Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents one of the

most prevalent malignant tumors within the genitourinary system,

accounting for ~5% of all newly diagnosed cancers in men and 3% in

women (1). Previous statistical

data have shown that, in 2019, the United States recorded ~73,820

new diagnoses of RCC, and 14,770 mortalities were attributed to RCC

(1). Among the diverse subtypes of

RCC, clear cell RCC (ccRCC) has emerged as the predominant form and

is widely regarded as one of the most aggressive malignancies in

the urinary tract, with an annual global mortality rate of ~90,000

cases (2). Cytokine-based and

checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapies have been shown to elicit

robust immune responses through distinct mechanisms, thereby having

a pivotal role in RCC treatment (3,4).

However, despite the major improvements that have been made in

terms of understanding tumor initiation and progression, the

etiological mechanisms underlying RCC remain poorly understood

(5). Due to the high incidence and

mortality rates associated with RCC, it is essential to identify

predictive biomarkers that impact immune responses in patients

diagnosed with this malignancy.

Chemokines, a class of small, secreted proteins, are

recognized for their pivotal regulatory roles in mediating immune

cell trafficking and lymphatic tissue development (6,7). As

the largest subfamily of cytokines, chemokines can be further

classified into four primary subgroups according to the arrangement

of their two cysteine (C) residues in their protein sequences,

namely CC-chemokines, CXC-chemokines, C-chemokines and

CX3C-chemokines (7). Within the

tumor microenvironment (TME), chemokines are expressed by a diverse

array of cell types, encompassing both tumor cells themselves and

other essential components, such as immune cells and stromal cells

(8,9). In response to specific chemokines,

diverse immune cell subsets migrate to the TME, orchestrating the

immune response against tumors in a precisely regulated manner

(8,9). Additionally, chemokines directly

target non-immune cells within the TME, including tumor, stromal

and vascular endothelial cells, which have been shown to modulate

tumor cell proliferation, tumor stemness properties and tumor

invasion and metastasis (10).

Consequently, chemokines exert both direct and indirect effects on

tumor immunity, thereby shaping the immunological and biological

phenotypes of tumors, and subsequently influencing tumor

progression, treatment efficacy and patient prognosis (8,10,11).

CXC motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) belongs to the

glutamate-leucine-arginine (ELR) + CXC chemokine subfamily that is

distinguished by the conserved amino acid sequence of ELR (12). The role of CXCL1 is mediated through

its interaction with its receptor, CXCR2 (13). To date, a burgeoning body of

evidence has demonstrated that CXCL1 displays an increased level of

expression in a variety of different types of human malignancies,

with CXCL1 serving as a potent signal within the TME that promotes

malignant progression (13). The

present study therefore aimed to investigate the expression

patterns of CXCL1 in RCC tissues, also exploring whether CXCL1, as

a component of the RCC microenvironment, may contribute to the

carcinogenic potential of RCC through exogenous and autocrine

mechanisms. The findings of the present study may help to

facilitate the discovery of valuable biomarkers and potential

therapeutic targets for the clinical diagnosis and molecular

targeted therapy of RCC.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The initial CXCL1 RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data were

acquired from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and Gene Expression

Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) databases. The

expression of CXCL1 in tumor tissues, as well as its expression in

tumor tissues with different pathological parameters, was

investigated in the GSE53757 dataset (including RNA-seq data of 72

pairs of normal kidneys and tumor tissues) and the GSE40435 dataset

(including 101 pairs of matched adjacent and tumor tissue RNA-seq

data) (14,15). The STRING database (https://string-preview.org) was utilized to identify

core (hub) genes that are co-expressed with CXCL1, and the

expression levels of these hub genes were subsequently examined

using TCGA database. Furthermore, the tumor immune estimation

resource (TIMER) database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) was used to

assess the association between CXCL1 expression and immune cell

recruitment. To determine the MSI status, MSI scores were

calculated using the program Microsatellite Analysis for

Normal-Tumor InStability (MANTIS) with a default threshold of 0.4,

defining high MSI (MSI-H) as scores above the threshold, and

microsatellite stable (MSS or no apparent MSI) as scores below

it.

Clinical samples and

immunohistochemical analysis

Paraffin-embedded specimens, which had undergone

surgical resection at the First Affiliated Hospital of Jiamusi

University (Jiamusi, China) between February 2023 and January 2025

and were subsequently diagnosed as RCC by the Department of

Pathology, were selected for the present study. A total of 68 pairs

of RCC tissues and their corresponding adjacent non-cancerous

tissues, along with complete clinical data, were randomly chosen

for inclusion in the present study. The clinical characteristics of

these 68 samples are presented in Table

I. The study included patients with histologically confirmed

renal cell carcinoma who underwent partial or radical nephrectomy

and for whom high-quality paired tumor and adjacent non-cancerous

tissue samples were available. All participants had complete

clinicopathological data (age, sex, stage and grade). Exclusion

criteria were prior systemic anti-tumor therapy, previous renal

surgery or biopsy on the same kidney, and a concurrent malignancy.

In brief, the specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin

at room temperature for 24 h, then processed into paraffin blocks

and cut into 5-µm thick sections. These sections were

deparaffinized with 100% xylene at room temperature and

subsequently rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Antigen

retrieval was carried out in a high-pressure cooker using 0.01 M

citric-acid buffer at 120°C for 10 min. To suppress endogenous

peroxidase activity, slides were incubated in 3%

H2O2 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature.

Non-specific binding sites were blocked by applying 20% normal goat

serum (cat. no. AR0009; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.)

and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Finally, the sections were incubated

overnight at 4°C with a CXCL1-specific antibody (dilution, 1:100;

cat. no. YT2074; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company), and subsequently

processed using a StreptAvidin-Biotin Complex Kit (cat. no. SA1022;

Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.), in accordance with the

manufacturer's instructions. The sections were subjected to routine

3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining and hematoxylin counterstaining at

room temperature for 15 min, followed by an assessment of CXCL1

protein expression, as determined under an epifluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation) by two specified parameters: i)

Intensity of staining, ranging from negative-weak (assigned a score

of 1) to moderate (score of 2), strong (score of 3) and extremely

strong (score of 4); and ii) the proportion of stained cells,

categorized as ≤25% (score of 1), >25% to ≤50% (score of 2),

>50% to ≤75% (score of 3) and >75% (score of 4). The total

score was calculated by generating the sum of the parameters (i)

and (ii). A score of ≤4 was indicative of low expression, whereas a

score of ≥5 was indicative of high expression. The staining

intensity was quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media

Cybernetics, Inc.).

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of patients

with clear cell renal carcinoma. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with clear cell renal carcinoma.

| Characteristic | n |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 46 |

|

Female | 22 |

| Age, years |

|

|

≥60 | 21 |

|

<60 | 47 |

| Tumor grade |

|

| Grade

1 | 31 |

| Grade

2 | 26 |

| Grade

3 | 11 |

| Clinical stage |

|

| Stage

I | 44 |

| Stage

II | 20 |

| Stage

III | 4 |

Cell lines and cell culture

The human ccRCC cell line 786-O and papillary RCC

(pRCC) cell line CAKI-2 were supplied by the American Type Culture

Collection. The cell lines were maintained in Gibco RPMI-1640

medium (cat. no. 11875093; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% Gibco fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

A5670201; Thermo Fisher Scientiffc, Inc.) and 1:100

penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. PYG0016; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.). In the present study, the medium containing FBS

and penicillin/streptomycin was referred to as complete medium

(CM).

Cell transfection

Overexpression and RNA-interference strategies were

employed for transfection experiments. Pseudovirus particles

containing either empty lentiviral plasmids (cat. no.

LPP-NEG-Lv201-100) or overexpression lentiviral plasmids (cat. no.

LPP-G0095-Lv201-100) were produced by GeneCopoeia, Inc., whereas

small interfering (si)RNAs were synthesized by HyCyte, Inc. The

sense and antisense sequences specifically designed for

RNA-interference to silence the CXCL1 gene were:

5′-GAUGCUGAACAGUGACAAATT-3′ and 5′-UUUGUCACUGUUCAGCAUCTT-3′;

5′-CCAAGAACAUCCAAAGUGUTT-3′ and 5′-ACACUUUGGAUGUUCUUGGTT-3′; and

5′-GCUGCUCCUGCUCCUGGUATT-3′ and 5′-UACCAGGAGCAGGAGCAGCTT-3′. The

negative-control sense and antisense sequence were

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′. Cell

transfection was carried out according to the supplier's

instructions. In the overexpression study, a total of

4×104 cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well

plate in 500 µl of serum-free medium. After a 24 h incubation at

37°C under starvation conditions, lentiviral particles were added

directly to the medium at a multiplicity of infection of

10−8. Following a further 5 h incubation at 37°C, an

additional 500 µl of 10% serum-containing medium was added. A total

of 24 h later, the entire medium was replaced with fresh complete

medium. 72 h after the initial viral infection, puromycin was added

to a final concentration of 2 µg/ml for selection. Finally,

downstream experiments were performed after an additional 72 h

incubation to allow sufficient phenotypic expression. In the

RNA-interference study, 1.25 µl siRNA stock solution was diluted

with 50 µl Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and

was gently pipetted 3–5 times. Meanwhile, 1.0 µl

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was diluted with 50 µl Opti-MEM, and was gently

pipetted 3–5 times. After standing at room temperature for 5 min,

the transfection reagent and siRNA dilution were mixed and gently

pipetted 3–5 times. Subsequently, they were left to stand at room

temperature for 20 min. Finally, the transfection complex was added

to the 24-well cell plate with cells.

ELISA detection assay

Within each compartment of the 6-well dishes,

5×105 cells were grown in 1 ml serum-free medium.

Following 24 h culture, the supernatant was isolated via

centrifugation at 4°C, 1,000 × g for 5 min, and a Human CXCL1 ELISA

kit (cat. no. EK0722; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) was

employed to determine and quantify the level of CXCL1 in the

supernatant, following precisely the manufacturer's instructions.

The ELISA experiments were repeated three times.

Cell proliferation detection

assay

Concerning the exogenous study, 786-O and CAKI-2

cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well dish at a density of

3×103 cells/well, utilizing CM supplemented with various

concentrations (0, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 30 ng/ml) of exogenous CXCL1

(cat. no. 300-11-25UG; PeproTech, Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Concerning the endogenous study, 786-O and CAKI-2 cells with

overexpression of CXCL1, 786-O and CAKI-2 cells with decreased

expression of CXCL1, along with their corresponding control cells

were seeded into each well of a 96-well dish at a density of

3×103 cells/well, and CM served as the growth medium for

all cell types. The cells were subsequently incubated for 72 h.

Subsequently, 10 µl Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (cat. no.

AR1160; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) was added to each

well, and the cells were further incubated for 2 h in the

incubator. Finally, the optical density (OD) values at a wavelength

of 450 nm were read using a microplate reader. The cell

proliferation assay experiments were repeated three times.

Cell migration detection assay

The 786-O and CAKI-2 cells were seeded at a density

of 1×104 cells/well into the top chambers of Transwell

dishes (cat. no. 3428; Corning, Inc.). The top chambers were filled

with serum-free medium containing various concentrations of

exogenous CXCL1, whereas the bottom chambers were maintained with

CM. Concerning the endogenous study, 786-O and CAKI-2 cells with

overexpression of CXCL1, 786-O and CAKI-2 cells with decreased

expression of CXCL1, along with their respective control cells were

seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/well (for

overexpression study) or 3×104 cells/well (for siRNA

study) into the top chambers of the Transwell dishes. The top

chambers were filled with serum-free medium, whereas the bottom

chambers contained CM. The cells were subsequently incubated for 48

h, after which the upper surface of the chambers was gently wiped

with a cotton swab to remove the non-migrated cells. Following

methanol fixation and crystal violet staining at room temperature

for 20 min, the chambers were imaged under an inverted microscope

in order to count the numbers of migrated cells. The cell migration

experiments were repeated three times.

Western blotting assay

Total cellular proteins were extracted and

quantified utilizing RIPA protein lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and a BCA protein quantitation

kit (cat. no. AR0146; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.,

respectively. Subsequently, 40 µg total protein was subjected to

12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (cat. no.

IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma). The membrane was incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies against Bcl-2-associated X protein

(Bax; cat. no. CY5059; Shanghai Abways Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

1:1,000), B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2; cat. no. CY5032; Shanghai

Abways Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; 1:1,000), phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K; cat. no. CY5224; Shanghai Abways Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

1:1,000), AKT (cat. no. AF6261; Affinity Biosciences; 1:1,000) and

β-actin (cat. no. TA811000; OriGene Technologies, Inc.; 1:5,000).

Subsequently, the membrane was further incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 min (cat.

no. BA1055, Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) at a dilution

of 1:10,000 and ECL reagents (cat. no. 34095; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), prior to being placed in a Tanon 4200 Fully

Automatic Chemiluminescence/Fluorescence Image Analysis System

(Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for visualization and

imaging. Protein quantification was performed with Tanon Image

software (Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The western

blotting experiments were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistics software, version 22.0 (IBM

Corp.) was employed for statistical analyses. The variabilities in

CXCL1 expression among different groups were compared using the

Mann-Whitney U test. To assess the prognostic value of CXCL3, both

univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed.

Pearson correlation analysis was employed to assess the

relationship between CXCL1 expression and immune cell recruitment.

In the cellular experiments, comparisons between two groups were

performed with an unpaired two-sample t-test. For comparisons among

three or more groups, a one-way ANOVA was applied. When the one-way

ANOVA revealed a significant overall effect (P<0.05), pairwise

comparisons were conducted using the Tukey's post hoc test.

Results

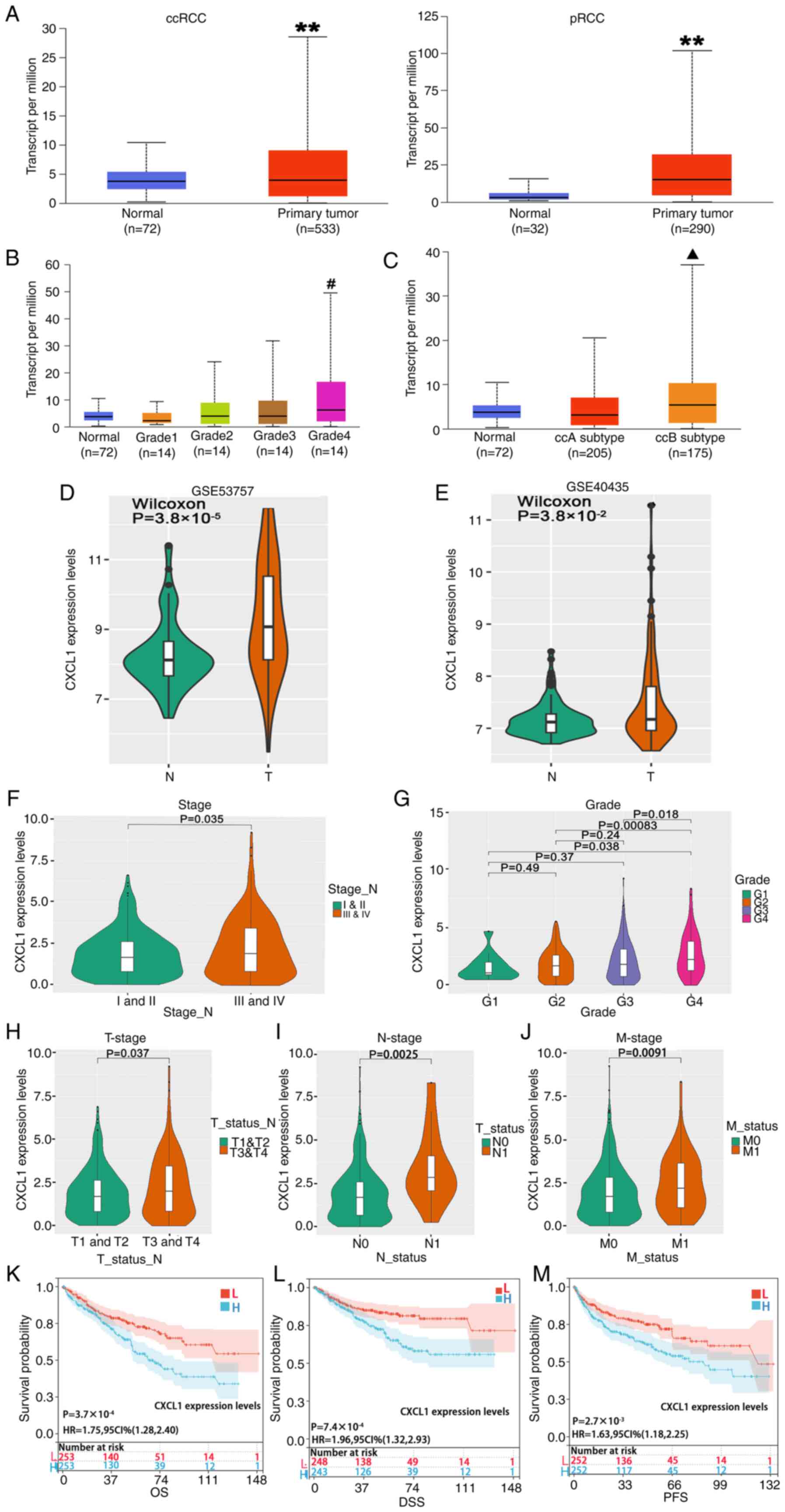

Expression of CXCL1 mRNA is

upregulated in RCC tissues, and its high expression is associated

with the clinical characteristics of patients with RCC

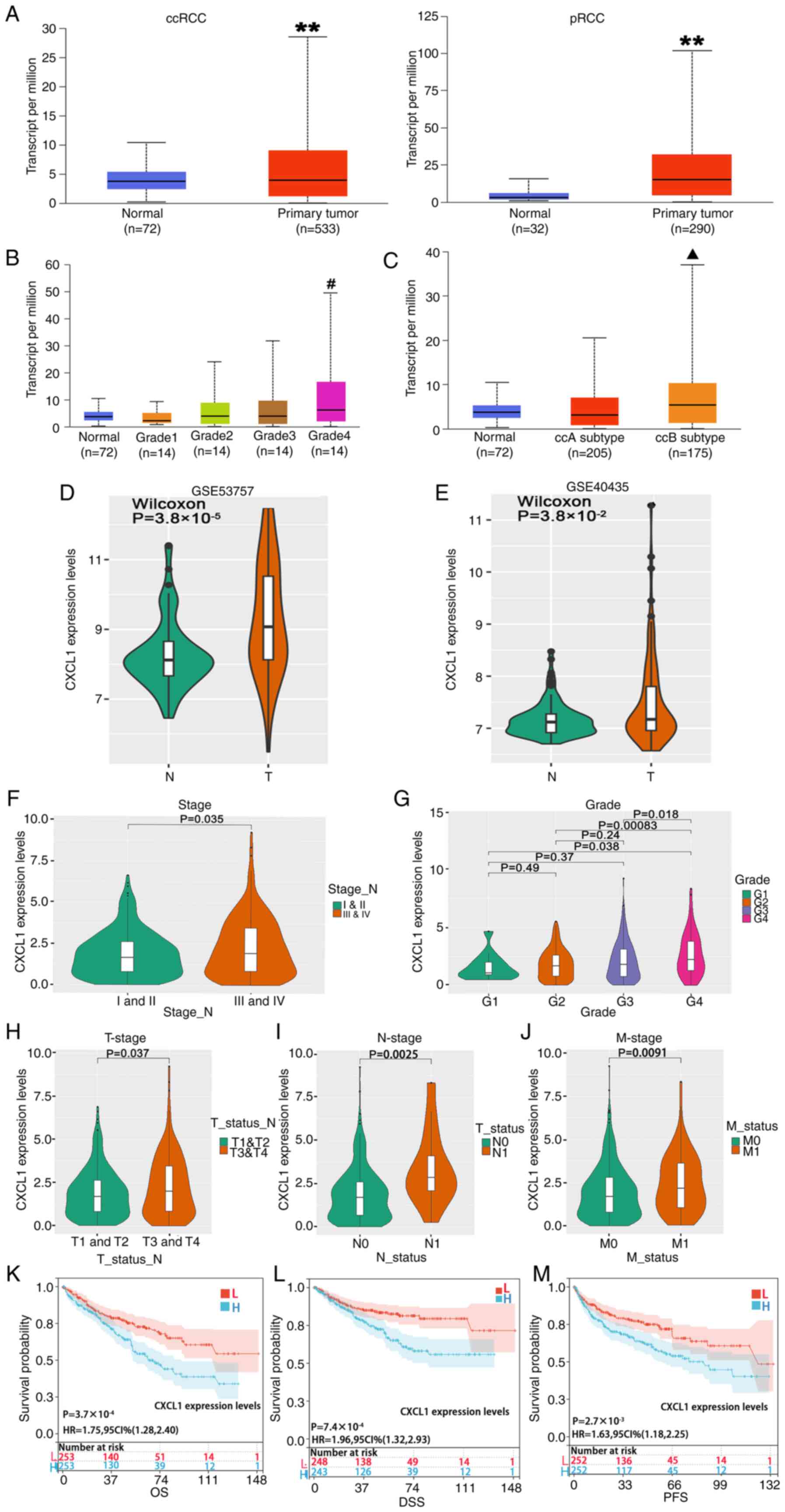

TCGA database analysis revealed that the expression

level of CXCL1 mRNA in ccRCC or pRCC tissues was significantly

upregulated compared with normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Due to ccRCC being the most

prevalent subtype of RCC, subsequent experiments in the present

study were focused on ccRCC. The analysis of clinical grade

(Fig. 1B) and subtypes (Fig. 1C) revealed that the expression level

of CXCL1 in grade 4 ccRCC was significantly higher compared with

that in the normal tissues and grades 1 and 2 ccRCC, and the ccB

subtype exhibited a notably increased expression level compared

with both normal tissue and the ccA subtype. Additionally, in both

the GSE53757 dataset and the GSE40435 dataset, the expression

levels of CXCL1 mRNA were markedly increased in ccRCC samples

compared with the normal tissues (Fig.

1D) or the paracancerous tissues (Fig. 1E). Moreover, clinical staging

analysis revealed that patients with stage III/IV ccRCC exhibited

significantly higher CXCL1 expression levels compared with those

with stage I/II ccRCC (Fig. 1F).

Similarly, grade 4 tumors exhibited significantly upregulated CXCL1

expression levels compared with grade 1–3 tumors (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, significant

associations were observed between the expression levels of CXCL1

and tumor status (T; Fig. 1H),

lymph node status (N; Fig. 1I) and

metastasis status (M; Fig. 1J). A

prognostic assessment was performed among the different groups

utilizing the log-rank test method, which revealed that high CXCL1

expression was significantly associated with shorter overall

survival (OS) times, (Fig. 1K),

shorter disease-specific survival times (Fig. 1L) and shorter progression-free

survival times (Fig. 1M).

| Figure 1.Increased expression of CXCL1 mRNA

levels is associated with the clinical characteristics of patients

with RCC. (A) The expression profiles of CXCL1 mRNA in normal

tissues compared with ccRCC or pRCC tissues. The different levels

of expression of CXCL1 mRNA within (B) different clinical grades

and (C) subtypes of ccRCC tissues. Expression levels of CXCL1 mRNA

in the (D) GSE53757 and the (E) GSE40435 datasets. The different

levels of expression of CXCL1 mRNA within different (F) clinical

grades and (G) stages of ccRCC tissues. Analysis of the expression

level of CXCL1 within the clinical (H) T-status, (I) N-status and

(J) M-status categories in ccRCC tissues. (K-M) A prognostic

assessment was performed among the various groups. **P<0.01 vs.

normal; #P<0.01 vs. normal, grade 1 and 2;

▲P<0.01 vs. normal and ccA subtype. CXCL1, CXC motif

chemokine ligand 1; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; ccRCC, clear cell

RCC; pRCC, papillary RCC; T, tumor; N, lymph node; M, metastasis;

OS, overall survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; PFS,

progression-free survival. |

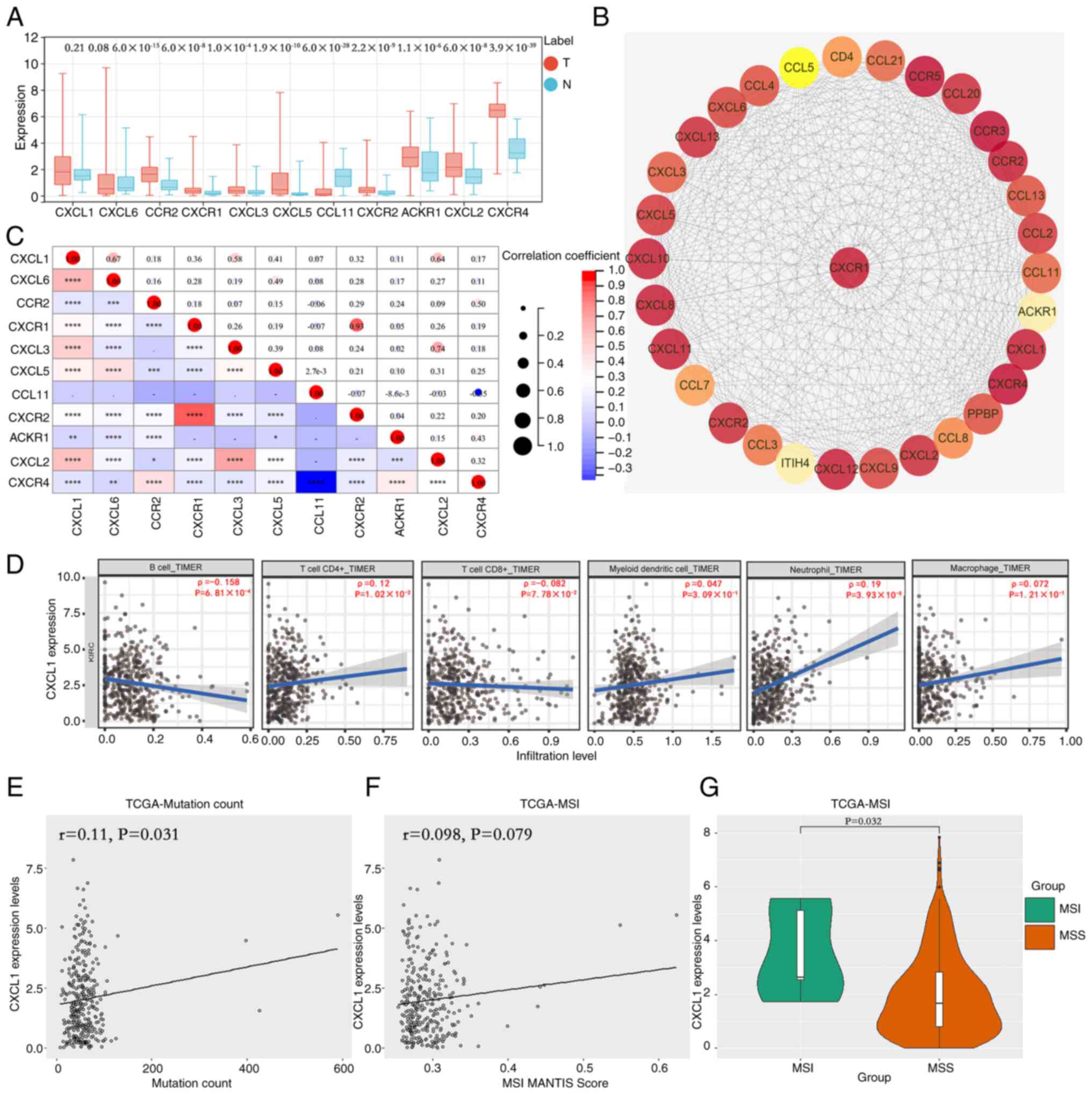

CXCL1 expression is associated with

the expression of tumor-associated genes, immune cell recruitment

and microsatellite instability (MSI) in RCC

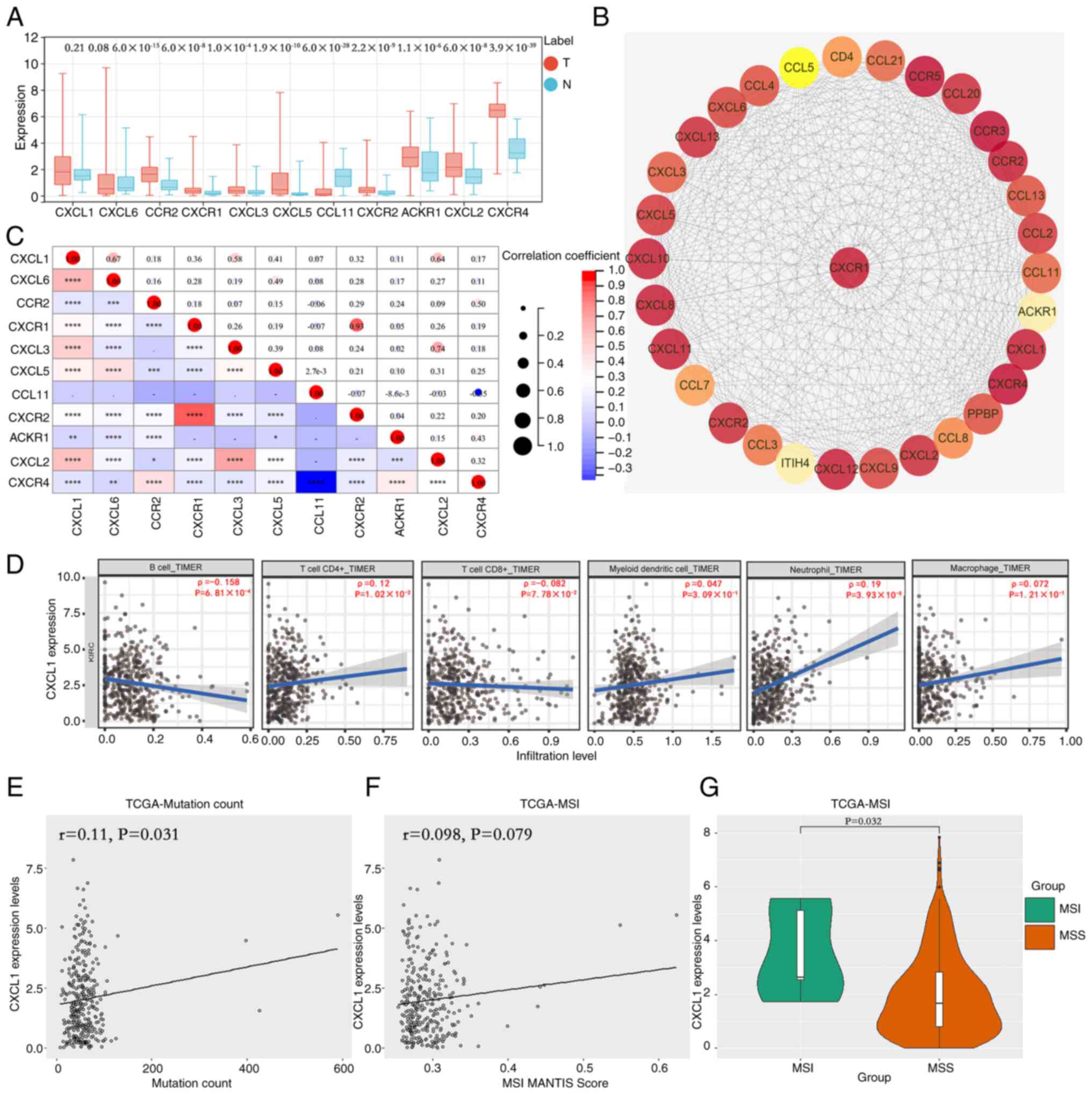

STRING database analysis disclosed 10 hub genes that

exhibited co-expression with CXCL1 in ccRCC, namely CXCL6, C-C

chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), CXCR1, CXCL3, CXCL5, C-C motif

chemokine 11 (CCL11), CXCR2, atypical chemokine receptor 1 (ACKR1),

CXCL2 and CXCR4. TCGA database was employed to assess the

expression levels of these 10 key genes, and the results

demonstrated a significant reduction in the expression of CCL11,

and a notable increase in the expression levels of CCR2, CXCR1,

CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCR2, ACKR1, CXCL2 and CXCR4 (Fig. 2A). A protein-interaction network

analysis that was subsequently constructed based on the CXCL1 gene

revealed that numerous chemokines and their receptors exhibited

strong interactions with CXCL1 (Fig.

2B). Correlation analysis indicated that, excluding CCL11,

CXCL1 exhibited a significant positive correlation with the

expression of the other nine genes (Fig. 2C). TIMER database analysis unveiled

a negative correlation between CXCL1 expression and the

infiltration of B cells, whereas a positive correlation was

observed with the recruitment of CD4+ T cells and

neutrophils (Fig. 2D). The findings

obtained from MSI status study demonstrated a positive correlation

between CXCL1 expression and both the number of mutations (Fig. 2E) and MSI scores (Fig. 2F) in patients with RCC. Furthermore,

patients in the MSI group exhibited significantly higher CXCL1

expression levels compared with those in the MSS group (Fig. 2G).

| Figure 2.Expression levels of CXCL1 mRNA are

correlated with the expression of genes implicated in

tumorigenesis, recruitment of immune cells and presence of MSI in

renal cell carcinoma. (A) Identification of 10 hub genes exhibiting

co-expression with CXCL1. (B) Analysis of the protein-interaction

network involving CXCL1. (C) Analysis of the correlation between

CXCL1 and the aforementioned 10 hub genes. (D) Analysis of the

correlation between CXCL1 expression and immune cell recruitment.

The correlation between CXCL1 expression and the (E) number of

mutations is presented, as well as (F) MSI scores. (G) The

expression levels of CXCL1 in the MSI group compared with the MSS

group. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001.

CXCL, CXC motif chemokine ligand; ACKR1, atypical chemokine

receptor 1; CCR, C-C chemokine receptor type 2; MSI, microsatellite

instability; MSS, microsatellite stable or no apparent MSI; TIMER,

tumor immune estimation resource; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; T,

tumor; N, normal. |

Expression of CXCL1 protein is

upregulated in RCC tissues, and its elevated expression is

associated with the clinicopathological features of patients with

RCC

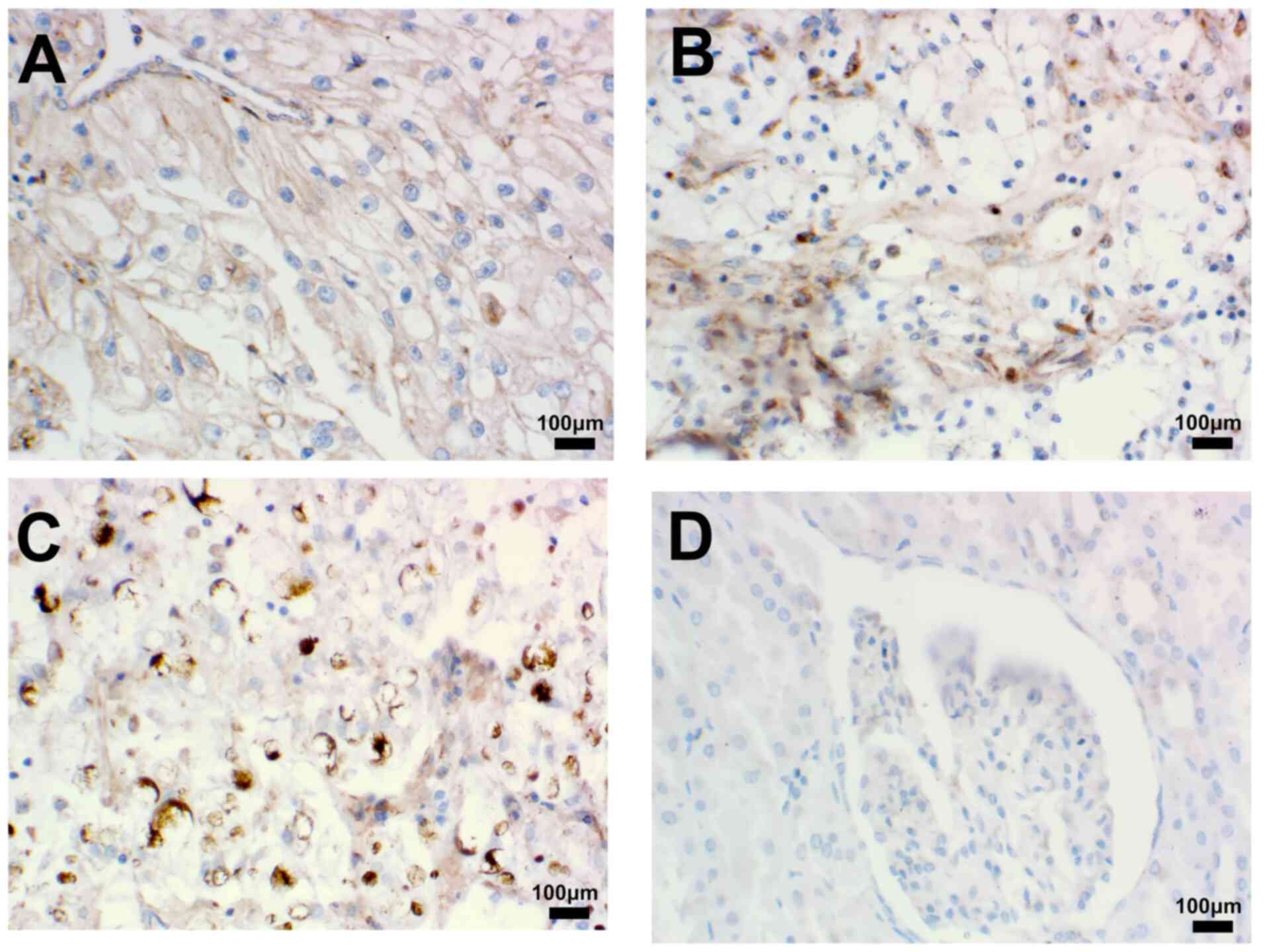

To further elucidate the clinical significance of

CXCL1 in RCC, immunohistochemical experiments were utilized to

assess the expression of the CXCL1 protein. The results obtained

demonstrated that the expression of CXCL1 was significantly

upregulated in RCC tissues compared with paracancerous tissues

(Fig. 3A-D). In addition, the study

of the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with RCC

revealed that the CXCL1 protein level in patients with grade 2–3

RCC was significantly higher compared with that in patients with

grade 1. In addition, the CXCL1 protein expression levels in

patients with stage II/III cancer was significantly higher compared

with that in patients with stage I. However, the present study did

not find any association between the expression level of CXCL1

protein and the age or the sex of the patients (Table II).

| Table II.Expression of CXCL1 in renal cell

carcinoma and their adjacent tissues. |

Table II.

Expression of CXCL1 in renal cell

carcinoma and their adjacent tissues.

| Characteristic | CXCL1 expression

(mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|

| Tissue |

| <0.0001 |

|

Adjacent non-cancerous

tissues | 4.485±1.440 |

|

|

Cancerous tissues | 5.485±1.275 |

|

| Sex |

| 0.3836 |

|

Male | 5.391±1.325 |

|

|

Female | 5.682±1.171 |

|

| Age, years |

| 0.9690 |

|

≥60 | 5.489±1.333 |

|

|

<60 | 5.476±1.167 |

|

| Tumor grade |

| 0.0340 |

| Grade

1 | 5.129±1.176 |

|

|

Grade2-3 | 5.784±1.294 |

|

| Clinical stage |

| 0.0384 |

| Stage

I | 5.250±1.296 |

|

| Stage

II/III | 5.917±1.139 |

|

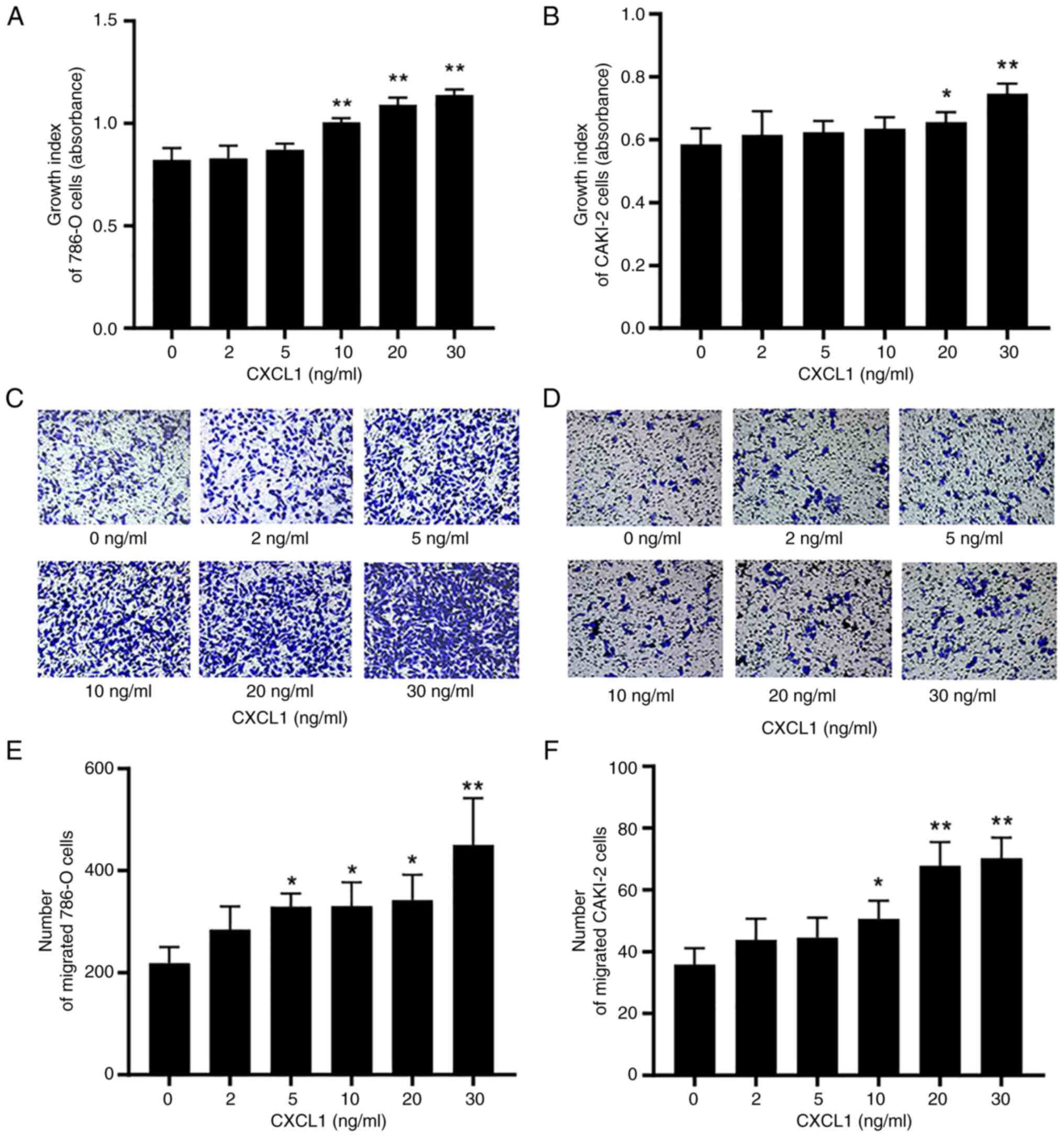

Exogenous CXCL1 contributes to the

malignant behaviors of RCC cells

To assess whether CXCL1 is involved in the tumor

biological behavior of RCC cells through paracrine or endocrine

pathways, relevant studies were performed using exogenous CXCL1.

CCK-8 assay analysis revealed that the proliferation rates of 786-O

and CAKI-2 cells treated with exogenous CXCL1 at concentrations of

10, 20 and 30 ng/ml (for 786-O cells) or 20 and 30 ng/ml (for

CAKI-2 cells) were significantly increased after 72 h in comparison

with the 0 mg/ml treatment group (Fig.

4A and B). Furthermore, the Transwell assay experiments also

demonstrated that the migratory capabilities of the 786-O cells

treated with 5, 10, 20 and 30 ng/ml exogenous CXCL3 and the CAKI-2

cells treated with 10, 20 or 30 ng/ml exogenous CXCL3 after 48 h

were significantly enhanced (Fig.

4C-F).

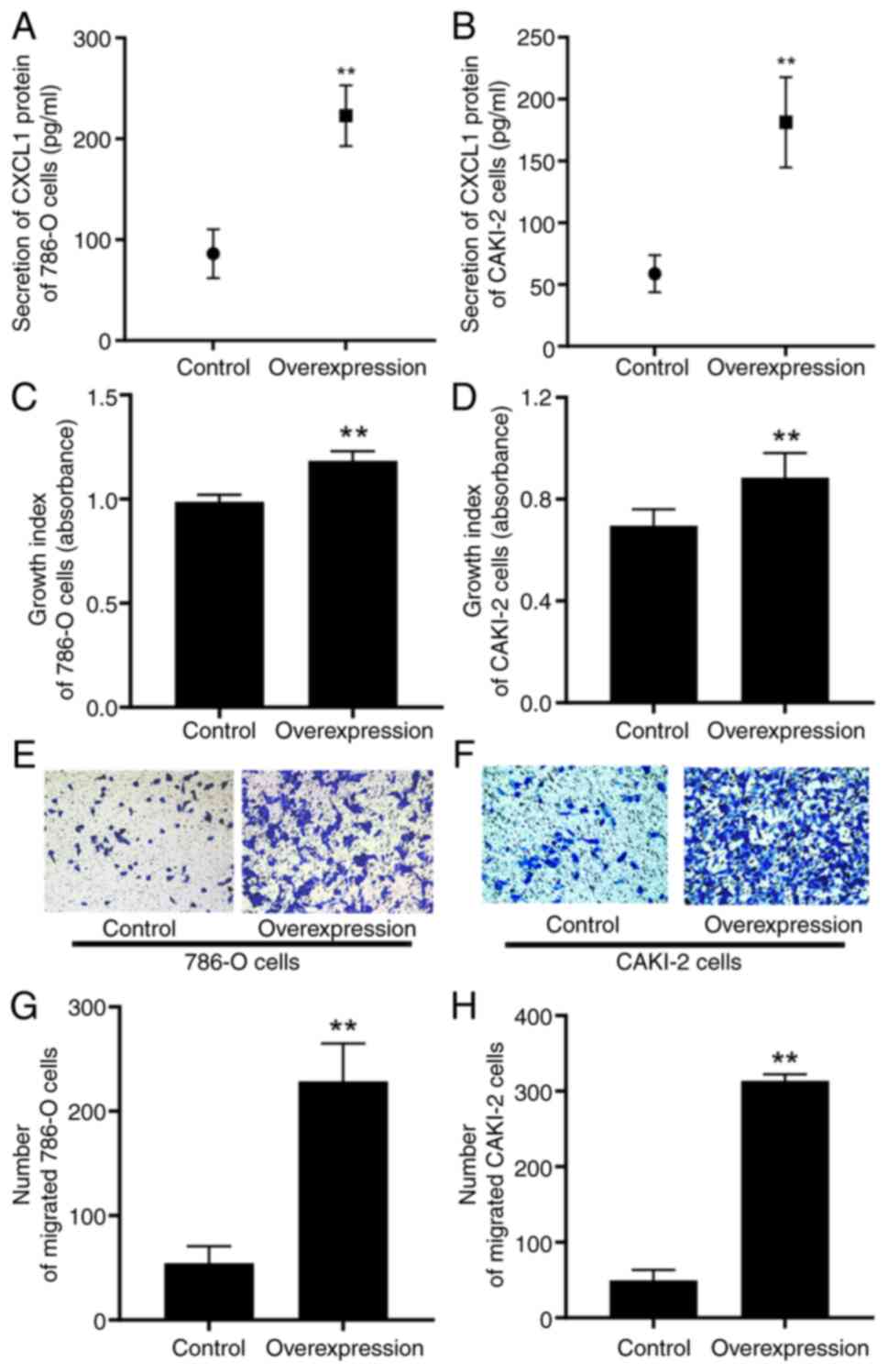

High expression of CXCL1 facilitates

the malignant behaviors of RCC cells

To clarify the involvement of endogenous CXCL1 in

the biological behavior of RCC progression through an autocrine

pathway, lentiviral transfection was used to establish RCC cell

lines with a high expression level of CXCL1. ELISA assay revealed

that, in comparison with their respective control cells, the

secretory levels of CXCL1 protein were significantly increased in

the 786-O and CAKI-2 cells expressing a high level of CXCL1

(Fig. 5A and B). Subsequent CCK-8

and Transwell assays demonstrated that the overexpression of CXCL1

led to significant enhancements of the proliferative and migratory

capabilities of both 786-O and CAKI-2 cells (Fig. 5C-H).

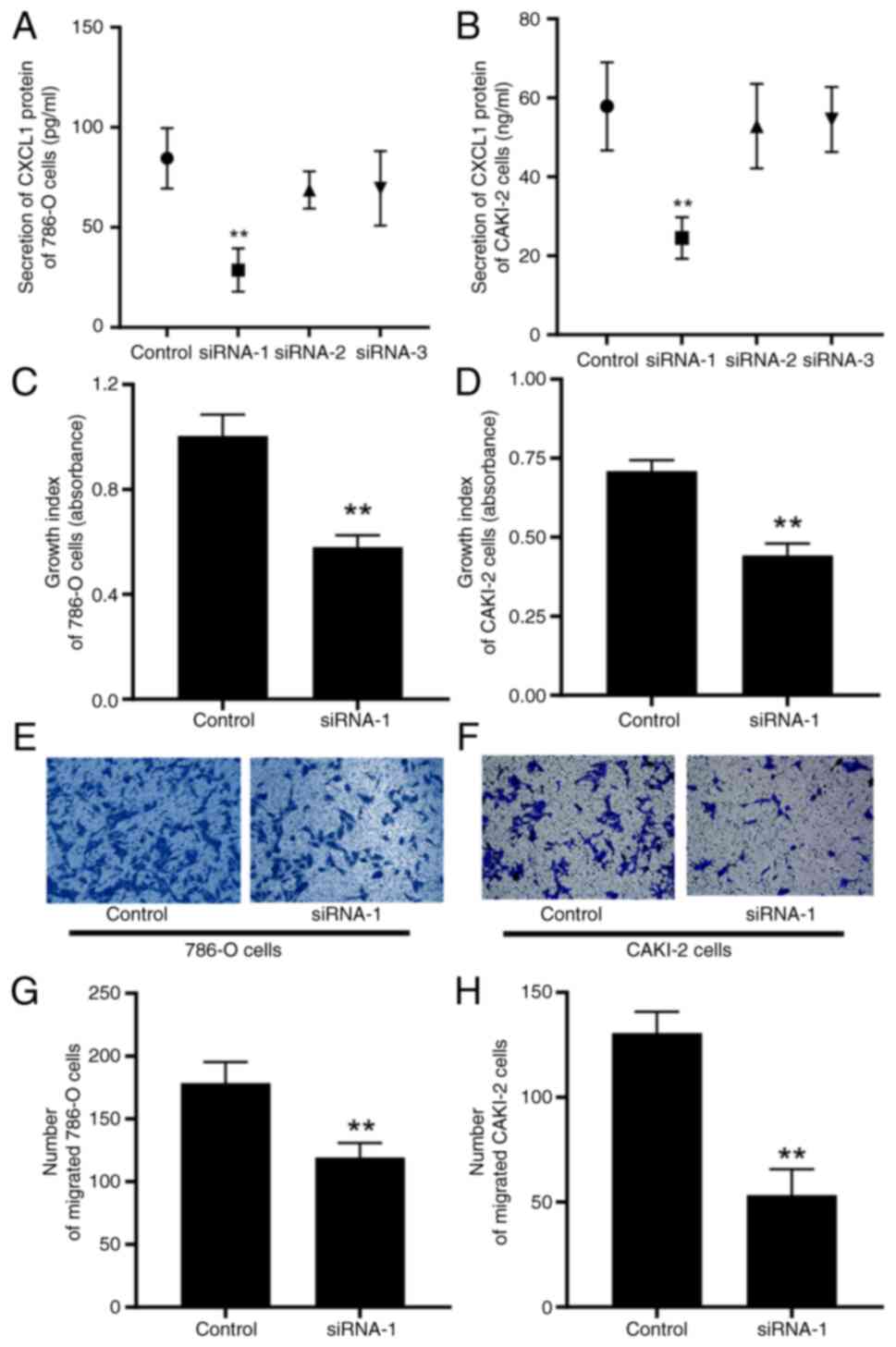

Low expression of CXCL1 impedes the

malignant behaviors of RCC cells

Similarly, in the interference studies, ELISA assay

was used to quantify the secretory protein levels of CXCL1 in the

supernatant, thereby confirming the successful establishment of

786-O and CAKI-2 cells that downregulated CXCL1 at low levels

(Fig. 6A and B). In contrast to the

results observed in the CXCL1 overexpression study, the decreased

expression of CXCL1 led to a marked reduction in both the cell

proliferative and migratory capabilities of the 786-O and CAKI-2

cells (Fig. 6C-H).

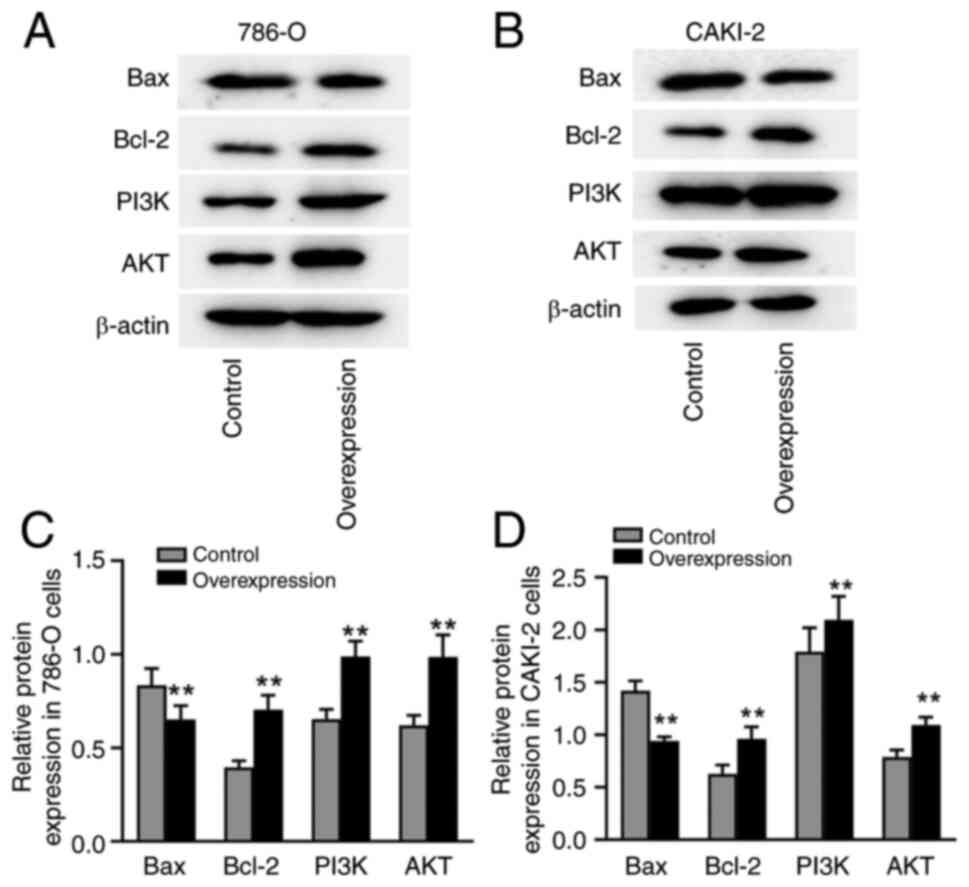

Overexpression of CXCL1 regulates the

expression of PI3K/AKT-associated proteins in RCC cells

Finally, western blotting assays were performed to

investigate the potential underlying mechanisms of CXCL1-mediated

malignant progression in RCC cells with high CXCL1 expression. The

results showed that, in both 786-O and CAKI-2 cells, overexpression

of CXCL1 led to a marked downregulation of the expression Bax, as

well as an upregulation of the expression of PI3K, AKT and Bcl-2

proteins (Fig. 7A-D).

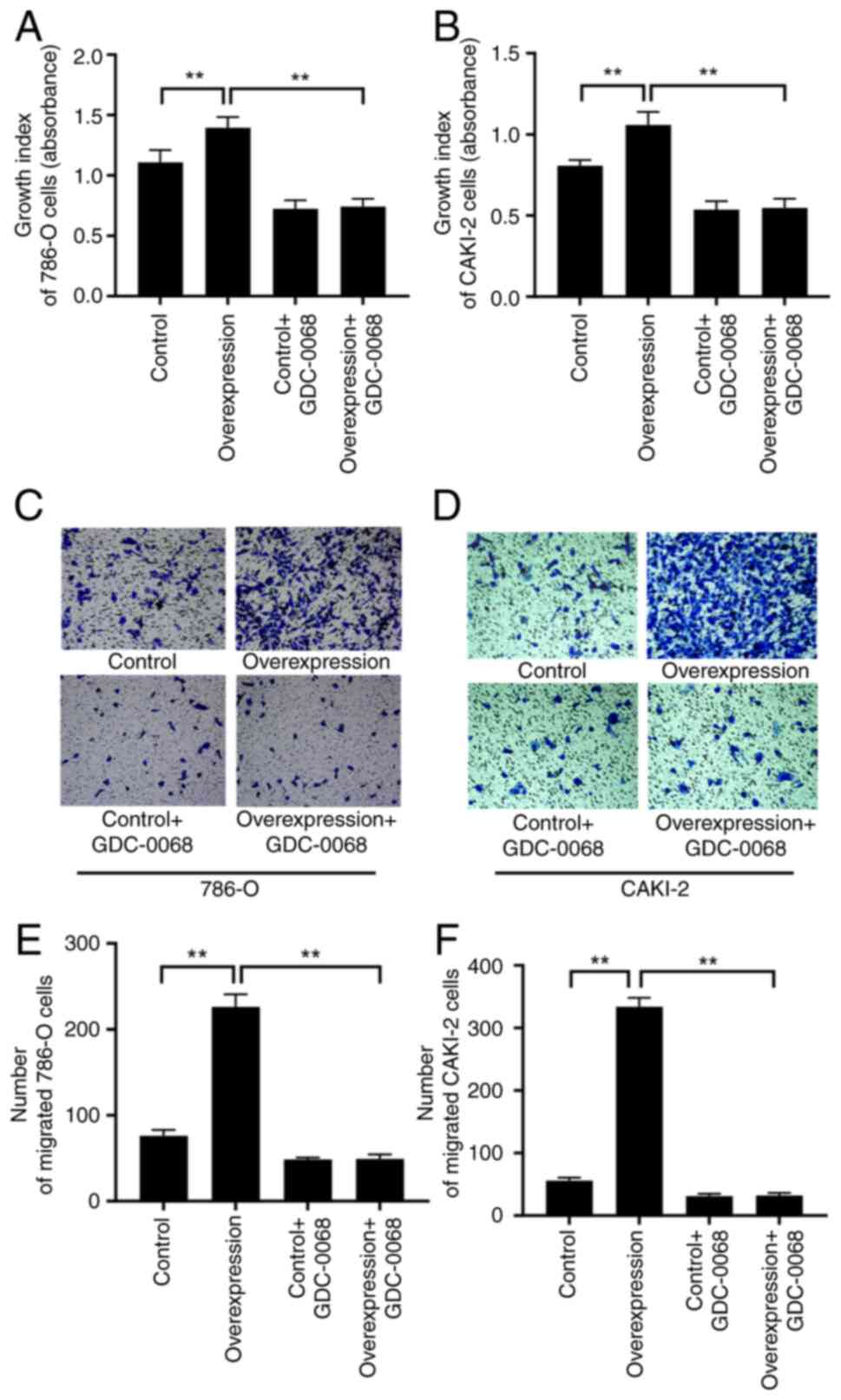

Inhibiting AKT reverses the promoting

effect of a high expression of CXCL1 on the malignant behaviors of

RCC cells

To determine whether the PI3K/AKT pathway regulates

the influence of CXCL1 on the malignant behaviors of RCC cells, a

further experiment was performed, wherein the AKT-specific

inhibitor GDC-0068 was introduced into the cell culture medium to

study 786-O and CAKI-2 cells with CXCL1 overexpression and their

corresponding empty vector-transfected cells. The CCK-8 assay

results revealed that, following GDC-0068 treatment, no significant

differences were observed in the proliferative capability between

the overexpression and control cells (Fig. 8A and B). Similarly, Transwell

(Fig. 8C-F) assays showed that

GDC-0068 could reverse the promoting effects of CXCL1 on migration

in both cell lines.

Discussion

CXCL1, also known as melanoma growth-stimulatory

activity/growth-regulated oncogene a, is a polypeptide that was

originally isolated from human melanoma cells exhibiting

chemotactic properties (16). It

has been proposed that CXCL1 has the capability to induce migration

of immune cells, notably neutrophils, towards sites of inflammation

or infection, thereby participating in immune responses and

inflammatory reactions (17). To

date, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that CXCL1 exhibits

upregulated expression in numerous types of human tumor, and its

upregulation has been shown to be notably associated with advanced

clinical stages, higher grades, distant metastasis and poor

prognosis (13,18). For example, evidence has been

presented to suggest that the expression level of CXCL1 is markedly

upregulated in uterine cervical cancer tissues, and elevated levels

of CXCL1 were found to be notably associated with advanced clinical

stage and decreased survival probabilities (19). Furthermore, previous studies have

revealed a notable association between the expression of CXCL1 and

the histological types of tumors. For example, in the case of

breast cancer, the expression levels of CXCL1 were found to be

markedly increased in tissues of basal-like breast cancer,

mesenchymal-like triple-negative breast cancer and basal-like

triple-negative breast cancer compared with normal tissues

(13). Additionally, a high

expression of CXCL1 was observed in inflammatory breast cancer as

compared with other subtypes of breast cancer (13).

Consistent with the aforementioned findings, the

present study demonstrated a notable upregulation of CXCL1 mRNA and

protein expression in RCC tissues compared with normal and

paracancerous tissues. Notably, high expression of CXCL1 was

strongly associated with advanced stage, higher grade, unfavorable

TNM status and a worse clinical outcome for patients. Moreover, the

findings presented in the current study demonstrated markedly

increased expression of CXCL1 in the ccB subtype of ccRCC compared

with both normal tissues and the ccA subtype. ccRCC comprises two

subtypes defined by distinct gene expression profiles: The ccA

subtype is characterized by the overexpression of genes associated

with hypoxia, angiogenesis, as well as fatty acid and organic acid

metabolism, whereas the unfavorable-outcome ccB subtype features

the overexpression of genes that regulate epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition, cell cycle progression and wound healing (20). Consequently, the results from the

tissue subtype analysis in the present study also suggest an

association between elevated CXCL1 expression and the malignancy of

ccRCC.

The TME consists not only of tumor cells, but also

stromal cells, immune cells, vasculature, extracellular matrix and

soluble factors, in which the chemokines form a dynamic system that

fulfills a pivotal role in tumor progression (10). It is now widely accepted that the

chemokine system is involved in tumor development via multiple

direct and indirect mechanisms that modulate immune cell

infiltration, angiogenesis, as well as tumor cell proliferation,

invasion, metastasis and stem-like properties (21). The present study on co-expression

hub gene and protein-interaction network analysis revealed that

numerous chemokines and their receptors, including CXCL3, CXCL5,

CXCL8, CXCR1 and CXCR2, exhibit co-expression and interactive

associations with CXCL1 in RCC. Similarly, CXCL3, CXCL5 and CXCL8

(along with CXCL1) belong to the ELR + CXC chemokine subfamily, and

their functions are all mediated by the same CXC receptor, CXCR2. A

number of studies have demonstrated that CXCL3, CXCL5 and CXCL8

serve crucial roles in the oncogenic potential of various types of

tumor (22–25). For example, the investigation of

CXCL3 in prostate cancer in the present study demonstrated that

CXCL3 is highly expressed in tumor tissues, and both the exogenous

administration and overexpression of CXCL3 have been shown to

promote tumor proliferation and migratory capabilities through the

ERK/AKT signaling pathway (26,27).

Within the TME, both tumor cells and

tumor-associated cells are able to release a series of chemokines

that regulate the infiltration and activation of diverse immune

cell types, ultimately influencing the balance between

tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing activities (8). Among the recruited immune cell

population, several exhibit antitumor activities, including

CD8+ T cells, type 1 T helper (TH1) cells,

multifunctional TH17 cells and natural killer cells. Additionally,

the recruited antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including

macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), contribute to tumor

regression through activating and amplifying local immune effector

cells (8). On the other hand, other

recruited immune cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells,

regulatory T cells, IL-22+ CD4+ TH22 cells,

IL-22+ innate lymphoid cells and plasmacytoid DCs, have

been demonstrated to accelerate tumor progression through fostering

angiogenesis, suppressing antitumor immune responses and

maintaining tumor stemness (8). In

the present study, a negative correlation between CXCL1 expression

and B cell infiltration was demonstrated in RCC, whereas a positive

correlation was observed with the attraction of CD4+ T

cells and neutrophils. It is considered that B cells, possessing

the capacity to generate antibodies, serve an important role as

crucial mediators in humoral immunity (28). Multiple chemokine/receptor systems,

including CCL21/CCR7, CXCL12/CXCR4 and CXCL13/CXCR5, are implicated

in the recruitment of B cells to the TME (29). A previous study has shown that B

cells exhibit antitumor activity through a multitude of mechanisms,

including the direct killing of tumor cells, the production of

specific antibodies against tumor antigens, acting as APCs to

induce T-cell activation and memory T-cell development, and

facilitating the immune responses of CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells (21).

Similarly, although previous studies have established that

neutrophils display antitumor properties through direct cell

toxicity, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and the

presentation of specific antigens (30), tumor-associated neutrophils notably

present tumor-promoting activities (31).

Subsequently, the functional experiments performed

in the present study showed that both the exogenous administration

and overexpression of CXCL1 led to a marked augmentation of the

proliferative and migratory abilities of RCC cells, whereas

decreased expression of CXCL1 had an inhibitory effect on these

tumorigenic behaviors. CXCL1 has been recognized as an important

autocrine/paracrine molecule in the TME for supporting tumor

progression. For example, silencing CXCL1 has been shown to

markedly reduce tumor proliferation through effectively inducing

apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, suggesting that

autocrine signaling networks may serve a role in CXCL1-associated

tumor biology (32). Tumor cells

with higher CXCL1 levels have also been shown to trigger the

infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) into the TME. CXCL1 derived

from TAMs and CAFs serves a crucial role in regulating

intercellular adhesion and crosstalk between tumor cells and these

stromal cells, further enhancing tumor proliferation in a paracrine

manner (33). Ultimately, the

findings of the present study have revealed that the high

expression of CXCL1 in RCC cells exerts a strong modulatory role on

the expression patterns of proteins associated with the PI3K

signaling pathway, including Bax, Bcl-2, PI3K and AKT. The PI3K

pathway is a crucial signaling cascade within the body, and an

abundance of evidence has shown that the activation of the PI3K

signaling pathway is one of the most prevalent events in human

cancers, being heavily implicated in the development and

progression of tumors through its role in regulating cell growth,

survival, proliferation and migration (34).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

CXCL1 is upregulated in RCC, and this upregulation is positively

associated with various clinicopathological factors, as well as

tumor-associated chemokine expression and immune cell recruitment.

Furthermore, functional studies indicated that overexpression of

CXCL1 contributes to the malignant behaviors of RCC cells, which

are partly mediated via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. However,

although the present study has preliminarily elucidated the role of

CXCL1 in RCC, the authors acknowledge that these findings require

validation through performing in vivo experiments in the

future, and this represents a key limitation of the current

research. Nevertheless, in spite of this limitation, the present

study has not only deepened the understanding of the mechanisms

underlying RCC, but has also offered crucial insights into, and

potential approaches for, the diagnosis and treatment of this

disease, highlighting its notable clinical and translational

implications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by Grants from Joint Cultivation Project

of the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang, China (grant no.

PL2024H003).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HQ carried out the experimental design and edited

the manuscript. SG and CL performed the cellular and molecular

biology experiments. HX performed the bioinformatic analysis. SG

drafted the initial manuscript. CL carried out immunohistochemical

experiments and statistical analyses. HZ and YW performed cellular

experiments. BW carried out molecular biology experiments. SG and

HZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of School of Clinical Medicine, Jiamusi University

(approval no. 202315; ethical approval period from 2023 to 2025),

and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 69:7–34. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Baldewijns MM, van Vlodrop IJ, Schouten

LJ, Soetekouw PM, de Bruïne AP and van Engeland M: Genetics and

epigenetics of renal cell cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1785:133–155. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Linehan WM, Schmidt LS, Crooks DR, Wei D,

Srinivasan R, Lang M and Ricketts CJ: The metabolic basis of kidney

cancer. Cancer Discov. 9:1006–1021. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rijnders M, de Wit R, Boormans JL, Lolkema

MPJ and van der Veldt AAM: Systematic review of immune checkpoint

inhibition in urological cancers. Eur Urol. 72:411–423. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lalani AA, McGregor BA, Albiges L,

Choueiri TK, Motzer R, Powles T, Wood C and Bex A: Systemic

treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma in 2018:

Current paradigms, use of immunotherapy, and future directions. Eur

Urol. 75:100–110. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rot A and von Andrian UH: Chemokines in

innate and adaptive host defense: Basic chemokinese grammar for

immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 22:891–928. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Griffith JW, Sokol CL and Luster AD:

Chemokines and chemokine receptors: Positioning cells for host

defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 32:659–702. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nagarsheth N, Wicha MS and Zou W:

Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in

cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:559–572. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ozga AJ, Chow MT and Luster AD: Chemokines

and the immune response to cancer. Immunity. 54:859–874. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bule P, Aguiar SI and Aires-Da-Silva Fal

Dias JN: Chemokine-directed tumor microenvironment modulation in

cancer immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 22:98042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Märkl F, Huynh D, Endres Sal and Kobold S:

Utilizing chemokines in cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer.

8:670–682. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

O'Hayer KM, Brady DC and Counter CM:

ELR+CXC chemokines and oncogenic Ras-mediated tumorigenesis.

Carcinogenesis. 30:1841–1847. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Korbecki J, Bosiacki M, Barczak K, Łagocka

R, Brodowska A, Chlubek D and Baranowska-Bosiacka I: Involvement in

tumorigenesis and clinical significance of CXCL1 in reproductive

cancers: breast cancer, cervical cancer, endometrial cancer,

ovarian cancer and prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:72622023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yao M, Tabuchi H, Nagashima Y, Baba M,

Nakaigawa N, Ishiguro H, Hamada K, Inayama Y, Kishida T, Hattori K,

et al: Gene expression analysis of renal carcinoma: Adipose

differentiation-related protein as a potential diagnostic and

prognostic biomarker for clear-cell renal carcinoma. J Pathol.

205:377–387. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wozniak MB, Le Calvez-Kelm F,

Abedi-Ardekani B, Byrnes G, Durand G, Carreira C, Michelon J,

Janout V, Holcatova I, Foretova L, et al: Integrative genome-wide

gene expression profiling of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in

Czech Republic and in the United States. PLoS One. 8:e578862013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Richmond A and Thomas HG: Melanoma growth

stimulatory activity: Isolation from human melanoma tumors and

characterization of tissue distribution. J Cell Biochem.

36:185–198. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Schumacher C, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M

and Moser B: High- and low-affinity binding of GRO alpha and

neutrophil-activating peptide 2 to interleukin 8 receptors on human

neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 89:10542–10546. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhuo C, Ruan Q, Zhao X, Shen Y and Lin R:

CXCL1 promotes colon cancer progression through activation of

NF-κB/P300 signaling pathway. Biol Direct. 17:342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Man X, Yang X, Wei Z, Tan Y, Li W, Jin H

and Wang B: High expression level of CXCL1/GROα is linked to

advanced stage and worse survival in uterine cervical cancer and

facilitates tumor cell malignant processes. BMC Cancer. 22:7122022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Purdue MP, Rhee J, Moore L, Gao X, Sun X,

Kirk E, Bencko V, Janout V, Mates D, Zaridze D, et al: Differences

in risk factors for molecular subtypes of clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 149:1448–1454. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Do HTT, Lee CH and Cho J: Chemokines and

their receptors: Multifaceted roles in cancer progression and

potential value as cancer prognostic markers. Cancers (Basel).

12:2872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Qi YL, Li Y, Man XX, Sui HY, Zhao XL,

Zhang PX, Qu XS, Zhang H, Wang BX, Li J, et al: CXCL3

overexpression promotes the tumorigenic potential of uterine

cervical cancer cells via the MAPK/ERK pathway. J Cell Physiol.

235:4756–4765. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chow MT and Luster AD: Chemokines in

cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2:1125–1131. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ha H, Debnath B and Neamati N: Role of the

CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis in cancer and inflammatory diseases.

Theranostics. 7:1543–1588. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang W, Wang H, Sun M, Deng X, Wu X, Ma

Y, Li M, Shuoa SM, You Q and Miao L: CXCL5/CXCR2 axis in tumor

microenvironment as potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic

target. Cancer Commun (Lond). 40:69–80. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gui SL, Teng LC, Wang SQ, Liu S, Lin YL,

Zhao XL, Liu L, Sui HY, Yang Y, Liang L, et al: Overexpression of

CXCL3 can enhance the oncogenic potential of prostate cancer. Int

Urol Nephrol. 48:701–709. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xin H, Cao Y, Shao ML, Zhang W, Zhang CB,

Wang JT, Liang LC, Shao WW, Qi YL, Li Y, et al: Chemokine CXCL3

mediates prostate cancer cells proliferation, migration and gene

expression in an autocrine/paracrine fashion. Int Urol Nephrol.

50:861–868. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Largeot A, Pagano G, Gonder S, Moussay E

and Paggetti J: The B-side of cancer immunity: The underrated tune.

Cells. 8:4492019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Vilgelm AE and Richmond A: Chemokines

modulate immune surveillance in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and

response to immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 10:3332019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sionov RV, Fridlender ZG and Granot Z: The

multifaceted roles neutrophils play in the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Microenviron. 8:125–158. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yuan M, Zhu H, Xu J, Zheng Y, Cao X and

Liu Q: Tumor-Derived CXCL1 promotes lung cancer growth via

recruitment of tumor-associated neutrophils. J Immunol Res.

2016:65304102016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Han KQ, He XQ, Ma MY, Guo XD, Zhang XM,

Chen J, Han H, Zhang WW, Zhu QG and Zhao WZ: Targeted silencing of

CXCL1 by siRNA inhibits tumor growth and apoptosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 47:2131–2140. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Miyake M, Hori S, Morizawa Y, Tatsumi Y,

Nakai Y, Anai S, Torimoto K, Aoki K, Tanaka N, Shimada K, et al:

CXCL1-Mediated interaction of cancer cells with tumor-associated

macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes tumor

progression in human bladder cancer. Neoplasia. 18:636–646. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Noorolyai S, Shajari N, Baghbani E,

Sadreddini S and Baradaran B: The relation between PI3K/AKT

signalling pathway and cancer. Gene. 698:120–128. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|