well differentiated RC (adenomatous

structure ≥95%) and non-well differentiated RC. Furthermore, a

preoperative radiomics model that integrates the optimal features

from both intratumoral and 5-mm peritumoral regions was developed

and validated, with the goal of providing an imaging-based

reference for accurate preoperative assessment and clinical

decision-making in RC.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated

Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (Nanchong, China)

approved the current retrospective study (approval no. 2024ER490-1)

and waived the requirement for informed consent from patients. The

data of 224 patients with RC who underwent surgery between January

2017 and February 2024 at the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan

Medical College were retrospectively analyzed. All patients

underwent preoperative MRI scanning, and the diagnosis of

adenocarcinoma was confirmed by pathological examination after

surgery.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Primary

RC; ii) pathologically-confirmed adenocarcinoma; iii) postoperative

pathological findings with clear pathological differentiation; iv)

lesions which could be identified on MRI images and could be

successfully enlarged peritumorally; v) no radiotherapy prior to

surgery; and vi) radical, endoscopic resection or palliative

resection. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Lack of

description or formal report regarding the degree of tumor

differentiation (n=13); ii) incomplete MRI sequences or poor image

quality (n=31); iii) previous history of other tumors in

combination (n=6); and iv) pathological diagnosis of squamous,

carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors (n=27). After appropriate

screening, a total of 224 patients were included in the present

study, who were randomized into training or validation groups in a

ratio of 7:3.

Pathological differentiation

analysis

Tumor specimens underwent hematoxylin and eosin (HE)

staining in the Department of Pathology at the Affiliated Hospital

of North Sichuan Medical College to determine the degree of

differentiation in RC. The samples were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at 20–25°C for 24 to 48 h, followed by

dehydration, paraffin infiltration, embedding, and sectioning to a

thickness of 4–6 µm. Prior to HE staining, the sections are baked

at 60–65°C for 1 h, then subjected to deparaffinization using a

graded ethanol series and xylene, followed by rehydration. The

sections are subsequently stained with hematoxylin for 3–5 min and

counterstained with eosin for 1–3 min at room temperature. After

staining, the sections are dehydrated through a graded alcohol

series, cleared with xylene, and finally mounted with neutral gum.

The prepared samples can be observed for morphological analysis

under a light microscope. According to classification standards

(2), RC tumors were classified as

one of the following: i) Well differentiated, (grade 1), glandular

ductal structures account for >95% of the tumor; ii) moderately

differentiated (grade 2), glandular ductal structures account for

50–95% of the tumor; iii) poorly differentiated (grade 3),

glandular ductal structures account for 5–50% of the tumor; or iv)

undifferentiated (grade 4), not obvious undifferentiated features

and proportion of glandular ducts accounts for <5% of the tumor.

The latter category encompasses mucinous adenocarcinomas and

impression cell carcinomas. When RC tumors demonstrated different

differentiation results, the predominant differentiation determined

the final diagnosis. RC was classified according to the degree of

differentiation into well differentiated and non-well

differentiated.

MRI protocol

All patients with RC underwent MRI using a MAGNETOM

Skyra 3.0T (Siemens Healthineers) scanner prior to surgery.

Patients fasted for 4–6 h before the examination and underwent

bowel preparation 2 h before the scan. An abdominal phased-array

coil was used. Scanning sequences included T1_tse_tra,

t2_blade_tra_p2_320 and ep2d_diff_tra_b50-1000_TRACEW_DFC_MIX. The

specific parameters used were as follows: i) T1_tse_tra: Repetition

time (TR) of 613 msec, Echo time (TE) of 10 msec, inversion angle

of 160°, slice thickness of 3.5 mm, interslice distance of 3.85 mm,

matrix of 320×288, Field-of-view (FOV) of 190×190 mm and voxel size

of 0.6×0.6×3.5 mm; ii) T2_blade_tra_p2_320: TR of 5,010 msec, TE of

87 msec, inversion angle of 160°, slice thickness of 3.5 mm,

interslice distance of 3.85 mm, matrix of 320×320, FOV of 190×190

mm and voxel size of 0.6×0.6×3.5 mm; and iii)

ep2d_diff_tra_b50-1000_TRACEW_DFC_MIX: TR of 5,400 msec, TE of 75

msec, inversion angle of 90°, slice thickness of 3.5 mm, interslice

distance of 3.85 mm, matrix of 150×142, FOV of 301×301 mm, voxel

size of 2.0×2.1×3.5 mm and b-values of 50 and 1,000

s/mm2.

Data collection

The data collected included age, sex,

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA

19-9), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), prealbumin,

albumin-to-globulin ratio, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin,

lactate, creatinine, leucine aminopeptidase, γ-glutamyl

transferase, adenosine deaminase, alkaline phosphatase, white blood

cells, red blood cells, serum albumin, hemoglobin, platelets,

neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes and the hemoglobin, albumin,

lymphocyte, and platelet score, all within 2 weeks before surgery.

Pathological data included differentiation grade, whilst imaging

data included the distance of the tumor from the anal verge, lesion

length, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, circumferential

resection margin (CRM) and extramural vascular invasion.

Imaging preprocessing, region of

interest (ROI) segmentation and peritumoral region dilation

Images were resampled at a voxel spacing of 1×1×1

mm3 before delineating the ROI and normalizing to

grayscale to compensate for voxel spatial differences and maintain

grayscale consistency, respectively. The entire ROI of T1-weighted

images (T1WI), T2-weighted images (T2WI) and diffusion-weighted

imaging (DWI) was outlined by a senior radiologist experienced in

diagnostic imaging of RC using open-source 3Dslicer software

(version 5.3.0; download.slicer.org/). Furthermore, and the entire

ROI of T1WI, T2WI and DWI was automatically analyzed using the

‘Margin’ module, which was used to automatically expand the 5-mm

region around the tumor to obtain a 3D segmented image.

Feature extraction

The image and the outlined ROI structure were

imported into 3D Slicer for feature extraction. The features

extracted by 3D Slicer were mainly performed using the open-source

plug-in (Pyradiomics v2.2.0; http://github.com/Radiomics/SlicerRadiomics). The

extracted features included mean, minimum, maximum, standard

deviation, skewness, kurtosis and others of the first-order

statistical features of the original image, as well as the surface

area, volume, surface area-to-volume ratio, sphericity, compactness

and 3D diameter of the morphological features. Moreover, the

following five types of texture features were extracted (18): i) Gray Level Cooccurence Matrix; ii)

Gray Level Run Length Matrix; iii) Gray Level Size Zone Matrix; iv)

Neighbouring Gray Tone Difference Matrix; and v) Gray Level

Dependence Matrix. Shape features were extracted from the original

images, while first-order and texture features were obtained from

both the original images and their filtered versions. The filtering

procedures included: Wavelet transformation (utilizing high-pass

(H) and low-pass (L) filters along the x, y, and z axes, generating

eight distinct decomposition combinations: HHH, HHL, HLH, LHH, LLL,

LLH, LHL, HLL) and Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) filtering (σ=4.0,

5.0, and 6.0 mm). In this case, the wavelet transform image was

created using the default parameters of 3D Slicer. The wavelet

sequence used was Daubechies (Db4). A 3-layer decomposition was

performed. The fill mode was symmetric filling. Quantization of 64

bins was applied. The sampling mode was custom sampling, with

specific sampling densities of x-, y- and z-axis sampling intervals

of 4, 5 and 6 voxels, respectively. A total of 1,223 features were

extracted.

Imbalanced data processing

The dataset comprised 46 patients with well

differentiated tumors and 178 with non-well differentiated tumors.

However, the marked imbalance between the two groups could impair

classifier performance; therefore, to address this, the adaptive

synthetic (ADASYN) technique was employed to balance the dataset

(19). After resampling, the

proportion of well differentiated and non-well differentiated cases

reached 1:1, with the minority class increasing from 20.5% in the

original dataset to 50.8% after ADASYN processing. Specifically,

the number of patients with well differentiated and non-well

differentiated tumors was 184 and 178, respectively. Subsequently,

ReliefF (20) was used for

dimensionality reduction, selecting 20 notable distinguishing

features. The balanced dataset was randomly divided into a training

set (70%) and a testing set (30%) after five-fold

cross-validation.

Establishment and evaluation of the

predictive model

In the current study, three machine learning

algorithms, logistic regression, Light Gradient Boosting Machine

(LightGBM) Classifier and Gaussian Naive Bayes, were selected to

predict the pathological differentiation of patients with RC based

on imaging features in and around the 5-mm region of the tumor in

T1WI, T2WI and DWI. The model was constructed using k-fold

cross-validation on the training set as a resampling method (k=5)

and the hyperparameters were adjusted using grid search to build

the best model using the optimal parameters. The receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted with the true positive rate

as the vertical coordinate and the false positive rate as the

horizontal coordinate, and the predictive efficacy of the model was

evaluated by calculating the area under the receiver operating

curve (AUC) and validated in the test group. The accuracy,

sensitivity and specificity corresponding to the optimal thresholds

of each model were obtained by selecting the optimal thresholds

based on the Youden index. Confusion matrix metrics, such as AUC,

accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and F1 score, were used to

evaluate the prediction performance and stability of each model.

Following the identification of the optimal classification method

and imaging sequence for predicting the pathological

differentiation of RC through comparison with confusion matrix

metrics and standard deviations derived from forest plots, the

dataset was re-divided into a training set (70%), a validation set

(15%) and a test set (15%). The validation set was used to adjust

the model parameters and the test set was used to evaluate the

system performance. T1-LightGBM models of intratumor and intratumor

+ peritumor were constructed, and then ROC curves, learning curves,

calibration plots and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to

further assess the clinical efficacy of the prediction models.

Calibration curves reflect how well the predicted probability

matches the actual outcome; DCA was used to assess the net benefit

of the model at different thresholds. Calibration was assessed

using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, followed by

development of the Shapley Additive explanations (SHAP) overall

presentation model and single-sample interpretation.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as n (%), whilst

continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range).

Differences between well differentiated and non-well differentiated

groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, Fisher's

exact test or Pearson's χ2 test. A two-sided P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Statistical analyses were performed using R 3.6.3 (https://www.r-project.org/) and Anaconda Python 3.7

(anaconda.com/).

Results

Patient characteristics

Postoperative pathological reports categorized the

224 patients into the well differentiated group (n=46) and the

non-well differentiated group (n=178). Baseline patient data are

presented in Table SI. CA 19-9,

AST and alanine aminotransferase were significantly associated with

pathological tissue differentiation (P<0.05), whilst no

significant differences were observed in other clinical indicators

or characteristics.

Feature analysis

A total of 1,224 features were extracted and

standardized. Table I presents the

application results of machine learning classification algorithms

on the balanced dataset generated using ADASYN. The T1-LightGBM

model demonstrated the best performance in the validation set.

| Table I.Evaluation of the performance of

classification models on imbalance dataset using the adaptive

synthetic technique in the validation set. |

Table I.

Evaluation of the performance of

classification models on imbalance dataset using the adaptive

synthetic technique in the validation set.

| Model | AUC (SD) | Accuracy (SD) | Sensitivity

(SD) | Specificity

(SD) | PPV(SD) | NPV (SD) | F1 score (SD) | Cutoff (SD) |

|---|

| Logistic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1WI | 0.637 (0.056) | 0.542 (0.039) | 0.552 (0.134) | 0.512 (0.145) | 0.591 (0.037) | 0.474 (0.089) | 0.563 (0.084) | 0.445 (0.045) |

|

T2WI | 0.533 (0.104) | 0.521 (0.100) | 0.184 (0.121) | 0.799 (0.256) | 0.600 (0.261) | 0.535 (0.086) | 0.229 (0.106) | 0.544 (0.006) |

|

DWI | 0.615 (0.079) | 0.568 (0.046) | 0.291 (0.176) | 0.779 (0.170) | 0.558 (0.176) | 0.556 (0.060) | 0.356 (0.169) | 0.556 (0.072) |

| LightGBM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1WI | 0.756 (0.051) | 0.700 (0.074) | 0.707 (0.122) | 0.700 (0.204) | 0.730 (0.140) | 0.709 (0.053) | 0.700 (0.070) | 0.452 (0.291) |

|

T2WI | 0.601 (0.096) | 0.561 (0.098) | 0.536 (0.234) | 0.628 (0.163) | 0.578 (0.079) | 0.598 (0.162) | 0.521 (0.130) | 0.668 (0.260) |

|

DWI | 0.750 (0.073) | 0.658 (0.080) | 0.600 (0.258) | 0.704 (0.292) | 0.763 (0.160) | 0.646 (0.130) | 0.608 (0.142) | 0.380 (0.194) |

| GNB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1WI | 0.672 (0.107) | 0.621 (0.094) | 0.856 (0.056) | 0.421 (0.181) | 0.591 (0.130) | 0.741 (0.098) | 0.687 (0.074) | 0.001 (0.002) |

|

T2WI | 0.501 (0.108) | 0.471 (0.068) | 0.293 (0.131) | 0.668 (0.251) | 0.552 (0.255) | 0.493 (0.040) | 0.324 (0.099) | 0.107 (0.032) |

|

DWI | 0.645 (0.085) | 0.579 (0.076) | 0.540 (0.160) | 0.620 (0.150) | 0.587 (0.050) | 0.585 (0.150) | 0.546 (0.081) | 0.039 (0.027) |

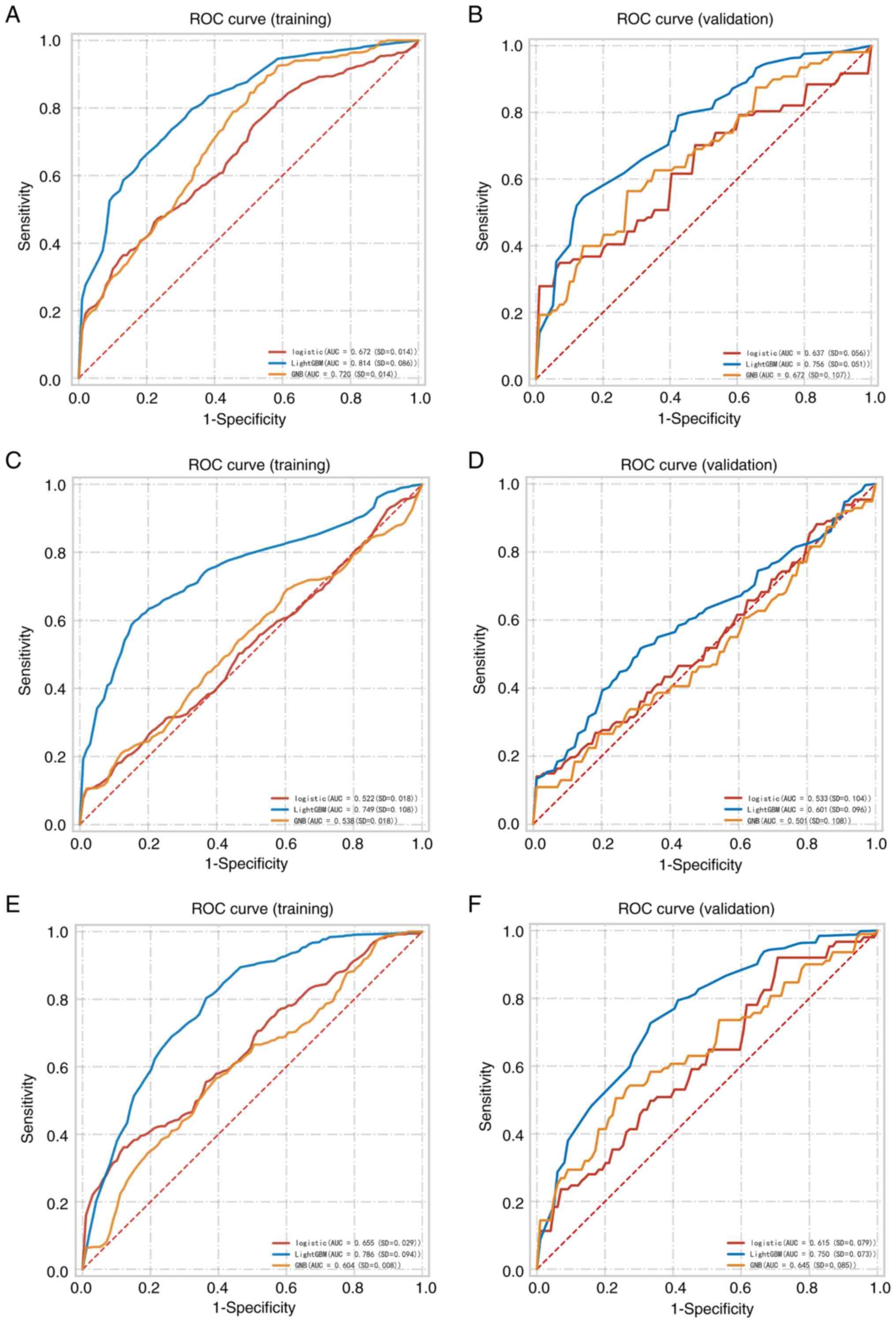

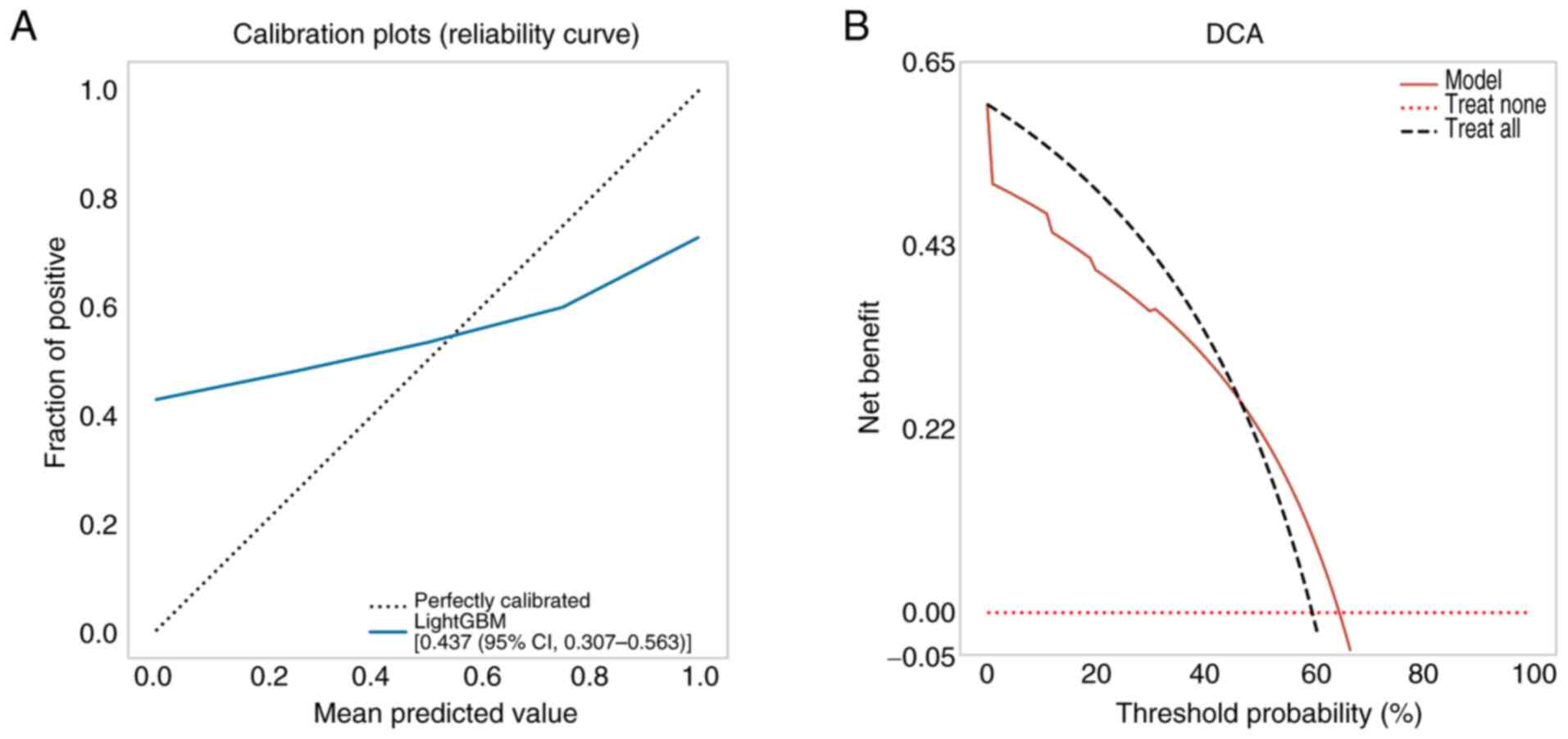

Model development and evaluation

A total of three machine learning algorithms were

used to develop predictive models. Fig.

1 illustrates the ROC curves for the different models

constructed for the intratumoral + peritumoral features. The AUC

range for the models was 0.510-0.756 across all validation cohorts.

The T1-LightGBM model, which combined intratumoral and peritumoral

features, achieved AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, positive predictive

value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and F1 score >0.7

in the validation set, outperforming the other eight models

(Table I). Moreover, the

T1-LightGBM model demonstrated the best predictive performance on

both training and validation sets (Fig.

1). The forest plot in Fig. S1

presents the ROC results for the nine models in predicting

pathological differentiation, indicating that the T1-LightGBM model

had the highest central value and the shortest error bars, further

confirming its superior stability.

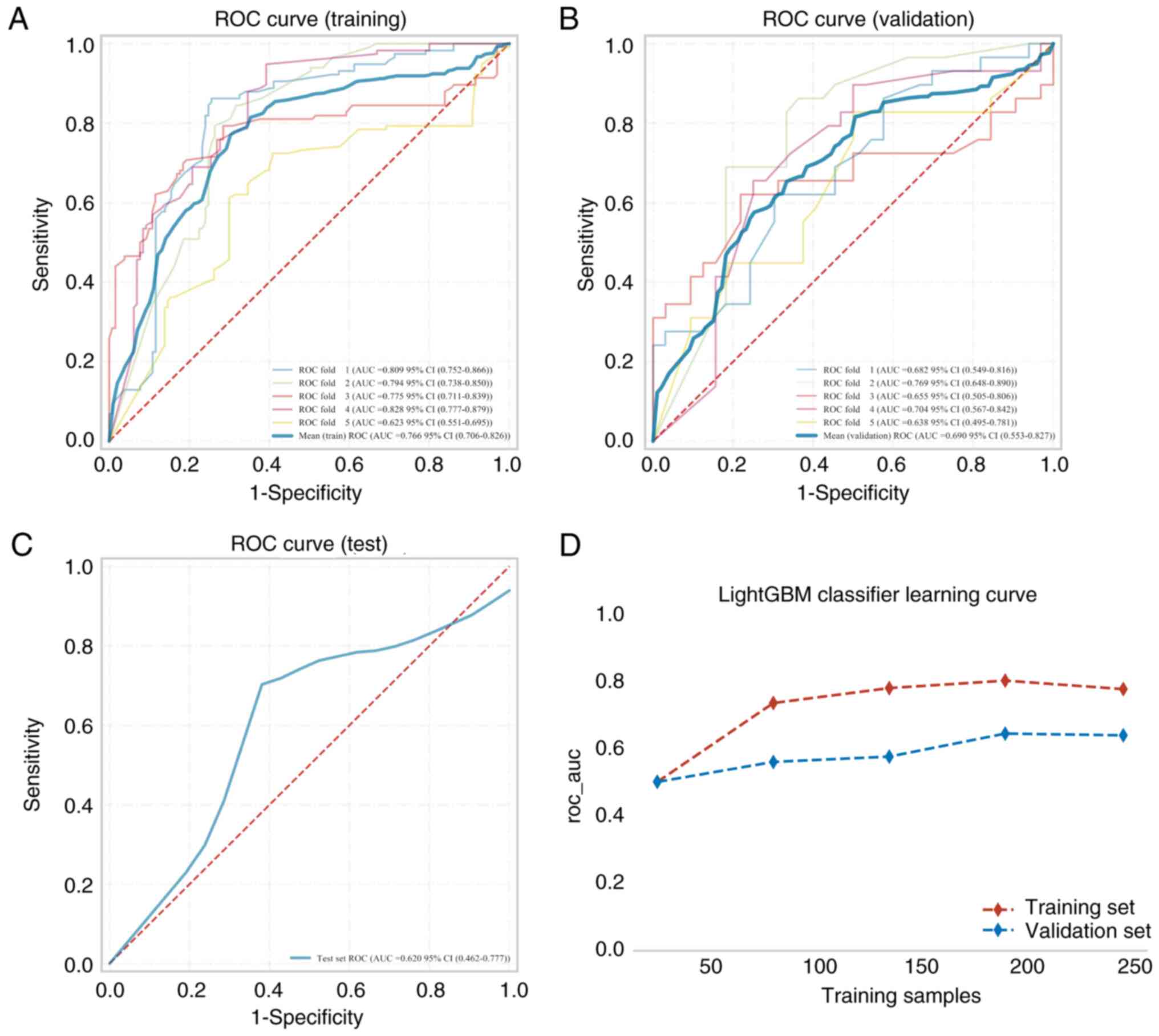

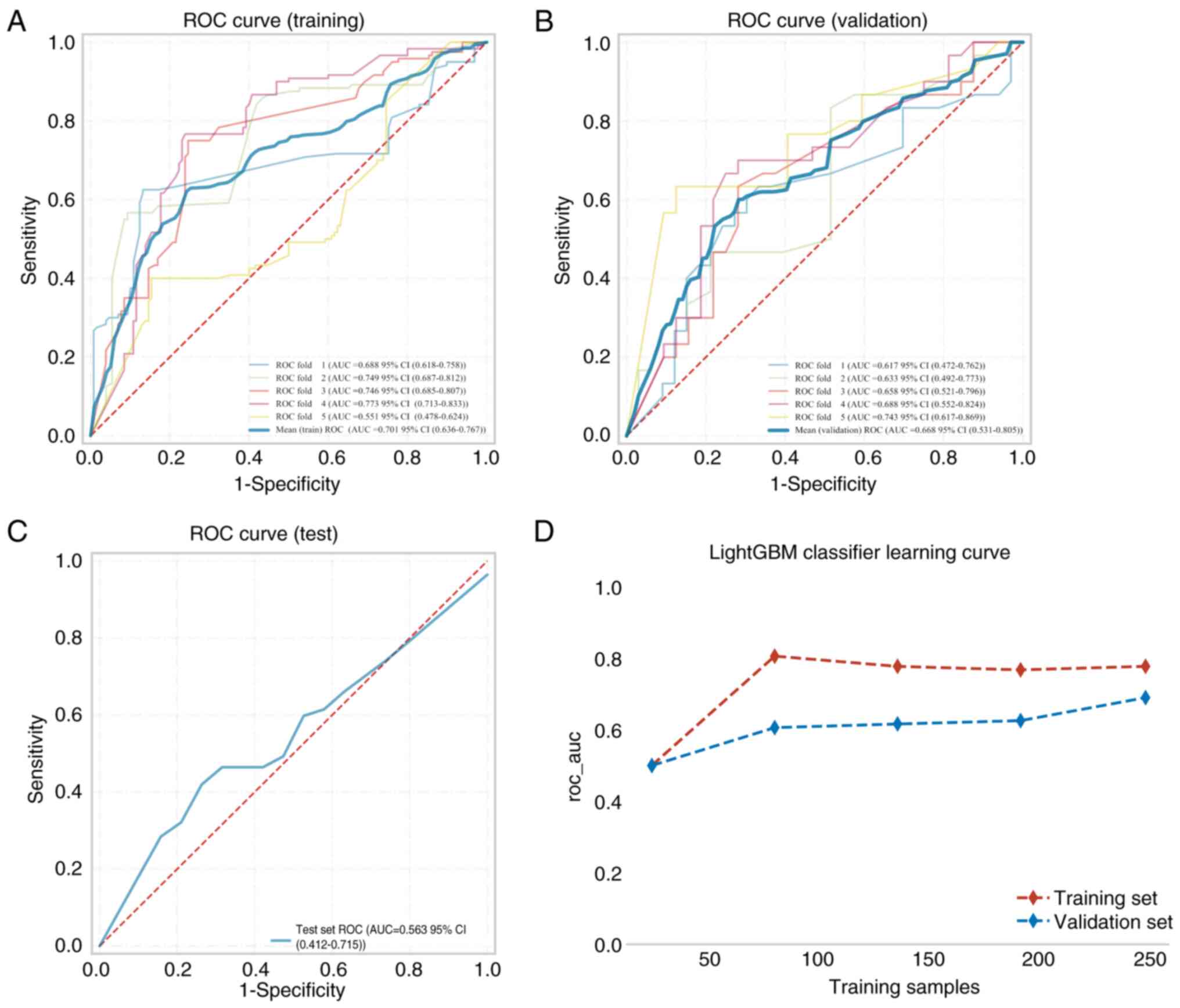

The LightGBM model was chosen as the best model for

predicting pathological differentiation, and the intratumoral +

peritumoral and intratumoral prediction models of T1-LightGBM were

constructed using 5-fold cross-validation. The AUC, cutoff,

accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for the training,

validation and test cohorts are presented in Table II, and the model ROC curves are

presented in Figs. 2 and 3. Assessment of the predictive performance

metrics indicated that the combined intratumoral + peritumoral

model outperformed the intratumoral-only model. Specifically, the

average AUC of the intratumoral + peritumoral model was 0.766 for

the training set, 0.690 for the validation set and 0.620 for the

test set (Fig. 2A-C; Table II), and the AUC of the training,

validation and test sets eventually stabilized at ~0.70. The AUC

was 0.668 in the training set, 0.701 in the validation set and

0.563 in the test set for the intratumor model (Table II; Fig.

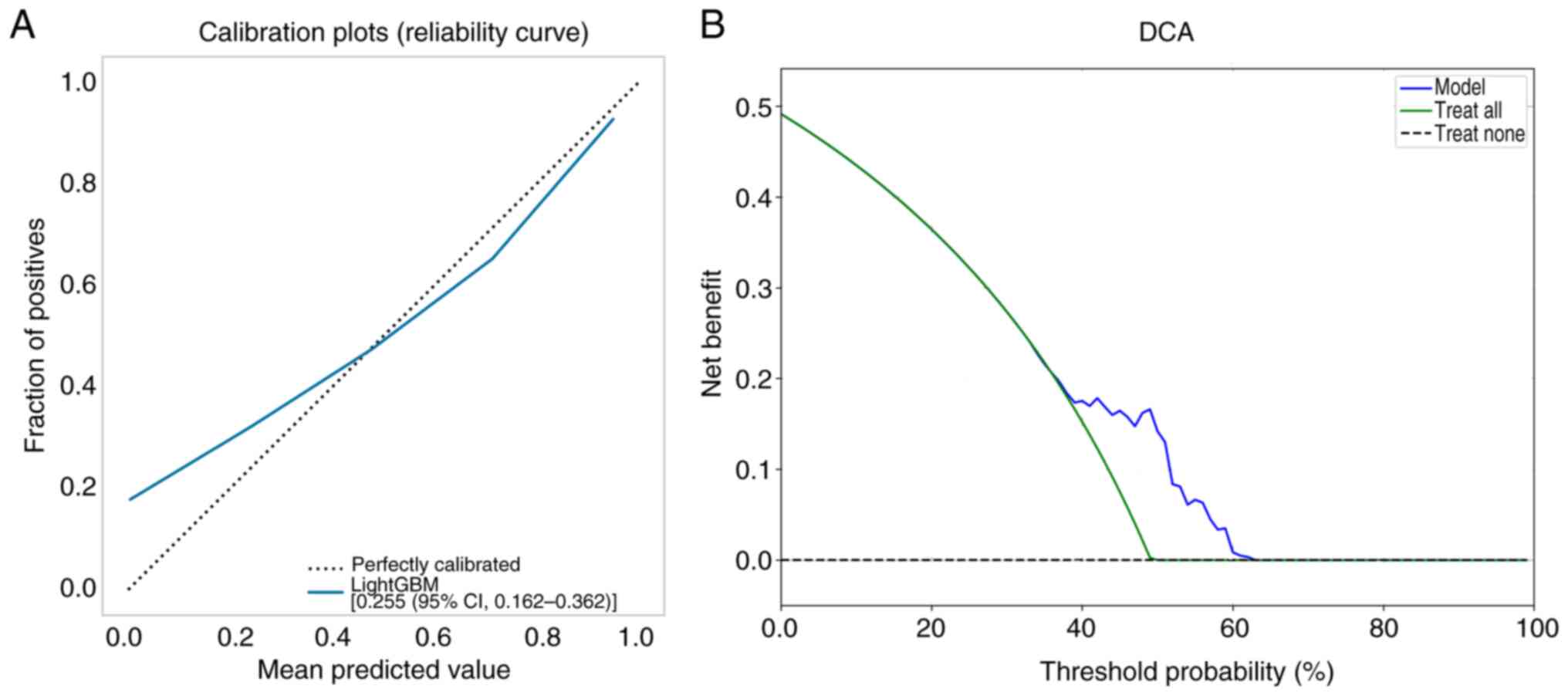

3A-C). Learning curves (Fig.

3D) were shown prior to assessing the accuracy of the model,

which indicated that the difference in error between the training

and the validation sets in the intratumoral + peritumoral 5-mm

model converged as the number of training samples increased. This

suggests that the model was not overfitted. Subsequently, the

calibration curves of the validation set were used to assess the

accuracy of the model. The results revealed that the intratumoral +

peritumoral 5-mm T1-LightGBM model had notable agreement with the

predicted probability of observed pathological differentiation

(Fig. 4A). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test

demonstrated that the intratumoral + peritumoral T1-LightGBM model

was well-calibrated (P=0.064). Subsequently, a DCA of the model was

constructed in the study, indicating that the intratumoral +

peritumoral model had a more marked net benefit than all-or-none

pathological differentiation with a risk threshold of <64%

(Fig. 4B). By contrast, the

calibration curves and DCA of the intratumoral LightGBM model

(Fig. 5) performed slightly worse

than the intratumoral + peritumoral prediction model. In summary,

the LightGBM model may be used for classification modeling tasks in

this dataset.

| Table II.Diagnostic performance of the Light

Gradient-Boosting Machine model constructed from intratumoral +

peritumoral and intratumoral features in predicting pathological

differentiation of rectal cancer. |

Table II.

Diagnostic performance of the Light

Gradient-Boosting Machine model constructed from intratumoral +

peritumoral and intratumoral features in predicting pathological

differentiation of rectal cancer.

| Model | AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff (95%

CI) | Accuracy (95%

CI) | Sensitivity (95%

CI) | Specificity (95%

CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | F1 score (95%

CI) |

|---|

| Training set |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral + | 0.690 | 0.383 | 0.661 | 0.731 | 0.599 | 0.626 | 0.725 | 0.668 |

|

peritumoral_ | (0.553-0.827) | (0.090-0.677) | (0.631-0.691) | (0.619-0.843) | (0.491-0.706) | (0.582-0.670) | (0.661-0.790) | (0.625-0.710) |

| 5

mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral | 0.668 | 0.408 | 0.677 | 0.593 | 0.753 | 0.692 | 0.669 | 0.668 |

|

| (0.531-0.805) | (0.088-0.729) | (0.629-0.725) | (0.512-0.674) | (0.690-0.817) | (0.624-0.760) | (0.627-0.711) | (0.531-0.805) |

| Validation set |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral + | 0.766 | 0.383 | 0.749 | 0.807 | 0.698 | 0.709 | 0.809 | 0.751 |

|

peritumoral_ | (0.706-0.826) | (0.090-0.677) | (0.701-0.798) | (0.719-0.895) | (0.616-0.780) | (0.655-0.763) | (0.733-0.886) | (0.702-0.800) |

| 5

mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral | 0.701 | 0.408 | 0.728 | 0.622 | 0.827 | 0.771 | 0.711 | 0.701 |

|

| (0.636-0.767) | (0.088-0.729) | (0.681-0.776) | (0.490-0.753) | (0.768-0.886) | (0.719-0.823) | (0.650-0.772) | (0.636-0.767) |

| Test set |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral + | 0.620 | 0.321 | 0.618 | 0.788 | 0.364 | 0.65 | 0.533 | 0.712 |

|

peritumoral_ | (0.462-0.777) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5

mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intratumoral | 0.563 | 0.349 | 0.571 | 0.357 | 0.786 | 0.625 | 0.55 | 0.455 |

|

| (0.412-0.715) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Model interpretation

The present study used SHAP plots to elucidate the

performance of the intratumoral + peritumoral T1-LightGBM based

prediction model for pathological differentiation. Fig. S2A illustrates that the feature

wavelet_HHH_glszm_Size_Zone_Non_Uniformity_Normalized was the most

critical predictor for pathological differentiation. Furthermore,

Fig. S2B illustrates a specific

case of predicting pathological differentiation in patients with

RC, where the SHAP values of features are visualized as forces that

either augment or diminish the predictive assessment. The baseline

was 0.740, representing the average SHAP value across all

predictions. The patient falls into the ‘true negative’ group, with

SHAP values <0.740, resulting in a predicted probability of

17.0% for well differentiated RC. Notably, the feature

wavelet_HHH_glszm_Size_Zone_Non_Uniformity_Normalized has a

negative (blue) value, indicating its contribution to the

prediction of non-well differentiated RC in this patient.

Discussion

The present study developed and assessed multiple

MRI-based radiomics models, with a particular focus on the value of

peritumoral features for the preoperative, noninvasive prediction

of the pathological differentiation grade of RC. The results

demonstrated that the LightGBM model based on the T1-weighted

sequence and combining intratumoral features with those from a 5-mm

peritumoral shell, achieved the best performance. These findings

suggest that peritumoral radiomic features can provide clinically

meaningful additional information for assessing the differentiation

of RC.

MRI serves a critical role in pre- and

post-treatment evaluation of RC (21). T1WI effectively delineates

anatomical structures, whilst T2WI provides high-resolution soft

tissue contrast, highlighting differences in internal lesion

composition. DWI, particularly at high b-values (b ≥800

sec/mm2), is highly sensitive to Brownian motion of

water molecules within viable tissues and tumors, offering insights

into cellular activity. DWI also demonstrates superior sensitivity

in detecting small tumor lesions and pelvic lymph nodes (22). In the present study, radiomic

features were extracted from intratumoral and peritumoral regions

across these three sequences. The SHAP method was employed to

interpret model outputs, identifying the five most contributory

features for distinguishing pathological differentiation:

T1_wavelet_HHH_glszm_Size_Zone_Non_Uniformity_Normalized,

original_first_order_Median,

wavelet_HHH_glszm_Low_Gray_Level_Zone_Emphasis,

Original_shape_Maximum_2D_Diameter_Slice and

wavelet_HHH_glszm_High_Gray_Level_Zone_Emphasis. The top-ranked

feature, wavelet_HHH_glszm_Size_Zone_Non_Uniformity_Normalized,

quantifies gray-level intensity uniformity within tumors,

reflecting spatial aggregation of high-signal regions (23). This metric may be associated with

tumor angiogenesis or necrotic zone distribution (24), critical for evaluating structural

complexity and homogeneity (25).

Such heterogeneity aligns with the infiltrative growth patterns of

malignant RC, often manifesting as non-spherical morphology

(26). Collectively, these features

emphasize the importance of integrating morphological, statistical

and textural characteristics for comprehensive tumor

characterization.

Whilst aligning with established machine learning

methodologies, the novelty of the current study involves dataset

construction and feature selection. Prior research predominantly

focused on intratumoral regions, neglecting peritumoral

contributions. However, emerging evidence has highlighted the

prognostic value of peritumoral features in tumor biology, as

demonstrated in soft tissue sarcoma (27), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(28), gastric cancer (29), lung cancer (30,31)

and ovarian cancer (32). For

instance, Liu et al (17)

highlighted the predictive utility of peritumoral features in HCC

differentiation, whilst Barge et al (33) identified peritumoral texture

features in T1WI as key discriminators for tumor grading. Xu et

al (22) further reported that

models combining intratumoral and peritumoral (3 and 5 mm) features

outperformed single-region models in predicting lymphovascular

invasion in RC. Based on the aforementioned rationale, the current

study designated a 5-mm peritumoral region as the primary area for

analysis. This choice was informed, on the one hand, by clinical

consensus regarding the CRM in RC: A CRM of >1 mm is generally

considered a ‘safe margin’ (34),

although the optimal clearance remains controversial. A

meta-analysis reported that, whilst a margin of >1 mm improves

prognosis, a margin of >1 cm may yield superior oncological

outcomes (35). On the other hand,

prior peritumoral radiomics studies in lung cancer (36) and gliomas (37) suggested that regions closer to the

tumor harbor richer heterogeneity; as the boundary expands outward,

more normal tissue is included in the ROI, potentially diluting

meaningful structural differences. Therefore, a 5-mm peritumoral

band is likely to capture spatial heterogeneity whilst maximally

preserving imaging signals related to tumor biology. This provides

an effective basis for noninvasive, preoperative prediction of the

pathological grading of RC.

Previous research has explored the relationship

between functional MRI parameters and the pathological grading of

RC; however, the findings have been inconsistent. Kim et al

(38) reported that the Ktrans

value in the well differentiated group in their study was

significantly higher than in the moderately differentiated group

(0.127±0.032 vs. 0.084±0.036; P=0.036). By contrast, Shen et

al (39) reported that the

Ktrans value was significantly associated with the pathological

differentiation of RC (poor, 0.284±0.068 and moderately:

0.280±0.067 vs. well: 0.182±0.153, P=0.004), with the well

differentiated group showing lower Ktrans values than the

moderately differentiated group. However, the values between the

moderately and poorly differentiated groups were similar. n DWI,

apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values have also been used to

assess pathological grading. Curvo-Semedo et al (40) noted that poorly differentiated

tumors tended to exhibit lower ADC values compared with moderately

and highly differentiated tumors, although statistical significance

was not reached. Zhou et al (41) also reported no significant ADC

differences within the traditional WHO grading system. However,

when adopting the poorly differentiated clusters grading system

(42), ADC and intravoxel

incoherent motion (IVIM) parameters, such as perfusion fraction f

and pseudo-diffusion coefficient D*, demonstrated significant

differences between high- and low-grade tumors, with clear

correlations between perfusion metrics and tumor grade (r=0.842,

P<0.001; and r=0.356, P=0.011). This suggests that IVIM

parameters may be valuable for grading. Yuan et al (43) further extended the analysis to the

peritumoral region and reported that higher peritumoral-to-tumor

ADC ratios and ADCp mean values were associated with poor

differentiation, T3-4 stage and adverse features such as lymph node

metastasis (LNM), extranodal extension, tumor deposits and

lymphovascular invasion (LVI). They also reported that the

peritumoral-to-tumor ADC ratio outperformed tumor ADC in assessing

prognostic factors.

Clinically, treatment strategies for RC are

primarily based on TNM staging, which does not fully capture

inter-patient heterogeneity within the same stage. Pathological

differentiation serves as an important complementary indicator to

optimize risk stratification and therapeutic decision-making

(44,45). Numerous studies have reported that

poor differentiation is associated with higher local recurrence and

worse overall survival compared with well differentiation (46,47).

Therefore, it is classed as a high-risk feature in the European

Society for Medical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer

Network (NCCN) guidelines (10).

The NCCN and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

further specify in their local excision criteria for early RC that

appropriate candidates should have tumors of <3 cm,

well-to-moderately differentiated histology and no LVI (48). Additional studies support

incorporating tumor grade into risk assessment. Cho et al

(49) reported that in pT1 RC and

colon cancer, moderate/poor differentiation was significantly

associated with LNM (P=0.006 and P=0.002, respectively) and was an

independent predictor of LNM (odds ratio, 1.38-8.13; P=0.008).

Emile et al (50) developed

a risk-scoring model integrating tumor grade with nodal stage and

reported that, compared with well differentiated rectal

adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumors

had a markedly increased risk of LVI (more than threefold).

Considering the similar trends observed for moderately and poorly

differentiated tumors across functional imaging parameters, and the

frequent consideration in clinical guidelines and prior studies

that these categories share comparable aggressive biology, the

present study combined moderately and poorly differentiated RCs

into a ‘non-well differentiated’ group. This grouping strategy

helps clarify gradations of tumor aggressiveness, enhances the

ability of the model to identify clinically high-risk patients, and

provides more accurate guidance for treatment decisions. For

example, in mid-to-low RC initially staged as T3a/b by MRI, if the

model predicts moderate/poor differentiation, clinicians may

prioritize neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy over immediate surgery, as

the true biological behavior may be more aggressive than suggested

by staging alone (51).

In addition to imaging features, studies by

Shibutani et al (52) and

Ryuk et al (53) reported

that serum CEA and CA 19-9 are independent prognostic factors for

RC. Elevated preoperative CEA levels were associated with tumor

size and T-stage, whilst high CA19-9 levels were reported to be

associated with tumor stage (54).

This is consistent with the findings of the present study, in which

elevated CA 19-9 levels demonstrated a significant association with

poorer differentiated RC (P=0.014), further supporting the

auxiliary value of serum biomarkers in assessing tumor biology.

Serum biomarkers reflect systemic tumor burden and metabolic status

(55), whereas radiomic features

quantify local tumor heterogeneity (24). Their combination could provide

multidimensional predictive information, enhancing accuracy and

clinical utility.

However, the current study has several limitations.

First, it adopted a single-center retrospective design which may

introduce selection bias, and the sample size was relatively small,

particularly for the independent test cohort. More multi-center

cohorts are needed for external validation to assess the robustness

and reproducibility of the predictive model and to strengthen the

conclusions of the present study. Second, radiomics features are

sensitive to scanning protocols and equipment parameters.

Consequently, standardized image acquisition and feature

harmonization should be promoted in the future to improve the

generalizability of the model. In addition, tumor region annotation

currently relies on manual delineation which may introduce

inter-observer variability. Developing automatic or semi-automatic

segmentation algorithms is an important direction for improvement.

Finally, the current study focused solely on radiomics features. In

future work, the plan is to explore integration with

clinicopathological indicators and molecular biomarkers, such as

genomic and transcriptomic features, to build multi-modal fusion

models, enabling more refined patient stratification and further

enhancing clinical translational value.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the

potential of peritumoral features as a non-invasive tool for

predicting RC differentiation. Notably, the integrated model

employing the LightGBM algorithm on T1-weighted sequences, which

combined both intratumoral and 5-mm peritumoral features,

demonstrated promising predictive potential for individualized RC

differentiation, thereby contributing to the development of

personalized treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL collected, analyzed and organized data, and

participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. HZ provided

supervision, guided the manuscript revision process and assisted in

data analysis. QZ performed data collection and operated

specialized software. JY contributed to the writing and revision of

the article. HL and JY conceived the study and designed the

methodology. HL and JY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed according to the

guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the

Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan

Medical College (approval no. 2024ER490-1). The requirement for

informed consent was waived.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, : The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jiang C, Liu Y, Xu C, Shen Y, Xu Q and Gu

L: Pathological features of lymph nodes around inferior mesenteric

artery in rectal cancer: A retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol.

19:1522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Junginger T, Goenner U, Hitzler M, Trinh

TT, Heintz A, Wollschlaeger D and Blettner M: Long-term oncologic

outcome after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal

carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 59:8–15. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro LA, Chow OS, Shi

Q, Carrero XW, Lynn PB, Thomas CR Jr, Chan E, Cataldo PA, Marcet

JE, et al: Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal

cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision

(ACOSOG Z6041): Results of an open-label, single-arm,

multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16:1537–1546.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown

G, Rödel C, Cervantes A and Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee, :

Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 29 (Suppl 4):iv2632018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ueno H, Hase K, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H,

Yoshii S, Kudo SE, Tanaka M, Akagi Y, Suto T, Nagata S, et al:

Novel risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early invasive

colorectal cancer: A multi-institution pathology review. J

Gastroenterol. 49:1314–1323. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Doornebosch PG, Ferenschild FT, de Wilt

JH, Dawson I, Tetteroo GW and de Graaf EJ: Treatment of recurrence

after transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for T1 rectal cancer.

Dis Colon Rectum. 53:1234–1239. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hahnloser D, Wolff BG, Larson DW, Ping J

and Nivatvongs S: Immediate radical resection after local excision

of rectal cancer: An oncologic compromise? Dis Colon Rectum.

48:429–437. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fields AC, Lu P, Hu F, Hirji S, Irani J,

Bleday R, Melnitchouk N and Goldberg JE: Lymph node positivity in

T1/T2 rectal cancer: A word of caution in an era of increased

incidence and changing biology for rectal cancer. J Gastrointest

Surg. 25:1029–1035. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Horvat N, Carlos Tavares Rocha C, Clemente

Oliveira B, Petkovska I and Gollub MJ: MRI of rectal cancer: Tumor

staging, imaging techniques, and management. Radiographics.

39:367–387. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kleiner DE: Hepatocellular carcinoma:

Liver biopsy in the balance. Hepatology. 68:13–15. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Song M, Li S, Wang H, Hu K, Wang F, Teng

H, Wang Z, Liu J, Jia AY, Cai Y, et al: MRI radiomics independent

of clinical baseline characteristics and neoadjuvant treatment

modalities predicts response to neoadjuvant therapy in rectal

cancer. Br J Cancer. 127:249–257. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ameli S, Venkatesh BA, Shaghaghi M,

Ghadimi M, Hazhirkarzar B, Rezvani Habibabadi R, Aliyari Ghasabeh

M, Khoshpouri P, Pandey A, Pandey P, et al: Role of MRI-derived

radiomics features in determining degree of tumor differentiation

of hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel). 12:23862022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu HF, Lu Y, Wang Q, Lu YJ and Xing W:

Machine learning-based CEMRI radiomics integrating LI-RADS features

achieves optimal evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma

differentiation. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 10:2103–2115. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hirata E and Sahai E: Tumor

microenvironment and differential responses to therapy. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Med. 7:a0267812017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu HF, Wang M, Wang Q, Lu Y, Lu YJ, Sheng

Y, Xing F, Zhang JL, Yu SN and Xing W: Multiparametric MRI-based

intratumoral and peritumoral radiomics for predicting the

pathological differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Insights

Imaging. 15:972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Park H, Kim KA, Jung JH, Rhie J and Choi

SY: MRI features and texture analysis for the early prediction of

therapeutic response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and tumor

recurrence of locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur Radiol.

30:4201–4211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kim JH, Shin JK, Lee H, Lee DH, Kang JH,

Cho KH, Lee YG, Chon K, Baek SS and Park Y: Improving the

performance of machine learning models for early warning of harmful

algal blooms using an adaptive synthetic sampling method. Water

Res. 207:1178212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Khan TM, Xu S, Khan ZG and Uzair Chishti

M: Implementing multilabeling, ADASYN, and relieff techniques for

classification of breast cancer diagnostic through machine

learning: Efficient computer-aided diagnostic system. J Healthc

Eng. 2021:55776362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bates DDB, Homsi ME, Chang KJ, Lalwani N,

Horvat N and Sheedy SP: MRI for rectal cancer: Staging, mrCRM,

EMVI, lymph node staging and post-treatment response. Clin

Colorectal Cancer. 21:10–18. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xu F, Hong J and Wu X: An integrative

clinical and intra- and peritumoral MRI radiomics nomogram for the

preoperative prediction of lymphovascular invasion in rectal

cancer. Acad Radiol. 32:3989–4001. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nayak P, Sinha S, Goda JS, Sahu A, Joshi

K, Choudhary OR, Mhatre R, Mummudi N and Agarwal JP: Computerized

tomography-based first order tumor texture features in non-small

cell lung carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiation: A

simplistic and potential surrogate imaging marker for survival. J

Cancer Res Ther. 19:366–375. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bernatowicz K, Amat R, Prior O, Frigola J,

Ligero M, Grussu F, Zatse C, Serna G, Nuciforo P, Toledo R, et al:

Radiomics signature for dynamic monitoring of tumor inflamed

microenvironment and immunotherapy response prediction. J

Immunother Cancer. 13:e0091402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang X, Dai S, Wang Q, Chai X and Xian J:

Investigation of MRI-based radiomics model in differentiation

between sinonasal primary lymphomas and squamous cell carcinomas.

Jpn J Radiol. 39:755–762. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang L, Yang Y, Wang T, Chen X, Tang M,

Deng J, Cai Z and Cui W: Intratumoral and peritumoral MRI-based

radiomics prediction of histopathological grade in soft tissue

sarcomas: A two-center study. Cancer Imaging. 23:1032023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin P, Xie W, Li Y, Zhang C, Wu H, Wan H,

Gao M, Liang F, Han P, Chen R, et al: Intratumoral and peritumoral

radiomics of MRIs predicts pathologic complete response to

neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in patients with head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 12:e0096162024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jiang Y, Wang H, Wu J, Chen C, Yuan Q,

Huang W, Li T, Xi S, Hu Y, Zhou Z, et al: Noninvasive imaging

evaluation of tumor immune microenvironment to predict outcomes in

gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 31:760–768. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pérez-Morales J, Tunali I, Stringfield O,

Eschrich SA, Balagurunathan Y, Gillies RJ and Schabath MB:

Peritumoral and intratumoral radiomic features predict survival

outcomes among patients diagnosed in lung cancer screening. Sci

Rep. 10:105282020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li Y, Wang P, Xu J, Shi X, Yin T and Teng

F: Noninvasive radiomic biomarkers for predicting pseudoprogression

and hyperprogression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer

treated with immune checkpoint inhibition. Oncoimmunology.

13:23126282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang X, Wei M, Chen Y, Jia J, Zhang Y, Dai

Y, Qin C, Bai G and Chen S: Intratumoral and peritumoral MRI-based

radiomics for predicting extrapelvic peritoneal metastasis in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Insights Imaging. 15:2812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Barge P, Oevermann A, Maiolini A and

Durand A: Machine learning predicts histologic type and grade of

canine gliomas based on MRI texture analysis. Vet Radiol

Ultrasound. 64:724–732. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Scaife CL and Curley SA: Complication,

local recurrence, and survival rates after radiofrequency ablation

for hepatic malignancies. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 12:243–255. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Margonis GA, Sergentanis TN,

Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Andreatos N, Tzanninis IG, Sasaki K,

Psaltopoulou T, Wang J, Buettner S, Papalois ΑE, et al: Impact of

surgical margin width on recurrence and overall survival following

R0 hepatic resection of colorectal metastases: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 267:1047–1055. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tang X, Huang H, Du P, Wang L, Yin H and

Xu X: Intratumoral and peritumoral CT-based radiomics strategy

reveals distinct subtypes of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cancer

Res Clin Oncol. 148:2247–2260. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cheng J, Liu J, Yue H, Bai H, Pan Y and

Wang J: Prediction of glioma grade using intratumoral and

peritumoral radiomic features from multiparametric MRI images.

IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 19:1084–1095. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim HR, Kim SH and Nam KH: Association

between dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI parameters and prognostic

factors in patients with primary rectal cancer. Curr Oncol.

30:2543–2554. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shen FU, Lu J, Chen L, Wang Z and Chen Y:

Diagnostic value of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance

imaging in rectal cancer and its correlation with tumor

differentiation. Mol Clin Oncol. 4:500–506. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Curvo-Semedo L, Lambregts DM, Maas M,

Beets GL, Caseiro-Alves F and Beets-Tan RG: Diffusion-weighted MRI

in rectal cancer: Apparent diffusion coefficient as a potential

noninvasive marker of tumor aggressiveness. J Magn Reson Imaging.

35:1365–1371. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhou B, Zhou Y, Tang Y, Bao Y, Zou L, Yao

Z and Feng X: Intravoxel incoherent motion MRI for rectal cancer:

Correlation of diffusion and perfusion characteristics with

clinical-pathologic factors. Acta Radiol. 64:898–906. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Barresi V, Reggiani Bonetti L, Branca G,

Di Gregorio C, Ponz de Leon M and Tuccari G: Colorectal carcinoma

grading by quantifying poorly differentiated cell clusters is more

reproducible and provides more robust prognostic information than

conventional grading. Virchows Arch. 461:621–628. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yuan Y, Chen XL, Li ZL, Chen GW, Liu H,

Liu YS, Pang MH, Liu SY, Pu H and Li H: The application of apparent

diffusion coefficients derived from intratumoral and peritumoral

zones for assessing pathologic prognostic factors in rectal cancer.

Eur Radiol. 32:5106–5118. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lou S, Huang Y, Du F, Xue J, Mo G, Li H,

Yu Z, Li Y, Wang H, Huang Y, et al: Development and validation of a

deep learning-based pathomics signature for prognosis and

chemotherapy benefits in colorectal cancer: A retrospective

multicenter cohort study. Front Immunol. 16:16029092025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Huang YQ, Chen XB, Cui YF, Yang F, Huang

SX, Li ZH, Ying YJ, Li SY, Li MH, Gao P, et al: Enhanced risk

stratification for stage II colorectal cancer using deep

learning-based CT classifier and pathological markers to optimize

adjuvant therapy decision. Ann Oncol. 36:1178–1189. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Oh SY, Park JY, Yang KM, Jeong SA, Kwon

YJ, Jung YT, Ma CH, Yun KW, Yoon KH, Kwak JY and Yu CS: Oncologic

outcomes of surgically treated colorectal cancer in octogenarians:

A comparative study using inverse probability of treatment

weighting (IPTW). BMC Gastroenterol. 25:2762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yang Y, Xu H, Chen G and Pan Y: Stratified

prognostic value of pathological response to preoperative treatment

in yp II/III rectal cancer. Front Oncol. 11:7951372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tjandra JJ, Kilkenny JW, Buie WD, Hyman N,

Simmang C, Anthony T, Orsay C, Church J, Otchy D, Cohen J, et al:

Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised).

Dis Colon Rectum. 48:411–423. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Cho SH, Park BS, Son GM, Kim HS, Kim SJ,

Park SB, Choi CW, Kim HW, Shin DH and Yun MS: Differences in

factors predicting lymph node metastasis between pT1 rectal cancer

and pT1 colon cancer: A retrospective study. Am Surg. 89:5829–5836.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Emile SH, Horesh N, Garoufalia Z, Gefen R,

Wignakumar A and Wexner SD: Development and validation of a

predictive score for preoperative detection of lymphovascular

invasion in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 131:1081–1089. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Keller DS, Berho M, Perez RO, Wexner SD

and Chand M: The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17:414–429. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Ohtani

H, Sakurai K, Toyokawa T, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Ohira M and

Hirakawa K: Significance of CEA and CA19-9 combination as a

prognostic indicator and for recurrence monitoring in patients with

stage II colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 34:3753–3758.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ryuk JP, Choi GS, Park JS, Kim HJ, Park

SY, Yoon GS, Jun SH and Kwon YC: Predictive factors and the

prognosis of recurrence of colorectal cancer within 2 years after

curative resection. Ann Surg Treat Res. 86:143–151. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang J, Wang X, Yu F, Chen J, Zhao S,

Zhang D, Yu Y, Liu X, Tang H and Peng Z: Combined detection of

preoperative serum CEA, CA19-9 and CA242 improve prognostic

prediction of surgically treated colorectal cancer patients. Int J

Clin Exp Pathol. 8:14853–14863. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Farag CM, Antar R, Akosman S, Ng M and

Whalen MJ: What is hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, platelet (HALP)

score? A comprehensive literature review of HALP's prognostic

ability in different cancer types. Oncotarget. 14:153–172. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|