Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common malignant tumor and

the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1). It is estimated that there are 2.2

million novel diagnoses of lung cancer each year, as well as 1.79

million mortalities (2). Lung

cancer poses a severe threat to human health, and its diagnosis and

treatment have become a key focus in oncological research. However,

due to the insidious early symptoms of lung cancer, ~75% patient

are diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease, missing the

optimal treatment window, which results in a continuous increase in

the mortality rates associated with lung cancer (3,4).

Therefore, early diagnosis of lung cancer is key to ensuring timely

treatment and improving survival rates.

Early lung cancer often presents as pulmonary

nodules on imaging (5). Therefore,

recognizing malignant pulmonary nodules is key to the early

diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, as well as to reduce lung

cancer-related mortality. Low-dose CT is an effective method for

the detection of malignant pulmonary nodules (6), but it suffers from a high

false-positive rate (7). Positron

emission tomography has a certain accuracy in differentiating

between benign and malignant lung nodules, but it carries a high

risk of false-negatives or false-positives (8,9). Lung

tissue biopsy is the standard for lung cancer diagnosis; however,

it is an invasive procedure that can lead to complications and has

high costs (10). Non-invasive

testing methods, such as circulating tumor cells and DNA, have

demonstrated certain potential in identifying malignant pulmonary

nodules, but they suffer from low capture rates and sensitivity

(4,11). Tumor markers such as neuron-specific

enolase, squamous cell carcinoma antigen and carcinoembryonic

antigen can provide real-time assessments of tumor status and serve

as an adjunct in the diagnosis of lung cancer, but they lack

sensitivity and specificity (3,12).

Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify a simple,

non-invasive or minimally invasive, reproducible and highly

sensitive method to identify diagnostic biomarkers with high

sensitivity and specificity, thereby enabling the early

identification of malignant pulmonary nodules.

Metabolomics is an emerging high-throughput

technology used to detect, identify and quantify metabolites in

biological samples. It can directly exhibit changes within seconds

or minutes from an event, demonstrating high sensitivity and

proving its unique value in disease diagnosis and disease

mechanisms (13–15). Non-targeted metabolomics is one of

the techniques in metabolomics that focuses on the comprehensive

analysis of all low molecular weight metabolites. It reveals

metabolic changes associated with diseases and reflects their

metabolic characteristics, thus being utilized to identify

potential biomarkers that provide effective assistance for disease

screening and early diagnosis (15,16).

Furthermore, the biological samples required for metabolomics often

originate from the bodily fluids of the patients, such as blood,

plasma, serum and urine (17),

making sample collection convenient and repeatable, which is

beneficial for routine monitoring.

Metabolic dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer

occurrence and progression (18).

Utilizing non-targeted metabolomics to analyze the metabolic

changes from precancer to cancer helps identify potential

diagnostic biomarkers. For instance, a non-targeted metabolomics

study on hepatocellular carcinoma reported that PG(i-12:0/a-17:0)

and phytosphingosine are potential biomarkers for early

hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis in patients with liver

cirrhosis. Furthermore, norvaline, L-histidinol, N-docosahexaenoyl

γ-aminobutyric acid, inosine and 3-hydroxyoctanoly carnitine

revealed a high potential to distinguish patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis from normal controls

(14). Currently, the main

techniques in metabolomics are nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR),

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid

chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (19). NMR is a rapid, non-destructive and

reproducible technique, but has relatively low sensitivity

(19,20). GC-MS is suitable for the analysis of

samples that are stable and easy to gasify but needs derivatization

and a longer sample preparation time (19,20).

By contrast, LC-MS has a higher sensitivity and wider testing

scope, while avoiding the complex sample pretreatment in GC-MS,

which makes it an increasingly predominant platform in metabolomics

(19–21).

Based on the aforementioned points, in the present

study, plasma samples were collected from three different stages:

Patients with lung cancer, those with pulmonary nodules and healthy

individuals. By analyzing the metabolic changes using LC-MS, the

present study aimed to identify differential metabolites, identify

potential diagnostic biomarkers for lung cancer and reveal abnormal

metabolic pathways, with the intention of providing novel insights

and approaches for the early diagnosis of lung cancer, as well as

its pathological mechanisms in the future.

Patients and methods

Study participants

A total of 68 participants from Dongzhimen Hospital

of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (Beijing, China) were

enrolled between April 2023 and May 2024, including 20 patients

with lung cancer (lung cancer group), 28 patients with pulmonary

nodules (pulmonary nodule group) and 20 healthy individuals

(healthy group). Patients with lung cancer and pulmonary nodules

were recruited using a simple random sampling method based on

disease type, while healthy individuals were recruited using a

matching method based on age and sex. The present study was

reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongzhimen

Hospital of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (approval no.

2022DZMEC-312-02). All methods were conducted in accordance with

relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants signed

informed consent forms. The inclusion criteria for lung cancer were

as follows: i) The patients were confirmed to have lung

adenocarcinoma through histopathological examination; ii) there

were no restrictions on the sex of the patients and the age range

was 18–90 years; iii) the patients had not received any treatments

such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to enrollment

in the present study. The inclusion criteria for pulmonary nodules

were as follows: i) The patient had imaging findings of round or

irregularly shaped pulmonary nodules with a maximum diameter of ≤30

mm, which was either solid or subsolid in nature and exhibited

increased radiological density; ii) either a) pathology results

were negative or b) imaging features were benign, Lung Imaging

Reporting and Data System category 2 (22) and they were classified as low-risk

by the chest CT image-assisted system at Dongzhimen Hospital of

Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; iii) there were no

restrictions on the sex of the patients and the age range was 18–90

years; and iv) the patients did not receive any treatment prior to

enrollment in the present study. The healthy individuals were

diagnosed as healthy by physical examination and medical diagnosis.

The exclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: i)

Patients who were in the acute phase of a disease, such as acute

respiratory infection, myocardial infarction, renal insufficiency

or other conditions that could interfere with diagnosis; ii)

patients who had severe primary disease affecting major organs,

such as the heart, lungs, brain, liver, kidney or blood or any

severe conditions impacting their overall survival; iii) patients

who were suffering from psychiatric disorders; and iv) patients who

were diagnosed with other malignant tumors. The baseline

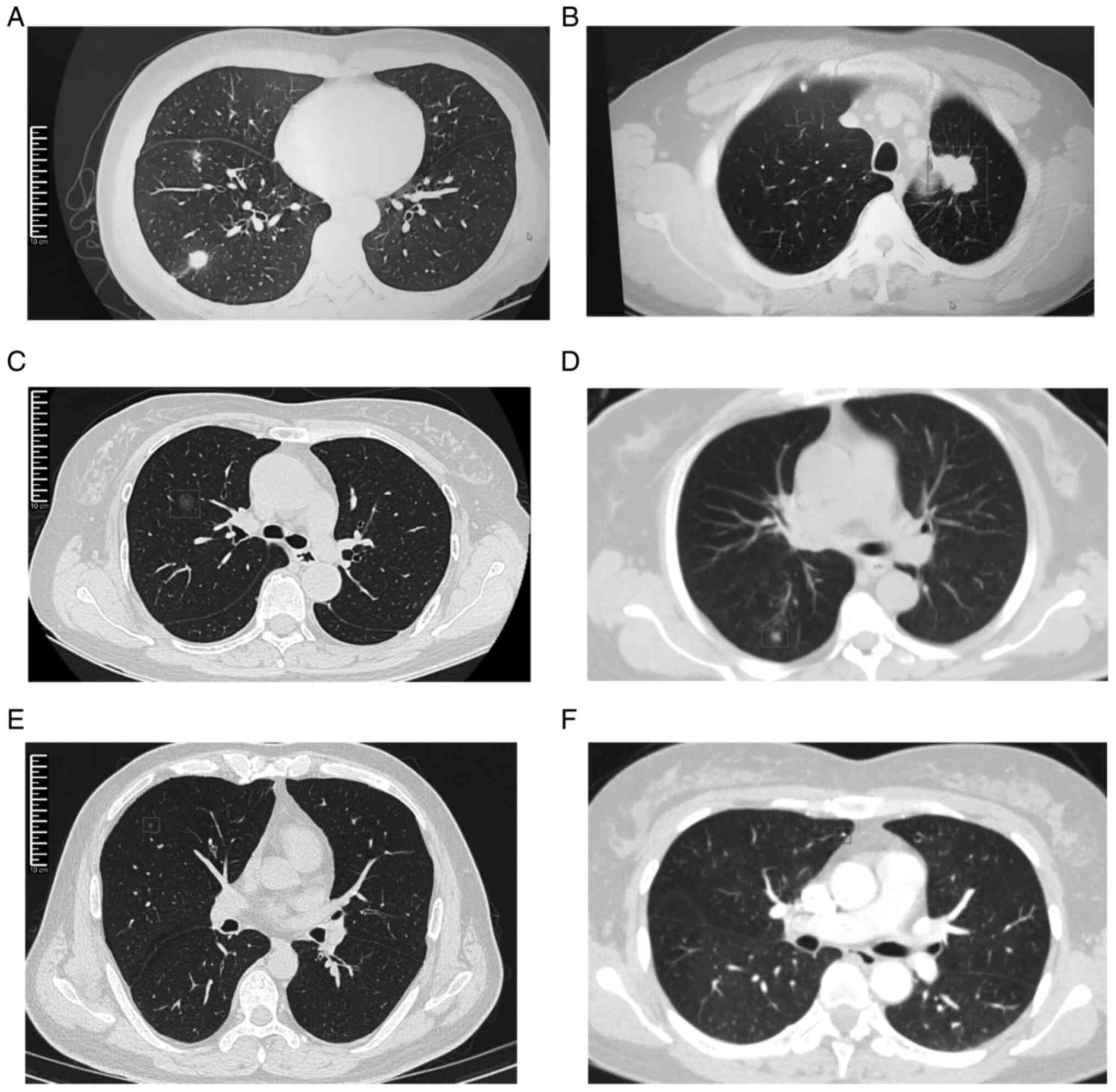

information for all participants is shown in Table I. Examples of chest CT images for

lung cancer and pulmonary nodule groups can be seen in Fig. 1.

| Table I.Baseline information of all

participants. |

Table I.

Baseline information of all

participants.

| Clinical

characteristics | Pulmonary nodules

group (n=28) | Lung cancer group

(n=20) | Healthy group

(n=20) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

| Median

(range) | 65.5 (44–87) | 70.5 (35–82) | 60.5 (48–71) | - |

| Mean ±

SD | 65.68±12.99 | 67.35±12.20 | 60.80±7.24 | 0.062 |

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.277 |

|

Male | 8 (28.6) | 10 (50.0) | 9 (45.0) |

|

|

Female | 20 (71.4) | 10 (50.0) | 11 (55.0) |

|

| Smoking

history |

|

|

| 0.569 |

|

Yes | 6 (21.4) | 7 (35.0) | 6 (30.0) |

|

| No | 22 (78.6) | 13 (65.0) | 14 (70.0) |

|

| Dust exposure

history |

|

|

| >0.999 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 20 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Family history of

tumors |

|

|

| 0.057 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 4 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 16 (80.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Hypertension |

|

|

| 0.055 |

|

Yes | 5 (17.9) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 23 (82.1) | 15 (75.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Type 2

diabetes |

|

|

| 0.061 |

|

Yes | 6 (21.4) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 22 (78.6) | 18 (90.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Hyperuricemia |

|

|

| >0.999 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 20 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Hyperlipidemia |

|

|

| 0.059 |

|

Yes | 6 (21.4) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 22 (78.6) | 15 (75.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Fatty liver |

|

|

| 0.553 |

|

Yes | 2 (7.1) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 26 (92.9) | 18 (90.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Coronary

atherosclerotic heart disease |

|

|

| 0.110 |

|

Yes | 4 (14.3) | 4 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 24 (85.7) | 16 (80.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Heart failure |

|

|

| >0.999 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 20 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Atrial

fibrillation |

|

|

| >0.999 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 19 (95.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Cerebral

infarction |

|

|

| >0.999 |

|

Yes | 1 (3.6) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| No | 27 (96.4) | 19 (95.0) | 20 (100.0) |

|

| Pathological type

(adenocarcinoma) | - | 20 (100.0) | - | - |

Reagents and equipment

The reagents used in the present study mainly

included methanol, formic acid and ammonium acetate (supplementary

material). The instruments used included ultra-high-performance

liquid chromatograph (UHPLC), quadrupole Orbitrap ion trap mass

spectrometer, ultra-pure water system, multi-tube vortex

oscillator, benchtop high-speed refrigerated centrifuge, vacuum

centrifugal concentrator, chromatography columns, 200- and 1,000-µl

pipettes, and pipette tips (Table

SI, Table SII, Table SIII).

Plasma sample collection and

preparation

A 4-ml blood sample was obtained from all of the

participants in the early morning fasting state. The samples were

immediately centrifuged at 1,610 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the

plasma was transferred to a 1.5-ml clean centrifuge tube and stored

at −80°C until analysis. Once all samples were collected,

metabolomics analysis was conducted. The plasma samples were

pretreated as follows: i) The frozen plasma samples were thawed at

4°C for 30–60 min; ii) 100 µl of the plasma sample was precisely

pipetted into a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube and three times the volume

of pre-chilled methanol was added; iii) the mixture was vortexed

for 5 min, allowed to sit on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged at

15,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C; iv) 300 µl of the supernatant was

collected in a centrifuge tube and vacuum-concentrated for 4 h; and

v) the supernatant was re-dissolved in 50 µl of methanol/water

(1:1) and vortexed for 5 min, centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min

at 4°C and the supernatant was then used for analysis.

LC-MS analysis conditions

LC-MS analysis was performed on plasma samples using

a Thermo Scientific Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) interfaced with a heated electrospray

ionization-equipped quadrupole-Orbitrap™ hybrid mass spectrometer.

Chromatographic separation was performed using a Waters™ UPLC high

strength silica T3 column (2.1×100 mm, 1.8 µm) under the following

conditions: i) The mobile phase comprised component a) 0.1% formic

acid and 0.1% aqueous formic acid solution, and component b)

methanol; and ii) the flow rate was maintained at 0.3 ml/min, with

the column temperature set to 40°C and an injection volume of 1 µl

was used (supplementary material).

Mass spectrometry was conducted in both positive and

negative ion modes with the following specific parameters: The ion

source voltage for positive and negative ions were set at 3.8 and

3.2 kV, respectively. The capillary heating temperature was 320°C,

with an auxiliary gas pressure of 10 psi and sheath gas pressure of

30 psi and the collision gas pressure was 1.5 mTorr. All gases

(auxiliary, sheath and collision gas) were nitrogen. The parameters

for the full scan in the first stage were set as follows: A

resolution of 60,000, an automatic gain control (AGC) target of

3×106, a maximum isolation time of 200 msec and a

mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) scan range of 70–1,050. For metabolite

identification, the dd-MS2 scan mode (a data-dependent acquisition

method) was employed using the following parameters: Scanning was

conducted in four segments for m/z ranges of 70–160, 150–400,

390–1,050 and 70–1,050, with a resolution of 60,000, an AGC target

of 3×106, a maximum isolation time of 100 msec and a

maximum of 8 ion fragments to be scanned (dynamic exclusion). The

mass isolation window was set to 1.5 and the collision energies

were 20, 30 and 40 V. The Xcalibur software (version 4.2; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to control the LC-MS system and

to perform data acquisition.

Quality control (QC)

QC samples were prepared for QC purposes. The QC

samples were obtained by taking a fixed volume from all samples,

mixing them uniformly and preparing them in the same manner as

other samples. In the present study, three blank samples were used

to equilibrate the chromatography column, followed by three QC

samples to equilibrate the columns under the same conditions. A QC

sample was inserted after every 8–10 samples to monitor the

stability and reproducibility of the entire LC-MS system, ensuring

the reliability of the data obtained in the present study.

Data analysis

Non-targeted metabolomics data processing

The Compound Discoverer software (version 3.3;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to preprocess data in both

positive and negative ion modes. The steps included importing the

raw data, peak extraction, deconvolution, peak alignment and

filtering or filling in missing values, resulting in an aligned

peak table containing retention times, m/z and peak areas. The

aligned peak table was then imported into open-source software

MetaboAnalyst (version 5.0; http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/), where data filtering

was performed by removing variables with a relative SD >20% in

QC samples. Subsequently, normalization was carried out using the

sum normalization method, followed by log data transformation and

auto-scaling, ultimately producing a normalized table of retention

times, m/z and peak areas. The normalized peak table was then

imported into Simca (version 14.1; Umetrics, Inc.) and GraphPad

Prism statistical analysis software (version 6.02; Dotmatics) for

preliminary statistical analysis.

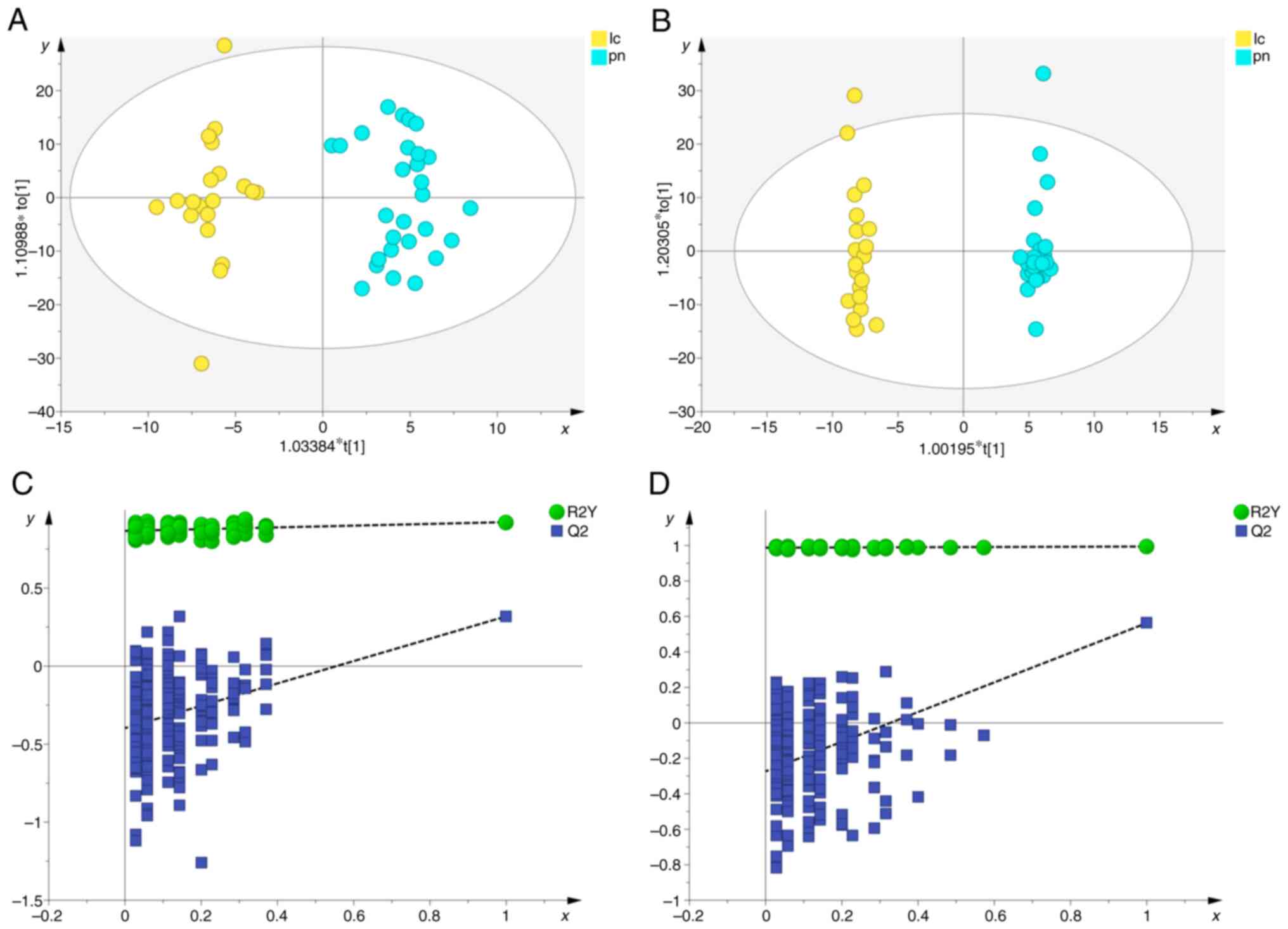

Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal

partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were employed

to reflect overall metabolic differences and intergroup

differences. To validate the accuracy of the OPLS-DA model, a

permutation analysis was conducted with 200 iterations to eliminate

the randomness associated with the supervised learning method. The

quality of the OPLS-DA mode can be explained by R2Y and Q2 values.

The R2Y estimates the goodness of fit of the model that represents

the fraction of explained Y-variation and Q2 estimates the ability

of prediction. Differential metabolites were identified using a

combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. For the

quantitative method, variable importance in the projection (VIP)

values from the OPLS-DA model were used in conjunction with

P-values from unpaired t-tests to identify differential

metabolites, with the criteria set as VIP >1.5 and P<0.05.

For the qualitative method, searches were conducted in the mzCloud

(https://www.mzcloud.org), Human Metabolome

Database (HMDB; http://www.hmdb.ca), ChemSpider

(https://www.chemspider.com), BioCyc

(https://www.biocyc.org) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg) databases. The identified

differential metabolites were then subjected to metabolic pathway

enrichment analysis using the KEGG database, considering pathways

with an impact value of ≥0.01 as significantly altered

pathways.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

(version 25.0; IBM Corp.) and R software (version 4.4.1; Posit

Software, PBC). Categorical data were described by frequency (n)

and percentages (%), while continuous data were expressed as the

mean ± SD. Intergroup comparisons were conducted using SPSS 25.0.

The categorical data analyzed by the χ2 test included

sex and smoking history, while Fisher's exact test was applied to

other categorical data. For continuous data, the age of the

participants deviated from the normal distribution (tested with the

Shapiro-Wilk test); therefore, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis

test with Dunn's multiple post-hoc comparisons test was used to

compare the groups. R version 4.4.1 was used for binary logistic

regression analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve analyses, with the area under the curve (AUC) used to

evaluate their diagnostic effectiveness. The standard for AUC

values were as follows: 0.5<AUC<0.7 indicated low diagnostic

accuracy, 0.7<AUC<0.9 represented a moderate diagnostic

accuracy and AUC >0.9 indicated high diagnostic accuracy.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

General characteristics of the study

participants

In the present study, the lung cancer group included

10 males and 10 females, aged 35–82 years, with an average age of

67.35±12.20 years. The pulmonary nodule group consisted of 8 males

and 20 females, aged 44–87 years, with an average age of

65.68±12.99 years. The healthy group included 9 males and 11

females, aged 48–71 years, with an average age of 60.80±7.24 years.

After comparison, there were no significant differences among the

three groups in terms of age, sex, smoking history, dust exposure

history, family history of tumors, hypertension, type 2 diabetes,

hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, coronary

atherosclerotic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation

and cerebral infarction (P<0.05; Table I).

QC assessment and overall metabolomic

characteristics among the three groups of samples

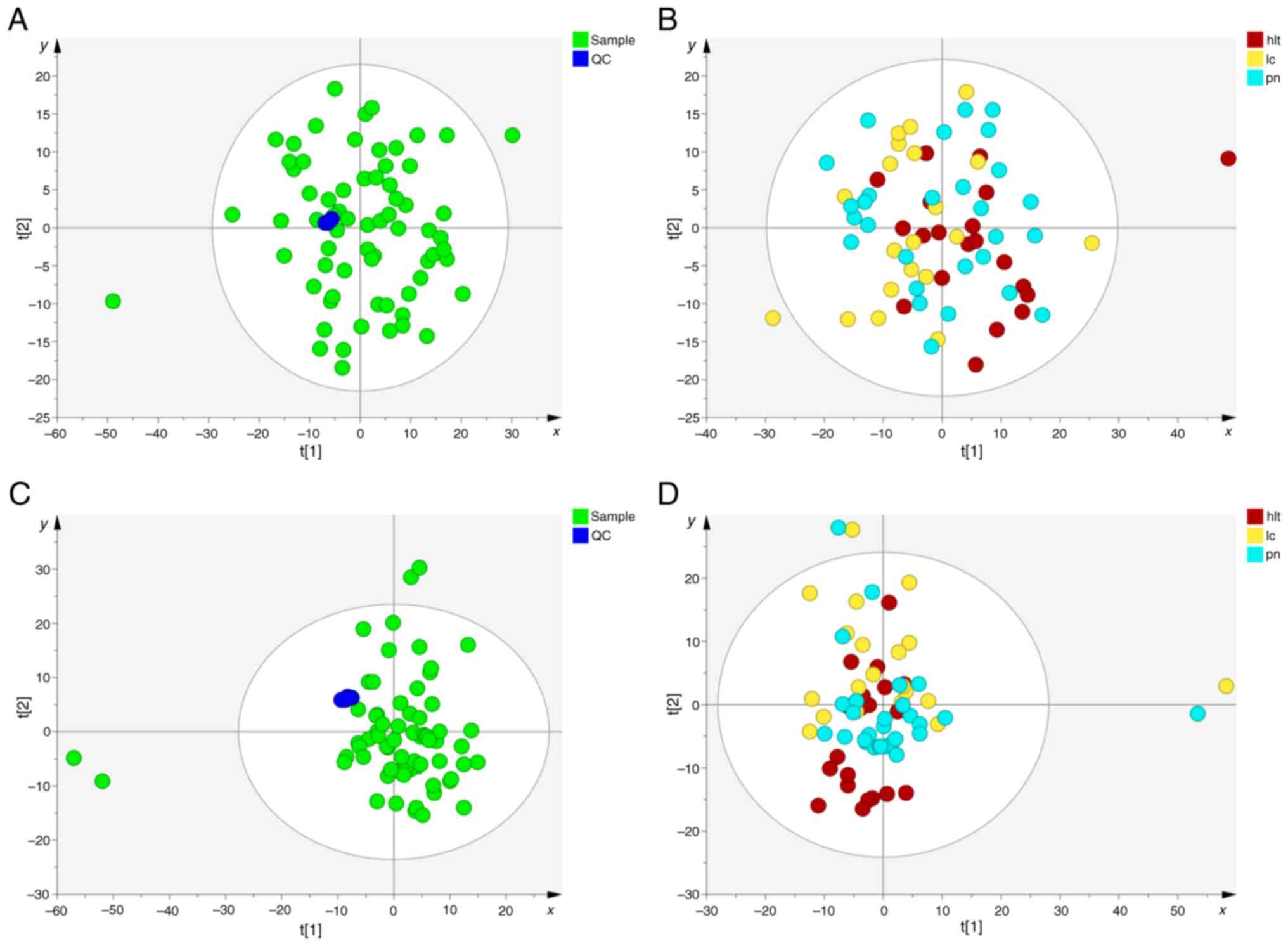

First, PCA analysis was performed to assess the

quality of the QC samples and other clinical samples (Fig. 2). The results demonstrated that all

QC samples clustered together under both positive and negative ion

modes, indicating good system stability and reproducibility

(Fig. 2A and C). Subsequently, PCA

analysis was conducted on samples from the lung cancer, pulmonary

nodule and healthy groups. The PCA score plots indicated a slight

separation trend among the three groups (Fig. 2B and D). Lastly, to further

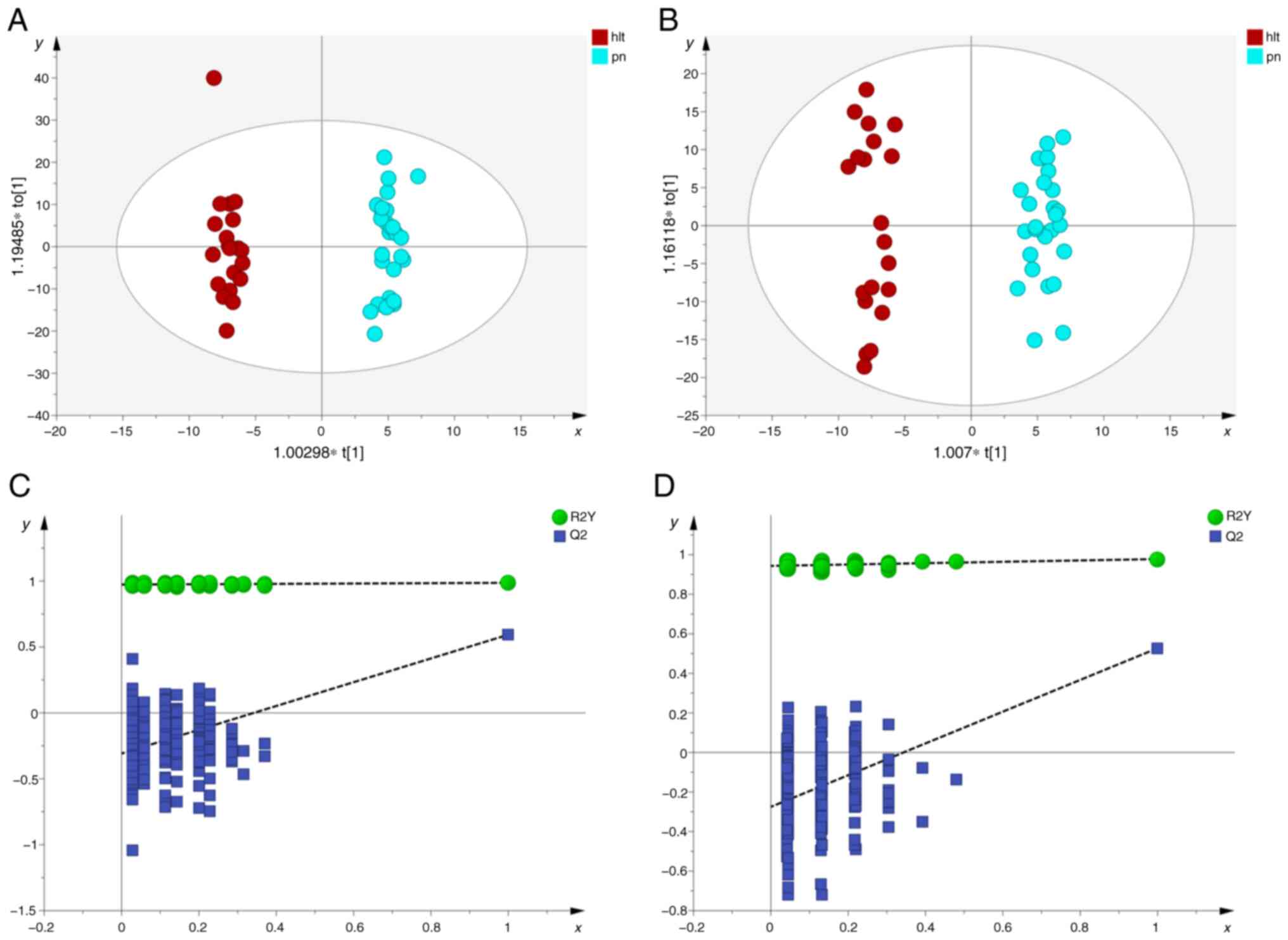

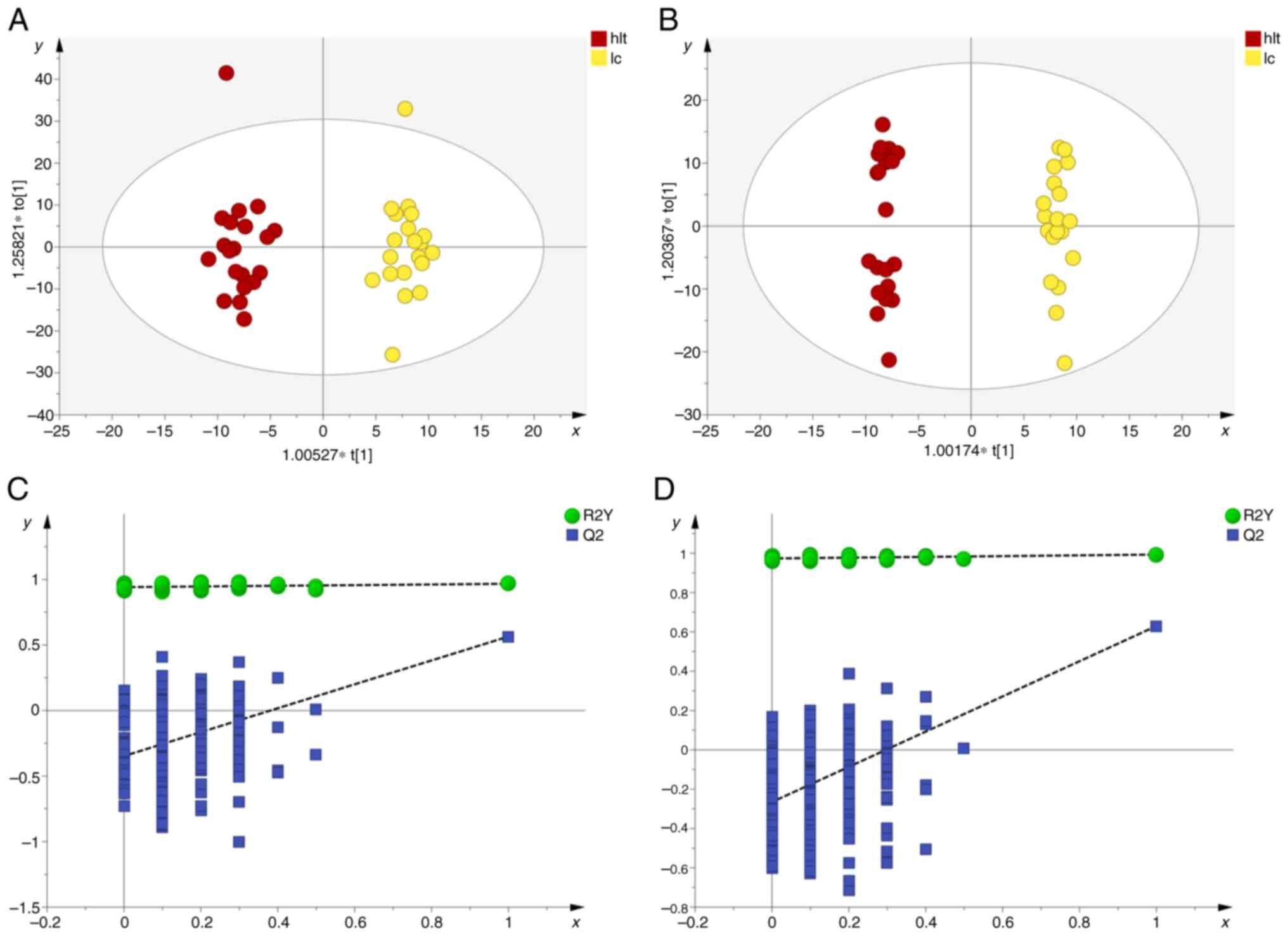

elucidate this distinction, OPLS-DA analysis was conducted. The

results demonstrated a notable separation between the pulmonary

nodule and healthy groups, lung cancer and healthy groups, as well

as between the pulmonary nodule and lung cancer groups, across both

positive and negative ion modes, indicating notable metabolic

differences among the groups (Fig.

3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

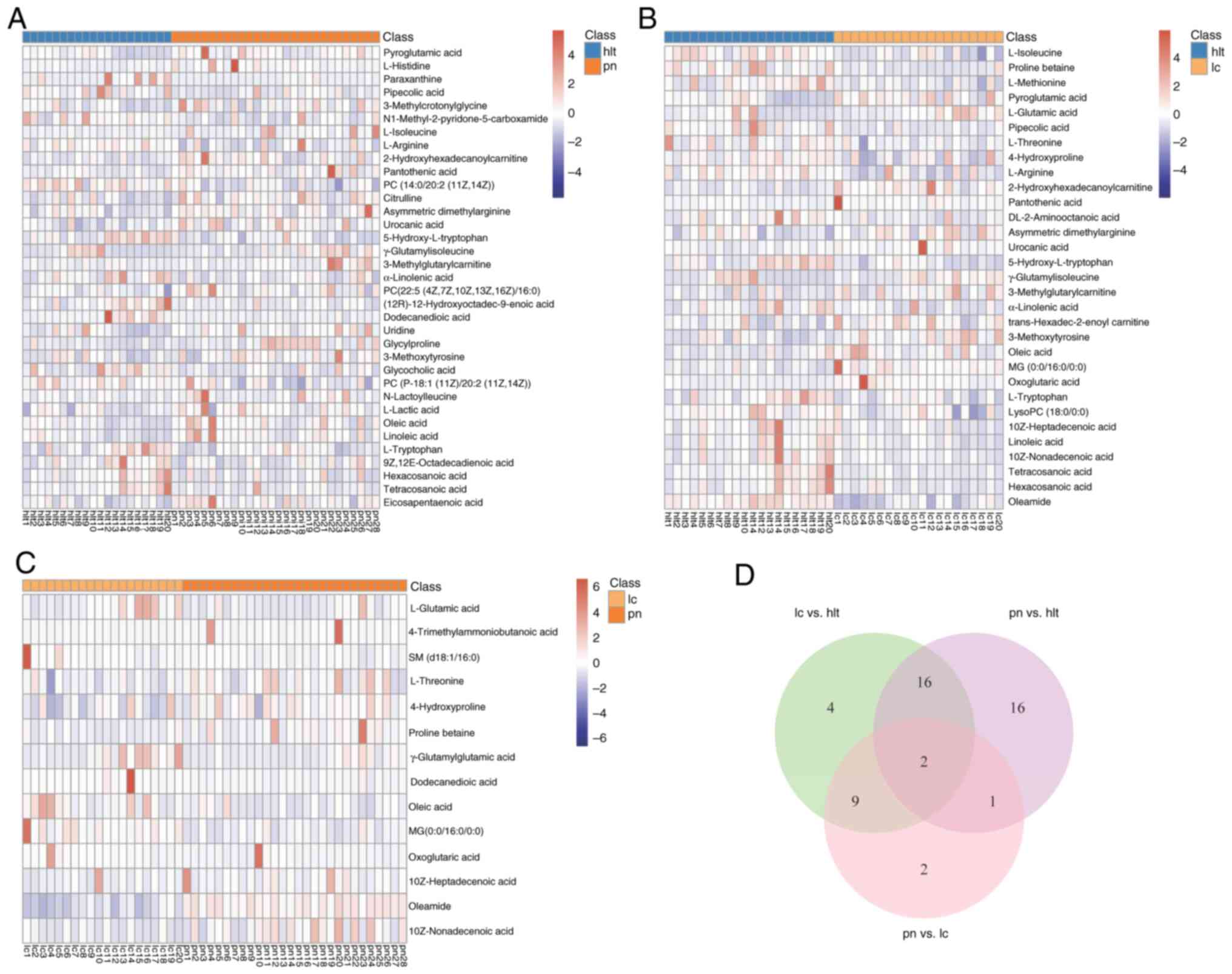

Differential metabolite selection

among the lung cancer, pulmonary nodule and healthy groups

Differential metabolites were selected based on the

VIP values and P-values from the OPLS-DA analysis. The results

indicated that under both positive and negative ion modes, a total

of 50 differential metabolites were identified among the lung

cancer, lung nodule and healthy control groups. Among them, 35

differential metabolites were identified between the pulmonary

nodule and healthy groups (Fig.

6A), 31 differential metabolites were identified between the

lung cancer and healthy groups (Fig.

6B) and 14 differential metabolites were identified between the

pulmonary nodule and lung cancer groups (Fig. 6C).

By comparing the differential metabolites among the

groups, 18 overlapping differential metabolites were identified

between the pulmonary nodule and healthy groups, as well as between

the lung cancer and healthy groups, with 16 of these demonstrating

the same trend of change in both comparisons. This reflected the

clinical similarities between patients with pulmonary nodules and

those with lung cancer. In addition, there were 11 overlapping

differential metabolites between the pulmonary nodule and healthy

groups, as well as between the pulmonary nodule and lung cancer

groups. Furthermore, there were three overlapping differential

metabolites between the lung cancer and healthy groups, as well as

between the pulmonary nodule and lung cancer group. The Venn

diagram indicates the overlap of the differential metabolites in

the three comparisons (Fig. 6D).

Detailed information on the overlapping metabolites is provided in

Table II.

| Table II.Differential metabolites with common

metabolic characteristics across groups. |

Table II.

Differential metabolites with common

metabolic characteristics across groups.

| Pulmonary nodules

and healthy groups vs. lung cancer and healthy groups (n=18) | Lung cancer and

healthy groups vs. pulmonary nodules and lung cancer groups

(n=11) | Pulmonary nodules

and healthy groups vs. pulmonary nodules and lung cancer groups

(n=3) |

|---|

| Pyroglutamic

acid | Oxoglutaric

acid | Oleic acid |

|

2-Hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine |

MG(0:0/16:0/0:0) |

γ-Glutamylisoleucine |

| Pantothenic

acid | L-glutamic

acid | Dodecanedioic

acid |

| Asymmetric

dimethylarginine | L-threonine | - |

| Urocanic acid |

4-Hydroxyproline | - |

|

γ-Glutamylisoleucine | Proline

betaine | - |

|

3-Methylglutarylcarnitine | 10z-Heptadecenoic

acid | - |

|

3-Methoxytyrosines | Oleamide | - |

| Oleic acid | 10z-Nonadecenoic

acid | - |

| L-isoleucine | Oleic acid | - |

| Linoleic acid |

γ-Glutamylisoleucine | - |

|

5-Hydroxy-L-tryptophan | - | - |

| α-Linolenic

acid | - | - |

| L-Tryptophan | - | - |

| Hexacosanoic

acid | - | - |

| Tetracosanoic

acid | - | - |

| L-arginine | - | - |

| Pipecolic acid | - | - |

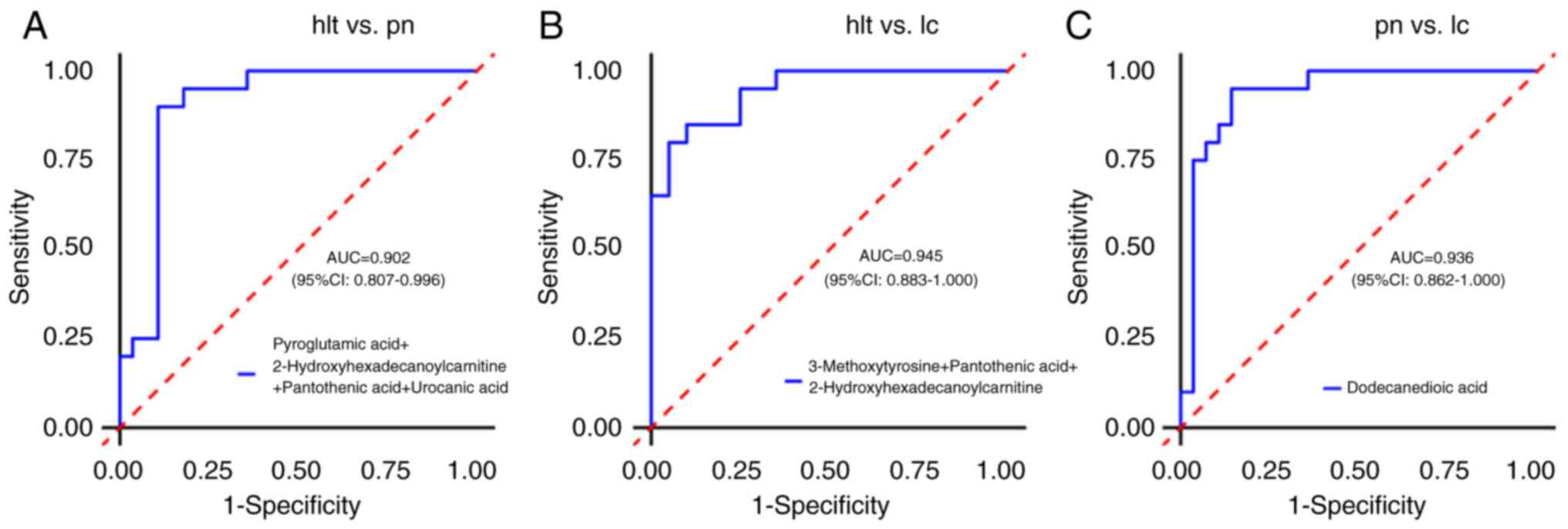

Potential diagnostic biomarker

selection

ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the

diagnostic value of plasma metabolites among patients with lung

cancer, pulmonary nodules and healthy individuals, in order to

identify potential diagnostic biomarkers. The results indicated

that the AUC values for all differential metabolites between the

pulmonary nodule and healthy groups, as well as between the lung

cancer and healthy groups, were <0.9, suggesting that the

diagnostic value of single differential metabolites was low.

Further combination analysis of differential metabolites revealed

that in the pulmonary nodule and healthy groups, the joint

detection of pyroglutamic acid, 2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine,

pantothenic acid and urocanic acid achieved an AUC value of 0.902

(95% CI, 0.807–0.996), indicating a high diagnostic value, with

sensitivity and specificity of 89.3 and 90.0%, respectively

(Fig. 7A). In the lung cancer and

healthy groups, the combined detection of 3-methoxytyrosine,

pantothenic acid and 2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine resulted in an

AUC value of 0.945 (95% CI, 0.883–1.000), also indicating a high

diagnostic value, with sensitivity and specificity of 90.0 and

80.0%, respectively (Fig. 7B). Of

note, urocanic acid, pyroglutamic acid, pantothenic acid,

3-methoxytyrosine and 2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine were

overlapping differential metabolites between the pulmonary nodule

and the healthy groups, as well as between the lung cancer and the

healthy groups, displaying the same trend of change. This suggested

that these differential metabolites may serve as biomarkers to

distinguish patients with lung cancer and pulmonary nodules from

healthy individuals.

Furthermore, ROC curve analysis was conducted

between the lung cancer and the pulmonary nodule groups to identify

potential diagnostic biomarkers that can differentiate between

patients with lung cancer and those with pulmonary nodules. The

results demonstrated that the AUC value for dodecanedioic acid was

0.936 (95% CI, 0.862–1.000), indicating a high diagnostic value,

with a sensitivity of 95.0% and specificity of 85.7% (Fig. 7C). This suggested that dodecanedioic

acid has potential clinical application value in screening for lung

cancer and pulmonary nodules and can serve as an effective

biomarker to distinguish between the two.

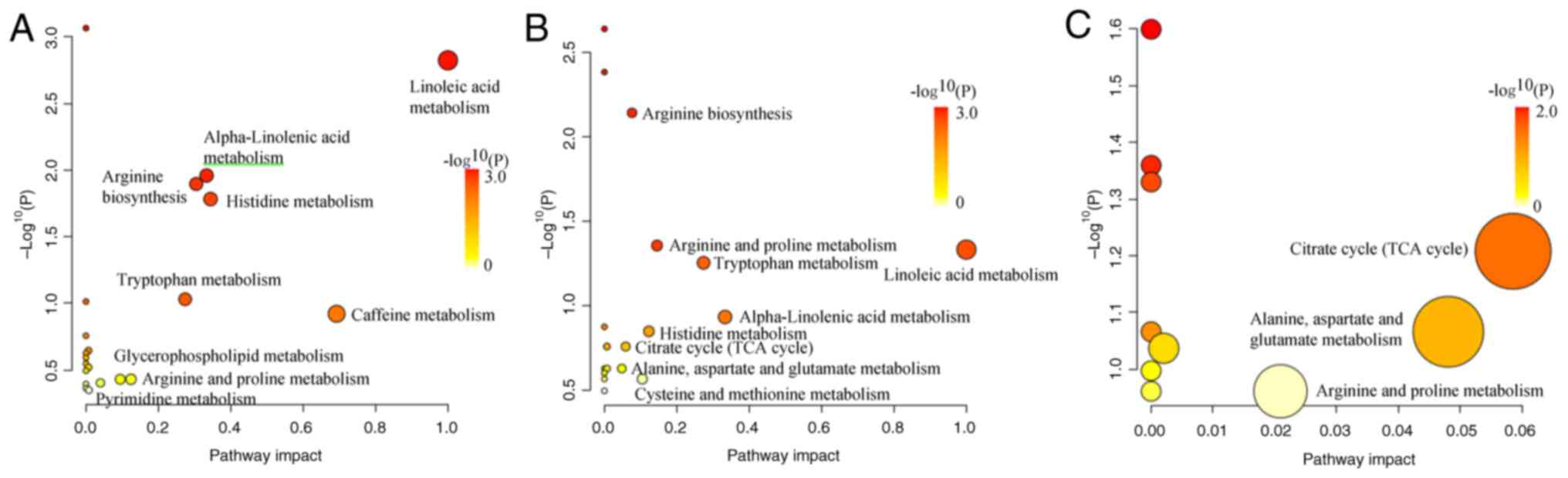

Metabolic pathway analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed on the

selected differential metabolites. The results demonstrated that a

total of 21 metabolic pathways were enriched in both the pulmonary

nodules and healthy groups, among which 9 pathways exhibited

significant changes, including ‘linoleic acid metabolism’,

‘caffeine metabolism’, ‘histidine metabolism’, ’α-linolenic acid

metabolism’, ‘arginine biosynthesis’, ‘tryptophan metabolism’,

‘arginine and proline metabolism’, ‘glycerophospholipid metabolism’

and ‘pyrimidine metabolism’ (Fig.

8A). As compared with the healthy group, a total of 18

metabolic pathways were enriched in the lung cancer group, with 9

pathways demonstrating significant changes: ‘Linoleic acid’,

‘α-linolenic acid metabolism’, ‘tryptophan metabolism’, ‘arginine

and proline metabolism’, ‘histidine metabolism’, ‘cysteine and

methionine metabolism’, ‘arginine biosynthesis’, ‘citrate cycle

[tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle]’ and ‘alanine, aspartate and

glutamate metabolism’ (Fig. 8B). In

the comparison between the pulmonary nodule and lung cancer groups,

a total of 10 metabolic pathways were enriched, with 3 pathways

demonstrating notable changes: ‘Citrate cycle (TCA cycle)’,

‘alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism’ and ‘arginine and

proline metabolism’ (Fig. 8C).

By comparing the metabolic pathways among the

groups, it was identified that between the pulmonary nodule and

healthy groups, as well as between the lung cancer and healthy

groups, six metabolic pathways were shared: ‘Linoleic acid

metabolism’, ‘α-linolenic acid metabolism’, ‘tryptophan

metabolism’, ‘arginine and proline metabolism’, ‘histidine

metabolism’ and ‘arginine biosynthesis’. Between the pulmonary

nodule and healthy groups, as well as between the pulmonary nodule

and lung cancer groups, arginine and proline metabolism was a

shared and significantly altered pathway. In addition, between the

lung cancer and healthy groups, as well as between the pulmonary

nodule and lung cancer groups, three metabolic pathways were

shared: ‘Citrate cycle (TCA cycle)’, ‘alanine, aspartate and

glutamate metabolism’ and ‘arginine and proline metabolism’.

Furthermore, the present study revealed that ‘arginine and proline

metabolism’ is a pathway that indicated significant changes across

all three groups.

Discussion

Lung cancer staging is a key determinant of

prognosis (7). Several countries,

such as the USA and the UK, have implemented lung cancer screening

programs aimed at improving outcomes through early diagnosis

(23–25). CT, as the primary screening tool,

offers rich morphological information, high sensitivity and

technical maturity (10,26). However, its specificity is

relatively low, as certain benign lesions share imaging

characteristics with lung cancer, leading to overdiagnosis

(27). To address this limitation,

current research focuses on multimodal strategies and the

development of novel methods. For example, using artificial

intelligence to mine radiomic features and integrate multimodal

data to enhance CT specificity (5,27).

Metabolomics is an emerging technology and analyzes metabolites

(15). As the products of

interactions among genes, RNA and proteins, metabolites can reflect

the current physiological and pathological states of the body in

real time (28) and have the

potential for high specificity, offering a novel avenue to improve

the diagnostic specificity of lung cancer in the future. In the

present study, LC-MS was used to identify specific metabolic

biomarkers that distinguish lung cancer, pulmonary nodules and

healthy individuals, providing a novel strategy for early

diagnosis.

The differential metabolites and ROC curves from the

present study demonstrated that urocanic acid, pyroglutamic acid,

pantothenic acid, 3-methoxytyrosine and

2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine display the same trend of changes in

lung cancer, pulmonary nodules and healthy individuals. In

addition, dodecanedioic acid can distinguish between pulmonary

nodule and lung cancer, suggesting that the aforementioned

metabolites are involved in the occurrence and development of lung

cancer. This is consistent with previous literature. Filaggrin is

degraded into histidine, which is then converted into urocanic acid

by histidinase. Urocanic acid undergoes a series of enzymatic

reactions to form glutamic acid (29–31).

The glutamic acid is subsequently metabolized into pyroglutamic

acid, which influences glutamine and glutathione metabolism,

thereby participating in tumorigenesis (32,33).

Pantothenic acid is a precursor of coenzyme A, which is acetylated

to form acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), participating in processes

such as the TCA cycle and lipid metabolism, thereby affecting the

growth and proliferation of cancer (34–36).

The HMDB indicates that 3-methoxytyrosine is a tyrosine-derived

metabolite, while 2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine is classified as a

member of fatty acid esters. Dysregulation of tyrosine metabolism

can not only lead to lung cancer but also interplay with the tumor

immune microenvironment, which serves a key role in cancer

development (37–39). In addition, it has been reported

that 3-methoxytyrosine may regulate immune responses by modulating

enzyme activity (40) and these

immune responses are closely associated with tumorigenesis and

progression (41,42). Fatty acid esters are derivatives of

fatty acids, and fatty acids can then feed into various metabolic

pathways, such as the synthesis of complex lipids like

triacylglycerides, and participation in β-oxidation processes,

providing energy for tumor proliferation and producing intermediate

products that connect different metabolic activities (43). This is a key factor in the

occurrence of cancer (44).

Dodecanedioic acid, a 12C/medium-chain water-soluble

dicarboxylic acid, undergoes oxidative metabolism in mitochondria

to generate acetyl-CoA (45).

Acetyl-CoA provides substrates and raw materials for fatty acid

synthesis and histone acetylation modification, which are key

pathways in the occurrence and progression of cancer (46,47).

Therefore, the present study suggested that urocanic acid,

pyroglutamic acid, pantothenic acid, 3-methoxytyrosine and

2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine can serve as biomarkers to

distinguish patients with lung cancer from those with pulmonary

nodules and healthy individuals. Dodecanedioic acid is a potential

biomarker for early lung cancer diagnosis of patients with

pulmonary nodule. To the best of our knowledge, the results of the

present study are novel and have not been covered in previous

studies. Compared with the high-abundance metabolites detected by

NMR, such as lipoproteins and glucose and the volatile metabolites

identified by GC-MS, such as naphthalene and propene, the LC-MS

employed in the present study detected certain different

metabolites, including small molecular organic acids,

acylcarnitines and modified amino acids, expanding the metabolic

profile of lung cancer (48–50).

The findings from the metabolic pathway enrichment

analysis demonstrated that there are notable abnormalities in

pathways associated with amino acids and lipids among lung cancer,

pulmonary nodules and healthy individuals. This suggested that the

mechanisms underlying the development of lung cancer may be

associated with these two metabolic alterations. Research has

revealed that metabolic reprogramming of amino acids and lipids

represents a hallmark of tumorigenesis (51,52).

Amino acids, as components of proteins and signaling molecules,

serve a role in various biological processes, including the

biosynthesis of proteins and nucleic acids, energy production,

oxidative stress homeostasis and epigenetic modifications (51,53).

These biological processes established favorable conditions for the

occurrence of tumors. For instance, amino acids, such as glycine

and aspartate, provide carbon and nitrogen for purine synthesis in

cancer cells (54); glutamine

metabolism can drive the TCA cycle to maintain mitochondrial ATP

production, supplying energy to cancer cells (55); and tryptophan metabolism through the

kynurenine pathway mediates tumor immune evasion (56). Lipids primarily support cancer cell

energy supply and participate in cancer cell signal transduction

and membrane structure formation through metabolic processes, such

as re-regulated uptake and synthesis, as well as fatty acid

oxidation (52,57), thereby promoting tumorigenesis. For

instance, fatty acid oxidation can generate a notable amount of

ATP, providing energy for the rapid proliferation of cancer cells

(58,59). Increased fatty acid synthesis can

meet the material requirements for cancer cell membrane generation,

sustaining cancer cell proliferation (59,60).

Oleic acid can promote cancer cell proliferation by inducing the

activation of relevant enzymes and pathways, as well as promote the

expression level of cyclin D1, facilitating the G1-to-S

phase transition in the cell cycle and accelerating cell

proliferation (61). The results of

the present study support and supplement previous research: A

previous study on lung cancer has identified that the principal

changes in metabolic pathways among healthy individuals, pulmonary

nodules and lung cancer involve the amino acid metabolism (62). However, the present study identified

that, in addition to changes in amino acid metabolism, lipid

metabolism also underwent alterations.

Furthermore, the results of the metabolic pathway

enrichment analysis emphasized the significant role of arginine and

proline metabolism in the development of lung cancer. A previous

study reported that arginine and proline metabolism are closely

associated with glutamine metabolism, which can be utilized by

cancer cells to accelerate tumor growth (63), serving as a hallmark of tumor

progression. Glutamine is metabolically converted into glutamate.

Glutamate can be converted to proline under the action of

pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid (P5C) synthase. Proline can be

converted to arginine through the intermediate P5C and arginine,

under the hydrolysis of arginase, generates urea and ornithine

(63,64). On one hand, ornithine can be

transformed into citrulline by ornithine transcarbamylase and

citrulline can be converted back into arginine through the urea

cycle; on the other hand, it can serve as a precursor for the

synthesis of proline or glutamate (63,65,66).

This metabolic process forms the glutamine-arginine-proline

metabolic axis, which has been shown to serve a notable role in

cancer progression.

The present study, as an exploratory investigation,

had two main limitations: Firstly, the sample size was relatively

small, which may not fully capture the metabolic heterogeneity of

the study population, leading to the potential missed detection of

certain differential metabolites. Secondly, although ROC analysis

indicated that the metabolic biomarkers in the present study have

good diagnostic efficacy, the current results have not yet been

validated in independent cohorts and their clinical applicability

requires further investigation. In the future, our group plans to

conduct multi-center, large-sample studies to systematically

validate the clinical applicability and generalizability of the

present findings.

In conclusion, the present study employed LC-MS to

analyze and compare the plasma metabolic profiles of patients with

lung cancer, pulmonary nodules and healthy individuals. Strict

filtration criteria were applied to select differential metabolites

and potential biomarkers. A total of 50 differential metabolites

were identified, which were enriched in pathways associated with

amino acid and lipid metabolism, including ‘linoleic acid

metabolism’, ‘α-linolenic acid metabolism’, ‘arginine and proline

metabolism’ and others. The ROC curve analysis identified six

potential biomarkers with good sensitivity and specificity to

distinguish lung cancer, pulmonary nodules and healthy individuals,

including urocanic acid, pyroglutamic acid, pantothenic acid,

3-methoxytyrosine, 2-hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine and dodecanedioic

acid. Furthermore, the findings from the present study on metabolic

changes in lung cancer may provide novel insights into

understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease. In

the future, a systematic and in-depth investigation of lung cancer

by integrating proteomics, genomics and other approaches may be

conducted to facilitate the practical application of potential

biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The Clinical Scientific Research Fund for Central High-Level

Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospitals [grant no. DZMG-TZZX-24005

and the present study was supported by the Special Fund for

Fundamental Research of Central Universities (grant no.

2022-JYB-JBZR-029)].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Metabolights database under accession no. MTBLS12985 or

using the following URL: http://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/metabolights/studies/public/MTBLS12985/).

Authors' contributions

YLiu acquired the data, conceived and designed the

present study and revised the final version of the manuscript.

YangL analyzed the data, conceived and designed the present study,

and wrote the manuscript. HH acquired the data. YD, HT, YZ and JZ

collected plasma from enrolled volunteers. KL read the chest CT of

enrolled volunteers and collected data. YLi and FS designed the

present study and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. FS

acquired the data and conceived the study. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Ethical Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital of Beijing University of

Chinese Medicine (approval no. 2022DZMEC-312-02; Beijing, China).

All participants were fully informed of the study and gave their

written informed consent before participation in the present study.

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools (OpenAI and their language model, chatGPt 4.0)

were used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript

or to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence tools as

necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of

the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer Statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36

Cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bi H, Yin L, Fang W, Song S, Wu S and Shen

J: Association of CEA, NSE, CYFRA 21-1, SCC-Ag, and ProGRP with

Clinicopathological characteristics and chemotherapeutic outcomes

of lung cancer. Lab Med. 54:372–379. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang Y, Guo Q, Huang Z, Song L, Zhao F, Gu

T, Feng Z, Wang H, Li B, Wang D, et al: Cell-free epigenomes

enhanced fragmentomics-based model for early detection of lung

cancer. Clin Transl Med. 15:e702252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang C, Li J, Huang J and Wu S: Computed

tomography image under convolutional neural network deep learning

algorithm in pulmonary nodule detection and lung function

examination. J Healthc Eng. 2021:34172852021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liang J, Ye G, Guo J, Huang Q and Zhang S:

Reducing False-positives in lung nodules detection using balanced

datasets. Front Public Health. 9:6710702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu Z, Wang F, Cao W, Qin C, Dong X, Yang

Z, Zheng Y, Luo Z, Zhao L, Yu Y, et al: Lung cancer risk prediction

models based on pulmonary nodules: A systematic review. Thorac

Cancer. 13:664–677. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zheng J, Hao Y, Guo Y, Du M, Wang P and

Xin J: An 18F-FDG-PET/CT-based radiomics signature for estimating

malignance probability of solitary pulmonary nodule. Clin Respir J.

18:e137512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhu K, Tang S, Pan D, Wang X, Xu Y, Yan J,

Wang L, Chen C and Yang M: Development and biological evaluation of

a novel CEACAM6-targeted PET tracer for distinguishing malignant

nodules in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 52:2414–2430. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nooreldeen R and Bach H: Current and

future development in lung cancer diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci.

22:86612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang X, Chen Y, Ma C, Bi L, Su Z, Li W and

Wang Z: Current advances and future prospects of blood-based

techniques for identifying benign and malignant pulmonary nodules.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 207:1046082025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang CF, Peng SJ, Liu RQ, Yu YJ, Ge QM,

Liang RB, Li QY, Li B and Shao Y: The combination of CA125 and NSE

is useful for predicting liver metastasis of lung cancer. Dis

Markers. 2020:88508732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Anwardeen NR, Diboun I, Mokrab Y, Althani

AA and Elrayess MA: Statistical methods and resources for biomarker

discovery using metabolomics. BMC Bioinformatics. 24:2502023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang S, He T and Wang H: Non-targeted

metabolomics study for discovery of hepatocellular carcinoma serum

diagnostic biomarker. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 239:1158692024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huang X, Chen L, Liu L, Chen H, Gong Z,

Lyu J, Li Y, Jiang Q, Zeng X, Zhang P and Zhou H: Untargeted

metabolomics analysis reveals the potential mechanism of

imatinib-induced skin rash in patients with gastrointestinal

stromal tumor. Int Immunopharmacol. 140:1127282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J and Siuzdak G:

Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 17:451–459. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xu K, Berthiller F, Metzler-Zebeli BU and

Schwartz-Zimmermann HE: Development and validation of targeted

metabolomics methods using liquid Chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for the quantification of 235 plasma

metabolites. Molecules. 30:7062025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang R, Hu Q, Wu Y, Guan N, Han X and Guan

X: Intratumoral lipid metabolic reprogramming as a pro-tumoral

regulator in the tumor milieu. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1878:1889622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rispoli MG, Valentinuzzi S, De Luca G, Del

Boccio P, Federici L, Di Ioia M, Digiovanni A, Grasso EA, Pozzilli

V, Villani A, et al: Contribution of metabolomics to multiple

sclerosis diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

22:111122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liang S, Cao X, Wang Y, Leng P, Wen X, Xie

G, Luo H and Yu R: Metabolomics analysis and diagnosis of lung

cancer: Insights from diverse sample types. Int J Med Sci.

21:234–252. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang Y, Li Z, Lazar L, Fang Z, Tang C and

Zhao J: Metabolomics workflow for lung cancer: Discovery of

biomarkers. Clin Chim Acta. 495:436–445. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chelala L, Hossain R, Kazerooni EA,

Christensen JD, Dyer DS and White CS: Lung-RADS version 1.1:

Challenges and a look ahead, from the AJR special series on

radiology reporting and data systems. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

216:1411–1422. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Aunger J, Yip KP, Dosanjh K, Scandrett K,

Ungureanu B, Newnham M and Turner AM: Interventions to improve

adherence to clinical guidelines for the management and Follow-Up

of pulmonary nodules: A systematic review. Chest. 168:248–268.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kramer BS, Berg CD, Aberle DR and Prorok

PC: Lung cancer screening with Low-dose helical CT: Results from

the national lung screening Trial (NLST). J Med Screen. 18:109–111.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

O Reilly D, Roche S, Noonan C, O'Shea J,

Toomey S, Hennessy BT, Fitzmaurice GJ, Egan K, Dunne J, Dowling CM,

et al: Lung health check pilot: Ireland's flagship lung cancer

screening trial. BMJ Open Respir Res. 12:e0030352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhao Y and Wang Z, Liu X, Chen Q, Li C,

Zhao H and Wang Z: Pulmonary nodule detection based on multiscale

feature fusion. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022:89030372022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu J, Tao J, Zhu M, Liu J, Ma C, Chen K,

Wang Y, Lu X, Saito Y and Ni B: Development and validation of CT

radiomics diagnostic models: Differentiating benign from malignant

pulmonary nodules and evaluating malignancy degree. J Thorac Dis.

17:1645–1672. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xu L, Chang C, Jiang P, Wei K, Zhang R,

Jin Y, Zhao J, Xu L, Shi Y, Guo S, et al: Metabolomics in

rheumatoid arthritis: Advances and review. Front Immunol.

13:9617082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pham DL, Lim KM, Joo KM, Park HS, Leung

DYM and Ye YM: Increased cis-to-trans urocanic acid ratio in the

skin of chronic spontaneous urticaria patients. Sci Rep.

7:13182017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang L, Tan Y, Wang H, Yu XD, Mo Y, Reilly

J, He Z and Shu X: Urocanic acid facilitates acquisition of object

recognition memory in mice. Physiol Behav. 266:1142012023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hart PH and Norval M: The multiple roles

of urocanic acid in health and disease. J Invest Dermatol.

141:496–502. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mi M, Liu Z, Zheng X, Wen Q, Zhu F, Li J,

Mungur ID and Zhang L: Serum metabolomic profiling based on GC/MS

helped to discriminate diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with

different prognosis. Leuk Res. 111:1066932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Vidman L, Zheng R, Bodén S, Ribbenstedt A,

Gunter MJ, Palmqvist R, Harlid S, Brunius C and Van Guelpen B:

Untargeted plasma metabolomics and risk of colorectal cancer-an

analysis nested within a large-scale prospective cohort. Cancer

Metab. 11:172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Peterson CT, Rodionov DA, Osterman AL and

Peterson SN: B vitamins and their role in immune regulation and

cancer. Nutrients. 12:33802020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hrubša M, Siatka T, Nejmanová I,

Vopršalová M, Kujovská Krčmová L, Matoušová K, Javorská L, Macáková

K, Mercolini L, Remião F, et al: Biological properties of vitamins

of the B-Complex, part 1: Vitamins B1, B2, B3, and B5. Nutrients.

14:4842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen G, Bao B, Cheng Y, Tian M, Song J,

Zheng L and Tong Q: Acetyl-CoA metabolism as a therapeutic target

for cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 168:1157412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhou Y, Li X, Long G, Tao Y, Zhou L and

Tang J: Identification and validation of a tyrosine

metabolism-related prognostic prediction model and characterization

of the tumor microenvironment infiltration in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Front Immunol. 13:9942592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang X, Chen Y, Lan B, Wang Y, Lin W,

Jiang X, Ye J, Shang B, Feng C, Liu J, et al: Heterogeneity of

tyrosine-based melanin anabolism regulates pulmonary and cerebral

organotropic colonization microenvironment of melanoma cells.

Theranostics. 12:2063–2079. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu T and Dai Y: Tumor microenvironment and

therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 387:61–68. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zou X, Huang H and Tan Y: Genetically

determined metabolites in allergic conjunctivitis: A Mendelian

randomization study. World Allergy Organ J. 17:1008942024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang L, Chu Z, Liu M, Zou Q, Li J, Liu Q,

Wang Y, Wang T, Xiang J and Wang B: Amino acid metabolism in immune

cells: Essential regulators of the effector functions, and

promising opportunities to enhance cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Z, Hu Y, Chen Y, Chen Z, Zhu Y, Chen

M, Xia J, Sun Y and Xu W: Immunometabolism in the tumor

microenvironment and its related research progress. Front Oncol.

12:10247892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Koundouros N and Poulogiannis G:

Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer.

122:4–22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Broadfield LA, Pane AA, Talebi A, Swinnen

JV and Fendt SM: Lipid metabolism in cancer: New perspectives and

emerging mechanisms. Dev Cell. 56:1363–1393. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Radzikh I, Fatica E, Kodger J, Shah R,

Pearce R and Sandlers YI: Metabolic outcomes of anaplerotic

dodecanedioic acid supplementation in very long Chain Acyl-CoA

dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficient fibroblasts. Metabolites.

11:5382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

He W, Li Q and Li X: Acetyl-CoA regulates

lipid metabolism and histone acetylation modification in cancer.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1888372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Feron O: The many metabolic sources of

acetyl-CoA to support histone acetylation and influence cancer

progression. Ann Transl Med. 7 (Suppl 8):S2772019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Noreldeen HAA: Recent advances in lung

cancer lipidomics: Analytical techniques and their applications.

Clin Chim Acta. 577:1204702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Rocha CM, Carrola J, Barros AS, Gil AM,

Goodfellow BJ, Carreira IM, Bernardo J, Gomes A, Sousa V, Carvalho

L, et al: Metabolic signatures of lung cancer in biofluids:

NMR-based metabonomics of blood plasma. J Proteome Res.

10:4314–4324. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Musharraf SG, Mazhar S, Choudhary MI, Rizi

N and Atta-ur-Rahman: Plasma metabolite profiling and chemometric

analyses of lung cancer along with three controls through gas

chromatography-mass spectrometry. Sci Rep. 5:86072015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li X and Zhang HS: Amino acid metabolism,

redox balance and epigenetic regulation in cancer. FEBS J.

291:412–429. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jin HR, Wang J, Wang ZJ, Xi MJ, Xia BH,

Deng K and Yang JL: Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor

microenvironment: From mechanisms to therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol.

16:1032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu X, Ren B, Ren J, Gu M, You L and Zhao

Y: The significant role of amino acid metabolic reprogramming in

cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xu X, Peng Q, Jiang X, Tan S, Yang Y, Yang

W, Han Y, Chen Y, Oyang L, Lin J, et al: Metabolic reprogramming

and epigenetic modifications in cancer: From the impacts and

mechanisms to the treatment potential. Exp Mol Med. 55:1357–1370.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lieu EL, Nguyen T, Rhyne S and Kim J:

Amino acids in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 52:15–30. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Greene LI, Bruno TC, Christenson JL,

D'Alessandro A, Culp-Hill R, Torkko K, Borges VF, Slansky JE and

Richer JK: A Role for Tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase in CD8 T-cell

suppression and evidence of tryptophan catabolism in breast cancer

patient plasma. Mol Cancer Res. 17:131–139. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yang K, Wang X, Song C, He Z, Wang R, Xu

Y, Jiang G, Wan Y, Mei J and Mao W: The role of lipid metabolic

reprogramming in tumor microenvironment. Theranostics.

13:1774–1808. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Snaebjornsson MT, Janaki-Raman S and

Schulze A: Greasing the wheels of the cancer machine: The role of

lipid metabolism in cancer. Cell Metab. 31:62–76. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

An Q, Lin R, Wang D and Wang C: Emerging

roles of fatty acid metabolism in cancer and their targeted drug

development. Eur J Med Chem. 240:1146132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Acharya R, Shetty SS and Kumari NS: Fatty

acid transport proteins (FATPs) in cancer. Chem Phys Lipids.

250:1052692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang Y, Wang D, Lv B, Hou X, Liu Q, Liao

C, Xu R, Zhang Y, Xu F and Zhang P: Oleic acid and insulin as key

characteristics of T2D promote colorectal cancer deterioration in

xenograft mice revealed by functional metabolomics. Front Oncol.

11:6850592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yu M, Wen W, Wang Y, Shan X, Yi X, Zhu W,

Aa J and Wang G: Plasma metabolomics reveals risk factors for lung

adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 14:12772062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wang D, Duan JJ, Guo YF, Chen JJ, Chen TQ,

Wang J and Yu SC: Targeting the glutamine-arginine-proline

metabolism axis in cancer. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 39:23671292024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Matos A, Carvalho M, Bicho M and Ribeiro

R: Arginine and arginases modulate metabolism, tumor

microenvironment and prostate cancer progression. Nutrients.

13:45032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Du T and Han J: Arginine metabolism and

its potential in treatment of colorectal cancer. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:6588612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Niu F, Yu Y, Li Z, Ren Y, Li Z, Ye Q, Liu

P, Ji C, Qian L and Xiong Y: Arginase: An emerging and promising

therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Biomed Pharmacother.

149:1128402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|