Introduction

Angiosarcoma is a highly aggressive malignant tumor

of endothelial cells that arises from blood or lymphatic vessels

and accounts for ~2% of all soft tissue sarcomas (1). Primary pulmonary angiosarcoma is

uncommon and is usually identified only after it has spread to

other parts of the body (2). This

report describes a case of primary pulmonary angiosarcoma and

highlights the complexities of its diagnosis and treatment.

Primary pulmonary angiosarcoma is difficult to

diagnose because its clinical symptoms are nonspecific (3,4).

Patients with this condition frequently present with symptoms such

as hemoptysis, chest pain and shortness of breath (5,6).

However, these symptoms are often ascribed to other conditions,

resulting in delayed diagnosis. Furthermore, the radiological

features of pulmonary angiosarcoma are typically nonspecific and

may resemble those of other pulmonary disorders (7,8).

This case report presents an uncommon manifestation

of primary pulmonary angiosarcoma, delineates the typical

diagnostic challenges and investigates potential therapeutic

targets revealed through genetic analysis.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and

hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining

IHC analysis of programmed cell death ligand 1

(PD-L1), vimentin, CD31, CD34, ETS-related gene (ERG) and factor

VIII antibody (VIII-RA). Experiment was conducted using

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections. Staining

included routine dewaxing, antigen retrieval, inhibition of

endogenous peroxidase activity, incubation with primary and

secondary antibodies and counterstaining. The primary antibodies

included anti-vimentin antibody (cat. no. AB5733; 1:1,000

dilution), rabbit anti-CD31 antibody (cat. no. SAB5700639; 1:100

dilution), rabbit anti-CD34 antibody (cat. no. HPA036722, 1:200

dilution) and anti-CD274 (cat. no SAB4301882; 1:100 dilution; all

from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), factor VIII-related antigen (cat.

no. 36B11; 1:50 dilution; Novocastra) and rabbit monoclonal ERG

antibody (cat. no. IPDX17045; 1:100 dilution; IPODIX). The

secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (cat. no.

ab150077; 1:2,000; Abcam). Subsequently, the samples were evaluated

using a microscope (DMi3000 B; Leica Microsystems) to calculate the

tumor proportion score and the comprehensive positive score.

HE staining was conducted to confirm the

histopathological diagnosis. The tissue sections were first

de-waxed using xylene to remove the paraffin. Subsequently, they

were made transparent through a series of alcohol treatments. Next,

hematoxylin (cat. no. H9627; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was used to

stain the nuclei of the sections. Subsequently, distilled water was

used to rinse off the excess hematoxylin. After that, eosin (cat.

no. E4009; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was used for counter-staining

to enhance cell differentiation. Finally, the sections were

dehydrated through a series of alcohol treatments and covered with

a coverslip for mounting. The sections were then observed using a

light microscope (DMi3000 B; Leica Microsystems) to evaluate the

tissue structure, cell morphology, and general pathological

features.

Genetic testing

Genomic DNA was isolated from the patient's blood

sample following established protocols (9), including proteinase K (cat. no.

P2308-5MG; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) digestion and

phenol-chloroform extraction. Targeted next-generation sequencing

was then conducted using a custom-designed panel encompassing 1,238

clinically relevant genes, including exons 2–22 of PD-L1.

Next-generation sequencing library preparation involved genomic DNA

fragmentation, end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation and size

selection (10). Sequencing was

performed on an Illumina platform, achieving a minimum depth of

30-fold coverage within the targeted regions. The library was

constructed using the Nextera XT kit (Illumina, Inc.), and

sequencing was performed on the NextSeq™ 500 (Illumina, Inc.)

platform using the 2×150 bp kit according to the manufacturer's

instructions (11). Sequence reads

were aligned using BWA-MEM (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml) and variant

calling was performed with the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)

(https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us) (12). The identified mutations were

annotated and classified based on data from the Human Genome

Variation Database (ClinVar) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), Single

Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp) and Catalogue of

Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/login). Filtering

steps were subsequently applied to remove low-quality reads and

false-positive variants. The final variant report provided

comprehensive clinical information, including the identification

and categorization of all clinically significant mutations, thereby

facilitating informed therapeutic decision-making. These data have

been uploaded to the SRA database, with the BioProject ID being

PRJNA1344604. They are available for download (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP636518&o=acc_s%3Aa).

Case report

A 71-year-old man presented with a history of

hypertension, cerebral infarction and coronary artery disease. The

patient had a smoking history of >50 years, with an average

daily consumption of 20 cigarettes. No significant family medical

history was noted. The patient was admitted to the Department of

Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine at the Banan Affiliated

Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China) in

February 2023 after the onset of symptoms, including cough, sputum

production and unexplained dyspnea.

On admission, the patient was conscious and

cooperative. The patient exhibited a productive cough with

expectoration of phlegm containing dark red blood clots,

accompanied by fatigue and anorexia. The patient subsequently

reported pain localized to the right hemithorax, accompanied by

worsening cough. The pain radiated to the right shoulder and dorsal

region.

Ultrasound examination of the thorax revealed

pleural effusion on the right side. Physical assessment

demonstrated diminished breath sounds in the right lung, but no

significant wet or dry adventitious sounds were detected in the

left lung. Thoracentesis yielded 350 ml of pleural fluid. Chest

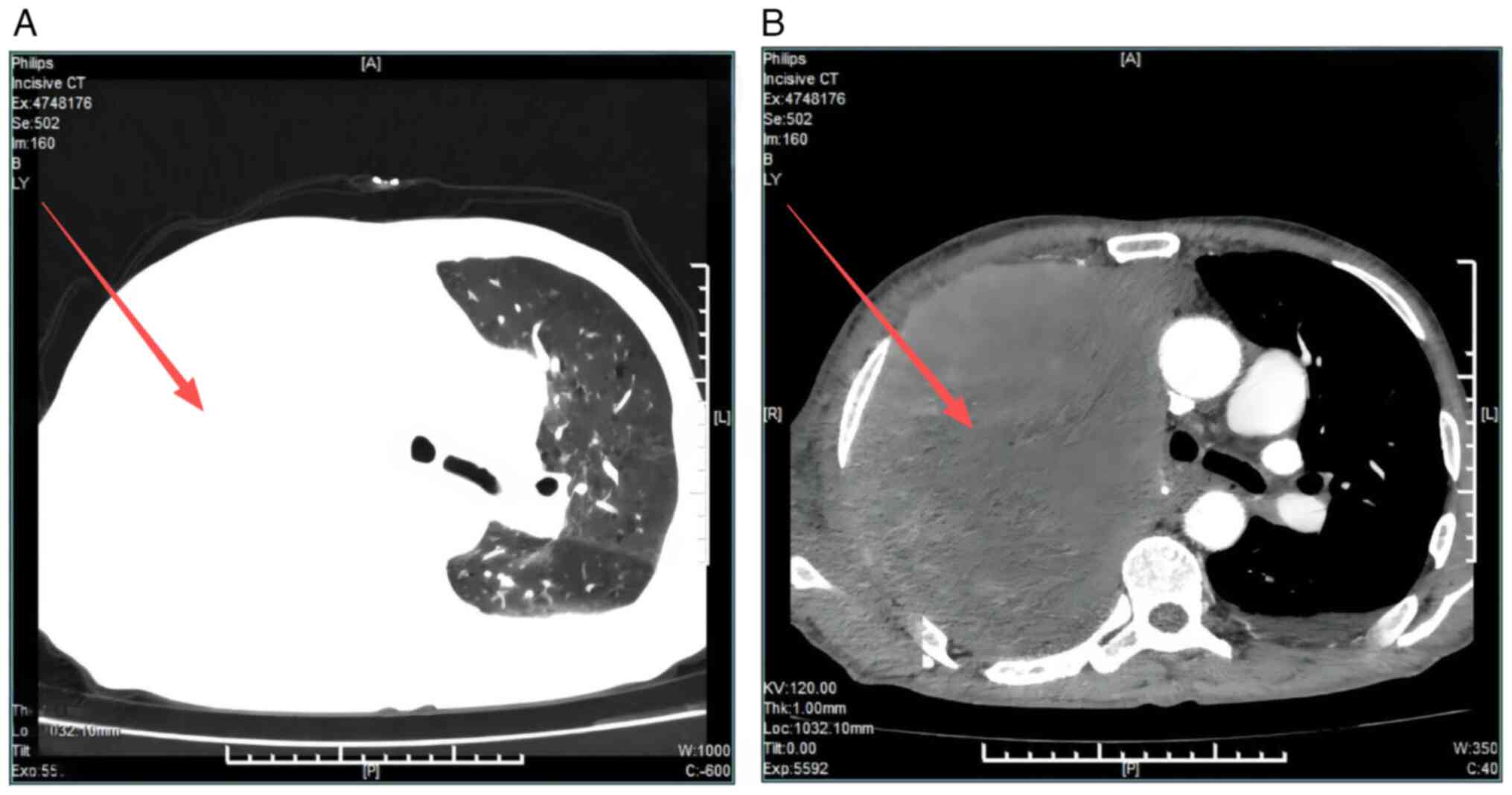

computed tomography (CT) imaging (Fig.

1, Videos S1 and S2) demonstrated the following findings:

i) A mass located in the right lung measuring ~147×113 mm, highly

suggestive of primary lung carcinoma with mediastinal invasion;

associated right pulmonary bronchial obstruction with resultant

atelectasis; involvement of the right pulmonary arterial trunk;

suspected mediastinal lymphadenopathy; evidence of right pleural

metastasis; and probable metastasis to the right ribs. ii) A small

volume of bilateral pleural effusions. iii) A nodule in the left

adrenal gland, with metastatic involvement excluded. iv) Mild

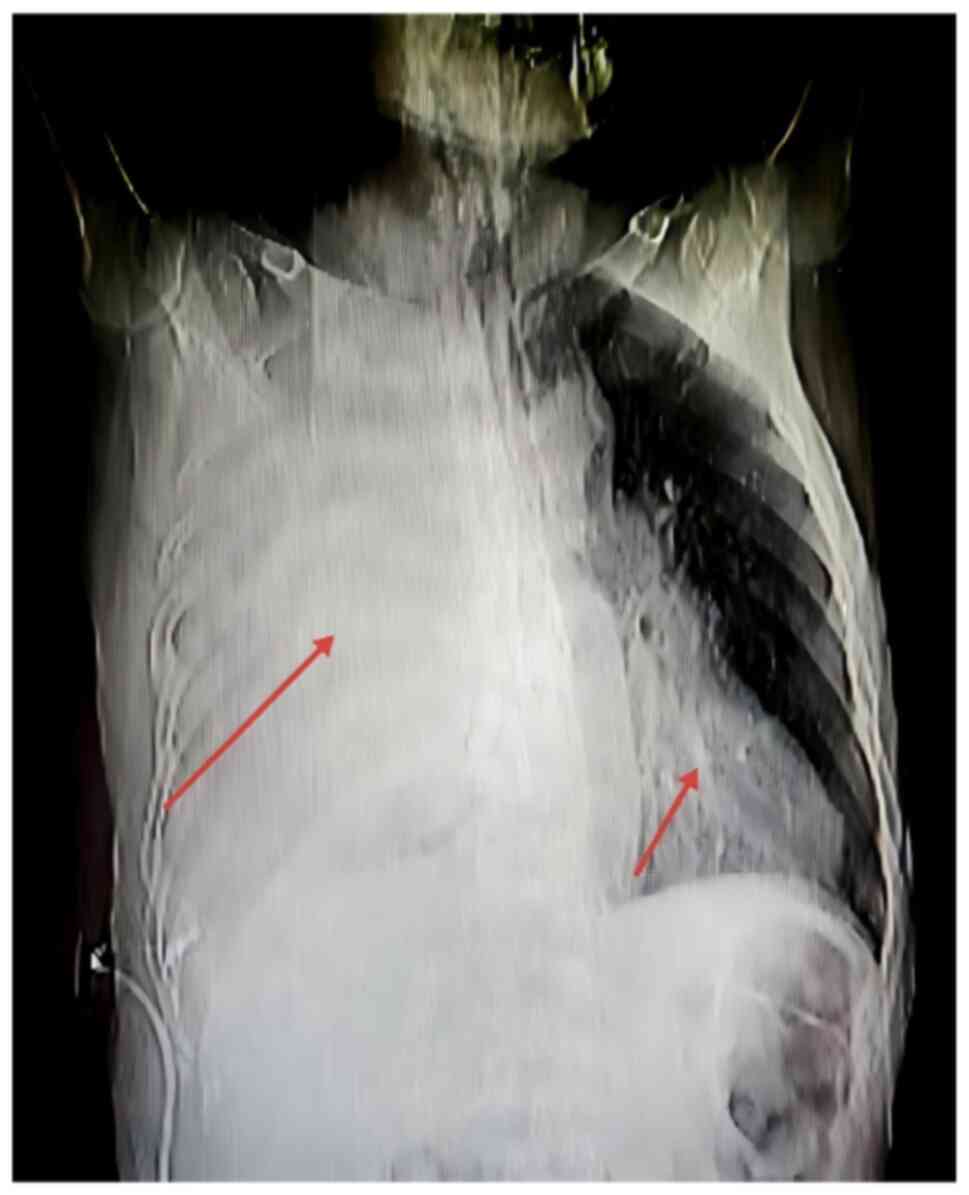

dilation of the common bile duct. Additionally, chest radiography

(Fig. 2) corroborated extensive

pathological involvement of the right lung with possible tumor

infiltration affecting the right lower lobe and extending into the

left lung, collectively manifesting as a generalized ‘white lung’

appearance.

Cytological examination revealed a small number of

atypical cells (data not shown) and the possibility of a malignant

tumor could not be ruled out. To further evaluate the patient's

condition, a thoracentesis was performed, which yielded 350 ml of

pleural effusion. Subsequently, a CT-guided percutaneous lung

biopsy was performed, resulting in the collection of three tissue

specimens. Laboratory assessments revealed elevated levels of tumor

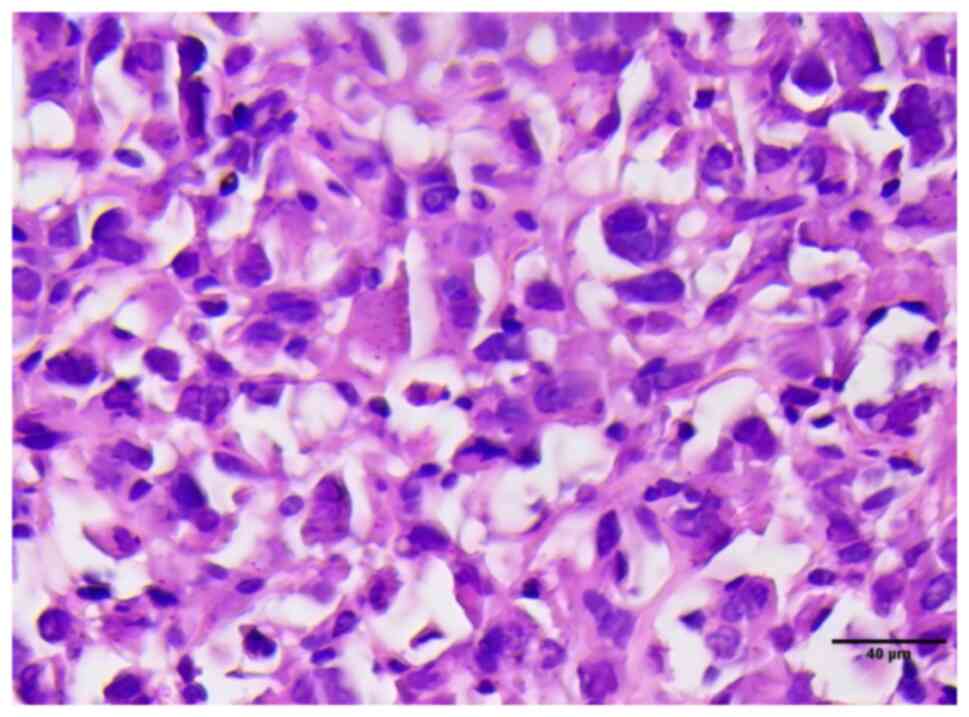

markers, notably Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The HE staining

results showed that the cell nuclei were deeply stained, had

abnormal shapes, and there were numerous instances of cell division

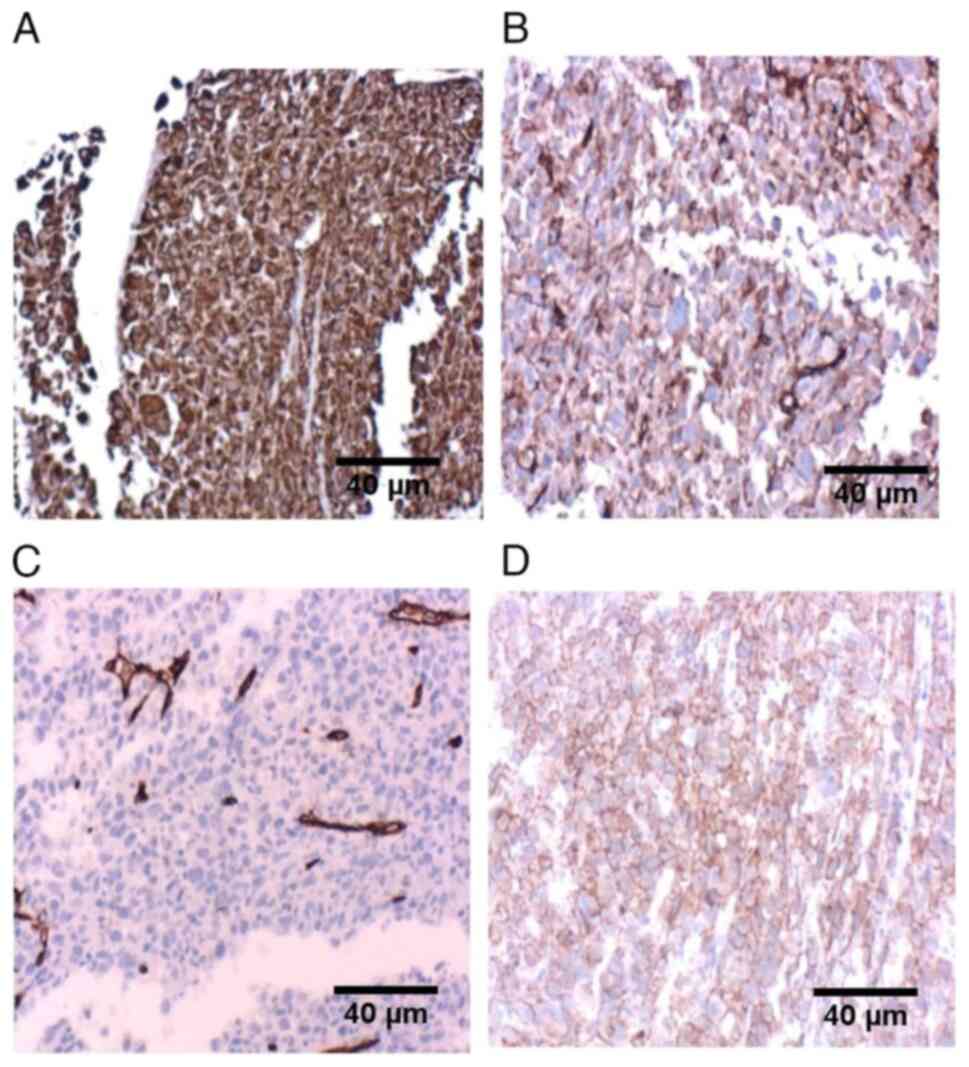

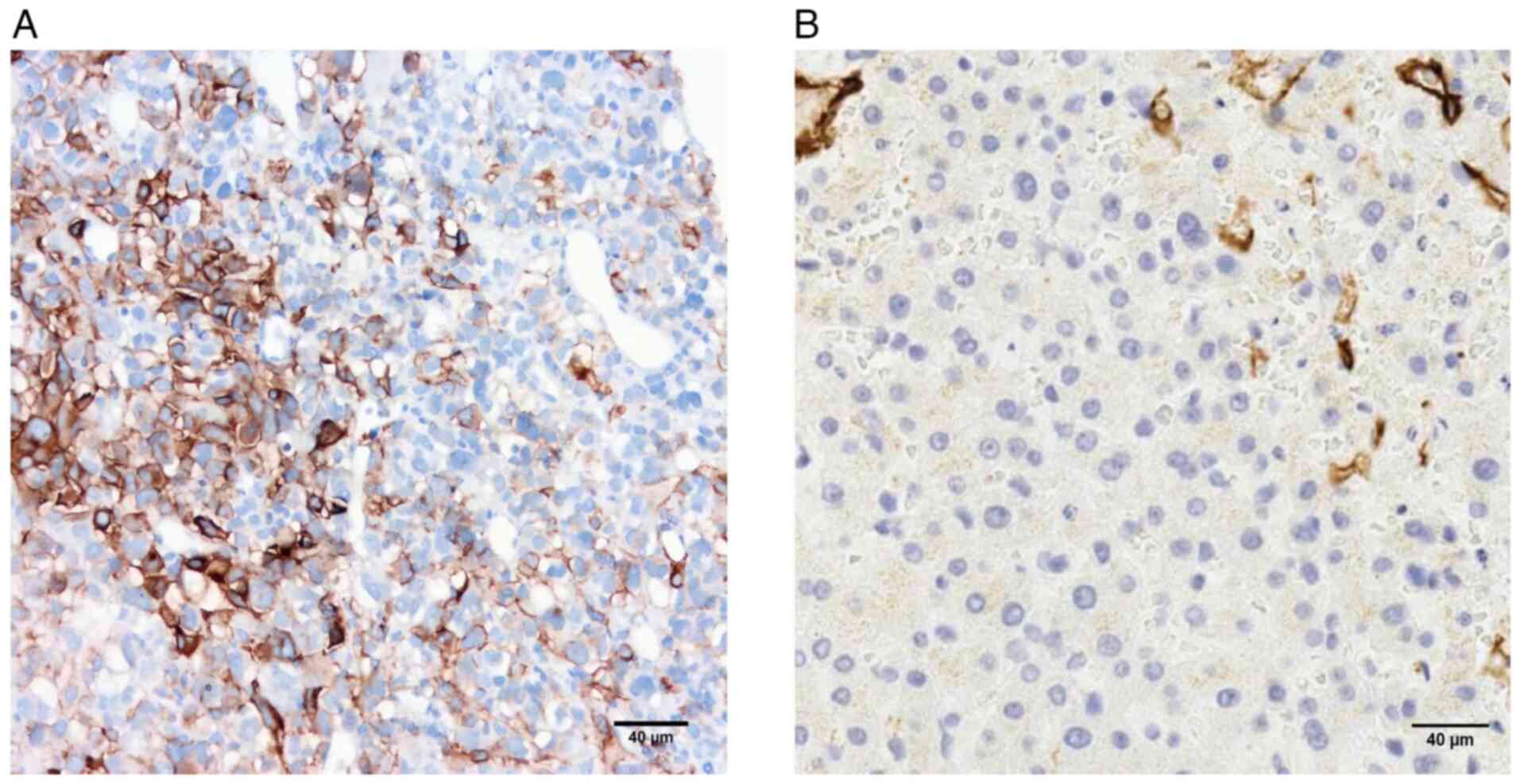

(Fig. 3). IHC examination indicated

positive expression of vimentin (Fig.

4A), CD31 (Fig. 4B), CD34

(Fig. 4C), and the ETS-related gene

(Fig. 4D), collectively suggesting

angiosarcoma. IHC analysis revealed positivity for both PD-L1 and

VIII-RA (Fig. 5). Based on the

ninth edition of the TNM classification system established by the

International Union Against Cancer (13), the patient was diagnosed with

pulmonary vascular sarcoma, staged as T2N1M1, corresponding to

overall clinical stage IV. This stage is characterized by a primary

tumor measuring between 5 and 10 cm in maximum diameter (T2), with

involvement of regional lymph nodes (N1) and the presence of

distant metastases (M1).

The patient's clinical condition progressively

deteriorated, ultimately precluding systemic chemotherapy.

Symptomatic treatment encompassed high-flow oxygen therapy,

hemostatic interventions and analgesic management. At the family's

request, genetic testing was performed to assess the feasibility of

targeted therapeutic options. Owing to the limited tissue obtained

from the initial lung puncture, a subsequent CT-guided percutaneous

lung biopsy was performed, yielding six specimens for comprehensive

multigene analysis pertinent to solid tumors. While awaiting

multigene test results, the patient demonstrated gradual

leukocytosis, suggestive of potential bone marrow involvement.

Concurrently, the patient's level of consciousness declined and

arterial blood gas analysis indicated hypercapnia. Nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs were administered for pain control and

local radiotherapy was provided. Regrettably, owing to the rapid

disease progression, the patient died before targeted therapy could

be initiated.

At three days after the patient's death, four

potential therapeutic target genes were identified within the

pan-cancer 1,238-gene panel, each of which exhibited an

amplification mutation. Specifically, CD274 demonstrated a

mutation abundance of 6.3-fold and atezolizumab was identified as a

potentially effective therapeutic agent. Kinase insert domain

receptor (KDR) showed a mutation abundance of 2.2-fold, with

regorafenib, sunitinib and sorafenib being potentially beneficial

drugs. Similarly, KIT exhibited a 2.2-fold mutation

abundance, with pazopanib as a potential treatment option. Lastly,

platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) exhibited

a 2.2-fold mutation abundance, with pazopanib and sunitinib

considered potential therapeutic agents.

Discussion

The mechanisms underlying angiosarcoma have remained

to be fully elucidated. Patients who have undergone breast cancer

surgery and radiotherapy are prone to developing angiosarcoma of

the skin and chest (14). Pulmonary

angiosarcomas are even rarer, with most reports being case reports.

In the present case, the patient had been smoking for a long time,

similar to a previously reported case (15). However, the patient also had a

history of hypertension, cerebral infarction and coronary artery

disease. Currently, there is no direct evidence that pulmonary

angiosarcoma is associated with these factors, to the best of our

knowledge.

The clinical manifestations of pulmonary

angiosarcomas are often nonspecific, making them difficult to

detect. The most common clinical manifestation is hemoptysis, along

with symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain and cough (5,16).

Patients often present with systemic manifestations such as weight

loss, fatigue and fever. In the present case, the patient presented

with a cough and hemoptysis. After examination, a mass was found in

the right lung and the pathological diagnosis was pulmonary

angiosarcoma. It can be seen that in clinical practice, common

respiratory symptoms, such as hemoptysis, chest pain and shortness

of breath, should be taken seriously and should not be readily

dismissed, so as not to overlook the diagnosis of pulmonary

angiosarcoma.

Currently, imaging examinations for pulmonary

angiosarcoma are mainly based on chest radiography and CT. In the

case reported by Yu et al (17), the main imaging manifestations were

multiple nodules, ground-glass patches and diffuse infiltration.

Imaging examination of this patient suggested a mass in the right

lung, which is consistent with previous reports. However, the

imaging features of pulmonary angiosarcoma lack specificity and are

often similar to those of other lesions, such as metastatic tumors

(including pulmonary tuberculosis), making differential diagnosis

difficult. Therefore, imaging data may provide imited reference

value for the diagnosis of this disease (5,17).

In the current clinical diagnosis of pulmonary

angiosarcoma, immunomarkers, such as CD34, CD31, VIII-RA, Fli-1

proto-oncogene and vimentin, are commonly used (3–6,17), all

of which are specific markers for endothelial cells of vascular

origin. Certain studies have reported that VIII-RA and CD31 are the

most specific marker antibodies for angiosarcoma, particularly in

poorly differentiated tumors (18–23).

In the present case, the IHC markers CD34, CD31 and vimentin were

all positive, which may have helped confirm the diagnosis.

The Italian Sarcoma Organization and Japanese

Sarcoma Association published consensus documents and guidelines

for angiosarcoma treatment (24,25).

The treatment plans typically include surgery, radiotherapy and

chemotherapy. For localized angiosarcomas, extensive resection is

the standard treatment method and a clean surgical margin is one of

the factors affecting prognosis (26). Surgery is the primary treatment for

localized disease; however, the postoperative recurrence rate is

high. Bartakke and Saez de Ibarra Sanchez (27) reported a case of pulmonary

angiosarcoma that was successfully treated surgically. Adjuvant

radiotherapy after radical surgery has been proven to be an

effective combination treatment for angiosarcoma; however, no

formal observational trial has demonstrated that radiotherapy alone

is effective. Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for patients

who have lost the opportunity to undergo surgery. The main

chemotherapeutic drugs include taxanes, doxorubicin, liposomal

doxorubicin and ifosfamide. Among these, taxanes are considered

effective agents for the clinical treatment of angiosarcoma and are

often used as first- or second-line treatments for metastatic

disease (25,28,29).

In addition, recombinant IL-2 may have a positive effect on

angiosarcoma treatment (30). In

recent years, new approaches have provided novel strategies for the

treatment of angiosarcoma. Angiosarcoma cells with high VEGFR-2

expression are sensitive to anti-VEGFR antibody drugs, such as

sorafenib and sunitinib (31). A

similar drug, pazopanib, has entered clinical trials for cutaneous

angiosarcoma as a second-line standard therapy, but its overall

efficacy has not met the primary endpoint (32). Further trials are required before

these drugs can be adopted clinically. As shown in Table I, there are various current

treatment methods; however, most patients present with multiple

metastases at diagnosis, resulting in a poor prognosis. In the

present case, after diagnosis, the patient had multiple metastases

to the mediastinum, right pulmonary artery trunk, mediastinal lymph

nodes, right pleura and right third rib and eventually died. The

patient therefore missed the opportunity to receive targeted

therapy.

| Table I.Summary of reported cases of

pulmonary angiosarcoma. |

Table I.

Summary of reported cases of

pulmonary angiosarcoma.

| Patient

details | Clinical

presentation | Diagnostic

basis | Treatment | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 71-year-old

male | Recurrent cough,

expectoration, hemoptysis, chest pain, dyspnea | Large right lung

mass, pleural effusion, IHC (CD34+, CD31+,

vimentin+, Ki67 60%) | Symptomatic

support, genetic testing identified actionable mutations (CD274,

KDR, KIT, PDGF) | Died prior to

targeted therapy initiation | Present case

report |

| 70-year-old

male | Hemoptysis, weight

loss, general weakness and mild recurrent epistaxis | Pulmonary nodules,

hemorrhagic pleural effusion, pleural cavity masses, IHC

(CD31+, vimentin+) | Discharged from the

hospital and referred to the tumor center to consider any further

treatment options | Died five days

after discharge | (3) |

| 11 cases | Chest pain, cough,

breathing difficulties, hemoptysis | All patients were

eventually diagnosed by pathology, and the positive rates of CD31

and CD34 were as high as 60% | Three cases

received surgical treatment and the remaining eight patients

received chemotherapy or immunotherapy | Surgical treatment

OS: 23 months; Non-surgical treatment OS: 9.7 months | (4) |

| 34-year-old

woman | Cough, hemoptysis

and breathing difficulties | Multiple small

nodules and ground-glass patches in both lungs; Pleural bloody

effusion; IHC (CD34+, CD31+, Ki67 70%,

ERG+, FLI-1+) | Hypovolemic shock

occurred after thoracoscopic lung biopsy and was transferred to the

ICU for resuscitation | Died of respiratory

failure 19 days later | (6) |

| 72-year-old

male | Shortness of breath

worsens | Impaired right

ventricular function, pulmonary artery mass | Endarterectomy for

pulmonary thrombosis, paclitaxel chemotherapy | Died of acute

pulmonary thrombosis after 4 months | (16) |

Most literature reports cases of pulmonary vascular

sarcoma (4,5,33), as

well as related studies (34,35).

However, most of these articles focused on the clinical symptoms,

diagnostic markers and conventional treatments of pulmonary

vascular sarcoma, while in the present study, gene sequencing was

conducted, thus paying more attention to gene mutations and related

targeted therapies.

Regarding gene-targeted therapy, an angiosarcoma

research project conducted by Painter et al (36) indicated that anti-PD-1 therapy may

be an effective approach for head and neck, face and scalp

angiosarcoma. Another study has shown that PD-L1 is positively

expressed in 29% of angiosarcomas (37). PD-L1 is highly expressed in

angiosarcoma (38–41). Research conducted by Kösemehmetoğlu

et al (41) indicated that a

higher tumor grade and a worse patient prognosis are associated

with a higher expression of PD-L1 in soft tissue sarcomas.

Atezolizumab can be used as an antibody targeting CD274 for cancer

treatment (42). However, the

therapeutic effects of anti-PD-1 drugs in primary pulmonary

vascular sarcomas have not yet been confirmed. KDR mutations

are present in pancreatic, cardiac, breast and renal angiosarcomas

(43–46). In angiosarcoma, the incidence of KDR

mutations is ~7–10% (47).

Amplification of KDR is associated with activation of mTOR

and p38, as well as infiltration of tumor cells caused by VEGF

(48). The clinical trials

NCT02693535, NCT03297606 and NCT02029001 have reported that

regorafenib, sunitinib and sorafenib, respectively, can target and

treat tumors caused by KDR amplification. Relatively few

studies have reported significant mutation characteristics of

KIT and PDGFRA in angiosarcoma (49–54).

Research conducted by Xu et al (55) reported that KIT mutations are

widespread in angiosarcoma, occurring in ~25% of cases. Because

PDGFRA mutations are relatively rare in angiosarcoma, there

are no published studies specifically reporting the incidence of

these mutations, to the best of our knowledge. However, studies on

the chromosome 4q11-q13.1 region (containing KIT, PDGFRA and

VEGFR2) and the 4q12 amp region (containing KIT,

PDGFRA and KDR) have shown that PDGFRA mutations

are present in angiosarcomas (54,56),

with 4q12 amp being detected in 4.8% of angiosarcomas (56). Since primary pulmonary angiosarcoma

is relatively rare, KIT and PDGFRA mutations are more

often found in other angiosarcomas, whereas pulmonary angiosarcoma

cases are rarely reported. The clinical trial NCT02029001

demonstrated that pazopanib may be effective in treating advanced

malignant solid tumors caused by KIT amplification. In

addition, apatinib can be used to treat angiosarcomas caused by

KIT and KDR gene amplification (50). Pazopanib may be applicable to

gastrointestinal stromal tumors (57) and the US Food and Drug

Administration has approved its use for soft tissue sarcomas.

Sunitinib is used for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal

tumors and renal cell carcinomas (58,59).

It may also inhibit the activity of various receptor tyrosine

kinases, including PDGFR (38). The

clinical trial NCT03297606 indicated that sunitinib may be

applicable to various tumors caused by PDGFRA amplification.

Because of the rarity and nonspecific clinical

symptoms of primary pulmonary angiosarcoma, early identification

and treatment remain important challenges. This case highlights the

diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties associated with primary

pulmonary angiosarcoma and underscores the potential role of

genomic findings in guiding future treatment strategies.

In conclusion, this study reports the case of

primary pulmonary vascular sarcoma in a 71-year-old man with

hemoptysis, chest pain and shortness of breath. Immunological

marker testing confirmed the diagnosis of primary pulmonary

vascular sarcoma. Genetic testing revealed mutations that may be

targeted for therapy. However, the rapid progression of the tumor

hindered treatment implementation, highlighting the need for early

diagnosis and personalized treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequence reads were uploaded to the SRA

database, with the BioProject ID PRJNA1344604. They are available

for download from the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP636518&o=acc_s%3Aa.

Authors' contributions

YZ conceived and designed the study, performed the

experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. CG

collected clinical data, performed pathological analyses and

contributed to manuscript preparation. YZ and CG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present research followed the Declaration of

Helsinki and was approved by the Banan Hospitals Ethics Committee

(Chongqing, China; approval no. BNLLKY2025074). As the patient's

condition deteriorated and he lost consciousness, written informed

consent was obtained from the patient's daughter for the patient to

undergo imaging examinations, pathological examinations and genetic

testing.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient's daughter for the publication of this manuscript and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, Hughes D and

Woll PJ: Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 11:983–991. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Khalid K, Khan A, Lomiguen CM and Chin J:

Clinical detection of primary pulmonary angiosarcoma. Cureus.

13:e170592021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rana MK, Rahman O and O'Brien A: Primary

pulmonary angiosarcoma. BMJ Case Rep. 14:e2445782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ren Y, Zhu M, Liu Y, Diao X and Zhang Y:

Primary pulmonary angiosarcoma: Three case reports and literature

review. Thorac Cancer. 7:607–613. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Luan T, Hao J, Gu Y, He P, Li Y, Wang L,

Deng H, Guan W, Lin X, Xie X, et al: A clinical analysis and

literature review of eleven cases with primary pulmonary

angiosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 24:15972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang Y, Huang X, Peng C, Wang Y, Wu Q, Wu

Z, Shao H and Wang W: Primary pulmonary epithelioid angiosarcoma: A

case report and literature review. J Cancer Res Ther. 14

(Suppl):S533–S535. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tang X, Zhu J, Zhu F, Tu H, Deng A, Lu J,

Yang M, Dai L, Huang K and Zhang L: Case report: Primary pulmonary

angiosarcoma with brain metastasis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol.

9:8038682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Basiri R, Ziaei Moghaddam A, Rikhtegar A

and Jafarian AH: Primary pulmonary angiosarcoma found incidentally

in a complicated patient: A rare case report. Clin Respir J.

18:e138182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu Y, Ma X, Chen J, Wang H and Yu Z:

Nontuberculous mycobacteria by metagenomic next-generation

sequencing: Three cases reports and literature review. Front Public

Health. 10:9722802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gu W, Miller S and Chiu CY: Clinical

metagenomic next-generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu

Rev Pathol. 14:319–338. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bejaoui S, Nielsen SH, Rasmussen A, Coia

JE, Andersen DT, Pedersen TB, Møller MV, Kusk Nielsen MT, Frees D

and Persson S: Comparison of Illumina and Oxford Nanopore

sequencing data quality for Clostridioides difficile genome

analysis and their application for epidemiological surveillance.

BMC Genomics. 26:922025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A,

Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly

M and DePristo MA: The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce

framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome

Res. 20:1297–1303. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang B, Fang WT and Zhong H: Introduction

to the 9th edition of TNM classification for lung

cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 46:206–210. 2024.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bonito FJP, de Almeida Cerejeira D,

Dahlstedt-Ferreira C, Oliveira Coelho H and Rosas R:

Radiation-induced angiosarcoma of the breast: A review. Breast J.

26:458–463. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Piechuta A, Przybyłowski T, Szołkowska M

and Krenke R: Hemoptysis in a patient with multifocal primary

pulmonary angiosarcoma. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 84:283–289.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lim R, Harper L and Swiston J: Clinical

manifestations and diagnostic methods in pulmonary angiosarcoma:

Protocol for a scoping review. Syst Rev. 6:1362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yu M, Huang W, Wang Y, Wang G, Wang L, Tao

W, Faiz SA, Ng FH and Li H: Pulmonary angiosarcoma presenting with

diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: A case report. Ann Transl Med.

9:742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Studer LL and Selby DM: Hepatic

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 142:263–267.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Giuffrida MA, Bacon NJ and Kamstock DA:

Use of routine histopathology and factor VIII-related antigen/von

Willebrand factor immunohistochemistry to differentiate primary

hemangiosarcoma of bone from telangiectatic osteosarcoma in 54

dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 15:1232–1239. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Silwal A, B R S, Rehman S, Daing A,

Gopagoni R, Alyas Akram M, Saeed A, Sadiq KO, Farrukh AM and

Harikrishna A: Bladder angiosarcoma: A systematic literature review

and survival analysis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 38:305–312.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kapagan T, Bulut N, Erdem GU, Yıldırım S,

Erdem ZB and Sahin H: Synchronous double Primary Angiosarcoma

originating from the stomach and rectum: A case report and a

literature review. Arch Iran Med. 27:168–173. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Salehi M, Rehman S, Davis S and Jafari HR:

Angiosarcoma of gallbladder, a literature review. J Med Case Rep.

18:622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ma XM, Yang BS, Yang Y, Wu GZ, Li YW, Yu

X, Ma XL, Wang YP, Hou XD and Guo QH: Small intestinal angiosarcoma

on clinical presentation, diagnosis, management and prognosis: A

case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol.

29:561–578. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Palassini E, Baldi GG, Sulfaro S,

Barisella M, Bianchi G, Campanacci D, Fiore M, Gambarotti M,

Gennaro M, Morosi C, et al: Clinical recommendations for treatment

of localized angiosarcoma: A consensus paper by the Italian Sarcoma

Group. Cancer Treat Rev. 126:1027222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fujimura T, Maekawa T, Kato H, Ito T,

Matsushita S, Yoshino K, Fujisawa Y, Ishizuki S, Segawa K, Yamamoto

J, et al: Treatment for taxane-resistant cutaneous angiosarcoma: A

multicenter study of 50 Japanese cases. J Dermatol. 50:912–916.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lahat G, Dhuka AR, Hallevi H, Xiao L, Zou

C, Smith KD, Phung TL, Pollock RE, Benjamin R, Hunt KK, et al:

Angiosarcoma: Clinical and molecular insights. Ann Surg.

251:1098–1106. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bartakke AA and Saez de Ibarra Sanchez JI:

Successful perioperative management of a primary pulmonary arterial

angiosarcoma: Case report. Braz J Anesthesiol.

74:7441862024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cao J, Wang J, He C and Fang M:

Angiosarcoma: A review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J

Cancer Res. 9:2303–2313. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ito T, Uchi H, Nakahara T, Tsuji G, Oda Y,

Hagihara A and Furue M: Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and

face: A single-center analysis of treatment outcomes in 43 patients

in Japan. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 142:1387–1394. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Noguchi G, Ota J, Ishigaki H, Onuki T,

Kato Y and Moriyama M: A case of retroperitoneal angiosarcoma

effectively treated with recombinant interleukin-2. Nihon Hinyokika

Gakkai Zasshi. 103:697–703. 2012.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Park MS, Ravi V and Araujo DM: Inhibiting

the VEGF-VEGFR pathway in angiosarcoma, epithelioid

hemangioendothelioma, and hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous

tumor. Curr Opin Oncol. 22:351–355. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jones RL, Ravi V, Brohl AS, Chawla S,

Ganjoo KN, Italiano A, Attia S, Burgess MA, Thornton K, Cranmer LD,

et al: Efficacy and safety of TRC105 Plus Pazopanib vs Pazopanib

alone for treatment of patients with advanced angiosarcoma: A

randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 8:740–747. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Edemskiy A, Vasiltseva O, Kliver E,

Novikova N, Sirota D and Chernyavskiy A: Surgical treatment of

pulmonary artery Angiosarcoma-a ten-year experience. Braz J

Cardiovasc Surg. 40:e202304412025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lin Y, Yu H, Wang C and Zhang D: Primary

pulmonary angiosarcoma mimicking diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage: A

case report. Oncol Lett. 25:2112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yu L, Sun Y, Wang M, Yuan L, Wang Q and

Qian X: Primary pulmonary epithelioid angiosarcoma with thyroid

tumor history: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med.

24:4712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Painter CA, Jain E, Tomson BN, Dunphy M,

Stoddard RE, Thomas BS, Damon AL, Shah S, Kim D, Gómez Tejeda

Zañudo J, et al: The angiosarcoma project: Enabling genomic and

clinical discoveries in a rare cancer through patient-partnered

research. Nat Med. 26:181–187. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Vargas AC, Maclean FM, Sioson L, Tran D,

Bonar F, Mahar A, Cheah AL, Russell P, Grimison P, Richardson L and

Gill AJ: Prevalence of PD-L1 expression in matched recurrent and/or

metastatic sarcoma samples and in a range of selected sarcomas

subtypes. PLoS One. 15:e02225512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jin J, Xie Y, Zhang JS, Wang JQ, Dai SJ,

He WF, Li SY, Ashby CR Jr, Chen ZS and He Q: Sunitinib resistance

in renal cell carcinoma: From molecular mechanisms to predictive

biomarkers. Drug Resist Updat. 67:1009292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lee AQ, Hao C, Pan M, Ganjoo KN and Bui

NQ: Histologic and immunologic factors associated with response to

immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res.

31:678–684. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Googe PB, Flores K, Jenkins F, Merritt B,

Moschos SJ and Grilley-Olson JE: Immune Checkpoint markers in

superficial angiosarcomas: PD-L1, PD-1, CD8, LAG-3, and

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Am J Dermatopathol. 43:556–559.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kösemehmetoğlu K, Özoğul E, Babaoğlu B,

Tezel GG and Gedikoğlu G: Programmed death Ligand 1 (PD-L1)

expression in malignant mesenchymal tumors. Turk Patoloji Derg.

1:192–197. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yi M, Zheng X, Niu M, Zhu S, Ge H and Wu

K: Combination strategies with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: Current

advances and future directions. Mol Cancer. 21:282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Whitlock RS, Ebare K, Cheng LS, Fishman

DS, Mills JL, Nguyen HN, Nuchtern JG, Ruan W, Smith VE, Patel KA,

et al: Angiosarcoma of the pancreas in a pediatric patient with an

activating KDR-internal tandem duplication: A case report and

review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 44:e751–e755.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Odintsov I, Papke DJ, George S, Padera RF,

Hornick JL and Siegmund SE: Genomic profiling of cardiac

angiosarcoma reveals novel targetable KDR variants, recurrent MED12

mutations, and a high burden of Germline POT1 alterations. Clin

Cancer Res. 31:1091–1102. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Omiyale AO: Primary vascular tumours of

the kidney. World J Clin Oncol. 12:1157–1168. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Beca F, Krings G, Chen YY, Hosfield EM,

Vohra P, Sibley RK, Troxell ML, West RB, Allison KH and Bean GR:

Primary mammary angiosarcomas harbor frequent mutations in KDR and

PIK3CA and show evidence of distinct pathogenesis. Mod Pathol.

33:1518–1526. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Torrence D and Antonescu CR: The genetics

of vascular tumours: An update. Histopathology. 80:19–32. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Nilsson MB, Giri U, Gudikote J, Tang X, Lu

W, Tran H, Fan Y, Koo A, Diao L, Tong P, et al: KDR amplification

is associated with VEGF-induced activation of the mTOR and invasion

pathways but does not predict clinical benefit to the VEGFR TKI

Vandetanib. Clin Cancer Res. 22:1940–1950. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Styring E, Seinen J, Dominguez-Valentin M,

Domanski HA, Jönsson M, von Steyern FV, Hoekstra HJ, Suurmeijer AJ

and Nilbert M: Key roles for MYC, KIT and RET signaling in

secondary angiosarcomas. Br J Cancer. 111:407–412. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yang L, Liu L, Han B, Han W and Zhao M:

Apatinib treatment for KIT- and KDR-amplified angiosarcoma: A case

report. BMC Cancer. 18:6182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dickerson EB, Marley K, Edris W, Tyner JW,

Schalk V, Macdonald V, Loriaux M, Druker BJ and Helfand SC:

Imatinib and dasatinib inhibit hemangiosarcoma and implicate

PDGFR-β and Src in tumor growth. Transl Oncol. 6:158–168. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Homsi J and Daud AI: Spectrum of activity

and mechanism of action of VEGF/PDGF inhibitors. Cancer Control.

14:285–294. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Terada T: Angiosarcoma of the oral cavity.

Head Neck Pathol. 5:67–70. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Prenen H, Smeets D, Mazzone M, Lambrechts

D, Sagaert X, Sciot R and Debiec-Rychter M: Phospholipase C gamma 1

(PLCG1) R707Q mutation is counterselected under targeted therapy in

a patient with hepatic angiosarcoma. Oncotarget. 6:36418–34425.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Xu L, Xie X, Shi X, Zhang P, Liu A, Wang J

and Zhang B: Potential application of genomic profiling for the

diagnosis and treatment of patients with sarcoma. Oncol Lett.

21:3532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Disel U, Madison R, Abhishek K, Chung JH,

Trabucco SE, Matos AO, Frampton GM, Albacker LA, Reddy V,

Karadurmus N, et al: The Pan-cancer landscape of coamplification of

the tyrosine kinases KIT, KDR, and PDGFRA. Oncologist. 25:e39–e47.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mir O, Cropet C, Toulmonde M, Cesne AL,

Molimard M, Bompas E, Cassier P, Ray-Coquard I, Rios M, Adenis A,

et al: Pazopanib plus best supportive care versus best supportive

care alone in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours resistant

to imatinib and sunitinib (PAZOGIST): A randomised, multicentre,

open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17:632–641. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Demlová R, Turjap M, Peš O, Kostolanská K

and Juřica J: Therapeutic drug monitoring of sunitinib in

gastrointestinal stromal tumors and metastatic renal cell carcinoma

in adults-a review. Ther Drug Monit. 42:20–32. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Dufies M, Giuliano S, Viotti J,

Borchiellini D, Cooley LS, Ambrosetti D, Guyot M, Ndiaye PD, Parola

J, Claren A, et al: CXCL7 is a predictive marker of sunitinib

efficacy in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Br J Cancer.

117:947–953. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|